User login

Preventing RSV in children and adults: A vaccine update

In the past year, there has been significant progress in the availability of interventions to prevent respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and its complications. Four products have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). They include 2 vaccines for adults ages 60 years and older, a monoclonal antibody for infants and high-risk children, and a maternal vaccine to prevent RSV infection in newborns.

RSV in adults

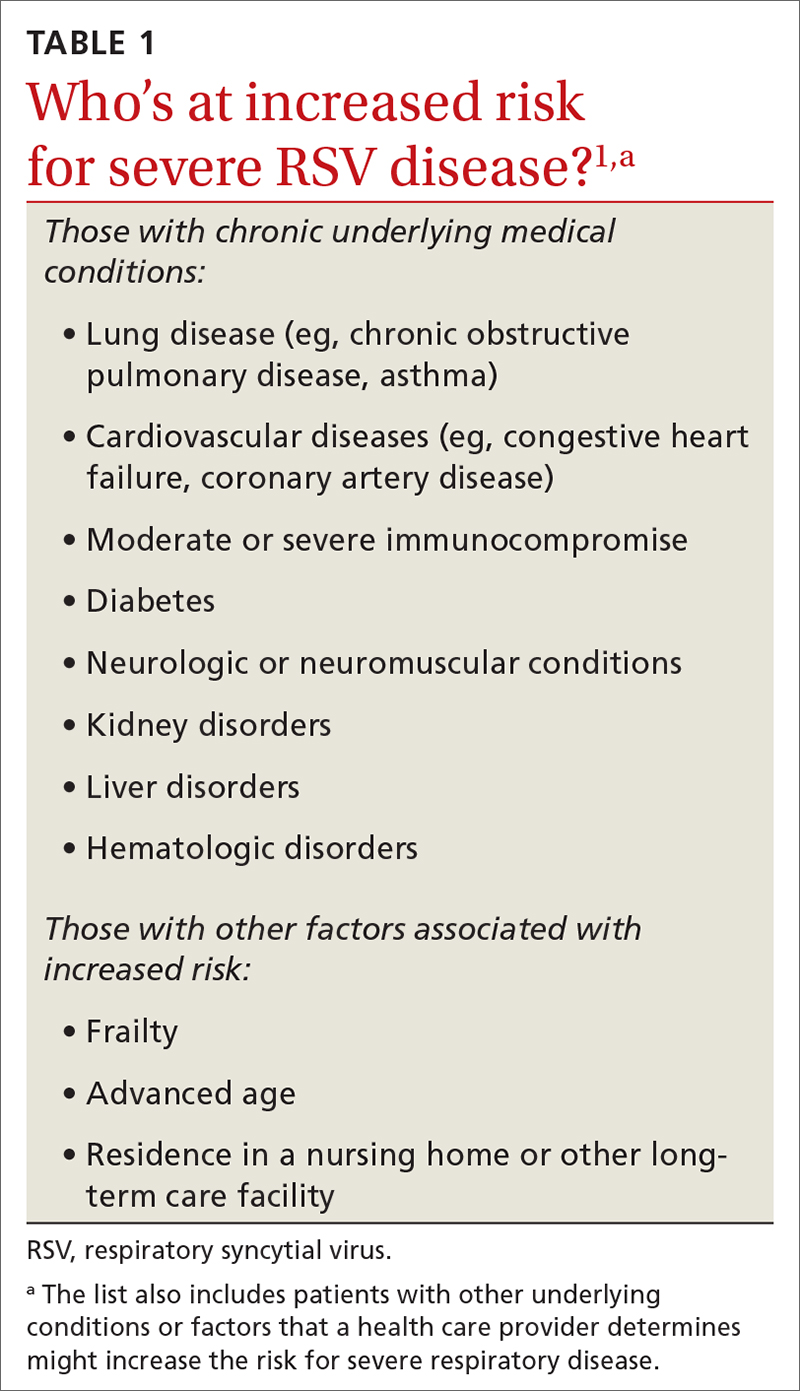

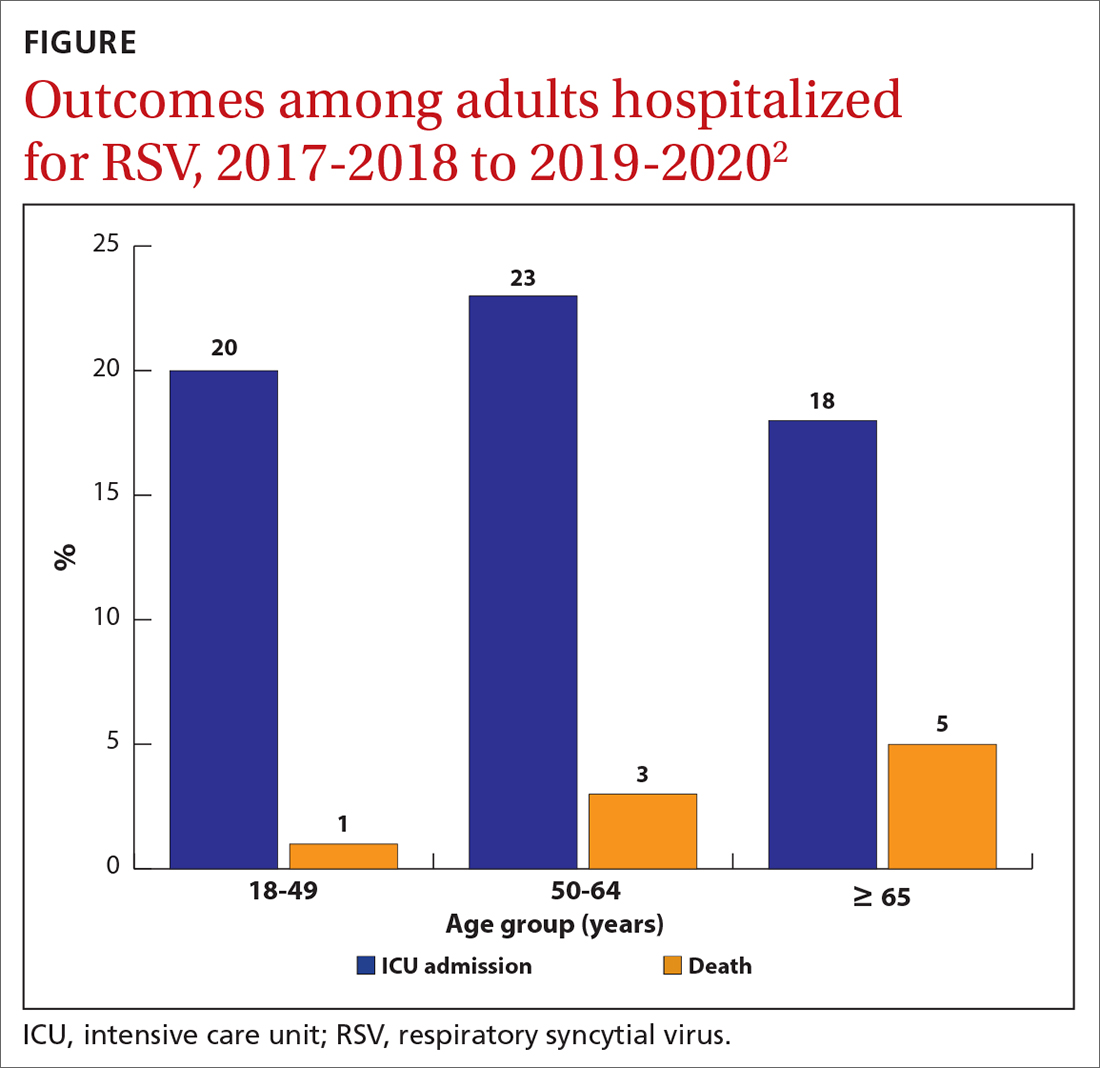

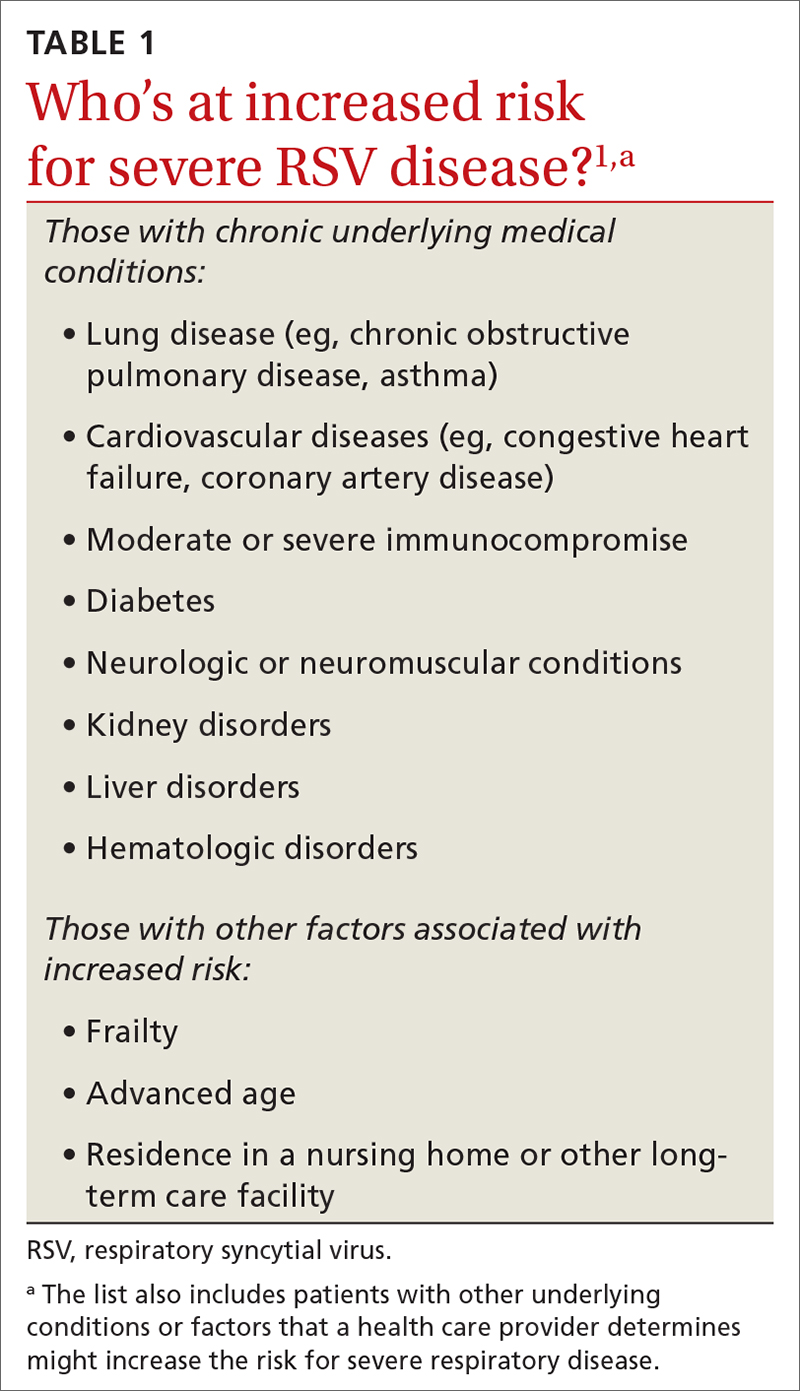

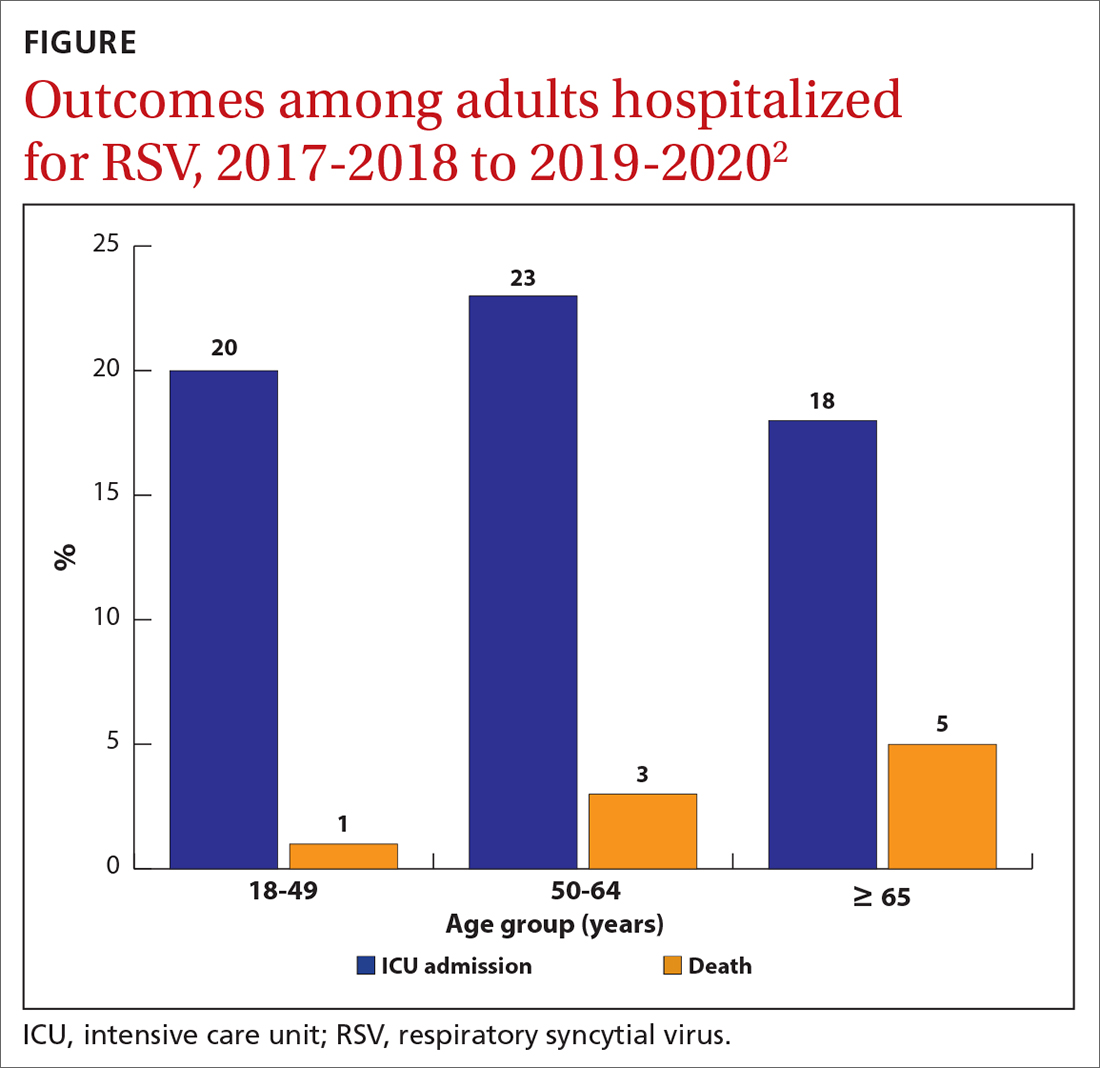

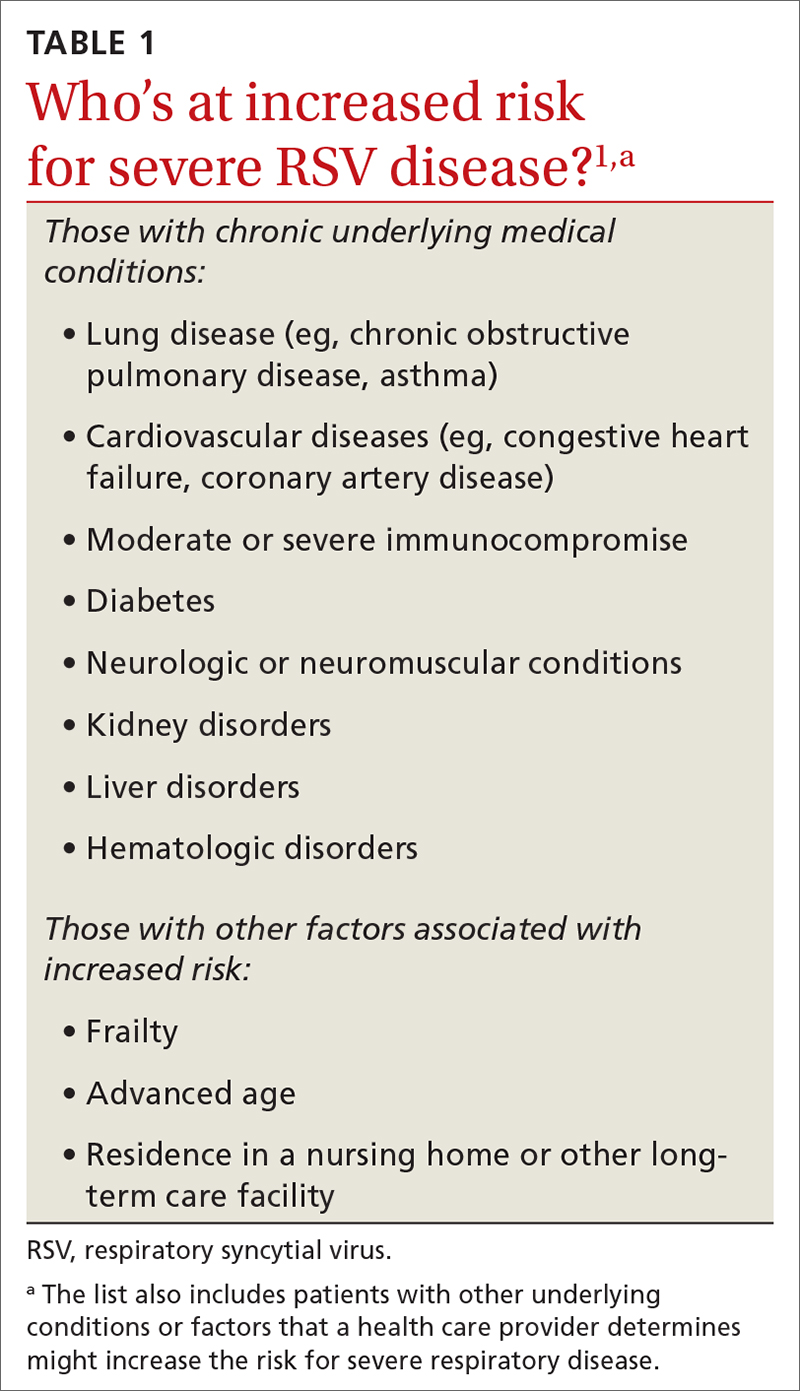

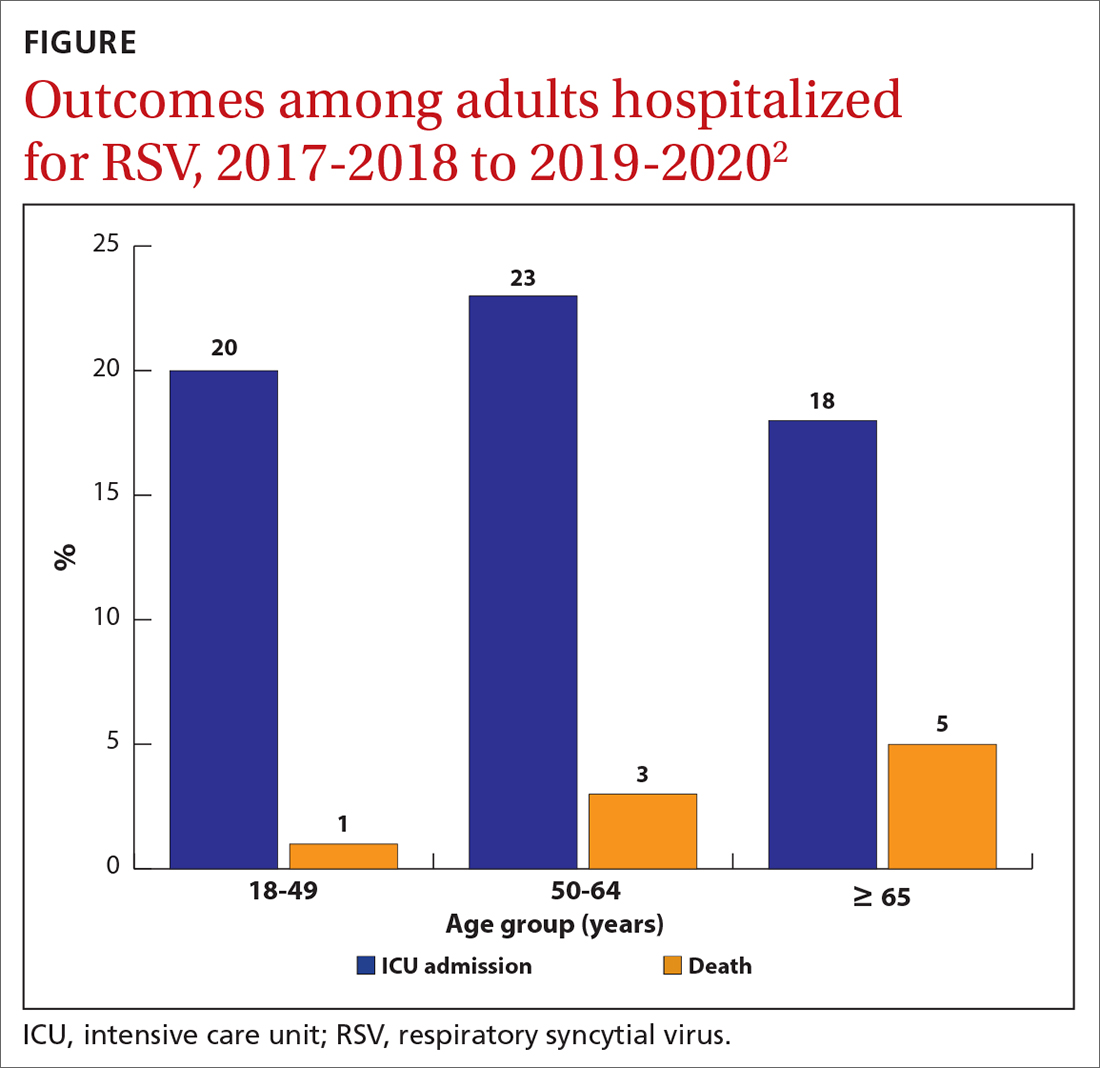

While there is some uncertainty about the total burden of RSV in adults in the United States, the CDC estimates that each year it causes 0.9 to 1.4 million medical encounters, 60,000 to 160,000 hospitalizations, and 6000 to 10,000 deaths.1 The rate of RSV-caused hospitalization increases with age,2 and the infection is more severe in those with certain chronic medical conditions (TABLE 11). The FIGURE2 demonstrates the outcomes of adults who are hospitalized for RSV. Adults older than 65 years have a 5% mortality rate if hospitalized for RSV infection.2

Vaccine options for adults

Two vaccines were recently approved for the prevention of RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease (LRTD) in those ages 60 years and older: RSVPreF3 (Arexvy, GSK), which is an adjuvanted recombinant F protein vaccine, and RSVpreF (Abrysvo, Pfizer), which is a recombinant stabilized vaccine. Both require only a single dose (0.5 mL IM), which provides protection for 2 years.

The efficacy of the GSK vaccine in preventing laboratory-confirmed, RSV-associated LRTD was 82.6% during the first RSV season and 56.1% during the second season. The efficacy of the Pfizer vaccine in preventing symptomatic, laboratory-confirmed LRTD was 88.9% during the first RSV season and 78.6% during the second season.1 However, the trials leading to licensure of both vaccines were underpowered to show efficacy in the oldest adults and those who are frail or to show efficacy against RSV-caused hospitalization.

Safety of the adult RSV vaccines. The safety trials for both vaccines had a total of 38,177 participants. There were a total of 6 neurologic inflammatory conditions that developed within 42 days of vaccination, including 2 cases of suspected Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), 2 cases of possible acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, and 1 case each of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy and undifferentiated motor-sensory axonal polyneuropathy.1 That is a rate of 1 case of a neurologic inflammatory condition for every 6363 people vaccinated. Since the trials were not powered to determine whether the small number of cases were due to chance, postmarketing surveillance will be needed to clarify the true risk for GBS or other neurologic inflammatory events from RSV vaccination.

The lack of efficacy data for the most vulnerable older adults and the lingering questions about safety prompted the ACIP to recommend that adults ages 60 years and older may receive a single dose of RSV vaccine, using shared clinical decision-making—which is different from a routine or risk-based vaccine recommendation. For RSV vaccination, the decision to vaccinate should be based on a risk/benefit discussion between the clinician and the patient. Those most likely to benefit from the vaccine are listed in TABLE 1.1

While data on coadministration of RSV vaccines with other adult vaccines are sparse, the ACIP states that co-administration with other vaccines is acceptable.1 It is not known yet whether boosters will be needed after 2 years.

Continue to: RSV in infants and children

RSV in infants and children

