User login

Implementation of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Guidelines in an Urban Pediatric Primary Care Clinic

From the Children’s National Health System, Washington, DC (Dr. Manget, Dr. Kelley, Dr. White) and the Duke University School of Nursing, Durham, NC (Dr. Blood-Siegfried).

Abstract

- Background: Approximately 11% of children in the United States ages 4 to 17 have received the diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD). There are disproportionately higher rates of the diagnosis and fewer child psychiatrists available in underserved areas. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) strongly encourages improved mental health competencies among primary care providers to combat this shortage.

- Objective: To improve primary care providers’ knowledge and confidence with the management of ADHD and institute an evidence-based process for assessing patients presenting with behavior concerns suggestive of ADHD.

- Methods: Three in-person educational sessions were conducted for primary care providers by a child psychiatrist to increase providers’ knowledge and confidence in the evaluation and management of ADHD. A Behavior Management Plan was also adopted for use in the clinic. Providers were encouraged to use the plan during patient visits for behavior concerns indicative of ADHD. Pre- and post-test surveys were given to providers to assess change in comfort level with managing ADHD. Patient charts were reviewed to determine how often the Behavior Management Plan was utilized.

- Results: We did not find significant changes in provider comfort in managing ADHD according to the survey results, although providers reported that the educational sessions and handouts were useful. Behavior Management Plans were utilized during 13 of 25 (52%) eligible visits.

- Conclusions: Behavior Management Plans were introduced in just over half of relevant visits. Further exploration about barriers to use of the plan and its utility to patients and families should be pursued in the future. Additionally, ongoing opportunities for continuing education and collaboration with psychiatry should continue to be sought.

Keywords: attention-deficit hyperactive disorder; ADHD; AAP clinical guidelines; underserved populations; disadvantaged communities.

The importance of the mental health of a child cannot be underestimated. Untreated symptoms of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) can significantly interfere with school and social functioning [1]. Children with ADHD often have comorbid conditions such as anxiety, low self-esteem and learning disabilities. It is vital to screen and treat for ADHD and comorbidities early and comprehensively [2].

There are disproportionately higher rates of children diagnosed with ADHD living in underserved areas compared to other geographical regions [3]. The historically underserved Southeast region of Washington D.C. which encompasses Wards 7 and 8 is home to nearly 40% of the district’s children and has the highest rates of children with an ADHD diagnosis in D.C.; however, the majority of child psychiatrists are located in the Northwest regions [4]. In 2009, nearly 8% of children in Washington D.C. were reported to have a diagnosis of ADHD [1].

Due to the overwhelming demand and limited availability of child psychiatrists, it is important that primary care providers become better equipped to diagnose, treat, and manage non-complex cases of ADHD. Specific education about ADHD diagnosis and management along with implementation of standardized center-based processes may help primary care providers feel more comfortable caring for these patients and ensure that all patients presenting with behavior concerns are adequately assessed and treated.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that primary care providers expand their mental health competencies because pediatric primary care providers in the medical home will be the first point of access in most cases [5]. In 2011, the AAP Subcommittee on ADHD and Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management released clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of ADHD [6]. These guidelines, which recommend that providers should initiate ADHD assessments for children ages 6 to 12 that present with behavioral and/or academic problems, have been incorporated into “Caring for Children with ADHD: A Resource Toolkit for Clinicians” by the AAP in partnership with the National Institute on Children’s Health Quality (NICHQ) and North Carolina’s Center for Child Health.

Our clinic has two on-site psychiatrists who provide evaluation and treatment of mental health problems in children identified by primary care providers for a combined total of 1.5 days each week. The current wait for psychiatric evaluation at our clinic is 2 to 3 months, which leaves the primary care providers to care for many children with behavior concerns who require more immediate intervention at the time of their presentation. Our clinic providers revealed that they felt there were deficits in the management of behavior concerns and initiating treatment for patients diagnosed with ADHD in the clinic. Providers expressed an interest in refreshing and enhancing their knowledge related to managing patients with ADHD.

To address this issue, we initiated a quality improvement project with several facets: provide ADHD education to primary care providers through use of educational sessions from our on-site psychiatrists, standardize the process of managing patients that present with behavior concerns to the primary care provider in the medical home, and develop a comprehensive and individualized patient management plan based on the “Caring for Children with ADHD” toolkit for clinicians.

Methods

Setting

This project took place in a federally qualified health center located in the Southeast quadrant of Washington, D.C. that serves patients up to 23 years of age. The clinic has 6 primary care medical providers (5 physicians and 1 nurse practitioner) employed in a part-time to full-time capacity. Additionally, 2 child psychiatrists provide services on-site during one full day and one half-day session on a weekly basis. Approximately 98% of patients at the clinic are classified as African American and close to 95% of patients are insured by Medicaid. Approximately 9% of patients in our clinic had a medical diagnosis of ADHD as of 2015.

Patients who presented to the clinic in April and May 2017 who had an existing diagnosis of ADHD and those with documentation of a new behavior concern in the assessment and treatment plan were studied. Eligible visit types were annual well-child checks, new consults for behavior, and follow-up appointments specifically for behavior.

This was a project undertaken as a quality improvement initiative at the hosting facility and did not constitute human subjects research. As such, it was not under the oversight of the institutional review board.

Intervention

Provider Education. Three in-person sessions were held at the clinic during April–May 2017 to provide education on the assessment and treatment of patients with ADHD and discuss challenges that have arisen when providing care for such patients. The sessions focused on diagnosing ADHD and teasing out comorbidities; initiating and titrating medications safely; educational rights; and strategies for managing behavior and community resources.

Current providers as well as medical residents and student trainees of the clinic were invited to attend the educational sessions. Each session followed a “lunch and learn” format where one of the clinic psychiatrists presented the information during the clinic lunch hour then related a discussion where participants asked questions. The information provided was derived from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5) and the AAP/NICHQ Toolkit [5]. Educational handouts were disseminated during the provider sessions and emailed to all providers afterwards.

