User login

Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: A result of chronic, heavy Cannabis use

Cannabis is the most commonly abused drug in the United States. Since 2008, Cannabis use has significantly increased,1 in part because of legalization for medicinal and recreational use. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) is characterized by years of daily Cannabis use, recurrent nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain, compulsive bathing for symptom relief, and symptom resolution with cessation of use.

Prompt recognition of CHS can reduce costs associated with unnecessary workups, emergency department (ED) and urgent care visits, and hospital admissions.2,3 This article provides a review of CHS with discussion of diagnostic and management considerations.

CASE REPORT Nauseated and vomiting—and stoned

Mr. M, age 24, self-presents to the ED complaining of two days of severe nausea, colicky abdominal pain, and nonbloody, nonbilious vomiting, as often as 20 times a day. His symptoms become worse with food, and he has difficulty eating and drinking because of his vomiting. Mr. M reports transient symptom relief when he takes hot showers, and has been taking more than 14 showers a day. He reports similar episodes, occurring every two or three months over the last two years, resulting in several ED visits and three hospital admissions.

Mr. M has smoked two to three joints a day for seven years; he has increased his Cannabis use in an attempt to alleviate his symptoms, but isn’t sure if doing so was helpful. He denies use of tobacco and other illicit drugs, and reports drinking one to three drinks no more than twice a month. He reports dizziness when standing, but no other symptoms. He does not take any medications, and medical and psychiatric histories are unremarkable.

Physical exam reveals a thin, uncomfortable, young man. Vital signs were significant for tachycardia and mild orthostatic hypotension. His abdomen was diffusely tender, soft, and nondistended. Urine toxicology is positive for delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) only. Labs, including a complete blood count (CBC), basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, and lipase, are within normal limits. Prior workup included abdominal radiographs, abdominal ultrasonography, abdominal CT, and gastric biopsy; all are normal. He has mild gastritis and esophagitis on esophagogastroduodenoscopy and mildly delayed gastric emptying. HIV and hepatitis screenings are negative. Six months ago he received antibiotic therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection.

Mr. M is admitted to the hospital and seen by the psychiatric consultation service. He is treated with IV ondansetron and prochlorperazine, with little effect. He showers frequently until his symptoms begin to abate within 36 hours of stopping Cannabis use, and is discharged soon after. Psychiatric clinicians provide brief motivational interviewing while Mr. M is in the hospital, and refer him to outpatient psychiatric care and Narcotics Anonymous. Mr. M is then lost to follow up.

In 2011, 18.1 million people reported Cannabis use in the previous month; 39% reported use in 20 of the last 30 days.1 A high rate of use and a relatively low number of cases suggests that CHS is rare. However, it is likely that CHS is under-recognized and under-reported.2,4,5 CHS symptoms may be misattributed to cyclic vomiting syndrome,3 because 50% of patients diagnosed with cyclic vomiting syndrome report daily Cannabis use.6 There is no epidemiological data on the incidence or prevalence of CHS among regular Cannabis users.7

Allen and colleagues first described this syndrome in 2004.4 Since then, CHS has been documented in a growing number of case reports and reviews,2,3,5,7-13 yet it continues to be under-recognized. Many CHS patients experience delays in diagnosis—often years—resulting in prolonged suffering, and costs incurred by frequent ED and urgent care visits, hospital admissions, and unnecessary workups.2,3,7

Clinical characteristics

CHS is characterized by recurrent, hyperemetic episodes in the context of chronic, daily Cannabis use.4 The average age of onset is 25.6 years (range: 16 to 51 years).3 Ninety-five percent of CHS patients used Cannabis daily, for, on average, 9.8 years before symptom onset.3 The amount of Cannabis used, although generally high, is difficult to quantify, and has been described as heavy and hourly in units of blunts, cones, joints, bongs, etc. Patients are most likely to present during acute hyperemetic episodes, which occur in a cyclic pattern, every four to eight weeks,3 interspersed with symptom-free periods. Three phases have been described:

- prodromal or pre-emetic phase

- hyperemetic phase

- recovery phase.4,10

Many patients report a prodromal phase, with one or two weeks of morning nausea, food aversion, preserved eating patterns, possible weight loss, and occasional vomiting. The acute, hyperemetic phase is characterized by severe nausea, frequent vomiting, abdominal pain, and compulsive bathing for temporary symptom relief. In the recovery phase, symptom improvement and resolution occur with cessation of Cannabis use.4,10 Symptom improvement can occur within 12 hours of Cannabis cessation, but can take as long as three weeks.3 Patients remain symptom-free while abstinent, but symptoms rapidly recur when they resume use.3,4

Cannabis is used as an antiemetic and appetite stimulant for chemotherapy-associated nausea and for anorexia in HIV infection. The pathogenesis of paradoxical hyperemetic symptoms of CHS remain unclear, but several mechanisms have been proposed. The principle active cannabinoid in Cannabis is the highly lipophilic compound THC, which binds to cannabinoid type 1 (CB1) and type 2 (CB2) receptors in the CNS and other tissues. It is thought that the antiemetic and appetite-stimulating effects of Cannabis are mediated by CB1 receptor activation in the hypothalamus. Nausea and vomiting are thought to be mediated by CB1 receptor activation in the enteric nervous system, which causes slowed peristalsis, delayed gastric emptying, and splanchnic vasodilation.4,14

