User login

A Curriculum for Training Medical Faculty to Teach Mental Health Care—and Their Responses to the Learning

From Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI.

Abstract

- Objective: We previously reported that training medical faculty to teach mental health care to residents was effective. We here describe the faculty’s training curriculum and their responses to learning and teaching mental health care, a unique focus in the educational literature.

- Design: Qualitative researchers assessed the experiences of medical faculty trainees in learning and teaching mental health care.

- Setting: Internal medicine residency training program at Michigan State University.

- Participants: One early career medicine faculty learner and another faculty learner at mid-career, 4 faculty trainers, and 2 qualitative researchers.

- Measurements: Typed qualitative research reports were evaluated by the authors from 4 time periods: (1) following didactic and interviewing training; (2) following training in a mental health clinic; (3) following training to teach residents mental health care; and (4) 8 months after training.

- Results: Faculty expressed anxiety and low confidence at each of 3 levels of training, but progressively developed confidence and satisfaction during training at each level. They rated didactic experiences as least valuable, seeing these experiences as lacking practical application. Experiential training in interviewing and mental health care were positively viewed, as was the benefit from mentoring. Teaching mental health skills to residents was initially difficult, but faculty became comfortable with experience, which solidified the faculty’s confidence in their own skills.

- Conclusion: A new curriculum for training medical faculty to teach mental health care was demonstrated to be acceptable to the faculty, based on findings from multiple focus groups.

Keywords: psychiatry; primary care mental health; medical education; curriculum; formative evaluation.

We previously trained general medicine faculty intensively in 3 evidence-based models essential for mental health care.1-4 They, in turn, trained medical residents in the models over all 3 years of residency training.5 The results of this quasi-experimental trial demonstrated highly significant learning by residents on all 3 models.6 To address the mental health care crisis caused by the severe shortage of psychiatrists in the United States,7-14 we propose this train-the-trainer intervention as a model for widescale training of medical faculty in mental health care, thus enabling them to then train their own residents and students indefinitely.6

This brief report details the faculty training curriculum in mental health care and its teaching, along with the responses of medical faculty to the training; no similar training experiences have been reported in the medical or psychiatric literature. While the residency training curriculum has been published,5 the faculty training curriculum has not. Additionally, faculty responses to the training are important because they can provide key information about what did and did not work. Even though demonstrated to be effective for teaching mental health care to residents,6 the training must also be acceptable to its new teachers.15

Methods

Design, Setting, and Participants

This descriptive study was conducted by 2 experienced qualitative researchers in the setting of a 5-year quantitative study of residents’ learning of mental health care.5,6 They interviewed 2 general medicine faculty undergoing training in mental health care on 4 occasions: 3 times during training and once following training. Learners were taught by 4 faculty trainers (2 general medicine, 2 psychiatry). The setting was the internal medicine residency program at Michigan State University. The project was approved by the local Institutional Review Board.

Faculty Training Intervention

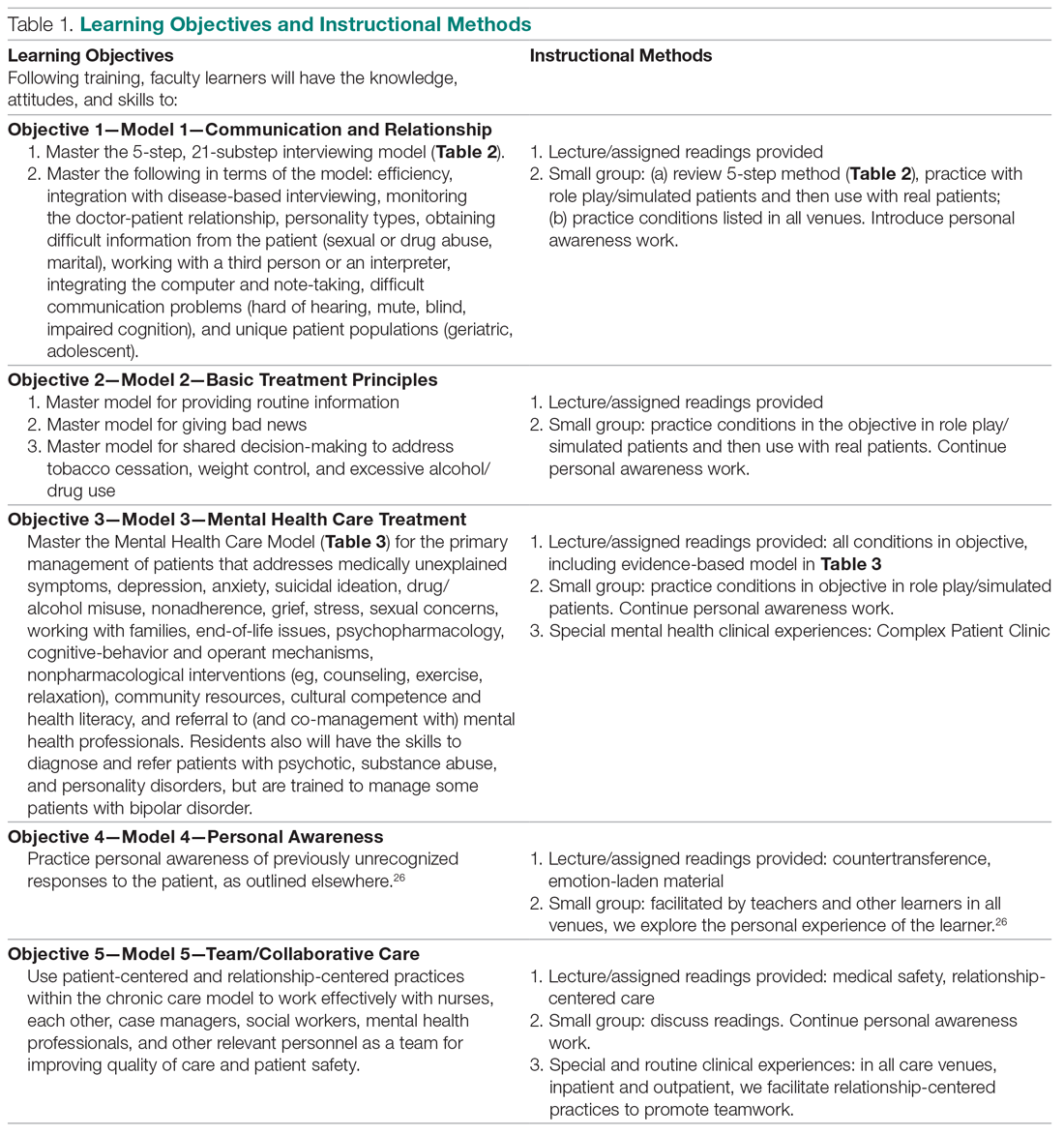

The 2 training faculty evaluated in this study were taught in a predominantly experiential way.5 Learning objectives were behaviorally defined (see Table 1, which also presents the teaching methods). Teaching occurred in 3 segments over 15 months, with a 10% weekly commitment to training supported by a research grant.

