User login

Interstitial Cystitis: A Painful Syndrome

CE/CME No: CR-1307

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

•

Describe the pathophysiology

of interstitial cystitis/bladder

pain syndrome (IC/BPS), as

it is currently understood.

•

Discuss urogenital signs and

symptoms that should prompt suspicion for IC/BPS in a primary care patient.

•

Explain the clinical diagnosis of

IC/BPS and key considerations for referral.

•

Review medical management, nonoperative therapy, and surgical treatment of IC/BPS.

FACULTY

LaToya M. Haynes practices at the Carolinas Pain Institute and the Center for Clinical Research in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and is a preceptor for PA students. Kelly Bilello is a PA at Genitourinary Surgical Consultants in Denver. Jade Breeback practices at Cone Health Primary Care in Kernersville, North Carolina. Jessica Cain is a PA in emergency medicine at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center. Jennifer Wenninger is a cardiothoracic and vascular surgery PA at Bellin Health Care Systems in Green Bay, Wisconsin. M. Jane McDaniel is an Instructor in the Department of Physician Assistant Studies at Wake Forest School of Medicine in Winston-Salem.

The authors have no significant financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Article begins on next page >>

Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) is a common, painful disease of the urinary bladder. Difficult to diagnose and frequently misdiagnosed as another common urologic disorder, IC/BPS challenges health care providers to identify it early and implement current treatment algorithms that may simplify management and improve quality of life for affected patients.

Interstitial cystitis (IC), or bladder pain syndrome (BPS), is a clinical condition characterized by bladder pain, urinary frequency and urgency, and increased nighttime urination (nocturia).1 More specifically, IC/BPS is defined as an unpleasant sensation in the bladder, abdomen, or pelvis (ie, pain, pressure, burning, and/or other discomfort) perceived to be originating in the urinary bladder. The condition is associated with lower urinary tract symptoms of more than six weeks’ duration, with no infection or other identifiable cause present.2

IC/BPS lacks a single known etiology; rather, it most likely results from multiple contributing factors that cascade into a painful and potentially debilitating syndrome. The condition was first described more than a century ago,3,4 but its complex nature and conflicting theories about its pathogenesis present both diagnostic and therapeutic challenges for health care professionals. Frequent misdiagnosis of IC/BPS as another common urologic disorder can make timely, appropriate treatment elusive.

Without a clearly described pathophysiology, IC/BPS has always been difficult to define using standardized diagnostic criteria and precise terminology. The definition of the condition was revised in 2002 and again in 2008, when the nomenclature bladder pain syndrome was introduced.1,5,6

Less than 10 years ago, US researchers described IC as a subgroup of BPS,7 while in Europe, BPS is used as the broader term, with IC still considered a well-defined subgroup that usually involves ulceration.6 The future may find IC, BPS, and painful bladder syndrome (PBS) used as interchangeable terms—or as unique diagnoses. A better understanding of the pathophysiology of IC/BPS/PBS would contribute not only to resolving issues of nomenclature, but also to establishing an accurate diagnosis earlier in the disease process and providing more efficient, effective treatment.

THE PROBLEM OF EPIDEMIOLOGY

Inconsistencies in the terminology, definitions, and diagnostic criteria of IC/BPS have made epidemiology difficult to establish.1 It has been suggested that IC/BPS is underdiagnosed in the United States and that its prevalence is much greater than generally reported.8

According to one study of IC in a managed care population, its prevalence in 2005 was 197 per 100,000 women and 41 per 100,000 men, with the female-to-male ratio estimated at 5:1.9 In 2011, researchers for the RAND Corporation published what they called the first population-based “symptom prevalence estimate” among US women older than 18, based on more than 100,000 screening interviews conducted by phone. According to their findings, between 3.3 and 7.9 million US women meet the stated criteria for IC/BPS (ie, between 3,113 and 7,453 women per 100,000).10 These conflicting data exemplify the range of epidemiologic conclusions that exist regarding this condition.

On the next page: Proposed pathophysiology >>

THE PROPOSED PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

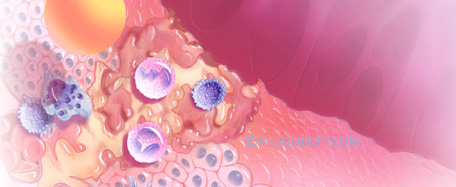

IC/BPS is thought to begin with an initial insult to the bladder that leads to dysfunction of the epithelial layer. This insult may be the result of a neurogenic inflammation, autoimmunity, subclinical or chronic infection, or bladder urothelial defects.1 Dysfunction in the epithelial layer includes altered bladder epithelial expression of human leukocyte antigen I and II; decreased expression of uroplakin (an antitoxic protein in the bladder), and a defective glycosaminoglycan mucus layer.4 This damage to the epithelial layer alters the permeability of the bladder, allowing potassium ions to enter the urothelium and depolarize motor and sensory nerves. This potassium leak then activates the mast cells, causing mastocytosis and the release of histamine.11 These processes disrupt the homeostasis of the urinary tract and allow the development of inflammation—a main cause of the pelvic pain associated with IC/BPS4,12,13 (see Figure 114).

Other factors that exacerbate the primary inflammation in the bladder are C-fibers and nerve growth factor (NGF). C-fibers are afferent fibers found in the peripheral nerves of the somatic sensory system that convey input signals from the periphery to the central nervous system.3 In patients with IC/BPS, initial inflammation activates C-fibers, which produce substance P, nociceptor, and other inflammatory mediators. These mediators exacerbate existing inflammation and further facilitate mast cell activation.3

NGF is a protein that is critical for the maintenance of sympathetic and sensory neurons; it is important not only in the urinary tract but in all organ systems. Increased levels of NGF, a prevalent finding in patients with IC/BPS, is an indicator of inflammation in the body. The precise mechanism that causes elevated NGF in patients with IC/BPS is not well understood, but its presence supports the theory that inflammation is a cause of pelvic pain in IC/BPS.12

The urinary urgency and frequency experienced by patients with IC/BPS is in part due to the role nitric oxide (NO) plays in bladder activity. Patients with IC have decreased levels of urinary NO (a reduction thought to be the result of a decrease in L-arginine) and urinary NO synthase.12,15,16 Ordinarily, NO synthase converts L-arginine to NO, which helps to control relaxation of the bladder smooth muscle, allowing more urine to be stored. In patients with IC/BPS, NO insufficiency leads to bladder overactivity.15

On the next page: Patient history and presentation >>

PATIENT HISTORY AND PRESENTATION

A detailed patient history is imperative in establishing the diagnosis of IC/BPS. Symptoms that should prompt the clinician to consider IC/BPS include:

• Pelvic or bladder pain relieved with voiding

• Dyspareunia

• Increased frequency of urination with no infection present

• Urinary urgency with pain, and

• Increased nocturia.17,18

Early IC presents variably, and pain, though a common symptom, is not always present.19 Chronic pain is defined by duration of at least six months, with the discomfort perceived as originating in the bladder.8 In addition to patients who experience pain, those who void several times during the night should also be considered for further evaluation.19

Many patients describe their symptoms in terms of flares and periods of remission. Some patients associate flares with stress, seasonal allergies, sexual activity, consumption of certain foods, and the premenstrual week.17,20 Patients with IC/BPS are commonly misdiagnosed with recurrent urinary tract infections; hence the need to standardize the criteria for diagnosis of IC/BPS.17

DIAGNOSIS

There are currently three available sets of diagnostic criteria for patients with IC/BPS. These are the National Institute for Diabetes and Diseases of the Kidney (NIDDK) definition (1990),21 the International Continence Society (ICS) definition of painful bladder disorders (2002),5 and the European Society for the Study of IC/BPS (ESSIC) definition (2008).6 In particular, the ESSIC criteria were formulated to help identify IC/BPS earlier in the disease course.

