User login

Woman, 32, With Crusty Red Blisters

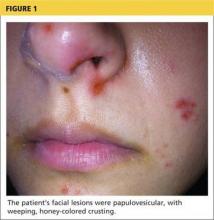

A 32-year-old Korean woman presented with a rash on her scalp, face, palms, soles, and genital region and with sores in the oral cavity. The blisters were red and flat with some crusting, particularly on the scalp and face. The patient described the blisters as very painful, adding that it hurt to walk, grasp objects, and drink fluids. Associated symptoms included painful urination, sore throat, malaise, and fever of up to 103°F. She was taking acetaminophen and ibuprofen to alleviate the fever and pain.

Medical history was unremarkable. Social history was negative for recent changes in sexual partner or travel to foreign countries.

Physical examination revealed numerous flat, erythematous lesions. Lesions on the face and scalp had developed a weeping, honey-colored crust (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). The lesions were tender to the touch, particularly on the palms and soles.

Further questioning revealed that the patient’s 18-month-old son had exhibited similar symptoms two to three days prior to her illness.

Continue for differential diagnosis >>

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Because multiple bacterial and viral diseases manifest in this fashion, the differential diagnosis included the following disorders:

Erythema multiforme. This skin condition may result from an allergic or hypersensitivity reaction to certain drugs or from infections. Infections that can cause erythema multiforme include herpes simplex virus and mycoplasma. Patients present with lesions on the palms (see Figure 3), soles, extremities, face, or trunk. The lesions can appear as a nodule, papule, macule, or vesicle. Initially, in the mild form, the lesions may appear as hives or target-shaped rashes, occurring on the face and acral surfaces. A severe form of erythema multiforme, known as Stevens-Johnson syndrome, is characterized by rash, mucosal involvement, and systemic symptoms.1

Herpes zoster. This viral infection is caused by the varicella-zoster virus, which also causes chicken pox. The virus lies dormant within a single sensory ganglion and may reappear as shingles along the dermatome of that nerve. Patients may experience burning or shooting pain with tingling or itching before the rash appears; vesicular lesions with erythematous bases appear days later. The rash occurs unilaterally on the body or face and does not cross the midline. A viral culture may be obtained for identification.2

Herpetic gingivostomatitis. This infection is most commonly caused by herpes simplex virus type 1, the same virus that causes cold sores. Patients may present with ulcerations along the buccal mucosa and gums. The infection manifests with systemic symptoms, including malaise, fever, irritability, and cervical adenopathy. A viral culture will identify the etiology.3

Impetigo. This skin infection is typically caused by bacteria, predominantly Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, or a combination. Infections generally occur after a break in the skin surface. The most common presentation is a rash that spreads to different parts of the body after scratching. Skin lesions can occur on the face, lips, or extremities. Initially vesicular, the lesions generally form a honey-colored crust after fluid discharge. The clinician should take a skin or fluid sample from the lesion to culture, which may identify the pathogen.4

Syphilis. This sexually transmitted infection is caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. In primary syphilis, patients can develop a painless sore, or chancre, on the genitals, rectal area, or mouth. If left untreated, the disease can progress to secondary syphilis, manifesting as a pale pink or reddish maculopapular rash on the palms and soles. The rash can be associated with fever, sore throat, myalgia, and fatigue. It is important to rule out syphilis because, left untreated, it can lead to cardiac and neurologic complications. Screening tests include VDRL and the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test, both of which assess for antibodies to the organism, and dark field microscopy of ulcerations to identify the organism.5

Also included in the differential diagnosis for the patient’s symptoms was hand-foot-mouth disease (HFMD), discussed below.

Next page: Discussion >>

DISCUSSION

HFMD is an acute viral illness most often affecting children younger than 5 and occurring in summer to early fall months. HFMD manifests with fever and papulovesicular eruptions; lesions often appear in the oral cavity first, spreading to the palms, soles, and buttocks. Route of transmission is usually fecal-oral or through respiratory droplets, oral secretions, or direct contact with fluid-filled vesicles.6-8 The highly contagious nature of the virus causes it to spread to close contacts and family members and leads to outbreaks in schools and daycare centers.9,10

In the United States, the most common etiology of HFMD is coxsackievirus A16.7 Another causative agent, enterovirus 71 (EV71), has been found responsible for HFMD epidemics in southeast Asia and Australia.11,12 Recently, the coxsackievirus A6 (CV A6) strain has been linked to outbreaks of HFMD.7,9 This strain may produce an atypical manifestation of skin lesions on the face, trunk, and extremities. The lesions may also appear larger than usual and have a vesiculobullous rather than the more typical papulovesicular appearance. The course of the illness differs in severity depending on the strain of the virus causing HFMD.9

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

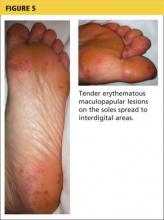

The acute phase of HFMD typically begins with prodromal symptoms such as fever, malaise, and sore throat. Erythematous ulcerations usually appear in the oral cavity first (see Figure 4) and often cause symptoms such as sore throat, dysphagia, or dryness. As the disease progresses, cutaneous lesions spread to the face, extremities, interdigital areas (see Figure 5), trunk, and perianal area (which may cause dysuria). The lesions may initially appear as erythematous macules or papules, transforming to vesicles as the disease progresses. The mucocutaneous lesions are usually asymptomatic but can be tender to touch or pressure and may leak fluid.7,10

In only a few cases—caused by CV A6—have lesions in the scalp been reported; the mechanism of action is unknown.10 Instances of lesions invading the nails have been reported, causing desquamation and shedding. This condition is known as onychomadesis.9,11

Continue for diagnosis >>

DIAGNOSIS

Serologic testing and viral cultures can identify the exact strain of virus causing HFMD and are particularly useful in unusual presentations. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing yields a high sensitivity and specificity for the causative agent. Histologic examination of skin biopsies may show lymphocytic infiltrates and areas of degeneration along the epidermis. However, most cases are diagnosed based on clinical presentation alone.6,12

TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT

Management of HFMD is primarily symptomatic, consisting of supportive care that includes use of antipyretics, NSAIDs, and adequate fluid intake to prevent dehydration. The disease is usually self-limited, resolving within seven to 10 days without sequelae.6,9 Aseptic meningitis and other severe complications (especially pulmonary and neurologic), most often associated with EV71 infection, can occur in vulnerable populations, including elderly, pregnant, and immunocompromised patients.9,11 Because the virus is excreted directly from palmar lesions onto the hands, proper hygiene and handwashing techniques offer an exceptionally strong protective effect, preventing transmission and reducing morbidity.8

PATIENT OUTCOME

Based on clinical findings and patient history, the patient was diagnosed with HFMD, which she contracted from her son. Laboratory testing and viral cultures were deemed unnecessary in this case. Treatment was symptomatic, and her skin lesions resolved in one to two weeks.

At follow-up, the patient stated her skin lesions resolved completely without leaving any scars. She also indicated that her nails peeled and shed approximately four weeks after diagnosis, but began to regrow normally four months after diagnosis.

CONCLUSION

Clinicians need to recognize that, although it is uncommon outside the pediatric population, HFMD may occur in adults with intact immune systems. The presentation of HFMD in adults may be atypical, including cutaneous lesions in the scalp and shedding of the nails several weeks after diagnosis. Depending on the viral strain involved, adult patients may have more severe illness and may take longer to recover. Therefore, early diagnosis is important to help prevent the spread of infection and reduce the severity of complications.

REFERENCES

1. Patel NN, Patel DN. Erythema multiforme syndrome. Am J Med. 2009;122(7):623-625.

2. Bader MS. Herpes zoster: diagnostic, therapeutic, and preventive approaches. Postgrad Med. 2013;125(5):78-91.

3. Avci O, Ertam I. Viral infections of the face. Clin Derm. 2014;32:715-733.

4. Hartman-Adams H, Banvard C, Juckett G. Impetigo: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90(4):229-235.

5. Markle W, Conti T, Kad M. Sexually transmitted diseases. Prim Care Clin Office Pract. 2013;40:557-587.

6. Shin JU, Oh SH, Lee JH. A case of hand-foot-mouth disease in an immunocompetent adult. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22(2):216-218.

7. CDC. Notes from the field: severe hand, foot, and mouth disease associated with coxsackievirus A6 - Alabama, Connecticut, California, and Nevada, November 2011-February 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(12):213-214.

