User login

When to not go with your gut: Modern approaches to abdominal wall pain

Abdominal pain is a commonly seen presenting concern in gastroenterology clinics. Establishing a diagnosis effectively and efficiently can be challenging given the broad differential. Abdominal wall pain is an often-overlooked diagnosis but accounts for up to 30% of cases of chronic abdominal pain1 and up to 10% of patients with chronic idiopathic abdominal pain seen in gastroenterology practices.2 Trigger point injection in the office can be both diagnostic and therapeutic.

The prevalence of chronic abdominal wall pain is highest in the fifth and sixth decades, and it is four times more likely to occur in women than in men. Common comorbid conditions include obesity, gastroesophageal reflux disease, irritable bowel syndrome, and fibromyalgia.3 Abdominal wall pain is often sharp or burning due to somatic innervation of the abdominal wall supplied by the anterior branches of thoracic intercostal nerves (T7 to T11). Abdominal wall pain may originate from entrapment of these nerves.2 Potential causes of entrapment include disruption of insulating fat, localized edema and distension, and scar tissue or fibrosis from prior surgical procedures.3 Symptoms are typically exacerbated with any actions or activities that engage the abdominal wall such as twisting or turning, and pain often improves with rest.

The classic physical exam finding for abdominal wall pain is a positive Carnett sign. This is determined via palpation of the point of maximal tenderness. First, this is done with a single finger while the patient’s abdominal wall is relaxed. The same point is then palpated again while the patient engages their abdominal muscles, most commonly while the patient to performs a “sit up” or lifts their legs off the exam table. Exacerbation of pain with these maneuvers indicates a positive test and suggests the abdominal wall as the underlying etiology.

While performing the maneuver for determining Carnett sign is a simple test in the traditional office visit, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a burgeoning proportion of telehealth visits, limiting the physician’s ability to perform a direct physical exam. Fortunately, the maneuvers required when testing for Carnett sign are simple enough that a clinician can guide a patient step-by-step on how to perform the test. Ideally, if a family member or friend is available to serve as the clinician’s hands, the test can be performed with ease while directly visualizing proper technique. Sample videos of how the test is performed are readily available on the Internet for patients to view (the authors suggest screening the video yourself before providing a link to patients). The sensitivity and specificity of Carnett sign are very high (>70%) and even better when there is no apparent hernia.1

Management

Trigger point injections with local anesthetic can be both diagnostic and therapeutic in patients with abdominal wall pain. An immediate reduction of pain by at least 50% with injection at the site of maximal tenderness strongly supports the diagnosis of abdominal wall pain.1 Patients should first be thoroughly counseled on potential side effects of local corticosteroid injection to include risk of infection, bleeding, pain, skin hypopigmentation, or thinning and fat atrophy. Repeat injections are rarely needed, and any additional injection should be performed after at least 3 months. Additional adjunct therapies include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, topical therapies such as lidocaine, and neuroleptic agents such as gabapentin.4 One previously described trigger point injection technique, involves a mix of triamcinolone and lidocaine injected at the point of maximal tenderness.5 This technique is easy to perform in clinic and has minimal risks.

Conclusion

Abdominal wall pain is a common, yet often-overlooked, condition that can be diagnosed with a good clinical history and physical exam. A simple in-office trigger point injection can confirm the diagnosis and offer durable relief for most patients. A shift to virtual medicine does not need to a barrier to diagnosis, particularly in the attentive patient.

Dr. Park is a fellow in the gastroenterology service in the Department of Internal Medicine at Naval Medical Center San Diego and an assistant professor in the department of medicine of the Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, Md. Dr. Singla is a gastroenterologist at Capital Digestive Care in Silver Spring, Md., and an associate professor in the department of medicine at the Uniformed Services University. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Glissen Brown JR et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50(10):828-35.

2. Srinivasan R, Greenbaum DS. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(4):824-30.

3. Kambox AK et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(1):139-44.

4. Scheltinga MR, Roumen RM. Hernia. 2018;22(3):507-16.

5. Singla M, Laczek JT. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020 May;115(5):645-7.

Abdominal pain is a commonly seen presenting concern in gastroenterology clinics. Establishing a diagnosis effectively and efficiently can be challenging given the broad differential. Abdominal wall pain is an often-overlooked diagnosis but accounts for up to 30% of cases of chronic abdominal pain1 and up to 10% of patients with chronic idiopathic abdominal pain seen in gastroenterology practices.2 Trigger point injection in the office can be both diagnostic and therapeutic.

The prevalence of chronic abdominal wall pain is highest in the fifth and sixth decades, and it is four times more likely to occur in women than in men. Common comorbid conditions include obesity, gastroesophageal reflux disease, irritable bowel syndrome, and fibromyalgia.3 Abdominal wall pain is often sharp or burning due to somatic innervation of the abdominal wall supplied by the anterior branches of thoracic intercostal nerves (T7 to T11). Abdominal wall pain may originate from entrapment of these nerves.2 Potential causes of entrapment include disruption of insulating fat, localized edema and distension, and scar tissue or fibrosis from prior surgical procedures.3 Symptoms are typically exacerbated with any actions or activities that engage the abdominal wall such as twisting or turning, and pain often improves with rest.

The classic physical exam finding for abdominal wall pain is a positive Carnett sign. This is determined via palpation of the point of maximal tenderness. First, this is done with a single finger while the patient’s abdominal wall is relaxed. The same point is then palpated again while the patient engages their abdominal muscles, most commonly while the patient to performs a “sit up” or lifts their legs off the exam table. Exacerbation of pain with these maneuvers indicates a positive test and suggests the abdominal wall as the underlying etiology.

While performing the maneuver for determining Carnett sign is a simple test in the traditional office visit, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a burgeoning proportion of telehealth visits, limiting the physician’s ability to perform a direct physical exam. Fortunately, the maneuvers required when testing for Carnett sign are simple enough that a clinician can guide a patient step-by-step on how to perform the test. Ideally, if a family member or friend is available to serve as the clinician’s hands, the test can be performed with ease while directly visualizing proper technique. Sample videos of how the test is performed are readily available on the Internet for patients to view (the authors suggest screening the video yourself before providing a link to patients). The sensitivity and specificity of Carnett sign are very high (>70%) and even better when there is no apparent hernia.1

Management

Trigger point injections with local anesthetic can be both diagnostic and therapeutic in patients with abdominal wall pain. An immediate reduction of pain by at least 50% with injection at the site of maximal tenderness strongly supports the diagnosis of abdominal wall pain.1 Patients should first be thoroughly counseled on potential side effects of local corticosteroid injection to include risk of infection, bleeding, pain, skin hypopigmentation, or thinning and fat atrophy. Repeat injections are rarely needed, and any additional injection should be performed after at least 3 months. Additional adjunct therapies include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, topical therapies such as lidocaine, and neuroleptic agents such as gabapentin.4 One previously described trigger point injection technique, involves a mix of triamcinolone and lidocaine injected at the point of maximal tenderness.5 This technique is easy to perform in clinic and has minimal risks.

