User login

Factors Associated with Radiation Toxicity and Survival in Patients with Presumed Early-Stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Receiving Empiric Stereotactic Ablative Radiotherapy

Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) has become the standard of care for inoperable early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Many patients are unable to undergo a biopsy safely because of poor pulmonary function or underlying emphysema and are then empirically treated with radiotherapy if they meet criteria. In these patients, local control can be achieved with SABR with minimal toxicity.1 Considering that median overall survival (OS) among patients with untreated stage I NSCLC has been reported to be as low as 9 months, early treatment with SABR could lead to increased survival of 29 to 60 months.2-4

The RTOG 0236 trial showed a median OS of 48 months and the randomized phase III CHISEL trial showed a median OS of 60 months; however, these survival data were reported in patients who were able to safely undergo a biopsy and had confirmed NSCLC.4,5 For patients without a diagnosis confirmed by biopsy and who are treated with empiric SABR, patient factors that influence radiation toxicity and OS are not well defined.

It is not clear if empiric radiation benefits survival or if treatment causes decline in lung function, considering that underlying chronic lung disease precludes these patients from biopsy. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the factors associated with radiation toxicity with empiric SABR and to evaluate OS in this population without a biopsy-confirmed diagnosis.

Methods

This was a single center retrospective review of patients treated at the radiation oncology department at the Kansas City Veterans Affairs Medical Center from August 2014 to February 2019. Data were collected on 69 patients with pulmonary nodules identified by chest computed tomography (CT) and/or positron emission tomography (PET)-CT that were highly suspicious for primary NSCLC.

These patients were presented at a multidisciplinary meeting that involved pulmonologists, oncologists, radiation oncologists, and thoracic surgeons. Patients were deemed to be poor candidates for biopsy because of severe underlying emphysema, which would put them at high risk for pneumothorax with a percutaneous needle biopsy, or were unable to tolerate general anesthesia for navigational bronchoscopy or surgical biopsy because of poor lung function. These patients were diagnosed with presumed stage I NSCLC using the criteria: minimum of 2 sequential CT scans with enlarging nodule; absence of metastases on PET-CT; the single nodule had to be fluorodeoxyglucose avid with a minimum standardized uptake value of 2.5, and absence of clinical history or physical examination consistent with small cell lung cancer or infection.

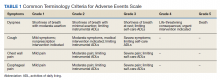

After a consensus was reached that patients met these criteria, individuals were referred for empiric SABR. Follow-up visits were at 1 month, 3 months, and every 6 months. Variables analyzed included: patient demographics, pre- and posttreatment pulmonary function tests (PFT) when available, pre-treatment oxygen use, tumor size and location (peripheral, central, or ultra-central), radiation doses, and grade of toxicity as defined by Human and Health Services Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0 (dyspnea and cough both counted as pulmonary toxicity): acute ≤ 90 days and late > 90 days (Table 1).

SPSS versions 24 and 26 were used for statistical analysis. Median and range were obtained for continuous variables with a normal distribution. Kaplan-Meier log-rank testing was used to analyze OS. χ2 and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to analyze association between independent variables and OS. Analysis of significant findings were repeated with operable patients excluded for further analysis.

Results

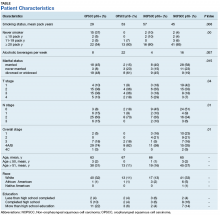

The median follow-up was 18 months (range, 1 to 54). The median age was 71 years (range, 59 to 95) (Table 2). Most patients (97.1%) were male. The majority of patients (79.4%) had a 0 or 1 for the Eastern Cooperative Oncology group performance status, indicating fully active or restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to perform light work. All patients were either current or former smokers with an average pack-year history of 69.4. Only 11.6% of patients had operable disease, but received empiric SABR because they declined surgery. Four patients did not have pretreatment spirometry available and 37 did not have pretreatment diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) data.

Most patients had a pretreatment forced expiratory volume during the first seconds (FEV1) value and DLCO < 60% of predicted (60% and 84% of the patients, respectively). The median tumor diameter was 2 cm. Of the 68.2% of patients who did not have chronic hypoxemic respiratory failure before SABR, 16% developed a new requirement for supplemental oxygen. Sixty-two tumors (89.9%) were peripheral. There were 4 local recurrences (5.7%), 10 regional (different lobe and nodal) failures (14.3%), and 15 distant metastases (21.4%).

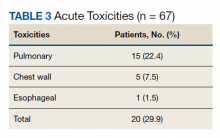

Nineteen of 67 patients (26.3%) had acute toxicity of which 9 had acute grade ≥ 2 toxicity; information regarding toxicity was missing on 2 patients. Thirty-two of 65 (49.9%) patients had late toxicity of which 20 (30.8%) had late grade ≥ 2 toxicity. The main factor associated with development of acute toxicity was pretreatment oxygendependence (P = .047). This was not significant when comparing only inoperable patients. Twenty patients (29.9%) developed some type of acute toxicity; pulmonary toxicity was most common (22.4%) (Table 3). All patients with acute toxicity also developed late toxicity except for 1 who died before 3 months. Predominantly, the deaths in our sample were from causes other than the malignancy or treatment, such as sepsis, deconditioning after a fall, cardiovascular complications, etc. Acute toxicity of grade ≥ 2 was significantly associated with late toxicity (P < .001 for both) in both operable and inoperable patients (P < .001).

Development of any acute toxicity grade ≥ 2 was significantly associated with oxygendependence at baseline (P = .003), central location (P < .001), and new oxygen requirement (P = .02). Only central tumor location was found to be significant (P = .001) within the inoperable cohort. There were no significant differences in outcome based on pulmonary function testing (FEV1, forced vital capacity, or DLCO) or the analyzed PFT subgroups (FEV1 < 1.0 L, FEV1 < 1.5 L, FEV1 < 30%, and FEV1 < 35%).

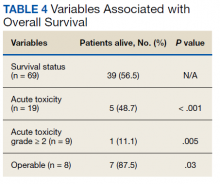

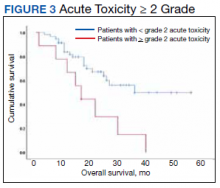

At the time of data collection, 30 patients were deceased (43.5%). There was a statistically significant association between OS and operability (P = .03; Table 4, Figure 1). Decreased OS was significantly associated with acute toxicity (P = .001) and acute toxicity grade ≥ 2 (P = .005; Figures 2 and 3). For the inoperable patients, both acute toxicity (P < .001) and acute toxicity grade ≥ 2 (P = .026) remained significant.

Discussion

SABR is an effective treatment for inoperable early-stage NSCLC, however its therapeutic ratio in a more frail population who cannot withstand biopsy is not well established. Additionally, the prevalence of benign disease in patients with solitary pulmonary nodules can be between 9% and 21%.6 Haidar and colleagues looked at 55 patients who received empiric SABR and found a median OS of 30.2 months with an 8.7% risk of local failure, 13% risk of regional failure with 8.7% acute toxicity, and 13% chronic toxicity.7 Data from Harkenrider and colleagues (n = 34) revealed similar results with a 2-year OS of 85%, local control of 97.1%, and regional control of 80%. The authors noted no grade ≥ 3 acute toxicities and an incidence of grade ≥ 3 late toxicities of 8.8%.1 These findings are concordant with our study results, confirming the safety and efficacy of SABR. Furthermore, a National Cancer Database analysis of observation vs empiric SABR found an OS of 10.1 months and 29 months respectively, with a hazard ratio of 0.64 (P < .001).3 Additionally, Fischer-Valuck and colleagues (n = 88) compared biopsy confirmed vs unbiopsied patients treated with SABR and found no difference in the 3-year local progression-free survival (93.1% vs 94.1%), regional lymph node metastasis and distant metastases free survival (92.5% vs 87.4%), or OS (59.9% vs 58.9%).8 With a median OS of ≤ 1 year for untreated stage I NSCLC,these studies support treating patients with empiric SABR.4

Other researchers have sought parameters to identify patients for whom radiation therapy would be too toxic. Guckenberger and colleagues aimed to establish a lower limit of pretreatment PFT to exclude patients and found only a 7% incidence of grade ≥ 2 adverse effects and toxicity did not increase with lower pulmonary function.9 They concluded that SABR was safe even for patients with poor pulmonary function. Other institutions have confirmed such findings and have been unable to find a cut-off PFT to exclude patients from empiric SABR.10,11 An analysis from the RTOG 0236 trial also noted that poor baseline PFT could not predict pulmonary toxicity or survival. Additionally, the study demonstrated only minimal decreases in patients’ FEV1 (5.8%) and DLCO (6%) at 2 years.12

Our study sought to identify a cut-off on FEV1 or DLCO that could be associated with increased toxicity. We also evaluated the incidence of acute toxicities grade ≥ 2 by stratifying patients according to FEV1 into subgroups: FEV1 < 1.0 L, FEV1 < 1.5 L, FEV1 < 30% of predicted and FEV1 < 35% of predicted. However, similar to other studies, we did not find any value that was significantly associated with increased toxicity that could preclude empiric SABR. One possible reason is that no treatment is offered for patients with extremely poor lung function as deemed by clinical judgement, therefore data on these patients is unavailable. In contradiction to other studies, our study found that oxygen dependence before treatment was significantly associated with development of acute toxicities. The exact mechanism for this association is unknown and could not be elucidated by baseline PFT. One possible explanation is that SABR could lead to oxygen free radical generation. In addition, our study indicated that those who developed acute toxicities had worse OS.

