User login

Restructuring health care delivery for the future: What we need to do post–COVID-19

Recently,

Barbara Levy, MD: The disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic has given us an opportunity to consider how we would recraft the delivery of health care for women if we could. My goal for this discussion is to talk about that and see if we can incentivize people to make changes.

Cindy, what are women looking for in health care that they are not getting now?

What women want in health care

Cynthia A. Pearson: Women, like men, want a sense of assurance that health care can be provided in a safe way, and that can’t be given completely right now.

Aside from that, women want a personal connection, ideally with the same provider. Many women are embracing telehealth, which came about because of this disruptive time, and that has potential that we can possibly mobilize around. One thing women don’t always find is consistency and contact, and they would like that.

Scott D. Hayworth, MD: Women want to be listened to, and they want their doctors to take a holistic and individualized approach to their care. In-person visits are the ideal setting for this, but during the pandemic we have had to adapt to new modalities for delivering care: government regulations restricting services, and the necessity to limit the flow of patients into offices, has meant that we have had to rely on remote visits. CareMount Medical has been in the forefront of telehealth with our “Virtual Visit” technology, so we were well prepared, and our patients have embraced this truly vital option. We’ve ramped up capabilities significantly to deal with the surge in volume.

While our practice has been able to provide consistent and convenient access to care, this isn’t the case in all areas of the country. Even before the pandemic, the cost of malpractice insurance has led to shortages of ObGyns; this deficit has been compounded by the closing of hospitals due to restrictions on services imposed to try to stem the spread of COVID-19. The affordability of care has also been jeopardized by job losses and therefore of employer-provided insurance, following months of lockdowns.

Continue to: Dr. Levy...

Dr. Levy: To balance that long-term relationship with access and cost, clearly we are not delivering what is needed. Janice, at UnitedHealth you have experimented with some products and some different ways of delivering care. What are beneficiaries looking for?

Janice Huckaby, MD: There is a real thirst for digital content—everybody consults with Dr. Google. They are looking for reliable sources of clinical content. Ideally, that comes from their physician, but people access it in other ways as well.

I agree that women desire a personalized relationship. That is why we are seeing more communities of women, such as virtual pregnancy support groups, that have cropped up in the age of COVID-19. Women are not content with the idea of “I’m going to see my doctor, get my tummy measured, listen to the heartbeat, and go home.” That model is done. Patients will look for practices that are accessible at convenient times and that can give them the personalized experience to make them feel well cared for and that offer them a long-term relationship.

One concern is that as more obstetric groups use laborists to do their deliveries at the hospital, I wonder whether we do a good job of forming that relationship on the front end, and when it comes to the delivery, will we drop the ball? The jury is out, but it’s worth watching.

Dr. Levy: How do we as obstetrician-gynecologists get patients to consider that we are providing reliable information? There is so much disinformation out there.

Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD, MBA: I echo the sentiments discussed and I’ll add that many women want care that is convenient, close to home, coordinated, and integrated—not fragmented. They want their providers and their office to anticipate and know who they are even before they arrive, to be prepared for the visit. And it’s not only care for them, but also care for their families. Women are the gatekeepers to the health care system. They want a health care system in place that will care not just for each member separately but also for the family as an integrated whole.

To answer your question, Barbara, we have all been overwhelmed with the amount of data coming at us, both providers and patients. Teaching providers how to synthesize and integrate the data and then present it to patients is quite a challenge. We have to instill this skill in our trainees, teach them how to absorb and present the data.

Consensus bodies can help in this regard, and ACOG (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists) has led the way in providing guidance around the management of pregnancy in the setting of COVID-19. Another reliable site for my trainees is UpToDate, which is easy to access. If a scientific paper comes out today, it will be covered in UpToDate tomorrow. Patients need someone who can synthesize the data and give it to them in little pieces, and keep it current.

Dr. Levy: We need to be a reliable source not only for medical information but also for referral to resources in the community for families and for women.

Continue to: ObGyn services...

ObGyn services: Primary care or specialty?

Dr. Norwitz: That begs the question, who are we? Are we primary care providers or are we a subspecialty, or are we both?

Ms. Pearson: Women, particularly in their younger, middle reproductive years, see their ObGyn as a primary care provider. The way forward for the profession is to embrace the call that Barbara articulated, to know what other referral sources are available beyond other clinicians. We need to be aware of the social determinants of health—that there are times when the primary care provider needs to know the community well enough to know what is available that would make a difference for that person and her family.

Dr. Levy: Scott, how do you manage that?

Dr. Hayworth: As reimbursement models move rapidly toward value, practices that can undertake risk are in the best position to thrive; specialty providers relying solely on fee-for-service may well be unable to survive. The key for any ObGyn practice is to be of sufficient size and scope that it can manage the primary care for a panel of patients, the more numerous the better; being in charge of those dollars allows maximum control. ObGyns who subspecialize should seek to become members of larger groups, whether comprehensive women’s health practices or multispecialty groups like ours at CareMount Medical, that manage the spectrum of care for their patients.

Dr. Levy: Janice, fill us in on some of the structures that exist now for ObGyns that they may be able to participate in—payment structures like the Women’s Medical Home. Does UnitedHealth have anything like that?

Dr. Huckaby: Probably 3 or 4 exist now, but I agree that risk arrangements are perhaps a wave of the future. Right now, UnitedHealth has accountable care organizations (ACOs) that include ObGyns, a number of them in the Northeast. We also rolled out bundled payment programs.

Our hospital contracts have always had metrics around infection rates and elective deliveries before 39 weeks, and we will probably start seeing some of that put into the provider contracts as well.

There is a desire to move people into a risk-sharing model for payment, but part of the concern there is the infrastructure, because if you are going to manage risk, you need to have staff that can do care coordination. Care coordinators can ensure, for example, that people have transportation to their appointments, and thus address some of the social determinants in ways that historically have not been done in obstetrics.

The ACOs sometimes have given seed money for practices to hire additional staff to do those kinds of things, and that can help get practices started. Probably the people best positioned are in large multispecialty groups that can leverage case management and maybe support other specialties.

I do think we are going to see a move to risk in the future. Obstetrics has moved at a slower pace than we have seen in internal medicine and some other specialties.

Dr. Hayworth: The value model for reimbursement can only be managed via care coordination, maximizing efficacy and efficiency at every level for every patient. Fortunately for ObGyns, we are familiar with the value concept via bundling for obstetrical services covering prenatal to postpartum, including delivery. ObGyn practices need to prepare for a future in which insurers will pay for patient panels in which providers take on the risk for the entirety of care.

At CareMount Medical, we have embraced the value model as one of 40 Next Generation Medicare Accountable Care Organizations across the country. We’ve put in place the infrastructure, from front desk through back office, to optimize resource utilization. Our team approach includes both patient advocates and care coordinators who extend the capabilities of our physicians and ensure that our patients’ needs, including well care, are met comprehensively.

Dr. Huckaby: One area that we sometimes leave out, whether we are talking about payment or a patient-centered medical home, is integration with behavioral health. Anxiety and depression are fairly rampant, fairly underdiagnosed, and woefully undertreated. I hope that our ObGyn practices of the future—and maybe this is the broadening into primary care—will engage and take the lead in addressing some of those issues, because women suffer. We need to embrace the behavioral aspect of care for the whole person more than we have.

Continue to: Physician training issues...