In sensitive persons, chronic heavy Cannabis use can cause THC to accumulate to a toxic level in fatty tissues, causing enteric receptor binding effects to override the CNS receptor-binding effects.4 This is supported by case studies describing severe vomiting with IV injection of crude marijuana extract.15 Nearly 100 different THC metabolites have been identified. The Cannabis plant contains more than 400 chemicals, with 60 cannabinoid structures, any of which could cause CHS in toxic concentrations.4,7 Among them, cannabidiol, a 5-HT1A partial agonist, was shown to cause vomiting at higher doses in animal studies.4,7

Mechanisms of action

Cannabis has been used for centuries, so it is unclear why CHS is only recently being recognized. It may be because of higher THC content through selective breeding of plants and a more selective use of female buds that contain more concentrated THC levels than leaves and stems.3 Alternately, CHS may be caused by exogenous substances, such as pesticides, additives, preservatives, or other chemicals used in marijuana preparation, although there is little evidence to support this.3

The mechanism of symptom relief with hot bathing also is unclear. Patients report consistent, global symptom improvement with hot bathing.3 Relief is rapid, transient, and temperature dependent.4 CB1 receptors are located near the thermoregulatory center of the hypothalamus. Increased body temperature with hot bathing may counteract the thermoregulatory dysregulation associated with Cannabis use.4,9 It has been proposed that splanchnic vasodilation might contribute to CHS symptoms. Thus, redistribution of blood from the gut to the skin with warm bathing causes a “cutaneous steal syndrome,” resulting in symptom relief.11

Diagnostic approach

Four key features should be present when making a diagnosis of CHS:

- heavy marijuana use

- recurrent episodes of severe nausea, vomiting, and abdominal cramping

- compulsive bathing for transient symptom relief

- resolution of symptoms with cessation of Cannabis use.2,4,8

Compulsive, hot bathing for symptom relief was described in 98% of all reported cases,3 and should be considered pathognomonic.2 CHS patients can present with other symptoms, including polydipsia, mild fever, weight loss, and orthostasis.3 Although lab studies usually are normal, mild leukocytosis, hypokalemia, hypochloremia, elevated salivary amylase, mild gastritis on esophagogastroduodenoscopy, and delayed gastric emptying have been described during acute episodes (Table 1).2-4,7,8

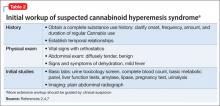

Diagnosis starts with a history and physical exam, followed by a basic workup geared towards ruling out other causes of acute nausea and vomiting.2,7 Establish temporal relationships between symptoms, Cannabis use (onset, frequency, amount, duration), and bathing behaviors. A positive urine toxicology screen supports a CHS diagnosis and can facilitate discussion of Cannabis use.2 If you suspect CHS, rule out potentially life-threatening causes of acute nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, such as intestinal obstruction or perforation, pancreaticobiliary disease, and pregnancy. The initial workup should include a CBC, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, amylase, lipase, pregnancy test, urinalysis, urine toxicology screen, and abdominal radiographs (Table 2).2,4,7 The differential diagnosis of recurrent vomiting is broad and should be considered (Table 3).2,4,7,16 Further workup can proceed non-emergently, and should be prompted by clinical suspicion.2,7

Supportive treatment, education

Treatment of acute hyperemetic episodes in CHS primarily is supportive; address dehydration with IV fluids and electrolyte replenishment as needed.2,4,7 Standard antiemetics, including 5-HT3 receptor antagonists, D2 receptor antagonists, and H1 receptor antagonists, are largely ineffective.5,9 Although narcotics have been used to treat abdominal pain, use caution when prescribing because they can exacerbate nausea and vomiting.7 Case reports have described symptom relief with inpatient treatment with lorazepam12 and self-medication with alprazolam,4 but more evidence is needed. A recent case report described prompt resolution of symptoms with IV haloperidol.13 Treating gastritis symptoms with acid suppression therapy, such as a proton pump inhibitor, has been suggested.7 Symptoms abate during hospitalization regardless of treatment, marking the progression into the recovery phase with abstinence. There are no proven treatments for CHS, aside from cessation of Cannabis use. Treatment should focus on motivating your patient to stop using Cannabis.

Acute, hyperemetic episodes are ideal teachable moments because of the acuity of symptoms and clear association with Cannabis use. However, some patients may be skeptical about CHS because of the better-known antiemetic effects of Cannabis. For such patients, provide informational materials describing CHS and take time to address their concerns or doubts.

Motivational interviewing can help provoke behavior change by exploring patient ambivalence in a directive, patient-focused manner. Randomized controlled trials have documented significant reductions in Cannabis use with single-session motivational interviewing, with greater effect among heavy users.17 Single-session motivational interviewing showed results comparable to providing drug information and advice, suggesting that education and information are useful interventions.18 Although these single-session studies appear promising, they focus on younger users who have not been using Cannabis as long as typical CHS patients. Multi-session interventions may be needed to address longstanding, heavy Cannabis use in adult CHS patients.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy. In a series of randomized controlled trials,

motivational enhancement training and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) were effective for Cannabis use cessation and maintenance of abstinence.19

Although these interventions take more time—six to 14 sessions for CBT and one to four sessions for motivational enhancement training—they should be considered for CHS patients with persistent use.

