User login

The Treatment of Gout

Managing the Multiple Symptoms of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia — CME

Managing Type 2 Diabetes in Men

Meeting New Challenges with Antiplatelet Therapy in Primary Care

Dr. Ruoff has disclosed that he is on the speakers’ bureau for and has received research grants from Takeda Pharmaceuticals.

SUPPORT

This program is sponsored by the PCEC and is supported by funding from URL Pharma, Inc.

DB is a 50-year-old obese male visiting the clinic for symptoms suggestive of allergic rhinitis. The nurse has informed the family physician that DB was limping from the waiting room to the examination room. DB reports that he has been experiencing pain in his left big toe and ankle over the past few days. The last time this happened, the pain resolved within 7 to 10 days.

DB reports that he has experienced 4 or 5 similar episodes over the past 3 years. The first attacks affected his left big toe, but he now also experiences some pain in his left ankle. The pain is moderate, peaks in 1 to 2 days, and resolves within 7 to 10 days. Acetaminophen provided little pain relief so DB now takes ibuprofen 400 mg 3 times daily, as it “helps take the edge off.” Other medications include aspirin 81 mg per day and an oral antihistamine as needed for hay fever. DB reports that he eats seafood 2 to 3 times per week and red meat 1 to 2 times per week; he drinks 2 six-packs of beer per week.

Physical examination: weight, 186 lb (body mass index [BMI], 27 kg/m2); blood pressure, 126/76 mm Hg; and temperature, 98.8°F. His left big toe and ankle are red, slightly swollen, and warm with a small subcutaneous nodule noted on the first metatarsophalangeal joint. There is no sign of skin or joint infection.

The impression from his history and physical exam is that DB is suffering from an acute attack of gout, but the family physician also considers other diagnoses.

Background

Gout is a heterogeneous disorder that peaks in incidence in the fifth decade. Gout is caused by hyperuricemia, generally as a result of reduced excretion of uric acid by the kidneys; hyperuricemia may also result from overproduction of uric acid. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007-2008 indicate that the prevalence of gout continues to rise in the United States, likely related to the increasing frequency of adiposity and hypertension. Overall, about 75% of the 8.3 million people with gout are men.1

Risk Factors

Clinically defined hyperuricemia—a serum urate (sUA) level greater than 6.8 mg/dL, the concentration at which urate exceeds its solubility in most biological fluids—is the major risk factor for gout. However, not all persons with hyperuricemia have gout. Data from NHANES 2007-2008, in which the definition of hyperuricemia was an sUA level greater than 7.0 mg/dL for men and greater than 5.7 mg/dL for women, showed the mean sUA level to be 6.1 mg/dL in men and 4.9 mg/dL in women, corresponding to hyperuricemia prevalences of 21.2% and 21.6%, respectively.1

There are several other risk factors for gout, including hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and metabolic syndrome.2 For a man with hypertension, the relative risk (RR) of gout is 2.3 compared with a normotensive man.3 Furthermore, it is well established that the use of diuretics increases the risk of gout (RR, 1.8).3 Several other medications increase sUA level as well: aspirin (including low-dose), cyclosporine, pyrazinamide, ethambutol, and niacin.2

Lifestyle and diet also pose a risk for gout. The risk of gout increases with BMI such that, compared with a man with a BMI of 21 to 22.9 kg/m2, the RR of gout is doubled for a man with a BMI of 25 to 29.9 kg/m2; for a man with a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or more, the RR is tripled.3 Sugar-sweetened soft drinks (but not diet soft drinks) and fructose-rich fruits and fruit juices also increase the risk of gout, as do a high alcohol intake, particularly beer, and a diet rich in meat (especially organ meat, turkey, or wild game) or seafood.4 A moderate intake of purine-rich vegetables (eg, peas, beans, lentils, spinach, mushrooms, oatmeal, and cauliflower) or protein is not associated with an increased risk of gout, while a high consumption of dairy products is associated with a decreased risk.5,6

Untreated or poorly treated gout usually leads to further acute attacks and progressive joint and tissue damage. In addition, gout and hyperuricemia serve as risk factors for other diseases. Adults with gout are 3 times as likely to develop metabolic syndrome as adults without gout.7 An elevated sUA level is also an independent risk factor for the development of hypertension (RR, 1.1), as well as myocardial infarction (MI; RR, 1.9), and stroke (RR, 1.6).8,9 An increasing sUA level also increases the risk of renal failure.10,11 In a study of 49,413 men followed for a mean of 5.4 years, the age-adjusted RR of renal failure was 1.5 in men with an sUA level of 6.5 to 8.4 mg/dL and 8.5 in men with an sUA level of 8.5 to 13.0 mg/dL compared with men with an sUA level of 5.0 to 6.4 mg/dL.11

Clinical Presentation

The deposition of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals in joints and tissues is very common and typically causes no signs or symptoms in the majority of persons. Even in men with an sUA level of 9 mg/dL or greater, the cumulative incidence of gouty arthritis has been found to be 22% over 5 years.12 However, as crystal deposition progresses, acute, painful attacks occur more frequently, with the development of chronic tophaceous gout after several years.13

Laboratory results for DB:

- Serum uric acid, 7.9 mg/dL

- White blood cell count, 15,800/mm3

- Serum creatinine, 1.2 mg/dL (estimated creatinine clearance, 90 mL/min)

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 23 mm/h

- Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (nonfasting), 127 mg/dL

Laboratory confirmation of hyperuricemia together with the pain, swelling, and tenderness of DB’s toe and ankle, other findings from his medical history and physical exam (eg, the use of aspirin daily), and exclusion of alternative diagnoses, such as septic arthritis, enable the family physician to arrive at a presumptive diagnosis of gouty arthritis. Aspiration of MSU crystals from DB’s toe or ankle is the gold standard and would allow for a definitive diagnosis. Although the sUA level was found to be high, it should be noted that a normal sUA level is often found during an acute attack; should this occur, the sUA level should be checked again 1 to 2 weeks after the acute attack has resolved.

Goals of Treatment

The cornerstone of gout management is daily, long-term treatment with urate-lowering therapy (ULT) combined with as-needed treatment for an acute attack. In addition, since initiation of ULT mobilizes MSU crystals, which often leads to a short-term increase in acute attacks, prophylaxis with an appropriate anti-inflammatory therapy is recommended at the time ULT is initiated.14

The therapeutic goals of gout treatment are 2-pronged: treatment of an acute gout attack and management of chronic gout. For an acute attack, the goals are to exclude a diagnosis of septic arthritis; reduce inflammation and terminate the attack; and seek, assess, and control associated diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and CVD. If this latter goal is not possible during the acute attack, plans should be made to assess associated diseases once the acute attack has resolved.14 Lowering the sUA level is not a goal of therapy for an acute attack, but it is the primary goal of ULT for chronic gout. Lowering the sUA level to less than 6.0 mg/dL, which is well below the saturation point of urate in most biological fluids, is intended to prevent further acute attacks, tophus formation, and tissue damage.14

Treatment of an Acute Attack

The mainstay of treatment for an acute attack is anti-inflammatory therapy to reduce pain and inflammation.14 Therapy should be initiated at the onset of the attack and continued until the attack is terminated, which is typically 1 to 2 weeks. Anti-inflammatory therapy traditionally has in-cluded colchicine, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), or a corticosteroid.14

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

The NSAIDs are all thought to provide similar efficacy when used in maximum doses.15,16 Since gastrointestinal toxicity is a concern with NSAIDs, coadministration of a proton pump inhibitor, H2 antagonist, or misoprostol is advised for patients with an increased risk of peptic ulcers, bleeds, or perforations.17 The risk of MI, stroke, cardiovascular death, and atrial fibrillation/flutter with NSAID therapy should be considered, especially because gout often coexists with cardiovascular disorders.15,18,19 Furthermore, NSAIDs are contraindicated in patients with heart failure or renal insufficiency.20,21

Corticosteroids. A systematic review of clinical trials involving systemic corticosteroids that found a few prospective trials of low to moderate quality concluded that there was inconclusive evidence for the efficacy and effectiveness of corticosteroids in the treatment of acute gout.22 No serious adverse events (AEs) were reported. A more recent prospective trial found comparable pain reduction and incidence of AEs with naproxen 500 mg twice daily and prednisolone 35 mg once daily for 5 days in patients with monoarticular gout.23 Furthermore, clinical experience indicates that intra-articular aspiration and injection of a long-acting corticosteroid is an effective and safe treatment for an acute attack.14,15 Corticosteroids may be useful in patients who have an inadequate response to, are intolerant of, or have a contraindication to NSAIDs and colchicine.14,15