Conclusion

Abdominal wall pain is a common, yet often-overlooked, condition that can be diagnosed with a good clinical history and physical exam. A simple in-office trigger point injection can confirm the diagnosis and offer durable relief for most patients. A shift to virtual medicine does not need to a barrier to diagnosis, particularly in the attentive patient.

Dr. Park is a fellow in the gastroenterology service in the Department of Internal Medicine at Naval Medical Center San Diego and an assistant professor in the department of medicine of the Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, Md. Dr. Singla is a gastroenterologist at Capital Digestive Care in Silver Spring, Md., and an associate professor in the department of medicine at the Uniformed Services University. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Glissen Brown JR et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50(10):828-35.

2. Srinivasan R, Greenbaum DS. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(4):824-30.

3. Kambox AK et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(1):139-44.

4. Scheltinga MR, Roumen RM. Hernia. 2018;22(3):507-16.

5. Singla M, Laczek JT. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020 May;115(5):645-7.

Abdominal pain is a commonly seen presenting concern in gastroenterology clinics. Establishing a diagnosis effectively and efficiently can be challenging given the broad differential. Abdominal wall pain is an often-overlooked diagnosis but accounts for up to 30% of cases of chronic abdominal pain1 and up to 10% of patients with chronic idiopathic abdominal pain seen in gastroenterology practices.2 Trigger point injection in the office can be both diagnostic and therapeutic.

The prevalence of chronic abdominal wall pain is highest in the fifth and sixth decades, and it is four times more likely to occur in women than in men. Common comorbid conditions include obesity, gastroesophageal reflux disease, irritable bowel syndrome, and fibromyalgia.3 Abdominal wall pain is often sharp or burning due to somatic innervation of the abdominal wall supplied by the anterior branches of thoracic intercostal nerves (T7 to T11). Abdominal wall pain may originate from entrapment of these nerves.2 Potential causes of entrapment include disruption of insulating fat, localized edema and distension, and scar tissue or fibrosis from prior surgical procedures.3 Symptoms are typically exacerbated with any actions or activities that engage the abdominal wall such as twisting or turning, and pain often improves with rest.

The classic physical exam finding for abdominal wall pain is a positive Carnett sign. This is determined via palpation of the point of maximal tenderness. First, this is done with a single finger while the patient’s abdominal wall is relaxed. The same point is then palpated again while the patient engages their abdominal muscles, most commonly while the patient to performs a “sit up” or lifts their legs off the exam table. Exacerbation of pain with these maneuvers indicates a positive test and suggests the abdominal wall as the underlying etiology.

While performing the maneuver for determining Carnett sign is a simple test in the traditional office visit, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a burgeoning proportion of telehealth visits, limiting the physician’s ability to perform a direct physical exam. Fortunately, the maneuvers required when testing for Carnett sign are simple enough that a clinician can guide a patient step-by-step on how to perform the test. Ideally, if a family member or friend is available to serve as the clinician’s hands, the test can be performed with ease while directly visualizing proper technique. Sample videos of how the test is performed are readily available on the Internet for patients to view (the authors suggest screening the video yourself before providing a link to patients). The sensitivity and specificity of Carnett sign are very high (>70%) and even better when there is no apparent hernia.1

Management

Trigger point injections with local anesthetic can be both diagnostic and therapeutic in patients with abdominal wall pain. An immediate reduction of pain by at least 50% with injection at the site of maximal tenderness strongly supports the diagnosis of abdominal wall pain.1 Patients should first be thoroughly counseled on potential side effects of local corticosteroid injection to include risk of infection, bleeding, pain, skin hypopigmentation, or thinning and fat atrophy. Repeat injections are rarely needed, and any additional injection should be performed after at least 3 months. Additional adjunct therapies include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, topical therapies such as lidocaine, and neuroleptic agents such as gabapentin.4 One previously described trigger point injection technique, involves a mix of triamcinolone and lidocaine injected at the point of maximal tenderness.5 This technique is easy to perform in clinic and has minimal risks.

Conclusion

Abdominal wall pain is a common, yet often-overlooked, condition that can be diagnosed with a good clinical history and physical exam. A simple in-office trigger point injection can confirm the diagnosis and offer durable relief for most patients. A shift to virtual medicine does not need to a barrier to diagnosis, particularly in the attentive patient.

Dr. Park is a fellow in the gastroenterology service in the Department of Internal Medicine at Naval Medical Center San Diego and an assistant professor in the department of medicine of the Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, Md. Dr. Singla is a gastroenterologist at Capital Digestive Care in Silver Spring, Md., and an associate professor in the department of medicine at the Uniformed Services University. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Glissen Brown JR et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50(10):828-35.

2. Srinivasan R, Greenbaum DS. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(4):824-30.

3. Kambox AK et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(1):139-44.

4. Scheltinga MR, Roumen RM. Hernia. 2018;22(3):507-16.

5. Singla M, Laczek JT. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020 May;115(5):645-7.

Fellowship Burnout: What can we do to identify those at risk and minimize the impact?

Jeff is a high-performing first-year gastroenterology fellow who started with eagerness and enthusiasm. He seemed to enjoy talking to patients, wrote thorough notes, and often participated during case discussions at morning report. He initiated a quality improvement project and joined a hospital committee. Over the past few months, he has interacted less with his peers in the fellow’s office and stayed late to complete his patient encounters. He now frequently arrives late to work, is unprepared for rounds, and forgets to place important orders. One day, you notice him shuffling through several papers when the attending asks him a question about his patient. Later that day, he snapped at a nurse who paged to ask a question about a patient who just had a colonoscopy. When you ask him how he is doing, he becomes tearful and reports that he is under a lot of stress between work and home and does not feel the work he is doing is meaningful.