The 1990 NIDDK protocol, developed for research purposes,12 featured inclusion and exclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria included age younger than 18 years and presence of benign bladder tumors, radiation cystitis, tuberculosis cystitis, bacterial cystitis, vaginitis, symptomatic urethral diverticulum, uterine/cervical/vaginal cancers, and/or active herpes; urinary frequency of less than five episodes in 12 hours; and less than two episodes of nocturia per night.19

NIDDK inclusion criteria required two or more of the following: Hunner’s ulcer, pain on bladder filling, general pelvic pain, glomerulations on endoscopy, and decreased bladder compliance on cystometrogram.19

This protocol proved to be excessively restrictive for clinical use and was widely replaced by the ICS criteria in 2002. The ICS criteria5 allowed more varied patient presentations; the exclusions featured in the NIDDK guideline, it has been estimated, could have eliminated at least one-third of patients who would reasonably be considered to have IC/BPS.21

In contrast to the NIDDK criteria, the ICS criteria5 defined BPS as “the complaint of suprapubic pain related to bladder filling, accompanied by other symptoms such as increased daytime and nighttime urinary frequency in the absence of proven urinary tract infection or other obvious pathology.”5 Additionally, the ICS document restricts the diagnosis of IC to patients with painful bladder syndrome in addition to “typical cystoscopic and histologic features.”6

According to the ESSIC proposal on diagnostic criteria, classification, and nomenclature,6 diagnosing IC/BPS requires symptoms of chronic pain related to the urinary bladder accompanied by at least one other urinary symptom, such as daytime and nighttime frequency and exclusion of confusable diseases and cystoscopy with hydrodistention and biopsy, if indicated. The new statement does not include the required absence of UTI or other pathology identified in the previous (ICS) criteria; these, too, overlooked a portion of the population who would be considered to have IC/BPS. Therefore, the ESSIC classification provides the most comprehensive criteria for diagnosing IC/BPS and has been determined as best for diagnostic purposes in the early disease stages.12

On the next page: Applying the criteria and referral >>

Applying the Criteria

IC/BPS remains a diagnosis of exclusion.12 The most common disorders seen in the differential diagnosis for IC/BPS (ie, “confusable diseases”6) include bacterial cystitis, vaginitis, pelvic pain, vulvodynia, urinary tract infections, yeast infections, sexually transmitted infections, endometriosis, overactive bladder, and genitourinary malignancies.5,12

Biopsy or cystoscopy with short-duration, low-pressure hydrodistention can be performed on patients who present with persistent pelvic pain and urinary symptoms.2,12 Common cystoscopic findings in patients with IC/BPS include Hunner’s lesions, glomerulations, and inflammatory infiltrates on biopsy.12,21 Hunner’s lesions are described as “patches of red mucosa exhibiting small vessels radiating to a central pale scar.”21 These lesions may also be referred to as Hunner’s ulcers.12 Not always visible on cystoscopy, Hunner’s lesions may be seen only after hydrodistention of the bladder under anesthesia.

Cystoscopic findings can be misleading for providers, as not all stages of IC/BPS manifest in the same manner. No single laboratory finding will identify IC/BPS. The only way to diagnose this disease is to rule out all other diseases with similar presentations.18

When to Refer

Specific findings that may indicate the need for referral include severe pain, hematuria, chronic UTI, and pyuria. Generally, however, the decision to refer the patient with IC/BPS to a urologist or urogynecologist depends on the primary care provider’s comfort level. Some providers choose to refer as soon as identifying symptoms of IC/BPS have been confirmed, whereas others may wish to proceed with further evaluation and/or treatment before referring.2,22

Even if the provider decides to refer immediately after identifying symptoms, it is important to initiate some patient education: for example, explaining that the patient will likely require further tests, including cystoscopy and possibly urodynamic evaluation.2,23 Smokers and other patients at high risk for bladder cancer should be referred for cystoscopy.2

If the primary care provider chooses to proceed with evaluation and treatment before referring the patient, follow-up is typically recommended at one-month intervals for the first three months, then every three months thereafter.18 This allows the clinician to monitor a patient’s progress and address concerns that may develop. Symptoms may be slow to respond to treatment, so it is essential to encourage the patient to adhere to the prescribed regimen. If three to six months of first-line treatment yield no response, further consultation and evaluation are warranted. Overall, a multidisciplinary approach that includes the participation of a urologist, a gynecologist, or other appropriate specialist will help ensure optimal treatment and care.18

A good tool that is often used to gauge the patient’s progress is the O’Leary/Sant Voiding and Pain Indices23-25 (see Figure 224). Reviewing patient responses to this questionnaire, with its precise numerical system, at each follow-up appointment can be especially helpful.

On the next page: Treatment >>

TREATMENT

Management of IC/BPS can be challenging, because it is such a multifaceted disorder. Patient education beginning shortly after diagnosis is crucial, as treatment regimens may involve complex multimodal therapy over long periods of time, oftentimes with a very gradual response (see “For Your Patient”).

Lifestyle changes for patients with IC/BPS are considered an important component of treatment. Dietary changes—specifically, reducing intake of foods with high acidic content (citrus fruits, tomatoes), alcoholic beverages, spices, and potassium—have been found helpful.5 Reducing stress and anxiety, whenever possible, has also been noted to alleviate symptoms.24

Another nonpharmacologic option is physical therapy, including biofeedback and bladder retraining.12,13 Biofeedback is particularly useful in patients who experience pelvic pain attributed to spasms of the pelvic floor.12 Bladder retraining can be used to reduce urinary frequency through techniques that include scheduled voiding. Physical therapy strategies should be revisited regularly to maintain their therapeutic benefits.5,12

Oral Medications

The mainstay of pharmacologic treatment, and the one most thoroughly studied, is oral pentosan polysulfate (PPS), which belongs to the class of heparins or heparinoids.2,26 PPS is thought to attach to the mucosa of the bladder, reestablishing its glycosaminoglycan layer and restoring normal function of this permeable barrier.14 Overall, this drug is well tolerated and relieves the symptoms of pain, urgency, and frequency. Patients may start to experience improvement in symptoms after four weeks of treatment; however, it can take six months or longer to achieve the full benefit of this therapy.13,25

Other pharmacologic agents used in the treatment of IC/BPS include antihistamines, tricyclic antidepressants, and some antiepileptic medications. Some patients with IC/BPS experience symptoms attributable to bladder mastocytosis and mast cell activation, explaining the efficacy of antihistamines for these particular patients.27 Among the antihistamines, hydroxyzine, an H1-receptor antagonist, is a common pharmacologic option. Similarly, cetirizine can be used in patients for whom the sedating effects of hydroxyzine may prove hazardous.28

Antidepressants, especially tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs, eg, amitriptyline), can also provide some relief for patients, including alleviation of pain, possible antihistamine effects, and mild anticholinergic action, leading to decreased urinary urgency and frequency.2,26,29 Of note, the TCA imipramine should be avoided in patients with IC/BPS, as it has a sympathomimetic effect that can worsen symptoms of dysfunctional voiding in this patient population.14

Gabapentin, an antiepileptic, is used for improvement of severe, persistent pain. Alternatives to gabapentin include, but are not limited to, phenytoin, carbamazepine, and valproic acid.14 The effectiveness of these medications in the treatment of IC/BPS lend credence to the theory that, in addition to bladder mucosa dysfunction, symptoms are also mediated through an inflammatory neurogenic pathway.

Patients should be encouraged to continue use of PPS or other prescribed pharmacologic treatments even if there is no immediate relief of symptoms.25 According to a treatment algorithm from the American Urological Association,2 however, ineffective treatments should be stopped and diagnosis should be reconsidered if there is no improvement within a “clinically meaningful time frame.”

Additional Pharmacologic Options

Intravesical therapy is another mode of pharmacologic treatment.2,29 This treatment is usually reserved for IC/BPS flares and management of cases lacking the desired response to oral medications. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) is a commonly used intravesical agent. DMSO acts to provide pain relief and reduce inflammation, in addition to effecting histamine release from mast cells.27 Intravesical heparinoids essentially employ the same mechanism of action as oral PPS to maintain and enhance the bladder’s mucosal lining. This treatment is also commonly used in patients who need to discontinue use of oral PPS due to side effects.27,30

Treatment options for refractory IC/BPS include immunosuppression (and surgical therapy, below). Prednisone and cyclosporine have been shown to be effective immunosuppressive agents.23 Side effects make the use of these medications less desirable; also, symptoms have been shown to return in many patients after treatment is stopped.23

The FDA has recently approved the use of onabotulinum toxin A (Botox) injections into the bladder for treatment of urinary urgency and frequency that are not responsive to standard medical therapy. Since patients with IC often experience such symptoms with no relief from standard therapy, intratrigonal and periurethral injections of Botox are being administered for treatment of IC in some patients with moderate success.31-33 Although intradetrusor Botox use is recommended as a fifth-line treatment in the AUA guidelines,2 it is important to note that this agent is not FDA-approved specifically for IC, but rather for any refractory condition presenting with urinary frequency and urgency.