Colchicine. Much of the recent clinical investigation regarding pharmacologic treatment of an acute gout attack has involved colchicine. To overcome the limitations of the standard dose-to-toxicity regimen of colchicine, a low-dose regimen of colchicine (1.2 mg followed by 0.6 mg 1 hour later) was investigated and subsequently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).24

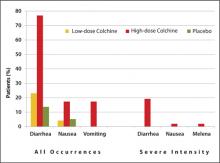

Approval was based on a randomized, double-blind comparison with high-dose colchicine (1.2 mg followed by 0.6 mg every hour for 6 hours) and placebo in 184 patients with an acute gout attack.25 The primary endpoint, a 50% or greater reduction in pain at 24 hours without the use of rescue medication, was reached in 28 of 74 patients (38%) in the low-dose group, 17 of 52 patients (33%) in the high-dose group, and 9 of 58 patients (16%) in the placebo group (P = .005 and P = .034, respectively, versus placebo). An AE occurred in 36.5% and 76.9% of study participants in the low-dose and high-dose colchicine groups, respectively, and in 27.1% of participants in the placebo group. Gastrointestinal AEs (eg, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting) were less common in the low-dose colchicine group ( FIGURE ). All AEs in the low-dose group were mild to moderate in intensity, while 10 of 52 patients (19.2%) in the high-dose group had an AE of severe intensity. Concomitant use of numerous drugs can increase the concentration of colchicine. Examples include atorvastatin, fluvastatin, pravastatin, simvastatin, fibrates, gemfibrozil, digoxin, clarithromycin, erythromycin, fluconazole, itraconazole, ketoconazole, protease inhibitors, diltiazem, verapamil, and cyclosporine, as well as grapefruit juice.26

FIGURE

Frequency of selected adverse events occurring over 24 hours with low-dose vs high-dose colchicine25

Treatment plan:

TABLE

Care plan for a patient with gout27

| Acute flare | Chronic gout | |

|---|---|---|

| Goals |

|

|

| Educational points |

|

|

| sUA, serum uric acid; ULT, urate-lowering therapy. Source: Reproduced with permission. Becker MA, et al. J Fam Pract. 2010;59(6):S1-S8. Quadrant HealthCom Inc. Copyright 2010. | ||

Urate-Lowering Therapy

Urate lowering therapy is indicated for most, but not all, patients with gout. ULT is generally not recommended for those who have suffered a single attack of gout and have no complications, since 40% of these patients will not experience another attack within a year. However, should a second attack occur within a year of the first attack, ULT is recommended. Some patients who have experienced a single attack may elect to initiate ULT after being educated about the risks of the disease and the risks and benefits of ULT.14 Patients who have had an attack of gout and also have a comorbidity (eg, visible gouty tophi, renal insufficiency, uric acid stones, or use of a diuretic for hypertension) should begin ULT, since the risk of further attacks is higher in these patients, and kidney or joint damage is more likely.17

Initiation of ULT should not occur until 1 to 2 weeks after an acute attack has resolved, since beginning ULT during an acute attack is thought to prolong the attack.17 Because gout is a chronic, largely self-managed disease, patient education is a cornerstone of successful long-term treatment. Implementation of a care plan for both an acute flare and chronic gout is recommended ( TABLE ).27

Anti-inflammatory prophylaxis should begin at the same time that ULT is initiated, since an acute attack is likely due to a transient rise in the sUA level resulting from mobilization of MSU crystals. Colchicine, which is the only drug approved by the FDA for prophylaxis of an acute gout attack, can be used daily in a low-dose regimen (0.6 mg once or twice daily) for up to 6 months.17,26 Alternatively, an NSAID can be used.17

One recent investigation pooled the results of 3 phase III clinical trials of ULT in 4101 patients with gout.28 Patients received prophylaxis for 8 weeks or 6 months with low-dose colchicine 0.6 mg once daily or the combination of naproxen 250 mg twice daily with lansoprazole 15 mg once daily. The incidence of acute gout attacks increased sharply (up to 40%) at the end of 8 weeks of prophylaxis with either colchicine or naproxen and then declined steadily, whereas the rates of acute attacks were consistently low (3% to 5%) at the end of 6 months of prophylaxis with either colchicine or naproxen/lansoprazole. With the 8-week prophylaxis regimen, diarrhea was more common in the colchicine group (n = 993) than in the naproxen group (n = 829) (8.4% vs 2.7%, respectively; P < .001). With the 6-month prophylaxis regimen, liver function abnormalities (7.7% vs 4.3%; P = .023) and headache (2.8% vs 0.9%; P = .037) were more common with colchicine (n = 1807) than naproxen, while gastrointestinal/abdominal pains (3.2% vs 1.2%; P = .012) and dental/oral soft tissue infections (2.3% vs 0.6%; P = .006) were more common with naproxen (n = 346) than colchicine.

Uricostatic Agents

Uricostatic therapy with a xanthine oxidase inhibitor (ie, allopurinol or febuxostat) is the most commonly used ULT. Allopurinol is effective in lowering the sUA level and has been shown to lower the rates of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events, and, in patients with chronic kidney disease, slow the progression of renal disease.29,30 One key point that must be kept in mind is that the efficacy of allopurinol to lower the sUA level is dose-dependent, although limited safety data are available for doses >300 mg per day.14,31,32 One recent prospective clinical trial showed that 26% of patients achieved an sUA level of 5 mg/dL or less following 2 months of treatment with allopurinol 300 mg per day compared with 78% of those who subsequently doubled the dose to 300 mg twice daily.31 Two patients discontinued treatment with allopurinol because of an AE. Finally, the dose of allopurinol must be adjusted based on renal function to minimize the risk of AEs, particularly skin rashes.33

Febuxostat is also effective in lowering the sUA level. In patients with an sUA level of 8.0 mg/dL or higher and a creatinine clearance of 50 mL/min or higher at baseline, an sUA level of less than 6.0 mg/dL was achieved in 53% of patients treated with febuxostat 80 mg (n = 256) versus 21% of patients treated with allopurinol 300 mg once daily (n = 253) after 1 year (P < .001).34 The most frequent treatment-related AE was liver function abnormality, which occurred in 4% of patients in each group. Results of a 6-month trial showed that achievement of an sUA level of less than 6.0 mg/dL was achieved in 45% and 67% of patients treated with febuxostat 40 mg or 80 mg daily, respectively, and 42% of those treated with allopurinol 300 mg (200 mg in moderate renal impairment) daily.35 Febuxostat also has been shown to slow the progression of, or even stabilize, renal function.36

Treatment plan (continued):

- For an acute gout attack: Continue colchicine as needed

- ULT: Initiate allopurinol 100 mg once daily; increase to 200 mg once daily in 1 week, and 300 mg once daily in another week

- -Alternatively, initiate febuxostat 40 mg once daily; increase to 80 mg once daily if an sUA level of less than 6.0 mg/dL is not achieved within 2 weeks

- For prophylaxis of an acute attack when initiating ULT: Initiate colchicine 0.6 mg once daily; may increase to 0.6 mg twice daily if needed

- -Alternatively, initiate naproxen 250 mg twice daily with a proton pump inhibitor

- Measure sUA in 1 month; if the sUA level is greater than 6.0 mg/dL, increase allopurinol to 200 mg twice daily

- -Measure sUA in 1 month; if the sUA level is still greater than 6.0 mg/dL, increase allopurinol to 300 mg twice daily

- Implement the care plan ( TABLE )27

- -Inquire about and address issues to promote adherence and self-management

- -Discuss the most common AEs with allopurinol and colchicine and the actions the patient should take if an AE occurs

- Once the sUA level is 6.0 mg/dL or less, monitor sUA annually (including serum creatinine)14

1. Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK. Prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007-2008. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(10):3136-3141.

2. Weaver AL. Epidemiology of gout. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75(suppl 5):S9-S12.

3. Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Curhan G. Obesity, weight change, hypertension, diuretic use, and risk of gout in men: the health professionals follow-up study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(7):742-748.

4. Choi HK, Curhan G. Soft drinks, fructose consumption, and the risk of gout in men: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336(7639):309-312.

5. Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Willett W, Curhan G. Purine-rich foods, dairy and protein intake, and the risk of gout in men. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(11):1093-1103.

6. Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Willett W, Curhan G. Alcohol intake and risk of incident gout in men: a prospective study. Lancet. 2004;363(9417):1277-1281.

7. Choi HK, Ford ES, Li C, Curhan G. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with gout: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(1):109-115.

8. Perlstein TS, Gumieniak O, Williams GH, et al. Uric acid and the development of hypertension: the normative aging study. Hypertension. 2006;48(6):1031-1036.

9. Bos MJ, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, Witteman JC, Breteler MM. Uric acid is a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke: the Rotterdam study. Stroke. 2006;37(6):1503-1507.