First 6 Months. For 1 half-day (4 hours) every week, teaching sessions were divided into 2 parts:

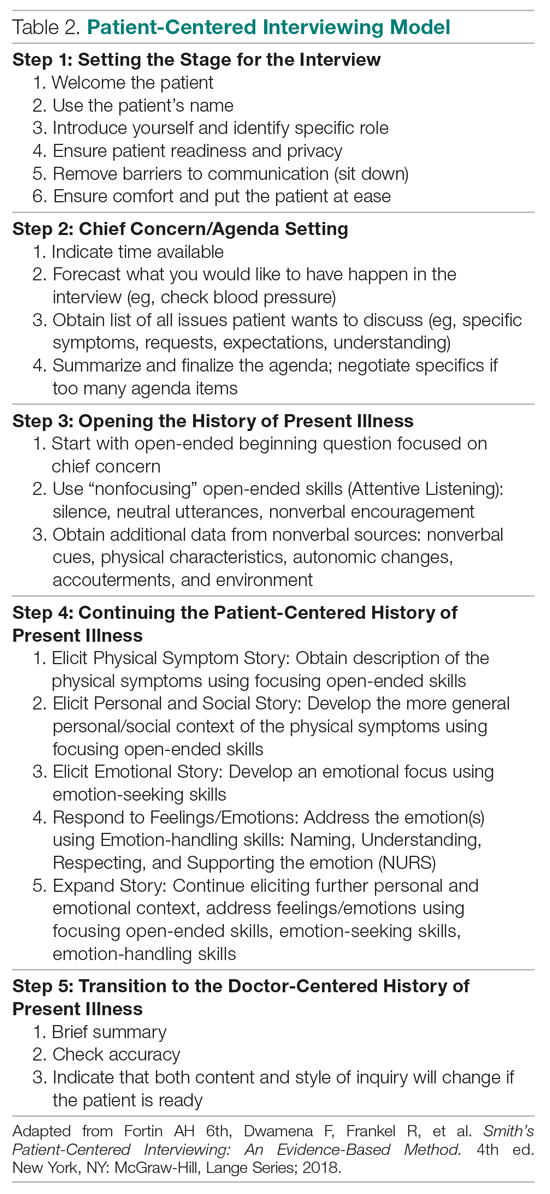

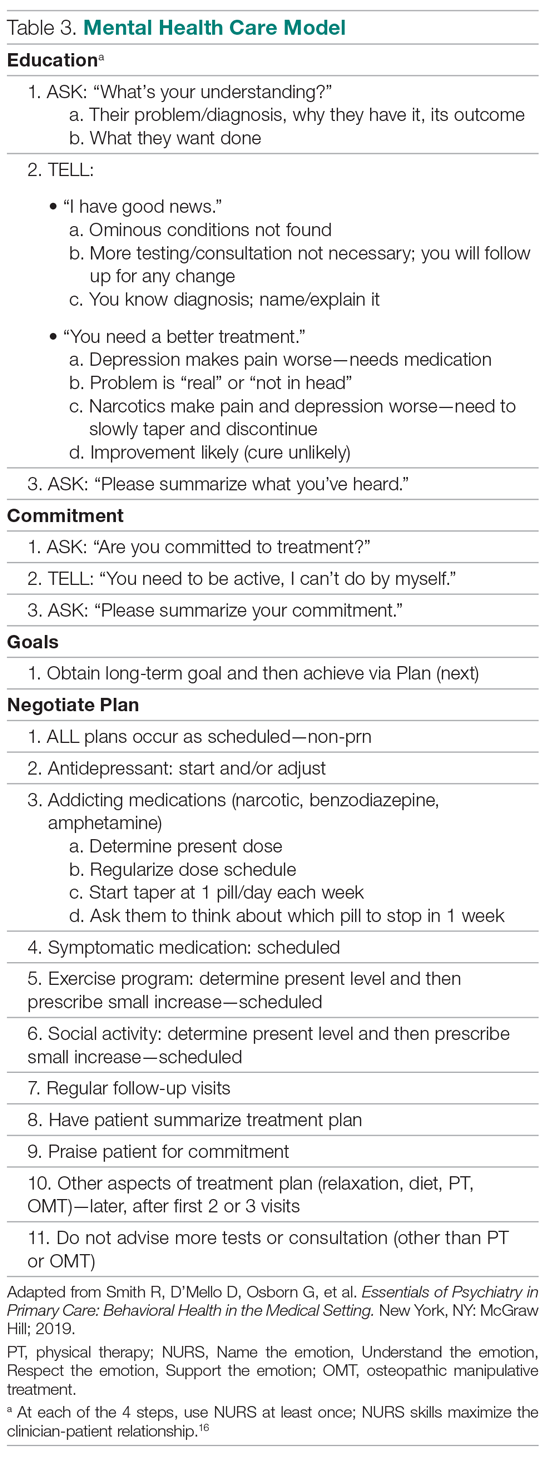

1. Experiential learning of the objectives, particularly patient-centered interviewing (Table 2)16 and mental health care models (Table 3).3,17 This initially involved role playing and was followed by using the models with hospital and clinic patients, sometimes directly observed, other times evaluated via audiotaped recordings.

2. Lecture and reading series, which occurred in 2 parts: (a) For the first 3 months, a biopsychosocial and patient-centered medicine seminar was guided by readings from a patient-centered interviewing textbook and 4 articles.3,16,18-20 These readings were supplemented by a large collection of material on our website that was utilized in a learner-centered fashion, depending on learners’ interests (these are available from the authors, along with a detailed outline we followed for each teaching session). (b) For the last 3 months, a psychiatry lecture series addressed the material needed for primary care mental health. The lectures were guided by a psychiatry textbook (the schedule and content of presentations is available from the authors).21

Beginning in the first 6 months, faculty also participated as co-teachers with their trainers in a long-standing psychosocial rotation, a 1-month full-time rotation for PGY-1 residents that occurred twice yearly during training. This initially helped them learn the models, and they later received experience in how to teach the models.

Middle 4 Months. During this period, faculty learners were supervised by trainers as they transitioned to learn mental health care in a Complex Patient Clinic (CPC). Training was guided by a syllabus now contained in a textbook.17 The CPC is a unique mental health care clinic located in the clinic area where faculty and residents observe other patients. Rooms resemble other exam rooms, except they have a computer attached to an audio-video camera that delivers the physician-patient interaction live to another room, where faculty observe it via a software program (Vidyo, Hackensack, NJ)22,23; no recordings are made of the live interactions. The details of patient recruitment and the CPC are described elsewhere.22 CPC patients had an average of 2.3 DSM-V diagnoses and 3.3 major medical diagnoses. Faculty trainees evaluated 2 or 3 patients each day.

Final 5 Months. Supervision continued for faculty learners as they taught mental health care to postgraduate year (PGY) 2 and 3 residents in the CPC. Residents had between 6 and 8 sessions in each of their last 2 years of training; 2 residents were assigned for each half-day CPC session and each evaluated 2 or 3 patients under faculty-learner supervision.

Data Collection

The qualitative interviewers were independent of the study. The research team members did not see the transcripts until preparing this report in conjunction with the interviewers. Data were collected from faculty at 4 points: following the initial 6 months of training in the models; following training in mental health care in the CPC; following supervision of faculty training of residents; and 8 months following completion of training, during which time they independently taught residents.

Data were collected in a systematic way over 1 hour, beginning and continuing open-endedly for about 30 minutes and concluding with closed-ended inquiry to pin down details and to ask any pre-planned questions that had not been answered. The protocol that guided focus group interviews is available from the authors.

Audio recordings were made from each group, and a 500- to 1000-word report was written by the interviewers, which served as the basis of the present descriptive evaluation. The authors independently analyzed the data at each collection point and then came to the consensus that follows.

Results

Lectures/Didactic Training

The training sessions involved 2 parts: lectures and didactic material around interviewing, general system theory, and psychiatry diagnoses; and skills practice in interviewing and the mental health care models. The trainers and faculty met weekly for 4 hours, and the first 2 hours of these sessions were spent reviewing the background of what would become the mainstay of the teaching, the models for interviewing and mental health care (Table 2 and Table 3). These readings differed in content and style from the typical clinical readings that physicians use, and they required considerable outside time and preparation, beyond that anticipated by the trainees. Digging into these theoretical concepts was described as interesting and “refreshing,” but the trainees at first found the readings disconnected from their clinical work. Faculty trainees later recognized the importance of understanding the models as they prepared for their roles as teachers. All told, however, the trainees believed there was too much didactic material.

