User login

Total Joint Arthroplasty Quality Ratings: How Are They Similar and How Are They Different?

ABSTRACT

A patient’s perception of hospital or provider quality can have far-reaching effects, as it can impact reimbursement, patient selection of a surgeon, and healthcare competition. A variety of organizations offer quality designations for orthopedic surgery and its subspecialties. Our goal is to compare total joint arthroplasty (TJA) quality designation methodology across key quality rating organizations. One researcher conducted an initial Google search to determine organizations providing quality designations for hospitals and surgeons providing orthopedic procedures with a focus on TJA. Organizations that offer quality designation specific to TJA were determined. Organizations that provided general orthopedic surgery or only surgeon-specific quality designation were excluded from the analysis. The senior author confirmed the inclusion of the final organizations. Seven organizations fit our inclusion criteria. Only the private payers and The Joint Commission required hospital accreditation to meet quality designation criteria. Total arthroplasty volume was considered in 86% of the organizations’ methodologies, and 57% of organizations utilized process measurements such as antibiotic prophylaxis and care pathways. In addition, 57% of organizations included patient experience in their methodologies. Only 29% of organizations included a cost element in their methodology. All organizations utilized outcome data and publicly reported all hospitals receiving their quality designation. Hospital quality designation methodologies are inconsistent in the context of TJA. All stakeholders (ie, providers, payers, and patients) should be involved in deciding the definition of quality.

Continue to: Healthcare in the United States...

Healthcare in the United States has begun to move toward a system focused on value for patients, defined as health outcome per dollar expended.1 Indeed, an estimated 30% of Medicare payments are now made using the so-called alternative payment models (eg, bundled payments),2 and there is an expectation that consumerism in medicine will continue to expand.3 In addition, although there is a continuing debate regarding the benefits and pitfalls of hospital mergers, there is no question whether provider consolidation has increased dramatically in recent years.4 At the core of many of these changes is the push to improve healthcare quality and reduce costs.

Quality has the ability to affect payment, patient selection of providers, and hospital competition. Patients (ie, healthcare consumers) are increasingly using the Internet to find a variety of health information.5 Accessible provider quality information online would allow patients to make more informed decisions about where to seek care. In addition, the development of transparent quality ratings could assist payers in driving beneficiaries to higher quality and better value providers, which could mean more business for the highest quality physicians and better patient outcomes with fewer complications. Some payers such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have already started using quality measures as part of their reimbursement strategy.6 Because CMS is the largest payer in the United States, private insurers tend to follow their lead; thus, quality measurements will become even more common as a factor in reimbursement over the coming years.

To make quality ratings useful, “quality” must be clearly defined. Clarity around which factors are considered in a quality designation will create transparency for patients and allow providers to understand how their performance is being measured so that they focus on improving outcomes for their patients. Numerous organizations, including private payers, public payers, and both not-for-profit and for-profit entities, have created quality designation programs to rate providers. However, within orthopedics and several other medical specialties, there has been an ongoing debate about what measures best reflect quality.7 Although inconsistencies in quality ratings in arthroplasty care have been noted,8 it remains unknown how each quality designation program compares with the others in terms of the factors considered in deciding quality designations.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate publicly available information from key quality designation programs for total joint arthroplasty (TJA) providers to determine what factors are considered by each organization in awarding quality designations; what similarities and differences in quality designations exist across the different organizations; and how many of the organizations publish their quality designation methodologies and final rating results.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A directed Google search was conducted to determine organizations (ie, payers, independent firms, and government entities) that rate hospitals and/or surgeons in orthopedic surgery. The identified organizations were then examined to determine whether they provided hospital ratings for total hip and/or knee arthroplasty. Entities were included if they provided quality designations for hospitals specifically addressing TJA. Organizations that provided only general hospital, other surgical procedures, orthopedic surgery, or orthopedic surgeon-specific quality designations were excluded. A list of all organizations determined to fit the inclusion criteria was then reviewed for completeness and approved by the senior author.

Continue to: One investigator reviewed the website of each organization...

One investigator reviewed the website of each organization fitting the inclusion criteria to determine the full rating methodology in 1 sitting on July 2, 2016. Detailed notes were taken on each program using publicly available information. For organizations that used proprietary criteria for quality designation (eg, The Joint Commission [TJC]), only publicly available information was used in the analysis. Therefore, the information reported is solely based on data available online to the public.

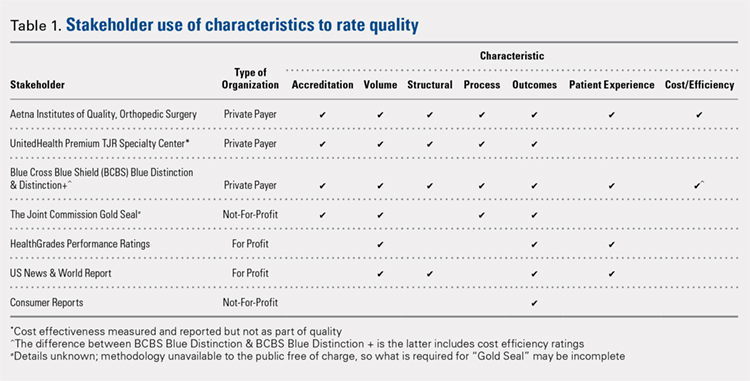

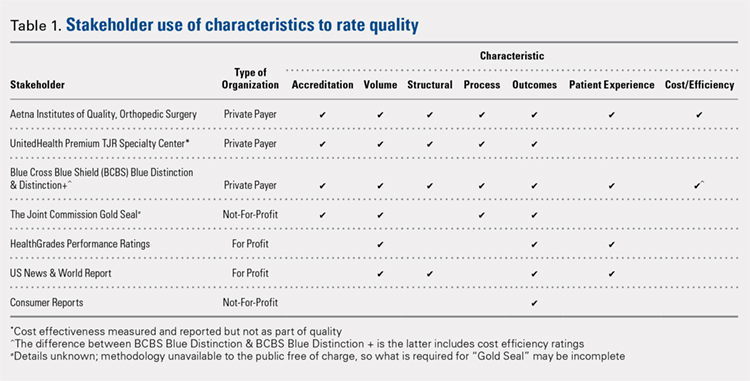

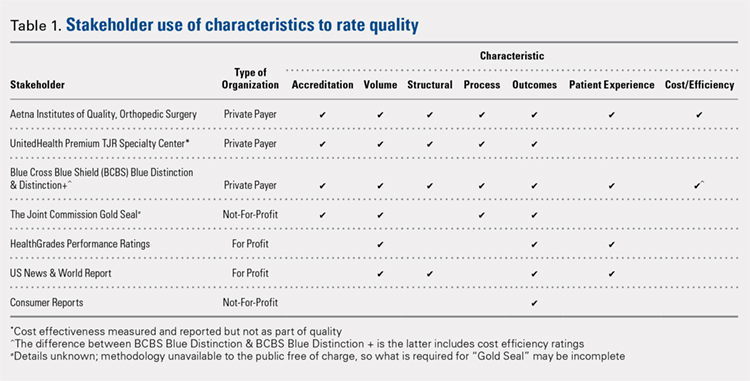

Detailed quality designation criteria were condensed into broader categories (accreditation, volume, structural, process, outcomes, patient experience, and cost/efficiency) to capture differences between each organization reviewed. In addition, we recorded whether each organization published a list of providers that received its quality designation.

