User login

Raising the bar (and the OR table):Ergonomics in MIGS

Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs) are “musculoskeletal disorders (injuries or disorders of the muscles, nerves, tendons, joints, cartilage, and spinal discs) in which the work environment and performance of work contribute significantly to the condition; and/or the condition is made worse or persists longer due to work conditions.”1 The health care industry has one of the highest rates of WMSDs, even when compared with traditional labor-intensive occupations, such as coal mining. In 2017, the health care industry reported more than a half million incidents of work-related injury and illness.2,3 In particular, surgeons are at increased risk for WMSDs, since they repetitively perform the classic tenets of poor ergonomics, including operating in static, extreme, and awkward positions and for prolonged periods of time.3

Gynecologic surgeons face unique ergonomic challenges. Operating in the pelvis requires an oblique approach that adds complexity and inhibits appropriate ergonomic positioning.4 All modalities of surgery incur their own challenges and risks to the surgeon, including minimally invasive gynecologic surgery (MIGS), which has become the standard of care for most conditions. Although MIGS has several benefits for the patient, a survey of gynecologic oncologists found that 88% of respondents reported discomfort related to MIGS.5 Several factors contribute to the development of WMSDs in surgery, including lack of ergonomic awareness, suboptimal ergonomic education and training,5,6 and ergonomically poor operating room (OR) equipment and instrument design.7 Furthermore, surgical culture does not generally prioritize ergonomics in the OR or requests for ergonomic accommodations.7,8

Within 5 years, a physician workforce shortage is projected for the United States.9 WMSDs contribute to workforce issues as they are associated with decreased productivity; time off needed for pain and treatment, including short-term disability; and possibly early retirement (as those who are older and have more work experience may be more likely to seek medical attention).10 In a 2013 study of vaginal surgeons, 14% missed work; 21% modified their work hours, work type, or amount of surgery; and 29% modified their surgical technique because of injury.10 Work-related pain also can negatively affect mental health, sleep, relationships, and quality of life.6

Recently, awareness has increased regarding WMSDs and their consequences, which has led to significant strides in the study of ergonomics among surgeons, a growing body of research on the topic, and guidance for optimizing ergonomics in the OR.

Risk factors for ergonomic strain

Several factors contribute to ergonomic strain and, subsequently, the development of WMSDs. Recognizing these factors can direct strategies for injury prevention.

Patient factors

The prevalence of obesity in the United States increased from 30.5% in 1999–2000 to 41.9% between 2017 and 2020.11 As the average patient’s body mass index (BMI) has increased, there is concern for a parallel increase in the ergonomic strain on laparoscopic surgeons.

A study of simulated laparoscopic tasks at varying model BMI levels demonstrated increased surgeon postural stress and workload at higher model BMIs (50 kg/m2) when compared with lower model BMIs (20 and 30 kg/m2).11 This result was supported in another study, which demonstrated both increased muscle activity and increased time needed to complete a surgical task with laparoscopic surgery; interestingly, when the same study measured these parameters for robotic surgery, this association was not seen.12 This suggests that a robotic rather than a laparoscopic approach may avoid some of the ergonomic strain associated with increased patient BMI.

Continue to: Surgeon factors...

Surgeon factors

Various surgeon characteristics have been shown to influence ergonomics in the OR. Surgeons with smaller hand sizes, for example, reported greater physical discomfort and demonstrated greater ergonomic workload when operating laparoscopically.13-15 In particular, those with a glove size of 6.5 or smaller have more difficulty using laparoscopic instruments, and those with a glove size smaller than 7 demonstrate a larger decline in grip strength when using laparoscopic instruments repeatedly.14,16

Surgeon height also can affect the amount of time spent in high-risk, nonergonomic positions. In a study that evaluated video recordings of surgeon posture during gynecologic laparoscopy, shorter surgeons were noted to use greater degrees of neck rotation to look at the monitor.17 Furthermore, surgeons with shorter arm lengths experienced more “extreme positions” of the nondominant shoulder and elbow.17 This trend also was seen in open and robotic surgery, where surgeons with a height of 66 cm or less reported increased pain scores after operating.18

Surgical instruments and OR setup

Surgical instrument characteristics can contribute to ergonomic strain, especially when the instruments have been designed with a one-size-fits-all mentality.8,19 In an examination of the anthropometric measurements of surgeon hand sizes and their correlation with difficulty when using a “standard” laparoscopic instrument, surgeons with smaller finger and hand spans had trouble using these instruments.19 Another study compared surgeon grip strength and ergonomic workloads after using 3 laparoscopic advanced bipolar instruments.16 Gender and hand size aside, the authors found that use of several of the laparoscopic devices led to greater decline in grip strength.16

The setup of the OR also can have a profound effect on the surgeon’s ergonomics. Monitor placement, for example, is crucial to ergonomic success. One study found that positioning the monitor directly in front of the surgeon at eye level was associated with the lowest neck muscle activity during a simulated task.20

Route of surgery

Each surgical approach has intrinsic ergonomic risks. With laparoscopy, surgeons often remain in straight head and back positions without much trunk motion, especially when compared with open surgery.21 In one study, laparoscopic surgeons spent more than 60% of a case in a static position and more than 80% of a case in a high-risk, “demanding” neck position.22

Robotic surgery, in contrast to laparoscopy, often has been cited as being more “ergonomic.” While robotic surgery has less of an effect on the neck, shoulders, arms, and legs than laparoscopy23 and often is associated with less physical discomfort than either open or laparoscopic surgery,23,24 robotic surgery still maintains its own innate ergonomic risks. Of robotic surgeons surveyed, 56.1% reported neck stiffness, finger fatigue, and eye symptoms in one study.25 In another survey study, more robotic surgeons (72%) reported physical symptoms than laparoscopic (57%) and open (49%) surgeons.26Vaginal surgery also puts surgeons at ergonomic risk. A majority of surgeons (87.2%) who completed more than 50% of their cases vaginally reported a history of WMSDs.10 Vaginal surgery places surgeons in awkward positions of the neck, shoulder, and trunk frequently and for longer durations.27

Continue to: Strategies for preventing WMSDs...

Strategies for preventing WMSDs

As factors that contribute to the development of WMSDs are identified, preventive strategies can be targeted to these individual factors. Research has focused on appropriate setup of the OR, surgeon posture, intraoperative microbreaks, and stretching both in and outside of the OR.

1. OR setup and positioning of the surgeon by MIGS route

The route of MIGS affects OR setup and surgeon posture. Ergonomic recommendations for laparoscopy, robotic surgery, and vaginal surgery are all unique to the risks posed by each particular approach.

Laparoscopic surgery. Laparoscopic monitors should face the surgeon directly, with the screen just below eye level to maintain the surgeon’s neck in a neutral position.28 The table height should be set for the tallest surgeon, and shorter surgeons should stand on steps as needed.28 The table height also should allow for the surgeon’s hands to be at elbow height, with the elbows bent at 90 degrees with the wrists straight.29 Foot pedals should be placed at the surgeons’ foot level and should be reached easily.28 Additionally, the patient’s arms should be tucked at their sides to allow surgeons a larger operative space.29 When using laparoscopic instruments, locking and ratcheting features should be used whenever possible to reduce prolonged grip or squeeze forces.28 The laparoscopic camera should be held in the palm with the wrist in a neutral position.29

Robotic surgery. Positioning and setup of the robotic console is a main focus of ergonomic recommendations. The surgeon’s chair should be brought as close to the console as possible, and the knees positioned in a 90-degree angle.30 The foot pedals should be brought toward the surgeon to maintain this angle of the knees.30 The console should be rotated toward the surgeon and then the height adjusted so that the surgeon can look through the eyepiece while sitting upright and can maintain the neck in a neutral position.28,30 The surgeon’s forehead should rest comfortably on the headrest.29 The forearms should rest on the armrest while the arms are maintained in a neutral position and the shoulders remain relaxed while the surgeon holds the robotic controls.30 It is important to utilize the armrest often to relieve stress on the arm while operating.28 Frequent use of the clutch function can keep the robotic controls in the center of the workspace.28

Vaginal surgery. Both seated and standing positions are associated with high-risk positioning of the trunk and bilateral shoulders, respectively, in vaginal surgery.31 However, surgeons who stand while operating vaginally reported more discomfort in the bilateral wrists, thighs, and lower legs than those who operated while seated.31 This suggests a potential ergonomic advantage to the seated position for vaginal surgery. Chair height should be adjusted so the surgeon can look straight ahead with the neck in a neutral position.32 Surgeons should consider using a headlamp, as this may prevent repetitive awkward movements to adjust overhead lights.32 For standing surgery, the table height should be adjusted for the tallest surgeon, and shorter surgeons or assistants should use steps as needed.3

Surgical assistants should switch sides during the course of the case to avoid excessive unilateral upper-extremity strain.32 The addition of a table-mounted vaginal retractor system may be useful in relieving physical strain for surgical assistants, but data currently are lacking to demonstrate this ergonomic benefit.33 Further studies are needed, especially since many surgeons take on the role of surgical assist in the teaching environment and subsequently report more WMSDs than their colleagues who do not work in teaching environments.10,34

2. Pain relief from individual ergonomic positioning devices

Apart from adjusting how the OR equipment is arranged or how the surgeons adjust their positioning, several devices that assist with surgeon positioning—including gel mats or insoles, exoskeletons, and “augmented reality” glasses—are being studied.

