User login

Which strategies work best to prevent obesity in adults?

A/PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND DIETARY MODIFICATION WORK BEST. Family involvement, regular weight monitoring, and behavior modification also can help.

Regular physical activity decreases long-term weight gain (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, 2 high-quality, randomized controlled trials [RCTs]). Decreasing fat intake (SOR: B, 1 high-quality systematic review) and increasing fruit and vegetable consumption (SOR: B, 1 high-quality RCT) also may decrease weight gain. Combined dietary and physical activity interventions prevent weight gain (SOR: B, 1 high-quality systematic review).

Family involvement helps maintain weight (SOR:B, 2 small RCTs). Daily or weekly weight monitoring reduces long-term weight gain (SOR:B, 2 RCTs).

Clinic-based, direct-contact, and Web-based programs that include behavior modification may reduce weight gain in adults (SOR: C, 3 RCTs). Behavior modification delivered by personal contact is more effective than mail, Internet, or self-directed modification programs (SOR:B, 2 RCTs).

Evidence summary

A recent systematic review of obesity prevention studies found 9 RCTs demonstrating that dietary and physical activity interventions can prevent weight gain, but lacking sufficient evidence to recommend a specific type of program.1

A systematic review of the effects of physical activity on weight reduction and maintenance analyzed 46 studies, including 8 RCTs that investigated interventions to reduce weight and 3 that examined measures to maintain it.2 More than 80% of the studies showed a benefit from physical exercise. Prevention of weight gain appears to be dose-dependent. More exercise leads to less weight gain; a minimum of 1.5 hours per week of moderate exercise is needed to prevent weight gain.2

Less fat, more vegetables spur weight loss

The Women’s Health Initiative studied 46,808 postmenopausal women between 50 and 79 years of age who were randomly assigned to an intervention or control group.3 The intervention group received intensive group and individual counseling from dieticians aimed at reducing fat intake to 20%, increasing consumption of vegetables and fruits to 5 or more servings per day, and increasing consumption of grains to 6 or more servings per day. The control group received dietary education materials. Neither group had weight loss or calorie restriction goals or differences in physical activity.

The intervention group had a mean decrease in weight 1.9 kg greater than the controls at 1 year (P<.001) and 0.4 kg at 7.5 years (P<.01). Weight loss was greater in women who consumed more fruits and vegetables and greatest among women who decreased energy intake from fat.

A family-based intervention lowers BMI in females

A family-based trial of weight gain prevention randomized 82 families to a group that was encouraged to eat 2 servings of cereal a day and increase activity by 2000 steps a day, or to a control group.4 In the intervention group, body mass index (BMI) decreased by 0.4% in mothers (P=.027), and BMI percentage for age decreased by 2.6% in daughters (P<.01). Male family members showed no significant differences, however.

Family ties, self-weighing improve weight control

A systematic review of family-spouse involvement in weight control and weight loss found that involving spouses tended to improve the effectiveness of weight control.5

Two studies, 1 an RCT, found an association between self-weighing and preventing weight gain.6,7 Patients who weighed themselves daily or weekly were less likely to gain weight than patients who weighed themselves monthly, yearly, or never.

Getting personal helps modify behavior

Three RCTs compared clinic-based, Web-based, and self-directed advice and counseling to prevent weight gain (2 studies) and maintain weight loss (1 study). In the first study, 67 patients were assigned to 4 months of clinic-based or home-based counseling to increase exercise and reduce fat intake, or to a control group.8 Weight change was–1.9 kg in the clinic-based group,–1.3 kg in the home-based group, and +0.22 kg in the control group (P=.007).

In the second study, 1032 overweight or obese adults with hypertension and/or dyslipidemia who completed a weight-loss program were randomly assigned to receive monthly personal contact, unlimited access to a Web-based intervention, or a self-directed control group.9 At 30 months, participants in the personal contact group had regained less weight than the Web-based or control groups (4.0, 5.1, and 5.5 kg, respectively; P<.01).

A third RCT randomized 284 healthy 25- to 44-year-old women with BMI <30 kg/m2 to group meetings, lessons by mail, or a control group that received an information booklet. The study found no significant difference among the 3 groups in weight maintenance at a 3-year follow-up; 40% maintained weight, and 60% gained more than 2 pounds.10

Recommendations

Wide consensus supports screening by either BMI or height and weight. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends intensive counseling for everyone with a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 coupled with behavioral modification to promote sustained weight loss.11 The USPSTF found insufficient evidence to support less intensive counseling for obese patients or counseling of any intensity for overweight patients.

The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against BMI measurement during routine health evaluations of the general population.12

The American Diabetes Association13 and the American College of Preventive Medicine14 recommend counseling and behavior modification for all adults to prevent obesity.

1. Lemmens VE, Oenema A, Klepp KI, et al. A systematic review of the evidence regarding efficacy of obesity prevention interventions among adults. Obes Rev. 2008;9:446-455.

2. Fogelholm M, Kukkonen-Harjula K. Does physical activity prevent weight gain—a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2000;1:95-111.

3. Howard BV, Manson JE, Stefanick ML, et al. Low-fat dietary pattern and weight change over 7 years: the Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification Trial. JAMA. 2006;295:39-49.

4. Rodearmel SJ, Wyatt HR, Barry MJ, et al. A family-based approach to preventing excessive weight gain. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14:1392-1401.

5. McLean N, Griffin S, Toney K, et al. Family involvement in weight control, weight maintenance and weight-loss interventions: a systematic review of randomised trials. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:987-1005.

6. Linde JA, Jeffery RW, French SA, et al. Self-weighing in weight gain prevention and weight loss trials. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30:210-216.

7. Levitsky DA, Garay J, Nausbaum M, et al. Monitoring weight daily blocks the freshman weight gain: a model for combating the epidemic of obesity. Int J Obes (London). 2006;30:1003-1010.

8. Leermarkers EA, Jakicic JM, Viteri J, et al. Clinic-based vs. home-based interventions for preventing weight gain in men. Obes Res. 1998;6:346-352.

9. Svetkey LP, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ, et al. Comparison of strategies for sustaining weight loss: the weight loss maintenance randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1139-1148.

10. Levine MD, Klem ML, Kalarchian MA, et al. Weight gain prevention among women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15:1267-1277.

11. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Obesity in Adults. Rockville, Md: AHRQ; December 2003. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsobes.htm. Accessed May 6, 2008.

12. Douketis JD, Feightner JW, Attia J, et al. Periodic health examination, 1999 update: 1. detection, prevention and treatment of obesity. Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. CMAJ. 1999;160:513-525.

13. Franz MJ, Bantle JP, Beebe CA, et al. Evidence-based nutrition principles and recommendations for the treatment and prevention of diabetes and related complications. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:148-198.

14. Nawaz H, Katz D. American College of Preventive Medicine Medical Practice Policy Statement. Weight management counseling for overweight adults. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21:73-78.

A/PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND DIETARY MODIFICATION WORK BEST. Family involvement, regular weight monitoring, and behavior modification also can help.

Regular physical activity decreases long-term weight gain (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, 2 high-quality, randomized controlled trials [RCTs]). Decreasing fat intake (SOR: B, 1 high-quality systematic review) and increasing fruit and vegetable consumption (SOR: B, 1 high-quality RCT) also may decrease weight gain. Combined dietary and physical activity interventions prevent weight gain (SOR: B, 1 high-quality systematic review).

Family involvement helps maintain weight (SOR:B, 2 small RCTs). Daily or weekly weight monitoring reduces long-term weight gain (SOR:B, 2 RCTs).

Clinic-based, direct-contact, and Web-based programs that include behavior modification may reduce weight gain in adults (SOR: C, 3 RCTs). Behavior modification delivered by personal contact is more effective than mail, Internet, or self-directed modification programs (SOR:B, 2 RCTs).

Evidence summary

A recent systematic review of obesity prevention studies found 9 RCTs demonstrating that dietary and physical activity interventions can prevent weight gain, but lacking sufficient evidence to recommend a specific type of program.1

A systematic review of the effects of physical activity on weight reduction and maintenance analyzed 46 studies, including 8 RCTs that investigated interventions to reduce weight and 3 that examined measures to maintain it.2 More than 80% of the studies showed a benefit from physical exercise. Prevention of weight gain appears to be dose-dependent. More exercise leads to less weight gain; a minimum of 1.5 hours per week of moderate exercise is needed to prevent weight gain.2

Less fat, more vegetables spur weight loss

The Women’s Health Initiative studied 46,808 postmenopausal women between 50 and 79 years of age who were randomly assigned to an intervention or control group.3 The intervention group received intensive group and individual counseling from dieticians aimed at reducing fat intake to 20%, increasing consumption of vegetables and fruits to 5 or more servings per day, and increasing consumption of grains to 6 or more servings per day. The control group received dietary education materials. Neither group had weight loss or calorie restriction goals or differences in physical activity.