Limitations

Our study is limited by caveats of a retrospective study and its small sample size, but is in line with the reported literature (ranging from 33 to 88 patients).1,7,8 Another limitation is that data on pretreatment DLCO was missing in 37 patients and the lack of statistical robustness in terms of the smaller inoperable cohort, which limits the analyses of these factors in regards to anticipated morbidity from SABR. Also, given this is data collected from the US Department of Veterans Affairs, only 3% of our sample was female.

Conclusions

Empiric SABR for patients with presumed early-stage NSCLC appears to be safe and might positively impact OS. Development of any acute toxicity grade ≥ 2 was significantly associated with dependence on supplemental oxygen before treatment, central tumor location, and development of new oxygen requirement. No association was found in patients with poor pulmonary function before treatment because we could not find a FEV1 or DLCO cutoff that could preclude patients from empiric SABR. Considering the poor survival of untreated early-stage NSCLC, coupled with the efficacy and safety of empiric SABR for those with presumed disease, definitive SABR should be offered selectively within this patient population.

Acknowledgments

Drs. Park, Whiting and Castillo contributed to data collection. Drs. Park, Govindan and Castillo contributed to the statistical analysis and writing the first draft and final manuscript. Drs. Park, Govindan, Huang, and Reddy contributed to the discussion section.

1. Harkenrider MM, Bertke MH, Dunlap NE. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for unbiopsied early-stage lung cancer: a multi-institutional analysis. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;37(4):337-342. doi:10.1097/COC.0b013e318277d822

2. Raz DJ, Zell JA, Ou SH, Gandara DR, Anton-Culver H, Jablons DM. Natural history of stage I non-small cell lung cancer: implications for early detection. Chest. 2007;132(1):193-199. doi:10.1378/chest.06-3096

3. Nanda RH, Liu Y, Gillespie TW, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy versus no treatment for early stage non-small cell lung cancer in medically inoperable elderly patients: a National Cancer Data Base analysis. Cancer. 2015;121(23):4222-4230. doi:10.1002/cncr.29640

4. Ball D, Mai GT, Vinod S, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy versus standard radiotherapy in stage 1 non-small-cell lung cancer (TROG 09.02 CHISEL): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(4):494-503. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30896-9

5. Timmerman R, Paulus R, Galvin J, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for inoperable early stage lung cancer. JAMA. 2010;303(11):1070-1076. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.261

6. Smith MA, Battafarano RJ, Meyers BF, Zoole JB, Cooper JD, Patterson GA. Prevalence of benign disease in patients undergoing resection for suspected lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81(5):1824-1828. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.11.010

7. Haidar YM, Rahn DA 3rd, Nath S, et al. Comparison of outcomes following stereotactic body radiotherapy for nonsmall cell lung cancer in patients with and without pathological confirmation. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2014;8(1):3-12. doi:10.1177/1753465813512545

8. Fischer-Valuck BW, Boggs H, Katz S, Durci M, Acharya S, Rosen LR. Comparison of stereotactic body radiation therapy for biopsy-proven versus radiographically diagnosed early-stage non-small lung cancer: a single-institution experience. Tumori. 2015;101(3):287-293. doi:10.5301/tj.5000279

9. Guckenberger M, Kestin LL, Hope AJ, et al. Is there a lower limit of pretreatment pulmonary function for safe and effective stereotactic body radiotherapy for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer? J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:542-551. doi:10.1097/JTO.0b013e31824165d7

10. Wang J, Cao J, Yuan S, et al. Poor baseline pulmonary function may not increase the risk of radiation-induced lung toxicity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85(3):798-804. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.06.040

11. Henderson M, McGarry R, Yiannoutsos C, et al. Baseline pulmonary function as a predictor for survival and decline in pulmonary function over time in patients undergoing stereotactic body radiotherapy for the treatment of stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72(2):404-409. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.12.051

12. Stanic S, Paulus R, Timmerman RD, et al. No clinically significant changes in pulmonary function following stereotactic body radiation therapy for early- stage peripheral non-small cell lung cancer: an analysis of RTOG 0236. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88(5):1092-1099. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.12.050

Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) has become the standard of care for inoperable early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Many patients are unable to undergo a biopsy safely because of poor pulmonary function or underlying emphysema and are then empirically treated with radiotherapy if they meet criteria. In these patients, local control can be achieved with SABR with minimal toxicity.1 Considering that median overall survival (OS) among patients with untreated stage I NSCLC has been reported to be as low as 9 months, early treatment with SABR could lead to increased survival of 29 to 60 months.2-4

The RTOG 0236 trial showed a median OS of 48 months and the randomized phase III CHISEL trial showed a median OS of 60 months; however, these survival data were reported in patients who were able to safely undergo a biopsy and had confirmed NSCLC.4,5 For patients without a diagnosis confirmed by biopsy and who are treated with empiric SABR, patient factors that influence radiation toxicity and OS are not well defined.

It is not clear if empiric radiation benefits survival or if treatment causes decline in lung function, considering that underlying chronic lung disease precludes these patients from biopsy. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the factors associated with radiation toxicity with empiric SABR and to evaluate OS in this population without a biopsy-confirmed diagnosis.

Methods

This was a single center retrospective review of patients treated at the radiation oncology department at the Kansas City Veterans Affairs Medical Center from August 2014 to February 2019. Data were collected on 69 patients with pulmonary nodules identified by chest computed tomography (CT) and/or positron emission tomography (PET)-CT that were highly suspicious for primary NSCLC.

These patients were presented at a multidisciplinary meeting that involved pulmonologists, oncologists, radiation oncologists, and thoracic surgeons. Patients were deemed to be poor candidates for biopsy because of severe underlying emphysema, which would put them at high risk for pneumothorax with a percutaneous needle biopsy, or were unable to tolerate general anesthesia for navigational bronchoscopy or surgical biopsy because of poor lung function. These patients were diagnosed with presumed stage I NSCLC using the criteria: minimum of 2 sequential CT scans with enlarging nodule; absence of metastases on PET-CT; the single nodule had to be fluorodeoxyglucose avid with a minimum standardized uptake value of 2.5, and absence of clinical history or physical examination consistent with small cell lung cancer or infection.

After a consensus was reached that patients met these criteria, individuals were referred for empiric SABR. Follow-up visits were at 1 month, 3 months, and every 6 months. Variables analyzed included: patient demographics, pre- and posttreatment pulmonary function tests (PFT) when available, pre-treatment oxygen use, tumor size and location (peripheral, central, or ultra-central), radiation doses, and grade of toxicity as defined by Human and Health Services Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0 (dyspnea and cough both counted as pulmonary toxicity): acute ≤ 90 days and late > 90 days (Table 1).

SPSS versions 24 and 26 were used for statistical analysis. Median and range were obtained for continuous variables with a normal distribution. Kaplan-Meier log-rank testing was used to analyze OS. χ2 and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to analyze association between independent variables and OS. Analysis of significant findings were repeated with operable patients excluded for further analysis.

Results

The median follow-up was 18 months (range, 1 to 54). The median age was 71 years (range, 59 to 95) (Table 2). Most patients (97.1%) were male. The majority of patients (79.4%) had a 0 or 1 for the Eastern Cooperative Oncology group performance status, indicating fully active or restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to perform light work. All patients were either current or former smokers with an average pack-year history of 69.4. Only 11.6% of patients had operable disease, but received empiric SABR because they declined surgery. Four patients did not have pretreatment spirometry available and 37 did not have pretreatment diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) data.

Most patients had a pretreatment forced expiratory volume during the first seconds (FEV1) value and DLCO < 60% of predicted (60% and 84% of the patients, respectively). The median tumor diameter was 2 cm. Of the 68.2% of patients who did not have chronic hypoxemic respiratory failure before SABR, 16% developed a new requirement for supplemental oxygen. Sixty-two tumors (89.9%) were peripheral. There were 4 local recurrences (5.7%), 10 regional (different lobe and nodal) failures (14.3%), and 15 distant metastases (21.4%).