Physician training issues

Dr. Levy: I could not agree more. We have trained physicians to do illness care, not wellness care, and to be physician and practice centered, not patient centered. While we train medical students in hospital settings and in acute care, there’s not much training in how to manage people or in the factors that determine whether someone is truly well, such as housing security and food security. We are not training physicians in nutrition or in mental health.

Errol, how do we help an ObGyn or women’s health trainee to prepare for the ideal world we are trying to create?

Dr. Norwitz: It’s a challenging question. I like to reference a remarkable piece by Atul Gawande in The New Yorker, in which he interviewed the CEO of the Cheesecake Factory restaurant chain, who in effect said that we’ve got it all wrong; there’s no health in health care.1 We don’t manage health; we wait until people get sick and then we treat them. We have to put the health back into health care.

It has always been my passion to focus on preventative care. We need to reclaim our identity—I have never particularly liked the name “ObGyn,” the term “women’s health” may be more appropriate and help us focus on disease prevention—and we need to stand up for training programs that separate the O from the G.

Low-volume surgeons, who may do only 1 or 2 hysterectomies per year, can’t maintain their proficiency, and many don’t do enough cases to maintain their robotics privileges. I can foresee a time where labor and delivery units are like ICUs, where the people who work there do nothing but manage labor and perform deliveries using standardized bundles of practice. Such an approach will decrease variability in management and lead to improved outcomes.

We need to completely reframe how we train our pipeline providers to provide care in women’s health. It would be difficult, take a lot of effort, and there would be pushback, I suspect, but that’s where the field needs to go.

The ideal system redesign

Dr. Levy: Cindy, if you could start from scratch and design an ideal comprehensive system to better deliver care for women of all ages, what would that look like?

Ms. Pearson: I would design a system in which people at any life stage met with providers who were less trained in dealing with disease and more trained in the holistic approach to maintaining health. That might be a nurse practitioner or maybe a version of what Errol describes as a new way of training ObGyns. That’s the initial interaction, and the person could be with someone for decades and deepen the relationship in that wonderful way. It would also have an avenue for the times when disease needed to be treated or when more specialized care would be provided. And the financing would be worked out to support consistency.

Dr. Norwitz: We can learn from other countries. Singapore, with only 5.5 million people, has the best health care system in the world. They have a great model. Costa Rica and Cuba have completely redesigned their health care systems. You go through medical school in 2 or 3 years, and then you get embedded in the community. So you have doctors living in the community responsible for the health of their neighbors. They get to know people in the context in which they live and refer them on only when they need more than basic care. These countries have vastly superior outcome measures, and they spend less money on health care.

Dr. Levy: My dream, as we reinvent things, is that we could create a comprehensive Women’s Medical Home where there’s a hub and an opportunity to be centered on patients so they could reach us when needed.

Ideally we could create a structure with a central contact person—a nurse practitioner, a midwife, someone in family medicine or internal medicine—someone focused on women’s health who has researched how inequities apply to women and women’s health and the areas where research doesn’t necessarily apply to women as just “smaller men.” Then we would have the hub, and the spokes—those would be mental health care providers, surgeons, and people to provide additional services when needed.

The only way I can figure how to make that work from a payment perspective is with a prospective payment system, a per member, per month capitated payment structure. That way, ancillary and other services would be available, and overtesting and such would be disincentivized.

Continue to: The question of payment...

The question of payment

Dr. Hayworth: I agree. For every practice, the two key considerations in addressing the challenges of capitation are, first, that the team approach is essential, and, second, that providers appreciate that everything they do for their patients is reimbursed in a global payment.

At CareMount Medical, our team system embeds advanced practice professionals in our primary care and ObGyn offices. Everyone—physicians, midwives, nurse practitioners—practices at the top of their license. Our care coordinators ensure that our patients’ health journeys are optimized from well care through specialized needs, engaging every member of the care team effectively.

To optimize our success in a risk model, we recognize that tasks and services that went without direct reimbursement in a fee-for-service arrangement are integral to producing the best outcomes for our patients. We examine everything we do from the perspective of how to provide the most advanced care in the most efficient manner. For example, we drive toward moving procedures from the hospital to the outpatient setting, and from the ambulatory surgical center to the office. This allows us maximal control of both quality and cost, with savings benefiting our group as well as the payers with whom we have contracts.

Dr. Norwitz: I have been fortunate to have trained and worked in 5 different countries on 3 continents. There’s no question there are better health care systems out there. Some form of capitation is needed, whether it’s value-based care or a risk-sharing arrangement. But how do you do it without a single payer? I don’t think you can, but I’m ready to listen.

Dr. Hayworth: You can have capitation without a single payer; in fact, it’s far better to have many payers compete to offer the greatest flexibility to both patients and providers. CareMount Medical has 650,000 patients who rely on us to provide their care with the utmost quality and affordability. In our Next Generation ACO, our Medicare patients have the benefit of care coordination in a team approach that saves our government money, and we are incentivized to do our best because some of those savings return to us.

The needs of Medicare patients, of course, are different from those in other age groups, and our contracts with other payers will reflect that distinction. There’s no inherent reason why capitation has to equal “single payer.” The benefits of the risk model are magnified by incentivizing all participants to provide maximum value.

Continue to: Ms. Pearson...

Ms. Pearson: I am going to comment on capitated care because I think educated consumers are well aware of the benefits of moving away from fee-for-service and bringing in some more sensible system. However, given the historical racial inequities and injustices, and lack of access and disparate treatment, capitation raises fear in the hearts of people whose communities have not gotten the care that they need.

The answer is not to avoid capitation, but to find a way for the profession to be seen more visibly as reflecting who they serve, and we know we can’t change the profession’s racial makeup overnight. That’s a generation-long effort.

Dr. Levy: For capitation to work, there has to be value, you have to meet the quality metrics. Having served on the National Quality Forum on multiple different committees, I am convinced that we measure what is easy to measure, and we are not measuring what really matters to people. My thought is to embrace the communities that have been underserved to help us design the metrics for a capitated system that is meaningful to the people that we serve.

Ms. Pearson: On the West Coast, some people are leading efforts to create patient-centered metrics for respectful maternity care led by Black, indigenous, and people of color communities that are validated with solid research tools.

Algorithms for care

Dr. Norwitz: Artificial intelligence (AI) may have a role to play. For example, I think we do a terrible job of caring for women in the postpartum period. We focus almost all of our care in the antepartum period and not postpartum. I am working with a group with a finance and banking background to try and risk-adjust patients in the antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum period. We are developing algorithms using AI and deep learning technologies to risk-stratify patients and say, “This patient is low risk so can safely get obstetric care with a family medicine doctor or midwife. That patient requires consultation with a maternal-fetal medicine subspecialist or a general internist,” and so on.

Ms. Pearson: As policy advocates, we are trying to get Medicaid postpartum coverage expanded to 12 months. Too many women fall into a coverage gap shortly after delivery; continued coverage would help improve postpartum outcomes. I am curious how an algorithm might help take better care of women postpartum.

Dr. Norwitz: Postpartum care is one of the greatest areas of need. I love the Dutch model. In the Netherlands, when a woman goes home after giving birth, a designated nurse comes home with her, teaches her how to breastfeed and how to bathe the baby, and assists with routine activities such as cooking and washing. And the nurse remains engaged for a prolonged period of time, paid for by the government. There are also other social welfare packages, such as a full 4-year or more maternity leave.

The solution is part political and part medical. We need to rethink our care model, and I don’t think we provide enough postpartum care.

Continue to: Dr. Hayworth...