Receiving education on diagnosis and management of common psychiatric disorders from academic psychiatrists was appreciated, but the trainees also expressed the greatest frustrations about this part of the curriculum. They felt that the level of these sessions was not always appropriately gauged—ranging from too simplistic, as in medical school, to too detailed, especially around neurochemical and neurobiological mechanisms. Although they appreciated learning about advanced psychiatric illness and treatments (eg, electroconvulsive treatment, especially), they did not believe the information was necessary in primary care. Trainees were experienced primary care providers and were more interested in case-based education that could highlight the types of patients seen in their office every day. One trainee indicated that these sessions were lacking “the patient voice.” Abstract discussion of diagnoses and treatments made it challenging to apply this new knowledge to the trainees’ practices. Trainees also suggested trying to integrate this section of the training with the interviewing skills training to better highlight that interplay. The trainees believed that their understanding and familiarity with the diagnosis and management of mental disorders occurred primarily in later CPC training. The trainees recommended that all didactic material be reduced by half or more in future teaching.

Skills Practice

The patient-centered interviewing skills practice, which occurred in the second 2-hour period during the first 6 months, was lauded by the faculty trainees. It was considered the “most immediately relevant component” of this period of training. Because the trainees were experienced physicians when they began this project, they felt this part of training made the “…material more accessible to myself, more germane to what I do day in and day out.” The insight of modifying the interviewing techniques to connect with different patient personality types was particularly helpful. One trainee described an “aha moment” of “getting patients to open up in a way I had not been able to do before.” As time went on, the trainees felt empowered to adapt “the interviewing script” modestly to fit their already developed “rhythm and style with their patients.”

Wellness/Mentoring

The 2 trainees were at different stages of their careers, 1 early-career faculty and 1 mid-career faculty. This academic diversity within the small training group provided varied perspectives not only on the concepts presented and discussed, but also on a more personal level. In an otherwise hectic academic medicine environment, this group had a weekly chance to stop, “check in” with each other, and truly connect on a personal level. To be asked “about your week and actually mean it and want to hear the answer” is an unusual opportunity, one noted. It also offered time and support for purposeful self-reflection, which “often brought some emotions to the surface…at different times.” These connections were perhaps one of the most valuable parts of the experience. With burnout among physicians rampant,24 establishing these networks is invaluable. In addition to introspection and personal connections, there was a strong element of mentoring during these weekly meetings. The opportunity to meet in a small group with senior faculty was highly valued by the trainees.

Mental Health Care: Complex Patient Clinic

The faculty were eager, but very apprehensive, in beginning the second segment of training, where work shifted from lectures and practicing skills to mental health care training in the CPC. The trainees expressed anxiety about several areas. These included additional clinical workload, patient referral/selection, and transition of patient care back to the primary care provider. Of note, they did not particularly express worries about the care they would be providing, because a psychiatrist would be available to them on site. In reflection, after spending 4 months in the clinic, trainees noted “how important observing live interviews for evaluation/feedback was to their learning.” The CPC provided “learning in the moment on specific patients [which] was without question the most powerful teaching tool.” The support of the training faculty who were present at each clinic was invaluable. Whereas the earlier didactics given by psychiatrists were received by trainees with lukewarm enthusiasm, the point-of-care, case-by-case learning and feedback truly advanced the trainees’ knowledge, as well as skills, and improved their confidence in providing mental health care.

One of the tenets of the mental health care models is collaborative care.25 Recognizing this critical component of patient care, the CPC experience integrated a clinical social worker. The faculty noted the critical role she played in the patient care experience. They described her as “fabulous and awesome.” Her grasp of the health care system and community resources (particularly for an underserved population) was indispensable. Additionally, she was able to serve as a steady contact to follow patients through multiple visits and improve their feelings of continuity.

Teaching: Psychosocial Rotation

The first psychosocial teaching occurred after the interviewing skills and didactic experiences in the first 6 months. The trainees expressed great doubt about tackling this initial teaching experience. From residents challenging the need for interviewing and other aspects of “touchy-feely” teaching, to patients expressing raw emotions, the trainees lacked confidence in their ability to handle these moments. At this early stage of their training, one trainee said, “I feel like I am becoming a better interrogator, but I haven’t learned the skills to be a better healer yet.” Over time, this concern disappeared. As training evolved, the trainees began to thrive in their role as educator. At the final focus group, it was noted that “teaching has enhanced [my] confidence in the framework and in turn has made it easier to teach.”

Teaching: Complex Patient Clinic

This powerful teaching tool to train residents was the centerpiece of training. The faculty trainees had some hesitation about their role as teacher before it began. The faculty trainees were at different stages of their careers, and their confidence in their own teaching skills was not uniform. Importantly, the initial structure of the CPC, which included psychiatrists and senior faculty supervision, provided strong and continued support for the faculty trainees. Later work in the CPC as teacher, rather than trainee, further bolstered the faculty’s confidence in the treatment models. As confidence with their own skills grew, faculty noted that it became “easier to teach” as well. Faculty also recognized the unique opportunity that the CPC provided in directly observing a resident’s patient interaction. This allows them to “monitor progress, provide specific feedback, and address issues.” The time spent debriefing after each patient encounter was noted to be particularly important. When they became too busy to adequately provide this debriefing, changes to the schedule were made to accommodate it (follow-up visits were lengthened from 30 to 60 minutes). In addition to giving an opportunity to provide feedback, this extra time available for residents to interact with a patient—to utilize and practice the interviewing skills, for example—was quite valuable, independent of actual mental health care training. Finally, the faculty were able to create a “relaxed and comfortable” space in the CPC. Indeed, the faculty felt comfortable sharing some of their struggles and reflections on caring for a mental health patient population, and residents were able, in turn, to engage in some self-reflection and debriefing as well.

Discussion

Faculty trainees demonstrated a striking evolution as they progressed through this curriculum. At each of the 3 stages of training, they endorsed a broad range of feelings, from anxiety and uncertainty initially, to confidence and growth and appreciation later. They felt satisfied with having participated in the project and are engaged in exploring next steps.

Of note, these faculty members had some exposure to the skills models prior to starting the program because the residency program has integrated patient-centered interviewing into its program for many years. The faculty were supportive of the models prior to engaging in the curriculum, and they volunteered to participate. Similarly, the residents were familiar with the expectations as they went through the psychosocial rotation and the CPC. It is conceivable that the interviewing and mental health material may not be received as easily at an institution where the culture has had less exposure to such teaching.

While describing a faculty curriculum for mental health training is unique5 and the primary intent of this paper, we wanted to present its formative evaluation even though only 2 faculty trainees were involved. Simply put, the grant for this project supported only 2 trainees, and no more were required. Nevertheless, we propose that this only reported experience of medical faculty with mental health training is an important addition to the literature in mental health education. It will be a critical guide for others who choose the new direction of training medical faculty to teach mental health care.

As the research team looks to foster dissemination of the curriculum, it continues to be streamlined to highlight the components most useful and germane to learners. The early didactic readings on subjects such as general system theory were less engaging. (In later training of new medical faculty learners, the focus on theory and other didactics was reduced.) In contrast, the trainees clearly valued the interviewing skills experience (both learning and teaching). While the mental health curriculum and the CPC were associated with much greater anxiety in the trainees, with practical, respectful, and supervised teaching, they became confident and satisfied—as well as effective.6 Future teachers will benefit from slowly and understandingly addressing trainees’ personal issues, particularly during the initial phases of training.26 It appeared to us to be the key factor enabling the faculty to successfully learn and teach mental health care. Once they overcame their personal reactions to mental health material, they learned mental health skills just as they learn the more familiar physical disease material.

Conclusion

In a new direction in medical education, a curriculum for training medical faculty to teach mental health care is presented. Not only did prior research demonstrate that the faculty effectively trained residents, but we also demonstrated here that the training was acceptable to and valued by faculty. With mental health often an alien dimension of medicine, acceptability is especially important when we recommend disseminating the curriculum as a way to offset the national mental health care crisis.

