User login

Cavitary Lung Lesion in a Tuberculosis-Negative Patient

A patient with worsening chronic cough, shortness of breath, and hemoptysis tested negative for tuberculosis; but a chest computed tomography scan showed an upper left lobe cavitary lesion.

A 71-year-old, currently homeless male veteran with a 29 pack-year history of smoking and history of alcohol abuse presented to the emergency department at Washington DC Veterans Affairs Medical Center with worsening chronic cough and shortness of breath. He had no history of HIV or immunosuppressant medications. Four weeks prior, he was treated at an outpatient urgent care for community acquired pneumonia with a 10-day course of oral amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 875 mg twice daily and azithromycin 500 mg day 1, then 250 mg days 2 through 5. Despite antibiotic therapy, his symptoms continued to worsen, and he developed hemoptysis. He also reported weight loss of 20 lb in the past 3 months despite a strong appetite and adequate oral intake. He reported no fevers and night sweats. A review of the patient’s systems was otherwise unremarkable.

On examination, the patient was afebrile at 37.2 °C but tachycardic at 108 beats/min. He also was tachypneic at 22 breaths/min with an oxygen saturation of 89% on room air. Decreased breath sounds in the left upper lobe were noted on auscultation of the lung fields. Laboratory test results were notable for a leukocytosis of 14.3 k/μL (reference range, 4-11k/μL) and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 25.08 mm/h (reference range, 0-16 mm/h) and C-reactive protein (CRP) of 4.75 mg/L (reference range, 0.00-3.00 mg/L). Liver-associated enzymes and a coagulation panel were within normal limits. His QuantiFERON-TB Gold tuberculosis (TB) blood test was negative. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest was obtained, which showed an interval increase of a known upper left lobe cavitary lesion compared with that of prior imaging and the presence of a ball-shaped lesion in the cavity (Figures 1 and 2).

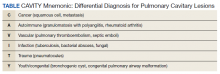

In addition to the imaging, the patient underwent bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) to further evaluate the upper left lobe cavitary lesion. The differential diagnosis for pulmonary cavities is described in the Table. The BAL aspirates were negative for acid-fast bacteria; however, periodic acid–Schiff stain and Grocott methenamine silver stain showed fungal elements. He was diagnosed with chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis (CCPA), confirmed with serum antigen (galactomannan assay) and serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) positive for Aspergillus fumigatus (A fumigatus). Mycologic cultures were positive for A fumigatus.

Discussion

Aspergillomas are accumulations of Aspergillus spp hyphae, fibrin, and other inflammatory components that typically occur in preexisting pulmonary cavities.1 They are most frequently caused by A fumigatus, which is ubiquitous in the environment and acquired via inhalation of airborne spores in 90% of cases.2 The typical ball-shaped appearance forms when hyphae growing along the inside walls of the cavity ultimately fall inward, usually leaving a surrounding pocket of air that can be seen on diagnostic imaging. CCPA falls within the chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA) category, which includes a spectrum of other subtypes to include single aspergillomas, Aspergillus nodules, and chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis (CFPA). The prevalence of CPA and its subtypes are limited to case reports and case series in the literature, with reported rates differing up to 40-fold based on region, treatment, and diagnosis criteria.3,4 Models developed by Denning and colleagues mirror those used by The World Health Organization and estimate 1.2 million people have CPA as a sequela to pulmonary TB globally.5

A single aspergilloma (simple aspergilloma) is typically not invasive, whereas CCPA (complex aspergilloma) is the most common CPA and can behave more invasively.6,7 Both can occur in immunocompetent hosts. One study followed 140 individuals with aspergillomas for more than 7 years and found that 60.8% of aspergillomas remained stable in size, while 25.9% increased and 13.3% decreased in size. Half of cases were complicated by hemoptysis, but only 4.2% of cases became invasive.8 Roughly 70% of aspergillomas occur in individuals with a previous history of TB, but any pulmonary cavity can put a patient at increased risk.

