User login

Fetal thrombophilia, perinatal stroke, and novel ideas about CP

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Thrombosis is hypothesized to be the more common mechanism underlying cerebral palsy in many cases of maternal or fetal thrombophilia; for that reason, understanding the impact of maternal and fetal thrombophilia on pregnancy outcome is of paramount importance when counseling patients.

Is a maternal and fetal thrombophilia work-up needed in women who give birth to a term infant with cerebral palsy? Prospective studies are needed to evaluate whether that is the case. In this article, we review the literature on fetal thrombophilia and its role in explaining some cases of perinatal stroke that lead, ultimately, to cerebral palsy.

The several causes of cerebral palsy

Cerebral palsy is the most common chronic motor disability of childhood. Approximately 2 to 2.5 of every 1,000 children are given a diagnosis of this disorder every year.1,2 The condition appears early in life; it is not the result of recognized progressive disease.1 Risk factors for cerebral palsy are multiple and heterogenous1,3,4-6:

- Prematurity. The risk of developing cerebral palsy correlates inversely with gestational age.7,8 A premature infant who weighs less than 1,500 g at birth has a risk of cerebral palsy that is 20 to 30 times greater than that of a full-term, normal-weight newborn.3,4

- Hypoxia and ischemia. These are the conditions most often implicated as the cause of cerebral palsy. Fetal heart-rate monitoring was introduced in the 1960s in the hope that interventions to prevent hypoxia and ischemia would reduce the incidence of cerebral palsy. But monitoring has not had that effect—most likely, because some cases of cerebral palsy are caused by perinatal stroke.9 In fact, a large, population-based study has demonstrated that potentially asphyxiating obstetrical conditions account for only about 6% of cases of cerebral palsy.6

- Thrombophilia. Several recent studies report an association between fetal thrombophilia and both neonatal stroke and cerebral palsy.10-14 That association provides a possible explanation for adverse pregnancy outcomes that have otherwise been ascribed to events during delivery.15-23 Although thrombophilia is a recognized risk factor for cerebral palsy, the strength of the association has still not been fully investigated. TABLE 1 and TABLE 2 summarize studies that have examined this association. Given the rarity of both inherited thrombophilias and cerebral palsy, however, an enormous number of cases would be required to fully establish a causal relationship.

TABLE 1

Case reports reveal an association

between fetal thrombophilias and cerebral palsy

| Thrombophilias present | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study (type) | Cases of CP | Number | Type |

| Harum et al36 (case report) | 1 | 1 | Factor V Leiden |

| Thorarensen et al37 (case report) | 3 | 3 | Factor V Leiden |

| Lynch et al2 (case series) | 8 | 8 | Factor V Leiden |

| Halliday et al38 (case series) | 55 | 5 | Factor V Leiden; prothrombin mutation |

| Smith et al39 (case series) | 38 | 7 | Factor VIIIc |

| Nelson et al40 (case series) | 31 | 20 | Factor V Leiden; protein C deficiency |

TABLE 2

How often is a fetal thrombophilia

the likely underlying cause of cerebral palsy?

| Thrombophilia* | Prevalence of CP† | Odds ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Factor V Leiden | 6.3% | 0.62 (0.37–1.05) |

| Prothrombin gene | 5.2% | 1.11 (0.59–2.06) |

| MTHFR 677 | 54.1% | 1.27 (0.97–1.66) |

| MTHFR 1298 | 39.4% | 1.08 (0.69–1.19) |

| MTHFR 677/1298 | 15.1% | 1.18 (0.82–1.69) |

| * Heterozygous or homozygous | ||

| † Among 354 subjects with thrombophilia studied41 | ||

| Key: MTHFR, methyltetrahydrofolate reductase | ||

“Thrombophilia” describes a spectrum of congenital or acquired coagulation disorders associated with venous and arterial thrombosis.24 These disorders can occur in the mother or in the fetus, or in both concomitantly.

Fetal thrombophilia has a reported incidence of 2.4 to 5.1 cases for every 100,000 births.25 Whereas maternal thrombophilia has a substantially higher incidence, both maternal and fetal thrombophilia can lead to adverse maternal and fetal events.

The incidence of specific inherited fetal thrombophilias is summarized in TABLE 3. Maternal thrombophilia is generally associated with various adverse pregnancy outcomes, particularly cerebral palsy and perinatal stroke.9,26

TABLE 3

Inherited thrombophilias among the general population

| Study | Number | Factor V Leiden | Protein gene mutation | MTHFR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gibson et al41 (2003) | 708 | 9.8% | 4.7% | 15.1%* |

| Dizon-Townson et al42 (2005) | 4,033 | 3.0% | Not reported | Not reported |

| Infante-Rivard et al43 (2002) | 472 | 3.3% | 1.3% | 43% to 49% |

| Stanley-Christian et al44 (2005) | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Currie et al45 (2002) | 46 | 13.0% | Not reported | Not reported |

| Livingston et al46 (2001) | 92 | 0 | 2% | 4% |

| Schlembach et al47 (2003) | 28 | 4.0% | 2% | Not reported |

| Dizon-Townson et al48 (1997) | 130 | 8.6% | Not reported | Not reported |

| * Heterozygous and homozygous carriers of MTHFR C677T and A1298C | ||||

| Key: MTHFR, methyltetrahydrofolate reductase | ||||

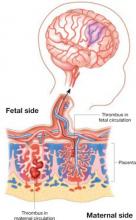

Thrombophilia leads to thrombosis at the maternal or fetal interface (FIGURE):

- When thrombosis occurs on the maternal side, the consequence may be severe preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, abruptio placenta, or fetal loss.27-29

- Thrombosis on the fetal side can be a source of emboli that bypass hepatic and pulmonary circulation and travel to the fetal brain.30 As a result, the newborn can sustain a catastrophic event such as perinatal arterial stroke via arterial thrombosis, cerebral sinus venous thrombosis, or renal vein thrombosis.25

Thrombophilia can lead to thrombosis at the maternal or the fetal interface

Thrombosis on the maternal side may lead to severe preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, abruptio placenta, or fetal loss. Thrombosis on the fetal side can be a source of emboli that bypass hepatic and pulmonary circulation and travel to the fetal brain and cause a catastrophic event, such as perinatal arterial stroke via arterial thrombosis, cerebral sinus venous thrombosis, or renal vein thrombosis.

Perinatal and neonatal stroke

Perinatal stroke is defined as a cerebrovascular event that occurs between 28 weeks of gestation and 28 days of postnatal age.30 Incidence is approximately 17 to 93 cases for every 100,000 live births.9

Neonatal stroke occurs in approximately 1 of every 4,000 live births.30 In addition, 1 in every 2,300 to 4,000 newborns is given a diagnosis of ischemic stroke in the nursery.9

Stroke and cerebral palsy

Arterial ischemic stroke in the newborn accounts for 50% to 70% of cases of congenital hemiplegic cerebral palsy.11 Factor V Leiden mutation, prothrombin gene mutation, and a deficiency of protein C, protein S, and antithrombin III have, taken together in two studies, been identified in more than 50% of cerebral ischemic strokes.31,32 In addition to these thrombophilias, important risk factors for perinatal and neonatal stroke include:

- thrombosis in placental villi or vessels

- infection

- use of an intravascular catheter.33

The mechanism that underlies perinatal stroke is a thromboembolic event that originates from either an intracranial or extracranial vessel, the heart, or the placenta.10 A recent meta-analysis by Haywood and colleagues found a statistically significant correlation between protein C deficiency, MTHFR C677T (methyltetrahydrofolate reductase), and the first occurrence of arterial ischemic stroke in a pediatric population.34 Associations between specific thrombophilias and perinatal stroke, as well as pediatric stroke, have been demonstrated (TABLE 4), but we want to emphasize that the absolute risks in these populations are very small.34,35 In addition, the infrequency of these thrombophilias in the general population (TABLE 3) means that their positive predictive value is extremely low.

TABLE 4

Fetal thrombophilia is detected in as many as two thirds of study cases of perinatal and neonatal stroke

| Type of thrombophilia | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Infants | Thrombophilia | FVL | APCR | ACA | AT | PC | PS |

| Golomb et al31 | 22 | 14 (63%) * | 1 * | 3 * | 12 * | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bonduel et al32 | 30 | 9 (30%) † | n/a | n/a | n/a | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| deVeber et al49 | 92 | 35 (38%) ‡ | 0 | 6 | 23‡ | 10‡ | 6‡ | 3‡ |

| Mercuri et al50 | 24 | 10 (42%) | 5 | n/a | n/a | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Günther et al35 | 91 | 62 (68%) | 17 | n/a | 3 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Govaert et al51 | 40 | 3 (8%) | 3 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| * FVL, APCR, and ACA diagnoses overlapped. | ||||||||

| † Three patients had anticardiolipin antibody and plasminogen deficiency. | ||||||||

| ‡ Of 35 children, 21 had multiple abnormalities (combined coagulation deficiencies). | ||||||||

| Key: ACA, anticardiolipin antibody; APCR, activated protein C resistance; AT, antithrombin deficiency; FVL, factor V Leiden; PC, protein C deficiency; PS, protein S deficiency; n/a, not available or not studied. | ||||||||

Brain injury

The brain is the largest and most vulnerable fetal organ susceptible to thrombi that are formed either in the placenta or elsewhere.16 A review of cases of cerebral palsy has revealed a pathologic finding, fetal thrombotic vasculopathy (FTV), that has been associated with brain injury.16 Arias and colleagues17 and Kraus18 have observed a correlation among cerebral palsy, a thrombophilic state, and FTV.