10. Iseki K, Ikemiya Y, Inoue T, Iseki C, Kinjo K, Takishita S. Significance of hyperuricemia as a risk factor for developing ESRD in a screened cohort. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44(4):642-650.

11. Tomita M, Mizuno S, Yamanaka H, et al. Does hyperuricemia affect mortality? A prospective cohort study of Japanese male workers. J Epidemiol. 2000;10(6):403-409.

12. Campion EW, Glynn RJ, DeLabry LO. Asymptomatic hyperuricemia. Risks and consequences in the Normative Aging Study. Am J Med. 1987;82(3):421-426.

13. Mandell BF. Clinical manifestations of hyperuricemia and gout. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75(Suppl 5):S5-S8.

14. Hamburger M, Baraf HS, Adamson TC III, et al. 2011 Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of gout and hyperuricemia. Postgrad Med. 2011;123 (6 suppl 1):3-36.

15. Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T, et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part II: Management. Report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(10):1312-1324.

16. Schumacher HR Jr, Boice JA, Daikh DI, et al. Randomised double blind trial of etoricoxib and indometacin in treatment of acute gouty arthritis. BMJ. 2002;324(7352):1488-1492.

17. Jordan KM, Cameron JS, Snaith M, et al. British Society for Rheumatology and British Health Professionals in Rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46(8):1372-1374.

18. Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S, et al. Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:c7086.-

19. Schmidt M, Christiansen CF, Mehnert F, Rothman KJ, Sorensen HT. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and risk of atrial fibrillation or flutter: population based case-control study. BMJ. 2011;343:d3450.-

20. NSAIDS and chronic kidney disease. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/news/docs/nsaid_video.htm. Published 2012. Accessed April 22, 2012.

21. Gislason GH, Rasmussen JN, Abildstrom SZ, et al. Increased mortality and cardiovascular morbidity associated with use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in chronic heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(2):141-149.

22. Janssens HJ, Lucassen PL, Van de Laar FA, Janssen M, Van de Lisdonk EH. Systemic corticosteroids for acute gout. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD005521.-

23. Janssens HJ, Janssen M, van de Lisdonk EH, van Riel PL, van Weel C. Use of oral prednisolone or naproxen for the treatment of gout arthritis: a double-blind, randomised equivalence trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9627):1854-1860.

24. Schlesinger N, Schumacher R, Catton M, Maxwell L. Colchicine for acute gout. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD006190.-

25. Terkeltaub RA, Furst DE, Bennett K, Kook KA, Crockett RS, Davis MW. High versus low dosing of oral colchicine for early acute gout flare: Twenty-four-hour outcome of the first multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, dose-comparison colchicine study. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(4):1060-1068.

26. Colcrys [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: AR Scientific, Inc.; 2011.

27. Becker MA, Ruoff GE. What do I need to know about gout? J Fam Pract. 2010;59(6 suppl):S1-S8.

28. Wortmann RL, Macdonald PA, Hunt B, Jackson RL. Effect of prophylaxis on gout flares after the initiation of urate-lowering therapy: analysis of data from three phase III trials. Clin Ther. 2010;32(14):2386-2397.

29. Luk AJ, Levin GP, Moore EE, Zhou XH, Kestenbaum BR, Choi HK. Allopurinol and mortality in hyperuricaemic patients. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48(7):804-806.

30. Goicoechea M, de Vinuesa SG, Verdalles U, et al. Effect of allopurinol in chronic kidney disease progression and cardiovascular risk. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(8):1388-1393.

31. Reinders MK, Haagsma C, Jansen TL, et al. A randomised controlled trial on the efficacy and tolerability with dose escalation of allopurinol 300-600 mg/day versus benzbromarone 100-200 mg/day in patients with gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(6):892-897.

32. Stamp LK, O’Donnell JL, Zhang M, et al. Using allopurinol above the dose based on creatinine clearance is effective and safe in patients with chronic gout, including those with renal impairment. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(2):412-421.

33. Zyloprim [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Prometheus Laboratories Inc.; 2003.

34. Becker MA, Schumacher HR Jr, Wortmann RL, et al. Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2450-2461.

35. Becker MA, Schumacher HR, Espinoza LR, et al. The urate-lowering efficacy and safety of febuxostat in the treatment of the hyperuricemia of gout: the CONFIRMS trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:doi:10.1186/ar2978.

36. Whelton A, Macdonald PA, Zhao L, Hunt B, Gunawardhana L. Renal function in gout: long-term treatment effects of febuxostat. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17(1):7-13.

Managing the Multiple Symptoms of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia — CME

Managing Type 2 Diabetes in Men

Meeting New Challenges with Antiplatelet Therapy in Primary Care

Dr. Ruoff has disclosed that he is on the speakers’ bureau for and has received research grants from Takeda Pharmaceuticals.

SUPPORT

This program is sponsored by the PCEC and is supported by funding from URL Pharma, Inc.

DB is a 50-year-old obese male visiting the clinic for symptoms suggestive of allergic rhinitis. The nurse has informed the family physician that DB was limping from the waiting room to the examination room. DB reports that he has been experiencing pain in his left big toe and ankle over the past few days. The last time this happened, the pain resolved within 7 to 10 days.

DB reports that he has experienced 4 or 5 similar episodes over the past 3 years. The first attacks affected his left big toe, but he now also experiences some pain in his left ankle. The pain is moderate, peaks in 1 to 2 days, and resolves within 7 to 10 days. Acetaminophen provided little pain relief so DB now takes ibuprofen 400 mg 3 times daily, as it “helps take the edge off.” Other medications include aspirin 81 mg per day and an oral antihistamine as needed for hay fever. DB reports that he eats seafood 2 to 3 times per week and red meat 1 to 2 times per week; he drinks 2 six-packs of beer per week.

Physical examination: weight, 186 lb (body mass index [BMI], 27 kg/m2); blood pressure, 126/76 mm Hg; and temperature, 98.8°F. His left big toe and ankle are red, slightly swollen, and warm with a small subcutaneous nodule noted on the first metatarsophalangeal joint. There is no sign of skin or joint infection.

The impression from his history and physical exam is that DB is suffering from an acute attack of gout, but the family physician also considers other diagnoses.

Background

Gout is a heterogeneous disorder that peaks in incidence in the fifth decade. Gout is caused by hyperuricemia, generally as a result of reduced excretion of uric acid by the kidneys; hyperuricemia may also result from overproduction of uric acid. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007-2008 indicate that the prevalence of gout continues to rise in the United States, likely related to the increasing frequency of adiposity and hypertension. Overall, about 75% of the 8.3 million people with gout are men.1

Risk Factors

Clinically defined hyperuricemia—a serum urate (sUA) level greater than 6.8 mg/dL, the concentration at which urate exceeds its solubility in most biological fluids—is the major risk factor for gout. However, not all persons with hyperuricemia have gout. Data from NHANES 2007-2008, in which the definition of hyperuricemia was an sUA level greater than 7.0 mg/dL for men and greater than 5.7 mg/dL for women, showed the mean sUA level to be 6.1 mg/dL in men and 4.9 mg/dL in women, corresponding to hyperuricemia prevalences of 21.2% and 21.6%, respectively.1

There are several other risk factors for gout, including hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and metabolic syndrome.2 For a man with hypertension, the relative risk (RR) of gout is 2.3 compared with a normotensive man.3 Furthermore, it is well established that the use of diuretics increases the risk of gout (RR, 1.8).3 Several other medications increase sUA level as well: aspirin (including low-dose), cyclosporine, pyrazinamide, ethambutol, and niacin.2

Lifestyle and diet also pose a risk for gout. The risk of gout increases with BMI such that, compared with a man with a BMI of 21 to 22.9 kg/m2, the RR of gout is doubled for a man with a BMI of 25 to 29.9 kg/m2; for a man with a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or more, the RR is tripled.3 Sugar-sweetened soft drinks (but not diet soft drinks) and fructose-rich fruits and fruit juices also increase the risk of gout, as do a high alcohol intake, particularly beer, and a diet rich in meat (especially organ meat, turkey, or wild game) or seafood.4 A moderate intake of purine-rich vegetables (eg, peas, beans, lentils, spinach, mushrooms, oatmeal, and cauliflower) or protein is not associated with an increased risk of gout, while a high consumption of dairy products is associated with a decreased risk.5,6