Surgical Therapy

Surgical intervention (a sixth-line treatment option, according to the AUA guidelines2) is rarely indicated except in cases of severe IC/BPS that have been refractory to all other treatment options and in which spontaneous remission of symptoms seems unlikely. Supravesical urinary diversion, usually through the creation of an ileal conduit, is the procedure of choice and is often performed in conjunction with a cystectomy. Unfortunately in some cases, pelvic pain has been noted to continue postcystectomy, a finding that also supports a neurogenic etiology for IC/BPS.14

On the Horizon

Although IC/PBS is difficult to treat, new data suggest that use of extended diagnostics, including molecular markers to detect the disease early and guide effective treatment, may greatly improve current therapeutic options.34

Prescribing selective anticholinergic and antihistamine pharmacotherapy based on the patient’s specific muscarinic and histamine receptor profile, respectively, may provide greater symptom relief.34 Maintaining the appropriate, individualized therapy could represent a significant advance in treatment for IC/BPS. However, further research on the topic is needed.

On the next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

IC/BPS is a complex multifactorial syndrome that may manifest with disabling pain. Further research on this disease is warranted to help facilitate an earlier, more consistent diagnosis and produce more effective treatment options. Early diagnosis of IC/BPS is essential for successful therapy. Once the diagnosis is made, a cautious regimen of different treatments, following the American Urological Association’s clinical practice guidelines for interstitial cystitis, should be implemented. Patients should also be encouraged to consider specific dietary changes and other lifestyle adjustments under a clinician’s supervision.

The authors wish to thank Carol Hildebrandt for her help in preparing this manuscript and Robert J. Evans, MD, Associate Professor of Urology, Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center, for his editorial expertise.

1. Dasgupta J, Tincello DG. Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: an update. Maturitas. 2009;64:212-217.

2. Hanno PM, Burks DA, Clemens JQ, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: American Urological Association (AUA) Guideline (2011). www.auanet.org/education/guidelines/ic-bladder-pain-syndrome.cfm. Accessed June 5, 2013.

3. Evans RJ; University of Tennessee Advanced Studies in Pharmacy. Pathophysiology and clinical presentation of interstitial cystitis (2005). www.utasip.com/files/articlefiles/pdf/XASIP_Issue_Mar_p8_14.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2013.

4. Sant GR. Etiology, pathogenesis, and diagnosis of interstitial cystitis. Rev Urol. 2002;(4 suppl 1):S9-S15.

5. Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:167-178.

6. van de Merwe JP, Nordling J, Bouchelouche P, et al. Diagnostic criteria, classification, and nomenclature for painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis: an ESSIC proposal. Eur Urol. 2008;53:60-67.

7. Bogart LM, Berry SH, Clemens JQ. Symptoms of interstitial cystitis, painful bladder syndrome and similar diseases in women: a systematic review. J Urol. 2007;177:450-456.

8. Kusek JW, Nyberg LM. The epidemiology of interstitial cystitis: is it time to expand our definition? Urology. 2001;57(6 suppl 1):95-99.

9. Clemens JQ, Meenan RT, Rosetti MC, et al. Prevalence and incidence of interstitial cystitis in a managed care population. J Urol. 2005;173:98-102.

10. Berry SH, Elliott MN, Suttorp M, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis among adult females in the United States. J Urol. 2011;186:540-544.

11. Rosamilia A, Dwyer PL. Pathophysiology of interstitial cystitis. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2000;12:405-410.

12. Grover S, Srivastava A, Lee R, et al. Role of inflammation in bladder function and interstitial cystitis. Ther Adv Urol. 2011;3:19-33.

13. Rosenberg MT, Page S, Hazzard MA. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis in a primary care setting. Urology. 2007;69(4 suppl):S48-S52.

14. Evans RJ. Treatment approaches for interstitial cystitis: multimodality therapy. Rev Urol. 2002;(4 suppl 1):S16-S20.

15. Wesselmann U. Interstitial cystitis: a chronic visceral pain syndrome. Urology. 2001;57(6 suppl 1):102.

16. Hosseini A, Ehrén I, Wiklund NP. Nitric oxide as an objective marker for evaluation of treatment response in patients with classic interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2004;172(6 pt 1):2261-2265.

17. Ho MH, Bhatia NN, Khorram O. Physiologic role of nitric oxide and nitric oxide synthase in female lower urinary tract. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2004;16:423-429.

18. Rosenberg MT, Newman DK, Page SA. Interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome: symptom recognition is key to early identification, treatment. Cleve Clin J Med. 2007;74:854-862.

19. Driscoll A, Teichman JM. How do patients with interstitial cystitis present? J Urol. 2001;166:2118-2120.

20. Parsons CL. Interstitial cystitis: epidemiology and clinical presentation. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45:242-249.

21. Hanno PM, Landis JR, Matthews-Cook Y, et al. The diagnosis of interstitial cystitis revisited: lessons learned from the National Institutes of Health Interstitial Cystitis Database study. J Urol. 1999;161:553-557.

22. Whitmore KE, Theoharides TC. When to suspect interstitial cystitis. J Fam Pract. 2011;60:340-348.

23. Butrick CW, Howard FM, Sand PK. Diagnosis and treatment of interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome: a review. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010;19:1185-1193.

24. O’Leary MP, Sant GR, Fowler FJ Jr, et al. The interstitial cystitis symptom index and problem index. Urology. 1997;49(5A suppl):58-63.

25. Nickel JC. Forensic dissection of a clinical trial: lessons learned in understanding and managing interstitial cystitis. Rev Urol. 2010;12:e78-e85.

26. Anger JT, Zabihi N, Clemens JQ, et al. Treatment choice, duration, and cost in patients with interstitial cystitis and painful bladder syndrome. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:395-400.

27. Nickel JC. Interstitial cystitis: characterization and management of an enigmatic urologic syndrome. Rev Urol. 2002;4:112-121.

28. Dell JR. Interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome: appropriate diagnosis and management. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2007;16:1181-1187.

29. National Kidney and Urologic Diseases Information Clearinghouse. Interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome (2011). NIH Publication No. 11–3220. http://kidney.niddk.nih.gov/kudiseases/pubs/interstitialcystitis/IC_PBS_T_508.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2013.

30. Davis EL, El Khoudary SR, Talbott EO, et al. Safety and efficacy of the use of intravesical and oral pentosan polysulfate sodium for interstitial cystitis: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. J Urol. 2008;179:177-185.

31. Pinto R, Lopes T, Silva J, et al. Persistent therapeutic effect of repeated injections of onabotulinum toxin a in refractory bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2013;189:548-553.

32. Pinto R, Lopoes T, Frias B, et al. Trigonal injection of botulinum toxin A in patients with refractory bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis. Eur Urol. 2010;58:360-365.

33. Gottsch HP, Miller JL, Yang CC, Berger RE. A pilot study of botulinum toxin for interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011; 30:93-96.

34. Neuhaus J, Schwalenberg T, Horn LC, et al. New aspects in the differential diagnosis and therapy of bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis. Adv Urol. 2011;2011:639479.

CE/CME No: CR-1307

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

•

Describe the pathophysiology

of interstitial cystitis/bladder

pain syndrome (IC/BPS), as

it is currently understood.

•

Discuss urogenital signs and

symptoms that should prompt suspicion for IC/BPS in a primary care patient.

•

Explain the clinical diagnosis of

IC/BPS and key considerations for referral.

•

Review medical management, nonoperative therapy, and surgical treatment of IC/BPS.

FACULTY

LaToya M. Haynes practices at the Carolinas Pain Institute and the Center for Clinical Research in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and is a preceptor for PA students. Kelly Bilello is a PA at Genitourinary Surgical Consultants in Denver. Jade Breeback practices at Cone Health Primary Care in Kernersville, North Carolina. Jessica Cain is a PA in emergency medicine at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center. Jennifer Wenninger is a cardiothoracic and vascular surgery PA at Bellin Health Care Systems in Green Bay, Wisconsin. M. Jane McDaniel is an Instructor in the Department of Physician Assistant Studies at Wake Forest School of Medicine in Winston-Salem.

The authors have no significant financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Article begins on next page >>

Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) is a common, painful disease of the urinary bladder. Difficult to diagnose and frequently misdiagnosed as another common urologic disorder, IC/BPS challenges health care providers to identify it early and implement current treatment algorithms that may simplify management and improve quality of life for affected patients.