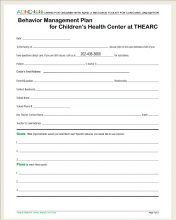

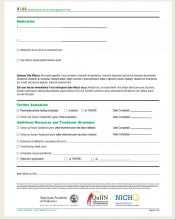

Behavior Management Plan. In March we introduced the providers to the Behavior Management Plan (Figure),

Providers were encouraged to initiate the Behavior Management Plan for patients that presented without an existing diagnosis for evaluation of their behavior concerns. The plan could also be used for patients that had previously been diagnosed with ADHD if changes were being made to their treatment plan or as a summary of their established treatment details. Instructions on the use of the plan were given to all clinic primary care providers through email communication as well as in the first in-person educational session. It was stressed to providers that formulating individual patient goals and the inclusion of a specific follow-up time were the most important aspects of the plan.

Assessment and Measurements

We assessed provider comfort in their ADHD evaluation and management skills before and after the intervention using a 5–point Likert scale questionnaire with 0 indicating “not comfortable at all” and 5 corresponding to “very comfortable.” The questionnaire was administered via a paper survey for the initial screening and an electronic survey at the conclusion of the intervention.

Patient charts were reviewed in July 2017 to determine how often the Behavior Management Plan was utilized. Provider documentation in the electronic medical record indicating that the Plan was given during the patient visit was considered utilization of the plan. We also examined documentation of dissemination/return of Vanderbilt ADHD assessment scales, referrals to psychiatry or counseling, and the initiation or refill of an ADHD medication during the encounter for all patients that were seen for behavior concerns. Patient data were obtained from manual chart review of the electronic medical record, eClinicalWorks.

Analysis

SPSS Statistics (Version 24) was used to conduct analyses. Independent sample t tests were employed to measure items related to the provider educational sessions. Mean provider responses for each item were reviewed from descriptive statistics. A chi-square cross tabulation was used to compare the percentage of patients receiving a Behavior Management Plan that adhered to follow-up visits versus a similar sample of patients that presented in 2016 before the introduction of the Behavior Management Plan. In addition, a chi-square cross tabulation was utilized to compare adherence to follow-up visits in those that received the Management Plan to that of eligible patients that presented during the same time period but did not receive the Plan. Additional chi-square tests were run to see if there was any difference in 2017 follow-up rates based on individual provider or visit type .

Results

Provider Questionnaire

Six providers responded to the pre-intervention questionnaire and five to the post-intervention questionnaire. The specific questions and their results are listed in Table 1.

Patient Management

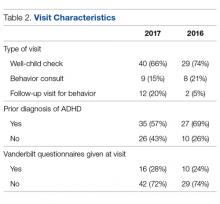

Between April and May 2017, 61 eligible patients presented to the clinic. Details of the breakdown of patient visit type are displayed in Table 2.

Follow-up Rates

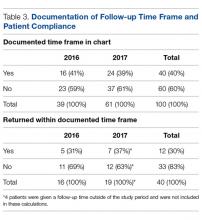

Notation of a specific time frame for follow-up by a primary care provider was found in 24 of 61 (39%) relevant patient charts (Table 3).

Further cross-tabulations were completed to assess if there were better follow-up rates for patients that received a Behavior Management Plan. The difference between the 2 groups was not significant (P = 0.99). There were no significant differences found in follow-up rates based on the provider for the visit (P = 0.51) or the type of patient visit (well child examination vs. behavior consult) (P = 0.65).

Discussion

This project aimed to improve provider confidence in the assessment and treatment of ADHD and improve ADHD management by providers at our clinic. We did not find significant changes in confidence according to the survey results. However, provider feedback indicated that, as a result of the educational sessions, they had a deeper appreciation for the presence of psychiatric comorbidities and the role they play in deciding appropriate treatment. They also reported that they more fully understood the need to refer to child psychiatry for evaluation and management when comorbidities are present instead of attempting to independently provide ADHD medication.

We hoped to see the Behavior Management Plan used for patients with new behavior concerns during the evaluation for ADHD. During the intervention period, it was used in half of eligible clinic visits of patients without a prior diagnosis of ADHD. Future investigation should be directed at receiving specific input on the utility of the Behavior Management Plan from providers and families. The Management Plan contains important reminders and treatment information; however, if the plan is not perceived as effective or useful, taking the time needed to complete it may be seen as an additional cumbersome step in the already overloaded clinic visits.

The use of the Behavior Management Plan was not found to make a statistically significant difference in follow-up rates. Attendance at follow-up appointments for ADHD patients is not an area that has been greatly studied. In a recent analysis of ADHD treatment quality in Medicaid-enrolled children, African American families were less likely to have adequate follow-up compared to Caucasian counterparts during the initiation or continuation and management phases of treatment. The review of specific follow-through rates showed that African Americans were 22% more likely to discontinue medication therapy and 13% more likely to disengage from treatment. The authors propose that future efforts focus on improving accessibility of behavioral therapy to combat the discontinuation rates and disparities in this area [8]. Another study that looked at a prospective cohort of ADHD patients found suboptimal attendance at appointments with a median of 1 visit every 6 months [9]. Further exploration of the challenges with attendance at follow-up appointments is warranted to help determine best practices for ADHD management in disadvantaged communities. More information is needed on the specific barriers to care in this subgroup at our clinic. However, data from this project related to adherence to follow-up appointments can be used to guide future studies.

Use of a Behavior Management Plan was not found to influence the return of completed teacher Vanderbilt scales by families. The rates of return of these assessment forms continue to be very low. Without input from teachers and schools, it is difficult to properly diagnose, treat and evaluate the treatment of patients. Feedback from all sources is essential for both medication management and construction of interventions for behavioral challenges at school. The development of partnerships with a child’s school may be useful in helping patients return for the treatment of behavior concerns at their initial stages. Before children are expelled multiple times due to their behavior, schools should strongly encourage parents to notify their healthcare provider of behavior concerns for evaluation.

