User login

Sustainability of Ambulatory Safety Event Reporting Improvement After Intervention Discontinuation

From Novant Health and Novant Health Medical Group, Winston-Salem, NC (Dr. C

Abstract

- Objective: An educational intervention stressing anonymous, voluntary safety event reporting together with monthly regular audit and feedback led to significantly increased reporting of safety events in a nonacademic, community practice setting during a 15-month intervention period. We assessed whether these increased reporting rates would be sustained during the 30-month period after the intervention was discontinued.

- Methods: We reviewed all patient safety events reported in our ambulatory clinics for the period 2012–2016, and selected 6 clinics that comprised the intervention collaborative and 18 specialty- and size-matched clinics (1:3 match) that comprised the comparator group. To test the changes in safety event reporting (SER) rates between the intervention and postintervention periods for the intervention collaborative, interrupted time series analysis with a control group was performed.

- Results: The SER rate peaked in the first month following the start of the intervention. Following discontinuation of regular auditing and feedback, reporting rates declined abruptly and reverted to baseline by 16 months post intervention.

- Conclusion: It is likely that sustaining enhanced reporting rates requires ongoing audit and feedback to maintain a focus on event reporting.

Keywords: patient safety; safety event reporting; voluntary reporting system; risk management; ambulatory clinic.

We have previously shown that patient safety reporting rates for a 6-practice collaborative group in our non-academic community clinics increased 10-fold after we implemented an improvement initiative consisting of an initial education session followed by provision of monthly audit and written and in-person feedback [1]. The intervention was implemented for 15 months, and after discontinuation of the intervention we have continued to monitor reporting rates. Our objective was to assess whether the increased reporting rates observed in this collaborative during the intervention period would be sustained for 30 months following the intervention.

Methods

This study’s methods have been described in detail previously [1]. For this improvement initiative, we reviewed all patient safety events reported in our ambulatory clinics for the period 2012–2016. We identified 6 clinics, the intervention collaborative, in family medicine (n = 3), pediatrics (n = 2), and general surgery (n = 1), and 18 specialty- and size-matched clinics (1:3 match), the comparator group [1]. For the intervention collaborative only, we provided an initial 1-hour educational session on safety events with a listing of all safety event types, along with a 1-page reporting form for voluntary, anonymous submission, with use of the term “safety event” rather than “ error,” to support a nonpunitive culture. After the educational session, we provided monthly audit and written and in-person feedback with peer comparison data by clinic. Monthly audit and feedback continued throughout the intervention and was discontinued postintervention. For event reporting, in our inpatient and outpatient facilities we used VIncident (Verge Solutions, Mt. Pleasant, SC) for the period 2012–2015 and RL6: Risk (RL Solutions, Toronto, ON) for 2016.

The baseline period was 15 months (January 2012–March 2013), the intervention period was 15 months (April 2013–June 2014), and the postintervention period was 30 months (July 2014–December 2016). All 24 clinics were monitored for the 60-month period.

To test the changes in the rate of safety event reporting (SER) between the pre-intervention and postintervention periods and between the intervention and the postintervention periods, interrupted time series (ITS) analysis with a control group was performed using PROC AUTOREG in SAS Enterprise Guide 6.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Because SER rates are reported monthly, ITS analysis was used to control for autocorrelation, nonstationary variance, seasonality, and trends [2,3].

Results

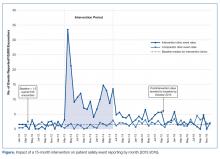

The SER rate was assessed monthly, so the number of SER rates for each group (intervention and comparator) was 15 during the pre-intervention and intervention periods, respectively, and 30 during the postintervention period. During the pre-intervention period, the intervention collaborative’s baseline median rate of safety events reported was 1.5 per 10,000 patient encounters (Figure). Also, for the intervention collaborative, the pre-intervention baseline mean (standard deviation, SD) SER rate (per 10,000 patient encounters by month) was 1.3 (1.2), the intervention mean SER rate was 12.0 (7.3), and the postintervention rate was 3.2 (1.8). Based on the ITS analysis, there was a significant change in the SER rate between the intervention and postintervention periods for the intervention collaborative (P = 0.01).

The SER rate peaked in the first month following the start of the intervention. After discontinuation of feedback, reporting rates declined abruptly and reverted to baseline by 16 months post intervention (Figure). The postintervention SER rate was also significantly higher than the pre-intervention rate (P = 0.001).

For the comparator clinics, no significant change in SER rates occurred for the 3 time periods.

Discussion

In this initiative with a 5-year reporting window, we had previously shown that with education and prospective audit and feedback, we could achieve a 10-fold increase in patient SER rates among a multi-practice collaborative while the intervention was maintained [1]. Even though there was a modest but significant increase in the SER rate in the postintervention period for the 6-clinic intervention collaborative compared to baseline, the substantial gains seen during the course of the intervention were not maintained when monthly audit and feedback ceased and monitoring continued for 30 months.

Limitations of this study include possible selection bias resulting from including clinics felt likely to participate rather than identifying clinics in a random fashion. In addition, we did not attempt to determine the specific reasons for the decrease in reporting among these clinics.

The few studies of ambulatory SER do not adequately address the effect of intervention cessation, but researchers who implemented other ambulatory quality improvement efforts have reported that gains often deteriorate or revert to baseline without consistent, ongoing feedback [4]. Likewise, in hospital-based residency programs, a multifaceted approach that includes feedback can increase SER rates, but it is uncertain if the success of this approach can be maintained long-term without continuing feedback of some type [5–7].

There are likely many factors influencing SER in ambulatory clinics, many of which are also applicable in the hospital setting. These include ease of reporting, knowing what events to report, confidentiality of reporting, and the belief that reporting makes a difference in enhancing patient safety [8]. A strong culture of safety in ambulatory clinics may lead to enhanced voluntary SER [9], and a nonpunitive, team-based approach has been advocated to promote reporting and improve ambulatory safety [10]. Historically, our ambulatory medical group clinics have had a strong culture of safety and, with patient safety coaches present in all of our clinics, we have supported a nonpunitive, team-based approach to SER [11].

In our intervention, we made reporting safety events easy, reporters knew which events to report, events could be reported anonymously, and reporters were rewarded, at least with data feedback, for reporting. The only factor known to have changed was discontinuation of monthly feedback. Which factors are most important could not be determined by our work, but we strongly suspect that sustaining enhanced reporting rates requires ongoing audit and feedback to maintain a focus on event reporting.

Corresponding author: Herbert Clegg, MD, 108 Providence Road, Charlotte NC, 28207, hwclegg@novanthealth.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Clegg HW, Cardwell T, West AM, Ferrell F. Improved safety event reporting in outpatient, nonacademic practices with an anonymous, nonpunitive approach. J Clin Outcomes Manag 2015;22:66–72.

2. Newland JG, Stach LM, De Lurgio SA, et al. Impact of a prospective-audit-with-feedback antimicrobial stewardship program at a children’s hospital. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2012; 1:179–86.

3. Penfold RB, Zhang F. Use of interrupted time series analysis in evaluating health care quality improvements. Acad Pediatr 2013;13 (6 Suppl):S38–44.

4. Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks AG, et al. Durability of benefits of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention after discontinuation of audit and feedback. JAMA 2014;312:2569–70.

5. Steen S, Jaeger C, Price L, Griffen D. Increasing patient safety event reporting in an emergency medicine residency. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2017;6(1).

6. Fox M, Bump G, Butler G, et al. Making residents part of the safety culture: improving error reporting and reducing harms. J Patient Saf 2017. [Epub ahead of print]

7. Dunbar AE 3rd, Cupit M, Vath RJ, et al. An improvement approach to integrate teaching teams in the reporting of safety events. Pediatrics 2017;139:e20153807.