The intervention group had a mean decrease in weight 1.9 kg greater than the controls at 1 year (P<.001) and 0.4 kg at 7.5 years (P<.01). Weight loss was greater in women who consumed more fruits and vegetables and greatest among women who decreased energy intake from fat.

A family-based intervention lowers BMI in females

A family-based trial of weight gain prevention randomized 82 families to a group that was encouraged to eat 2 servings of cereal a day and increase activity by 2000 steps a day, or to a control group.4 In the intervention group, body mass index (BMI) decreased by 0.4% in mothers (P=.027), and BMI percentage for age decreased by 2.6% in daughters (P<.01). Male family members showed no significant differences, however.

Family ties, self-weighing improve weight control

A systematic review of family-spouse involvement in weight control and weight loss found that involving spouses tended to improve the effectiveness of weight control.5

Two studies, 1 an RCT, found an association between self-weighing and preventing weight gain.6,7 Patients who weighed themselves daily or weekly were less likely to gain weight than patients who weighed themselves monthly, yearly, or never.

Getting personal helps modify behavior

Three RCTs compared clinic-based, Web-based, and self-directed advice and counseling to prevent weight gain (2 studies) and maintain weight loss (1 study). In the first study, 67 patients were assigned to 4 months of clinic-based or home-based counseling to increase exercise and reduce fat intake, or to a control group.8 Weight change was–1.9 kg in the clinic-based group,–1.3 kg in the home-based group, and +0.22 kg in the control group (P=.007).

In the second study, 1032 overweight or obese adults with hypertension and/or dyslipidemia who completed a weight-loss program were randomly assigned to receive monthly personal contact, unlimited access to a Web-based intervention, or a self-directed control group.9 At 30 months, participants in the personal contact group had regained less weight than the Web-based or control groups (4.0, 5.1, and 5.5 kg, respectively; P<.01).

A third RCT randomized 284 healthy 25- to 44-year-old women with BMI <30 kg/m2 to group meetings, lessons by mail, or a control group that received an information booklet. The study found no significant difference among the 3 groups in weight maintenance at a 3-year follow-up; 40% maintained weight, and 60% gained more than 2 pounds.10

Recommendations

Wide consensus supports screening by either BMI or height and weight. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends intensive counseling for everyone with a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 coupled with behavioral modification to promote sustained weight loss.11 The USPSTF found insufficient evidence to support less intensive counseling for obese patients or counseling of any intensity for overweight patients.

The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against BMI measurement during routine health evaluations of the general population.12

The American Diabetes Association13 and the American College of Preventive Medicine14 recommend counseling and behavior modification for all adults to prevent obesity.

A/PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND DIETARY MODIFICATION WORK BEST. Family involvement, regular weight monitoring, and behavior modification also can help.

Regular physical activity decreases long-term weight gain (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, 2 high-quality, randomized controlled trials [RCTs]). Decreasing fat intake (SOR: B, 1 high-quality systematic review) and increasing fruit and vegetable consumption (SOR: B, 1 high-quality RCT) also may decrease weight gain. Combined dietary and physical activity interventions prevent weight gain (SOR: B, 1 high-quality systematic review).

Family involvement helps maintain weight (SOR:B, 2 small RCTs). Daily or weekly weight monitoring reduces long-term weight gain (SOR:B, 2 RCTs).

Clinic-based, direct-contact, and Web-based programs that include behavior modification may reduce weight gain in adults (SOR: C, 3 RCTs). Behavior modification delivered by personal contact is more effective than mail, Internet, or self-directed modification programs (SOR:B, 2 RCTs).

Evidence summary

A recent systematic review of obesity prevention studies found 9 RCTs demonstrating that dietary and physical activity interventions can prevent weight gain, but lacking sufficient evidence to recommend a specific type of program.1

A systematic review of the effects of physical activity on weight reduction and maintenance analyzed 46 studies, including 8 RCTs that investigated interventions to reduce weight and 3 that examined measures to maintain it.2 More than 80% of the studies showed a benefit from physical exercise. Prevention of weight gain appears to be dose-dependent. More exercise leads to less weight gain; a minimum of 1.5 hours per week of moderate exercise is needed to prevent weight gain.2

Less fat, more vegetables spur weight loss

The Women’s Health Initiative studied 46,808 postmenopausal women between 50 and 79 years of age who were randomly assigned to an intervention or control group.3 The intervention group received intensive group and individual counseling from dieticians aimed at reducing fat intake to 20%, increasing consumption of vegetables and fruits to 5 or more servings per day, and increasing consumption of grains to 6 or more servings per day. The control group received dietary education materials. Neither group had weight loss or calorie restriction goals or differences in physical activity.

The intervention group had a mean decrease in weight 1.9 kg greater than the controls at 1 year (P<.001) and 0.4 kg at 7.5 years (P<.01). Weight loss was greater in women who consumed more fruits and vegetables and greatest among women who decreased energy intake from fat.

A family-based intervention lowers BMI in females

A family-based trial of weight gain prevention randomized 82 families to a group that was encouraged to eat 2 servings of cereal a day and increase activity by 2000 steps a day, or to a control group.4 In the intervention group, body mass index (BMI) decreased by 0.4% in mothers (P=.027), and BMI percentage for age decreased by 2.6% in daughters (P<.01). Male family members showed no significant differences, however.

Family ties, self-weighing improve weight control

A systematic review of family-spouse involvement in weight control and weight loss found that involving spouses tended to improve the effectiveness of weight control.5

Two studies, 1 an RCT, found an association between self-weighing and preventing weight gain.6,7 Patients who weighed themselves daily or weekly were less likely to gain weight than patients who weighed themselves monthly, yearly, or never.

Getting personal helps modify behavior

Three RCTs compared clinic-based, Web-based, and self-directed advice and counseling to prevent weight gain (2 studies) and maintain weight loss (1 study). In the first study, 67 patients were assigned to 4 months of clinic-based or home-based counseling to increase exercise and reduce fat intake, or to a control group.8 Weight change was–1.9 kg in the clinic-based group,–1.3 kg in the home-based group, and +0.22 kg in the control group (P=.007).

In the second study, 1032 overweight or obese adults with hypertension and/or dyslipidemia who completed a weight-loss program were randomly assigned to receive monthly personal contact, unlimited access to a Web-based intervention, or a self-directed control group.9 At 30 months, participants in the personal contact group had regained less weight than the Web-based or control groups (4.0, 5.1, and 5.5 kg, respectively; P<.01).

A third RCT randomized 284 healthy 25- to 44-year-old women with BMI <30 kg/m2 to group meetings, lessons by mail, or a control group that received an information booklet. The study found no significant difference among the 3 groups in weight maintenance at a 3-year follow-up; 40% maintained weight, and 60% gained more than 2 pounds.10

Recommendations

Wide consensus supports screening by either BMI or height and weight. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends intensive counseling for everyone with a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 coupled with behavioral modification to promote sustained weight loss.11 The USPSTF found insufficient evidence to support less intensive counseling for obese patients or counseling of any intensity for overweight patients.

The Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against BMI measurement during routine health evaluations of the general population.12

The American Diabetes Association13 and the American College of Preventive Medicine14 recommend counseling and behavior modification for all adults to prevent obesity.

1. Lemmens VE, Oenema A, Klepp KI, et al. A systematic review of the evidence regarding efficacy of obesity prevention interventions among adults. Obes Rev. 2008;9:446-455.

2. Fogelholm M, Kukkonen-Harjula K. Does physical activity prevent weight gain—a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2000;1:95-111.

3. Howard BV, Manson JE, Stefanick ML, et al. Low-fat dietary pattern and weight change over 7 years: the Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification Trial. JAMA. 2006;295:39-49.

4. Rodearmel SJ, Wyatt HR, Barry MJ, et al. A family-based approach to preventing excessive weight gain. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14:1392-1401.

5. McLean N, Griffin S, Toney K, et al. Family involvement in weight control, weight maintenance and weight-loss interventions: a systematic review of randomised trials. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:987-1005.

6. Linde JA, Jeffery RW, French SA, et al. Self-weighing in weight gain prevention and weight loss trials. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30:210-216.

7. Levitsky DA, Garay J, Nausbaum M, et al. Monitoring weight daily blocks the freshman weight gain: a model for combating the epidemic of obesity. Int J Obes (London). 2006;30:1003-1010.