Introduction

The above scenario is all too familiar. Gastroenterology training can be a stressful period in an individual’s life. Long hours, steep learning curves for new cognitive and mechanical skill sets, as well as managing personal relationships and responsibilities at home all contribute to the stress of training and finding appropriate work-life balance. These stressors can result in burnout. The last decade has brought about a renewed emphasis on mitigating the impact of occupational burnout and improving trainee lifestyle through interventions such as work-hour restrictions, resiliency training, instruction on the importance of sleep, and team-building activities.

The problem

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines occupational burnout as chronic work-related stress, which may be characterized by feelings of energy depletion, mental distance from one’s job or feelings of negativity toward it, and reduced professional efficacy. Occupational burnout has been identified as an increasing problem both in practicing providers and trainees. Surveys in gastroenterologists show rates of burnout ranging between 37% and 50%,1 with trainees and early-career physicians disproportionately affected.1,2Physicians along the entire training spectrum are more likely to report high emotional exhaustion, high depersonalization, and burnout than a population control sample.2

Several individual factors identified for those at increased risk for burnout include younger age, not being married, and being male.2 Individuals spending less than 20% of their time working on activities they find meaningful and productive were more likely to show evidence of burnout.1

Symptoms of burnout can have a profound impact on trainees’ work performance, personal interactions, and the learning environment as a whole. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) annual survey of trainees asks them how strongly they agree or disagree on various components of burnout such as how meaningful they find their work, if they have enough time to think and reflect, if they feel emotionally drained at work, and if they feel worn out and weary after work. The intent of these questions is to provide anonymous feedback to training programs to help identify year to year trends and intervene early to prevent occupational burnout from becoming an increasing issue.

The solution

Considerations for any intervention should take several factors into account: the impact it may have on training and the development of a competent physician in their individualized specialty, the sustainability of the intervention, and whether it is something that will be accepted by the invested parties.

One method proposed for preventing burnout during fellowship has been designated as the three R’s: relaxation, reflection, and regrouping.3

- Relax. In order to relax, trainees need ways to decompress. Activities such as exercise and social events can be helpful. Within our own program the fellows have started their own group exercise program, playing wallyball weekly before clinical duties. We also encourage use of vacation days and build comradery by organizing potluck dinners for major holidays, graduation parties at the program director’s house, and an end-of-the-year golf outing in which trainees play against staff followed by a discussion regarding the state of the program. More recently we have added one half-day per a quarter for morale and team building. During this first year, the activities in which trainees have collectively decided to participate include an escape room, a rock-climbing facility, and laser tag. The addition of more team-building days has been well received by our program’s trainees and the simple addition of these team-building days has resulted in the trainees interacting more together outside of work, particularly in the form of group dinners.

Walter Reed National Military Medical Center fellows gathering for wallyball. - Reflect. They describe reflection as a necessary checkpoint which typically occurs every 6 months.3 These “checkpoints” provide an opportunity to provide feedback to the fellow as well as check in on their well-being and receive feedback about the program. We give frequent feedback to fellows in the form of spot, rotational, and mid-/end-of-year feedback. Additionally, we have developed a unique feedback system in which the trainees meet at the end of the year to discuss collective feedback for the staff and the program. This feedback is collated by the chief fellow and given to the program director as anonymous feedback, which is then passed to the individual staff.

- Regroup. Finally, regrouping to form new strategies.3 This regrouping provides an opportunity to improve on areas in which the trainee may have a deficiency and build on their strengths. To facilitate regrouping, we identify a mentor within the department and occasionally in other departments to meet regularly with the trainee. A successful mentor ensures effective regrouping and can help the trainee avoid pitfalls that they may have experienced in similar situations.

Moving forward

Occupational burnout is a systemic problem within the medical field, with trainees disproportionately affected. It is imperative that training programs continue to work toward creating a culture that prevents development of burnout. Along with the ideas presented here, the ACGME has launched AWARE, which is a suite of resources directed specifically at the GME community, with a goal of mitigating stress and preventing burnout. No one approach will be universally applicable but continued awareness and efforts to address this on an individual and programmatic level should be encouraged.

Dr. Ordway is a chief fellow, Dr. Tritsch and Dr. Singla are associate program directors, and Dr. Torres the program director, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md.

References

1. Barnes EL et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(2):302-6.

2. Dyrbye LN et al. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443-51.

3. Waldo OA. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(11):1303-6.

Jeff is a high-performing first-year gastroenterology fellow who started with eagerness and enthusiasm. He seemed to enjoy talking to patients, wrote thorough notes, and often participated during case discussions at morning report. He initiated a quality improvement project and joined a hospital committee. Over the past few months, he has interacted less with his peers in the fellow’s office and stayed late to complete his patient encounters. He now frequently arrives late to work, is unprepared for rounds, and forgets to place important orders. One day, you notice him shuffling through several papers when the attending asks him a question about his patient. Later that day, he snapped at a nurse who paged to ask a question about a patient who just had a colonoscopy. When you ask him how he is doing, he becomes tearful and reports that he is under a lot of stress between work and home and does not feel the work he is doing is meaningful.

Introduction

The above scenario is all too familiar. Gastroenterology training can be a stressful period in an individual’s life. Long hours, steep learning curves for new cognitive and mechanical skill sets, as well as managing personal relationships and responsibilities at home all contribute to the stress of training and finding appropriate work-life balance. These stressors can result in burnout. The last decade has brought about a renewed emphasis on mitigating the impact of occupational burnout and improving trainee lifestyle through interventions such as work-hour restrictions, resiliency training, instruction on the importance of sleep, and team-building activities.

The problem

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines occupational burnout as chronic work-related stress, which may be characterized by feelings of energy depletion, mental distance from one’s job or feelings of negativity toward it, and reduced professional efficacy. Occupational burnout has been identified as an increasing problem both in practicing providers and trainees. Surveys in gastroenterologists show rates of burnout ranging between 37% and 50%,1 with trainees and early-career physicians disproportionately affected.1,2Physicians along the entire training spectrum are more likely to report high emotional exhaustion, high depersonalization, and burnout than a population control sample.2

Several individual factors identified for those at increased risk for burnout include younger age, not being married, and being male.2 Individuals spending less than 20% of their time working on activities they find meaningful and productive were more likely to show evidence of burnout.1

Symptoms of burnout can have a profound impact on trainees’ work performance, personal interactions, and the learning environment as a whole. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) annual survey of trainees asks them how strongly they agree or disagree on various components of burnout such as how meaningful they find their work, if they have enough time to think and reflect, if they feel emotionally drained at work, and if they feel worn out and weary after work. The intent of these questions is to provide anonymous feedback to training programs to help identify year to year trends and intervene early to prevent occupational burnout from becoming an increasing issue.