Bottom Line

Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) is characterized by years of daily, heavy Cannabis use, cyclic nausea and vomiting, and compulsive bathing. Symptoms resolve with Cannabis cessation. Workup of suspected CHS should rule out life- threatening causes of nausea and vomiting. Acute hyperemetic episodes should be managed supportively. Motivational enhancement therapy or cognitive-behavioral therapy should be considered for persistent Cannibis use.

Related Resources

- Motivational interviewing for substance use disorders. www.motivationalinterview.org.

- Danovitch I, Gorelick DA. State of the art treatments for cannabis dependence. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2012;35(2):309-326.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax Haloperidol • Haldol Lorazepam • Ativan

Ondansetron • Zofran Prochlorperazine • Compazine

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Mental health findings. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2k11MH_FindingsandDetTables/2K11MHFR/NSDUHmhfr2011.htm. Published November 2012. Accessed April 18, 2013.

2. Wallace EA, Andrews SE, Garmany CL, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: literature review and proposed diagnosis and treatment algorithm. South Med J. 2011; 104(9):659-664.

3. Nicolson SE, Denysenko L, Mulcare JL, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: a case series and review of previous reports. Psychosomatics. 2012;53(3):212-219.

4. Allen JH, de Moore GM, Heddle R, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis: cyclical hyperemesis in association with chronic cannabis abuse. Cut. 2004;53(11):1566-1570.

5. Sontineni SP, Chaudhary S, Sontineni V, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: clinical diagnosis of an underrecognised manifestation of chronic cannabis abuse. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(10):1264-1266.

6. Fajardo NR, Cremonini F, Talley NJ. Cyclic vomiting syndrome and chronic cannabis use. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:S343.

7. Galli JA, Sawaya RA, Friedenberg FK. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2011;4(4):241-249.

8. Sullivan S. Cannabinoid hyperemesis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24(5):284-285.

9. Chang YH, Windish DM. Cannabinoid hyperemesis relieved by compulsive bathing. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(1):76-78.

10. Soriano-Co M, Batke M, Cappell MS. The cannabis hyperemesis syndrome characterized by persistent nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, and compulsive bathing associated with chronic marijuana use: a report of eight cases in the United States. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(11):3113-3119.

11. Patterson DA, Smith E, Monahan M, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis and compulsive bathing: a case series and paradoxical pathophysiological explanation. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(6):790-793.

12. Cox B, Chhabra A, Adler M, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: case report of a paradoxical reaction with heavy marijuana use. Case Rep Med. 2012;2012:757696.

13. Hickey JL, Witsil JC, Mycyk MB. Haloperidol for treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome [published online April 10, 2013]. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(6):1003.e5-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.02.021.

14. McCallum RW, Soykan I, Sridhar KR, et al. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol delays the gastric emptying of solid food in humans: a double-blind, randomized study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13(1):77-80.

15. Vaziri ND, Thomas R, Sterling M, et al. Toxicity with intravenous injection of crude marijuana extract. Clin Toxicol. 1981;18(3):353-366.

16. Abell TL, Adams KA, Boles RG, et al. Cyclic vomiting syndrome in adults. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008; 20(4):269-284.

17. McCambridge J, Strang J. The efficacy of single-session motivational interviewing in reducing drug consumption and perceptions of drug-related risk and harm among young people: results from a multi-site cluster randomized trial. Addiction. 2004;99(1):39-52.

18. McCambridge J, Slym RL, Strang J. Randomized controlled trial of motivational interviewing compared with drug information and advice for early intervention among young cannabis users. Addiction. 2008;103(11):1809-1818.

19. Elkashef A, Vocci F, Huestis M, et al. Marijuana neurobiology and treatment. Subst Abus. 2008;29(3):17-29.

Cannabis is the most commonly abused drug in the United States. Since 2008, Cannabis use has significantly increased,1 in part because of legalization for medicinal and recreational use. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) is characterized by years of daily Cannabis use, recurrent nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain, compulsive bathing for symptom relief, and symptom resolution with cessation of use.

Prompt recognition of CHS can reduce costs associated with unnecessary workups, emergency department (ED) and urgent care visits, and hospital admissions.2,3 This article provides a review of CHS with discussion of diagnostic and management considerations.

CASE REPORT Nauseated and vomiting—and stoned

Mr. M, age 24, self-presents to the ED complaining of two days of severe nausea, colicky abdominal pain, and nonbloody, nonbilious vomiting, as often as 20 times a day. His symptoms become worse with food, and he has difficulty eating and drinking because of his vomiting. Mr. M reports transient symptom relief when he takes hot showers, and has been taking more than 14 showers a day. He reports similar episodes, occurring every two or three months over the last two years, resulting in several ED visits and three hospital admissions.

Mr. M has smoked two to three joints a day for seven years; he has increased his Cannabis use in an attempt to alleviate his symptoms, but isn’t sure if doing so was helpful. He denies use of tobacco and other illicit drugs, and reports drinking one to three drinks no more than twice a month. He reports dizziness when standing, but no other symptoms. He does not take any medications, and medical and psychiatric histories are unremarkable.

Physical exam reveals a thin, uncomfortable, young man. Vital signs were significant for tachycardia and mild orthostatic hypotension. His abdomen was diffusely tender, soft, and nondistended. Urine toxicology is positive for delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) only. Labs, including a complete blood count (CBC), basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, and lipase, are within normal limits. Prior workup included abdominal radiographs, abdominal ultrasonography, abdominal CT, and gastric biopsy; all are normal. He has mild gastritis and esophagitis on esophagogastroduodenoscopy and mildly delayed gastric emptying. HIV and hepatitis screenings are negative. Six months ago he received antibiotic therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection.

