User login

JNC 8: Not So Great?

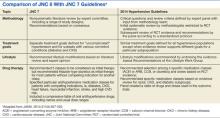

The previous set of official recommendations for hypertension management was published way back in 2003. So the practice community has waited very patiently for an updated set of guidelines. The previous guidelines were known as JNC 7, referring to the seventh iteration of recommendations emanating from a group of big-time hypertension experts known as the Joint National Committee (JNC). All the JNC reports have been sponsored by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and hence, had a high degree of visibility and credibility. However, many practitioners felt that cost considerations mitigating in favor of inexpensive drugs, such as thiazide diuretics, unfairly colored and distorted the JNC 7 recommendations.

In the interest of full disclosure, I should point out that I was one of the many Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) investigators who produced an influential study result that indeed seemed to favor diuretics over the newer and more expensive antihypertensive therapies. So JNC 7 was received with some suspicion that saving money might have taken precedence over optimal therapeutic management.

Many new studies relevant to hypertension goals and preferred antihypertensive therapies have come out in the years since JNC 7 first appeared. So there was a lot of anticipation that these more recent studies would inform and modify some of the existing JNC recommendations. This sort of speculation was all very fair and reasonable. But then something quite unanticipated happened. The JNC 8 experts met and discussed recommendations, but no guidelines emerged. Literally, years went by, and the recommendations that were expected as JNC 8 instead became known as JNC Wait and then JNC Late.

Then the NIH decided that it didn’t want to be in the guideline-issuing business any longer. The NIH outsourced its lipid guidelines, which had previously been known as the NCEP (National Cholesterol Education Panel) recommendations, to a joint committee of the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology. The hypertension experts who had met as the JNC 8 group were similarly cut loose from formal NIH sponsorship. This action was not because the NIH was unhappy with their work, but rather because the NIH had simply decided that it no longer wanted to sponsor any clinical recommendations of any sort.

So what to do? Having finally reached consensus after years of meetings, the JNC 8 experts found themselves without an official sponsor. So they decided to take a page from rock star Prince’s playbook, and they published their recommendations as “the Panel Members Appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee.” This move was a bit awkward, to say the least, but it was certainly preferable to leaving the fruits of their extensive labors unavailable to the practice community.

Apart from all these distractions, what has generated the most controversy has been the actual guidelines for the management of patients with hypertension who are aged 60 years or older. This is a pretty sizable chunk of the total population with hypertension, since the prevalence of elevated blood pressure increases dramatically with age. And this is also the population whose consequences of inadequately controlled hypertension are the most severe. The majority of strokes occur in those over the age of 60, as do most of the myocardial infarctions and cases of new-onset heart failure.

This group truly has a lot at stake when it comes to hypertension control or lack thereof. And I have to tell you, it’s a group I identify with. I saw 60 in the rearview mirror several years back, and I’ve been on antihypertensive therapy since my late thirties. Consequently, I am following this discussion very closely for both professional and personal reasons.

The JNC 8 authors recommended against initiating antihypertensive therapy in patients over the age of 60 unless their blood pressure was over 150/90 mm Hg, which represents a loosening of the earlier recommendations to start drug treatment at the lower systolic level of 140 mm Hg. Also, the new goal for antihypertensive therapy in this age group is simply to achieve a systolic pressure of ≤ 150 mm Hg, instead of the previous goal of under 140 mm Hg.

I am of two minds about this relaxation of the blood pressure goals. On the one hand, I acknowledge that the recommendations are evidence based, at least in the sense that no incontrovertible data exist to refute this more relaxed goal. There are simply not any credible studies out there that demonstrate better results when the systolic goal is 140 mm Hg rather than 150 mm Hg. It doesn’t mean that it might not be true—140 might really be better than 150—it simply means that the issue has not been studied in any clinical trial. So from a purist, evidence-based standpoint, I can accept that the new recommendation is perfectly valid from a scientific point of view.

But the part of me that values the art of medicine as well as the science is profoundly troubled by this lockstep scientific purity. What I am extremely concerned about is the possibility that the practice community will misinterpret the recommendations and take them as a mandate to loosen blood pressure control in those over age 60. If the target is just to get the systolic below 150 mm Hg, some may conclude that a pressure of 160 or even 165 is “close enough for government work,” to use the convenient phrase that dogs us federal employees. This would be a misinterpretation of the guidelines’ actual recommendation, but nonetheless, a very understandable and almost predictable one. Given that the practice community has never done a bang-up job of getting patients to the goals previously recommended, is it really the time to relax those guidelines and run the risk of even less blood pressure control?

I have to reluctantly conclude that the pseudo JNC 8 guidelines are not so great, at least for hypertensive patients over age 60. Although I cannot quibble with the strict scientific underpinning of the guidelines, they seem very likely to lead to a setback in hypertension control. We may see more heart attacks, strokes, heart failure, and renal failure if practitioners take the new guidelines as license to be less vigilant in treating elevated blood pressure. Treating elevated blood pressure is the low-hanging fruit for most primary care providers, and discouraging them from plucking that fruit from the tree is clearly a step in the wrong direction.

