User login

Options and outcomes for uterine preservation at the time of prolapse surgery

CASE Patient desires prolapse repair

A 65-year-old postmenopausal patient (G3P3) presents to your office with symptoms of a vaginal bulge for more than 1 year. She has no urinary incontinence symptoms and no bowel dysfunction symptoms. On examination, you diagnose stage 2 uterovaginal prolapse with both anterior and apical defects. The patient declines expectant and pessary management and desires surgery, but she states that she feels her uterus “is important for me to keep, as my babies grew in there and it is part of me.” She denies any family or personal history of breast, endometrial, or ovarian cancer and has no history of abnormal cervical cancer screening or postmenopausal bleeding. What are the options for this patient?

Who is the appropriate hysteropexy patient, and how do we counsel her?

Uterine prolapse is the third leading cause of benign hysterectomy, with approximately 70,000 procedures performed each year in the United States. It has long been acknowledged that the uterus is a passive bystander to the prolapse process,1 but modern practice often involves a hysterectomy as part of addressing apical prolapse. However, more and more uterine-preserving surgeries are being performed, with one study showing an increase from 1.8% to 5% from 2002 and 2012.2

When presented with the option to keep or remove their uterus during the time of prolapse surgery, 36% of patients indicated that they would prefer to keep their uterus with similar outcomes while 21% would still prefer uterine preservation even if outcomes were inferior compared with hysterectomy.3 Another study showed that 60% of patients would decline concurrent hysterectomy if there were equal surgical outcomes,4 and popular platforms, such as Health magazine (www.health.com) and AARP magazine (www.aarp.org), have listed benign hysterectomy as a “top surgery to avoid.”

Patients desire uterine preservation for many reasons, including concerns about sexual function and pleasure, the uterus being important to their sense of identity or womanhood, and concerns around menopausal symptoms. Early patient counseling and discussion of surgical goals can help clinicians fully understand a patient’s thoughts toward uterine preservation. Women who identified their uterus as important to their sense of self had a 28.2-times chance of preferring uterine preservation.3 Frequently, concerns about menopausal symptoms are more directly related to hormones and ovary removal, not uterus removal, but clinicians should be careful to also counsel patients on the increased risk of menopause in the 5 years after hysterectomy, even with ovarian preservation.5

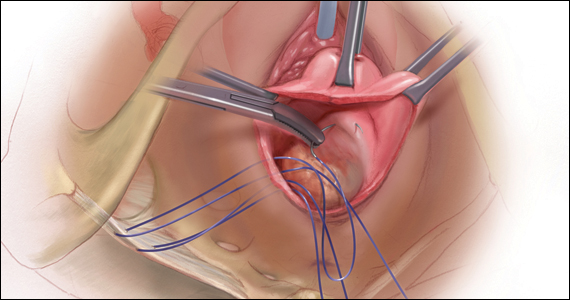

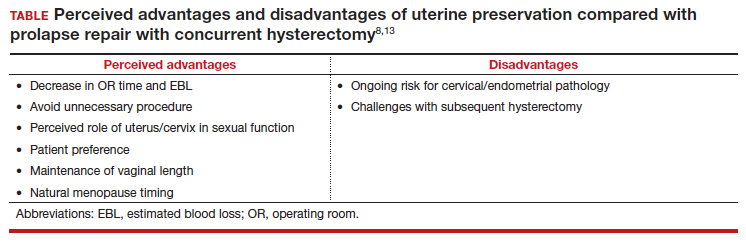

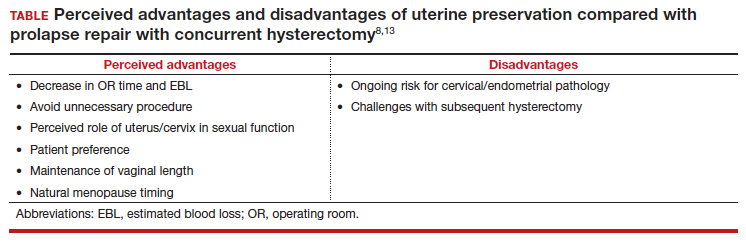

There are some patients for whom experts do not recommend uterine preservation.6 Patients with an increased risk of cervical or endometrial pathology should be counseled on the benefits of hysterectomy. Additionally, patients who have abnormal uterine bleeding from benign pathology should consider hysterectomy to treat these issues and avoid future workups (TABLE). For postmenopausal patients with recent postmenopausal bleeding, we encourage hysterectomy. A study of patients undergoing hysterectomy at the time of prolapse repair found a rate of 13% unanticipated endometrial pathology with postmenopausal bleeding and negative preoperative workup.7

At this time, a majority of clinicians consider the desire for future fertility to be a relative contraindication to surgical prolapse repair and advise conservative management with pessary until childbearing is complete. This is reasonable, given the paucity of safety data in subsequent pregnancies as well as the lack of prolapse outcomes after those pregnancies.8,9 Lastly, cervical elongation is considered a relative contraindication, as it represents a risk for surgical failure.10,11 This may be counteracted with trachelectomy at the time of hysteropexy or surgeries such as the Manchester repair, which involve a trachelectomy routinely,12 but currently there is no strong evidence for this as routine practice.

Continue to: Uterine preservation surgical techniques and outcomes...

Uterine preservation surgical techniques and outcomes

Le Fort colpocleisis

First described in 1840 by Neugebauer of Poland and later by Le Fort in Paris in 1877, the Le Fort colpocleisis repair technique remains the most reliable prolapse surgery to date.14 The uterus is left in place while the vagina is narrowed and shortened. It typically also is performed with a levator plication to reduce the genital hiatus.

This procedure is quick and effective, with a 90% to 95% success rate. If necessary, it can be performed under local or regional anesthesia, making it a good option for medically frail patients. It is not an option for everyone, however, as penetrative intercourse is no longer an option after surgery. Studies suggest an approximately 13% dissatisfaction rate after the procedure, with most of that coming from postoperative urinary symptoms, such as urgency or stress incontinence,15 and some studies show a dissatisfaction rate as low as 0% in a well-counseled patient population.16,17

Vaginal native tissue hysteropexy

Many patients who elect for uterine preservation at the time of prolapse surgery are “minimalists,” meaning that a vaginal native tissue procedure appeals to them due to the lack of abdominal incisions, decreased operating room time, and lack of permanent graft materials.

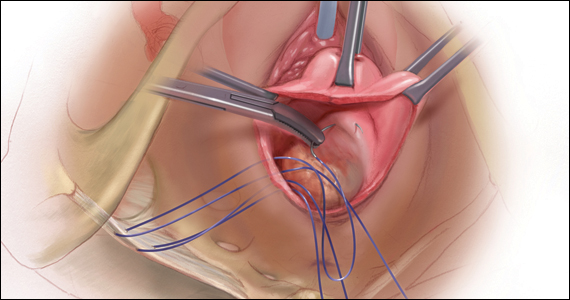

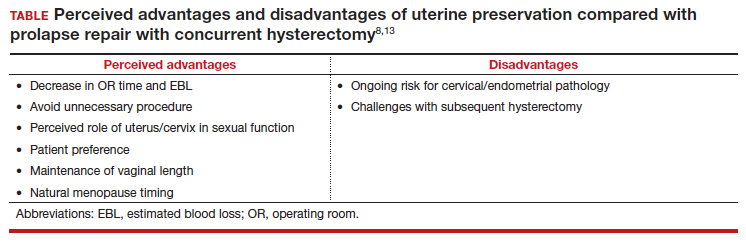

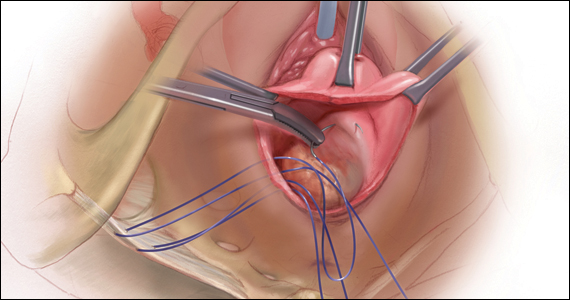

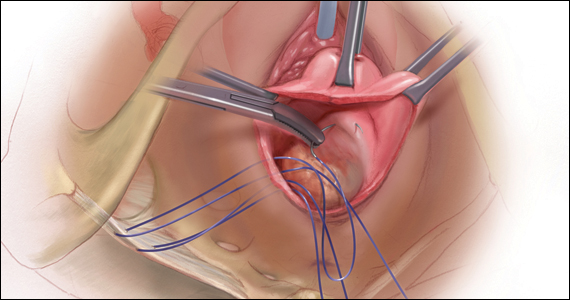

Of all the hysteropexy procedures, sacrospinous hysteropexy (SSHP) has the most robust data available. The approach to SSHP can be tailored to the patient’s anatomy and it is performed in a manner similar to posthysterectomy sacrospinous ligament fixation. The traditional posterior approach can be used with predominantly posterior prolapse, while an apical approach through a semilunar paracervical incision can be used for predominantly apical prolapse. Expert surgeons agree that one key to success is anchoring the suspension sutures through the cervical stroma, not just the vaginal epithelium.