Cases have been observed in patients with pulmonary cysts, emphysema/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bullae, lung cancer, sarcoidosis, other fungal cavities, and previous lung surgeries.9 Because of its association with CPA, TB testing should be completed as part of the workup as was the case in our patient. Although QuantiFERON-TB Gold has an estimated sensitivity of 92% per the manufacturer’s package insert, results can vary depending on the setting and extent of the TB.10

Clinical features of Aspergillus infection in immunocompetent individuals include weight loss, chronic nonproductive cough, hemoptysis of variable severity, fatigue, and/or shortness of breath.11 CT is the imaging modality of choice and will typically show an upper-lobe cavitation with or without a fungal ball. For patients with suspicious imaging, laboratory testing with serum Aspergillus IgG antibodies should be performed. Aspergillus antigen testing is performed with galactomannan enzyme immunoassay, which detects galactomannan, a polysaccharide antigen that exists primarily in the cell walls of Aspergillus spp. This should be performed on BAL washings rather than serum, however, as serum testing has poor sensitivity.11 Sputum culture is not very sensitive, and although the polymerase chain reaction of sputum and BAL fluid are more sensitive than culture, false-positive results can occur with transient colonization or contamination of samples.11,12 Elevations of inflammatory markers, namely ESR and CRP, are commonly present but not specific for CPA.

Denning and colleagues propose the following criteria for diagnosing CCPA: one large cavity or 2 or more cavities on chest imaging with or without a fungal ball (aspergilloma) in one or more of the cavities (exclude patients with other chronic fungal cavitary lesions, eg, pulmonary histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, and paracoccidioidomycosis); and at least one of the following symptoms for at least 3 months: fever, weight loss, fatigue, cough, sputum production, hemoptysis, or shortness of breath; and a positive Aspergillus IgG with or without culture of Aspergillus spp from the lungs.11Our case fulfills the diagnostic criteria for CCPA. The ≥ 3 months of weight loss was useful in differentiating this case from a single aspergilloma in which the role of antifungal treatment remains unclear especially in those who are asymptomatic.2 In those with single aspergillomas with significant hemoptysis, embolization may be required. In the management of localized CCPA, surgical excision is recommended and curative in many cases.6,11 If left untreated, CCPA carries a 5-year mortality rate as high as 80% and often is accompanied with progression to CFPA, the terminal fibrosing evolution of CCPA, resulting in major fibrotic lung destruction.6 Oral azoles with or without surgical management also are useful in preventing clinical and radiologic progression.6

A multidisciplinary team, including infectious disease and surgery carefully discussed treatment options with the patient. Surgery was offered and the patient declined. We then decided on a trial of medical management alone based on shared decision making. In accordance with the recommendations from our infectious disease colleagues, the patient was started on a voriconazole 200 mg orally twice daily. Duration of therapy was planned for 6 months, with close monitoring of hepatic function, serum electrolytes, and visual function.13

Conclusions

This case highlights important differences among the CPA subtypes and how management differs based on etiology. Diagnostic criteria for CCPA were discussed, and in any patient with the constellation of the symptoms described with one or more cavitary lesions noted on imaging, CCPA should be considered regardless of immunocompetence. A multidisciplinary treatment approach with medical and surgical considerations is crucial to prevent progression to CFPA.

1. Kon K, Rai M, eds. The Microbiology of Respiratory System Infections. Academic Press; 2016.

2. Alguire P, Chick D, eds. ACP MKSAP 18: Medical Knowledge Self-Assessment Program. American College of Physicians; 2018.

3. Tuberculosis Association. Aspergilloma and residual tuberculous cavities. The results of a resurvey. Tubercle. 1970;51(3):227-245.

4. Tuberculosis Association. Aspergillus in persistent lung cavities after tuberculosis. A report from the Research Committee of the British Tuberculosis Association. Tubercle. 968;49(1):1-11.

