User login

Integrated Outpatient Palliative Care for Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Background: Despite increasing emphasis on integration of palliative care with disease-directed care for advanced cancer, the nature of this integration and its effects on patient and caregiver outcomes are not well understood.

Methods: We evaluated the effects of integrated outpatient palliative and oncology care for advanced cancer on patient and caregiver outcomes. Following a standard protocol (PROSPERO: CRD42017057541), investigators independently screened reports to identify randomized controlled trials or quasi-experimental studies that evaluated the effect of integrated outpatient palliative and oncology care interventions on quality of life, survival, and healthcare utilization among adults with advanced cancer. Data sources were English-language peer-reviewed publications in PubMed, CINAHL, and Cochrane Central through November 2016. We subsequently updated our PubMed search through July 2018. Data were synthesized using random-effects meta-analyses, supplemented with qualitative methods when necessary.

Results: Eight randomized controlled and two cluster randomized trials were included. Most patients had multiple advanced cancers, with median time from diagnosis or recurrence to enrollment ranging from eight to 12 weeks. All interventions included a multidisciplinary team, were classified as “moderately integrated,” and addressed physical and psychological symptoms. In a meta-analysis, short-term quality of life improved; symptom burden improved; and all-cause mortality decreased. Qualitative analyses revealed no association between integration elements, palliative care intervention elements, and intervention impact. Utilization and caregiver outcomes were often not reported.

Conclusion: Moderately integrated palliative and oncology outpatient interventions had positive effects on short-term quality of life, symptom burden, and survival. Evidence for effects on healthcare utilization and caregiver outcomes remains sparse.

Background: Despite increasing emphasis on integration of palliative care with disease-directed care for advanced cancer, the nature of this integration and its effects on patient and caregiver outcomes are not well understood.

Methods: We evaluated the effects of integrated outpatient palliative and oncology care for advanced cancer on patient and caregiver outcomes. Following a standard protocol (PROSPERO: CRD42017057541), investigators independently screened reports to identify randomized controlled trials or quasi-experimental studies that evaluated the effect of integrated outpatient palliative and oncology care interventions on quality of life, survival, and healthcare utilization among adults with advanced cancer. Data sources were English-language peer-reviewed publications in PubMed, CINAHL, and Cochrane Central through November 2016. We subsequently updated our PubMed search through July 2018. Data were synthesized using random-effects meta-analyses, supplemented with qualitative methods when necessary.

Results: Eight randomized controlled and two cluster randomized trials were included. Most patients had multiple advanced cancers, with median time from diagnosis or recurrence to enrollment ranging from eight to 12 weeks. All interventions included a multidisciplinary team, were classified as “moderately integrated,” and addressed physical and psychological symptoms. In a meta-analysis, short-term quality of life improved; symptom burden improved; and all-cause mortality decreased. Qualitative analyses revealed no association between integration elements, palliative care intervention elements, and intervention impact. Utilization and caregiver outcomes were often not reported.

Conclusion: Moderately integrated palliative and oncology outpatient interventions had positive effects on short-term quality of life, symptom burden, and survival. Evidence for effects on healthcare utilization and caregiver outcomes remains sparse.

Background: Despite increasing emphasis on integration of palliative care with disease-directed care for advanced cancer, the nature of this integration and its effects on patient and caregiver outcomes are not well understood.

Methods: We evaluated the effects of integrated outpatient palliative and oncology care for advanced cancer on patient and caregiver outcomes. Following a standard protocol (PROSPERO: CRD42017057541), investigators independently screened reports to identify randomized controlled trials or quasi-experimental studies that evaluated the effect of integrated outpatient palliative and oncology care interventions on quality of life, survival, and healthcare utilization among adults with advanced cancer. Data sources were English-language peer-reviewed publications in PubMed, CINAHL, and Cochrane Central through November 2016. We subsequently updated our PubMed search through July 2018. Data were synthesized using random-effects meta-analyses, supplemented with qualitative methods when necessary.

Results: Eight randomized controlled and two cluster randomized trials were included. Most patients had multiple advanced cancers, with median time from diagnosis or recurrence to enrollment ranging from eight to 12 weeks. All interventions included a multidisciplinary team, were classified as “moderately integrated,” and addressed physical and psychological symptoms. In a meta-analysis, short-term quality of life improved; symptom burden improved; and all-cause mortality decreased. Qualitative analyses revealed no association between integration elements, palliative care intervention elements, and intervention impact. Utilization and caregiver outcomes were often not reported.

Conclusion: Moderately integrated palliative and oncology outpatient interventions had positive effects on short-term quality of life, symptom burden, and survival. Evidence for effects on healthcare utilization and caregiver outcomes remains sparse.

Optimization of Palliative Oncology Care Within the VA Healthcare System–Assessing the Availability of Outpatient Palliative Care Within VA Oncology Clinic

Purpose: Palliative care is essential to oncology. The purpose of this project was to characterize the interface between VA oncologists and palliative care specialists in the outpatient setting and to identify barriers to outpatient palliative oncology care in the VA.

Background: The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommends palliative care for all patients with metastatic lung cancer and other symptomatic advanced malignancies. The VA mandates palliative care inpatient consult teams for all medical facilities. It is not clearly known how palliative care is integrated into standard VA outpatient oncology practice. The 2016 VHA Cancer Care Survey was a comprehensive assessment of 140 VA facilities regarding their cancer care infrastructure. On this survey, 23% of sites (N=32) reported that they were not able to provide adequate palliative oncology care in the outpatient setting.

Methods: We contacted clinicians at each of these 32 sites to characterize the outpatient oncology/palliative care interface and identify potential barriers.