Researchers in the Netherlands published the 5-year outcomes of a randomized trial that compared SSHP with vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.18 Their data showed no difference between groups in composite failure, reoperation rates, quality of life measures, and postoperative sexual function. Adverse events were very similar to those reported for posthysterectomy sacrospinous ligament fixation, including 15% transient buttock pain. Of note, the same authors explored risk factors for recurrence after SSHP and found that higher body mass index, smoking, and a large point Ba measurement were risk factors for prolapse recurrence.19

A randomized, controlled trial in the United Kingdom (the VUE trial) compared vaginal hysterectomy with apical suspension to uterine preservation with a variety of apical suspension techniques, mostly SSHP, and demonstrated no significant differences in outcomes.20 Overall, SSHP is an excellent option for many patients interested in uterine preservation.

Uterosacral ligament hysteropexy (USHP), when performed vaginally, is very similar to uterosacral ligament suspension at the time of vaginal hysterectomy, with entry into the peritoneal cavity through a posterior colpotomy. The uterosacral ligaments are grasped and delayed absorbable suture placed through the ligaments and anchored into the posterior cervical stroma. Given the maintenance of the normal axis of the vagina, USHP is a good technique for patients with isolated apical defects. Unfortunately, the least amount of quality data is available for USHP at this time. Currently, evidence suggests that complications are rare and that the procedure may offer acceptable anatomic and symptomatic outcomes.21 Some surgeons approach the uterosacral suspension laparoscopically, which also has mixed results in the literature, with failure rates between 8% and 27% and few robust studies.22–24

The Manchester-Fothergill operation, currently not common in the United States but popular in Europe, primarily is considered a treatment for cervical elongation when the uterosacral ligaments are intact. In this procedure, trachelectomy is performed and the uterosacral ligaments are plicated to the uterine body. Sturmdorf sutures are frequently placed to close off the endometrial canal, which can lead to hematometra and other complications of cervical stenosis. Previous unmatched studies have shown similar outcomes with the Manchester procedure compared with vaginal hysterectomy.25,26

The largest study currently available is a registry study from Denmark, with matched cohort populations, that compared the Manchester procedure, SSHP, and total vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.27 This study indicated less morbidity related to the Manchester procedure, decreased anterior recurrence compared with SSHP, and a 7% reoperation rate.27 The same authors also established better cost-effectiveness with the Manchester procedure as opposed to vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.28

Continue to: Vaginal mesh hysteropexy...

Vaginal mesh hysteropexy

Hysteropexy using vaginal mesh is limited in the United States given the removal of vaginal mesh kits from the market by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2019. However, a Pelvic Floor Disorders Network randomized trial compared vaginal mesh hysteropexy using the Uphold LITE transvaginal mesh support system (Boston Scientific) and vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.29 At 5 years, mesh hysteropexy had fewer failures than hysterectomy (37% vs 54%) and there was no difference in retreatment (9% vs 13%). The authors noted an 8% mesh exposure rate in the mesh hysteropexy group but 12% granulation tissue and 21% suture exposure rate in the hysterectomy group.29

While vaginal mesh hysteropexy was effective in the treatment of apical prolapse, the elevated mesh exposure rate and postoperative complications ultimately led to its removal from the market.

Sacrohysteropexy

Lastly, prolapse surgery with uterine preservation may be accomplished abdominally, most commonly laparoscopically with or without robotic assistance.

Sacrohysteropexy (SHP) involves the attachment of permanent synthetic mesh posteriorly to the posterior vagina and cervix with or without the additional placement of mesh to the anterior vagina and cervix. When the anterior mesh is placed, the arms are typically routed through the broad ligament bilaterally and joined with the posterior mesh for attachment to the anterior longitudinal ligament, overlying the sacrum.

Proponents of this technique endorse the use of mesh to augment already failing native tissues and propose similarities to the durability of sacrocolpopexy. While no randomized controlled trials have compared hysterectomy with sacrocolpopexy or supracervical hysterectomy with sacrocolpopexy to sacrohysteropexy, a meta-analysis suggests that sacrohysteropexy may have a decreased risk of mesh exposure but a higher reoperation rate with lower anatomic success.9 Randomized trials that compared abdominal sacrohysteropexy with vaginal hysterectomy and suspension indicate that apical support may be improved with sacrohysteropexy,30 but reoperations, postoperative pain and disability, and urinary dysfunction was higher with SHP.31,32

What further research is needed?

With the increasing patient and clinician interest in uterine preservation, more research is needed to improve patient counseling and surgical planning. Much of the current research compares hysteropexy outcomes with those of traditional prolapse repairs with hysterectomy, with only a few randomized trials. We are lacking robust, prospective comparison studies between hysteropexy methods, especially vaginal native tissue techniques, long-term follow-up on the prevalence of uterine or cervical pathology after hysteropexy, and pregnancy or postpartum outcomes following uterine preservation surgery.

Currently, work is underway to validate and test the effectiveness of a questionnaire to evaluate the uterus’s importance to the patient seeking prolapse surgery in order to optimize counseling. The VUE trial, which randomizes women to vaginal hysterectomy with suspension versus various prolapse surgeries with uterine preservation, is continuing its 6-year follow-up.20 In the Netherlands, an ongoing randomized, controlled trial (the SAM trial) is comparing the Manchester procedure with sacrospinous hysteropexy and will follow patients up to 24 months.33 Fortunately, both of these trials are rigorously assessing both objective and patient-centered outcomes.

CASE Counseling helps the patient weigh surgical options

After thorough review of her surgical options, the patient elects for a uterine-preserving prolapse repair. She would like to have the most minimally invasive procedure and does not want any permanent mesh used. You suggest, and she agrees to, a sacrospinous ligament hysteropexy, as it is the current technique with the most robust data. ●

- DeLancey JO. Anatomic aspects of vaginal eversion after hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(6 pt 1):1717-1724; discussion 1724-1728. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(92)91562-o.

- Madsen AM, Raker C, Sung VW. Trends in hysteropexy and apical support for uterovaginal prolapse in the United States from 2002 to 2012. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2017;23:365-371. doi:10.1097/SPV.0000000000000426.

- Korbly NB, Kassis NC, Good MM, et al. Patient preferences for uterine preservation and hysterectomy in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:470.e16. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.08.003.

- Frick AC, Barber MD, Paraiso MF, et al. Attitudes toward hysterectomy in women undergoing evaluation for uterovaginal prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19:103-109. doi:10.1097/SPV.0b013e31827d8667.

- Farquhar CM, Sadler L, Harvey SA, et al. The association of hysterectomy and menopause: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2005;112:956-962. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00696.x

- Gutman R, Maher C. Uterine-preserving POP surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1803-1813. doi:10.1007/s00192-0132171-2.

- Frick AC, Walters MD, Larkin KS, et al. Risk of unanticipated abnormal gynecologic pathology at the time of hysterectomy for uterovaginal prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:507. e1-4. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.077.

- Meriwether KV, Balk EM, Antosh DD, et al. Uterine-preserving surgeries for the repair of pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review with meta-analysis and clinical practice guidelines. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:505-522. doi:10.1007/s00192-01903876-2.

- Meriwether KV, Antosh DD, Olivera CK, et al. Uterine preservation vs hysterectomy in pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a systematic review with meta-analysis and clinical practice guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:129-146. e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2018.01.018.

- Lin TY, Su TH, Wang YL, et al. Risk factors for failure of transvaginal sacrospinous uterine suspension in the treatment of uterovaginal prolapse. J Formos Med Assoc. 2005;104:249-253.

- Hyakutake MT, Cundiff GW, Geoffrion R. Cervical elongation following sacrospinous hysteropexy: a case series. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:851-854. doi:10.1007/s00192-013-2258-9.

- Thys SD, Coolen AL, Martens IR, et al. A comparison of long-term outcome between Manchester Fothergill and vaginal hysterectomy as treatment for uterine descent. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:1171-1178. doi:10.1007/s00192-011-1422-3.

- Ridgeway BM, Meriwether KV. Uterine preservation in pelvic organ prolapse surgery. In: Walters & Karram Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery. 5th ed. Elsevier, Inc; 2022:358-373.

- FitzGerald MP, Richter HE, Siddique S, et al; for the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Colpocleisis: a review. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:261-271. doi:10.1007/s00192005-1339-9.