RSV is the most common cause of hospitalization among infants and children in the United States. The CDC estimates that each year in children younger than 5 years, RSV is responsible for 1.5 million outpatient clinic visits, 520,000 emergency department visits, 58,000 to 80,000 hospitalizations, and 100 to 200 deaths.3 The risk for hospitalization from RSV is highest in the second and third months of life and decreases with increasing age.3

There are racial disparities in RSV severity: Intensive care unit admission rates are 1.2 to 1.6 times higher among non-Hispanic Black infants younger than 6 months than among non-Hispanic White infants, and hospitalization rates are up to 5 times higher in American Indian and Alaska Native populations.3

The months of highest RSV transmission in most locations are December through February, but this can vary. For practical purposes, RSV season runs from October through March.

Prevention in infants and children

The monoclonal antibody nirsevimab is now available for use in infants younger than 8 months born during or entering their first RSV season and children ages 8 to 19 months who are at increased risk for severe RSV disease and entering their second RSV season. Details regarding the use of this product were described in a recent Practice Alert Brief.4

Early studies on nirsevimab demonstrated 79% effectiveness in preventing medical-attended LRTD, 80.6% effectiveness in preventing hospitalization, and 90% effectiveness in preventing ICU admission. The number needed to immunize with nirsevimab to prevent an outpatient visit is estimated to be 17; to prevent an ED visit, 48; and to prevent an inpatient admission, 128. Due to the low RSV death rate, the studies were not able to demonstrate reduced mortality.5

Continue to: RSV vaccine in pregnancy

RSV vaccine in pregnancy

In August, the FDA approved Pfizer’s RSVpreF vaccine for use during pregnancy—as a single dose given at 32 to 36 weeks’ gestation—for the prevention of RSV LRTD in infants in the first 6 months of life. In the clinical trials, the vaccine was given at 24 to 36 weeks’ gestation. However, there was a statistically nonsignificant increase in preterm births in the RSVpreF group compared to the placebo group.6 While there were insufficient data to prove or rule out a causal relationship, the FDA advisory committee was more comfortable approving the vaccine for use only later in pregnancy, to avoid the possibility of very early preterm births after vaccination. The ACIP agreed.

From time of maternal vaccination, at least 14 days are needed to develop and transfer maternal antibodies across the placenta to protect the infant. Therefore, infants born less than 14 days after maternal vaccination should be considered unprotected.

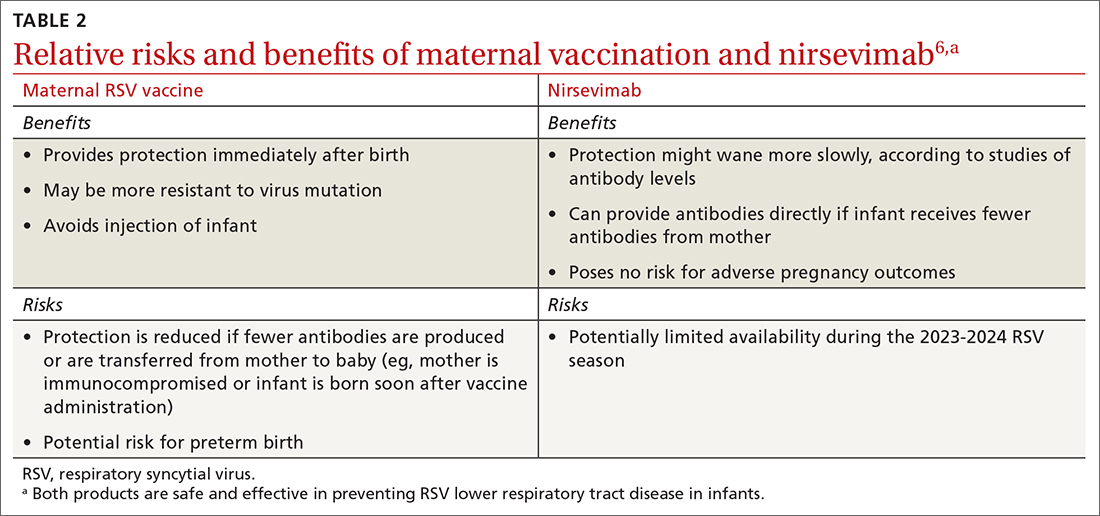

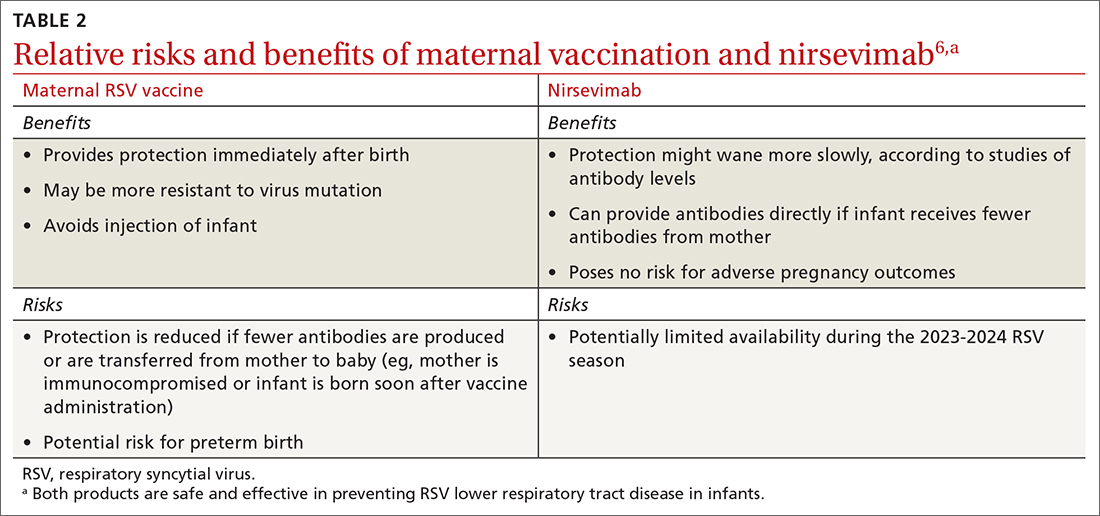

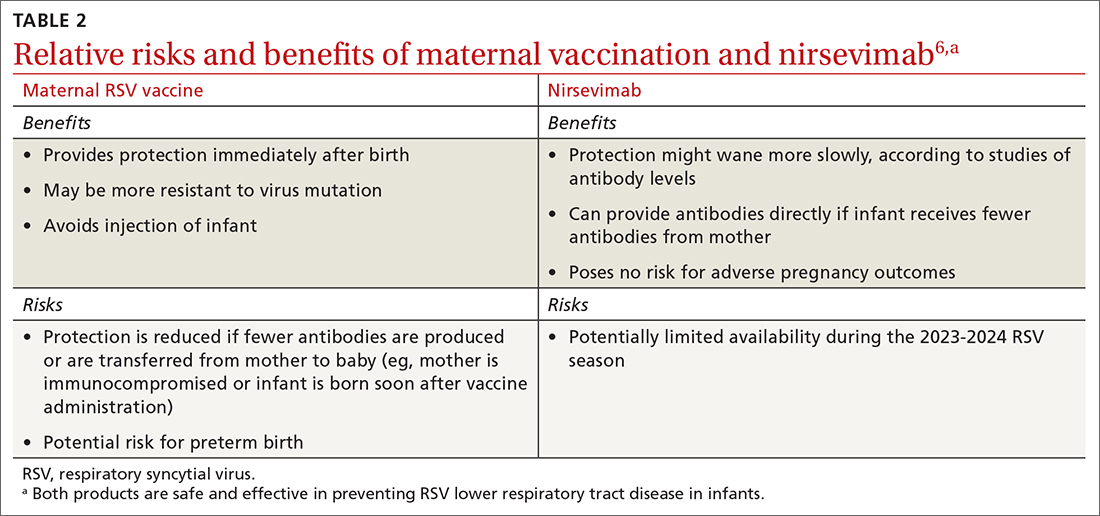

Both maternal vaccination with RSVpreF and infant injection with nirsevimab are now options to protect newborns and infants from RSV. However, use of both products is not needed, since combined they do not offer significant added protection compared to either product alone (exceptions to be discussed shortly).6 When the estimated due date will occur in the RSV season, maternity clinicians should provide information on both products and assist the mother in deciding whether to be vaccinated or rely on administration of nirsevimab to the infant after birth. The benefits and risks of these 2 options are listed in TABLE 2.6

There are some rare situations in which use of both products is recommended, and they include6:

- When the baby is born less than 14 days from the time of maternal vaccination

- When the mother has a condition that could produce an inadequate response to the vaccine

- When the infant has had cardiopulmonary bypass, which would lead to loss of maternal antibodies

- When the infant has severe disease placing them at increased risk for severe RSV.