RESULTS

A total of 7 organizations fit our inclusion criteria9-15 (Table). Of these 7 organizations, 3 were private payers (Aetna, UnitedHealth, and Blue Cross Blue Shield [BCBS]), 2 were nongovernmental not-for-profit organizations (TJC and Consumer Reports), and 2 were consumer-based and/or for-profit organizations (HealthGrades and US News & World Report [USNWR]). There were no government agencies that fit our inclusion criteria. BCBS had the following 2 separate quality designations: BCBS Blue Distinction and BCBS Blue Distinction+. The only difference between the 2 BCBS ratings is that BCBS Blue Distinction+ includes cost efficiency ratings, whereas BCBS Blue Distinction does not.

Only the 3 private payers and TJC, the primary hospital accreditation body in the United States, required accreditation as part of its quality designation criteria. TJC requires its own accreditation for quality designation consideration, whereas the 3 private payers allow accreditation from one of a variety of sources. Aetna Institutes of Quality for Orthopedic Surgery requires accreditation by TJC, Healthcare Facilities Accreditation Program, American Osteopathic Association, National Integrated Accreditation for Healthcare Organizations, or Det Norske Veritas Healthcare. UnitedHealth Premium Total Joint Replacement (TJR) Specialty Center requires accreditation by TJC and/or equivalent of TJC accreditation. However, TJC accreditation equivalents are not noted in the UnitedHealth handbook. BCBS Blue Distinction and Distinction+ require accreditation by TJC, Healthcare Facilities Accreditation Program, National Integrated Accreditation for Healthcare Organizations, or Center for Improvement in Healthcare Quality. In addition, BCBS is willing to consider alternative accreditations that are at least as stringent as the national alternatives noted. However, no detailed criteria that must be met to be equivalent to the national standards are noted in the relevant quality designation handbook.

The volume of completed total hip and knee arthroplasty procedures was considered in 6 of the organizations’ quality ratings methodologies. Of those 6, all private payers, TJC (not-for-profit), and 2 for-profit rating agencies were included. Surgeon specialization in TJA was only explicitly noted as a factor considered in UnitedHealth Premium TJR Specialty Center criteria; however, the requirements for surgeon specialization were not clearly defined. In addition, the presence of a multidisciplinary clinical pathway was only explicitly considered for Aetna Institutes of Quality for Orthopedic Surgery.

Structural requirements (eg, use of electronic health records [EHR], staffing levels, etc.) were taken into account in private payer and USNWR quality methodologies. Process measures (eg, antibiotic prophylaxis and other care pathways) were considered for the private payers and TJC but not for USNWR quality designation. Cost and/or efficiency measures were factors in the quality formula for Aetna Institutes of Quality for Orthopedic Surgery and BCBS Distinction+. Aetna utilizes its own cost data and risk-adjusts using a product known as Symmetry Episode Risk Groups to determine cost-effectiveness, while BCBS uses its own Composite Facility Cost Index. Patient experience (eg, Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems [HCAHPS]) was incorporated into the quality formulas for 4 of the 7 quality designation programs examined.

Continue to: All of the 7 quality designation programs included...

All of the 7 quality designation programs included outcomes (ie, readmission rates and/or mortality rates) and publicly reported the hospitals receiving their quality designation. In contrast, only Aetna explicitly included the presence of multidisciplinary clinical care pathways as part of their quality designation criteria. In addition, only UnitedHealth included surgeon specialization in joint arthroplasty as a factor for quality consideration for its quality designation program. BCBS Distinction+ and Aetna Institutes of Quality for Orthopedic Surgery were the only 2 quality designations that included at least 1 variable that fit into each of the 7 characteristics considered (accreditation, volume, structural, process, outcomes, patient experience, and cost/efficiency).

DISCUSSION

As healthcare continues to shift toward value-based delivery and payment models, quality becomes a critical factor in reimbursement and provider rankings. However, quality is a vague term. Several providers probably do not know what is required to be designated as high quality by a particular rating agency. Moreover, there are multiple quality designation programs, all using distinct criteria to determine “quality,” which further complicates the matter. Our objective was to determine the key stakeholders that provide quality designations in TJA and what criteria each organization uses in assessing quality.

Our idea of comprehensive quality is based on Avedis Donabedian’s enduring framework for healthcare quality focused on structure, process, and outcome.16 We expanded on these 3 areas and analyzed quality designations based on variables fitting into the following categories: accreditation, volume, structural, process, outcomes, patient experience, and cost/efficiency. We believe that these categories encompass a comprehensive rating system that addresses key elements of patient care. However, our results suggest that only 2 major quality designations (BCBS Distinction+ and Aetna Institutes of Quality for Orthopedic Surgery) take all such variables into account.

All quality designation programs that we analyzed required outcome data (ie, readmission and/or mortality rates within 30 days); however, only 2 programs utilized cost in their quality designation criteria (BCBS Distinction+ and Aetna Institutes of Quality for Orthopedic Surgery). Aetna Institutes of Quality for Orthopedic Surgery risk-adjusted for its cost-effectiveness calculations based on age, sex, and other unspecified conditions using a product known as Symmetry Episode Risk Groups. However, the organization also noted that although it did risk-adjust for inpatient mortality, it did not do so for pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis. BCBS Distinction+ also utilized risk adjustment for its cost efficiency measure, and its step-by-step methodology is available online. Further, Consumer Reports does risk-adjust using logistic regression models in their quality analysis, but the description provided is minimal; it is noted that such risk adjustments are already completed by CMS prior to Consumer Reports acquiring the data. The CMS Compare model information is available on the CMS website. The data utilized by several organizations and presented on CMS Compare are already risk-adjusted using CMS’ approach. In contrast, UnitedHealth Premium TJR Specialty Center gathers its own data from providers and does not describe a risk adjustment methodology. Risk adjustment is important because the lack of risk adjustment may lead to physicians “cherry-picking” easy cases to boost positive outcomes, leading to increased financial benefits and higher quality ratings. Having a consistent risk adjustment formula will ensure accurate comparisons across outcomes and cost-effectiveness measures used by quality designation programs.

Factors considered for quality designation varied greatly from one organization to the other. The range of categories of factors considered varied from 1 (Consumer Reports only considered outcome data) to all 7 categories (BCBS Distinction+ and Aetna Institutes of Quality for Orthopedic Surgery). Our findings are consistent with the work by Keswani and colleagues,8 which showed that there is likely variation in factors considered when rating hospital quality more broadly. Our work suggests that quality designation formulas do not appear to get more consistent when focused on TJA.