- Winkelman WD, Haviland MJ, Elkadry EA. Long-term pelvic f loor symptoms, recurrence, satisfaction, and regret following colpocleisis. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26:558562. doi:10.1097/SPV.000000000000602.

- Lu M, Zeng W, Ju R, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes, recurrence, satisfaction, and regret after total colpocleisis with concomitant vaginal hysterectomy: a retrospective single-center study. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27(4):e510-e515. doi:10.1097/SPV.0000000000000900.

- Wang X, Chen Y, Hua K. Pelvic symptoms, body image, and regret after LeFort colpocleisis: a long-term follow-up. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:415-419. doi:10.1016/j. jmig.2016.12.015.

- Schulten SFM, Detollenaere RJ, Stekelenburg J, et al. Sacrospinous hysteropexy versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension in women with uterine prolapse stage 2 or higher: observational followup of a multicentre randomised trial. BMJ. 2019;366:I5149. doi:10.1136/bmj.l5149.

- Schulten SF, Detollenaere RJ, IntHout J, et al. Risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse recurrence after sacrospinous hysteropexy or vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227:252.e1252.e9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.04.017.

- Hemming C, Constable L, Goulao B, et al. Surgical interventions for uterine prolapse and for vault prolapse: the two VUE RCTs. Health Technol Assess. 2020;24:1-220. doi:10.3310/hta24130.

- Romanzi LJ, Tyagi R. Hysteropexy compared to hysterectomy for uterine prolapse surgery: does durability differ? Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:625-631. doi:10.1007/s00192-011-1635-5.

- Rosen DM, Shukla A, Cario GM, et al. Is hysterectomy necessary for laparoscopic pelvic floor repair? A prospective study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:729-734. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2008.08.010.

- Bedford ND, Seman EI, O’Shea RT, et al. Effect of uterine preservation on outcome of laparoscopic uterosacral suspension. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(2):172-177. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2012.10.014.

- Diwan A, Rardin CR, Strohsnitter WC, et al. Laparoscopic uterosacral ligament uterine suspension compared with vaginal hysterectomy with vaginal vault suspension for uterovaginal prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:79-83. doi:10.1007/s00192-005-1346-x.

- de Boer TA, Milani AL, Kluivers KB, et al. The effectiveness of surgical correction of uterine prolapse: cervical amputation with uterosacral ligament plication (modified Manchester) versus vaginal hysterectomy with high uterosacral ligament plication. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:13131319. doi:10.1007/s00192-009-0945-3.

- Thomas AG, Brodman ML, Dottino PR, et al. Manchester procedure vs. vaginal hysterectomy for uterine prolapse. A comparison. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:299-304.

- Husby KR, Larsen MD, Lose G, et al. Surgical treatment of primary uterine prolapse: a comparison of vaginal native tissue surgical techniques. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:18871893. doi:10.1007/s00192-019-03950-9.

- Husby KR, Tolstrup CK, Lose G, et al. Manchester-Fothergill procedure versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension: an activity-based costing analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:1161-1171. doi:10.1007/s00192-0183575-9.

- Nager CW, Visco AG, Richter HE, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Effect of sacrospinous hysteropexy with graft vs vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension on treatment failure in women with uterovaginal prolapse: 5-year results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:153.e1-153.e31. doi:10.1016/j. ajog.2021.03.012.

- Rahmanou P, Price N, Jackson SR. Laparoscopic hysteropexy versus vaginal hysterectomy for the treatment of uterovaginal prolapse: a prospective randomized pilot study. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:1687-1694. doi:10.1007/s00192-0152761-2.

- Roovers JP, van der Vaart CH, van der Bom JG, et al. A randomised controlled trial comparing abdominal and vaginal prolapse surgery: effects on urogenital function. BJOG. 2004;111:50-56. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00001.x.

- Roovers JP, van der Bom JG, van der Vaart CH, et al. A randomized comparison of post-operative pain, quality of life, and physical performance during the first 6 weeks after abdominal or vaginal surgical correction of descensus uteri. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24:334-340. doi:10.1002/nau.20104.

- Schulten SFM, Enklaar RA, Kluivers KB, et al. Evaluation of two vaginal, uterus sparing operations for pelvic organ prolapse: modified Manchester operation (MM) and sacrospinous hysteropexy (SSH), a study protocol for a multicentre randomized non-inferiority trial (the SAM study). BMC Womens Health. 20192;19:49. doi:10.1186/ s12905-019-0749-7.

CASE Patient desires prolapse repair

A 65-year-old postmenopausal patient (G3P3) presents to your office with symptoms of a vaginal bulge for more than 1 year. She has no urinary incontinence symptoms and no bowel dysfunction symptoms. On examination, you diagnose stage 2 uterovaginal prolapse with both anterior and apical defects. The patient declines expectant and pessary management and desires surgery, but she states that she feels her uterus “is important for me to keep, as my babies grew in there and it is part of me.” She denies any family or personal history of breast, endometrial, or ovarian cancer and has no history of abnormal cervical cancer screening or postmenopausal bleeding. What are the options for this patient?

Who is the appropriate hysteropexy patient, and how do we counsel her?

Uterine prolapse is the third leading cause of benign hysterectomy, with approximately 70,000 procedures performed each year in the United States. It has long been acknowledged that the uterus is a passive bystander to the prolapse process,1 but modern practice often involves a hysterectomy as part of addressing apical prolapse. However, more and more uterine-preserving surgeries are being performed, with one study showing an increase from 1.8% to 5% from 2002 and 2012.2

When presented with the option to keep or remove their uterus during the time of prolapse surgery, 36% of patients indicated that they would prefer to keep their uterus with similar outcomes while 21% would still prefer uterine preservation even if outcomes were inferior compared with hysterectomy.3 Another study showed that 60% of patients would decline concurrent hysterectomy if there were equal surgical outcomes,4 and popular platforms, such as Health magazine (www.health.com) and AARP magazine (www.aarp.org), have listed benign hysterectomy as a “top surgery to avoid.”

Patients desire uterine preservation for many reasons, including concerns about sexual function and pleasure, the uterus being important to their sense of identity or womanhood, and concerns around menopausal symptoms. Early patient counseling and discussion of surgical goals can help clinicians fully understand a patient’s thoughts toward uterine preservation. Women who identified their uterus as important to their sense of self had a 28.2-times chance of preferring uterine preservation.3 Frequently, concerns about menopausal symptoms are more directly related to hormones and ovary removal, not uterus removal, but clinicians should be careful to also counsel patients on the increased risk of menopause in the 5 years after hysterectomy, even with ovarian preservation.5

There are some patients for whom experts do not recommend uterine preservation.6 Patients with an increased risk of cervical or endometrial pathology should be counseled on the benefits of hysterectomy. Additionally, patients who have abnormal uterine bleeding from benign pathology should consider hysterectomy to treat these issues and avoid future workups (TABLE). For postmenopausal patients with recent postmenopausal bleeding, we encourage hysterectomy. A study of patients undergoing hysterectomy at the time of prolapse repair found a rate of 13% unanticipated endometrial pathology with postmenopausal bleeding and negative preoperative workup.7

At this time, a majority of clinicians consider the desire for future fertility to be a relative contraindication to surgical prolapse repair and advise conservative management with pessary until childbearing is complete. This is reasonable, given the paucity of safety data in subsequent pregnancies as well as the lack of prolapse outcomes after those pregnancies.8,9 Lastly, cervical elongation is considered a relative contraindication, as it represents a risk for surgical failure.10,11 This may be counteracted with trachelectomy at the time of hysteropexy or surgeries such as the Manchester repair, which involve a trachelectomy routinely,12 but currently there is no strong evidence for this as routine practice.

Continue to: Uterine preservation surgical techniques and outcomes...

Uterine preservation surgical techniques and outcomes

Le Fort colpocleisis

First described in 1840 by Neugebauer of Poland and later by Le Fort in Paris in 1877, the Le Fort colpocleisis repair technique remains the most reliable prolapse surgery to date.14 The uterus is left in place while the vagina is narrowed and shortened. It typically also is performed with a levator plication to reduce the genital hiatus.

This procedure is quick and effective, with a 90% to 95% success rate. If necessary, it can be performed under local or regional anesthesia, making it a good option for medically frail patients. It is not an option for everyone, however, as penetrative intercourse is no longer an option after surgery. Studies suggest an approximately 13% dissatisfaction rate after the procedure, with most of that coming from postoperative urinary symptoms, such as urgency or stress incontinence,15 and some studies show a dissatisfaction rate as low as 0% in a well-counseled patient population.16,17

Vaginal native tissue hysteropexy

Many patients who elect for uterine preservation at the time of prolapse surgery are “minimalists,” meaning that a vaginal native tissue procedure appeals to them due to the lack of abdominal incisions, decreased operating room time, and lack of permanent graft materials.