Corresponding author: Robert C. Smith, 788 Service Road, B314 Clinical Center, East Lansing, MI 48824; smithrr@msu.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

Funding support: The authors are grateful for the generous support from the Health Resources and Services Administration (D58HP23259).

1. Smith R, Gardiner J, Luo Z, et al. Primary care physicians treat somatization. J Gen Int Med. 2009;24:829-832.

2. Smith RC, Lyles JS, Gardiner JC, et al. Primary care clinicians treat patients with medically unexplained symptoms—a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:671-677.

3. Smith RC, Lein C, Collins C, et al. Treating patients with medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:478-489.

4. Smith RC, Lyles JS, Mettler J, et al. The effectiveness of intensive training for residents in interviewing. A randomized, controlled study. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:118-126.

5. Smith R, Laird-Fick H, D’Mello D, et al. Addressing mental health issues in primary care: an initial curriculum for medical residents. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94:33-42.

6. Smith R, Laird-Fick H, Dwamena F, et al. Teaching residents mental health care. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101:2145-2155.

7. Cunningham PJ. Beyond parity: primary care physicians’ perspectives on access to mental health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28:w490-501.

8. US Department of Health and Human Services: Healthy People 2020: The Road Ahead. Washington, DC: US Governmant Printing Office; 2011.

9. US Department of Health and Human Services. Facing Addiction in America—The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2016.

10. US Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health and Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2000.

11. Hogan MF. The President’s New Freedom Commission: recommendations to transform mental health care in America. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:1467-1474.

12. Morrisey J, Thomas K, Ellis A, et al. Development of a New Method for Designation of Mental Health Professional Shortage Areas. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2007.

13. US Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: a Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Dept. of Health and Human Services; 1999.

14. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:629-640.

15. Kern DE, Thomas PA, Hughes MT. Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six-Step Approach. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2009.

16. Fortin 6th AH, Dwamena F, Frankel R, et al. Smith’s Patient-Centered Interviewing: An Evidence-Based Method. 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2018.

17. Smith R, D’Mello D, Osborn G, et al. Essentials of Psychiatry in Primary Care: Behavioral Health in the Medical Setting. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2019 .

18. Smith R, Fortin AH 6th, Dwamena F, et al. An evidence-based patient-centered method makes the biopsychosocial model scientific. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;90:265-270.

19. Smith R, Dwamena F, Grover M, et al. Behaviorally-defined patient-centered communication—a narrative review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;26:185-191.

20. Smith RC, Dwamena FC. Classification and diagnosis of patients with medically unexplained symptoms. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:685-691.

21. Schneider RK, Levenson JL. Psychiatry Essentials for Primary Care. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Physicians; 2008.

22. Dwamena F, Laird-Fick H, Freilich L, et al. Behavioral health problems in medical patients. J Clin Outcomes Manage. 2014;21:497-505.

23. Vidyo (Hackensack, NJ). http://www.vidyo.com/products/use/. 2014.

24. Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:195-205.

25. Huffman JC, Niazi SK, Rundell JR, et al. Essential articles on collaborative care models for the treatment of psychiatric disorders in medical settings: a publication by the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine Research and Evidence-Based Practice Committee. Psychosomatics. 2014;55:109-122.

26. Smith RC, Dwamena FC, Fortin AH 6th. Teaching personal awareness. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:201-207.

From Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI.

Abstract

- Objective: We previously reported that training medical faculty to teach mental health care to residents was effective. We here describe the faculty’s training curriculum and their responses to learning and teaching mental health care, a unique focus in the educational literature.

- Design: Qualitative researchers assessed the experiences of medical faculty trainees in learning and teaching mental health care.

- Setting: Internal medicine residency training program at Michigan State University.

- Participants: One early career medicine faculty learner and another faculty learner at mid-career, 4 faculty trainers, and 2 qualitative researchers.

- Measurements: Typed qualitative research reports were evaluated by the authors from 4 time periods: (1) following didactic and interviewing training; (2) following training in a mental health clinic; (3) following training to teach residents mental health care; and (4) 8 months after training.

- Results: Faculty expressed anxiety and low confidence at each of 3 levels of training, but progressively developed confidence and satisfaction during training at each level. They rated didactic experiences as least valuable, seeing these experiences as lacking practical application. Experiential training in interviewing and mental health care were positively viewed, as was the benefit from mentoring. Teaching mental health skills to residents was initially difficult, but faculty became comfortable with experience, which solidified the faculty’s confidence in their own skills.

- Conclusion: A new curriculum for training medical faculty to teach mental health care was demonstrated to be acceptable to the faculty, based on findings from multiple focus groups.

Keywords: psychiatry; primary care mental health; medical education; curriculum; formative evaluation.

We previously trained general medicine faculty intensively in 3 evidence-based models essential for mental health care.1-4 They, in turn, trained medical residents in the models over all 3 years of residency training.5 The results of this quasi-experimental trial demonstrated highly significant learning by residents on all 3 models.6 To address the mental health care crisis caused by the severe shortage of psychiatrists in the United States,7-14 we propose this train-the-trainer intervention as a model for widescale training of medical faculty in mental health care, thus enabling them to then train their own residents and students indefinitely.6

This brief report details the faculty training curriculum in mental health care and its teaching, along with the responses of medical faculty to the training; no similar training experiences have been reported in the medical or psychiatric literature. While the residency training curriculum has been published,5 the faculty training curriculum has not. Additionally, faculty responses to the training are important because they can provide key information about what did and did not work. Even though demonstrated to be effective for teaching mental health care to residents,6 the training must also be acceptable to its new teachers.15

Methods

Design, Setting, and Participants

This descriptive study was conducted by 2 experienced qualitative researchers in the setting of a 5-year quantitative study of residents’ learning of mental health care.5,6 They interviewed 2 general medicine faculty undergoing training in mental health care on 4 occasions: 3 times during training and once following training. Learners were taught by 4 faculty trainers (2 general medicine, 2 psychiatry). The setting was the internal medicine residency program at Michigan State University. The project was approved by the local Institutional Review Board.

Faculty Training Intervention

The 2 training faculty evaluated in this study were taught in a predominantly experiential way.5 Learning objectives were behaviorally defined (see Table 1, which also presents the teaching methods). Teaching occurred in 3 segments over 15 months, with a 10% weekly commitment to training supported by a research grant.

First 6 Months. For 1 half-day (4 hours) every week, teaching sessions were divided into 2 parts:

1. Experiential learning of the objectives, particularly patient-centered interviewing (Table 2)16 and mental health care models (Table 3).3,17 This initially involved role playing and was followed by using the models with hospital and clinic patients, sometimes directly observed, other times evaluated via audiotaped recordings.

2. Lecture and reading series, which occurred in 2 parts: (a) For the first 3 months, a biopsychosocial and patient-centered medicine seminar was guided by readings from a patient-centered interviewing textbook and 4 articles.3,16,18-20 These readings were supplemented by a large collection of material on our website that was utilized in a learner-centered fashion, depending on learners’ interests (these are available from the authors, along with a detailed outline we followed for each teaching session). (b) For the last 3 months, a psychiatry lecture series addressed the material needed for primary care mental health. The lectures were guided by a psychiatry textbook (the schedule and content of presentations is available from the authors).21

Beginning in the first 6 months, faculty also participated as co-teachers with their trainers in a long-standing psychosocial rotation, a 1-month full-time rotation for PGY-1 residents that occurred twice yearly during training. This initially helped them learn the models, and they later received experience in how to teach the models.

Middle 4 Months. During this period, faculty learners were supervised by trainers as they transitioned to learn mental health care in a Complex Patient Clinic (CPC). Training was guided by a syllabus now contained in a textbook.17 The CPC is a unique mental health care clinic located in the clinic area where faculty and residents observe other patients. Rooms resemble other exam rooms, except they have a computer attached to an audio-video camera that delivers the physician-patient interaction live to another room, where faculty observe it via a software program (Vidyo, Hackensack, NJ)22,23; no recordings are made of the live interactions. The details of patient recruitment and the CPC are described elsewhere.22 CPC patients had an average of 2.3 DSM-V diagnoses and 3.3 major medical diagnoses. Faculty trainees evaluated 2 or 3 patients each day.