Interstitial cystitis (IC), or bladder pain syndrome (BPS), is a clinical condition characterized by bladder pain, urinary frequency and urgency, and increased nighttime urination (nocturia).1 More specifically, IC/BPS is defined as an unpleasant sensation in the bladder, abdomen, or pelvis (ie, pain, pressure, burning, and/or other discomfort) perceived to be originating in the urinary bladder. The condition is associated with lower urinary tract symptoms of more than six weeks’ duration, with no infection or other identifiable cause present.2

IC/BPS lacks a single known etiology; rather, it most likely results from multiple contributing factors that cascade into a painful and potentially debilitating syndrome. The condition was first described more than a century ago,3,4 but its complex nature and conflicting theories about its pathogenesis present both diagnostic and therapeutic challenges for health care professionals. Frequent misdiagnosis of IC/BPS as another common urologic disorder can make timely, appropriate treatment elusive.

Without a clearly described pathophysiology, IC/BPS has always been difficult to define using standardized diagnostic criteria and precise terminology. The definition of the condition was revised in 2002 and again in 2008, when the nomenclature bladder pain syndrome was introduced.1,5,6

Less than 10 years ago, US researchers described IC as a subgroup of BPS,7 while in Europe, BPS is used as the broader term, with IC still considered a well-defined subgroup that usually involves ulceration.6 The future may find IC, BPS, and painful bladder syndrome (PBS) used as interchangeable terms—or as unique diagnoses. A better understanding of the pathophysiology of IC/BPS/PBS would contribute not only to resolving issues of nomenclature, but also to establishing an accurate diagnosis earlier in the disease process and providing more efficient, effective treatment.

THE PROBLEM OF EPIDEMIOLOGY

Inconsistencies in the terminology, definitions, and diagnostic criteria of IC/BPS have made epidemiology difficult to establish.1 It has been suggested that IC/BPS is underdiagnosed in the United States and that its prevalence is much greater than generally reported.8

According to one study of IC in a managed care population, its prevalence in 2005 was 197 per 100,000 women and 41 per 100,000 men, with the female-to-male ratio estimated at 5:1.9 In 2011, researchers for the RAND Corporation published what they called the first population-based “symptom prevalence estimate” among US women older than 18, based on more than 100,000 screening interviews conducted by phone. According to their findings, between 3.3 and 7.9 million US women meet the stated criteria for IC/BPS (ie, between 3,113 and 7,453 women per 100,000).10 These conflicting data exemplify the range of epidemiologic conclusions that exist regarding this condition.

On the next page: Proposed pathophysiology >>

THE PROPOSED PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

IC/BPS is thought to begin with an initial insult to the bladder that leads to dysfunction of the epithelial layer. This insult may be the result of a neurogenic inflammation, autoimmunity, subclinical or chronic infection, or bladder urothelial defects.1 Dysfunction in the epithelial layer includes altered bladder epithelial expression of human leukocyte antigen I and II; decreased expression of uroplakin (an antitoxic protein in the bladder), and a defective glycosaminoglycan mucus layer.4 This damage to the epithelial layer alters the permeability of the bladder, allowing potassium ions to enter the urothelium and depolarize motor and sensory nerves. This potassium leak then activates the mast cells, causing mastocytosis and the release of histamine.11 These processes disrupt the homeostasis of the urinary tract and allow the development of inflammation—a main cause of the pelvic pain associated with IC/BPS4,12,13 (see Figure 114).

Other factors that exacerbate the primary inflammation in the bladder are C-fibers and nerve growth factor (NGF). C-fibers are afferent fibers found in the peripheral nerves of the somatic sensory system that convey input signals from the periphery to the central nervous system.3 In patients with IC/BPS, initial inflammation activates C-fibers, which produce substance P, nociceptor, and other inflammatory mediators. These mediators exacerbate existing inflammation and further facilitate mast cell activation.3

NGF is a protein that is critical for the maintenance of sympathetic and sensory neurons; it is important not only in the urinary tract but in all organ systems. Increased levels of NGF, a prevalent finding in patients with IC/BPS, is an indicator of inflammation in the body. The precise mechanism that causes elevated NGF in patients with IC/BPS is not well understood, but its presence supports the theory that inflammation is a cause of pelvic pain in IC/BPS.12

The urinary urgency and frequency experienced by patients with IC/BPS is in part due to the role nitric oxide (NO) plays in bladder activity. Patients with IC have decreased levels of urinary NO (a reduction thought to be the result of a decrease in L-arginine) and urinary NO synthase.12,15,16 Ordinarily, NO synthase converts L-arginine to NO, which helps to control relaxation of the bladder smooth muscle, allowing more urine to be stored. In patients with IC/BPS, NO insufficiency leads to bladder overactivity.15

On the next page: Patient history and presentation >>

PATIENT HISTORY AND PRESENTATION

A detailed patient history is imperative in establishing the diagnosis of IC/BPS. Symptoms that should prompt the clinician to consider IC/BPS include:

• Pelvic or bladder pain relieved with voiding

• Dyspareunia

• Increased frequency of urination with no infection present

• Urinary urgency with pain, and

• Increased nocturia.17,18

Early IC presents variably, and pain, though a common symptom, is not always present.19 Chronic pain is defined by duration of at least six months, with the discomfort perceived as originating in the bladder.8 In addition to patients who experience pain, those who void several times during the night should also be considered for further evaluation.19

Many patients describe their symptoms in terms of flares and periods of remission. Some patients associate flares with stress, seasonal allergies, sexual activity, consumption of certain foods, and the premenstrual week.17,20 Patients with IC/BPS are commonly misdiagnosed with recurrent urinary tract infections; hence the need to standardize the criteria for diagnosis of IC/BPS.17

DIAGNOSIS

There are currently three available sets of diagnostic criteria for patients with IC/BPS. These are the National Institute for Diabetes and Diseases of the Kidney (NIDDK) definition (1990),21 the International Continence Society (ICS) definition of painful bladder disorders (2002),5 and the European Society for the Study of IC/BPS (ESSIC) definition (2008).6 In particular, the ESSIC criteria were formulated to help identify IC/BPS earlier in the disease course.

The 1990 NIDDK protocol, developed for research purposes,12 featured inclusion and exclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria included age younger than 18 years and presence of benign bladder tumors, radiation cystitis, tuberculosis cystitis, bacterial cystitis, vaginitis, symptomatic urethral diverticulum, uterine/cervical/vaginal cancers, and/or active herpes; urinary frequency of less than five episodes in 12 hours; and less than two episodes of nocturia per night.19

NIDDK inclusion criteria required two or more of the following: Hunner’s ulcer, pain on bladder filling, general pelvic pain, glomerulations on endoscopy, and decreased bladder compliance on cystometrogram.19

This protocol proved to be excessively restrictive for clinical use and was widely replaced by the ICS criteria in 2002. The ICS criteria5 allowed more varied patient presentations; the exclusions featured in the NIDDK guideline, it has been estimated, could have eliminated at least one-third of patients who would reasonably be considered to have IC/BPS.21

In contrast to the NIDDK criteria, the ICS criteria5 defined BPS as “the complaint of suprapubic pain related to bladder filling, accompanied by other symptoms such as increased daytime and nighttime urinary frequency in the absence of proven urinary tract infection or other obvious pathology.”5 Additionally, the ICS document restricts the diagnosis of IC to patients with painful bladder syndrome in addition to “typical cystoscopic and histologic features.”6

According to the ESSIC proposal on diagnostic criteria, classification, and nomenclature,6 diagnosing IC/BPS requires symptoms of chronic pain related to the urinary bladder accompanied by at least one other urinary symptom, such as daytime and nighttime frequency and exclusion of confusable diseases and cystoscopy with hydrodistention and biopsy, if indicated. The new statement does not include the required absence of UTI or other pathology identified in the previous (ICS) criteria; these, too, overlooked a portion of the population who would be considered to have IC/BPS. Therefore, the ESSIC classification provides the most comprehensive criteria for diagnosing IC/BPS and has been determined as best for diagnostic purposes in the early disease stages.12

On the next page: Applying the criteria and referral >>

Applying the Criteria

IC/BPS remains a diagnosis of exclusion.12 The most common disorders seen in the differential diagnosis for IC/BPS (ie, “confusable diseases”6) include bacterial cystitis, vaginitis, pelvic pain, vulvodynia, urinary tract infections, yeast infections, sexually transmitted infections, endometriosis, overactive bladder, and genitourinary malignancies.5,12

Biopsy or cystoscopy with short-duration, low-pressure hydrodistention can be performed on patients who present with persistent pelvic pain and urinary symptoms.2,12 Common cystoscopic findings in patients with IC/BPS include Hunner’s lesions, glomerulations, and inflammatory infiltrates on biopsy.12,21 Hunner’s lesions are described as “patches of red mucosa exhibiting small vessels radiating to a central pale scar.”21 These lesions may also be referred to as Hunner’s ulcers.12 Not always visible on cystoscopy, Hunner’s lesions may be seen only after hydrodistention of the bladder under anesthesia.