Untreated or poorly treated gout usually leads to further acute attacks and progressive joint and tissue damage. In addition, gout and hyperuricemia serve as risk factors for other diseases. Adults with gout are 3 times as likely to develop metabolic syndrome as adults without gout.7 An elevated sUA level is also an independent risk factor for the development of hypertension (RR, 1.1), as well as myocardial infarction (MI; RR, 1.9), and stroke (RR, 1.6).8,9 An increasing sUA level also increases the risk of renal failure.10,11 In a study of 49,413 men followed for a mean of 5.4 years, the age-adjusted RR of renal failure was 1.5 in men with an sUA level of 6.5 to 8.4 mg/dL and 8.5 in men with an sUA level of 8.5 to 13.0 mg/dL compared with men with an sUA level of 5.0 to 6.4 mg/dL.11

Clinical Presentation

The deposition of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals in joints and tissues is very common and typically causes no signs or symptoms in the majority of persons. Even in men with an sUA level of 9 mg/dL or greater, the cumulative incidence of gouty arthritis has been found to be 22% over 5 years.12 However, as crystal deposition progresses, acute, painful attacks occur more frequently, with the development of chronic tophaceous gout after several years.13

Laboratory results for DB:

- Serum uric acid, 7.9 mg/dL

- White blood cell count, 15,800/mm3

- Serum creatinine, 1.2 mg/dL (estimated creatinine clearance, 90 mL/min)

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 23 mm/h

- Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (nonfasting), 127 mg/dL

Laboratory confirmation of hyperuricemia together with the pain, swelling, and tenderness of DB’s toe and ankle, other findings from his medical history and physical exam (eg, the use of aspirin daily), and exclusion of alternative diagnoses, such as septic arthritis, enable the family physician to arrive at a presumptive diagnosis of gouty arthritis. Aspiration of MSU crystals from DB’s toe or ankle is the gold standard and would allow for a definitive diagnosis. Although the sUA level was found to be high, it should be noted that a normal sUA level is often found during an acute attack; should this occur, the sUA level should be checked again 1 to 2 weeks after the acute attack has resolved.

Goals of Treatment

The cornerstone of gout management is daily, long-term treatment with urate-lowering therapy (ULT) combined with as-needed treatment for an acute attack. In addition, since initiation of ULT mobilizes MSU crystals, which often leads to a short-term increase in acute attacks, prophylaxis with an appropriate anti-inflammatory therapy is recommended at the time ULT is initiated.14

The therapeutic goals of gout treatment are 2-pronged: treatment of an acute gout attack and management of chronic gout. For an acute attack, the goals are to exclude a diagnosis of septic arthritis; reduce inflammation and terminate the attack; and seek, assess, and control associated diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and CVD. If this latter goal is not possible during the acute attack, plans should be made to assess associated diseases once the acute attack has resolved.14 Lowering the sUA level is not a goal of therapy for an acute attack, but it is the primary goal of ULT for chronic gout. Lowering the sUA level to less than 6.0 mg/dL, which is well below the saturation point of urate in most biological fluids, is intended to prevent further acute attacks, tophus formation, and tissue damage.14

Treatment of an Acute Attack

The mainstay of treatment for an acute attack is anti-inflammatory therapy to reduce pain and inflammation.14 Therapy should be initiated at the onset of the attack and continued until the attack is terminated, which is typically 1 to 2 weeks. Anti-inflammatory therapy traditionally has in-cluded colchicine, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), or a corticosteroid.14

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

The NSAIDs are all thought to provide similar efficacy when used in maximum doses.15,16 Since gastrointestinal toxicity is a concern with NSAIDs, coadministration of a proton pump inhibitor, H2 antagonist, or misoprostol is advised for patients with an increased risk of peptic ulcers, bleeds, or perforations.17 The risk of MI, stroke, cardiovascular death, and atrial fibrillation/flutter with NSAID therapy should be considered, especially because gout often coexists with cardiovascular disorders.15,18,19 Furthermore, NSAIDs are contraindicated in patients with heart failure or renal insufficiency.20,21

Corticosteroids. A systematic review of clinical trials involving systemic corticosteroids that found a few prospective trials of low to moderate quality concluded that there was inconclusive evidence for the efficacy and effectiveness of corticosteroids in the treatment of acute gout.22 No serious adverse events (AEs) were reported. A more recent prospective trial found comparable pain reduction and incidence of AEs with naproxen 500 mg twice daily and prednisolone 35 mg once daily for 5 days in patients with monoarticular gout.23 Furthermore, clinical experience indicates that intra-articular aspiration and injection of a long-acting corticosteroid is an effective and safe treatment for an acute attack.14,15 Corticosteroids may be useful in patients who have an inadequate response to, are intolerant of, or have a contraindication to NSAIDs and colchicine.14,15

Colchicine. Much of the recent clinical investigation regarding pharmacologic treatment of an acute gout attack has involved colchicine. To overcome the limitations of the standard dose-to-toxicity regimen of colchicine, a low-dose regimen of colchicine (1.2 mg followed by 0.6 mg 1 hour later) was investigated and subsequently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).24

Approval was based on a randomized, double-blind comparison with high-dose colchicine (1.2 mg followed by 0.6 mg every hour for 6 hours) and placebo in 184 patients with an acute gout attack.25 The primary endpoint, a 50% or greater reduction in pain at 24 hours without the use of rescue medication, was reached in 28 of 74 patients (38%) in the low-dose group, 17 of 52 patients (33%) in the high-dose group, and 9 of 58 patients (16%) in the placebo group (P = .005 and P = .034, respectively, versus placebo). An AE occurred in 36.5% and 76.9% of study participants in the low-dose and high-dose colchicine groups, respectively, and in 27.1% of participants in the placebo group. Gastrointestinal AEs (eg, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting) were less common in the low-dose colchicine group ( FIGURE ). All AEs in the low-dose group were mild to moderate in intensity, while 10 of 52 patients (19.2%) in the high-dose group had an AE of severe intensity. Concomitant use of numerous drugs can increase the concentration of colchicine. Examples include atorvastatin, fluvastatin, pravastatin, simvastatin, fibrates, gemfibrozil, digoxin, clarithromycin, erythromycin, fluconazole, itraconazole, ketoconazole, protease inhibitors, diltiazem, verapamil, and cyclosporine, as well as grapefruit juice.26

FIGURE

Frequency of selected adverse events occurring over 24 hours with low-dose vs high-dose colchicine25

Treatment plan:

TABLE

Care plan for a patient with gout27

| Acute flare | Chronic gout | |

|---|---|---|

| Goals |

|

|

| Educational points |

|

|

| sUA, serum uric acid; ULT, urate-lowering therapy. Source: Reproduced with permission. Becker MA, et al. J Fam Pract. 2010;59(6):S1-S8. Quadrant HealthCom Inc. Copyright 2010. | ||

Urate-Lowering Therapy

Urate lowering therapy is indicated for most, but not all, patients with gout. ULT is generally not recommended for those who have suffered a single attack of gout and have no complications, since 40% of these patients will not experience another attack within a year. However, should a second attack occur within a year of the first attack, ULT is recommended. Some patients who have experienced a single attack may elect to initiate ULT after being educated about the risks of the disease and the risks and benefits of ULT.14 Patients who have had an attack of gout and also have a comorbidity (eg, visible gouty tophi, renal insufficiency, uric acid stones, or use of a diuretic for hypertension) should begin ULT, since the risk of further attacks is higher in these patients, and kidney or joint damage is more likely.17

Initiation of ULT should not occur until 1 to 2 weeks after an acute attack has resolved, since beginning ULT during an acute attack is thought to prolong the attack.17 Because gout is a chronic, largely self-managed disease, patient education is a cornerstone of successful long-term treatment. Implementation of a care plan for both an acute flare and chronic gout is recommended ( TABLE ).27

Anti-inflammatory prophylaxis should begin at the same time that ULT is initiated, since an acute attack is likely due to a transient rise in the sUA level resulting from mobilization of MSU crystals. Colchicine, which is the only drug approved by the FDA for prophylaxis of an acute gout attack, can be used daily in a low-dose regimen (0.6 mg once or twice daily) for up to 6 months.17,26 Alternatively, an NSAID can be used.17

One recent investigation pooled the results of 3 phase III clinical trials of ULT in 4101 patients with gout.28 Patients received prophylaxis for 8 weeks or 6 months with low-dose colchicine 0.6 mg once daily or the combination of naproxen 250 mg twice daily with lansoprazole 15 mg once daily. The incidence of acute gout attacks increased sharply (up to 40%) at the end of 8 weeks of prophylaxis with either colchicine or naproxen and then declined steadily, whereas the rates of acute attacks were consistently low (3% to 5%) at the end of 6 months of prophylaxis with either colchicine or naproxen/lansoprazole. With the 8-week prophylaxis regimen, diarrhea was more common in the colchicine group (n = 993) than in the naproxen group (n = 829) (8.4% vs 2.7%, respectively; P < .001). With the 6-month prophylaxis regimen, liver function abnormalities (7.7% vs 4.3%; P = .023) and headache (2.8% vs 0.9%; P = .037) were more common with colchicine (n = 1807) than naproxen, while gastrointestinal/abdominal pains (3.2% vs 1.2%; P = .012) and dental/oral soft tissue infections (2.3% vs 0.6%; P = .006) were more common with naproxen (n = 346) than colchicine.