Conclusion

All of these new RSV preventive products should soon be widely available and covered with no out-of-pocket expense by commercial and government payers. The exception might be nirsevimab—because of the time needed to produce it, it might not be universally available in the 2023-2024 season.

1. Melgar M, Britton A, Roper LE, et al. Use of respiratory syncytial virus vaccine in older adults: recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:793-801.

2. Melgar M. Evidence to recommendation framework. RSV in adults. Presented to the ACIP on February 23, 2023. Accessed November 7, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2023-02/slides-02-23/RSV-Adults-04-Melgar-508.pdf

3. Jones JM, Fleming-Dutra KE, Prill MM, et al. Use of nirsevimab for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus disease among infants and young children: recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:90-925.

4. Campos-Outcalt D. Are you ready for RSV season? There’s a new preventive option. J Fam Pract. 2023;72. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0663

5. Jones J. Evidence to recommendation framework: nirsevimab updates. Presented to the ACIP on August 3, 2023. Accessed August 23, 2023. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/131586

6. Jones J. Clinical considerations for maternal RSVPreF vaccine and nirsevimab. Presented to the ACIP on September 25, 2023. Accessed November 8, 2023. www2.cdc.gov/vaccines/ed/ciinc/archives/23/09/ciiw_RSV2/CIIW%20RSV%20maternal%20vaccine%20mAb%209.27.23.pdf

In the past year, there has been significant progress in the availability of interventions to prevent respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and its complications. Four products have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). They include 2 vaccines for adults ages 60 years and older, a monoclonal antibody for infants and high-risk children, and a maternal vaccine to prevent RSV infection in newborns.

RSV in adults

While there is some uncertainty about the total burden of RSV in adults in the United States, the CDC estimates that each year it causes 0.9 to 1.4 million medical encounters, 60,000 to 160,000 hospitalizations, and 6000 to 10,000 deaths.1 The rate of RSV-caused hospitalization increases with age,2 and the infection is more severe in those with certain chronic medical conditions (TABLE 11). The FIGURE2 demonstrates the outcomes of adults who are hospitalized for RSV. Adults older than 65 years have a 5% mortality rate if hospitalized for RSV infection.2

Vaccine options for adults

Two vaccines were recently approved for the prevention of RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease (LRTD) in those ages 60 years and older: RSVPreF3 (Arexvy, GSK), which is an adjuvanted recombinant F protein vaccine, and RSVpreF (Abrysvo, Pfizer), which is a recombinant stabilized vaccine. Both require only a single dose (0.5 mL IM), which provides protection for 2 years.

The efficacy of the GSK vaccine in preventing laboratory-confirmed, RSV-associated LRTD was 82.6% during the first RSV season and 56.1% during the second season. The efficacy of the Pfizer vaccine in preventing symptomatic, laboratory-confirmed LRTD was 88.9% during the first RSV season and 78.6% during the second season.1 However, the trials leading to licensure of both vaccines were underpowered to show efficacy in the oldest adults and those who are frail or to show efficacy against RSV-caused hospitalization.

Safety of the adult RSV vaccines. The safety trials for both vaccines had a total of 38,177 participants. There were a total of 6 neurologic inflammatory conditions that developed within 42 days of vaccination, including 2 cases of suspected Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), 2 cases of possible acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, and 1 case each of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy and undifferentiated motor-sensory axonal polyneuropathy.1 That is a rate of 1 case of a neurologic inflammatory condition for every 6363 people vaccinated. Since the trials were not powered to determine whether the small number of cases were due to chance, postmarketing surveillance will be needed to clarify the true risk for GBS or other neurologic inflammatory events from RSV vaccination.

The lack of efficacy data for the most vulnerable older adults and the lingering questions about safety prompted the ACIP to recommend that adults ages 60 years and older may receive a single dose of RSV vaccine, using shared clinical decision-making—which is different from a routine or risk-based vaccine recommendation. For RSV vaccination, the decision to vaccinate should be based on a risk/benefit discussion between the clinician and the patient. Those most likely to benefit from the vaccine are listed in TABLE 1.1

While data on coadministration of RSV vaccines with other adult vaccines are sparse, the ACIP states that co-administration with other vaccines is acceptable.1 It is not known yet whether boosters will be needed after 2 years.

Continue to: RSV in infants and children

RSV in infants and children

RSV is the most common cause of hospitalization among infants and children in the United States. The CDC estimates that each year in children younger than 5 years, RSV is responsible for 1.5 million outpatient clinic visits, 520,000 emergency department visits, 58,000 to 80,000 hospitalizations, and 100 to 200 deaths.3 The risk for hospitalization from RSV is highest in the second and third months of life and decreases with increasing age.3

There are racial disparities in RSV severity: Intensive care unit admission rates are 1.2 to 1.6 times higher among non-Hispanic Black infants younger than 6 months than among non-Hispanic White infants, and hospitalization rates are up to 5 times higher in American Indian and Alaska Native populations.3

The months of highest RSV transmission in most locations are December through February, but this can vary. For practical purposes, RSV season runs from October through March.

Prevention in infants and children

The monoclonal antibody nirsevimab is now available for use in infants younger than 8 months born during or entering their first RSV season and children ages 8 to 19 months who are at increased risk for severe RSV disease and entering their second RSV season. Details regarding the use of this product were described in a recent Practice Alert Brief.4

Early studies on nirsevimab demonstrated 79% effectiveness in preventing medical-attended LRTD, 80.6% effectiveness in preventing hospitalization, and 90% effectiveness in preventing ICU admission. The number needed to immunize with nirsevimab to prevent an outpatient visit is estimated to be 17; to prevent an ED visit, 48; and to prevent an inpatient admission, 128. Due to the low RSV death rate, the studies were not able to demonstrate reduced mortality.5

Continue to: RSV vaccine in pregnancy

RSV vaccine in pregnancy

In August, the FDA approved Pfizer’s RSVpreF vaccine for use during pregnancy—as a single dose given at 32 to 36 weeks’ gestation—for the prevention of RSV LRTD in infants in the first 6 months of life. In the clinical trials, the vaccine was given at 24 to 36 weeks’ gestation. However, there was a statistically nonsignificant increase in preterm births in the RSVpreF group compared to the placebo group.6 While there were insufficient data to prove or rule out a causal relationship, the FDA advisory committee was more comfortable approving the vaccine for use only later in pregnancy, to avoid the possibility of very early preterm births after vaccination. The ACIP agreed.

From time of maternal vaccination, at least 14 days are needed to develop and transfer maternal antibodies across the placenta to protect the infant. Therefore, infants born less than 14 days after maternal vaccination should be considered unprotected.

Both maternal vaccination with RSVpreF and infant injection with nirsevimab are now options to protect newborns and infants from RSV. However, use of both products is not needed, since combined they do not offer significant added protection compared to either product alone (exceptions to be discussed shortly).6 When the estimated due date will occur in the RSV season, maternity clinicians should provide information on both products and assist the mother in deciding whether to be vaccinated or rely on administration of nirsevimab to the infant after birth. The benefits and risks of these 2 options are listed in TABLE 2.6

There are some rare situations in which use of both products is recommended, and they include6:

- When the baby is born less than 14 days from the time of maternal vaccination

- When the mother has a condition that could produce an inadequate response to the vaccine

- When the infant has had cardiopulmonary bypass, which would lead to loss of maternal antibodies

- When the infant has severe disease placing them at increased risk for severe RSV.

Conclusion

All of these new RSV preventive products should soon be widely available and covered with no out-of-pocket expense by commercial and government payers. The exception might be nirsevimab—because of the time needed to produce it, it might not be universally available in the 2023-2024 season.

In the past year, there has been significant progress in the availability of interventions to prevent respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and its complications. Four products have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). They include 2 vaccines for adults ages 60 years and older, a monoclonal antibody for infants and high-risk children, and a maternal vaccine to prevent RSV infection in newborns.

RSV in adults

While there is some uncertainty about the total burden of RSV in adults in the United States, the CDC estimates that each year it causes 0.9 to 1.4 million medical encounters, 60,000 to 160,000 hospitalizations, and 6000 to 10,000 deaths.1 The rate of RSV-caused hospitalization increases with age,2 and the infection is more severe in those with certain chronic medical conditions (TABLE 11). The FIGURE2 demonstrates the outcomes of adults who are hospitalized for RSV. Adults older than 65 years have a 5% mortality rate if hospitalized for RSV infection.2

Vaccine options for adults

Two vaccines were recently approved for the prevention of RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease (LRTD) in those ages 60 years and older: RSVPreF3 (Arexvy, GSK), which is an adjuvanted recombinant F protein vaccine, and RSVpreF (Abrysvo, Pfizer), which is a recombinant stabilized vaccine. Both require only a single dose (0.5 mL IM), which provides protection for 2 years.

The efficacy of the GSK vaccine in preventing laboratory-confirmed, RSV-associated LRTD was 82.6% during the first RSV season and 56.1% during the second season. The efficacy of the Pfizer vaccine in preventing symptomatic, laboratory-confirmed LRTD was 88.9% during the first RSV season and 78.6% during the second season.1 However, the trials leading to licensure of both vaccines were underpowered to show efficacy in the oldest adults and those who are frail or to show efficacy against RSV-caused hospitalization.

Safety of the adult RSV vaccines. The safety trials for both vaccines had a total of 38,177 participants. There were a total of 6 neurologic inflammatory conditions that developed within 42 days of vaccination, including 2 cases of suspected Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), 2 cases of possible acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, and 1 case each of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy and undifferentiated motor-sensory axonal polyneuropathy.1 That is a rate of 1 case of a neurologic inflammatory condition for every 6363 people vaccinated. Since the trials were not powered to determine whether the small number of cases were due to chance, postmarketing surveillance will be needed to clarify the true risk for GBS or other neurologic inflammatory events from RSV vaccination.

The lack of efficacy data for the most vulnerable older adults and the lingering questions about safety prompted the ACIP to recommend that adults ages 60 years and older may receive a single dose of RSV vaccine, using shared clinical decision-making—which is different from a routine or risk-based vaccine recommendation. For RSV vaccination, the decision to vaccinate should be based on a risk/benefit discussion between the clinician and the patient. Those most likely to benefit from the vaccine are listed in TABLE 1.1

While data on coadministration of RSV vaccines with other adult vaccines are sparse, the ACIP states that co-administration with other vaccines is acceptable.1 It is not known yet whether boosters will be needed after 2 years.

Continue to: RSV in infants and children

RSV in infants and children

RSV is the most common cause of hospitalization among infants and children in the United States. The CDC estimates that each year in children younger than 5 years, RSV is responsible for 1.5 million outpatient clinic visits, 520,000 emergency department visits, 58,000 to 80,000 hospitalizations, and 100 to 200 deaths.3 The risk for hospitalization from RSV is highest in the second and third months of life and decreases with increasing age.3

There are racial disparities in RSV severity: Intensive care unit admission rates are 1.2 to 1.6 times higher among non-Hispanic Black infants younger than 6 months than among non-Hispanic White infants, and hospitalization rates are up to 5 times higher in American Indian and Alaska Native populations.3

The months of highest RSV transmission in most locations are December through February, but this can vary. For practical purposes, RSV season runs from October through March.

Prevention in infants and children

The monoclonal antibody nirsevimab is now available for use in infants younger than 8 months born during or entering their first RSV season and children ages 8 to 19 months who are at increased risk for severe RSV disease and entering their second RSV season. Details regarding the use of this product were described in a recent Practice Alert Brief.4

Early studies on nirsevimab demonstrated 79% effectiveness in preventing medical-attended LRTD, 80.6% effectiveness in preventing hospitalization, and 90% effectiveness in preventing ICU admission. The number needed to immunize with nirsevimab to prevent an outpatient visit is estimated to be 17; to prevent an ED visit, 48; and to prevent an inpatient admission, 128. Due to the low RSV death rate, the studies were not able to demonstrate reduced mortality.5

Continue to: RSV vaccine in pregnancy

RSV vaccine in pregnancy

In August, the FDA approved Pfizer’s RSVpreF vaccine for use during pregnancy—as a single dose given at 32 to 36 weeks’ gestation—for the prevention of RSV LRTD in infants in the first 6 months of life. In the clinical trials, the vaccine was given at 24 to 36 weeks’ gestation. However, there was a statistically nonsignificant increase in preterm births in the RSVpreF group compared to the placebo group.6 While there were insufficient data to prove or rule out a causal relationship, the FDA advisory committee was more comfortable approving the vaccine for use only later in pregnancy, to avoid the possibility of very early preterm births after vaccination. The ACIP agreed.

From time of maternal vaccination, at least 14 days are needed to develop and transfer maternal antibodies across the placenta to protect the infant. Therefore, infants born less than 14 days after maternal vaccination should be considered unprotected.

Both maternal vaccination with RSVpreF and infant injection with nirsevimab are now options to protect newborns and infants from RSV. However, use of both products is not needed, since combined they do not offer significant added protection compared to either product alone (exceptions to be discussed shortly).6 When the estimated due date will occur in the RSV season, maternity clinicians should provide information on both products and assist the mother in deciding whether to be vaccinated or rely on administration of nirsevimab to the infant after birth. The benefits and risks of these 2 options are listed in TABLE 2.6

There are some rare situations in which use of both products is recommended, and they include6:

- When the baby is born less than 14 days from the time of maternal vaccination

- When the mother has a condition that could produce an inadequate response to the vaccine

- When the infant has had cardiopulmonary bypass, which would lead to loss of maternal antibodies

- When the infant has severe disease placing them at increased risk for severe RSV.