Dr. Hayworth: Errol made an excellent point about AI. There is a product that’s being used in Europe and in some other parts of the world that can provide 85% of care through an algorithm without a patient even having to speak to a nurse or doctor. The company that offers the product claims a high level of patient satisfaction and a very low error rate.

We are a long way from the point at which—and I don’t anticipate that we’ll ever get there—AI fully replaces human providers, but there’s enormous and growing potential for data aggregation and machine learning to enhance, exponentially, the capabilities and capacity of care teams.

The most immediate applications for AI in the United States are in diagnostics, pathology, and the mapping of protocols for patients with cancer who will benefit from access to investigational interventions and clinical trials. As we gain experience in those areas, acceptance and confidence will lead steadily to broader deployment of AI, enhancing the quality of care and the efficiency of delivery and saving costs.

Dr. Norwitz: AI is a tool to assist providers. It is not going to replace us, which is the fear.

Ms. Pearson: From the consumer perspective, again, there is concern that if not enough data are available from Black, indigenous, and people of color, the levels won’t start out in a good place. The criticism over mammography randomized controlled trials (RCTs) has existed for a long time. The big trials that got all the way out to mortality did not include enough women of color; and so women of color rightly say, “Why should we believe these guidelines developed on results of the RCTs?” My point is that because of historical inequity, logical solutions such as algorithms do not always work for communities that were previously excluded or mistreated.

Dr. Levy: Your point is incredibly well taken. That means that those of us researching and working with AI need to ensure that the data going in are representative, that we are not embedding implicit biases into the AI algorithms, which clearly has sometimes already happened. We have to be careful to embrace input from multiple sources that we have not thought of before.

As we look at an algorithm for managing a postpartum patient or a postoperative patient, have we thought about how she’s managing her children at home after she goes home? What else is happening in her life? How can we impact her recovery in a positive way? We need to hear the voices of the people that we are trying to serve as we develop those algorithms.

Perspectives on future health care delivery

Dr. Levy: To summarize so far, we are thinking about a Woman’s Medical Home, a capitated model of comprehensive care for women that includes mental health, social determinants, and home care. There are different models, but a payment structure where we would have the capital to invest in community services and in things that we think may make a difference.

Dr. Norwitz: I think the health care system of the future is not going to be based in large academic medical centers. It’s going to be in community hospitals close to home. It’s going to be in the home. And it will be provided by different types of practitioners, whose performances are tracked using more appropriate outcome metrics.

Dr. Levy: I also think we will have community health workers. While we haven’t talked about rural health and access to care, there are some structural things we can do to reach rural communities with really excellent care, such as training community health workers and using telemedicine. It does require thinking through a different payment structure, though, because there really isn’t money in the system to do that currently, at least to my knowledge.

Janice, do we have enough motivation to take care of women? Women are so underrepresented when we look at care models.

Dr. Huckaby: I do think there is hope, but it will truly take a village. While CMS (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) has its innovation center in the Medicaid space, it’s almost like we have to have the payers, the government, the specialty societies, and so on say that we need to do something better. I mention the government because it is not only a payer but also a regulator. They can help create some of these things.

There are opportunities with payers to say, “Let’s move to this kind of model for that.” But still, we are implementing change but on a fairly minor scale.

We could have the people who care about issues, help deliver the care, pay the bills, and so on say, “This is what we want to do,” and then we could pilot them. It may be one type of pilot in a rural area and one type of pilot in an urban area, because they are going to differ, and do it that way and then scale it.

Telemedicine, or telehealth, is part of creating access. Even some nontraditional settings, such as retail store clinics, may work.

Continue to: Dr. Levy...

Dr. Levy: Cindy, is there any last thing you wanted to comment on?

Ms. Pearson: All the changes we have talked about require public policy change. Physicians become physicians to take care of people, not because they want to be policy wonks like us. We love policy because we see how it can benefit. To our readers I say be part of making this generational change in the profession and women’s health care, get involved in policy, because these things can’t happen without the policy changes.

Dr. Norwitz: That is so important. In most developed countries around the world, you get trained in medical school, the cost of training is subsidized, and in return you owe 2 years of service. In this country, if we subsidized the training of doctors and in return they owed us 2 years of primary care service based in the community or in an underserved area, they would get valuable clinical experience and wouldn’t have so many loans to pay back. I think it is a policy that could work and could profoundly change the health care landscape in time.

Dr. Levy: And it would save a great deal of money. The reality is that if we subsidize medical education and in return required service in a national public health service, we would move providers out into rural areas. That would to some extent solve our rural problem. We would train people to think about diagnostic options when the resources are not unlimited, so that they will perhaps not order quite so many tests.

That policy change would foundationally allow for more minority students to become physicians and health care workers. If there were one thing we could do to begin to drive this change, that would be it.

Who would have thought a disruptive pandemic could affect the way people receive care, in bad and good ways? Some carriers, for example, are now paying for telehealth visits who previously did not.

Final thoughts

Dr. Hayworth: It’s an exciting time to be in medicine and women’s health: We are ushering in a new era in which we can fulfill the vision of comprehensive care, patient-focused and seamlessly delivered by teams whose capabilities are optimized by ever-improving technology. ObGyns, with our foundation in the continuum of care, have the experience and the sensibilities to adapt to the challenges of the value model, in which our success will depend on fully embracing our role as primary care providers.

Dr. Levy: Circling back to the beginning of our discussion, we talked about relationships, and developing deep relationships with patients is the internal reward and the piece that prevents us from burnout. It makes you feel good at the end of the day—or sometimes bad at the end of the day when something didn’t go well. Restructuring the system in a way that gets us back to personalized relationship-centered care will benefit ObGyns and our patients.

I thank you all for participating in this thoughtful discussion. ●

- Gawande A. Big med. The New Yorker. August 13, 2012. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2012/08/13/big-med. Accessed July 24, 2020.

Recently,

Barbara Levy, MD: The disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic has given us an opportunity to consider how we would recraft the delivery of health care for women if we could. My goal for this discussion is to talk about that and see if we can incentivize people to make changes.

Cindy, what are women looking for in health care that they are not getting now?

What women want in health care

Cynthia A. Pearson: Women, like men, want a sense of assurance that health care can be provided in a safe way, and that can’t be given completely right now.

Aside from that, women want a personal connection, ideally with the same provider. Many women are embracing telehealth, which came about because of this disruptive time, and that has potential that we can possibly mobilize around. One thing women don’t always find is consistency and contact, and they would like that.

Scott D. Hayworth, MD: Women want to be listened to, and they want their doctors to take a holistic and individualized approach to their care. In-person visits are the ideal setting for this, but during the pandemic we have had to adapt to new modalities for delivering care: government regulations restricting services, and the necessity to limit the flow of patients into offices, has meant that we have had to rely on remote visits. CareMount Medical has been in the forefront of telehealth with our “Virtual Visit” technology, so we were well prepared, and our patients have embraced this truly vital option. We’ve ramped up capabilities significantly to deal with the surge in volume.

While our practice has been able to provide consistent and convenient access to care, this isn’t the case in all areas of the country. Even before the pandemic, the cost of malpractice insurance has led to shortages of ObGyns; this deficit has been compounded by the closing of hospitals due to restrictions on services imposed to try to stem the spread of COVID-19. The affordability of care has also been jeopardized by job losses and therefore of employer-provided insurance, following months of lockdowns.

Continue to: Dr. Levy...