8. Leermarkers EA, Jakicic JM, Viteri J, et al. Clinic-based vs. home-based interventions for preventing weight gain in men. Obes Res. 1998;6:346-352.

9. Svetkey LP, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ, et al. Comparison of strategies for sustaining weight loss: the weight loss maintenance randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1139-1148.

10. Levine MD, Klem ML, Kalarchian MA, et al. Weight gain prevention among women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15:1267-1277.

11. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Obesity in Adults. Rockville, Md: AHRQ; December 2003. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsobes.htm. Accessed May 6, 2008.

12. Douketis JD, Feightner JW, Attia J, et al. Periodic health examination, 1999 update: 1. detection, prevention and treatment of obesity. Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. CMAJ. 1999;160:513-525.

13. Franz MJ, Bantle JP, Beebe CA, et al. Evidence-based nutrition principles and recommendations for the treatment and prevention of diabetes and related complications. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:148-198.

14. Nawaz H, Katz D. American College of Preventive Medicine Medical Practice Policy Statement. Weight management counseling for overweight adults. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21:73-78.

1. Lemmens VE, Oenema A, Klepp KI, et al. A systematic review of the evidence regarding efficacy of obesity prevention interventions among adults. Obes Rev. 2008;9:446-455.

2. Fogelholm M, Kukkonen-Harjula K. Does physical activity prevent weight gain—a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2000;1:95-111.

3. Howard BV, Manson JE, Stefanick ML, et al. Low-fat dietary pattern and weight change over 7 years: the Women’s Health Initiative Dietary Modification Trial. JAMA. 2006;295:39-49.

4. Rodearmel SJ, Wyatt HR, Barry MJ, et al. A family-based approach to preventing excessive weight gain. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14:1392-1401.

5. McLean N, Griffin S, Toney K, et al. Family involvement in weight control, weight maintenance and weight-loss interventions: a systematic review of randomised trials. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:987-1005.

6. Linde JA, Jeffery RW, French SA, et al. Self-weighing in weight gain prevention and weight loss trials. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30:210-216.

7. Levitsky DA, Garay J, Nausbaum M, et al. Monitoring weight daily blocks the freshman weight gain: a model for combating the epidemic of obesity. Int J Obes (London). 2006;30:1003-1010.

8. Leermarkers EA, Jakicic JM, Viteri J, et al. Clinic-based vs. home-based interventions for preventing weight gain in men. Obes Res. 1998;6:346-352.

9. Svetkey LP, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ, et al. Comparison of strategies for sustaining weight loss: the weight loss maintenance randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1139-1148.

10. Levine MD, Klem ML, Kalarchian MA, et al. Weight gain prevention among women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007;15:1267-1277.

11. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Obesity in Adults. Rockville, Md: AHRQ; December 2003. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspsobes.htm. Accessed May 6, 2008.

12. Douketis JD, Feightner JW, Attia J, et al. Periodic health examination, 1999 update: 1. detection, prevention and treatment of obesity. Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. CMAJ. 1999;160:513-525.

13. Franz MJ, Bantle JP, Beebe CA, et al. Evidence-based nutrition principles and recommendations for the treatment and prevention of diabetes and related complications. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:148-198.

14. Nawaz H, Katz D. American College of Preventive Medicine Medical Practice Policy Statement. Weight management counseling for overweight adults. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21:73-78.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Aspirin prophylaxis in patients at low risk for cardiovascular disease: A systematic review of all-cause mortality

- Only 3 primary prevention studies of aspirin included low-risk subjects and measured all-cause mortality.

- Two of those studies demonstrated no significant decrease in mortality with low-dose aspirin.

- The Nurses Health Study demonstrated a dose-dependent increase in mortality with aspirin use.

- There is insufficient evidence for or against recommending aspirin to low-risk individuals.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in the United States, and aspirin, a platelet aggregate inhibitor, is often recommended as prophylaxis for cardiovascular disease.1-3Clinical studies have demonstrated the benefit of aspirin use for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease and stroke.1,4-10 In high-risk subjects, aspirin has been proven effective in primary prevention of major cardiovascular events and nonfatal ischemic heart disease.11-13 Sanmuganathan and colleagues recently reported a meta-analysis of 4 randomized trials of aspirin for primary prevention. Although they determined that aspirin treatment is safe if the coronary event rate is at least 1.5% each year and unsafe if the rate is no higher than 0.5% each year, they did not address all-cause mortality, and 2 of the 4 trials did not include low-risk subjects.9

Many physicians and patients are prescribing aspirin with the expectation of reduced mortality in high-risk and low-risk individuals. Media advertisements and health programs may not clearly delineate the population for whom aspirin has clear benefits. A recent review suggested that aspirin is likely to be effective for primary prevention in yet to be defined groups.14 This review seeks to answer 2 questions. First, are there any primary prevention studies using aspirin that included only low-risk subjects? Second, should aspirin be prescribed routinely to persons at low risk for cardiovascular disease to decrease total mortality?

Methods

Search strategy

The MEDLINE database and the Cochrane Library were systematically searched using the terms aspirin or antiplatelet therapy and primary prevention or prevention and primary and mortality. An additional search was made with primary prevention and myocardial infarction or stroke. The Internet was searched (http://www.google.com) by using the same search terms. The studies were limited to human populations. Search results consisted of abstracts, complete reviews, and reference lists from articles. Morbidity associated with aspirin use also was reviewed.

Selection criteria: end points

Only those studies that investigated primary prevention of cardiovascular disease using aspirin, had low-risk subjects, and included a measure of total mortality were part of our analysis. We used the 2001 Adult Treatment Panel III Guidelines and the recent British Medical Journal clinical evidence guidelines on primary prevention of cardiovascular disorders to define the low-risk patient.15,16 Those guidelines classified major risk factors for ischemic vascular disease as hypertension, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high lowdensity lipoprotein cholesterol, family history of premature coronary heart disease, smoking, diabetes, and advancing age (men ≥ 45 years, women ≥ 55 years). We also classified those patients with past cerebrovascular events, myocardial infarction, and angina as high risk. We defined low risk as having no more than 1 of these risk factors.

Every trial was evaluated independently by each author according to the Jadad scale.17 Based on information in the original articles, we recalculated the odds ratios (ORs) for each study. The results of the 2 randomized trails were combined by means of the Mantel-Haenszel method for combining ORs, and StatXact 4 for Windows was used for the analysis.18,19 The data were used to create a forest plot of mortal-ity.19 The decision to combine studies of like type was made a priority.

Results

MEDLINE search results for aspirin and primary prevention yielded 291 articles. Antiplatelet therapy and primary prevention yielded 64 articles. Myocardial infarction or stroke and primary prevention yielded 514 articles. Cross-referencing aspirin, prevention, and mortality yielded 690 articles. The Cochrane Library search of antiplatelet therapy and prevention and primary yielded 17 complete reviews and 6 abstracts of systematic reviews. No additional studies published or unpublished were identified through the Internet.

Five clinical trials and 1 cohort study that evaluated aspirin for primary prevention were identi-fied.11,12,20-23 One of those, a pilot study, was excluded because it did not provide mortality data for the aspirin and placebo groups.23 Two clinical trials, the Hypertension Optimal Treatment Trial and the Thrombosis Prevention Trial, did not include low-risk subjects.11,12 Although no studies were identified that included only low-risk subjects, 3 studies met our inclusion criteria. Characteristics of those 3 studies are reported in Table 1.

The US Physicians Health Study (USPHS) randomized physicians into 4 treatment groups: aspirin plus beta-carotene, aspirin plus placebo, betacarotene plus placebo, and placebo plus placebo.20 Both aspirin groups took 325 mg every other day. The mean age was 53.2 years.24 Fifty percent of the participants were current or past smokers, and 9% had hypertension. Although the rate of myocardial infarction was significantly lower in the aspirin group, there was no reduction in total cardiovascular mortality. The results are reported in Table 2. More side effects were noted in the aspirin group, including gastric ulcers, gastrointestinal bleeding, hemorrhagic stroke, and other bleeding disorders.20 No separate analysis of low-risk subjects’ risk was performed.

In the British Doctors Study (BDS), 66% of patients were randomized to take aspirin once daily and 33% were to avoid aspirin.21 More than half of the subjects were at least 60 years old. Physicians with stroke, myocardial infarction, ulcer disease, or currently taking any aspirin products were excluded. Six percent of the subjects had a history of heart disease other than myocardial infarction, 10% had hypertension, and 75% of participants were currently smoking or had a history of smoking. No significant differences were noted between groups for myocardial infarction or total mortality. By the end of the study, 44% of the aspirin group had discontinued aspirin secondary to side effects, the most common being dyspepsia. Of the control group, 2% per year started using aspirin because they developed risk factors such as vascular disease or for primary prevention. Low-risk individuals were not evaluated separately.