Uricostatic Agents

Uricostatic therapy with a xanthine oxidase inhibitor (ie, allopurinol or febuxostat) is the most commonly used ULT. Allopurinol is effective in lowering the sUA level and has been shown to lower the rates of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events, and, in patients with chronic kidney disease, slow the progression of renal disease.29,30 One key point that must be kept in mind is that the efficacy of allopurinol to lower the sUA level is dose-dependent, although limited safety data are available for doses >300 mg per day.14,31,32 One recent prospective clinical trial showed that 26% of patients achieved an sUA level of 5 mg/dL or less following 2 months of treatment with allopurinol 300 mg per day compared with 78% of those who subsequently doubled the dose to 300 mg twice daily.31 Two patients discontinued treatment with allopurinol because of an AE. Finally, the dose of allopurinol must be adjusted based on renal function to minimize the risk of AEs, particularly skin rashes.33

Febuxostat is also effective in lowering the sUA level. In patients with an sUA level of 8.0 mg/dL or higher and a creatinine clearance of 50 mL/min or higher at baseline, an sUA level of less than 6.0 mg/dL was achieved in 53% of patients treated with febuxostat 80 mg (n = 256) versus 21% of patients treated with allopurinol 300 mg once daily (n = 253) after 1 year (P < .001).34 The most frequent treatment-related AE was liver function abnormality, which occurred in 4% of patients in each group. Results of a 6-month trial showed that achievement of an sUA level of less than 6.0 mg/dL was achieved in 45% and 67% of patients treated with febuxostat 40 mg or 80 mg daily, respectively, and 42% of those treated with allopurinol 300 mg (200 mg in moderate renal impairment) daily.35 Febuxostat also has been shown to slow the progression of, or even stabilize, renal function.36

Treatment plan (continued):

- For an acute gout attack: Continue colchicine as needed

- ULT: Initiate allopurinol 100 mg once daily; increase to 200 mg once daily in 1 week, and 300 mg once daily in another week

- -Alternatively, initiate febuxostat 40 mg once daily; increase to 80 mg once daily if an sUA level of less than 6.0 mg/dL is not achieved within 2 weeks

- For prophylaxis of an acute attack when initiating ULT: Initiate colchicine 0.6 mg once daily; may increase to 0.6 mg twice daily if needed

- -Alternatively, initiate naproxen 250 mg twice daily with a proton pump inhibitor

- Measure sUA in 1 month; if the sUA level is greater than 6.0 mg/dL, increase allopurinol to 200 mg twice daily

- -Measure sUA in 1 month; if the sUA level is still greater than 6.0 mg/dL, increase allopurinol to 300 mg twice daily

- Implement the care plan ( TABLE )27

- -Inquire about and address issues to promote adherence and self-management

- -Discuss the most common AEs with allopurinol and colchicine and the actions the patient should take if an AE occurs

- Once the sUA level is 6.0 mg/dL or less, monitor sUA annually (including serum creatinine)14

Managing the Multiple Symptoms of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia — CME

Managing Type 2 Diabetes in Men

Meeting New Challenges with Antiplatelet Therapy in Primary Care

Dr. Ruoff has disclosed that he is on the speakers’ bureau for and has received research grants from Takeda Pharmaceuticals.

SUPPORT

This program is sponsored by the PCEC and is supported by funding from URL Pharma, Inc.

DB is a 50-year-old obese male visiting the clinic for symptoms suggestive of allergic rhinitis. The nurse has informed the family physician that DB was limping from the waiting room to the examination room. DB reports that he has been experiencing pain in his left big toe and ankle over the past few days. The last time this happened, the pain resolved within 7 to 10 days.

DB reports that he has experienced 4 or 5 similar episodes over the past 3 years. The first attacks affected his left big toe, but he now also experiences some pain in his left ankle. The pain is moderate, peaks in 1 to 2 days, and resolves within 7 to 10 days. Acetaminophen provided little pain relief so DB now takes ibuprofen 400 mg 3 times daily, as it “helps take the edge off.” Other medications include aspirin 81 mg per day and an oral antihistamine as needed for hay fever. DB reports that he eats seafood 2 to 3 times per week and red meat 1 to 2 times per week; he drinks 2 six-packs of beer per week.

Physical examination: weight, 186 lb (body mass index [BMI], 27 kg/m2); blood pressure, 126/76 mm Hg; and temperature, 98.8°F. His left big toe and ankle are red, slightly swollen, and warm with a small subcutaneous nodule noted on the first metatarsophalangeal joint. There is no sign of skin or joint infection.

The impression from his history and physical exam is that DB is suffering from an acute attack of gout, but the family physician also considers other diagnoses.

Background

Gout is a heterogeneous disorder that peaks in incidence in the fifth decade. Gout is caused by hyperuricemia, generally as a result of reduced excretion of uric acid by the kidneys; hyperuricemia may also result from overproduction of uric acid. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007-2008 indicate that the prevalence of gout continues to rise in the United States, likely related to the increasing frequency of adiposity and hypertension. Overall, about 75% of the 8.3 million people with gout are men.1

Risk Factors

Clinically defined hyperuricemia—a serum urate (sUA) level greater than 6.8 mg/dL, the concentration at which urate exceeds its solubility in most biological fluids—is the major risk factor for gout. However, not all persons with hyperuricemia have gout. Data from NHANES 2007-2008, in which the definition of hyperuricemia was an sUA level greater than 7.0 mg/dL for men and greater than 5.7 mg/dL for women, showed the mean sUA level to be 6.1 mg/dL in men and 4.9 mg/dL in women, corresponding to hyperuricemia prevalences of 21.2% and 21.6%, respectively.1

There are several other risk factors for gout, including hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and metabolic syndrome.2 For a man with hypertension, the relative risk (RR) of gout is 2.3 compared with a normotensive man.3 Furthermore, it is well established that the use of diuretics increases the risk of gout (RR, 1.8).3 Several other medications increase sUA level as well: aspirin (including low-dose), cyclosporine, pyrazinamide, ethambutol, and niacin.2

Lifestyle and diet also pose a risk for gout. The risk of gout increases with BMI such that, compared with a man with a BMI of 21 to 22.9 kg/m2, the RR of gout is doubled for a man with a BMI of 25 to 29.9 kg/m2; for a man with a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or more, the RR is tripled.3 Sugar-sweetened soft drinks (but not diet soft drinks) and fructose-rich fruits and fruit juices also increase the risk of gout, as do a high alcohol intake, particularly beer, and a diet rich in meat (especially organ meat, turkey, or wild game) or seafood.4 A moderate intake of purine-rich vegetables (eg, peas, beans, lentils, spinach, mushrooms, oatmeal, and cauliflower) or protein is not associated with an increased risk of gout, while a high consumption of dairy products is associated with a decreased risk.5,6

Untreated or poorly treated gout usually leads to further acute attacks and progressive joint and tissue damage. In addition, gout and hyperuricemia serve as risk factors for other diseases. Adults with gout are 3 times as likely to develop metabolic syndrome as adults without gout.7 An elevated sUA level is also an independent risk factor for the development of hypertension (RR, 1.1), as well as myocardial infarction (MI; RR, 1.9), and stroke (RR, 1.6).8,9 An increasing sUA level also increases the risk of renal failure.10,11 In a study of 49,413 men followed for a mean of 5.4 years, the age-adjusted RR of renal failure was 1.5 in men with an sUA level of 6.5 to 8.4 mg/dL and 8.5 in men with an sUA level of 8.5 to 13.0 mg/dL compared with men with an sUA level of 5.0 to 6.4 mg/dL.11

Clinical Presentation

The deposition of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals in joints and tissues is very common and typically causes no signs or symptoms in the majority of persons. Even in men with an sUA level of 9 mg/dL or greater, the cumulative incidence of gouty arthritis has been found to be 22% over 5 years.12 However, as crystal deposition progresses, acute, painful attacks occur more frequently, with the development of chronic tophaceous gout after several years.13

Laboratory results for DB:

- Serum uric acid, 7.9 mg/dL

- White blood cell count, 15,800/mm3

- Serum creatinine, 1.2 mg/dL (estimated creatinine clearance, 90 mL/min)

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 23 mm/h

- Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (nonfasting), 127 mg/dL

Laboratory confirmation of hyperuricemia together with the pain, swelling, and tenderness of DB’s toe and ankle, other findings from his medical history and physical exam (eg, the use of aspirin daily), and exclusion of alternative diagnoses, such as septic arthritis, enable the family physician to arrive at a presumptive diagnosis of gouty arthritis. Aspiration of MSU crystals from DB’s toe or ankle is the gold standard and would allow for a definitive diagnosis. Although the sUA level was found to be high, it should be noted that a normal sUA level is often found during an acute attack; should this occur, the sUA level should be checked again 1 to 2 weeks after the acute attack has resolved.