5. Denning DW, Pleuvry A, Cole DC. Global burden of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis as a sequel to pulmonary tuberculosis. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89(12):864-872. doi:10.2471/BLT.11.089441

6. Page ID, Byanyima R, Hosmane S, et al. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis commonly complicates treated pulmonary tuberculosis with residual cavitation. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(3):1801184. doi:10.1183/13993003.01184-2018

7. Kousha, M, Tadi R, Soubani AO. Pulmonary aspergillosis: a clinical review. Eur Respir Rev. 2011;20(121):156-174. doi:10.1183/09059180.00001011

8. Lee JK, Lee Y, Park SS, et al. Clinical course and prognostic factors of pulmonary aspergilloma. Respirology. 2014;19(7):1066-1072. doi:10.1111/resp.12344

9. Kawamura S, Maesaki S, Tomono K, Tashiro T, Kohno S. Clinical evaluation of 61 patients with pulmonary aspergilloma. Intern Med. 2000;39(3):209-212. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.39.209

10. QuantiFERON-TB Gold ELISA. Package insert. Qiagen; November 2019.

11. Denning DW, Cadranel J, Beigelman-Aubry C, et al; European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases and European Respiratory Society. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: rationale and clinical guidelines for diagnosis and management. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(1):45-68. doi:10.1183/13993003.00583-2015. PMID: 26699723.

12. Denning DW, Park S, Lass-Florl C, et al. High-frequency triazole resistance found in nonculturable Aspergillus fumigatus from lungs of patients with chronic fungal disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(9):1123-9. doi:10.1093/cid/cir179

13. Patterson TF, Thompson GR III, Denning DW, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(4):e1-e60. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw326

A patient with worsening chronic cough, shortness of breath, and hemoptysis tested negative for tuberculosis; but a chest computed tomography scan showed an upper left lobe cavitary lesion.

A 71-year-old, currently homeless male veteran with a 29 pack-year history of smoking and history of alcohol abuse presented to the emergency department at Washington DC Veterans Affairs Medical Center with worsening chronic cough and shortness of breath. He had no history of HIV or immunosuppressant medications. Four weeks prior, he was treated at an outpatient urgent care for community acquired pneumonia with a 10-day course of oral amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 875 mg twice daily and azithromycin 500 mg day 1, then 250 mg days 2 through 5. Despite antibiotic therapy, his symptoms continued to worsen, and he developed hemoptysis. He also reported weight loss of 20 lb in the past 3 months despite a strong appetite and adequate oral intake. He reported no fevers and night sweats. A review of the patient’s systems was otherwise unremarkable.

On examination, the patient was afebrile at 37.2 °C but tachycardic at 108 beats/min. He also was tachypneic at 22 breaths/min with an oxygen saturation of 89% on room air. Decreased breath sounds in the left upper lobe were noted on auscultation of the lung fields. Laboratory test results were notable for a leukocytosis of 14.3 k/μL (reference range, 4-11k/μL) and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 25.08 mm/h (reference range, 0-16 mm/h) and C-reactive protein (CRP) of 4.75 mg/L (reference range, 0.00-3.00 mg/L). Liver-associated enzymes and a coagulation panel were within normal limits. His QuantiFERON-TB Gold tuberculosis (TB) blood test was negative. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest was obtained, which showed an interval increase of a known upper left lobe cavitary lesion compared with that of prior imaging and the presence of a ball-shaped lesion in the cavity (Figures 1 and 2).

In addition to the imaging, the patient underwent bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) to further evaluate the upper left lobe cavitary lesion. The differential diagnosis for pulmonary cavities is described in the Table. The BAL aspirates were negative for acid-fast bacteria; however, periodic acid–Schiff stain and Grocott methenamine silver stain showed fungal elements. He was diagnosed with chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis (CCPA), confirmed with serum antigen (galactomannan assay) and serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) positive for Aspergillus fumigatus (A fumigatus). Mycologic cultures were positive for A fumigatus.