The use of gel mats or insoles in the OR has mixed evidence in the literature.35-37

Exoskeletons, external devices that support a surgeon’s posture and positioning, have been studied thus far in simulated nonsterile surgical environments. Preliminarily, it appears that use of an exoskeleton can decrease muscle activity and time spent in static positions, with a reported decrease in post-task user discomfort.38,39 More data are needed to determine if exoskeletons can be used in the sterile setting and for longer durations as may occur in actual OR cases.

Augmented reality glasses project the laparoscopic monitor image to the glasses, which frees the surgeon to place the “monitor” in a more neutral, ergonomic position. In one study, use of augmented reality glasses was associated with decreased muscle activity and a reduction in Rapid Entire Body Assessment (REBA) scores when compared with use of the conventional laparoscopic monitor.40More data are needed on these emerging technologies to determine whether adverse effects occur with prolonged use.

Continue to: 3. Implementing intraoperative microbreaks and stretching...

3. Implementing intraoperative microbreaks and stretching

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) recommends that surgeons avoid prolonged static postures during procedures.28 One strategy for preventing sustained positioning is to incorporate breaks with associated stretching routinely during surgery.28

Microbreaks. In a landmark study by Park and colleagues in 2017, 120-second long targeted stretching microbreaks (TSMBs) were completed every 20 to 40 minutes during a surgery, and results demonstrated improved postoperative surgeon pain scores without an associated increase in the length of the case.41 These surgeons reported improved pain in the neck, bilateral shoulders, bilateral hands, and lower back. Eighty-eight percent of surgeons reported either improvement or “no change” in their mental focus, and 100% reported improvement or “no change” in their physical performance after TSMBs were implemented.42 Of surveyed surgeons, 87% wanted TSMBs incorporated routinely.41,42

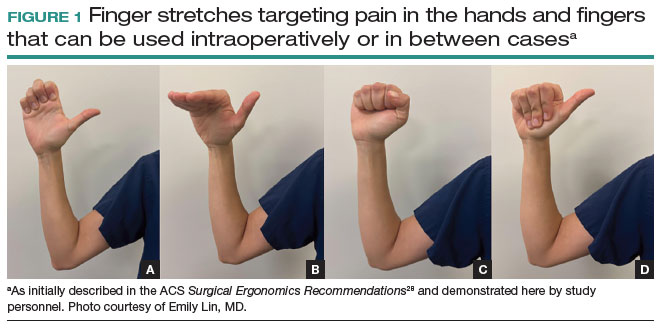

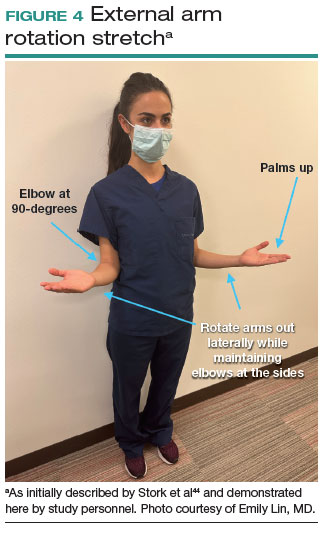

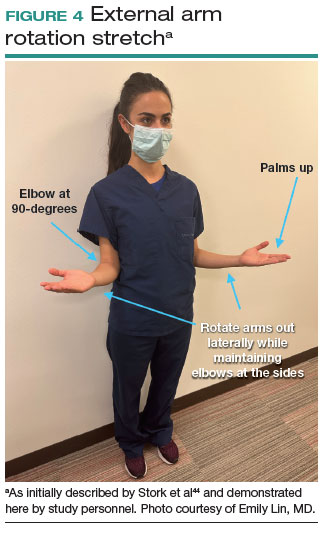

Stretches. Multiple resources, such as the ACS and the Mayo Clinic, for intraoperative stretches are available. The ACS recommends performing neck and shoulder stretches during intraoperative microbreaks, including a range-of-movement neck exercise, deep cervical flexor training, and standing scapular retraction.28 The ACS also demonstrates lumbrical stretches for the fingers and passive wrist extension exercises to be used intraoperatively (or between cases) (FIGURE 1).28 The Mayo Clinic Hallbeck Human Factors Engineering Laboratories has a publicly available “OR Stretch Instructional Video” in which the surgeon is guided through several different short stretches, including shoulder shrugging and side bends, that can be used during surgery.43

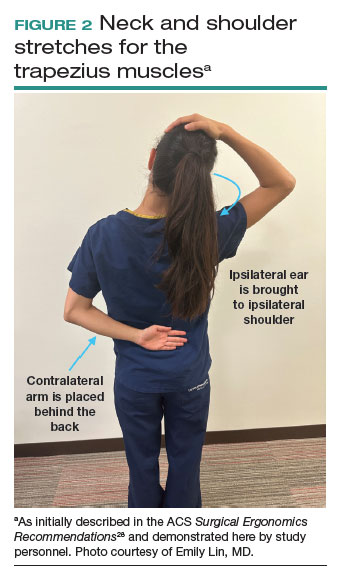

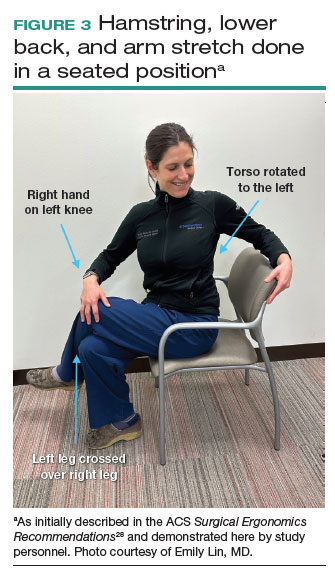

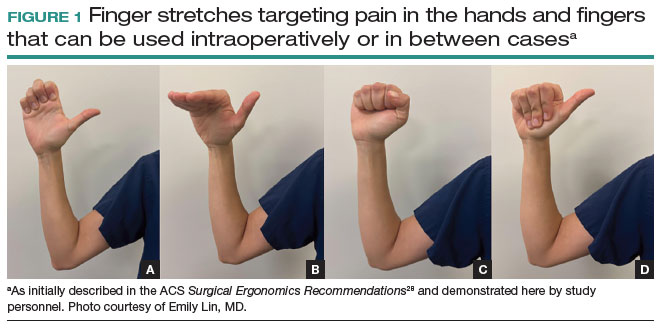

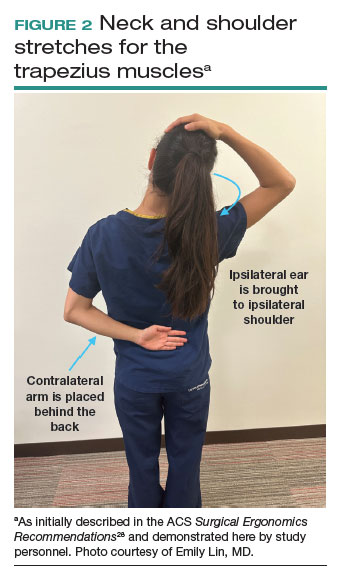

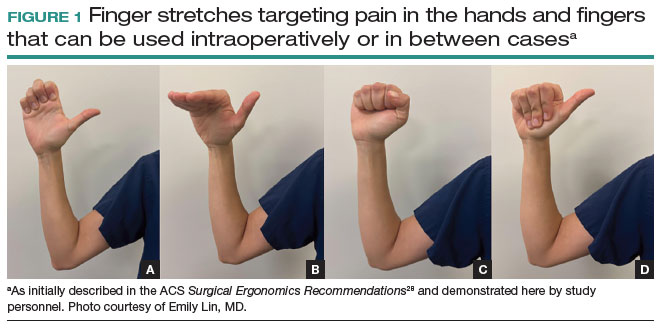

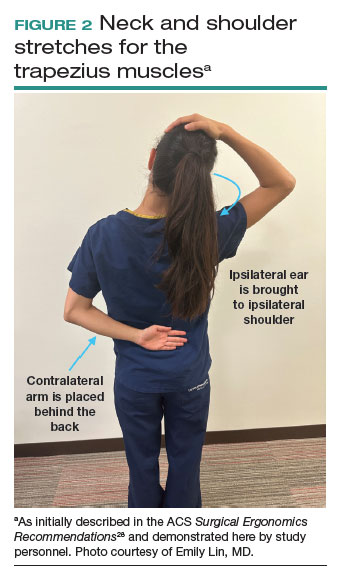

Both the ACS and the Mayo Clinic provide examples of pertinent stretch exercises for use when not in the sterile environment, between cases or after cases are complete. The ACS recommends several neck and shoulder stretches for the trapezius, levator scapulae, and pectoralis and recommends the use of a foam roller to improve thoracic mobility (FIGURE 2).28 As above, the Mayo Clinic Hallbeck Human Factors Engineering Laboratories has a publicly available “OR-Stretch Between Surgery Stretches Video” in which the surgeon is guided through several short stretches that are done in a seated position, including stretches for the hamstring, lower back, and arms (FIGURE 3).43