8. Institute of Medicine. To err is human: Building a safer health system. National Academies. www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/1999/To-Err-is-Human/To%20Err%20is%20Human%201999%20%20report%20brief.pdf Published November 1999. Accessed August 22, 2018.

9. Miller N, Bhowmik S, Ezinwa M, et al. The relationship between safety culture and voluntary event reporting in a large regional ambulatory care group. J Patient Saf 2017. [Epub ahead of print]

10. Neuspiel DR, Stubbs EH. Patient safety in ambulatory care. Pediatr Clin North Am 2012;59:1341–54.

11. West AM, Cardwell T, Clegg HW. Improving patient safety culture through patient safety coaches in the ambulatory setting. Presented at: Institute for Healthcare Improvement Annual Summit on Improving Patient Care in the Office Practice and the Community; March 2015; Dallas, Texas.

From Novant Health and Novant Health Medical Group, Winston-Salem, NC (Dr. C

Abstract

- Objective: An educational intervention stressing anonymous, voluntary safety event reporting together with monthly regular audit and feedback led to significantly increased reporting of safety events in a nonacademic, community practice setting during a 15-month intervention period. We assessed whether these increased reporting rates would be sustained during the 30-month period after the intervention was discontinued.

- Methods: We reviewed all patient safety events reported in our ambulatory clinics for the period 2012–2016, and selected 6 clinics that comprised the intervention collaborative and 18 specialty- and size-matched clinics (1:3 match) that comprised the comparator group. To test the changes in safety event reporting (SER) rates between the intervention and postintervention periods for the intervention collaborative, interrupted time series analysis with a control group was performed.

- Results: The SER rate peaked in the first month following the start of the intervention. Following discontinuation of regular auditing and feedback, reporting rates declined abruptly and reverted to baseline by 16 months post intervention.

- Conclusion: It is likely that sustaining enhanced reporting rates requires ongoing audit and feedback to maintain a focus on event reporting.

Keywords: patient safety; safety event reporting; voluntary reporting system; risk management; ambulatory clinic.

We have previously shown that patient safety reporting rates for a 6-practice collaborative group in our non-academic community clinics increased 10-fold after we implemented an improvement initiative consisting of an initial education session followed by provision of monthly audit and written and in-person feedback [1]. The intervention was implemented for 15 months, and after discontinuation of the intervention we have continued to monitor reporting rates. Our objective was to assess whether the increased reporting rates observed in this collaborative during the intervention period would be sustained for 30 months following the intervention.

Methods

This study’s methods have been described in detail previously [1]. For this improvement initiative, we reviewed all patient safety events reported in our ambulatory clinics for the period 2012–2016. We identified 6 clinics, the intervention collaborative, in family medicine (n = 3), pediatrics (n = 2), and general surgery (n = 1), and 18 specialty- and size-matched clinics (1:3 match), the comparator group [1]. For the intervention collaborative only, we provided an initial 1-hour educational session on safety events with a listing of all safety event types, along with a 1-page reporting form for voluntary, anonymous submission, with use of the term “safety event” rather than “ error,” to support a nonpunitive culture. After the educational session, we provided monthly audit and written and in-person feedback with peer comparison data by clinic. Monthly audit and feedback continued throughout the intervention and was discontinued postintervention. For event reporting, in our inpatient and outpatient facilities we used VIncident (Verge Solutions, Mt. Pleasant, SC) for the period 2012–2015 and RL6: Risk (RL Solutions, Toronto, ON) for 2016.

The baseline period was 15 months (January 2012–March 2013), the intervention period was 15 months (April 2013–June 2014), and the postintervention period was 30 months (July 2014–December 2016). All 24 clinics were monitored for the 60-month period.

To test the changes in the rate of safety event reporting (SER) between the pre-intervention and postintervention periods and between the intervention and the postintervention periods, interrupted time series (ITS) analysis with a control group was performed using PROC AUTOREG in SAS Enterprise Guide 6.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Because SER rates are reported monthly, ITS analysis was used to control for autocorrelation, nonstationary variance, seasonality, and trends [2,3].

Results

The SER rate was assessed monthly, so the number of SER rates for each group (intervention and comparator) was 15 during the pre-intervention and intervention periods, respectively, and 30 during the postintervention period. During the pre-intervention period, the intervention collaborative’s baseline median rate of safety events reported was 1.5 per 10,000 patient encounters (Figure). Also, for the intervention collaborative, the pre-intervention baseline mean (standard deviation, SD) SER rate (per 10,000 patient encounters by month) was 1.3 (1.2), the intervention mean SER rate was 12.0 (7.3), and the postintervention rate was 3.2 (1.8). Based on the ITS analysis, there was a significant change in the SER rate between the intervention and postintervention periods for the intervention collaborative (P = 0.01).

The SER rate peaked in the first month following the start of the intervention. After discontinuation of feedback, reporting rates declined abruptly and reverted to baseline by 16 months post intervention (Figure). The postintervention SER rate was also significantly higher than the pre-intervention rate (P = 0.001).

For the comparator clinics, no significant change in SER rates occurred for the 3 time periods.

Discussion

In this initiative with a 5-year reporting window, we had previously shown that with education and prospective audit and feedback, we could achieve a 10-fold increase in patient SER rates among a multi-practice collaborative while the intervention was maintained [1]. Even though there was a modest but significant increase in the SER rate in the postintervention period for the 6-clinic intervention collaborative compared to baseline, the substantial gains seen during the course of the intervention were not maintained when monthly audit and feedback ceased and monitoring continued for 30 months.

Limitations of this study include possible selection bias resulting from including clinics felt likely to participate rather than identifying clinics in a random fashion. In addition, we did not attempt to determine the specific reasons for the decrease in reporting among these clinics.

The few studies of ambulatory SER do not adequately address the effect of intervention cessation, but researchers who implemented other ambulatory quality improvement efforts have reported that gains often deteriorate or revert to baseline without consistent, ongoing feedback [4]. Likewise, in hospital-based residency programs, a multifaceted approach that includes feedback can increase SER rates, but it is uncertain if the success of this approach can be maintained long-term without continuing feedback of some type [5–7].

There are likely many factors influencing SER in ambulatory clinics, many of which are also applicable in the hospital setting. These include ease of reporting, knowing what events to report, confidentiality of reporting, and the belief that reporting makes a difference in enhancing patient safety [8]. A strong culture of safety in ambulatory clinics may lead to enhanced voluntary SER [9], and a nonpunitive, team-based approach has been advocated to promote reporting and improve ambulatory safety [10]. Historically, our ambulatory medical group clinics have had a strong culture of safety and, with patient safety coaches present in all of our clinics, we have supported a nonpunitive, team-based approach to SER [11].

In our intervention, we made reporting safety events easy, reporters knew which events to report, events could be reported anonymously, and reporters were rewarded, at least with data feedback, for reporting. The only factor known to have changed was discontinuation of monthly feedback. Which factors are most important could not be determined by our work, but we strongly suspect that sustaining enhanced reporting rates requires ongoing audit and feedback to maintain a focus on event reporting.

Corresponding author: Herbert Clegg, MD, 108 Providence Road, Charlotte NC, 28207, hwclegg@novanthealth.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

From Novant Health and Novant Health Medical Group, Winston-Salem, NC (Dr. C

Abstract

- Objective: An educational intervention stressing anonymous, voluntary safety event reporting together with monthly regular audit and feedback led to significantly increased reporting of safety events in a nonacademic, community practice setting during a 15-month intervention period. We assessed whether these increased reporting rates would be sustained during the 30-month period after the intervention was discontinued.

- Methods: We reviewed all patient safety events reported in our ambulatory clinics for the period 2012–2016, and selected 6 clinics that comprised the intervention collaborative and 18 specialty- and size-matched clinics (1:3 match) that comprised the comparator group. To test the changes in safety event reporting (SER) rates between the intervention and postintervention periods for the intervention collaborative, interrupted time series analysis with a control group was performed.