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

The previous set of official recommendations for hypertension management was published way back in 2003. So the practice community has waited very patiently for an updated set of guidelines. The previous guidelines were known as JNC 7, referring to the seventh iteration of recommendations emanating from a group of big-time hypertension experts known as the Joint National Committee (JNC). All the JNC reports have been sponsored by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and hence, had a high degree of visibility and credibility. However, many practitioners felt that cost considerations mitigating in favor of inexpensive drugs, such as thiazide diuretics, unfairly colored and distorted the JNC 7 recommendations.

In the interest of full disclosure, I should point out that I was one of the many Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) investigators who produced an influential study result that indeed seemed to favor diuretics over the newer and more expensive antihypertensive therapies. So JNC 7 was received with some suspicion that saving money might have taken precedence over optimal therapeutic management.

Many new studies relevant to hypertension goals and preferred antihypertensive therapies have come out in the years since JNC 7 first appeared. So there was a lot of anticipation that these more recent studies would inform and modify some of the existing JNC recommendations. This sort of speculation was all very fair and reasonable. But then something quite unanticipated happened. The JNC 8 experts met and discussed recommendations, but no guidelines emerged. Literally, years went by, and the recommendations that were expected as JNC 8 instead became known as JNC Wait and then JNC Late.

Then the NIH decided that it didn’t want to be in the guideline-issuing business any longer. The NIH outsourced its lipid guidelines, which had previously been known as the NCEP (National Cholesterol Education Panel) recommendations, to a joint committee of the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology. The hypertension experts who had met as the JNC 8 group were similarly cut loose from formal NIH sponsorship. This action was not because the NIH was unhappy with their work, but rather because the NIH had simply decided that it no longer wanted to sponsor any clinical recommendations of any sort.

So what to do? Having finally reached consensus after years of meetings, the JNC 8 experts found themselves without an official sponsor. So they decided to take a page from rock star Prince’s playbook, and they published their recommendations as “the Panel Members Appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee.” This move was a bit awkward, to say the least, but it was certainly preferable to leaving the fruits of their extensive labors unavailable to the practice community.

Apart from all these distractions, what has generated the most controversy has been the actual guidelines for the management of patients with hypertension who are aged 60 years or older. This is a pretty sizable chunk of the total population with hypertension, since the prevalence of elevated blood pressure increases dramatically with age. And this is also the population whose consequences of inadequately controlled hypertension are the most severe. The majority of strokes occur in those over the age of 60, as do most of the myocardial infarctions and cases of new-onset heart failure.

This group truly has a lot at stake when it comes to hypertension control or lack thereof. And I have to tell you, it’s a group I identify with. I saw 60 in the rearview mirror several years back, and I’ve been on antihypertensive therapy since my late thirties. Consequently, I am following this discussion very closely for both professional and personal reasons.

The JNC 8 authors recommended against initiating antihypertensive therapy in patients over the age of 60 unless their blood pressure was over 150/90 mm Hg, which represents a loosening of the earlier recommendations to start drug treatment at the lower systolic level of 140 mm Hg. Also, the new goal for antihypertensive therapy in this age group is simply to achieve a systolic pressure of ≤ 150 mm Hg, instead of the previous goal of under 140 mm Hg.

I am of two minds about this relaxation of the blood pressure goals. On the one hand, I acknowledge that the recommendations are evidence based, at least in the sense that no incontrovertible data exist to refute this more relaxed goal. There are simply not any credible studies out there that demonstrate better results when the systolic goal is 140 mm Hg rather than 150 mm Hg. It doesn’t mean that it might not be true—140 might really be better than 150—it simply means that the issue has not been studied in any clinical trial. So from a purist, evidence-based standpoint, I can accept that the new recommendation is perfectly valid from a scientific point of view.

But the part of me that values the art of medicine as well as the science is profoundly troubled by this lockstep scientific purity. What I am extremely concerned about is the possibility that the practice community will misinterpret the recommendations and take them as a mandate to loosen blood pressure control in those over age 60. If the target is just to get the systolic below 150 mm Hg, some may conclude that a pressure of 160 or even 165 is “close enough for government work,” to use the convenient phrase that dogs us federal employees. This would be a misinterpretation of the guidelines’ actual recommendation, but nonetheless, a very understandable and almost predictable one. Given that the practice community has never done a bang-up job of getting patients to the goals previously recommended, is it really the time to relax those guidelines and run the risk of even less blood pressure control?

I have to reluctantly conclude that the pseudo JNC 8 guidelines are not so great, at least for hypertensive patients over age 60. Although I cannot quibble with the strict scientific underpinning of the guidelines, they seem very likely to lead to a setback in hypertension control. We may see more heart attacks, strokes, heart failure, and renal failure if practitioners take the new guidelines as license to be less vigilant in treating elevated blood pressure. Treating elevated blood pressure is the low-hanging fruit for most primary care providers, and discouraging them from plucking that fruit from the tree is clearly a step in the wrong direction.