Conclusion

All of these new RSV preventive products should soon be widely available and covered with no out-of-pocket expense by commercial and government payers. The exception might be nirsevimab—because of the time needed to produce it, it might not be universally available in the 2023-2024 season.

1. Melgar M, Britton A, Roper LE, et al. Use of respiratory syncytial virus vaccine in older adults: recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:793-801.

2. Melgar M. Evidence to recommendation framework. RSV in adults. Presented to the ACIP on February 23, 2023. Accessed November 7, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2023-02/slides-02-23/RSV-Adults-04-Melgar-508.pdf

3. Jones JM, Fleming-Dutra KE, Prill MM, et al. Use of nirsevimab for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus disease among infants and young children: recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:90-925.

4. Campos-Outcalt D. Are you ready for RSV season? There’s a new preventive option. J Fam Pract. 2023;72. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0663

5. Jones J. Evidence to recommendation framework: nirsevimab updates. Presented to the ACIP on August 3, 2023. Accessed August 23, 2023. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/131586

6. Jones J. Clinical considerations for maternal RSVPreF vaccine and nirsevimab. Presented to the ACIP on September 25, 2023. Accessed November 8, 2023. www2.cdc.gov/vaccines/ed/ciinc/archives/23/09/ciiw_RSV2/CIIW%20RSV%20maternal%20vaccine%20mAb%209.27.23.pdf

1. Melgar M, Britton A, Roper LE, et al. Use of respiratory syncytial virus vaccine in older adults: recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:793-801.

2. Melgar M. Evidence to recommendation framework. RSV in adults. Presented to the ACIP on February 23, 2023. Accessed November 7, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2023-02/slides-02-23/RSV-Adults-04-Melgar-508.pdf

3. Jones JM, Fleming-Dutra KE, Prill MM, et al. Use of nirsevimab for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus disease among infants and young children: recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:90-925.

4. Campos-Outcalt D. Are you ready for RSV season? There’s a new preventive option. J Fam Pract. 2023;72. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0663

5. Jones J. Evidence to recommendation framework: nirsevimab updates. Presented to the ACIP on August 3, 2023. Accessed August 23, 2023. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/131586

6. Jones J. Clinical considerations for maternal RSVPreF vaccine and nirsevimab. Presented to the ACIP on September 25, 2023. Accessed November 8, 2023. www2.cdc.gov/vaccines/ed/ciinc/archives/23/09/ciiw_RSV2/CIIW%20RSV%20maternal%20vaccine%20mAb%209.27.23.pdf

Keep COVID-19 vaccination on your patients’ radar

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recently issued updated recommendations on the use of vaccines to protect against COVID-19.1 In addition, 3 new COVID-19 vaccine products have been approved for use in the United States since September. Before we discuss both of these items, it’s important to understand why we’re still talking about COVID-19 vaccines.

The impact of vaccination can’t be understated. Vaccines to protect against COVID-19 have been hugely successful in preventing mortality and morbidity from illness caused by SARS-CoV-2. It is estimated that in the first year alone, after vaccines became widely available, they saved more than 14 million lives globally.2 By the end of 2022, they had prevented 18.5 million hospitalizations and 3.2 million deaths in the United States.3 However, waning levels of vaccine-induced immunity and the continuous mutation of the virus have prompted the need for booster doses of vaccine and development of new vaccines.

Enter this year’s vaccines. The new products include updated (2023-2024 formula) COVID-19 mRNA vaccines from Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech, for use in those ages 6 months and older, and Novavax COVID-19 vaccine for use in those ages 12 years and older. All 3 provide protection against the currently circulating XBB variants, which by September 2023 accounted for > 99% of circulating SARS-CoV-2 strains in the United States.1

Novavax is an option for those who are hesitant to use an mRNA-based vaccine, although the exact recommendations for its use are still pending. Of note, the previously approved bivalent vaccines and the previous Novavax monovalent vaccine are no longer approved for use in the United States.

Current recommendations. For those ages 5 years and older, the recommendation is for a single dose of the 2023-2024 COVID-19 vaccine regardless of previous vaccination history—except for those who were previously unvaccinated and choose Novavax. (Those individuals should receive 2 doses, 3 to 8 weeks apart.) For those ages 6 months through 4 years, the recommended number of doses varies by vaccine and previous vaccination history1; a table can be found at www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/wr/mm7242e1.htm.

Those who are moderately to severely immunocompromised should receive a 3-dose series with one of the 2023-2024 COVID-19 vaccines and may receive 1 or more additional updated doses.1 These recommendations are more nuanced, and a full description of them can be found at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/covid-19-vaccines-us.html.

Major changes in this year’s recommendations,4 compared to those previously made on the use of the bivalent vaccines, include:

- Eliminating complex recommendations for 5-year-olds, who are now included in the standard recommendation

- Reducing the number of COVID-19 vaccine products in use by standardizing the dose (25 mcg) for those ages 6 months to 11 years

- Choosing to monitor epidemiology and vaccine effectiveness data to determine whether an additional dose of this year’s vaccine will be needed for those ages 65 years and older, rather than making a recommendation now.

Who’s paying? Another change is how COVID-19 vaccines are paid for. The United States is moving from a system of federal procurement and distribution to the commercial marketplace. This may lead to some disruption and confusion.

All commercial health plans, as well as Medicare and Medicaid, must cover vaccines recommend by the ACIP with no out-of-pocket cost. The Vaccines for Children program provides free vaccine for uninsured and underinsured children up to age 19 years.

However, that leaves no payer for uninsured adults. In response, the CDC has announced the establishment of the Bridge Access Program, which is a private/government partnership to provide the vaccine to this age group. Details about where an adult can obtain a free COVID-19 vaccine through this program can be found by visiting www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/bridge/index.html or by calling 800-CDC-INFO.

A dynamic situation. COVID-19 vaccines and associated recommendations are likely to change with time, as we learn how best to formulate them to adjust to virus mutations and determine the optimal intervals to adjust and administer these vaccines. The result may (or may not) eventually resemble the approach recommended for influenza vaccines, which is annual assessment and adjustment of the targeted antigens, when needed, and annual universal vaccination.

1. Regan JJ, Moulia DL, Link-Guelles R, et al. Use of updated COVID-19 vaccines 2023-2024 formula for persons aged > 6 months: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, September 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:1140-1146. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7242e1

2. Watson OJ, Barnsley G, Toor J, et al. Global impact of the first year of COVID-19 vaccination: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:1293-302. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00320-6

3. Fitzpatrick M, Moghadas S, Pandey A, et al. Two years of US COVID-19 vaccines have prevented millions of hospitalizations and deaths. The Commonwealth Fund; 2022. Published December 13, 2022. Accessed November 2, 2023. www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2022/two-years-covid-vaccines-prevented-millions-deaths-hospitalizations https://doi.org/10.26099/whsf-fp90

4. Wallace M. Evidence to recommendations framework: 2023-2024 (monovalent, XBB containing) COVID-19 vaccine. Presented to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, September 12, 2023. Accessed November 2, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2023-09-12/11-COVID-Wallace-508.pdf

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recently issued updated recommendations on the use of vaccines to protect against COVID-19.1 In addition, 3 new COVID-19 vaccine products have been approved for use in the United States since September. Before we discuss both of these items, it’s important to understand why we’re still talking about COVID-19 vaccines.

The impact of vaccination can’t be understated. Vaccines to protect against COVID-19 have been hugely successful in preventing mortality and morbidity from illness caused by SARS-CoV-2. It is estimated that in the first year alone, after vaccines became widely available, they saved more than 14 million lives globally.2 By the end of 2022, they had prevented 18.5 million hospitalizations and 3.2 million deaths in the United States.3 However, waning levels of vaccine-induced immunity and the continuous mutation of the virus have prompted the need for booster doses of vaccine and development of new vaccines.

Enter this year’s vaccines. The new products include updated (2023-2024 formula) COVID-19 mRNA vaccines from Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech, for use in those ages 6 months and older, and Novavax COVID-19 vaccine for use in those ages 12 years and older. All 3 provide protection against the currently circulating XBB variants, which by September 2023 accounted for > 99% of circulating SARS-CoV-2 strains in the United States.1

Novavax is an option for those who are hesitant to use an mRNA-based vaccine, although the exact recommendations for its use are still pending. Of note, the previously approved bivalent vaccines and the previous Novavax monovalent vaccine are no longer approved for use in the United States.

Current recommendations. For those ages 5 years and older, the recommendation is for a single dose of the 2023-2024 COVID-19 vaccine regardless of previous vaccination history—except for those who were previously unvaccinated and choose Novavax. (Those individuals should receive 2 doses, 3 to 8 weeks apart.) For those ages 6 months through 4 years, the recommended number of doses varies by vaccine and previous vaccination history1; a table can be found at www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/wr/mm7242e1.htm.

Those who are moderately to severely immunocompromised should receive a 3-dose series with one of the 2023-2024 COVID-19 vaccines and may receive 1 or more additional updated doses.1 These recommendations are more nuanced, and a full description of them can be found at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/covid-19-vaccines-us.html.

Major changes in this year’s recommendations,4 compared to those previously made on the use of the bivalent vaccines, include:

- Eliminating complex recommendations for 5-year-olds, who are now included in the standard recommendation

- Reducing the number of COVID-19 vaccine products in use by standardizing the dose (25 mcg) for those ages 6 months to 11 years

- Choosing to monitor epidemiology and vaccine effectiveness data to determine whether an additional dose of this year’s vaccine will be needed for those ages 65 years and older, rather than making a recommendation now.

Who’s paying? Another change is how COVID-19 vaccines are paid for. The United States is moving from a system of federal procurement and distribution to the commercial marketplace. This may lead to some disruption and confusion.

All commercial health plans, as well as Medicare and Medicaid, must cover vaccines recommend by the ACIP with no out-of-pocket cost. The Vaccines for Children program provides free vaccine for uninsured and underinsured children up to age 19 years.

However, that leaves no payer for uninsured adults. In response, the CDC has announced the establishment of the Bridge Access Program, which is a private/government partnership to provide the vaccine to this age group. Details about where an adult can obtain a free COVID-19 vaccine through this program can be found by visiting www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/bridge/index.html or by calling 800-CDC-INFO.

A dynamic situation. COVID-19 vaccines and associated recommendations are likely to change with time, as we learn how best to formulate them to adjust to virus mutations and determine the optimal intervals to adjust and administer these vaccines. The result may (or may not) eventually resemble the approach recommended for influenza vaccines, which is annual assessment and adjustment of the targeted antigens, when needed, and annual universal vaccination.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recently issued updated recommendations on the use of vaccines to protect against COVID-19.1 In addition, 3 new COVID-19 vaccine products have been approved for use in the United States since September. Before we discuss both of these items, it’s important to understand why we’re still talking about COVID-19 vaccines.

The impact of vaccination can’t be understated. Vaccines to protect against COVID-19 have been hugely successful in preventing mortality and morbidity from illness caused by SARS-CoV-2. It is estimated that in the first year alone, after vaccines became widely available, they saved more than 14 million lives globally.2 By the end of 2022, they had prevented 18.5 million hospitalizations and 3.2 million deaths in the United States.3 However, waning levels of vaccine-induced immunity and the continuous mutation of the virus have prompted the need for booster doses of vaccine and development of new vaccines.

Enter this year’s vaccines. The new products include updated (2023-2024 formula) COVID-19 mRNA vaccines from Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech, for use in those ages 6 months and older, and Novavax COVID-19 vaccine for use in those ages 12 years and older. All 3 provide protection against the currently circulating XBB variants, which by September 2023 accounted for > 99% of circulating SARS-CoV-2 strains in the United States.1

Novavax is an option for those who are hesitant to use an mRNA-based vaccine, although the exact recommendations for its use are still pending. Of note, the previously approved bivalent vaccines and the previous Novavax monovalent vaccine are no longer approved for use in the United States.

Current recommendations. For those ages 5 years and older, the recommendation is for a single dose of the 2023-2024 COVID-19 vaccine regardless of previous vaccination history—except for those who were previously unvaccinated and choose Novavax. (Those individuals should receive 2 doses, 3 to 8 weeks apart.) For those ages 6 months through 4 years, the recommended number of doses varies by vaccine and previous vaccination history1; a table can be found at www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/wr/mm7242e1.htm.

Those who are moderately to severely immunocompromised should receive a 3-dose series with one of the 2023-2024 COVID-19 vaccines and may receive 1 or more additional updated doses.1 These recommendations are more nuanced, and a full description of them can be found at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/covid-19-vaccines-us.html.

Major changes in this year’s recommendations,4 compared to those previously made on the use of the bivalent vaccines, include:

- Eliminating complex recommendations for 5-year-olds, who are now included in the standard recommendation

- Reducing the number of COVID-19 vaccine products in use by standardizing the dose (25 mcg) for those ages 6 months to 11 years

- Choosing to monitor epidemiology and vaccine effectiveness data to determine whether an additional dose of this year’s vaccine will be needed for those ages 65 years and older, rather than making a recommendation now.

Who’s paying? Another change is how COVID-19 vaccines are paid for. The United States is moving from a system of federal procurement and distribution to the commercial marketplace. This may lead to some disruption and confusion.

All commercial health plans, as well as Medicare and Medicaid, must cover vaccines recommend by the ACIP with no out-of-pocket cost. The Vaccines for Children program provides free vaccine for uninsured and underinsured children up to age 19 years.

However, that leaves no payer for uninsured adults. In response, the CDC has announced the establishment of the Bridge Access Program, which is a private/government partnership to provide the vaccine to this age group. Details about where an adult can obtain a free COVID-19 vaccine through this program can be found by visiting www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/bridge/index.html or by calling 800-CDC-INFO.

A dynamic situation. COVID-19 vaccines and associated recommendations are likely to change with time, as we learn how best to formulate them to adjust to virus mutations and determine the optimal intervals to adjust and administer these vaccines. The result may (or may not) eventually resemble the approach recommended for influenza vaccines, which is annual assessment and adjustment of the targeted antigens, when needed, and annual universal vaccination.

1. Regan JJ, Moulia DL, Link-Guelles R, et al. Use of updated COVID-19 vaccines 2023-2024 formula for persons aged > 6 months: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, September 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:1140-1146. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7242e1

2. Watson OJ, Barnsley G, Toor J, et al. Global impact of the first year of COVID-19 vaccination: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:1293-302. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00320-6

3. Fitzpatrick M, Moghadas S, Pandey A, et al. Two years of US COVID-19 vaccines have prevented millions of hospitalizations and deaths. The Commonwealth Fund; 2022. Published December 13, 2022. Accessed November 2, 2023. www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2022/two-years-covid-vaccines-prevented-millions-deaths-hospitalizations https://doi.org/10.26099/whsf-fp90

4. Wallace M. Evidence to recommendations framework: 2023-2024 (monovalent, XBB containing) COVID-19 vaccine. Presented to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, September 12, 2023. Accessed November 2, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2023-09-12/11-COVID-Wallace-508.pdf

1. Regan JJ, Moulia DL, Link-Guelles R, et al. Use of updated COVID-19 vaccines 2023-2024 formula for persons aged > 6 months: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, September 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:1140-1146. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7242e1

2. Watson OJ, Barnsley G, Toor J, et al. Global impact of the first year of COVID-19 vaccination: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:1293-302. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00320-6

3. Fitzpatrick M, Moghadas S, Pandey A, et al. Two years of US COVID-19 vaccines have prevented millions of hospitalizations and deaths. The Commonwealth Fund; 2022. Published December 13, 2022. Accessed November 2, 2023. www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2022/two-years-covid-vaccines-prevented-millions-deaths-hospitalizations https://doi.org/10.26099/whsf-fp90

4. Wallace M. Evidence to recommendations framework: 2023-2024 (monovalent, XBB containing) COVID-19 vaccine. Presented to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, September 12, 2023. Accessed November 2, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2023-09-12/11-COVID-Wallace-508.pdf

ACIP updates recommendations for influenza vaccination

When the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) met in June and adopted recommendations for influenza vaccines for the 2023-2024 season, the major discussions focused on the timing of vaccine administration, the composition of the vaccine, and what (if any) special precautions are needed when administering an egg-based vaccine to a person with a history of egg allergy. Here are the takeaways.