Dr. Levy: To balance that long-term relationship with access and cost, clearly we are not delivering what is needed. Janice, at UnitedHealth you have experimented with some products and some different ways of delivering care. What are beneficiaries looking for?

Janice Huckaby, MD: There is a real thirst for digital content—everybody consults with Dr. Google. They are looking for reliable sources of clinical content. Ideally, that comes from their physician, but people access it in other ways as well.

I agree that women desire a personalized relationship. That is why we are seeing more communities of women, such as virtual pregnancy support groups, that have cropped up in the age of COVID-19. Women are not content with the idea of “I’m going to see my doctor, get my tummy measured, listen to the heartbeat, and go home.” That model is done. Patients will look for practices that are accessible at convenient times and that can give them the personalized experience to make them feel well cared for and that offer them a long-term relationship.

One concern is that as more obstetric groups use laborists to do their deliveries at the hospital, I wonder whether we do a good job of forming that relationship on the front end, and when it comes to the delivery, will we drop the ball? The jury is out, but it’s worth watching.

Dr. Levy: How do we as obstetrician-gynecologists get patients to consider that we are providing reliable information? There is so much disinformation out there.

Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD, MBA: I echo the sentiments discussed and I’ll add that many women want care that is convenient, close to home, coordinated, and integrated—not fragmented. They want their providers and their office to anticipate and know who they are even before they arrive, to be prepared for the visit. And it’s not only care for them, but also care for their families. Women are the gatekeepers to the health care system. They want a health care system in place that will care not just for each member separately but also for the family as an integrated whole.

To answer your question, Barbara, we have all been overwhelmed with the amount of data coming at us, both providers and patients. Teaching providers how to synthesize and integrate the data and then present it to patients is quite a challenge. We have to instill this skill in our trainees, teach them how to absorb and present the data.

Consensus bodies can help in this regard, and ACOG (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists) has led the way in providing guidance around the management of pregnancy in the setting of COVID-19. Another reliable site for my trainees is UpToDate, which is easy to access. If a scientific paper comes out today, it will be covered in UpToDate tomorrow. Patients need someone who can synthesize the data and give it to them in little pieces, and keep it current.

Dr. Levy: We need to be a reliable source not only for medical information but also for referral to resources in the community for families and for women.

Continue to: ObGyn services...

ObGyn services: Primary care or specialty?

Dr. Norwitz: That begs the question, who are we? Are we primary care providers or are we a subspecialty, or are we both?

Ms. Pearson: Women, particularly in their younger, middle reproductive years, see their ObGyn as a primary care provider. The way forward for the profession is to embrace the call that Barbara articulated, to know what other referral sources are available beyond other clinicians. We need to be aware of the social determinants of health—that there are times when the primary care provider needs to know the community well enough to know what is available that would make a difference for that person and her family.

Dr. Levy: Scott, how do you manage that?

Dr. Hayworth: As reimbursement models move rapidly toward value, practices that can undertake risk are in the best position to thrive; specialty providers relying solely on fee-for-service may well be unable to survive. The key for any ObGyn practice is to be of sufficient size and scope that it can manage the primary care for a panel of patients, the more numerous the better; being in charge of those dollars allows maximum control. ObGyns who subspecialize should seek to become members of larger groups, whether comprehensive women’s health practices or multispecialty groups like ours at CareMount Medical, that manage the spectrum of care for their patients.

Dr. Levy: Janice, fill us in on some of the structures that exist now for ObGyns that they may be able to participate in—payment structures like the Women’s Medical Home. Does UnitedHealth have anything like that?

Dr. Huckaby: Probably 3 or 4 exist now, but I agree that risk arrangements are perhaps a wave of the future. Right now, UnitedHealth has accountable care organizations (ACOs) that include ObGyns, a number of them in the Northeast. We also rolled out bundled payment programs.

Our hospital contracts have always had metrics around infection rates and elective deliveries before 39 weeks, and we will probably start seeing some of that put into the provider contracts as well.

There is a desire to move people into a risk-sharing model for payment, but part of the concern there is the infrastructure, because if you are going to manage risk, you need to have staff that can do care coordination. Care coordinators can ensure, for example, that people have transportation to their appointments, and thus address some of the social determinants in ways that historically have not been done in obstetrics.

The ACOs sometimes have given seed money for practices to hire additional staff to do those kinds of things, and that can help get practices started. Probably the people best positioned are in large multispecialty groups that can leverage case management and maybe support other specialties.

I do think we are going to see a move to risk in the future. Obstetrics has moved at a slower pace than we have seen in internal medicine and some other specialties.

Dr. Hayworth: The value model for reimbursement can only be managed via care coordination, maximizing efficacy and efficiency at every level for every patient. Fortunately for ObGyns, we are familiar with the value concept via bundling for obstetrical services covering prenatal to postpartum, including delivery. ObGyn practices need to prepare for a future in which insurers will pay for patient panels in which providers take on the risk for the entirety of care.

At CareMount Medical, we have embraced the value model as one of 40 Next Generation Medicare Accountable Care Organizations across the country. We’ve put in place the infrastructure, from front desk through back office, to optimize resource utilization. Our team approach includes both patient advocates and care coordinators who extend the capabilities of our physicians and ensure that our patients’ needs, including well care, are met comprehensively.

Dr. Huckaby: One area that we sometimes leave out, whether we are talking about payment or a patient-centered medical home, is integration with behavioral health. Anxiety and depression are fairly rampant, fairly underdiagnosed, and woefully undertreated. I hope that our ObGyn practices of the future—and maybe this is the broadening into primary care—will engage and take the lead in addressing some of those issues, because women suffer. We need to embrace the behavioral aspect of care for the whole person more than we have.

Continue to: Physician training issues...

Physician training issues

Dr. Levy: I could not agree more. We have trained physicians to do illness care, not wellness care, and to be physician and practice centered, not patient centered. While we train medical students in hospital settings and in acute care, there’s not much training in how to manage people or in the factors that determine whether someone is truly well, such as housing security and food security. We are not training physicians in nutrition or in mental health.

Errol, how do we help an ObGyn or women’s health trainee to prepare for the ideal world we are trying to create?

Dr. Norwitz: It’s a challenging question. I like to reference a remarkable piece by Atul Gawande in The New Yorker, in which he interviewed the CEO of the Cheesecake Factory restaurant chain, who in effect said that we’ve got it all wrong; there’s no health in health care.1 We don’t manage health; we wait until people get sick and then we treat them. We have to put the health back into health care.

It has always been my passion to focus on preventative care. We need to reclaim our identity—I have never particularly liked the name “ObGyn,” the term “women’s health” may be more appropriate and help us focus on disease prevention—and we need to stand up for training programs that separate the O from the G.

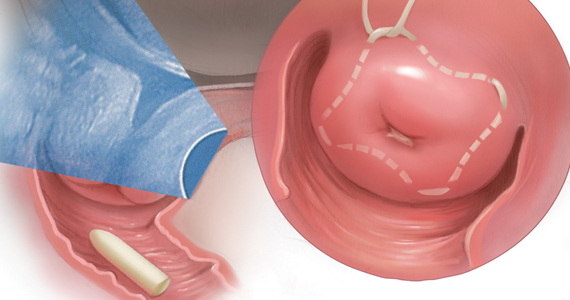

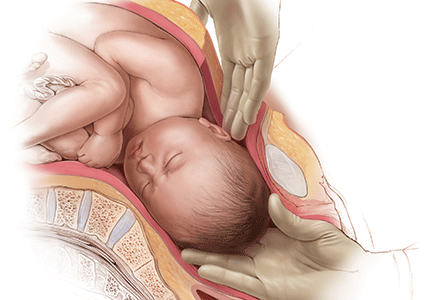

Low-volume surgeons, who may do only 1 or 2 hysterectomies per year, can’t maintain their proficiency, and many don’t do enough cases to maintain their robotics privileges. I can foresee a time where labor and delivery units are like ICUs, where the people who work there do nothing but manage labor and perform deliveries using standardized bundles of practice. Such an approach will decrease variability in management and lead to improved outcomes.