Discussion

Aspergillomas are accumulations of Aspergillus spp hyphae, fibrin, and other inflammatory components that typically occur in preexisting pulmonary cavities.1 They are most frequently caused by A fumigatus, which is ubiquitous in the environment and acquired via inhalation of airborne spores in 90% of cases.2 The typical ball-shaped appearance forms when hyphae growing along the inside walls of the cavity ultimately fall inward, usually leaving a surrounding pocket of air that can be seen on diagnostic imaging. CCPA falls within the chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA) category, which includes a spectrum of other subtypes to include single aspergillomas, Aspergillus nodules, and chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis (CFPA). The prevalence of CPA and its subtypes are limited to case reports and case series in the literature, with reported rates differing up to 40-fold based on region, treatment, and diagnosis criteria.3,4 Models developed by Denning and colleagues mirror those used by The World Health Organization and estimate 1.2 million people have CPA as a sequela to pulmonary TB globally.5

A single aspergilloma (simple aspergilloma) is typically not invasive, whereas CCPA (complex aspergilloma) is the most common CPA and can behave more invasively.6,7 Both can occur in immunocompetent hosts. One study followed 140 individuals with aspergillomas for more than 7 years and found that 60.8% of aspergillomas remained stable in size, while 25.9% increased and 13.3% decreased in size. Half of cases were complicated by hemoptysis, but only 4.2% of cases became invasive.8 Roughly 70% of aspergillomas occur in individuals with a previous history of TB, but any pulmonary cavity can put a patient at increased risk.

Cases have been observed in patients with pulmonary cysts, emphysema/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bullae, lung cancer, sarcoidosis, other fungal cavities, and previous lung surgeries.9 Because of its association with CPA, TB testing should be completed as part of the workup as was the case in our patient. Although QuantiFERON-TB Gold has an estimated sensitivity of 92% per the manufacturer’s package insert, results can vary depending on the setting and extent of the TB.10

Clinical features of Aspergillus infection in immunocompetent individuals include weight loss, chronic nonproductive cough, hemoptysis of variable severity, fatigue, and/or shortness of breath.11 CT is the imaging modality of choice and will typically show an upper-lobe cavitation with or without a fungal ball. For patients with suspicious imaging, laboratory testing with serum Aspergillus IgG antibodies should be performed. Aspergillus antigen testing is performed with galactomannan enzyme immunoassay, which detects galactomannan, a polysaccharide antigen that exists primarily in the cell walls of Aspergillus spp. This should be performed on BAL washings rather than serum, however, as serum testing has poor sensitivity.11 Sputum culture is not very sensitive, and although the polymerase chain reaction of sputum and BAL fluid are more sensitive than culture, false-positive results can occur with transient colonization or contamination of samples.11,12 Elevations of inflammatory markers, namely ESR and CRP, are commonly present but not specific for CPA.

Denning and colleagues propose the following criteria for diagnosing CCPA: one large cavity or 2 or more cavities on chest imaging with or without a fungal ball (aspergilloma) in one or more of the cavities (exclude patients with other chronic fungal cavitary lesions, eg, pulmonary histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, and paracoccidioidomycosis); and at least one of the following symptoms for at least 3 months: fever, weight loss, fatigue, cough, sputum production, hemoptysis, or shortness of breath; and a positive Aspergillus IgG with or without culture of Aspergillus spp from the lungs.11Our case fulfills the diagnostic criteria for CCPA. The ≥ 3 months of weight loss was useful in differentiating this case from a single aspergilloma in which the role of antifungal treatment remains unclear especially in those who are asymptomatic.2 In those with single aspergillomas with significant hemoptysis, embolization may be required. In the management of localized CCPA, surgical excision is recommended and curative in many cases.6,11 If left untreated, CCPA carries a 5-year mortality rate as high as 80% and often is accompanied with progression to CFPA, the terminal fibrosing evolution of CCPA, resulting in major fibrotic lung destruction.6 Oral azoles with or without surgical management also are useful in preventing clinical and radiologic progression.6

A multidisciplinary team, including infectious disease and surgery carefully discussed treatment options with the patient. Surgery was offered and the patient declined. We then decided on a trial of medical management alone based on shared decision making. In accordance with the recommendations from our infectious disease colleagues, the patient was started on a voriconazole 200 mg orally twice daily. Duration of therapy was planned for 6 months, with close monitoring of hepatic function, serum electrolytes, and visual function.13

Conclusions

This case highlights important differences among the CPA subtypes and how management differs based on etiology. Diagnostic criteria for CCPA were discussed, and in any patient with the constellation of the symptoms described with one or more cavitary lesions noted on imaging, CCPA should be considered regardless of immunocompetence. A multidisciplinary treatment approach with medical and surgical considerations is crucial to prevent progression to CFPA.