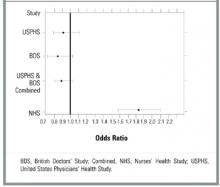

The Nurses Health Study (NHS) was a cohort study of women who were free of diagnosed coronary heart disease, stroke, and cancer at the start of the study. However, 29% of the women smoked and 15% had hypertension.22 The mean age was 46.0 years, and the follow-up was 96.7% of total potential person years. The study respondents were asked how many aspirin tablets they took per week: 0, 1 to 3, 4 to 6, 7 to 14, or 15+. Those who smoked or were overweight were more likely to take aspirin. No separate analysis of low-risk subjects was performed. Mortality from aspirin use was clearly dose dependent. For study participants taking 1 to 6 aspirin tablets each week, mortality was 0.84% (OR, 1.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.26–1.82); for those taking 7 to 14 aspirin tablets, mortality was 0.99% (OR, 1.80; CI, 1.39–2.33); and for those taking 15+ aspirin tablets, mortality was 1.82% (OR, 3.32; CI, 2.62–4.21). Rates of myocardial infarction and stroke also were higher for all groups taking aspirin (see Table 2). When combined, the USPHS and the BDS demonstrated no significant difference in mortality between aspirin and placebo groups, whereas the NHS found increased mortality from aspirin (Figure).

TABLE 1

Characteristics of aspirin studies that included low-risk subjects

| USPHS | BDS | NHS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | Steering Committee20 | Peto et al21 | Manson et al22 |

| Study population | Healthy US physicians | Healthy UK physicians | Healthy US nurses |

| Study type | Randomized controlled trial | Randomized controlled trial | Cohort |

| Subjects in aspirin group | 11,037 | 3429 | 35,048 |

| Subjects in control group | 11,034 | 1710 | 52,630 |

| Treatment | 325 mg aspirin every other day | 500 mg/d aspirin | 1–15 aspirin tablets/wk |

| Comparison | Placebo | No aspirin | None |

| Follow-up time (y) | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| Jadad score | |||

| Randomization† | 1 | 2 | NA* |

| Blinding ‡ | 1 | 0 | NA |

| Withdrawals § | 1 | 0 | NA |

| Total | 3 | 2 | NA |

| Significant difference in mortality | No | No | Yes in favor of no aspirin |

| *The Jadad scale does not apply to cohort studies. | |||

| †Two points maximum. | |||

| ‡Two points maximum. | |||

| §One point maximum. | |||

| BDS, British Doctors Study; NA, not applicable; NHS, Nurses Health Study; USPHS, US Physicians Health Study. | |||

TABLE 2

Rates of myocardial infarction, stroke, total cardiovascular mortality, and total mortality in studies of aspirin vs no aspirin that included low-risk patients

| Study | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | USPHS (5 y) | BDS (6 y) | NHS (6 y) |

| Myocardial infarction | |||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 139 (1.26) | 169 (4.93) | 244 (0.70) |

| No aspirin, n (%) | 239 (2.17) | 88 (5.15) | 157 (0.30) |

| OR (CI) | 0.58 (0.47–0.71) | 0.96 (0.73–1.24) | 2.34 (1.92–2.86)* |

| Stroke | |||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 119 (1.08) | 91 (2.65) | 109 (0.31) |

| No aspirin, n (%) | 98 (0.89) | 39 (2.28) | 89 (0.17) |

| OR (CI) | 1.22 (0.93–1.59) | 1.17 (0.80–1.71) | 1.84 (1.39–2.44)* |

| Total cardiovascular mortality | |||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 81 (0.73) | 148 (4.32) | 68 (0.19) |

| No aspirin, n (%) | 83 (0.75) | 79 (4.62) | 62 (0.12) |

| OR (CI) | 0.98 (0.72–1.33) | 0.93 (0.70–1.23) | 1.65 (1.17–2.33)* |

| Total mortality | |||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 217 (1.97) | 270 (7.87) | 354 (1.01) |

| No aspirin, n (%) | 227 (2.06) | 151 (8.83) | 292 (0.55) |

| OR (CI) | 0.95 (0.79–1.15) | 0.88 (0.72–1.09) | 1.83 (1.57–2.14)* |

| *OR significant at the .05 level. | |||

| BDS, British Doctors Study; CI, 95% confidence interval; n (%), number (percentage) of patients taking or not taking aspirin; NHS, Nurses Health Study; OR, odds ratio; USPHS, US Physicians Health Study. | |||

FIGURE Forest plot of mortality in healthy patients on aspirin

Discussion

To date, there has been no study of aspirin for primary prevention that included a separate analysis of patients who were free of cardiovascular risk factors. Each of the 3 studies that included low-risk subjects grouped them with subjects at higher risk, those known to benefit from aspirin.9,11,12 Even so, none of those studies demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in all-cause mortality. Even when combined, the BDS and the USPHS demonstrated no significant improvement in mortality. Mortality in the BDS was nearly 4 times greater than that in the USPHS. This finding is likely due to the higher baseline rate of smoking and other risk factors in the British doctors. In contrast to the BDS, the USPHS demonstrated significantly decreased rates for fatal and nonfatal myocardial infarction. Our analysis of the NHS associated aspirin with increased mortality, fatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal myocardial infarction at any dose. The nurses on average had lower risk than the doctors, fewer smoked, and they were younger.

Many studies have clearly demonstrated the benefits of aspirin for primary prevention in high-risk subjects.10-12,25 There may be other benefits to taking prophylactic aspirin. In the Cancer Prevention Study II, aspirin use was associated with decreased death rates from colon cancer.26 Unfortunately, that study did not measure all-cause mortality.

There are a number of limitations to this study. There were no strictly low-risk studies of aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular mortality, and there was a paucity of studies that included low-risk subjects. Because the studies analyzed did not include only low-risk subjects, the results may not apply to all low-risk patients. The BDS did not include a placebo and was not blinded. Although not statistically significant, the ORs tended toward a protective effect for aspirin in the 2 randomized trials. The large difference in mortality between those 2 trials remains unexplained. The NHS was the only study to include women, and it was a cohort study, which is subject to selection and reporting biases. Therefore, aspirin users may have been at higher mortality risk due to smoking, obesity, or other illness, thus rendering the association between aspirin and higher mortality meaningless.

Many studies have shown significant side effects of aspirin, including epistaxis, peptic ulcer disease, gastrointestinal bleeds, and hemorrhagic stroke.15,20-22,27-32 In the BDS, 17% more subjects in the aspirin group developed peptic ulcer disease, and 19% stopped treatment during the first year secondary to gastrointestinal complaints.21

In conclusion, there is currently no evidence to recommend for or against the use of aspirin in low-risk individuals to decrease mortality. There may be other reasons to take aspirin prophylactically such as to reduce myocardial infarction or colon cancer. However, these benefits have not been established in a low-risk population. Health care providers should ask all patients whether they are taking aspirin and evaluate the risk-benefit ratio before recommending it.

1. Fuster V, Dyken M, Vokonas P, Hennekens C. Aspirin as a therapeutic agent in cardiovascular disease. Circulation 1993;87:659-75.

2. Weiss H, Aledort L. Impaired platelet/connective tissue reaction in man after aspirin ingestion. Lancet 1967;2:495-7.

3. Preston F, Whipps S, Jackson C, et al. Inhibition of prostacyclin and platelet thromboxane A2 after low dose aspirin. N Engl J Med 1981;304:76-9.

4. Hankey GJ. One year after CAPRIE, IST, and ESPS 2. Cerebrovasc Dis 1998;8(suppl 5):1-7.

5. Buring J, Hennekens C. Prevention of cardiovascular disease: risks and benefits of aspirin. J Gen Intern Med 1990;5(suppl 5):S54-7.

6. Sivenius J, Laakso M, Penttila IM, et al. The European Stroke Prevention Study: results according to sex. Neurology 1991;41:1189-92.

7. Lewis H, Davis J, Archibald D, Steinke W, Smitherman T. Protective effects of aspirin against acute myocardial infarction and death in men with unstable angina. N Engl J Med 1983;309:396-403.

8. Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative overview of randomised trials of anti platelet therapy. Prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke by prolonged antiplatelet therapy in various categories of patients. BMJ 1994;308:81-106.

9. Sanmuganathan PS, Ghahramani P, Jackson PR, Wallis EJ, Ramsay LE. Aspirin for primary prevention of coronary heart disease: safety and absolute benefit related to coronary risk derived from metaanalysis of randomised trials. Heart 2001;85:265-71.