We need to completely reframe how we train our pipeline providers to provide care in women’s health. It would be difficult, take a lot of effort, and there would be pushback, I suspect, but that’s where the field needs to go.

The ideal system redesign

Dr. Levy: Cindy, if you could start from scratch and design an ideal comprehensive system to better deliver care for women of all ages, what would that look like?

Ms. Pearson: I would design a system in which people at any life stage met with providers who were less trained in dealing with disease and more trained in the holistic approach to maintaining health. That might be a nurse practitioner or maybe a version of what Errol describes as a new way of training ObGyns. That’s the initial interaction, and the person could be with someone for decades and deepen the relationship in that wonderful way. It would also have an avenue for the times when disease needed to be treated or when more specialized care would be provided. And the financing would be worked out to support consistency.

Dr. Norwitz: We can learn from other countries. Singapore, with only 5.5 million people, has the best health care system in the world. They have a great model. Costa Rica and Cuba have completely redesigned their health care systems. You go through medical school in 2 or 3 years, and then you get embedded in the community. So you have doctors living in the community responsible for the health of their neighbors. They get to know people in the context in which they live and refer them on only when they need more than basic care. These countries have vastly superior outcome measures, and they spend less money on health care.

Dr. Levy: My dream, as we reinvent things, is that we could create a comprehensive Women’s Medical Home where there’s a hub and an opportunity to be centered on patients so they could reach us when needed.

Ideally we could create a structure with a central contact person—a nurse practitioner, a midwife, someone in family medicine or internal medicine—someone focused on women’s health who has researched how inequities apply to women and women’s health and the areas where research doesn’t necessarily apply to women as just “smaller men.” Then we would have the hub, and the spokes—those would be mental health care providers, surgeons, and people to provide additional services when needed.

The only way I can figure how to make that work from a payment perspective is with a prospective payment system, a per member, per month capitated payment structure. That way, ancillary and other services would be available, and overtesting and such would be disincentivized.

Continue to: The question of payment...

The question of payment

Dr. Hayworth: I agree. For every practice, the two key considerations in addressing the challenges of capitation are, first, that the team approach is essential, and, second, that providers appreciate that everything they do for their patients is reimbursed in a global payment.

At CareMount Medical, our team system embeds advanced practice professionals in our primary care and ObGyn offices. Everyone—physicians, midwives, nurse practitioners—practices at the top of their license. Our care coordinators ensure that our patients’ health journeys are optimized from well care through specialized needs, engaging every member of the care team effectively.

To optimize our success in a risk model, we recognize that tasks and services that went without direct reimbursement in a fee-for-service arrangement are integral to producing the best outcomes for our patients. We examine everything we do from the perspective of how to provide the most advanced care in the most efficient manner. For example, we drive toward moving procedures from the hospital to the outpatient setting, and from the ambulatory surgical center to the office. This allows us maximal control of both quality and cost, with savings benefiting our group as well as the payers with whom we have contracts.

Dr. Norwitz: I have been fortunate to have trained and worked in 5 different countries on 3 continents. There’s no question there are better health care systems out there. Some form of capitation is needed, whether it’s value-based care or a risk-sharing arrangement. But how do you do it without a single payer? I don’t think you can, but I’m ready to listen.

Dr. Hayworth: You can have capitation without a single payer; in fact, it’s far better to have many payers compete to offer the greatest flexibility to both patients and providers. CareMount Medical has 650,000 patients who rely on us to provide their care with the utmost quality and affordability. In our Next Generation ACO, our Medicare patients have the benefit of care coordination in a team approach that saves our government money, and we are incentivized to do our best because some of those savings return to us.

The needs of Medicare patients, of course, are different from those in other age groups, and our contracts with other payers will reflect that distinction. There’s no inherent reason why capitation has to equal “single payer.” The benefits of the risk model are magnified by incentivizing all participants to provide maximum value.

Continue to: Ms. Pearson...

Ms. Pearson: I am going to comment on capitated care because I think educated consumers are well aware of the benefits of moving away from fee-for-service and bringing in some more sensible system. However, given the historical racial inequities and injustices, and lack of access and disparate treatment, capitation raises fear in the hearts of people whose communities have not gotten the care that they need.

The answer is not to avoid capitation, but to find a way for the profession to be seen more visibly as reflecting who they serve, and we know we can’t change the profession’s racial makeup overnight. That’s a generation-long effort.

Dr. Levy: For capitation to work, there has to be value, you have to meet the quality metrics. Having served on the National Quality Forum on multiple different committees, I am convinced that we measure what is easy to measure, and we are not measuring what really matters to people. My thought is to embrace the communities that have been underserved to help us design the metrics for a capitated system that is meaningful to the people that we serve.

Ms. Pearson: On the West Coast, some people are leading efforts to create patient-centered metrics for respectful maternity care led by Black, indigenous, and people of color communities that are validated with solid research tools.

Algorithms for care

Dr. Norwitz: Artificial intelligence (AI) may have a role to play. For example, I think we do a terrible job of caring for women in the postpartum period. We focus almost all of our care in the antepartum period and not postpartum. I am working with a group with a finance and banking background to try and risk-adjust patients in the antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum period. We are developing algorithms using AI and deep learning technologies to risk-stratify patients and say, “This patient is low risk so can safely get obstetric care with a family medicine doctor or midwife. That patient requires consultation with a maternal-fetal medicine subspecialist or a general internist,” and so on.

Ms. Pearson: As policy advocates, we are trying to get Medicaid postpartum coverage expanded to 12 months. Too many women fall into a coverage gap shortly after delivery; continued coverage would help improve postpartum outcomes. I am curious how an algorithm might help take better care of women postpartum.

Dr. Norwitz: Postpartum care is one of the greatest areas of need. I love the Dutch model. In the Netherlands, when a woman goes home after giving birth, a designated nurse comes home with her, teaches her how to breastfeed and how to bathe the baby, and assists with routine activities such as cooking and washing. And the nurse remains engaged for a prolonged period of time, paid for by the government. There are also other social welfare packages, such as a full 4-year or more maternity leave.

The solution is part political and part medical. We need to rethink our care model, and I don’t think we provide enough postpartum care.

Continue to: Dr. Hayworth...

Dr. Hayworth: Errol made an excellent point about AI. There is a product that’s being used in Europe and in some other parts of the world that can provide 85% of care through an algorithm without a patient even having to speak to a nurse or doctor. The company that offers the product claims a high level of patient satisfaction and a very low error rate.

We are a long way from the point at which—and I don’t anticipate that we’ll ever get there—AI fully replaces human providers, but there’s enormous and growing potential for data aggregation and machine learning to enhance, exponentially, the capabilities and capacity of care teams.