Cystoscopic findings can be misleading for providers, as not all stages of IC/BPS manifest in the same manner. No single laboratory finding will identify IC/BPS. The only way to diagnose this disease is to rule out all other diseases with similar presentations.18

When to Refer

Specific findings that may indicate the need for referral include severe pain, hematuria, chronic UTI, and pyuria. Generally, however, the decision to refer the patient with IC/BPS to a urologist or urogynecologist depends on the primary care provider’s comfort level. Some providers choose to refer as soon as identifying symptoms of IC/BPS have been confirmed, whereas others may wish to proceed with further evaluation and/or treatment before referring.2,22

Even if the provider decides to refer immediately after identifying symptoms, it is important to initiate some patient education: for example, explaining that the patient will likely require further tests, including cystoscopy and possibly urodynamic evaluation.2,23 Smokers and other patients at high risk for bladder cancer should be referred for cystoscopy.2

If the primary care provider chooses to proceed with evaluation and treatment before referring the patient, follow-up is typically recommended at one-month intervals for the first three months, then every three months thereafter.18 This allows the clinician to monitor a patient’s progress and address concerns that may develop. Symptoms may be slow to respond to treatment, so it is essential to encourage the patient to adhere to the prescribed regimen. If three to six months of first-line treatment yield no response, further consultation and evaluation are warranted. Overall, a multidisciplinary approach that includes the participation of a urologist, a gynecologist, or other appropriate specialist will help ensure optimal treatment and care.18

A good tool that is often used to gauge the patient’s progress is the O’Leary/Sant Voiding and Pain Indices23-25 (see Figure 224). Reviewing patient responses to this questionnaire, with its precise numerical system, at each follow-up appointment can be especially helpful.

On the next page: Treatment >>

TREATMENT

Management of IC/BPS can be challenging, because it is such a multifaceted disorder. Patient education beginning shortly after diagnosis is crucial, as treatment regimens may involve complex multimodal therapy over long periods of time, oftentimes with a very gradual response (see “For Your Patient”).

Lifestyle changes for patients with IC/BPS are considered an important component of treatment. Dietary changes—specifically, reducing intake of foods with high acidic content (citrus fruits, tomatoes), alcoholic beverages, spices, and potassium—have been found helpful.5 Reducing stress and anxiety, whenever possible, has also been noted to alleviate symptoms.24

Another nonpharmacologic option is physical therapy, including biofeedback and bladder retraining.12,13 Biofeedback is particularly useful in patients who experience pelvic pain attributed to spasms of the pelvic floor.12 Bladder retraining can be used to reduce urinary frequency through techniques that include scheduled voiding. Physical therapy strategies should be revisited regularly to maintain their therapeutic benefits.5,12

Oral Medications

The mainstay of pharmacologic treatment, and the one most thoroughly studied, is oral pentosan polysulfate (PPS), which belongs to the class of heparins or heparinoids.2,26 PPS is thought to attach to the mucosa of the bladder, reestablishing its glycosaminoglycan layer and restoring normal function of this permeable barrier.14 Overall, this drug is well tolerated and relieves the symptoms of pain, urgency, and frequency. Patients may start to experience improvement in symptoms after four weeks of treatment; however, it can take six months or longer to achieve the full benefit of this therapy.13,25

Other pharmacologic agents used in the treatment of IC/BPS include antihistamines, tricyclic antidepressants, and some antiepileptic medications. Some patients with IC/BPS experience symptoms attributable to bladder mastocytosis and mast cell activation, explaining the efficacy of antihistamines for these particular patients.27 Among the antihistamines, hydroxyzine, an H1-receptor antagonist, is a common pharmacologic option. Similarly, cetirizine can be used in patients for whom the sedating effects of hydroxyzine may prove hazardous.28

Antidepressants, especially tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs, eg, amitriptyline), can also provide some relief for patients, including alleviation of pain, possible antihistamine effects, and mild anticholinergic action, leading to decreased urinary urgency and frequency.2,26,29 Of note, the TCA imipramine should be avoided in patients with IC/BPS, as it has a sympathomimetic effect that can worsen symptoms of dysfunctional voiding in this patient population.14

Gabapentin, an antiepileptic, is used for improvement of severe, persistent pain. Alternatives to gabapentin include, but are not limited to, phenytoin, carbamazepine, and valproic acid.14 The effectiveness of these medications in the treatment of IC/BPS lend credence to the theory that, in addition to bladder mucosa dysfunction, symptoms are also mediated through an inflammatory neurogenic pathway.

Patients should be encouraged to continue use of PPS or other prescribed pharmacologic treatments even if there is no immediate relief of symptoms.25 According to a treatment algorithm from the American Urological Association,2 however, ineffective treatments should be stopped and diagnosis should be reconsidered if there is no improvement within a “clinically meaningful time frame.”

Additional Pharmacologic Options

Intravesical therapy is another mode of pharmacologic treatment.2,29 This treatment is usually reserved for IC/BPS flares and management of cases lacking the desired response to oral medications. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) is a commonly used intravesical agent. DMSO acts to provide pain relief and reduce inflammation, in addition to effecting histamine release from mast cells.27 Intravesical heparinoids essentially employ the same mechanism of action as oral PPS to maintain and enhance the bladder’s mucosal lining. This treatment is also commonly used in patients who need to discontinue use of oral PPS due to side effects.27,30

Treatment options for refractory IC/BPS include immunosuppression (and surgical therapy, below). Prednisone and cyclosporine have been shown to be effective immunosuppressive agents.23 Side effects make the use of these medications less desirable; also, symptoms have been shown to return in many patients after treatment is stopped.23

The FDA has recently approved the use of onabotulinum toxin A (Botox) injections into the bladder for treatment of urinary urgency and frequency that are not responsive to standard medical therapy. Since patients with IC often experience such symptoms with no relief from standard therapy, intratrigonal and periurethral injections of Botox are being administered for treatment of IC in some patients with moderate success.31-33 Although intradetrusor Botox use is recommended as a fifth-line treatment in the AUA guidelines,2 it is important to note that this agent is not FDA-approved specifically for IC, but rather for any refractory condition presenting with urinary frequency and urgency.

Surgical Therapy

Surgical intervention (a sixth-line treatment option, according to the AUA guidelines2) is rarely indicated except in cases of severe IC/BPS that have been refractory to all other treatment options and in which spontaneous remission of symptoms seems unlikely. Supravesical urinary diversion, usually through the creation of an ileal conduit, is the procedure of choice and is often performed in conjunction with a cystectomy. Unfortunately in some cases, pelvic pain has been noted to continue postcystectomy, a finding that also supports a neurogenic etiology for IC/BPS.14

On the Horizon

Although IC/PBS is difficult to treat, new data suggest that use of extended diagnostics, including molecular markers to detect the disease early and guide effective treatment, may greatly improve current therapeutic options.34

Prescribing selective anticholinergic and antihistamine pharmacotherapy based on the patient’s specific muscarinic and histamine receptor profile, respectively, may provide greater symptom relief.34 Maintaining the appropriate, individualized therapy could represent a significant advance in treatment for IC/BPS. However, further research on the topic is needed.

On the next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

IC/BPS is a complex multifactorial syndrome that may manifest with disabling pain. Further research on this disease is warranted to help facilitate an earlier, more consistent diagnosis and produce more effective treatment options. Early diagnosis of IC/BPS is essential for successful therapy. Once the diagnosis is made, a cautious regimen of different treatments, following the American Urological Association’s clinical practice guidelines for interstitial cystitis, should be implemented. Patients should also be encouraged to consider specific dietary changes and other lifestyle adjustments under a clinician’s supervision.

The authors wish to thank Carol Hildebrandt for her help in preparing this manuscript and Robert J. Evans, MD, Associate Professor of Urology, Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center, for his editorial expertise.