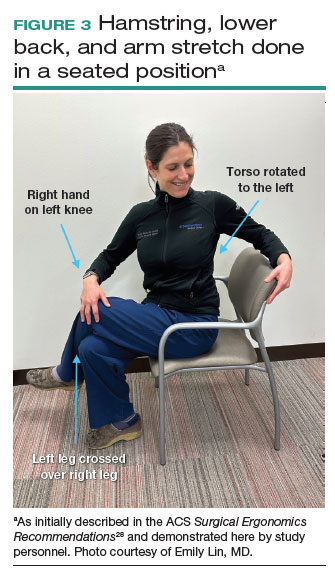

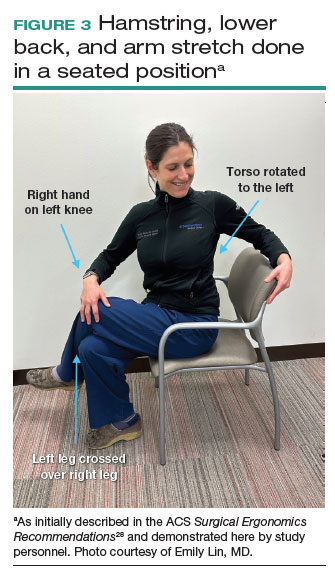

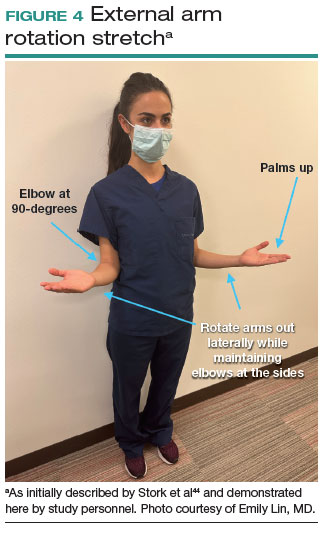

Many of the above-mentioned stretches were designed for use in the context of open, laparoscopic, or robotic surgery. For the vaginal surgeon, the intraoperative ergonomic stressors differ from those of other routes of surgery, and thus stretches tailored to the positioning during vaginal surgery are necessary. In a video recently published by the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, several stretches are reviewed that target high-risk positions often held by the surgeon or assistant when operating vaginally.44 These stretches include cervical retraction, thoracic extension, external arm rotation, cervical side bending, and lumbar extension (FIGURE 4).44 The recommendation is to complete these exercises 2 times per day, with 8 to 10 repetitions per set.44

Prioritizing ergonomic awareness and training

As caregivers, it is not uncommon for us to prioritize the needs of others before those of ourselves. However, WMSDs are prevalent, and their downstream effects may cause catastrophic professional and personal losses. Cumulatively, the global impact of WMSDs is a significant issue for the health care workforce and its longevity.

To prevent WMSDs, it is imperative that surgeons are aware of the factors that contribute to injury development and the appropriate, accessible modifications for these factors. While each surgical modality confers its own ergonomic challenges, these risks can be mitigated through increased awareness of OR setup, surgeon positioning, and incorporation of microbreaks and stretching exercises during and after surgical procedures.

Formal training in surgical ergonomics is lacking across specialties, including gynecology.45 Multiple educational interventions have been proposed and studied to help fill this training gap.30,46-49When used, these interventions have been associated with increased knowledge of surgical ergonomic principles or reduction in surgeon pain scores, including trainees.50 As we become more cognizant of WMSDs, standardized resident curricula should be developed in an effort to reduce the prevalence of these potentially career-ending injuries.

In addition to education, cultivating a culture in which ergonomics is prioritized is essential. Although most surgeons report work-related pain, very few report their injuries to occupational health. For example, while 29% of gynecologic oncologists reported seeking treatment for a WMSD, only 1% had reported their injury to their employer.5 In a study of ACS members, only 19% of injuries were reported, 30% of surgeons stated that they did not know how to report an injury, and 21% felt that the resources for surgeons during and after an injury were inadequate.6

As we prioritize the health and safety of our patients, we also need to promote ergonomic awareness in the OR, respect the need for accommodations, encourage injury reporting, support surgeons who need to take time away for medical treatment, and partner with industry to develop new instruments and technology with effective ergonomic features. ●

- Workplace health glossary. Reviewed February 12, 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/workplacehealthpromotion/tools-resources /glossary/glossary.html#W

- Epstein S, Sparer EH, Tran BN, et al. Prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among surgeons and interventionalists: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:e174947.

- Yurteri-Kaplan LA, Park AJ. Surgical ergonomics and preventing workrelated musculoskeletal disorders. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:455-462.

- Symer MM, Keller DS. Human factors in pelvic surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2022;48:2346-2351.

- Franasiak J, Ko EM, Kidd J, et al. Physical strain and urgent need for ergonomic training among gynecologic oncologists who perform minimally invasive surgery. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;126:437-442.

- Davis WT, Fletcher SA, Guillamondegui OD. Musculoskeletal occupational injury among surgeons: effects for patients, providers, and institutions. J Surg Res. 2014;189:207-212.e6.

- Fox M. Surgeons face unique ergonomic challenges. American College of Surgeons. September 1, 2022. Accessed May 22, 2023. https://www.facs.org/for-medical-professionals/news-publications /news-and-articles/bulletin/september-2022-volume-107-issue-9 /surgeons-face-unique-ergonomic-challenges/

- Wong JMK, Carey ET, King C, et al. A call to action for ergonomic surgical devices designed for diverse surgeon end users. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:463-466.

- IHS Inc. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2014 to 2025. Association of American Medical Colleges. April 5, 2016.

- Kim-Fine S, Woolley SM, Weaver AL, et al. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among vaginal surgeons. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1191-1200.

- Sers R, Forrester S, Zecca M, et al. The ergonomic impact of patient body mass index on surgeon posture during simulated laparoscopy. Appl Ergon. 2021;97:103501.

- Moss EL, Sarhanis P, Ind T, et al. Impact of obesity on surgeon ergonomics in robotic and straight-stick laparoscopic surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:1063-1069.

- Sutton E, Irvin M, Zeigler C, et al. The ergonomics of women in surgery. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1051-1055.

- Berguer R, Hreljac A. The relationship between hand size and difficulty using surgical instruments: a survey of 726 laparoscopic surgeons. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:508-512.

- Bellini MI, Amabile MI, Saullo P, et al. A woman’s place is in theatre, but are theatres designed with women in mind? A systematic review of ergonomics for women in surgery. J Clin Med. 2022;11:3496.

- Wong JMK, Moore KJ, Lewis P, et al. Ergonomic assessment of surgeon characteristics and laparoscopic device strain in gynecologic surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2022;29:1357-1363.

- Aitchison LP, Cui CK, Arnold A, et al. The ergonomics of laparoscopic surgery: a quantitative study of the time and motion of laparoscopic surgeons in live surgical environments. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:5068-5076.

- Stewart C, Raoof M, Fong Y, et al. Who is hurting? A prospective study of surgeon ergonomics. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:292-299.

- Green SV, Morris DE, Naumann DN, et al. One size does not fit all: impact of hand size on ease of use of instruments for minimally invasive surgery. Surgeon. 2022;S1479-666X(22)00131-7.

- Matern U, Faist M, Kehl K, et al. Monitor position in laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:436-440.

- Berguer R, Rab GT, Abu-Ghaida H, et al. A comparison of surgeons’ posture during laparoscopic and open surgical procedures. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:139-142.

- Athanasiadis DI, Monfared S, Asadi H, et al. An analysis of the ergonomic risk of surgical trainees and experienced surgeons during laparoscopic procedures. Surgery. 2021;169:496-501.

- Hotton J, Bogart E, Le Deley MC, et al. Ergonomic assessment of the surgeon’s physical workload during robot-assisted versus standard laparoscopy in a French multicenter randomized trial (ROBOGYN-1004 Trial). Ann Surg Oncol. 2023;30:916-923.

- Plerhoples TA, Hernandez-Boussard T, Wren SM. The aching surgeon: a survey of physical discomfort and symptoms following open, laparoscopic, and robotic surgery. J Robot Surg. 2012;6:65-72.

- Lee GI, Lee MR, Green I, et al. Surgeons’ physical discomfort and symptoms during robotic surgery: a comprehensive ergonomic survey study. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:1697-1706.

- McDonald ME, Ramirez PT, Munsell MF, et al. Physician pain and discomfort during minimally invasive gynecologic cancer surgery. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;134:243-247.

- Zhu X, Yurteri-Kaplan LA, Gutman RE, et al. Postural stress experienced by vaginal surgeons. Proc Hum Factors Ergonomics Soc Annu Meet. 2014;58:763-767.

- American College of Surgeons Division of Education and Surgical Ergonomics Committee. Surgical Ergonomics Recommendations. ACS Education. 2022.

- Cardenas-Trowers O, Kjellsson K, Hatch K. Ergonomics: making the OR a comfortable place. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:1065-1066.

- Hokenstad ED, Hallbeck MS, Lowndes BR, et al. Ergonomic robotic console configuration in gynecologic surgery: an interventional study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:850-859.

- Singh R, Yurteri-Kaplan LA, Morrow MM, et al. Sitting versus standing makes a difference in musculoskeletal discomfort and postural load for surgeons performing vaginal surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:231-237.

- Hullfish KL, Trowbridge ER, Bodine G. Ergonomics and gynecologic surgery: “surgeon protect thyself.” J Pelvic Med Surg. 2009;15:435-439.

- Woodburn KL, Kho RM. Vaginal surgery: don’t get bent out of shape. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:762-763.

- Hobson DTG, Meriwether KV, Gaskins JT, et al. Learner satisfaction and experience with a high-definition telescopic camera during vaginal procedures: a randomized controlled trial. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27:105-111.

- Speed G, Harris K, Keegel T. The effect of cushioning materials on musculoskeletal discomfort and fatigue during prolonged standing at work: a systematic review. Appl Ergon. 2018;70:300-334.

- Haramis G, Rosales JC, Palacios JM, et al. Prospective randomized evaluation of FOOT gel pads for operating room staff COMFORT during laparoscopic renal surgery. Urology. 2010;76:1405-1408.