Nineteen of 67 patients (26.3%) had acute toxicity of which 9 had acute grade ≥ 2 toxicity; information regarding toxicity was missing on 2 patients. Thirty-two of 65 (49.9%) patients had late toxicity of which 20 (30.8%) had late grade ≥ 2 toxicity. The main factor associated with development of acute toxicity was pretreatment oxygendependence (P = .047). This was not significant when comparing only inoperable patients. Twenty patients (29.9%) developed some type of acute toxicity; pulmonary toxicity was most common (22.4%) (Table 3). All patients with acute toxicity also developed late toxicity except for 1 who died before 3 months. Predominantly, the deaths in our sample were from causes other than the malignancy or treatment, such as sepsis, deconditioning after a fall, cardiovascular complications, etc. Acute toxicity of grade ≥ 2 was significantly associated with late toxicity (P < .001 for both) in both operable and inoperable patients (P < .001).

Development of any acute toxicity grade ≥ 2 was significantly associated with oxygendependence at baseline (P = .003), central location (P < .001), and new oxygen requirement (P = .02). Only central tumor location was found to be significant (P = .001) within the inoperable cohort. There were no significant differences in outcome based on pulmonary function testing (FEV1, forced vital capacity, or DLCO) or the analyzed PFT subgroups (FEV1 < 1.0 L, FEV1 < 1.5 L, FEV1 < 30%, and FEV1 < 35%).

At the time of data collection, 30 patients were deceased (43.5%). There was a statistically significant association between OS and operability (P = .03; Table 4, Figure 1). Decreased OS was significantly associated with acute toxicity (P = .001) and acute toxicity grade ≥ 2 (P = .005; Figures 2 and 3). For the inoperable patients, both acute toxicity (P < .001) and acute toxicity grade ≥ 2 (P = .026) remained significant.

Discussion

SABR is an effective treatment for inoperable early-stage NSCLC, however its therapeutic ratio in a more frail population who cannot withstand biopsy is not well established. Additionally, the prevalence of benign disease in patients with solitary pulmonary nodules can be between 9% and 21%.6 Haidar and colleagues looked at 55 patients who received empiric SABR and found a median OS of 30.2 months with an 8.7% risk of local failure, 13% risk of regional failure with 8.7% acute toxicity, and 13% chronic toxicity.7 Data from Harkenrider and colleagues (n = 34) revealed similar results with a 2-year OS of 85%, local control of 97.1%, and regional control of 80%. The authors noted no grade ≥ 3 acute toxicities and an incidence of grade ≥ 3 late toxicities of 8.8%.1 These findings are concordant with our study results, confirming the safety and efficacy of SABR. Furthermore, a National Cancer Database analysis of observation vs empiric SABR found an OS of 10.1 months and 29 months respectively, with a hazard ratio of 0.64 (P < .001).3 Additionally, Fischer-Valuck and colleagues (n = 88) compared biopsy confirmed vs unbiopsied patients treated with SABR and found no difference in the 3-year local progression-free survival (93.1% vs 94.1%), regional lymph node metastasis and distant metastases free survival (92.5% vs 87.4%), or OS (59.9% vs 58.9%).8 With a median OS of ≤ 1 year for untreated stage I NSCLC,these studies support treating patients with empiric SABR.4

Other researchers have sought parameters to identify patients for whom radiation therapy would be too toxic. Guckenberger and colleagues aimed to establish a lower limit of pretreatment PFT to exclude patients and found only a 7% incidence of grade ≥ 2 adverse effects and toxicity did not increase with lower pulmonary function.9 They concluded that SABR was safe even for patients with poor pulmonary function. Other institutions have confirmed such findings and have been unable to find a cut-off PFT to exclude patients from empiric SABR.10,11 An analysis from the RTOG 0236 trial also noted that poor baseline PFT could not predict pulmonary toxicity or survival. Additionally, the study demonstrated only minimal decreases in patients’ FEV1 (5.8%) and DLCO (6%) at 2 years.12

Our study sought to identify a cut-off on FEV1 or DLCO that could be associated with increased toxicity. We also evaluated the incidence of acute toxicities grade ≥ 2 by stratifying patients according to FEV1 into subgroups: FEV1 < 1.0 L, FEV1 < 1.5 L, FEV1 < 30% of predicted and FEV1 < 35% of predicted. However, similar to other studies, we did not find any value that was significantly associated with increased toxicity that could preclude empiric SABR. One possible reason is that no treatment is offered for patients with extremely poor lung function as deemed by clinical judgement, therefore data on these patients is unavailable. In contradiction to other studies, our study found that oxygen dependence before treatment was significantly associated with development of acute toxicities. The exact mechanism for this association is unknown and could not be elucidated by baseline PFT. One possible explanation is that SABR could lead to oxygen free radical generation. In addition, our study indicated that those who developed acute toxicities had worse OS.

Limitations

Our study is limited by caveats of a retrospective study and its small sample size, but is in line with the reported literature (ranging from 33 to 88 patients).1,7,8 Another limitation is that data on pretreatment DLCO was missing in 37 patients and the lack of statistical robustness in terms of the smaller inoperable cohort, which limits the analyses of these factors in regards to anticipated morbidity from SABR. Also, given this is data collected from the US Department of Veterans Affairs, only 3% of our sample was female.

Conclusions

Empiric SABR for patients with presumed early-stage NSCLC appears to be safe and might positively impact OS. Development of any acute toxicity grade ≥ 2 was significantly associated with dependence on supplemental oxygen before treatment, central tumor location, and development of new oxygen requirement. No association was found in patients with poor pulmonary function before treatment because we could not find a FEV1 or DLCO cutoff that could preclude patients from empiric SABR. Considering the poor survival of untreated early-stage NSCLC, coupled with the efficacy and safety of empiric SABR for those with presumed disease, definitive SABR should be offered selectively within this patient population.

Acknowledgments

Drs. Park, Whiting and Castillo contributed to data collection. Drs. Park, Govindan and Castillo contributed to the statistical analysis and writing the first draft and final manuscript. Drs. Park, Govindan, Huang, and Reddy contributed to the discussion section.

Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) has become the standard of care for inoperable early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Many patients are unable to undergo a biopsy safely because of poor pulmonary function or underlying emphysema and are then empirically treated with radiotherapy if they meet criteria. In these patients, local control can be achieved with SABR with minimal toxicity.1 Considering that median overall survival (OS) among patients with untreated stage I NSCLC has been reported to be as low as 9 months, early treatment with SABR could lead to increased survival of 29 to 60 months.2-4

The RTOG 0236 trial showed a median OS of 48 months and the randomized phase III CHISEL trial showed a median OS of 60 months; however, these survival data were reported in patients who were able to safely undergo a biopsy and had confirmed NSCLC.4,5 For patients without a diagnosis confirmed by biopsy and who are treated with empiric SABR, patient factors that influence radiation toxicity and OS are not well defined.

It is not clear if empiric radiation benefits survival or if treatment causes decline in lung function, considering that underlying chronic lung disease precludes these patients from biopsy. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the factors associated with radiation toxicity with empiric SABR and to evaluate OS in this population without a biopsy-confirmed diagnosis.

Methods

This was a single center retrospective review of patients treated at the radiation oncology department at the Kansas City Veterans Affairs Medical Center from August 2014 to February 2019. Data were collected on 69 patients with pulmonary nodules identified by chest computed tomography (CT) and/or positron emission tomography (PET)-CT that were highly suspicious for primary NSCLC.

These patients were presented at a multidisciplinary meeting that involved pulmonologists, oncologists, radiation oncologists, and thoracic surgeons. Patients were deemed to be poor candidates for biopsy because of severe underlying emphysema, which would put them at high risk for pneumothorax with a percutaneous needle biopsy, or were unable to tolerate general anesthesia for navigational bronchoscopy or surgical biopsy because of poor lung function. These patients were diagnosed with presumed stage I NSCLC using the criteria: minimum of 2 sequential CT scans with enlarging nodule; absence of metastases on PET-CT; the single nodule had to be fluorodeoxyglucose avid with a minimum standardized uptake value of 2.5, and absence of clinical history or physical examination consistent with small cell lung cancer or infection.