In an ideal system, school-based nurses, guidance counselors or social workers could provide some case management and outreach to families of children with known behavior concerns to ensure they are attending appointments as recommended by their treatment plan and explore barriers to doing so. Social workers can provide direct mental health care services and make referrals to community agencies. However, the caseload for school-based providers is currently quite high and many children slip through the cracks until their behavior escalates to a dangerous and/or very disruptive level. School-based personnel in several districts are now required to split their time in multiple schools. Dang et al describe the piloting of a school-based framework for early identification and assessment of children suspected to have ADHD. The framework, called ADHD Identification and Management in Schools (AIMS), encourages school nurses to gather all parent and teacher assessment materials prior to the initial visit to their primary care providers thus reducing the number of visits needed and leading to faster diagnosis and treatment [10].

Clinic-based case managers solely dedicated to this population would also be useful. These case managers could provide management as described above and also potentially sit-in on clinic visits for behavior concerns so that they are fully aware of the instructions given by the provider. This would also give them the information needed so that they are able to complete forms such as the Behavior Management Plan, which would be helpful in relieving some provider time. Geltman et al trialed a workflow intervention with electronic Vanderbilt scales and an electronic registry managed by a care coordination team of a physician, nurse and medical assistant. This allowed patient calls to the families by the nurse or medical assistant to remind them of necessary follow-up and monthly meetings with the care coordination team. Those in the intervention group with the care coordination team were twice as likely to return the Vanderbilt questionnaires. During the intervention period, the rates of follow-up visits remained the same; however, when the intervention was further adopted and expanded to other sites, follow-up attendance improved to over 90% [11].

Limitations

Limitations of this project include the short time period in which it was conducted as well as the size of the study sample. Provider work schedules also caused some challenges with arranging the lunch and learn educational sessions and completing independent review of materials on the subject. This project focused on a primarily African American, predominately Medicaid population. Within urban and/or underserved populations, there may be other demographic distributions thus limiting the generalizability of these findings.

Summary

In summary, this project attempted to improve provider confidence in management of ADHD and standardize assessment practices of one urban pediatric clinic. At the project’s conclusion there were subjective improvements in provider confidence. Ongoing opportunities for continuing education on management of mental health diagnoses for primary care providers should persevere. This project also highlights the persistent problem of patient follow-up for behavior concerns. Further exploration of challenges with attendance at follow-up appointments including collaboration with community and academic resources is needed to help determine best practices for ADHD management in disadvantaged communities.

Corresponding author: Jaytoya C. Manget, DNP, MSPH, FNP, jmanget@childrensnational.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Visser SN, Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, et al. Trends in the parent-report of health care provider-diagnosed and medicated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: United States, 2003-2011. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry 2014;53:34–46.

2. Charach A, Dashti B, Carson P, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effectiveness of treatment in at-risk preschoolers; long-term effectiveness in all ages; and variability in prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011.

3. John M. Eisenberg Center for Clinical Decisions and Communications Science. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. 2012 Jun 26. Comparative Effectiveness Review Summary Guides for Clinicians [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007-2012.

4. Wotring JR, O’Grady KA, Anthony BJ, et al. Behavioral health for children, youth and families in the District of Columbia: A review of prevalence, service utilization, barriers, and recommendations. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development, National Technical Assistance Center for Children’s Mental Health; 2014.

5. American Academy of Pediatrics. Caring for children with ADHD: a resource toolkit for clinicians. [CD-ROM] Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2011.

6. American Academy of Pediatrics, Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactive Disorder, Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management. ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2011;128:1007–22.

7. American Academy of Pediatrics and National Institute for Children’s Healthcare Quality. NICQH Vanderbilt Assessment Scales: Used for diagnosing ADHD. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2002.

8. Cummings JR, Ji X, Allen L, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in ADHD treatment quality among Medicaid-enrolled youth. Pediatrics 2017;139(6).

9. Gardner W, Kelleher KJ, Pajer K, Campo, JV. Follow-up care of children identified with ADHD by primary care clinicians: A prospective cohort study. J Pediatrics 2004;145:767–71.

10. Dang MT, Warrington D, Tung T, et al. A school-based approach to early identification and management of students with ADHD. J Sch Nurs 2007:2–12.

11. Geltman PL, Fried LE, Arsenault LN, et al. A planned care approach and patient registry to improve adherence to clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Acad Pediatrics 2015;15:289–96.

From the Children’s National Health System, Washington, DC (Dr. Manget, Dr. Kelley, Dr. White) and the Duke University School of Nursing, Durham, NC (Dr. Blood-Siegfried).

Abstract

- Background: Approximately 11% of children in the United States ages 4 to 17 have received the diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD). There are disproportionately higher rates of the diagnosis and fewer child psychiatrists available in underserved areas. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) strongly encourages improved mental health competencies among primary care providers to combat this shortage.

- Objective: To improve primary care providers’ knowledge and confidence with the management of ADHD and institute an evidence-based process for assessing patients presenting with behavior concerns suggestive of ADHD.

- Methods: Three in-person educational sessions were conducted for primary care providers by a child psychiatrist to increase providers’ knowledge and confidence in the evaluation and management of ADHD. A Behavior Management Plan was also adopted for use in the clinic. Providers were encouraged to use the plan during patient visits for behavior concerns indicative of ADHD. Pre- and post-test surveys were given to providers to assess change in comfort level with managing ADHD. Patient charts were reviewed to determine how often the Behavior Management Plan was utilized.

- Results: We did not find significant changes in provider comfort in managing ADHD according to the survey results, although providers reported that the educational sessions and handouts were useful. Behavior Management Plans were utilized during 13 of 25 (52%) eligible visits.

- Conclusions: Behavior Management Plans were introduced in just over half of relevant visits. Further exploration about barriers to use of the plan and its utility to patients and families should be pursued in the future. Additionally, ongoing opportunities for continuing education and collaboration with psychiatry should continue to be sought.