- Results: The SER rate peaked in the first month following the start of the intervention. Following discontinuation of regular auditing and feedback, reporting rates declined abruptly and reverted to baseline by 16 months post intervention.

- Conclusion: It is likely that sustaining enhanced reporting rates requires ongoing audit and feedback to maintain a focus on event reporting.

Keywords: patient safety; safety event reporting; voluntary reporting system; risk management; ambulatory clinic.

We have previously shown that patient safety reporting rates for a 6-practice collaborative group in our non-academic community clinics increased 10-fold after we implemented an improvement initiative consisting of an initial education session followed by provision of monthly audit and written and in-person feedback [1]. The intervention was implemented for 15 months, and after discontinuation of the intervention we have continued to monitor reporting rates. Our objective was to assess whether the increased reporting rates observed in this collaborative during the intervention period would be sustained for 30 months following the intervention.

Methods

This study’s methods have been described in detail previously [1]. For this improvement initiative, we reviewed all patient safety events reported in our ambulatory clinics for the period 2012–2016. We identified 6 clinics, the intervention collaborative, in family medicine (n = 3), pediatrics (n = 2), and general surgery (n = 1), and 18 specialty- and size-matched clinics (1:3 match), the comparator group [1]. For the intervention collaborative only, we provided an initial 1-hour educational session on safety events with a listing of all safety event types, along with a 1-page reporting form for voluntary, anonymous submission, with use of the term “safety event” rather than “ error,” to support a nonpunitive culture. After the educational session, we provided monthly audit and written and in-person feedback with peer comparison data by clinic. Monthly audit and feedback continued throughout the intervention and was discontinued postintervention. For event reporting, in our inpatient and outpatient facilities we used VIncident (Verge Solutions, Mt. Pleasant, SC) for the period 2012–2015 and RL6: Risk (RL Solutions, Toronto, ON) for 2016.

The baseline period was 15 months (January 2012–March 2013), the intervention period was 15 months (April 2013–June 2014), and the postintervention period was 30 months (July 2014–December 2016). All 24 clinics were monitored for the 60-month period.

To test the changes in the rate of safety event reporting (SER) between the pre-intervention and postintervention periods and between the intervention and the postintervention periods, interrupted time series (ITS) analysis with a control group was performed using PROC AUTOREG in SAS Enterprise Guide 6.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Because SER rates are reported monthly, ITS analysis was used to control for autocorrelation, nonstationary variance, seasonality, and trends [2,3].

Results

The SER rate was assessed monthly, so the number of SER rates for each group (intervention and comparator) was 15 during the pre-intervention and intervention periods, respectively, and 30 during the postintervention period. During the pre-intervention period, the intervention collaborative’s baseline median rate of safety events reported was 1.5 per 10,000 patient encounters (Figure). Also, for the intervention collaborative, the pre-intervention baseline mean (standard deviation, SD) SER rate (per 10,000 patient encounters by month) was 1.3 (1.2), the intervention mean SER rate was 12.0 (7.3), and the postintervention rate was 3.2 (1.8). Based on the ITS analysis, there was a significant change in the SER rate between the intervention and postintervention periods for the intervention collaborative (P = 0.01).

The SER rate peaked in the first month following the start of the intervention. After discontinuation of feedback, reporting rates declined abruptly and reverted to baseline by 16 months post intervention (Figure). The postintervention SER rate was also significantly higher than the pre-intervention rate (P = 0.001).

For the comparator clinics, no significant change in SER rates occurred for the 3 time periods.

Discussion

In this initiative with a 5-year reporting window, we had previously shown that with education and prospective audit and feedback, we could achieve a 10-fold increase in patient SER rates among a multi-practice collaborative while the intervention was maintained [1]. Even though there was a modest but significant increase in the SER rate in the postintervention period for the 6-clinic intervention collaborative compared to baseline, the substantial gains seen during the course of the intervention were not maintained when monthly audit and feedback ceased and monitoring continued for 30 months.

Limitations of this study include possible selection bias resulting from including clinics felt likely to participate rather than identifying clinics in a random fashion. In addition, we did not attempt to determine the specific reasons for the decrease in reporting among these clinics.

The few studies of ambulatory SER do not adequately address the effect of intervention cessation, but researchers who implemented other ambulatory quality improvement efforts have reported that gains often deteriorate or revert to baseline without consistent, ongoing feedback [4]. Likewise, in hospital-based residency programs, a multifaceted approach that includes feedback can increase SER rates, but it is uncertain if the success of this approach can be maintained long-term without continuing feedback of some type [5–7].

There are likely many factors influencing SER in ambulatory clinics, many of which are also applicable in the hospital setting. These include ease of reporting, knowing what events to report, confidentiality of reporting, and the belief that reporting makes a difference in enhancing patient safety [8]. A strong culture of safety in ambulatory clinics may lead to enhanced voluntary SER [9], and a nonpunitive, team-based approach has been advocated to promote reporting and improve ambulatory safety [10]. Historically, our ambulatory medical group clinics have had a strong culture of safety and, with patient safety coaches present in all of our clinics, we have supported a nonpunitive, team-based approach to SER [11].

In our intervention, we made reporting safety events easy, reporters knew which events to report, events could be reported anonymously, and reporters were rewarded, at least with data feedback, for reporting. The only factor known to have changed was discontinuation of monthly feedback. Which factors are most important could not be determined by our work, but we strongly suspect that sustaining enhanced reporting rates requires ongoing audit and feedback to maintain a focus on event reporting.

Corresponding author: Herbert Clegg, MD, 108 Providence Road, Charlotte NC, 28207, hwclegg@novanthealth.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Clegg HW, Cardwell T, West AM, Ferrell F. Improved safety event reporting in outpatient, nonacademic practices with an anonymous, nonpunitive approach. J Clin Outcomes Manag 2015;22:66–72.

2. Newland JG, Stach LM, De Lurgio SA, et al. Impact of a prospective-audit-with-feedback antimicrobial stewardship program at a children’s hospital. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2012; 1:179–86.

3. Penfold RB, Zhang F. Use of interrupted time series analysis in evaluating health care quality improvements. Acad Pediatr 2013;13 (6 Suppl):S38–44.

4. Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks AG, et al. Durability of benefits of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention after discontinuation of audit and feedback. JAMA 2014;312:2569–70.

5. Steen S, Jaeger C, Price L, Griffen D. Increasing patient safety event reporting in an emergency medicine residency. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2017;6(1).

6. Fox M, Bump G, Butler G, et al. Making residents part of the safety culture: improving error reporting and reducing harms. J Patient Saf 2017. [Epub ahead of print]

7. Dunbar AE 3rd, Cupit M, Vath RJ, et al. An improvement approach to integrate teaching teams in the reporting of safety events. Pediatrics 2017;139:e20153807.

8. Institute of Medicine. To err is human: Building a safer health system. National Academies. www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/1999/To-Err-is-Human/To%20Err%20is%20Human%201999%20%20report%20brief.pdf Published November 1999. Accessed August 22, 2018.

9. Miller N, Bhowmik S, Ezinwa M, et al. The relationship between safety culture and voluntary event reporting in a large regional ambulatory care group. J Patient Saf 2017. [Epub ahead of print]

10. Neuspiel DR, Stubbs EH. Patient safety in ambulatory care. Pediatr Clin North Am 2012;59:1341–54.

11. West AM, Cardwell T, Clegg HW. Improving patient safety culture through patient safety coaches in the ambulatory setting. Presented at: Institute for Healthcare Improvement Annual Summit on Improving Patient Care in the Office Practice and the Community; March 2015; Dallas, Texas.

1. Clegg HW, Cardwell T, West AM, Ferrell F. Improved safety event reporting in outpatient, nonacademic practices with an anonymous, nonpunitive approach. J Clin Outcomes Manag 2015;22:66–72.