Of all the hysteropexy procedures, sacrospinous hysteropexy (SSHP) has the most robust data available. The approach to SSHP can be tailored to the patient’s anatomy and it is performed in a manner similar to posthysterectomy sacrospinous ligament fixation. The traditional posterior approach can be used with predominantly posterior prolapse, while an apical approach through a semilunar paracervical incision can be used for predominantly apical prolapse. Expert surgeons agree that one key to success is anchoring the suspension sutures through the cervical stroma, not just the vaginal epithelium.

Researchers in the Netherlands published the 5-year outcomes of a randomized trial that compared SSHP with vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.18 Their data showed no difference between groups in composite failure, reoperation rates, quality of life measures, and postoperative sexual function. Adverse events were very similar to those reported for posthysterectomy sacrospinous ligament fixation, including 15% transient buttock pain. Of note, the same authors explored risk factors for recurrence after SSHP and found that higher body mass index, smoking, and a large point Ba measurement were risk factors for prolapse recurrence.19

A randomized, controlled trial in the United Kingdom (the VUE trial) compared vaginal hysterectomy with apical suspension to uterine preservation with a variety of apical suspension techniques, mostly SSHP, and demonstrated no significant differences in outcomes.20 Overall, SSHP is an excellent option for many patients interested in uterine preservation.

Uterosacral ligament hysteropexy (USHP), when performed vaginally, is very similar to uterosacral ligament suspension at the time of vaginal hysterectomy, with entry into the peritoneal cavity through a posterior colpotomy. The uterosacral ligaments are grasped and delayed absorbable suture placed through the ligaments and anchored into the posterior cervical stroma. Given the maintenance of the normal axis of the vagina, USHP is a good technique for patients with isolated apical defects. Unfortunately, the least amount of quality data is available for USHP at this time. Currently, evidence suggests that complications are rare and that the procedure may offer acceptable anatomic and symptomatic outcomes.21 Some surgeons approach the uterosacral suspension laparoscopically, which also has mixed results in the literature, with failure rates between 8% and 27% and few robust studies.22–24

The Manchester-Fothergill operation, currently not common in the United States but popular in Europe, primarily is considered a treatment for cervical elongation when the uterosacral ligaments are intact. In this procedure, trachelectomy is performed and the uterosacral ligaments are plicated to the uterine body. Sturmdorf sutures are frequently placed to close off the endometrial canal, which can lead to hematometra and other complications of cervical stenosis. Previous unmatched studies have shown similar outcomes with the Manchester procedure compared with vaginal hysterectomy.25,26

The largest study currently available is a registry study from Denmark, with matched cohort populations, that compared the Manchester procedure, SSHP, and total vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.27 This study indicated less morbidity related to the Manchester procedure, decreased anterior recurrence compared with SSHP, and a 7% reoperation rate.27 The same authors also established better cost-effectiveness with the Manchester procedure as opposed to vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.28

Continue to: Vaginal mesh hysteropexy...

Vaginal mesh hysteropexy

Hysteropexy using vaginal mesh is limited in the United States given the removal of vaginal mesh kits from the market by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2019. However, a Pelvic Floor Disorders Network randomized trial compared vaginal mesh hysteropexy using the Uphold LITE transvaginal mesh support system (Boston Scientific) and vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.29 At 5 years, mesh hysteropexy had fewer failures than hysterectomy (37% vs 54%) and there was no difference in retreatment (9% vs 13%). The authors noted an 8% mesh exposure rate in the mesh hysteropexy group but 12% granulation tissue and 21% suture exposure rate in the hysterectomy group.29

While vaginal mesh hysteropexy was effective in the treatment of apical prolapse, the elevated mesh exposure rate and postoperative complications ultimately led to its removal from the market.

Sacrohysteropexy

Lastly, prolapse surgery with uterine preservation may be accomplished abdominally, most commonly laparoscopically with or without robotic assistance.

Sacrohysteropexy (SHP) involves the attachment of permanent synthetic mesh posteriorly to the posterior vagina and cervix with or without the additional placement of mesh to the anterior vagina and cervix. When the anterior mesh is placed, the arms are typically routed through the broad ligament bilaterally and joined with the posterior mesh for attachment to the anterior longitudinal ligament, overlying the sacrum.

Proponents of this technique endorse the use of mesh to augment already failing native tissues and propose similarities to the durability of sacrocolpopexy. While no randomized controlled trials have compared hysterectomy with sacrocolpopexy or supracervical hysterectomy with sacrocolpopexy to sacrohysteropexy, a meta-analysis suggests that sacrohysteropexy may have a decreased risk of mesh exposure but a higher reoperation rate with lower anatomic success.9 Randomized trials that compared abdominal sacrohysteropexy with vaginal hysterectomy and suspension indicate that apical support may be improved with sacrohysteropexy,30 but reoperations, postoperative pain and disability, and urinary dysfunction was higher with SHP.31,32

What further research is needed?

With the increasing patient and clinician interest in uterine preservation, more research is needed to improve patient counseling and surgical planning. Much of the current research compares hysteropexy outcomes with those of traditional prolapse repairs with hysterectomy, with only a few randomized trials. We are lacking robust, prospective comparison studies between hysteropexy methods, especially vaginal native tissue techniques, long-term follow-up on the prevalence of uterine or cervical pathology after hysteropexy, and pregnancy or postpartum outcomes following uterine preservation surgery.

Currently, work is underway to validate and test the effectiveness of a questionnaire to evaluate the uterus’s importance to the patient seeking prolapse surgery in order to optimize counseling. The VUE trial, which randomizes women to vaginal hysterectomy with suspension versus various prolapse surgeries with uterine preservation, is continuing its 6-year follow-up.20 In the Netherlands, an ongoing randomized, controlled trial (the SAM trial) is comparing the Manchester procedure with sacrospinous hysteropexy and will follow patients up to 24 months.33 Fortunately, both of these trials are rigorously assessing both objective and patient-centered outcomes.

CASE Counseling helps the patient weigh surgical options

After thorough review of her surgical options, the patient elects for a uterine-preserving prolapse repair. She would like to have the most minimally invasive procedure and does not want any permanent mesh used. You suggest, and she agrees to, a sacrospinous ligament hysteropexy, as it is the current technique with the most robust data. ●

CASE Patient desires prolapse repair

A 65-year-old postmenopausal patient (G3P3) presents to your office with symptoms of a vaginal bulge for more than 1 year. She has no urinary incontinence symptoms and no bowel dysfunction symptoms. On examination, you diagnose stage 2 uterovaginal prolapse with both anterior and apical defects. The patient declines expectant and pessary management and desires surgery, but she states that she feels her uterus “is important for me to keep, as my babies grew in there and it is part of me.” She denies any family or personal history of breast, endometrial, or ovarian cancer and has no history of abnormal cervical cancer screening or postmenopausal bleeding. What are the options for this patient?

Who is the appropriate hysteropexy patient, and how do we counsel her?

Uterine prolapse is the third leading cause of benign hysterectomy, with approximately 70,000 procedures performed each year in the United States. It has long been acknowledged that the uterus is a passive bystander to the prolapse process,1 but modern practice often involves a hysterectomy as part of addressing apical prolapse. However, more and more uterine-preserving surgeries are being performed, with one study showing an increase from 1.8% to 5% from 2002 and 2012.2

When presented with the option to keep or remove their uterus during the time of prolapse surgery, 36% of patients indicated that they would prefer to keep their uterus with similar outcomes while 21% would still prefer uterine preservation even if outcomes were inferior compared with hysterectomy.3 Another study showed that 60% of patients would decline concurrent hysterectomy if there were equal surgical outcomes,4 and popular platforms, such as Health magazine (www.health.com) and AARP magazine (www.aarp.org), have listed benign hysterectomy as a “top surgery to avoid.”