The most immediate applications for AI in the United States are in diagnostics, pathology, and the mapping of protocols for patients with cancer who will benefit from access to investigational interventions and clinical trials. As we gain experience in those areas, acceptance and confidence will lead steadily to broader deployment of AI, enhancing the quality of care and the efficiency of delivery and saving costs.

Dr. Norwitz: AI is a tool to assist providers. It is not going to replace us, which is the fear.

Ms. Pearson: From the consumer perspective, again, there is concern that if not enough data are available from Black, indigenous, and people of color, the levels won’t start out in a good place. The criticism over mammography randomized controlled trials (RCTs) has existed for a long time. The big trials that got all the way out to mortality did not include enough women of color; and so women of color rightly say, “Why should we believe these guidelines developed on results of the RCTs?” My point is that because of historical inequity, logical solutions such as algorithms do not always work for communities that were previously excluded or mistreated.

Dr. Levy: Your point is incredibly well taken. That means that those of us researching and working with AI need to ensure that the data going in are representative, that we are not embedding implicit biases into the AI algorithms, which clearly has sometimes already happened. We have to be careful to embrace input from multiple sources that we have not thought of before.

As we look at an algorithm for managing a postpartum patient or a postoperative patient, have we thought about how she’s managing her children at home after she goes home? What else is happening in her life? How can we impact her recovery in a positive way? We need to hear the voices of the people that we are trying to serve as we develop those algorithms.

Perspectives on future health care delivery

Dr. Levy: To summarize so far, we are thinking about a Woman’s Medical Home, a capitated model of comprehensive care for women that includes mental health, social determinants, and home care. There are different models, but a payment structure where we would have the capital to invest in community services and in things that we think may make a difference.

Dr. Norwitz: I think the health care system of the future is not going to be based in large academic medical centers. It’s going to be in community hospitals close to home. It’s going to be in the home. And it will be provided by different types of practitioners, whose performances are tracked using more appropriate outcome metrics.

Dr. Levy: I also think we will have community health workers. While we haven’t talked about rural health and access to care, there are some structural things we can do to reach rural communities with really excellent care, such as training community health workers and using telemedicine. It does require thinking through a different payment structure, though, because there really isn’t money in the system to do that currently, at least to my knowledge.

Janice, do we have enough motivation to take care of women? Women are so underrepresented when we look at care models.

Dr. Huckaby: I do think there is hope, but it will truly take a village. While CMS (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) has its innovation center in the Medicaid space, it’s almost like we have to have the payers, the government, the specialty societies, and so on say that we need to do something better. I mention the government because it is not only a payer but also a regulator. They can help create some of these things.

There are opportunities with payers to say, “Let’s move to this kind of model for that.” But still, we are implementing change but on a fairly minor scale.

We could have the people who care about issues, help deliver the care, pay the bills, and so on say, “This is what we want to do,” and then we could pilot them. It may be one type of pilot in a rural area and one type of pilot in an urban area, because they are going to differ, and do it that way and then scale it.

Telemedicine, or telehealth, is part of creating access. Even some nontraditional settings, such as retail store clinics, may work.

Continue to: Dr. Levy...

Dr. Levy: Cindy, is there any last thing you wanted to comment on?

Ms. Pearson: All the changes we have talked about require public policy change. Physicians become physicians to take care of people, not because they want to be policy wonks like us. We love policy because we see how it can benefit. To our readers I say be part of making this generational change in the profession and women’s health care, get involved in policy, because these things can’t happen without the policy changes.

Dr. Norwitz: That is so important. In most developed countries around the world, you get trained in medical school, the cost of training is subsidized, and in return you owe 2 years of service. In this country, if we subsidized the training of doctors and in return they owed us 2 years of primary care service based in the community or in an underserved area, they would get valuable clinical experience and wouldn’t have so many loans to pay back. I think it is a policy that could work and could profoundly change the health care landscape in time.

Dr. Levy: And it would save a great deal of money. The reality is that if we subsidize medical education and in return required service in a national public health service, we would move providers out into rural areas. That would to some extent solve our rural problem. We would train people to think about diagnostic options when the resources are not unlimited, so that they will perhaps not order quite so many tests.

That policy change would foundationally allow for more minority students to become physicians and health care workers. If there were one thing we could do to begin to drive this change, that would be it.

Who would have thought a disruptive pandemic could affect the way people receive care, in bad and good ways? Some carriers, for example, are now paying for telehealth visits who previously did not.

Final thoughts

Dr. Hayworth: It’s an exciting time to be in medicine and women’s health: We are ushering in a new era in which we can fulfill the vision of comprehensive care, patient-focused and seamlessly delivered by teams whose capabilities are optimized by ever-improving technology. ObGyns, with our foundation in the continuum of care, have the experience and the sensibilities to adapt to the challenges of the value model, in which our success will depend on fully embracing our role as primary care providers.

Dr. Levy: Circling back to the beginning of our discussion, we talked about relationships, and developing deep relationships with patients is the internal reward and the piece that prevents us from burnout. It makes you feel good at the end of the day—or sometimes bad at the end of the day when something didn’t go well. Restructuring the system in a way that gets us back to personalized relationship-centered care will benefit ObGyns and our patients.

I thank you all for participating in this thoughtful discussion. ●

Recently,

Barbara Levy, MD: The disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic has given us an opportunity to consider how we would recraft the delivery of health care for women if we could. My goal for this discussion is to talk about that and see if we can incentivize people to make changes.

Cindy, what are women looking for in health care that they are not getting now?

What women want in health care

Cynthia A. Pearson: Women, like men, want a sense of assurance that health care can be provided in a safe way, and that can’t be given completely right now.

Aside from that, women want a personal connection, ideally with the same provider. Many women are embracing telehealth, which came about because of this disruptive time, and that has potential that we can possibly mobilize around. One thing women don’t always find is consistency and contact, and they would like that.

Scott D. Hayworth, MD: Women want to be listened to, and they want their doctors to take a holistic and individualized approach to their care. In-person visits are the ideal setting for this, but during the pandemic we have had to adapt to new modalities for delivering care: government regulations restricting services, and the necessity to limit the flow of patients into offices, has meant that we have had to rely on remote visits. CareMount Medical has been in the forefront of telehealth with our “Virtual Visit” technology, so we were well prepared, and our patients have embraced this truly vital option. We’ve ramped up capabilities significantly to deal with the surge in volume.

While our practice has been able to provide consistent and convenient access to care, this isn’t the case in all areas of the country. Even before the pandemic, the cost of malpractice insurance has led to shortages of ObGyns; this deficit has been compounded by the closing of hospitals due to restrictions on services imposed to try to stem the spread of COVID-19. The affordability of care has also been jeopardized by job losses and therefore of employer-provided insurance, following months of lockdowns.

Continue to: Dr. Levy...

Dr. Levy: To balance that long-term relationship with access and cost, clearly we are not delivering what is needed. Janice, at UnitedHealth you have experimented with some products and some different ways of delivering care. What are beneficiaries looking for?

Janice Huckaby, MD: There is a real thirst for digital content—everybody consults with Dr. Google. They are looking for reliable sources of clinical content. Ideally, that comes from their physician, but people access it in other ways as well.

I agree that women desire a personalized relationship. That is why we are seeing more communities of women, such as virtual pregnancy support groups, that have cropped up in the age of COVID-19. Women are not content with the idea of “I’m going to see my doctor, get my tummy measured, listen to the heartbeat, and go home.” That model is done. Patients will look for practices that are accessible at convenient times and that can give them the personalized experience to make them feel well cared for and that offer them a long-term relationship.