Furthermore, Redline found that the presence of severe fetal vascular lesions correlated highly with neurologic impairment and cerebral palsy.19

What is the take-home message?

Regrettably for patients and their offspring, evidence about the relationship between thrombophilia and an adverse neurologic outcome is insufficiently strong to offer much in the way of definitive recommendations for the obstetrician.

We can, however, make some tentative recommendations on management:

Consider screening. When cerebral palsy occurs in association with perinatal stroke, fetal and maternal screening for thrombophilia can be performed.34 The recommended thrombophilia panel comprises tests for:

- factor V Leiden

- prothrombin G20210

- anticardiolipin antibody

- MTHFR mutation.10

Family screening has also been suggested in cases of 1) multiple prothrombotic risk factors in an affected newborn and 2) a positive family history.9

The cost-effectiveness of screening for thrombophilia has not been evaluated in prospective studies, because the positive predictive value of such screening is extremely low.

Consider offering prophylaxis, with cautions. A mother whose baby has been given a diagnosis of thrombophilia and fetal or neonatal stroke can be offered thromboprophylaxis (heparin and aspirin) during any subsequent pregnancy. The usefulness of this intervention has not been well studied and is based solely on expert opinion, however, so it is imperative to counsel patients on the risks and benefits of prophylactic therapy beforehand.

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and American Academy of Pediatrics. Neonatal Encephalopathy and Cerebral Palsy: Defining the Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology. Washington DC: The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; September 2003.

2. Lynch JK, Nelson KB, Curry CJ, Grether JK. Cerebrovascular disorders in children with the factor V Leiden mutation. J Child Neurol. 2001;16:735-744.

3. Gibson CS, MacLennan AH, Goldwater PN, Dekker GA. Antenatal causes of cerebral palsy: associations between inherited thrombophilias, viral and bacterial infection, and inherited susceptibility to infection. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2003;58:209-220.

4. Ramin SM, Gilstrap LC. Other factors/conditions associated with cerebral palsy. Semin Perinatol. 2000;24:196-199.

5. Nelson KB, Dambrosia JM, Ting TY, Grether JK. Uncertain value of electronic fetal monitoring in predicting cerebral palsy. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:613-618.

6. Nelson KB, Grether JK. Potentially asphyxiating conditions and spastic cerebral palsy in infants of normal birth weight. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:507-513.

7. Himmelman K, Hagberg G, Beckung E, Hagberg B, Uvebrant P. The changing panorama of cerebral palsy in Sweden. IX. Prevalence and origin in the birth-year period 1995–1998. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94:287-294.

8. Winter S, Autry A, Boyle C, Yeargin-Allsopp M. Trends in the prevalence of cerebral palsy in a population-based study. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1220-1225.

9. Nelson KB. Thrombophilias, Thrombosis and Outcome in Pregnancy, Mother, and Child Symposium. Society of Maternal– Fetal Medicine 26th Annual Meeting. Miami Beach, Fla; 2006.

10. Nelson KB, Lynch JK. Stroke in newborn infants. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:150-158.

11. Lee J, Croen LA, Backstrand KH, et al. Maternal and infant characteristics associated with perinatal arterial stroke in the infant. JAMA. 2005;293:723-729.

12. Sarig G, Brenner B. Coagulation, inflammation and pregnancy complications. Lancet. 2004;363:96-97.

13. Fattal-Valevski A, Kenet G, Kupferminc MJ, et al. Role of thrombophilic risk factors in children with non-stroke cerebral palsy. Thromb Res. 2005;116:133-137.

14. Steiner M, Hodes MZ, Shreve M, Sundberg S, Edson JR. Postoperative stroke in a child with cerebral palsy heterozygous for factor V Leiden. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2000;22:262-264.

15. Kraus FT. Perinatal pathology, the placenta and litigation. Human Pathol. 2003;34:517-521.

16. Kraus FT, Acheen VI. Fetal thrombotic vasculopathy in the placenta: cerebral thrombi and infarcts, coagulopathies and cerebral palsy. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:759-769.

17. Arias F, Romero R, Joist H, Kraus FT. Thrombophilia: a mechanism of disease in women with adverse pregnancy outcome and thrombotic lesions in the placenta. J Matern Fetal Med. 1998;7:277-286.

18. Kraus FT. Cerebral palsy and thrombi in placental vessels in the fetus: insights from litigation. Hum Pathol. 1997;28:246-248.

19. Redline RW. Severe fetal placental vascular lesions in term infants with neurologic impairment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:452-457.

20. Kraus FT. Placental thrombi and related problems. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1993;10:275-283.

21. Rayne SC, Kraus FT. Placental thrombi and other vascular lesions: classification, morphology and clinical correlations. Pathol Res Pract. 1993;189:2-17.

22. Grafe MR. The correlation of prenatal brain damage and placental pathology. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1994;53:407-415.

23. Redline RW, O’Riordan MA. Placental lesions associated with cerebral palsy and neurologic impairment following term birth. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:1785-1791.

24. Paidas MJ, Ku DH, Arkel YS. Screening and management of inherited thrombophilias in the setting of adverse pregnancy outcome. Clin Perinatol. 2004;31:783-805.

25. Kenet G, Nowak-Göttl U. Fetal and neonatal thrombophilia. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2006;33:457-466.

26. Kujovich JL. Thrombophilia and pregnancy complications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:412-414.

27. Stella CL, How HY, Sibai BM. Thrombophilia and adverse maternal–perinatal outcome: controversies in screening and management. Am J Perinatol. 2006;23:499-506.

28. Stella CL, Sibai BM. Thrombophilia and adverse maternal–perinatal outcome. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49:850-860.

29. Sibai BM. Thrombophilia and severe preeclampsia: time to screen and treat in future pregnancies? Hypertension. 2005;46:1252-1253.

30. Lynch JK, Hirtz DG, DeVeber G, Nelson KB. Report of the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke workshop on perinatal and childhood stroke. Pediatrics. 2002;109:116-123.

31. Golomb MR, MacGregor DL, Domi T, et al. Presumed pre- or perinatal arterial ischemic stroke: risk factors and outcomes. Ann Neurol. 2001;50:163-168.

32. Bonduel M, Sciuccati G, Hepner M, Torres AF, Pieroni G, Frontroth JP. Prethrombotic disorders in children with arterial ischemic stroke and sinovenous thrombosis. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:967-971.

33. Andrew ME, Monagle P, deVeber G, Chan AK. Thromboembolic disease and antithrombotic therapy in newborns. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2001;358:374.-

34. Haywood S, Leisner R, Pindora S, Ganesan V. Thrombophilia and first arterial ischaemic stroke: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:402-405.

35. Günther G, Junker R, Sträter R, et al. Childhood Stroke Study Group. Symptomatic ischemic stroke in full-term neonates: role of acquired and genetic prothrombotic risk factors. Stroke. 2000;31:2437-2441.

36. Harum KH, Hoon AH, Jr, Kato GJ, Casella JF, Breiter SN, Johnston MV. Homozygous factor-V mutation as a genetic cause of perinatal thrombosis and cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1999;41:777-780.

37. Thorarensen O, Ryan S, Hunter J, Younkin DP. Factor V Leiden mutation: an unrecognized cause of hemiplegic cerebral palsy, neonatal stroke, and placental thrombosis. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:372-375.

38. Halliday JL, Reddihough D, Byron K, Ekert H, Ditchfield M. Hemiplegic cerebral palsy and factor V Leiden mutation. J Med Genet. 2000;37:787-789.

39. Smith RA, Skelton M, Howard M, Levene M. Is thrombophilia a factor in the development of hemiplegic cerebral palsy? Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001;43:724-730.

40. Nelson KB, Dambrosia JM, Grether JK, Phillips TM. Neonatal cytokines and coagulation factors in children with cerebral palsy. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:665-675.

41. Gibson CS, MacLennan A, Hague B, et al. Fetal thrombophilic polymorphisms are not a risk factor for cerebral palsy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189 Suppl 1:S75.-

42. Dizon-Townson D, Miller C, Sibai BM, et al. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal–Fetal Medicine Units Network. The relationship of the factor V Leiden mutation and pregnancy outcomes for mother and fetus. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:517-524.

43. Infante-Rivard C, Rivard GE, Yotov WV, et al. Absence of association of thrombophilia polymorphisms with intrauterine growth restriction. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:19-25.

44. Stanley-Christian H, Ghidini A, Sacher R, Shemirani M. Fetal genotype for specific inherited thrombophilia is not associated with severe preeclampsia. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2005;12:198-201.

45. Currie L, Peek M, McNiven M, Prosser I, Mansour J, Ridgway J. Is there an increased maternal–infant prevalence of Factor V Leiden in association with severe pre-eclampsia? BJOG. 2002;109:191-196.

46. Livingston JC, Barton JR, Park V, Haddad B, Phillips O, Sibai BM. Maternal and fetal inherited thrombophilias are not related to the development of severe preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:153-157.

47. Schlembach D, Beinder E, Zingsem J, Wunsiedler U, Beckmann MW, Fischer T. Association of maternal and/or fetal factor V Leiden and G20210A prothrombin mutation with HELLP syndrome and intrauterine growth restriction. Clin Sci (Lond). 2003;105:279-285.