Patients desire uterine preservation for many reasons, including concerns about sexual function and pleasure, the uterus being important to their sense of identity or womanhood, and concerns around menopausal symptoms. Early patient counseling and discussion of surgical goals can help clinicians fully understand a patient’s thoughts toward uterine preservation. Women who identified their uterus as important to their sense of self had a 28.2-times chance of preferring uterine preservation.3 Frequently, concerns about menopausal symptoms are more directly related to hormones and ovary removal, not uterus removal, but clinicians should be careful to also counsel patients on the increased risk of menopause in the 5 years after hysterectomy, even with ovarian preservation.5

There are some patients for whom experts do not recommend uterine preservation.6 Patients with an increased risk of cervical or endometrial pathology should be counseled on the benefits of hysterectomy. Additionally, patients who have abnormal uterine bleeding from benign pathology should consider hysterectomy to treat these issues and avoid future workups (TABLE). For postmenopausal patients with recent postmenopausal bleeding, we encourage hysterectomy. A study of patients undergoing hysterectomy at the time of prolapse repair found a rate of 13% unanticipated endometrial pathology with postmenopausal bleeding and negative preoperative workup.7

At this time, a majority of clinicians consider the desire for future fertility to be a relative contraindication to surgical prolapse repair and advise conservative management with pessary until childbearing is complete. This is reasonable, given the paucity of safety data in subsequent pregnancies as well as the lack of prolapse outcomes after those pregnancies.8,9 Lastly, cervical elongation is considered a relative contraindication, as it represents a risk for surgical failure.10,11 This may be counteracted with trachelectomy at the time of hysteropexy or surgeries such as the Manchester repair, which involve a trachelectomy routinely,12 but currently there is no strong evidence for this as routine practice.

Continue to: Uterine preservation surgical techniques and outcomes...

Uterine preservation surgical techniques and outcomes

Le Fort colpocleisis

First described in 1840 by Neugebauer of Poland and later by Le Fort in Paris in 1877, the Le Fort colpocleisis repair technique remains the most reliable prolapse surgery to date.14 The uterus is left in place while the vagina is narrowed and shortened. It typically also is performed with a levator plication to reduce the genital hiatus.

This procedure is quick and effective, with a 90% to 95% success rate. If necessary, it can be performed under local or regional anesthesia, making it a good option for medically frail patients. It is not an option for everyone, however, as penetrative intercourse is no longer an option after surgery. Studies suggest an approximately 13% dissatisfaction rate after the procedure, with most of that coming from postoperative urinary symptoms, such as urgency or stress incontinence,15 and some studies show a dissatisfaction rate as low as 0% in a well-counseled patient population.16,17

Vaginal native tissue hysteropexy

Many patients who elect for uterine preservation at the time of prolapse surgery are “minimalists,” meaning that a vaginal native tissue procedure appeals to them due to the lack of abdominal incisions, decreased operating room time, and lack of permanent graft materials.

Of all the hysteropexy procedures, sacrospinous hysteropexy (SSHP) has the most robust data available. The approach to SSHP can be tailored to the patient’s anatomy and it is performed in a manner similar to posthysterectomy sacrospinous ligament fixation. The traditional posterior approach can be used with predominantly posterior prolapse, while an apical approach through a semilunar paracervical incision can be used for predominantly apical prolapse. Expert surgeons agree that one key to success is anchoring the suspension sutures through the cervical stroma, not just the vaginal epithelium.

Researchers in the Netherlands published the 5-year outcomes of a randomized trial that compared SSHP with vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.18 Their data showed no difference between groups in composite failure, reoperation rates, quality of life measures, and postoperative sexual function. Adverse events were very similar to those reported for posthysterectomy sacrospinous ligament fixation, including 15% transient buttock pain. Of note, the same authors explored risk factors for recurrence after SSHP and found that higher body mass index, smoking, and a large point Ba measurement were risk factors for prolapse recurrence.19

A randomized, controlled trial in the United Kingdom (the VUE trial) compared vaginal hysterectomy with apical suspension to uterine preservation with a variety of apical suspension techniques, mostly SSHP, and demonstrated no significant differences in outcomes.20 Overall, SSHP is an excellent option for many patients interested in uterine preservation.

Uterosacral ligament hysteropexy (USHP), when performed vaginally, is very similar to uterosacral ligament suspension at the time of vaginal hysterectomy, with entry into the peritoneal cavity through a posterior colpotomy. The uterosacral ligaments are grasped and delayed absorbable suture placed through the ligaments and anchored into the posterior cervical stroma. Given the maintenance of the normal axis of the vagina, USHP is a good technique for patients with isolated apical defects. Unfortunately, the least amount of quality data is available for USHP at this time. Currently, evidence suggests that complications are rare and that the procedure may offer acceptable anatomic and symptomatic outcomes.21 Some surgeons approach the uterosacral suspension laparoscopically, which also has mixed results in the literature, with failure rates between 8% and 27% and few robust studies.22–24

The Manchester-Fothergill operation, currently not common in the United States but popular in Europe, primarily is considered a treatment for cervical elongation when the uterosacral ligaments are intact. In this procedure, trachelectomy is performed and the uterosacral ligaments are plicated to the uterine body. Sturmdorf sutures are frequently placed to close off the endometrial canal, which can lead to hematometra and other complications of cervical stenosis. Previous unmatched studies have shown similar outcomes with the Manchester procedure compared with vaginal hysterectomy.25,26

The largest study currently available is a registry study from Denmark, with matched cohort populations, that compared the Manchester procedure, SSHP, and total vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.27 This study indicated less morbidity related to the Manchester procedure, decreased anterior recurrence compared with SSHP, and a 7% reoperation rate.27 The same authors also established better cost-effectiveness with the Manchester procedure as opposed to vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.28

Continue to: Vaginal mesh hysteropexy...

Vaginal mesh hysteropexy

Hysteropexy using vaginal mesh is limited in the United States given the removal of vaginal mesh kits from the market by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2019. However, a Pelvic Floor Disorders Network randomized trial compared vaginal mesh hysteropexy using the Uphold LITE transvaginal mesh support system (Boston Scientific) and vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.29 At 5 years, mesh hysteropexy had fewer failures than hysterectomy (37% vs 54%) and there was no difference in retreatment (9% vs 13%). The authors noted an 8% mesh exposure rate in the mesh hysteropexy group but 12% granulation tissue and 21% suture exposure rate in the hysterectomy group.29

While vaginal mesh hysteropexy was effective in the treatment of apical prolapse, the elevated mesh exposure rate and postoperative complications ultimately led to its removal from the market.

Sacrohysteropexy

Lastly, prolapse surgery with uterine preservation may be accomplished abdominally, most commonly laparoscopically with or without robotic assistance.

Sacrohysteropexy (SHP) involves the attachment of permanent synthetic mesh posteriorly to the posterior vagina and cervix with or without the additional placement of mesh to the anterior vagina and cervix. When the anterior mesh is placed, the arms are typically routed through the broad ligament bilaterally and joined with the posterior mesh for attachment to the anterior longitudinal ligament, overlying the sacrum.

Proponents of this technique endorse the use of mesh to augment already failing native tissues and propose similarities to the durability of sacrocolpopexy. While no randomized controlled trials have compared hysterectomy with sacrocolpopexy or supracervical hysterectomy with sacrocolpopexy to sacrohysteropexy, a meta-analysis suggests that sacrohysteropexy may have a decreased risk of mesh exposure but a higher reoperation rate with lower anatomic success.9 Randomized trials that compared abdominal sacrohysteropexy with vaginal hysterectomy and suspension indicate that apical support may be improved with sacrohysteropexy,30 but reoperations, postoperative pain and disability, and urinary dysfunction was higher with SHP.31,32

What further research is needed?

With the increasing patient and clinician interest in uterine preservation, more research is needed to improve patient counseling and surgical planning. Much of the current research compares hysteropexy outcomes with those of traditional prolapse repairs with hysterectomy, with only a few randomized trials. We are lacking robust, prospective comparison studies between hysteropexy methods, especially vaginal native tissue techniques, long-term follow-up on the prevalence of uterine or cervical pathology after hysteropexy, and pregnancy or postpartum outcomes following uterine preservation surgery.

Currently, work is underway to validate and test the effectiveness of a questionnaire to evaluate the uterus’s importance to the patient seeking prolapse surgery in order to optimize counseling. The VUE trial, which randomizes women to vaginal hysterectomy with suspension versus various prolapse surgeries with uterine preservation, is continuing its 6-year follow-up.20 In the Netherlands, an ongoing randomized, controlled trial (the SAM trial) is comparing the Manchester procedure with sacrospinous hysteropexy and will follow patients up to 24 months.33 Fortunately, both of these trials are rigorously assessing both objective and patient-centered outcomes.

CASE Counseling helps the patient weigh surgical options

After thorough review of her surgical options, the patient elects for a uterine-preserving prolapse repair. She would like to have the most minimally invasive procedure and does not want any permanent mesh used. You suggest, and she agrees to, a sacrospinous ligament hysteropexy, as it is the current technique with the most robust data. ●

- DeLancey JO. Anatomic aspects of vaginal eversion after hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(6 pt 1):1717-1724; discussion 1724-1728. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(92)91562-o.

- Madsen AM, Raker C, Sung VW. Trends in hysteropexy and apical support for uterovaginal prolapse in the United States from 2002 to 2012. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2017;23:365-371. doi:10.1097/SPV.0000000000000426.