- Voss RK, Chiang YJ, Cromwell KD, et al. Do no harm, except to ourselves? A survey of symptoms and injuries in oncologic surgeons and pilot study of an intraoperative ergonomic intervention. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;224:16-25.e1.

- Marquetand J, Gabriel J, Seibt R, et al. Ergonomics for surgeons—prototype of an external surgeon support system reduces muscular activity and fatigue. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2021;60:102586.

- Tetteh E, Hallbeck MS, Mirka GA. Effects of passive exoskeleton support on EMG measures of the neck, shoulder and trunk muscles while holding simulated surgical postures and performing a simulated surgical procedure. Appl Ergon. 2022;100:103646.

- Lim AK, Ryu J, Yoon HM, et al. Ergonomic effects of medical augmented reality glasses in video-assisted surgery. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:988-998.

- Park AE, Zahiri HR, Hallbeck MS, et al. Intraoperative “micro breaks” with targeted stretching enhance surgeon physical function and mental focus: a multicenter cohort study. Ann Surg. 2017;265:340-346.

- Hallbeck MS, Lowndes BR, Bingener J, et al. The impact of intraoperative microbreaks with exercises on surgeons: a multi-center cohort study. Appl Ergon. 2017;60:334-341.

- Hallbeck Human Factors Engineering Laboratories. OR Stretch Videos. Mayo Clinic, 2018. Accessed May 19, 2023. https://www.mayo .edu/research/labs/human-factors-engineering/or-stretch /or-stretch-videos

- Stork A, Bacon T, Corton M. Prevention of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders in Vaginal Surgery. Video presentation at: Society of Gynecologic Surgeons’ Annual Scientific Meeting 2023, Tucson, AZ. Accessed April 3, 2023. https://sgs.eng.us/category.php?cat=2023 -video-presentations

- Aaron KA, Vaughan J, Gupta R, et al. The risk of ergonomic injury across surgical specialties. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0244868.

- Smith TG, Lowndes BR, Schmida E, et al. Course design and learning outcomes of a practical online ergonomics course for surgical residents. J Surg Educ. 2022;79:1489-1499.

- Franasiak J, Craven R, Mosaly P, et al. Feasibility and acceptance of a robotic surgery ergonomic training program. JSLS. 2014;18:e2014.00166.

- Cerier E, Hu A, Goldring A, et al. Ergonomics workshop improves musculoskeletal symptoms in general surgery residents. J Surg Res. 2022;280:567-574.

- Giagio S, Volpe G, Pillastrini P, et al. A preventive program for workrelated musculoskeletal disorders among surgeons: outcomes of a randomized controlled clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2019;270:969-975.

- Jensen MJ, Liao J, Van Gorp B, et al. Incorporating surgical ergonomics education into surgical residency curriculum. J Surg Educ. 2021;78:1209-1215.

Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs) are “musculoskeletal disorders (injuries or disorders of the muscles, nerves, tendons, joints, cartilage, and spinal discs) in which the work environment and performance of work contribute significantly to the condition; and/or the condition is made worse or persists longer due to work conditions.”1 The health care industry has one of the highest rates of WMSDs, even when compared with traditional labor-intensive occupations, such as coal mining. In 2017, the health care industry reported more than a half million incidents of work-related injury and illness.2,3 In particular, surgeons are at increased risk for WMSDs, since they repetitively perform the classic tenets of poor ergonomics, including operating in static, extreme, and awkward positions and for prolonged periods of time.3

Gynecologic surgeons face unique ergonomic challenges. Operating in the pelvis requires an oblique approach that adds complexity and inhibits appropriate ergonomic positioning.4 All modalities of surgery incur their own challenges and risks to the surgeon, including minimally invasive gynecologic surgery (MIGS), which has become the standard of care for most conditions. Although MIGS has several benefits for the patient, a survey of gynecologic oncologists found that 88% of respondents reported discomfort related to MIGS.5 Several factors contribute to the development of WMSDs in surgery, including lack of ergonomic awareness, suboptimal ergonomic education and training,5,6 and ergonomically poor operating room (OR) equipment and instrument design.7 Furthermore, surgical culture does not generally prioritize ergonomics in the OR or requests for ergonomic accommodations.7,8

Within 5 years, a physician workforce shortage is projected for the United States.9 WMSDs contribute to workforce issues as they are associated with decreased productivity; time off needed for pain and treatment, including short-term disability; and possibly early retirement (as those who are older and have more work experience may be more likely to seek medical attention).10 In a 2013 study of vaginal surgeons, 14% missed work; 21% modified their work hours, work type, or amount of surgery; and 29% modified their surgical technique because of injury.10 Work-related pain also can negatively affect mental health, sleep, relationships, and quality of life.6

Recently, awareness has increased regarding WMSDs and their consequences, which has led to significant strides in the study of ergonomics among surgeons, a growing body of research on the topic, and guidance for optimizing ergonomics in the OR.

Risk factors for ergonomic strain

Several factors contribute to ergonomic strain and, subsequently, the development of WMSDs. Recognizing these factors can direct strategies for injury prevention.

Patient factors

The prevalence of obesity in the United States increased from 30.5% in 1999–2000 to 41.9% between 2017 and 2020.11 As the average patient’s body mass index (BMI) has increased, there is concern for a parallel increase in the ergonomic strain on laparoscopic surgeons.

A study of simulated laparoscopic tasks at varying model BMI levels demonstrated increased surgeon postural stress and workload at higher model BMIs (50 kg/m2) when compared with lower model BMIs (20 and 30 kg/m2).11 This result was supported in another study, which demonstrated both increased muscle activity and increased time needed to complete a surgical task with laparoscopic surgery; interestingly, when the same study measured these parameters for robotic surgery, this association was not seen.12 This suggests that a robotic rather than a laparoscopic approach may avoid some of the ergonomic strain associated with increased patient BMI.

Continue to: Surgeon factors...

Surgeon factors

Various surgeon characteristics have been shown to influence ergonomics in the OR. Surgeons with smaller hand sizes, for example, reported greater physical discomfort and demonstrated greater ergonomic workload when operating laparoscopically.13-15 In particular, those with a glove size of 6.5 or smaller have more difficulty using laparoscopic instruments, and those with a glove size smaller than 7 demonstrate a larger decline in grip strength when using laparoscopic instruments repeatedly.14,16

Surgeon height also can affect the amount of time spent in high-risk, nonergonomic positions. In a study that evaluated video recordings of surgeon posture during gynecologic laparoscopy, shorter surgeons were noted to use greater degrees of neck rotation to look at the monitor.17 Furthermore, surgeons with shorter arm lengths experienced more “extreme positions” of the nondominant shoulder and elbow.17 This trend also was seen in open and robotic surgery, where surgeons with a height of 66 cm or less reported increased pain scores after operating.18

Surgical instruments and OR setup

Surgical instrument characteristics can contribute to ergonomic strain, especially when the instruments have been designed with a one-size-fits-all mentality.8,19 In an examination of the anthropometric measurements of surgeon hand sizes and their correlation with difficulty when using a “standard” laparoscopic instrument, surgeons with smaller finger and hand spans had trouble using these instruments.19 Another study compared surgeon grip strength and ergonomic workloads after using 3 laparoscopic advanced bipolar instruments.16 Gender and hand size aside, the authors found that use of several of the laparoscopic devices led to greater decline in grip strength.16

The setup of the OR also can have a profound effect on the surgeon’s ergonomics. Monitor placement, for example, is crucial to ergonomic success. One study found that positioning the monitor directly in front of the surgeon at eye level was associated with the lowest neck muscle activity during a simulated task.20

Route of surgery

Each surgical approach has intrinsic ergonomic risks. With laparoscopy, surgeons often remain in straight head and back positions without much trunk motion, especially when compared with open surgery.21 In one study, laparoscopic surgeons spent more than 60% of a case in a static position and more than 80% of a case in a high-risk, “demanding” neck position.22

Robotic surgery, in contrast to laparoscopy, often has been cited as being more “ergonomic.” While robotic surgery has less of an effect on the neck, shoulders, arms, and legs than laparoscopy23 and often is associated with less physical discomfort than either open or laparoscopic surgery,23,24 robotic surgery still maintains its own innate ergonomic risks. Of robotic surgeons surveyed, 56.1% reported neck stiffness, finger fatigue, and eye symptoms in one study.25 In another survey study, more robotic surgeons (72%) reported physical symptoms than laparoscopic (57%) and open (49%) surgeons.26Vaginal surgery also puts surgeons at ergonomic risk. A majority of surgeons (87.2%) who completed more than 50% of their cases vaginally reported a history of WMSDs.10 Vaginal surgery places surgeons in awkward positions of the neck, shoulder, and trunk frequently and for longer durations.27

Continue to: Strategies for preventing WMSDs...

Strategies for preventing WMSDs

As factors that contribute to the development of WMSDs are identified, preventive strategies can be targeted to these individual factors. Research has focused on appropriate setup of the OR, surgeon posture, intraoperative microbreaks, and stretching both in and outside of the OR.

1. OR setup and positioning of the surgeon by MIGS route

The route of MIGS affects OR setup and surgeon posture. Ergonomic recommendations for laparoscopy, robotic surgery, and vaginal surgery are all unique to the risks posed by each particular approach.