Mr. M is admitted to the hospital and seen by the psychiatric consultation service. He is treated with IV ondansetron and prochlorperazine, with little effect. He showers frequently until his symptoms begin to abate within 36 hours of stopping Cannabis use, and is discharged soon after. Psychiatric clinicians provide brief motivational interviewing while Mr. M is in the hospital, and refer him to outpatient psychiatric care and Narcotics Anonymous. Mr. M is then lost to follow up.

In 2011, 18.1 million people reported Cannabis use in the previous month; 39% reported use in 20 of the last 30 days.1 A high rate of use and a relatively low number of cases suggests that CHS is rare. However, it is likely that CHS is under-recognized and under-reported.2,4,5 CHS symptoms may be misattributed to cyclic vomiting syndrome,3 because 50% of patients diagnosed with cyclic vomiting syndrome report daily Cannabis use.6 There is no epidemiological data on the incidence or prevalence of CHS among regular Cannabis users.7

Allen and colleagues first described this syndrome in 2004.4 Since then, CHS has been documented in a growing number of case reports and reviews,2,3,5,7-13 yet it continues to be under-recognized. Many CHS patients experience delays in diagnosis—often years—resulting in prolonged suffering, and costs incurred by frequent ED and urgent care visits, hospital admissions, and unnecessary workups.2,3,7

Clinical characteristics

CHS is characterized by recurrent, hyperemetic episodes in the context of chronic, daily Cannabis use.4 The average age of onset is 25.6 years (range: 16 to 51 years).3 Ninety-five percent of CHS patients used Cannabis daily, for, on average, 9.8 years before symptom onset.3 The amount of Cannabis used, although generally high, is difficult to quantify, and has been described as heavy and hourly in units of blunts, cones, joints, bongs, etc. Patients are most likely to present during acute hyperemetic episodes, which occur in a cyclic pattern, every four to eight weeks,3 interspersed with symptom-free periods. Three phases have been described:

- prodromal or pre-emetic phase

- hyperemetic phase

- recovery phase.4,10

Many patients report a prodromal phase, with one or two weeks of morning nausea, food aversion, preserved eating patterns, possible weight loss, and occasional vomiting. The acute, hyperemetic phase is characterized by severe nausea, frequent vomiting, abdominal pain, and compulsive bathing for temporary symptom relief. In the recovery phase, symptom improvement and resolution occur with cessation of Cannabis use.4,10 Symptom improvement can occur within 12 hours of Cannabis cessation, but can take as long as three weeks.3 Patients remain symptom-free while abstinent, but symptoms rapidly recur when they resume use.3,4

Cannabis is used as an antiemetic and appetite stimulant for chemotherapy-associated nausea and for anorexia in HIV infection. The pathogenesis of paradoxical hyperemetic symptoms of CHS remain unclear, but several mechanisms have been proposed. The principle active cannabinoid in Cannabis is the highly lipophilic compound THC, which binds to cannabinoid type 1 (CB1) and type 2 (CB2) receptors in the CNS and other tissues. It is thought that the antiemetic and appetite-stimulating effects of Cannabis are mediated by CB1 receptor activation in the hypothalamus. Nausea and vomiting are thought to be mediated by CB1 receptor activation in the enteric nervous system, which causes slowed peristalsis, delayed gastric emptying, and splanchnic vasodilation.4,14

In sensitive persons, chronic heavy Cannabis use can cause THC to accumulate to a toxic level in fatty tissues, causing enteric receptor binding effects to override the CNS receptor-binding effects.4 This is supported by case studies describing severe vomiting with IV injection of crude marijuana extract.15 Nearly 100 different THC metabolites have been identified. The Cannabis plant contains more than 400 chemicals, with 60 cannabinoid structures, any of which could cause CHS in toxic concentrations.4,7 Among them, cannabidiol, a 5-HT1A partial agonist, was shown to cause vomiting at higher doses in animal studies.4,7

Mechanisms of action

Cannabis has been used for centuries, so it is unclear why CHS is only recently being recognized. It may be because of higher THC content through selective breeding of plants and a more selective use of female buds that contain more concentrated THC levels than leaves and stems.3 Alternately, CHS may be caused by exogenous substances, such as pesticides, additives, preservatives, or other chemicals used in marijuana preparation, although there is little evidence to support this.3

The mechanism of symptom relief with hot bathing also is unclear. Patients report consistent, global symptom improvement with hot bathing.3 Relief is rapid, transient, and temperature dependent.4 CB1 receptors are located near the thermoregulatory center of the hypothalamus. Increased body temperature with hot bathing may counteract the thermoregulatory dysregulation associated with Cannabis use.4,9 It has been proposed that splanchnic vasodilation might contribute to CHS symptoms. Thus, redistribution of blood from the gut to the skin with warm bathing causes a “cutaneous steal syndrome,” resulting in symptom relief.11

Diagnostic approach

Four key features should be present when making a diagnosis of CHS:

- heavy marijuana use

- recurrent episodes of severe nausea, vomiting, and abdominal cramping

- compulsive bathing for transient symptom relief

- resolution of symptoms with cessation of Cannabis use.2,4,8

Compulsive, hot bathing for symptom relief was described in 98% of all reported cases,3 and should be considered pathognomonic.2 CHS patients can present with other symptoms, including polydipsia, mild fever, weight loss, and orthostasis.3 Although lab studies usually are normal, mild leukocytosis, hypokalemia, hypochloremia, elevated salivary amylase, mild gastritis on esophagogastroduodenoscopy, and delayed gastric emptying have been described during acute episodes (Table 1).2-4,7,8

Diagnosis starts with a history and physical exam, followed by a basic workup geared towards ruling out other causes of acute nausea and vomiting.2,7 Establish temporal relationships between symptoms, Cannabis use (onset, frequency, amount, duration), and bathing behaviors. A positive urine toxicology screen supports a CHS diagnosis and can facilitate discussion of Cannabis use.2 If you suspect CHS, rule out potentially life-threatening causes of acute nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, such as intestinal obstruction or perforation, pancreaticobiliary disease, and pregnancy. The initial workup should include a CBC, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, amylase, lipase, pregnancy test, urinalysis, urine toxicology screen, and abdominal radiographs (Table 2).2,4,7 The differential diagnosis of recurrent vomiting is broad and should be considered (Table 3).2,4,7,16 Further workup can proceed non-emergently, and should be prompted by clinical suspicion.2,7

Supportive treatment, education

Treatment of acute hyperemetic episodes in CHS primarily is supportive; address dehydration with IV fluids and electrolyte replenishment as needed.2,4,7 Standard antiemetics, including 5-HT3 receptor antagonists, D2 receptor antagonists, and H1 receptor antagonists, are largely ineffective.5,9 Although narcotics have been used to treat abdominal pain, use caution when prescribing because they can exacerbate nausea and vomiting.7 Case reports have described symptom relief with inpatient treatment with lorazepam12 and self-medication with alprazolam,4 but more evidence is needed. A recent case report described prompt resolution of symptoms with IV haloperidol.13 Treating gastritis symptoms with acid suppression therapy, such as a proton pump inhibitor, has been suggested.7 Symptoms abate during hospitalization regardless of treatment, marking the progression into the recovery phase with abstinence. There are no proven treatments for CHS, aside from cessation of Cannabis use. Treatment should focus on motivating your patient to stop using Cannabis.

Acute, hyperemetic episodes are ideal teachable moments because of the acuity of symptoms and clear association with Cannabis use. However, some patients may be skeptical about CHS because of the better-known antiemetic effects of Cannabis. For such patients, provide informational materials describing CHS and take time to address their concerns or doubts.

Motivational interviewing can help provoke behavior change by exploring patient ambivalence in a directive, patient-focused manner. Randomized controlled trials have documented significant reductions in Cannabis use with single-session motivational interviewing, with greater effect among heavy users.17 Single-session motivational interviewing showed results comparable to providing drug information and advice, suggesting that education and information are useful interventions.18 Although these single-session studies appear promising, they focus on younger users who have not been using Cannabis as long as typical CHS patients. Multi-session interventions may be needed to address longstanding, heavy Cannabis use in adult CHS patients.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy. In a series of randomized controlled trials,

motivational enhancement training and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) were effective for Cannabis use cessation and maintenance of abstinence.19

Although these interventions take more time—six to 14 sessions for CBT and one to four sessions for motivational enhancement training—they should be considered for CHS patients with persistent use.

Bottom Line

Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) is characterized by years of daily, heavy Cannabis use, cyclic nausea and vomiting, and compulsive bathing. Symptoms resolve with Cannabis cessation. Workup of suspected CHS should rule out life- threatening causes of nausea and vomiting. Acute hyperemetic episodes should be managed supportively. Motivational enhancement therapy or cognitive-behavioral therapy should be considered for persistent Cannibis use.

Related Resources

- Motivational interviewing for substance use disorders. www.motivationalinterview.org.

- Danovitch I, Gorelick DA. State of the art treatments for cannabis dependence. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2012;35(2):309-326.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax Haloperidol • Haldol Lorazepam • Ativan

Ondansetron • Zofran Prochlorperazine • Compazine

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Cannabis is the most commonly abused drug in the United States. Since 2008, Cannabis use has significantly increased,1 in part because of legalization for medicinal and recreational use. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) is characterized by years of daily Cannabis use, recurrent nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain, compulsive bathing for symptom relief, and symptom resolution with cessation of use.

Prompt recognition of CHS can reduce costs associated with unnecessary workups, emergency department (ED) and urgent care visits, and hospital admissions.2,3 This article provides a review of CHS with discussion of diagnostic and management considerations.

CASE REPORT Nauseated and vomiting—and stoned

Mr. M, age 24, self-presents to the ED complaining of two days of severe nausea, colicky abdominal pain, and nonbloody, nonbilious vomiting, as often as 20 times a day. His symptoms become worse with food, and he has difficulty eating and drinking because of his vomiting. Mr. M reports transient symptom relief when he takes hot showers, and has been taking more than 14 showers a day. He reports similar episodes, occurring every two or three months over the last two years, resulting in several ED visits and three hospital admissions.