10. The Salt Collaborative Group. Swedish Aspirin Low dose Trial (SALT) of 75 mg aspirin as secondary prophylaxis after cerebrovascular ischemic events. Lancet 1991;338:1345-9.

11. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. Lancet 1998;351:1755-62.

12. The Medical Research Council’s General Practice Research Framework. Thrombosis prevention trial: randomised trial of low intensity oral anticoagulation with warfarin and low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of ischaemic heart disease in men at increased risk. Lancet 1998;351:233-41.

13. Gum PA, Thamilarasan M, Watanabe J, Blackstone EH, Lauer MS. Aspirin use and all-cause mortality among patients being evaluated for known or suspected coronary artery disease. JAMA 2001;286:1187-94.

14. Havranek EP. Primary Prevention of CHD: nine ways to reduce risk. Am Fam Phys 1999;59:1455-63-1466.

15. National Cholesterol Education Program. Third Report on the Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (ATP III). Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2001. NIH Publication 01-3305.

16. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disordersn, Clinical Evidence. London: British Medical Journal; 2001;64-5.

17. Jadad AR, Moore A, Corroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is binding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996;17:1-12.

18. Sutton AJ, Abrams KR, Jones DR, Sheldon TA, Song F. Methods for Meta-Analysis in Medical Research. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2000;42-5,64-72.

19. StatXact 4 for Windows [computer program]. Cambridge, MA: CYTEL Software Corp; 2000.

20. Steering Committee of the Physician’s Health Study Research Study Group. Final report on the aspirin component of the ongoing Physicians’ Health Study. N Engl J Med 1989;321:129-35.

21. Peto R, Gray R, Collins R, et al. Randomized trial of prophylactic daily aspirin in British male doctors. BMJ 1988;296:313-6.

22. Manson J, Stampfer M, Colditz G, et al. A prospective study of aspirin use and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. JAMA 1991;266:521-7.

23. Silagy C, McNeil J, Donnan G, et al. The Pace Pilot Study: 12 month results and implications for future primary prevention trials in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994;42:643-7.

24. Manson J, Buring J, Satterfield S, Hennekens C. Baseline characteristics of participants in the Physicians Health Study: a randomized trial of aspirin and beta carotene in U.S. physicians. Am J Prev Med 1991;7:150-4.

25. Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomized trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ 2002;324:71-86.

26. Thun M, Namboodiri M, Heath C. Aspirin use and reduced risk of fatal colon cancer. N Engl J Med 1991;325:1593-6.

27. Hennekens C, Buring J. Aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cardiol Clin 1994;12:443-50.

28. Hennekens CH, Jonas MA, Buring JE. Antiplatelet therapy and risk of stroke. Ann Epidemiol 1993;3:568-70.

29. Iso H, Hennekens C, Stampfer M, et al. Prospective study of aspirin use and risk of stroke in women. Stroke 1999;30:1764-71.

30. Kronmal RA, Hart R, Manolio T, et al. Aspirin use and incident stroke in the cardiovascular study. Stroke 1998;29:887-94.

31. Paganini-Hill A, Chao A, Ross RK, Henderson B. Aspirin use and chronic diseases: a cohort study of the elderly. BMJ 1989;299:1247-50.

32. Silagy C, McNeil J, Donnan G, et al. Adverse effects of low dose aspirin in a healthy population. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1993;54:84-9.

- Only 3 primary prevention studies of aspirin included low-risk subjects and measured all-cause mortality.

- Two of those studies demonstrated no significant decrease in mortality with low-dose aspirin.

- The Nurses Health Study demonstrated a dose-dependent increase in mortality with aspirin use.

- There is insufficient evidence for or against recommending aspirin to low-risk individuals.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in the United States, and aspirin, a platelet aggregate inhibitor, is often recommended as prophylaxis for cardiovascular disease.1-3Clinical studies have demonstrated the benefit of aspirin use for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease and stroke.1,4-10 In high-risk subjects, aspirin has been proven effective in primary prevention of major cardiovascular events and nonfatal ischemic heart disease.11-13 Sanmuganathan and colleagues recently reported a meta-analysis of 4 randomized trials of aspirin for primary prevention. Although they determined that aspirin treatment is safe if the coronary event rate is at least 1.5% each year and unsafe if the rate is no higher than 0.5% each year, they did not address all-cause mortality, and 2 of the 4 trials did not include low-risk subjects.9

Many physicians and patients are prescribing aspirin with the expectation of reduced mortality in high-risk and low-risk individuals. Media advertisements and health programs may not clearly delineate the population for whom aspirin has clear benefits. A recent review suggested that aspirin is likely to be effective for primary prevention in yet to be defined groups.14 This review seeks to answer 2 questions. First, are there any primary prevention studies using aspirin that included only low-risk subjects? Second, should aspirin be prescribed routinely to persons at low risk for cardiovascular disease to decrease total mortality?

Methods

Search strategy

The MEDLINE database and the Cochrane Library were systematically searched using the terms aspirin or antiplatelet therapy and primary prevention or prevention and primary and mortality. An additional search was made with primary prevention and myocardial infarction or stroke. The Internet was searched (http://www.google.com) by using the same search terms. The studies were limited to human populations. Search results consisted of abstracts, complete reviews, and reference lists from articles. Morbidity associated with aspirin use also was reviewed.

Selection criteria: end points

Only those studies that investigated primary prevention of cardiovascular disease using aspirin, had low-risk subjects, and included a measure of total mortality were part of our analysis. We used the 2001 Adult Treatment Panel III Guidelines and the recent British Medical Journal clinical evidence guidelines on primary prevention of cardiovascular disorders to define the low-risk patient.15,16 Those guidelines classified major risk factors for ischemic vascular disease as hypertension, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high lowdensity lipoprotein cholesterol, family history of premature coronary heart disease, smoking, diabetes, and advancing age (men ≥ 45 years, women ≥ 55 years). We also classified those patients with past cerebrovascular events, myocardial infarction, and angina as high risk. We defined low risk as having no more than 1 of these risk factors.

Every trial was evaluated independently by each author according to the Jadad scale.17 Based on information in the original articles, we recalculated the odds ratios (ORs) for each study. The results of the 2 randomized trails were combined by means of the Mantel-Haenszel method for combining ORs, and StatXact 4 for Windows was used for the analysis.18,19 The data were used to create a forest plot of mortal-ity.19 The decision to combine studies of like type was made a priority.

Results

MEDLINE search results for aspirin and primary prevention yielded 291 articles. Antiplatelet therapy and primary prevention yielded 64 articles. Myocardial infarction or stroke and primary prevention yielded 514 articles. Cross-referencing aspirin, prevention, and mortality yielded 690 articles. The Cochrane Library search of antiplatelet therapy and prevention and primary yielded 17 complete reviews and 6 abstracts of systematic reviews. No additional studies published or unpublished were identified through the Internet.

Five clinical trials and 1 cohort study that evaluated aspirin for primary prevention were identi-fied.11,12,20-23 One of those, a pilot study, was excluded because it did not provide mortality data for the aspirin and placebo groups.23 Two clinical trials, the Hypertension Optimal Treatment Trial and the Thrombosis Prevention Trial, did not include low-risk subjects.11,12 Although no studies were identified that included only low-risk subjects, 3 studies met our inclusion criteria. Characteristics of those 3 studies are reported in Table 1.

The US Physicians Health Study (USPHS) randomized physicians into 4 treatment groups: aspirin plus beta-carotene, aspirin plus placebo, betacarotene plus placebo, and placebo plus placebo.20 Both aspirin groups took 325 mg every other day. The mean age was 53.2 years.24 Fifty percent of the participants were current or past smokers, and 9% had hypertension. Although the rate of myocardial infarction was significantly lower in the aspirin group, there was no reduction in total cardiovascular mortality. The results are reported in Table 2. More side effects were noted in the aspirin group, including gastric ulcers, gastrointestinal bleeding, hemorrhagic stroke, and other bleeding disorders.20 No separate analysis of low-risk subjects’ risk was performed.

In the British Doctors Study (BDS), 66% of patients were randomized to take aspirin once daily and 33% were to avoid aspirin.21 More than half of the subjects were at least 60 years old. Physicians with stroke, myocardial infarction, ulcer disease, or currently taking any aspirin products were excluded. Six percent of the subjects had a history of heart disease other than myocardial infarction, 10% had hypertension, and 75% of participants were currently smoking or had a history of smoking. No significant differences were noted between groups for myocardial infarction or total mortality. By the end of the study, 44% of the aspirin group had discontinued aspirin secondary to side effects, the most common being dyspepsia. Of the control group, 2% per year started using aspirin because they developed risk factors such as vascular disease or for primary prevention. Low-risk individuals were not evaluated separately.