Laparoscopic surgery. Laparoscopic monitors should face the surgeon directly, with the screen just below eye level to maintain the surgeon’s neck in a neutral position.28 The table height should be set for the tallest surgeon, and shorter surgeons should stand on steps as needed.28 The table height also should allow for the surgeon’s hands to be at elbow height, with the elbows bent at 90 degrees with the wrists straight.29 Foot pedals should be placed at the surgeons’ foot level and should be reached easily.28 Additionally, the patient’s arms should be tucked at their sides to allow surgeons a larger operative space.29 When using laparoscopic instruments, locking and ratcheting features should be used whenever possible to reduce prolonged grip or squeeze forces.28 The laparoscopic camera should be held in the palm with the wrist in a neutral position.29

Robotic surgery. Positioning and setup of the robotic console is a main focus of ergonomic recommendations. The surgeon’s chair should be brought as close to the console as possible, and the knees positioned in a 90-degree angle.30 The foot pedals should be brought toward the surgeon to maintain this angle of the knees.30 The console should be rotated toward the surgeon and then the height adjusted so that the surgeon can look through the eyepiece while sitting upright and can maintain the neck in a neutral position.28,30 The surgeon’s forehead should rest comfortably on the headrest.29 The forearms should rest on the armrest while the arms are maintained in a neutral position and the shoulders remain relaxed while the surgeon holds the robotic controls.30 It is important to utilize the armrest often to relieve stress on the arm while operating.28 Frequent use of the clutch function can keep the robotic controls in the center of the workspace.28

Vaginal surgery. Both seated and standing positions are associated with high-risk positioning of the trunk and bilateral shoulders, respectively, in vaginal surgery.31 However, surgeons who stand while operating vaginally reported more discomfort in the bilateral wrists, thighs, and lower legs than those who operated while seated.31 This suggests a potential ergonomic advantage to the seated position for vaginal surgery. Chair height should be adjusted so the surgeon can look straight ahead with the neck in a neutral position.32 Surgeons should consider using a headlamp, as this may prevent repetitive awkward movements to adjust overhead lights.32 For standing surgery, the table height should be adjusted for the tallest surgeon, and shorter surgeons or assistants should use steps as needed.3

Surgical assistants should switch sides during the course of the case to avoid excessive unilateral upper-extremity strain.32 The addition of a table-mounted vaginal retractor system may be useful in relieving physical strain for surgical assistants, but data currently are lacking to demonstrate this ergonomic benefit.33 Further studies are needed, especially since many surgeons take on the role of surgical assist in the teaching environment and subsequently report more WMSDs than their colleagues who do not work in teaching environments.10,34

2. Pain relief from individual ergonomic positioning devices

Apart from adjusting how the OR equipment is arranged or how the surgeons adjust their positioning, several devices that assist with surgeon positioning—including gel mats or insoles, exoskeletons, and “augmented reality” glasses—are being studied.

The use of gel mats or insoles in the OR has mixed evidence in the literature.35-37

Exoskeletons, external devices that support a surgeon’s posture and positioning, have been studied thus far in simulated nonsterile surgical environments. Preliminarily, it appears that use of an exoskeleton can decrease muscle activity and time spent in static positions, with a reported decrease in post-task user discomfort.38,39 More data are needed to determine if exoskeletons can be used in the sterile setting and for longer durations as may occur in actual OR cases.

Augmented reality glasses project the laparoscopic monitor image to the glasses, which frees the surgeon to place the “monitor” in a more neutral, ergonomic position. In one study, use of augmented reality glasses was associated with decreased muscle activity and a reduction in Rapid Entire Body Assessment (REBA) scores when compared with use of the conventional laparoscopic monitor.40More data are needed on these emerging technologies to determine whether adverse effects occur with prolonged use.

Continue to: 3. Implementing intraoperative microbreaks and stretching...

3. Implementing intraoperative microbreaks and stretching

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) recommends that surgeons avoid prolonged static postures during procedures.28 One strategy for preventing sustained positioning is to incorporate breaks with associated stretching routinely during surgery.28

Microbreaks. In a landmark study by Park and colleagues in 2017, 120-second long targeted stretching microbreaks (TSMBs) were completed every 20 to 40 minutes during a surgery, and results demonstrated improved postoperative surgeon pain scores without an associated increase in the length of the case.41 These surgeons reported improved pain in the neck, bilateral shoulders, bilateral hands, and lower back. Eighty-eight percent of surgeons reported either improvement or “no change” in their mental focus, and 100% reported improvement or “no change” in their physical performance after TSMBs were implemented.42 Of surveyed surgeons, 87% wanted TSMBs incorporated routinely.41,42

Stretches. Multiple resources, such as the ACS and the Mayo Clinic, for intraoperative stretches are available. The ACS recommends performing neck and shoulder stretches during intraoperative microbreaks, including a range-of-movement neck exercise, deep cervical flexor training, and standing scapular retraction.28 The ACS also demonstrates lumbrical stretches for the fingers and passive wrist extension exercises to be used intraoperatively (or between cases) (FIGURE 1).28 The Mayo Clinic Hallbeck Human Factors Engineering Laboratories has a publicly available “OR Stretch Instructional Video” in which the surgeon is guided through several different short stretches, including shoulder shrugging and side bends, that can be used during surgery.43

Both the ACS and the Mayo Clinic provide examples of pertinent stretch exercises for use when not in the sterile environment, between cases or after cases are complete. The ACS recommends several neck and shoulder stretches for the trapezius, levator scapulae, and pectoralis and recommends the use of a foam roller to improve thoracic mobility (FIGURE 2).28 As above, the Mayo Clinic Hallbeck Human Factors Engineering Laboratories has a publicly available “OR-Stretch Between Surgery Stretches Video” in which the surgeon is guided through several short stretches that are done in a seated position, including stretches for the hamstring, lower back, and arms (FIGURE 3).43

Many of the above-mentioned stretches were designed for use in the context of open, laparoscopic, or robotic surgery. For the vaginal surgeon, the intraoperative ergonomic stressors differ from those of other routes of surgery, and thus stretches tailored to the positioning during vaginal surgery are necessary. In a video recently published by the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, several stretches are reviewed that target high-risk positions often held by the surgeon or assistant when operating vaginally.44 These stretches include cervical retraction, thoracic extension, external arm rotation, cervical side bending, and lumbar extension (FIGURE 4).44 The recommendation is to complete these exercises 2 times per day, with 8 to 10 repetitions per set.44

Prioritizing ergonomic awareness and training

As caregivers, it is not uncommon for us to prioritize the needs of others before those of ourselves. However, WMSDs are prevalent, and their downstream effects may cause catastrophic professional and personal losses. Cumulatively, the global impact of WMSDs is a significant issue for the health care workforce and its longevity.

To prevent WMSDs, it is imperative that surgeons are aware of the factors that contribute to injury development and the appropriate, accessible modifications for these factors. While each surgical modality confers its own ergonomic challenges, these risks can be mitigated through increased awareness of OR setup, surgeon positioning, and incorporation of microbreaks and stretching exercises during and after surgical procedures.

Formal training in surgical ergonomics is lacking across specialties, including gynecology.45 Multiple educational interventions have been proposed and studied to help fill this training gap.30,46-49When used, these interventions have been associated with increased knowledge of surgical ergonomic principles or reduction in surgeon pain scores, including trainees.50 As we become more cognizant of WMSDs, standardized resident curricula should be developed in an effort to reduce the prevalence of these potentially career-ending injuries.

In addition to education, cultivating a culture in which ergonomics is prioritized is essential. Although most surgeons report work-related pain, very few report their injuries to occupational health. For example, while 29% of gynecologic oncologists reported seeking treatment for a WMSD, only 1% had reported their injury to their employer.5 In a study of ACS members, only 19% of injuries were reported, 30% of surgeons stated that they did not know how to report an injury, and 21% felt that the resources for surgeons during and after an injury were inadequate.6

As we prioritize the health and safety of our patients, we also need to promote ergonomic awareness in the OR, respect the need for accommodations, encourage injury reporting, support surgeons who need to take time away for medical treatment, and partner with industry to develop new instruments and technology with effective ergonomic features. ●

Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs) are “musculoskeletal disorders (injuries or disorders of the muscles, nerves, tendons, joints, cartilage, and spinal discs) in which the work environment and performance of work contribute significantly to the condition; and/or the condition is made worse or persists longer due to work conditions.”1 The health care industry has one of the highest rates of WMSDs, even when compared with traditional labor-intensive occupations, such as coal mining. In 2017, the health care industry reported more than a half million incidents of work-related injury and illness.2,3 In particular, surgeons are at increased risk for WMSDs, since they repetitively perform the classic tenets of poor ergonomics, including operating in static, extreme, and awkward positions and for prolonged periods of time.3

Gynecologic surgeons face unique ergonomic challenges. Operating in the pelvis requires an oblique approach that adds complexity and inhibits appropriate ergonomic positioning.4 All modalities of surgery incur their own challenges and risks to the surgeon, including minimally invasive gynecologic surgery (MIGS), which has become the standard of care for most conditions. Although MIGS has several benefits for the patient, a survey of gynecologic oncologists found that 88% of respondents reported discomfort related to MIGS.5 Several factors contribute to the development of WMSDs in surgery, including lack of ergonomic awareness, suboptimal ergonomic education and training,5,6 and ergonomically poor operating room (OR) equipment and instrument design.7 Furthermore, surgical culture does not generally prioritize ergonomics in the OR or requests for ergonomic accommodations.7,8

Within 5 years, a physician workforce shortage is projected for the United States.9 WMSDs contribute to workforce issues as they are associated with decreased productivity; time off needed for pain and treatment, including short-term disability; and possibly early retirement (as those who are older and have more work experience may be more likely to seek medical attention).10 In a 2013 study of vaginal surgeons, 14% missed work; 21% modified their work hours, work type, or amount of surgery; and 29% modified their surgical technique because of injury.10 Work-related pain also can negatively affect mental health, sleep, relationships, and quality of life.6

Recently, awareness has increased regarding WMSDs and their consequences, which has led to significant strides in the study of ergonomics among surgeons, a growing body of research on the topic, and guidance for optimizing ergonomics in the OR.