Mr. M has smoked two to three joints a day for seven years; he has increased his Cannabis use in an attempt to alleviate his symptoms, but isn’t sure if doing so was helpful. He denies use of tobacco and other illicit drugs, and reports drinking one to three drinks no more than twice a month. He reports dizziness when standing, but no other symptoms. He does not take any medications, and medical and psychiatric histories are unremarkable.

Physical exam reveals a thin, uncomfortable, young man. Vital signs were significant for tachycardia and mild orthostatic hypotension. His abdomen was diffusely tender, soft, and nondistended. Urine toxicology is positive for delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) only. Labs, including a complete blood count (CBC), basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, and lipase, are within normal limits. Prior workup included abdominal radiographs, abdominal ultrasonography, abdominal CT, and gastric biopsy; all are normal. He has mild gastritis and esophagitis on esophagogastroduodenoscopy and mildly delayed gastric emptying. HIV and hepatitis screenings are negative. Six months ago he received antibiotic therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection.

Mr. M is admitted to the hospital and seen by the psychiatric consultation service. He is treated with IV ondansetron and prochlorperazine, with little effect. He showers frequently until his symptoms begin to abate within 36 hours of stopping Cannabis use, and is discharged soon after. Psychiatric clinicians provide brief motivational interviewing while Mr. M is in the hospital, and refer him to outpatient psychiatric care and Narcotics Anonymous. Mr. M is then lost to follow up.

In 2011, 18.1 million people reported Cannabis use in the previous month; 39% reported use in 20 of the last 30 days.1 A high rate of use and a relatively low number of cases suggests that CHS is rare. However, it is likely that CHS is under-recognized and under-reported.2,4,5 CHS symptoms may be misattributed to cyclic vomiting syndrome,3 because 50% of patients diagnosed with cyclic vomiting syndrome report daily Cannabis use.6 There is no epidemiological data on the incidence or prevalence of CHS among regular Cannabis users.7

Allen and colleagues first described this syndrome in 2004.4 Since then, CHS has been documented in a growing number of case reports and reviews,2,3,5,7-13 yet it continues to be under-recognized. Many CHS patients experience delays in diagnosis—often years—resulting in prolonged suffering, and costs incurred by frequent ED and urgent care visits, hospital admissions, and unnecessary workups.2,3,7

Clinical characteristics

CHS is characterized by recurrent, hyperemetic episodes in the context of chronic, daily Cannabis use.4 The average age of onset is 25.6 years (range: 16 to 51 years).3 Ninety-five percent of CHS patients used Cannabis daily, for, on average, 9.8 years before symptom onset.3 The amount of Cannabis used, although generally high, is difficult to quantify, and has been described as heavy and hourly in units of blunts, cones, joints, bongs, etc. Patients are most likely to present during acute hyperemetic episodes, which occur in a cyclic pattern, every four to eight weeks,3 interspersed with symptom-free periods. Three phases have been described:

- prodromal or pre-emetic phase

- hyperemetic phase

- recovery phase.4,10

Many patients report a prodromal phase, with one or two weeks of morning nausea, food aversion, preserved eating patterns, possible weight loss, and occasional vomiting. The acute, hyperemetic phase is characterized by severe nausea, frequent vomiting, abdominal pain, and compulsive bathing for temporary symptom relief. In the recovery phase, symptom improvement and resolution occur with cessation of Cannabis use.4,10 Symptom improvement can occur within 12 hours of Cannabis cessation, but can take as long as three weeks.3 Patients remain symptom-free while abstinent, but symptoms rapidly recur when they resume use.3,4

Cannabis is used as an antiemetic and appetite stimulant for chemotherapy-associated nausea and for anorexia in HIV infection. The pathogenesis of paradoxical hyperemetic symptoms of CHS remain unclear, but several mechanisms have been proposed. The principle active cannabinoid in Cannabis is the highly lipophilic compound THC, which binds to cannabinoid type 1 (CB1) and type 2 (CB2) receptors in the CNS and other tissues. It is thought that the antiemetic and appetite-stimulating effects of Cannabis are mediated by CB1 receptor activation in the hypothalamus. Nausea and vomiting are thought to be mediated by CB1 receptor activation in the enteric nervous system, which causes slowed peristalsis, delayed gastric emptying, and splanchnic vasodilation.4,14

In sensitive persons, chronic heavy Cannabis use can cause THC to accumulate to a toxic level in fatty tissues, causing enteric receptor binding effects to override the CNS receptor-binding effects.4 This is supported by case studies describing severe vomiting with IV injection of crude marijuana extract.15 Nearly 100 different THC metabolites have been identified. The Cannabis plant contains more than 400 chemicals, with 60 cannabinoid structures, any of which could cause CHS in toxic concentrations.4,7 Among them, cannabidiol, a 5-HT1A partial agonist, was shown to cause vomiting at higher doses in animal studies.4,7

Mechanisms of action

Cannabis has been used for centuries, so it is unclear why CHS is only recently being recognized. It may be because of higher THC content through selective breeding of plants and a more selective use of female buds that contain more concentrated THC levels than leaves and stems.3 Alternately, CHS may be caused by exogenous substances, such as pesticides, additives, preservatives, or other chemicals used in marijuana preparation, although there is little evidence to support this.3