A patient with worsening chronic cough, shortness of breath, and hemoptysis tested negative for tuberculosis; but a chest computed tomography scan showed an upper left lobe cavitary lesion.

A 71-year-old, currently homeless male veteran with a 29 pack-year history of smoking and history of alcohol abuse presented to the emergency department at Washington DC Veterans Affairs Medical Center with worsening chronic cough and shortness of breath. He had no history of HIV or immunosuppressant medications. Four weeks prior, he was treated at an outpatient urgent care for community acquired pneumonia with a 10-day course of oral amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 875 mg twice daily and azithromycin 500 mg day 1, then 250 mg days 2 through 5. Despite antibiotic therapy, his symptoms continued to worsen, and he developed hemoptysis. He also reported weight loss of 20 lb in the past 3 months despite a strong appetite and adequate oral intake. He reported no fevers and night sweats. A review of the patient’s systems was otherwise unremarkable.

On examination, the patient was afebrile at 37.2 °C but tachycardic at 108 beats/min. He also was tachypneic at 22 breaths/min with an oxygen saturation of 89% on room air. Decreased breath sounds in the left upper lobe were noted on auscultation of the lung fields. Laboratory test results were notable for a leukocytosis of 14.3 k/μL (reference range, 4-11k/μL) and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 25.08 mm/h (reference range, 0-16 mm/h) and C-reactive protein (CRP) of 4.75 mg/L (reference range, 0.00-3.00 mg/L). Liver-associated enzymes and a coagulation panel were within normal limits. His QuantiFERON-TB Gold tuberculosis (TB) blood test was negative. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest was obtained, which showed an interval increase of a known upper left lobe cavitary lesion compared with that of prior imaging and the presence of a ball-shaped lesion in the cavity (Figures 1 and 2).

In addition to the imaging, the patient underwent bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) to further evaluate the upper left lobe cavitary lesion. The differential diagnosis for pulmonary cavities is described in the Table. The BAL aspirates were negative for acid-fast bacteria; however, periodic acid–Schiff stain and Grocott methenamine silver stain showed fungal elements. He was diagnosed with chronic cavitary pulmonary aspergillosis (CCPA), confirmed with serum antigen (galactomannan assay) and serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) positive for Aspergillus fumigatus (A fumigatus). Mycologic cultures were positive for A fumigatus.

Discussion

Aspergillomas are accumulations of Aspergillus spp hyphae, fibrin, and other inflammatory components that typically occur in preexisting pulmonary cavities.1 They are most frequently caused by A fumigatus, which is ubiquitous in the environment and acquired via inhalation of airborne spores in 90% of cases.2 The typical ball-shaped appearance forms when hyphae growing along the inside walls of the cavity ultimately fall inward, usually leaving a surrounding pocket of air that can be seen on diagnostic imaging. CCPA falls within the chronic pulmonary aspergillosis (CPA) category, which includes a spectrum of other subtypes to include single aspergillomas, Aspergillus nodules, and chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis (CFPA). The prevalence of CPA and its subtypes are limited to case reports and case series in the literature, with reported rates differing up to 40-fold based on region, treatment, and diagnosis criteria.3,4 Models developed by Denning and colleagues mirror those used by The World Health Organization and estimate 1.2 million people have CPA as a sequela to pulmonary TB globally.5

A single aspergilloma (simple aspergilloma) is typically not invasive, whereas CCPA (complex aspergilloma) is the most common CPA and can behave more invasively.6,7 Both can occur in immunocompetent hosts. One study followed 140 individuals with aspergillomas for more than 7 years and found that 60.8% of aspergillomas remained stable in size, while 25.9% increased and 13.3% decreased in size. Half of cases were complicated by hemoptysis, but only 4.2% of cases became invasive.8 Roughly 70% of aspergillomas occur in individuals with a previous history of TB, but any pulmonary cavity can put a patient at increased risk.