Final 5 Months. Supervision continued for faculty learners as they taught mental health care to postgraduate year (PGY) 2 and 3 residents in the CPC. Residents had between 6 and 8 sessions in each of their last 2 years of training; 2 residents were assigned for each half-day CPC session and each evaluated 2 or 3 patients under faculty-learner supervision.

Data Collection

The qualitative interviewers were independent of the study. The research team members did not see the transcripts until preparing this report in conjunction with the interviewers. Data were collected from faculty at 4 points: following the initial 6 months of training in the models; following training in mental health care in the CPC; following supervision of faculty training of residents; and 8 months following completion of training, during which time they independently taught residents.

Data were collected in a systematic way over 1 hour, beginning and continuing open-endedly for about 30 minutes and concluding with closed-ended inquiry to pin down details and to ask any pre-planned questions that had not been answered. The protocol that guided focus group interviews is available from the authors.

Audio recordings were made from each group, and a 500- to 1000-word report was written by the interviewers, which served as the basis of the present descriptive evaluation. The authors independently analyzed the data at each collection point and then came to the consensus that follows.

Results

Lectures/Didactic Training

The training sessions involved 2 parts: lectures and didactic material around interviewing, general system theory, and psychiatry diagnoses; and skills practice in interviewing and the mental health care models. The trainers and faculty met weekly for 4 hours, and the first 2 hours of these sessions were spent reviewing the background of what would become the mainstay of the teaching, the models for interviewing and mental health care (Table 2 and Table 3). These readings differed in content and style from the typical clinical readings that physicians use, and they required considerable outside time and preparation, beyond that anticipated by the trainees. Digging into these theoretical concepts was described as interesting and “refreshing,” but the trainees at first found the readings disconnected from their clinical work. Faculty trainees later recognized the importance of understanding the models as they prepared for their roles as teachers. All told, however, the trainees believed there was too much didactic material.

Receiving education on diagnosis and management of common psychiatric disorders from academic psychiatrists was appreciated, but the trainees also expressed the greatest frustrations about this part of the curriculum. They felt that the level of these sessions was not always appropriately gauged—ranging from too simplistic, as in medical school, to too detailed, especially around neurochemical and neurobiological mechanisms. Although they appreciated learning about advanced psychiatric illness and treatments (eg, electroconvulsive treatment, especially), they did not believe the information was necessary in primary care. Trainees were experienced primary care providers and were more interested in case-based education that could highlight the types of patients seen in their office every day. One trainee indicated that these sessions were lacking “the patient voice.” Abstract discussion of diagnoses and treatments made it challenging to apply this new knowledge to the trainees’ practices. Trainees also suggested trying to integrate this section of the training with the interviewing skills training to better highlight that interplay. The trainees believed that their understanding and familiarity with the diagnosis and management of mental disorders occurred primarily in later CPC training. The trainees recommended that all didactic material be reduced by half or more in future teaching.

Skills Practice

The patient-centered interviewing skills practice, which occurred in the second 2-hour period during the first 6 months, was lauded by the faculty trainees. It was considered the “most immediately relevant component” of this period of training. Because the trainees were experienced physicians when they began this project, they felt this part of training made the “…material more accessible to myself, more germane to what I do day in and day out.” The insight of modifying the interviewing techniques to connect with different patient personality types was particularly helpful. One trainee described an “aha moment” of “getting patients to open up in a way I had not been able to do before.” As time went on, the trainees felt empowered to adapt “the interviewing script” modestly to fit their already developed “rhythm and style with their patients.”

Wellness/Mentoring

The 2 trainees were at different stages of their careers, 1 early-career faculty and 1 mid-career faculty. This academic diversity within the small training group provided varied perspectives not only on the concepts presented and discussed, but also on a more personal level. In an otherwise hectic academic medicine environment, this group had a weekly chance to stop, “check in” with each other, and truly connect on a personal level. To be asked “about your week and actually mean it and want to hear the answer” is an unusual opportunity, one noted. It also offered time and support for purposeful self-reflection, which “often brought some emotions to the surface…at different times.” These connections were perhaps one of the most valuable parts of the experience. With burnout among physicians rampant,24 establishing these networks is invaluable. In addition to introspection and personal connections, there was a strong element of mentoring during these weekly meetings. The opportunity to meet in a small group with senior faculty was highly valued by the trainees.

Mental Health Care: Complex Patient Clinic

The faculty were eager, but very apprehensive, in beginning the second segment of training, where work shifted from lectures and practicing skills to mental health care training in the CPC. The trainees expressed anxiety about several areas. These included additional clinical workload, patient referral/selection, and transition of patient care back to the primary care provider. Of note, they did not particularly express worries about the care they would be providing, because a psychiatrist would be available to them on site. In reflection, after spending 4 months in the clinic, trainees noted “how important observing live interviews for evaluation/feedback was to their learning.” The CPC provided “learning in the moment on specific patients [which] was without question the most powerful teaching tool.” The support of the training faculty who were present at each clinic was invaluable. Whereas the earlier didactics given by psychiatrists were received by trainees with lukewarm enthusiasm, the point-of-care, case-by-case learning and feedback truly advanced the trainees’ knowledge, as well as skills, and improved their confidence in providing mental health care.

One of the tenets of the mental health care models is collaborative care.25 Recognizing this critical component of patient care, the CPC experience integrated a clinical social worker. The faculty noted the critical role she played in the patient care experience. They described her as “fabulous and awesome.” Her grasp of the health care system and community resources (particularly for an underserved population) was indispensable. Additionally, she was able to serve as a steady contact to follow patients through multiple visits and improve their feelings of continuity.

Teaching: Psychosocial Rotation

The first psychosocial teaching occurred after the interviewing skills and didactic experiences in the first 6 months. The trainees expressed great doubt about tackling this initial teaching experience. From residents challenging the need for interviewing and other aspects of “touchy-feely” teaching, to patients expressing raw emotions, the trainees lacked confidence in their ability to handle these moments. At this early stage of their training, one trainee said, “I feel like I am becoming a better interrogator, but I haven’t learned the skills to be a better healer yet.” Over time, this concern disappeared. As training evolved, the trainees began to thrive in their role as educator. At the final focus group, it was noted that “teaching has enhanced [my] confidence in the framework and in turn has made it easier to teach.”

Teaching: Complex Patient Clinic

This powerful teaching tool to train residents was the centerpiece of training. The faculty trainees had some hesitation about their role as teacher before it began. The faculty trainees were at different stages of their careers, and their confidence in their own teaching skills was not uniform. Importantly, the initial structure of the CPC, which included psychiatrists and senior faculty supervision, provided strong and continued support for the faculty trainees. Later work in the CPC as teacher, rather than trainee, further bolstered the faculty’s confidence in the treatment models. As confidence with their own skills grew, faculty noted that it became “easier to teach” as well. Faculty also recognized the unique opportunity that the CPC provided in directly observing a resident’s patient interaction. This allows them to “monitor progress, provide specific feedback, and address issues.” The time spent debriefing after each patient encounter was noted to be particularly important. When they became too busy to adequately provide this debriefing, changes to the schedule were made to accommodate it (follow-up visits were lengthened from 30 to 60 minutes). In addition to giving an opportunity to provide feedback, this extra time available for residents to interact with a patient—to utilize and practice the interviewing skills, for example—was quite valuable, independent of actual mental health care training. Finally, the faculty were able to create a “relaxed and comfortable” space in the CPC. Indeed, the faculty felt comfortable sharing some of their struggles and reflections on caring for a mental health patient population, and residents were able, in turn, to engage in some self-reflection and debriefing as well.