Keywords: attention-deficit hyperactive disorder; ADHD; AAP clinical guidelines; underserved populations; disadvantaged communities.

The importance of the mental health of a child cannot be underestimated. Untreated symptoms of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) can significantly interfere with school and social functioning [1]. Children with ADHD often have comorbid conditions such as anxiety, low self-esteem and learning disabilities. It is vital to screen and treat for ADHD and comorbidities early and comprehensively [2].

There are disproportionately higher rates of children diagnosed with ADHD living in underserved areas compared to other geographical regions [3]. The historically underserved Southeast region of Washington D.C. which encompasses Wards 7 and 8 is home to nearly 40% of the district’s children and has the highest rates of children with an ADHD diagnosis in D.C.; however, the majority of child psychiatrists are located in the Northwest regions [4]. In 2009, nearly 8% of children in Washington D.C. were reported to have a diagnosis of ADHD [1].

Due to the overwhelming demand and limited availability of child psychiatrists, it is important that primary care providers become better equipped to diagnose, treat, and manage non-complex cases of ADHD. Specific education about ADHD diagnosis and management along with implementation of standardized center-based processes may help primary care providers feel more comfortable caring for these patients and ensure that all patients presenting with behavior concerns are adequately assessed and treated.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that primary care providers expand their mental health competencies because pediatric primary care providers in the medical home will be the first point of access in most cases [5]. In 2011, the AAP Subcommittee on ADHD and Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management released clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of ADHD [6]. These guidelines, which recommend that providers should initiate ADHD assessments for children ages 6 to 12 that present with behavioral and/or academic problems, have been incorporated into “Caring for Children with ADHD: A Resource Toolkit for Clinicians” by the AAP in partnership with the National Institute on Children’s Health Quality (NICHQ) and North Carolina’s Center for Child Health.

Our clinic has two on-site psychiatrists who provide evaluation and treatment of mental health problems in children identified by primary care providers for a combined total of 1.5 days each week. The current wait for psychiatric evaluation at our clinic is 2 to 3 months, which leaves the primary care providers to care for many children with behavior concerns who require more immediate intervention at the time of their presentation. Our clinic providers revealed that they felt there were deficits in the management of behavior concerns and initiating treatment for patients diagnosed with ADHD in the clinic. Providers expressed an interest in refreshing and enhancing their knowledge related to managing patients with ADHD.

To address this issue, we initiated a quality improvement project with several facets: provide ADHD education to primary care providers through use of educational sessions from our on-site psychiatrists, standardize the process of managing patients that present with behavior concerns to the primary care provider in the medical home, and develop a comprehensive and individualized patient management plan based on the “Caring for Children with ADHD” toolkit for clinicians.

Methods

Setting

This project took place in a federally qualified health center located in the Southeast quadrant of Washington, D.C. that serves patients up to 23 years of age. The clinic has 6 primary care medical providers (5 physicians and 1 nurse practitioner) employed in a part-time to full-time capacity. Additionally, 2 child psychiatrists provide services on-site during one full day and one half-day session on a weekly basis. Approximately 98% of patients at the clinic are classified as African American and close to 95% of patients are insured by Medicaid. Approximately 9% of patients in our clinic had a medical diagnosis of ADHD as of 2015.

Patients who presented to the clinic in April and May 2017 who had an existing diagnosis of ADHD and those with documentation of a new behavior concern in the assessment and treatment plan were studied. Eligible visit types were annual well-child checks, new consults for behavior, and follow-up appointments specifically for behavior.

This was a project undertaken as a quality improvement initiative at the hosting facility and did not constitute human subjects research. As such, it was not under the oversight of the institutional review board.

Intervention

Provider Education. Three in-person sessions were held at the clinic during April–May 2017 to provide education on the assessment and treatment of patients with ADHD and discuss challenges that have arisen when providing care for such patients. The sessions focused on diagnosing ADHD and teasing out comorbidities; initiating and titrating medications safely; educational rights; and strategies for managing behavior and community resources.

Current providers as well as medical residents and student trainees of the clinic were invited to attend the educational sessions. Each session followed a “lunch and learn” format where one of the clinic psychiatrists presented the information during the clinic lunch hour then related a discussion where participants asked questions. The information provided was derived from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5) and the AAP/NICHQ Toolkit [5]. Educational handouts were disseminated during the provider sessions and emailed to all providers afterwards.

Behavior Management Plan. In March we introduced the providers to the Behavior Management Plan (Figure),

Providers were encouraged to initiate the Behavior Management Plan for patients that presented without an existing diagnosis for evaluation of their behavior concerns. The plan could also be used for patients that had previously been diagnosed with ADHD if changes were being made to their treatment plan or as a summary of their established treatment details. Instructions on the use of the plan were given to all clinic primary care providers through email communication as well as in the first in-person educational session. It was stressed to providers that formulating individual patient goals and the inclusion of a specific follow-up time were the most important aspects of the plan.

Assessment and Measurements

We assessed provider comfort in their ADHD evaluation and management skills before and after the intervention using a 5–point Likert scale questionnaire with 0 indicating “not comfortable at all” and 5 corresponding to “very comfortable.” The questionnaire was administered via a paper survey for the initial screening and an electronic survey at the conclusion of the intervention.

Patient charts were reviewed in July 2017 to determine how often the Behavior Management Plan was utilized. Provider documentation in the electronic medical record indicating that the Plan was given during the patient visit was considered utilization of the plan. We also examined documentation of dissemination/return of Vanderbilt ADHD assessment scales, referrals to psychiatry or counseling, and the initiation or refill of an ADHD medication during the encounter for all patients that were seen for behavior concerns. Patient data were obtained from manual chart review of the electronic medical record, eClinicalWorks.