Results: Of the 32 sites, 17 reported that they provided limited oncologic care and generally referred patients to other facilities for cancer treatment. The remaining 15 sites reported providing full oncology services. These 15 sites employed a variety of methods to engage palliative care specialists. These included referring patients to a separate outpatient palliative care clinic or a home-based provider; consulting the inpatient palliative care team to evaluate the patient while in the cancer clinic; working with an oncology social worker; or arranging a tele-consult with a remote palliative care specialist. Barriers to providing outpatient palliative care included not enough palliative care staff, not enough clinic space, and patients or oncologists declining a palliative care referral. Clinicians expressed that they would provide more outpatient palliative care if they

had more palliative care staff, more clinic space, and more palliative care training for oncologists.

Conclusions: This project identified that some sites have found creative approaches to providing outpatient palliative oncology care. In addition, clinicians emphasized the ongoing need for additional specialty palliative care staff, primary palliative care training for oncologists, and clinic space in order to provide optimal outpatient palliative oncology care for VA patients.

Purpose: Palliative care is essential to oncology. The purpose of this project was to characterize the interface between VA oncologists and palliative care specialists in the outpatient setting and to identify barriers to outpatient palliative oncology care in the VA.

Background: The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommends palliative care for all patients with metastatic lung cancer and other symptomatic advanced malignancies. The VA mandates palliative care inpatient consult teams for all medical facilities. It is not clearly known how palliative care is integrated into standard VA outpatient oncology practice. The 2016 VHA Cancer Care Survey was a comprehensive assessment of 140 VA facilities regarding their cancer care infrastructure. On this survey, 23% of sites (N=32) reported that they were not able to provide adequate palliative oncology care in the outpatient setting.

Methods: We contacted clinicians at each of these 32 sites to characterize the outpatient oncology/palliative care interface and identify potential barriers.

Results: Of the 32 sites, 17 reported that they provided limited oncologic care and generally referred patients to other facilities for cancer treatment. The remaining 15 sites reported providing full oncology services. These 15 sites employed a variety of methods to engage palliative care specialists. These included referring patients to a separate outpatient palliative care clinic or a home-based provider; consulting the inpatient palliative care team to evaluate the patient while in the cancer clinic; working with an oncology social worker; or arranging a tele-consult with a remote palliative care specialist. Barriers to providing outpatient palliative care included not enough palliative care staff, not enough clinic space, and patients or oncologists declining a palliative care referral. Clinicians expressed that they would provide more outpatient palliative care if they

had more palliative care staff, more clinic space, and more palliative care training for oncologists.

Conclusions: This project identified that some sites have found creative approaches to providing outpatient palliative oncology care. In addition, clinicians emphasized the ongoing need for additional specialty palliative care staff, primary palliative care training for oncologists, and clinic space in order to provide optimal outpatient palliative oncology care for VA patients.

Purpose: Palliative care is essential to oncology. The purpose of this project was to characterize the interface between VA oncologists and palliative care specialists in the outpatient setting and to identify barriers to outpatient palliative oncology care in the VA.

Background: The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommends palliative care for all patients with metastatic lung cancer and other symptomatic advanced malignancies. The VA mandates palliative care inpatient consult teams for all medical facilities. It is not clearly known how palliative care is integrated into standard VA outpatient oncology practice. The 2016 VHA Cancer Care Survey was a comprehensive assessment of 140 VA facilities regarding their cancer care infrastructure. On this survey, 23% of sites (N=32) reported that they were not able to provide adequate palliative oncology care in the outpatient setting.

Methods: We contacted clinicians at each of these 32 sites to characterize the outpatient oncology/palliative care interface and identify potential barriers.

Results: Of the 32 sites, 17 reported that they provided limited oncologic care and generally referred patients to other facilities for cancer treatment. The remaining 15 sites reported providing full oncology services. These 15 sites employed a variety of methods to engage palliative care specialists. These included referring patients to a separate outpatient palliative care clinic or a home-based provider; consulting the inpatient palliative care team to evaluate the patient while in the cancer clinic; working with an oncology social worker; or arranging a tele-consult with a remote palliative care specialist. Barriers to providing outpatient palliative care included not enough palliative care staff, not enough clinic space, and patients or oncologists declining a palliative care referral. Clinicians expressed that they would provide more outpatient palliative care if they

had more palliative care staff, more clinic space, and more palliative care training for oncologists.

Conclusions: This project identified that some sites have found creative approaches to providing outpatient palliative oncology care. In addition, clinicians emphasized the ongoing need for additional specialty palliative care staff, primary palliative care training for oncologists, and clinic space in order to provide optimal outpatient palliative oncology care for VA patients.

Model of Integrated Oncology- Palliative Care in an Outpatient Setting

Background: Early introduction of palliative care for oncology patients has demonstrated enhanced quality of life and satisfaction. We developed a model for integrating palliative care into outpatient oncology care.

Hypothesis: Optimal integration of oncology and palliative care requires palliative care clinician’s presence at initial, and many subsequent, patient encounters.

Objective: To implement and evaluate outpatient integrated oncology and palliative care.

Method: In January 2015, we implemented an integrated outpatient practice of oncology and palliative care with: Pre-clinic “huddle” among palliative care and oncology staff to identify patients in need of palliative care; shared palliative care-oncology appointments. Initial visit: New oncology patients are seen by an oncologist and palliative care physician together. Palliative care physician introduces palliative care and initiates advance care planning. Concurrent oncology-palliative care follow-up: High-risk patients (aggressive histology, progressing disease, etc) are followed by oncologist and palliative care physician. Palliative care physician facilitates goals of care discussions and addresses symptom management. End-of-life care: Hospice care remains a part of oncology care. Palliative care physician and oncology team co-manage all oncology patients enrolled in hospice care.