2. Newland JG, Stach LM, De Lurgio SA, et al. Impact of a prospective-audit-with-feedback antimicrobial stewardship program at a children’s hospital. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2012; 1:179–86.

3. Penfold RB, Zhang F. Use of interrupted time series analysis in evaluating health care quality improvements. Acad Pediatr 2013;13 (6 Suppl):S38–44.

4. Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks AG, et al. Durability of benefits of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention after discontinuation of audit and feedback. JAMA 2014;312:2569–70.

5. Steen S, Jaeger C, Price L, Griffen D. Increasing patient safety event reporting in an emergency medicine residency. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2017;6(1).

6. Fox M, Bump G, Butler G, et al. Making residents part of the safety culture: improving error reporting and reducing harms. J Patient Saf 2017. [Epub ahead of print]

7. Dunbar AE 3rd, Cupit M, Vath RJ, et al. An improvement approach to integrate teaching teams in the reporting of safety events. Pediatrics 2017;139:e20153807.

8. Institute of Medicine. To err is human: Building a safer health system. National Academies. www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/1999/To-Err-is-Human/To%20Err%20is%20Human%201999%20%20report%20brief.pdf Published November 1999. Accessed August 22, 2018.

9. Miller N, Bhowmik S, Ezinwa M, et al. The relationship between safety culture and voluntary event reporting in a large regional ambulatory care group. J Patient Saf 2017. [Epub ahead of print]

10. Neuspiel DR, Stubbs EH. Patient safety in ambulatory care. Pediatr Clin North Am 2012;59:1341–54.

11. West AM, Cardwell T, Clegg HW. Improving patient safety culture through patient safety coaches in the ambulatory setting. Presented at: Institute for Healthcare Improvement Annual Summit on Improving Patient Care in the Office Practice and the Community; March 2015; Dallas, Texas.

Improved Safety Event Reporting in Outpatient, Nonacademic Practices with an Anonymous, Nonpunitive Approach

From Novant Health and Novant Health Medical Group, Winston-Salem, NC.

Abstract

- Objective: To evaluate the effect of an educational intervention with regular audit and feedback on reporting of patient safety events in a nonacademic, community practice setting with an established reporting system.

- Methods: A quasi-experimental with comparator design was used to compare a 6-practice collaborative group with a 27-practice comparator group with regard to safety event reporting rates. Baseline data were collected for a 12-month period followed by recruitment of 6 practices (3 family medicine, 2 pediatric, and 1 general surgery). An educational intervention was carried out with each, and this was followed by monthly audit and regular written and in-person feedback. Practice-level comparisons were made with specialty- and size-matched practices for the 6 practices in the collaborative group.

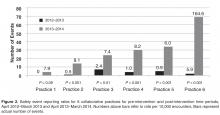

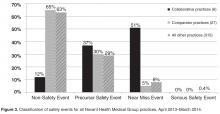

- Results: In the 12-month period following the intervention in March 2013, the 6 practices reported 175 patient safety events compared with only 19 events in the previous 12-month period. Each practice at least doubled reporting rates, and 5 of the 6 significantly increased rates. In contrast, rates for comparator practices were unchanged, with 84 events reported for the pre-intervention period and 81 for the post-intervention period. Event classification and types of events reported were different in the collaborative practices compared with the comparators for the post-intervention period. For the collaborative group, near miss events predominated as did diagnostic testing and communication event types.

- Conclusion: An initial educational session stressing anonymous, voluntary safety event reporting together with monthly audit and feedback and a focus on developing a nonpunitive environment can significantly enhance reporting of safety events.

Multiple challenges in the outpatient setting make establishing a culture of safety and improving care delivery more difficult than for inpatient settings. In the outpatient setting, care is often inaccessible, not well coordinated between providers and between facilities and providers, and delivered in many locations. It may also involve multiple sites and providers for a single patient, may require multiple visits in a single location, and can be provided by phone, email, mail, video, or in person [1]. Errors and adverse events may take long periods of time to become apparent and are more often errors of omission compared with those in the inpatient setting [2].

Incident reporting systems are considered important in improving patient safety [3], and their limitations and value have recently been reviewed [4]. However, limited research has been conducted on medical errors in ambulatory care, and even less is available on optimal monitoring and reporting strategies [5–12].Reporting in our system is time-consuming (about 15 minutes for entry of a single report), is not tailored for outpatient practices, may be considered potentially punitive (staff may believe that reporting may place themselves at risk for performance downgrade or other actions), and marked under-reporting of safety events was suspected. Most but not all of the suggested characteristics considered important for hospital-based reporting systems are fulfilled in our ambulatory reporting system [13].

Several academic groups have reported much improved reporting and a much better understanding of the types of errors occurring in their respective outpatient settings [14–16]. The most compelling model includes a voluntary, nonpunitive, anonymous reporting approach and a multidisciplinary practice-specific team to analyze reported errors and to enact change through a continuous quality improvement process [14,15].

We implemented a project to significantly improve reporting of safety events in an outpatient, nonacademic 6-practice collaborative by using education, monthly audit, and regular feedback.

Methods

Setting

Novant Health Medical Group is a consortium of over 380 clinic sites, nearly 1300 physicians, and over 500 advanced practice clinicians. Clinic locations are found in Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. Medical group members partner with physicians and staff in 15 hospitals in these geographic locations. Novant Health utilizes Epic (Epic Systems, Verona, WI) as an electronic health record. Safety event reporting is accomplished electronically in a single software program (VIncident, Verge Solutions, Mt. Pleasant, SC), used for all patients in our integrated care system (inpatient and outpatient facilities).

Intervention

Two of the authors (HWC and TC) met in March 2013 with the lead physician, practice manager, and patient safety coach at each clinic for approximately 1 hour. We discussed current reporting practice, delivered education for the safety event compendium, and detailed an anonymous, voluntary, and nonpunitive approach (stressing the use of the term “safety event” and not “error”) to reporting using a single page, 8-question paper report about the event. The report was not to be signed by the person completing the event data with placement in a drop box for later collection and electronic reporting as per usual practice in the clinic. We agreed that clinic leaders would stress to staff and providers that the initiative was nonpunitive and anonymous and that the goal was to report all known safety events, as an improvement project.

Patient safety coaches were selected for each of the 6 practices by the manager. Patient safety coaches are volunteer clinical or nonclinical staff members whose role is to observe, model, and reinforce pre-established patient safety behaviors and use of error prevention tools among peers and providers. Training requirements include an initial 2-hour training session in which they learn fundamentals of patient safety science, high reliability principles, coaching techniques for team accountability, and concepts for continuous quality improvement. Additionally, they attend monthly meetings where patient safety concepts are discussed in greater detail and best practices are shared. Following this training, each clinic’s staff was educated on the project, a process improvement team (lead physician, manager, and patient safety coach) was constituted, and the project was begun in April 2013. In quarter 3 of 2013, each practice team selected a quality improvement project based upon reported safety events in their clinic. We asked our medical group risk managers to continue event discussion with practice managers as usual, as each event is discussed briefly after a report is made.

We audited reports monthly and provided feedback to the practice team with a written report at the end of each 3-month period starting in June 2013 and ending in June 2014 (5 reports). Individual on-site visits to meet and discuss progress were completed in September 2013 and March 2014, in addition to the initial visit in March 2013.

Evaluation

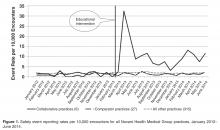

We compared reported monthly safety events for each of the 6 practices and for the 6-practice collaborative in the aggregate for the 12-month pre-intervention period (April 2012 through March 2013) and post-intervention period (April 2013 through March 2014). Each practice was compared with 3 specialty- and size (number of providers)-matched practices, none of whom received education or feedback on reporting or had patient safety coaches in the practice. In addition, for each of the 3 family medicine practices in the collaborative, we matched 1:3 other family medicine practices for specialty, size, and presence of a designated and trained patient safety coach. For the duration of the project, only 50 of 380 practices in the medical group had a trained patient safety coach.