The Nurses Health Study (NHS) was a cohort study of women who were free of diagnosed coronary heart disease, stroke, and cancer at the start of the study. However, 29% of the women smoked and 15% had hypertension.22 The mean age was 46.0 years, and the follow-up was 96.7% of total potential person years. The study respondents were asked how many aspirin tablets they took per week: 0, 1 to 3, 4 to 6, 7 to 14, or 15+. Those who smoked or were overweight were more likely to take aspirin. No separate analysis of low-risk subjects was performed. Mortality from aspirin use was clearly dose dependent. For study participants taking 1 to 6 aspirin tablets each week, mortality was 0.84% (OR, 1.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.26–1.82); for those taking 7 to 14 aspirin tablets, mortality was 0.99% (OR, 1.80; CI, 1.39–2.33); and for those taking 15+ aspirin tablets, mortality was 1.82% (OR, 3.32; CI, 2.62–4.21). Rates of myocardial infarction and stroke also were higher for all groups taking aspirin (see Table 2). When combined, the USPHS and the BDS demonstrated no significant difference in mortality between aspirin and placebo groups, whereas the NHS found increased mortality from aspirin (Figure).

TABLE 1

Characteristics of aspirin studies that included low-risk subjects

| USPHS | BDS | NHS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | Steering Committee20 | Peto et al21 | Manson et al22 |

| Study population | Healthy US physicians | Healthy UK physicians | Healthy US nurses |

| Study type | Randomized controlled trial | Randomized controlled trial | Cohort |

| Subjects in aspirin group | 11,037 | 3429 | 35,048 |

| Subjects in control group | 11,034 | 1710 | 52,630 |

| Treatment | 325 mg aspirin every other day | 500 mg/d aspirin | 1–15 aspirin tablets/wk |

| Comparison | Placebo | No aspirin | None |

| Follow-up time (y) | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| Jadad score | |||

| Randomization† | 1 | 2 | NA* |

| Blinding ‡ | 1 | 0 | NA |

| Withdrawals § | 1 | 0 | NA |

| Total | 3 | 2 | NA |

| Significant difference in mortality | No | No | Yes in favor of no aspirin |

| *The Jadad scale does not apply to cohort studies. | |||

| †Two points maximum. | |||

| ‡Two points maximum. | |||

| §One point maximum. | |||

| BDS, British Doctors Study; NA, not applicable; NHS, Nurses Health Study; USPHS, US Physicians Health Study. | |||

TABLE 2

Rates of myocardial infarction, stroke, total cardiovascular mortality, and total mortality in studies of aspirin vs no aspirin that included low-risk patients

| Study | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | USPHS (5 y) | BDS (6 y) | NHS (6 y) |

| Myocardial infarction | |||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 139 (1.26) | 169 (4.93) | 244 (0.70) |

| No aspirin, n (%) | 239 (2.17) | 88 (5.15) | 157 (0.30) |

| OR (CI) | 0.58 (0.47–0.71) | 0.96 (0.73–1.24) | 2.34 (1.92–2.86)* |

| Stroke | |||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 119 (1.08) | 91 (2.65) | 109 (0.31) |

| No aspirin, n (%) | 98 (0.89) | 39 (2.28) | 89 (0.17) |

| OR (CI) | 1.22 (0.93–1.59) | 1.17 (0.80–1.71) | 1.84 (1.39–2.44)* |

| Total cardiovascular mortality | |||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 81 (0.73) | 148 (4.32) | 68 (0.19) |

| No aspirin, n (%) | 83 (0.75) | 79 (4.62) | 62 (0.12) |

| OR (CI) | 0.98 (0.72–1.33) | 0.93 (0.70–1.23) | 1.65 (1.17–2.33)* |

| Total mortality | |||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 217 (1.97) | 270 (7.87) | 354 (1.01) |

| No aspirin, n (%) | 227 (2.06) | 151 (8.83) | 292 (0.55) |

| OR (CI) | 0.95 (0.79–1.15) | 0.88 (0.72–1.09) | 1.83 (1.57–2.14)* |

| *OR significant at the .05 level. | |||

| BDS, British Doctors Study; CI, 95% confidence interval; n (%), number (percentage) of patients taking or not taking aspirin; NHS, Nurses Health Study; OR, odds ratio; USPHS, US Physicians Health Study. | |||

FIGURE Forest plot of mortality in healthy patients on aspirin

Discussion

To date, there has been no study of aspirin for primary prevention that included a separate analysis of patients who were free of cardiovascular risk factors. Each of the 3 studies that included low-risk subjects grouped them with subjects at higher risk, those known to benefit from aspirin.9,11,12 Even so, none of those studies demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in all-cause mortality. Even when combined, the BDS and the USPHS demonstrated no significant improvement in mortality. Mortality in the BDS was nearly 4 times greater than that in the USPHS. This finding is likely due to the higher baseline rate of smoking and other risk factors in the British doctors. In contrast to the BDS, the USPHS demonstrated significantly decreased rates for fatal and nonfatal myocardial infarction. Our analysis of the NHS associated aspirin with increased mortality, fatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal myocardial infarction at any dose. The nurses on average had lower risk than the doctors, fewer smoked, and they were younger.

Many studies have clearly demonstrated the benefits of aspirin for primary prevention in high-risk subjects.10-12,25 There may be other benefits to taking prophylactic aspirin. In the Cancer Prevention Study II, aspirin use was associated with decreased death rates from colon cancer.26 Unfortunately, that study did not measure all-cause mortality.

There are a number of limitations to this study. There were no strictly low-risk studies of aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular mortality, and there was a paucity of studies that included low-risk subjects. Because the studies analyzed did not include only low-risk subjects, the results may not apply to all low-risk patients. The BDS did not include a placebo and was not blinded. Although not statistically significant, the ORs tended toward a protective effect for aspirin in the 2 randomized trials. The large difference in mortality between those 2 trials remains unexplained. The NHS was the only study to include women, and it was a cohort study, which is subject to selection and reporting biases. Therefore, aspirin users may have been at higher mortality risk due to smoking, obesity, or other illness, thus rendering the association between aspirin and higher mortality meaningless.

Many studies have shown significant side effects of aspirin, including epistaxis, peptic ulcer disease, gastrointestinal bleeds, and hemorrhagic stroke.15,20-22,27-32 In the BDS, 17% more subjects in the aspirin group developed peptic ulcer disease, and 19% stopped treatment during the first year secondary to gastrointestinal complaints.21

In conclusion, there is currently no evidence to recommend for or against the use of aspirin in low-risk individuals to decrease mortality. There may be other reasons to take aspirin prophylactically such as to reduce myocardial infarction or colon cancer. However, these benefits have not been established in a low-risk population. Health care providers should ask all patients whether they are taking aspirin and evaluate the risk-benefit ratio before recommending it.

- Only 3 primary prevention studies of aspirin included low-risk subjects and measured all-cause mortality.

- Two of those studies demonstrated no significant decrease in mortality with low-dose aspirin.

- The Nurses Health Study demonstrated a dose-dependent increase in mortality with aspirin use.

- There is insufficient evidence for or against recommending aspirin to low-risk individuals.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in the United States, and aspirin, a platelet aggregate inhibitor, is often recommended as prophylaxis for cardiovascular disease.1-3Clinical studies have demonstrated the benefit of aspirin use for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease and stroke.1,4-10 In high-risk subjects, aspirin has been proven effective in primary prevention of major cardiovascular events and nonfatal ischemic heart disease.11-13 Sanmuganathan and colleagues recently reported a meta-analysis of 4 randomized trials of aspirin for primary prevention. Although they determined that aspirin treatment is safe if the coronary event rate is at least 1.5% each year and unsafe if the rate is no higher than 0.5% each year, they did not address all-cause mortality, and 2 of the 4 trials did not include low-risk subjects.9

Many physicians and patients are prescribing aspirin with the expectation of reduced mortality in high-risk and low-risk individuals. Media advertisements and health programs may not clearly delineate the population for whom aspirin has clear benefits. A recent review suggested that aspirin is likely to be effective for primary prevention in yet to be defined groups.14 This review seeks to answer 2 questions. First, are there any primary prevention studies using aspirin that included only low-risk subjects? Second, should aspirin be prescribed routinely to persons at low risk for cardiovascular disease to decrease total mortality?

Methods

Search strategy

The MEDLINE database and the Cochrane Library were systematically searched using the terms aspirin or antiplatelet therapy and primary prevention or prevention and primary and mortality. An additional search was made with primary prevention and myocardial infarction or stroke. The Internet was searched (http://www.google.com) by using the same search terms. The studies were limited to human populations. Search results consisted of abstracts, complete reviews, and reference lists from articles. Morbidity associated with aspirin use also was reviewed.