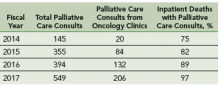

Results: Increase in palliative care consults from oncology clinics: After this intervention, there is a 10-fold increase in number of palliative care consultation requests from oncology clinics from fiscal year 2014 to 2017. Increase in percentage of inpatients deaths with prior palliative care consultation: Since the implementation of this model, there is an increase in the percentage of inpatient deaths with prior palliative care consultations; from 75% in fiscal year 2014 to 97% in fiscal year 2017.

Challenges/Limitations: Single clinic setting, with one oncologist and palliative care physician, palliative care staffing, clinic space, administrative support.

Conclusions: Studies are needed to show impact of palliative care integration on acute care utilization, hospice care accession and satisfaction with care. There is a need to explore improved training and structures for both oncology and palliative care teams.

Background: Early introduction of palliative care for oncology patients has demonstrated enhanced quality of life and satisfaction. We developed a model for integrating palliative care into outpatient oncology care.

Hypothesis: Optimal integration of oncology and palliative care requires palliative care clinician’s presence at initial, and many subsequent, patient encounters.

Objective: To implement and evaluate outpatient integrated oncology and palliative care.

Method: In January 2015, we implemented an integrated outpatient practice of oncology and palliative care with: Pre-clinic “huddle” among palliative care and oncology staff to identify patients in need of palliative care; shared palliative care-oncology appointments. Initial visit: New oncology patients are seen by an oncologist and palliative care physician together. Palliative care physician introduces palliative care and initiates advance care planning. Concurrent oncology-palliative care follow-up: High-risk patients (aggressive histology, progressing disease, etc) are followed by oncologist and palliative care physician. Palliative care physician facilitates goals of care discussions and addresses symptom management. End-of-life care: Hospice care remains a part of oncology care. Palliative care physician and oncology team co-manage all oncology patients enrolled in hospice care.

Results: Increase in palliative care consults from oncology clinics: After this intervention, there is a 10-fold increase in number of palliative care consultation requests from oncology clinics from fiscal year 2014 to 2017. Increase in percentage of inpatients deaths with prior palliative care consultation: Since the implementation of this model, there is an increase in the percentage of inpatient deaths with prior palliative care consultations; from 75% in fiscal year 2014 to 97% in fiscal year 2017.

Challenges/Limitations: Single clinic setting, with one oncologist and palliative care physician, palliative care staffing, clinic space, administrative support.

Conclusions: Studies are needed to show impact of palliative care integration on acute care utilization, hospice care accession and satisfaction with care. There is a need to explore improved training and structures for both oncology and palliative care teams.

Background: Early introduction of palliative care for oncology patients has demonstrated enhanced quality of life and satisfaction. We developed a model for integrating palliative care into outpatient oncology care.

Hypothesis: Optimal integration of oncology and palliative care requires palliative care clinician’s presence at initial, and many subsequent, patient encounters.

Objective: To implement and evaluate outpatient integrated oncology and palliative care.

Method: In January 2015, we implemented an integrated outpatient practice of oncology and palliative care with: Pre-clinic “huddle” among palliative care and oncology staff to identify patients in need of palliative care; shared palliative care-oncology appointments. Initial visit: New oncology patients are seen by an oncologist and palliative care physician together. Palliative care physician introduces palliative care and initiates advance care planning. Concurrent oncology-palliative care follow-up: High-risk patients (aggressive histology, progressing disease, etc) are followed by oncologist and palliative care physician. Palliative care physician facilitates goals of care discussions and addresses symptom management. End-of-life care: Hospice care remains a part of oncology care. Palliative care physician and oncology team co-manage all oncology patients enrolled in hospice care.

Results: Increase in palliative care consults from oncology clinics: After this intervention, there is a 10-fold increase in number of palliative care consultation requests from oncology clinics from fiscal year 2014 to 2017. Increase in percentage of inpatients deaths with prior palliative care consultation: Since the implementation of this model, there is an increase in the percentage of inpatient deaths with prior palliative care consultations; from 75% in fiscal year 2014 to 97% in fiscal year 2017.

Challenges/Limitations: Single clinic setting, with one oncologist and palliative care physician, palliative care staffing, clinic space, administrative support.

Conclusions: Studies are needed to show impact of palliative care integration on acute care utilization, hospice care accession and satisfaction with care. There is a need to explore improved training and structures for both oncology and palliative care teams.

How Can VA Optimize Palliative Oncology Care? Updates on AVAHO Palliative Care Research Committee Projects

Purpose: Palliative care is essential to oncology. This abstract describes the AVAHO Palliative Care Research Committee, its objectives, and ongoing projects that highlight the committee’s productive multidisciplinary and interinstitutional collaboration.

Background: The American Society of Clinical Oncology recommends palliative care for patients with metastatic lung cancer and other symptomatic advanced malignancies. VA mandates inpatient palliative care services for all medical facilities. However, it is not clearly known how palliative care is integrated into standard VA outpatient oncology practice. In addition, questions remain regarding the optimal way(s) to provide palliative oncology care. Established in 2015, the AVAHO Palliative Care Research Committee currently has over a dozen members from different VA institutions. The Committee’s mission is to develop partnerships among clinicians, pharmacists, social workers, researchers, and VA leadership with the shared goal of providing optimal palliative oncology care within the VA.