The rate of safety events reported (ie, number of safety events reported/number of patient encounters) was compared for the 2 time periods using Poisson regression or zero-inflated Poisson regression. SASenterprise guide5.1 was used for all analyses. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The protocol was reviewed by the institutional review board of Novant Health Presbyterian Medical Center and a waiver for informed written consent was granted.

Results

To control for the presence of patient safety coaches in practices, the 3 family medicine clinics (clinics 4 through 6, Figure 2) were each matched 1:3 for size (number of providers) and specialty (other family medicine clinics), also with a patient safety coach. While the rates were significantly increased for the 3 collaborative family medicine clinics (P < 0.001), only 1 of the comparators clinic’s rate changed significantly (0.2 or 1/44,580 to 1.3 or 6/45,157), and this change was marginally significant (P = 0.048). This practice was the only one of the 27 comparator clinics to demonstrate any increased rate.

Discussion

In our nonacademic community practices, patient safety reporting rates improved following an initial educational session stressing anonymous, voluntary safety event reporting together with monthly audit and feedback. Our findings corroborate those of others in academic ambulatory settings, who found that an emphasis on patient safety reporting, particularly if an anonymous approach is taken in a nonpunitive atmosphere, can significantly increase the reporting of patient safety events [14–16]. We demonstrated marked under-reporting and stability of patient safety event reporting throughout our ambulatory practice group and a 10-fold increase in reporting among the 6-practice collaborative.

An unexpected finding was that with the exception of 1 practice, we found no increased reporting in comparator practices that had a patient safety coach. Additionally, we noted that general surgery practices report (or experience) very few ambulatory safety events, as a total of 4 events were reported for all 4 general surgery practices in 18 months.

We chose a quasi-experimental with a comparison group and pre-test/post-test design since randomization of practices was not feasible [17]. We used a 2-year period to control for any seasonal trends and to allow time after the intervention to see if meaningful improvement in reporting over time would continue. We attempted to address the potential for nonequivalence in the comparison group by matching for specialty and size of practice.

There are several limitations to this study. Bias in the selection of collaborative practices may have occurred since each had a proven leader, and this may have led to more rapid adoption and utilization of this reporting approach. Also, our findings may not be generalizable to other integrated health systems given the unique approaches to patient safety culture development and the disparate nature of reporting systems. In addition, with our study design we could not be certain that anonymous reporting was a key factor in the increase in reporting rates, but de-briefing interviews indicated that both anonymous reporting and declaring a nonpunitive, supportive approach in each practice was important to enhanced reporting.

We expect increased reporting to decline over time without consistent feedback, as has been demonstrated in other studies [18], and we will continue to monitor rates over time.

As our current reporting system requires considerable reporter time for data input and discussion with risk managers, is not specifically configured for ambulatory reporting, is considered by staff and providers potentially punitive, and marked under-reporting is clear, we have proposed moving to a new system that is more user-friendly, ambulatory-focused, and has a provision for anonymous reporting.

Presented in part at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement 15th Annual International Summit on Improving Patient Care in the Office Practice and the Community, Washington DC, March 2014.

Acknowledgements: We gratefully acknowledge the work of collaborative practice team members, including Christopher Isenhour MD, Janet White, Shelby Carlyle, Mark Tillotson MD, Maria Migliaccio, Melanie Trapp, Jennifer Ochs, Gary DeRosa MD, Margarete Hinkle, Scott Wagner, Kelly Schetselaar, Timothy Eichenbrenner MD, Sandy Hite, Jamie Shelton, Raymond Swetenburg MD, James Lye MD, Kelly Morrison, Jan Rapisardo, Jane Moss, Rhett Brown MD, Dorothy Hedrick, Camille Farmer, and William Anderson, MS, for assistance with analysis.

Corresponding author: Herbert Clegg, MD, 108 Providence Road, Charlotte NC, 28207, hwclegg@novanthealth.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Tang N, Meyer GS. Ambulatory patient safety: The time is now. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1487–9.

2. Ghandi TK, Lee TH. Patient safety beyond the hospital. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1001–3.

3. Institute of Medicine. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 1999.

4. Pham JC, Girard T, Pronovost PJ. What to do with healthcare incident reporting systems. J Public Health Res 2013;2:e27.

5. Elder NC, Dovey SM. Classification of medical errors and preventable adverse events in primary care: A synthesis of the literature. J Fam Pract 2002;51:927–32.

6. Mohr JJ, Lannon CM, Thoma KA, et al. Learning from errors in ambulatory pediatrics. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Marks ES, et al, editors. Advances in patient safety: from research to implementation. Washington, DC: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005: 355–68. Available at www.ahrq.gov//downloads/pub/advances/vol1/Mohr.pdf.

7. Phillips RL, Dovey SM, Graham D, et al. Learning from different lenses: reports of medical errors in primary care by clinicians, staff, and patients. J Patient Saf 2006;2:140–6.

8. Singh H, Thomas EJ, Khan MM, Peterson LA. Identifying diagnostic errors in primary care using an electronic screening algorithm. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:302–8.

9. Rappaport DI, Collins B, Koster A, et al. Implementing medication reconciliation in outpatient pediatrics. Pediatrics 2011;128:e1600-e1607.

10. Bishop TF, Ryan AK, Casalino LP. Paid malpractice claims for adverse events in inpatient and outpatient settings. JAMA 2011;305:2427–31.

11. Wynia MK, Classen DC. Improving ambulatory patient safety. Learning from the last decade, moving ahead in the next. JAMA 2011;306:2504–5.

12. Neuspiel DR, Stubbs EH. Patient safety in ambulatory care. Pediatr Clin North Am 2012;59:1341–54.

13. Leape LL. Patient safety. Reporting of adverse events. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1633–8.

14. Neuspiel DR, Stubbs EH, Liggin L. Improving reporting of outpatient medical errors. Pediatrics 2011;128:e1608–e1613.

15. Neuspiel DR, Gizman M, Harewood C. Improving error reporting in ambulatory pediatrics with team approach. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, et al, editors. Advances in patient safety: new directions and alternative approaches. Vol 1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. Available at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK43643/.

16. Plews-Ogan ML, Nadkarni MM, Forren S, et al. Patient safety in the ambulatory setting: a clinician-based approach. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:719–25.

17. Harris AD, McGregor JC, Perencevich EN, et al. The use and interpretation of quasi-experimental studies in medical informatics. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2006;13:16–23.

18. Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks AG, et al. Durability of benefits of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention after discontinuation of audit and feedback. JAMA 2014;312:2569–70.

From Novant Health and Novant Health Medical Group, Winston-Salem, NC.

Abstract

- Objective: To evaluate the effect of an educational intervention with regular audit and feedback on reporting of patient safety events in a nonacademic, community practice setting with an established reporting system.

- Methods: A quasi-experimental with comparator design was used to compare a 6-practice collaborative group with a 27-practice comparator group with regard to safety event reporting rates. Baseline data were collected for a 12-month period followed by recruitment of 6 practices (3 family medicine, 2 pediatric, and 1 general surgery). An educational intervention was carried out with each, and this was followed by monthly audit and regular written and in-person feedback. Practice-level comparisons were made with specialty- and size-matched practices for the 6 practices in the collaborative group.

- Results: In the 12-month period following the intervention in March 2013, the 6 practices reported 175 patient safety events compared with only 19 events in the previous 12-month period. Each practice at least doubled reporting rates, and 5 of the 6 significantly increased rates. In contrast, rates for comparator practices were unchanged, with 84 events reported for the pre-intervention period and 81 for the post-intervention period. Event classification and types of events reported were different in the collaborative practices compared with the comparators for the post-intervention period. For the collaborative group, near miss events predominated as did diagnostic testing and communication event types.