We found that all organizations in our analysis published the providers earning their quality designation. However, TJC does not provide publicly a detailed methodology on how to qualify for its quality designation. The price to purchase the necessary manual for this information is $146.00 for accredited organizations and $186.00 for all others.17 For large healthcare providers, this is not a large sum of money. Nonetheless, this provides an additional hurdle for stakeholders to gain a full understanding of the requirements to receive a TJC Gold Seal for Orthopedics.

Previous work has evaluated the consistency of and the variety of means of gauging healthcare quality. Previous work by Rothberg and colleagues18 comparing hospital rankings across 5 common consumer-oriented websites found disagreement on hospital rankings within any diagnosis and even among metrics such as mortality. Another study by Halasyamani and Davis19 found that CMS Compare and USNWR rankings were dissimilar and the authors attributed the discrepancy to different methodologies. In addition, a study by Krumholz and colleagues20 focused on Internet report cards, which measured the appropriate use of select medications and mortality rates for acute myocardial infarction as the quality metrics. The authors found that, in aggregate, there was a clear difference in quality of care and outcomes but that comparisons between 2 hospitals provided poor discrimination.20 Other work has analyzed the increasing trend of online ratings of orthopedic surgeons by patients.21 However, there remains no agreed-upon definition of quality. Thus, the use of the term “quality” in several studies may be misleading.

Our results must be interpreted keeping the limitations of our work in mind. First, we used expert knowledge and a public search engine to develop our list of organizations that provide TJA quality designations. However, there is a possibility that we did not include all relevant organizations. Second, although all authors reviewed the final data, it is possible that there was human error in the analysis of each organization’s quality designation criteria.

CONCLUSION

As healthcare progresses further toward a system that rewards providers for delivering value to patients, accurately defining and measuring quality becomes critical because it can be suggestive of value to patients, payers, and providers. Furthermore, it gives providers a goal to focus on as they strive to improve the value of care they deliver to patients. Measuring healthcare quality is currently a novel, imperfect science,22 and there continues to be a debate about what factors should be included in a quality designation formula. Nonetheless, more and more quality designations and performance measurements are being created for orthopedic care, including total hip and total knee arthroplasty. In fact, in 2016, The Leapfrog Group added readmission for patients undergoing TJA to its survey.23 Consensus on a quality definition may facilitate the movement toward a value-based healthcare system. Future research should evaluate strategies for gaining consensus among stakeholders for a universal quality metric in TJA. Surgeons, hospitals, payers, and most importantly patients should play critical roles in defining quality.

- Porter ME. A strategy for health care reform--toward a value-based system. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(2):109-112. doi:10.1056/NEJMp0904131.

- Obama B. United States health care reform: progress to date and next steps. JAMA. 2016;316(5):525-532. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.9797.

- Mulvany C. The march to consumerism the evolution from patient to active shopper continues. Healthc Financ Manage. 2014;68(2):36-38.

- Tsai TC, Jha AK. Hospital consolidation, competition, and quality: is bigger necessarily better? JAMA. 2014;312(1):29-30. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.4692.

- Cline RJ, Haynes KM. Consumer health information seeking on the Internet: the state of the art. Health Educ Res. 2001;16(6):671-692. doi:10.1093/her/16.6.671.

- Werner RM, Kolstad JT, Stuart EA, Polsky D. The effect of pay-for-performance in hospitals: lessons for quality improvement. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(4):690-698. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1277.

- Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB, Birkmeyer NJ. Measuring the quality of surgical care: structure, process, or outcomes? J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198(4):626-632. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.11.017.

- Keswani A, Uhler LM, Bozic KJ. What quality metrics is my hospital being evaluated on and what are the consequences? J Arthroplast. 2016;31(6):1139-1143. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2016.01.075.

- Aetna Inc. Aetna Institutes of Quality® facilities fact book. A comprehensive reference guide for Aetna members, doctors and health care professionals. http://www.aetna.com/individuals-families-health-insurance/document-libr.... Accessed July 2, 2016.

- United HealthCare. UnitedHealth Premium® Program. https://www.uhcprovider.com/en/reports-quality-programs/premium-designation.html. Accessed July 2, 2016.

- 11. Blue Cross Blue Shield. Association. Blue Distinction Specialty Care. Selection criteria and program documentation: knee and hip replacement and spine surgery. https://www.bcbs.com/sites/default/files/fileattachments/page/KneeHip.SelectionCriteria_0.pdf. Published October 2015. Accessed July 2, 2016.

- The Joint Commission. Advanced certification for total hip and total knee replacement eligibility. https://www.jointcommission.org/advanced_certification_for_total_hip_and.... Published December 10, 2015. Accessed July 2, 2016.

- Healthgrades Operating Company. Healthgrades methodology: anatomy of a rating. https://www.healthgrades.com/quality/ratings-awards/methodology. Accessed July 2, 2016.

- Comarow A, Harder B; Dr. Foster Project Team. Methodology: U.S. News & World Report best hospitals for common care. U.S. News & World Report Web site. http://www.usnews.com/pubfiles/BHCC_MethReport_2015.pdf. Published May 20, 2015. Accessed July 2, 2016.

- Consumer Reports. How we rate hospitals. http://static3.consumerreportscdn.org/content/dam/cro/news_articles/heal.... Accessed July 2, 2016.

- Ayanian JZ, Markel H. Donabedian’s lasting framework for health care quality. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(3):205-207. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1605101.

- The Joint Commission. 2016 Certification Manuals. 2016; http://www.jcrinc.com/2016-certification-manuals/. Accessed July 2, 2016.

- Rothberg MB, Morsi E, Benjamin EM, Pekow PS, Lindenauer PK. Choosing the best hospital: the limitations of public quality reporting. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(6):1680-1687. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.27.6.1680.

- Halasyamani LK, Davis MM. Conflicting measures of hospital quality: ratings from "Hospital Compare" versus "Best Hospitals". J Hosp Med. 2007;2(3):128-134. doi:10.1002/jhm.176.

- Krumholz HM, Rathore SS, Chen J, Wang Y, Radford MJ. Evaluation of a consumer-oriented internet health care report card: the risk of quality ratings based on mortality data. JAMA. 2002;287(10):1277-1287.

- Frost C, Mesfin A. Online reviews of orthopedic surgeons: an emerging trend. Orthopedics. 2015;38(4):e257-e262. doi:10.3928/01477447-20150402-52.

- Harder B, Comarow A. Hospital Quality reporting by US News & World Report: why, how, and what's ahead. JAMA. 2015;313(19):1903-1904. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.4566.

- The Leapfrog Group. New in 2016. http://www.leapfroggroup.org/ratings-reports/new-2016. Accessed July 2, 2016.