Selection criteria: end points

Only those studies that investigated primary prevention of cardiovascular disease using aspirin, had low-risk subjects, and included a measure of total mortality were part of our analysis. We used the 2001 Adult Treatment Panel III Guidelines and the recent British Medical Journal clinical evidence guidelines on primary prevention of cardiovascular disorders to define the low-risk patient.15,16 Those guidelines classified major risk factors for ischemic vascular disease as hypertension, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high lowdensity lipoprotein cholesterol, family history of premature coronary heart disease, smoking, diabetes, and advancing age (men ≥ 45 years, women ≥ 55 years). We also classified those patients with past cerebrovascular events, myocardial infarction, and angina as high risk. We defined low risk as having no more than 1 of these risk factors.

Every trial was evaluated independently by each author according to the Jadad scale.17 Based on information in the original articles, we recalculated the odds ratios (ORs) for each study. The results of the 2 randomized trails were combined by means of the Mantel-Haenszel method for combining ORs, and StatXact 4 for Windows was used for the analysis.18,19 The data were used to create a forest plot of mortal-ity.19 The decision to combine studies of like type was made a priority.

Results

MEDLINE search results for aspirin and primary prevention yielded 291 articles. Antiplatelet therapy and primary prevention yielded 64 articles. Myocardial infarction or stroke and primary prevention yielded 514 articles. Cross-referencing aspirin, prevention, and mortality yielded 690 articles. The Cochrane Library search of antiplatelet therapy and prevention and primary yielded 17 complete reviews and 6 abstracts of systematic reviews. No additional studies published or unpublished were identified through the Internet.

Five clinical trials and 1 cohort study that evaluated aspirin for primary prevention were identi-fied.11,12,20-23 One of those, a pilot study, was excluded because it did not provide mortality data for the aspirin and placebo groups.23 Two clinical trials, the Hypertension Optimal Treatment Trial and the Thrombosis Prevention Trial, did not include low-risk subjects.11,12 Although no studies were identified that included only low-risk subjects, 3 studies met our inclusion criteria. Characteristics of those 3 studies are reported in Table 1.

The US Physicians Health Study (USPHS) randomized physicians into 4 treatment groups: aspirin plus beta-carotene, aspirin plus placebo, betacarotene plus placebo, and placebo plus placebo.20 Both aspirin groups took 325 mg every other day. The mean age was 53.2 years.24 Fifty percent of the participants were current or past smokers, and 9% had hypertension. Although the rate of myocardial infarction was significantly lower in the aspirin group, there was no reduction in total cardiovascular mortality. The results are reported in Table 2. More side effects were noted in the aspirin group, including gastric ulcers, gastrointestinal bleeding, hemorrhagic stroke, and other bleeding disorders.20 No separate analysis of low-risk subjects’ risk was performed.

In the British Doctors Study (BDS), 66% of patients were randomized to take aspirin once daily and 33% were to avoid aspirin.21 More than half of the subjects were at least 60 years old. Physicians with stroke, myocardial infarction, ulcer disease, or currently taking any aspirin products were excluded. Six percent of the subjects had a history of heart disease other than myocardial infarction, 10% had hypertension, and 75% of participants were currently smoking or had a history of smoking. No significant differences were noted between groups for myocardial infarction or total mortality. By the end of the study, 44% of the aspirin group had discontinued aspirin secondary to side effects, the most common being dyspepsia. Of the control group, 2% per year started using aspirin because they developed risk factors such as vascular disease or for primary prevention. Low-risk individuals were not evaluated separately.

The Nurses Health Study (NHS) was a cohort study of women who were free of diagnosed coronary heart disease, stroke, and cancer at the start of the study. However, 29% of the women smoked and 15% had hypertension.22 The mean age was 46.0 years, and the follow-up was 96.7% of total potential person years. The study respondents were asked how many aspirin tablets they took per week: 0, 1 to 3, 4 to 6, 7 to 14, or 15+. Those who smoked or were overweight were more likely to take aspirin. No separate analysis of low-risk subjects was performed. Mortality from aspirin use was clearly dose dependent. For study participants taking 1 to 6 aspirin tablets each week, mortality was 0.84% (OR, 1.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.26–1.82); for those taking 7 to 14 aspirin tablets, mortality was 0.99% (OR, 1.80; CI, 1.39–2.33); and for those taking 15+ aspirin tablets, mortality was 1.82% (OR, 3.32; CI, 2.62–4.21). Rates of myocardial infarction and stroke also were higher for all groups taking aspirin (see Table 2). When combined, the USPHS and the BDS demonstrated no significant difference in mortality between aspirin and placebo groups, whereas the NHS found increased mortality from aspirin (Figure).

TABLE 1

Characteristics of aspirin studies that included low-risk subjects

| USPHS | BDS | NHS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | Steering Committee20 | Peto et al21 | Manson et al22 |

| Study population | Healthy US physicians | Healthy UK physicians | Healthy US nurses |

| Study type | Randomized controlled trial | Randomized controlled trial | Cohort |

| Subjects in aspirin group | 11,037 | 3429 | 35,048 |

| Subjects in control group | 11,034 | 1710 | 52,630 |

| Treatment | 325 mg aspirin every other day | 500 mg/d aspirin | 1–15 aspirin tablets/wk |

| Comparison | Placebo | No aspirin | None |

| Follow-up time (y) | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| Jadad score | |||

| Randomization† | 1 | 2 | NA* |

| Blinding ‡ | 1 | 0 | NA |

| Withdrawals § | 1 | 0 | NA |

| Total | 3 | 2 | NA |

| Significant difference in mortality | No | No | Yes in favor of no aspirin |

| *The Jadad scale does not apply to cohort studies. | |||

| †Two points maximum. | |||

| ‡Two points maximum. | |||

| §One point maximum. | |||

| BDS, British Doctors Study; NA, not applicable; NHS, Nurses Health Study; USPHS, US Physicians Health Study. | |||

TABLE 2

Rates of myocardial infarction, stroke, total cardiovascular mortality, and total mortality in studies of aspirin vs no aspirin that included low-risk patients

| Study | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | USPHS (5 y) | BDS (6 y) | NHS (6 y) |

| Myocardial infarction | |||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 139 (1.26) | 169 (4.93) | 244 (0.70) |

| No aspirin, n (%) | 239 (2.17) | 88 (5.15) | 157 (0.30) |

| OR (CI) | 0.58 (0.47–0.71) | 0.96 (0.73–1.24) | 2.34 (1.92–2.86)* |

| Stroke | |||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 119 (1.08) | 91 (2.65) | 109 (0.31) |

| No aspirin, n (%) | 98 (0.89) | 39 (2.28) | 89 (0.17) |

| OR (CI) | 1.22 (0.93–1.59) | 1.17 (0.80–1.71) | 1.84 (1.39–2.44)* |

| Total cardiovascular mortality | |||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 81 (0.73) | 148 (4.32) | 68 (0.19) |

| No aspirin, n (%) | 83 (0.75) | 79 (4.62) | 62 (0.12) |

| OR (CI) | 0.98 (0.72–1.33) | 0.93 (0.70–1.23) | 1.65 (1.17–2.33)* |

| Total mortality | |||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 217 (1.97) | 270 (7.87) | 354 (1.01) |

| No aspirin, n (%) | 227 (2.06) | 151 (8.83) | 292 (0.55) |

| OR (CI) | 0.95 (0.79–1.15) | 0.88 (0.72–1.09) | 1.83 (1.57–2.14)* |

| *OR significant at the .05 level. | |||

| BDS, British Doctors Study; CI, 95% confidence interval; n (%), number (percentage) of patients taking or not taking aspirin; NHS, Nurses Health Study; OR, odds ratio; USPHS, US Physicians Health Study. | |||

FIGURE Forest plot of mortality in healthy patients on aspirin

Discussion

To date, there has been no study of aspirin for primary prevention that included a separate analysis of patients who were free of cardiovascular risk factors. Each of the 3 studies that included low-risk subjects grouped them with subjects at higher risk, those known to benefit from aspirin.9,11,12 Even so, none of those studies demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in all-cause mortality. Even when combined, the BDS and the USPHS demonstrated no significant improvement in mortality. Mortality in the BDS was nearly 4 times greater than that in the USPHS. This finding is likely due to the higher baseline rate of smoking and other risk factors in the British doctors. In contrast to the BDS, the USPHS demonstrated significantly decreased rates for fatal and nonfatal myocardial infarction. Our analysis of the NHS associated aspirin with increased mortality, fatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal myocardial infarction at any dose. The nurses on average had lower risk than the doctors, fewer smoked, and they were younger.