- Conclusion: An initial educational session stressing anonymous, voluntary safety event reporting together with monthly audit and feedback and a focus on developing a nonpunitive environment can significantly enhance reporting of safety events.

Multiple challenges in the outpatient setting make establishing a culture of safety and improving care delivery more difficult than for inpatient settings. In the outpatient setting, care is often inaccessible, not well coordinated between providers and between facilities and providers, and delivered in many locations. It may also involve multiple sites and providers for a single patient, may require multiple visits in a single location, and can be provided by phone, email, mail, video, or in person [1]. Errors and adverse events may take long periods of time to become apparent and are more often errors of omission compared with those in the inpatient setting [2].

Incident reporting systems are considered important in improving patient safety [3], and their limitations and value have recently been reviewed [4]. However, limited research has been conducted on medical errors in ambulatory care, and even less is available on optimal monitoring and reporting strategies [5–12].Reporting in our system is time-consuming (about 15 minutes for entry of a single report), is not tailored for outpatient practices, may be considered potentially punitive (staff may believe that reporting may place themselves at risk for performance downgrade or other actions), and marked under-reporting of safety events was suspected. Most but not all of the suggested characteristics considered important for hospital-based reporting systems are fulfilled in our ambulatory reporting system [13].

Several academic groups have reported much improved reporting and a much better understanding of the types of errors occurring in their respective outpatient settings [14–16]. The most compelling model includes a voluntary, nonpunitive, anonymous reporting approach and a multidisciplinary practice-specific team to analyze reported errors and to enact change through a continuous quality improvement process [14,15].

We implemented a project to significantly improve reporting of safety events in an outpatient, nonacademic 6-practice collaborative by using education, monthly audit, and regular feedback.

Methods

Setting

Novant Health Medical Group is a consortium of over 380 clinic sites, nearly 1300 physicians, and over 500 advanced practice clinicians. Clinic locations are found in Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. Medical group members partner with physicians and staff in 15 hospitals in these geographic locations. Novant Health utilizes Epic (Epic Systems, Verona, WI) as an electronic health record. Safety event reporting is accomplished electronically in a single software program (VIncident, Verge Solutions, Mt. Pleasant, SC), used for all patients in our integrated care system (inpatient and outpatient facilities).

Intervention

Two of the authors (HWC and TC) met in March 2013 with the lead physician, practice manager, and patient safety coach at each clinic for approximately 1 hour. We discussed current reporting practice, delivered education for the safety event compendium, and detailed an anonymous, voluntary, and nonpunitive approach (stressing the use of the term “safety event” and not “error”) to reporting using a single page, 8-question paper report about the event. The report was not to be signed by the person completing the event data with placement in a drop box for later collection and electronic reporting as per usual practice in the clinic. We agreed that clinic leaders would stress to staff and providers that the initiative was nonpunitive and anonymous and that the goal was to report all known safety events, as an improvement project.

Patient safety coaches were selected for each of the 6 practices by the manager. Patient safety coaches are volunteer clinical or nonclinical staff members whose role is to observe, model, and reinforce pre-established patient safety behaviors and use of error prevention tools among peers and providers. Training requirements include an initial 2-hour training session in which they learn fundamentals of patient safety science, high reliability principles, coaching techniques for team accountability, and concepts for continuous quality improvement. Additionally, they attend monthly meetings where patient safety concepts are discussed in greater detail and best practices are shared. Following this training, each clinic’s staff was educated on the project, a process improvement team (lead physician, manager, and patient safety coach) was constituted, and the project was begun in April 2013. In quarter 3 of 2013, each practice team selected a quality improvement project based upon reported safety events in their clinic. We asked our medical group risk managers to continue event discussion with practice managers as usual, as each event is discussed briefly after a report is made.

We audited reports monthly and provided feedback to the practice team with a written report at the end of each 3-month period starting in June 2013 and ending in June 2014 (5 reports). Individual on-site visits to meet and discuss progress were completed in September 2013 and March 2014, in addition to the initial visit in March 2013.

Evaluation

We compared reported monthly safety events for each of the 6 practices and for the 6-practice collaborative in the aggregate for the 12-month pre-intervention period (April 2012 through March 2013) and post-intervention period (April 2013 through March 2014). Each practice was compared with 3 specialty- and size (number of providers)-matched practices, none of whom received education or feedback on reporting or had patient safety coaches in the practice. In addition, for each of the 3 family medicine practices in the collaborative, we matched 1:3 other family medicine practices for specialty, size, and presence of a designated and trained patient safety coach. For the duration of the project, only 50 of 380 practices in the medical group had a trained patient safety coach.

The rate of safety events reported (ie, number of safety events reported/number of patient encounters) was compared for the 2 time periods using Poisson regression or zero-inflated Poisson regression. SASenterprise guide5.1 was used for all analyses. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The protocol was reviewed by the institutional review board of Novant Health Presbyterian Medical Center and a waiver for informed written consent was granted.

Results

To control for the presence of patient safety coaches in practices, the 3 family medicine clinics (clinics 4 through 6, Figure 2) were each matched 1:3 for size (number of providers) and specialty (other family medicine clinics), also with a patient safety coach. While the rates were significantly increased for the 3 collaborative family medicine clinics (P < 0.001), only 1 of the comparators clinic’s rate changed significantly (0.2 or 1/44,580 to 1.3 or 6/45,157), and this change was marginally significant (P = 0.048). This practice was the only one of the 27 comparator clinics to demonstrate any increased rate.

Discussion

In our nonacademic community practices, patient safety reporting rates improved following an initial educational session stressing anonymous, voluntary safety event reporting together with monthly audit and feedback. Our findings corroborate those of others in academic ambulatory settings, who found that an emphasis on patient safety reporting, particularly if an anonymous approach is taken in a nonpunitive atmosphere, can significantly increase the reporting of patient safety events [14–16]. We demonstrated marked under-reporting and stability of patient safety event reporting throughout our ambulatory practice group and a 10-fold increase in reporting among the 6-practice collaborative.

An unexpected finding was that with the exception of 1 practice, we found no increased reporting in comparator practices that had a patient safety coach. Additionally, we noted that general surgery practices report (or experience) very few ambulatory safety events, as a total of 4 events were reported for all 4 general surgery practices in 18 months.

We chose a quasi-experimental with a comparison group and pre-test/post-test design since randomization of practices was not feasible [17]. We used a 2-year period to control for any seasonal trends and to allow time after the intervention to see if meaningful improvement in reporting over time would continue. We attempted to address the potential for nonequivalence in the comparison group by matching for specialty and size of practice.

There are several limitations to this study. Bias in the selection of collaborative practices may have occurred since each had a proven leader, and this may have led to more rapid adoption and utilization of this reporting approach. Also, our findings may not be generalizable to other integrated health systems given the unique approaches to patient safety culture development and the disparate nature of reporting systems. In addition, with our study design we could not be certain that anonymous reporting was a key factor in the increase in reporting rates, but de-briefing interviews indicated that both anonymous reporting and declaring a nonpunitive, supportive approach in each practice was important to enhanced reporting.

We expect increased reporting to decline over time without consistent feedback, as has been demonstrated in other studies [18], and we will continue to monitor rates over time.

As our current reporting system requires considerable reporter time for data input and discussion with risk managers, is not specifically configured for ambulatory reporting, is considered by staff and providers potentially punitive, and marked under-reporting is clear, we have proposed moving to a new system that is more user-friendly, ambulatory-focused, and has a provision for anonymous reporting.

Presented in part at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement 15th Annual International Summit on Improving Patient Care in the Office Practice and the Community, Washington DC, March 2014.