- Korbly NB, Kassis NC, Good MM, et al. Patient preferences for uterine preservation and hysterectomy in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:470.e16. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.08.003.

- Frick AC, Barber MD, Paraiso MF, et al. Attitudes toward hysterectomy in women undergoing evaluation for uterovaginal prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19:103-109. doi:10.1097/SPV.0b013e31827d8667.

- Farquhar CM, Sadler L, Harvey SA, et al. The association of hysterectomy and menopause: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2005;112:956-962. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00696.x

- Gutman R, Maher C. Uterine-preserving POP surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1803-1813. doi:10.1007/s00192-0132171-2.

- Frick AC, Walters MD, Larkin KS, et al. Risk of unanticipated abnormal gynecologic pathology at the time of hysterectomy for uterovaginal prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:507. e1-4. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.077.

- Meriwether KV, Balk EM, Antosh DD, et al. Uterine-preserving surgeries for the repair of pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review with meta-analysis and clinical practice guidelines. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:505-522. doi:10.1007/s00192-01903876-2.

- Meriwether KV, Antosh DD, Olivera CK, et al. Uterine preservation vs hysterectomy in pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a systematic review with meta-analysis and clinical practice guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:129-146. e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2018.01.018.

- Lin TY, Su TH, Wang YL, et al. Risk factors for failure of transvaginal sacrospinous uterine suspension in the treatment of uterovaginal prolapse. J Formos Med Assoc. 2005;104:249-253.

- Hyakutake MT, Cundiff GW, Geoffrion R. Cervical elongation following sacrospinous hysteropexy: a case series. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:851-854. doi:10.1007/s00192-013-2258-9.

- Thys SD, Coolen AL, Martens IR, et al. A comparison of long-term outcome between Manchester Fothergill and vaginal hysterectomy as treatment for uterine descent. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:1171-1178. doi:10.1007/s00192-011-1422-3.

- Ridgeway BM, Meriwether KV. Uterine preservation in pelvic organ prolapse surgery. In: Walters & Karram Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery. 5th ed. Elsevier, Inc; 2022:358-373.

- FitzGerald MP, Richter HE, Siddique S, et al; for the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Colpocleisis: a review. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:261-271. doi:10.1007/s00192005-1339-9.

- Winkelman WD, Haviland MJ, Elkadry EA. Long-term pelvic f loor symptoms, recurrence, satisfaction, and regret following colpocleisis. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26:558562. doi:10.1097/SPV.000000000000602.

- Lu M, Zeng W, Ju R, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes, recurrence, satisfaction, and regret after total colpocleisis with concomitant vaginal hysterectomy: a retrospective single-center study. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27(4):e510-e515. doi:10.1097/SPV.0000000000000900.

- Wang X, Chen Y, Hua K. Pelvic symptoms, body image, and regret after LeFort colpocleisis: a long-term follow-up. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:415-419. doi:10.1016/j. jmig.2016.12.015.

- Schulten SFM, Detollenaere RJ, Stekelenburg J, et al. Sacrospinous hysteropexy versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension in women with uterine prolapse stage 2 or higher: observational followup of a multicentre randomised trial. BMJ. 2019;366:I5149. doi:10.1136/bmj.l5149.

- Schulten SF, Detollenaere RJ, IntHout J, et al. Risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse recurrence after sacrospinous hysteropexy or vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227:252.e1252.e9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.04.017.

- Hemming C, Constable L, Goulao B, et al. Surgical interventions for uterine prolapse and for vault prolapse: the two VUE RCTs. Health Technol Assess. 2020;24:1-220. doi:10.3310/hta24130.

- Romanzi LJ, Tyagi R. Hysteropexy compared to hysterectomy for uterine prolapse surgery: does durability differ? Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:625-631. doi:10.1007/s00192-011-1635-5.

- Rosen DM, Shukla A, Cario GM, et al. Is hysterectomy necessary for laparoscopic pelvic floor repair? A prospective study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:729-734. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2008.08.010.

- Bedford ND, Seman EI, O’Shea RT, et al. Effect of uterine preservation on outcome of laparoscopic uterosacral suspension. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(2):172-177. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2012.10.014.

- Diwan A, Rardin CR, Strohsnitter WC, et al. Laparoscopic uterosacral ligament uterine suspension compared with vaginal hysterectomy with vaginal vault suspension for uterovaginal prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:79-83. doi:10.1007/s00192-005-1346-x.

- de Boer TA, Milani AL, Kluivers KB, et al. The effectiveness of surgical correction of uterine prolapse: cervical amputation with uterosacral ligament plication (modified Manchester) versus vaginal hysterectomy with high uterosacral ligament plication. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:13131319. doi:10.1007/s00192-009-0945-3.

- Thomas AG, Brodman ML, Dottino PR, et al. Manchester procedure vs. vaginal hysterectomy for uterine prolapse. A comparison. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:299-304.

- Husby KR, Larsen MD, Lose G, et al. Surgical treatment of primary uterine prolapse: a comparison of vaginal native tissue surgical techniques. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:18871893. doi:10.1007/s00192-019-03950-9.

- Husby KR, Tolstrup CK, Lose G, et al. Manchester-Fothergill procedure versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension: an activity-based costing analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:1161-1171. doi:10.1007/s00192-0183575-9.

- Nager CW, Visco AG, Richter HE, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Effect of sacrospinous hysteropexy with graft vs vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension on treatment failure in women with uterovaginal prolapse: 5-year results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:153.e1-153.e31. doi:10.1016/j. ajog.2021.03.012.

- Rahmanou P, Price N, Jackson SR. Laparoscopic hysteropexy versus vaginal hysterectomy for the treatment of uterovaginal prolapse: a prospective randomized pilot study. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:1687-1694. doi:10.1007/s00192-0152761-2.

- Roovers JP, van der Vaart CH, van der Bom JG, et al. A randomised controlled trial comparing abdominal and vaginal prolapse surgery: effects on urogenital function. BJOG. 2004;111:50-56. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00001.x.

- Roovers JP, van der Bom JG, van der Vaart CH, et al. A randomized comparison of post-operative pain, quality of life, and physical performance during the first 6 weeks after abdominal or vaginal surgical correction of descensus uteri. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24:334-340. doi:10.1002/nau.20104.

- Schulten SFM, Enklaar RA, Kluivers KB, et al. Evaluation of two vaginal, uterus sparing operations for pelvic organ prolapse: modified Manchester operation (MM) and sacrospinous hysteropexy (SSH), a study protocol for a multicentre randomized non-inferiority trial (the SAM study). BMC Womens Health. 20192;19:49. doi:10.1186/ s12905-019-0749-7.

- DeLancey JO. Anatomic aspects of vaginal eversion after hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(6 pt 1):1717-1724; discussion 1724-1728. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(92)91562-o.

- Madsen AM, Raker C, Sung VW. Trends in hysteropexy and apical support for uterovaginal prolapse in the United States from 2002 to 2012. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2017;23:365-371. doi:10.1097/SPV.0000000000000426.

- Korbly NB, Kassis NC, Good MM, et al. Patient preferences for uterine preservation and hysterectomy in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:470.e16. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.08.003.

- Frick AC, Barber MD, Paraiso MF, et al. Attitudes toward hysterectomy in women undergoing evaluation for uterovaginal prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19:103-109. doi:10.1097/SPV.0b013e31827d8667.

- Farquhar CM, Sadler L, Harvey SA, et al. The association of hysterectomy and menopause: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2005;112:956-962. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00696.x

- Gutman R, Maher C. Uterine-preserving POP surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1803-1813. doi:10.1007/s00192-0132171-2.

- Frick AC, Walters MD, Larkin KS, et al. Risk of unanticipated abnormal gynecologic pathology at the time of hysterectomy for uterovaginal prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:507. e1-4. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.077.

- Meriwether KV, Balk EM, Antosh DD, et al. Uterine-preserving surgeries for the repair of pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review with meta-analysis and clinical practice guidelines. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:505-522. doi:10.1007/s00192-01903876-2.

- Meriwether KV, Antosh DD, Olivera CK, et al. Uterine preservation vs hysterectomy in pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a systematic review with meta-analysis and clinical practice guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:129-146. e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2018.01.018.

- Lin TY, Su TH, Wang YL, et al. Risk factors for failure of transvaginal sacrospinous uterine suspension in the treatment of uterovaginal prolapse. J Formos Med Assoc. 2005;104:249-253.

- Hyakutake MT, Cundiff GW, Geoffrion R. Cervical elongation following sacrospinous hysteropexy: a case series. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:851-854. doi:10.1007/s00192-013-2258-9.

- Thys SD, Coolen AL, Martens IR, et al. A comparison of long-term outcome between Manchester Fothergill and vaginal hysterectomy as treatment for uterine descent. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:1171-1178. doi:10.1007/s00192-011-1422-3.