48. Dizon-Townson DS, Meline L, Nelson LM, Varner M, Ward K. Fetal carriers of the factor V Leiden mutation are prone to miscarriage and placental infarction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:402-405.

49. deVeber G, Monagle P, Chan A, et al. Prothrombotic disorders in infants and children with cerebral thromboembolism. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:1539-1543.

50. Mercuri E, Cowan F, Gupte G, et al. Prothrombotic disorders and abnormal neurodevelopmental outcome in infants with neonatal cerebral infarction. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1400-1404.

51. Govaert P, Matthys E, Zecic A, Roelens F, Oostra A, Vanzieleghem B. Perinatal cortical infarction within middle cerebral artery trunks. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2000;82:F59-F63.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Thrombosis is hypothesized to be the more common mechanism underlying cerebral palsy in many cases of maternal or fetal thrombophilia; for that reason, understanding the impact of maternal and fetal thrombophilia on pregnancy outcome is of paramount importance when counseling patients.

Is a maternal and fetal thrombophilia work-up needed in women who give birth to a term infant with cerebral palsy? Prospective studies are needed to evaluate whether that is the case. In this article, we review the literature on fetal thrombophilia and its role in explaining some cases of perinatal stroke that lead, ultimately, to cerebral palsy.

The several causes of cerebral palsy

Cerebral palsy is the most common chronic motor disability of childhood. Approximately 2 to 2.5 of every 1,000 children are given a diagnosis of this disorder every year.1,2 The condition appears early in life; it is not the result of recognized progressive disease.1 Risk factors for cerebral palsy are multiple and heterogenous1,3,4-6:

- Prematurity. The risk of developing cerebral palsy correlates inversely with gestational age.7,8 A premature infant who weighs less than 1,500 g at birth has a risk of cerebral palsy that is 20 to 30 times greater than that of a full-term, normal-weight newborn.3,4

- Hypoxia and ischemia. These are the conditions most often implicated as the cause of cerebral palsy. Fetal heart-rate monitoring was introduced in the 1960s in the hope that interventions to prevent hypoxia and ischemia would reduce the incidence of cerebral palsy. But monitoring has not had that effect—most likely, because some cases of cerebral palsy are caused by perinatal stroke.9 In fact, a large, population-based study has demonstrated that potentially asphyxiating obstetrical conditions account for only about 6% of cases of cerebral palsy.6

- Thrombophilia. Several recent studies report an association between fetal thrombophilia and both neonatal stroke and cerebral palsy.10-14 That association provides a possible explanation for adverse pregnancy outcomes that have otherwise been ascribed to events during delivery.15-23 Although thrombophilia is a recognized risk factor for cerebral palsy, the strength of the association has still not been fully investigated. TABLE 1 and TABLE 2 summarize studies that have examined this association. Given the rarity of both inherited thrombophilias and cerebral palsy, however, an enormous number of cases would be required to fully establish a causal relationship.

TABLE 1

Case reports reveal an association

between fetal thrombophilias and cerebral palsy

| Thrombophilias present | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study (type) | Cases of CP | Number | Type |

| Harum et al36 (case report) | 1 | 1 | Factor V Leiden |

| Thorarensen et al37 (case report) | 3 | 3 | Factor V Leiden |

| Lynch et al2 (case series) | 8 | 8 | Factor V Leiden |

| Halliday et al38 (case series) | 55 | 5 | Factor V Leiden; prothrombin mutation |

| Smith et al39 (case series) | 38 | 7 | Factor VIIIc |

| Nelson et al40 (case series) | 31 | 20 | Factor V Leiden; protein C deficiency |

TABLE 2

How often is a fetal thrombophilia

the likely underlying cause of cerebral palsy?

| Thrombophilia* | Prevalence of CP† | Odds ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Factor V Leiden | 6.3% | 0.62 (0.37–1.05) |

| Prothrombin gene | 5.2% | 1.11 (0.59–2.06) |

| MTHFR 677 | 54.1% | 1.27 (0.97–1.66) |

| MTHFR 1298 | 39.4% | 1.08 (0.69–1.19) |

| MTHFR 677/1298 | 15.1% | 1.18 (0.82–1.69) |

| * Heterozygous or homozygous | ||

| † Among 354 subjects with thrombophilia studied41 | ||

| Key: MTHFR, methyltetrahydrofolate reductase | ||

“Thrombophilia” describes a spectrum of congenital or acquired coagulation disorders associated with venous and arterial thrombosis.24 These disorders can occur in the mother or in the fetus, or in both concomitantly.

Fetal thrombophilia has a reported incidence of 2.4 to 5.1 cases for every 100,000 births.25 Whereas maternal thrombophilia has a substantially higher incidence, both maternal and fetal thrombophilia can lead to adverse maternal and fetal events.

The incidence of specific inherited fetal thrombophilias is summarized in TABLE 3. Maternal thrombophilia is generally associated with various adverse pregnancy outcomes, particularly cerebral palsy and perinatal stroke.9,26

TABLE 3

Inherited thrombophilias among the general population

| Study | Number | Factor V Leiden | Protein gene mutation | MTHFR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gibson et al41 (2003) | 708 | 9.8% | 4.7% | 15.1%* |

| Dizon-Townson et al42 (2005) | 4,033 | 3.0% | Not reported | Not reported |

| Infante-Rivard et al43 (2002) | 472 | 3.3% | 1.3% | 43% to 49% |

| Stanley-Christian et al44 (2005) | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Currie et al45 (2002) | 46 | 13.0% | Not reported | Not reported |

| Livingston et al46 (2001) | 92 | 0 | 2% | 4% |

| Schlembach et al47 (2003) | 28 | 4.0% | 2% | Not reported |

| Dizon-Townson et al48 (1997) | 130 | 8.6% | Not reported | Not reported |

| * Heterozygous and homozygous carriers of MTHFR C677T and A1298C | ||||

| Key: MTHFR, methyltetrahydrofolate reductase | ||||

Thrombophilia leads to thrombosis at the maternal or fetal interface (FIGURE):

- When thrombosis occurs on the maternal side, the consequence may be severe preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, abruptio placenta, or fetal loss.27-29

- Thrombosis on the fetal side can be a source of emboli that bypass hepatic and pulmonary circulation and travel to the fetal brain.30 As a result, the newborn can sustain a catastrophic event such as perinatal arterial stroke via arterial thrombosis, cerebral sinus venous thrombosis, or renal vein thrombosis.25

Thrombophilia can lead to thrombosis at the maternal or the fetal interface

Thrombosis on the maternal side may lead to severe preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, abruptio placenta, or fetal loss. Thrombosis on the fetal side can be a source of emboli that bypass hepatic and pulmonary circulation and travel to the fetal brain and cause a catastrophic event, such as perinatal arterial stroke via arterial thrombosis, cerebral sinus venous thrombosis, or renal vein thrombosis.

Perinatal and neonatal stroke

Perinatal stroke is defined as a cerebrovascular event that occurs between 28 weeks of gestation and 28 days of postnatal age.30 Incidence is approximately 17 to 93 cases for every 100,000 live births.9

Neonatal stroke occurs in approximately 1 of every 4,000 live births.30 In addition, 1 in every 2,300 to 4,000 newborns is given a diagnosis of ischemic stroke in the nursery.9

Stroke and cerebral palsy

Arterial ischemic stroke in the newborn accounts for 50% to 70% of cases of congenital hemiplegic cerebral palsy.11 Factor V Leiden mutation, prothrombin gene mutation, and a deficiency of protein C, protein S, and antithrombin III have, taken together in two studies, been identified in more than 50% of cerebral ischemic strokes.31,32 In addition to these thrombophilias, important risk factors for perinatal and neonatal stroke include:

- thrombosis in placental villi or vessels

- infection

- use of an intravascular catheter.33

The mechanism that underlies perinatal stroke is a thromboembolic event that originates from either an intracranial or extracranial vessel, the heart, or the placenta.10 A recent meta-analysis by Haywood and colleagues found a statistically significant correlation between protein C deficiency, MTHFR C677T (methyltetrahydrofolate reductase), and the first occurrence of arterial ischemic stroke in a pediatric population.34 Associations between specific thrombophilias and perinatal stroke, as well as pediatric stroke, have been demonstrated (TABLE 4), but we want to emphasize that the absolute risks in these populations are very small.34,35 In addition, the infrequency of these thrombophilias in the general population (TABLE 3) means that their positive predictive value is extremely low.

TABLE 4

Fetal thrombophilia is detected in as many as two thirds of study cases of perinatal and neonatal stroke

| Type of thrombophilia | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Infants | Thrombophilia | FVL | APCR | ACA | AT | PC | PS |

| Golomb et al31 | 22 | 14 (63%) * | 1 * | 3 * | 12 * | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bonduel et al32 | 30 | 9 (30%) † | n/a | n/a | n/a | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| deVeber et al49 | 92 | 35 (38%) ‡ | 0 | 6 | 23‡ | 10‡ | 6‡ | 3‡ |

| Mercuri et al50 | 24 | 10 (42%) | 5 | n/a | n/a | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Günther et al35 | 91 | 62 (68%) | 17 | n/a | 3 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Govaert et al51 | 40 | 3 (8%) | 3 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| * FVL, APCR, and ACA diagnoses overlapped. | ||||||||

| † Three patients had anticardiolipin antibody and plasminogen deficiency. | ||||||||

| ‡ Of 35 children, 21 had multiple abnormalities (combined coagulation deficiencies). | ||||||||

| Key: ACA, anticardiolipin antibody; APCR, activated protein C resistance; AT, antithrombin deficiency; FVL, factor V Leiden; PC, protein C deficiency; PS, protein S deficiency; n/a, not available or not studied. | ||||||||

Brain injury

The brain is the largest and most vulnerable fetal organ susceptible to thrombi that are formed either in the placenta or elsewhere.16 A review of cases of cerebral palsy has revealed a pathologic finding, fetal thrombotic vasculopathy (FTV), that has been associated with brain injury.16 Arias and colleagues17 and Kraus18 have observed a correlation among cerebral palsy, a thrombophilic state, and FTV.