Risk factors for ergonomic strain

Several factors contribute to ergonomic strain and, subsequently, the development of WMSDs. Recognizing these factors can direct strategies for injury prevention.

Patient factors

The prevalence of obesity in the United States increased from 30.5% in 1999–2000 to 41.9% between 2017 and 2020.11 As the average patient’s body mass index (BMI) has increased, there is concern for a parallel increase in the ergonomic strain on laparoscopic surgeons.

A study of simulated laparoscopic tasks at varying model BMI levels demonstrated increased surgeon postural stress and workload at higher model BMIs (50 kg/m2) when compared with lower model BMIs (20 and 30 kg/m2).11 This result was supported in another study, which demonstrated both increased muscle activity and increased time needed to complete a surgical task with laparoscopic surgery; interestingly, when the same study measured these parameters for robotic surgery, this association was not seen.12 This suggests that a robotic rather than a laparoscopic approach may avoid some of the ergonomic strain associated with increased patient BMI.

Continue to: Surgeon factors...

Surgeon factors

Various surgeon characteristics have been shown to influence ergonomics in the OR. Surgeons with smaller hand sizes, for example, reported greater physical discomfort and demonstrated greater ergonomic workload when operating laparoscopically.13-15 In particular, those with a glove size of 6.5 or smaller have more difficulty using laparoscopic instruments, and those with a glove size smaller than 7 demonstrate a larger decline in grip strength when using laparoscopic instruments repeatedly.14,16

Surgeon height also can affect the amount of time spent in high-risk, nonergonomic positions. In a study that evaluated video recordings of surgeon posture during gynecologic laparoscopy, shorter surgeons were noted to use greater degrees of neck rotation to look at the monitor.17 Furthermore, surgeons with shorter arm lengths experienced more “extreme positions” of the nondominant shoulder and elbow.17 This trend also was seen in open and robotic surgery, where surgeons with a height of 66 cm or less reported increased pain scores after operating.18

Surgical instruments and OR setup

Surgical instrument characteristics can contribute to ergonomic strain, especially when the instruments have been designed with a one-size-fits-all mentality.8,19 In an examination of the anthropometric measurements of surgeon hand sizes and their correlation with difficulty when using a “standard” laparoscopic instrument, surgeons with smaller finger and hand spans had trouble using these instruments.19 Another study compared surgeon grip strength and ergonomic workloads after using 3 laparoscopic advanced bipolar instruments.16 Gender and hand size aside, the authors found that use of several of the laparoscopic devices led to greater decline in grip strength.16

The setup of the OR also can have a profound effect on the surgeon’s ergonomics. Monitor placement, for example, is crucial to ergonomic success. One study found that positioning the monitor directly in front of the surgeon at eye level was associated with the lowest neck muscle activity during a simulated task.20

Route of surgery

Each surgical approach has intrinsic ergonomic risks. With laparoscopy, surgeons often remain in straight head and back positions without much trunk motion, especially when compared with open surgery.21 In one study, laparoscopic surgeons spent more than 60% of a case in a static position and more than 80% of a case in a high-risk, “demanding” neck position.22

Robotic surgery, in contrast to laparoscopy, often has been cited as being more “ergonomic.” While robotic surgery has less of an effect on the neck, shoulders, arms, and legs than laparoscopy23 and often is associated with less physical discomfort than either open or laparoscopic surgery,23,24 robotic surgery still maintains its own innate ergonomic risks. Of robotic surgeons surveyed, 56.1% reported neck stiffness, finger fatigue, and eye symptoms in one study.25 In another survey study, more robotic surgeons (72%) reported physical symptoms than laparoscopic (57%) and open (49%) surgeons.26Vaginal surgery also puts surgeons at ergonomic risk. A majority of surgeons (87.2%) who completed more than 50% of their cases vaginally reported a history of WMSDs.10 Vaginal surgery places surgeons in awkward positions of the neck, shoulder, and trunk frequently and for longer durations.27

Continue to: Strategies for preventing WMSDs...

Strategies for preventing WMSDs

As factors that contribute to the development of WMSDs are identified, preventive strategies can be targeted to these individual factors. Research has focused on appropriate setup of the OR, surgeon posture, intraoperative microbreaks, and stretching both in and outside of the OR.

1. OR setup and positioning of the surgeon by MIGS route

The route of MIGS affects OR setup and surgeon posture. Ergonomic recommendations for laparoscopy, robotic surgery, and vaginal surgery are all unique to the risks posed by each particular approach.

Laparoscopic surgery. Laparoscopic monitors should face the surgeon directly, with the screen just below eye level to maintain the surgeon’s neck in a neutral position.28 The table height should be set for the tallest surgeon, and shorter surgeons should stand on steps as needed.28 The table height also should allow for the surgeon’s hands to be at elbow height, with the elbows bent at 90 degrees with the wrists straight.29 Foot pedals should be placed at the surgeons’ foot level and should be reached easily.28 Additionally, the patient’s arms should be tucked at their sides to allow surgeons a larger operative space.29 When using laparoscopic instruments, locking and ratcheting features should be used whenever possible to reduce prolonged grip or squeeze forces.28 The laparoscopic camera should be held in the palm with the wrist in a neutral position.29

Robotic surgery. Positioning and setup of the robotic console is a main focus of ergonomic recommendations. The surgeon’s chair should be brought as close to the console as possible, and the knees positioned in a 90-degree angle.30 The foot pedals should be brought toward the surgeon to maintain this angle of the knees.30 The console should be rotated toward the surgeon and then the height adjusted so that the surgeon can look through the eyepiece while sitting upright and can maintain the neck in a neutral position.28,30 The surgeon’s forehead should rest comfortably on the headrest.29 The forearms should rest on the armrest while the arms are maintained in a neutral position and the shoulders remain relaxed while the surgeon holds the robotic controls.30 It is important to utilize the armrest often to relieve stress on the arm while operating.28 Frequent use of the clutch function can keep the robotic controls in the center of the workspace.28

Vaginal surgery. Both seated and standing positions are associated with high-risk positioning of the trunk and bilateral shoulders, respectively, in vaginal surgery.31 However, surgeons who stand while operating vaginally reported more discomfort in the bilateral wrists, thighs, and lower legs than those who operated while seated.31 This suggests a potential ergonomic advantage to the seated position for vaginal surgery. Chair height should be adjusted so the surgeon can look straight ahead with the neck in a neutral position.32 Surgeons should consider using a headlamp, as this may prevent repetitive awkward movements to adjust overhead lights.32 For standing surgery, the table height should be adjusted for the tallest surgeon, and shorter surgeons or assistants should use steps as needed.3

Surgical assistants should switch sides during the course of the case to avoid excessive unilateral upper-extremity strain.32 The addition of a table-mounted vaginal retractor system may be useful in relieving physical strain for surgical assistants, but data currently are lacking to demonstrate this ergonomic benefit.33 Further studies are needed, especially since many surgeons take on the role of surgical assist in the teaching environment and subsequently report more WMSDs than their colleagues who do not work in teaching environments.10,34

2. Pain relief from individual ergonomic positioning devices

Apart from adjusting how the OR equipment is arranged or how the surgeons adjust their positioning, several devices that assist with surgeon positioning—including gel mats or insoles, exoskeletons, and “augmented reality” glasses—are being studied.

The use of gel mats or insoles in the OR has mixed evidence in the literature.35-37

Exoskeletons, external devices that support a surgeon’s posture and positioning, have been studied thus far in simulated nonsterile surgical environments. Preliminarily, it appears that use of an exoskeleton can decrease muscle activity and time spent in static positions, with a reported decrease in post-task user discomfort.38,39 More data are needed to determine if exoskeletons can be used in the sterile setting and for longer durations as may occur in actual OR cases.

Augmented reality glasses project the laparoscopic monitor image to the glasses, which frees the surgeon to place the “monitor” in a more neutral, ergonomic position. In one study, use of augmented reality glasses was associated with decreased muscle activity and a reduction in Rapid Entire Body Assessment (REBA) scores when compared with use of the conventional laparoscopic monitor.40More data are needed on these emerging technologies to determine whether adverse effects occur with prolonged use.

Continue to: 3. Implementing intraoperative microbreaks and stretching...

