User login

Cervical Cancer Patients: Need Not Forgo Fertility

- Lesions should be smaller than 2 cm to achieve the most favorable outcomes. Masses up to 3 cm can be resected, but the recurrence rate is higher, especially if the tumor has invaded the lymph-vascular space.

- Resect the cervix 0.5 to 1 cm distal to the isthmus. If the proximal incision margin has cleared the cancer, close the peritoneum and suture the vaginal mucosa to the cervical stump.

- The rate of second-trimester loss is elevated as a result of subclinical chorioamnionitis due to exposure of the membranes to vaginal flora. The Saling procedure has been shown to prevent ascending infections.

- The majority of women who have undergone radical vaginal trachelectomy successfully conceive, and most pregnancies result in a live birth.

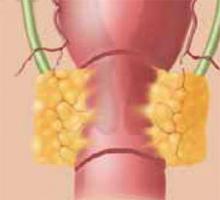

While the mean age at which cervical cancer is diagnosed is 51, approximately 10% to 15% of women will develop cervical cancer in their reproductive years.1 Traditionally, early-stage cervical cancers in young women have been treated by radical hysterectomy, resulting in permanent sterility. Now, these patients have an alternative: radical vaginal trachelectomy. This entails the excision of the majority of the cervix and parametria, with preservation of the uppermost portion of the cervix and uterus, allowing the possibility of future childbearing (Figure 1).

The rate of second trimester loss is elevated in radical vaginal trachelectomy patients.

A conservative approach for the treatment of early-stage cervical cancer was first proposed approximately 20 years ago by Aburel, a Romanian gynecologist.2 He reported his experience with the abdominal “subfundic radical hysterectomy.” However, subsequent successful pregnancies did not occur, and the procedure was abandoned. In 1987, the French gynecologist Dargent began performing radical vaginal trachelectomy in concert with laparoscopic pelvic lymphadenectomy. He published his initial results in 1994.3 Thereafter, researchers in Quebec,4 Toronto,5 and London6 have reported their experiences with this procedure. Currently, almost 200 cases are reported in the literature. After describing patient selection and the technique, I will review the data regarding complications and oncologic and reproductive outcomes.

Figure 1

The shaded area indicates the portion of the cervix and upper vagina that will be resected during the procedure.

Patient selection

Although the potential benefit—preservation of fertility—is profound, the percentage of patients with cervical cancer who are candidates for radical vaginal trachelectomy is relatively small. The indications are the presence of an invasive cervical cancer (stage Ia2, Ib1, or IIa), the desire for future childbearing, no involvement of the upper endocervical canal, and no evidence of metastases on preoperative chest radiography and physical exam. Lesions 2 cm or smaller are ideal. While masses up to 3 cm can be resected, the recurrence rate is higher (similar to that after radical hysterectomy). Further, the absence of lymph-vascular space involvement (LVSI) is preferred, but its presence is not an absolute contraindication to the surgery.

Technique

Prior to the radical vaginal trachelectomy, perform a pelvic lymphadenectomy either transperitoneally or retroperitoneally, depending on the surgeon’s preference. If immediate histopathologic analysis of the lymph nodes is negative for metastases, proceed with the trachelectomy.

With the patient in the dorsal lithotomy position, grasp the vagina approximately 3 cm from the cervix and inject it with lidocaine. Then, using a scalpel, incise the vagina at the 12 o’clock position. After developing the vaginal cuff, suture it over the tumor using an absorbable suture in a figure-of-eight stitch, which provides traction to help identify proper surgical planes. Using the technique for a vaginal hysterectomy, create the vesicovaginal space. Then grasp the vagina at the 9 o’clock and 11 o’clock positions and sharply develop the paravesical space. Access to this space is located at approximately the 10 o’clock position. Repeat the same procedure on the contralateral side. (In this case, grasp the vagina at the 3 o’clock and 1 o’clock positions; access to this space is located at the 2 o’clock position.)

In the hands of an experienced surgeon, the complication rate is comparable to that of radical hysterectomy.

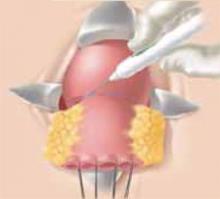

Place retractors in the paravesical spaces and retract the bladder anteriorly. The bladder pillars, which contain the ureters and are located in between the vesicovaginal and paravesical spaces, are now fully exposed (Figure 2). Palpate the ureter in each bladder pillar, then sharply divide each pillar, using cautery for hemostasis as needed. The ureters are now visible, as are the descending branches of the uterine artery.

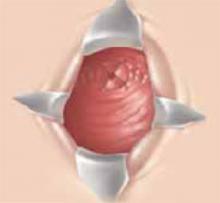

At this point, the posterior cul-de-sac and the pararectal spaces can be accessed. Divide the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments 2 cm from the cervix (Figure 3). Retract the ureters and clamp the descending branch of the uterine artery. Finally, resect the cervix 0.5 to 1 cm distal to the isthmus and send the specimen to pathology (Figure 4). If the proximal (deep) incision margin has cleared the cancer, close the peritoneum and place a cerclage using a strong nonabsorbable suture (Figure 5). I prefer a double cerclage of No. 1 polyester or polypropylene. Then suture the vaginal mucosa to the cervical stump, not to the mucosa, to help prevent postoperative stenosis (Figure 6).

Prior to discharge, attempt a bladder challenge (usually postoperative day 2). In the rare instance the woman is unable to void, discharge the patient and repeat the bladder challenge in 1 week.

Figure 2

After dividing the bladder pillar, located between the vesicovaginal and paravesical spaces, identify the ureter (the tubular structure at 12 o’clock).

Figure 3

Access the posterior cul-de-sac and the pararectal spaces, and then divide the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments 2 cm from the cervix.

Figure 4

After retracting the ureters and clamping the descending branch of the uterine artery, resect the cervix 0.5 to 1 cm distal to the isthmus.

Figure 5

If the proximal incision margin has cleared the cancer, close the peritoneum and place a cerclage using a strong nonabsorbable suture.

Figure 6

Finally, suture the vaginal mucosa to the cervical stump, not to the mucosa, to help prevent postoperative stenosis.

Complications

The rate of morbidity associated with this procedure varies from 13% to 25%.3-5 (In the hands of an experienced surgeon, the complication rate is comparable to that of radical hysterectomy.) Dargent et al reported complications in 7 of 47 women (1 required reoperation for sidewall hemorrhage, 5 had postoperative hematomas, and 1 had prolonged urinary retention).3 Similarly, Roy and Plante reported 2 external iliac artery injuries, 1 conversion to laparotomy for hemostasis, and 1 cystotomy among 30 patients who underwent the procedure.4 Covens et al encountered complications in 8 of 32 women, including 6 cystotomies, 1 enterotomy, and 1 external iliac artery injury.5 It is important to note that the vascular injuries most commonly occurred during the lymphadenectomy. To date, no operative mortalities have been reported in association with radical trachelectomy.

Oncologic outcome

Roy recently summarized the oncologic outcome of women undergoing radical vaginal trachelectomy for early-stage cervical cancer at medical centers in Lyon, Quebec, and Toronto.7 This data, as well as that from London and the Women’s Hospital in Los Angeles, are shown in Table 1. (Women who underwent radical trachelectomy followed by hysterectomy due to lack of lesion clearance are excluded.)

Among the almost 200 cases, the cancer recurrence rate is low, and viable pregnancies are clearly possible.

Seven of 197 women (3.5%) had positive lymph nodes discovered postoperatively. However, all of them have remained disease-free. (Most of the women received pelvic radiotherapy postoperatively.) To date, there have been 6 recurrences (3%) reported, 2 of which have been in women with neuroendocrine tumors (a histology associated with an especially poor prognosis). Excluding the 2 neuroendocrine tumors, the recurrence rate drops to 2.1%. All of the 4 remaining women had negative lymph nodes and LVSI, and 2 had lesions larger than 2 cm (Table 2).

Of the 92 women whose cervical cancers did not invade the lymph-vascular space, none experienced a recurrence. Similarly, smaller tumors were associated with a low recurrence rate; in women with lesions 2 cm or smaller, only 1.6% had a recurrence. Women with lesions larger than 2 cm or with LVSI had a somewhat higher recurrence rate (10.5% and 11.1%, respectively), as would be expected based on our knowledge of recurrence risk after radical hysterectomy (Table 3).8,9

There are no prospective randomized trials that have analyzed oncologic outcome in women undergoing radical vaginal trachelectomy as compared to radical hysterectomy. Clearly, such a trial would not be feasible. However, the results of a 1999 retrospective case-control study are promising. In this trial, Covens compared the outcome of 32 women who underwent radical vaginal trachelectomy (all of whom had negative nodes and none of whom received radiation) to that of 30 women who underwent radical hystererctomy (matched for age, tumor size, histology, depth of invasion, and presence of LVSI).5 A second, unmatched, control group consisted of all women who had undergone radical hysterectomy for tumors 2 cm or smaller, had negative nodes, and had not received postoperative pelvic radiation. After a median follow-up of 23.4 months for the study patients, 46.5 months for the matched control patients, and 50.3 months for the unmatched control group, the 2-year actuarial recurrence-free survival was 95%, 97%, and 100%, respectively. These differences were not statistically significant.

TABLE 1

Oncologic outcome

| LYON N=71 | QUEBEC N=43 | TORONTO N=53 | LOSANGELES N=20 | LONDON N=9 | TOTAL N=196 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up (mean) | 60 | 36 | 30 | 18.5 | 2 | - |

| Positive nodes | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 7 (3.5%) |

| Recurrence | 3* | 2* | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6† (3%) |

| *One patient in each had a neuroendocrine tumor | ||||||

| †Recurrence rate is 2.1%, if women with neuroendocrine tumors are excluded. | ||||||

TABLE 2

Recurrences after radical vaginal trachelectomy*

| SIZE | HISTOLOGY | LN STATUS | LVSI | SITE | STATUS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 cm | Adenocarcinoma | Negative | Yes | Aortic LN | DOD |

| 2.5 cm | Squamous | Negative | Yes | Pelvic LN | NED |

| 3 cm | Squamous | Negative | Yes | Pelvis | DOD |

| <2 cm | Adenocarcinoma | Negative | Yes | Pelvis | DOD |

| LN=lymph node | |||||

| LVSI=lymph-vascular space involvement | |||||

| DOD=dead of disease | |||||

| NED=no evidence of disease | |||||

| *Neuroendocrine tumors excluded | |||||

TABLE 3

Site recurrence by size and LVSI*

| UTERUS | PELVIS | DISTANT | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size | ||||

| ≤2 cm (n=125) | 0 | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (0.8%) | 2 (1.6%) |

| >2 cm (n=19) | 0 | 2 (10.5%) | 0 | 2 (10.5%) |

| LVSI | ||||

| No (n=92) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Yes (n=36) | 0 | 3 (8.3%) | 1 (2.8%) | 4 (11.1%) |

| LVSI=lymph-vascular space involvement | ||||

| *Neuroendocrine tumors excluded | ||||

Reproductive outcome

Most researchers have reported that the majority of women attempting to conceive have been successful, and that most pregnancies result in a live birth (Table 4). The rate of second-trimester loss is clearly elevated in women who have undergone radical vaginal trachelectomy. The likely reason: the development of subclinical chorioamnionitis due to an inadequate mucus plug and exposure of the membranes to vaginal flora. To combat this problem, Dargent began performing the Saling procedure at 14 weeks’ gestation.2 This entails approximating the vaginal mucosa over the cervix to provide a barrier to ascending infections. Since performing this technique, Dargent has not observed any cases of second-trimester loss. To date, this technique has not been adopted by other medical centers.

TABLE 4

Reproductive outcome

| LYON N=71 | QUEBEC N=43 | TORONTO N=53 | LOS ANGELES N=20 | LONDON N=9 | TOTAL N=196 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. pregnancies | 44 (27)† | 15 (11) | 9 (7)† | 3 (3)† | 7 (4) | 78 |

| Live births | 23 | 8 | 5 | 3‡ | 3 | 42 |

| Neonatal deaths | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| First-trimester loss | 6 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 14 |

| TAB | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Ectopic | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Second-trimester loss | 8 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 12 |

| Pregnancy ongoing | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Numbers in parentheses represent number of women who were able to achieve a pregnancy | ||||||

| *5 pregnancies at the time of RVT | ||||||

| †1 pregnancy at the time of RVT | ||||||

| ‡1 set of twins | ||||||

| TAB=therapeutic abortion | ||||||

Conclusion

Based on the available data, the recurrence rate for women with squamous and adenocarcinomas appears to be low and comparable to that observed in women undergoing radical hysterectomy. Women with lesions larger than 2 cm or whose tumors have invaded the lymph-vascular space have a higher rate of recurrence, though not necessarily higher than if they had undergone radical hysterectomy.8,9

However, this data must be interpreted with caution. The majority of recurrences reported have been located in the pelvis, raising the concern that the parametrial resection at the time of radical trachelectomy may be inadequate. Yet, recurrences after radical hysterectomy also tend to be local rather than distant in non-irradiated patients.9,10 Also, the follow-up for women undergoing radical trachelectomy has been relatively short, and the number of women with lesions larger than 2 cm who have undergone this procedure is small. Thus, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the safety and efficacy of radical vaginal trachelectomy in this group.

Nonetheless, this technique appears to be a reasonable option for women with early-stage cervical cancer who desire future fertility. Among the almost 200 cases reported, the cancer recurrence rate is low, and viable pregnancies are clearly possible. However, longer follow-up is desirable. To meet this need, centers performing the procedure are forming a registry to better track both oncologic and reproductive outcomes. Further, more research is needed as to whether the Saling procedure will improve reproductive outcome and whether women with lesions larger than 2 cm and/or tumors invading the lymph-vascular space are at greater risk of recurrence with radical trachelectomy than if they had undergone radical hysterectomy.

At present, I offer radical vaginal trachelectomy to reproductive-age women with lesions 2 cm or smaller who are extremely desirous of future fertility. If the lesion is larger than 2 cm but is distal so that clearance appears feasible, I inform patients that there is limited data available regarding outcome, especially if LVSI is present.

The author reports no financial relationship with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article.

1. Van der Vange N, Woverling G, Ketting B, et al. The prognosis of cervical cancer associated with pregnancy: a matched cohort study. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:1022-1026.

2. Aburel E. Colpohistorectomia largita subfundica. In: Sirbu P, ed. Chirurgica Gynecologica. Bucharest, Romania: Editura Medicala Pub; 1981;714-721.

3. Dargent D, Martin X, Sacchetoni A, Mathevet P. Laparoscopic vaginal radical trachelectomy. Cancer. 2000;88:1877-1882.

4. Roy M, Plante M. Pregnancies after radical vaginal trachelectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1491-1496.

5. Covens A, Shaw P, Murphy J, DePetrillo D, Lickrish G, LaFramboise S, Rosen B. Is radical trachelectomy a safe alternative to radical hysterectomy for patients with stage IA-B carcinoma of the cervix? Cancer. 1999;86:2273-2279.

6. Shepherd JH, Crawford RAF, Oram DH. Radical trachelectomy: a way to preserve fertility in the treatment of early cervical cancer. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:912-916.

7. Roy M. Vaginal radical trachelectomy in early-stage cervical cancer. Presented at: Advanced Laparoscopic and Vaginal Surgery in Gynecologic Oncology; June 5-6, 2000; University of Southern California, Los Angeles, Calif,

8. Delgado G, Bundy B, Zaino R, Bernd-Uwe S, Creasman WT, Major F. Prospective surgical-pathological study of diseasefree interval in patients with stage IB squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 1990;38:352-357.

9. Hopkins MP, Morley GW. Radical hysterectomy versus radiation therapy for stage IB squamous cell cancer of the cervix. Cancer. 1991;68:272-277.

10. Sedlis A, Bundy BN, Rotman MZ, Lentz SS, Muderspach LI, Zaino RJ. A randomized trial of pelvic radiation therapy versus no further therapy in selected patients with stage IB carcinoma of the cervix after radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;73:177-183.

- Lesions should be smaller than 2 cm to achieve the most favorable outcomes. Masses up to 3 cm can be resected, but the recurrence rate is higher, especially if the tumor has invaded the lymph-vascular space.

- Resect the cervix 0.5 to 1 cm distal to the isthmus. If the proximal incision margin has cleared the cancer, close the peritoneum and suture the vaginal mucosa to the cervical stump.

- The rate of second-trimester loss is elevated as a result of subclinical chorioamnionitis due to exposure of the membranes to vaginal flora. The Saling procedure has been shown to prevent ascending infections.

- The majority of women who have undergone radical vaginal trachelectomy successfully conceive, and most pregnancies result in a live birth.

While the mean age at which cervical cancer is diagnosed is 51, approximately 10% to 15% of women will develop cervical cancer in their reproductive years.1 Traditionally, early-stage cervical cancers in young women have been treated by radical hysterectomy, resulting in permanent sterility. Now, these patients have an alternative: radical vaginal trachelectomy. This entails the excision of the majority of the cervix and parametria, with preservation of the uppermost portion of the cervix and uterus, allowing the possibility of future childbearing (Figure 1).

The rate of second trimester loss is elevated in radical vaginal trachelectomy patients.

A conservative approach for the treatment of early-stage cervical cancer was first proposed approximately 20 years ago by Aburel, a Romanian gynecologist.2 He reported his experience with the abdominal “subfundic radical hysterectomy.” However, subsequent successful pregnancies did not occur, and the procedure was abandoned. In 1987, the French gynecologist Dargent began performing radical vaginal trachelectomy in concert with laparoscopic pelvic lymphadenectomy. He published his initial results in 1994.3 Thereafter, researchers in Quebec,4 Toronto,5 and London6 have reported their experiences with this procedure. Currently, almost 200 cases are reported in the literature. After describing patient selection and the technique, I will review the data regarding complications and oncologic and reproductive outcomes.

Figure 1

The shaded area indicates the portion of the cervix and upper vagina that will be resected during the procedure.

Patient selection

Although the potential benefit—preservation of fertility—is profound, the percentage of patients with cervical cancer who are candidates for radical vaginal trachelectomy is relatively small. The indications are the presence of an invasive cervical cancer (stage Ia2, Ib1, or IIa), the desire for future childbearing, no involvement of the upper endocervical canal, and no evidence of metastases on preoperative chest radiography and physical exam. Lesions 2 cm or smaller are ideal. While masses up to 3 cm can be resected, the recurrence rate is higher (similar to that after radical hysterectomy). Further, the absence of lymph-vascular space involvement (LVSI) is preferred, but its presence is not an absolute contraindication to the surgery.

Technique

Prior to the radical vaginal trachelectomy, perform a pelvic lymphadenectomy either transperitoneally or retroperitoneally, depending on the surgeon’s preference. If immediate histopathologic analysis of the lymph nodes is negative for metastases, proceed with the trachelectomy.

With the patient in the dorsal lithotomy position, grasp the vagina approximately 3 cm from the cervix and inject it with lidocaine. Then, using a scalpel, incise the vagina at the 12 o’clock position. After developing the vaginal cuff, suture it over the tumor using an absorbable suture in a figure-of-eight stitch, which provides traction to help identify proper surgical planes. Using the technique for a vaginal hysterectomy, create the vesicovaginal space. Then grasp the vagina at the 9 o’clock and 11 o’clock positions and sharply develop the paravesical space. Access to this space is located at approximately the 10 o’clock position. Repeat the same procedure on the contralateral side. (In this case, grasp the vagina at the 3 o’clock and 1 o’clock positions; access to this space is located at the 2 o’clock position.)

In the hands of an experienced surgeon, the complication rate is comparable to that of radical hysterectomy.

Place retractors in the paravesical spaces and retract the bladder anteriorly. The bladder pillars, which contain the ureters and are located in between the vesicovaginal and paravesical spaces, are now fully exposed (Figure 2). Palpate the ureter in each bladder pillar, then sharply divide each pillar, using cautery for hemostasis as needed. The ureters are now visible, as are the descending branches of the uterine artery.

At this point, the posterior cul-de-sac and the pararectal spaces can be accessed. Divide the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments 2 cm from the cervix (Figure 3). Retract the ureters and clamp the descending branch of the uterine artery. Finally, resect the cervix 0.5 to 1 cm distal to the isthmus and send the specimen to pathology (Figure 4). If the proximal (deep) incision margin has cleared the cancer, close the peritoneum and place a cerclage using a strong nonabsorbable suture (Figure 5). I prefer a double cerclage of No. 1 polyester or polypropylene. Then suture the vaginal mucosa to the cervical stump, not to the mucosa, to help prevent postoperative stenosis (Figure 6).

Prior to discharge, attempt a bladder challenge (usually postoperative day 2). In the rare instance the woman is unable to void, discharge the patient and repeat the bladder challenge in 1 week.

Figure 2

After dividing the bladder pillar, located between the vesicovaginal and paravesical spaces, identify the ureter (the tubular structure at 12 o’clock).

Figure 3

Access the posterior cul-de-sac and the pararectal spaces, and then divide the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments 2 cm from the cervix.

Figure 4

After retracting the ureters and clamping the descending branch of the uterine artery, resect the cervix 0.5 to 1 cm distal to the isthmus.

Figure 5

If the proximal incision margin has cleared the cancer, close the peritoneum and place a cerclage using a strong nonabsorbable suture.

Figure 6

Finally, suture the vaginal mucosa to the cervical stump, not to the mucosa, to help prevent postoperative stenosis.

Complications

The rate of morbidity associated with this procedure varies from 13% to 25%.3-5 (In the hands of an experienced surgeon, the complication rate is comparable to that of radical hysterectomy.) Dargent et al reported complications in 7 of 47 women (1 required reoperation for sidewall hemorrhage, 5 had postoperative hematomas, and 1 had prolonged urinary retention).3 Similarly, Roy and Plante reported 2 external iliac artery injuries, 1 conversion to laparotomy for hemostasis, and 1 cystotomy among 30 patients who underwent the procedure.4 Covens et al encountered complications in 8 of 32 women, including 6 cystotomies, 1 enterotomy, and 1 external iliac artery injury.5 It is important to note that the vascular injuries most commonly occurred during the lymphadenectomy. To date, no operative mortalities have been reported in association with radical trachelectomy.

Oncologic outcome

Roy recently summarized the oncologic outcome of women undergoing radical vaginal trachelectomy for early-stage cervical cancer at medical centers in Lyon, Quebec, and Toronto.7 This data, as well as that from London and the Women’s Hospital in Los Angeles, are shown in Table 1. (Women who underwent radical trachelectomy followed by hysterectomy due to lack of lesion clearance are excluded.)

Among the almost 200 cases, the cancer recurrence rate is low, and viable pregnancies are clearly possible.

Seven of 197 women (3.5%) had positive lymph nodes discovered postoperatively. However, all of them have remained disease-free. (Most of the women received pelvic radiotherapy postoperatively.) To date, there have been 6 recurrences (3%) reported, 2 of which have been in women with neuroendocrine tumors (a histology associated with an especially poor prognosis). Excluding the 2 neuroendocrine tumors, the recurrence rate drops to 2.1%. All of the 4 remaining women had negative lymph nodes and LVSI, and 2 had lesions larger than 2 cm (Table 2).

Of the 92 women whose cervical cancers did not invade the lymph-vascular space, none experienced a recurrence. Similarly, smaller tumors were associated with a low recurrence rate; in women with lesions 2 cm or smaller, only 1.6% had a recurrence. Women with lesions larger than 2 cm or with LVSI had a somewhat higher recurrence rate (10.5% and 11.1%, respectively), as would be expected based on our knowledge of recurrence risk after radical hysterectomy (Table 3).8,9

There are no prospective randomized trials that have analyzed oncologic outcome in women undergoing radical vaginal trachelectomy as compared to radical hysterectomy. Clearly, such a trial would not be feasible. However, the results of a 1999 retrospective case-control study are promising. In this trial, Covens compared the outcome of 32 women who underwent radical vaginal trachelectomy (all of whom had negative nodes and none of whom received radiation) to that of 30 women who underwent radical hystererctomy (matched for age, tumor size, histology, depth of invasion, and presence of LVSI).5 A second, unmatched, control group consisted of all women who had undergone radical hysterectomy for tumors 2 cm or smaller, had negative nodes, and had not received postoperative pelvic radiation. After a median follow-up of 23.4 months for the study patients, 46.5 months for the matched control patients, and 50.3 months for the unmatched control group, the 2-year actuarial recurrence-free survival was 95%, 97%, and 100%, respectively. These differences were not statistically significant.

TABLE 1

Oncologic outcome

| LYON N=71 | QUEBEC N=43 | TORONTO N=53 | LOSANGELES N=20 | LONDON N=9 | TOTAL N=196 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up (mean) | 60 | 36 | 30 | 18.5 | 2 | - |

| Positive nodes | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 7 (3.5%) |

| Recurrence | 3* | 2* | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6† (3%) |

| *One patient in each had a neuroendocrine tumor | ||||||

| †Recurrence rate is 2.1%, if women with neuroendocrine tumors are excluded. | ||||||

TABLE 2

Recurrences after radical vaginal trachelectomy*

| SIZE | HISTOLOGY | LN STATUS | LVSI | SITE | STATUS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 cm | Adenocarcinoma | Negative | Yes | Aortic LN | DOD |

| 2.5 cm | Squamous | Negative | Yes | Pelvic LN | NED |

| 3 cm | Squamous | Negative | Yes | Pelvis | DOD |

| <2 cm | Adenocarcinoma | Negative | Yes | Pelvis | DOD |

| LN=lymph node | |||||

| LVSI=lymph-vascular space involvement | |||||

| DOD=dead of disease | |||||

| NED=no evidence of disease | |||||

| *Neuroendocrine tumors excluded | |||||

TABLE 3

Site recurrence by size and LVSI*

| UTERUS | PELVIS | DISTANT | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size | ||||

| ≤2 cm (n=125) | 0 | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (0.8%) | 2 (1.6%) |

| >2 cm (n=19) | 0 | 2 (10.5%) | 0 | 2 (10.5%) |

| LVSI | ||||

| No (n=92) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Yes (n=36) | 0 | 3 (8.3%) | 1 (2.8%) | 4 (11.1%) |

| LVSI=lymph-vascular space involvement | ||||

| *Neuroendocrine tumors excluded | ||||

Reproductive outcome

Most researchers have reported that the majority of women attempting to conceive have been successful, and that most pregnancies result in a live birth (Table 4). The rate of second-trimester loss is clearly elevated in women who have undergone radical vaginal trachelectomy. The likely reason: the development of subclinical chorioamnionitis due to an inadequate mucus plug and exposure of the membranes to vaginal flora. To combat this problem, Dargent began performing the Saling procedure at 14 weeks’ gestation.2 This entails approximating the vaginal mucosa over the cervix to provide a barrier to ascending infections. Since performing this technique, Dargent has not observed any cases of second-trimester loss. To date, this technique has not been adopted by other medical centers.

TABLE 4

Reproductive outcome

| LYON N=71 | QUEBEC N=43 | TORONTO N=53 | LOS ANGELES N=20 | LONDON N=9 | TOTAL N=196 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. pregnancies | 44 (27)† | 15 (11) | 9 (7)† | 3 (3)† | 7 (4) | 78 |

| Live births | 23 | 8 | 5 | 3‡ | 3 | 42 |

| Neonatal deaths | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| First-trimester loss | 6 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 14 |

| TAB | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Ectopic | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Second-trimester loss | 8 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 12 |

| Pregnancy ongoing | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Numbers in parentheses represent number of women who were able to achieve a pregnancy | ||||||

| *5 pregnancies at the time of RVT | ||||||

| †1 pregnancy at the time of RVT | ||||||

| ‡1 set of twins | ||||||

| TAB=therapeutic abortion | ||||||

Conclusion

Based on the available data, the recurrence rate for women with squamous and adenocarcinomas appears to be low and comparable to that observed in women undergoing radical hysterectomy. Women with lesions larger than 2 cm or whose tumors have invaded the lymph-vascular space have a higher rate of recurrence, though not necessarily higher than if they had undergone radical hysterectomy.8,9

However, this data must be interpreted with caution. The majority of recurrences reported have been located in the pelvis, raising the concern that the parametrial resection at the time of radical trachelectomy may be inadequate. Yet, recurrences after radical hysterectomy also tend to be local rather than distant in non-irradiated patients.9,10 Also, the follow-up for women undergoing radical trachelectomy has been relatively short, and the number of women with lesions larger than 2 cm who have undergone this procedure is small. Thus, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the safety and efficacy of radical vaginal trachelectomy in this group.

Nonetheless, this technique appears to be a reasonable option for women with early-stage cervical cancer who desire future fertility. Among the almost 200 cases reported, the cancer recurrence rate is low, and viable pregnancies are clearly possible. However, longer follow-up is desirable. To meet this need, centers performing the procedure are forming a registry to better track both oncologic and reproductive outcomes. Further, more research is needed as to whether the Saling procedure will improve reproductive outcome and whether women with lesions larger than 2 cm and/or tumors invading the lymph-vascular space are at greater risk of recurrence with radical trachelectomy than if they had undergone radical hysterectomy.

At present, I offer radical vaginal trachelectomy to reproductive-age women with lesions 2 cm or smaller who are extremely desirous of future fertility. If the lesion is larger than 2 cm but is distal so that clearance appears feasible, I inform patients that there is limited data available regarding outcome, especially if LVSI is present.

The author reports no financial relationship with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article.

- Lesions should be smaller than 2 cm to achieve the most favorable outcomes. Masses up to 3 cm can be resected, but the recurrence rate is higher, especially if the tumor has invaded the lymph-vascular space.

- Resect the cervix 0.5 to 1 cm distal to the isthmus. If the proximal incision margin has cleared the cancer, close the peritoneum and suture the vaginal mucosa to the cervical stump.

- The rate of second-trimester loss is elevated as a result of subclinical chorioamnionitis due to exposure of the membranes to vaginal flora. The Saling procedure has been shown to prevent ascending infections.

- The majority of women who have undergone radical vaginal trachelectomy successfully conceive, and most pregnancies result in a live birth.

While the mean age at which cervical cancer is diagnosed is 51, approximately 10% to 15% of women will develop cervical cancer in their reproductive years.1 Traditionally, early-stage cervical cancers in young women have been treated by radical hysterectomy, resulting in permanent sterility. Now, these patients have an alternative: radical vaginal trachelectomy. This entails the excision of the majority of the cervix and parametria, with preservation of the uppermost portion of the cervix and uterus, allowing the possibility of future childbearing (Figure 1).

The rate of second trimester loss is elevated in radical vaginal trachelectomy patients.

A conservative approach for the treatment of early-stage cervical cancer was first proposed approximately 20 years ago by Aburel, a Romanian gynecologist.2 He reported his experience with the abdominal “subfundic radical hysterectomy.” However, subsequent successful pregnancies did not occur, and the procedure was abandoned. In 1987, the French gynecologist Dargent began performing radical vaginal trachelectomy in concert with laparoscopic pelvic lymphadenectomy. He published his initial results in 1994.3 Thereafter, researchers in Quebec,4 Toronto,5 and London6 have reported their experiences with this procedure. Currently, almost 200 cases are reported in the literature. After describing patient selection and the technique, I will review the data regarding complications and oncologic and reproductive outcomes.

Figure 1

The shaded area indicates the portion of the cervix and upper vagina that will be resected during the procedure.

Patient selection

Although the potential benefit—preservation of fertility—is profound, the percentage of patients with cervical cancer who are candidates for radical vaginal trachelectomy is relatively small. The indications are the presence of an invasive cervical cancer (stage Ia2, Ib1, or IIa), the desire for future childbearing, no involvement of the upper endocervical canal, and no evidence of metastases on preoperative chest radiography and physical exam. Lesions 2 cm or smaller are ideal. While masses up to 3 cm can be resected, the recurrence rate is higher (similar to that after radical hysterectomy). Further, the absence of lymph-vascular space involvement (LVSI) is preferred, but its presence is not an absolute contraindication to the surgery.

Technique

Prior to the radical vaginal trachelectomy, perform a pelvic lymphadenectomy either transperitoneally or retroperitoneally, depending on the surgeon’s preference. If immediate histopathologic analysis of the lymph nodes is negative for metastases, proceed with the trachelectomy.

With the patient in the dorsal lithotomy position, grasp the vagina approximately 3 cm from the cervix and inject it with lidocaine. Then, using a scalpel, incise the vagina at the 12 o’clock position. After developing the vaginal cuff, suture it over the tumor using an absorbable suture in a figure-of-eight stitch, which provides traction to help identify proper surgical planes. Using the technique for a vaginal hysterectomy, create the vesicovaginal space. Then grasp the vagina at the 9 o’clock and 11 o’clock positions and sharply develop the paravesical space. Access to this space is located at approximately the 10 o’clock position. Repeat the same procedure on the contralateral side. (In this case, grasp the vagina at the 3 o’clock and 1 o’clock positions; access to this space is located at the 2 o’clock position.)

In the hands of an experienced surgeon, the complication rate is comparable to that of radical hysterectomy.

Place retractors in the paravesical spaces and retract the bladder anteriorly. The bladder pillars, which contain the ureters and are located in between the vesicovaginal and paravesical spaces, are now fully exposed (Figure 2). Palpate the ureter in each bladder pillar, then sharply divide each pillar, using cautery for hemostasis as needed. The ureters are now visible, as are the descending branches of the uterine artery.

At this point, the posterior cul-de-sac and the pararectal spaces can be accessed. Divide the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments 2 cm from the cervix (Figure 3). Retract the ureters and clamp the descending branch of the uterine artery. Finally, resect the cervix 0.5 to 1 cm distal to the isthmus and send the specimen to pathology (Figure 4). If the proximal (deep) incision margin has cleared the cancer, close the peritoneum and place a cerclage using a strong nonabsorbable suture (Figure 5). I prefer a double cerclage of No. 1 polyester or polypropylene. Then suture the vaginal mucosa to the cervical stump, not to the mucosa, to help prevent postoperative stenosis (Figure 6).

Prior to discharge, attempt a bladder challenge (usually postoperative day 2). In the rare instance the woman is unable to void, discharge the patient and repeat the bladder challenge in 1 week.

Figure 2

After dividing the bladder pillar, located between the vesicovaginal and paravesical spaces, identify the ureter (the tubular structure at 12 o’clock).

Figure 3

Access the posterior cul-de-sac and the pararectal spaces, and then divide the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments 2 cm from the cervix.

Figure 4

After retracting the ureters and clamping the descending branch of the uterine artery, resect the cervix 0.5 to 1 cm distal to the isthmus.

Figure 5

If the proximal incision margin has cleared the cancer, close the peritoneum and place a cerclage using a strong nonabsorbable suture.

Figure 6

Finally, suture the vaginal mucosa to the cervical stump, not to the mucosa, to help prevent postoperative stenosis.

Complications

The rate of morbidity associated with this procedure varies from 13% to 25%.3-5 (In the hands of an experienced surgeon, the complication rate is comparable to that of radical hysterectomy.) Dargent et al reported complications in 7 of 47 women (1 required reoperation for sidewall hemorrhage, 5 had postoperative hematomas, and 1 had prolonged urinary retention).3 Similarly, Roy and Plante reported 2 external iliac artery injuries, 1 conversion to laparotomy for hemostasis, and 1 cystotomy among 30 patients who underwent the procedure.4 Covens et al encountered complications in 8 of 32 women, including 6 cystotomies, 1 enterotomy, and 1 external iliac artery injury.5 It is important to note that the vascular injuries most commonly occurred during the lymphadenectomy. To date, no operative mortalities have been reported in association with radical trachelectomy.

Oncologic outcome

Roy recently summarized the oncologic outcome of women undergoing radical vaginal trachelectomy for early-stage cervical cancer at medical centers in Lyon, Quebec, and Toronto.7 This data, as well as that from London and the Women’s Hospital in Los Angeles, are shown in Table 1. (Women who underwent radical trachelectomy followed by hysterectomy due to lack of lesion clearance are excluded.)

Among the almost 200 cases, the cancer recurrence rate is low, and viable pregnancies are clearly possible.

Seven of 197 women (3.5%) had positive lymph nodes discovered postoperatively. However, all of them have remained disease-free. (Most of the women received pelvic radiotherapy postoperatively.) To date, there have been 6 recurrences (3%) reported, 2 of which have been in women with neuroendocrine tumors (a histology associated with an especially poor prognosis). Excluding the 2 neuroendocrine tumors, the recurrence rate drops to 2.1%. All of the 4 remaining women had negative lymph nodes and LVSI, and 2 had lesions larger than 2 cm (Table 2).

Of the 92 women whose cervical cancers did not invade the lymph-vascular space, none experienced a recurrence. Similarly, smaller tumors were associated with a low recurrence rate; in women with lesions 2 cm or smaller, only 1.6% had a recurrence. Women with lesions larger than 2 cm or with LVSI had a somewhat higher recurrence rate (10.5% and 11.1%, respectively), as would be expected based on our knowledge of recurrence risk after radical hysterectomy (Table 3).8,9

There are no prospective randomized trials that have analyzed oncologic outcome in women undergoing radical vaginal trachelectomy as compared to radical hysterectomy. Clearly, such a trial would not be feasible. However, the results of a 1999 retrospective case-control study are promising. In this trial, Covens compared the outcome of 32 women who underwent radical vaginal trachelectomy (all of whom had negative nodes and none of whom received radiation) to that of 30 women who underwent radical hystererctomy (matched for age, tumor size, histology, depth of invasion, and presence of LVSI).5 A second, unmatched, control group consisted of all women who had undergone radical hysterectomy for tumors 2 cm or smaller, had negative nodes, and had not received postoperative pelvic radiation. After a median follow-up of 23.4 months for the study patients, 46.5 months for the matched control patients, and 50.3 months for the unmatched control group, the 2-year actuarial recurrence-free survival was 95%, 97%, and 100%, respectively. These differences were not statistically significant.

TABLE 1

Oncologic outcome

| LYON N=71 | QUEBEC N=43 | TORONTO N=53 | LOSANGELES N=20 | LONDON N=9 | TOTAL N=196 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up (mean) | 60 | 36 | 30 | 18.5 | 2 | - |

| Positive nodes | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 7 (3.5%) |

| Recurrence | 3* | 2* | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6† (3%) |

| *One patient in each had a neuroendocrine tumor | ||||||

| †Recurrence rate is 2.1%, if women with neuroendocrine tumors are excluded. | ||||||

TABLE 2

Recurrences after radical vaginal trachelectomy*

| SIZE | HISTOLOGY | LN STATUS | LVSI | SITE | STATUS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 cm | Adenocarcinoma | Negative | Yes | Aortic LN | DOD |

| 2.5 cm | Squamous | Negative | Yes | Pelvic LN | NED |

| 3 cm | Squamous | Negative | Yes | Pelvis | DOD |

| <2 cm | Adenocarcinoma | Negative | Yes | Pelvis | DOD |

| LN=lymph node | |||||

| LVSI=lymph-vascular space involvement | |||||

| DOD=dead of disease | |||||

| NED=no evidence of disease | |||||

| *Neuroendocrine tumors excluded | |||||

TABLE 3

Site recurrence by size and LVSI*

| UTERUS | PELVIS | DISTANT | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size | ||||

| ≤2 cm (n=125) | 0 | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (0.8%) | 2 (1.6%) |

| >2 cm (n=19) | 0 | 2 (10.5%) | 0 | 2 (10.5%) |

| LVSI | ||||

| No (n=92) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Yes (n=36) | 0 | 3 (8.3%) | 1 (2.8%) | 4 (11.1%) |

| LVSI=lymph-vascular space involvement | ||||

| *Neuroendocrine tumors excluded | ||||

Reproductive outcome

Most researchers have reported that the majority of women attempting to conceive have been successful, and that most pregnancies result in a live birth (Table 4). The rate of second-trimester loss is clearly elevated in women who have undergone radical vaginal trachelectomy. The likely reason: the development of subclinical chorioamnionitis due to an inadequate mucus plug and exposure of the membranes to vaginal flora. To combat this problem, Dargent began performing the Saling procedure at 14 weeks’ gestation.2 This entails approximating the vaginal mucosa over the cervix to provide a barrier to ascending infections. Since performing this technique, Dargent has not observed any cases of second-trimester loss. To date, this technique has not been adopted by other medical centers.

TABLE 4

Reproductive outcome

| LYON N=71 | QUEBEC N=43 | TORONTO N=53 | LOS ANGELES N=20 | LONDON N=9 | TOTAL N=196 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. pregnancies | 44 (27)† | 15 (11) | 9 (7)† | 3 (3)† | 7 (4) | 78 |

| Live births | 23 | 8 | 5 | 3‡ | 3 | 42 |

| Neonatal deaths | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| First-trimester loss | 6 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 14 |

| TAB | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Ectopic | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Second-trimester loss | 8 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 12 |

| Pregnancy ongoing | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Numbers in parentheses represent number of women who were able to achieve a pregnancy | ||||||

| *5 pregnancies at the time of RVT | ||||||

| †1 pregnancy at the time of RVT | ||||||

| ‡1 set of twins | ||||||

| TAB=therapeutic abortion | ||||||

Conclusion

Based on the available data, the recurrence rate for women with squamous and adenocarcinomas appears to be low and comparable to that observed in women undergoing radical hysterectomy. Women with lesions larger than 2 cm or whose tumors have invaded the lymph-vascular space have a higher rate of recurrence, though not necessarily higher than if they had undergone radical hysterectomy.8,9

However, this data must be interpreted with caution. The majority of recurrences reported have been located in the pelvis, raising the concern that the parametrial resection at the time of radical trachelectomy may be inadequate. Yet, recurrences after radical hysterectomy also tend to be local rather than distant in non-irradiated patients.9,10 Also, the follow-up for women undergoing radical trachelectomy has been relatively short, and the number of women with lesions larger than 2 cm who have undergone this procedure is small. Thus, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the safety and efficacy of radical vaginal trachelectomy in this group.

Nonetheless, this technique appears to be a reasonable option for women with early-stage cervical cancer who desire future fertility. Among the almost 200 cases reported, the cancer recurrence rate is low, and viable pregnancies are clearly possible. However, longer follow-up is desirable. To meet this need, centers performing the procedure are forming a registry to better track both oncologic and reproductive outcomes. Further, more research is needed as to whether the Saling procedure will improve reproductive outcome and whether women with lesions larger than 2 cm and/or tumors invading the lymph-vascular space are at greater risk of recurrence with radical trachelectomy than if they had undergone radical hysterectomy.

At present, I offer radical vaginal trachelectomy to reproductive-age women with lesions 2 cm or smaller who are extremely desirous of future fertility. If the lesion is larger than 2 cm but is distal so that clearance appears feasible, I inform patients that there is limited data available regarding outcome, especially if LVSI is present.

The author reports no financial relationship with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article.

1. Van der Vange N, Woverling G, Ketting B, et al. The prognosis of cervical cancer associated with pregnancy: a matched cohort study. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:1022-1026.

2. Aburel E. Colpohistorectomia largita subfundica. In: Sirbu P, ed. Chirurgica Gynecologica. Bucharest, Romania: Editura Medicala Pub; 1981;714-721.

3. Dargent D, Martin X, Sacchetoni A, Mathevet P. Laparoscopic vaginal radical trachelectomy. Cancer. 2000;88:1877-1882.

4. Roy M, Plante M. Pregnancies after radical vaginal trachelectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1491-1496.

5. Covens A, Shaw P, Murphy J, DePetrillo D, Lickrish G, LaFramboise S, Rosen B. Is radical trachelectomy a safe alternative to radical hysterectomy for patients with stage IA-B carcinoma of the cervix? Cancer. 1999;86:2273-2279.

6. Shepherd JH, Crawford RAF, Oram DH. Radical trachelectomy: a way to preserve fertility in the treatment of early cervical cancer. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:912-916.

7. Roy M. Vaginal radical trachelectomy in early-stage cervical cancer. Presented at: Advanced Laparoscopic and Vaginal Surgery in Gynecologic Oncology; June 5-6, 2000; University of Southern California, Los Angeles, Calif,

8. Delgado G, Bundy B, Zaino R, Bernd-Uwe S, Creasman WT, Major F. Prospective surgical-pathological study of diseasefree interval in patients with stage IB squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 1990;38:352-357.

9. Hopkins MP, Morley GW. Radical hysterectomy versus radiation therapy for stage IB squamous cell cancer of the cervix. Cancer. 1991;68:272-277.

10. Sedlis A, Bundy BN, Rotman MZ, Lentz SS, Muderspach LI, Zaino RJ. A randomized trial of pelvic radiation therapy versus no further therapy in selected patients with stage IB carcinoma of the cervix after radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;73:177-183.

1. Van der Vange N, Woverling G, Ketting B, et al. The prognosis of cervical cancer associated with pregnancy: a matched cohort study. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:1022-1026.

2. Aburel E. Colpohistorectomia largita subfundica. In: Sirbu P, ed. Chirurgica Gynecologica. Bucharest, Romania: Editura Medicala Pub; 1981;714-721.

3. Dargent D, Martin X, Sacchetoni A, Mathevet P. Laparoscopic vaginal radical trachelectomy. Cancer. 2000;88:1877-1882.

4. Roy M, Plante M. Pregnancies after radical vaginal trachelectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1491-1496.

5. Covens A, Shaw P, Murphy J, DePetrillo D, Lickrish G, LaFramboise S, Rosen B. Is radical trachelectomy a safe alternative to radical hysterectomy for patients with stage IA-B carcinoma of the cervix? Cancer. 1999;86:2273-2279.

6. Shepherd JH, Crawford RAF, Oram DH. Radical trachelectomy: a way to preserve fertility in the treatment of early cervical cancer. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:912-916.

7. Roy M. Vaginal radical trachelectomy in early-stage cervical cancer. Presented at: Advanced Laparoscopic and Vaginal Surgery in Gynecologic Oncology; June 5-6, 2000; University of Southern California, Los Angeles, Calif,

8. Delgado G, Bundy B, Zaino R, Bernd-Uwe S, Creasman WT, Major F. Prospective surgical-pathological study of diseasefree interval in patients with stage IB squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 1990;38:352-357.

9. Hopkins MP, Morley GW. Radical hysterectomy versus radiation therapy for stage IB squamous cell cancer of the cervix. Cancer. 1991;68:272-277.

10. Sedlis A, Bundy BN, Rotman MZ, Lentz SS, Muderspach LI, Zaino RJ. A randomized trial of pelvic radiation therapy versus no further therapy in selected patients with stage IB carcinoma of the cervix after radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;73:177-183.