Furthermore, Redline found that the presence of severe fetal vascular lesions correlated highly with neurologic impairment and cerebral palsy.19

What is the take-home message?

Regrettably for patients and their offspring, evidence about the relationship between thrombophilia and an adverse neurologic outcome is insufficiently strong to offer much in the way of definitive recommendations for the obstetrician.

We can, however, make some tentative recommendations on management:

Consider screening. When cerebral palsy occurs in association with perinatal stroke, fetal and maternal screening for thrombophilia can be performed.34 The recommended thrombophilia panel comprises tests for:

- factor V Leiden

- prothrombin G20210

- anticardiolipin antibody

- MTHFR mutation.10

Family screening has also been suggested in cases of 1) multiple prothrombotic risk factors in an affected newborn and 2) a positive family history.9

The cost-effectiveness of screening for thrombophilia has not been evaluated in prospective studies, because the positive predictive value of such screening is extremely low.

Consider offering prophylaxis, with cautions. A mother whose baby has been given a diagnosis of thrombophilia and fetal or neonatal stroke can be offered thromboprophylaxis (heparin and aspirin) during any subsequent pregnancy. The usefulness of this intervention has not been well studied and is based solely on expert opinion, however, so it is imperative to counsel patients on the risks and benefits of prophylactic therapy beforehand.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Thrombosis is hypothesized to be the more common mechanism underlying cerebral palsy in many cases of maternal or fetal thrombophilia; for that reason, understanding the impact of maternal and fetal thrombophilia on pregnancy outcome is of paramount importance when counseling patients.

Is a maternal and fetal thrombophilia work-up needed in women who give birth to a term infant with cerebral palsy? Prospective studies are needed to evaluate whether that is the case. In this article, we review the literature on fetal thrombophilia and its role in explaining some cases of perinatal stroke that lead, ultimately, to cerebral palsy.

The several causes of cerebral palsy

Cerebral palsy is the most common chronic motor disability of childhood. Approximately 2 to 2.5 of every 1,000 children are given a diagnosis of this disorder every year.1,2 The condition appears early in life; it is not the result of recognized progressive disease.1 Risk factors for cerebral palsy are multiple and heterogenous1,3,4-6:

- Prematurity. The risk of developing cerebral palsy correlates inversely with gestational age.7,8 A premature infant who weighs less than 1,500 g at birth has a risk of cerebral palsy that is 20 to 30 times greater than that of a full-term, normal-weight newborn.3,4

- Hypoxia and ischemia. These are the conditions most often implicated as the cause of cerebral palsy. Fetal heart-rate monitoring was introduced in the 1960s in the hope that interventions to prevent hypoxia and ischemia would reduce the incidence of cerebral palsy. But monitoring has not had that effect—most likely, because some cases of cerebral palsy are caused by perinatal stroke.9 In fact, a large, population-based study has demonstrated that potentially asphyxiating obstetrical conditions account for only about 6% of cases of cerebral palsy.6

- Thrombophilia. Several recent studies report an association between fetal thrombophilia and both neonatal stroke and cerebral palsy.10-14 That association provides a possible explanation for adverse pregnancy outcomes that have otherwise been ascribed to events during delivery.15-23 Although thrombophilia is a recognized risk factor for cerebral palsy, the strength of the association has still not been fully investigated. TABLE 1 and TABLE 2 summarize studies that have examined this association. Given the rarity of both inherited thrombophilias and cerebral palsy, however, an enormous number of cases would be required to fully establish a causal relationship.

TABLE 1

Case reports reveal an association

between fetal thrombophilias and cerebral palsy

| Thrombophilias present | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study (type) | Cases of CP | Number | Type |

| Harum et al36 (case report) | 1 | 1 | Factor V Leiden |

| Thorarensen et al37 (case report) | 3 | 3 | Factor V Leiden |

| Lynch et al2 (case series) | 8 | 8 | Factor V Leiden |

| Halliday et al38 (case series) | 55 | 5 | Factor V Leiden; prothrombin mutation |

| Smith et al39 (case series) | 38 | 7 | Factor VIIIc |

| Nelson et al40 (case series) | 31 | 20 | Factor V Leiden; protein C deficiency |

TABLE 2

How often is a fetal thrombophilia

the likely underlying cause of cerebral palsy?

| Thrombophilia* | Prevalence of CP† | Odds ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Factor V Leiden | 6.3% | 0.62 (0.37–1.05) |

| Prothrombin gene | 5.2% | 1.11 (0.59–2.06) |

| MTHFR 677 | 54.1% | 1.27 (0.97–1.66) |

| MTHFR 1298 | 39.4% | 1.08 (0.69–1.19) |

| MTHFR 677/1298 | 15.1% | 1.18 (0.82–1.69) |

| * Heterozygous or homozygous | ||

| † Among 354 subjects with thrombophilia studied41 | ||

| Key: MTHFR, methyltetrahydrofolate reductase | ||

“Thrombophilia” describes a spectrum of congenital or acquired coagulation disorders associated with venous and arterial thrombosis.24 These disorders can occur in the mother or in the fetus, or in both concomitantly.

Fetal thrombophilia has a reported incidence of 2.4 to 5.1 cases for every 100,000 births.25 Whereas maternal thrombophilia has a substantially higher incidence, both maternal and fetal thrombophilia can lead to adverse maternal and fetal events.

The incidence of specific inherited fetal thrombophilias is summarized in TABLE 3. Maternal thrombophilia is generally associated with various adverse pregnancy outcomes, particularly cerebral palsy and perinatal stroke.9,26

TABLE 3

Inherited thrombophilias among the general population

| Study | Number | Factor V Leiden | Protein gene mutation | MTHFR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gibson et al41 (2003) | 708 | 9.8% | 4.7% | 15.1%* |

| Dizon-Townson et al42 (2005) | 4,033 | 3.0% | Not reported | Not reported |

| Infante-Rivard et al43 (2002) | 472 | 3.3% | 1.3% | 43% to 49% |

| Stanley-Christian et al44 (2005) | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Currie et al45 (2002) | 46 | 13.0% | Not reported | Not reported |

| Livingston et al46 (2001) | 92 | 0 | 2% | 4% |

| Schlembach et al47 (2003) | 28 | 4.0% | 2% | Not reported |

| Dizon-Townson et al48 (1997) | 130 | 8.6% | Not reported | Not reported |

| * Heterozygous and homozygous carriers of MTHFR C677T and A1298C | ||||

| Key: MTHFR, methyltetrahydrofolate reductase | ||||

Thrombophilia leads to thrombosis at the maternal or fetal interface (FIGURE):

- When thrombosis occurs on the maternal side, the consequence may be severe preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, abruptio placenta, or fetal loss.27-29

- Thrombosis on the fetal side can be a source of emboli that bypass hepatic and pulmonary circulation and travel to the fetal brain.30 As a result, the newborn can sustain a catastrophic event such as perinatal arterial stroke via arterial thrombosis, cerebral sinus venous thrombosis, or renal vein thrombosis.25

Thrombophilia can lead to thrombosis at the maternal or the fetal interface

Thrombosis on the maternal side may lead to severe preeclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction, abruptio placenta, or fetal loss. Thrombosis on the fetal side can be a source of emboli that bypass hepatic and pulmonary circulation and travel to the fetal brain and cause a catastrophic event, such as perinatal arterial stroke via arterial thrombosis, cerebral sinus venous thrombosis, or renal vein thrombosis.

Perinatal and neonatal stroke

Perinatal stroke is defined as a cerebrovascular event that occurs between 28 weeks of gestation and 28 days of postnatal age.30 Incidence is approximately 17 to 93 cases for every 100,000 live births.9

Neonatal stroke occurs in approximately 1 of every 4,000 live births.30 In addition, 1 in every 2,300 to 4,000 newborns is given a diagnosis of ischemic stroke in the nursery.9

Stroke and cerebral palsy

Arterial ischemic stroke in the newborn accounts for 50% to 70% of cases of congenital hemiplegic cerebral palsy.11 Factor V Leiden mutation, prothrombin gene mutation, and a deficiency of protein C, protein S, and antithrombin III have, taken together in two studies, been identified in more than 50% of cerebral ischemic strokes.31,32 In addition to these thrombophilias, important risk factors for perinatal and neonatal stroke include:

- thrombosis in placental villi or vessels

- infection

- use of an intravascular catheter.33

The mechanism that underlies perinatal stroke is a thromboembolic event that originates from either an intracranial or extracranial vessel, the heart, or the placenta.10 A recent meta-analysis by Haywood and colleagues found a statistically significant correlation between protein C deficiency, MTHFR C677T (methyltetrahydrofolate reductase), and the first occurrence of arterial ischemic stroke in a pediatric population.34 Associations between specific thrombophilias and perinatal stroke, as well as pediatric stroke, have been demonstrated (TABLE 4), but we want to emphasize that the absolute risks in these populations are very small.34,35 In addition, the infrequency of these thrombophilias in the general population (TABLE 3) means that their positive predictive value is extremely low.