Goals of Treatment

The cornerstone of gout management is daily, long-term treatment with urate-lowering therapy (ULT) combined with as-needed treatment for an acute attack. In addition, since initiation of ULT mobilizes MSU crystals, which often leads to a short-term increase in acute attacks, prophylaxis with an appropriate anti-inflammatory therapy is recommended at the time ULT is initiated.14

The therapeutic goals of gout treatment are 2-pronged: treatment of an acute gout attack and management of chronic gout. For an acute attack, the goals are to exclude a diagnosis of septic arthritis; reduce inflammation and terminate the attack; and seek, assess, and control associated diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and CVD. If this latter goal is not possible during the acute attack, plans should be made to assess associated diseases once the acute attack has resolved.14 Lowering the sUA level is not a goal of therapy for an acute attack, but it is the primary goal of ULT for chronic gout. Lowering the sUA level to less than 6.0 mg/dL, which is well below the saturation point of urate in most biological fluids, is intended to prevent further acute attacks, tophus formation, and tissue damage.14

Treatment of an Acute Attack

The mainstay of treatment for an acute attack is anti-inflammatory therapy to reduce pain and inflammation.14 Therapy should be initiated at the onset of the attack and continued until the attack is terminated, which is typically 1 to 2 weeks. Anti-inflammatory therapy traditionally has in-cluded colchicine, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), or a corticosteroid.14

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

The NSAIDs are all thought to provide similar efficacy when used in maximum doses.15,16 Since gastrointestinal toxicity is a concern with NSAIDs, coadministration of a proton pump inhibitor, H2 antagonist, or misoprostol is advised for patients with an increased risk of peptic ulcers, bleeds, or perforations.17 The risk of MI, stroke, cardiovascular death, and atrial fibrillation/flutter with NSAID therapy should be considered, especially because gout often coexists with cardiovascular disorders.15,18,19 Furthermore, NSAIDs are contraindicated in patients with heart failure or renal insufficiency.20,21

Corticosteroids. A systematic review of clinical trials involving systemic corticosteroids that found a few prospective trials of low to moderate quality concluded that there was inconclusive evidence for the efficacy and effectiveness of corticosteroids in the treatment of acute gout.22 No serious adverse events (AEs) were reported. A more recent prospective trial found comparable pain reduction and incidence of AEs with naproxen 500 mg twice daily and prednisolone 35 mg once daily for 5 days in patients with monoarticular gout.23 Furthermore, clinical experience indicates that intra-articular aspiration and injection of a long-acting corticosteroid is an effective and safe treatment for an acute attack.14,15 Corticosteroids may be useful in patients who have an inadequate response to, are intolerant of, or have a contraindication to NSAIDs and colchicine.14,15

Colchicine. Much of the recent clinical investigation regarding pharmacologic treatment of an acute gout attack has involved colchicine. To overcome the limitations of the standard dose-to-toxicity regimen of colchicine, a low-dose regimen of colchicine (1.2 mg followed by 0.6 mg 1 hour later) was investigated and subsequently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).24

Approval was based on a randomized, double-blind comparison with high-dose colchicine (1.2 mg followed by 0.6 mg every hour for 6 hours) and placebo in 184 patients with an acute gout attack.25 The primary endpoint, a 50% or greater reduction in pain at 24 hours without the use of rescue medication, was reached in 28 of 74 patients (38%) in the low-dose group, 17 of 52 patients (33%) in the high-dose group, and 9 of 58 patients (16%) in the placebo group (P = .005 and P = .034, respectively, versus placebo). An AE occurred in 36.5% and 76.9% of study participants in the low-dose and high-dose colchicine groups, respectively, and in 27.1% of participants in the placebo group. Gastrointestinal AEs (eg, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting) were less common in the low-dose colchicine group ( FIGURE ). All AEs in the low-dose group were mild to moderate in intensity, while 10 of 52 patients (19.2%) in the high-dose group had an AE of severe intensity. Concomitant use of numerous drugs can increase the concentration of colchicine. Examples include atorvastatin, fluvastatin, pravastatin, simvastatin, fibrates, gemfibrozil, digoxin, clarithromycin, erythromycin, fluconazole, itraconazole, ketoconazole, protease inhibitors, diltiazem, verapamil, and cyclosporine, as well as grapefruit juice.26

FIGURE

Frequency of selected adverse events occurring over 24 hours with low-dose vs high-dose colchicine25

Treatment plan:

TABLE

Care plan for a patient with gout27

| Acute flare | Chronic gout | |

|---|---|---|

| Goals |

|

|

| Educational points |

|

|

| sUA, serum uric acid; ULT, urate-lowering therapy. Source: Reproduced with permission. Becker MA, et al. J Fam Pract. 2010;59(6):S1-S8. Quadrant HealthCom Inc. Copyright 2010. | ||

Urate-Lowering Therapy

Urate lowering therapy is indicated for most, but not all, patients with gout. ULT is generally not recommended for those who have suffered a single attack of gout and have no complications, since 40% of these patients will not experience another attack within a year. However, should a second attack occur within a year of the first attack, ULT is recommended. Some patients who have experienced a single attack may elect to initiate ULT after being educated about the risks of the disease and the risks and benefits of ULT.14 Patients who have had an attack of gout and also have a comorbidity (eg, visible gouty tophi, renal insufficiency, uric acid stones, or use of a diuretic for hypertension) should begin ULT, since the risk of further attacks is higher in these patients, and kidney or joint damage is more likely.17

Initiation of ULT should not occur until 1 to 2 weeks after an acute attack has resolved, since beginning ULT during an acute attack is thought to prolong the attack.17 Because gout is a chronic, largely self-managed disease, patient education is a cornerstone of successful long-term treatment. Implementation of a care plan for both an acute flare and chronic gout is recommended ( TABLE ).27

Anti-inflammatory prophylaxis should begin at the same time that ULT is initiated, since an acute attack is likely due to a transient rise in the sUA level resulting from mobilization of MSU crystals. Colchicine, which is the only drug approved by the FDA for prophylaxis of an acute gout attack, can be used daily in a low-dose regimen (0.6 mg once or twice daily) for up to 6 months.17,26 Alternatively, an NSAID can be used.17

One recent investigation pooled the results of 3 phase III clinical trials of ULT in 4101 patients with gout.28 Patients received prophylaxis for 8 weeks or 6 months with low-dose colchicine 0.6 mg once daily or the combination of naproxen 250 mg twice daily with lansoprazole 15 mg once daily. The incidence of acute gout attacks increased sharply (up to 40%) at the end of 8 weeks of prophylaxis with either colchicine or naproxen and then declined steadily, whereas the rates of acute attacks were consistently low (3% to 5%) at the end of 6 months of prophylaxis with either colchicine or naproxen/lansoprazole. With the 8-week prophylaxis regimen, diarrhea was more common in the colchicine group (n = 993) than in the naproxen group (n = 829) (8.4% vs 2.7%, respectively; P < .001). With the 6-month prophylaxis regimen, liver function abnormalities (7.7% vs 4.3%; P = .023) and headache (2.8% vs 0.9%; P = .037) were more common with colchicine (n = 1807) than naproxen, while gastrointestinal/abdominal pains (3.2% vs 1.2%; P = .012) and dental/oral soft tissue infections (2.3% vs 0.6%; P = .006) were more common with naproxen (n = 346) than colchicine.