CE/CME No: CR-1307

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

•

Describe the pathophysiology

of interstitial cystitis/bladder

pain syndrome (IC/BPS), as

it is currently understood.

•

Discuss urogenital signs and

symptoms that should prompt suspicion for IC/BPS in a primary care patient.

•

Explain the clinical diagnosis of

IC/BPS and key considerations for referral.

•

Review medical management, nonoperative therapy, and surgical treatment of IC/BPS.

FACULTY

LaToya M. Haynes practices at the Carolinas Pain Institute and the Center for Clinical Research in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and is a preceptor for PA students. Kelly Bilello is a PA at Genitourinary Surgical Consultants in Denver. Jade Breeback practices at Cone Health Primary Care in Kernersville, North Carolina. Jessica Cain is a PA in emergency medicine at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center. Jennifer Wenninger is a cardiothoracic and vascular surgery PA at Bellin Health Care Systems in Green Bay, Wisconsin. M. Jane McDaniel is an Instructor in the Department of Physician Assistant Studies at Wake Forest School of Medicine in Winston-Salem.

The authors have no significant financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Article begins on next page >>

Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) is a common, painful disease of the urinary bladder. Difficult to diagnose and frequently misdiagnosed as another common urologic disorder, IC/BPS challenges health care providers to identify it early and implement current treatment algorithms that may simplify management and improve quality of life for affected patients.

Interstitial cystitis (IC), or bladder pain syndrome (BPS), is a clinical condition characterized by bladder pain, urinary frequency and urgency, and increased nighttime urination (nocturia).1 More specifically, IC/BPS is defined as an unpleasant sensation in the bladder, abdomen, or pelvis (ie, pain, pressure, burning, and/or other discomfort) perceived to be originating in the urinary bladder. The condition is associated with lower urinary tract symptoms of more than six weeks’ duration, with no infection or other identifiable cause present.2

IC/BPS lacks a single known etiology; rather, it most likely results from multiple contributing factors that cascade into a painful and potentially debilitating syndrome. The condition was first described more than a century ago,3,4 but its complex nature and conflicting theories about its pathogenesis present both diagnostic and therapeutic challenges for health care professionals. Frequent misdiagnosis of IC/BPS as another common urologic disorder can make timely, appropriate treatment elusive.

Without a clearly described pathophysiology, IC/BPS has always been difficult to define using standardized diagnostic criteria and precise terminology. The definition of the condition was revised in 2002 and again in 2008, when the nomenclature bladder pain syndrome was introduced.1,5,6

Less than 10 years ago, US researchers described IC as a subgroup of BPS,7 while in Europe, BPS is used as the broader term, with IC still considered a well-defined subgroup that usually involves ulceration.6 The future may find IC, BPS, and painful bladder syndrome (PBS) used as interchangeable terms—or as unique diagnoses. A better understanding of the pathophysiology of IC/BPS/PBS would contribute not only to resolving issues of nomenclature, but also to establishing an accurate diagnosis earlier in the disease process and providing more efficient, effective treatment.

THE PROBLEM OF EPIDEMIOLOGY

Inconsistencies in the terminology, definitions, and diagnostic criteria of IC/BPS have made epidemiology difficult to establish.1 It has been suggested that IC/BPS is underdiagnosed in the United States and that its prevalence is much greater than generally reported.8

According to one study of IC in a managed care population, its prevalence in 2005 was 197 per 100,000 women and 41 per 100,000 men, with the female-to-male ratio estimated at 5:1.9 In 2011, researchers for the RAND Corporation published what they called the first population-based “symptom prevalence estimate” among US women older than 18, based on more than 100,000 screening interviews conducted by phone. According to their findings, between 3.3 and 7.9 million US women meet the stated criteria for IC/BPS (ie, between 3,113 and 7,453 women per 100,000).10 These conflicting data exemplify the range of epidemiologic conclusions that exist regarding this condition.

On the next page: Proposed pathophysiology >>

THE PROPOSED PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

IC/BPS is thought to begin with an initial insult to the bladder that leads to dysfunction of the epithelial layer. This insult may be the result of a neurogenic inflammation, autoimmunity, subclinical or chronic infection, or bladder urothelial defects.1 Dysfunction in the epithelial layer includes altered bladder epithelial expression of human leukocyte antigen I and II; decreased expression of uroplakin (an antitoxic protein in the bladder), and a defective glycosaminoglycan mucus layer.4 This damage to the epithelial layer alters the permeability of the bladder, allowing potassium ions to enter the urothelium and depolarize motor and sensory nerves. This potassium leak then activates the mast cells, causing mastocytosis and the release of histamine.11 These processes disrupt the homeostasis of the urinary tract and allow the development of inflammation—a main cause of the pelvic pain associated with IC/BPS4,12,13 (see Figure 114).

Other factors that exacerbate the primary inflammation in the bladder are C-fibers and nerve growth factor (NGF). C-fibers are afferent fibers found in the peripheral nerves of the somatic sensory system that convey input signals from the periphery to the central nervous system.3 In patients with IC/BPS, initial inflammation activates C-fibers, which produce substance P, nociceptor, and other inflammatory mediators. These mediators exacerbate existing inflammation and further facilitate mast cell activation.3

NGF is a protein that is critical for the maintenance of sympathetic and sensory neurons; it is important not only in the urinary tract but in all organ systems. Increased levels of NGF, a prevalent finding in patients with IC/BPS, is an indicator of inflammation in the body. The precise mechanism that causes elevated NGF in patients with IC/BPS is not well understood, but its presence supports the theory that inflammation is a cause of pelvic pain in IC/BPS.12

The urinary urgency and frequency experienced by patients with IC/BPS is in part due to the role nitric oxide (NO) plays in bladder activity. Patients with IC have decreased levels of urinary NO (a reduction thought to be the result of a decrease in L-arginine) and urinary NO synthase.12,15,16 Ordinarily, NO synthase converts L-arginine to NO, which helps to control relaxation of the bladder smooth muscle, allowing more urine to be stored. In patients with IC/BPS, NO insufficiency leads to bladder overactivity.15

On the next page: Patient history and presentation >>

PATIENT HISTORY AND PRESENTATION

A detailed patient history is imperative in establishing the diagnosis of IC/BPS. Symptoms that should prompt the clinician to consider IC/BPS include:

• Pelvic or bladder pain relieved with voiding

• Dyspareunia

• Increased frequency of urination with no infection present

• Urinary urgency with pain, and

• Increased nocturia.17,18

Early IC presents variably, and pain, though a common symptom, is not always present.19 Chronic pain is defined by duration of at least six months, with the discomfort perceived as originating in the bladder.8 In addition to patients who experience pain, those who void several times during the night should also be considered for further evaluation.19

Many patients describe their symptoms in terms of flares and periods of remission. Some patients associate flares with stress, seasonal allergies, sexual activity, consumption of certain foods, and the premenstrual week.17,20 Patients with IC/BPS are commonly misdiagnosed with recurrent urinary tract infections; hence the need to standardize the criteria for diagnosis of IC/BPS.17

DIAGNOSIS

There are currently three available sets of diagnostic criteria for patients with IC/BPS. These are the National Institute for Diabetes and Diseases of the Kidney (NIDDK) definition (1990),21 the International Continence Society (ICS) definition of painful bladder disorders (2002),5 and the European Society for the Study of IC/BPS (ESSIC) definition (2008).6 In particular, the ESSIC criteria were formulated to help identify IC/BPS earlier in the disease course.