3. Implementing intraoperative microbreaks and stretching

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) recommends that surgeons avoid prolonged static postures during procedures.28 One strategy for preventing sustained positioning is to incorporate breaks with associated stretching routinely during surgery.28

Microbreaks. In a landmark study by Park and colleagues in 2017, 120-second long targeted stretching microbreaks (TSMBs) were completed every 20 to 40 minutes during a surgery, and results demonstrated improved postoperative surgeon pain scores without an associated increase in the length of the case.41 These surgeons reported improved pain in the neck, bilateral shoulders, bilateral hands, and lower back. Eighty-eight percent of surgeons reported either improvement or “no change” in their mental focus, and 100% reported improvement or “no change” in their physical performance after TSMBs were implemented.42 Of surveyed surgeons, 87% wanted TSMBs incorporated routinely.41,42

Stretches. Multiple resources, such as the ACS and the Mayo Clinic, for intraoperative stretches are available. The ACS recommends performing neck and shoulder stretches during intraoperative microbreaks, including a range-of-movement neck exercise, deep cervical flexor training, and standing scapular retraction.28 The ACS also demonstrates lumbrical stretches for the fingers and passive wrist extension exercises to be used intraoperatively (or between cases) (FIGURE 1).28 The Mayo Clinic Hallbeck Human Factors Engineering Laboratories has a publicly available “OR Stretch Instructional Video” in which the surgeon is guided through several different short stretches, including shoulder shrugging and side bends, that can be used during surgery.43

Both the ACS and the Mayo Clinic provide examples of pertinent stretch exercises for use when not in the sterile environment, between cases or after cases are complete. The ACS recommends several neck and shoulder stretches for the trapezius, levator scapulae, and pectoralis and recommends the use of a foam roller to improve thoracic mobility (FIGURE 2).28 As above, the Mayo Clinic Hallbeck Human Factors Engineering Laboratories has a publicly available “OR-Stretch Between Surgery Stretches Video” in which the surgeon is guided through several short stretches that are done in a seated position, including stretches for the hamstring, lower back, and arms (FIGURE 3).43

Many of the above-mentioned stretches were designed for use in the context of open, laparoscopic, or robotic surgery. For the vaginal surgeon, the intraoperative ergonomic stressors differ from those of other routes of surgery, and thus stretches tailored to the positioning during vaginal surgery are necessary. In a video recently published by the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, several stretches are reviewed that target high-risk positions often held by the surgeon or assistant when operating vaginally.44 These stretches include cervical retraction, thoracic extension, external arm rotation, cervical side bending, and lumbar extension (FIGURE 4).44 The recommendation is to complete these exercises 2 times per day, with 8 to 10 repetitions per set.44

Prioritizing ergonomic awareness and training

As caregivers, it is not uncommon for us to prioritize the needs of others before those of ourselves. However, WMSDs are prevalent, and their downstream effects may cause catastrophic professional and personal losses. Cumulatively, the global impact of WMSDs is a significant issue for the health care workforce and its longevity.

To prevent WMSDs, it is imperative that surgeons are aware of the factors that contribute to injury development and the appropriate, accessible modifications for these factors. While each surgical modality confers its own ergonomic challenges, these risks can be mitigated through increased awareness of OR setup, surgeon positioning, and incorporation of microbreaks and stretching exercises during and after surgical procedures.

Formal training in surgical ergonomics is lacking across specialties, including gynecology.45 Multiple educational interventions have been proposed and studied to help fill this training gap.30,46-49When used, these interventions have been associated with increased knowledge of surgical ergonomic principles or reduction in surgeon pain scores, including trainees.50 As we become more cognizant of WMSDs, standardized resident curricula should be developed in an effort to reduce the prevalence of these potentially career-ending injuries.

In addition to education, cultivating a culture in which ergonomics is prioritized is essential. Although most surgeons report work-related pain, very few report their injuries to occupational health. For example, while 29% of gynecologic oncologists reported seeking treatment for a WMSD, only 1% had reported their injury to their employer.5 In a study of ACS members, only 19% of injuries were reported, 30% of surgeons stated that they did not know how to report an injury, and 21% felt that the resources for surgeons during and after an injury were inadequate.6

As we prioritize the health and safety of our patients, we also need to promote ergonomic awareness in the OR, respect the need for accommodations, encourage injury reporting, support surgeons who need to take time away for medical treatment, and partner with industry to develop new instruments and technology with effective ergonomic features. ●

- Workplace health glossary. Reviewed February 12, 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/workplacehealthpromotion/tools-resources /glossary/glossary.html#W

- Epstein S, Sparer EH, Tran BN, et al. Prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among surgeons and interventionalists: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:e174947.

- Yurteri-Kaplan LA, Park AJ. Surgical ergonomics and preventing workrelated musculoskeletal disorders. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:455-462.

- Symer MM, Keller DS. Human factors in pelvic surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2022;48:2346-2351.

- Franasiak J, Ko EM, Kidd J, et al. Physical strain and urgent need for ergonomic training among gynecologic oncologists who perform minimally invasive surgery. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;126:437-442.

- Davis WT, Fletcher SA, Guillamondegui OD. Musculoskeletal occupational injury among surgeons: effects for patients, providers, and institutions. J Surg Res. 2014;189:207-212.e6.

- Fox M. Surgeons face unique ergonomic challenges. American College of Surgeons. September 1, 2022. Accessed May 22, 2023. https://www.facs.org/for-medical-professionals/news-publications /news-and-articles/bulletin/september-2022-volume-107-issue-9 /surgeons-face-unique-ergonomic-challenges/

- Wong JMK, Carey ET, King C, et al. A call to action for ergonomic surgical devices designed for diverse surgeon end users. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:463-466.

- IHS Inc. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2014 to 2025. Association of American Medical Colleges. April 5, 2016.

- Kim-Fine S, Woolley SM, Weaver AL, et al. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among vaginal surgeons. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1191-1200.

- Sers R, Forrester S, Zecca M, et al. The ergonomic impact of patient body mass index on surgeon posture during simulated laparoscopy. Appl Ergon. 2021;97:103501.

- Moss EL, Sarhanis P, Ind T, et al. Impact of obesity on surgeon ergonomics in robotic and straight-stick laparoscopic surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:1063-1069.

- Sutton E, Irvin M, Zeigler C, et al. The ergonomics of women in surgery. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1051-1055.

- Berguer R, Hreljac A. The relationship between hand size and difficulty using surgical instruments: a survey of 726 laparoscopic surgeons. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:508-512.

- Bellini MI, Amabile MI, Saullo P, et al. A woman’s place is in theatre, but are theatres designed with women in mind? A systematic review of ergonomics for women in surgery. J Clin Med. 2022;11:3496.

- Wong JMK, Moore KJ, Lewis P, et al. Ergonomic assessment of surgeon characteristics and laparoscopic device strain in gynecologic surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2022;29:1357-1363.

- Aitchison LP, Cui CK, Arnold A, et al. The ergonomics of laparoscopic surgery: a quantitative study of the time and motion of laparoscopic surgeons in live surgical environments. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:5068-5076.

- Stewart C, Raoof M, Fong Y, et al. Who is hurting? A prospective study of surgeon ergonomics. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:292-299.

- Green SV, Morris DE, Naumann DN, et al. One size does not fit all: impact of hand size on ease of use of instruments for minimally invasive surgery. Surgeon. 2022;S1479-666X(22)00131-7.

- Matern U, Faist M, Kehl K, et al. Monitor position in laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:436-440.

- Berguer R, Rab GT, Abu-Ghaida H, et al. A comparison of surgeons’ posture during laparoscopic and open surgical procedures. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:139-142.

- Athanasiadis DI, Monfared S, Asadi H, et al. An analysis of the ergonomic risk of surgical trainees and experienced surgeons during laparoscopic procedures. Surgery. 2021;169:496-501.

- Hotton J, Bogart E, Le Deley MC, et al. Ergonomic assessment of the surgeon’s physical workload during robot-assisted versus standard laparoscopy in a French multicenter randomized trial (ROBOGYN-1004 Trial). Ann Surg Oncol. 2023;30:916-923.

- Plerhoples TA, Hernandez-Boussard T, Wren SM. The aching surgeon: a survey of physical discomfort and symptoms following open, laparoscopic, and robotic surgery. J Robot Surg. 2012;6:65-72.

- Lee GI, Lee MR, Green I, et al. Surgeons’ physical discomfort and symptoms during robotic surgery: a comprehensive ergonomic survey study. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:1697-1706.

- McDonald ME, Ramirez PT, Munsell MF, et al. Physician pain and discomfort during minimally invasive gynecologic cancer surgery. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;134:243-247.

- Zhu X, Yurteri-Kaplan LA, Gutman RE, et al. Postural stress experienced by vaginal surgeons. Proc Hum Factors Ergonomics Soc Annu Meet. 2014;58:763-767.

- American College of Surgeons Division of Education and Surgical Ergonomics Committee. Surgical Ergonomics Recommendations. ACS Education. 2022.

- Cardenas-Trowers O, Kjellsson K, Hatch K. Ergonomics: making the OR a comfortable place. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:1065-1066.

- Hokenstad ED, Hallbeck MS, Lowndes BR, et al. Ergonomic robotic console configuration in gynecologic surgery: an interventional study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:850-859.

- Singh R, Yurteri-Kaplan LA, Morrow MM, et al. Sitting versus standing makes a difference in musculoskeletal discomfort and postural load for surgeons performing vaginal surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:231-237.

- Hullfish KL, Trowbridge ER, Bodine G. Ergonomics and gynecologic surgery: “surgeon protect thyself.” J Pelvic Med Surg. 2009;15:435-439.

- Woodburn KL, Kho RM. Vaginal surgery: don’t get bent out of shape. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:762-763.

- Hobson DTG, Meriwether KV, Gaskins JT, et al. Learner satisfaction and experience with a high-definition telescopic camera during vaginal procedures: a randomized controlled trial. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27:105-111.

- Speed G, Harris K, Keegel T. The effect of cushioning materials on musculoskeletal discomfort and fatigue during prolonged standing at work: a systematic review. Appl Ergon. 2018;70:300-334.

- Haramis G, Rosales JC, Palacios JM, et al. Prospective randomized evaluation of FOOT gel pads for operating room staff COMFORT during laparoscopic renal surgery. Urology. 2010;76:1405-1408.