Acknowledgements: We gratefully acknowledge the work of collaborative practice team members, including Christopher Isenhour MD, Janet White, Shelby Carlyle, Mark Tillotson MD, Maria Migliaccio, Melanie Trapp, Jennifer Ochs, Gary DeRosa MD, Margarete Hinkle, Scott Wagner, Kelly Schetselaar, Timothy Eichenbrenner MD, Sandy Hite, Jamie Shelton, Raymond Swetenburg MD, James Lye MD, Kelly Morrison, Jan Rapisardo, Jane Moss, Rhett Brown MD, Dorothy Hedrick, Camille Farmer, and William Anderson, MS, for assistance with analysis.

Corresponding author: Herbert Clegg, MD, 108 Providence Road, Charlotte NC, 28207, hwclegg@novanthealth.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

From Novant Health and Novant Health Medical Group, Winston-Salem, NC.

Abstract

- Objective: To evaluate the effect of an educational intervention with regular audit and feedback on reporting of patient safety events in a nonacademic, community practice setting with an established reporting system.

- Methods: A quasi-experimental with comparator design was used to compare a 6-practice collaborative group with a 27-practice comparator group with regard to safety event reporting rates. Baseline data were collected for a 12-month period followed by recruitment of 6 practices (3 family medicine, 2 pediatric, and 1 general surgery). An educational intervention was carried out with each, and this was followed by monthly audit and regular written and in-person feedback. Practice-level comparisons were made with specialty- and size-matched practices for the 6 practices in the collaborative group.

- Results: In the 12-month period following the intervention in March 2013, the 6 practices reported 175 patient safety events compared with only 19 events in the previous 12-month period. Each practice at least doubled reporting rates, and 5 of the 6 significantly increased rates. In contrast, rates for comparator practices were unchanged, with 84 events reported for the pre-intervention period and 81 for the post-intervention period. Event classification and types of events reported were different in the collaborative practices compared with the comparators for the post-intervention period. For the collaborative group, near miss events predominated as did diagnostic testing and communication event types.

- Conclusion: An initial educational session stressing anonymous, voluntary safety event reporting together with monthly audit and feedback and a focus on developing a nonpunitive environment can significantly enhance reporting of safety events.

Multiple challenges in the outpatient setting make establishing a culture of safety and improving care delivery more difficult than for inpatient settings. In the outpatient setting, care is often inaccessible, not well coordinated between providers and between facilities and providers, and delivered in many locations. It may also involve multiple sites and providers for a single patient, may require multiple visits in a single location, and can be provided by phone, email, mail, video, or in person [1]. Errors and adverse events may take long periods of time to become apparent and are more often errors of omission compared with those in the inpatient setting [2].

Incident reporting systems are considered important in improving patient safety [3], and their limitations and value have recently been reviewed [4]. However, limited research has been conducted on medical errors in ambulatory care, and even less is available on optimal monitoring and reporting strategies [5–12].Reporting in our system is time-consuming (about 15 minutes for entry of a single report), is not tailored for outpatient practices, may be considered potentially punitive (staff may believe that reporting may place themselves at risk for performance downgrade or other actions), and marked under-reporting of safety events was suspected. Most but not all of the suggested characteristics considered important for hospital-based reporting systems are fulfilled in our ambulatory reporting system [13].

Several academic groups have reported much improved reporting and a much better understanding of the types of errors occurring in their respective outpatient settings [14–16]. The most compelling model includes a voluntary, nonpunitive, anonymous reporting approach and a multidisciplinary practice-specific team to analyze reported errors and to enact change through a continuous quality improvement process [14,15].

We implemented a project to significantly improve reporting of safety events in an outpatient, nonacademic 6-practice collaborative by using education, monthly audit, and regular feedback.

Methods

Setting

Novant Health Medical Group is a consortium of over 380 clinic sites, nearly 1300 physicians, and over 500 advanced practice clinicians. Clinic locations are found in Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. Medical group members partner with physicians and staff in 15 hospitals in these geographic locations. Novant Health utilizes Epic (Epic Systems, Verona, WI) as an electronic health record. Safety event reporting is accomplished electronically in a single software program (VIncident, Verge Solutions, Mt. Pleasant, SC), used for all patients in our integrated care system (inpatient and outpatient facilities).

Intervention

Two of the authors (HWC and TC) met in March 2013 with the lead physician, practice manager, and patient safety coach at each clinic for approximately 1 hour. We discussed current reporting practice, delivered education for the safety event compendium, and detailed an anonymous, voluntary, and nonpunitive approach (stressing the use of the term “safety event” and not “error”) to reporting using a single page, 8-question paper report about the event. The report was not to be signed by the person completing the event data with placement in a drop box for later collection and electronic reporting as per usual practice in the clinic. We agreed that clinic leaders would stress to staff and providers that the initiative was nonpunitive and anonymous and that the goal was to report all known safety events, as an improvement project.

Patient safety coaches were selected for each of the 6 practices by the manager. Patient safety coaches are volunteer clinical or nonclinical staff members whose role is to observe, model, and reinforce pre-established patient safety behaviors and use of error prevention tools among peers and providers. Training requirements include an initial 2-hour training session in which they learn fundamentals of patient safety science, high reliability principles, coaching techniques for team accountability, and concepts for continuous quality improvement. Additionally, they attend monthly meetings where patient safety concepts are discussed in greater detail and best practices are shared. Following this training, each clinic’s staff was educated on the project, a process improvement team (lead physician, manager, and patient safety coach) was constituted, and the project was begun in April 2013. In quarter 3 of 2013, each practice team selected a quality improvement project based upon reported safety events in their clinic. We asked our medical group risk managers to continue event discussion with practice managers as usual, as each event is discussed briefly after a report is made.

We audited reports monthly and provided feedback to the practice team with a written report at the end of each 3-month period starting in June 2013 and ending in June 2014 (5 reports). Individual on-site visits to meet and discuss progress were completed in September 2013 and March 2014, in addition to the initial visit in March 2013.

Evaluation

We compared reported monthly safety events for each of the 6 practices and for the 6-practice collaborative in the aggregate for the 12-month pre-intervention period (April 2012 through March 2013) and post-intervention period (April 2013 through March 2014). Each practice was compared with 3 specialty- and size (number of providers)-matched practices, none of whom received education or feedback on reporting or had patient safety coaches in the practice. In addition, for each of the 3 family medicine practices in the collaborative, we matched 1:3 other family medicine practices for specialty, size, and presence of a designated and trained patient safety coach. For the duration of the project, only 50 of 380 practices in the medical group had a trained patient safety coach.

The rate of safety events reported (ie, number of safety events reported/number of patient encounters) was compared for the 2 time periods using Poisson regression or zero-inflated Poisson regression. SASenterprise guide5.1 was used for all analyses. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The protocol was reviewed by the institutional review board of Novant Health Presbyterian Medical Center and a waiver for informed written consent was granted.

Results

To control for the presence of patient safety coaches in practices, the 3 family medicine clinics (clinics 4 through 6, Figure 2) were each matched 1:3 for size (number of providers) and specialty (other family medicine clinics), also with a patient safety coach. While the rates were significantly increased for the 3 collaborative family medicine clinics (P < 0.001), only 1 of the comparators clinic’s rate changed significantly (0.2 or 1/44,580 to 1.3 or 6/45,157), and this change was marginally significant (P = 0.048). This practice was the only one of the 27 comparator clinics to demonstrate any increased rate.

Discussion

In our nonacademic community practices, patient safety reporting rates improved following an initial educational session stressing anonymous, voluntary safety event reporting together with monthly audit and feedback. Our findings corroborate those of others in academic ambulatory settings, who found that an emphasis on patient safety reporting, particularly if an anonymous approach is taken in a nonpunitive atmosphere, can significantly increase the reporting of patient safety events [14–16]. We demonstrated marked under-reporting and stability of patient safety event reporting throughout our ambulatory practice group and a 10-fold increase in reporting among the 6-practice collaborative.