ABSTRACT

A patient’s perception of hospital or provider quality can have far-reaching effects, as it can impact reimbursement, patient selection of a surgeon, and healthcare competition. A variety of organizations offer quality designations for orthopedic surgery and its subspecialties. Our goal is to compare total joint arthroplasty (TJA) quality designation methodology across key quality rating organizations. One researcher conducted an initial Google search to determine organizations providing quality designations for hospitals and surgeons providing orthopedic procedures with a focus on TJA. Organizations that offer quality designation specific to TJA were determined. Organizations that provided general orthopedic surgery or only surgeon-specific quality designation were excluded from the analysis. The senior author confirmed the inclusion of the final organizations. Seven organizations fit our inclusion criteria. Only the private payers and The Joint Commission required hospital accreditation to meet quality designation criteria. Total arthroplasty volume was considered in 86% of the organizations’ methodologies, and 57% of organizations utilized process measurements such as antibiotic prophylaxis and care pathways. In addition, 57% of organizations included patient experience in their methodologies. Only 29% of organizations included a cost element in their methodology. All organizations utilized outcome data and publicly reported all hospitals receiving their quality designation. Hospital quality designation methodologies are inconsistent in the context of TJA. All stakeholders (ie, providers, payers, and patients) should be involved in deciding the definition of quality.

Continue to: Healthcare in the United States...

Healthcare in the United States has begun to move toward a system focused on value for patients, defined as health outcome per dollar expended.1 Indeed, an estimated 30% of Medicare payments are now made using the so-called alternative payment models (eg, bundled payments),2 and there is an expectation that consumerism in medicine will continue to expand.3 In addition, although there is a continuing debate regarding the benefits and pitfalls of hospital mergers, there is no question whether provider consolidation has increased dramatically in recent years.4 At the core of many of these changes is the push to improve healthcare quality and reduce costs.

Quality has the ability to affect payment, patient selection of providers, and hospital competition. Patients (ie, healthcare consumers) are increasingly using the Internet to find a variety of health information.5 Accessible provider quality information online would allow patients to make more informed decisions about where to seek care. In addition, the development of transparent quality ratings could assist payers in driving beneficiaries to higher quality and better value providers, which could mean more business for the highest quality physicians and better patient outcomes with fewer complications. Some payers such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have already started using quality measures as part of their reimbursement strategy.6 Because CMS is the largest payer in the United States, private insurers tend to follow their lead; thus, quality measurements will become even more common as a factor in reimbursement over the coming years.

To make quality ratings useful, “quality” must be clearly defined. Clarity around which factors are considered in a quality designation will create transparency for patients and allow providers to understand how their performance is being measured so that they focus on improving outcomes for their patients. Numerous organizations, including private payers, public payers, and both not-for-profit and for-profit entities, have created quality designation programs to rate providers. However, within orthopedics and several other medical specialties, there has been an ongoing debate about what measures best reflect quality.7 Although inconsistencies in quality ratings in arthroplasty care have been noted,8 it remains unknown how each quality designation program compares with the others in terms of the factors considered in deciding quality designations.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate publicly available information from key quality designation programs for total joint arthroplasty (TJA) providers to determine what factors are considered by each organization in awarding quality designations; what similarities and differences in quality designations exist across the different organizations; and how many of the organizations publish their quality designation methodologies and final rating results.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A directed Google search was conducted to determine organizations (ie, payers, independent firms, and government entities) that rate hospitals and/or surgeons in orthopedic surgery. The identified organizations were then examined to determine whether they provided hospital ratings for total hip and/or knee arthroplasty. Entities were included if they provided quality designations for hospitals specifically addressing TJA. Organizations that provided only general hospital, other surgical procedures, orthopedic surgery, or orthopedic surgeon-specific quality designations were excluded. A list of all organizations determined to fit the inclusion criteria was then reviewed for completeness and approved by the senior author.

Continue to: One investigator reviewed the website of each organization...

One investigator reviewed the website of each organization fitting the inclusion criteria to determine the full rating methodology in 1 sitting on July 2, 2016. Detailed notes were taken on each program using publicly available information. For organizations that used proprietary criteria for quality designation (eg, The Joint Commission [TJC]), only publicly available information was used in the analysis. Therefore, the information reported is solely based on data available online to the public.

Detailed quality designation criteria were condensed into broader categories (accreditation, volume, structural, process, outcomes, patient experience, and cost/efficiency) to capture differences between each organization reviewed. In addition, we recorded whether each organization published a list of providers that received its quality designation.

RESULTS

A total of 7 organizations fit our inclusion criteria9-15 (Table). Of these 7 organizations, 3 were private payers (Aetna, UnitedHealth, and Blue Cross Blue Shield [BCBS]), 2 were nongovernmental not-for-profit organizations (TJC and Consumer Reports), and 2 were consumer-based and/or for-profit organizations (HealthGrades and US News & World Report [USNWR]). There were no government agencies that fit our inclusion criteria. BCBS had the following 2 separate quality designations: BCBS Blue Distinction and BCBS Blue Distinction+. The only difference between the 2 BCBS ratings is that BCBS Blue Distinction+ includes cost efficiency ratings, whereas BCBS Blue Distinction does not.

Only the 3 private payers and TJC, the primary hospital accreditation body in the United States, required accreditation as part of its quality designation criteria. TJC requires its own accreditation for quality designation consideration, whereas the 3 private payers allow accreditation from one of a variety of sources. Aetna Institutes of Quality for Orthopedic Surgery requires accreditation by TJC, Healthcare Facilities Accreditation Program, American Osteopathic Association, National Integrated Accreditation for Healthcare Organizations, or Det Norske Veritas Healthcare. UnitedHealth Premium Total Joint Replacement (TJR) Specialty Center requires accreditation by TJC and/or equivalent of TJC accreditation. However, TJC accreditation equivalents are not noted in the UnitedHealth handbook. BCBS Blue Distinction and Distinction+ require accreditation by TJC, Healthcare Facilities Accreditation Program, National Integrated Accreditation for Healthcare Organizations, or Center for Improvement in Healthcare Quality. In addition, BCBS is willing to consider alternative accreditations that are at least as stringent as the national alternatives noted. However, no detailed criteria that must be met to be equivalent to the national standards are noted in the relevant quality designation handbook.

The volume of completed total hip and knee arthroplasty procedures was considered in 6 of the organizations’ quality ratings methodologies. Of those 6, all private payers, TJC (not-for-profit), and 2 for-profit rating agencies were included. Surgeon specialization in TJA was only explicitly noted as a factor considered in UnitedHealth Premium TJR Specialty Center criteria; however, the requirements for surgeon specialization were not clearly defined. In addition, the presence of a multidisciplinary clinical pathway was only explicitly considered for Aetna Institutes of Quality for Orthopedic Surgery.

Structural requirements (eg, use of electronic health records [EHR], staffing levels, etc.) were taken into account in private payer and USNWR quality methodologies. Process measures (eg, antibiotic prophylaxis and other care pathways) were considered for the private payers and TJC but not for USNWR quality designation. Cost and/or efficiency measures were factors in the quality formula for Aetna Institutes of Quality for Orthopedic Surgery and BCBS Distinction+. Aetna utilizes its own cost data and risk-adjusts using a product known as Symmetry Episode Risk Groups to determine cost-effectiveness, while BCBS uses its own Composite Facility Cost Index. Patient experience (eg, Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems [HCAHPS]) was incorporated into the quality formulas for 4 of the 7 quality designation programs examined.

Continue to: All of the 7 quality designation programs included...