Methods: Last year, we identified 2 initial approaches to address these questions, and this year we will report on our progress. First, we submitted a proposal to the VA Evidence-Based Synthesis Program (ESP) to review the evidence regarding optimal palliative care delivery methods and the feasibility of providing on-site palliative care embedded into VA oncology clinics. The ESP accepted our proposal and plans to complete their review July 2017. Second, we proposed a project to assess on-site palliative care availability in VA oncology clinics. With the support of the 2017 AVAHO Research Scholarship, we are moving forward with this project to work with VA oncology providers to understand their referral patterns, available palliative care resources, and barriers to providing optimal palliative care.

Results: At the AVAHO 2017 meeting, we will review the VA ESP results on optimal palliative oncology care delivery. In addition, we will share the progress on our ongoing project to better understand VA oncologist’s referral patterns, resources, and barriers to providing optimal palliative oncology care.

Conclusions: The AVAHO Palliative Care Research Committee represents a multidisciplinary and inter-institutional collaboration with a common goal of optimizing VA palliative oncology care. This committee is a model of how AVAHO can foster productive collaborations.

Purpose: Palliative care is essential to oncology. This abstract describes the AVAHO Palliative Care Research Committee, its objectives, and ongoing projects that highlight the committee’s productive multidisciplinary and interinstitutional collaboration.

Background: The American Society of Clinical Oncology recommends palliative care for patients with metastatic lung cancer and other symptomatic advanced malignancies. VA mandates inpatient palliative care services for all medical facilities. However, it is not clearly known how palliative care is integrated into standard VA outpatient oncology practice. In addition, questions remain regarding the optimal way(s) to provide palliative oncology care. Established in 2015, the AVAHO Palliative Care Research Committee currently has over a dozen members from different VA institutions. The Committee’s mission is to develop partnerships among clinicians, pharmacists, social workers, researchers, and VA leadership with the shared goal of providing optimal palliative oncology care within the VA.

Methods: Last year, we identified 2 initial approaches to address these questions, and this year we will report on our progress. First, we submitted a proposal to the VA Evidence-Based Synthesis Program (ESP) to review the evidence regarding optimal palliative care delivery methods and the feasibility of providing on-site palliative care embedded into VA oncology clinics. The ESP accepted our proposal and plans to complete their review July 2017. Second, we proposed a project to assess on-site palliative care availability in VA oncology clinics. With the support of the 2017 AVAHO Research Scholarship, we are moving forward with this project to work with VA oncology providers to understand their referral patterns, available palliative care resources, and barriers to providing optimal palliative care.

Results: At the AVAHO 2017 meeting, we will review the VA ESP results on optimal palliative oncology care delivery. In addition, we will share the progress on our ongoing project to better understand VA oncologist’s referral patterns, resources, and barriers to providing optimal palliative oncology care.

Conclusions: The AVAHO Palliative Care Research Committee represents a multidisciplinary and inter-institutional collaboration with a common goal of optimizing VA palliative oncology care. This committee is a model of how AVAHO can foster productive collaborations.

Purpose: Palliative care is essential to oncology. This abstract describes the AVAHO Palliative Care Research Committee, its objectives, and ongoing projects that highlight the committee’s productive multidisciplinary and interinstitutional collaboration.

Background: The American Society of Clinical Oncology recommends palliative care for patients with metastatic lung cancer and other symptomatic advanced malignancies. VA mandates inpatient palliative care services for all medical facilities. However, it is not clearly known how palliative care is integrated into standard VA outpatient oncology practice. In addition, questions remain regarding the optimal way(s) to provide palliative oncology care. Established in 2015, the AVAHO Palliative Care Research Committee currently has over a dozen members from different VA institutions. The Committee’s mission is to develop partnerships among clinicians, pharmacists, social workers, researchers, and VA leadership with the shared goal of providing optimal palliative oncology care within the VA.

Methods: Last year, we identified 2 initial approaches to address these questions, and this year we will report on our progress. First, we submitted a proposal to the VA Evidence-Based Synthesis Program (ESP) to review the evidence regarding optimal palliative care delivery methods and the feasibility of providing on-site palliative care embedded into VA oncology clinics. The ESP accepted our proposal and plans to complete their review July 2017. Second, we proposed a project to assess on-site palliative care availability in VA oncology clinics. With the support of the 2017 AVAHO Research Scholarship, we are moving forward with this project to work with VA oncology providers to understand their referral patterns, available palliative care resources, and barriers to providing optimal palliative care.

Results: At the AVAHO 2017 meeting, we will review the VA ESP results on optimal palliative oncology care delivery. In addition, we will share the progress on our ongoing project to better understand VA oncologist’s referral patterns, resources, and barriers to providing optimal palliative oncology care.

Conclusions: The AVAHO Palliative Care Research Committee represents a multidisciplinary and inter-institutional collaboration with a common goal of optimizing VA palliative oncology care. This committee is a model of how AVAHO can foster productive collaborations.

Characterization of Hematology Consults for Complete Blood Count Abnormalities: A Single Center Experience in the Era of Electronic Consultation

Purpose: As patient volumes and complexity of hematology care increase, subspecialty provider efficiency is of utmost importance. We aim to improve efficiency by characterizing the nature and outcome of common hematology e-consults.

Background: Veterans Affairs Medical Centers pioneered electronic subspecialty consultation with the initiation of the e-consult system in 2011. An increase in number of hematology consultations at one VAMC from 391 in 2010 to 704 after e-consult implementation in 2013 was described by Cecchini et al (Blood, 2016).

Methods: A retrospective review of all hematology and oncology consults at one institution between April 1, 2016 and December 8, 2016 was performed. Cell counts, prior workup, diagnoses offered, age and comorbidities were determined for consults about complete blood count (CBC) abnormalities.