Cases have been observed in patients with pulmonary cysts, emphysema/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bullae, lung cancer, sarcoidosis, other fungal cavities, and previous lung surgeries.9 Because of its association with CPA, TB testing should be completed as part of the workup as was the case in our patient. Although QuantiFERON-TB Gold has an estimated sensitivity of 92% per the manufacturer’s package insert, results can vary depending on the setting and extent of the TB.10

Clinical features of Aspergillus infection in immunocompetent individuals include weight loss, chronic nonproductive cough, hemoptysis of variable severity, fatigue, and/or shortness of breath.11 CT is the imaging modality of choice and will typically show an upper-lobe cavitation with or without a fungal ball. For patients with suspicious imaging, laboratory testing with serum Aspergillus IgG antibodies should be performed. Aspergillus antigen testing is performed with galactomannan enzyme immunoassay, which detects galactomannan, a polysaccharide antigen that exists primarily in the cell walls of Aspergillus spp. This should be performed on BAL washings rather than serum, however, as serum testing has poor sensitivity.11 Sputum culture is not very sensitive, and although the polymerase chain reaction of sputum and BAL fluid are more sensitive than culture, false-positive results can occur with transient colonization or contamination of samples.11,12 Elevations of inflammatory markers, namely ESR and CRP, are commonly present but not specific for CPA.

Denning and colleagues propose the following criteria for diagnosing CCPA: one large cavity or 2 or more cavities on chest imaging with or without a fungal ball (aspergilloma) in one or more of the cavities (exclude patients with other chronic fungal cavitary lesions, eg, pulmonary histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, and paracoccidioidomycosis); and at least one of the following symptoms for at least 3 months: fever, weight loss, fatigue, cough, sputum production, hemoptysis, or shortness of breath; and a positive Aspergillus IgG with or without culture of Aspergillus spp from the lungs.11Our case fulfills the diagnostic criteria for CCPA. The ≥ 3 months of weight loss was useful in differentiating this case from a single aspergilloma in which the role of antifungal treatment remains unclear especially in those who are asymptomatic.2 In those with single aspergillomas with significant hemoptysis, embolization may be required. In the management of localized CCPA, surgical excision is recommended and curative in many cases.6,11 If left untreated, CCPA carries a 5-year mortality rate as high as 80% and often is accompanied with progression to CFPA, the terminal fibrosing evolution of CCPA, resulting in major fibrotic lung destruction.6 Oral azoles with or without surgical management also are useful in preventing clinical and radiologic progression.6

A multidisciplinary team, including infectious disease and surgery carefully discussed treatment options with the patient. Surgery was offered and the patient declined. We then decided on a trial of medical management alone based on shared decision making. In accordance with the recommendations from our infectious disease colleagues, the patient was started on a voriconazole 200 mg orally twice daily. Duration of therapy was planned for 6 months, with close monitoring of hepatic function, serum electrolytes, and visual function.13

Conclusions

This case highlights important differences among the CPA subtypes and how management differs based on etiology. Diagnostic criteria for CCPA were discussed, and in any patient with the constellation of the symptoms described with one or more cavitary lesions noted on imaging, CCPA should be considered regardless of immunocompetence. A multidisciplinary treatment approach with medical and surgical considerations is crucial to prevent progression to CFPA.

1. Kon K, Rai M, eds. The Microbiology of Respiratory System Infections. Academic Press; 2016.

2. Alguire P, Chick D, eds. ACP MKSAP 18: Medical Knowledge Self-Assessment Program. American College of Physicians; 2018.

3. Tuberculosis Association. Aspergilloma and residual tuberculous cavities. The results of a resurvey. Tubercle. 1970;51(3):227-245.

4. Tuberculosis Association. Aspergillus in persistent lung cavities after tuberculosis. A report from the Research Committee of the British Tuberculosis Association. Tubercle. 968;49(1):1-11.