One concern is that as more obstetric groups use laborists to do their deliveries at the hospital, I wonder whether we do a good job of forming that relationship on the front end, and when it comes to the delivery, will we drop the ball? The jury is out, but it’s worth watching.

Dr. Levy: How do we as obstetrician-gynecologists get patients to consider that we are providing reliable information? There is so much disinformation out there.

Errol R. Norwitz, MD, PhD, MBA: I echo the sentiments discussed and I’ll add that many women want care that is convenient, close to home, coordinated, and integrated—not fragmented. They want their providers and their office to anticipate and know who they are even before they arrive, to be prepared for the visit. And it’s not only care for them, but also care for their families. Women are the gatekeepers to the health care system. They want a health care system in place that will care not just for each member separately but also for the family as an integrated whole.

To answer your question, Barbara, we have all been overwhelmed with the amount of data coming at us, both providers and patients. Teaching providers how to synthesize and integrate the data and then present it to patients is quite a challenge. We have to instill this skill in our trainees, teach them how to absorb and present the data.

Consensus bodies can help in this regard, and ACOG (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists) has led the way in providing guidance around the management of pregnancy in the setting of COVID-19. Another reliable site for my trainees is UpToDate, which is easy to access. If a scientific paper comes out today, it will be covered in UpToDate tomorrow. Patients need someone who can synthesize the data and give it to them in little pieces, and keep it current.

Dr. Levy: We need to be a reliable source not only for medical information but also for referral to resources in the community for families and for women.

Continue to: ObGyn services...

ObGyn services: Primary care or specialty?

Dr. Norwitz: That begs the question, who are we? Are we primary care providers or are we a subspecialty, or are we both?

Ms. Pearson: Women, particularly in their younger, middle reproductive years, see their ObGyn as a primary care provider. The way forward for the profession is to embrace the call that Barbara articulated, to know what other referral sources are available beyond other clinicians. We need to be aware of the social determinants of health—that there are times when the primary care provider needs to know the community well enough to know what is available that would make a difference for that person and her family.

Dr. Levy: Scott, how do you manage that?

Dr. Hayworth: As reimbursement models move rapidly toward value, practices that can undertake risk are in the best position to thrive; specialty providers relying solely on fee-for-service may well be unable to survive. The key for any ObGyn practice is to be of sufficient size and scope that it can manage the primary care for a panel of patients, the more numerous the better; being in charge of those dollars allows maximum control. ObGyns who subspecialize should seek to become members of larger groups, whether comprehensive women’s health practices or multispecialty groups like ours at CareMount Medical, that manage the spectrum of care for their patients.

Dr. Levy: Janice, fill us in on some of the structures that exist now for ObGyns that they may be able to participate in—payment structures like the Women’s Medical Home. Does UnitedHealth have anything like that?

Dr. Huckaby: Probably 3 or 4 exist now, but I agree that risk arrangements are perhaps a wave of the future. Right now, UnitedHealth has accountable care organizations (ACOs) that include ObGyns, a number of them in the Northeast. We also rolled out bundled payment programs.

Our hospital contracts have always had metrics around infection rates and elective deliveries before 39 weeks, and we will probably start seeing some of that put into the provider contracts as well.

There is a desire to move people into a risk-sharing model for payment, but part of the concern there is the infrastructure, because if you are going to manage risk, you need to have staff that can do care coordination. Care coordinators can ensure, for example, that people have transportation to their appointments, and thus address some of the social determinants in ways that historically have not been done in obstetrics.

The ACOs sometimes have given seed money for practices to hire additional staff to do those kinds of things, and that can help get practices started. Probably the people best positioned are in large multispecialty groups that can leverage case management and maybe support other specialties.

I do think we are going to see a move to risk in the future. Obstetrics has moved at a slower pace than we have seen in internal medicine and some other specialties.

Dr. Hayworth: The value model for reimbursement can only be managed via care coordination, maximizing efficacy and efficiency at every level for every patient. Fortunately for ObGyns, we are familiar with the value concept via bundling for obstetrical services covering prenatal to postpartum, including delivery. ObGyn practices need to prepare for a future in which insurers will pay for patient panels in which providers take on the risk for the entirety of care.

At CareMount Medical, we have embraced the value model as one of 40 Next Generation Medicare Accountable Care Organizations across the country. We’ve put in place the infrastructure, from front desk through back office, to optimize resource utilization. Our team approach includes both patient advocates and care coordinators who extend the capabilities of our physicians and ensure that our patients’ needs, including well care, are met comprehensively.

Dr. Huckaby: One area that we sometimes leave out, whether we are talking about payment or a patient-centered medical home, is integration with behavioral health. Anxiety and depression are fairly rampant, fairly underdiagnosed, and woefully undertreated. I hope that our ObGyn practices of the future—and maybe this is the broadening into primary care—will engage and take the lead in addressing some of those issues, because women suffer. We need to embrace the behavioral aspect of care for the whole person more than we have.

Continue to: Physician training issues...

Physician training issues

Dr. Levy: I could not agree more. We have trained physicians to do illness care, not wellness care, and to be physician and practice centered, not patient centered. While we train medical students in hospital settings and in acute care, there’s not much training in how to manage people or in the factors that determine whether someone is truly well, such as housing security and food security. We are not training physicians in nutrition or in mental health.

Errol, how do we help an ObGyn or women’s health trainee to prepare for the ideal world we are trying to create?

Dr. Norwitz: It’s a challenging question. I like to reference a remarkable piece by Atul Gawande in The New Yorker, in which he interviewed the CEO of the Cheesecake Factory restaurant chain, who in effect said that we’ve got it all wrong; there’s no health in health care.1 We don’t manage health; we wait until people get sick and then we treat them. We have to put the health back into health care.

It has always been my passion to focus on preventative care. We need to reclaim our identity—I have never particularly liked the name “ObGyn,” the term “women’s health” may be more appropriate and help us focus on disease prevention—and we need to stand up for training programs that separate the O from the G.

Low-volume surgeons, who may do only 1 or 2 hysterectomies per year, can’t maintain their proficiency, and many don’t do enough cases to maintain their robotics privileges. I can foresee a time where labor and delivery units are like ICUs, where the people who work there do nothing but manage labor and perform deliveries using standardized bundles of practice. Such an approach will decrease variability in management and lead to improved outcomes.

We need to completely reframe how we train our pipeline providers to provide care in women’s health. It would be difficult, take a lot of effort, and there would be pushback, I suspect, but that’s where the field needs to go.

The ideal system redesign

Dr. Levy: Cindy, if you could start from scratch and design an ideal comprehensive system to better deliver care for women of all ages, what would that look like?

Ms. Pearson: I would design a system in which people at any life stage met with providers who were less trained in dealing with disease and more trained in the holistic approach to maintaining health. That might be a nurse practitioner or maybe a version of what Errol describes as a new way of training ObGyns. That’s the initial interaction, and the person could be with someone for decades and deepen the relationship in that wonderful way. It would also have an avenue for the times when disease needed to be treated or when more specialized care would be provided. And the financing would be worked out to support consistency.

Dr. Norwitz: We can learn from other countries. Singapore, with only 5.5 million people, has the best health care system in the world. They have a great model. Costa Rica and Cuba have completely redesigned their health care systems. You go through medical school in 2 or 3 years, and then you get embedded in the community. So you have doctors living in the community responsible for the health of their neighbors. They get to know people in the context in which they live and refer them on only when they need more than basic care. These countries have vastly superior outcome measures, and they spend less money on health care.