An unexpected finding was that with the exception of 1 practice, we found no increased reporting in comparator practices that had a patient safety coach. Additionally, we noted that general surgery practices report (or experience) very few ambulatory safety events, as a total of 4 events were reported for all 4 general surgery practices in 18 months.

We chose a quasi-experimental with a comparison group and pre-test/post-test design since randomization of practices was not feasible [17]. We used a 2-year period to control for any seasonal trends and to allow time after the intervention to see if meaningful improvement in reporting over time would continue. We attempted to address the potential for nonequivalence in the comparison group by matching for specialty and size of practice.

There are several limitations to this study. Bias in the selection of collaborative practices may have occurred since each had a proven leader, and this may have led to more rapid adoption and utilization of this reporting approach. Also, our findings may not be generalizable to other integrated health systems given the unique approaches to patient safety culture development and the disparate nature of reporting systems. In addition, with our study design we could not be certain that anonymous reporting was a key factor in the increase in reporting rates, but de-briefing interviews indicated that both anonymous reporting and declaring a nonpunitive, supportive approach in each practice was important to enhanced reporting.

We expect increased reporting to decline over time without consistent feedback, as has been demonstrated in other studies [18], and we will continue to monitor rates over time.

As our current reporting system requires considerable reporter time for data input and discussion with risk managers, is not specifically configured for ambulatory reporting, is considered by staff and providers potentially punitive, and marked under-reporting is clear, we have proposed moving to a new system that is more user-friendly, ambulatory-focused, and has a provision for anonymous reporting.

Presented in part at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement 15th Annual International Summit on Improving Patient Care in the Office Practice and the Community, Washington DC, March 2014.

Acknowledgements: We gratefully acknowledge the work of collaborative practice team members, including Christopher Isenhour MD, Janet White, Shelby Carlyle, Mark Tillotson MD, Maria Migliaccio, Melanie Trapp, Jennifer Ochs, Gary DeRosa MD, Margarete Hinkle, Scott Wagner, Kelly Schetselaar, Timothy Eichenbrenner MD, Sandy Hite, Jamie Shelton, Raymond Swetenburg MD, James Lye MD, Kelly Morrison, Jan Rapisardo, Jane Moss, Rhett Brown MD, Dorothy Hedrick, Camille Farmer, and William Anderson, MS, for assistance with analysis.

Corresponding author: Herbert Clegg, MD, 108 Providence Road, Charlotte NC, 28207, hwclegg@novanthealth.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Tang N, Meyer GS. Ambulatory patient safety: The time is now. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1487–9.

2. Ghandi TK, Lee TH. Patient safety beyond the hospital. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1001–3.

3. Institute of Medicine. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 1999.

4. Pham JC, Girard T, Pronovost PJ. What to do with healthcare incident reporting systems. J Public Health Res 2013;2:e27.

5. Elder NC, Dovey SM. Classification of medical errors and preventable adverse events in primary care: A synthesis of the literature. J Fam Pract 2002;51:927–32.

6. Mohr JJ, Lannon CM, Thoma KA, et al. Learning from errors in ambulatory pediatrics. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Marks ES, et al, editors. Advances in patient safety: from research to implementation. Washington, DC: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005: 355–68. Available at www.ahrq.gov//downloads/pub/advances/vol1/Mohr.pdf.

7. Phillips RL, Dovey SM, Graham D, et al. Learning from different lenses: reports of medical errors in primary care by clinicians, staff, and patients. J Patient Saf 2006;2:140–6.

8. Singh H, Thomas EJ, Khan MM, Peterson LA. Identifying diagnostic errors in primary care using an electronic screening algorithm. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:302–8.

9. Rappaport DI, Collins B, Koster A, et al. Implementing medication reconciliation in outpatient pediatrics. Pediatrics 2011;128:e1600-e1607.

10. Bishop TF, Ryan AK, Casalino LP. Paid malpractice claims for adverse events in inpatient and outpatient settings. JAMA 2011;305:2427–31.

11. Wynia MK, Classen DC. Improving ambulatory patient safety. Learning from the last decade, moving ahead in the next. JAMA 2011;306:2504–5.

12. Neuspiel DR, Stubbs EH. Patient safety in ambulatory care. Pediatr Clin North Am 2012;59:1341–54.

13. Leape LL. Patient safety. Reporting of adverse events. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1633–8.

14. Neuspiel DR, Stubbs EH, Liggin L. Improving reporting of outpatient medical errors. Pediatrics 2011;128:e1608–e1613.

15. Neuspiel DR, Gizman M, Harewood C. Improving error reporting in ambulatory pediatrics with team approach. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, et al, editors. Advances in patient safety: new directions and alternative approaches. Vol 1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. Available at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK43643/.

16. Plews-Ogan ML, Nadkarni MM, Forren S, et al. Patient safety in the ambulatory setting: a clinician-based approach. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:719–25.

17. Harris AD, McGregor JC, Perencevich EN, et al. The use and interpretation of quasi-experimental studies in medical informatics. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2006;13:16–23.

18. Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks AG, et al. Durability of benefits of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention after discontinuation of audit and feedback. JAMA 2014;312:2569–70.

1. Tang N, Meyer GS. Ambulatory patient safety: The time is now. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1487–9.

2. Ghandi TK, Lee TH. Patient safety beyond the hospital. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1001–3.

3. Institute of Medicine. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 1999.

4. Pham JC, Girard T, Pronovost PJ. What to do with healthcare incident reporting systems. J Public Health Res 2013;2:e27.

5. Elder NC, Dovey SM. Classification of medical errors and preventable adverse events in primary care: A synthesis of the literature. J Fam Pract 2002;51:927–32.

6. Mohr JJ, Lannon CM, Thoma KA, et al. Learning from errors in ambulatory pediatrics. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Marks ES, et al, editors. Advances in patient safety: from research to implementation. Washington, DC: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005: 355–68. Available at www.ahrq.gov//downloads/pub/advances/vol1/Mohr.pdf.

7. Phillips RL, Dovey SM, Graham D, et al. Learning from different lenses: reports of medical errors in primary care by clinicians, staff, and patients. J Patient Saf 2006;2:140–6.

8. Singh H, Thomas EJ, Khan MM, Peterson LA. Identifying diagnostic errors in primary care using an electronic screening algorithm. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:302–8.

9. Rappaport DI, Collins B, Koster A, et al. Implementing medication reconciliation in outpatient pediatrics. Pediatrics 2011;128:e1600-e1607.

10. Bishop TF, Ryan AK, Casalino LP. Paid malpractice claims for adverse events in inpatient and outpatient settings. JAMA 2011;305:2427–31.

11. Wynia MK, Classen DC. Improving ambulatory patient safety. Learning from the last decade, moving ahead in the next. JAMA 2011;306:2504–5.

12. Neuspiel DR, Stubbs EH. Patient safety in ambulatory care. Pediatr Clin North Am 2012;59:1341–54.

13. Leape LL. Patient safety. Reporting of adverse events. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1633–8.

14. Neuspiel DR, Stubbs EH, Liggin L. Improving reporting of outpatient medical errors. Pediatrics 2011;128:e1608–e1613.

15. Neuspiel DR, Gizman M, Harewood C. Improving error reporting in ambulatory pediatrics with team approach. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, et al, editors. Advances in patient safety: new directions and alternative approaches. Vol 1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. Available at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK43643/.

16. Plews-Ogan ML, Nadkarni MM, Forren S, et al. Patient safety in the ambulatory setting: a clinician-based approach. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:719–25.

17. Harris AD, McGregor JC, Perencevich EN, et al. The use and interpretation of quasi-experimental studies in medical informatics. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2006;13:16–23.

18. Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks AG, et al. Durability of benefits of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention after discontinuation of audit and feedback. JAMA 2014;312:2569–70.