Analysis

SPSS Statistics (Version 24) was used to conduct analyses. Independent sample t tests were employed to measure items related to the provider educational sessions. Mean provider responses for each item were reviewed from descriptive statistics. A chi-square cross tabulation was used to compare the percentage of patients receiving a Behavior Management Plan that adhered to follow-up visits versus a similar sample of patients that presented in 2016 before the introduction of the Behavior Management Plan. In addition, a chi-square cross tabulation was utilized to compare adherence to follow-up visits in those that received the Management Plan to that of eligible patients that presented during the same time period but did not receive the Plan. Additional chi-square tests were run to see if there was any difference in 2017 follow-up rates based on individual provider or visit type .

Results

Provider Questionnaire

Six providers responded to the pre-intervention questionnaire and five to the post-intervention questionnaire. The specific questions and their results are listed in Table 1.

Patient Management

Between April and May 2017, 61 eligible patients presented to the clinic. Details of the breakdown of patient visit type are displayed in Table 2.

Follow-up Rates

Notation of a specific time frame for follow-up by a primary care provider was found in 24 of 61 (39%) relevant patient charts (Table 3).

Further cross-tabulations were completed to assess if there were better follow-up rates for patients that received a Behavior Management Plan. The difference between the 2 groups was not significant (P = 0.99). There were no significant differences found in follow-up rates based on the provider for the visit (P = 0.51) or the type of patient visit (well child examination vs. behavior consult) (P = 0.65).

Discussion

This project aimed to improve provider confidence in the assessment and treatment of ADHD and improve ADHD management by providers at our clinic. We did not find significant changes in confidence according to the survey results. However, provider feedback indicated that, as a result of the educational sessions, they had a deeper appreciation for the presence of psychiatric comorbidities and the role they play in deciding appropriate treatment. They also reported that they more fully understood the need to refer to child psychiatry for evaluation and management when comorbidities are present instead of attempting to independently provide ADHD medication.

We hoped to see the Behavior Management Plan used for patients with new behavior concerns during the evaluation for ADHD. During the intervention period, it was used in half of eligible clinic visits of patients without a prior diagnosis of ADHD. Future investigation should be directed at receiving specific input on the utility of the Behavior Management Plan from providers and families. The Management Plan contains important reminders and treatment information; however, if the plan is not perceived as effective or useful, taking the time needed to complete it may be seen as an additional cumbersome step in the already overloaded clinic visits.

The use of the Behavior Management Plan was not found to make a statistically significant difference in follow-up rates. Attendance at follow-up appointments for ADHD patients is not an area that has been greatly studied. In a recent analysis of ADHD treatment quality in Medicaid-enrolled children, African American families were less likely to have adequate follow-up compared to Caucasian counterparts during the initiation or continuation and management phases of treatment. The review of specific follow-through rates showed that African Americans were 22% more likely to discontinue medication therapy and 13% more likely to disengage from treatment. The authors propose that future efforts focus on improving accessibility of behavioral therapy to combat the discontinuation rates and disparities in this area [8]. Another study that looked at a prospective cohort of ADHD patients found suboptimal attendance at appointments with a median of 1 visit every 6 months [9]. Further exploration of the challenges with attendance at follow-up appointments is warranted to help determine best practices for ADHD management in disadvantaged communities. More information is needed on the specific barriers to care in this subgroup at our clinic. However, data from this project related to adherence to follow-up appointments can be used to guide future studies.

Use of a Behavior Management Plan was not found to influence the return of completed teacher Vanderbilt scales by families. The rates of return of these assessment forms continue to be very low. Without input from teachers and schools, it is difficult to properly diagnose, treat and evaluate the treatment of patients. Feedback from all sources is essential for both medication management and construction of interventions for behavioral challenges at school. The development of partnerships with a child’s school may be useful in helping patients return for the treatment of behavior concerns at their initial stages. Before children are expelled multiple times due to their behavior, schools should strongly encourage parents to notify their healthcare provider of behavior concerns for evaluation.

In an ideal system, school-based nurses, guidance counselors or social workers could provide some case management and outreach to families of children with known behavior concerns to ensure they are attending appointments as recommended by their treatment plan and explore barriers to doing so. Social workers can provide direct mental health care services and make referrals to community agencies. However, the caseload for school-based providers is currently quite high and many children slip through the cracks until their behavior escalates to a dangerous and/or very disruptive level. School-based personnel in several districts are now required to split their time in multiple schools. Dang et al describe the piloting of a school-based framework for early identification and assessment of children suspected to have ADHD. The framework, called ADHD Identification and Management in Schools (AIMS), encourages school nurses to gather all parent and teacher assessment materials prior to the initial visit to their primary care providers thus reducing the number of visits needed and leading to faster diagnosis and treatment [10].

Clinic-based case managers solely dedicated to this population would also be useful. These case managers could provide management as described above and also potentially sit-in on clinic visits for behavior concerns so that they are fully aware of the instructions given by the provider. This would also give them the information needed so that they are able to complete forms such as the Behavior Management Plan, which would be helpful in relieving some provider time. Geltman et al trialed a workflow intervention with electronic Vanderbilt scales and an electronic registry managed by a care coordination team of a physician, nurse and medical assistant. This allowed patient calls to the families by the nurse or medical assistant to remind them of necessary follow-up and monthly meetings with the care coordination team. Those in the intervention group with the care coordination team were twice as likely to return the Vanderbilt questionnaires. During the intervention period, the rates of follow-up visits remained the same; however, when the intervention was further adopted and expanded to other sites, follow-up attendance improved to over 90% [11].

Limitations

Limitations of this project include the short time period in which it was conducted as well as the size of the study sample. Provider work schedules also caused some challenges with arranging the lunch and learn educational sessions and completing independent review of materials on the subject. This project focused on a primarily African American, predominately Medicaid population. Within urban and/or underserved populations, there may be other demographic distributions thus limiting the generalizability of these findings.