The mechanism of symptom relief with hot bathing also is unclear. Patients report consistent, global symptom improvement with hot bathing.3 Relief is rapid, transient, and temperature dependent.4 CB1 receptors are located near the thermoregulatory center of the hypothalamus. Increased body temperature with hot bathing may counteract the thermoregulatory dysregulation associated with Cannabis use.4,9 It has been proposed that splanchnic vasodilation might contribute to CHS symptoms. Thus, redistribution of blood from the gut to the skin with warm bathing causes a “cutaneous steal syndrome,” resulting in symptom relief.11

Diagnostic approach

Four key features should be present when making a diagnosis of CHS:

- heavy marijuana use

- recurrent episodes of severe nausea, vomiting, and abdominal cramping

- compulsive bathing for transient symptom relief

- resolution of symptoms with cessation of Cannabis use.2,4,8

Compulsive, hot bathing for symptom relief was described in 98% of all reported cases,3 and should be considered pathognomonic.2 CHS patients can present with other symptoms, including polydipsia, mild fever, weight loss, and orthostasis.3 Although lab studies usually are normal, mild leukocytosis, hypokalemia, hypochloremia, elevated salivary amylase, mild gastritis on esophagogastroduodenoscopy, and delayed gastric emptying have been described during acute episodes (Table 1).2-4,7,8

Diagnosis starts with a history and physical exam, followed by a basic workup geared towards ruling out other causes of acute nausea and vomiting.2,7 Establish temporal relationships between symptoms, Cannabis use (onset, frequency, amount, duration), and bathing behaviors. A positive urine toxicology screen supports a CHS diagnosis and can facilitate discussion of Cannabis use.2 If you suspect CHS, rule out potentially life-threatening causes of acute nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, such as intestinal obstruction or perforation, pancreaticobiliary disease, and pregnancy. The initial workup should include a CBC, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, amylase, lipase, pregnancy test, urinalysis, urine toxicology screen, and abdominal radiographs (Table 2).2,4,7 The differential diagnosis of recurrent vomiting is broad and should be considered (Table 3).2,4,7,16 Further workup can proceed non-emergently, and should be prompted by clinical suspicion.2,7

Supportive treatment, education

Treatment of acute hyperemetic episodes in CHS primarily is supportive; address dehydration with IV fluids and electrolyte replenishment as needed.2,4,7 Standard antiemetics, including 5-HT3 receptor antagonists, D2 receptor antagonists, and H1 receptor antagonists, are largely ineffective.5,9 Although narcotics have been used to treat abdominal pain, use caution when prescribing because they can exacerbate nausea and vomiting.7 Case reports have described symptom relief with inpatient treatment with lorazepam12 and self-medication with alprazolam,4 but more evidence is needed. A recent case report described prompt resolution of symptoms with IV haloperidol.13 Treating gastritis symptoms with acid suppression therapy, such as a proton pump inhibitor, has been suggested.7 Symptoms abate during hospitalization regardless of treatment, marking the progression into the recovery phase with abstinence. There are no proven treatments for CHS, aside from cessation of Cannabis use. Treatment should focus on motivating your patient to stop using Cannabis.

Acute, hyperemetic episodes are ideal teachable moments because of the acuity of symptoms and clear association with Cannabis use. However, some patients may be skeptical about CHS because of the better-known antiemetic effects of Cannabis. For such patients, provide informational materials describing CHS and take time to address their concerns or doubts.

Motivational interviewing can help provoke behavior change by exploring patient ambivalence in a directive, patient-focused manner. Randomized controlled trials have documented significant reductions in Cannabis use with single-session motivational interviewing, with greater effect among heavy users.17 Single-session motivational interviewing showed results comparable to providing drug information and advice, suggesting that education and information are useful interventions.18 Although these single-session studies appear promising, they focus on younger users who have not been using Cannabis as long as typical CHS patients. Multi-session interventions may be needed to address longstanding, heavy Cannabis use in adult CHS patients.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy. In a series of randomized controlled trials,

motivational enhancement training and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) were effective for Cannabis use cessation and maintenance of abstinence.19

Although these interventions take more time—six to 14 sessions for CBT and one to four sessions for motivational enhancement training—they should be considered for CHS patients with persistent use.

Bottom Line

Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) is characterized by years of daily, heavy Cannabis use, cyclic nausea and vomiting, and compulsive bathing. Symptoms resolve with Cannabis cessation. Workup of suspected CHS should rule out life- threatening causes of nausea and vomiting. Acute hyperemetic episodes should be managed supportively. Motivational enhancement therapy or cognitive-behavioral therapy should be considered for persistent Cannibis use.

Related Resources

- Motivational interviewing for substance use disorders. www.motivationalinterview.org.

- Danovitch I, Gorelick DA. State of the art treatments for cannabis dependence. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2012;35(2):309-326.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax Haloperidol • Haldol Lorazepam • Ativan

Ondansetron • Zofran Prochlorperazine • Compazine

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Mental health findings. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2k11MH_FindingsandDetTables/2K11MHFR/NSDUHmhfr2011.htm. Published November 2012. Accessed April 18, 2013.

2. Wallace EA, Andrews SE, Garmany CL, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: literature review and proposed diagnosis and treatment algorithm. South Med J. 2011; 104(9):659-664.

3. Nicolson SE, Denysenko L, Mulcare JL, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: a case series and review of previous reports. Psychosomatics. 2012;53(3):212-219.

4. Allen JH, de Moore GM, Heddle R, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis: cyclical hyperemesis in association with chronic cannabis abuse. Cut. 2004;53(11):1566-1570.