8. Ruan F, Yang T, Ma H, et al. Risk factors for hand, foot, and mouth disease and herpangina and the preventive effect of hand-washing. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):e898-e904.

9. Kaminska K, Martinetti G, Lucchini R, et al. Coxsackievirus A6 and hand, foot and mouth Disease: three case reports of familial child-to-immunocompetent adult transmission and a literature review. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013;5(2):203-209.

10. Lønnberg AS, Elberling J, Fischer TK, Skov L. Two cases of hand, foot, and mouth disease involving the scalp. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93(4):467-468.

11. Osterback R, Vuorinen T, Linna M, et al. Coxsackievirus A6 and hand, foot, and mouth disease, Finland. Emerging Infect Dis. 2009;15(9):1485-1488.

12. Shea YF, Chan CY, Hung IFN, Chan KH. Hand, foot and mouth disease in an immunocompetent adult due to Coxsackievirus A6. Hong Kong Med J. 2013;19(3):262-264.

A 32-year-old Korean woman presented with a rash on her scalp, face, palms, soles, and genital region and with sores in the oral cavity. The blisters were red and flat with some crusting, particularly on the scalp and face. The patient described the blisters as very painful, adding that it hurt to walk, grasp objects, and drink fluids. Associated symptoms included painful urination, sore throat, malaise, and fever of up to 103°F. She was taking acetaminophen and ibuprofen to alleviate the fever and pain.

Medical history was unremarkable. Social history was negative for recent changes in sexual partner or travel to foreign countries.

Physical examination revealed numerous flat, erythematous lesions. Lesions on the face and scalp had developed a weeping, honey-colored crust (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). The lesions were tender to the touch, particularly on the palms and soles.

Further questioning revealed that the patient’s 18-month-old son had exhibited similar symptoms two to three days prior to her illness.

Continue for differential diagnosis >>

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Because multiple bacterial and viral diseases manifest in this fashion, the differential diagnosis included the following disorders:

Erythema multiforme. This skin condition may result from an allergic or hypersensitivity reaction to certain drugs or from infections. Infections that can cause erythema multiforme include herpes simplex virus and mycoplasma. Patients present with lesions on the palms (see Figure 3), soles, extremities, face, or trunk. The lesions can appear as a nodule, papule, macule, or vesicle. Initially, in the mild form, the lesions may appear as hives or target-shaped rashes, occurring on the face and acral surfaces. A severe form of erythema multiforme, known as Stevens-Johnson syndrome, is characterized by rash, mucosal involvement, and systemic symptoms.1

Herpes zoster. This viral infection is caused by the varicella-zoster virus, which also causes chicken pox. The virus lies dormant within a single sensory ganglion and may reappear as shingles along the dermatome of that nerve. Patients may experience burning or shooting pain with tingling or itching before the rash appears; vesicular lesions with erythematous bases appear days later. The rash occurs unilaterally on the body or face and does not cross the midline. A viral culture may be obtained for identification.2

Herpetic gingivostomatitis. This infection is most commonly caused by herpes simplex virus type 1, the same virus that causes cold sores. Patients may present with ulcerations along the buccal mucosa and gums. The infection manifests with systemic symptoms, including malaise, fever, irritability, and cervical adenopathy. A viral culture will identify the etiology.3

Impetigo. This skin infection is typically caused by bacteria, predominantly Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, or a combination. Infections generally occur after a break in the skin surface. The most common presentation is a rash that spreads to different parts of the body after scratching. Skin lesions can occur on the face, lips, or extremities. Initially vesicular, the lesions generally form a honey-colored crust after fluid discharge. The clinician should take a skin or fluid sample from the lesion to culture, which may identify the pathogen.4

Syphilis. This sexually transmitted infection is caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. In primary syphilis, patients can develop a painless sore, or chancre, on the genitals, rectal area, or mouth. If left untreated, the disease can progress to secondary syphilis, manifesting as a pale pink or reddish maculopapular rash on the palms and soles. The rash can be associated with fever, sore throat, myalgia, and fatigue. It is important to rule out syphilis because, left untreated, it can lead to cardiac and neurologic complications. Screening tests include VDRL and the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test, both of which assess for antibodies to the organism, and dark field microscopy of ulcerations to identify the organism.5

Also included in the differential diagnosis for the patient’s symptoms was hand-foot-mouth disease (HFMD), discussed below.

Next page: Discussion >>

DISCUSSION

HFMD is an acute viral illness most often affecting children younger than 5 and occurring in summer to early fall months. HFMD manifests with fever and papulovesicular eruptions; lesions often appear in the oral cavity first, spreading to the palms, soles, and buttocks. Route of transmission is usually fecal-oral or through respiratory droplets, oral secretions, or direct contact with fluid-filled vesicles.6-8 The highly contagious nature of the virus causes it to spread to close contacts and family members and leads to outbreaks in schools and daycare centers.9,10

In the United States, the most common etiology of HFMD is coxsackievirus A16.7 Another causative agent, enterovirus 71 (EV71), has been found responsible for HFMD epidemics in southeast Asia and Australia.11,12 Recently, the coxsackievirus A6 (CV A6) strain has been linked to outbreaks of HFMD.7,9 This strain may produce an atypical manifestation of skin lesions on the face, trunk, and extremities. The lesions may also appear larger than usual and have a vesiculobullous rather than the more typical papulovesicular appearance. The course of the illness differs in severity depending on the strain of the virus causing HFMD.9

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The acute phase of HFMD typically begins with prodromal symptoms such as fever, malaise, and sore throat. Erythematous ulcerations usually appear in the oral cavity first (see Figure 4) and often cause symptoms such as sore throat, dysphagia, or dryness. As the disease progresses, cutaneous lesions spread to the face, extremities, interdigital areas (see Figure 5), trunk, and perianal area (which may cause dysuria). The lesions may initially appear as erythematous macules or papules, transforming to vesicles as the disease progresses. The mucocutaneous lesions are usually asymptomatic but can be tender to touch or pressure and may leak fluid.7,10

In only a few cases—caused by CV A6—have lesions in the scalp been reported; the mechanism of action is unknown.10 Instances of lesions invading the nails have been reported, causing desquamation and shedding. This condition is known as onychomadesis.9,11

Continue for diagnosis >>

DIAGNOSIS

Serologic testing and viral cultures can identify the exact strain of virus causing HFMD and are particularly useful in unusual presentations. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing yields a high sensitivity and specificity for the causative agent. Histologic examination of skin biopsies may show lymphocytic infiltrates and areas of degeneration along the epidermis. However, most cases are diagnosed based on clinical presentation alone.6,12

TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT

Management of HFMD is primarily symptomatic, consisting of supportive care that includes use of antipyretics, NSAIDs, and adequate fluid intake to prevent dehydration. The disease is usually self-limited, resolving within seven to 10 days without sequelae.6,9 Aseptic meningitis and other severe complications (especially pulmonary and neurologic), most often associated with EV71 infection, can occur in vulnerable populations, including elderly, pregnant, and immunocompromised patients.9,11 Because the virus is excreted directly from palmar lesions onto the hands, proper hygiene and handwashing techniques offer an exceptionally strong protective effect, preventing transmission and reducing morbidity.8

PATIENT OUTCOME

Based on clinical findings and patient history, the patient was diagnosed with HFMD, which she contracted from her son. Laboratory testing and viral cultures were deemed unnecessary in this case. Treatment was symptomatic, and her skin lesions resolved in one to two weeks.

At follow-up, the patient stated her skin lesions resolved completely without leaving any scars. She also indicated that her nails peeled and shed approximately four weeks after diagnosis, but began to regrow normally four months after diagnosis.

CONCLUSION

Clinicians need to recognize that, although it is uncommon outside the pediatric population, HFMD may occur in adults with intact immune systems. The presentation of HFMD in adults may be atypical, including cutaneous lesions in the scalp and shedding of the nails several weeks after diagnosis. Depending on the viral strain involved, adult patients may have more severe illness and may take longer to recover. Therefore, early diagnosis is important to help prevent the spread of infection and reduce the severity of complications.

REFERENCES

1. Patel NN, Patel DN. Erythema multiforme syndrome. Am J Med. 2009;122(7):623-625.

2. Bader MS. Herpes zoster: diagnostic, therapeutic, and preventive approaches. Postgrad Med. 2013;125(5):78-91.

3. Avci O, Ertam I. Viral infections of the face. Clin Derm. 2014;32:715-733.

4. Hartman-Adams H, Banvard C, Juckett G. Impetigo: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90(4):229-235.

5. Markle W, Conti T, Kad M. Sexually transmitted diseases. Prim Care Clin Office Pract. 2013;40:557-587.

6. Shin JU, Oh SH, Lee JH. A case of hand-foot-mouth disease in an immunocompetent adult. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22(2):216-218.