All of the 7 quality designation programs included outcomes (ie, readmission rates and/or mortality rates) and publicly reported the hospitals receiving their quality designation. In contrast, only Aetna explicitly included the presence of multidisciplinary clinical care pathways as part of their quality designation criteria. In addition, only UnitedHealth included surgeon specialization in joint arthroplasty as a factor for quality consideration for its quality designation program. BCBS Distinction+ and Aetna Institutes of Quality for Orthopedic Surgery were the only 2 quality designations that included at least 1 variable that fit into each of the 7 characteristics considered (accreditation, volume, structural, process, outcomes, patient experience, and cost/efficiency).

DISCUSSION

As healthcare continues to shift toward value-based delivery and payment models, quality becomes a critical factor in reimbursement and provider rankings. However, quality is a vague term. Several providers probably do not know what is required to be designated as high quality by a particular rating agency. Moreover, there are multiple quality designation programs, all using distinct criteria to determine “quality,” which further complicates the matter. Our objective was to determine the key stakeholders that provide quality designations in TJA and what criteria each organization uses in assessing quality.

Our idea of comprehensive quality is based on Avedis Donabedian’s enduring framework for healthcare quality focused on structure, process, and outcome.16 We expanded on these 3 areas and analyzed quality designations based on variables fitting into the following categories: accreditation, volume, structural, process, outcomes, patient experience, and cost/efficiency. We believe that these categories encompass a comprehensive rating system that addresses key elements of patient care. However, our results suggest that only 2 major quality designations (BCBS Distinction+ and Aetna Institutes of Quality for Orthopedic Surgery) take all such variables into account.

All quality designation programs that we analyzed required outcome data (ie, readmission and/or mortality rates within 30 days); however, only 2 programs utilized cost in their quality designation criteria (BCBS Distinction+ and Aetna Institutes of Quality for Orthopedic Surgery). Aetna Institutes of Quality for Orthopedic Surgery risk-adjusted for its cost-effectiveness calculations based on age, sex, and other unspecified conditions using a product known as Symmetry Episode Risk Groups. However, the organization also noted that although it did risk-adjust for inpatient mortality, it did not do so for pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis. BCBS Distinction+ also utilized risk adjustment for its cost efficiency measure, and its step-by-step methodology is available online. Further, Consumer Reports does risk-adjust using logistic regression models in their quality analysis, but the description provided is minimal; it is noted that such risk adjustments are already completed by CMS prior to Consumer Reports acquiring the data. The CMS Compare model information is available on the CMS website. The data utilized by several organizations and presented on CMS Compare are already risk-adjusted using CMS’ approach. In contrast, UnitedHealth Premium TJR Specialty Center gathers its own data from providers and does not describe a risk adjustment methodology. Risk adjustment is important because the lack of risk adjustment may lead to physicians “cherry-picking” easy cases to boost positive outcomes, leading to increased financial benefits and higher quality ratings. Having a consistent risk adjustment formula will ensure accurate comparisons across outcomes and cost-effectiveness measures used by quality designation programs.

Factors considered for quality designation varied greatly from one organization to the other. The range of categories of factors considered varied from 1 (Consumer Reports only considered outcome data) to all 7 categories (BCBS Distinction+ and Aetna Institutes of Quality for Orthopedic Surgery). Our findings are consistent with the work by Keswani and colleagues,8 which showed that there is likely variation in factors considered when rating hospital quality more broadly. Our work suggests that quality designation formulas do not appear to get more consistent when focused on TJA.

We found that all organizations in our analysis published the providers earning their quality designation. However, TJC does not provide publicly a detailed methodology on how to qualify for its quality designation. The price to purchase the necessary manual for this information is $146.00 for accredited organizations and $186.00 for all others.17 For large healthcare providers, this is not a large sum of money. Nonetheless, this provides an additional hurdle for stakeholders to gain a full understanding of the requirements to receive a TJC Gold Seal for Orthopedics.

Previous work has evaluated the consistency of and the variety of means of gauging healthcare quality. Previous work by Rothberg and colleagues18 comparing hospital rankings across 5 common consumer-oriented websites found disagreement on hospital rankings within any diagnosis and even among metrics such as mortality. Another study by Halasyamani and Davis19 found that CMS Compare and USNWR rankings were dissimilar and the authors attributed the discrepancy to different methodologies. In addition, a study by Krumholz and colleagues20 focused on Internet report cards, which measured the appropriate use of select medications and mortality rates for acute myocardial infarction as the quality metrics. The authors found that, in aggregate, there was a clear difference in quality of care and outcomes but that comparisons between 2 hospitals provided poor discrimination.20 Other work has analyzed the increasing trend of online ratings of orthopedic surgeons by patients.21 However, there remains no agreed-upon definition of quality. Thus, the use of the term “quality” in several studies may be misleading.

Our results must be interpreted keeping the limitations of our work in mind. First, we used expert knowledge and a public search engine to develop our list of organizations that provide TJA quality designations. However, there is a possibility that we did not include all relevant organizations. Second, although all authors reviewed the final data, it is possible that there was human error in the analysis of each organization’s quality designation criteria.

CONCLUSION

As healthcare progresses further toward a system that rewards providers for delivering value to patients, accurately defining and measuring quality becomes critical because it can be suggestive of value to patients, payers, and providers. Furthermore, it gives providers a goal to focus on as they strive to improve the value of care they deliver to patients. Measuring healthcare quality is currently a novel, imperfect science,22 and there continues to be a debate about what factors should be included in a quality designation formula. Nonetheless, more and more quality designations and performance measurements are being created for orthopedic care, including total hip and total knee arthroplasty. In fact, in 2016, The Leapfrog Group added readmission for patients undergoing TJA to its survey.23 Consensus on a quality definition may facilitate the movement toward a value-based healthcare system. Future research should evaluate strategies for gaining consensus among stakeholders for a universal quality metric in TJA. Surgeons, hospitals, payers, and most importantly patients should play critical roles in defining quality.

ABSTRACT

A patient’s perception of hospital or provider quality can have far-reaching effects, as it can impact reimbursement, patient selection of a surgeon, and healthcare competition. A variety of organizations offer quality designations for orthopedic surgery and its subspecialties. Our goal is to compare total joint arthroplasty (TJA) quality designation methodology across key quality rating organizations. One researcher conducted an initial Google search to determine organizations providing quality designations for hospitals and surgeons providing orthopedic procedures with a focus on TJA. Organizations that offer quality designation specific to TJA were determined. Organizations that provided general orthopedic surgery or only surgeon-specific quality designation were excluded from the analysis. The senior author confirmed the inclusion of the final organizations. Seven organizations fit our inclusion criteria. Only the private payers and The Joint Commission required hospital accreditation to meet quality designation criteria. Total arthroplasty volume was considered in 86% of the organizations’ methodologies, and 57% of organizations utilized process measurements such as antibiotic prophylaxis and care pathways. In addition, 57% of organizations included patient experience in their methodologies. Only 29% of organizations included a cost element in their methodology. All organizations utilized outcome data and publicly reported all hospitals receiving their quality designation. Hospital quality designation methodologies are inconsistent in the context of TJA. All stakeholders (ie, providers, payers, and patients) should be involved in deciding the definition of quality.