- Ridgeway BM, Meriwether KV. Uterine preservation in pelvic organ prolapse surgery. In: Walters & Karram Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery. 5th ed. Elsevier, Inc; 2022:358-373.

- FitzGerald MP, Richter HE, Siddique S, et al; for the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Colpocleisis: a review. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:261-271. doi:10.1007/s00192005-1339-9.

- Winkelman WD, Haviland MJ, Elkadry EA. Long-term pelvic f loor symptoms, recurrence, satisfaction, and regret following colpocleisis. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26:558562. doi:10.1097/SPV.000000000000602.

- Lu M, Zeng W, Ju R, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes, recurrence, satisfaction, and regret after total colpocleisis with concomitant vaginal hysterectomy: a retrospective single-center study. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27(4):e510-e515. doi:10.1097/SPV.0000000000000900.

- Wang X, Chen Y, Hua K. Pelvic symptoms, body image, and regret after LeFort colpocleisis: a long-term follow-up. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:415-419. doi:10.1016/j. jmig.2016.12.015.

- Schulten SFM, Detollenaere RJ, Stekelenburg J, et al. Sacrospinous hysteropexy versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension in women with uterine prolapse stage 2 or higher: observational followup of a multicentre randomised trial. BMJ. 2019;366:I5149. doi:10.1136/bmj.l5149.

- Schulten SF, Detollenaere RJ, IntHout J, et al. Risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse recurrence after sacrospinous hysteropexy or vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227:252.e1252.e9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.04.017.

- Hemming C, Constable L, Goulao B, et al. Surgical interventions for uterine prolapse and for vault prolapse: the two VUE RCTs. Health Technol Assess. 2020;24:1-220. doi:10.3310/hta24130.

- Romanzi LJ, Tyagi R. Hysteropexy compared to hysterectomy for uterine prolapse surgery: does durability differ? Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:625-631. doi:10.1007/s00192-011-1635-5.

- Rosen DM, Shukla A, Cario GM, et al. Is hysterectomy necessary for laparoscopic pelvic floor repair? A prospective study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:729-734. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2008.08.010.

- Bedford ND, Seman EI, O’Shea RT, et al. Effect of uterine preservation on outcome of laparoscopic uterosacral suspension. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(2):172-177. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2012.10.014.

- Diwan A, Rardin CR, Strohsnitter WC, et al. Laparoscopic uterosacral ligament uterine suspension compared with vaginal hysterectomy with vaginal vault suspension for uterovaginal prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:79-83. doi:10.1007/s00192-005-1346-x.

- de Boer TA, Milani AL, Kluivers KB, et al. The effectiveness of surgical correction of uterine prolapse: cervical amputation with uterosacral ligament plication (modified Manchester) versus vaginal hysterectomy with high uterosacral ligament plication. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:13131319. doi:10.1007/s00192-009-0945-3.

- Thomas AG, Brodman ML, Dottino PR, et al. Manchester procedure vs. vaginal hysterectomy for uterine prolapse. A comparison. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:299-304.

- Husby KR, Larsen MD, Lose G, et al. Surgical treatment of primary uterine prolapse: a comparison of vaginal native tissue surgical techniques. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:18871893. doi:10.1007/s00192-019-03950-9.

- Husby KR, Tolstrup CK, Lose G, et al. Manchester-Fothergill procedure versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension: an activity-based costing analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:1161-1171. doi:10.1007/s00192-0183575-9.

- Nager CW, Visco AG, Richter HE, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Effect of sacrospinous hysteropexy with graft vs vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension on treatment failure in women with uterovaginal prolapse: 5-year results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:153.e1-153.e31. doi:10.1016/j. ajog.2021.03.012.

- Rahmanou P, Price N, Jackson SR. Laparoscopic hysteropexy versus vaginal hysterectomy for the treatment of uterovaginal prolapse: a prospective randomized pilot study. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:1687-1694. doi:10.1007/s00192-0152761-2.

- Roovers JP, van der Vaart CH, van der Bom JG, et al. A randomised controlled trial comparing abdominal and vaginal prolapse surgery: effects on urogenital function. BJOG. 2004;111:50-56. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00001.x.

- Roovers JP, van der Bom JG, van der Vaart CH, et al. A randomized comparison of post-operative pain, quality of life, and physical performance during the first 6 weeks after abdominal or vaginal surgical correction of descensus uteri. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24:334-340. doi:10.1002/nau.20104.

- Schulten SFM, Enklaar RA, Kluivers KB, et al. Evaluation of two vaginal, uterus sparing operations for pelvic organ prolapse: modified Manchester operation (MM) and sacrospinous hysteropexy (SSH), a study protocol for a multicentre randomized non-inferiority trial (the SAM study). BMC Womens Health. 20192;19:49. doi:10.1186/ s12905-019-0749-7.

2021 Update on pelvic floor disorders

With the increasing prevalence of pelvic floor disorders among our aging population, women’s health clinicians should be prepared to counsel patients on treatment options and posttreatment expectations. In this Update, we will review recent literature on surgical treatments for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and stress urinary incontinence (SUI). We also include our review of an award-winning and practice-changing study on office-based pessary care. Lastly, we will finish with a summary of a recent Society of Gynecologic Surgeons collaborative systematic review on sexual function after surgery.

5-year RCT data on hysteropexy vs hysterectomy for POP

Nager CW, Visco AG, Richter HE, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Effect of sacrospinous hysteropexy with graft vs vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension on treatment failure in women with uterovaginal prolapse: 5-year results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:153. e1-153.e31. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.012.

The Pelvic Floor Disorders Network conducted a multisite randomized superiority trial comparing sacrospinous hysteropexy with mesh graft to vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension for POP.

Study details

Postmenopausal women who desired surgery for symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse were randomly assigned to sacrospinous hysteropexy with polypropylene mesh graft using the Uphold-LITE device (Boston Scientific) versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension. Participants were masked to treatment allocation and completed study visits at 6-month intervals through 60 months. Quantitative prolapse POP-Q exams were performed and patients completed multiple validated questionnaires regarding the presence; severity; and impact of prolapse, urinary, bowel, and pelvic pain symptoms.

Results

A total of 183 postmenopausal women were randomized, and 156 (81 hysteropexy and 75 hysterectomy) patients completed 5-year follow up with no demographic differences between the 2 intervention groups. Operative time was statistically less in the hysteropexy group (111.5 min vs 156.7 min). There were fewer treatment failures (a composite including retreatment for prolapse, prolapse beyond the hymen, and/or bothersome bulge symptoms) in the hysteropexy than in the hysterectomy group (37% vs 54%, respectively) at 5 years of follow up. However, most patients with treatment failure were classified as an intermittent failure, with only 16% of hysteropexy patients and 22% of hysterectomy patients classified as persistent failures. There were no meaningful differences between patient-reported outcomes. Hysteropexy had an 8% mesh exposure risk, with none requiring surgical management.

This study represents the highest quality randomized trial design and boasts high patient retention rates and 5-year follow up. Findings support further investigation on the use of polypropylene mesh for POP. In April of 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration halted the selling and distribution of vaginal mesh products for prolapse repair given the lack of safety outcomes, concerns about mesh exposure rates, and possible increased rates of pelvic pain and adverse events. This study invites pelvic reconstructive surgeons to revisit the debate of hysteropexy versus hysterectomy and synthetic mesh versus native tissue repairs. The 8% mesh exposure rate represents a challenge for the future design and development of vaginal implant materials, weighing the balancing of improved long-term efficacy with the safety and complication concerns.

Continue to: Preliminary 12-month data for a single-incision sling for surgical management of SUI...

Preliminary 12-month data for a single-incision sling for surgical management of SUI

Erickson T, Roovers JP, Gheiler E, et al. A multicenter prospective study evaluating efficacy and safety of a single-incision sling procedure for stress urinary incontinence. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:93-99. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2020.04.014.

In this industry-sponsored study, researchers compared a novel single-incision sling to currently available midurethral slings for SUI with 12-month outcomes and adverse event details. However, results are primarily descriptive with no statistical testing.

Study details

Patients were eligible for inclusion in this prospective, nonrandomized cohort study if SUI was their primary incontinence symptom, with confirmatory office testing. Exclusion criteria included POP greater than stage 2, prior SUI surgery, plans for future pregnancy, elevated postvoid residuals, or concomitant surgical procedures. The single-incision Altis (Coloplast) sling was compared to all commercially available transobturator and retropubic midurethral slings. The primary outcome of this study was reduction in 24-hour pad weights, and secondary outcomes included negative cough-stress test and subjective patient-reported outcomes via validated questionnaires.