When should flu vaccine be administered?

Influenza activity usually peaks between December and the end of March; only twice between 1982 and 2022 did it peak before December. Thus, most people should receive the vaccine in September or October, a recommendation that has not changed from last year. This is early enough to provide adequate protection in most influenza seasons, but late enough to allow protection to persist through the entire season. Vaccination should continue to be offered to those who are unvaccinated throughout the influenza season, as long as influenza viruses are circulating.

Earlier administration is not recommended for most people and is recommended against for those ages 65 years and older (because their immunity from the vaccine may wane faster) and for pregnant people in their first or second trimester (because the vaccine is more effective in preventing influenza in newborns if administered in the third trimester). Evidence regarding waning immunity is inconsistent; however, some studies have shown greater loss of immunity in the elderly compared to younger age groups, as time from vaccination increases.1

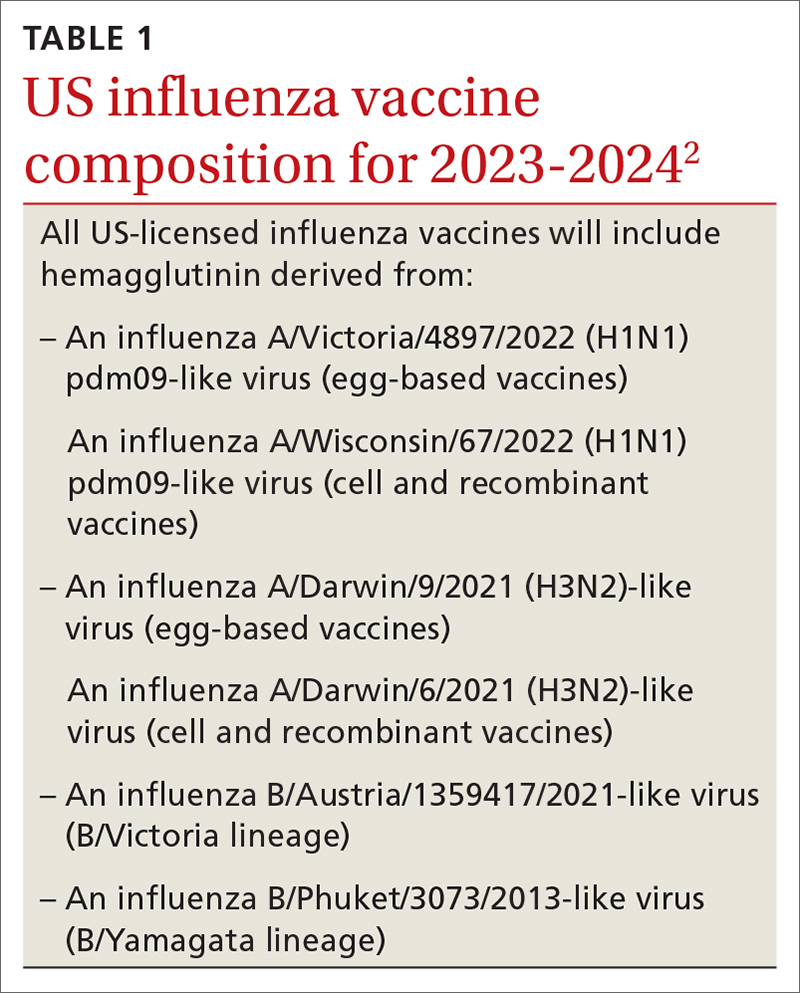

What’s in this year’s vaccines?

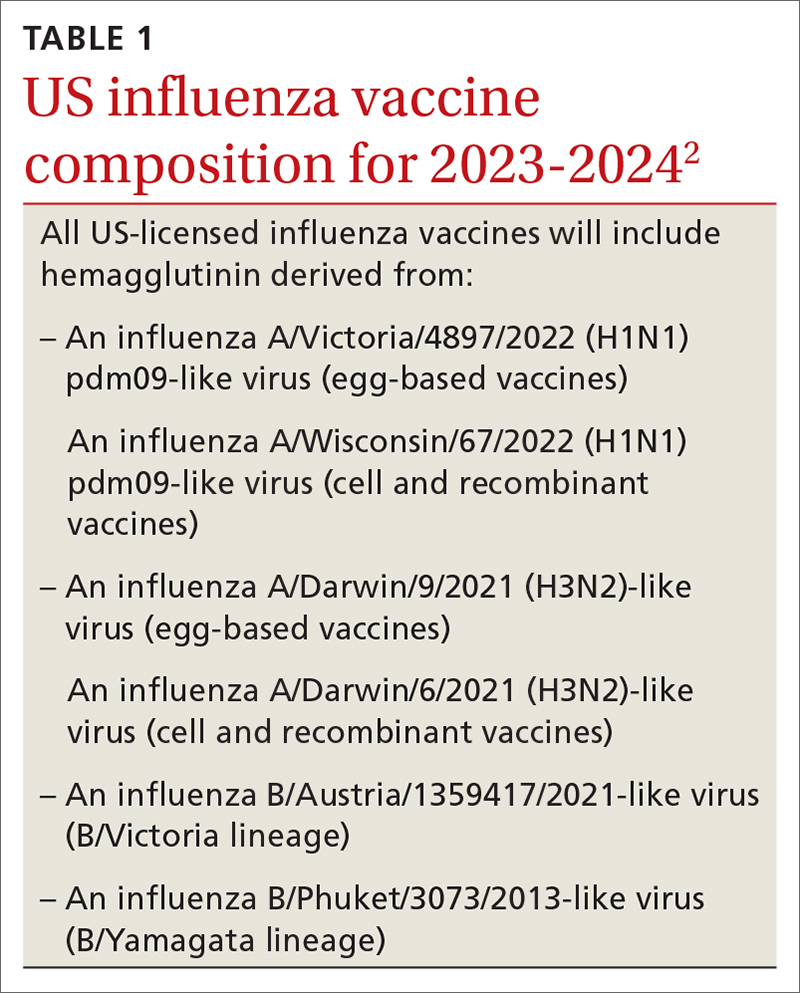

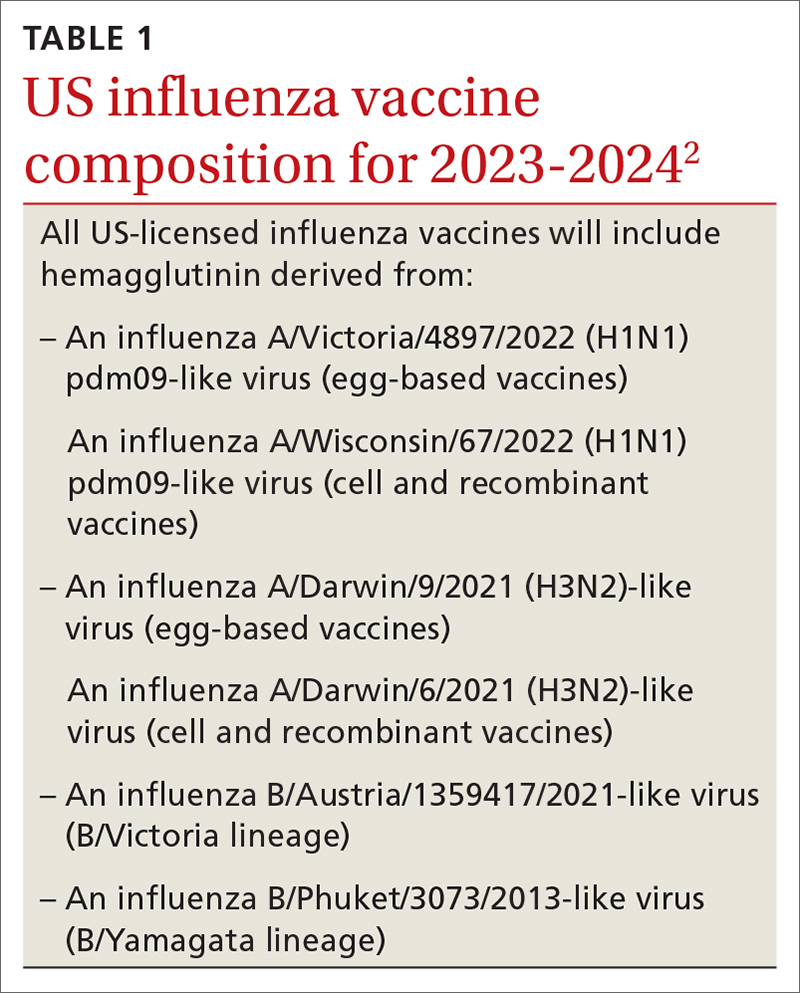

The composition of the vaccines used in North America was determined by the World Health Organization in February, based on the most commonly circulating strains. All vaccines approved for use in the 2023-2024 season are quadrivalent and contain 1 influenza A (H1N1) strain, 1 influenza A (H3N2) strain, and 2 influenza B strains. The specifics of each strain are listed in TABLE 1.2 The 2 influenza A strains are slightly different for the egg-based and non-egg-based vaccines.2 There is no known effectiveness advantage of one antigen strain vs the other.

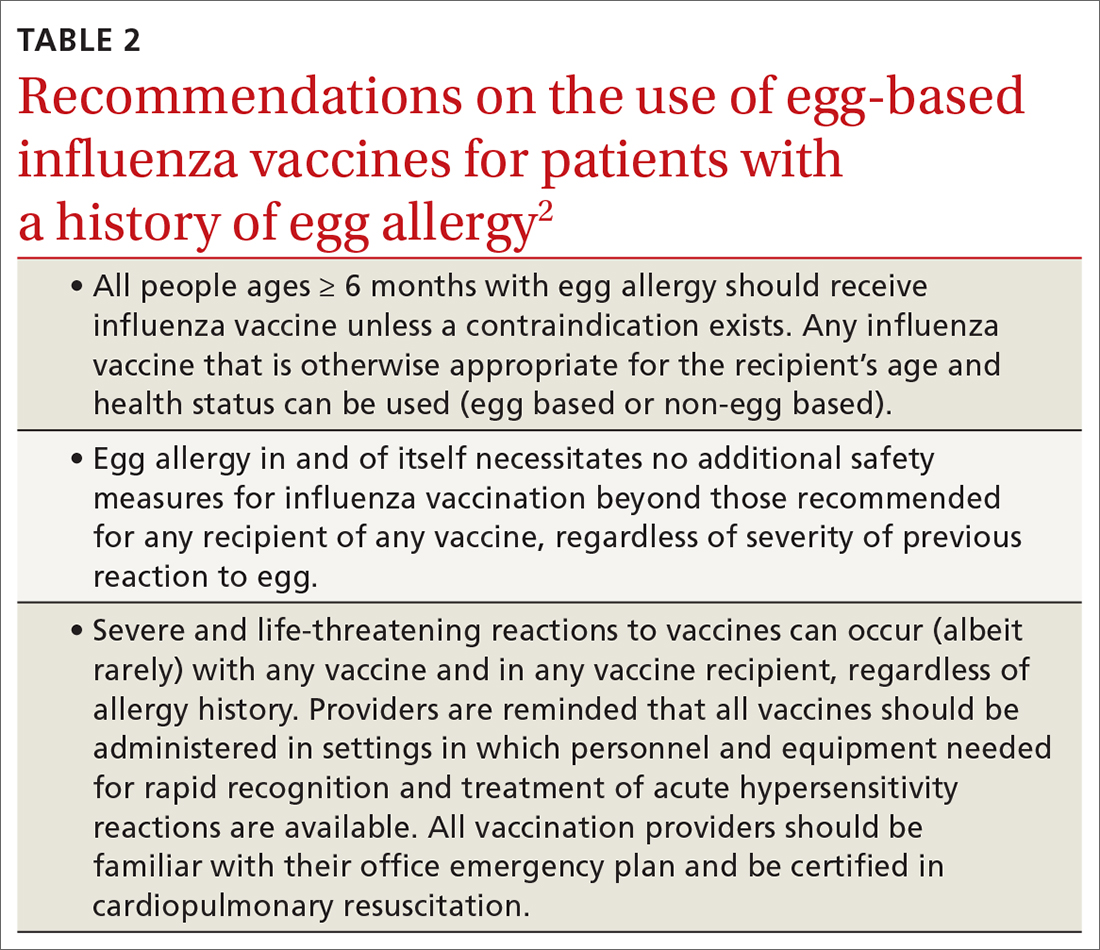

Should you take special precautions with egg allergy?