Continue to: Healthcare in the United States...

Healthcare in the United States has begun to move toward a system focused on value for patients, defined as health outcome per dollar expended.1 Indeed, an estimated 30% of Medicare payments are now made using the so-called alternative payment models (eg, bundled payments),2 and there is an expectation that consumerism in medicine will continue to expand.3 In addition, although there is a continuing debate regarding the benefits and pitfalls of hospital mergers, there is no question whether provider consolidation has increased dramatically in recent years.4 At the core of many of these changes is the push to improve healthcare quality and reduce costs.

Quality has the ability to affect payment, patient selection of providers, and hospital competition. Patients (ie, healthcare consumers) are increasingly using the Internet to find a variety of health information.5 Accessible provider quality information online would allow patients to make more informed decisions about where to seek care. In addition, the development of transparent quality ratings could assist payers in driving beneficiaries to higher quality and better value providers, which could mean more business for the highest quality physicians and better patient outcomes with fewer complications. Some payers such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have already started using quality measures as part of their reimbursement strategy.6 Because CMS is the largest payer in the United States, private insurers tend to follow their lead; thus, quality measurements will become even more common as a factor in reimbursement over the coming years.

To make quality ratings useful, “quality” must be clearly defined. Clarity around which factors are considered in a quality designation will create transparency for patients and allow providers to understand how their performance is being measured so that they focus on improving outcomes for their patients. Numerous organizations, including private payers, public payers, and both not-for-profit and for-profit entities, have created quality designation programs to rate providers. However, within orthopedics and several other medical specialties, there has been an ongoing debate about what measures best reflect quality.7 Although inconsistencies in quality ratings in arthroplasty care have been noted,8 it remains unknown how each quality designation program compares with the others in terms of the factors considered in deciding quality designations.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate publicly available information from key quality designation programs for total joint arthroplasty (TJA) providers to determine what factors are considered by each organization in awarding quality designations; what similarities and differences in quality designations exist across the different organizations; and how many of the organizations publish their quality designation methodologies and final rating results.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A directed Google search was conducted to determine organizations (ie, payers, independent firms, and government entities) that rate hospitals and/or surgeons in orthopedic surgery. The identified organizations were then examined to determine whether they provided hospital ratings for total hip and/or knee arthroplasty. Entities were included if they provided quality designations for hospitals specifically addressing TJA. Organizations that provided only general hospital, other surgical procedures, orthopedic surgery, or orthopedic surgeon-specific quality designations were excluded. A list of all organizations determined to fit the inclusion criteria was then reviewed for completeness and approved by the senior author.

Continue to: One investigator reviewed the website of each organization...

One investigator reviewed the website of each organization fitting the inclusion criteria to determine the full rating methodology in 1 sitting on July 2, 2016. Detailed notes were taken on each program using publicly available information. For organizations that used proprietary criteria for quality designation (eg, The Joint Commission [TJC]), only publicly available information was used in the analysis. Therefore, the information reported is solely based on data available online to the public.

Detailed quality designation criteria were condensed into broader categories (accreditation, volume, structural, process, outcomes, patient experience, and cost/efficiency) to capture differences between each organization reviewed. In addition, we recorded whether each organization published a list of providers that received its quality designation.

RESULTS

A total of 7 organizations fit our inclusion criteria9-15 (Table). Of these 7 organizations, 3 were private payers (Aetna, UnitedHealth, and Blue Cross Blue Shield [BCBS]), 2 were nongovernmental not-for-profit organizations (TJC and Consumer Reports), and 2 were consumer-based and/or for-profit organizations (HealthGrades and US News & World Report [USNWR]). There were no government agencies that fit our inclusion criteria. BCBS had the following 2 separate quality designations: BCBS Blue Distinction and BCBS Blue Distinction+. The only difference between the 2 BCBS ratings is that BCBS Blue Distinction+ includes cost efficiency ratings, whereas BCBS Blue Distinction does not.

Only the 3 private payers and TJC, the primary hospital accreditation body in the United States, required accreditation as part of its quality designation criteria. TJC requires its own accreditation for quality designation consideration, whereas the 3 private payers allow accreditation from one of a variety of sources. Aetna Institutes of Quality for Orthopedic Surgery requires accreditation by TJC, Healthcare Facilities Accreditation Program, American Osteopathic Association, National Integrated Accreditation for Healthcare Organizations, or Det Norske Veritas Healthcare. UnitedHealth Premium Total Joint Replacement (TJR) Specialty Center requires accreditation by TJC and/or equivalent of TJC accreditation. However, TJC accreditation equivalents are not noted in the UnitedHealth handbook. BCBS Blue Distinction and Distinction+ require accreditation by TJC, Healthcare Facilities Accreditation Program, National Integrated Accreditation for Healthcare Organizations, or Center for Improvement in Healthcare Quality. In addition, BCBS is willing to consider alternative accreditations that are at least as stringent as the national alternatives noted. However, no detailed criteria that must be met to be equivalent to the national standards are noted in the relevant quality designation handbook.

The volume of completed total hip and knee arthroplasty procedures was considered in 6 of the organizations’ quality ratings methodologies. Of those 6, all private payers, TJC (not-for-profit), and 2 for-profit rating agencies were included. Surgeon specialization in TJA was only explicitly noted as a factor considered in UnitedHealth Premium TJR Specialty Center criteria; however, the requirements for surgeon specialization were not clearly defined. In addition, the presence of a multidisciplinary clinical pathway was only explicitly considered for Aetna Institutes of Quality for Orthopedic Surgery.

Structural requirements (eg, use of electronic health records [EHR], staffing levels, etc.) were taken into account in private payer and USNWR quality methodologies. Process measures (eg, antibiotic prophylaxis and other care pathways) were considered for the private payers and TJC but not for USNWR quality designation. Cost and/or efficiency measures were factors in the quality formula for Aetna Institutes of Quality for Orthopedic Surgery and BCBS Distinction+. Aetna utilizes its own cost data and risk-adjusts using a product known as Symmetry Episode Risk Groups to determine cost-effectiveness, while BCBS uses its own Composite Facility Cost Index. Patient experience (eg, Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems [HCAHPS]) was incorporated into the quality formulas for 4 of the 7 quality designation programs examined.

Continue to: All of the 7 quality designation programs included...

All of the 7 quality designation programs included outcomes (ie, readmission rates and/or mortality rates) and publicly reported the hospitals receiving their quality designation. In contrast, only Aetna explicitly included the presence of multidisciplinary clinical care pathways as part of their quality designation criteria. In addition, only UnitedHealth included surgeon specialization in joint arthroplasty as a factor for quality consideration for its quality designation program. BCBS Distinction+ and Aetna Institutes of Quality for Orthopedic Surgery were the only 2 quality designations that included at least 1 variable that fit into each of the 7 characteristics considered (accreditation, volume, structural, process, outcomes, patient experience, and cost/efficiency).