7. CDC. Notes from the field: severe hand, foot, and mouth disease associated with coxsackievirus A6 - Alabama, Connecticut, California, and Nevada, November 2011-February 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(12):213-214.

8. Ruan F, Yang T, Ma H, et al. Risk factors for hand, foot, and mouth disease and herpangina and the preventive effect of hand-washing. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):e898-e904.

9. Kaminska K, Martinetti G, Lucchini R, et al. Coxsackievirus A6 and hand, foot and mouth Disease: three case reports of familial child-to-immunocompetent adult transmission and a literature review. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013;5(2):203-209.

10. Lønnberg AS, Elberling J, Fischer TK, Skov L. Two cases of hand, foot, and mouth disease involving the scalp. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93(4):467-468.

11. Osterback R, Vuorinen T, Linna M, et al. Coxsackievirus A6 and hand, foot, and mouth disease, Finland. Emerging Infect Dis. 2009;15(9):1485-1488.

12. Shea YF, Chan CY, Hung IFN, Chan KH. Hand, foot and mouth disease in an immunocompetent adult due to Coxsackievirus A6. Hong Kong Med J. 2013;19(3):262-264.

A 32-year-old Korean woman presented with a rash on her scalp, face, palms, soles, and genital region and with sores in the oral cavity. The blisters were red and flat with some crusting, particularly on the scalp and face. The patient described the blisters as very painful, adding that it hurt to walk, grasp objects, and drink fluids. Associated symptoms included painful urination, sore throat, malaise, and fever of up to 103°F. She was taking acetaminophen and ibuprofen to alleviate the fever and pain.

Medical history was unremarkable. Social history was negative for recent changes in sexual partner or travel to foreign countries.

Physical examination revealed numerous flat, erythematous lesions. Lesions on the face and scalp had developed a weeping, honey-colored crust (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). The lesions were tender to the touch, particularly on the palms and soles.

Further questioning revealed that the patient’s 18-month-old son had exhibited similar symptoms two to three days prior to her illness.

Continue for differential diagnosis >>

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Because multiple bacterial and viral diseases manifest in this fashion, the differential diagnosis included the following disorders:

Erythema multiforme. This skin condition may result from an allergic or hypersensitivity reaction to certain drugs or from infections. Infections that can cause erythema multiforme include herpes simplex virus and mycoplasma. Patients present with lesions on the palms (see Figure 3), soles, extremities, face, or trunk. The lesions can appear as a nodule, papule, macule, or vesicle. Initially, in the mild form, the lesions may appear as hives or target-shaped rashes, occurring on the face and acral surfaces. A severe form of erythema multiforme, known as Stevens-Johnson syndrome, is characterized by rash, mucosal involvement, and systemic symptoms.1

Herpes zoster. This viral infection is caused by the varicella-zoster virus, which also causes chicken pox. The virus lies dormant within a single sensory ganglion and may reappear as shingles along the dermatome of that nerve. Patients may experience burning or shooting pain with tingling or itching before the rash appears; vesicular lesions with erythematous bases appear days later. The rash occurs unilaterally on the body or face and does not cross the midline. A viral culture may be obtained for identification.2

Herpetic gingivostomatitis. This infection is most commonly caused by herpes simplex virus type 1, the same virus that causes cold sores. Patients may present with ulcerations along the buccal mucosa and gums. The infection manifests with systemic symptoms, including malaise, fever, irritability, and cervical adenopathy. A viral culture will identify the etiology.3

Impetigo. This skin infection is typically caused by bacteria, predominantly Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, or a combination. Infections generally occur after a break in the skin surface. The most common presentation is a rash that spreads to different parts of the body after scratching. Skin lesions can occur on the face, lips, or extremities. Initially vesicular, the lesions generally form a honey-colored crust after fluid discharge. The clinician should take a skin or fluid sample from the lesion to culture, which may identify the pathogen.4

Syphilis. This sexually transmitted infection is caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. In primary syphilis, patients can develop a painless sore, or chancre, on the genitals, rectal area, or mouth. If left untreated, the disease can progress to secondary syphilis, manifesting as a pale pink or reddish maculopapular rash on the palms and soles. The rash can be associated with fever, sore throat, myalgia, and fatigue. It is important to rule out syphilis because, left untreated, it can lead to cardiac and neurologic complications. Screening tests include VDRL and the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test, both of which assess for antibodies to the organism, and dark field microscopy of ulcerations to identify the organism.5

Also included in the differential diagnosis for the patient’s symptoms was hand-foot-mouth disease (HFMD), discussed below.

Next page: Discussion >>

DISCUSSION

HFMD is an acute viral illness most often affecting children younger than 5 and occurring in summer to early fall months. HFMD manifests with fever and papulovesicular eruptions; lesions often appear in the oral cavity first, spreading to the palms, soles, and buttocks. Route of transmission is usually fecal-oral or through respiratory droplets, oral secretions, or direct contact with fluid-filled vesicles.6-8 The highly contagious nature of the virus causes it to spread to close contacts and family members and leads to outbreaks in schools and daycare centers.9,10

In the United States, the most common etiology of HFMD is coxsackievirus A16.7 Another causative agent, enterovirus 71 (EV71), has been found responsible for HFMD epidemics in southeast Asia and Australia.11,12 Recently, the coxsackievirus A6 (CV A6) strain has been linked to outbreaks of HFMD.7,9 This strain may produce an atypical manifestation of skin lesions on the face, trunk, and extremities. The lesions may also appear larger than usual and have a vesiculobullous rather than the more typical papulovesicular appearance. The course of the illness differs in severity depending on the strain of the virus causing HFMD.9

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The acute phase of HFMD typically begins with prodromal symptoms such as fever, malaise, and sore throat. Erythematous ulcerations usually appear in the oral cavity first (see Figure 4) and often cause symptoms such as sore throat, dysphagia, or dryness. As the disease progresses, cutaneous lesions spread to the face, extremities, interdigital areas (see Figure 5), trunk, and perianal area (which may cause dysuria). The lesions may initially appear as erythematous macules or papules, transforming to vesicles as the disease progresses. The mucocutaneous lesions are usually asymptomatic but can be tender to touch or pressure and may leak fluid.7,10

In only a few cases—caused by CV A6—have lesions in the scalp been reported; the mechanism of action is unknown.10 Instances of lesions invading the nails have been reported, causing desquamation and shedding. This condition is known as onychomadesis.9,11

Continue for diagnosis >>

DIAGNOSIS

Serologic testing and viral cultures can identify the exact strain of virus causing HFMD and are particularly useful in unusual presentations. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing yields a high sensitivity and specificity for the causative agent. Histologic examination of skin biopsies may show lymphocytic infiltrates and areas of degeneration along the epidermis. However, most cases are diagnosed based on clinical presentation alone.6,12

TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT

Management of HFMD is primarily symptomatic, consisting of supportive care that includes use of antipyretics, NSAIDs, and adequate fluid intake to prevent dehydration. The disease is usually self-limited, resolving within seven to 10 days without sequelae.6,9 Aseptic meningitis and other severe complications (especially pulmonary and neurologic), most often associated with EV71 infection, can occur in vulnerable populations, including elderly, pregnant, and immunocompromised patients.9,11 Because the virus is excreted directly from palmar lesions onto the hands, proper hygiene and handwashing techniques offer an exceptionally strong protective effect, preventing transmission and reducing morbidity.8

PATIENT OUTCOME

Based on clinical findings and patient history, the patient was diagnosed with HFMD, which she contracted from her son. Laboratory testing and viral cultures were deemed unnecessary in this case. Treatment was symptomatic, and her skin lesions resolved in one to two weeks.

At follow-up, the patient stated her skin lesions resolved completely without leaving any scars. She also indicated that her nails peeled and shed approximately four weeks after diagnosis, but began to regrow normally four months after diagnosis.

CONCLUSION

Clinicians need to recognize that, although it is uncommon outside the pediatric population, HFMD may occur in adults with intact immune systems. The presentation of HFMD in adults may be atypical, including cutaneous lesions in the scalp and shedding of the nails several weeks after diagnosis. Depending on the viral strain involved, adult patients may have more severe illness and may take longer to recover. Therefore, early diagnosis is important to help prevent the spread of infection and reduce the severity of complications.

REFERENCES

1. Patel NN, Patel DN. Erythema multiforme syndrome. Am J Med. 2009;122(7):623-625.

2. Bader MS. Herpes zoster: diagnostic, therapeutic, and preventive approaches. Postgrad Med. 2013;125(5):78-91.

3. Avci O, Ertam I. Viral infections of the face. Clin Derm. 2014;32:715-733.

4. Hartman-Adams H, Banvard C, Juckett G. Impetigo: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90(4):229-235.

5. Markle W, Conti T, Kad M. Sexually transmitted diseases. Prim Care Clin Office Pract. 2013;40:557-587.

6. Shin JU, Oh SH, Lee JH. A case of hand-foot-mouth disease in an immunocompetent adult. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22(2):216-218.

7. CDC. Notes from the field: severe hand, foot, and mouth disease associated with coxsackievirus A6 - Alabama, Connecticut, California, and Nevada, November 2011-February 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(12):213-214.

8. Ruan F, Yang T, Ma H, et al. Risk factors for hand, foot, and mouth disease and herpangina and the preventive effect of hand-washing. Pediatrics. 2011;127(4):e898-e904.

9. Kaminska K, Martinetti G, Lucchini R, et al. Coxsackievirus A6 and hand, foot and mouth Disease: three case reports of familial child-to-immunocompetent adult transmission and a literature review. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013;5(2):203-209.

10. Lønnberg AS, Elberling J, Fischer TK, Skov L. Two cases of hand, foot, and mouth disease involving the scalp. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93(4):467-468.

11. Osterback R, Vuorinen T, Linna M, et al. Coxsackievirus A6 and hand, foot, and mouth disease, Finland. Emerging Infect Dis. 2009;15(9):1485-1488.

12. Shea YF, Chan CY, Hung IFN, Chan KH. Hand, foot and mouth disease in an immunocompetent adult due to Coxsackievirus A6. Hong Kong Med J. 2013;19(3):262-264.

Peanut Allergy Awareness

Among all persons with food allergies, those who are allergic to peanuts are at greatest risk for anaphylactic symptoms.1 About 30,000 cases of food allergy–related anaphylaxis are seen in the nation’s emergency departments (EDs) each year, and the food most commonly responsible is peanuts.2 What can primary care providers do to reduce the number of peanut allergy–associated anaphylactic reactions and fatalities, both in the ED and in the larger community?

According to a guideline from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID),3 prevalence of peanut allergy is about 0.6% of the US population, although in an 11-year survey involving more than 13,000 respondents, Sicherer et al4 reported allergy to peanuts, tree nuts, or both in 1.4%, possibly translating to some three million Americans; British researchers have reported peanut allergy in 1.8% of an 1,100-member children’s cohort.5 The risk of exposure to peanuts and the associated risk for severe and possibly fatal anaphylaxis present a lifelong struggle for both patient and family.

ETIOLOGY OF PEANUT ALLERGIES

Food allergy prevalence has reportedly doubled in recent decades, with a significant increase also seen in allergy severity.6 Allergies involving eggs, nuts, fish, milk, and other foods represent the leading cause of hospital-treated anaphylaxis throughout the world.1 Unlike other allergenic foods that affect only one age-group, peanuts are among the foods that trigger the “vast majority” of allergic reactions in young children, teenagers, and adults alike.3

Increases in reported episodes of peanut allergy reactions may be occurring for several reasons:

• Many people have adopted vegetarian diets, and nuts are considered a good protein source6

• Environmental exposures are increasingly common

• More people are genetically vulnerable, as the role of family history becomes clearer

• Food preparation methods (eg, shared processing equipment, contaminated raw materials, formulation errors) and inaccurate labeling lead to accidental exposures7,8

• Exposure to nuts in utero or during breastfeeding is more common.9 Nowak-Wegrzyn and Sampson6 point to the promotion of peanut butter as an economical, nutritious food source for children and for women during pregnancy and lactation; mothers’ consumption of peanuts more than once a week during pregnancy and lactation have been linked to overexposure for their children.9

Other trends that may contribute to peanut allergy prevalence are the early introduction of solid foods in the infant diet and the use of skin products that contain peanut oil.6

Environment and Genetics

The body of knowledge regarding the specific causes of peanut allergy is increasing constantly. Several known peanut proteins (Ara h1, Ara h2, Ara h3, Ara h6, Ara h7, and Ara h9; Ara h8 is a homologous allergen that may account for peanut/birch cross-reactivity) are thought to be responsible for the initial sensitization to peanuts in vulnerable persons, triggering the associated immunoglobulin E (IgE)–mediated response.10-12 Approximately 75% of known peanut-allergic patients will react to these proteins on their first ingestion after being sensitized.9

Since IgE antibodies do not cross the placenta, it is believed that sensitization to peanut proteins must occur in utero or through breast milk. This form of sensitization predisposes these patients to the initial life-threatening anaphylactic reaction.9

There is strong evidence that genetic factors may play a role in peanut allergies.2 In a study of 58 pairs of twins by Sicherer et al,13 heritability of peanut allergy was estimated at 82%, with 64% of monozygotic pairs, versus 7% of dizygotic pairs, showing concordance for peanut allergy. However, the genetic loci that may be responsible for specific food allergies have not yet been identified.2

It is believed that manifestations of food allergy are very similar to those of asthma and atopic dermatitis. According to Green and colleagues,14 82% of peanut-allergic children who visited a referral clinic also had atopic dermatitis. These conditions appear to be triggered by similar mechanisms, mediated by both environmental and genetic factors.2,14-16 Hong et al2 are optimistic about the advances being made in food allergy genetics. Increased understanding, they feel, may lead to new treatment options for potentially fatal food allergies.2

PATIENT PRESENTATION AND HISTORY

As with any IgE-mediated immune response, the patient must have been exposed to the allergen in question. Most patients present with a history of having ingested raw or boiled peanuts and/or foods produced in a facility that also processes nuts.1,18 Clinical symptoms of peanut allergy may develop within seconds of ingestion. For some patients, consumption of as little as 5 to 50 mg of peanut protein can trigger symptoms.19 (A single peanut from a jar of commercially processed peanuts contains approximately 300 mg of potentially allergenic protein.1)

Typically, the most dramatically affected patients have a medical history of asthma or other IgE-mediated immune reactions.1 In one study, young adults with IgE-mediated peanut allergy were found at especially high risk for severe anaphylaxis.6 Seventy-five percent of patients who have a reaction to peanuts do so following their first ingestion (after the initial exposure).

The mean patient age for a diagnosis of peanut allergy is about 14 months; only 20% of the patients diagnosed with a peanut allergy (most likely those with a baseline peanut-specific serum IgE level 18) will outgrow it by the time they reach school age.18,20 Those who do should be encouraged to consume peanuts on a regular basis; according to Byrne et al,21 8% of patients with allergy resolution experience recurrence, a possible result of infrequent peanut consumption.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Patients with peanut allergies can present with a range of symptoms, possibly involving cutaneous, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and/or respiratory systems (see Table 115,22). The more notable symptoms, possibly developing within 15 minutes of exposure, are progressive upper and lower respiratory difficulties, vomiting, diarrhea, hypotension, edema of the face and hands, arrhythmia, throat tightness (in serious cases, approaching anaphylaxis), and possibly loss of consciousness. Such severe reactions often occur in the child who has ingested raw peanuts or tree nuts.22

Milder physical exam findings include erythema, pruritus, conjunctivitis, abdominal pain, nasal congestion, itchy throat, and sneezing. These reactions may have been triggered by foods produced in a facility that also processes nuts, household utensils used to prepare foods that contain nuts, or cross-contamination from another child.9,15,24

DIAGNOSTIC WORK-UP

The diagnosis of a patient with a peanut allergy is made through thorough history taking, careful physical examination, allergy testing with either a skin prick test (SPT) or serum-specific IgE, and oral food challenges. The gold standard for diagnosing food allergy is the double-blind, placebo-controlled oral food challenge,2,25-27 as this test alone can determine the amount of peanut protein needed to trigger a reaction in the given patient.9 However, this is a difficult test to administer and must be performed under strict medical supervision.21

It has been determined that a wheal size of 8.0 mm or greater on the SPT has a 95% to 100% positive predictive value for peanut allergy.1,26,27 Although conflicting results have been reported in some patients between SPT and the oral food challenge, a negative SPT result is considered useful for excluding IgE-mediated allergic responses.22

Researchers examining the peanut-specific serum IgE have demonstrated a 95% to 99% positive predictive value when serum levels exceed 15 kU/L.26,27 This cutoff value in peanut allergy patients is considered suggestive of allergic reactivity, although negative results on an oral food challenge have been reported in more than 25% of children with serum levels exceeding the cutoff.25-27 Testing may have been to whole peanut extract rather than the molecular components (eg, Ara h8).11,12

This past summer, the FDA approved a component test that detects allergen components that include Ara h1, h2, h3, h8, and h9.11,12 Another specific version of the serum IgE test has been in development, one that measures the patient’s IgE reactions to the Ara h2 and Ara h8 components in peanut protein. Johnson and colleagues10,28 have found an increasing level of serum IgE anti–Ara h2 in children who were unable to pass the oral peanut challenge, whereas serum IgE anti–Ara h8 was higher in those who did pass the challenge.28

DIAGNOSING ANAPHYLAXIS

The manifestation of anaphylaxis in patients allergic to peanuts or tree nuts can be life-threatening.29 Symptoms include intense pruritus with flushing of the skin, urticaria, and angioedema, upper-respiratory obstruction resulting from laryngeal edema, and hypotension.30 The clinical criteria for diagnosing anaphylaxis can be found in Table 2.30,31

It is important to recognize the signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis in patients with a peanut allergy; many patients who present to the ED represent first-time reactions. Among patients with life-threatening symptoms on initial reaction, 71% will have similarly severe reactions in subsequent episodes (compared with 44% of patients whose first reaction was not life-threatening).3

TREATMENT, INCLUDING PATIENT EDUCATION

Currently there is no cure for peanut allergy, and no appropriate therapies yet exist to reduce allergy severity. Modest gains have been reported in raising tolerance threshold levels through peanut oral immunotherapy—a long, painstaking process.19,21,32 For now, treatment for peanut allergy is directed at controlling symptoms, once a reaction has occurred. Therefore, the clinician’s goal is to educate peanut-allergic patients and their families on avoiding accidental peanut ingestion, recognizing signs and symptoms of an allergic reaction, and preparing an emergency plan.4

Because four in five patients can expect peanut allergy to last for a lifetime,18,20 strict avoidance of peanuts and peanut products is essential—though difficult because of accidental exposure to food allergens (for example, when dining in restaurants or purchasing bakery products22,32), cross-contamination (as can occur when a food preparation area is not properly cleaned), and allergen cross-reactivity (such as consumption of other legumes).1 Patients must be taught to read food labels carefully for possible hidden sources of peanuts (see Table 37,8); in some cases, product labels bear helpful advisory wording, such as “may contain peanuts.”34,35 US legislation mandates that listed ingredients on food packaging include the eight foods that account for 90% of allergic reactions:

• Peanuts

• Tree nuts

• Egg

• Milk

• Wheat

• Soybeans

• Fish

• Crustacean shellfish.34

Treatment for Anaphylaxis

In pediatric patients, administration of epinephrine is the definitive treatment for anaphylaxis; both the child and parents should carry an epinephrine self-injection device at all times in the event of accidental peanut ingestion. These devices are available in two strengths, based on the child’s weight, and expiration dates should be noted with care. Correct use of the epinephrine self-injection device should be reviewed at each office visit.6

Early-stage allergic reactions can be managed by oral antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine (1 mg/kg body weight up to 75 mg) and an intramuscular injection of epinephrine.1 Prompt transport to the ED should follow (see “Management of Anaphylaxis in the ED”1,9).

PREVENTION

A 2010 expert panel on diagnosis and management of food allergy sponsored by the NIAID, NIH,3 does not advise women to restrict their diet during pregnancy and lactation. Similarly, the United Kingdom’s Department of Health and the Food Standards Agency (DHFSA)36,37 does not support the belief that eating peanuts and peanut-containing foods during pregnancy correlates with a child’s potential for developing a peanut allergy.

The DHFSA does recommend breastfeeding infants for the first six months, if possible, and that mothers refrain from introducing peanut-containing foods during that time. They also recommend that foods associated with a high risk for allergy be introduced into a child’s diet one at a time, to make it easier to identify any allergenic substance.36,37

Lastly, the DHFSA advises parents with a family history of peanut allergy to introduce peanuts only after consulting with their health care provider. The same consideration is advised if a child has already been diagnosed with another allergy.34 According to the American Academy of Pediatrics,6,38 children at high risk for food allergy (eg, atopic disease in both parents or one parent and one sibling) should be breastfed or be given hypoallergenic formula until age 1 year, with no solid foods before age 6 months; peanut-containing foods should not be given before age 3 or 4 years.

CONCLUSION

Peanut allergy can present a lifelong battle for affected patients. Eating one peanut or being exposed even to minute amounts of peanut protein could mean life or death without appropriate management. Reading food labels carefully, preparing peanut-free foods, recognizing the signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis, and obtaining the necessary treatment when allergic reactions occur are essential for peanut-allergic patients and their families.

REFERENCES

1. Burks AW. Peanut allergy. Lancet. 2008;371 (9623):1538-1546.

2. Hong X, Tsai HJ, Wang X. Genetics of food allergy. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21(6):770-776.

3. Boyce JA, Assa’ad A, Burks AW, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(6 suppl):S1-S58.

4. Sicherer S, Muñoz-Furlong A, Godbold JH, Sampson HA. US prevalence of self-reported peanut, tree nut, and sesame allergy: 11-year follow-up. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(6):1322-1326.

5. Hourihane JO, Aiken R, Briggs R, et al. The impact of government advice to pregnant mothers regarding peanut avoidance on the prevalence of peanut allergy in United Kingdom children at school entry. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;312(5):1197-1202.

6. Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Sampson HA. Adverse reactions to foods. Med Clin North Am. 2006;90(1):97-127.

7. Puglisi G, Frieri M. Update on hidden food allergens and food labeling. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2007;28(6):634-639.

8. Hefle SL. Hidden food allergens. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;1(3):269-271.

9. Lee CW, Sheffer AL. Peanut allergy. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2003;24(4):259-264.

10. Boughton B. New test for peanut allergy a step forward. www.medscape.com/viewarticle/740133. Accessed November 16, 2011.

11. Asarnoj A, Movérare R, Östblom E, et al. IgE to peanut allergen components: relation to peanut symptoms and pollen sensitization in 8-year-olds. Allergy. 2010;65(9):1189-1195.

12. Codreanu F, Collignon O, Roitel O, et al. A novel immunoassay using recombinant allergens simplifies peanut allergy diagnosis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2011;154(3):216-226.

13. Sicherer SH, Furlong TJ, Maes HH, et al. Genetics of peanut allergy: a twin study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106(1 pt 1):53-56.

14. Green TD, LaBelle VS, Steele PH, et al. Clinical characteristics of peanut-allergic children: recent changes. Pediatrics. 2007;120(6):1304-1310.

15. Al-ahmed N, Alsowaidi S, Vadas P. Peanut allergy: an overview. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2008;4(4):139-143.

16. Björkstén B. Genetic and environmental risk factors for the development of food allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;5(3):249-253.

17. Lack G. Epidemiologic risks for food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(6):1331-1336.

18. Skolnick HS, Conover-Walker MK, Koerner CB, et al. The natural history of peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107(2):367-374.

19. Clark AT, Islam S, King Y, et al. Successful oral tolerance induction in severe peanut allergy. Allergy. 2009;64(8):1218-1220.

20. Busse PJ, Nowak-Wegrzyn AH, Noone SA, et al. Recurrent peanut allergy. N Engl J Med. 2002; 347(19):1535-1536.

21. Byrne AM, Malka-Rais J, Burks AW, Fleischer DM. How do we know when peanut and tree nut allergy have resolved, and how do we keep it resolved? Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;49(9):1303-1311.

22. Sampson HA. Update on food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(5):805-819.

23. Furlong TJ, Desimone J, Sicherer SH. Peanut and tree nut allergic reactions in restaurants and other establishments. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108(5):866-870.

24. Nelson HS, Lahr J, Rule R, et al. Treatment of anaphylactic sensitivity to peanuts by immunotherapy with injections of aqueous peanut extract. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99(6 pt 1):744-751.

25. Du Toit G, Santos A, Roberts G, et al. The diagnosis of IgE-mediated food allergy in childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2009;20(4):309-319.

26. Roberts G, Lack G. Diagnosing peanut allergy with skin prick and specific IgE testing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(6):1291-1296.

27. Wainstein BK, Yee A, Jelley D, et al. Combining skin prick, immediate skin application and specific-IgE testing in the diagnosis of peanut allergy in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2007;18(3):231-239.

28. Johnson K, Keet C, Hamilton R, Wood R. Predictive value of peanut component specific IgE in a clinical population. Presented at: 2011 Annual Meeting, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; March 19, 2011; San Francisco, CA. Abstract 267.

29. Sheffer AL. Allergen avoidance to reduce asthma-related morbidity. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(11):1134-1136.

30. Russell S, Monroe K, Losek JD. Anaphylaxis management in the pediatric emergency department: opportunities for improvement. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26(2):71-76.

31. Sampson HA, Munoz-Furlong A, Campbell RL, et al. Second symposium on the definition and management of anaphylaxis: summary report—Second National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network symposium. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(2):391-397.

32. Blumchen K, Ulbricht H, Staden U, et al. Oral peanut immunotherapy in children with peanut anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 126(1):83-91.

33. Yu JW, Kagan R, Verreault N, et al. Accidental ingestions in children with peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118(2):466-472.

34. Taylor SL, Hefle SL. Food allergen labeling in the USA and Europe. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;6(3):186-190.

35. Sampson HA, Srivastava K, Li XM, Burks AW. New perspectives for the treatment of food allergy (peanut). Arb Paul Ehrlich Inst Bundesamt Sera Impfstoffe Frankf A M. 2003;(94):236-244.

36. McLean S, Sheikh A. Does avoidance of peanuts in early life reduce the risk of peanut allergy? BMJ. 2010 Mar 11;340:c424.

37. Department of Health. Revised government advice on consumption of peanut during pregnancy, breastfeeding, and early life and development of peanut allergy (Aug 2009). www.dh.gov.uk/en/Healthcare/Children/Maternity/Maternalandinfantnutrition/DH_104490. Accessed November 16, 2011.

38. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Nutrition. Hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2):346-349.

Among all persons with food allergies, those who are allergic to peanuts are at greatest risk for anaphylactic symptoms.1 About 30,000 cases of food allergy–related anaphylaxis are seen in the nation’s emergency departments (EDs) each year, and the food most commonly responsible is peanuts.2 What can primary care providers do to reduce the number of peanut allergy–associated anaphylactic reactions and fatalities, both in the ED and in the larger community?

According to a guideline from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID),3 prevalence of peanut allergy is about 0.6% of the US population, although in an 11-year survey involving more than 13,000 respondents, Sicherer et al4 reported allergy to peanuts, tree nuts, or both in 1.4%, possibly translating to some three million Americans; British researchers have reported peanut allergy in 1.8% of an 1,100-member children’s cohort.5 The risk of exposure to peanuts and the associated risk for severe and possibly fatal anaphylaxis present a lifelong struggle for both patient and family.

ETIOLOGY OF PEANUT ALLERGIES

Food allergy prevalence has reportedly doubled in recent decades, with a significant increase also seen in allergy severity.6 Allergies involving eggs, nuts, fish, milk, and other foods represent the leading cause of hospital-treated anaphylaxis throughout the world.1 Unlike other allergenic foods that affect only one age-group, peanuts are among the foods that trigger the “vast majority” of allergic reactions in young children, teenagers, and adults alike.3

Increases in reported episodes of peanut allergy reactions may be occurring for several reasons:

• Many people have adopted vegetarian diets, and nuts are considered a good protein source6

• Environmental exposures are increasingly common

• More people are genetically vulnerable, as the role of family history becomes clearer

• Food preparation methods (eg, shared processing equipment, contaminated raw materials, formulation errors) and inaccurate labeling lead to accidental exposures7,8

• Exposure to nuts in utero or during breastfeeding is more common.9 Nowak-Wegrzyn and Sampson6 point to the promotion of peanut butter as an economical, nutritious food source for children and for women during pregnancy and lactation; mothers’ consumption of peanuts more than once a week during pregnancy and lactation have been linked to overexposure for their children.9

Other trends that may contribute to peanut allergy prevalence are the early introduction of solid foods in the infant diet and the use of skin products that contain peanut oil.6

Environment and Genetics

The body of knowledge regarding the specific causes of peanut allergy is increasing constantly. Several known peanut proteins (Ara h1, Ara h2, Ara h3, Ara h6, Ara h7, and Ara h9; Ara h8 is a homologous allergen that may account for peanut/birch cross-reactivity) are thought to be responsible for the initial sensitization to peanuts in vulnerable persons, triggering the associated immunoglobulin E (IgE)–mediated response.10-12 Approximately 75% of known peanut-allergic patients will react to these proteins on their first ingestion after being sensitized.9

Since IgE antibodies do not cross the placenta, it is believed that sensitization to peanut proteins must occur in utero or through breast milk. This form of sensitization predisposes these patients to the initial life-threatening anaphylactic reaction.9

There is strong evidence that genetic factors may play a role in peanut allergies.2 In a study of 58 pairs of twins by Sicherer et al,13 heritability of peanut allergy was estimated at 82%, with 64% of monozygotic pairs, versus 7% of dizygotic pairs, showing concordance for peanut allergy. However, the genetic loci that may be responsible for specific food allergies have not yet been identified.2

It is believed that manifestations of food allergy are very similar to those of asthma and atopic dermatitis. According to Green and colleagues,14 82% of peanut-allergic children who visited a referral clinic also had atopic dermatitis. These conditions appear to be triggered by similar mechanisms, mediated by both environmental and genetic factors.2,14-16 Hong et al2 are optimistic about the advances being made in food allergy genetics. Increased understanding, they feel, may lead to new treatment options for potentially fatal food allergies.2

PATIENT PRESENTATION AND HISTORY

As with any IgE-mediated immune response, the patient must have been exposed to the allergen in question. Most patients present with a history of having ingested raw or boiled peanuts and/or foods produced in a facility that also processes nuts.1,18 Clinical symptoms of peanut allergy may develop within seconds of ingestion. For some patients, consumption of as little as 5 to 50 mg of peanut protein can trigger symptoms.19 (A single peanut from a jar of commercially processed peanuts contains approximately 300 mg of potentially allergenic protein.1)

Typically, the most dramatically affected patients have a medical history of asthma or other IgE-mediated immune reactions.1 In one study, young adults with IgE-mediated peanut allergy were found at especially high risk for severe anaphylaxis.6 Seventy-five percent of patients who have a reaction to peanuts do so following their first ingestion (after the initial exposure).

The mean patient age for a diagnosis of peanut allergy is about 14 months; only 20% of the patients diagnosed with a peanut allergy (most likely those with a baseline peanut-specific serum IgE level 18) will outgrow it by the time they reach school age.18,20 Those who do should be encouraged to consume peanuts on a regular basis; according to Byrne et al,21 8% of patients with allergy resolution experience recurrence, a possible result of infrequent peanut consumption.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Patients with peanut allergies can present with a range of symptoms, possibly involving cutaneous, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and/or respiratory systems (see Table 115,22). The more notable symptoms, possibly developing within 15 minutes of exposure, are progressive upper and lower respiratory difficulties, vomiting, diarrhea, hypotension, edema of the face and hands, arrhythmia, throat tightness (in serious cases, approaching anaphylaxis), and possibly loss of consciousness. Such severe reactions often occur in the child who has ingested raw peanuts or tree nuts.22

Milder physical exam findings include erythema, pruritus, conjunctivitis, abdominal pain, nasal congestion, itchy throat, and sneezing. These reactions may have been triggered by foods produced in a facility that also processes nuts, household utensils used to prepare foods that contain nuts, or cross-contamination from another child.9,15,24

DIAGNOSTIC WORK-UP

The diagnosis of a patient with a peanut allergy is made through thorough history taking, careful physical examination, allergy testing with either a skin prick test (SPT) or serum-specific IgE, and oral food challenges. The gold standard for diagnosing food allergy is the double-blind, placebo-controlled oral food challenge,2,25-27 as this test alone can determine the amount of peanut protein needed to trigger a reaction in the given patient.9 However, this is a difficult test to administer and must be performed under strict medical supervision.21

It has been determined that a wheal size of 8.0 mm or greater on the SPT has a 95% to 100% positive predictive value for peanut allergy.1,26,27 Although conflicting results have been reported in some patients between SPT and the oral food challenge, a negative SPT result is considered useful for excluding IgE-mediated allergic responses.22