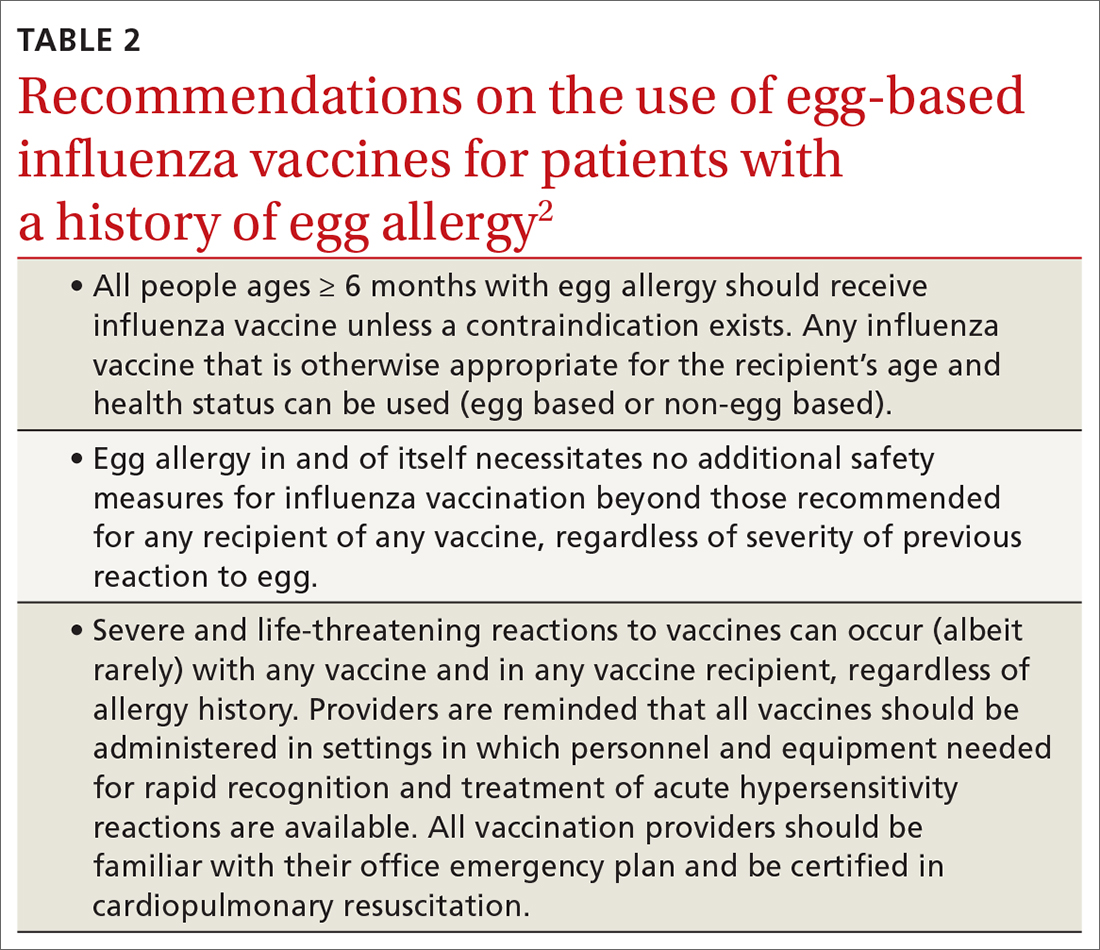

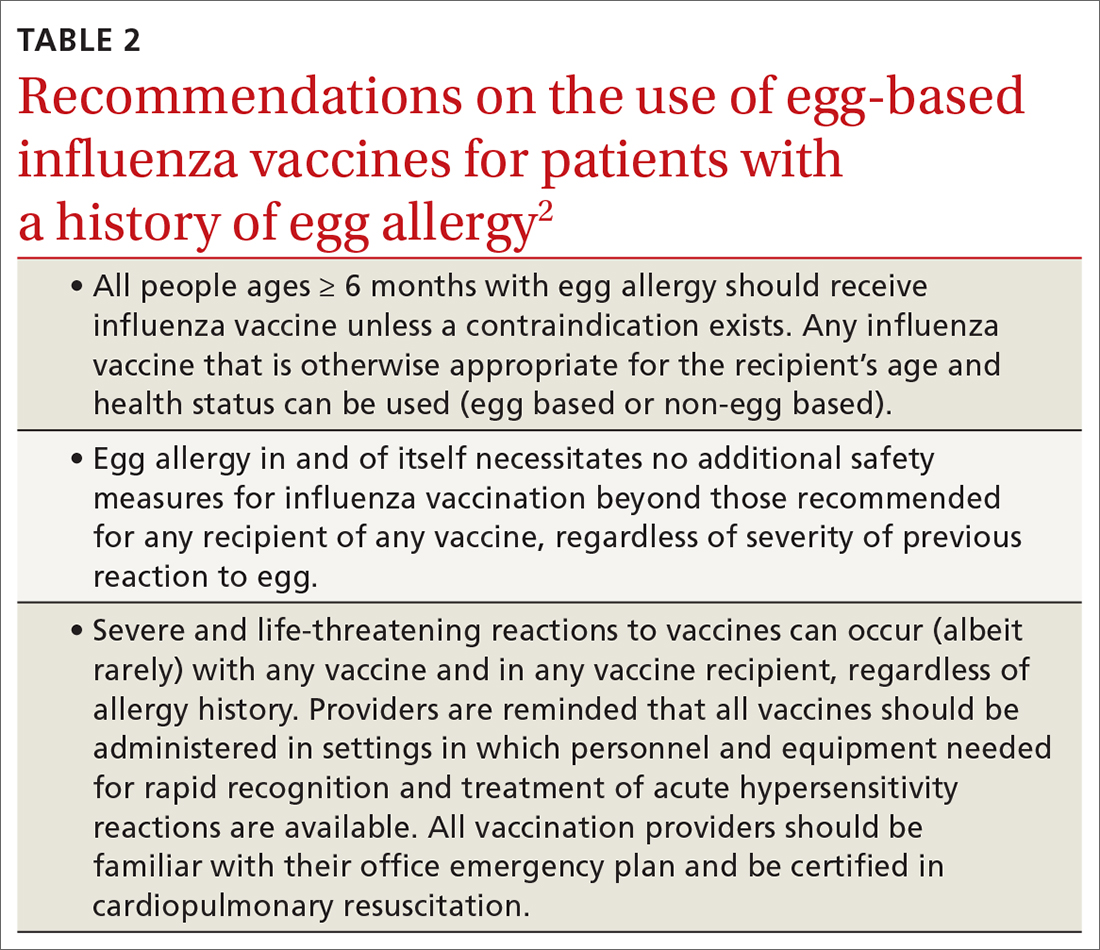

There is new wording to the recommendations on the use of egg-based influenza vaccines for those with a history of egg allergy (TABLE 22). Previously, the ACIP had recommended that if an egg-based vaccine is given to a person with a history of egg allergy, it should be administered in an inpatient or outpatient medical setting (eg, hospital, clinic, health department, physician office) and should be supervised by a health care provider who is able to recognize and manage severe allergic reactions. These added precautions were out of step with other organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics and allergy-related specialty societies, all of whom recommend no special procedures or precautions when administering any influenza vaccine to those with a history of egg allergy.3

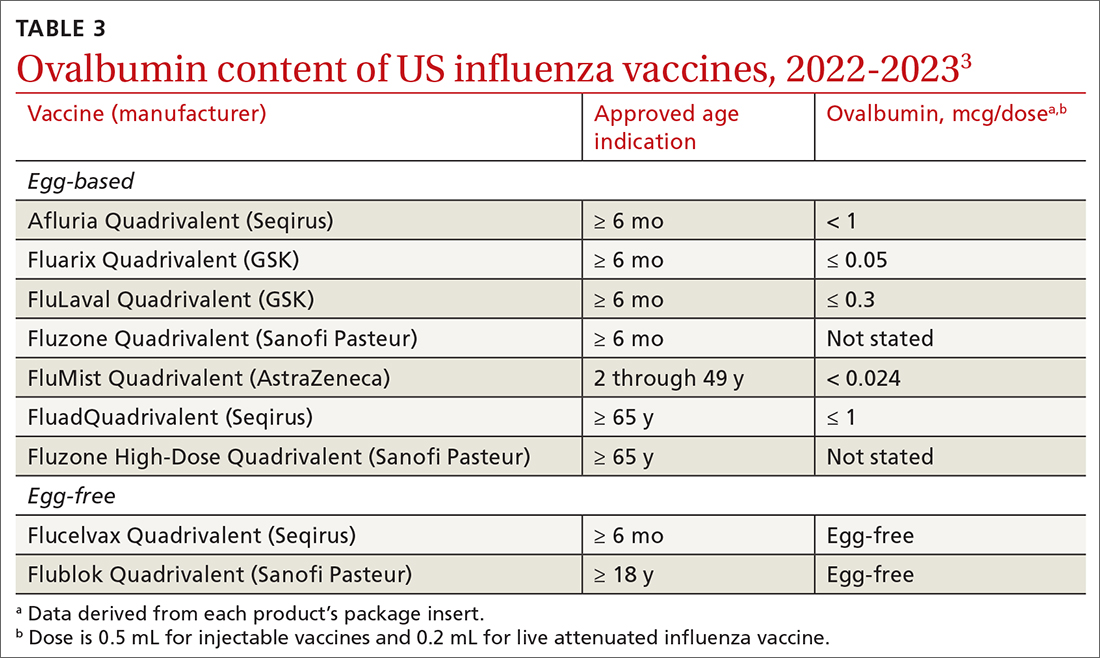

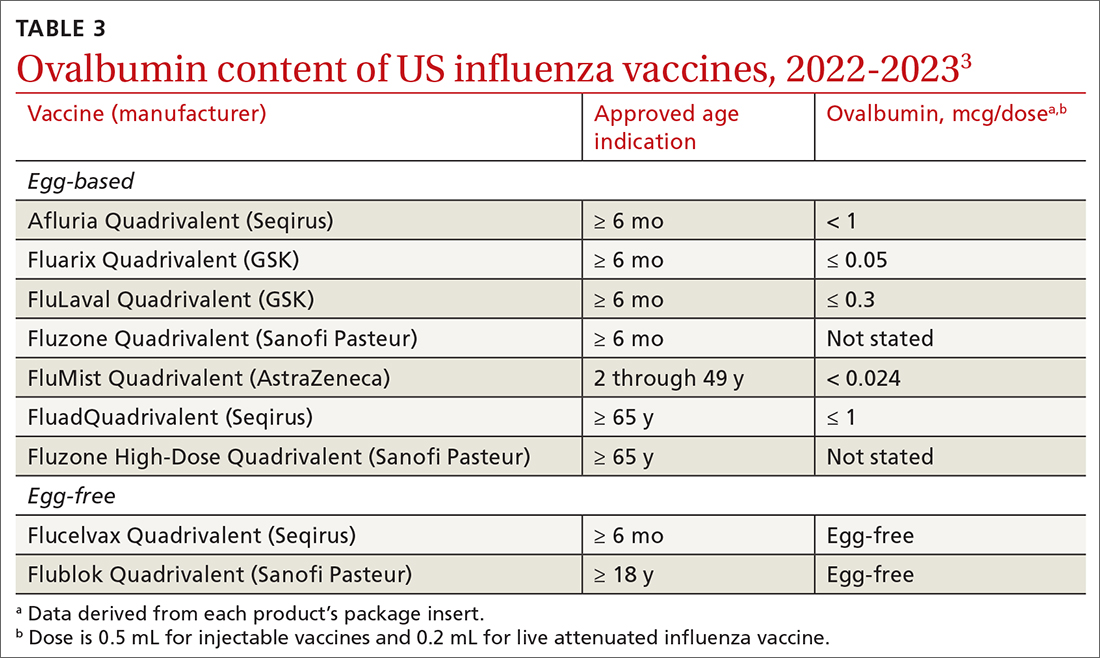

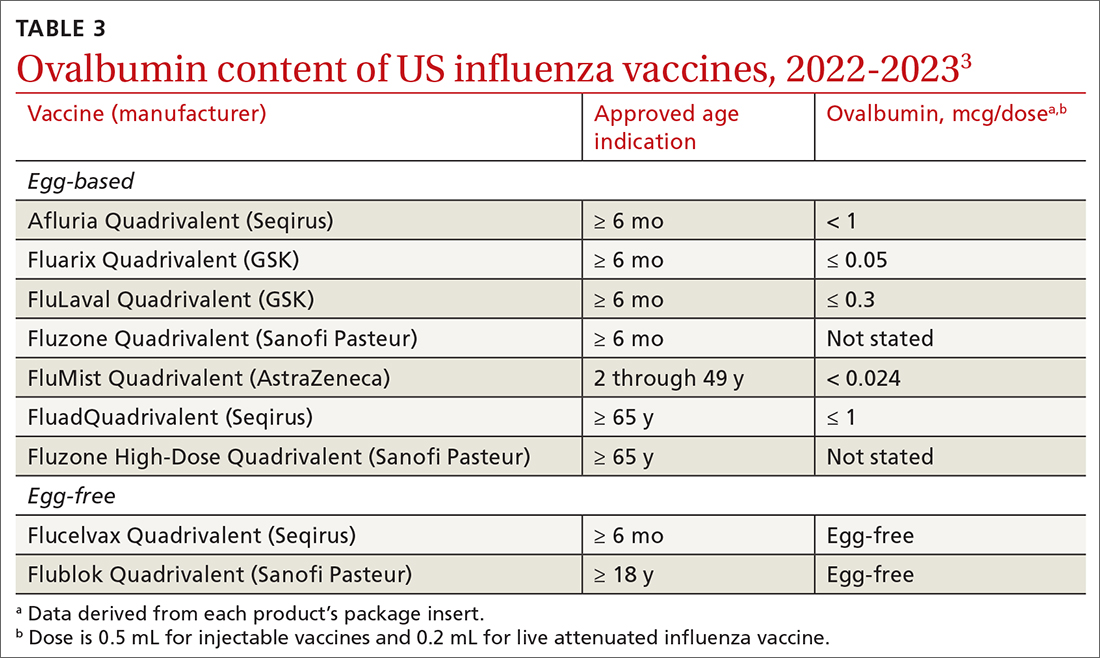

Why the change? Several factors contributed to ACIP’s decision to reword its recommendation. One is that the ovalbumin content of all current influenza vaccines (TABLE 33) is considered too low to trigger an allergic reaction.

Another is the paucity of evidence that egg-based vaccines convey increased risk beyond that for any other vaccine. Although 1% to 3% of children are reported to have an egg allergy, there is no evidence that they are at increased risk for a serious allergic reaction if administered an egg-based vaccine.3 A systematic review of 31 studies (mostly low-quality observational studies and case series) conducted by the ACIP Influenza Work Group found no risk for severe anaphylaxis, hospitalization, or death, even in those with a history of an anaphylactic reaction to eggs.2 A review of Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS) data identified 18 cases of reported anaphylaxis after receipt of an inactivated influenza vaccine over a 5-year period, but clinical review confirmed only 7.2

Continue to: And finally, appropriate precautions already...

And finally, appropriate precautions already are recommended for administration of any vaccine. The CDC guidance for best practices for administering vaccines states: “Although allergic reactions are a common concern for vaccine providers, these reactions are uncommon and anaphylaxis following vaccines is rare, occurring at a rate of approximately one per million doses for many vaccines. Epinephrine and equipment for managing an airway should be available for immediate use.”4

What does this mean in practice? Family physicians who administer influenza vaccines do not need to use special precautions for any influenza vaccine, or use non-egg-based vaccines, for those who have a history of egg allergy. However, they should be prepared to respond to a severe allergic reaction just as they would for any other vaccine. Any vestigial practices pertaining to egg allergy and influenza vaccines—such as vaccine skin testing prior to vaccination (with dilution of vaccine if positive), vaccination deferral or administration via alternative dosing protocols, and split dosing of vaccine—are unnecessary and should be abandoned.

1. Grohskopf LA, Blanton LH, Ferdinands JM, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022–23 Influenza Season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2022;71:1-28. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7101a1

2. Grohskopf LA. Influenza vaccine safety update and proposed recommendations for the 2023-24 influenza season. Presented to the ACIP on June 21, 2023. Accessed September 20, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2023-06-21-23/03-influenza-grohskopf-508.pdf

3. Blanton LH, Grohskopf LA. Influenza vaccination of person with egg allergy: evidence to recommendations discussion and work group considerations. Presented to the ACIP on June 21, 2023. Accessed September 20, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2023-06-21-23/02-influenza-grohskopf-508.pdf

4. Kroger AT, Bahta L, Long S, et al. General best practice guidelines for immunization. Updated August 1, 2023. Accessed September 20, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/general-recs/index.html

When the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) met in June and adopted recommendations for influenza vaccines for the 2023-2024 season, the major discussions focused on the timing of vaccine administration, the composition of the vaccine, and what (if any) special precautions are needed when administering an egg-based vaccine to a person with a history of egg allergy. Here are the takeaways.

When should flu vaccine be administered?

Influenza activity usually peaks between December and the end of March; only twice between 1982 and 2022 did it peak before December. Thus, most people should receive the vaccine in September or October, a recommendation that has not changed from last year. This is early enough to provide adequate protection in most influenza seasons, but late enough to allow protection to persist through the entire season. Vaccination should continue to be offered to those who are unvaccinated throughout the influenza season, as long as influenza viruses are circulating.

Earlier administration is not recommended for most people and is recommended against for those ages 65 years and older (because their immunity from the vaccine may wane faster) and for pregnant people in their first or second trimester (because the vaccine is more effective in preventing influenza in newborns if administered in the third trimester). Evidence regarding waning immunity is inconsistent; however, some studies have shown greater loss of immunity in the elderly compared to younger age groups, as time from vaccination increases.1

What’s in this year’s vaccines?

The composition of the vaccines used in North America was determined by the World Health Organization in February, based on the most commonly circulating strains. All vaccines approved for use in the 2023-2024 season are quadrivalent and contain 1 influenza A (H1N1) strain, 1 influenza A (H3N2) strain, and 2 influenza B strains. The specifics of each strain are listed in TABLE 1.2 The 2 influenza A strains are slightly different for the egg-based and non-egg-based vaccines.2 There is no known effectiveness advantage of one antigen strain vs the other.

Should you take special precautions with egg allergy?

There is new wording to the recommendations on the use of egg-based influenza vaccines for those with a history of egg allergy (TABLE 22). Previously, the ACIP had recommended that if an egg-based vaccine is given to a person with a history of egg allergy, it should be administered in an inpatient or outpatient medical setting (eg, hospital, clinic, health department, physician office) and should be supervised by a health care provider who is able to recognize and manage severe allergic reactions. These added precautions were out of step with other organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics and allergy-related specialty societies, all of whom recommend no special procedures or precautions when administering any influenza vaccine to those with a history of egg allergy.3

Why the change? Several factors contributed to ACIP’s decision to reword its recommendation. One is that the ovalbumin content of all current influenza vaccines (TABLE 33) is considered too low to trigger an allergic reaction.