DISCUSSION

As healthcare continues to shift toward value-based delivery and payment models, quality becomes a critical factor in reimbursement and provider rankings. However, quality is a vague term. Several providers probably do not know what is required to be designated as high quality by a particular rating agency. Moreover, there are multiple quality designation programs, all using distinct criteria to determine “quality,” which further complicates the matter. Our objective was to determine the key stakeholders that provide quality designations in TJA and what criteria each organization uses in assessing quality.

Our idea of comprehensive quality is based on Avedis Donabedian’s enduring framework for healthcare quality focused on structure, process, and outcome.16 We expanded on these 3 areas and analyzed quality designations based on variables fitting into the following categories: accreditation, volume, structural, process, outcomes, patient experience, and cost/efficiency. We believe that these categories encompass a comprehensive rating system that addresses key elements of patient care. However, our results suggest that only 2 major quality designations (BCBS Distinction+ and Aetna Institutes of Quality for Orthopedic Surgery) take all such variables into account.

All quality designation programs that we analyzed required outcome data (ie, readmission and/or mortality rates within 30 days); however, only 2 programs utilized cost in their quality designation criteria (BCBS Distinction+ and Aetna Institutes of Quality for Orthopedic Surgery). Aetna Institutes of Quality for Orthopedic Surgery risk-adjusted for its cost-effectiveness calculations based on age, sex, and other unspecified conditions using a product known as Symmetry Episode Risk Groups. However, the organization also noted that although it did risk-adjust for inpatient mortality, it did not do so for pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis. BCBS Distinction+ also utilized risk adjustment for its cost efficiency measure, and its step-by-step methodology is available online. Further, Consumer Reports does risk-adjust using logistic regression models in their quality analysis, but the description provided is minimal; it is noted that such risk adjustments are already completed by CMS prior to Consumer Reports acquiring the data. The CMS Compare model information is available on the CMS website. The data utilized by several organizations and presented on CMS Compare are already risk-adjusted using CMS’ approach. In contrast, UnitedHealth Premium TJR Specialty Center gathers its own data from providers and does not describe a risk adjustment methodology. Risk adjustment is important because the lack of risk adjustment may lead to physicians “cherry-picking” easy cases to boost positive outcomes, leading to increased financial benefits and higher quality ratings. Having a consistent risk adjustment formula will ensure accurate comparisons across outcomes and cost-effectiveness measures used by quality designation programs.

Factors considered for quality designation varied greatly from one organization to the other. The range of categories of factors considered varied from 1 (Consumer Reports only considered outcome data) to all 7 categories (BCBS Distinction+ and Aetna Institutes of Quality for Orthopedic Surgery). Our findings are consistent with the work by Keswani and colleagues,8 which showed that there is likely variation in factors considered when rating hospital quality more broadly. Our work suggests that quality designation formulas do not appear to get more consistent when focused on TJA.

We found that all organizations in our analysis published the providers earning their quality designation. However, TJC does not provide publicly a detailed methodology on how to qualify for its quality designation. The price to purchase the necessary manual for this information is $146.00 for accredited organizations and $186.00 for all others.17 For large healthcare providers, this is not a large sum of money. Nonetheless, this provides an additional hurdle for stakeholders to gain a full understanding of the requirements to receive a TJC Gold Seal for Orthopedics.

Previous work has evaluated the consistency of and the variety of means of gauging healthcare quality. Previous work by Rothberg and colleagues18 comparing hospital rankings across 5 common consumer-oriented websites found disagreement on hospital rankings within any diagnosis and even among metrics such as mortality. Another study by Halasyamani and Davis19 found that CMS Compare and USNWR rankings were dissimilar and the authors attributed the discrepancy to different methodologies. In addition, a study by Krumholz and colleagues20 focused on Internet report cards, which measured the appropriate use of select medications and mortality rates for acute myocardial infarction as the quality metrics. The authors found that, in aggregate, there was a clear difference in quality of care and outcomes but that comparisons between 2 hospitals provided poor discrimination.20 Other work has analyzed the increasing trend of online ratings of orthopedic surgeons by patients.21 However, there remains no agreed-upon definition of quality. Thus, the use of the term “quality” in several studies may be misleading.

Our results must be interpreted keeping the limitations of our work in mind. First, we used expert knowledge and a public search engine to develop our list of organizations that provide TJA quality designations. However, there is a possibility that we did not include all relevant organizations. Second, although all authors reviewed the final data, it is possible that there was human error in the analysis of each organization’s quality designation criteria.

CONCLUSION

As healthcare progresses further toward a system that rewards providers for delivering value to patients, accurately defining and measuring quality becomes critical because it can be suggestive of value to patients, payers, and providers. Furthermore, it gives providers a goal to focus on as they strive to improve the value of care they deliver to patients. Measuring healthcare quality is currently a novel, imperfect science,22 and there continues to be a debate about what factors should be included in a quality designation formula. Nonetheless, more and more quality designations and performance measurements are being created for orthopedic care, including total hip and total knee arthroplasty. In fact, in 2016, The Leapfrog Group added readmission for patients undergoing TJA to its survey.23 Consensus on a quality definition may facilitate the movement toward a value-based healthcare system. Future research should evaluate strategies for gaining consensus among stakeholders for a universal quality metric in TJA. Surgeons, hospitals, payers, and most importantly patients should play critical roles in defining quality.

- Porter ME. A strategy for health care reform--toward a value-based system. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(2):109-112. doi:10.1056/NEJMp0904131.

- Obama B. United States health care reform: progress to date and next steps. JAMA. 2016;316(5):525-532. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.9797.

- Mulvany C. The march to consumerism the evolution from patient to active shopper continues. Healthc Financ Manage. 2014;68(2):36-38.

- Tsai TC, Jha AK. Hospital consolidation, competition, and quality: is bigger necessarily better? JAMA. 2014;312(1):29-30. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.4692.

- Cline RJ, Haynes KM. Consumer health information seeking on the Internet: the state of the art. Health Educ Res. 2001;16(6):671-692. doi:10.1093/her/16.6.671.

- Werner RM, Kolstad JT, Stuart EA, Polsky D. The effect of pay-for-performance in hospitals: lessons for quality improvement. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(4):690-698. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1277.

- Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB, Birkmeyer NJ. Measuring the quality of surgical care: structure, process, or outcomes? J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198(4):626-632. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.11.017.

- Keswani A, Uhler LM, Bozic KJ. What quality metrics is my hospital being evaluated on and what are the consequences? J Arthroplast. 2016;31(6):1139-1143. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2016.01.075.

- Aetna Inc. Aetna Institutes of Quality® facilities fact book. A comprehensive reference guide for Aetna members, doctors and health care professionals. http://www.aetna.com/individuals-families-health-insurance/document-libr.... Accessed July 2, 2016.

- United HealthCare. UnitedHealth Premium® Program. https://www.uhcprovider.com/en/reports-quality-programs/premium-designation.html. Accessed July 2, 2016.