After a consensus was reached that patients met these criteria, individuals were referred for empiric SABR. Follow-up visits were at 1 month, 3 months, and every 6 months. Variables analyzed included: patient demographics, pre- and posttreatment pulmonary function tests (PFT) when available, pre-treatment oxygen use, tumor size and location (peripheral, central, or ultra-central), radiation doses, and grade of toxicity as defined by Human and Health Services Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0 (dyspnea and cough both counted as pulmonary toxicity): acute ≤ 90 days and late > 90 days (Table 1).

SPSS versions 24 and 26 were used for statistical analysis. Median and range were obtained for continuous variables with a normal distribution. Kaplan-Meier log-rank testing was used to analyze OS. χ2 and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to analyze association between independent variables and OS. Analysis of significant findings were repeated with operable patients excluded for further analysis.

Results

The median follow-up was 18 months (range, 1 to 54). The median age was 71 years (range, 59 to 95) (Table 2). Most patients (97.1%) were male. The majority of patients (79.4%) had a 0 or 1 for the Eastern Cooperative Oncology group performance status, indicating fully active or restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to perform light work. All patients were either current or former smokers with an average pack-year history of 69.4. Only 11.6% of patients had operable disease, but received empiric SABR because they declined surgery. Four patients did not have pretreatment spirometry available and 37 did not have pretreatment diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) data.

Most patients had a pretreatment forced expiratory volume during the first seconds (FEV1) value and DLCO < 60% of predicted (60% and 84% of the patients, respectively). The median tumor diameter was 2 cm. Of the 68.2% of patients who did not have chronic hypoxemic respiratory failure before SABR, 16% developed a new requirement for supplemental oxygen. Sixty-two tumors (89.9%) were peripheral. There were 4 local recurrences (5.7%), 10 regional (different lobe and nodal) failures (14.3%), and 15 distant metastases (21.4%).

Nineteen of 67 patients (26.3%) had acute toxicity of which 9 had acute grade ≥ 2 toxicity; information regarding toxicity was missing on 2 patients. Thirty-two of 65 (49.9%) patients had late toxicity of which 20 (30.8%) had late grade ≥ 2 toxicity. The main factor associated with development of acute toxicity was pretreatment oxygendependence (P = .047). This was not significant when comparing only inoperable patients. Twenty patients (29.9%) developed some type of acute toxicity; pulmonary toxicity was most common (22.4%) (Table 3). All patients with acute toxicity also developed late toxicity except for 1 who died before 3 months. Predominantly, the deaths in our sample were from causes other than the malignancy or treatment, such as sepsis, deconditioning after a fall, cardiovascular complications, etc. Acute toxicity of grade ≥ 2 was significantly associated with late toxicity (P < .001 for both) in both operable and inoperable patients (P < .001).

Development of any acute toxicity grade ≥ 2 was significantly associated with oxygendependence at baseline (P = .003), central location (P < .001), and new oxygen requirement (P = .02). Only central tumor location was found to be significant (P = .001) within the inoperable cohort. There were no significant differences in outcome based on pulmonary function testing (FEV1, forced vital capacity, or DLCO) or the analyzed PFT subgroups (FEV1 < 1.0 L, FEV1 < 1.5 L, FEV1 < 30%, and FEV1 < 35%).

At the time of data collection, 30 patients were deceased (43.5%). There was a statistically significant association between OS and operability (P = .03; Table 4, Figure 1). Decreased OS was significantly associated with acute toxicity (P = .001) and acute toxicity grade ≥ 2 (P = .005; Figures 2 and 3). For the inoperable patients, both acute toxicity (P < .001) and acute toxicity grade ≥ 2 (P = .026) remained significant.

Discussion

SABR is an effective treatment for inoperable early-stage NSCLC, however its therapeutic ratio in a more frail population who cannot withstand biopsy is not well established. Additionally, the prevalence of benign disease in patients with solitary pulmonary nodules can be between 9% and 21%.6 Haidar and colleagues looked at 55 patients who received empiric SABR and found a median OS of 30.2 months with an 8.7% risk of local failure, 13% risk of regional failure with 8.7% acute toxicity, and 13% chronic toxicity.7 Data from Harkenrider and colleagues (n = 34) revealed similar results with a 2-year OS of 85%, local control of 97.1%, and regional control of 80%. The authors noted no grade ≥ 3 acute toxicities and an incidence of grade ≥ 3 late toxicities of 8.8%.1 These findings are concordant with our study results, confirming the safety and efficacy of SABR. Furthermore, a National Cancer Database analysis of observation vs empiric SABR found an OS of 10.1 months and 29 months respectively, with a hazard ratio of 0.64 (P < .001).3 Additionally, Fischer-Valuck and colleagues (n = 88) compared biopsy confirmed vs unbiopsied patients treated with SABR and found no difference in the 3-year local progression-free survival (93.1% vs 94.1%), regional lymph node metastasis and distant metastases free survival (92.5% vs 87.4%), or OS (59.9% vs 58.9%).8 With a median OS of ≤ 1 year for untreated stage I NSCLC,these studies support treating patients with empiric SABR.4

Other researchers have sought parameters to identify patients for whom radiation therapy would be too toxic. Guckenberger and colleagues aimed to establish a lower limit of pretreatment PFT to exclude patients and found only a 7% incidence of grade ≥ 2 adverse effects and toxicity did not increase with lower pulmonary function.9 They concluded that SABR was safe even for patients with poor pulmonary function. Other institutions have confirmed such findings and have been unable to find a cut-off PFT to exclude patients from empiric SABR.10,11 An analysis from the RTOG 0236 trial also noted that poor baseline PFT could not predict pulmonary toxicity or survival. Additionally, the study demonstrated only minimal decreases in patients’ FEV1 (5.8%) and DLCO (6%) at 2 years.12

Our study sought to identify a cut-off on FEV1 or DLCO that could be associated with increased toxicity. We also evaluated the incidence of acute toxicities grade ≥ 2 by stratifying patients according to FEV1 into subgroups: FEV1 < 1.0 L, FEV1 < 1.5 L, FEV1 < 30% of predicted and FEV1 < 35% of predicted. However, similar to other studies, we did not find any value that was significantly associated with increased toxicity that could preclude empiric SABR. One possible reason is that no treatment is offered for patients with extremely poor lung function as deemed by clinical judgement, therefore data on these patients is unavailable. In contradiction to other studies, our study found that oxygen dependence before treatment was significantly associated with development of acute toxicities. The exact mechanism for this association is unknown and could not be elucidated by baseline PFT. One possible explanation is that SABR could lead to oxygen free radical generation. In addition, our study indicated that those who developed acute toxicities had worse OS.

Limitations

Our study is limited by caveats of a retrospective study and its small sample size, but is in line with the reported literature (ranging from 33 to 88 patients).1,7,8 Another limitation is that data on pretreatment DLCO was missing in 37 patients and the lack of statistical robustness in terms of the smaller inoperable cohort, which limits the analyses of these factors in regards to anticipated morbidity from SABR. Also, given this is data collected from the US Department of Veterans Affairs, only 3% of our sample was female.

Conclusions

Empiric SABR for patients with presumed early-stage NSCLC appears to be safe and might positively impact OS. Development of any acute toxicity grade ≥ 2 was significantly associated with dependence on supplemental oxygen before treatment, central tumor location, and development of new oxygen requirement. No association was found in patients with poor pulmonary function before treatment because we could not find a FEV1 or DLCO cutoff that could preclude patients from empiric SABR. Considering the poor survival of untreated early-stage NSCLC, coupled with the efficacy and safety of empiric SABR for those with presumed disease, definitive SABR should be offered selectively within this patient population.

Acknowledgments

Drs. Park, Whiting and Castillo contributed to data collection. Drs. Park, Govindan and Castillo contributed to the statistical analysis and writing the first draft and final manuscript. Drs. Park, Govindan, Huang, and Reddy contributed to the discussion section.