Summary

In summary, this project attempted to improve provider confidence in management of ADHD and standardize assessment practices of one urban pediatric clinic. At the project’s conclusion there were subjective improvements in provider confidence. Ongoing opportunities for continuing education on management of mental health diagnoses for primary care providers should persevere. This project also highlights the persistent problem of patient follow-up for behavior concerns. Further exploration of challenges with attendance at follow-up appointments including collaboration with community and academic resources is needed to help determine best practices for ADHD management in disadvantaged communities.

Corresponding author: Jaytoya C. Manget, DNP, MSPH, FNP, jmanget@childrensnational.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Children’s National Health System, Washington, DC (Dr. Manget, Dr. Kelley, Dr. White) and the Duke University School of Nursing, Durham, NC (Dr. Blood-Siegfried).

Abstract

- Background: Approximately 11% of children in the United States ages 4 to 17 have received the diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD). There are disproportionately higher rates of the diagnosis and fewer child psychiatrists available in underserved areas. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) strongly encourages improved mental health competencies among primary care providers to combat this shortage.

- Objective: To improve primary care providers’ knowledge and confidence with the management of ADHD and institute an evidence-based process for assessing patients presenting with behavior concerns suggestive of ADHD.

- Methods: Three in-person educational sessions were conducted for primary care providers by a child psychiatrist to increase providers’ knowledge and confidence in the evaluation and management of ADHD. A Behavior Management Plan was also adopted for use in the clinic. Providers were encouraged to use the plan during patient visits for behavior concerns indicative of ADHD. Pre- and post-test surveys were given to providers to assess change in comfort level with managing ADHD. Patient charts were reviewed to determine how often the Behavior Management Plan was utilized.

- Results: We did not find significant changes in provider comfort in managing ADHD according to the survey results, although providers reported that the educational sessions and handouts were useful. Behavior Management Plans were utilized during 13 of 25 (52%) eligible visits.

- Conclusions: Behavior Management Plans were introduced in just over half of relevant visits. Further exploration about barriers to use of the plan and its utility to patients and families should be pursued in the future. Additionally, ongoing opportunities for continuing education and collaboration with psychiatry should continue to be sought.

Keywords: attention-deficit hyperactive disorder; ADHD; AAP clinical guidelines; underserved populations; disadvantaged communities.

The importance of the mental health of a child cannot be underestimated. Untreated symptoms of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) can significantly interfere with school and social functioning [1]. Children with ADHD often have comorbid conditions such as anxiety, low self-esteem and learning disabilities. It is vital to screen and treat for ADHD and comorbidities early and comprehensively [2].

There are disproportionately higher rates of children diagnosed with ADHD living in underserved areas compared to other geographical regions [3]. The historically underserved Southeast region of Washington D.C. which encompasses Wards 7 and 8 is home to nearly 40% of the district’s children and has the highest rates of children with an ADHD diagnosis in D.C.; however, the majority of child psychiatrists are located in the Northwest regions [4]. In 2009, nearly 8% of children in Washington D.C. were reported to have a diagnosis of ADHD [1].

Due to the overwhelming demand and limited availability of child psychiatrists, it is important that primary care providers become better equipped to diagnose, treat, and manage non-complex cases of ADHD. Specific education about ADHD diagnosis and management along with implementation of standardized center-based processes may help primary care providers feel more comfortable caring for these patients and ensure that all patients presenting with behavior concerns are adequately assessed and treated.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that primary care providers expand their mental health competencies because pediatric primary care providers in the medical home will be the first point of access in most cases [5]. In 2011, the AAP Subcommittee on ADHD and Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management released clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of ADHD [6]. These guidelines, which recommend that providers should initiate ADHD assessments for children ages 6 to 12 that present with behavioral and/or academic problems, have been incorporated into “Caring for Children with ADHD: A Resource Toolkit for Clinicians” by the AAP in partnership with the National Institute on Children’s Health Quality (NICHQ) and North Carolina’s Center for Child Health.

Our clinic has two on-site psychiatrists who provide evaluation and treatment of mental health problems in children identified by primary care providers for a combined total of 1.5 days each week. The current wait for psychiatric evaluation at our clinic is 2 to 3 months, which leaves the primary care providers to care for many children with behavior concerns who require more immediate intervention at the time of their presentation. Our clinic providers revealed that they felt there were deficits in the management of behavior concerns and initiating treatment for patients diagnosed with ADHD in the clinic. Providers expressed an interest in refreshing and enhancing their knowledge related to managing patients with ADHD.

To address this issue, we initiated a quality improvement project with several facets: provide ADHD education to primary care providers through use of educational sessions from our on-site psychiatrists, standardize the process of managing patients that present with behavior concerns to the primary care provider in the medical home, and develop a comprehensive and individualized patient management plan based on the “Caring for Children with ADHD” toolkit for clinicians.

Methods

Setting

This project took place in a federally qualified health center located in the Southeast quadrant of Washington, D.C. that serves patients up to 23 years of age. The clinic has 6 primary care medical providers (5 physicians and 1 nurse practitioner) employed in a part-time to full-time capacity. Additionally, 2 child psychiatrists provide services on-site during one full day and one half-day session on a weekly basis. Approximately 98% of patients at the clinic are classified as African American and close to 95% of patients are insured by Medicaid. Approximately 9% of patients in our clinic had a medical diagnosis of ADHD as of 2015.

Patients who presented to the clinic in April and May 2017 who had an existing diagnosis of ADHD and those with documentation of a new behavior concern in the assessment and treatment plan were studied. Eligible visit types were annual well-child checks, new consults for behavior, and follow-up appointments specifically for behavior.

This was a project undertaken as a quality improvement initiative at the hosting facility and did not constitute human subjects research. As such, it was not under the oversight of the institutional review board.

Intervention

Provider Education. Three in-person sessions were held at the clinic during April–May 2017 to provide education on the assessment and treatment of patients with ADHD and discuss challenges that have arisen when providing care for such patients. The sessions focused on diagnosing ADHD and teasing out comorbidities; initiating and titrating medications safely; educational rights; and strategies for managing behavior and community resources.