Uricostatic Agents

Uricostatic therapy with a xanthine oxidase inhibitor (ie, allopurinol or febuxostat) is the most commonly used ULT. Allopurinol is effective in lowering the sUA level and has been shown to lower the rates of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events, and, in patients with chronic kidney disease, slow the progression of renal disease.29,30 One key point that must be kept in mind is that the efficacy of allopurinol to lower the sUA level is dose-dependent, although limited safety data are available for doses >300 mg per day.14,31,32 One recent prospective clinical trial showed that 26% of patients achieved an sUA level of 5 mg/dL or less following 2 months of treatment with allopurinol 300 mg per day compared with 78% of those who subsequently doubled the dose to 300 mg twice daily.31 Two patients discontinued treatment with allopurinol because of an AE. Finally, the dose of allopurinol must be adjusted based on renal function to minimize the risk of AEs, particularly skin rashes.33

Febuxostat is also effective in lowering the sUA level. In patients with an sUA level of 8.0 mg/dL or higher and a creatinine clearance of 50 mL/min or higher at baseline, an sUA level of less than 6.0 mg/dL was achieved in 53% of patients treated with febuxostat 80 mg (n = 256) versus 21% of patients treated with allopurinol 300 mg once daily (n = 253) after 1 year (P < .001).34 The most frequent treatment-related AE was liver function abnormality, which occurred in 4% of patients in each group. Results of a 6-month trial showed that achievement of an sUA level of less than 6.0 mg/dL was achieved in 45% and 67% of patients treated with febuxostat 40 mg or 80 mg daily, respectively, and 42% of those treated with allopurinol 300 mg (200 mg in moderate renal impairment) daily.35 Febuxostat also has been shown to slow the progression of, or even stabilize, renal function.36

Treatment plan (continued):

- For an acute gout attack: Continue colchicine as needed

- ULT: Initiate allopurinol 100 mg once daily; increase to 200 mg once daily in 1 week, and 300 mg once daily in another week

- -Alternatively, initiate febuxostat 40 mg once daily; increase to 80 mg once daily if an sUA level of less than 6.0 mg/dL is not achieved within 2 weeks

- For prophylaxis of an acute attack when initiating ULT: Initiate colchicine 0.6 mg once daily; may increase to 0.6 mg twice daily if needed

- -Alternatively, initiate naproxen 250 mg twice daily with a proton pump inhibitor

- Measure sUA in 1 month; if the sUA level is greater than 6.0 mg/dL, increase allopurinol to 200 mg twice daily

- -Measure sUA in 1 month; if the sUA level is still greater than 6.0 mg/dL, increase allopurinol to 300 mg twice daily

- Implement the care plan ( TABLE )27

- -Inquire about and address issues to promote adherence and self-management

- -Discuss the most common AEs with allopurinol and colchicine and the actions the patient should take if an AE occurs

- Once the sUA level is 6.0 mg/dL or less, monitor sUA annually (including serum creatinine)14

1. Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK. Prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007-2008. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(10):3136-3141.

2. Weaver AL. Epidemiology of gout. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75(suppl 5):S9-S12.

3. Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Curhan G. Obesity, weight change, hypertension, diuretic use, and risk of gout in men: the health professionals follow-up study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(7):742-748.

4. Choi HK, Curhan G. Soft drinks, fructose consumption, and the risk of gout in men: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336(7639):309-312.

5. Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Willett W, Curhan G. Purine-rich foods, dairy and protein intake, and the risk of gout in men. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(11):1093-1103.

6. Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Willett W, Curhan G. Alcohol intake and risk of incident gout in men: a prospective study. Lancet. 2004;363(9417):1277-1281.

7. Choi HK, Ford ES, Li C, Curhan G. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with gout: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(1):109-115.

8. Perlstein TS, Gumieniak O, Williams GH, et al. Uric acid and the development of hypertension: the normative aging study. Hypertension. 2006;48(6):1031-1036.

9. Bos MJ, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, Witteman JC, Breteler MM. Uric acid is a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke: the Rotterdam study. Stroke. 2006;37(6):1503-1507.

10. Iseki K, Ikemiya Y, Inoue T, Iseki C, Kinjo K, Takishita S. Significance of hyperuricemia as a risk factor for developing ESRD in a screened cohort. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44(4):642-650.

11. Tomita M, Mizuno S, Yamanaka H, et al. Does hyperuricemia affect mortality? A prospective cohort study of Japanese male workers. J Epidemiol. 2000;10(6):403-409.

12. Campion EW, Glynn RJ, DeLabry LO. Asymptomatic hyperuricemia. Risks and consequences in the Normative Aging Study. Am J Med. 1987;82(3):421-426.

13. Mandell BF. Clinical manifestations of hyperuricemia and gout. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75(Suppl 5):S5-S8.

14. Hamburger M, Baraf HS, Adamson TC III, et al. 2011 Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of gout and hyperuricemia. Postgrad Med. 2011;123 (6 suppl 1):3-36.

15. Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T, et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part II: Management. Report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(10):1312-1324.

16. Schumacher HR Jr, Boice JA, Daikh DI, et al. Randomised double blind trial of etoricoxib and indometacin in treatment of acute gouty arthritis. BMJ. 2002;324(7352):1488-1492.

17. Jordan KM, Cameron JS, Snaith M, et al. British Society for Rheumatology and British Health Professionals in Rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46(8):1372-1374.

18. Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S, et al. Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:c7086.-

19. Schmidt M, Christiansen CF, Mehnert F, Rothman KJ, Sorensen HT. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and risk of atrial fibrillation or flutter: population based case-control study. BMJ. 2011;343:d3450.-

20. NSAIDS and chronic kidney disease. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/news/docs/nsaid_video.htm. Published 2012. Accessed April 22, 2012.

21. Gislason GH, Rasmussen JN, Abildstrom SZ, et al. Increased mortality and cardiovascular morbidity associated with use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in chronic heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(2):141-149.

22. Janssens HJ, Lucassen PL, Van de Laar FA, Janssen M, Van de Lisdonk EH. Systemic corticosteroids for acute gout. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD005521.-

23. Janssens HJ, Janssen M, van de Lisdonk EH, van Riel PL, van Weel C. Use of oral prednisolone or naproxen for the treatment of gout arthritis: a double-blind, randomised equivalence trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9627):1854-1860.

24. Schlesinger N, Schumacher R, Catton M, Maxwell L. Colchicine for acute gout. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD006190.-

25. Terkeltaub RA, Furst DE, Bennett K, Kook KA, Crockett RS, Davis MW. High versus low dosing of oral colchicine for early acute gout flare: Twenty-four-hour outcome of the first multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, dose-comparison colchicine study. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(4):1060-1068.

26. Colcrys [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: AR Scientific, Inc.; 2011.

27. Becker MA, Ruoff GE. What do I need to know about gout? J Fam Pract. 2010;59(6 suppl):S1-S8.

28. Wortmann RL, Macdonald PA, Hunt B, Jackson RL. Effect of prophylaxis on gout flares after the initiation of urate-lowering therapy: analysis of data from three phase III trials. Clin Ther. 2010;32(14):2386-2397.

29. Luk AJ, Levin GP, Moore EE, Zhou XH, Kestenbaum BR, Choi HK. Allopurinol and mortality in hyperuricaemic patients. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48(7):804-806.

30. Goicoechea M, de Vinuesa SG, Verdalles U, et al. Effect of allopurinol in chronic kidney disease progression and cardiovascular risk. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(8):1388-1393.

31. Reinders MK, Haagsma C, Jansen TL, et al. A randomised controlled trial on the efficacy and tolerability with dose escalation of allopurinol 300-600 mg/day versus benzbromarone 100-200 mg/day in patients with gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(6):892-897.

32. Stamp LK, O’Donnell JL, Zhang M, et al. Using allopurinol above the dose based on creatinine clearance is effective and safe in patients with chronic gout, including those with renal impairment. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(2):412-421.

33. Zyloprim [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Prometheus Laboratories Inc.; 2003.

34. Becker MA, Schumacher HR Jr, Wortmann RL, et al. Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2450-2461.

35. Becker MA, Schumacher HR, Espinoza LR, et al. The urate-lowering efficacy and safety of febuxostat in the treatment of the hyperuricemia of gout: the CONFIRMS trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:doi:10.1186/ar2978.

36. Whelton A, Macdonald PA, Zhao L, Hunt B, Gunawardhana L. Renal function in gout: long-term treatment effects of febuxostat. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17(1):7-13.

1. Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK. Prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007-2008. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(10):3136-3141.

2. Weaver AL. Epidemiology of gout. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75(suppl 5):S9-S12.

3. Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Curhan G. Obesity, weight change, hypertension, diuretic use, and risk of gout in men: the health professionals follow-up study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(7):742-748.

4. Choi HK, Curhan G. Soft drinks, fructose consumption, and the risk of gout in men: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336(7639):309-312.

5. Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Willett W, Curhan G. Purine-rich foods, dairy and protein intake, and the risk of gout in men. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(11):1093-1103.

6. Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Willett W, Curhan G. Alcohol intake and risk of incident gout in men: a prospective study. Lancet. 2004;363(9417):1277-1281.

7. Choi HK, Ford ES, Li C, Curhan G. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with gout: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(1):109-115.

8. Perlstein TS, Gumieniak O, Williams GH, et al. Uric acid and the development of hypertension: the normative aging study. Hypertension. 2006;48(6):1031-1036.