1. Harkenrider MM, Bertke MH, Dunlap NE. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for unbiopsied early-stage lung cancer: a multi-institutional analysis. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;37(4):337-342. doi:10.1097/COC.0b013e318277d822

2. Raz DJ, Zell JA, Ou SH, Gandara DR, Anton-Culver H, Jablons DM. Natural history of stage I non-small cell lung cancer: implications for early detection. Chest. 2007;132(1):193-199. doi:10.1378/chest.06-3096

3. Nanda RH, Liu Y, Gillespie TW, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy versus no treatment for early stage non-small cell lung cancer in medically inoperable elderly patients: a National Cancer Data Base analysis. Cancer. 2015;121(23):4222-4230. doi:10.1002/cncr.29640

4. Ball D, Mai GT, Vinod S, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy versus standard radiotherapy in stage 1 non-small-cell lung cancer (TROG 09.02 CHISEL): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(4):494-503. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30896-9

5. Timmerman R, Paulus R, Galvin J, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for inoperable early stage lung cancer. JAMA. 2010;303(11):1070-1076. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.261

6. Smith MA, Battafarano RJ, Meyers BF, Zoole JB, Cooper JD, Patterson GA. Prevalence of benign disease in patients undergoing resection for suspected lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81(5):1824-1828. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.11.010

7. Haidar YM, Rahn DA 3rd, Nath S, et al. Comparison of outcomes following stereotactic body radiotherapy for nonsmall cell lung cancer in patients with and without pathological confirmation. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2014;8(1):3-12. doi:10.1177/1753465813512545

8. Fischer-Valuck BW, Boggs H, Katz S, Durci M, Acharya S, Rosen LR. Comparison of stereotactic body radiation therapy for biopsy-proven versus radiographically diagnosed early-stage non-small lung cancer: a single-institution experience. Tumori. 2015;101(3):287-293. doi:10.5301/tj.5000279

9. Guckenberger M, Kestin LL, Hope AJ, et al. Is there a lower limit of pretreatment pulmonary function for safe and effective stereotactic body radiotherapy for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer? J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:542-551. doi:10.1097/JTO.0b013e31824165d7

10. Wang J, Cao J, Yuan S, et al. Poor baseline pulmonary function may not increase the risk of radiation-induced lung toxicity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85(3):798-804. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.06.040

11. Henderson M, McGarry R, Yiannoutsos C, et al. Baseline pulmonary function as a predictor for survival and decline in pulmonary function over time in patients undergoing stereotactic body radiotherapy for the treatment of stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72(2):404-409. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.12.051

12. Stanic S, Paulus R, Timmerman RD, et al. No clinically significant changes in pulmonary function following stereotactic body radiation therapy for early- stage peripheral non-small cell lung cancer: an analysis of RTOG 0236. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88(5):1092-1099. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.12.050

1. Harkenrider MM, Bertke MH, Dunlap NE. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for unbiopsied early-stage lung cancer: a multi-institutional analysis. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;37(4):337-342. doi:10.1097/COC.0b013e318277d822

2. Raz DJ, Zell JA, Ou SH, Gandara DR, Anton-Culver H, Jablons DM. Natural history of stage I non-small cell lung cancer: implications for early detection. Chest. 2007;132(1):193-199. doi:10.1378/chest.06-3096

3. Nanda RH, Liu Y, Gillespie TW, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy versus no treatment for early stage non-small cell lung cancer in medically inoperable elderly patients: a National Cancer Data Base analysis. Cancer. 2015;121(23):4222-4230. doi:10.1002/cncr.29640

4. Ball D, Mai GT, Vinod S, et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy versus standard radiotherapy in stage 1 non-small-cell lung cancer (TROG 09.02 CHISEL): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(4):494-503. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30896-9

5. Timmerman R, Paulus R, Galvin J, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for inoperable early stage lung cancer. JAMA. 2010;303(11):1070-1076. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.261

6. Smith MA, Battafarano RJ, Meyers BF, Zoole JB, Cooper JD, Patterson GA. Prevalence of benign disease in patients undergoing resection for suspected lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81(5):1824-1828. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.11.010

7. Haidar YM, Rahn DA 3rd, Nath S, et al. Comparison of outcomes following stereotactic body radiotherapy for nonsmall cell lung cancer in patients with and without pathological confirmation. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2014;8(1):3-12. doi:10.1177/1753465813512545

8. Fischer-Valuck BW, Boggs H, Katz S, Durci M, Acharya S, Rosen LR. Comparison of stereotactic body radiation therapy for biopsy-proven versus radiographically diagnosed early-stage non-small lung cancer: a single-institution experience. Tumori. 2015;101(3):287-293. doi:10.5301/tj.5000279

9. Guckenberger M, Kestin LL, Hope AJ, et al. Is there a lower limit of pretreatment pulmonary function for safe and effective stereotactic body radiotherapy for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer? J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:542-551. doi:10.1097/JTO.0b013e31824165d7

10. Wang J, Cao J, Yuan S, et al. Poor baseline pulmonary function may not increase the risk of radiation-induced lung toxicity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85(3):798-804. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.06.040

11. Henderson M, McGarry R, Yiannoutsos C, et al. Baseline pulmonary function as a predictor for survival and decline in pulmonary function over time in patients undergoing stereotactic body radiotherapy for the treatment of stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72(2):404-409. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.12.051

12. Stanic S, Paulus R, Timmerman RD, et al. No clinically significant changes in pulmonary function following stereotactic body radiation therapy for early- stage peripheral non-small cell lung cancer: an analysis of RTOG 0236. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88(5):1092-1099. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.12.050

VA-Radiation Oncology Quality Surveillance Program: Enhancing Quality Measure Data Capture, Measuring Quality Benchmarks and Ensuring Long Term Sustainability of Quality Improvements in Community Care

INTRODUCTION: Delivery of high-quality cancer care improves oncologic outcomes, including survival and quality of life. The VA National Radiation Oncology (NROP) established the VA Radiation Oncology Quality Surveillance Program (VAROQS) which has developed clinical quality measures (QM) as a measure of quality indices in radiation oncology. We sought to measure quality in community care, assess barriers to data capture, and develop solutions to ensure long term sustainability of continuous quality improvement for veterans that receive dual care, both within the VA and in non-VA community care (NVCC).

METHODS: From 2016-2018, the VA-ROQS project randomly selected three Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) for quality analysis using established QM for prostate cancer, specifically, 6, 16, and 22. NROP manually abstracted data for QM treated in NVCC QMs, which was compared to the performance of the VA QM in the same VISN as well as for all VISNs in the VA.

RESULTS: Out of the 723 NVCC cases that were examined, none were fully evaluable for all 25 Prostate quality metrics. QM was able to be assessed in only 28% of NVCC patients (n=208) reviewed. Only 12/25 (48%) of all Prostate QM were able to be compared between VA and NVCC. Out of the 12 available Prostate QM, 9 were performance, 2 were surveillance, while 1 was an aspirational measure. The overall > 75% pass rate of all the expected performance QM measures for the VA was 13/14 (92%). For NVCC, of the available expected QM for comparison, 8 of which were high potential impact, only 1/9 (11%) QM received a >75% pass rate in all three NVCC VISNs. When examining the 8 high potential impact QM, the VA had a 100% pass rate.

CONCLUSIONS: There are challenges to obtaining data to perform QM assessment from community care. For cases where QM performance could be assessed, VA care outperformed non-VA care. VA-ROQS program is an ongoing quality improvement initiative and in order to ensure that quality is comprehensively collected for NVCC, we propose a web-based portal that will enable providers to directly upload anonymized treatment information and the DICOM treatment plan.

INTRODUCTION: Delivery of high-quality cancer care improves oncologic outcomes, including survival and quality of life. The VA National Radiation Oncology (NROP) established the VA Radiation Oncology Quality Surveillance Program (VAROQS) which has developed clinical quality measures (QM) as a measure of quality indices in radiation oncology. We sought to measure quality in community care, assess barriers to data capture, and develop solutions to ensure long term sustainability of continuous quality improvement for veterans that receive dual care, both within the VA and in non-VA community care (NVCC).

METHODS: From 2016-2018, the VA-ROQS project randomly selected three Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) for quality analysis using established QM for prostate cancer, specifically, 6, 16, and 22. NROP manually abstracted data for QM treated in NVCC QMs, which was compared to the performance of the VA QM in the same VISN as well as for all VISNs in the VA.

RESULTS: Out of the 723 NVCC cases that were examined, none were fully evaluable for all 25 Prostate quality metrics. QM was able to be assessed in only 28% of NVCC patients (n=208) reviewed. Only 12/25 (48%) of all Prostate QM were able to be compared between VA and NVCC. Out of the 12 available Prostate QM, 9 were performance, 2 were surveillance, while 1 was an aspirational measure. The overall > 75% pass rate of all the expected performance QM measures for the VA was 13/14 (92%). For NVCC, of the available expected QM for comparison, 8 of which were high potential impact, only 1/9 (11%) QM received a >75% pass rate in all three NVCC VISNs. When examining the 8 high potential impact QM, the VA had a 100% pass rate.

CONCLUSIONS: There are challenges to obtaining data to perform QM assessment from community care. For cases where QM performance could be assessed, VA care outperformed non-VA care. VA-ROQS program is an ongoing quality improvement initiative and in order to ensure that quality is comprehensively collected for NVCC, we propose a web-based portal that will enable providers to directly upload anonymized treatment information and the DICOM treatment plan.