- Voss RK, Chiang YJ, Cromwell KD, et al. Do no harm, except to ourselves? A survey of symptoms and injuries in oncologic surgeons and pilot study of an intraoperative ergonomic intervention. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;224:16-25.e1.

- Marquetand J, Gabriel J, Seibt R, et al. Ergonomics for surgeons—prototype of an external surgeon support system reduces muscular activity and fatigue. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2021;60:102586.

- Tetteh E, Hallbeck MS, Mirka GA. Effects of passive exoskeleton support on EMG measures of the neck, shoulder and trunk muscles while holding simulated surgical postures and performing a simulated surgical procedure. Appl Ergon. 2022;100:103646.

- Lim AK, Ryu J, Yoon HM, et al. Ergonomic effects of medical augmented reality glasses in video-assisted surgery. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:988-998.

- Park AE, Zahiri HR, Hallbeck MS, et al. Intraoperative “micro breaks” with targeted stretching enhance surgeon physical function and mental focus: a multicenter cohort study. Ann Surg. 2017;265:340-346.

- Hallbeck MS, Lowndes BR, Bingener J, et al. The impact of intraoperative microbreaks with exercises on surgeons: a multi-center cohort study. Appl Ergon. 2017;60:334-341.

- Hallbeck Human Factors Engineering Laboratories. OR Stretch Videos. Mayo Clinic, 2018. Accessed May 19, 2023. https://www.mayo .edu/research/labs/human-factors-engineering/or-stretch /or-stretch-videos

- Stork A, Bacon T, Corton M. Prevention of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders in Vaginal Surgery. Video presentation at: Society of Gynecologic Surgeons’ Annual Scientific Meeting 2023, Tucson, AZ. Accessed April 3, 2023. https://sgs.eng.us/category.php?cat=2023 -video-presentations

- Aaron KA, Vaughan J, Gupta R, et al. The risk of ergonomic injury across surgical specialties. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0244868.

- Smith TG, Lowndes BR, Schmida E, et al. Course design and learning outcomes of a practical online ergonomics course for surgical residents. J Surg Educ. 2022;79:1489-1499.

- Franasiak J, Craven R, Mosaly P, et al. Feasibility and acceptance of a robotic surgery ergonomic training program. JSLS. 2014;18:e2014.00166.

- Cerier E, Hu A, Goldring A, et al. Ergonomics workshop improves musculoskeletal symptoms in general surgery residents. J Surg Res. 2022;280:567-574.

- Giagio S, Volpe G, Pillastrini P, et al. A preventive program for workrelated musculoskeletal disorders among surgeons: outcomes of a randomized controlled clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2019;270:969-975.

- Jensen MJ, Liao J, Van Gorp B, et al. Incorporating surgical ergonomics education into surgical residency curriculum. J Surg Educ. 2021;78:1209-1215.

- Workplace health glossary. Reviewed February 12, 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/workplacehealthpromotion/tools-resources /glossary/glossary.html#W

- Epstein S, Sparer EH, Tran BN, et al. Prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among surgeons and interventionalists: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:e174947.

- Yurteri-Kaplan LA, Park AJ. Surgical ergonomics and preventing workrelated musculoskeletal disorders. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:455-462.

- Symer MM, Keller DS. Human factors in pelvic surgery. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2022;48:2346-2351.

- Franasiak J, Ko EM, Kidd J, et al. Physical strain and urgent need for ergonomic training among gynecologic oncologists who perform minimally invasive surgery. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;126:437-442.

- Davis WT, Fletcher SA, Guillamondegui OD. Musculoskeletal occupational injury among surgeons: effects for patients, providers, and institutions. J Surg Res. 2014;189:207-212.e6.

- Fox M. Surgeons face unique ergonomic challenges. American College of Surgeons. September 1, 2022. Accessed May 22, 2023. https://www.facs.org/for-medical-professionals/news-publications /news-and-articles/bulletin/september-2022-volume-107-issue-9 /surgeons-face-unique-ergonomic-challenges/

- Wong JMK, Carey ET, King C, et al. A call to action for ergonomic surgical devices designed for diverse surgeon end users. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141:463-466.

- IHS Inc. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2014 to 2025. Association of American Medical Colleges. April 5, 2016.

- Kim-Fine S, Woolley SM, Weaver AL, et al. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among vaginal surgeons. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1191-1200.

- Sers R, Forrester S, Zecca M, et al. The ergonomic impact of patient body mass index on surgeon posture during simulated laparoscopy. Appl Ergon. 2021;97:103501.

- Moss EL, Sarhanis P, Ind T, et al. Impact of obesity on surgeon ergonomics in robotic and straight-stick laparoscopic surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27:1063-1069.

- Sutton E, Irvin M, Zeigler C, et al. The ergonomics of women in surgery. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1051-1055.

- Berguer R, Hreljac A. The relationship between hand size and difficulty using surgical instruments: a survey of 726 laparoscopic surgeons. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:508-512.

- Bellini MI, Amabile MI, Saullo P, et al. A woman’s place is in theatre, but are theatres designed with women in mind? A systematic review of ergonomics for women in surgery. J Clin Med. 2022;11:3496.

- Wong JMK, Moore KJ, Lewis P, et al. Ergonomic assessment of surgeon characteristics and laparoscopic device strain in gynecologic surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2022;29:1357-1363.

- Aitchison LP, Cui CK, Arnold A, et al. The ergonomics of laparoscopic surgery: a quantitative study of the time and motion of laparoscopic surgeons in live surgical environments. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:5068-5076.

- Stewart C, Raoof M, Fong Y, et al. Who is hurting? A prospective study of surgeon ergonomics. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:292-299.

- Green SV, Morris DE, Naumann DN, et al. One size does not fit all: impact of hand size on ease of use of instruments for minimally invasive surgery. Surgeon. 2022;S1479-666X(22)00131-7.

- Matern U, Faist M, Kehl K, et al. Monitor position in laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:436-440.

- Berguer R, Rab GT, Abu-Ghaida H, et al. A comparison of surgeons’ posture during laparoscopic and open surgical procedures. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:139-142.

- Athanasiadis DI, Monfared S, Asadi H, et al. An analysis of the ergonomic risk of surgical trainees and experienced surgeons during laparoscopic procedures. Surgery. 2021;169:496-501.

- Hotton J, Bogart E, Le Deley MC, et al. Ergonomic assessment of the surgeon’s physical workload during robot-assisted versus standard laparoscopy in a French multicenter randomized trial (ROBOGYN-1004 Trial). Ann Surg Oncol. 2023;30:916-923.

- Plerhoples TA, Hernandez-Boussard T, Wren SM. The aching surgeon: a survey of physical discomfort and symptoms following open, laparoscopic, and robotic surgery. J Robot Surg. 2012;6:65-72.

- Lee GI, Lee MR, Green I, et al. Surgeons’ physical discomfort and symptoms during robotic surgery: a comprehensive ergonomic survey study. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:1697-1706.

- McDonald ME, Ramirez PT, Munsell MF, et al. Physician pain and discomfort during minimally invasive gynecologic cancer surgery. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;134:243-247.

- Zhu X, Yurteri-Kaplan LA, Gutman RE, et al. Postural stress experienced by vaginal surgeons. Proc Hum Factors Ergonomics Soc Annu Meet. 2014;58:763-767.

- American College of Surgeons Division of Education and Surgical Ergonomics Committee. Surgical Ergonomics Recommendations. ACS Education. 2022.

- Cardenas-Trowers O, Kjellsson K, Hatch K. Ergonomics: making the OR a comfortable place. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:1065-1066.

- Hokenstad ED, Hallbeck MS, Lowndes BR, et al. Ergonomic robotic console configuration in gynecologic surgery: an interventional study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28:850-859.

- Singh R, Yurteri-Kaplan LA, Morrow MM, et al. Sitting versus standing makes a difference in musculoskeletal discomfort and postural load for surgeons performing vaginal surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:231-237.

- Hullfish KL, Trowbridge ER, Bodine G. Ergonomics and gynecologic surgery: “surgeon protect thyself.” J Pelvic Med Surg. 2009;15:435-439.

- Woodburn KL, Kho RM. Vaginal surgery: don’t get bent out of shape. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:762-763.

- Hobson DTG, Meriwether KV, Gaskins JT, et al. Learner satisfaction and experience with a high-definition telescopic camera during vaginal procedures: a randomized controlled trial. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27:105-111.

- Speed G, Harris K, Keegel T. The effect of cushioning materials on musculoskeletal discomfort and fatigue during prolonged standing at work: a systematic review. Appl Ergon. 2018;70:300-334.

- Haramis G, Rosales JC, Palacios JM, et al. Prospective randomized evaluation of FOOT gel pads for operating room staff COMFORT during laparoscopic renal surgery. Urology. 2010;76:1405-1408.

- Voss RK, Chiang YJ, Cromwell KD, et al. Do no harm, except to ourselves? A survey of symptoms and injuries in oncologic surgeons and pilot study of an intraoperative ergonomic intervention. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;224:16-25.e1.

- Marquetand J, Gabriel J, Seibt R, et al. Ergonomics for surgeons—prototype of an external surgeon support system reduces muscular activity and fatigue. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2021;60:102586.

- Tetteh E, Hallbeck MS, Mirka GA. Effects of passive exoskeleton support on EMG measures of the neck, shoulder and trunk muscles while holding simulated surgical postures and performing a simulated surgical procedure. Appl Ergon. 2022;100:103646.

- Lim AK, Ryu J, Yoon HM, et al. Ergonomic effects of medical augmented reality glasses in video-assisted surgery. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:988-998.