Results: 523 hematology/oncology consults were reviewed: 169 questioned CBC abnormalities, 76 consults were for anemia, and 38 consults were for thrombocytopenia. The most common diagnosis was iron-deficiency anemia (21.1% anemia consults). The most common hemoglobin value for anemia

consults was 9.0-9.9 g/dL (27.6% anemia consults). The most common platelet count for thrombocytopenia consults was 75k-100k (36.8% thrombocytopenia consults). Referring providers were significantly more likely to have initiated workup for anemia than for thrombocytopenia consults (71%

vs 29%, P < .0001). Consulting hematologists were significantly more likely to offer a diagnosis if basic workup had already been initiated (68% vs 39%, P = .0025). Age ≥ 70 years old had higher likelihood of 2-3 cell line abnormalities (RR 1.37, 95% CI, 1.02-1.82).

Conclusions: 169 consults about CBC abnormalities were reviewed. The most common reason for consult was anemia. Referring providers were significantly more likely to initiate a workup for anemia than for thrombocytopenia. There was a significantly greater likelihood of consultants offering a diagnosis if a basic workup had already been initiated. Increased education regarding mild anemia and basic workup of thrombocytopenia are areas of potential intervention to improve likelihood of diagnosis on initial consult and improve efficiency of the electronic consultation process.

Purpose: As patient volumes and complexity of hematology care increase, subspecialty provider efficiency is of utmost importance. We aim to improve efficiency by characterizing the nature and outcome of common hematology e-consults.

Background: Veterans Affairs Medical Centers pioneered electronic subspecialty consultation with the initiation of the e-consult system in 2011. An increase in number of hematology consultations at one VAMC from 391 in 2010 to 704 after e-consult implementation in 2013 was described by Cecchini et al (Blood, 2016).

Methods: A retrospective review of all hematology and oncology consults at one institution between April 1, 2016 and December 8, 2016 was performed. Cell counts, prior workup, diagnoses offered, age and comorbidities were determined for consults about complete blood count (CBC) abnormalities.

Results: 523 hematology/oncology consults were reviewed: 169 questioned CBC abnormalities, 76 consults were for anemia, and 38 consults were for thrombocytopenia. The most common diagnosis was iron-deficiency anemia (21.1% anemia consults). The most common hemoglobin value for anemia

consults was 9.0-9.9 g/dL (27.6% anemia consults). The most common platelet count for thrombocytopenia consults was 75k-100k (36.8% thrombocytopenia consults). Referring providers were significantly more likely to have initiated workup for anemia than for thrombocytopenia consults (71%

vs 29%, P < .0001). Consulting hematologists were significantly more likely to offer a diagnosis if basic workup had already been initiated (68% vs 39%, P = .0025). Age ≥ 70 years old had higher likelihood of 2-3 cell line abnormalities (RR 1.37, 95% CI, 1.02-1.82).

Conclusions: 169 consults about CBC abnormalities were reviewed. The most common reason for consult was anemia. Referring providers were significantly more likely to initiate a workup for anemia than for thrombocytopenia. There was a significantly greater likelihood of consultants offering a diagnosis if a basic workup had already been initiated. Increased education regarding mild anemia and basic workup of thrombocytopenia are areas of potential intervention to improve likelihood of diagnosis on initial consult and improve efficiency of the electronic consultation process.

Purpose: As patient volumes and complexity of hematology care increase, subspecialty provider efficiency is of utmost importance. We aim to improve efficiency by characterizing the nature and outcome of common hematology e-consults.

Background: Veterans Affairs Medical Centers pioneered electronic subspecialty consultation with the initiation of the e-consult system in 2011. An increase in number of hematology consultations at one VAMC from 391 in 2010 to 704 after e-consult implementation in 2013 was described by Cecchini et al (Blood, 2016).

Methods: A retrospective review of all hematology and oncology consults at one institution between April 1, 2016 and December 8, 2016 was performed. Cell counts, prior workup, diagnoses offered, age and comorbidities were determined for consults about complete blood count (CBC) abnormalities.

Results: 523 hematology/oncology consults were reviewed: 169 questioned CBC abnormalities, 76 consults were for anemia, and 38 consults were for thrombocytopenia. The most common diagnosis was iron-deficiency anemia (21.1% anemia consults). The most common hemoglobin value for anemia

consults was 9.0-9.9 g/dL (27.6% anemia consults). The most common platelet count for thrombocytopenia consults was 75k-100k (36.8% thrombocytopenia consults). Referring providers were significantly more likely to have initiated workup for anemia than for thrombocytopenia consults (71%

vs 29%, P < .0001). Consulting hematologists were significantly more likely to offer a diagnosis if basic workup had already been initiated (68% vs 39%, P = .0025). Age ≥ 70 years old had higher likelihood of 2-3 cell line abnormalities (RR 1.37, 95% CI, 1.02-1.82).

Conclusions: 169 consults about CBC abnormalities were reviewed. The most common reason for consult was anemia. Referring providers were significantly more likely to initiate a workup for anemia than for thrombocytopenia. There was a significantly greater likelihood of consultants offering a diagnosis if a basic workup had already been initiated. Increased education regarding mild anemia and basic workup of thrombocytopenia are areas of potential intervention to improve likelihood of diagnosis on initial consult and improve efficiency of the electronic consultation process.

Treatment Patterns Among Men With Metastatic Castrate-Resistant Prostate Cancer Within the United States Veterans Affairs Health System

Background: Therapeutic options for men with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) have expanded significantly over the past 5 years with several new agents demonstrating improved survival, including 2 oral agents. Abiraterone acetate (AA), a CYP-17 androgen synthesis inhibitor, obtained initial FDA approval in 2011 for post-docetaxel (DXT) use and gained expanded approval in 2012 for pre-DXT use. Enzalutamide (ENZ), an androgen receptor signaling inhibitor, also gained FDA approval in 2012 (post-DXT) and indication was expanded in 2014 (pre-DXT).