INTRODUCTION: Delivery of high-quality cancer care improves oncologic outcomes, including survival and quality of life. The VA National Radiation Oncology (NROP) established the VA Radiation Oncology Quality Surveillance Program (VAROQS) which has developed clinical quality measures (QM) as a measure of quality indices in radiation oncology. We sought to measure quality in community care, assess barriers to data capture, and develop solutions to ensure long term sustainability of continuous quality improvement for veterans that receive dual care, both within the VA and in non-VA community care (NVCC).

METHODS: From 2016-2018, the VA-ROQS project randomly selected three Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) for quality analysis using established QM for prostate cancer, specifically, 6, 16, and 22. NROP manually abstracted data for QM treated in NVCC QMs, which was compared to the performance of the VA QM in the same VISN as well as for all VISNs in the VA.

RESULTS: Out of the 723 NVCC cases that were examined, none were fully evaluable for all 25 Prostate quality metrics. QM was able to be assessed in only 28% of NVCC patients (n=208) reviewed. Only 12/25 (48%) of all Prostate QM were able to be compared between VA and NVCC. Out of the 12 available Prostate QM, 9 were performance, 2 were surveillance, while 1 was an aspirational measure. The overall > 75% pass rate of all the expected performance QM measures for the VA was 13/14 (92%). For NVCC, of the available expected QM for comparison, 8 of which were high potential impact, only 1/9 (11%) QM received a >75% pass rate in all three NVCC VISNs. When examining the 8 high potential impact QM, the VA had a 100% pass rate.

CONCLUSIONS: There are challenges to obtaining data to perform QM assessment from community care. For cases where QM performance could be assessed, VA care outperformed non-VA care. VA-ROQS program is an ongoing quality improvement initiative and in order to ensure that quality is comprehensively collected for NVCC, we propose a web-based portal that will enable providers to directly upload anonymized treatment information and the DICOM treatment plan.

Positivity Rates in Oropharyngeal and Nonoropharyngeal Head and Neck Cancer in the VA

Head and neck cancer (HNC) continues to be a major health issue with an estimated 51,540 cases in the US in 2018, making it the eighth most common cancer among men with an estimated 4% of all new cancer diagnoses.1 Over the past decade, human papillomavirus (HPV) has emerged as a major prognostic factor for survival in squamous cell carcinomas of the oropharynx. Patients who are HPV-positive (HPV+) have a much higher survival rate than patients who have HPV-negative (HPV-) cancers of the oropharynx. The 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging manual has 2 distinct stagings for HPV+ and HPV- oropharyngeal tumors using p16-positivity (p16+) as a surrogate marker.2

Squamous cell carcinomas of the oropharynx that are HPV+ have about half the risk of death of HPV- tumors, are highly responsive to treatment, and are more often seen in younger and healthier patients with little to no tobacco use.2,3 As such, there also is a movement to de-escalate HPV+ oropharyngeal cancers with multiple trials by either replacing cytotoxic chemotherapy with a targeted agent (cisplatin vs cetuximab in RTOG 1016) or reducing the radiation dose (ECOG 1308, NRG HN002, Quarterback, and OPTIMA trials).3

The focus of many epidemiologic studies has been in the HNC general population. A recent epidemiologic analysis of the HNC general population found a p16 positivity rate of 60% in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (OPSCC) and 10% in nonoropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (NOPSCC).4 There has been a lack of studies focusing on the US Department of Veterans Administration (VA) population. The VA HNC population consists mostly of older white male smokers; whereas the rise of OPSCC in the general population consists primarily of males aged < 60 years often with little or no tobacco use.5 Furthermore, the importance of p16 positivity in NOPSCC also may be prognostic.6 Population data on this subset in the VA are lacking as well.This study’s purpose is to analyze the p16 positivity rate in both the OPSCC and NOPSCC in the VA population. Elucidation of epidemiologic factors that are associated with these groups may bring to light important differences between the VA and general HNC populations.

Methods

A review of the Kansas City VA Medical Center database for patients with HNC was performed from 2011 to 2017. The review consisted of 183 patient records (second primaries were scored separately), and 123 were deemed eligible for the study. Epidemiologic data were collected, including site, OPSCC vs NOPSCC, age, race, education level, tobacco use, alcohol use, TNM stage, and marital status (Table).

Results

The NOPSCC p16+ group had the greatest mean pack-year use (57). The lowest was in the OPSCC p16+ group (29). The OPSCC p16+ group had 37% never smokers compared with ≤ 10% for the other groups. Both the OPSCC and NOPSCC p16- groups had much more alcohol use per week than that of the p16+ groups. The differences in marital status included a lower rate of never married individuals in the p16+ group and a higher rate of marriage in the NOPSCC p16- group. The T stage distribution within the OPSCC groups was similar, but NOPSCC groups saw more T1 lesions in the NOPSCC p16- group (42% p16- vs 18% p16+). Conversely, more T4 lesions were found in the NOPSCC p16+ patients (7% p16- vs 29% p16+).

Discussion

The overall HPV positivity rate in the general population of patients with HNC has been reported as between 57% and 72% for OPSCC and between 1.3% and 7% for NOPSCC.6 One study, however, examined the p16 positivity rate in NOPSCC patients enrolled in major trials (RTOG 0129, 0234, and 0522 studies) and found that up to 19.3% of NOPSCC patients had p16 positivity.6 Even with the near 20% rate in those aforementioned trials that are above the reported norm, the current study found that nearly 30% of its VA population had p16+ NOPSCC. It has been shown that regardless of site, HPV-driven head and neck tumors share a similar gene expression and DNA methylation profiles (nonkeratinizing, basaloid histopathologic features, and lack of TP53 or CDKN2A alterations).5 p16+ NOPSCC has a different immune microenvironment with less lymphocyte infiltration, and there is some debate in the literature about the effects on tumor outcomes for NOPSCC cancer.5

In the aforementioned RTOG trials, p16- NOPSCC had worse outcomes compared with those of p16+ NOPSCC.6 This result is in contrast to the Danish Head and Neck Cancer Group (DAHANCA) and the combined Johns Hopkins University (JHU) and University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) data that found no difference between p16+ NOPSCC or p16- NOPSCC.7,8 In regards to race, this study did not find any differences. Another UCSF and JHU study showed lower p16+ rates in African American patients with OPSCC, but no distinction between race in the NOPSCC group. This result is consistent with the data in the current study as the distribution of race was no different among the 4 groups; however, this study's cohort was 90% white, 10% African American, and only < 1% Native American.4 This study's cohort population also was consistent with HPV-positive tumors presenting with earlier T, but higher N staging.9

Smoking is known to decrease survival in HPV-positive HNC, with the RTOG 0129 study separating head and neck tumors into low, medium, and high risk, based on HPV status, smoking, and stage.10 Although the average smoking pack-years in the current study’s OPC p16+ group was high at 29 pack-years, there was still a significant number of nonsmokers in that same group (37%). The University of Michigan conducted a study that had a similar profile of patients with an average age of 56.5 and 32.4% never smokers in their p16+ OPSCC cohort; thus, the VA p16+ OPSCC group in this study may be similar to the general population's p16+ OPSCC group.11 Nonmonogamous relationships also have been shown to be a risk factor for HPV positivity, and there was a difference in marital status (assuming it was a surrogate for monogamy) between the 4 groups; however, in contrast, the p16+ group in the current study had a high number of married patients, 45% in OPC p16+ group, and may not have been a good surrogate for monogamy in this VA population.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include all the caveats that come with a retrospective study, such as confounding variables, unbalanced groups, and selection bias. A detailed sexual history was not included, although it is well known that sexual activity is linked with oral HPV positivity.12 Human papillomavirus positivity based on p16 immunohistochemical analysis also was used as a surrogate marker for HPV instead of DNA in situ hybridization. The data also may be skewed due to the study patient’s being predominantly white and male: Both groups have a higher predilection for HPV-driven HNCs.13

Conclusion

The proportion of p16+ VA OPSCC cases was similar to that of the general population at 75% with 37% never smokers, but the percentage in NOPSCC was higher at 29% with only 10% never smokers. The p16+ NOPSCC also presented with more T4 lesions and a higher overall stage compared with p16- NOPSCC. Further studies are needed to compare these subgroups in the VA and in the general HNC populations.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7-30.

2. Lydiatt WM, Patel SG, O’Sullivan B, et al. Head and neck cancers major changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):122-137.

3. Mirghani H, Blanchard P. Treatment de-escalation for HPV-driven oropharyngeal cancer: where do we stand? Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2017;8:4-11.

4. D’Souza G, Westra WH, Wang SJ, et al. Differences in the prevalence of human papillomavirus (HPV) in head and neck squamous cell cancers by sex, race, anatomic tumor site, and HPV detection method. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(2):169-177.