The solution

Considerations for any intervention should take several factors into account: the impact it may have on training and the development of a competent physician in their individualized specialty, the sustainability of the intervention, and whether it is something that will be accepted by the invested parties.

One method proposed for preventing burnout during fellowship has been designated as the three R’s: relaxation, reflection, and regrouping.3

- Relax. In order to relax, trainees need ways to decompress. Activities such as exercise and social events can be helpful. Within our own program the fellows have started their own group exercise program, playing wallyball weekly before clinical duties. We also encourage use of vacation days and build comradery by organizing potluck dinners for major holidays, graduation parties at the program director’s house, and an end-of-the-year golf outing in which trainees play against staff followed by a discussion regarding the state of the program. More recently we have added one half-day per a quarter for morale and team building. During this first year, the activities in which trainees have collectively decided to participate include an escape room, a rock-climbing facility, and laser tag. The addition of more team-building days has been well received by our program’s trainees and the simple addition of these team-building days has resulted in the trainees interacting more together outside of work, particularly in the form of group dinners.

Walter Reed National Military Medical Center fellows gathering for wallyball. - Reflect. They describe reflection as a necessary checkpoint which typically occurs every 6 months.3 These “checkpoints” provide an opportunity to provide feedback to the fellow as well as check in on their well-being and receive feedback about the program. We give frequent feedback to fellows in the form of spot, rotational, and mid-/end-of-year feedback. Additionally, we have developed a unique feedback system in which the trainees meet at the end of the year to discuss collective feedback for the staff and the program. This feedback is collated by the chief fellow and given to the program director as anonymous feedback, which is then passed to the individual staff.

- Regroup. Finally, regrouping to form new strategies.3 This regrouping provides an opportunity to improve on areas in which the trainee may have a deficiency and build on their strengths. To facilitate regrouping, we identify a mentor within the department and occasionally in other departments to meet regularly with the trainee. A successful mentor ensures effective regrouping and can help the trainee avoid pitfalls that they may have experienced in similar situations.

Moving forward

Occupational burnout is a systemic problem within the medical field, with trainees disproportionately affected. It is imperative that training programs continue to work toward creating a culture that prevents development of burnout. Along with the ideas presented here, the ACGME has launched AWARE, which is a suite of resources directed specifically at the GME community, with a goal of mitigating stress and preventing burnout. No one approach will be universally applicable but continued awareness and efforts to address this on an individual and programmatic level should be encouraged.

Dr. Ordway is a chief fellow, Dr. Tritsch and Dr. Singla are associate program directors, and Dr. Torres the program director, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md.

References

1. Barnes EL et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(2):302-6.

2. Dyrbye LN et al. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443-51.

3. Waldo OA. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(11):1303-6.

Jeff is a high-performing first-year gastroenterology fellow who started with eagerness and enthusiasm. He seemed to enjoy talking to patients, wrote thorough notes, and often participated during case discussions at morning report. He initiated a quality improvement project and joined a hospital committee. Over the past few months, he has interacted less with his peers in the fellow’s office and stayed late to complete his patient encounters. He now frequently arrives late to work, is unprepared for rounds, and forgets to place important orders. One day, you notice him shuffling through several papers when the attending asks him a question about his patient. Later that day, he snapped at a nurse who paged to ask a question about a patient who just had a colonoscopy. When you ask him how he is doing, he becomes tearful and reports that he is under a lot of stress between work and home and does not feel the work he is doing is meaningful.

Introduction

The above scenario is all too familiar. Gastroenterology training can be a stressful period in an individual’s life. Long hours, steep learning curves for new cognitive and mechanical skill sets, as well as managing personal relationships and responsibilities at home all contribute to the stress of training and finding appropriate work-life balance. These stressors can result in burnout. The last decade has brought about a renewed emphasis on mitigating the impact of occupational burnout and improving trainee lifestyle through interventions such as work-hour restrictions, resiliency training, instruction on the importance of sleep, and team-building activities.

The problem

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines occupational burnout as chronic work-related stress, which may be characterized by feelings of energy depletion, mental distance from one’s job or feelings of negativity toward it, and reduced professional efficacy. Occupational burnout has been identified as an increasing problem both in practicing providers and trainees. Surveys in gastroenterologists show rates of burnout ranging between 37% and 50%,1 with trainees and early-career physicians disproportionately affected.1,2Physicians along the entire training spectrum are more likely to report high emotional exhaustion, high depersonalization, and burnout than a population control sample.2

Several individual factors identified for those at increased risk for burnout include younger age, not being married, and being male.2 Individuals spending less than 20% of their time working on activities they find meaningful and productive were more likely to show evidence of burnout.1

Symptoms of burnout can have a profound impact on trainees’ work performance, personal interactions, and the learning environment as a whole. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) annual survey of trainees asks them how strongly they agree or disagree on various components of burnout such as how meaningful they find their work, if they have enough time to think and reflect, if they feel emotionally drained at work, and if they feel worn out and weary after work. The intent of these questions is to provide anonymous feedback to training programs to help identify year to year trends and intervene early to prevent occupational burnout from becoming an increasing issue.

The solution

Considerations for any intervention should take several factors into account: the impact it may have on training and the development of a competent physician in their individualized specialty, the sustainability of the intervention, and whether it is something that will be accepted by the invested parties.

One method proposed for preventing burnout during fellowship has been designated as the three R’s: relaxation, reflection, and regrouping.3

- Relax. In order to relax, trainees need ways to decompress. Activities such as exercise and social events can be helpful. Within our own program the fellows have started their own group exercise program, playing wallyball weekly before clinical duties. We also encourage use of vacation days and build comradery by organizing potluck dinners for major holidays, graduation parties at the program director’s house, and an end-of-the-year golf outing in which trainees play against staff followed by a discussion regarding the state of the program. More recently we have added one half-day per a quarter for morale and team building. During this first year, the activities in which trainees have collectively decided to participate include an escape room, a rock-climbing facility, and laser tag. The addition of more team-building days has been well received by our program’s trainees and the simple addition of these team-building days has resulted in the trainees interacting more together outside of work, particularly in the form of group dinners.