Current providers as well as medical residents and student trainees of the clinic were invited to attend the educational sessions. Each session followed a “lunch and learn” format where one of the clinic psychiatrists presented the information during the clinic lunch hour then related a discussion where participants asked questions. The information provided was derived from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5) and the AAP/NICHQ Toolkit [5]. Educational handouts were disseminated during the provider sessions and emailed to all providers afterwards.

Behavior Management Plan. In March we introduced the providers to the Behavior Management Plan (Figure),

Providers were encouraged to initiate the Behavior Management Plan for patients that presented without an existing diagnosis for evaluation of their behavior concerns. The plan could also be used for patients that had previously been diagnosed with ADHD if changes were being made to their treatment plan or as a summary of their established treatment details. Instructions on the use of the plan were given to all clinic primary care providers through email communication as well as in the first in-person educational session. It was stressed to providers that formulating individual patient goals and the inclusion of a specific follow-up time were the most important aspects of the plan.

Assessment and Measurements

We assessed provider comfort in their ADHD evaluation and management skills before and after the intervention using a 5–point Likert scale questionnaire with 0 indicating “not comfortable at all” and 5 corresponding to “very comfortable.” The questionnaire was administered via a paper survey for the initial screening and an electronic survey at the conclusion of the intervention.

Patient charts were reviewed in July 2017 to determine how often the Behavior Management Plan was utilized. Provider documentation in the electronic medical record indicating that the Plan was given during the patient visit was considered utilization of the plan. We also examined documentation of dissemination/return of Vanderbilt ADHD assessment scales, referrals to psychiatry or counseling, and the initiation or refill of an ADHD medication during the encounter for all patients that were seen for behavior concerns. Patient data were obtained from manual chart review of the electronic medical record, eClinicalWorks.

Analysis

SPSS Statistics (Version 24) was used to conduct analyses. Independent sample t tests were employed to measure items related to the provider educational sessions. Mean provider responses for each item were reviewed from descriptive statistics. A chi-square cross tabulation was used to compare the percentage of patients receiving a Behavior Management Plan that adhered to follow-up visits versus a similar sample of patients that presented in 2016 before the introduction of the Behavior Management Plan. In addition, a chi-square cross tabulation was utilized to compare adherence to follow-up visits in those that received the Management Plan to that of eligible patients that presented during the same time period but did not receive the Plan. Additional chi-square tests were run to see if there was any difference in 2017 follow-up rates based on individual provider or visit type .

Results

Provider Questionnaire

Six providers responded to the pre-intervention questionnaire and five to the post-intervention questionnaire. The specific questions and their results are listed in Table 1.

Patient Management

Between April and May 2017, 61 eligible patients presented to the clinic. Details of the breakdown of patient visit type are displayed in Table 2.

Follow-up Rates

Notation of a specific time frame for follow-up by a primary care provider was found in 24 of 61 (39%) relevant patient charts (Table 3).

Further cross-tabulations were completed to assess if there were better follow-up rates for patients that received a Behavior Management Plan. The difference between the 2 groups was not significant (P = 0.99). There were no significant differences found in follow-up rates based on the provider for the visit (P = 0.51) or the type of patient visit (well child examination vs. behavior consult) (P = 0.65).

Discussion

This project aimed to improve provider confidence in the assessment and treatment of ADHD and improve ADHD management by providers at our clinic. We did not find significant changes in confidence according to the survey results. However, provider feedback indicated that, as a result of the educational sessions, they had a deeper appreciation for the presence of psychiatric comorbidities and the role they play in deciding appropriate treatment. They also reported that they more fully understood the need to refer to child psychiatry for evaluation and management when comorbidities are present instead of attempting to independently provide ADHD medication.

We hoped to see the Behavior Management Plan used for patients with new behavior concerns during the evaluation for ADHD. During the intervention period, it was used in half of eligible clinic visits of patients without a prior diagnosis of ADHD. Future investigation should be directed at receiving specific input on the utility of the Behavior Management Plan from providers and families. The Management Plan contains important reminders and treatment information; however, if the plan is not perceived as effective or useful, taking the time needed to complete it may be seen as an additional cumbersome step in the already overloaded clinic visits.

The use of the Behavior Management Plan was not found to make a statistically significant difference in follow-up rates. Attendance at follow-up appointments for ADHD patients is not an area that has been greatly studied. In a recent analysis of ADHD treatment quality in Medicaid-enrolled children, African American families were less likely to have adequate follow-up compared to Caucasian counterparts during the initiation or continuation and management phases of treatment. The review of specific follow-through rates showed that African Americans were 22% more likely to discontinue medication therapy and 13% more likely to disengage from treatment. The authors propose that future efforts focus on improving accessibility of behavioral therapy to combat the discontinuation rates and disparities in this area [8]. Another study that looked at a prospective cohort of ADHD patients found suboptimal attendance at appointments with a median of 1 visit every 6 months [9]. Further exploration of the challenges with attendance at follow-up appointments is warranted to help determine best practices for ADHD management in disadvantaged communities. More information is needed on the specific barriers to care in this subgroup at our clinic. However, data from this project related to adherence to follow-up appointments can be used to guide future studies.

Use of a Behavior Management Plan was not found to influence the return of completed teacher Vanderbilt scales by families. The rates of return of these assessment forms continue to be very low. Without input from teachers and schools, it is difficult to properly diagnose, treat and evaluate the treatment of patients. Feedback from all sources is essential for both medication management and construction of interventions for behavioral challenges at school. The development of partnerships with a child’s school may be useful in helping patients return for the treatment of behavior concerns at their initial stages. Before children are expelled multiple times due to their behavior, schools should strongly encourage parents to notify their healthcare provider of behavior concerns for evaluation.