Discussion

Faculty trainees demonstrated a striking evolution as they progressed through this curriculum. At each of the 3 stages of training, they endorsed a broad range of feelings, from anxiety and uncertainty initially, to confidence and growth and appreciation later. They felt satisfied with having participated in the project and are engaged in exploring next steps.

Of note, these faculty members had some exposure to the skills models prior to starting the program because the residency program has integrated patient-centered interviewing into its program for many years. The faculty were supportive of the models prior to engaging in the curriculum, and they volunteered to participate. Similarly, the residents were familiar with the expectations as they went through the psychosocial rotation and the CPC. It is conceivable that the interviewing and mental health material may not be received as easily at an institution where the culture has had less exposure to such teaching.

While describing a faculty curriculum for mental health training is unique5 and the primary intent of this paper, we wanted to present its formative evaluation even though only 2 faculty trainees were involved. Simply put, the grant for this project supported only 2 trainees, and no more were required. Nevertheless, we propose that this only reported experience of medical faculty with mental health training is an important addition to the literature in mental health education. It will be a critical guide for others who choose the new direction of training medical faculty to teach mental health care.

As the research team looks to foster dissemination of the curriculum, it continues to be streamlined to highlight the components most useful and germane to learners. The early didactic readings on subjects such as general system theory were less engaging. (In later training of new medical faculty learners, the focus on theory and other didactics was reduced.) In contrast, the trainees clearly valued the interviewing skills experience (both learning and teaching). While the mental health curriculum and the CPC were associated with much greater anxiety in the trainees, with practical, respectful, and supervised teaching, they became confident and satisfied—as well as effective.6 Future teachers will benefit from slowly and understandingly addressing trainees’ personal issues, particularly during the initial phases of training.26 It appeared to us to be the key factor enabling the faculty to successfully learn and teach mental health care. Once they overcame their personal reactions to mental health material, they learned mental health skills just as they learn the more familiar physical disease material.

Conclusion

In a new direction in medical education, a curriculum for training medical faculty to teach mental health care is presented. Not only did prior research demonstrate that the faculty effectively trained residents, but we also demonstrated here that the training was acceptable to and valued by faculty. With mental health often an alien dimension of medicine, acceptability is especially important when we recommend disseminating the curriculum as a way to offset the national mental health care crisis.

Corresponding author: Robert C. Smith, 788 Service Road, B314 Clinical Center, East Lansing, MI 48824; smithrr@msu.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

Funding support: The authors are grateful for the generous support from the Health Resources and Services Administration (D58HP23259).

From Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI.

Abstract

- Objective: We previously reported that training medical faculty to teach mental health care to residents was effective. We here describe the faculty’s training curriculum and their responses to learning and teaching mental health care, a unique focus in the educational literature.

- Design: Qualitative researchers assessed the experiences of medical faculty trainees in learning and teaching mental health care.

- Setting: Internal medicine residency training program at Michigan State University.

- Participants: One early career medicine faculty learner and another faculty learner at mid-career, 4 faculty trainers, and 2 qualitative researchers.

- Measurements: Typed qualitative research reports were evaluated by the authors from 4 time periods: (1) following didactic and interviewing training; (2) following training in a mental health clinic; (3) following training to teach residents mental health care; and (4) 8 months after training.

- Results: Faculty expressed anxiety and low confidence at each of 3 levels of training, but progressively developed confidence and satisfaction during training at each level. They rated didactic experiences as least valuable, seeing these experiences as lacking practical application. Experiential training in interviewing and mental health care were positively viewed, as was the benefit from mentoring. Teaching mental health skills to residents was initially difficult, but faculty became comfortable with experience, which solidified the faculty’s confidence in their own skills.

- Conclusion: A new curriculum for training medical faculty to teach mental health care was demonstrated to be acceptable to the faculty, based on findings from multiple focus groups.

Keywords: psychiatry; primary care mental health; medical education; curriculum; formative evaluation.

We previously trained general medicine faculty intensively in 3 evidence-based models essential for mental health care.1-4 They, in turn, trained medical residents in the models over all 3 years of residency training.5 The results of this quasi-experimental trial demonstrated highly significant learning by residents on all 3 models.6 To address the mental health care crisis caused by the severe shortage of psychiatrists in the United States,7-14 we propose this train-the-trainer intervention as a model for widescale training of medical faculty in mental health care, thus enabling them to then train their own residents and students indefinitely.6

This brief report details the faculty training curriculum in mental health care and its teaching, along with the responses of medical faculty to the training; no similar training experiences have been reported in the medical or psychiatric literature. While the residency training curriculum has been published,5 the faculty training curriculum has not. Additionally, faculty responses to the training are important because they can provide key information about what did and did not work. Even though demonstrated to be effective for teaching mental health care to residents,6 the training must also be acceptable to its new teachers.15

Methods

Design, Setting, and Participants

This descriptive study was conducted by 2 experienced qualitative researchers in the setting of a 5-year quantitative study of residents’ learning of mental health care.5,6 They interviewed 2 general medicine faculty undergoing training in mental health care on 4 occasions: 3 times during training and once following training. Learners were taught by 4 faculty trainers (2 general medicine, 2 psychiatry). The setting was the internal medicine residency program at Michigan State University. The project was approved by the local Institutional Review Board.

Faculty Training Intervention

The 2 training faculty evaluated in this study were taught in a predominantly experiential way.5 Learning objectives were behaviorally defined (see Table 1, which also presents the teaching methods). Teaching occurred in 3 segments over 15 months, with a 10% weekly commitment to training supported by a research grant.

First 6 Months. For 1 half-day (4 hours) every week, teaching sessions were divided into 2 parts:

1. Experiential learning of the objectives, particularly patient-centered interviewing (Table 2)16 and mental health care models (Table 3).3,17 This initially involved role playing and was followed by using the models with hospital and clinic patients, sometimes directly observed, other times evaluated via audiotaped recordings.

2. Lecture and reading series, which occurred in 2 parts: (a) For the first 3 months, a biopsychosocial and patient-centered medicine seminar was guided by readings from a patient-centered interviewing textbook and 4 articles.3,16,18-20 These readings were supplemented by a large collection of material on our website that was utilized in a learner-centered fashion, depending on learners’ interests (these are available from the authors, along with a detailed outline we followed for each teaching session). (b) For the last 3 months, a psychiatry lecture series addressed the material needed for primary care mental health. The lectures were guided by a psychiatry textbook (the schedule and content of presentations is available from the authors).21

Beginning in the first 6 months, faculty also participated as co-teachers with their trainers in a long-standing psychosocial rotation, a 1-month full-time rotation for PGY-1 residents that occurred twice yearly during training. This initially helped them learn the models, and they later received experience in how to teach the models.

Middle 4 Months. During this period, faculty learners were supervised by trainers as they transitioned to learn mental health care in a Complex Patient Clinic (CPC). Training was guided by a syllabus now contained in a textbook.17 The CPC is a unique mental health care clinic located in the clinic area where faculty and residents observe other patients. Rooms resemble other exam rooms, except they have a computer attached to an audio-video camera that delivers the physician-patient interaction live to another room, where faculty observe it via a software program (Vidyo, Hackensack, NJ)22,23; no recordings are made of the live interactions. The details of patient recruitment and the CPC are described elsewhere.22 CPC patients had an average of 2.3 DSM-V diagnoses and 3.3 major medical diagnoses. Faculty trainees evaluated 2 or 3 patients each day.

Final 5 Months. Supervision continued for faculty learners as they taught mental health care to postgraduate year (PGY) 2 and 3 residents in the CPC. Residents had between 6 and 8 sessions in each of their last 2 years of training; 2 residents were assigned for each half-day CPC session and each evaluated 2 or 3 patients under faculty-learner supervision.