5. Chakravarthy A, Henderson S, Thirdborough SM, et al. Human papillomavirus drives tumor development throughout the head and neck: improved prognosis is associated with an immune response largely restricted to the oropharynx. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(34):4132-4141.

6. Chung CH, Zhang Q, Kong CS, et al. p16 protein expression and human papillomavirus status as prognostic biomarkers of nonoropharyngeal head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(35):3930-3938.

7. Lassen P, Primdahl H, Johansen J, et al; Danish Head and Neck Cancer Group (DAHANCA). Impact of HPV-associated p16-expression on radiotherapy outcome in advanced oropharynx and non-oropharynx cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2014;113(3):310-316.

8. Fakhry C, Westra WH, Wang SJ, et al. The prognostic role of sex, race, and human papillomavirus in oropharyngeal and nonoropharyngeal head and neck squamous cell cancer. Cancer. 2017;123(9):1566-1575.

9. Elrefaey S, Massaro MA, Chiocca S, Chiesa F, Ansarin M. HPV in oropharyngeal cancer: the basics to know in clinical practice. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2014;34(5):299-309.

10. Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):24-35.

11. Maxwell, JH, Kumar B, Feng FY, et al. Tobacco use in HPV-positive advanced oropharynx cancer patients related to increased risk of distant metastases and tumor recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(4):1226-1235.

12. Gillison ML, Broutian T, Pickard RK, et al. Prevalence of oral HPV infection in the United States, 2009-2010. JAMA. 2012;307(7):693-703.

13. Benson E, Li R, Eisele D, Fakhry C. The clinical impact of HPV tumor status upon head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Oral Oncol. 2014;50(6):565-574.

Head and neck cancer (HNC) continues to be a major health issue with an estimated 51,540 cases in the US in 2018, making it the eighth most common cancer among men with an estimated 4% of all new cancer diagnoses.1 Over the past decade, human papillomavirus (HPV) has emerged as a major prognostic factor for survival in squamous cell carcinomas of the oropharynx. Patients who are HPV-positive (HPV+) have a much higher survival rate than patients who have HPV-negative (HPV-) cancers of the oropharynx. The 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging manual has 2 distinct stagings for HPV+ and HPV- oropharyngeal tumors using p16-positivity (p16+) as a surrogate marker.2

Squamous cell carcinomas of the oropharynx that are HPV+ have about half the risk of death of HPV- tumors, are highly responsive to treatment, and are more often seen in younger and healthier patients with little to no tobacco use.2,3 As such, there also is a movement to de-escalate HPV+ oropharyngeal cancers with multiple trials by either replacing cytotoxic chemotherapy with a targeted agent (cisplatin vs cetuximab in RTOG 1016) or reducing the radiation dose (ECOG 1308, NRG HN002, Quarterback, and OPTIMA trials).3

The focus of many epidemiologic studies has been in the HNC general population. A recent epidemiologic analysis of the HNC general population found a p16 positivity rate of 60% in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (OPSCC) and 10% in nonoropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (NOPSCC).4 There has been a lack of studies focusing on the US Department of Veterans Administration (VA) population. The VA HNC population consists mostly of older white male smokers; whereas the rise of OPSCC in the general population consists primarily of males aged < 60 years often with little or no tobacco use.5 Furthermore, the importance of p16 positivity in NOPSCC also may be prognostic.6 Population data on this subset in the VA are lacking as well.This study’s purpose is to analyze the p16 positivity rate in both the OPSCC and NOPSCC in the VA population. Elucidation of epidemiologic factors that are associated with these groups may bring to light important differences between the VA and general HNC populations.

Methods

A review of the Kansas City VA Medical Center database for patients with HNC was performed from 2011 to 2017. The review consisted of 183 patient records (second primaries were scored separately), and 123 were deemed eligible for the study. Epidemiologic data were collected, including site, OPSCC vs NOPSCC, age, race, education level, tobacco use, alcohol use, TNM stage, and marital status (Table).

Results

The NOPSCC p16+ group had the greatest mean pack-year use (57). The lowest was in the OPSCC p16+ group (29). The OPSCC p16+ group had 37% never smokers compared with ≤ 10% for the other groups. Both the OPSCC and NOPSCC p16- groups had much more alcohol use per week than that of the p16+ groups. The differences in marital status included a lower rate of never married individuals in the p16+ group and a higher rate of marriage in the NOPSCC p16- group. The T stage distribution within the OPSCC groups was similar, but NOPSCC groups saw more T1 lesions in the NOPSCC p16- group (42% p16- vs 18% p16+). Conversely, more T4 lesions were found in the NOPSCC p16+ patients (7% p16- vs 29% p16+).

Discussion

The overall HPV positivity rate in the general population of patients with HNC has been reported as between 57% and 72% for OPSCC and between 1.3% and 7% for NOPSCC.6 One study, however, examined the p16 positivity rate in NOPSCC patients enrolled in major trials (RTOG 0129, 0234, and 0522 studies) and found that up to 19.3% of NOPSCC patients had p16 positivity.6 Even with the near 20% rate in those aforementioned trials that are above the reported norm, the current study found that nearly 30% of its VA population had p16+ NOPSCC. It has been shown that regardless of site, HPV-driven head and neck tumors share a similar gene expression and DNA methylation profiles (nonkeratinizing, basaloid histopathologic features, and lack of TP53 or CDKN2A alterations).5 p16+ NOPSCC has a different immune microenvironment with less lymphocyte infiltration, and there is some debate in the literature about the effects on tumor outcomes for NOPSCC cancer.5

In the aforementioned RTOG trials, p16- NOPSCC had worse outcomes compared with those of p16+ NOPSCC.6 This result is in contrast to the Danish Head and Neck Cancer Group (DAHANCA) and the combined Johns Hopkins University (JHU) and University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) data that found no difference between p16+ NOPSCC or p16- NOPSCC.7,8 In regards to race, this study did not find any differences. Another UCSF and JHU study showed lower p16+ rates in African American patients with OPSCC, but no distinction between race in the NOPSCC group. This result is consistent with the data in the current study as the distribution of race was no different among the 4 groups; however, this study's cohort was 90% white, 10% African American, and only < 1% Native American.4 This study's cohort population also was consistent with HPV-positive tumors presenting with earlier T, but higher N staging.9

Smoking is known to decrease survival in HPV-positive HNC, with the RTOG 0129 study separating head and neck tumors into low, medium, and high risk, based on HPV status, smoking, and stage.10 Although the average smoking pack-years in the current study’s OPC p16+ group was high at 29 pack-years, there was still a significant number of nonsmokers in that same group (37%). The University of Michigan conducted a study that had a similar profile of patients with an average age of 56.5 and 32.4% never smokers in their p16+ OPSCC cohort; thus, the VA p16+ OPSCC group in this study may be similar to the general population's p16+ OPSCC group.11 Nonmonogamous relationships also have been shown to be a risk factor for HPV positivity, and there was a difference in marital status (assuming it was a surrogate for monogamy) between the 4 groups; however, in contrast, the p16+ group in the current study had a high number of married patients, 45% in OPC p16+ group, and may not have been a good surrogate for monogamy in this VA population.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include all the caveats that come with a retrospective study, such as confounding variables, unbalanced groups, and selection bias. A detailed sexual history was not included, although it is well known that sexual activity is linked with oral HPV positivity.12 Human papillomavirus positivity based on p16 immunohistochemical analysis also was used as a surrogate marker for HPV instead of DNA in situ hybridization. The data also may be skewed due to the study patient’s being predominantly white and male: Both groups have a higher predilection for HPV-driven HNCs.13

Conclusion

The proportion of p16+ VA OPSCC cases was similar to that of the general population at 75% with 37% never smokers, but the percentage in NOPSCC was higher at 29% with only 10% never smokers. The p16+ NOPSCC also presented with more T4 lesions and a higher overall stage compared with p16- NOPSCC. Further studies are needed to compare these subgroups in the VA and in the general HNC populations.