Purpose: The objective is to provide insight into the uptake of novel therapeutics and its impact on treatment for patients with mCRPC.

Methods: For this observational study, Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system data (including hospitalizations, outpatient visits, and pharmacy) were used to identify male veterans who received treatment for mCRPC between fiscal years 2008 and 2014. Sequencing patterns and treatment duration were assessed. Descriptive statistics were employed.

Results: During the study period, 8,774 patients initiated advanced lines of therapy associated with mCRPC. AA, DXT, and ketoconazole (KCZ) were the most commonly used firstlines of advanced therapies (24.6%, 24.8%, 47.0%, respectively). Between 2008 and 2013, the proportion of mCRPC patients treated with first-line DXT or KCZ dropped from 98% to 38% (P < .0001) while the proportion who received first-line AA increased to 58% (P < .0001). Furthermore, among the 4,169 patients treated with AA between 2011 and 2014, the proportion treated pre-DXT increased from 32% to 80% (P < .0001). AA was also the most common second-line treatment received. Between 2012 and 2013, ENZ use was low but increased dramatically. Among patients who initiated DXT, KCZ, or AA as first-line treatment in 2011/2012, median time on initial treatment was 5.9, 9.1, 11.5 months, respectively.

Conclusions: The FDA approval of AA and ENZ had a significant impact on treatment patterns for men with mCRPC within VA and was associated with decreased use of KCZ and delayed use of chemotherapy. Further information regarding patient and disease characteristics is needed. The rapid uptake of these novel agents has significant implications for disease-related outcomes.

Background: Therapeutic options for men with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) have expanded significantly over the past 5 years with several new agents demonstrating improved survival, including 2 oral agents. Abiraterone acetate (AA), a CYP-17 androgen synthesis inhibitor, obtained initial FDA approval in 2011 for post-docetaxel (DXT) use and gained expanded approval in 2012 for pre-DXT use. Enzalutamide (ENZ), an androgen receptor signaling inhibitor, also gained FDA approval in 2012 (post-DXT) and indication was expanded in 2014 (pre-DXT).

Purpose: The objective is to provide insight into the uptake of novel therapeutics and its impact on treatment for patients with mCRPC.

Methods: For this observational study, Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system data (including hospitalizations, outpatient visits, and pharmacy) were used to identify male veterans who received treatment for mCRPC between fiscal years 2008 and 2014. Sequencing patterns and treatment duration were assessed. Descriptive statistics were employed.

Results: During the study period, 8,774 patients initiated advanced lines of therapy associated with mCRPC. AA, DXT, and ketoconazole (KCZ) were the most commonly used firstlines of advanced therapies (24.6%, 24.8%, 47.0%, respectively). Between 2008 and 2013, the proportion of mCRPC patients treated with first-line DXT or KCZ dropped from 98% to 38% (P < .0001) while the proportion who received first-line AA increased to 58% (P < .0001). Furthermore, among the 4,169 patients treated with AA between 2011 and 2014, the proportion treated pre-DXT increased from 32% to 80% (P < .0001). AA was also the most common second-line treatment received. Between 2012 and 2013, ENZ use was low but increased dramatically. Among patients who initiated DXT, KCZ, or AA as first-line treatment in 2011/2012, median time on initial treatment was 5.9, 9.1, 11.5 months, respectively.

Conclusions: The FDA approval of AA and ENZ had a significant impact on treatment patterns for men with mCRPC within VA and was associated with decreased use of KCZ and delayed use of chemotherapy. Further information regarding patient and disease characteristics is needed. The rapid uptake of these novel agents has significant implications for disease-related outcomes.

Background: Therapeutic options for men with metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) have expanded significantly over the past 5 years with several new agents demonstrating improved survival, including 2 oral agents. Abiraterone acetate (AA), a CYP-17 androgen synthesis inhibitor, obtained initial FDA approval in 2011 for post-docetaxel (DXT) use and gained expanded approval in 2012 for pre-DXT use. Enzalutamide (ENZ), an androgen receptor signaling inhibitor, also gained FDA approval in 2012 (post-DXT) and indication was expanded in 2014 (pre-DXT).

Purpose: The objective is to provide insight into the uptake of novel therapeutics and its impact on treatment for patients with mCRPC.

Methods: For this observational study, Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system data (including hospitalizations, outpatient visits, and pharmacy) were used to identify male veterans who received treatment for mCRPC between fiscal years 2008 and 2014. Sequencing patterns and treatment duration were assessed. Descriptive statistics were employed.

Results: During the study period, 8,774 patients initiated advanced lines of therapy associated with mCRPC. AA, DXT, and ketoconazole (KCZ) were the most commonly used firstlines of advanced therapies (24.6%, 24.8%, 47.0%, respectively). Between 2008 and 2013, the proportion of mCRPC patients treated with first-line DXT or KCZ dropped from 98% to 38% (P < .0001) while the proportion who received first-line AA increased to 58% (P < .0001). Furthermore, among the 4,169 patients treated with AA between 2011 and 2014, the proportion treated pre-DXT increased from 32% to 80% (P < .0001). AA was also the most common second-line treatment received. Between 2012 and 2013, ENZ use was low but increased dramatically. Among patients who initiated DXT, KCZ, or AA as first-line treatment in 2011/2012, median time on initial treatment was 5.9, 9.1, 11.5 months, respectively.

Conclusions: The FDA approval of AA and ENZ had a significant impact on treatment patterns for men with mCRPC within VA and was associated with decreased use of KCZ and delayed use of chemotherapy. Further information regarding patient and disease characteristics is needed. The rapid uptake of these novel agents has significant implications for disease-related outcomes.