TABLE 4

Fetal thrombophilia is detected in as many as two thirds of study cases of perinatal and neonatal stroke

| Type of thrombophilia | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Infants | Thrombophilia | FVL | APCR | ACA | AT | PC | PS |

| Golomb et al31 | 22 | 14 (63%) * | 1 * | 3 * | 12 * | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bonduel et al32 | 30 | 9 (30%) † | n/a | n/a | n/a | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| deVeber et al49 | 92 | 35 (38%) ‡ | 0 | 6 | 23‡ | 10‡ | 6‡ | 3‡ |

| Mercuri et al50 | 24 | 10 (42%) | 5 | n/a | n/a | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Günther et al35 | 91 | 62 (68%) | 17 | n/a | 3 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Govaert et al51 | 40 | 3 (8%) | 3 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| * FVL, APCR, and ACA diagnoses overlapped. | ||||||||

| † Three patients had anticardiolipin antibody and plasminogen deficiency. | ||||||||

| ‡ Of 35 children, 21 had multiple abnormalities (combined coagulation deficiencies). | ||||||||

| Key: ACA, anticardiolipin antibody; APCR, activated protein C resistance; AT, antithrombin deficiency; FVL, factor V Leiden; PC, protein C deficiency; PS, protein S deficiency; n/a, not available or not studied. | ||||||||

Brain injury

The brain is the largest and most vulnerable fetal organ susceptible to thrombi that are formed either in the placenta or elsewhere.16 A review of cases of cerebral palsy has revealed a pathologic finding, fetal thrombotic vasculopathy (FTV), that has been associated with brain injury.16 Arias and colleagues17 and Kraus18 have observed a correlation among cerebral palsy, a thrombophilic state, and FTV.

Furthermore, Redline found that the presence of severe fetal vascular lesions correlated highly with neurologic impairment and cerebral palsy.19

What is the take-home message?

Regrettably for patients and their offspring, evidence about the relationship between thrombophilia and an adverse neurologic outcome is insufficiently strong to offer much in the way of definitive recommendations for the obstetrician.

We can, however, make some tentative recommendations on management:

Consider screening. When cerebral palsy occurs in association with perinatal stroke, fetal and maternal screening for thrombophilia can be performed.34 The recommended thrombophilia panel comprises tests for:

- factor V Leiden

- prothrombin G20210

- anticardiolipin antibody

- MTHFR mutation.10

Family screening has also been suggested in cases of 1) multiple prothrombotic risk factors in an affected newborn and 2) a positive family history.9

The cost-effectiveness of screening for thrombophilia has not been evaluated in prospective studies, because the positive predictive value of such screening is extremely low.

Consider offering prophylaxis, with cautions. A mother whose baby has been given a diagnosis of thrombophilia and fetal or neonatal stroke can be offered thromboprophylaxis (heparin and aspirin) during any subsequent pregnancy. The usefulness of this intervention has not been well studied and is based solely on expert opinion, however, so it is imperative to counsel patients on the risks and benefits of prophylactic therapy beforehand.

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and American Academy of Pediatrics. Neonatal Encephalopathy and Cerebral Palsy: Defining the Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology. Washington DC: The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; September 2003.

2. Lynch JK, Nelson KB, Curry CJ, Grether JK. Cerebrovascular disorders in children with the factor V Leiden mutation. J Child Neurol. 2001;16:735-744.

3. Gibson CS, MacLennan AH, Goldwater PN, Dekker GA. Antenatal causes of cerebral palsy: associations between inherited thrombophilias, viral and bacterial infection, and inherited susceptibility to infection. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2003;58:209-220.

4. Ramin SM, Gilstrap LC. Other factors/conditions associated with cerebral palsy. Semin Perinatol. 2000;24:196-199.

5. Nelson KB, Dambrosia JM, Ting TY, Grether JK. Uncertain value of electronic fetal monitoring in predicting cerebral palsy. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:613-618.

6. Nelson KB, Grether JK. Potentially asphyxiating conditions and spastic cerebral palsy in infants of normal birth weight. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:507-513.

7. Himmelman K, Hagberg G, Beckung E, Hagberg B, Uvebrant P. The changing panorama of cerebral palsy in Sweden. IX. Prevalence and origin in the birth-year period 1995–1998. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94:287-294.

8. Winter S, Autry A, Boyle C, Yeargin-Allsopp M. Trends in the prevalence of cerebral palsy in a population-based study. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1220-1225.

9. Nelson KB. Thrombophilias, Thrombosis and Outcome in Pregnancy, Mother, and Child Symposium. Society of Maternal– Fetal Medicine 26th Annual Meeting. Miami Beach, Fla; 2006.

10. Nelson KB, Lynch JK. Stroke in newborn infants. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:150-158.

11. Lee J, Croen LA, Backstrand KH, et al. Maternal and infant characteristics associated with perinatal arterial stroke in the infant. JAMA. 2005;293:723-729.

12. Sarig G, Brenner B. Coagulation, inflammation and pregnancy complications. Lancet. 2004;363:96-97.

13. Fattal-Valevski A, Kenet G, Kupferminc MJ, et al. Role of thrombophilic risk factors in children with non-stroke cerebral palsy. Thromb Res. 2005;116:133-137.

14. Steiner M, Hodes MZ, Shreve M, Sundberg S, Edson JR. Postoperative stroke in a child with cerebral palsy heterozygous for factor V Leiden. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2000;22:262-264.

15. Kraus FT. Perinatal pathology, the placenta and litigation. Human Pathol. 2003;34:517-521.

16. Kraus FT, Acheen VI. Fetal thrombotic vasculopathy in the placenta: cerebral thrombi and infarcts, coagulopathies and cerebral palsy. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:759-769.

17. Arias F, Romero R, Joist H, Kraus FT. Thrombophilia: a mechanism of disease in women with adverse pregnancy outcome and thrombotic lesions in the placenta. J Matern Fetal Med. 1998;7:277-286.

18. Kraus FT. Cerebral palsy and thrombi in placental vessels in the fetus: insights from litigation. Hum Pathol. 1997;28:246-248.

19. Redline RW. Severe fetal placental vascular lesions in term infants with neurologic impairment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:452-457.

20. Kraus FT. Placental thrombi and related problems. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1993;10:275-283.

21. Rayne SC, Kraus FT. Placental thrombi and other vascular lesions: classification, morphology and clinical correlations. Pathol Res Pract. 1993;189:2-17.

22. Grafe MR. The correlation of prenatal brain damage and placental pathology. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1994;53:407-415.

23. Redline RW, O’Riordan MA. Placental lesions associated with cerebral palsy and neurologic impairment following term birth. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:1785-1791.

24. Paidas MJ, Ku DH, Arkel YS. Screening and management of inherited thrombophilias in the setting of adverse pregnancy outcome. Clin Perinatol. 2004;31:783-805.

25. Kenet G, Nowak-Göttl U. Fetal and neonatal thrombophilia. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2006;33:457-466.

26. Kujovich JL. Thrombophilia and pregnancy complications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:412-414.

27. Stella CL, How HY, Sibai BM. Thrombophilia and adverse maternal–perinatal outcome: controversies in screening and management. Am J Perinatol. 2006;23:499-506.

28. Stella CL, Sibai BM. Thrombophilia and adverse maternal–perinatal outcome. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49:850-860.

29. Sibai BM. Thrombophilia and severe preeclampsia: time to screen and treat in future pregnancies? Hypertension. 2005;46:1252-1253.

30. Lynch JK, Hirtz DG, DeVeber G, Nelson KB. Report of the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke workshop on perinatal and childhood stroke. Pediatrics. 2002;109:116-123.

31. Golomb MR, MacGregor DL, Domi T, et al. Presumed pre- or perinatal arterial ischemic stroke: risk factors and outcomes. Ann Neurol. 2001;50:163-168.

32. Bonduel M, Sciuccati G, Hepner M, Torres AF, Pieroni G, Frontroth JP. Prethrombotic disorders in children with arterial ischemic stroke and sinovenous thrombosis. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:967-971.

33. Andrew ME, Monagle P, deVeber G, Chan AK. Thromboembolic disease and antithrombotic therapy in newborns. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2001;358:374.-

34. Haywood S, Leisner R, Pindora S, Ganesan V. Thrombophilia and first arterial ischaemic stroke: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:402-405.

35. Günther G, Junker R, Sträter R, et al. Childhood Stroke Study Group. Symptomatic ischemic stroke in full-term neonates: role of acquired and genetic prothrombotic risk factors. Stroke. 2000;31:2437-2441.

36. Harum KH, Hoon AH, Jr, Kato GJ, Casella JF, Breiter SN, Johnston MV. Homozygous factor-V mutation as a genetic cause of perinatal thrombosis and cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1999;41:777-780.

37. Thorarensen O, Ryan S, Hunter J, Younkin DP. Factor V Leiden mutation: an unrecognized cause of hemiplegic cerebral palsy, neonatal stroke, and placental thrombosis. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:372-375.

38. Halliday JL, Reddihough D, Byron K, Ekert H, Ditchfield M. Hemiplegic cerebral palsy and factor V Leiden mutation. J Med Genet. 2000;37:787-789.

39. Smith RA, Skelton M, Howard M, Levene M. Is thrombophilia a factor in the development of hemiplegic cerebral palsy? Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001;43:724-730.