In an ideal system, school-based nurses, guidance counselors or social workers could provide some case management and outreach to families of children with known behavior concerns to ensure they are attending appointments as recommended by their treatment plan and explore barriers to doing so. Social workers can provide direct mental health care services and make referrals to community agencies. However, the caseload for school-based providers is currently quite high and many children slip through the cracks until their behavior escalates to a dangerous and/or very disruptive level. School-based personnel in several districts are now required to split their time in multiple schools. Dang et al describe the piloting of a school-based framework for early identification and assessment of children suspected to have ADHD. The framework, called ADHD Identification and Management in Schools (AIMS), encourages school nurses to gather all parent and teacher assessment materials prior to the initial visit to their primary care providers thus reducing the number of visits needed and leading to faster diagnosis and treatment [10].

Clinic-based case managers solely dedicated to this population would also be useful. These case managers could provide management as described above and also potentially sit-in on clinic visits for behavior concerns so that they are fully aware of the instructions given by the provider. This would also give them the information needed so that they are able to complete forms such as the Behavior Management Plan, which would be helpful in relieving some provider time. Geltman et al trialed a workflow intervention with electronic Vanderbilt scales and an electronic registry managed by a care coordination team of a physician, nurse and medical assistant. This allowed patient calls to the families by the nurse or medical assistant to remind them of necessary follow-up and monthly meetings with the care coordination team. Those in the intervention group with the care coordination team were twice as likely to return the Vanderbilt questionnaires. During the intervention period, the rates of follow-up visits remained the same; however, when the intervention was further adopted and expanded to other sites, follow-up attendance improved to over 90% [11].

Limitations

Limitations of this project include the short time period in which it was conducted as well as the size of the study sample. Provider work schedules also caused some challenges with arranging the lunch and learn educational sessions and completing independent review of materials on the subject. This project focused on a primarily African American, predominately Medicaid population. Within urban and/or underserved populations, there may be other demographic distributions thus limiting the generalizability of these findings.

Summary

In summary, this project attempted to improve provider confidence in management of ADHD and standardize assessment practices of one urban pediatric clinic. At the project’s conclusion there were subjective improvements in provider confidence. Ongoing opportunities for continuing education on management of mental health diagnoses for primary care providers should persevere. This project also highlights the persistent problem of patient follow-up for behavior concerns. Further exploration of challenges with attendance at follow-up appointments including collaboration with community and academic resources is needed to help determine best practices for ADHD management in disadvantaged communities.

Corresponding author: Jaytoya C. Manget, DNP, MSPH, FNP, jmanget@childrensnational.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Visser SN, Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, et al. Trends in the parent-report of health care provider-diagnosed and medicated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: United States, 2003-2011. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry 2014;53:34–46.

2. Charach A, Dashti B, Carson P, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effectiveness of treatment in at-risk preschoolers; long-term effectiveness in all ages; and variability in prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011.

3. John M. Eisenberg Center for Clinical Decisions and Communications Science. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. 2012 Jun 26. Comparative Effectiveness Review Summary Guides for Clinicians [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007-2012.

4. Wotring JR, O’Grady KA, Anthony BJ, et al. Behavioral health for children, youth and families in the District of Columbia: A review of prevalence, service utilization, barriers, and recommendations. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development, National Technical Assistance Center for Children’s Mental Health; 2014.

5. American Academy of Pediatrics. Caring for children with ADHD: a resource toolkit for clinicians. [CD-ROM] Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2011.

6. American Academy of Pediatrics, Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactive Disorder, Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management. ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2011;128:1007–22.

7. American Academy of Pediatrics and National Institute for Children’s Healthcare Quality. NICQH Vanderbilt Assessment Scales: Used for diagnosing ADHD. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2002.

8. Cummings JR, Ji X, Allen L, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in ADHD treatment quality among Medicaid-enrolled youth. Pediatrics 2017;139(6).

9. Gardner W, Kelleher KJ, Pajer K, Campo, JV. Follow-up care of children identified with ADHD by primary care clinicians: A prospective cohort study. J Pediatrics 2004;145:767–71.

10. Dang MT, Warrington D, Tung T, et al. A school-based approach to early identification and management of students with ADHD. J Sch Nurs 2007:2–12.

11. Geltman PL, Fried LE, Arsenault LN, et al. A planned care approach and patient registry to improve adherence to clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Acad Pediatrics 2015;15:289–96.

1. Visser SN, Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, et al. Trends in the parent-report of health care provider-diagnosed and medicated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: United States, 2003-2011. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry 2014;53:34–46.

2. Charach A, Dashti B, Carson P, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effectiveness of treatment in at-risk preschoolers; long-term effectiveness in all ages; and variability in prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011.

3. John M. Eisenberg Center for Clinical Decisions and Communications Science. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. 2012 Jun 26. Comparative Effectiveness Review Summary Guides for Clinicians [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007-2012.

4. Wotring JR, O’Grady KA, Anthony BJ, et al. Behavioral health for children, youth and families in the District of Columbia: A review of prevalence, service utilization, barriers, and recommendations. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development, National Technical Assistance Center for Children’s Mental Health; 2014.

5. American Academy of Pediatrics. Caring for children with ADHD: a resource toolkit for clinicians. [CD-ROM] Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2011.

6. American Academy of Pediatrics, Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactive Disorder, Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management. ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2011;128:1007–22.

7. American Academy of Pediatrics and National Institute for Children’s Healthcare Quality. NICQH Vanderbilt Assessment Scales: Used for diagnosing ADHD. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2002.

8. Cummings JR, Ji X, Allen L, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in ADHD treatment quality among Medicaid-enrolled youth. Pediatrics 2017;139(6).

9. Gardner W, Kelleher KJ, Pajer K, Campo, JV. Follow-up care of children identified with ADHD by primary care clinicians: A prospective cohort study. J Pediatrics 2004;145:767–71.

10. Dang MT, Warrington D, Tung T, et al. A school-based approach to early identification and management of students with ADHD. J Sch Nurs 2007:2–12.

11. Geltman PL, Fried LE, Arsenault LN, et al. A planned care approach and patient registry to improve adherence to clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Acad Pediatrics 2015;15:289–96.