The 1990 NIDDK protocol, developed for research purposes,12 featured inclusion and exclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria included age younger than 18 years and presence of benign bladder tumors, radiation cystitis, tuberculosis cystitis, bacterial cystitis, vaginitis, symptomatic urethral diverticulum, uterine/cervical/vaginal cancers, and/or active herpes; urinary frequency of less than five episodes in 12 hours; and less than two episodes of nocturia per night.19

NIDDK inclusion criteria required two or more of the following: Hunner’s ulcer, pain on bladder filling, general pelvic pain, glomerulations on endoscopy, and decreased bladder compliance on cystometrogram.19

This protocol proved to be excessively restrictive for clinical use and was widely replaced by the ICS criteria in 2002. The ICS criteria5 allowed more varied patient presentations; the exclusions featured in the NIDDK guideline, it has been estimated, could have eliminated at least one-third of patients who would reasonably be considered to have IC/BPS.21

In contrast to the NIDDK criteria, the ICS criteria5 defined BPS as “the complaint of suprapubic pain related to bladder filling, accompanied by other symptoms such as increased daytime and nighttime urinary frequency in the absence of proven urinary tract infection or other obvious pathology.”5 Additionally, the ICS document restricts the diagnosis of IC to patients with painful bladder syndrome in addition to “typical cystoscopic and histologic features.”6

According to the ESSIC proposal on diagnostic criteria, classification, and nomenclature,6 diagnosing IC/BPS requires symptoms of chronic pain related to the urinary bladder accompanied by at least one other urinary symptom, such as daytime and nighttime frequency and exclusion of confusable diseases and cystoscopy with hydrodistention and biopsy, if indicated. The new statement does not include the required absence of UTI or other pathology identified in the previous (ICS) criteria; these, too, overlooked a portion of the population who would be considered to have IC/BPS. Therefore, the ESSIC classification provides the most comprehensive criteria for diagnosing IC/BPS and has been determined as best for diagnostic purposes in the early disease stages.12

On the next page: Applying the criteria and referral >>

Applying the Criteria

IC/BPS remains a diagnosis of exclusion.12 The most common disorders seen in the differential diagnosis for IC/BPS (ie, “confusable diseases”6) include bacterial cystitis, vaginitis, pelvic pain, vulvodynia, urinary tract infections, yeast infections, sexually transmitted infections, endometriosis, overactive bladder, and genitourinary malignancies.5,12

Biopsy or cystoscopy with short-duration, low-pressure hydrodistention can be performed on patients who present with persistent pelvic pain and urinary symptoms.2,12 Common cystoscopic findings in patients with IC/BPS include Hunner’s lesions, glomerulations, and inflammatory infiltrates on biopsy.12,21 Hunner’s lesions are described as “patches of red mucosa exhibiting small vessels radiating to a central pale scar.”21 These lesions may also be referred to as Hunner’s ulcers.12 Not always visible on cystoscopy, Hunner’s lesions may be seen only after hydrodistention of the bladder under anesthesia.

Cystoscopic findings can be misleading for providers, as not all stages of IC/BPS manifest in the same manner. No single laboratory finding will identify IC/BPS. The only way to diagnose this disease is to rule out all other diseases with similar presentations.18

When to Refer

Specific findings that may indicate the need for referral include severe pain, hematuria, chronic UTI, and pyuria. Generally, however, the decision to refer the patient with IC/BPS to a urologist or urogynecologist depends on the primary care provider’s comfort level. Some providers choose to refer as soon as identifying symptoms of IC/BPS have been confirmed, whereas others may wish to proceed with further evaluation and/or treatment before referring.2,22

Even if the provider decides to refer immediately after identifying symptoms, it is important to initiate some patient education: for example, explaining that the patient will likely require further tests, including cystoscopy and possibly urodynamic evaluation.2,23 Smokers and other patients at high risk for bladder cancer should be referred for cystoscopy.2

If the primary care provider chooses to proceed with evaluation and treatment before referring the patient, follow-up is typically recommended at one-month intervals for the first three months, then every three months thereafter.18 This allows the clinician to monitor a patient’s progress and address concerns that may develop. Symptoms may be slow to respond to treatment, so it is essential to encourage the patient to adhere to the prescribed regimen. If three to six months of first-line treatment yield no response, further consultation and evaluation are warranted. Overall, a multidisciplinary approach that includes the participation of a urologist, a gynecologist, or other appropriate specialist will help ensure optimal treatment and care.18

A good tool that is often used to gauge the patient’s progress is the O’Leary/Sant Voiding and Pain Indices23-25 (see Figure 224). Reviewing patient responses to this questionnaire, with its precise numerical system, at each follow-up appointment can be especially helpful.

On the next page: Treatment >>

TREATMENT

Management of IC/BPS can be challenging, because it is such a multifaceted disorder. Patient education beginning shortly after diagnosis is crucial, as treatment regimens may involve complex multimodal therapy over long periods of time, oftentimes with a very gradual response (see “For Your Patient”).

Lifestyle changes for patients with IC/BPS are considered an important component of treatment. Dietary changes—specifically, reducing intake of foods with high acidic content (citrus fruits, tomatoes), alcoholic beverages, spices, and potassium—have been found helpful.5 Reducing stress and anxiety, whenever possible, has also been noted to alleviate symptoms.24

Another nonpharmacologic option is physical therapy, including biofeedback and bladder retraining.12,13 Biofeedback is particularly useful in patients who experience pelvic pain attributed to spasms of the pelvic floor.12 Bladder retraining can be used to reduce urinary frequency through techniques that include scheduled voiding. Physical therapy strategies should be revisited regularly to maintain their therapeutic benefits.5,12

Oral Medications

The mainstay of pharmacologic treatment, and the one most thoroughly studied, is oral pentosan polysulfate (PPS), which belongs to the class of heparins or heparinoids.2,26 PPS is thought to attach to the mucosa of the bladder, reestablishing its glycosaminoglycan layer and restoring normal function of this permeable barrier.14 Overall, this drug is well tolerated and relieves the symptoms of pain, urgency, and frequency. Patients may start to experience improvement in symptoms after four weeks of treatment; however, it can take six months or longer to achieve the full benefit of this therapy.13,25

Other pharmacologic agents used in the treatment of IC/BPS include antihistamines, tricyclic antidepressants, and some antiepileptic medications. Some patients with IC/BPS experience symptoms attributable to bladder mastocytosis and mast cell activation, explaining the efficacy of antihistamines for these particular patients.27 Among the antihistamines, hydroxyzine, an H1-receptor antagonist, is a common pharmacologic option. Similarly, cetirizine can be used in patients for whom the sedating effects of hydroxyzine may prove hazardous.28

Antidepressants, especially tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs, eg, amitriptyline), can also provide some relief for patients, including alleviation of pain, possible antihistamine effects, and mild anticholinergic action, leading to decreased urinary urgency and frequency.2,26,29 Of note, the TCA imipramine should be avoided in patients with IC/BPS, as it has a sympathomimetic effect that can worsen symptoms of dysfunctional voiding in this patient population.14

Gabapentin, an antiepileptic, is used for improvement of severe, persistent pain. Alternatives to gabapentin include, but are not limited to, phenytoin, carbamazepine, and valproic acid.14 The effectiveness of these medications in the treatment of IC/BPS lend credence to the theory that, in addition to bladder mucosa dysfunction, symptoms are also mediated through an inflammatory neurogenic pathway.

Patients should be encouraged to continue use of PPS or other prescribed pharmacologic treatments even if there is no immediate relief of symptoms.25 According to a treatment algorithm from the American Urological Association,2 however, ineffective treatments should be stopped and diagnosis should be reconsidered if there is no improvement within a “clinically meaningful time frame.”

Additional Pharmacologic Options

Intravesical therapy is another mode of pharmacologic treatment.2,29 This treatment is usually reserved for IC/BPS flares and management of cases lacking the desired response to oral medications. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) is a commonly used intravesical agent. DMSO acts to provide pain relief and reduce inflammation, in addition to effecting histamine release from mast cells.27 Intravesical heparinoids essentially employ the same mechanism of action as oral PPS to maintain and enhance the bladder’s mucosal lining. This treatment is also commonly used in patients who need to discontinue use of oral PPS due to side effects.27,30

Treatment options for refractory IC/BPS include immunosuppression (and surgical therapy, below). Prednisone and cyclosporine have been shown to be effective immunosuppressive agents.23 Side effects make the use of these medications less desirable; also, symptoms have been shown to return in many patients after treatment is stopped.23

The FDA has recently approved the use of onabotulinum toxin A (Botox) injections into the bladder for treatment of urinary urgency and frequency that are not responsive to standard medical therapy. Since patients with IC often experience such symptoms with no relief from standard therapy, intratrigonal and periurethral injections of Botox are being administered for treatment of IC in some patients with moderate success.31-33 Although intradetrusor Botox use is recommended as a fifth-line treatment in the AUA guidelines,2 it is important to note that this agent is not FDA-approved specifically for IC, but rather for any refractory condition presenting with urinary frequency and urgency.