Results

A total of 184 women were enrolled in the Altis group and 171 in the comparator other sling group. Symptom severity was similar between groups, but more patients in the comparator group had mixed urinary incontinence, and more patients in the Altis group had intrinsic sphincter deficiency. The Altis group had a higher proportion of “dry patients,” but otherwise the outcomes were similar between the 2 groups, including negative cough-stress test and patientreported outcomes. Two patients in the Altis group and 7 patients in the comparator group underwent device revisions. Again, statistical analysis was not performed.

Single-incision slings may reduce the risk of groin pain associated with transobturator slings and may be a good option for patients who desire less mesh burden than the traditional retropubic slings or who are not good candidates. This trial suggests that the Altis single-incision sling may be similar in outcomes and adverse events to currently available midurethral slings, but further, more rigorous trials are underway to fully evaluate this—including a US-based multicenter randomized trial of Altis single-incision slings versus retropubic slings (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03520114).

Office-based pessary care can be safely spaced out to 24 weeks without an increase in erosions

Propst K, Mellen C, O’Sullivan DM, et al. Timing of office-based pessary care: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:100-105. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000003580.

For women already using a pessary without issues, extending office visits to every 6 months does not increase rates of vaginal epithelial abnormalities, according to results of this randomized controlled trial.

Study details

Women already using a Gelhorn, ring, or incontinence dish pessary for POP, SUI, or both were randomized to continue routine care with office evaluation every 12 weeks versus the extended-care cohort (with office evaluation every 24 weeks). Women were excluded if they removed and replaced the pessary themselves or if there was a presence of vaginal epithelial abnormalities, such as erosion or granulation tissue.

Results

The rate of vaginal epithelium erosion was 7.4% in the routine arm and 1.7% in the extended-care arm, meeting criteria for noninferiority of extended care. The majority of patients with office visits every 24 weeks preferred the less frequent examinations, and there was no difference in degree of bother due to vaginal discharge. There was also no difference in the percentage of patients with unscheduled visits. The only factors associated with vaginal epithelium abnormalities were prior abnormalities and lifetime duration of pessary use.

As there are currently no evidenced-based guidelines for pessary care, this study contributes data to support extended office-based care up to 24 weeks, a common practice in the United Kingdom. During the COVID-19 pandemic, with reduced health care access, these findings should be reassuring to clinicians and patients.

Continue to: How can we counsel patients regarding changes in sexual activity and function after surgery for POP?...

How can we counsel patients regarding changes in sexual activity and function after surgery for POP?

Antosh DD, Dieter AA, Balk EM, et al. Sexual function after pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a systematic review comparing different approaches to pelvic floor repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;2:S0002-9378(21)00610-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.05.042.

A secondary analysis of a recent systematic review found overall moderate- to high-quality evidence that were no differences in total dyspareunia, de novo dyspareunia, and scores on a validated sexual function questionnaire (PISQ12) when comparing postoperative sexual function outcomes of native tissue repair to sacrocolpopexy, transvaginal mesh, or biologic graft. Rates of postoperative dyspareunia were higher for transvaginal mesh than for sacrocolpopexy.

Study details

The Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group identified 43 original prospective, comparative studies of reconstructive prolapse surgery that reported sexual function outcomes when comparing 2 different types of POP procedures. Thirty-seven of those studies were randomized controlled trials. Specifically, they looked at data comparing outcomes for native tissue versus sacrocolpopexy, native tissue versus transvaginal mesh, native tissue versus biologic graft, and transvaginal mesh versus sacrocolpopexy.

Results

Overall, the prevalence of postoperative dyspareunia was lower than preoperatively after all surgery types. The only statistical difference in this review demonstrated higher postoperative prevalence of dyspareunia after transvaginal mesh than sacrocolpopexy, based on 2 studies. When comparing native tissue prolapse repair to transvaginal mesh, sacrocolpopexy, or biologic grafts, there were no significant differences in sexual activity, baseline, or postoperative total dyspareunia, de-novo dyspareunia, or sexual function changes as measured by the PISQ12 validated questionnaire. ●

This systematic review further contributes to the growing evidence that, regardless of surgical approach to POP, sexual function generally improves and dyspareunia rates generally decrease postoperatively, with overall low rates of de novo dyspareunia. This will help patients and providers select the best-fit surgical approach without concern for worsened sexual function. It also underscores the need for inclusion of standardized sexual function terminology use and sexual health outcomes in future prolapse surgery research.

With the increasing prevalence of pelvic floor disorders among our aging population, women’s health clinicians should be prepared to counsel patients on treatment options and posttreatment expectations. In this Update, we will review recent literature on surgical treatments for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and stress urinary incontinence (SUI). We also include our review of an award-winning and practice-changing study on office-based pessary care. Lastly, we will finish with a summary of a recent Society of Gynecologic Surgeons collaborative systematic review on sexual function after surgery.

5-year RCT data on hysteropexy vs hysterectomy for POP

Nager CW, Visco AG, Richter HE, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Effect of sacrospinous hysteropexy with graft vs vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension on treatment failure in women with uterovaginal prolapse: 5-year results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:153. e1-153.e31. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.03.012.

The Pelvic Floor Disorders Network conducted a multisite randomized superiority trial comparing sacrospinous hysteropexy with mesh graft to vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension for POP.

Study details

Postmenopausal women who desired surgery for symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse were randomly assigned to sacrospinous hysteropexy with polypropylene mesh graft using the Uphold-LITE device (Boston Scientific) versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension. Participants were masked to treatment allocation and completed study visits at 6-month intervals through 60 months. Quantitative prolapse POP-Q exams were performed and patients completed multiple validated questionnaires regarding the presence; severity; and impact of prolapse, urinary, bowel, and pelvic pain symptoms.

Results

A total of 183 postmenopausal women were randomized, and 156 (81 hysteropexy and 75 hysterectomy) patients completed 5-year follow up with no demographic differences between the 2 intervention groups. Operative time was statistically less in the hysteropexy group (111.5 min vs 156.7 min). There were fewer treatment failures (a composite including retreatment for prolapse, prolapse beyond the hymen, and/or bothersome bulge symptoms) in the hysteropexy than in the hysterectomy group (37% vs 54%, respectively) at 5 years of follow up. However, most patients with treatment failure were classified as an intermittent failure, with only 16% of hysteropexy patients and 22% of hysterectomy patients classified as persistent failures. There were no meaningful differences between patient-reported outcomes. Hysteropexy had an 8% mesh exposure risk, with none requiring surgical management.

This study represents the highest quality randomized trial design and boasts high patient retention rates and 5-year follow up. Findings support further investigation on the use of polypropylene mesh for POP. In April of 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration halted the selling and distribution of vaginal mesh products for prolapse repair given the lack of safety outcomes, concerns about mesh exposure rates, and possible increased rates of pelvic pain and adverse events. This study invites pelvic reconstructive surgeons to revisit the debate of hysteropexy versus hysterectomy and synthetic mesh versus native tissue repairs. The 8% mesh exposure rate represents a challenge for the future design and development of vaginal implant materials, weighing the balancing of improved long-term efficacy with the safety and complication concerns.

Continue to: Preliminary 12-month data for a single-incision sling for surgical management of SUI...

Preliminary 12-month data for a single-incision sling for surgical management of SUI

Erickson T, Roovers JP, Gheiler E, et al. A multicenter prospective study evaluating efficacy and safety of a single-incision sling procedure for stress urinary incontinence. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:93-99. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2020.04.014.

In this industry-sponsored study, researchers compared a novel single-incision sling to currently available midurethral slings for SUI with 12-month outcomes and adverse event details. However, results are primarily descriptive with no statistical testing.

Study details

Patients were eligible for inclusion in this prospective, nonrandomized cohort study if SUI was their primary incontinence symptom, with confirmatory office testing. Exclusion criteria included POP greater than stage 2, prior SUI surgery, plans for future pregnancy, elevated postvoid residuals, or concomitant surgical procedures. The single-incision Altis (Coloplast) sling was compared to all commercially available transobturator and retropubic midurethral slings. The primary outcome of this study was reduction in 24-hour pad weights, and secondary outcomes included negative cough-stress test and subjective patient-reported outcomes via validated questionnaires.

Results

A total of 184 women were enrolled in the Altis group and 171 in the comparator other sling group. Symptom severity was similar between groups, but more patients in the comparator group had mixed urinary incontinence, and more patients in the Altis group had intrinsic sphincter deficiency. The Altis group had a higher proportion of “dry patients,” but otherwise the outcomes were similar between the 2 groups, including negative cough-stress test and patientreported outcomes. Two patients in the Altis group and 7 patients in the comparator group underwent device revisions. Again, statistical analysis was not performed.