9. Bos MJ, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, Witteman JC, Breteler MM. Uric acid is a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke: the Rotterdam study. Stroke. 2006;37(6):1503-1507.

10. Iseki K, Ikemiya Y, Inoue T, Iseki C, Kinjo K, Takishita S. Significance of hyperuricemia as a risk factor for developing ESRD in a screened cohort. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44(4):642-650.

11. Tomita M, Mizuno S, Yamanaka H, et al. Does hyperuricemia affect mortality? A prospective cohort study of Japanese male workers. J Epidemiol. 2000;10(6):403-409.

12. Campion EW, Glynn RJ, DeLabry LO. Asymptomatic hyperuricemia. Risks and consequences in the Normative Aging Study. Am J Med. 1987;82(3):421-426.

13. Mandell BF. Clinical manifestations of hyperuricemia and gout. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75(Suppl 5):S5-S8.

14. Hamburger M, Baraf HS, Adamson TC III, et al. 2011 Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of gout and hyperuricemia. Postgrad Med. 2011;123 (6 suppl 1):3-36.

15. Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T, et al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part II: Management. Report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(10):1312-1324.

16. Schumacher HR Jr, Boice JA, Daikh DI, et al. Randomised double blind trial of etoricoxib and indometacin in treatment of acute gouty arthritis. BMJ. 2002;324(7352):1488-1492.

17. Jordan KM, Cameron JS, Snaith M, et al. British Society for Rheumatology and British Health Professionals in Rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46(8):1372-1374.

18. Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S, et al. Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:c7086.-

19. Schmidt M, Christiansen CF, Mehnert F, Rothman KJ, Sorensen HT. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and risk of atrial fibrillation or flutter: population based case-control study. BMJ. 2011;343:d3450.-

20. NSAIDS and chronic kidney disease. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/news/docs/nsaid_video.htm. Published 2012. Accessed April 22, 2012.

21. Gislason GH, Rasmussen JN, Abildstrom SZ, et al. Increased mortality and cardiovascular morbidity associated with use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in chronic heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(2):141-149.

22. Janssens HJ, Lucassen PL, Van de Laar FA, Janssen M, Van de Lisdonk EH. Systemic corticosteroids for acute gout. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD005521.-

23. Janssens HJ, Janssen M, van de Lisdonk EH, van Riel PL, van Weel C. Use of oral prednisolone or naproxen for the treatment of gout arthritis: a double-blind, randomised equivalence trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9627):1854-1860.

24. Schlesinger N, Schumacher R, Catton M, Maxwell L. Colchicine for acute gout. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD006190.-

25. Terkeltaub RA, Furst DE, Bennett K, Kook KA, Crockett RS, Davis MW. High versus low dosing of oral colchicine for early acute gout flare: Twenty-four-hour outcome of the first multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, dose-comparison colchicine study. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(4):1060-1068.

26. Colcrys [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: AR Scientific, Inc.; 2011.

27. Becker MA, Ruoff GE. What do I need to know about gout? J Fam Pract. 2010;59(6 suppl):S1-S8.

28. Wortmann RL, Macdonald PA, Hunt B, Jackson RL. Effect of prophylaxis on gout flares after the initiation of urate-lowering therapy: analysis of data from three phase III trials. Clin Ther. 2010;32(14):2386-2397.

29. Luk AJ, Levin GP, Moore EE, Zhou XH, Kestenbaum BR, Choi HK. Allopurinol and mortality in hyperuricaemic patients. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48(7):804-806.

30. Goicoechea M, de Vinuesa SG, Verdalles U, et al. Effect of allopurinol in chronic kidney disease progression and cardiovascular risk. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(8):1388-1393.

31. Reinders MK, Haagsma C, Jansen TL, et al. A randomised controlled trial on the efficacy and tolerability with dose escalation of allopurinol 300-600 mg/day versus benzbromarone 100-200 mg/day in patients with gout. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(6):892-897.

32. Stamp LK, O’Donnell JL, Zhang M, et al. Using allopurinol above the dose based on creatinine clearance is effective and safe in patients with chronic gout, including those with renal impairment. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(2):412-421.

33. Zyloprim [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Prometheus Laboratories Inc.; 2003.

34. Becker MA, Schumacher HR Jr, Wortmann RL, et al. Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2450-2461.

35. Becker MA, Schumacher HR, Espinoza LR, et al. The urate-lowering efficacy and safety of febuxostat in the treatment of the hyperuricemia of gout: the CONFIRMS trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:doi:10.1186/ar2978.

36. Whelton A, Macdonald PA, Zhao L, Hunt B, Gunawardhana L. Renal function in gout: long-term treatment effects of febuxostat. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17(1):7-13.

A method that dramatically improves patient adherence to depression treatment

- Discuss with patients the need to continue medication for the prescribed period, to help ensure treatment success.

- Be open about possible side effects of the drug you prescribe, and assure the patient that a change in medication can be made if the initial choice proves intolerable.

- Consider using a treatment flow sheet as a means of tracking the patient’s course and as a prompt for regular communication with the patient.

- This study focused on increasing patient adherence to a prescribed medical regimen for depression or depressive symptoms. The goal was to demonstrate that a depression flow sheet supported by physician instruction, patient education, and diligent follow-up could enable depressed patients to better adhere to treatment. The study documented reduction in depression severity over time. In addition to depression data, sample characteristics of comorbid disorders were obtained.

- Methods: Patients tentatively diagnosed with depression were asked to complete a self-administered 9-item diagnostic survey (PHQ-9) to confirm the severity of depressive symptoms. Physicians in the practice then implemented a flow sheet to record pertinent data including comorbidities. All data were kept in patients’ medical charts. A second PHQ-9 survey was completed by patients after at least 4 weeks. A total of 103 subjects was analyzed during 2003–2004. Subsequently, patient charts were systematically audited throughout the study period to record adherence, reasons for nonadherence (if any), PHQ-9 survey results, and comorbidities.

- Results: Patient adherence improved to a significantly greater extent among patients in our study compared with existing national research data on depression.

- Conclusions: Use of a flow sheet, coupled with patient education and diligent follow-up, dramatically improved the rate of medication adherence in patients who initially presented with depressive symptoms—with or without comorbidities. A clinician or small group can adapt the PHQ-9 materials with modest effort and positively impact the care of their patients, including adherence to medication regimens.

Even when depression is properly diagnosed and treatment is prescribed, the rate of patient adherence to regimens can drop to as low as 33% within the first 3 months of therapy1—far short of the universally recommended 4 to 9 months of treatment (see Minimum duration of treatment). The rate is even lower when lifestyle and other more behaviorally demanding regimens are instituted.9

This study demonstrated that use of a management flow sheet, in conjunction with suitable instructions to physicians and education of patients, overcame the usual causes of discontinuance and enabled far more patients to adhere to a prescribed medical regimen than is reported by other current research, ultimately alleviating depressive symptoms regardless of cause.

To prevent relapse, the National Institute of Mental Health, the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, and the American Psychiatric Association consistently recommend continual treatment with antidepressants for at least 4 to 9 months after depression symptoms resolve2-5—a period of time considered crucial in obtaining a successful clinical outcome.6 Other guidelines establish 9 months as the minimum for a treatment regimen.7 Those high risk patients whose depression is recurrent, or whose symptoms are slow to resolve, or are refractory to traditional treatment regimens, may require more than 2 years of long-term maintenance therapy.8

Methods

Setting

The study was conducted during 2003 to 2004 in a private suburban/urban family medicine group in the Midwestern United States. Fifteen family physicians practice in the group, which cares for about 55,000 patients, most of whom are insured.

Subjects

One-hundred three patients at the clinic were newly diagnosed with varying degrees of depression by 3 doctors in the practice. All were included in the study.

Diagnoses were confirmed by patient history, physical examination, interview, and responses to a 9-item diagnostic survey (Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ-9]—APPENDIX 1, available online at www.jfponline.com, and in our February 2003 issue [J Fam Pract 2003; 52:126]). The survey has a sensitivity of 73% and a specificity of 98% when compared with a Structured Clinical Interview administered by a mental health clinician.10,11

No exclusion criteria were applied. Subjects were included regardless of age, gender, race, severity of depression, associated medical conditions, or insurance status. No patients refused to participate. However, of the 103 enrolled patients, 1 was later imprisoned, 2 died, and 3 transferred from the practice. Of the remaining 97, 36 were identified too late in the study to meet the 9-month protocol at the time of final analysis. Therefore, though their comorbidity and depression level data are included in this research, final conclusions relative to “measurement of adherence” were not.

The database for this study, therefore, is 97 subjects for whom data were secured, and 61 for whom adherence or nonadherence was measured. The practice continues to monitor all enrolled patients, and other enrollees for the purposes described in this project.

Experimental design