5. Sontineni SP, Chaudhary S, Sontineni V, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: clinical diagnosis of an underrecognised manifestation of chronic cannabis abuse. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(10):1264-1266.

6. Fajardo NR, Cremonini F, Talley NJ. Cyclic vomiting syndrome and chronic cannabis use. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:S343.

7. Galli JA, Sawaya RA, Friedenberg FK. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2011;4(4):241-249.

8. Sullivan S. Cannabinoid hyperemesis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24(5):284-285.

9. Chang YH, Windish DM. Cannabinoid hyperemesis relieved by compulsive bathing. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(1):76-78.

10. Soriano-Co M, Batke M, Cappell MS. The cannabis hyperemesis syndrome characterized by persistent nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, and compulsive bathing associated with chronic marijuana use: a report of eight cases in the United States. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(11):3113-3119.

11. Patterson DA, Smith E, Monahan M, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis and compulsive bathing: a case series and paradoxical pathophysiological explanation. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(6):790-793.

12. Cox B, Chhabra A, Adler M, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: case report of a paradoxical reaction with heavy marijuana use. Case Rep Med. 2012;2012:757696.

13. Hickey JL, Witsil JC, Mycyk MB. Haloperidol for treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome [published online April 10, 2013]. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(6):1003.e5-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.02.021.

14. McCallum RW, Soykan I, Sridhar KR, et al. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol delays the gastric emptying of solid food in humans: a double-blind, randomized study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13(1):77-80.

15. Vaziri ND, Thomas R, Sterling M, et al. Toxicity with intravenous injection of crude marijuana extract. Clin Toxicol. 1981;18(3):353-366.

16. Abell TL, Adams KA, Boles RG, et al. Cyclic vomiting syndrome in adults. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008; 20(4):269-284.

17. McCambridge J, Strang J. The efficacy of single-session motivational interviewing in reducing drug consumption and perceptions of drug-related risk and harm among young people: results from a multi-site cluster randomized trial. Addiction. 2004;99(1):39-52.

18. McCambridge J, Slym RL, Strang J. Randomized controlled trial of motivational interviewing compared with drug information and advice for early intervention among young cannabis users. Addiction. 2008;103(11):1809-1818.

19. Elkashef A, Vocci F, Huestis M, et al. Marijuana neurobiology and treatment. Subst Abus. 2008;29(3):17-29.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Mental health findings. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2k11MH_FindingsandDetTables/2K11MHFR/NSDUHmhfr2011.htm. Published November 2012. Accessed April 18, 2013.

2. Wallace EA, Andrews SE, Garmany CL, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: literature review and proposed diagnosis and treatment algorithm. South Med J. 2011; 104(9):659-664.

3. Nicolson SE, Denysenko L, Mulcare JL, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: a case series and review of previous reports. Psychosomatics. 2012;53(3):212-219.

4. Allen JH, de Moore GM, Heddle R, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis: cyclical hyperemesis in association with chronic cannabis abuse. Cut. 2004;53(11):1566-1570.

5. Sontineni SP, Chaudhary S, Sontineni V, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: clinical diagnosis of an underrecognised manifestation of chronic cannabis abuse. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(10):1264-1266.

6. Fajardo NR, Cremonini F, Talley NJ. Cyclic vomiting syndrome and chronic cannabis use. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:S343.

7. Galli JA, Sawaya RA, Friedenberg FK. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2011;4(4):241-249.

8. Sullivan S. Cannabinoid hyperemesis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24(5):284-285.

9. Chang YH, Windish DM. Cannabinoid hyperemesis relieved by compulsive bathing. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(1):76-78.

10. Soriano-Co M, Batke M, Cappell MS. The cannabis hyperemesis syndrome characterized by persistent nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, and compulsive bathing associated with chronic marijuana use: a report of eight cases in the United States. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(11):3113-3119.

11. Patterson DA, Smith E, Monahan M, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis and compulsive bathing: a case series and paradoxical pathophysiological explanation. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(6):790-793.

12. Cox B, Chhabra A, Adler M, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: case report of a paradoxical reaction with heavy marijuana use. Case Rep Med. 2012;2012:757696.

13. Hickey JL, Witsil JC, Mycyk MB. Haloperidol for treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome [published online April 10, 2013]. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(6):1003.e5-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.02.021.

14. McCallum RW, Soykan I, Sridhar KR, et al. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol delays the gastric emptying of solid food in humans: a double-blind, randomized study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13(1):77-80.

15. Vaziri ND, Thomas R, Sterling M, et al. Toxicity with intravenous injection of crude marijuana extract. Clin Toxicol. 1981;18(3):353-366.

16. Abell TL, Adams KA, Boles RG, et al. Cyclic vomiting syndrome in adults. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008; 20(4):269-284.

17. McCambridge J, Strang J. The efficacy of single-session motivational interviewing in reducing drug consumption and perceptions of drug-related risk and harm among young people: results from a multi-site cluster randomized trial. Addiction. 2004;99(1):39-52.

18. McCambridge J, Slym RL, Strang J. Randomized controlled trial of motivational interviewing compared with drug information and advice for early intervention among young cannabis users. Addiction. 2008;103(11):1809-1818.

19. Elkashef A, Vocci F, Huestis M, et al. Marijuana neurobiology and treatment. Subst Abus. 2008;29(3):17-29.