Data Collection

The qualitative interviewers were independent of the study. The research team members did not see the transcripts until preparing this report in conjunction with the interviewers. Data were collected from faculty at 4 points: following the initial 6 months of training in the models; following training in mental health care in the CPC; following supervision of faculty training of residents; and 8 months following completion of training, during which time they independently taught residents.

Data were collected in a systematic way over 1 hour, beginning and continuing open-endedly for about 30 minutes and concluding with closed-ended inquiry to pin down details and to ask any pre-planned questions that had not been answered. The protocol that guided focus group interviews is available from the authors.

Audio recordings were made from each group, and a 500- to 1000-word report was written by the interviewers, which served as the basis of the present descriptive evaluation. The authors independently analyzed the data at each collection point and then came to the consensus that follows.

Results

Lectures/Didactic Training

The training sessions involved 2 parts: lectures and didactic material around interviewing, general system theory, and psychiatry diagnoses; and skills practice in interviewing and the mental health care models. The trainers and faculty met weekly for 4 hours, and the first 2 hours of these sessions were spent reviewing the background of what would become the mainstay of the teaching, the models for interviewing and mental health care (Table 2 and Table 3). These readings differed in content and style from the typical clinical readings that physicians use, and they required considerable outside time and preparation, beyond that anticipated by the trainees. Digging into these theoretical concepts was described as interesting and “refreshing,” but the trainees at first found the readings disconnected from their clinical work. Faculty trainees later recognized the importance of understanding the models as they prepared for their roles as teachers. All told, however, the trainees believed there was too much didactic material.

Receiving education on diagnosis and management of common psychiatric disorders from academic psychiatrists was appreciated, but the trainees also expressed the greatest frustrations about this part of the curriculum. They felt that the level of these sessions was not always appropriately gauged—ranging from too simplistic, as in medical school, to too detailed, especially around neurochemical and neurobiological mechanisms. Although they appreciated learning about advanced psychiatric illness and treatments (eg, electroconvulsive treatment, especially), they did not believe the information was necessary in primary care. Trainees were experienced primary care providers and were more interested in case-based education that could highlight the types of patients seen in their office every day. One trainee indicated that these sessions were lacking “the patient voice.” Abstract discussion of diagnoses and treatments made it challenging to apply this new knowledge to the trainees’ practices. Trainees also suggested trying to integrate this section of the training with the interviewing skills training to better highlight that interplay. The trainees believed that their understanding and familiarity with the diagnosis and management of mental disorders occurred primarily in later CPC training. The trainees recommended that all didactic material be reduced by half or more in future teaching.

Skills Practice

The patient-centered interviewing skills practice, which occurred in the second 2-hour period during the first 6 months, was lauded by the faculty trainees. It was considered the “most immediately relevant component” of this period of training. Because the trainees were experienced physicians when they began this project, they felt this part of training made the “…material more accessible to myself, more germane to what I do day in and day out.” The insight of modifying the interviewing techniques to connect with different patient personality types was particularly helpful. One trainee described an “aha moment” of “getting patients to open up in a way I had not been able to do before.” As time went on, the trainees felt empowered to adapt “the interviewing script” modestly to fit their already developed “rhythm and style with their patients.”

Wellness/Mentoring

The 2 trainees were at different stages of their careers, 1 early-career faculty and 1 mid-career faculty. This academic diversity within the small training group provided varied perspectives not only on the concepts presented and discussed, but also on a more personal level. In an otherwise hectic academic medicine environment, this group had a weekly chance to stop, “check in” with each other, and truly connect on a personal level. To be asked “about your week and actually mean it and want to hear the answer” is an unusual opportunity, one noted. It also offered time and support for purposeful self-reflection, which “often brought some emotions to the surface…at different times.” These connections were perhaps one of the most valuable parts of the experience. With burnout among physicians rampant,24 establishing these networks is invaluable. In addition to introspection and personal connections, there was a strong element of mentoring during these weekly meetings. The opportunity to meet in a small group with senior faculty was highly valued by the trainees.

Mental Health Care: Complex Patient Clinic

The faculty were eager, but very apprehensive, in beginning the second segment of training, where work shifted from lectures and practicing skills to mental health care training in the CPC. The trainees expressed anxiety about several areas. These included additional clinical workload, patient referral/selection, and transition of patient care back to the primary care provider. Of note, they did not particularly express worries about the care they would be providing, because a psychiatrist would be available to them on site. In reflection, after spending 4 months in the clinic, trainees noted “how important observing live interviews for evaluation/feedback was to their learning.” The CPC provided “learning in the moment on specific patients [which] was without question the most powerful teaching tool.” The support of the training faculty who were present at each clinic was invaluable. Whereas the earlier didactics given by psychiatrists were received by trainees with lukewarm enthusiasm, the point-of-care, case-by-case learning and feedback truly advanced the trainees’ knowledge, as well as skills, and improved their confidence in providing mental health care.

One of the tenets of the mental health care models is collaborative care.25 Recognizing this critical component of patient care, the CPC experience integrated a clinical social worker. The faculty noted the critical role she played in the patient care experience. They described her as “fabulous and awesome.” Her grasp of the health care system and community resources (particularly for an underserved population) was indispensable. Additionally, she was able to serve as a steady contact to follow patients through multiple visits and improve their feelings of continuity.

Teaching: Psychosocial Rotation

The first psychosocial teaching occurred after the interviewing skills and didactic experiences in the first 6 months. The trainees expressed great doubt about tackling this initial teaching experience. From residents challenging the need for interviewing and other aspects of “touchy-feely” teaching, to patients expressing raw emotions, the trainees lacked confidence in their ability to handle these moments. At this early stage of their training, one trainee said, “I feel like I am becoming a better interrogator, but I haven’t learned the skills to be a better healer yet.” Over time, this concern disappeared. As training evolved, the trainees began to thrive in their role as educator. At the final focus group, it was noted that “teaching has enhanced [my] confidence in the framework and in turn has made it easier to teach.”

Teaching: Complex Patient Clinic

This powerful teaching tool to train residents was the centerpiece of training. The faculty trainees had some hesitation about their role as teacher before it began. The faculty trainees were at different stages of their careers, and their confidence in their own teaching skills was not uniform. Importantly, the initial structure of the CPC, which included psychiatrists and senior faculty supervision, provided strong and continued support for the faculty trainees. Later work in the CPC as teacher, rather than trainee, further bolstered the faculty’s confidence in the treatment models. As confidence with their own skills grew, faculty noted that it became “easier to teach” as well. Faculty also recognized the unique opportunity that the CPC provided in directly observing a resident’s patient interaction. This allows them to “monitor progress, provide specific feedback, and address issues.” The time spent debriefing after each patient encounter was noted to be particularly important. When they became too busy to adequately provide this debriefing, changes to the schedule were made to accommodate it (follow-up visits were lengthened from 30 to 60 minutes). In addition to giving an opportunity to provide feedback, this extra time available for residents to interact with a patient—to utilize and practice the interviewing skills, for example—was quite valuable, independent of actual mental health care training. Finally, the faculty were able to create a “relaxed and comfortable” space in the CPC. Indeed, the faculty felt comfortable sharing some of their struggles and reflections on caring for a mental health patient population, and residents were able, in turn, to engage in some self-reflection and debriefing as well.

Discussion

Faculty trainees demonstrated a striking evolution as they progressed through this curriculum. At each of the 3 stages of training, they endorsed a broad range of feelings, from anxiety and uncertainty initially, to confidence and growth and appreciation later. They felt satisfied with having participated in the project and are engaged in exploring next steps.

Of note, these faculty members had some exposure to the skills models prior to starting the program because the residency program has integrated patient-centered interviewing into its program for many years. The faculty were supportive of the models prior to engaging in the curriculum, and they volunteered to participate. Similarly, the residents were familiar with the expectations as they went through the psychosocial rotation and the CPC. It is conceivable that the interviewing and mental health material may not be received as easily at an institution where the culture has had less exposure to such teaching.