40. Nelson KB, Dambrosia JM, Grether JK, Phillips TM. Neonatal cytokines and coagulation factors in children with cerebral palsy. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:665-675.

41. Gibson CS, MacLennan A, Hague B, et al. Fetal thrombophilic polymorphisms are not a risk factor for cerebral palsy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189 Suppl 1:S75.-

42. Dizon-Townson D, Miller C, Sibai BM, et al. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal–Fetal Medicine Units Network. The relationship of the factor V Leiden mutation and pregnancy outcomes for mother and fetus. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:517-524.

43. Infante-Rivard C, Rivard GE, Yotov WV, et al. Absence of association of thrombophilia polymorphisms with intrauterine growth restriction. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:19-25.

44. Stanley-Christian H, Ghidini A, Sacher R, Shemirani M. Fetal genotype for specific inherited thrombophilia is not associated with severe preeclampsia. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2005;12:198-201.

45. Currie L, Peek M, McNiven M, Prosser I, Mansour J, Ridgway J. Is there an increased maternal–infant prevalence of Factor V Leiden in association with severe pre-eclampsia? BJOG. 2002;109:191-196.

46. Livingston JC, Barton JR, Park V, Haddad B, Phillips O, Sibai BM. Maternal and fetal inherited thrombophilias are not related to the development of severe preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:153-157.

47. Schlembach D, Beinder E, Zingsem J, Wunsiedler U, Beckmann MW, Fischer T. Association of maternal and/or fetal factor V Leiden and G20210A prothrombin mutation with HELLP syndrome and intrauterine growth restriction. Clin Sci (Lond). 2003;105:279-285.

48. Dizon-Townson DS, Meline L, Nelson LM, Varner M, Ward K. Fetal carriers of the factor V Leiden mutation are prone to miscarriage and placental infarction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:402-405.

49. deVeber G, Monagle P, Chan A, et al. Prothrombotic disorders in infants and children with cerebral thromboembolism. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:1539-1543.

50. Mercuri E, Cowan F, Gupte G, et al. Prothrombotic disorders and abnormal neurodevelopmental outcome in infants with neonatal cerebral infarction. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1400-1404.

51. Govaert P, Matthys E, Zecic A, Roelens F, Oostra A, Vanzieleghem B. Perinatal cortical infarction within middle cerebral artery trunks. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2000;82:F59-F63.

1. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and American Academy of Pediatrics. Neonatal Encephalopathy and Cerebral Palsy: Defining the Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology. Washington DC: The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; September 2003.

2. Lynch JK, Nelson KB, Curry CJ, Grether JK. Cerebrovascular disorders in children with the factor V Leiden mutation. J Child Neurol. 2001;16:735-744.

3. Gibson CS, MacLennan AH, Goldwater PN, Dekker GA. Antenatal causes of cerebral palsy: associations between inherited thrombophilias, viral and bacterial infection, and inherited susceptibility to infection. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2003;58:209-220.

4. Ramin SM, Gilstrap LC. Other factors/conditions associated with cerebral palsy. Semin Perinatol. 2000;24:196-199.

5. Nelson KB, Dambrosia JM, Ting TY, Grether JK. Uncertain value of electronic fetal monitoring in predicting cerebral palsy. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:613-618.

6. Nelson KB, Grether JK. Potentially asphyxiating conditions and spastic cerebral palsy in infants of normal birth weight. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:507-513.

7. Himmelman K, Hagberg G, Beckung E, Hagberg B, Uvebrant P. The changing panorama of cerebral palsy in Sweden. IX. Prevalence and origin in the birth-year period 1995–1998. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94:287-294.

8. Winter S, Autry A, Boyle C, Yeargin-Allsopp M. Trends in the prevalence of cerebral palsy in a population-based study. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1220-1225.

9. Nelson KB. Thrombophilias, Thrombosis and Outcome in Pregnancy, Mother, and Child Symposium. Society of Maternal– Fetal Medicine 26th Annual Meeting. Miami Beach, Fla; 2006.

10. Nelson KB, Lynch JK. Stroke in newborn infants. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:150-158.

11. Lee J, Croen LA, Backstrand KH, et al. Maternal and infant characteristics associated with perinatal arterial stroke in the infant. JAMA. 2005;293:723-729.

12. Sarig G, Brenner B. Coagulation, inflammation and pregnancy complications. Lancet. 2004;363:96-97.

13. Fattal-Valevski A, Kenet G, Kupferminc MJ, et al. Role of thrombophilic risk factors in children with non-stroke cerebral palsy. Thromb Res. 2005;116:133-137.

14. Steiner M, Hodes MZ, Shreve M, Sundberg S, Edson JR. Postoperative stroke in a child with cerebral palsy heterozygous for factor V Leiden. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2000;22:262-264.

15. Kraus FT. Perinatal pathology, the placenta and litigation. Human Pathol. 2003;34:517-521.

16. Kraus FT, Acheen VI. Fetal thrombotic vasculopathy in the placenta: cerebral thrombi and infarcts, coagulopathies and cerebral palsy. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:759-769.

17. Arias F, Romero R, Joist H, Kraus FT. Thrombophilia: a mechanism of disease in women with adverse pregnancy outcome and thrombotic lesions in the placenta. J Matern Fetal Med. 1998;7:277-286.

18. Kraus FT. Cerebral palsy and thrombi in placental vessels in the fetus: insights from litigation. Hum Pathol. 1997;28:246-248.

19. Redline RW. Severe fetal placental vascular lesions in term infants with neurologic impairment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:452-457.

20. Kraus FT. Placental thrombi and related problems. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1993;10:275-283.

21. Rayne SC, Kraus FT. Placental thrombi and other vascular lesions: classification, morphology and clinical correlations. Pathol Res Pract. 1993;189:2-17.

22. Grafe MR. The correlation of prenatal brain damage and placental pathology. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1994;53:407-415.

23. Redline RW, O’Riordan MA. Placental lesions associated with cerebral palsy and neurologic impairment following term birth. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:1785-1791.

24. Paidas MJ, Ku DH, Arkel YS. Screening and management of inherited thrombophilias in the setting of adverse pregnancy outcome. Clin Perinatol. 2004;31:783-805.

25. Kenet G, Nowak-Göttl U. Fetal and neonatal thrombophilia. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2006;33:457-466.

26. Kujovich JL. Thrombophilia and pregnancy complications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:412-414.

27. Stella CL, How HY, Sibai BM. Thrombophilia and adverse maternal–perinatal outcome: controversies in screening and management. Am J Perinatol. 2006;23:499-506.

28. Stella CL, Sibai BM. Thrombophilia and adverse maternal–perinatal outcome. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49:850-860.

29. Sibai BM. Thrombophilia and severe preeclampsia: time to screen and treat in future pregnancies? Hypertension. 2005;46:1252-1253.

30. Lynch JK, Hirtz DG, DeVeber G, Nelson KB. Report of the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke workshop on perinatal and childhood stroke. Pediatrics. 2002;109:116-123.

31. Golomb MR, MacGregor DL, Domi T, et al. Presumed pre- or perinatal arterial ischemic stroke: risk factors and outcomes. Ann Neurol. 2001;50:163-168.

32. Bonduel M, Sciuccati G, Hepner M, Torres AF, Pieroni G, Frontroth JP. Prethrombotic disorders in children with arterial ischemic stroke and sinovenous thrombosis. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:967-971.

33. Andrew ME, Monagle P, deVeber G, Chan AK. Thromboembolic disease and antithrombotic therapy in newborns. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2001;358:374.-

34. Haywood S, Leisner R, Pindora S, Ganesan V. Thrombophilia and first arterial ischaemic stroke: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:402-405.

35. Günther G, Junker R, Sträter R, et al. Childhood Stroke Study Group. Symptomatic ischemic stroke in full-term neonates: role of acquired and genetic prothrombotic risk factors. Stroke. 2000;31:2437-2441.

36. Harum KH, Hoon AH, Jr, Kato GJ, Casella JF, Breiter SN, Johnston MV. Homozygous factor-V mutation as a genetic cause of perinatal thrombosis and cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1999;41:777-780.

37. Thorarensen O, Ryan S, Hunter J, Younkin DP. Factor V Leiden mutation: an unrecognized cause of hemiplegic cerebral palsy, neonatal stroke, and placental thrombosis. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:372-375.

38. Halliday JL, Reddihough D, Byron K, Ekert H, Ditchfield M. Hemiplegic cerebral palsy and factor V Leiden mutation. J Med Genet. 2000;37:787-789.

39. Smith RA, Skelton M, Howard M, Levene M. Is thrombophilia a factor in the development of hemiplegic cerebral palsy? Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001;43:724-730.

40. Nelson KB, Dambrosia JM, Grether JK, Phillips TM. Neonatal cytokines and coagulation factors in children with cerebral palsy. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:665-675.

41. Gibson CS, MacLennan A, Hague B, et al. Fetal thrombophilic polymorphisms are not a risk factor for cerebral palsy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189 Suppl 1:S75.-

42. Dizon-Townson D, Miller C, Sibai BM, et al. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal–Fetal Medicine Units Network. The relationship of the factor V Leiden mutation and pregnancy outcomes for mother and fetus. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:517-524.

43. Infante-Rivard C, Rivard GE, Yotov WV, et al. Absence of association of thrombophilia polymorphisms with intrauterine growth restriction. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:19-25.