Walter Reed National Military Medical Center fellows gathering for wallyball. - Reflect. They describe reflection as a necessary checkpoint which typically occurs every 6 months.3 These “checkpoints” provide an opportunity to provide feedback to the fellow as well as check in on their well-being and receive feedback about the program. We give frequent feedback to fellows in the form of spot, rotational, and mid-/end-of-year feedback. Additionally, we have developed a unique feedback system in which the trainees meet at the end of the year to discuss collective feedback for the staff and the program. This feedback is collated by the chief fellow and given to the program director as anonymous feedback, which is then passed to the individual staff.

- Regroup. Finally, regrouping to form new strategies.3 This regrouping provides an opportunity to improve on areas in which the trainee may have a deficiency and build on their strengths. To facilitate regrouping, we identify a mentor within the department and occasionally in other departments to meet regularly with the trainee. A successful mentor ensures effective regrouping and can help the trainee avoid pitfalls that they may have experienced in similar situations.

Moving forward

Occupational burnout is a systemic problem within the medical field, with trainees disproportionately affected. It is imperative that training programs continue to work toward creating a culture that prevents development of burnout. Along with the ideas presented here, the ACGME has launched AWARE, which is a suite of resources directed specifically at the GME community, with a goal of mitigating stress and preventing burnout. No one approach will be universally applicable but continued awareness and efforts to address this on an individual and programmatic level should be encouraged.

Dr. Ordway is a chief fellow, Dr. Tritsch and Dr. Singla are associate program directors, and Dr. Torres the program director, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md.

References

1. Barnes EL et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(2):302-6.

2. Dyrbye LN et al. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443-51.

3. Waldo OA. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(11):1303-6.

Ergonomics 101 for trainees

To the early trainee, often the goal of performing a colonoscopy is to reach the cecum using whatever technique necessary. Although the recommended amount of colonoscopies for safe independent practice is 140 (with some sources stating more than 500), this only relates to the safety of the patient.1 We receive scant education on how to form good procedural habits to preserve our own safety and efficiency over the course of our career. Here are some tips on how to prevent injury:

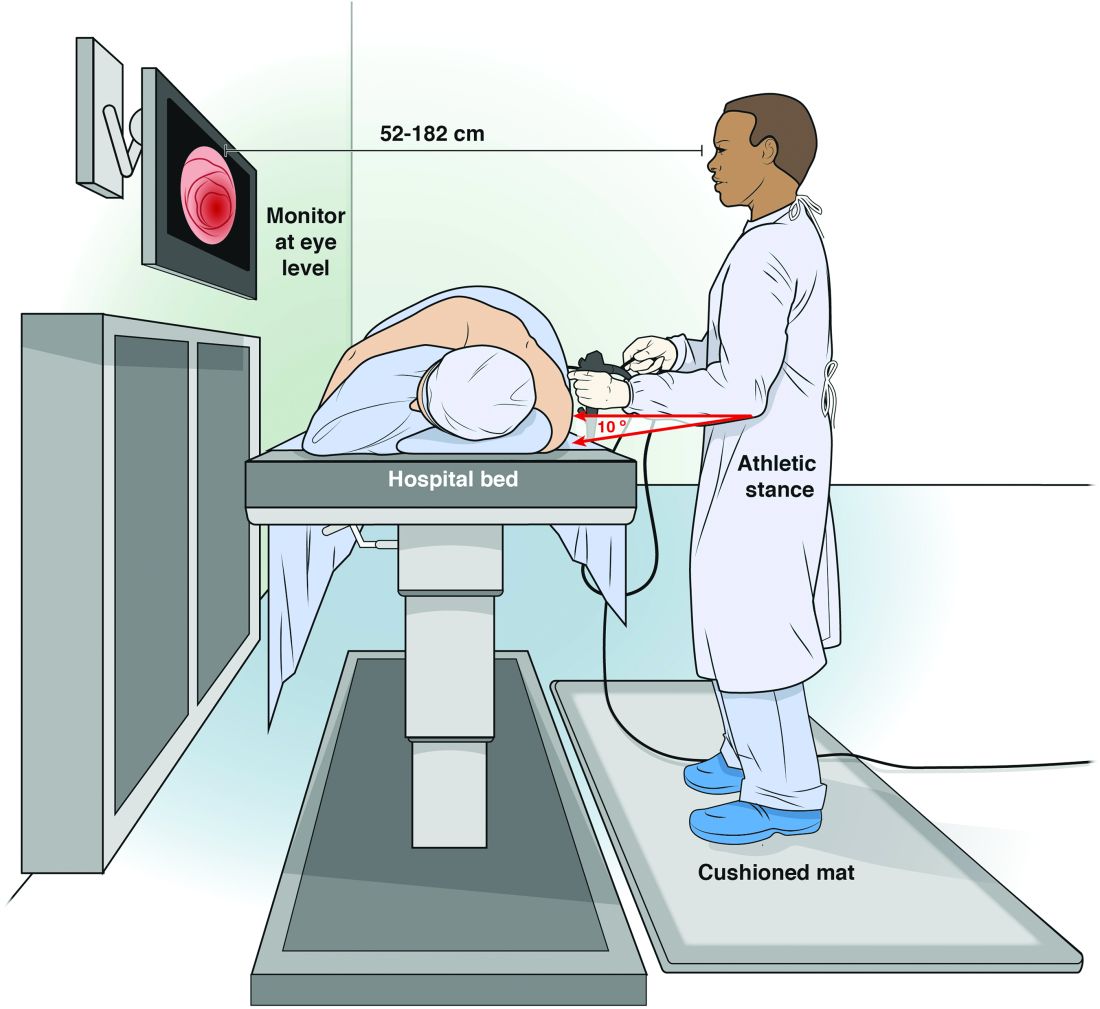

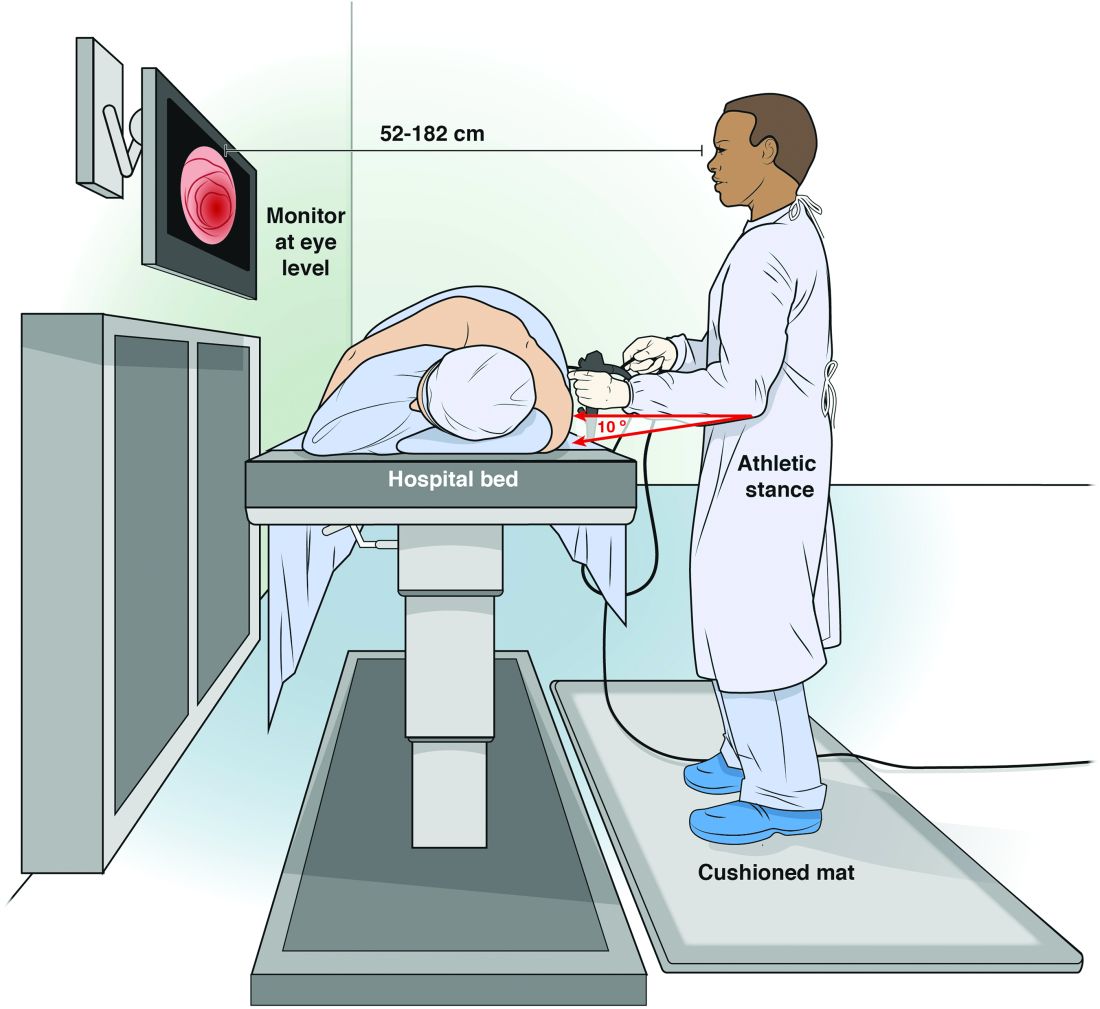

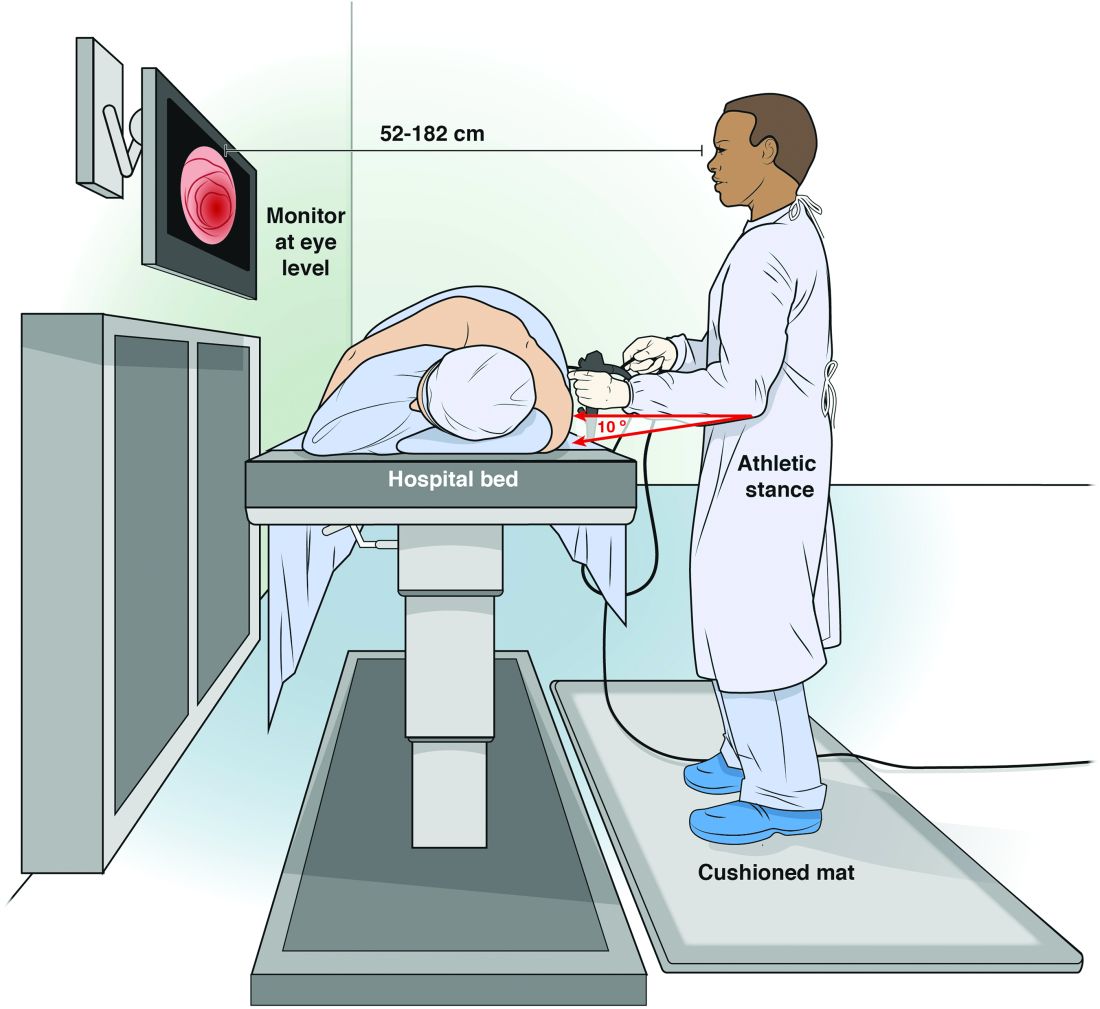

Maintain an appropriate stance. The optimal stance during endoscopy is an athletic stance: chest out, shoulders back to facilitate ease of neck movements, and a slight bend in the knees to facilitate good blood return and distribute weight. Feet should be hip width apart with toes pointed at the endoscopy screen to allow for easy pivoting of the hips and torque of upper body if needed. Ideally, this stance is complemented by the use of proper footwear and a cushioned mat to facilitate weight distribution while standing. An athletic stance facilitates a fluidity for movements from head to toe and an ability to use larger muscles groups to accomplish fine movements.

Handle the endoscope properly. Preserve energy by understanding your equipment and how to manipulate it. Orienting the endoscope directly in front of the endoscopist for upper endoscopy, and at a 45-degree angle for colonoscopy, places the instrument at optimal location to complete the procedure.5 Reviewing how to perform common techniques such as retroflexion, scope reduction, and instrumentation can also facilitate improved ergonomics and adjustment of incorrect techniques at an early stage of endoscopic training. An area of particular concern for most early trainees is the amount of rotational force placed on the right wrist with administration of torque to the endoscope. This is a foreign movement for most endoscopists and requires use of smaller muscle groups of the forearms. We suggest attempting torque with internal and external rotation of the left shoulder to utilize larger muscle groups. We can also combat fatigue during the procedure with the use of microrests intermittently to reduce prolonged muscle contraction. A common way to utilize microrests is by pinning the scope to the patient’s bed with the endoscopist’s hip to provide stability of endoscope and allow removal and relaxation of the right hand. This can be done periodically throughout the procedure to provide the ability to regroup mentally and physically.

Seek feedback. Because it is difficult to focus on ergonomics while performing a diagnostic procedure, utilize your team of observers to facilitate proper form during procedure. This includes your attending gastroenterologists, nurses, and technicians who can observe posture and technique to help detect incorrect positioning early and make corrections. A common practice is to discuss areas of desired improvement before procedures to facilitate a more vigilant observation of areas for improvement.

Assess and adjust often. As early trainees, these endoscopists perform all endoscopies under the direct supervision and often with significant assistance from a supervising gastroenterologist. This can lead to a sharp differential in psychological size; it can be hard to adjust a room to your needs when you have an intimidating and demanding attending physician who has different needs. Despite this disparity, we strongly encourage all trainees to be vigilant about adjusting the room (monitors and beds) to their own needs rather than their attendings’. A great way to head off potential conflict is to discuss the ergonomic positioning of the room before you start endoscopy with your attending, nurse, and technicians so that everyone is in agreement.

Conclusion

We offer this article as a guide for the novice endoscopist to make small changes early to prevent injuries later. Reaching competency with our skills is difficult, and we hope it can be achieved safely with our health in mind.

Dr. Magee, first-year fellow, NCC Gastroenterology; Dr. Singla, associate program director, NCC Gastroenterology, and gastroenterology service, department of internal medicine, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md.