Dr. Levy: My dream, as we reinvent things, is that we could create a comprehensive Women’s Medical Home where there’s a hub and an opportunity to be centered on patients so they could reach us when needed.

Ideally we could create a structure with a central contact person—a nurse practitioner, a midwife, someone in family medicine or internal medicine—someone focused on women’s health who has researched how inequities apply to women and women’s health and the areas where research doesn’t necessarily apply to women as just “smaller men.” Then we would have the hub, and the spokes—those would be mental health care providers, surgeons, and people to provide additional services when needed.

The only way I can figure how to make that work from a payment perspective is with a prospective payment system, a per member, per month capitated payment structure. That way, ancillary and other services would be available, and overtesting and such would be disincentivized.

Continue to: The question of payment...

The question of payment

Dr. Hayworth: I agree. For every practice, the two key considerations in addressing the challenges of capitation are, first, that the team approach is essential, and, second, that providers appreciate that everything they do for their patients is reimbursed in a global payment.

At CareMount Medical, our team system embeds advanced practice professionals in our primary care and ObGyn offices. Everyone—physicians, midwives, nurse practitioners—practices at the top of their license. Our care coordinators ensure that our patients’ health journeys are optimized from well care through specialized needs, engaging every member of the care team effectively.

To optimize our success in a risk model, we recognize that tasks and services that went without direct reimbursement in a fee-for-service arrangement are integral to producing the best outcomes for our patients. We examine everything we do from the perspective of how to provide the most advanced care in the most efficient manner. For example, we drive toward moving procedures from the hospital to the outpatient setting, and from the ambulatory surgical center to the office. This allows us maximal control of both quality and cost, with savings benefiting our group as well as the payers with whom we have contracts.

Dr. Norwitz: I have been fortunate to have trained and worked in 5 different countries on 3 continents. There’s no question there are better health care systems out there. Some form of capitation is needed, whether it’s value-based care or a risk-sharing arrangement. But how do you do it without a single payer? I don’t think you can, but I’m ready to listen.

Dr. Hayworth: You can have capitation without a single payer; in fact, it’s far better to have many payers compete to offer the greatest flexibility to both patients and providers. CareMount Medical has 650,000 patients who rely on us to provide their care with the utmost quality and affordability. In our Next Generation ACO, our Medicare patients have the benefit of care coordination in a team approach that saves our government money, and we are incentivized to do our best because some of those savings return to us.

The needs of Medicare patients, of course, are different from those in other age groups, and our contracts with other payers will reflect that distinction. There’s no inherent reason why capitation has to equal “single payer.” The benefits of the risk model are magnified by incentivizing all participants to provide maximum value.

Continue to: Ms. Pearson...

Ms. Pearson: I am going to comment on capitated care because I think educated consumers are well aware of the benefits of moving away from fee-for-service and bringing in some more sensible system. However, given the historical racial inequities and injustices, and lack of access and disparate treatment, capitation raises fear in the hearts of people whose communities have not gotten the care that they need.

The answer is not to avoid capitation, but to find a way for the profession to be seen more visibly as reflecting who they serve, and we know we can’t change the profession’s racial makeup overnight. That’s a generation-long effort.

Dr. Levy: For capitation to work, there has to be value, you have to meet the quality metrics. Having served on the National Quality Forum on multiple different committees, I am convinced that we measure what is easy to measure, and we are not measuring what really matters to people. My thought is to embrace the communities that have been underserved to help us design the metrics for a capitated system that is meaningful to the people that we serve.

Ms. Pearson: On the West Coast, some people are leading efforts to create patient-centered metrics for respectful maternity care led by Black, indigenous, and people of color communities that are validated with solid research tools.

Algorithms for care

Dr. Norwitz: Artificial intelligence (AI) may have a role to play. For example, I think we do a terrible job of caring for women in the postpartum period. We focus almost all of our care in the antepartum period and not postpartum. I am working with a group with a finance and banking background to try and risk-adjust patients in the antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum period. We are developing algorithms using AI and deep learning technologies to risk-stratify patients and say, “This patient is low risk so can safely get obstetric care with a family medicine doctor or midwife. That patient requires consultation with a maternal-fetal medicine subspecialist or a general internist,” and so on.

Ms. Pearson: As policy advocates, we are trying to get Medicaid postpartum coverage expanded to 12 months. Too many women fall into a coverage gap shortly after delivery; continued coverage would help improve postpartum outcomes. I am curious how an algorithm might help take better care of women postpartum.

Dr. Norwitz: Postpartum care is one of the greatest areas of need. I love the Dutch model. In the Netherlands, when a woman goes home after giving birth, a designated nurse comes home with her, teaches her how to breastfeed and how to bathe the baby, and assists with routine activities such as cooking and washing. And the nurse remains engaged for a prolonged period of time, paid for by the government. There are also other social welfare packages, such as a full 4-year or more maternity leave.

The solution is part political and part medical. We need to rethink our care model, and I don’t think we provide enough postpartum care.

Continue to: Dr. Hayworth...

Dr. Hayworth: Errol made an excellent point about AI. There is a product that’s being used in Europe and in some other parts of the world that can provide 85% of care through an algorithm without a patient even having to speak to a nurse or doctor. The company that offers the product claims a high level of patient satisfaction and a very low error rate.

We are a long way from the point at which—and I don’t anticipate that we’ll ever get there—AI fully replaces human providers, but there’s enormous and growing potential for data aggregation and machine learning to enhance, exponentially, the capabilities and capacity of care teams.

The most immediate applications for AI in the United States are in diagnostics, pathology, and the mapping of protocols for patients with cancer who will benefit from access to investigational interventions and clinical trials. As we gain experience in those areas, acceptance and confidence will lead steadily to broader deployment of AI, enhancing the quality of care and the efficiency of delivery and saving costs.

Dr. Norwitz: AI is a tool to assist providers. It is not going to replace us, which is the fear.

Ms. Pearson: From the consumer perspective, again, there is concern that if not enough data are available from Black, indigenous, and people of color, the levels won’t start out in a good place. The criticism over mammography randomized controlled trials (RCTs) has existed for a long time. The big trials that got all the way out to mortality did not include enough women of color; and so women of color rightly say, “Why should we believe these guidelines developed on results of the RCTs?” My point is that because of historical inequity, logical solutions such as algorithms do not always work for communities that were previously excluded or mistreated.

Dr. Levy: Your point is incredibly well taken. That means that those of us researching and working with AI need to ensure that the data going in are representative, that we are not embedding implicit biases into the AI algorithms, which clearly has sometimes already happened. We have to be careful to embrace input from multiple sources that we have not thought of before.

As we look at an algorithm for managing a postpartum patient or a postoperative patient, have we thought about how she’s managing her children at home after she goes home? What else is happening in her life? How can we impact her recovery in a positive way? We need to hear the voices of the people that we are trying to serve as we develop those algorithms.

Perspectives on future health care delivery

Dr. Levy: To summarize so far, we are thinking about a Woman’s Medical Home, a capitated model of comprehensive care for women that includes mental health, social determinants, and home care. There are different models, but a payment structure where we would have the capital to invest in community services and in things that we think may make a difference.

Dr. Norwitz: I think the health care system of the future is not going to be based in large academic medical centers. It’s going to be in community hospitals close to home. It’s going to be in the home. And it will be provided by different types of practitioners, whose performances are tracked using more appropriate outcome metrics.