Another is the paucity of evidence that egg-based vaccines convey increased risk beyond that for any other vaccine. Although 1% to 3% of children are reported to have an egg allergy, there is no evidence that they are at increased risk for a serious allergic reaction if administered an egg-based vaccine.3 A systematic review of 31 studies (mostly low-quality observational studies and case series) conducted by the ACIP Influenza Work Group found no risk for severe anaphylaxis, hospitalization, or death, even in those with a history of an anaphylactic reaction to eggs.2 A review of Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS) data identified 18 cases of reported anaphylaxis after receipt of an inactivated influenza vaccine over a 5-year period, but clinical review confirmed only 7.2

Continue to: And finally, appropriate precautions already...

And finally, appropriate precautions already are recommended for administration of any vaccine. The CDC guidance for best practices for administering vaccines states: “Although allergic reactions are a common concern for vaccine providers, these reactions are uncommon and anaphylaxis following vaccines is rare, occurring at a rate of approximately one per million doses for many vaccines. Epinephrine and equipment for managing an airway should be available for immediate use.”4

What does this mean in practice? Family physicians who administer influenza vaccines do not need to use special precautions for any influenza vaccine, or use non-egg-based vaccines, for those who have a history of egg allergy. However, they should be prepared to respond to a severe allergic reaction just as they would for any other vaccine. Any vestigial practices pertaining to egg allergy and influenza vaccines—such as vaccine skin testing prior to vaccination (with dilution of vaccine if positive), vaccination deferral or administration via alternative dosing protocols, and split dosing of vaccine—are unnecessary and should be abandoned.

When the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) met in June and adopted recommendations for influenza vaccines for the 2023-2024 season, the major discussions focused on the timing of vaccine administration, the composition of the vaccine, and what (if any) special precautions are needed when administering an egg-based vaccine to a person with a history of egg allergy. Here are the takeaways.

When should flu vaccine be administered?

Influenza activity usually peaks between December and the end of March; only twice between 1982 and 2022 did it peak before December. Thus, most people should receive the vaccine in September or October, a recommendation that has not changed from last year. This is early enough to provide adequate protection in most influenza seasons, but late enough to allow protection to persist through the entire season. Vaccination should continue to be offered to those who are unvaccinated throughout the influenza season, as long as influenza viruses are circulating.

Earlier administration is not recommended for most people and is recommended against for those ages 65 years and older (because their immunity from the vaccine may wane faster) and for pregnant people in their first or second trimester (because the vaccine is more effective in preventing influenza in newborns if administered in the third trimester). Evidence regarding waning immunity is inconsistent; however, some studies have shown greater loss of immunity in the elderly compared to younger age groups, as time from vaccination increases.1

What’s in this year’s vaccines?

The composition of the vaccines used in North America was determined by the World Health Organization in February, based on the most commonly circulating strains. All vaccines approved for use in the 2023-2024 season are quadrivalent and contain 1 influenza A (H1N1) strain, 1 influenza A (H3N2) strain, and 2 influenza B strains. The specifics of each strain are listed in TABLE 1.2 The 2 influenza A strains are slightly different for the egg-based and non-egg-based vaccines.2 There is no known effectiveness advantage of one antigen strain vs the other.

Should you take special precautions with egg allergy?

There is new wording to the recommendations on the use of egg-based influenza vaccines for those with a history of egg allergy (TABLE 22). Previously, the ACIP had recommended that if an egg-based vaccine is given to a person with a history of egg allergy, it should be administered in an inpatient or outpatient medical setting (eg, hospital, clinic, health department, physician office) and should be supervised by a health care provider who is able to recognize and manage severe allergic reactions. These added precautions were out of step with other organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics and allergy-related specialty societies, all of whom recommend no special procedures or precautions when administering any influenza vaccine to those with a history of egg allergy.3

Why the change? Several factors contributed to ACIP’s decision to reword its recommendation. One is that the ovalbumin content of all current influenza vaccines (TABLE 33) is considered too low to trigger an allergic reaction.

Another is the paucity of evidence that egg-based vaccines convey increased risk beyond that for any other vaccine. Although 1% to 3% of children are reported to have an egg allergy, there is no evidence that they are at increased risk for a serious allergic reaction if administered an egg-based vaccine.3 A systematic review of 31 studies (mostly low-quality observational studies and case series) conducted by the ACIP Influenza Work Group found no risk for severe anaphylaxis, hospitalization, or death, even in those with a history of an anaphylactic reaction to eggs.2 A review of Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS) data identified 18 cases of reported anaphylaxis after receipt of an inactivated influenza vaccine over a 5-year period, but clinical review confirmed only 7.2

Continue to: And finally, appropriate precautions already...

And finally, appropriate precautions already are recommended for administration of any vaccine. The CDC guidance for best practices for administering vaccines states: “Although allergic reactions are a common concern for vaccine providers, these reactions are uncommon and anaphylaxis following vaccines is rare, occurring at a rate of approximately one per million doses for many vaccines. Epinephrine and equipment for managing an airway should be available for immediate use.”4

What does this mean in practice? Family physicians who administer influenza vaccines do not need to use special precautions for any influenza vaccine, or use non-egg-based vaccines, for those who have a history of egg allergy. However, they should be prepared to respond to a severe allergic reaction just as they would for any other vaccine. Any vestigial practices pertaining to egg allergy and influenza vaccines—such as vaccine skin testing prior to vaccination (with dilution of vaccine if positive), vaccination deferral or administration via alternative dosing protocols, and split dosing of vaccine—are unnecessary and should be abandoned.

1. Grohskopf LA, Blanton LH, Ferdinands JM, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022–23 Influenza Season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2022;71:1-28. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7101a1

2. Grohskopf LA. Influenza vaccine safety update and proposed recommendations for the 2023-24 influenza season. Presented to the ACIP on June 21, 2023. Accessed September 20, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2023-06-21-23/03-influenza-grohskopf-508.pdf

3. Blanton LH, Grohskopf LA. Influenza vaccination of person with egg allergy: evidence to recommendations discussion and work group considerations. Presented to the ACIP on June 21, 2023. Accessed September 20, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2023-06-21-23/02-influenza-grohskopf-508.pdf

4. Kroger AT, Bahta L, Long S, et al. General best practice guidelines for immunization. Updated August 1, 2023. Accessed September 20, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/general-recs/index.html

1. Grohskopf LA, Blanton LH, Ferdinands JM, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022–23 Influenza Season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2022;71:1-28. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7101a1

2. Grohskopf LA. Influenza vaccine safety update and proposed recommendations for the 2023-24 influenza season. Presented to the ACIP on June 21, 2023. Accessed September 20, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2023-06-21-23/03-influenza-grohskopf-508.pdf

3. Blanton LH, Grohskopf LA. Influenza vaccination of person with egg allergy: evidence to recommendations discussion and work group considerations. Presented to the ACIP on June 21, 2023. Accessed September 20, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2023-06-21-23/02-influenza-grohskopf-508.pdf

4. Kroger AT, Bahta L, Long S, et al. General best practice guidelines for immunization. Updated August 1, 2023. Accessed September 20, 2023. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/general-recs/index.html

Updated guidance from USPSTF on PrEP for HIV prevention

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently released their final recommendation update on the use of antiretroviral therapy to prevent HIV infection in adolescents and adults who are at increased risk.1 The Task Force last addressed this topic in 2019; since then, 2 additional antiretroviral regimens have been approved for preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP). The update also includes revised wording on who should consider receiving PrEP.

HIV remains a significant public health problem in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 1.2 million people in the United States are living with HIV, and approximately 30,000 new infections occur each year.2 Men who have sex with men account for 68% of new infections, and there are marked racial disparities in both incidence and prevalence of infection, with Black/African Americans accounting for 42% of new infections.2

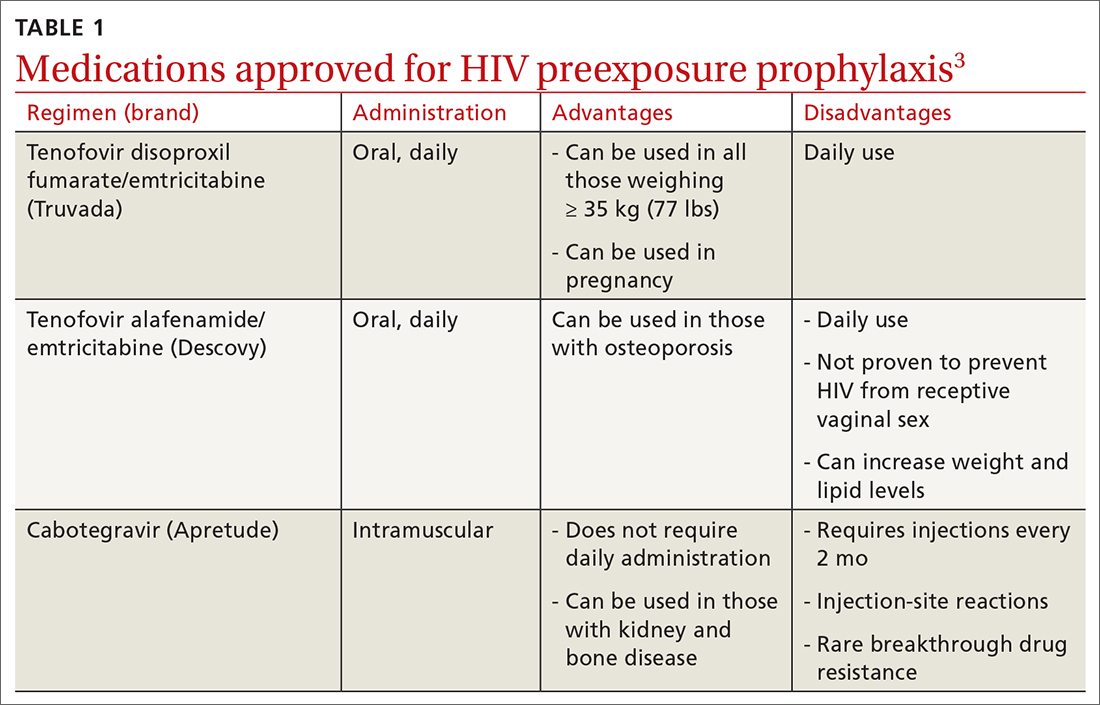

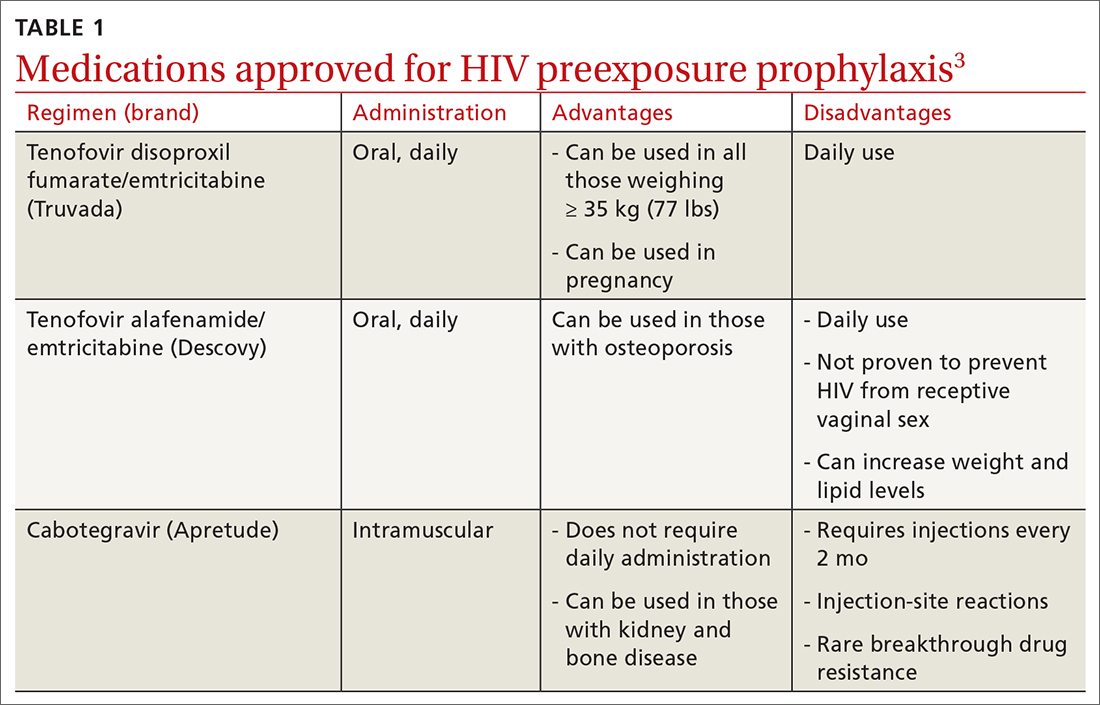

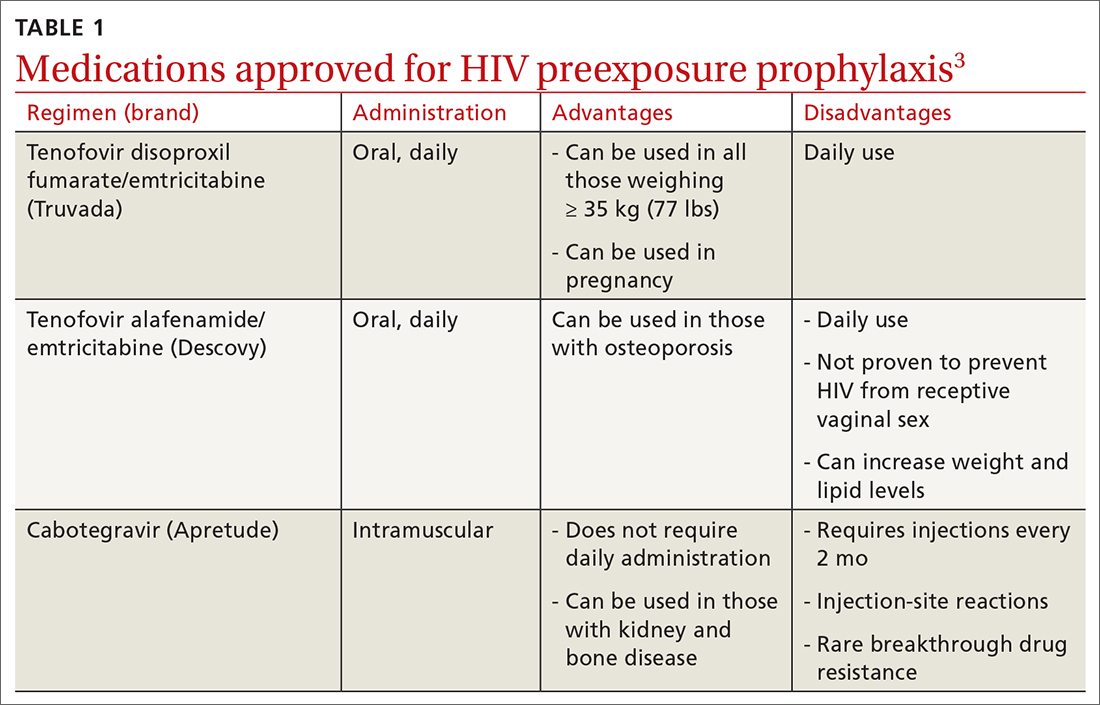

PrEP decreases the risk for HIV by about 50% overall, with higher rates of protection correlated to higher adherence (close to 100% protection with daily adherence to oral regimens).3 The 3 approved regimens for PrEP are outlined in TABLE 13.