The Buck Stops Here: Rational Oversight for Hematologic Testing

Complex hematological tests aid in establishing hematologic diagnoses, but can be quite costly. We hypothesized that certain diagnostic tests (specifically JAK2 at $175/test, BCR-ABL at $163/test, and flow cytometry at $275/test) that were being ordered without input from a hematologist were generally not indicated and expensive. We reviewed all of these tests sent between September 2013 and September 2015. 20/55 or 36% of JAK2 mutations, 19/37 or 51% of BCR-ABL mutations, and 47/74 or 63% of flow cytometry were completed without hematology input, primarily via primary care (72/86 or 84%). Tests that were ordered or recommended by hematology were excluded from the subsequent cost analysis. In total $19,500 was spent (without hematology input). One hematologist then reviewed the charts on every test that had been ordered not by hematology to determine if the test was clinically appropriate. 12/20 or 60% of JAK2 mutations, 19/19 or 100% of BCR mutations, and 44/47 or 94% of flow cytometry evaluations were felt to be unnecessary. Thus $17,300 of the $19,500 could have been saved had there been hematology input at the outset. This would have amounted to 86 e-consults over 2 years, which would be 1.2 extra consults/week; these consults generally take under 10 minutes, so less than 2 minutes/day. This all translates to ~$1,075 over 2 years of a hematologist’s salary, clearly more cost-effective than permitting everyone to be able to order these tests. We should consider recommending hematology input prior to allowing these tests (and perhaps other costly unusual hematology investigations) to be sent out, perhaps via a pop-up suggestion for a hematology e-consult when ordered; the e-consult would also be a tool to educate other providers on the appropriate use of these tests and may ultimately lead to a decrease in the ordering of these e-consults.

Complex hematological tests aid in establishing hematologic diagnoses, but can be quite costly. We hypothesized that certain diagnostic tests (specifically JAK2 at $175/test, BCR-ABL at $163/test, and flow cytometry at $275/test) that were being ordered without input from a hematologist were generally not indicated and expensive. We reviewed all of these tests sent between September 2013 and September 2015. 20/55 or 36% of JAK2 mutations, 19/37 or 51% of BCR-ABL mutations, and 47/74 or 63% of flow cytometry were completed without hematology input, primarily via primary care (72/86 or 84%). Tests that were ordered or recommended by hematology were excluded from the subsequent cost analysis. In total $19,500 was spent (without hematology input). One hematologist then reviewed the charts on every test that had been ordered not by hematology to determine if the test was clinically appropriate. 12/20 or 60% of JAK2 mutations, 19/19 or 100% of BCR mutations, and 44/47 or 94% of flow cytometry evaluations were felt to be unnecessary. Thus $17,300 of the $19,500 could have been saved had there been hematology input at the outset. This would have amounted to 86 e-consults over 2 years, which would be 1.2 extra consults/week; these consults generally take under 10 minutes, so less than 2 minutes/day. This all translates to ~$1,075 over 2 years of a hematologist’s salary, clearly more cost-effective than permitting everyone to be able to order these tests. We should consider recommending hematology input prior to allowing these tests (and perhaps other costly unusual hematology investigations) to be sent out, perhaps via a pop-up suggestion for a hematology e-consult when ordered; the e-consult would also be a tool to educate other providers on the appropriate use of these tests and may ultimately lead to a decrease in the ordering of these e-consults.

Complex hematological tests aid in establishing hematologic diagnoses, but can be quite costly. We hypothesized that certain diagnostic tests (specifically JAK2 at $175/test, BCR-ABL at $163/test, and flow cytometry at $275/test) that were being ordered without input from a hematologist were generally not indicated and expensive. We reviewed all of these tests sent between September 2013 and September 2015. 20/55 or 36% of JAK2 mutations, 19/37 or 51% of BCR-ABL mutations, and 47/74 or 63% of flow cytometry were completed without hematology input, primarily via primary care (72/86 or 84%). Tests that were ordered or recommended by hematology were excluded from the subsequent cost analysis. In total $19,500 was spent (without hematology input). One hematologist then reviewed the charts on every test that had been ordered not by hematology to determine if the test was clinically appropriate. 12/20 or 60% of JAK2 mutations, 19/19 or 100% of BCR mutations, and 44/47 or 94% of flow cytometry evaluations were felt to be unnecessary. Thus $17,300 of the $19,500 could have been saved had there been hematology input at the outset. This would have amounted to 86 e-consults over 2 years, which would be 1.2 extra consults/week; these consults generally take under 10 minutes, so less than 2 minutes/day. This all translates to ~$1,075 over 2 years of a hematologist’s salary, clearly more cost-effective than permitting everyone to be able to order these tests. We should consider recommending hematology input prior to allowing these tests (and perhaps other costly unusual hematology investigations) to be sent out, perhaps via a pop-up suggestion for a hematology e-consult when ordered; the e-consult would also be a tool to educate other providers on the appropriate use of these tests and may ultimately lead to a decrease in the ordering of these e-consults.

How Can VA Optimize Palliative Oncology Care? The AVAHO Palliative Care Research Subcommittee Is Laying the Groundwork for Productive Collaboration

Purpose: Palliative Care is essential to Oncology. The purpose of this abstract is to describe the AVAHO Palliative Care Research subcommittee, its objectives, and evidence of its productive multi-disciplinary and inter-institutional collaboration.