5. Denning DW, Pleuvry A, Cole DC. Global burden of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis as a sequel to pulmonary tuberculosis. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89(12):864-872. doi:10.2471/BLT.11.089441

6. Page ID, Byanyima R, Hosmane S, et al. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis commonly complicates treated pulmonary tuberculosis with residual cavitation. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(3):1801184. doi:10.1183/13993003.01184-2018

7. Kousha, M, Tadi R, Soubani AO. Pulmonary aspergillosis: a clinical review. Eur Respir Rev. 2011;20(121):156-174. doi:10.1183/09059180.00001011

8. Lee JK, Lee Y, Park SS, et al. Clinical course and prognostic factors of pulmonary aspergilloma. Respirology. 2014;19(7):1066-1072. doi:10.1111/resp.12344

9. Kawamura S, Maesaki S, Tomono K, Tashiro T, Kohno S. Clinical evaluation of 61 patients with pulmonary aspergilloma. Intern Med. 2000;39(3):209-212. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.39.209

10. QuantiFERON-TB Gold ELISA. Package insert. Qiagen; November 2019.

11. Denning DW, Cadranel J, Beigelman-Aubry C, et al; European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases and European Respiratory Society. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: rationale and clinical guidelines for diagnosis and management. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(1):45-68. doi:10.1183/13993003.00583-2015. PMID: 26699723.

12. Denning DW, Park S, Lass-Florl C, et al. High-frequency triazole resistance found in nonculturable Aspergillus fumigatus from lungs of patients with chronic fungal disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(9):1123-9. doi:10.1093/cid/cir179

13. Patterson TF, Thompson GR III, Denning DW, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(4):e1-e60. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw326

1. Kon K, Rai M, eds. The Microbiology of Respiratory System Infections. Academic Press; 2016.

2. Alguire P, Chick D, eds. ACP MKSAP 18: Medical Knowledge Self-Assessment Program. American College of Physicians; 2018.

3. Tuberculosis Association. Aspergilloma and residual tuberculous cavities. The results of a resurvey. Tubercle. 1970;51(3):227-245.

4. Tuberculosis Association. Aspergillus in persistent lung cavities after tuberculosis. A report from the Research Committee of the British Tuberculosis Association. Tubercle. 968;49(1):1-11.

5. Denning DW, Pleuvry A, Cole DC. Global burden of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis as a sequel to pulmonary tuberculosis. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89(12):864-872. doi:10.2471/BLT.11.089441

6. Page ID, Byanyima R, Hosmane S, et al. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis commonly complicates treated pulmonary tuberculosis with residual cavitation. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(3):1801184. doi:10.1183/13993003.01184-2018

7. Kousha, M, Tadi R, Soubani AO. Pulmonary aspergillosis: a clinical review. Eur Respir Rev. 2011;20(121):156-174. doi:10.1183/09059180.00001011

8. Lee JK, Lee Y, Park SS, et al. Clinical course and prognostic factors of pulmonary aspergilloma. Respirology. 2014;19(7):1066-1072. doi:10.1111/resp.12344

9. Kawamura S, Maesaki S, Tomono K, Tashiro T, Kohno S. Clinical evaluation of 61 patients with pulmonary aspergilloma. Intern Med. 2000;39(3):209-212. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.39.209

10. QuantiFERON-TB Gold ELISA. Package insert. Qiagen; November 2019.

11. Denning DW, Cadranel J, Beigelman-Aubry C, et al; European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases and European Respiratory Society. Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: rationale and clinical guidelines for diagnosis and management. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(1):45-68. doi:10.1183/13993003.00583-2015. PMID: 26699723.

12. Denning DW, Park S, Lass-Florl C, et al. High-frequency triazole resistance found in nonculturable Aspergillus fumigatus from lungs of patients with chronic fungal disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(9):1123-9. doi:10.1093/cid/cir179

13. Patterson TF, Thompson GR III, Denning DW, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(4):e1-e60. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw326