User login

Celiac Disease: A Storm of Gluten Intolerance

Celiac disease (CD), also known as gluten-sensitive enteropathy or celiac sprue, is an endocrine disorder whose effects are triggered by the ingestion of gluten—the principle storage protein in wheat, rye, and barley.1-3 CD inflicts damage to the mucosa of the small intestine and subsequently to systemic organ tissues. CD can affect any organ in the body.1 The responsible genetic factors are the human leukocyte antigens, HLA -DQ2 and -DQ8, which are present in 40% of the general population but are found in nearly 100% of patients with CD.1,3,4

Though previously considered uncommon, CD has been estimated to affect more than 1% of the general population worldwide.1,4,5 Currently, CD is most reliably identified by positive serum antibodies, specifically immunoglobulin A (IgA) anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTG) and IgA antiendomysial (EMA) antibodies,6 and by a finding of villous atrophy of the intestinal lining on biopsy. The spectrum of presentations of CD is broad, including the “typical” intestinal features of diarrhea, bloating, abdominal pain, and weight loss; or common “atypical” extraintestinal manifestations, such as anemia, osteoporosis, infertility, and neurologic disturbances (eg, peripheral neuropathy7).8 See Table 1.8,9

Prevalence of CD is greater among those with a family history of CD; with autoimmune diseases, especially type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and thyroiditis; and with certain genetic disorders (ie, Down, Turner, and Williams syndromes).8-15 Because atypical features dominate in older children and adults, many cases escape diagnosis, and patients may be exposed to serious long-term complications, such as infertility and cancer.1

CD is a lifelong condition, necessitating the complete exclusion of gluten-containing products from the diet. In the US food industry, gluten is used in numerous food applications, complicating the patient education and lifestyle changes needed to implement and maintain a gluten-free diet (GFD). However, if a GFD is not strictly followed, the patient’s quality of life can be seriously impaired.1,4,5

AWARENESS ESSENTIAL IN PRIMARY CARE

For the primary care provider (PCP), there is no shortage of patients with gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, thyroid disease, diabetes, anemia, fatigue, or dysmenorrhea; additionally, PCPs regularly treat patients for a number of associated disorders, including anxiety, irritability, and attention deficit. Yet how likely are PCPs to screen patients with these symptoms for CD? And how many patients with CD never receive a diagnosis of the disorder?

In fact, it has been estimated that more than 90% of persons affected by CD are currently undiagnosed.1,4 In one study involving mass screening of 1,000 children ages 2 to 18, it was determined that almost 90% of celiac-positive children had not previously been diagnosed.5 Similarly, in a cohort of 976 adults (median age, 54.3), the diagnostic rate for CD was initially low at 0.27 cases per thousand visits but increased to 11.6 cases per thousand visits after implementation of active screening.4 Based on these data, it has been estimated that more than 2.7 million Americans unknowingly carry this potentially life-threatening genetic disease.1,4,16

Given the potential patient population with undetected, untreated CD, some researchers consider the disorder one of the most common lifelong diseases in the US.1,8,16 CD is closely associated with T1DM and autoimmune thyroiditis, with cross- prevalence at 11% and 6.7%, respectively.8,12,17 The close association between T1DM and CD led the American Diabetes Association18 to amend guidelines in 2009, suggesting screening for CD in all patients newly diagnosed with T1DM.

PATIENT PRESENTATION: ADULTS VERSUS CHILDREN

Most infants and young children with CD present with the typical or “classic” triad of signs: short stature, failure to thrive, and diarrhea; in individual patients, however, the impact of genetics and exposure to gluten over time can cause considerable variation in patient presentation. As patients with undiagnosed CD age, they may present quite differently or even revert to a latent stage and become asymptomatic.19,20

In two separate reviews, it was noted that classic symptoms of CD are not evident in a majority of older children and adults; instead, anemia and fatigue were the predominating symptoms.12,20An important note: The patient with no symptoms or atypical signs of CD may still be experiencing significant damage, inflicted by gluten-induced antibodies, to the intestinal lining and/or mucosal linings in other organ systems—perhaps for years before the disease becomes evident.20

Clinical Findings Differ With Age, Gender

Historically, CD was considered a pediatric syndrome; however, a diagnosis of CD has become increasingly common among older children and adults, especially elderly patients, although symptoms in the latter group are subtle.21-23 Recent, active CD is being diagnosed among men older than 55 more commonly than in women of this age-group; women are generally younger at diagnosis but have experienced symptoms longer.22,23 This later onset in men suggests that antibody seropositivity and the associated active disease may be triggered later in life.8,22

A variety of findings have been reported in the history and physical exam of most patients who present with CD.The most prevalent signs and symptoms are abdominal pain, frequent loose stools, weight loss, joint pain, and weakness.8,11,16 Unlike the pediatric patient with the classic triad of symptoms, adults usually experience more generalized GI manifestations, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), abdominal pain, or acid reflux.10

Many patients have no GI symptoms but may present solely with fatigue, arthralgias, or myalgia.20 In fact, more than 50% of adults with CD present with atypical or extraintestinal disorders, such as anemia, infertility, osteoporosis, neurologic problems, or other autoimmune disorders.8,16,23,24 It is important for clinicians to note that atypical is somewhat typical in the older patient who presents with CD.

Patients with asymptomatic or silent CD, (see “Classification and Pathology,” below) lack both classic and atypical symptoms but still have villous atrophy, usually discovered during endoscopy being conducted for other reasons.8 Because of its predominantly atypical presentations, CD is considered a multisystem endocrine condition rather than one that is mainly gastrointestinal.8,16,25,26

CLASSIFICATION AND PATHOLOGY

Though frequently a silent disorder, CD typically progresses through four stages: classical, atypical, latent, and silent. Clinicians should strive to become fully aware of each stage and its implications.8,26,27

The classical form is primarily diagnosed in children ages 6 to 18 months. It is characterized by villous atrophy and typical symptoms of intestinal malabsorption.8

The patient with atypical CD has minor intestinal symptoms, but architectural abnormalities can be found in the mucosa of the small intestine. This patient is likely to present with various extraintestinal disorders, including osteoporosis, anemia, infertility, and neuropathies.7,8

In the latent form of CD, the HLA-DQ2 and/or -DQ8 genetic markers are present. Serology for CD may be positive, but the intestinal mucosa may be normal. The patient may or may not be experiencing extraintestinal symptoms. In patients with latent CD, the gluten-associated changes appear later in life.8 The precise trigger for late activation of the disease, though apparently linked to genetics and gluten exposure, remains elusive.20,24

The silent form of CD is marked by mucosal abnormalities in the small intestine and usually by positive CD serology, but it is asymptomatic. The iceberg theory of celiac disease28 (see figure28) has been proposed to explain CD’s hidden manifestations over time.

In patients with atypical, latent, or silent CD, the condition is sometimes detected incidentally during screening of at-risk groups or by endoscopy performed for other reasons.8 Most of these patients respond well to GFD therapy, noting both physical and psychological improvement—suggesting that these patients, even though asymptomatic and seemingly healthy, may have been experiencing minor manifestations of undiagnosed CD for many years: decreased appetite, fatigue, and even behavioral abnormalities.1,8

Histopathologic analysis of abnormalities found on biopsy of the small intestine relies on the four-stage Marsh classification29:

• Marsh 0: normal mucosa

• Marsh I: intraepithelial lymphocytosis

• Marsh II: intraepithelial lymphocytosis with crypt hyperplasia

• Marsh III: intraepithelial lymphocytosis with crypt hyperplasia and villous atrophy.8,29 Modifications to this classification have been made by Oberhuber30,31 to denote the degree of villous flattening32 (ie, IIIa, IIIb, IIIc).

Villous atrophy of the mucosa has long been considered the hallmark of CD, and its detection, according to the American Gastroenterological Association,2,26 remains the gold standard in confirming a diagnosis of CD.4,16,26 However, early screening (ie, serologic testing for tTG and EMA) is the necessary initial step in ensuring diagnostic accuracy, as other conditions can cause villous atrophy, and latent CD can coexist with normal intestinal mucosa.10

Avoiding Diagnostic Delays

Because of the broad spectrum of unrelated GI signs in all ages and the subtle presentation in adults, diagnosis of CD in this patient population is frequently delayed for estimated periods ranging from five to 11 years.4,11,23,33

Improving clinician awareness of the manifestations of CD is essential34; too frequently, the common symptoms of probable CD are treated as individual idiopathic disorders by both PCPs and secondary specialists, who prescribe proton pump inhibitors, antihistamines, cathartics, and/or antimotility drugs for years without ruling out a common, easily identified genetic disease. Even though the prevalence of CD has recently been shown to have increased more than fourfold since 1950,35 serologic testing for CD is not widely implemented by PCPs.4,11,20

Specialists, too, may be slow to recognize this treatable autoimmune disorder. In a recent nationwide study, it was found that gastroenterologists performed a small-bowel biopsy in less than 10% of their patients who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) for likely symptoms of CD.36 Relying solely on clinical expertise and visual recognition of intestinal abnormalities can delay diagnosis for years.4,36 Many patients may never be given a correct diagnosis of CD.

The Role of Serologic Testing

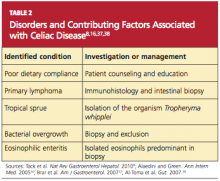

Current data demonstrate that autoimmune diseases are on the rise,8,16,36 and CD can be the primary cause or a contributing factor in several other disorders (see Table 28,16,37,38). Gastroenterologists may be correct in stating that biopsy is the only way to make a diagnosis of CD or to stage CD-associated intestinal damage4,26; yet by implementing a protocol of serologic testing for tTG and EMA in at-risk patients, PCPs could prevent a missed diagnosis on EGD when biopsy has not been considered, as in the case of atypical CD; or when biopsy results are negative in a patient with latent CD.39,40

Because of its high negative predictive value, serologic testing should be conducted first to significantly reduce the probability of suspected CD. Such selective screening should be performed by the PCP before invasive testing by the gastroenterologist and before long-term empiric treatment for idiopathic GERD, IBS, or other unexplained disorders.32,40

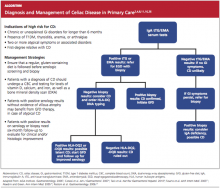

Thus, it has been recommended that PCPs perform screening for CD in patients with unexplained chronic GI disturbances or a familial prevalence of CD, or in those who present with the atypical signs of CD or with associated disorders.1,10,16,20 Whether serologic screening results are positive or negative for CD, the patient with classic GI symptoms should undergo endoscopy with biopsy to confirm active disease and to evaluate the extent of intestinal damage—or to explore other causes.26,39 An algorithm2,4,8,11,16,26 illustrating suggested screening, treatment, and follow-up strategies for patients at high risk for CD is shown below.

Catassi and Fasano34 recently proposed a “four out of five” rule, by which diagnosis of CD may be confirmed in patients with at least four of the following five criteria:

• Typical symptoms of CD

• Positive serology (ie, IgA tTG and IgA EMA antibodies)

• Genetic susceptibility (as confirmed by the presence of HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8)

• Small intestine biopsy results indicating celiac enteropathy

• Improvement of CD signs and symptoms following implementation of the GFD.34

CURRENT TREATMENT AND ASSOCIATED CHALLENGES

Because gluten consumption is the principal trigger of CD pathology, a GFD is considered the safest, most effective therapy for the disorder.1,8,10,11,16,19 Implementing and maintaining the GFD involves a considerable learning curve for the patient, the patient’s family, and possibly the provider; to achieve complete recovery, all involved must become knowledgeable regarding gluten-free and gluten-containing products. The patient must be willing and able to avoid those that contain gluten and bear the potentially high costs8 of gluten-free foods.

Even for patients with CD who are determined to comply with the GFD, gluten monitoring can be difficult. There are ways to determine what is a safe level of gluten ingestion for each patient, but trace amounts of gluten are found in many products, including some that are marked “gluten-free.”1,41 The FDA has proposed that a product labeled gluten-free may contain no more than 20 parts per million (ppm, ie, 20 mg/kg) of gluten.42 In other countries, however, acceptable levels may be as high as 200 ppm (200 mg/kg)—which are considered well above the trigger amounts in the average patient with CD.1,41 The complex nature of each patient’s sensitivity to gluten and the ubiquitous presence of gluten as a food source in both industrialized and developing countries make adherence to the GFD challenging.10

It is critical for the PCP to help the patient review all of his or her prescription and OTC pharmaceuticals and nutritional supplements, as these may contain hidden gluten in the form of modified starches and other fillers.41 It may be also advisable to involve the patient’s pharmacist, requesting an assessment for agents that may be suspect.

A management team approach may ensure the most integrative care. In addition to the PCP and the pharmacist, such a team might include a gastroenterologist, an endocrinologist, a nutritionist, and a psychologist, who may be needed to help the patient confront the great life adjustment required, in addition to addressing other behavioral disorders that are common in patients with CD.10,26

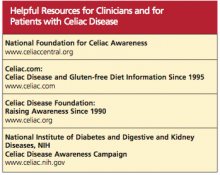

See the box for resources that may be beneficial for both patients and their clinicians.

Alternative Medicine Options

Alternative medicine is gaining favor, especially when no drug therapy is currently available to alleviate gluten toxicity. Supplementation with the fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K), vitamin B12, folic acid, and the minerals calcium and iron, as indicated by serum deficiencies, is recommended.10,20 Supplementation with digestive enzymes, which are known to be deficient in patients with CD as a result of villous atrophy, may help break down undigested gluten proteins; research is under way to find a recombinant enzyme therapy.10 Researchers have recently shown that probiotics (specifically, Bifidobacterium lactis) significantly reduce the immune response when incidental exposure to gluten occurs.43

REFRACTORY CELIAC DISEASE

Patients with late-onset CD, especially those not diagnosed until after age 50, may have a diminished or absent response to dietary therapy. In some patients, histologic signs and clinical symptoms persist or relapse after a prior positive response to a strict GFD, despite continued adherence to the diet for longer than 12 months.44 Once other causes have been carefully excluded, these patients are considered to have refractory celiac disease (RCD). Exact prevalence of RCD is unknown, but Tack et al8 estimate it at 5% of all cases of CD. Relapsing CD resulting from poor adherence to the GFD is not considered true RCD.8,16,37,38

According to researchers for the European Celiac Disease working group,8,45 RCD can be divided into types I and II:

• RCD I, in which normal polyclonal T cells are present in the intestinal lumen

• RCD II, in which abnormal clonal T cells infiltrate the intestinal mucosa, representing premalignancy.45

The histologic picture of RCD mimics that of severe CD. Malabsorption complications, lesions in the intestinal mucosa, and inflammatory lymphocytosis are present.44 Some patients, like those with classical CD, have serology test results that are consistent with CD and an initial response to GFD therapy; after months or years, however, this response subsides. Other patients are immediately unresponsive to GFD and lack the serologic markers for CD.8

A differential diagnosis including other explanations for the manifestations of RCD must be carefully reviewed, with each excluded, through the strategies shown in Table 2. This review is essential, as patients with RCD II have a much worse prognosis than those with RCD I; the associated five-year survival rates are 44% to 58%, versus 85% or greater, respectively.36,46

Additionally, the continued autoimmune expansion of aberrant T cells in patients with RCD II causes early conversion to malignancy, usually within four to six years after diagnosis. Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma is the most common malignancy, occurring in more than 50% of patients with RCD II, and a likely cause of death.3,8,46,47

Treatment for Refractory Celiac Disease

In addition to the GFD, patients with RCD I generally respond well to corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive treatment.8 Use of budesonide, a corticosteroid given in a once-daily, 9-mg dose, has led to almost complete recovery in most patients. Duration of therapy is response-dependent.37

Systemic corticosteroids or other immunosuppressant agents, such as azathioprine, should be reserved for patients with RCD I or RCD II who do not respond to budesonide, as lengthy treatment regimens are required, with considerable risk for adverse effects.35,48

Recently, promising results have been reported in a small, open-label cohort study involving patients with RCD II who underwent five days of treatment with IV cladribine (0.1 mg/kg/d).49

PREVENTION OF CD

A good nutritional start from birth could be the best means of preventing symptomatic CD. According to findings from a meta-analysis of data from four studies, children being breastfed at the time gluten was introduced had a 52% reduction in risk for CD, compared with their peers who were not being breastfed at that time.50

The protection breast milk appears to provide against CD is not clearly understood. One possible mechanism is that breast milk may protect an infant against CD by preventing gastrointestinal infections, as is the case with other infections. The presence of GI infections (eg, rotavirus) in early life could lead to increased permeability of the intestinal mucosa, allowing the passage of gluten into the lamina propria.3,8,50

Extended duration of breastfeeding is also associated with a reduced risk for CD.8,41,50 Long-term studies are needed, however, to determine whether breastfeeding delays CD onset or provides permanent protection against the disorder.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

A recently marketed OTC testing kit for CD is now available in Canada and other countries outside the US; this may be an indication of the growing awareness of the numbers of patients with undiagnosed CD. The test parallels the tTG serum test, which in the US is evaluated only in laboratories; it has comparable specificity and sensitivity, with results within 10 minutes. In the US, the FDA has not yet approved the kit, but domestic testing of the product may soon be under way.51

Alternative treatment modalities are currently focusing on the detoxification of wheat components, rapid enzymatic degradation to reduce exposure to gluten, inducing gluten tolerance, inhibiting permeability of the small intestine to gluten (which, it is thought, may prevent many of the systemic manifestations of CD), and finally, development of an immunomodulatory vaccine.8,33 None of these therapies is yet approved.

IMPLICATIONS OF DELAYED DIAGNOSIS

The unrecognized prevalence of CD is a growing issue, as many symptomatic but unscreened patients are frequently misdiagnosed with IBS, chronic fatigue, or other idiopathic disorders. The silent and latent forms of CD are of the greatest concern, as they show minimal signs and can lead to multiple organ system damage and are implicated in other autoimmune disorders. The longer diagnosis is delayed, the greater is patients’ resistance to dietary therapy, and the less likely that established intestinal and/or neurologic damage can be reversed.10,20,51

The large proportion of undiagnosed celiac patients may account for an accompanying underestimated cost to both the patient and the health care system because of repeated referrals to investigate unexplained disorders before an accurate diagnosis is made. In one recent analysis, mass screening for CD in a young adult population led to improved quality-of-life years by shortening the time to diagnosis and treatment; it was also found cost-effective.52 PCPs must be attentive to patients who may be at high risk for CD and implement combined serum tTG and EMA screening as the initial step in identification and treatment.4,10,11,20 Some form of standardized screening protocol may become inevitable.

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of CD has increased more than fourfold since 1950, and diagnosis is often significantly delayed. Increased awareness is needed among PCPs that CD in adults is likely to manifest with atypical (ie, nongastrointestinal) symptoms and signs. Judicious use of serologic screening for CD would lead to earlier diagnosis and more effective treatment, possibly preventing the potentially lethal refractory disease forms associated with chronic untreated CD.

REFERENCES

1. Ramos M, Orozovich P, Moser K, et al. Health 1. Catassi C, Fasano A. Celiac disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24(6):687-691.

2. AGA Institute. AGA Institute medical position statement on the diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(6):1977-1980.

3. Green PH, Jabri B. Coeliac disease. Lancet. 2003;362(9381):383-391.

4. Catassi C, Kryszak D, Louis-Jacques O, et al. Detection of celiac disease in primary care: a multicenter case-finding study in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(7);1454-1460.

5. Demirçeken FG, Kansu A, Kuloglu Z, et al. Human tissue transglutaminase antibody screening by immunochromatographic line immunoassay for early diagnosis of celiac disease in Turkish children. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2008;19(1):14-21.

6. van der Windt DA, Jellema P, Mulder CJ, et al. Diagnostic testing for celiac disease among patients with abdominal symptoms: a systematic review. JAMA. 2010;303(17):1738-1746.

7. Freeman HJ. Neurological disorders in adult celiac disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008; 22(11):909-911.

8. Tack GJ, Verbeek WHM, Schreurs MWJ, Mulder CJJ. The spectrum of celiac disease: epidemiology, clinical aspects and treatment. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7(4):204-213.

9. Farrell RJ, Kelly CP. Celiac sprue. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(3):180-188.

10. Green PHR, Cellier C. Celiac disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(17):1731-1743.

11. Fasano A, Berti I, Gerarduzzi T, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease in at-risk and not-at-risk groups in the United States: a large multicenter study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(3):286-292.

12. Sud S, Marcon M, Assor E, et al. Celiac disease and pediatric type 1 diabetes: diagnostic and treatment dilemmas. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol. 2010;2010:161285. Epub 2010 Jun 23.

13. Swigonski NL, Kuhlenschmidt HL, Bull MJ, et al. Screening for celiac disease in asymptomatic children with Down syndrome: cost-effectiveness of preventing lymphoma. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):594-602.

14. Bonamico M, Pasquino AM, Mariani P, et al; Italian Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology (SIGEP); Italian Study Group for Turner Syndrome (ISGTS). Prevalence and clinical picture of celiac disease in Turner syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(12): 5495-5498.

15. Giannotti A, Tiberio G, Castro M, et al. Coeliac disease in Williams syndrome. J Med Genet. 2001;38(11):767–768.

16. Alaedini A, Green P. Narrative review: celiac disease: understanding a complex autoimmune disorder. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(4): 289-298.

17. Fröhlich-Reiterer EE, Hofer S, Kaspers S, et al. Screening frequency for celiac disease and autoimmune thyroiditis in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus: data from a German/Austrian multicentre survey. Pediatr Diabetes. 2008;9(6):546-553.

18. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2009. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(1):S13–S61.

19. Losowsky MS. A history of coeliac disease. Dig Dis. 2008;26(2):112-120.

20. Evans KE, Hadjivassilou M, Sanders DS. Understanding ‘silent’ coeliac disease: complications in diagnosis and treatment. Gastrointest Nurs. 2010;8(2):26-32.

21. Lurie Y, Landau DA, Pfeffer J, Oren R. Celiac disease diagnosed in the elderly. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42(1):59-61.

22. Vilppula A, Kaukinen K, Luostarinen L, et al. Increasing prevalence and high incidence of celiac disease in elderly people: a population-based study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009 Jun 29;9:49.

23. Lo W, Sano K, Lebwohl B, et al. Changing presentation of adult celiac disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48(2):395-398.

24. Alaedini A, Okamoto H, Briani C, et al. Immune cross-reactivity in celiac disease: anti-gliadin antibodies bind to neuronal synapsin I. J Immunol. 2007;178(10):6590-6595.

25. Tursi A, Giorgetti G, Brandimarte G, et al. Prevalence and clinical presentation of subclinical/silent celiac disease in adults: an analysis on a 12-year observation. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48(38):462-464.

26. Rostom A, Murray JA, Kagnoff MF. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute technical review on the diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(6):1981-2002.

27. Ferguson A, Arranz E, O’Mahony S. Clinical and pathological spectrum of coeliac disease—active, silent, latent, potential. Gut. 1993;34(2): 150-151.

28. Logan RFA. Problems and pitfalls in epidemiological studies of coeliac disease. In: Auricchio S, Visakorpi JK, eds. Common Food Intolerances 1. Epidemiology of Coeliac Disease (Dynamic Nutrition Research)(Pt 1). Basel, Switzerland: Karger; 1992:14-22.

29. Marsh MN. Gluten, major histocompatibility complex, and the small intestine: a molecular and immunobiologic approach to the spectrum of gluten sensitivity (‘celiac sprue’). Gastroenterology. 1992;102(1):330-354.

30. Oberhuber G, Granditsch G, Vogelsang H. The histopathology of coeliac disease: time for a standardized report scheme for pathologists. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11(10):1185-1194.

31. Corazza GR, Villanaci V. Coeliac disease.

J Clin Pathol. 2005;58(6):573-574.

32. Hadithi M, von Blomberg BM, Crusius JB, et al. Accuracy of serologic tests and HLA-DQ typing for diagnosing celiac disease. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(5):294-302.

33. Lerner A. New therapeutic strategies for celiac disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9(3):144-147.

34. Catassi C, Fasano A. Celiac disease diagnosis: simple rules are better than complicated algorithms. Am J Med. 2010;123(8):691-693.

35. Rubio-Tapia A, Kyle RA, Kaplan EL, et al. Increased prevalence and mortality in undiagnosed celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2009; 137(1):88–93.

36. Harewood GC, Holub JL, Lieberman DA. Variation in small bowel biopsy performance among diverse endoscopy settings: results from a national endoscopic database. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(9):1790-1794.

37. Brar P, Lee S, Lewis S, et al. Budesonide in the treatment of refractory celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(10):2265-2269.

38. Al-Toma A, Verbeek WHM, Hadithi M, et al. Survival in refractory coeliac disease and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma: retrospective evaluation of single-centre experience. Gut. 2007;56(10):1373-1378.

39. Kaukinen K, Mäki M, Partanen J, et al. Celiac disease without villous atrophy: revision of criteria called for. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46(4):879-887.

40. Mohamed BM, Feighery C, Coates C, et al. The absence of a mucosal lesion on standard histological examination does not exclude diagnosis of celiac disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2008; 53(1):52-61.

41. Fasano A, Catassi C. Current approaches to diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease: an evolving spectrum. Gastroenterology. 2001; 120(3):636-651.

42. US Food and Drug Administration. Topic-specific labeling information (2010). www.fda.gov/Food/LabelingNutrition/FoodLabeling GuidanceRegulatoryInformation/Topic-Specific LabelingInformation/default.htm. Accessed March 28, 2011.

43. Lindfors K, Blomqvist T, Juuti-Uusitalo K, et al. Live probiotic Bifidobacterium lactis bacteria inhibit the toxic effects induced by wheat gliadin in epithelial cell culture. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;152(3):552-558.

44. Cellier C, Delabesse E, Helmer C, et al; French Coeliac Disease Study Group. Refractory sprue, coeliac disease, and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. Lancet. 2000;356(9225): 203-208.

45. United European Gastroenterology. When is a coeliac a coeliac? Report of a working group of the United European Gastroenterology Week in Amsterdam, 2001. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13(9):1123-1128.

46. Malamut G, Afchain P, Verkarre V, et al. Presentation and long-term follow-up of refractory celiac disease: comparison of type I with type II. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(1):81-90.

47. Al-Toma A, Goerres MS, Meijer JW, et al. Human leukocyte antigen-DQ2 homozygosity and the development of refractory celiac disease and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(3): 315-319.

48. Mauriño E, Niveloni S, Cherñavsky A, et al. Azathioprine in refractory sprue: results from a prospective, open-label study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(10):2595–2602.

49. Tack GJ, Verbeek WHM, Al-Toma A, et al. Evaluation of cladribine treatment in refractory celiac disease type II. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(4):506–513.

50. Akobeng AK, Ramanan AV, Buchan I, Heller RF. Effect of breast feeding on risk of coeliac disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Arch Dis Child. 2006; 91(1):39-43.

51. Rashid M, Butzner JD, Warren R, et al. Home blood testing for celiac disease: recommendations for management. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55(2):151-153.

52. Hershcovici T, Leshno M, Goldin E, et al. Cost effectiveness of mass screening for coeliac disease is determined by time-delay to diagnosis and quality of life on a gluten-free diet. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(8):901-910.

Celiac disease (CD), also known as gluten-sensitive enteropathy or celiac sprue, is an endocrine disorder whose effects are triggered by the ingestion of gluten—the principle storage protein in wheat, rye, and barley.1-3 CD inflicts damage to the mucosa of the small intestine and subsequently to systemic organ tissues. CD can affect any organ in the body.1 The responsible genetic factors are the human leukocyte antigens, HLA -DQ2 and -DQ8, which are present in 40% of the general population but are found in nearly 100% of patients with CD.1,3,4

Though previously considered uncommon, CD has been estimated to affect more than 1% of the general population worldwide.1,4,5 Currently, CD is most reliably identified by positive serum antibodies, specifically immunoglobulin A (IgA) anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTG) and IgA antiendomysial (EMA) antibodies,6 and by a finding of villous atrophy of the intestinal lining on biopsy. The spectrum of presentations of CD is broad, including the “typical” intestinal features of diarrhea, bloating, abdominal pain, and weight loss; or common “atypical” extraintestinal manifestations, such as anemia, osteoporosis, infertility, and neurologic disturbances (eg, peripheral neuropathy7).8 See Table 1.8,9

Prevalence of CD is greater among those with a family history of CD; with autoimmune diseases, especially type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and thyroiditis; and with certain genetic disorders (ie, Down, Turner, and Williams syndromes).8-15 Because atypical features dominate in older children and adults, many cases escape diagnosis, and patients may be exposed to serious long-term complications, such as infertility and cancer.1

CD is a lifelong condition, necessitating the complete exclusion of gluten-containing products from the diet. In the US food industry, gluten is used in numerous food applications, complicating the patient education and lifestyle changes needed to implement and maintain a gluten-free diet (GFD). However, if a GFD is not strictly followed, the patient’s quality of life can be seriously impaired.1,4,5

AWARENESS ESSENTIAL IN PRIMARY CARE

For the primary care provider (PCP), there is no shortage of patients with gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, thyroid disease, diabetes, anemia, fatigue, or dysmenorrhea; additionally, PCPs regularly treat patients for a number of associated disorders, including anxiety, irritability, and attention deficit. Yet how likely are PCPs to screen patients with these symptoms for CD? And how many patients with CD never receive a diagnosis of the disorder?

In fact, it has been estimated that more than 90% of persons affected by CD are currently undiagnosed.1,4 In one study involving mass screening of 1,000 children ages 2 to 18, it was determined that almost 90% of celiac-positive children had not previously been diagnosed.5 Similarly, in a cohort of 976 adults (median age, 54.3), the diagnostic rate for CD was initially low at 0.27 cases per thousand visits but increased to 11.6 cases per thousand visits after implementation of active screening.4 Based on these data, it has been estimated that more than 2.7 million Americans unknowingly carry this potentially life-threatening genetic disease.1,4,16

Given the potential patient population with undetected, untreated CD, some researchers consider the disorder one of the most common lifelong diseases in the US.1,8,16 CD is closely associated with T1DM and autoimmune thyroiditis, with cross- prevalence at 11% and 6.7%, respectively.8,12,17 The close association between T1DM and CD led the American Diabetes Association18 to amend guidelines in 2009, suggesting screening for CD in all patients newly diagnosed with T1DM.

PATIENT PRESENTATION: ADULTS VERSUS CHILDREN

Most infants and young children with CD present with the typical or “classic” triad of signs: short stature, failure to thrive, and diarrhea; in individual patients, however, the impact of genetics and exposure to gluten over time can cause considerable variation in patient presentation. As patients with undiagnosed CD age, they may present quite differently or even revert to a latent stage and become asymptomatic.19,20

In two separate reviews, it was noted that classic symptoms of CD are not evident in a majority of older children and adults; instead, anemia and fatigue were the predominating symptoms.12,20An important note: The patient with no symptoms or atypical signs of CD may still be experiencing significant damage, inflicted by gluten-induced antibodies, to the intestinal lining and/or mucosal linings in other organ systems—perhaps for years before the disease becomes evident.20

Clinical Findings Differ With Age, Gender

Historically, CD was considered a pediatric syndrome; however, a diagnosis of CD has become increasingly common among older children and adults, especially elderly patients, although symptoms in the latter group are subtle.21-23 Recent, active CD is being diagnosed among men older than 55 more commonly than in women of this age-group; women are generally younger at diagnosis but have experienced symptoms longer.22,23 This later onset in men suggests that antibody seropositivity and the associated active disease may be triggered later in life.8,22

A variety of findings have been reported in the history and physical exam of most patients who present with CD.The most prevalent signs and symptoms are abdominal pain, frequent loose stools, weight loss, joint pain, and weakness.8,11,16 Unlike the pediatric patient with the classic triad of symptoms, adults usually experience more generalized GI manifestations, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), abdominal pain, or acid reflux.10

Many patients have no GI symptoms but may present solely with fatigue, arthralgias, or myalgia.20 In fact, more than 50% of adults with CD present with atypical or extraintestinal disorders, such as anemia, infertility, osteoporosis, neurologic problems, or other autoimmune disorders.8,16,23,24 It is important for clinicians to note that atypical is somewhat typical in the older patient who presents with CD.

Patients with asymptomatic or silent CD, (see “Classification and Pathology,” below) lack both classic and atypical symptoms but still have villous atrophy, usually discovered during endoscopy being conducted for other reasons.8 Because of its predominantly atypical presentations, CD is considered a multisystem endocrine condition rather than one that is mainly gastrointestinal.8,16,25,26

CLASSIFICATION AND PATHOLOGY

Though frequently a silent disorder, CD typically progresses through four stages: classical, atypical, latent, and silent. Clinicians should strive to become fully aware of each stage and its implications.8,26,27

The classical form is primarily diagnosed in children ages 6 to 18 months. It is characterized by villous atrophy and typical symptoms of intestinal malabsorption.8

The patient with atypical CD has minor intestinal symptoms, but architectural abnormalities can be found in the mucosa of the small intestine. This patient is likely to present with various extraintestinal disorders, including osteoporosis, anemia, infertility, and neuropathies.7,8

In the latent form of CD, the HLA-DQ2 and/or -DQ8 genetic markers are present. Serology for CD may be positive, but the intestinal mucosa may be normal. The patient may or may not be experiencing extraintestinal symptoms. In patients with latent CD, the gluten-associated changes appear later in life.8 The precise trigger for late activation of the disease, though apparently linked to genetics and gluten exposure, remains elusive.20,24

The silent form of CD is marked by mucosal abnormalities in the small intestine and usually by positive CD serology, but it is asymptomatic. The iceberg theory of celiac disease28 (see figure28) has been proposed to explain CD’s hidden manifestations over time.

In patients with atypical, latent, or silent CD, the condition is sometimes detected incidentally during screening of at-risk groups or by endoscopy performed for other reasons.8 Most of these patients respond well to GFD therapy, noting both physical and psychological improvement—suggesting that these patients, even though asymptomatic and seemingly healthy, may have been experiencing minor manifestations of undiagnosed CD for many years: decreased appetite, fatigue, and even behavioral abnormalities.1,8

Histopathologic analysis of abnormalities found on biopsy of the small intestine relies on the four-stage Marsh classification29:

• Marsh 0: normal mucosa

• Marsh I: intraepithelial lymphocytosis

• Marsh II: intraepithelial lymphocytosis with crypt hyperplasia

• Marsh III: intraepithelial lymphocytosis with crypt hyperplasia and villous atrophy.8,29 Modifications to this classification have been made by Oberhuber30,31 to denote the degree of villous flattening32 (ie, IIIa, IIIb, IIIc).

Villous atrophy of the mucosa has long been considered the hallmark of CD, and its detection, according to the American Gastroenterological Association,2,26 remains the gold standard in confirming a diagnosis of CD.4,16,26 However, early screening (ie, serologic testing for tTG and EMA) is the necessary initial step in ensuring diagnostic accuracy, as other conditions can cause villous atrophy, and latent CD can coexist with normal intestinal mucosa.10

Avoiding Diagnostic Delays

Because of the broad spectrum of unrelated GI signs in all ages and the subtle presentation in adults, diagnosis of CD in this patient population is frequently delayed for estimated periods ranging from five to 11 years.4,11,23,33

Improving clinician awareness of the manifestations of CD is essential34; too frequently, the common symptoms of probable CD are treated as individual idiopathic disorders by both PCPs and secondary specialists, who prescribe proton pump inhibitors, antihistamines, cathartics, and/or antimotility drugs for years without ruling out a common, easily identified genetic disease. Even though the prevalence of CD has recently been shown to have increased more than fourfold since 1950,35 serologic testing for CD is not widely implemented by PCPs.4,11,20

Specialists, too, may be slow to recognize this treatable autoimmune disorder. In a recent nationwide study, it was found that gastroenterologists performed a small-bowel biopsy in less than 10% of their patients who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) for likely symptoms of CD.36 Relying solely on clinical expertise and visual recognition of intestinal abnormalities can delay diagnosis for years.4,36 Many patients may never be given a correct diagnosis of CD.

The Role of Serologic Testing

Current data demonstrate that autoimmune diseases are on the rise,8,16,36 and CD can be the primary cause or a contributing factor in several other disorders (see Table 28,16,37,38). Gastroenterologists may be correct in stating that biopsy is the only way to make a diagnosis of CD or to stage CD-associated intestinal damage4,26; yet by implementing a protocol of serologic testing for tTG and EMA in at-risk patients, PCPs could prevent a missed diagnosis on EGD when biopsy has not been considered, as in the case of atypical CD; or when biopsy results are negative in a patient with latent CD.39,40

Because of its high negative predictive value, serologic testing should be conducted first to significantly reduce the probability of suspected CD. Such selective screening should be performed by the PCP before invasive testing by the gastroenterologist and before long-term empiric treatment for idiopathic GERD, IBS, or other unexplained disorders.32,40

Thus, it has been recommended that PCPs perform screening for CD in patients with unexplained chronic GI disturbances or a familial prevalence of CD, or in those who present with the atypical signs of CD or with associated disorders.1,10,16,20 Whether serologic screening results are positive or negative for CD, the patient with classic GI symptoms should undergo endoscopy with biopsy to confirm active disease and to evaluate the extent of intestinal damage—or to explore other causes.26,39 An algorithm2,4,8,11,16,26 illustrating suggested screening, treatment, and follow-up strategies for patients at high risk for CD is shown below.

Catassi and Fasano34 recently proposed a “four out of five” rule, by which diagnosis of CD may be confirmed in patients with at least four of the following five criteria:

• Typical symptoms of CD

• Positive serology (ie, IgA tTG and IgA EMA antibodies)

• Genetic susceptibility (as confirmed by the presence of HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8)

• Small intestine biopsy results indicating celiac enteropathy

• Improvement of CD signs and symptoms following implementation of the GFD.34

CURRENT TREATMENT AND ASSOCIATED CHALLENGES

Because gluten consumption is the principal trigger of CD pathology, a GFD is considered the safest, most effective therapy for the disorder.1,8,10,11,16,19 Implementing and maintaining the GFD involves a considerable learning curve for the patient, the patient’s family, and possibly the provider; to achieve complete recovery, all involved must become knowledgeable regarding gluten-free and gluten-containing products. The patient must be willing and able to avoid those that contain gluten and bear the potentially high costs8 of gluten-free foods.

Even for patients with CD who are determined to comply with the GFD, gluten monitoring can be difficult. There are ways to determine what is a safe level of gluten ingestion for each patient, but trace amounts of gluten are found in many products, including some that are marked “gluten-free.”1,41 The FDA has proposed that a product labeled gluten-free may contain no more than 20 parts per million (ppm, ie, 20 mg/kg) of gluten.42 In other countries, however, acceptable levels may be as high as 200 ppm (200 mg/kg)—which are considered well above the trigger amounts in the average patient with CD.1,41 The complex nature of each patient’s sensitivity to gluten and the ubiquitous presence of gluten as a food source in both industrialized and developing countries make adherence to the GFD challenging.10

It is critical for the PCP to help the patient review all of his or her prescription and OTC pharmaceuticals and nutritional supplements, as these may contain hidden gluten in the form of modified starches and other fillers.41 It may be also advisable to involve the patient’s pharmacist, requesting an assessment for agents that may be suspect.

A management team approach may ensure the most integrative care. In addition to the PCP and the pharmacist, such a team might include a gastroenterologist, an endocrinologist, a nutritionist, and a psychologist, who may be needed to help the patient confront the great life adjustment required, in addition to addressing other behavioral disorders that are common in patients with CD.10,26

See the box for resources that may be beneficial for both patients and their clinicians.

Alternative Medicine Options

Alternative medicine is gaining favor, especially when no drug therapy is currently available to alleviate gluten toxicity. Supplementation with the fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K), vitamin B12, folic acid, and the minerals calcium and iron, as indicated by serum deficiencies, is recommended.10,20 Supplementation with digestive enzymes, which are known to be deficient in patients with CD as a result of villous atrophy, may help break down undigested gluten proteins; research is under way to find a recombinant enzyme therapy.10 Researchers have recently shown that probiotics (specifically, Bifidobacterium lactis) significantly reduce the immune response when incidental exposure to gluten occurs.43

REFRACTORY CELIAC DISEASE

Patients with late-onset CD, especially those not diagnosed until after age 50, may have a diminished or absent response to dietary therapy. In some patients, histologic signs and clinical symptoms persist or relapse after a prior positive response to a strict GFD, despite continued adherence to the diet for longer than 12 months.44 Once other causes have been carefully excluded, these patients are considered to have refractory celiac disease (RCD). Exact prevalence of RCD is unknown, but Tack et al8 estimate it at 5% of all cases of CD. Relapsing CD resulting from poor adherence to the GFD is not considered true RCD.8,16,37,38

According to researchers for the European Celiac Disease working group,8,45 RCD can be divided into types I and II:

• RCD I, in which normal polyclonal T cells are present in the intestinal lumen

• RCD II, in which abnormal clonal T cells infiltrate the intestinal mucosa, representing premalignancy.45

The histologic picture of RCD mimics that of severe CD. Malabsorption complications, lesions in the intestinal mucosa, and inflammatory lymphocytosis are present.44 Some patients, like those with classical CD, have serology test results that are consistent with CD and an initial response to GFD therapy; after months or years, however, this response subsides. Other patients are immediately unresponsive to GFD and lack the serologic markers for CD.8

A differential diagnosis including other explanations for the manifestations of RCD must be carefully reviewed, with each excluded, through the strategies shown in Table 2. This review is essential, as patients with RCD II have a much worse prognosis than those with RCD I; the associated five-year survival rates are 44% to 58%, versus 85% or greater, respectively.36,46

Additionally, the continued autoimmune expansion of aberrant T cells in patients with RCD II causes early conversion to malignancy, usually within four to six years after diagnosis. Enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma is the most common malignancy, occurring in more than 50% of patients with RCD II, and a likely cause of death.3,8,46,47

Treatment for Refractory Celiac Disease

In addition to the GFD, patients with RCD I generally respond well to corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive treatment.8 Use of budesonide, a corticosteroid given in a once-daily, 9-mg dose, has led to almost complete recovery in most patients. Duration of therapy is response-dependent.37

Systemic corticosteroids or other immunosuppressant agents, such as azathioprine, should be reserved for patients with RCD I or RCD II who do not respond to budesonide, as lengthy treatment regimens are required, with considerable risk for adverse effects.35,48

Recently, promising results have been reported in a small, open-label cohort study involving patients with RCD II who underwent five days of treatment with IV cladribine (0.1 mg/kg/d).49

PREVENTION OF CD

A good nutritional start from birth could be the best means of preventing symptomatic CD. According to findings from a meta-analysis of data from four studies, children being breastfed at the time gluten was introduced had a 52% reduction in risk for CD, compared with their peers who were not being breastfed at that time.50

The protection breast milk appears to provide against CD is not clearly understood. One possible mechanism is that breast milk may protect an infant against CD by preventing gastrointestinal infections, as is the case with other infections. The presence of GI infections (eg, rotavirus) in early life could lead to increased permeability of the intestinal mucosa, allowing the passage of gluten into the lamina propria.3,8,50

Extended duration of breastfeeding is also associated with a reduced risk for CD.8,41,50 Long-term studies are needed, however, to determine whether breastfeeding delays CD onset or provides permanent protection against the disorder.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

A recently marketed OTC testing kit for CD is now available in Canada and other countries outside the US; this may be an indication of the growing awareness of the numbers of patients with undiagnosed CD. The test parallels the tTG serum test, which in the US is evaluated only in laboratories; it has comparable specificity and sensitivity, with results within 10 minutes. In the US, the FDA has not yet approved the kit, but domestic testing of the product may soon be under way.51

Alternative treatment modalities are currently focusing on the detoxification of wheat components, rapid enzymatic degradation to reduce exposure to gluten, inducing gluten tolerance, inhibiting permeability of the small intestine to gluten (which, it is thought, may prevent many of the systemic manifestations of CD), and finally, development of an immunomodulatory vaccine.8,33 None of these therapies is yet approved.

IMPLICATIONS OF DELAYED DIAGNOSIS

The unrecognized prevalence of CD is a growing issue, as many symptomatic but unscreened patients are frequently misdiagnosed with IBS, chronic fatigue, or other idiopathic disorders. The silent and latent forms of CD are of the greatest concern, as they show minimal signs and can lead to multiple organ system damage and are implicated in other autoimmune disorders. The longer diagnosis is delayed, the greater is patients’ resistance to dietary therapy, and the less likely that established intestinal and/or neurologic damage can be reversed.10,20,51

The large proportion of undiagnosed celiac patients may account for an accompanying underestimated cost to both the patient and the health care system because of repeated referrals to investigate unexplained disorders before an accurate diagnosis is made. In one recent analysis, mass screening for CD in a young adult population led to improved quality-of-life years by shortening the time to diagnosis and treatment; it was also found cost-effective.52 PCPs must be attentive to patients who may be at high risk for CD and implement combined serum tTG and EMA screening as the initial step in identification and treatment.4,10,11,20 Some form of standardized screening protocol may become inevitable.

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of CD has increased more than fourfold since 1950, and diagnosis is often significantly delayed. Increased awareness is needed among PCPs that CD in adults is likely to manifest with atypical (ie, nongastrointestinal) symptoms and signs. Judicious use of serologic screening for CD would lead to earlier diagnosis and more effective treatment, possibly preventing the potentially lethal refractory disease forms associated with chronic untreated CD.

REFERENCES

1. Ramos M, Orozovich P, Moser K, et al. Health 1. Catassi C, Fasano A. Celiac disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24(6):687-691.

2. AGA Institute. AGA Institute medical position statement on the diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(6):1977-1980.

3. Green PH, Jabri B. Coeliac disease. Lancet. 2003;362(9381):383-391.

4. Catassi C, Kryszak D, Louis-Jacques O, et al. Detection of celiac disease in primary care: a multicenter case-finding study in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(7);1454-1460.

5. Demirçeken FG, Kansu A, Kuloglu Z, et al. Human tissue transglutaminase antibody screening by immunochromatographic line immunoassay for early diagnosis of celiac disease in Turkish children. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2008;19(1):14-21.

6. van der Windt DA, Jellema P, Mulder CJ, et al. Diagnostic testing for celiac disease among patients with abdominal symptoms: a systematic review. JAMA. 2010;303(17):1738-1746.

7. Freeman HJ. Neurological disorders in adult celiac disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008; 22(11):909-911.

8. Tack GJ, Verbeek WHM, Schreurs MWJ, Mulder CJJ. The spectrum of celiac disease: epidemiology, clinical aspects and treatment. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7(4):204-213.

9. Farrell RJ, Kelly CP. Celiac sprue. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(3):180-188.

10. Green PHR, Cellier C. Celiac disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(17):1731-1743.

11. Fasano A, Berti I, Gerarduzzi T, et al. Prevalence of celiac disease in at-risk and not-at-risk groups in the United States: a large multicenter study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(3):286-292.

12. Sud S, Marcon M, Assor E, et al. Celiac disease and pediatric type 1 diabetes: diagnostic and treatment dilemmas. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol. 2010;2010:161285. Epub 2010 Jun 23.

13. Swigonski NL, Kuhlenschmidt HL, Bull MJ, et al. Screening for celiac disease in asymptomatic children with Down syndrome: cost-effectiveness of preventing lymphoma. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):594-602.

14. Bonamico M, Pasquino AM, Mariani P, et al; Italian Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology (SIGEP); Italian Study Group for Turner Syndrome (ISGTS). Prevalence and clinical picture of celiac disease in Turner syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(12): 5495-5498.

15. Giannotti A, Tiberio G, Castro M, et al. Coeliac disease in Williams syndrome. J Med Genet. 2001;38(11):767–768.

16. Alaedini A, Green P. Narrative review: celiac disease: understanding a complex autoimmune disorder. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(4): 289-298.

17. Fröhlich-Reiterer EE, Hofer S, Kaspers S, et al. Screening frequency for celiac disease and autoimmune thyroiditis in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus: data from a German/Austrian multicentre survey. Pediatr Diabetes. 2008;9(6):546-553.

18. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2009. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(1):S13–S61.

19. Losowsky MS. A history of coeliac disease. Dig Dis. 2008;26(2):112-120.

20. Evans KE, Hadjivassilou M, Sanders DS. Understanding ‘silent’ coeliac disease: complications in diagnosis and treatment. Gastrointest Nurs. 2010;8(2):26-32.

21. Lurie Y, Landau DA, Pfeffer J, Oren R. Celiac disease diagnosed in the elderly. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42(1):59-61.

22. Vilppula A, Kaukinen K, Luostarinen L, et al. Increasing prevalence and high incidence of celiac disease in elderly people: a population-based study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009 Jun 29;9:49.

23. Lo W, Sano K, Lebwohl B, et al. Changing presentation of adult celiac disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48(2):395-398.

24. Alaedini A, Okamoto H, Briani C, et al. Immune cross-reactivity in celiac disease: anti-gliadin antibodies bind to neuronal synapsin I. J Immunol. 2007;178(10):6590-6595.

25. Tursi A, Giorgetti G, Brandimarte G, et al. Prevalence and clinical presentation of subclinical/silent celiac disease in adults: an analysis on a 12-year observation. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48(38):462-464.

26. Rostom A, Murray JA, Kagnoff MF. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute technical review on the diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(6):1981-2002.

27. Ferguson A, Arranz E, O’Mahony S. Clinical and pathological spectrum of coeliac disease—active, silent, latent, potential. Gut. 1993;34(2): 150-151.

28. Logan RFA. Problems and pitfalls in epidemiological studies of coeliac disease. In: Auricchio S, Visakorpi JK, eds. Common Food Intolerances 1. Epidemiology of Coeliac Disease (Dynamic Nutrition Research)(Pt 1). Basel, Switzerland: Karger; 1992:14-22.

29. Marsh MN. Gluten, major histocompatibility complex, and the small intestine: a molecular and immunobiologic approach to the spectrum of gluten sensitivity (‘celiac sprue’). Gastroenterology. 1992;102(1):330-354.

30. Oberhuber G, Granditsch G, Vogelsang H. The histopathology of coeliac disease: time for a standardized report scheme for pathologists. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11(10):1185-1194.

31. Corazza GR, Villanaci V. Coeliac disease.

J Clin Pathol. 2005;58(6):573-574.

32. Hadithi M, von Blomberg BM, Crusius JB, et al. Accuracy of serologic tests and HLA-DQ typing for diagnosing celiac disease. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(5):294-302.

33. Lerner A. New therapeutic strategies for celiac disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9(3):144-147.

34. Catassi C, Fasano A. Celiac disease diagnosis: simple rules are better than complicated algorithms. Am J Med. 2010;123(8):691-693.

35. Rubio-Tapia A, Kyle RA, Kaplan EL, et al. Increased prevalence and mortality in undiagnosed celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2009; 137(1):88–93.

36. Harewood GC, Holub JL, Lieberman DA. Variation in small bowel biopsy performance among diverse endoscopy settings: results from a national endoscopic database. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(9):1790-1794.

37. Brar P, Lee S, Lewis S, et al. Budesonide in the treatment of refractory celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(10):2265-2269.

38. Al-Toma A, Verbeek WHM, Hadithi M, et al. Survival in refractory coeliac disease and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma: retrospective evaluation of single-centre experience. Gut. 2007;56(10):1373-1378.

39. Kaukinen K, Mäki M, Partanen J, et al. Celiac disease without villous atrophy: revision of criteria called for. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46(4):879-887.

40. Mohamed BM, Feighery C, Coates C, et al. The absence of a mucosal lesion on standard histological examination does not exclude diagnosis of celiac disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2008; 53(1):52-61.

41. Fasano A, Catassi C. Current approaches to diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease: an evolving spectrum. Gastroenterology. 2001; 120(3):636-651.

42. US Food and Drug Administration. Topic-specific labeling information (2010). www.fda.gov/Food/LabelingNutrition/FoodLabeling GuidanceRegulatoryInformation/Topic-Specific LabelingInformation/default.htm. Accessed March 28, 2011.

43. Lindfors K, Blomqvist T, Juuti-Uusitalo K, et al. Live probiotic Bifidobacterium lactis bacteria inhibit the toxic effects induced by wheat gliadin in epithelial cell culture. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;152(3):552-558.

44. Cellier C, Delabesse E, Helmer C, et al; French Coeliac Disease Study Group. Refractory sprue, coeliac disease, and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. Lancet. 2000;356(9225): 203-208.

45. United European Gastroenterology. When is a coeliac a coeliac? Report of a working group of the United European Gastroenterology Week in Amsterdam, 2001. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13(9):1123-1128.

46. Malamut G, Afchain P, Verkarre V, et al. Presentation and long-term follow-up of refractory celiac disease: comparison of type I with type II. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(1):81-90.

47. Al-Toma A, Goerres MS, Meijer JW, et al. Human leukocyte antigen-DQ2 homozygosity and the development of refractory celiac disease and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(3): 315-319.

48. Mauriño E, Niveloni S, Cherñavsky A, et al. Azathioprine in refractory sprue: results from a prospective, open-label study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(10):2595–2602.

49. Tack GJ, Verbeek WHM, Al-Toma A, et al. Evaluation of cladribine treatment in refractory celiac disease type II. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(4):506–513.

50. Akobeng AK, Ramanan AV, Buchan I, Heller RF. Effect of breast feeding on risk of coeliac disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Arch Dis Child. 2006; 91(1):39-43.

51. Rashid M, Butzner JD, Warren R, et al. Home blood testing for celiac disease: recommendations for management. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55(2):151-153.

52. Hershcovici T, Leshno M, Goldin E, et al. Cost effectiveness of mass screening for coeliac disease is determined by time-delay to diagnosis and quality of life on a gluten-free diet. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(8):901-910.

Celiac disease (CD), also known as gluten-sensitive enteropathy or celiac sprue, is an endocrine disorder whose effects are triggered by the ingestion of gluten—the principle storage protein in wheat, rye, and barley.1-3 CD inflicts damage to the mucosa of the small intestine and subsequently to systemic organ tissues. CD can affect any organ in the body.1 The responsible genetic factors are the human leukocyte antigens, HLA -DQ2 and -DQ8, which are present in 40% of the general population but are found in nearly 100% of patients with CD.1,3,4

Though previously considered uncommon, CD has been estimated to affect more than 1% of the general population worldwide.1,4,5 Currently, CD is most reliably identified by positive serum antibodies, specifically immunoglobulin A (IgA) anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTG) and IgA antiendomysial (EMA) antibodies,6 and by a finding of villous atrophy of the intestinal lining on biopsy. The spectrum of presentations of CD is broad, including the “typical” intestinal features of diarrhea, bloating, abdominal pain, and weight loss; or common “atypical” extraintestinal manifestations, such as anemia, osteoporosis, infertility, and neurologic disturbances (eg, peripheral neuropathy7).8 See Table 1.8,9

Prevalence of CD is greater among those with a family history of CD; with autoimmune diseases, especially type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and thyroiditis; and with certain genetic disorders (ie, Down, Turner, and Williams syndromes).8-15 Because atypical features dominate in older children and adults, many cases escape diagnosis, and patients may be exposed to serious long-term complications, such as infertility and cancer.1

CD is a lifelong condition, necessitating the complete exclusion of gluten-containing products from the diet. In the US food industry, gluten is used in numerous food applications, complicating the patient education and lifestyle changes needed to implement and maintain a gluten-free diet (GFD). However, if a GFD is not strictly followed, the patient’s quality of life can be seriously impaired.1,4,5

AWARENESS ESSENTIAL IN PRIMARY CARE

For the primary care provider (PCP), there is no shortage of patients with gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, thyroid disease, diabetes, anemia, fatigue, or dysmenorrhea; additionally, PCPs regularly treat patients for a number of associated disorders, including anxiety, irritability, and attention deficit. Yet how likely are PCPs to screen patients with these symptoms for CD? And how many patients with CD never receive a diagnosis of the disorder?

In fact, it has been estimated that more than 90% of persons affected by CD are currently undiagnosed.1,4 In one study involving mass screening of 1,000 children ages 2 to 18, it was determined that almost 90% of celiac-positive children had not previously been diagnosed.5 Similarly, in a cohort of 976 adults (median age, 54.3), the diagnostic rate for CD was initially low at 0.27 cases per thousand visits but increased to 11.6 cases per thousand visits after implementation of active screening.4 Based on these data, it has been estimated that more than 2.7 million Americans unknowingly carry this potentially life-threatening genetic disease.1,4,16

Given the potential patient population with undetected, untreated CD, some researchers consider the disorder one of the most common lifelong diseases in the US.1,8,16 CD is closely associated with T1DM and autoimmune thyroiditis, with cross- prevalence at 11% and 6.7%, respectively.8,12,17 The close association between T1DM and CD led the American Diabetes Association18 to amend guidelines in 2009, suggesting screening for CD in all patients newly diagnosed with T1DM.

PATIENT PRESENTATION: ADULTS VERSUS CHILDREN

Most infants and young children with CD present with the typical or “classic” triad of signs: short stature, failure to thrive, and diarrhea; in individual patients, however, the impact of genetics and exposure to gluten over time can cause considerable variation in patient presentation. As patients with undiagnosed CD age, they may present quite differently or even revert to a latent stage and become asymptomatic.19,20

In two separate reviews, it was noted that classic symptoms of CD are not evident in a majority of older children and adults; instead, anemia and fatigue were the predominating symptoms.12,20An important note: The patient with no symptoms or atypical signs of CD may still be experiencing significant damage, inflicted by gluten-induced antibodies, to the intestinal lining and/or mucosal linings in other organ systems—perhaps for years before the disease becomes evident.20

Clinical Findings Differ With Age, Gender

Historically, CD was considered a pediatric syndrome; however, a diagnosis of CD has become increasingly common among older children and adults, especially elderly patients, although symptoms in the latter group are subtle.21-23 Recent, active CD is being diagnosed among men older than 55 more commonly than in women of this age-group; women are generally younger at diagnosis but have experienced symptoms longer.22,23 This later onset in men suggests that antibody seropositivity and the associated active disease may be triggered later in life.8,22

A variety of findings have been reported in the history and physical exam of most patients who present with CD.The most prevalent signs and symptoms are abdominal pain, frequent loose stools, weight loss, joint pain, and weakness.8,11,16 Unlike the pediatric patient with the classic triad of symptoms, adults usually experience more generalized GI manifestations, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), abdominal pain, or acid reflux.10

Many patients have no GI symptoms but may present solely with fatigue, arthralgias, or myalgia.20 In fact, more than 50% of adults with CD present with atypical or extraintestinal disorders, such as anemia, infertility, osteoporosis, neurologic problems, or other autoimmune disorders.8,16,23,24 It is important for clinicians to note that atypical is somewhat typical in the older patient who presents with CD.

Patients with asymptomatic or silent CD, (see “Classification and Pathology,” below) lack both classic and atypical symptoms but still have villous atrophy, usually discovered during endoscopy being conducted for other reasons.8 Because of its predominantly atypical presentations, CD is considered a multisystem endocrine condition rather than one that is mainly gastrointestinal.8,16,25,26

CLASSIFICATION AND PATHOLOGY

Though frequently a silent disorder, CD typically progresses through four stages: classical, atypical, latent, and silent. Clinicians should strive to become fully aware of each stage and its implications.8,26,27

The classical form is primarily diagnosed in children ages 6 to 18 months. It is characterized by villous atrophy and typical symptoms of intestinal malabsorption.8

The patient with atypical CD has minor intestinal symptoms, but architectural abnormalities can be found in the mucosa of the small intestine. This patient is likely to present with various extraintestinal disorders, including osteoporosis, anemia, infertility, and neuropathies.7,8

In the latent form of CD, the HLA-DQ2 and/or -DQ8 genetic markers are present. Serology for CD may be positive, but the intestinal mucosa may be normal. The patient may or may not be experiencing extraintestinal symptoms. In patients with latent CD, the gluten-associated changes appear later in life.8 The precise trigger for late activation of the disease, though apparently linked to genetics and gluten exposure, remains elusive.20,24

The silent form of CD is marked by mucosal abnormalities in the small intestine and usually by positive CD serology, but it is asymptomatic. The iceberg theory of celiac disease28 (see figure28) has been proposed to explain CD’s hidden manifestations over time.

In patients with atypical, latent, or silent CD, the condition is sometimes detected incidentally during screening of at-risk groups or by endoscopy performed for other reasons.8 Most of these patients respond well to GFD therapy, noting both physical and psychological improvement—suggesting that these patients, even though asymptomatic and seemingly healthy, may have been experiencing minor manifestations of undiagnosed CD for many years: decreased appetite, fatigue, and even behavioral abnormalities.1,8

Histopathologic analysis of abnormalities found on biopsy of the small intestine relies on the four-stage Marsh classification29:

• Marsh 0: normal mucosa

• Marsh I: intraepithelial lymphocytosis

• Marsh II: intraepithelial lymphocytosis with crypt hyperplasia

• Marsh III: intraepithelial lymphocytosis with crypt hyperplasia and villous atrophy.8,29 Modifications to this classification have been made by Oberhuber30,31 to denote the degree of villous flattening32 (ie, IIIa, IIIb, IIIc).

Villous atrophy of the mucosa has long been considered the hallmark of CD, and its detection, according to the American Gastroenterological Association,2,26 remains the gold standard in confirming a diagnosis of CD.4,16,26 However, early screening (ie, serologic testing for tTG and EMA) is the necessary initial step in ensuring diagnostic accuracy, as other conditions can cause villous atrophy, and latent CD can coexist with normal intestinal mucosa.10

Avoiding Diagnostic Delays

Because of the broad spectrum of unrelated GI signs in all ages and the subtle presentation in adults, diagnosis of CD in this patient population is frequently delayed for estimated periods ranging from five to 11 years.4,11,23,33

Improving clinician awareness of the manifestations of CD is essential34; too frequently, the common symptoms of probable CD are treated as individual idiopathic disorders by both PCPs and secondary specialists, who prescribe proton pump inhibitors, antihistamines, cathartics, and/or antimotility drugs for years without ruling out a common, easily identified genetic disease. Even though the prevalence of CD has recently been shown to have increased more than fourfold since 1950,35 serologic testing for CD is not widely implemented by PCPs.4,11,20

Specialists, too, may be slow to recognize this treatable autoimmune disorder. In a recent nationwide study, it was found that gastroenterologists performed a small-bowel biopsy in less than 10% of their patients who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) for likely symptoms of CD.36 Relying solely on clinical expertise and visual recognition of intestinal abnormalities can delay diagnosis for years.4,36 Many patients may never be given a correct diagnosis of CD.

The Role of Serologic Testing

Current data demonstrate that autoimmune diseases are on the rise,8,16,36 and CD can be the primary cause or a contributing factor in several other disorders (see Table 28,16,37,38). Gastroenterologists may be correct in stating that biopsy is the only way to make a diagnosis of CD or to stage CD-associated intestinal damage4,26; yet by implementing a protocol of serologic testing for tTG and EMA in at-risk patients, PCPs could prevent a missed diagnosis on EGD when biopsy has not been considered, as in the case of atypical CD; or when biopsy results are negative in a patient with latent CD.39,40

Because of its high negative predictive value, serologic testing should be conducted first to significantly reduce the probability of suspected CD. Such selective screening should be performed by the PCP before invasive testing by the gastroenterologist and before long-term empiric treatment for idiopathic GERD, IBS, or other unexplained disorders.32,40

Thus, it has been recommended that PCPs perform screening for CD in patients with unexplained chronic GI disturbances or a familial prevalence of CD, or in those who present with the atypical signs of CD or with associated disorders.1,10,16,20 Whether serologic screening results are positive or negative for CD, the patient with classic GI symptoms should undergo endoscopy with biopsy to confirm active disease and to evaluate the extent of intestinal damage—or to explore other causes.26,39 An algorithm2,4,8,11,16,26 illustrating suggested screening, treatment, and follow-up strategies for patients at high risk for CD is shown below.

Catassi and Fasano34 recently proposed a “four out of five” rule, by which diagnosis of CD may be confirmed in patients with at least four of the following five criteria:

• Typical symptoms of CD

• Positive serology (ie, IgA tTG and IgA EMA antibodies)

• Genetic susceptibility (as confirmed by the presence of HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8)

• Small intestine biopsy results indicating celiac enteropathy

• Improvement of CD signs and symptoms following implementation of the GFD.34

CURRENT TREATMENT AND ASSOCIATED CHALLENGES

Because gluten consumption is the principal trigger of CD pathology, a GFD is considered the safest, most effective therapy for the disorder.1,8,10,11,16,19 Implementing and maintaining the GFD involves a considerable learning curve for the patient, the patient’s family, and possibly the provider; to achieve complete recovery, all involved must become knowledgeable regarding gluten-free and gluten-containing products. The patient must be willing and able to avoid those that contain gluten and bear the potentially high costs8 of gluten-free foods.

Even for patients with CD who are determined to comply with the GFD, gluten monitoring can be difficult. There are ways to determine what is a safe level of gluten ingestion for each patient, but trace amounts of gluten are found in many products, including some that are marked “gluten-free.”1,41 The FDA has proposed that a product labeled gluten-free may contain no more than 20 parts per million (ppm, ie, 20 mg/kg) of gluten.42 In other countries, however, acceptable levels may be as high as 200 ppm (200 mg/kg)—which are considered well above the trigger amounts in the average patient with CD.1,41 The complex nature of each patient’s sensitivity to gluten and the ubiquitous presence of gluten as a food source in both industrialized and developing countries make adherence to the GFD challenging.10

It is critical for the PCP to help the patient review all of his or her prescription and OTC pharmaceuticals and nutritional supplements, as these may contain hidden gluten in the form of modified starches and other fillers.41 It may be also advisable to involve the patient’s pharmacist, requesting an assessment for agents that may be suspect.

A management team approach may ensure the most integrative care. In addition to the PCP and the pharmacist, such a team might include a gastroenterologist, an endocrinologist, a nutritionist, and a psychologist, who may be needed to help the patient confront the great life adjustment required, in addition to addressing other behavioral disorders that are common in patients with CD.10,26

See the box for resources that may be beneficial for both patients and their clinicians.

Alternative Medicine Options

Alternative medicine is gaining favor, especially when no drug therapy is currently available to alleviate gluten toxicity. Supplementation with the fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K), vitamin B12, folic acid, and the minerals calcium and iron, as indicated by serum deficiencies, is recommended.10,20 Supplementation with digestive enzymes, which are known to be deficient in patients with CD as a result of villous atrophy, may help break down undigested gluten proteins; research is under way to find a recombinant enzyme therapy.10 Researchers have recently shown that probiotics (specifically, Bifidobacterium lactis) significantly reduce the immune response when incidental exposure to gluten occurs.43

REFRACTORY CELIAC DISEASE