- 11. Blue Cross Blue Shield. Association. Blue Distinction Specialty Care. Selection criteria and program documentation: knee and hip replacement and spine surgery. https://www.bcbs.com/sites/default/files/fileattachments/page/KneeHip.SelectionCriteria_0.pdf. Published October 2015. Accessed July 2, 2016.

- The Joint Commission. Advanced certification for total hip and total knee replacement eligibility. https://www.jointcommission.org/advanced_certification_for_total_hip_and.... Published December 10, 2015. Accessed July 2, 2016.

- Healthgrades Operating Company. Healthgrades methodology: anatomy of a rating. https://www.healthgrades.com/quality/ratings-awards/methodology. Accessed July 2, 2016.

- Comarow A, Harder B; Dr. Foster Project Team. Methodology: U.S. News & World Report best hospitals for common care. U.S. News & World Report Web site. http://www.usnews.com/pubfiles/BHCC_MethReport_2015.pdf. Published May 20, 2015. Accessed July 2, 2016.

- Consumer Reports. How we rate hospitals. http://static3.consumerreportscdn.org/content/dam/cro/news_articles/heal.... Accessed July 2, 2016.

- Ayanian JZ, Markel H. Donabedian’s lasting framework for health care quality. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(3):205-207. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1605101.

- The Joint Commission. 2016 Certification Manuals. 2016; http://www.jcrinc.com/2016-certification-manuals/. Accessed July 2, 2016.

- Rothberg MB, Morsi E, Benjamin EM, Pekow PS, Lindenauer PK. Choosing the best hospital: the limitations of public quality reporting. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(6):1680-1687. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.27.6.1680.

- Halasyamani LK, Davis MM. Conflicting measures of hospital quality: ratings from "Hospital Compare" versus "Best Hospitals". J Hosp Med. 2007;2(3):128-134. doi:10.1002/jhm.176.

- Krumholz HM, Rathore SS, Chen J, Wang Y, Radford MJ. Evaluation of a consumer-oriented internet health care report card: the risk of quality ratings based on mortality data. JAMA. 2002;287(10):1277-1287.

- Frost C, Mesfin A. Online reviews of orthopedic surgeons: an emerging trend. Orthopedics. 2015;38(4):e257-e262. doi:10.3928/01477447-20150402-52.

- Harder B, Comarow A. Hospital Quality reporting by US News & World Report: why, how, and what's ahead. JAMA. 2015;313(19):1903-1904. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.4566.

- The Leapfrog Group. New in 2016. http://www.leapfroggroup.org/ratings-reports/new-2016. Accessed July 2, 2016.

- Porter ME. A strategy for health care reform--toward a value-based system. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(2):109-112. doi:10.1056/NEJMp0904131.

- Obama B. United States health care reform: progress to date and next steps. JAMA. 2016;316(5):525-532. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.9797.

- Mulvany C. The march to consumerism the evolution from patient to active shopper continues. Healthc Financ Manage. 2014;68(2):36-38.

- Tsai TC, Jha AK. Hospital consolidation, competition, and quality: is bigger necessarily better? JAMA. 2014;312(1):29-30. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.4692.

- Cline RJ, Haynes KM. Consumer health information seeking on the Internet: the state of the art. Health Educ Res. 2001;16(6):671-692. doi:10.1093/her/16.6.671.

- Werner RM, Kolstad JT, Stuart EA, Polsky D. The effect of pay-for-performance in hospitals: lessons for quality improvement. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(4):690-698. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1277.

- Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB, Birkmeyer NJ. Measuring the quality of surgical care: structure, process, or outcomes? J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198(4):626-632. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.11.017.

- Keswani A, Uhler LM, Bozic KJ. What quality metrics is my hospital being evaluated on and what are the consequences? J Arthroplast. 2016;31(6):1139-1143. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2016.01.075.

- Aetna Inc. Aetna Institutes of Quality® facilities fact book. A comprehensive reference guide for Aetna members, doctors and health care professionals. http://www.aetna.com/individuals-families-health-insurance/document-libr.... Accessed July 2, 2016.

- United HealthCare. UnitedHealth Premium® Program. https://www.uhcprovider.com/en/reports-quality-programs/premium-designation.html. Accessed July 2, 2016.

- 11. Blue Cross Blue Shield. Association. Blue Distinction Specialty Care. Selection criteria and program documentation: knee and hip replacement and spine surgery. https://www.bcbs.com/sites/default/files/fileattachments/page/KneeHip.SelectionCriteria_0.pdf. Published October 2015. Accessed July 2, 2016.

- The Joint Commission. Advanced certification for total hip and total knee replacement eligibility. https://www.jointcommission.org/advanced_certification_for_total_hip_and.... Published December 10, 2015. Accessed July 2, 2016.

- Healthgrades Operating Company. Healthgrades methodology: anatomy of a rating. https://www.healthgrades.com/quality/ratings-awards/methodology. Accessed July 2, 2016.

- Comarow A, Harder B; Dr. Foster Project Team. Methodology: U.S. News & World Report best hospitals for common care. U.S. News & World Report Web site. http://www.usnews.com/pubfiles/BHCC_MethReport_2015.pdf. Published May 20, 2015. Accessed July 2, 2016.

- Consumer Reports. How we rate hospitals. http://static3.consumerreportscdn.org/content/dam/cro/news_articles/heal.... Accessed July 2, 2016.

- Ayanian JZ, Markel H. Donabedian’s lasting framework for health care quality. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(3):205-207. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1605101.

- The Joint Commission. 2016 Certification Manuals. 2016; http://www.jcrinc.com/2016-certification-manuals/. Accessed July 2, 2016.

- Rothberg MB, Morsi E, Benjamin EM, Pekow PS, Lindenauer PK. Choosing the best hospital: the limitations of public quality reporting. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(6):1680-1687. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.27.6.1680.

- Halasyamani LK, Davis MM. Conflicting measures of hospital quality: ratings from "Hospital Compare" versus "Best Hospitals". J Hosp Med. 2007;2(3):128-134. doi:10.1002/jhm.176.

- Krumholz HM, Rathore SS, Chen J, Wang Y, Radford MJ. Evaluation of a consumer-oriented internet health care report card: the risk of quality ratings based on mortality data. JAMA. 2002;287(10):1277-1287.

- Frost C, Mesfin A. Online reviews of orthopedic surgeons: an emerging trend. Orthopedics. 2015;38(4):e257-e262. doi:10.3928/01477447-20150402-52.

- Harder B, Comarow A. Hospital Quality reporting by US News & World Report: why, how, and what's ahead. JAMA. 2015;313(19):1903-1904. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.4566.

- The Leapfrog Group. New in 2016. http://www.leapfroggroup.org/ratings-reports/new-2016. Accessed July 2, 2016.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- TJA quality designation methodologies differ substantially across rating organizations.

- Only 29% of TJA quality rating methodologies evaluated include a cost element.

- Only 57% of TJA quality rating methodologies evaluated include patient experience.

- Only 57% of TJA quality rating methodologies evaluated include process measurements, including antibiotic prophylaxis and standardized care pathways.

- There is a need for consistent definitions of quality as healthcare stakeholders continue to shift focus from volume to value.