Background: The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommends Palliative Care for all patients with metastatic lung cancer and other symptomatic advanced malignancies. VA mandates Palliative Care inpatient consult teams for all medical facilities. It is not clearly known how Palliative Care is integrated into standard VA outpatient Oncology practice. In addition, questions remain regarding the optimal way(s) to provide Palliative Oncology Care. The AVAHO Palliative Care Research subcommittee was established in 2015 and currently has 7 members from 7 VA institutions. The mission of the subcommittee is to develop partnerships among VA clinicians, pharmacists, social workers, researchers, and VA leadership with the shared goal of providing optimal Palliative Oncology Care within the VA. In laying the groundwork for productive collaboration, we have identified a need to better understand the current interface between VA Oncology Clinics and Palliative Care teams. In particular, we seek to review the evidence for providing on-site Palliative Care to patients with advanced malignancies, and we seek to understand the current availability of outpatient Palliative Care within VA outpatient Oncology clinics.

Methods: We have identified 2 initial approaches to address these questions. First, we have submitted a proposal to the VA Evidence-Based Synthesis Program (ESP) to review the evidence regarding optimal Palliative Care delivery methods for patients with advanced malignancies and

the feasibility of providing on-site Palliative Care embedded into VA Oncology clinics. Second, we plan to survey current VA Oncology providers to understand their Palliative Care referral patterns, available on-site resources, and barriers to providing optimal Palliative Care for their patients.

Analysis/Results: At the AVAHO 2016 meeting, we will provide updated information on the ESP proposal and the Palliative Care in Oncology Survey.

Conclusion: The AVAHO Palliative Care Research subcommittee represents a multidisciplinary and inter-institutional collaboration with a common goal of optimizing VA Palliative Oncology Care. This subcommittee is a model of how AVAHO can foster productive collaborations. We welcome new members.

Purpose: Palliative Care is essential to Oncology. The purpose of this abstract is to describe the AVAHO Palliative Care Research subcommittee, its objectives, and evidence of its productive multi-disciplinary and inter-institutional collaboration.

Background: The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommends Palliative Care for all patients with metastatic lung cancer and other symptomatic advanced malignancies. VA mandates Palliative Care inpatient consult teams for all medical facilities. It is not clearly known how Palliative Care is integrated into standard VA outpatient Oncology practice. In addition, questions remain regarding the optimal way(s) to provide Palliative Oncology Care. The AVAHO Palliative Care Research subcommittee was established in 2015 and currently has 7 members from 7 VA institutions. The mission of the subcommittee is to develop partnerships among VA clinicians, pharmacists, social workers, researchers, and VA leadership with the shared goal of providing optimal Palliative Oncology Care within the VA. In laying the groundwork for productive collaboration, we have identified a need to better understand the current interface between VA Oncology Clinics and Palliative Care teams. In particular, we seek to review the evidence for providing on-site Palliative Care to patients with advanced malignancies, and we seek to understand the current availability of outpatient Palliative Care within VA outpatient Oncology clinics.

Methods: We have identified 2 initial approaches to address these questions. First, we have submitted a proposal to the VA Evidence-Based Synthesis Program (ESP) to review the evidence regarding optimal Palliative Care delivery methods for patients with advanced malignancies and

the feasibility of providing on-site Palliative Care embedded into VA Oncology clinics. Second, we plan to survey current VA Oncology providers to understand their Palliative Care referral patterns, available on-site resources, and barriers to providing optimal Palliative Care for their patients.

Analysis/Results: At the AVAHO 2016 meeting, we will provide updated information on the ESP proposal and the Palliative Care in Oncology Survey.

Conclusion: The AVAHO Palliative Care Research subcommittee represents a multidisciplinary and inter-institutional collaboration with a common goal of optimizing VA Palliative Oncology Care. This subcommittee is a model of how AVAHO can foster productive collaborations. We welcome new members.

Purpose: Palliative Care is essential to Oncology. The purpose of this abstract is to describe the AVAHO Palliative Care Research subcommittee, its objectives, and evidence of its productive multi-disciplinary and inter-institutional collaboration.

Background: The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommends Palliative Care for all patients with metastatic lung cancer and other symptomatic advanced malignancies. VA mandates Palliative Care inpatient consult teams for all medical facilities. It is not clearly known how Palliative Care is integrated into standard VA outpatient Oncology practice. In addition, questions remain regarding the optimal way(s) to provide Palliative Oncology Care. The AVAHO Palliative Care Research subcommittee was established in 2015 and currently has 7 members from 7 VA institutions. The mission of the subcommittee is to develop partnerships among VA clinicians, pharmacists, social workers, researchers, and VA leadership with the shared goal of providing optimal Palliative Oncology Care within the VA. In laying the groundwork for productive collaboration, we have identified a need to better understand the current interface between VA Oncology Clinics and Palliative Care teams. In particular, we seek to review the evidence for providing on-site Palliative Care to patients with advanced malignancies, and we seek to understand the current availability of outpatient Palliative Care within VA outpatient Oncology clinics.

Methods: We have identified 2 initial approaches to address these questions. First, we have submitted a proposal to the VA Evidence-Based Synthesis Program (ESP) to review the evidence regarding optimal Palliative Care delivery methods for patients with advanced malignancies and

the feasibility of providing on-site Palliative Care embedded into VA Oncology clinics. Second, we plan to survey current VA Oncology providers to understand their Palliative Care referral patterns, available on-site resources, and barriers to providing optimal Palliative Care for their patients.

Analysis/Results: At the AVAHO 2016 meeting, we will provide updated information on the ESP proposal and the Palliative Care in Oncology Survey.

Conclusion: The AVAHO Palliative Care Research subcommittee represents a multidisciplinary and inter-institutional collaboration with a common goal of optimizing VA Palliative Oncology Care. This subcommittee is a model of how AVAHO can foster productive collaborations. We welcome new members.