References

1. Spier B et al. Colonoscopy training in gastroenterology fellowships: determining competence. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010 Feb;71(2):319-24G.

2. Malmström EM et al. A slouched body posture decreases arm mobility and changes muscle recruitment in the neck and shoulder region. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2015;115(12):2491-503.

3. Singla M et al. Training the endo-athlete: an update in ergonomics in endoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jul;16(7):1003-6.

4. Bexander CS, et al. Effect of gaze direction on neck muscle activity during cervical rotation. Exp Brain Res. 2005 Dec;167(3):422-32.

5. Soetikno R et al. Holding and manipulating the endoscope: A user’s guide. Techn Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;21:124-32.

To the early trainee, often the goal of performing a colonoscopy is to reach the cecum using whatever technique necessary. Although the recommended amount of colonoscopies for safe independent practice is 140 (with some sources stating more than 500), this only relates to the safety of the patient.1 We receive scant education on how to form good procedural habits to preserve our own safety and efficiency over the course of our career. Here are some tips on how to prevent injury:

Maintain an appropriate stance. The optimal stance during endoscopy is an athletic stance: chest out, shoulders back to facilitate ease of neck movements, and a slight bend in the knees to facilitate good blood return and distribute weight. Feet should be hip width apart with toes pointed at the endoscopy screen to allow for easy pivoting of the hips and torque of upper body if needed. Ideally, this stance is complemented by the use of proper footwear and a cushioned mat to facilitate weight distribution while standing. An athletic stance facilitates a fluidity for movements from head to toe and an ability to use larger muscles groups to accomplish fine movements.

Handle the endoscope properly. Preserve energy by understanding your equipment and how to manipulate it. Orienting the endoscope directly in front of the endoscopist for upper endoscopy, and at a 45-degree angle for colonoscopy, places the instrument at optimal location to complete the procedure.5 Reviewing how to perform common techniques such as retroflexion, scope reduction, and instrumentation can also facilitate improved ergonomics and adjustment of incorrect techniques at an early stage of endoscopic training. An area of particular concern for most early trainees is the amount of rotational force placed on the right wrist with administration of torque to the endoscope. This is a foreign movement for most endoscopists and requires use of smaller muscle groups of the forearms. We suggest attempting torque with internal and external rotation of the left shoulder to utilize larger muscle groups. We can also combat fatigue during the procedure with the use of microrests intermittently to reduce prolonged muscle contraction. A common way to utilize microrests is by pinning the scope to the patient’s bed with the endoscopist’s hip to provide stability of endoscope and allow removal and relaxation of the right hand. This can be done periodically throughout the procedure to provide the ability to regroup mentally and physically.

Seek feedback. Because it is difficult to focus on ergonomics while performing a diagnostic procedure, utilize your team of observers to facilitate proper form during procedure. This includes your attending gastroenterologists, nurses, and technicians who can observe posture and technique to help detect incorrect positioning early and make corrections. A common practice is to discuss areas of desired improvement before procedures to facilitate a more vigilant observation of areas for improvement.