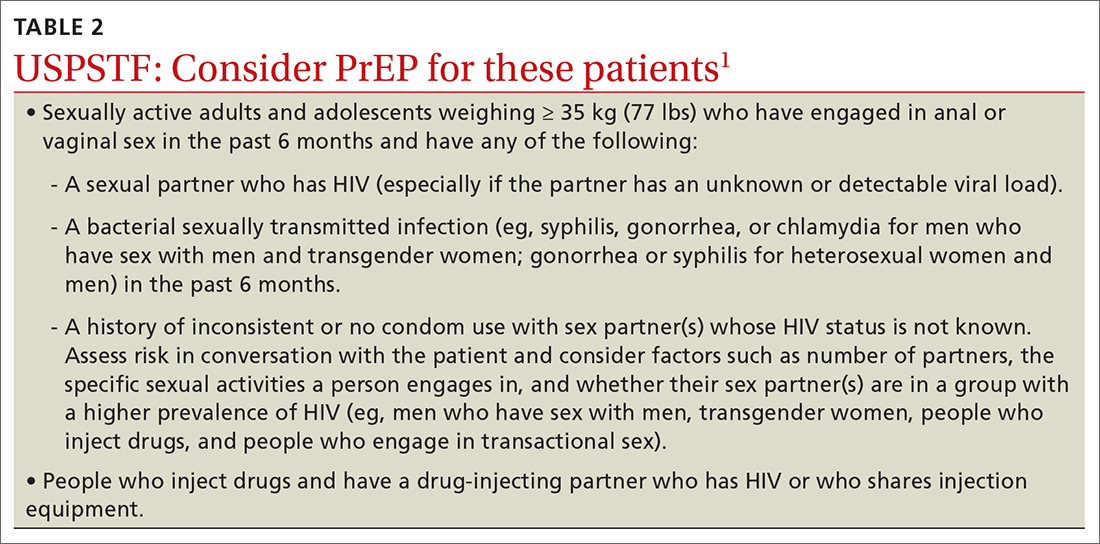

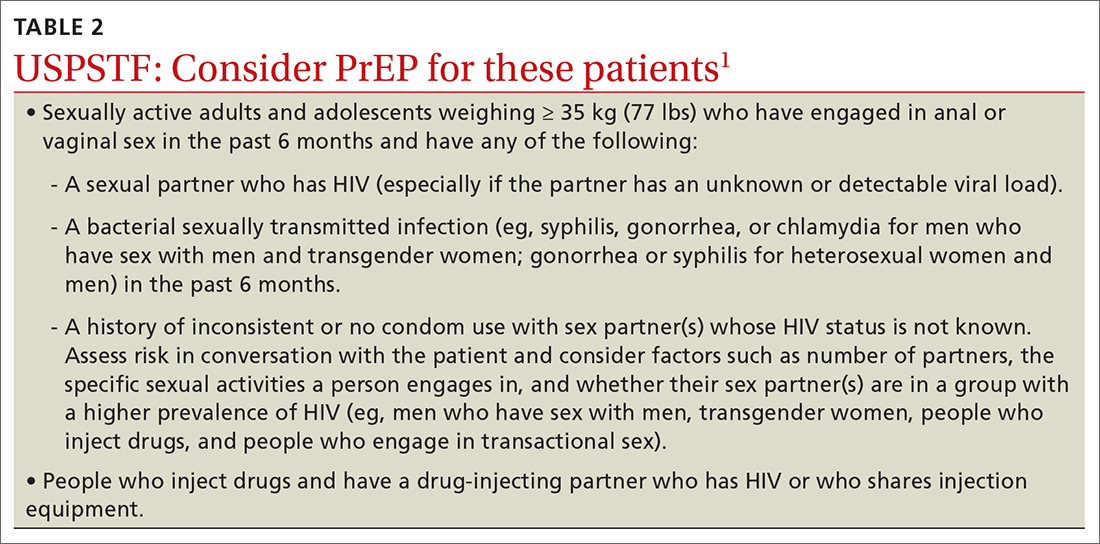

Who’s at increased risk? The USPSTF did not find any risk assessment tools with proven accuracy in identifying those at increased risk for HIV infection but did document risk factors and behaviors that can be used to predict risk. They encourage discussion about HIV prevention with all adults and adolescents who are sexually active or who inject drugs.

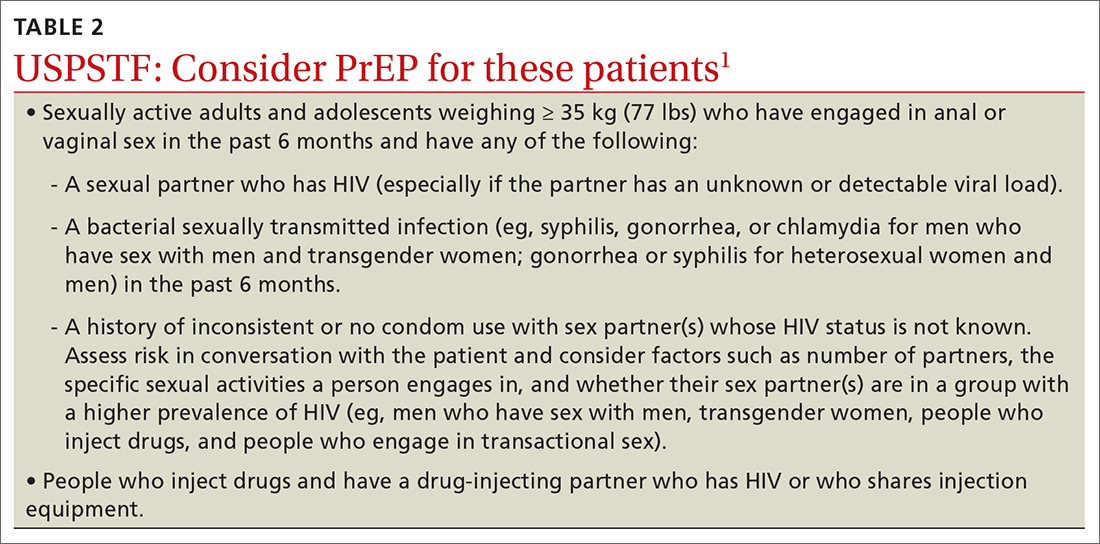

Those people for whom the Task Force recommends considering PrEP are listed in TABLE 21. However, the USPSTF recommends providing PrEP to anyone who requests it, as they may not want to disclose their risk factors.

What to keep in mind. Family physicians are encouraged to read the full USPSTF report and refer to CDC guidelines on prescribing PrEP, which provide details on each regimen and the routine laboratory testing that should be performed.4 The most important clinical considerations described in the USPSTF report are:

- Before starting PrEP, document a negative HIV antigen/antibody test result and continue to test for HIV every 3 months. PrEP regimens should not be used to treat HIV.

- Document a negative HIV RNA assay if the patient has taken oral PrEP in the past 3 months or injectable PrEP in the past 12 months.

- At PrEP initiation, consider ordering other recommended tests, such as those for kidney function, chronic hepatitis B infection (if using tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine), lipid levels (if using tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine), and other sexually transmitted infection (STIs).

- Encourage the use of condoms, as PrEP does not protect from other STIs.

- Follow up regularly, and at each patient visit stress the need for medication adherence to achieve maximum protection.

1. USPSTF. Prevention of acquisition of HIV: preexposure prophylaxis. Final recommendation statement. Published August 22, 2023. Accessed September 28, 2023. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/prevention-of-human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-pre-exposure-prophylaxis

2. CDC. HIV surveillance report: diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2020. Published May 2022. Accessed September 29, 2023. www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2020-updated-vol-33.pdf

3. USPSTF. Prevention of acquisition of HIV: preexposure prophylaxis. Final evidence review. Published August 22, 2023. Accessed September 28, 2023. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/final-evidence-review/prevention-of-human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-pre-exposure-prophylaxis

4. CDC. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2021 update: a clinical practice guideline. Accessed September 28, 2023. www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2021.pdf

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently released their final recommendation update on the use of antiretroviral therapy to prevent HIV infection in adolescents and adults who are at increased risk.1 The Task Force last addressed this topic in 2019; since then, 2 additional antiretroviral regimens have been approved for preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP). The update also includes revised wording on who should consider receiving PrEP.

HIV remains a significant public health problem in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 1.2 million people in the United States are living with HIV, and approximately 30,000 new infections occur each year.2 Men who have sex with men account for 68% of new infections, and there are marked racial disparities in both incidence and prevalence of infection, with Black/African Americans accounting for 42% of new infections.2

PrEP decreases the risk for HIV by about 50% overall, with higher rates of protection correlated to higher adherence (close to 100% protection with daily adherence to oral regimens).3 The 3 approved regimens for PrEP are outlined in TABLE 13.

Who’s at increased risk? The USPSTF did not find any risk assessment tools with proven accuracy in identifying those at increased risk for HIV infection but did document risk factors and behaviors that can be used to predict risk. They encourage discussion about HIV prevention with all adults and adolescents who are sexually active or who inject drugs.

Those people for whom the Task Force recommends considering PrEP are listed in TABLE 21. However, the USPSTF recommends providing PrEP to anyone who requests it, as they may not want to disclose their risk factors.

What to keep in mind. Family physicians are encouraged to read the full USPSTF report and refer to CDC guidelines on prescribing PrEP, which provide details on each regimen and the routine laboratory testing that should be performed.4 The most important clinical considerations described in the USPSTF report are:

- Before starting PrEP, document a negative HIV antigen/antibody test result and continue to test for HIV every 3 months. PrEP regimens should not be used to treat HIV.

- Document a negative HIV RNA assay if the patient has taken oral PrEP in the past 3 months or injectable PrEP in the past 12 months.

- At PrEP initiation, consider ordering other recommended tests, such as those for kidney function, chronic hepatitis B infection (if using tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine), lipid levels (if using tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine), and other sexually transmitted infection (STIs).

- Encourage the use of condoms, as PrEP does not protect from other STIs.

- Follow up regularly, and at each patient visit stress the need for medication adherence to achieve maximum protection.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently released their final recommendation update on the use of antiretroviral therapy to prevent HIV infection in adolescents and adults who are at increased risk.1 The Task Force last addressed this topic in 2019; since then, 2 additional antiretroviral regimens have been approved for preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP). The update also includes revised wording on who should consider receiving PrEP.

HIV remains a significant public health problem in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 1.2 million people in the United States are living with HIV, and approximately 30,000 new infections occur each year.2 Men who have sex with men account for 68% of new infections, and there are marked racial disparities in both incidence and prevalence of infection, with Black/African Americans accounting for 42% of new infections.2

PrEP decreases the risk for HIV by about 50% overall, with higher rates of protection correlated to higher adherence (close to 100% protection with daily adherence to oral regimens).3 The 3 approved regimens for PrEP are outlined in TABLE 13.

Who’s at increased risk? The USPSTF did not find any risk assessment tools with proven accuracy in identifying those at increased risk for HIV infection but did document risk factors and behaviors that can be used to predict risk. They encourage discussion about HIV prevention with all adults and adolescents who are sexually active or who inject drugs.

Those people for whom the Task Force recommends considering PrEP are listed in TABLE 21. However, the USPSTF recommends providing PrEP to anyone who requests it, as they may not want to disclose their risk factors.

What to keep in mind. Family physicians are encouraged to read the full USPSTF report and refer to CDC guidelines on prescribing PrEP, which provide details on each regimen and the routine laboratory testing that should be performed.4 The most important clinical considerations described in the USPSTF report are:

- Before starting PrEP, document a negative HIV antigen/antibody test result and continue to test for HIV every 3 months. PrEP regimens should not be used to treat HIV.

- Document a negative HIV RNA assay if the patient has taken oral PrEP in the past 3 months or injectable PrEP in the past 12 months.

- At PrEP initiation, consider ordering other recommended tests, such as those for kidney function, chronic hepatitis B infection (if using tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine), lipid levels (if using tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine), and other sexually transmitted infection (STIs).

- Encourage the use of condoms, as PrEP does not protect from other STIs.

- Follow up regularly, and at each patient visit stress the need for medication adherence to achieve maximum protection.

1. USPSTF. Prevention of acquisition of HIV: preexposure prophylaxis. Final recommendation statement. Published August 22, 2023. Accessed September 28, 2023. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/prevention-of-human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-pre-exposure-prophylaxis

2. CDC. HIV surveillance report: diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2020. Published May 2022. Accessed September 29, 2023. www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2020-updated-vol-33.pdf

3. USPSTF. Prevention of acquisition of HIV: preexposure prophylaxis. Final evidence review. Published August 22, 2023. Accessed September 28, 2023. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/final-evidence-review/prevention-of-human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-pre-exposure-prophylaxis

4. CDC. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2021 update: a clinical practice guideline. Accessed September 28, 2023. www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2021.pdf

1. USPSTF. Prevention of acquisition of HIV: preexposure prophylaxis. Final recommendation statement. Published August 22, 2023. Accessed September 28, 2023. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/prevention-of-human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-pre-exposure-prophylaxis

2. CDC. HIV surveillance report: diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2020. Published May 2022. Accessed September 29, 2023. www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2020-updated-vol-33.pdf

3. USPSTF. Prevention of acquisition of HIV: preexposure prophylaxis. Final evidence review. Published August 22, 2023. Accessed September 28, 2023. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/document/final-evidence-review/prevention-of-human-immunodeficiency-virus-hiv-infection-pre-exposure-prophylaxis

4. CDC. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2021 update: a clinical practice guideline. Accessed September 28, 2023. www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2021.pdf

Are you ready for RSV season? There’s a new preventive option

There is now an additional option for the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), the most common cause of hospitalization among infants and children in the United States. In July, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved nirsevimab, an RSV preventive monoclonal antibody, for use in neonates and infants born during or entering their first RSV season and in children up to 24 months of age who remain vulnerable to RSV during their second season.1 The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) subsequently made 2 recommendations regarding use of nirsevimab, which I’ll detail in a moment.2

First, a word about RSV. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that each year in children younger than 5 years, RSV is responsible for 1.5 million outpatient clinic visits, 520,000 emergency department visits, 58,000 to 80,000 hospitalizations, and 100 to 200 deaths.2 The risk for hospitalization from RSV is highest in the second and third months of life and decreases with increasing age.

There are some racial disparities in RSV severity, likely reflecting social drivers of health: ICU admission rates are 1.2 to 1.6 times higher among non-Hispanic Black infants younger than 6 months than among non-Hispanic White infants, and hospitalization rates are up to 5 times higher in American Indian and Alaska Native populations.2

What nirsevimab adds to the toolbox. Until recently, there was only 1 RSV preventive agent available: palivizumab, also a monoclonal antibody. The American Academy of Pediatrics has recommended palivizumab be used only for infants at high risk for RSV infection, due to its high cost and the need for monthly injections for the duration of an RSV season. In addition, the Academy has noted that palivizumab has limited effect on RSV hospitalizations on a population basis and does not appear to affect mortality.3

Nirsevimab has a longer half-life than palivizumab, and only 1 injection is needed for the RSV season. Early studies on nirsevimab demonstrate 79% effectiveness in preventing medical-attended lower respiratory tract infection, 80.6% effectiveness in preventing hospitalization, and 90% effectiveness in preventing ICU admission. The number needed to immunize with nirsevimab to prevent an outpatient visit is estimated to be 17; to prevent an ED visit, 48; and to prevent an inpatient admission, 128. Due to the low RSV death rate, the studies were not able to demonstrate reduced mortality.2

What the ACIP recommends. At a special meeting in July, the ACIP recommended 1 dose of nirsevimab for2:

- all infants younger than 8 months who are born during or entering their first RSV season

- children ages 8 to 19 months who are at increased risk for severe RSV disease and entering their second RSV season.