While describing a faculty curriculum for mental health training is unique5 and the primary intent of this paper, we wanted to present its formative evaluation even though only 2 faculty trainees were involved. Simply put, the grant for this project supported only 2 trainees, and no more were required. Nevertheless, we propose that this only reported experience of medical faculty with mental health training is an important addition to the literature in mental health education. It will be a critical guide for others who choose the new direction of training medical faculty to teach mental health care.

As the research team looks to foster dissemination of the curriculum, it continues to be streamlined to highlight the components most useful and germane to learners. The early didactic readings on subjects such as general system theory were less engaging. (In later training of new medical faculty learners, the focus on theory and other didactics was reduced.) In contrast, the trainees clearly valued the interviewing skills experience (both learning and teaching). While the mental health curriculum and the CPC were associated with much greater anxiety in the trainees, with practical, respectful, and supervised teaching, they became confident and satisfied—as well as effective.6 Future teachers will benefit from slowly and understandingly addressing trainees’ personal issues, particularly during the initial phases of training.26 It appeared to us to be the key factor enabling the faculty to successfully learn and teach mental health care. Once they overcame their personal reactions to mental health material, they learned mental health skills just as they learn the more familiar physical disease material.

Conclusion

In a new direction in medical education, a curriculum for training medical faculty to teach mental health care is presented. Not only did prior research demonstrate that the faculty effectively trained residents, but we also demonstrated here that the training was acceptable to and valued by faculty. With mental health often an alien dimension of medicine, acceptability is especially important when we recommend disseminating the curriculum as a way to offset the national mental health care crisis.

Corresponding author: Robert C. Smith, 788 Service Road, B314 Clinical Center, East Lansing, MI 48824; smithrr@msu.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

Funding support: The authors are grateful for the generous support from the Health Resources and Services Administration (D58HP23259).

1. Smith R, Gardiner J, Luo Z, et al. Primary care physicians treat somatization. J Gen Int Med. 2009;24:829-832.

2. Smith RC, Lyles JS, Gardiner JC, et al. Primary care clinicians treat patients with medically unexplained symptoms—a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:671-677.

3. Smith RC, Lein C, Collins C, et al. Treating patients with medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:478-489.

4. Smith RC, Lyles JS, Mettler J, et al. The effectiveness of intensive training for residents in interviewing. A randomized, controlled study. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:118-126.

5. Smith R, Laird-Fick H, D’Mello D, et al. Addressing mental health issues in primary care: an initial curriculum for medical residents. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94:33-42.

6. Smith R, Laird-Fick H, Dwamena F, et al. Teaching residents mental health care. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101:2145-2155.

7. Cunningham PJ. Beyond parity: primary care physicians’ perspectives on access to mental health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28:w490-501.

8. US Department of Health and Human Services: Healthy People 2020: The Road Ahead. Washington, DC: US Governmant Printing Office; 2011.

9. US Department of Health and Human Services. Facing Addiction in America—The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2016.

10. US Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health and Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2000.

11. Hogan MF. The President’s New Freedom Commission: recommendations to transform mental health care in America. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:1467-1474.

12. Morrisey J, Thomas K, Ellis A, et al. Development of a New Method for Designation of Mental Health Professional Shortage Areas. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2007.

13. US Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: a Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Dept. of Health and Human Services; 1999.

14. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:629-640.

15. Kern DE, Thomas PA, Hughes MT. Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six-Step Approach. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2009.

16. Fortin 6th AH, Dwamena F, Frankel R, et al. Smith’s Patient-Centered Interviewing: An Evidence-Based Method. 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2018.

17. Smith R, D’Mello D, Osborn G, et al. Essentials of Psychiatry in Primary Care: Behavioral Health in the Medical Setting. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2019 .

18. Smith R, Fortin AH 6th, Dwamena F, et al. An evidence-based patient-centered method makes the biopsychosocial model scientific. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;90:265-270.

19. Smith R, Dwamena F, Grover M, et al. Behaviorally-defined patient-centered communication—a narrative review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;26:185-191.

20. Smith RC, Dwamena FC. Classification and diagnosis of patients with medically unexplained symptoms. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:685-691.

21. Schneider RK, Levenson JL. Psychiatry Essentials for Primary Care. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Physicians; 2008.

22. Dwamena F, Laird-Fick H, Freilich L, et al. Behavioral health problems in medical patients. J Clin Outcomes Manage. 2014;21:497-505.

23. Vidyo (Hackensack, NJ). http://www.vidyo.com/products/use/. 2014.

24. Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:195-205.

25. Huffman JC, Niazi SK, Rundell JR, et al. Essential articles on collaborative care models for the treatment of psychiatric disorders in medical settings: a publication by the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine Research and Evidence-Based Practice Committee. Psychosomatics. 2014;55:109-122.

26. Smith RC, Dwamena FC, Fortin AH 6th. Teaching personal awareness. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:201-207.

1. Smith R, Gardiner J, Luo Z, et al. Primary care physicians treat somatization. J Gen Int Med. 2009;24:829-832.

2. Smith RC, Lyles JS, Gardiner JC, et al. Primary care clinicians treat patients with medically unexplained symptoms—a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:671-677.

3. Smith RC, Lein C, Collins C, et al. Treating patients with medically unexplained symptoms in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:478-489.

4. Smith RC, Lyles JS, Mettler J, et al. The effectiveness of intensive training for residents in interviewing. A randomized, controlled study. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:118-126.

5. Smith R, Laird-Fick H, D’Mello D, et al. Addressing mental health issues in primary care: an initial curriculum for medical residents. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94:33-42.

6. Smith R, Laird-Fick H, Dwamena F, et al. Teaching residents mental health care. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101:2145-2155.

7. Cunningham PJ. Beyond parity: primary care physicians’ perspectives on access to mental health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28:w490-501.

8. US Department of Health and Human Services: Healthy People 2020: The Road Ahead. Washington, DC: US Governmant Printing Office; 2011.

9. US Department of Health and Human Services. Facing Addiction in America—The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2016.

10. US Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health and Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2000.

11. Hogan MF. The President’s New Freedom Commission: recommendations to transform mental health care in America. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:1467-1474.

12. Morrisey J, Thomas K, Ellis A, et al. Development of a New Method for Designation of Mental Health Professional Shortage Areas. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2007.

13. US Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: a Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Dept. of Health and Human Services; 1999.

14. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:629-640.

15. Kern DE, Thomas PA, Hughes MT. Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six-Step Approach. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2009.

16. Fortin 6th AH, Dwamena F, Frankel R, et al. Smith’s Patient-Centered Interviewing: An Evidence-Based Method. 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2018.

17. Smith R, D’Mello D, Osborn G, et al. Essentials of Psychiatry in Primary Care: Behavioral Health in the Medical Setting. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2019 .

18. Smith R, Fortin AH 6th, Dwamena F, et al. An evidence-based patient-centered method makes the biopsychosocial model scientific. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;90:265-270.

19. Smith R, Dwamena F, Grover M, et al. Behaviorally-defined patient-centered communication—a narrative review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;26:185-191.

20. Smith RC, Dwamena FC. Classification and diagnosis of patients with medically unexplained symptoms. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:685-691.

21. Schneider RK, Levenson JL. Psychiatry Essentials for Primary Care. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Physicians; 2008.

22. Dwamena F, Laird-Fick H, Freilich L, et al. Behavioral health problems in medical patients. J Clin Outcomes Manage. 2014;21:497-505.

23. Vidyo (Hackensack, NJ). http://www.vidyo.com/products/use/. 2014.

24. Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:195-205.

25. Huffman JC, Niazi SK, Rundell JR, et al. Essential articles on collaborative care models for the treatment of psychiatric disorders in medical settings: a publication by the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine Research and Evidence-Based Practice Committee. Psychosomatics. 2014;55:109-122.

26. Smith RC, Dwamena FC, Fortin AH 6th. Teaching personal awareness. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:201-207.