Surgical Therapy

Surgical intervention (a sixth-line treatment option, according to the AUA guidelines2) is rarely indicated except in cases of severe IC/BPS that have been refractory to all other treatment options and in which spontaneous remission of symptoms seems unlikely. Supravesical urinary diversion, usually through the creation of an ileal conduit, is the procedure of choice and is often performed in conjunction with a cystectomy. Unfortunately in some cases, pelvic pain has been noted to continue postcystectomy, a finding that also supports a neurogenic etiology for IC/BPS.14

On the Horizon

Although IC/PBS is difficult to treat, new data suggest that use of extended diagnostics, including molecular markers to detect the disease early and guide effective treatment, may greatly improve current therapeutic options.34

Prescribing selective anticholinergic and antihistamine pharmacotherapy based on the patient’s specific muscarinic and histamine receptor profile, respectively, may provide greater symptom relief.34 Maintaining the appropriate, individualized therapy could represent a significant advance in treatment for IC/BPS. However, further research on the topic is needed.

On the next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

IC/BPS is a complex multifactorial syndrome that may manifest with disabling pain. Further research on this disease is warranted to help facilitate an earlier, more consistent diagnosis and produce more effective treatment options. Early diagnosis of IC/BPS is essential for successful therapy. Once the diagnosis is made, a cautious regimen of different treatments, following the American Urological Association’s clinical practice guidelines for interstitial cystitis, should be implemented. Patients should also be encouraged to consider specific dietary changes and other lifestyle adjustments under a clinician’s supervision.

The authors wish to thank Carol Hildebrandt for her help in preparing this manuscript and Robert J. Evans, MD, Associate Professor of Urology, Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center, for his editorial expertise.

1. Dasgupta J, Tincello DG. Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: an update. Maturitas. 2009;64:212-217.

2. Hanno PM, Burks DA, Clemens JQ, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: American Urological Association (AUA) Guideline (2011). www.auanet.org/education/guidelines/ic-bladder-pain-syndrome.cfm. Accessed June 5, 2013.

3. Evans RJ; University of Tennessee Advanced Studies in Pharmacy. Pathophysiology and clinical presentation of interstitial cystitis (2005). www.utasip.com/files/articlefiles/pdf/XASIP_Issue_Mar_p8_14.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2013.

4. Sant GR. Etiology, pathogenesis, and diagnosis of interstitial cystitis. Rev Urol. 2002;(4 suppl 1):S9-S15.

5. Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:167-178.

6. van de Merwe JP, Nordling J, Bouchelouche P, et al. Diagnostic criteria, classification, and nomenclature for painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis: an ESSIC proposal. Eur Urol. 2008;53:60-67.

7. Bogart LM, Berry SH, Clemens JQ. Symptoms of interstitial cystitis, painful bladder syndrome and similar diseases in women: a systematic review. J Urol. 2007;177:450-456.

8. Kusek JW, Nyberg LM. The epidemiology of interstitial cystitis: is it time to expand our definition? Urology. 2001;57(6 suppl 1):95-99.

9. Clemens JQ, Meenan RT, Rosetti MC, et al. Prevalence and incidence of interstitial cystitis in a managed care population. J Urol. 2005;173:98-102.

10. Berry SH, Elliott MN, Suttorp M, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis among adult females in the United States. J Urol. 2011;186:540-544.

11. Rosamilia A, Dwyer PL. Pathophysiology of interstitial cystitis. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2000;12:405-410.

12. Grover S, Srivastava A, Lee R, et al. Role of inflammation in bladder function and interstitial cystitis. Ther Adv Urol. 2011;3:19-33.

13. Rosenberg MT, Page S, Hazzard MA. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis in a primary care setting. Urology. 2007;69(4 suppl):S48-S52.

14. Evans RJ. Treatment approaches for interstitial cystitis: multimodality therapy. Rev Urol. 2002;(4 suppl 1):S16-S20.

15. Wesselmann U. Interstitial cystitis: a chronic visceral pain syndrome. Urology. 2001;57(6 suppl 1):102.

16. Hosseini A, Ehrén I, Wiklund NP. Nitric oxide as an objective marker for evaluation of treatment response in patients with classic interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2004;172(6 pt 1):2261-2265.

17. Ho MH, Bhatia NN, Khorram O. Physiologic role of nitric oxide and nitric oxide synthase in female lower urinary tract. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2004;16:423-429.

18. Rosenberg MT, Newman DK, Page SA. Interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome: symptom recognition is key to early identification, treatment. Cleve Clin J Med. 2007;74:854-862.

19. Driscoll A, Teichman JM. How do patients with interstitial cystitis present? J Urol. 2001;166:2118-2120.

20. Parsons CL. Interstitial cystitis: epidemiology and clinical presentation. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45:242-249.

21. Hanno PM, Landis JR, Matthews-Cook Y, et al. The diagnosis of interstitial cystitis revisited: lessons learned from the National Institutes of Health Interstitial Cystitis Database study. J Urol. 1999;161:553-557.

22. Whitmore KE, Theoharides TC. When to suspect interstitial cystitis. J Fam Pract. 2011;60:340-348.

23. Butrick CW, Howard FM, Sand PK. Diagnosis and treatment of interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome: a review. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010;19:1185-1193.

24. O’Leary MP, Sant GR, Fowler FJ Jr, et al. The interstitial cystitis symptom index and problem index. Urology. 1997;49(5A suppl):58-63.

25. Nickel JC. Forensic dissection of a clinical trial: lessons learned in understanding and managing interstitial cystitis. Rev Urol. 2010;12:e78-e85.

26. Anger JT, Zabihi N, Clemens JQ, et al. Treatment choice, duration, and cost in patients with interstitial cystitis and painful bladder syndrome. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:395-400.

27. Nickel JC. Interstitial cystitis: characterization and management of an enigmatic urologic syndrome. Rev Urol. 2002;4:112-121.

28. Dell JR. Interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome: appropriate diagnosis and management. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2007;16:1181-1187.

29. National Kidney and Urologic Diseases Information Clearinghouse. Interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome (2011). NIH Publication No. 11–3220. http://kidney.niddk.nih.gov/kudiseases/pubs/interstitialcystitis/IC_PBS_T_508.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2013.

30. Davis EL, El Khoudary SR, Talbott EO, et al. Safety and efficacy of the use of intravesical and oral pentosan polysulfate sodium for interstitial cystitis: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. J Urol. 2008;179:177-185.

31. Pinto R, Lopes T, Silva J, et al. Persistent therapeutic effect of repeated injections of onabotulinum toxin a in refractory bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 2013;189:548-553.

32. Pinto R, Lopoes T, Frias B, et al. Trigonal injection of botulinum toxin A in patients with refractory bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis. Eur Urol. 2010;58:360-365.

33. Gottsch HP, Miller JL, Yang CC, Berger RE. A pilot study of botulinum toxin for interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011; 30:93-96.

34. Neuhaus J, Schwalenberg T, Horn LC, et al. New aspects in the differential diagnosis and therapy of bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis. Adv Urol. 2011;2011:639479.

1. Dasgupta J, Tincello DG. Interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: an update. Maturitas. 2009;64:212-217.

2. Hanno PM, Burks DA, Clemens JQ, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: American Urological Association (AUA) Guideline (2011). www.auanet.org/education/guidelines/ic-bladder-pain-syndrome.cfm. Accessed June 5, 2013.

3. Evans RJ; University of Tennessee Advanced Studies in Pharmacy. Pathophysiology and clinical presentation of interstitial cystitis (2005). www.utasip.com/files/articlefiles/pdf/XASIP_Issue_Mar_p8_14.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2013.

4. Sant GR. Etiology, pathogenesis, and diagnosis of interstitial cystitis. Rev Urol. 2002;(4 suppl 1):S9-S15.

5. Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:167-178.

6. van de Merwe JP, Nordling J, Bouchelouche P, et al. Diagnostic criteria, classification, and nomenclature for painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis: an ESSIC proposal. Eur Urol. 2008;53:60-67.

7. Bogart LM, Berry SH, Clemens JQ. Symptoms of interstitial cystitis, painful bladder syndrome and similar diseases in women: a systematic review. J Urol. 2007;177:450-456.

8. Kusek JW, Nyberg LM. The epidemiology of interstitial cystitis: is it time to expand our definition? Urology. 2001;57(6 suppl 1):95-99.

9. Clemens JQ, Meenan RT, Rosetti MC, et al. Prevalence and incidence of interstitial cystitis in a managed care population. J Urol. 2005;173:98-102.

10. Berry SH, Elliott MN, Suttorp M, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis among adult females in the United States. J Urol. 2011;186:540-544.

11. Rosamilia A, Dwyer PL. Pathophysiology of interstitial cystitis. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2000;12:405-410.