Many studies have clearly demonstrated the benefits of aspirin for primary prevention in high-risk subjects.10-12,25 There may be other benefits to taking prophylactic aspirin. In the Cancer Prevention Study II, aspirin use was associated with decreased death rates from colon cancer.26 Unfortunately, that study did not measure all-cause mortality.

There are a number of limitations to this study. There were no strictly low-risk studies of aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular mortality, and there was a paucity of studies that included low-risk subjects. Because the studies analyzed did not include only low-risk subjects, the results may not apply to all low-risk patients. The BDS did not include a placebo and was not blinded. Although not statistically significant, the ORs tended toward a protective effect for aspirin in the 2 randomized trials. The large difference in mortality between those 2 trials remains unexplained. The NHS was the only study to include women, and it was a cohort study, which is subject to selection and reporting biases. Therefore, aspirin users may have been at higher mortality risk due to smoking, obesity, or other illness, thus rendering the association between aspirin and higher mortality meaningless.

Many studies have shown significant side effects of aspirin, including epistaxis, peptic ulcer disease, gastrointestinal bleeds, and hemorrhagic stroke.15,20-22,27-32 In the BDS, 17% more subjects in the aspirin group developed peptic ulcer disease, and 19% stopped treatment during the first year secondary to gastrointestinal complaints.21

In conclusion, there is currently no evidence to recommend for or against the use of aspirin in low-risk individuals to decrease mortality. There may be other reasons to take aspirin prophylactically such as to reduce myocardial infarction or colon cancer. However, these benefits have not been established in a low-risk population. Health care providers should ask all patients whether they are taking aspirin and evaluate the risk-benefit ratio before recommending it.

1. Fuster V, Dyken M, Vokonas P, Hennekens C. Aspirin as a therapeutic agent in cardiovascular disease. Circulation 1993;87:659-75.

2. Weiss H, Aledort L. Impaired platelet/connective tissue reaction in man after aspirin ingestion. Lancet 1967;2:495-7.

3. Preston F, Whipps S, Jackson C, et al. Inhibition of prostacyclin and platelet thromboxane A2 after low dose aspirin. N Engl J Med 1981;304:76-9.

4. Hankey GJ. One year after CAPRIE, IST, and ESPS 2. Cerebrovasc Dis 1998;8(suppl 5):1-7.

5. Buring J, Hennekens C. Prevention of cardiovascular disease: risks and benefits of aspirin. J Gen Intern Med 1990;5(suppl 5):S54-7.

6. Sivenius J, Laakso M, Penttila IM, et al. The European Stroke Prevention Study: results according to sex. Neurology 1991;41:1189-92.

7. Lewis H, Davis J, Archibald D, Steinke W, Smitherman T. Protective effects of aspirin against acute myocardial infarction and death in men with unstable angina. N Engl J Med 1983;309:396-403.

8. Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative overview of randomised trials of anti platelet therapy. Prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke by prolonged antiplatelet therapy in various categories of patients. BMJ 1994;308:81-106.

9. Sanmuganathan PS, Ghahramani P, Jackson PR, Wallis EJ, Ramsay LE. Aspirin for primary prevention of coronary heart disease: safety and absolute benefit related to coronary risk derived from metaanalysis of randomised trials. Heart 2001;85:265-71.

10. The Salt Collaborative Group. Swedish Aspirin Low dose Trial (SALT) of 75 mg aspirin as secondary prophylaxis after cerebrovascular ischemic events. Lancet 1991;338:1345-9.

11. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. Lancet 1998;351:1755-62.

12. The Medical Research Council’s General Practice Research Framework. Thrombosis prevention trial: randomised trial of low intensity oral anticoagulation with warfarin and low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of ischaemic heart disease in men at increased risk. Lancet 1998;351:233-41.

13. Gum PA, Thamilarasan M, Watanabe J, Blackstone EH, Lauer MS. Aspirin use and all-cause mortality among patients being evaluated for known or suspected coronary artery disease. JAMA 2001;286:1187-94.

14. Havranek EP. Primary Prevention of CHD: nine ways to reduce risk. Am Fam Phys 1999;59:1455-63-1466.

15. National Cholesterol Education Program. Third Report on the Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (ATP III). Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2001. NIH Publication 01-3305.

16. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disordersn, Clinical Evidence. London: British Medical Journal; 2001;64-5.

17. Jadad AR, Moore A, Corroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is binding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996;17:1-12.

18. Sutton AJ, Abrams KR, Jones DR, Sheldon TA, Song F. Methods for Meta-Analysis in Medical Research. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2000;42-5,64-72.

19. StatXact 4 for Windows [computer program]. Cambridge, MA: CYTEL Software Corp; 2000.

20. Steering Committee of the Physician’s Health Study Research Study Group. Final report on the aspirin component of the ongoing Physicians’ Health Study. N Engl J Med 1989;321:129-35.

21. Peto R, Gray R, Collins R, et al. Randomized trial of prophylactic daily aspirin in British male doctors. BMJ 1988;296:313-6.

22. Manson J, Stampfer M, Colditz G, et al. A prospective study of aspirin use and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. JAMA 1991;266:521-7.

23. Silagy C, McNeil J, Donnan G, et al. The Pace Pilot Study: 12 month results and implications for future primary prevention trials in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994;42:643-7.

24. Manson J, Buring J, Satterfield S, Hennekens C. Baseline characteristics of participants in the Physicians Health Study: a randomized trial of aspirin and beta carotene in U.S. physicians. Am J Prev Med 1991;7:150-4.

25. Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomized trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ 2002;324:71-86.

26. Thun M, Namboodiri M, Heath C. Aspirin use and reduced risk of fatal colon cancer. N Engl J Med 1991;325:1593-6.

27. Hennekens C, Buring J. Aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cardiol Clin 1994;12:443-50.

28. Hennekens CH, Jonas MA, Buring JE. Antiplatelet therapy and risk of stroke. Ann Epidemiol 1993;3:568-70.

29. Iso H, Hennekens C, Stampfer M, et al. Prospective study of aspirin use and risk of stroke in women. Stroke 1999;30:1764-71.

30. Kronmal RA, Hart R, Manolio T, et al. Aspirin use and incident stroke in the cardiovascular study. Stroke 1998;29:887-94.

31. Paganini-Hill A, Chao A, Ross RK, Henderson B. Aspirin use and chronic diseases: a cohort study of the elderly. BMJ 1989;299:1247-50.

32. Silagy C, McNeil J, Donnan G, et al. Adverse effects of low dose aspirin in a healthy population. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1993;54:84-9.

1. Fuster V, Dyken M, Vokonas P, Hennekens C. Aspirin as a therapeutic agent in cardiovascular disease. Circulation 1993;87:659-75.

2. Weiss H, Aledort L. Impaired platelet/connective tissue reaction in man after aspirin ingestion. Lancet 1967;2:495-7.

3. Preston F, Whipps S, Jackson C, et al. Inhibition of prostacyclin and platelet thromboxane A2 after low dose aspirin. N Engl J Med 1981;304:76-9.

4. Hankey GJ. One year after CAPRIE, IST, and ESPS 2. Cerebrovasc Dis 1998;8(suppl 5):1-7.

5. Buring J, Hennekens C. Prevention of cardiovascular disease: risks and benefits of aspirin. J Gen Intern Med 1990;5(suppl 5):S54-7.

6. Sivenius J, Laakso M, Penttila IM, et al. The European Stroke Prevention Study: results according to sex. Neurology 1991;41:1189-92.

7. Lewis H, Davis J, Archibald D, Steinke W, Smitherman T. Protective effects of aspirin against acute myocardial infarction and death in men with unstable angina. N Engl J Med 1983;309:396-403.

8. Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative overview of randomised trials of anti platelet therapy. Prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke by prolonged antiplatelet therapy in various categories of patients. BMJ 1994;308:81-106.

9. Sanmuganathan PS, Ghahramani P, Jackson PR, Wallis EJ, Ramsay LE. Aspirin for primary prevention of coronary heart disease: safety and absolute benefit related to coronary risk derived from metaanalysis of randomised trials. Heart 2001;85:265-71.

10. The Salt Collaborative Group. Swedish Aspirin Low dose Trial (SALT) of 75 mg aspirin as secondary prophylaxis after cerebrovascular ischemic events. Lancet 1991;338:1345-9.

11. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. Lancet 1998;351:1755-62.

12. The Medical Research Council’s General Practice Research Framework. Thrombosis prevention trial: randomised trial of low intensity oral anticoagulation with warfarin and low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of ischaemic heart disease in men at increased risk. Lancet 1998;351:233-41.