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

The previous set of official recommendations for hypertension management was published way back in 2003. So the practice community has waited very patiently for an updated set of guidelines. The previous guidelines were known as JNC 7, referring to the seventh iteration of recommendations emanating from a group of big-time hypertension experts known as the Joint National Committee (JNC). All the JNC reports have been sponsored by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and hence, had a high degree of visibility and credibility. However, many practitioners felt that cost considerations mitigating in favor of inexpensive drugs, such as thiazide diuretics, unfairly colored and distorted the JNC 7 recommendations.

In the interest of full disclosure, I should point out that I was one of the many Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) investigators who produced an influential study result that indeed seemed to favor diuretics over the newer and more expensive antihypertensive therapies. So JNC 7 was received with some suspicion that saving money might have taken precedence over optimal therapeutic management.

Many new studies relevant to hypertension goals and preferred antihypertensive therapies have come out in the years since JNC 7 first appeared. So there was a lot of anticipation that these more recent studies would inform and modify some of the existing JNC recommendations. This sort of speculation was all very fair and reasonable. But then something quite unanticipated happened. The JNC 8 experts met and discussed recommendations, but no guidelines emerged. Literally, years went by, and the recommendations that were expected as JNC 8 instead became known as JNC Wait and then JNC Late.

Then the NIH decided that it didn’t want to be in the guideline-issuing business any longer. The NIH outsourced its lipid guidelines, which had previously been known as the NCEP (National Cholesterol Education Panel) recommendations, to a joint committee of the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology. The hypertension experts who had met as the JNC 8 group were similarly cut loose from formal NIH sponsorship. This action was not because the NIH was unhappy with their work, but rather because the NIH had simply decided that it no longer wanted to sponsor any clinical recommendations of any sort.

So what to do? Having finally reached consensus after years of meetings, the JNC 8 experts found themselves without an official sponsor. So they decided to take a page from rock star Prince’s playbook, and they published their recommendations as “the Panel Members Appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee.” This move was a bit awkward, to say the least, but it was certainly preferable to leaving the fruits of their extensive labors unavailable to the practice community.

Apart from all these distractions, what has generated the most controversy has been the actual guidelines for the management of patients with hypertension who are aged 60 years or older. This is a pretty sizable chunk of the total population with hypertension, since the prevalence of elevated blood pressure increases dramatically with age. And this is also the population whose consequences of inadequately controlled hypertension are the most severe. The majority of strokes occur in those over the age of 60, as do most of the myocardial infarctions and cases of new-onset heart failure.

This group truly has a lot at stake when it comes to hypertension control or lack thereof. And I have to tell you, it’s a group I identify with. I saw 60 in the rearview mirror several years back, and I’ve been on antihypertensive therapy since my late thirties. Consequently, I am following this discussion very closely for both professional and personal reasons.

The JNC 8 authors recommended against initiating antihypertensive therapy in patients over the age of 60 unless their blood pressure was over 150/90 mm Hg, which represents a loosening of the earlier recommendations to start drug treatment at the lower systolic level of 140 mm Hg. Also, the new goal for antihypertensive therapy in this age group is simply to achieve a systolic pressure of ≤ 150 mm Hg, instead of the previous goal of under 140 mm Hg.

I am of two minds about this relaxation of the blood pressure goals. On the one hand, I acknowledge that the recommendations are evidence based, at least in the sense that no incontrovertible data exist to refute this more relaxed goal. There are simply not any credible studies out there that demonstrate better results when the systolic goal is 140 mm Hg rather than 150 mm Hg. It doesn’t mean that it might not be true—140 might really be better than 150—it simply means that the issue has not been studied in any clinical trial. So from a purist, evidence-based standpoint, I can accept that the new recommendation is perfectly valid from a scientific point of view.

But the part of me that values the art of medicine as well as the science is profoundly troubled by this lockstep scientific purity. What I am extremely concerned about is the possibility that the practice community will misinterpret the recommendations and take them as a mandate to loosen blood pressure control in those over age 60. If the target is just to get the systolic below 150 mm Hg, some may conclude that a pressure of 160 or even 165 is “close enough for government work,” to use the convenient phrase that dogs us federal employees. This would be a misinterpretation of the guidelines’ actual recommendation, but nonetheless, a very understandable and almost predictable one. Given that the practice community has never done a bang-up job of getting patients to the goals previously recommended, is it really the time to relax those guidelines and run the risk of even less blood pressure control?

I have to reluctantly conclude that the pseudo JNC 8 guidelines are not so great, at least for hypertensive patients over age 60. Although I cannot quibble with the strict scientific underpinning of the guidelines, they seem very likely to lead to a setback in hypertension control. We may see more heart attacks, strokes, heart failure, and renal failure if practitioners take the new guidelines as license to be less vigilant in treating elevated blood pressure. Treating elevated blood pressure is the low-hanging fruit for most primary care providers, and discouraging them from plucking that fruit from the tree is clearly a step in the wrong direction.

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.