Researchers examining the peanut-specific serum IgE have demonstrated a 95% to 99% positive predictive value when serum levels exceed 15 kU/L.26,27 This cutoff value in peanut allergy patients is considered suggestive of allergic reactivity, although negative results on an oral food challenge have been reported in more than 25% of children with serum levels exceeding the cutoff.25-27 Testing may have been to whole peanut extract rather than the molecular components (eg, Ara h8).11,12

This past summer, the FDA approved a component test that detects allergen components that include Ara h1, h2, h3, h8, and h9.11,12 Another specific version of the serum IgE test has been in development, one that measures the patient’s IgE reactions to the Ara h2 and Ara h8 components in peanut protein. Johnson and colleagues10,28 have found an increasing level of serum IgE anti–Ara h2 in children who were unable to pass the oral peanut challenge, whereas serum IgE anti–Ara h8 was higher in those who did pass the challenge.28

DIAGNOSING ANAPHYLAXIS

The manifestation of anaphylaxis in patients allergic to peanuts or tree nuts can be life-threatening.29 Symptoms include intense pruritus with flushing of the skin, urticaria, and angioedema, upper-respiratory obstruction resulting from laryngeal edema, and hypotension.30 The clinical criteria for diagnosing anaphylaxis can be found in Table 2.30,31

It is important to recognize the signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis in patients with a peanut allergy; many patients who present to the ED represent first-time reactions. Among patients with life-threatening symptoms on initial reaction, 71% will have similarly severe reactions in subsequent episodes (compared with 44% of patients whose first reaction was not life-threatening).3

TREATMENT, INCLUDING PATIENT EDUCATION

Currently there is no cure for peanut allergy, and no appropriate therapies yet exist to reduce allergy severity. Modest gains have been reported in raising tolerance threshold levels through peanut oral immunotherapy—a long, painstaking process.19,21,32 For now, treatment for peanut allergy is directed at controlling symptoms, once a reaction has occurred. Therefore, the clinician’s goal is to educate peanut-allergic patients and their families on avoiding accidental peanut ingestion, recognizing signs and symptoms of an allergic reaction, and preparing an emergency plan.4

Because four in five patients can expect peanut allergy to last for a lifetime,18,20 strict avoidance of peanuts and peanut products is essential—though difficult because of accidental exposure to food allergens (for example, when dining in restaurants or purchasing bakery products22,32), cross-contamination (as can occur when a food preparation area is not properly cleaned), and allergen cross-reactivity (such as consumption of other legumes).1 Patients must be taught to read food labels carefully for possible hidden sources of peanuts (see Table 37,8); in some cases, product labels bear helpful advisory wording, such as “may contain peanuts.”34,35 US legislation mandates that listed ingredients on food packaging include the eight foods that account for 90% of allergic reactions:

• Peanuts

• Tree nuts

• Egg

• Milk

• Wheat

• Soybeans

• Fish

• Crustacean shellfish.34

Treatment for Anaphylaxis

In pediatric patients, administration of epinephrine is the definitive treatment for anaphylaxis; both the child and parents should carry an epinephrine self-injection device at all times in the event of accidental peanut ingestion. These devices are available in two strengths, based on the child’s weight, and expiration dates should be noted with care. Correct use of the epinephrine self-injection device should be reviewed at each office visit.6

Early-stage allergic reactions can be managed by oral antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine (1 mg/kg body weight up to 75 mg) and an intramuscular injection of epinephrine.1 Prompt transport to the ED should follow (see “Management of Anaphylaxis in the ED”1,9).

PREVENTION

A 2010 expert panel on diagnosis and management of food allergy sponsored by the NIAID, NIH,3 does not advise women to restrict their diet during pregnancy and lactation. Similarly, the United Kingdom’s Department of Health and the Food Standards Agency (DHFSA)36,37 does not support the belief that eating peanuts and peanut-containing foods during pregnancy correlates with a child’s potential for developing a peanut allergy.

The DHFSA does recommend breastfeeding infants for the first six months, if possible, and that mothers refrain from introducing peanut-containing foods during that time. They also recommend that foods associated with a high risk for allergy be introduced into a child’s diet one at a time, to make it easier to identify any allergenic substance.36,37

Lastly, the DHFSA advises parents with a family history of peanut allergy to introduce peanuts only after consulting with their health care provider. The same consideration is advised if a child has already been diagnosed with another allergy.34 According to the American Academy of Pediatrics,6,38 children at high risk for food allergy (eg, atopic disease in both parents or one parent and one sibling) should be breastfed or be given hypoallergenic formula until age 1 year, with no solid foods before age 6 months; peanut-containing foods should not be given before age 3 or 4 years.

CONCLUSION

Peanut allergy can present a lifelong battle for affected patients. Eating one peanut or being exposed even to minute amounts of peanut protein could mean life or death without appropriate management. Reading food labels carefully, preparing peanut-free foods, recognizing the signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis, and obtaining the necessary treatment when allergic reactions occur are essential for peanut-allergic patients and their families.

REFERENCES

1. Burks AW. Peanut allergy. Lancet. 2008;371 (9623):1538-1546.

2. Hong X, Tsai HJ, Wang X. Genetics of food allergy. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21(6):770-776.

3. Boyce JA, Assa’ad A, Burks AW, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(6 suppl):S1-S58.

4. Sicherer S, Muñoz-Furlong A, Godbold JH, Sampson HA. US prevalence of self-reported peanut, tree nut, and sesame allergy: 11-year follow-up. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(6):1322-1326.

5. Hourihane JO, Aiken R, Briggs R, et al. The impact of government advice to pregnant mothers regarding peanut avoidance on the prevalence of peanut allergy in United Kingdom children at school entry. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;312(5):1197-1202.

6. Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Sampson HA. Adverse reactions to foods. Med Clin North Am. 2006;90(1):97-127.

7. Puglisi G, Frieri M. Update on hidden food allergens and food labeling. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2007;28(6):634-639.

8. Hefle SL. Hidden food allergens. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;1(3):269-271.

9. Lee CW, Sheffer AL. Peanut allergy. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2003;24(4):259-264.

10. Boughton B. New test for peanut allergy a step forward. www.medscape.com/viewarticle/740133. Accessed November 16, 2011.

11. Asarnoj A, Movérare R, Östblom E, et al. IgE to peanut allergen components: relation to peanut symptoms and pollen sensitization in 8-year-olds. Allergy. 2010;65(9):1189-1195.

12. Codreanu F, Collignon O, Roitel O, et al. A novel immunoassay using recombinant allergens simplifies peanut allergy diagnosis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2011;154(3):216-226.

13. Sicherer SH, Furlong TJ, Maes HH, et al. Genetics of peanut allergy: a twin study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106(1 pt 1):53-56.

14. Green TD, LaBelle VS, Steele PH, et al. Clinical characteristics of peanut-allergic children: recent changes. Pediatrics. 2007;120(6):1304-1310.

15. Al-ahmed N, Alsowaidi S, Vadas P. Peanut allergy: an overview. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2008;4(4):139-143.

16. Björkstén B. Genetic and environmental risk factors for the development of food allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;5(3):249-253.

17. Lack G. Epidemiologic risks for food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(6):1331-1336.

18. Skolnick HS, Conover-Walker MK, Koerner CB, et al. The natural history of peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107(2):367-374.

19. Clark AT, Islam S, King Y, et al. Successful oral tolerance induction in severe peanut allergy. Allergy. 2009;64(8):1218-1220.

20. Busse PJ, Nowak-Wegrzyn AH, Noone SA, et al. Recurrent peanut allergy. N Engl J Med. 2002; 347(19):1535-1536.

21. Byrne AM, Malka-Rais J, Burks AW, Fleischer DM. How do we know when peanut and tree nut allergy have resolved, and how do we keep it resolved? Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;49(9):1303-1311.

22. Sampson HA. Update on food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(5):805-819.

23. Furlong TJ, Desimone J, Sicherer SH. Peanut and tree nut allergic reactions in restaurants and other establishments. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108(5):866-870.

24. Nelson HS, Lahr J, Rule R, et al. Treatment of anaphylactic sensitivity to peanuts by immunotherapy with injections of aqueous peanut extract. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99(6 pt 1):744-751.

25. Du Toit G, Santos A, Roberts G, et al. The diagnosis of IgE-mediated food allergy in childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2009;20(4):309-319.

26. Roberts G, Lack G. Diagnosing peanut allergy with skin prick and specific IgE testing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(6):1291-1296.