44. Stanley-Christian H, Ghidini A, Sacher R, Shemirani M. Fetal genotype for specific inherited thrombophilia is not associated with severe preeclampsia. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2005;12:198-201.

45. Currie L, Peek M, McNiven M, Prosser I, Mansour J, Ridgway J. Is there an increased maternal–infant prevalence of Factor V Leiden in association with severe pre-eclampsia? BJOG. 2002;109:191-196.

46. Livingston JC, Barton JR, Park V, Haddad B, Phillips O, Sibai BM. Maternal and fetal inherited thrombophilias are not related to the development of severe preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:153-157.

47. Schlembach D, Beinder E, Zingsem J, Wunsiedler U, Beckmann MW, Fischer T. Association of maternal and/or fetal factor V Leiden and G20210A prothrombin mutation with HELLP syndrome and intrauterine growth restriction. Clin Sci (Lond). 2003;105:279-285.

48. Dizon-Townson DS, Meline L, Nelson LM, Varner M, Ward K. Fetal carriers of the factor V Leiden mutation are prone to miscarriage and placental infarction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:402-405.

49. deVeber G, Monagle P, Chan A, et al. Prothrombotic disorders in infants and children with cerebral thromboembolism. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:1539-1543.

50. Mercuri E, Cowan F, Gupte G, et al. Prothrombotic disorders and abnormal neurodevelopmental outcome in infants with neonatal cerebral infarction. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1400-1404.

51. Govaert P, Matthys E, Zecic A, Roelens F, Oostra A, Vanzieleghem B. Perinatal cortical infarction within middle cerebral artery trunks. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2000;82:F59-F63.

Thrombophilia in pregnancy: Whom to screen, when to treat

Why thrombophilia matters

During pregnancy, clotting factors I, VII, VIII, IX, and X rise; protein S and fibrinolytic activity diminish; and resistance to activated protein C develops.1,2 When compounded by thrombophilia—a broad spectrum of coagulation disorders that increase the risk for venous and arterial thrombosis—the hypercoagulable state of pregnancy may increase the risk of thromboembolism during pregnancy or postpartum.3

Pulmonary embolism is the leading cause of maternal death in the United States.1 Concern about this lethal sequela has led to numerous recommendations for screening and subsequent prophylaxis and therapy.

Two types

Thrombophilias are inherited or acquired (TABLE 1). The most common inherited disorders during pregnancy are mutations in factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene, and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) (TABLE 2). Caucasians have a higher rate of genetic thrombophilias than other racial groups.

Antiphospholipid antibody (APA) syndrome is the most common acquired thrombophilia of pregnancy. It can be diagnosed when the immunoglobulin G or immunoglobulin M level is 20 g per liter or higher, when lupus anticoagulant is present, or both.4

TABLE 1

Thrombophilias are inherited or acquired

INHERITED

|

ACQUIRED

|

| MTHFR=methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase |

Prevalence of thrombophilias in women with normal pregnancy outcomes

| THROMBOPHILIA | PREVALENCE (%) |

|---|---|

| Factor V Leiden mutation | 2–10 |

| MTHFR mutation | 8–16 |

| Prothrombin gene mutation | 2–6 |

| Protein C and S deficiencies | 0.2–1.0* |

| Anticardiolipin antibodies | 1–7 |

| * Combined rate | |

| MTHFR=methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase | |

Link to adverse pregnancy outcomes

During the past 2 decades, several epidemiologic and case-control studies have explored the association between thrombophilias and adverse pregnancy outcomes,2-6 which include the following maternal effects:

- Venous thromboembolism, including deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and cerebral vein thrombosis

- Arterial thrombosis (peripheral, cerebral)

- Severe preeclampsia

- Thrombosis and infarcts

- Abruptio placenta

- Recurrent miscarriage

- Fetal growth restriction

- Death

- Stroke

Preeclampsia and thrombophilia

The association between preeclampsia and thrombophilia remains somewhat unclear because of inconsistent data. Because of this, we do not recommend routine screening for thrombophilia in women with preeclampsia.

An association between inherited thrombophilias and preeclampsia was reported by Dekker et al in 1995.7 Since then, numerous retrospective and case-controlled studies have assessed the incidence of thrombophilia in women with severe preeclampsia.7-25 Their findings range from:

- Factor V Leiden: 3.7% to 26.5%

- Prothrombin gene mutation: 0 to 10.8%

- Protein S deficiency: 0.7% to 24.7%

- MTHFR variant: 6.7% to 24.0%

Other points of contention are the varying levels of severity of preeclampsia and of gestational age at delivery, as well as racial differences. For example, most studies found an association between thrombophilia and severe preeclampsia at less than 34 weeks’ gestation, but not between thrombophilia and mild preeclampsia at term. In addition, a recent prospective observational study at multiple centers involving 5,168 women found a factor V Leiden mutation rate of 6% among white women, 2.3% among Asians, 1.6% in Hispanics, and 0.8% in African Americans.8 This large study found no association between thrombophilia and preeclampsia in these women. Therefore, based on available data, we do not recommend routine screening for factor V Leiden in women with severe preeclampsia.

Preeclampsia and APA syndrome

In 1989, Branch et al26 first reported an association between APA syndrome and severe preeclampsia at less than 34 weeks’ gestation. They recommended that women with severe preeclampsia at this gestational age be screened for APA syndrome and treated when the screen is positive. Several later studies supported or refuted the association between APA syndrome and preeclampsia,26,27 and a recent report concluded that routine testing for APA syndrome in women with early-onset preeclampsia is unwarranted.26 Therefore, we do not recommend routine screening for APA in women with severe preeclampsia.

No need to screen women with abruptio placenta

The placental circulation is comparable to venous circulation, with low pressure and low flow velocity rendering it susceptible to thrombotic complications at the maternal–placental interface and consequent premature separation of the placenta.

It is difficult to confirm an association between thrombophilia and abruptio placenta because of confounding variables such as chronic hypertension, cigarette and cocaine use, and advanced maternal age.3 Studies reviewing this association are scarce, and screening for thrombophilia is discouraged in pregnancies marked by abruptio placenta.

Kupferminc et al28 found that 25%, 20%, and 15% of thrombophilia patients with placental abruption had mutations in factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene, and MTHFR, respectively. In contrast, Prochazka et al29 found 15.7% of their cohort of patients with abruptio placenta to have factor V Leiden mutation.

A large prospective, observational study of more than 5,000 asymptomatic pregnant women at multiple centers found no association between abruptio placenta and factor V Leiden mutation.8 Nor were there cases of abruptio placenta among 134 women who were heterozygous for factor V Leiden.

And no routine screening in cases of IUGR

Routine screening for thrombophilias in women with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) is not recommended. One reason: The prevalence of thrombophilias in these women ranges widely, depending on the study cited: from 2.8% to 35% for factor V Leiden and 2.8% to 15.4% for prothrombin gene mutation (TABLE 3). In addition, in contrast to earlier studies, a large case-control trial by Infante-Rivard et al30 found no increased risk of IUGR in women with thrombophilias, except for a subgroup of women with the MTHFR variant who did not take a prenatal multivitamin.

A recent meta-analysis of case-control studies by Howley et al31 found a significant association between factor V Leiden, the prothrombin gene variant, and IUGR, but the investigators cautioned that this strong association may be driven by small, poor-quality studies that yield extreme associations. A multicenter observational study by Dizon-Townson et al8 found no association between thrombophilia and IUGR in asymptomatic gravidas.

TABLE 3

Incidence of thrombophilias in women with intrauterine growth restriction

| STUDY | FACTOR V LEIDEN (%) | PROTHROMBIN GENE MUTATION (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IUGR | CONTROLS | IUGR | CONTROLS | |

| Kupferminc et al50 | 5/44 (11.4) | 7/110 (6.4) | 5/44 (11.4) | 3/110 (2.7) |

| Infante-Rivard et al30 | 22/488 (4.5) | 18/470 (3.8) | 12/488 (2.5) | 11/470 (2.3) |

| Verspyck et al51 | 4/97 (4.1) | 1/97 (1) | 3/97 (3.1) | 1/97 (1) |

| McCowan et al52 | 4/145 (2.8) | 11/290 (3.8) | 4/145 (2.8) | 9/290 (3.1) |

| Dizon-Townson et al*10 | 6/134 (4.5) | 233/4,753 (4.9) | NR | NR |

| Kupferminc**34 | 9/26 (35) | 2/52 (3.8) | 4/26 (15.4) | 2/52 (3.8) |

| * | ||||

| ** Mid-trimester severe intrauterine growth restriction | ||||

| IUGR=intrauterine growth restriction, NR=not recorded | ||||

| SOURCE: Adapted from Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49:850–860 | ||||

Fetal loss is a complication of thrombophilia

One in 10 pregnancies ends in early death of the fetus (before 20 weeks), and 1 in 200 gestations ends in late fetal loss.32 When fetal loss occurs in the second and third trimesters, it is due to excessive thrombosis of the placental vessels, placental infarction, and secondary uteroplacental insufficiency.2,33 Women who are carriers of factor V or prothrombin gene mutations are at higher risk of late fetal loss than noncarriers are (TABLE 4).