Head and neck cancer (HNC) continues to be a major health issue with an estimated 51,540 cases in the US in 2018, making it the eighth most common cancer among men with an estimated 4% of all new cancer diagnoses.1 Over the past decade, human papillomavirus (HPV) has emerged as a major prognostic factor for survival in squamous cell carcinomas of the oropharynx. Patients who are HPV-positive (HPV+) have a much higher survival rate than patients who have HPV-negative (HPV-) cancers of the oropharynx. The 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging manual has 2 distinct stagings for HPV+ and HPV- oropharyngeal tumors using p16-positivity (p16+) as a surrogate marker.2

Squamous cell carcinomas of the oropharynx that are HPV+ have about half the risk of death of HPV- tumors, are highly responsive to treatment, and are more often seen in younger and healthier patients with little to no tobacco use.2,3 As such, there also is a movement to de-escalate HPV+ oropharyngeal cancers with multiple trials by either replacing cytotoxic chemotherapy with a targeted agent (cisplatin vs cetuximab in RTOG 1016) or reducing the radiation dose (ECOG 1308, NRG HN002, Quarterback, and OPTIMA trials).3

The focus of many epidemiologic studies has been in the HNC general population. A recent epidemiologic analysis of the HNC general population found a p16 positivity rate of 60% in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (OPSCC) and 10% in nonoropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (NOPSCC).4 There has been a lack of studies focusing on the US Department of Veterans Administration (VA) population. The VA HNC population consists mostly of older white male smokers; whereas the rise of OPSCC in the general population consists primarily of males aged < 60 years often with little or no tobacco use.5 Furthermore, the importance of p16 positivity in NOPSCC also may be prognostic.6 Population data on this subset in the VA are lacking as well.This study’s purpose is to analyze the p16 positivity rate in both the OPSCC and NOPSCC in the VA population. Elucidation of epidemiologic factors that are associated with these groups may bring to light important differences between the VA and general HNC populations.

Methods

A review of the Kansas City VA Medical Center database for patients with HNC was performed from 2011 to 2017. The review consisted of 183 patient records (second primaries were scored separately), and 123 were deemed eligible for the study. Epidemiologic data were collected, including site, OPSCC vs NOPSCC, age, race, education level, tobacco use, alcohol use, TNM stage, and marital status (Table).

Results

The NOPSCC p16+ group had the greatest mean pack-year use (57). The lowest was in the OPSCC p16+ group (29). The OPSCC p16+ group had 37% never smokers compared with ≤ 10% for the other groups. Both the OPSCC and NOPSCC p16- groups had much more alcohol use per week than that of the p16+ groups. The differences in marital status included a lower rate of never married individuals in the p16+ group and a higher rate of marriage in the NOPSCC p16- group. The T stage distribution within the OPSCC groups was similar, but NOPSCC groups saw more T1 lesions in the NOPSCC p16- group (42% p16- vs 18% p16+). Conversely, more T4 lesions were found in the NOPSCC p16+ patients (7% p16- vs 29% p16+).

Discussion

The overall HPV positivity rate in the general population of patients with HNC has been reported as between 57% and 72% for OPSCC and between 1.3% and 7% for NOPSCC.6 One study, however, examined the p16 positivity rate in NOPSCC patients enrolled in major trials (RTOG 0129, 0234, and 0522 studies) and found that up to 19.3% of NOPSCC patients had p16 positivity.6 Even with the near 20% rate in those aforementioned trials that are above the reported norm, the current study found that nearly 30% of its VA population had p16+ NOPSCC. It has been shown that regardless of site, HPV-driven head and neck tumors share a similar gene expression and DNA methylation profiles (nonkeratinizing, basaloid histopathologic features, and lack of TP53 or CDKN2A alterations).5 p16+ NOPSCC has a different immune microenvironment with less lymphocyte infiltration, and there is some debate in the literature about the effects on tumor outcomes for NOPSCC cancer.5

In the aforementioned RTOG trials, p16- NOPSCC had worse outcomes compared with those of p16+ NOPSCC.6 This result is in contrast to the Danish Head and Neck Cancer Group (DAHANCA) and the combined Johns Hopkins University (JHU) and University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) data that found no difference between p16+ NOPSCC or p16- NOPSCC.7,8 In regards to race, this study did not find any differences. Another UCSF and JHU study showed lower p16+ rates in African American patients with OPSCC, but no distinction between race in the NOPSCC group. This result is consistent with the data in the current study as the distribution of race was no different among the 4 groups; however, this study's cohort was 90% white, 10% African American, and only < 1% Native American.4 This study's cohort population also was consistent with HPV-positive tumors presenting with earlier T, but higher N staging.9

Smoking is known to decrease survival in HPV-positive HNC, with the RTOG 0129 study separating head and neck tumors into low, medium, and high risk, based on HPV status, smoking, and stage.10 Although the average smoking pack-years in the current study’s OPC p16+ group was high at 29 pack-years, there was still a significant number of nonsmokers in that same group (37%). The University of Michigan conducted a study that had a similar profile of patients with an average age of 56.5 and 32.4% never smokers in their p16+ OPSCC cohort; thus, the VA p16+ OPSCC group in this study may be similar to the general population's p16+ OPSCC group.11 Nonmonogamous relationships also have been shown to be a risk factor for HPV positivity, and there was a difference in marital status (assuming it was a surrogate for monogamy) between the 4 groups; however, in contrast, the p16+ group in the current study had a high number of married patients, 45% in OPC p16+ group, and may not have been a good surrogate for monogamy in this VA population.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include all the caveats that come with a retrospective study, such as confounding variables, unbalanced groups, and selection bias. A detailed sexual history was not included, although it is well known that sexual activity is linked with oral HPV positivity.12 Human papillomavirus positivity based on p16 immunohistochemical analysis also was used as a surrogate marker for HPV instead of DNA in situ hybridization. The data also may be skewed due to the study patient’s being predominantly white and male: Both groups have a higher predilection for HPV-driven HNCs.13

Conclusion

The proportion of p16+ VA OPSCC cases was similar to that of the general population at 75% with 37% never smokers, but the percentage in NOPSCC was higher at 29% with only 10% never smokers. The p16+ NOPSCC also presented with more T4 lesions and a higher overall stage compared with p16- NOPSCC. Further studies are needed to compare these subgroups in the VA and in the general HNC populations.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7-30.

2. Lydiatt WM, Patel SG, O’Sullivan B, et al. Head and neck cancers major changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):122-137.

3. Mirghani H, Blanchard P. Treatment de-escalation for HPV-driven oropharyngeal cancer: where do we stand? Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2017;8:4-11.

4. D’Souza G, Westra WH, Wang SJ, et al. Differences in the prevalence of human papillomavirus (HPV) in head and neck squamous cell cancers by sex, race, anatomic tumor site, and HPV detection method. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(2):169-177.

5. Chakravarthy A, Henderson S, Thirdborough SM, et al. Human papillomavirus drives tumor development throughout the head and neck: improved prognosis is associated with an immune response largely restricted to the oropharynx. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(34):4132-4141.

6. Chung CH, Zhang Q, Kong CS, et al. p16 protein expression and human papillomavirus status as prognostic biomarkers of nonoropharyngeal head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(35):3930-3938.

7. Lassen P, Primdahl H, Johansen J, et al; Danish Head and Neck Cancer Group (DAHANCA). Impact of HPV-associated p16-expression on radiotherapy outcome in advanced oropharynx and non-oropharynx cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2014;113(3):310-316.

8. Fakhry C, Westra WH, Wang SJ, et al. The prognostic role of sex, race, and human papillomavirus in oropharyngeal and nonoropharyngeal head and neck squamous cell cancer. Cancer. 2017;123(9):1566-1575.

9. Elrefaey S, Massaro MA, Chiocca S, Chiesa F, Ansarin M. HPV in oropharyngeal cancer: the basics to know in clinical practice. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2014;34(5):299-309.

10. Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):24-35.

11. Maxwell, JH, Kumar B, Feng FY, et al. Tobacco use in HPV-positive advanced oropharynx cancer patients related to increased risk of distant metastases and tumor recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(4):1226-1235.

12. Gillison ML, Broutian T, Pickard RK, et al. Prevalence of oral HPV infection in the United States, 2009-2010. JAMA. 2012;307(7):693-703.

13. Benson E, Li R, Eisele D, Fakhry C. The clinical impact of HPV tumor status upon head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Oral Oncol. 2014;50(6):565-574.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7-30.

2. Lydiatt WM, Patel SG, O’Sullivan B, et al. Head and neck cancers major changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):122-137.

3. Mirghani H, Blanchard P. Treatment de-escalation for HPV-driven oropharyngeal cancer: where do we stand? Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2017;8:4-11.

4. D’Souza G, Westra WH, Wang SJ, et al. Differences in the prevalence of human papillomavirus (HPV) in head and neck squamous cell cancers by sex, race, anatomic tumor site, and HPV detection method. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(2):169-177.

5. Chakravarthy A, Henderson S, Thirdborough SM, et al. Human papillomavirus drives tumor development throughout the head and neck: improved prognosis is associated with an immune response largely restricted to the oropharynx. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(34):4132-4141.