27. Wainstein BK, Yee A, Jelley D, et al. Combining skin prick, immediate skin application and specific-IgE testing in the diagnosis of peanut allergy in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2007;18(3):231-239.

28. Johnson K, Keet C, Hamilton R, Wood R. Predictive value of peanut component specific IgE in a clinical population. Presented at: 2011 Annual Meeting, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; March 19, 2011; San Francisco, CA. Abstract 267.

29. Sheffer AL. Allergen avoidance to reduce asthma-related morbidity. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(11):1134-1136.

30. Russell S, Monroe K, Losek JD. Anaphylaxis management in the pediatric emergency department: opportunities for improvement. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2010;26(2):71-76.

31. Sampson HA, Munoz-Furlong A, Campbell RL, et al. Second symposium on the definition and management of anaphylaxis: summary report—Second National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network symposium. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(2):391-397.

32. Blumchen K, Ulbricht H, Staden U, et al. Oral peanut immunotherapy in children with peanut anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010; 126(1):83-91.

33. Yu JW, Kagan R, Verreault N, et al. Accidental ingestions in children with peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118(2):466-472.

34. Taylor SL, Hefle SL. Food allergen labeling in the USA and Europe. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;6(3):186-190.

35. Sampson HA, Srivastava K, Li XM, Burks AW. New perspectives for the treatment of food allergy (peanut). Arb Paul Ehrlich Inst Bundesamt Sera Impfstoffe Frankf A M. 2003;(94):236-244.

36. McLean S, Sheikh A. Does avoidance of peanuts in early life reduce the risk of peanut allergy? BMJ. 2010 Mar 11;340:c424.

37. Department of Health. Revised government advice on consumption of peanut during pregnancy, breastfeeding, and early life and development of peanut allergy (Aug 2009). www.dh.gov.uk/en/Healthcare/Children/Maternity/Maternalandinfantnutrition/DH_104490. Accessed November 16, 2011.

38. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Nutrition. Hypoallergenic infant formulas. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2):346-349.

Among all persons with food allergies, those who are allergic to peanuts are at greatest risk for anaphylactic symptoms.1 About 30,000 cases of food allergy–related anaphylaxis are seen in the nation’s emergency departments (EDs) each year, and the food most commonly responsible is peanuts.2 What can primary care providers do to reduce the number of peanut allergy–associated anaphylactic reactions and fatalities, both in the ED and in the larger community?

According to a guideline from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID),3 prevalence of peanut allergy is about 0.6% of the US population, although in an 11-year survey involving more than 13,000 respondents, Sicherer et al4 reported allergy to peanuts, tree nuts, or both in 1.4%, possibly translating to some three million Americans; British researchers have reported peanut allergy in 1.8% of an 1,100-member children’s cohort.5 The risk of exposure to peanuts and the associated risk for severe and possibly fatal anaphylaxis present a lifelong struggle for both patient and family.

ETIOLOGY OF PEANUT ALLERGIES

Food allergy prevalence has reportedly doubled in recent decades, with a significant increase also seen in allergy severity.6 Allergies involving eggs, nuts, fish, milk, and other foods represent the leading cause of hospital-treated anaphylaxis throughout the world.1 Unlike other allergenic foods that affect only one age-group, peanuts are among the foods that trigger the “vast majority” of allergic reactions in young children, teenagers, and adults alike.3

Increases in reported episodes of peanut allergy reactions may be occurring for several reasons:

• Many people have adopted vegetarian diets, and nuts are considered a good protein source6

• Environmental exposures are increasingly common

• More people are genetically vulnerable, as the role of family history becomes clearer

• Food preparation methods (eg, shared processing equipment, contaminated raw materials, formulation errors) and inaccurate labeling lead to accidental exposures7,8

• Exposure to nuts in utero or during breastfeeding is more common.9 Nowak-Wegrzyn and Sampson6 point to the promotion of peanut butter as an economical, nutritious food source for children and for women during pregnancy and lactation; mothers’ consumption of peanuts more than once a week during pregnancy and lactation have been linked to overexposure for their children.9

Other trends that may contribute to peanut allergy prevalence are the early introduction of solid foods in the infant diet and the use of skin products that contain peanut oil.6

Environment and Genetics

The body of knowledge regarding the specific causes of peanut allergy is increasing constantly. Several known peanut proteins (Ara h1, Ara h2, Ara h3, Ara h6, Ara h7, and Ara h9; Ara h8 is a homologous allergen that may account for peanut/birch cross-reactivity) are thought to be responsible for the initial sensitization to peanuts in vulnerable persons, triggering the associated immunoglobulin E (IgE)–mediated response.10-12 Approximately 75% of known peanut-allergic patients will react to these proteins on their first ingestion after being sensitized.9

Since IgE antibodies do not cross the placenta, it is believed that sensitization to peanut proteins must occur in utero or through breast milk. This form of sensitization predisposes these patients to the initial life-threatening anaphylactic reaction.9

There is strong evidence that genetic factors may play a role in peanut allergies.2 In a study of 58 pairs of twins by Sicherer et al,13 heritability of peanut allergy was estimated at 82%, with 64% of monozygotic pairs, versus 7% of dizygotic pairs, showing concordance for peanut allergy. However, the genetic loci that may be responsible for specific food allergies have not yet been identified.2

It is believed that manifestations of food allergy are very similar to those of asthma and atopic dermatitis. According to Green and colleagues,14 82% of peanut-allergic children who visited a referral clinic also had atopic dermatitis. These conditions appear to be triggered by similar mechanisms, mediated by both environmental and genetic factors.2,14-16 Hong et al2 are optimistic about the advances being made in food allergy genetics. Increased understanding, they feel, may lead to new treatment options for potentially fatal food allergies.2

PATIENT PRESENTATION AND HISTORY

As with any IgE-mediated immune response, the patient must have been exposed to the allergen in question. Most patients present with a history of having ingested raw or boiled peanuts and/or foods produced in a facility that also processes nuts.1,18 Clinical symptoms of peanut allergy may develop within seconds of ingestion. For some patients, consumption of as little as 5 to 50 mg of peanut protein can trigger symptoms.19 (A single peanut from a jar of commercially processed peanuts contains approximately 300 mg of potentially allergenic protein.1)

Typically, the most dramatically affected patients have a medical history of asthma or other IgE-mediated immune reactions.1 In one study, young adults with IgE-mediated peanut allergy were found at especially high risk for severe anaphylaxis.6 Seventy-five percent of patients who have a reaction to peanuts do so following their first ingestion (after the initial exposure).

The mean patient age for a diagnosis of peanut allergy is about 14 months; only 20% of the patients diagnosed with a peanut allergy (most likely those with a baseline peanut-specific serum IgE level 18) will outgrow it by the time they reach school age.18,20 Those who do should be encouraged to consume peanuts on a regular basis; according to Byrne et al,21 8% of patients with allergy resolution experience recurrence, a possible result of infrequent peanut consumption.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Patients with peanut allergies can present with a range of symptoms, possibly involving cutaneous, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and/or respiratory systems (see Table 115,22). The more notable symptoms, possibly developing within 15 minutes of exposure, are progressive upper and lower respiratory difficulties, vomiting, diarrhea, hypotension, edema of the face and hands, arrhythmia, throat tightness (in serious cases, approaching anaphylaxis), and possibly loss of consciousness. Such severe reactions often occur in the child who has ingested raw peanuts or tree nuts.22

Milder physical exam findings include erythema, pruritus, conjunctivitis, abdominal pain, nasal congestion, itchy throat, and sneezing. These reactions may have been triggered by foods produced in a facility that also processes nuts, household utensils used to prepare foods that contain nuts, or cross-contamination from another child.9,15,24

DIAGNOSTIC WORK-UP

The diagnosis of a patient with a peanut allergy is made through thorough history taking, careful physical examination, allergy testing with either a skin prick test (SPT) or serum-specific IgE, and oral food challenges. The gold standard for diagnosing food allergy is the double-blind, placebo-controlled oral food challenge,2,25-27 as this test alone can determine the amount of peanut protein needed to trigger a reaction in the given patient.9 However, this is a difficult test to administer and must be performed under strict medical supervision.21

It has been determined that a wheal size of 8.0 mm or greater on the SPT has a 95% to 100% positive predictive value for peanut allergy.1,26,27 Although conflicting results have been reported in some patients between SPT and the oral food challenge, a negative SPT result is considered useful for excluding IgE-mediated allergic responses.22