Fetal loss is a well-established complication in women with thrombophilia, but not all thrombophilias are associated with fetal loss, according to a meta-analysis of 31 studies.33 In women with thrombophilia, first-trimester loss is generally associated with factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene mutation, and activated protein C resistance. Late, nonrecurrent fetal loss is associated with factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene mutation, and protein S deficiency.33

TABLE 4

Incidence of factor V Leiden mutation in women with recurrent pregnancy loss

| STUDY | PATIENT SELECTION | PATIENTS (%) | CONTROLS (%) | ODDS RATIO | 95% CONFIDENCE INTERVAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grandone et al53 | ≥2 unexplained fetal losses, other causes excluded | 7/43 (16.3) | 5/118 (4.2) | 4.4 | 1.3–14.7 |

| Ridker et al54 | Recurrent, spontaneous abortion, other causes not excluded | 9/113 (8) | 16/437 (3.7) | 2.3 | 1.0–5.2 |

| Sarig et al55 | ≥3 first- or second-trimester losses or ≥1 intrauterine fetal demise, other causes excluded* | 96/145 (66) | 41/145 (28) | 5.0 | 3.0–8.5 |

| * Excluded chromosomal abnormalities, infections, anatomic alterations, and endocrine dysfunction | |||||

History of adverse outcomes? Offer screening

It is well established that women with a history of fetal death, severe preeclampsia, IUGR, abruptio placenta, or recurrent miscarriage have an increased risk of recurrence in subsequent pregnancies.3,30,34-36 The rate of recurrence of any of these outcomes may be as high as 46% with a history of 2 or more adverse outcomes, even before any thrombophilia is taken into account.3 Although there are few studies describing the rate of recurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with thrombophilia and a previous adverse outcome (TABLE 5), it appears to range from 66% to 83% in untreated women.3,37

Based on these findings, some authors recommend screening for thrombophilia in women who have had adverse pregnancy outcomes3,9,38 and prophylactic therapy in subsequent pregnancies when the test is positive. Therapy includes low-dose aspirin with or without subcutaneous heparin, as well as folic acid and vitamin B6 supplements, according to the type of thrombophilia present as well as the nature of the previous adverse outcome.

TABLE 5

How women with a previous adverse outcome fare on anticoagulation therapy

| STUDY | PATIENTS | PREVIOUS ADVERSE PREGNANCY OUTCOME | ANTICOAGULANT | OUTCOME IN CURRENT PREGNANCY |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Riyazi et al9 | 26 | Uteroplacental insufficiency | LMWH and low-dose aspirin | Decreased recurrence of preeclampsia (85% to 38%) and IUGR (54% to 15%) |

| Brenner37 | 50 | ≥3 first-trimester recurrent pregnancy losses with thrombophilia | LMWH | Higher live birth rate compared with historical controls (75% vs 20%) |

| Ogueh et al48 | 24 | Previous adverse pregnancy outcome plus history of thromboembolic disease, family history of thrombophilia | UFH | No significant mprovement |

| Kupferminc et al38 | 33 | Thrombophilia with history of preeclampsia or IUGR | LMWH and low-dose aspirin | With treatment, 3% recurrence of preeclampsia |

| Grandone et al53 | 25 | Repeated pregnancy loss, gestational hypertension, HELLP, or IUGR | UFH or LMWH | 90.3% treated with LMWH had good obstetric outcome |

| Paidas et al3 | 158 | Fetal loss, IUGR, placental abruption, or preeclampsia | UFH or LMWH | 80% reduction in risk of adverse pregnancy outcome, compared with historical controls (OR, 0.21; 95% CI, 0.11–0.39) |

| HELLP=hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets; IUGR=intrauterine growth restriction; LMWH=low-molecular-weight heparin; UFH=unfractionated heparin | ||||

| SOURCE: Adapted from Am J Perinatol. 2006;23:499–506 | ||||

No randomized trials on prophylaxis

We lack randomized trials evaluating thromboprophylaxis for prevention of recurrent adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with previous severe preeclampsia, IUGR, or abruptio placenta in association with genetic thrombophilia. Therefore, any recommendation to treat such women with low-molecular-weight heparin with or without low-dose aspirin in subsequent pregnancies should remain empiric and/or prescribed after appropriate counseling of the patients regarding risks and benefits.

TABLE 6 summarizes the risk of thromboembolism in women with thrombophilia—both for asymptomatic patients and for those with a history of thromboembolism. These percentages should be used when counseling women about their risk and determining management and therapy.

TABLE 6

Risk of thromboembolism during pregnancy and postpartum in women with thrombophilia

| THROMBOPHILIA | RISK (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| ASYMPTOMATIC WOMEN | HISTORY OF VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM | |

| Factor V Leiden | ||

| Heterozygous | 0.2 | 10 |

| Homozygous | 1–2 | 15–20 |

| Prothrombin gene mutation | ||

| Heterozygous | 0.5 | 10 |

| Homozygous | 2.3 | 20 |

| Factor V Leiden and prothrombin gene mutation | 5 | 20 |

| Antithrombin deficiency | 7 | 40 |

| Protein C deficiency | 0.5 | 5–15 |

| Protein S deficiency | 0.1 | Unknown |

Prophylaxis for APA syndrome and recurrent pregnancy loss

Several randomized trials have described the use of low-dose aspirin and heparin in women with APA syndrome and a history of recurrent pregnancy loss, although the results are inconsistent (TABLE 7).39-45 The inconsistency may be due to varying definitions of APA syndrome and gestational age at the time of randomization, as well as the population studied (previous thromboembolism, presence or absence of lupus anticoagulant, level of titer of anticardiolipin antibodies, presence or absence of previous stillbirth). Nevertheless, we recommend that women with true APA syndrome (presence of lupus anticoagulant, high titers of immunoglobulin G, history of thromboembolism or recurrent stillbirth) receive prophylaxis with low-dose aspirin, with subcutaneous heparin added once fetal cardiac activity is documented.46

TABLE 7

Live births in women with APA and a history of fetal loss

| STUDY | TREATMENT | CONTROL | NO. OF LIVE BIRTHS (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TREATED WOMEN | CONTROL GROUP | |||

| Cowchock et al39 | Aspirin/heparin | Aspirin/prednisone | 9/12 (75) | 6/8 (75) |

| Laskin et al40 | Aspirin/prednisone | Placebo | 25/42 (60) | 24/46 (52) |

| Kutteh41 | Aspirin/heparin | Aspirin only | 20/25 (80) | 11/25 (44) |

| Rai et al42 | Aspirin/heparin | Aspirin only | 32/45 (71) | 19/45 (42) |

| Silver et al43 | Aspirin/prednisone | Aspirin only | 12/12 (100) | 22/22 (100) |

| Pattison et al44 | Aspirin | Placebo | 16/20 (80) | 17/20 (85) |

| Farquharson et al45 | Aspirin/LMWH | Aspirin only | 40/51 (78) | 34/47 (72) |

| LMWH=low-molecular-weight heparin | ||||

Genetic thrombophilias

Few published studies describe prophylactic use of low-molecular-weight heparin with or without low-dose aspirin in women with genetic thrombophilia and a history of adverse pregnancy outcomes. All but 1 of these studies are observational, comparing outcome in the treated pregnancy with that of previously untreated gestations in the same woman.3,9,38,44,45,47 These studies included a limited number of women and a heterogeneous group of patients with various thrombophilias; they also involved different therapies (TABLE 7).3,9,38,41,48,49

Gris et al47 performed a randomized trial in 160 women with at least 1 prior fetal loss after 10 weeks’ gestation who were heterozygous for factor V Leiden or prothrombin G20210A mutation, or had protein S deficiency. Beginning at 8 weeks’ gestation, these women were assigned to treatment with 40 mg of enoxaparin (n=80) or 100 mg of low-dose aspirin (n=80) daily. All women also received 5 mg of folic acid daily.

In the women treated with enoxaparin, 69 (86%) had a live birth, compared with 23 (29%) women treated with low-dose aspirin. The women treated with enoxaparin also had significantly higher median neonatal birth weights and a lower rate of IUGR (10% versus 30%). The authors concluded that women with factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene mutation, or protein S deficiency and a history of fetal loss should receive enoxaparin prophylaxis in subsequent pregnancies.

History of severe preeclampsia, IUGR, or abruptio placenta. No randomized trials have evaluated thromboprophylaxis in women with this history who have genetic thrombophilia. For this reason, any recommendation to treat these women with low-molecular-weight heparin with or without low-dose aspirin in subsequent pregnancies remains empiric. Prophylaxis can be prescribed after an appropriate discussion of risks and benefits with the patient.

Unresolved questions keep management experimental

What is the likelihood that a woman carrying a gene mutation that predisposes her to thrombophilia will have a serious complication during pregnancy? And how safe and effective is prophylaxis?

There is a prevailing need for a double-blind placebo-controlled trial to address these questions and evaluate the benefit of heparin in pregnant women with a history of adverse pregnancy outcomes and thrombophilia. Until then, screening and treatment for thrombophilia remain experimental in these women.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. Thromboembolism in pregnancy. ACOG Practice Bulletin #19. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2000.

2. Kujovich JL. Thrombophilia and pregnancy complications. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:412-424.

3. Paidas MJ, De-Hui WK, Arkel YS. Screening and management of inherited thrombophilias in the setting of adverse pregnancy outcome. Clin Perinatol. 2004;31:783-805.

4. Lee RM, Brown MA, Branch DW, Ward K, Silver RM. Anticardiolipin and anti-B2 glycoprotein-I antibodies in preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:294-300.

5. Lin L, August P. Genetic thrombophilias and preeclampsia: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:182-192.