Assess and adjust often. As early trainees, these endoscopists perform all endoscopies under the direct supervision and often with significant assistance from a supervising gastroenterologist. This can lead to a sharp differential in psychological size; it can be hard to adjust a room to your needs when you have an intimidating and demanding attending physician who has different needs. Despite this disparity, we strongly encourage all trainees to be vigilant about adjusting the room (monitors and beds) to their own needs rather than their attendings’. A great way to head off potential conflict is to discuss the ergonomic positioning of the room before you start endoscopy with your attending, nurse, and technicians so that everyone is in agreement.

Conclusion

We offer this article as a guide for the novice endoscopist to make small changes early to prevent injuries later. Reaching competency with our skills is difficult, and we hope it can be achieved safely with our health in mind.

Dr. Magee, first-year fellow, NCC Gastroenterology; Dr. Singla, associate program director, NCC Gastroenterology, and gastroenterology service, department of internal medicine, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md.

References

1. Spier B et al. Colonoscopy training in gastroenterology fellowships: determining competence. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010 Feb;71(2):319-24G.

2. Malmström EM et al. A slouched body posture decreases arm mobility and changes muscle recruitment in the neck and shoulder region. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2015;115(12):2491-503.

3. Singla M et al. Training the endo-athlete: an update in ergonomics in endoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jul;16(7):1003-6.

4. Bexander CS, et al. Effect of gaze direction on neck muscle activity during cervical rotation. Exp Brain Res. 2005 Dec;167(3):422-32.

5. Soetikno R et al. Holding and manipulating the endoscope: A user’s guide. Techn Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;21:124-32.

To the early trainee, often the goal of performing a colonoscopy is to reach the cecum using whatever technique necessary. Although the recommended amount of colonoscopies for safe independent practice is 140 (with some sources stating more than 500), this only relates to the safety of the patient.1 We receive scant education on how to form good procedural habits to preserve our own safety and efficiency over the course of our career. Here are some tips on how to prevent injury:

Maintain an appropriate stance. The optimal stance during endoscopy is an athletic stance: chest out, shoulders back to facilitate ease of neck movements, and a slight bend in the knees to facilitate good blood return and distribute weight. Feet should be hip width apart with toes pointed at the endoscopy screen to allow for easy pivoting of the hips and torque of upper body if needed. Ideally, this stance is complemented by the use of proper footwear and a cushioned mat to facilitate weight distribution while standing. An athletic stance facilitates a fluidity for movements from head to toe and an ability to use larger muscles groups to accomplish fine movements.

Handle the endoscope properly. Preserve energy by understanding your equipment and how to manipulate it. Orienting the endoscope directly in front of the endoscopist for upper endoscopy, and at a 45-degree angle for colonoscopy, places the instrument at optimal location to complete the procedure.5 Reviewing how to perform common techniques such as retroflexion, scope reduction, and instrumentation can also facilitate improved ergonomics and adjustment of incorrect techniques at an early stage of endoscopic training. An area of particular concern for most early trainees is the amount of rotational force placed on the right wrist with administration of torque to the endoscope. This is a foreign movement for most endoscopists and requires use of smaller muscle groups of the forearms. We suggest attempting torque with internal and external rotation of the left shoulder to utilize larger muscle groups. We can also combat fatigue during the procedure with the use of microrests intermittently to reduce prolonged muscle contraction. A common way to utilize microrests is by pinning the scope to the patient’s bed with the endoscopist’s hip to provide stability of endoscope and allow removal and relaxation of the right hand. This can be done periodically throughout the procedure to provide the ability to regroup mentally and physically.

Seek feedback. Because it is difficult to focus on ergonomics while performing a diagnostic procedure, utilize your team of observers to facilitate proper form during procedure. This includes your attending gastroenterologists, nurses, and technicians who can observe posture and technique to help detect incorrect positioning early and make corrections. A common practice is to discuss areas of desired improvement before procedures to facilitate a more vigilant observation of areas for improvement.

Assess and adjust often. As early trainees, these endoscopists perform all endoscopies under the direct supervision and often with significant assistance from a supervising gastroenterologist. This can lead to a sharp differential in psychological size; it can be hard to adjust a room to your needs when you have an intimidating and demanding attending physician who has different needs. Despite this disparity, we strongly encourage all trainees to be vigilant about adjusting the room (monitors and beds) to their own needs rather than their attendings’. A great way to head off potential conflict is to discuss the ergonomic positioning of the room before you start endoscopy with your attending, nurse, and technicians so that everyone is in agreement.

Conclusion

We offer this article as a guide for the novice endoscopist to make small changes early to prevent injuries later. Reaching competency with our skills is difficult, and we hope it can be achieved safely with our health in mind.

Dr. Magee, first-year fellow, NCC Gastroenterology; Dr. Singla, associate program director, NCC Gastroenterology, and gastroenterology service, department of internal medicine, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md.

References

1. Spier B et al. Colonoscopy training in gastroenterology fellowships: determining competence. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010 Feb;71(2):319-24G.

2. Malmström EM et al. A slouched body posture decreases arm mobility and changes muscle recruitment in the neck and shoulder region. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2015;115(12):2491-503.

3. Singla M et al. Training the endo-athlete: an update in ergonomics in endoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jul;16(7):1003-6.

4. Bexander CS, et al. Effect of gaze direction on neck muscle activity during cervical rotation. Exp Brain Res. 2005 Dec;167(3):422-32.

5. Soetikno R et al. Holding and manipulating the endoscope: A user’s guide. Techn Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;21:124-32.

Training the endo-athlete – an update in ergonomics in endoscopy

As physicians, we work hard to take excellent care of our patients. Years of thoughtful practice and continuous learning allow us to deliver the best that medicine can provide. We often take poor care of ourselves, which can lead to burnout and physical injuries. As gastroenterologists, we spend substantial time performing endoscopic procedures that require repetitive motions such as flexion and extension of the wrist and fingers and torsional movements of the right hand, which may lead to overuse injuries. The volume of endoscopic procedures performed by a typical gastroenterologist has increased significantly in the past 20 years. Moreover, experts predict that by 2020 we will have too few endoscopists to meet clinical demands.1 It is imperative that we do whatever possible to ensure overuse injuries do not prematurely prevent us from providing much-needed care. One way to achieve this goal is to focus on ergonomics. The study of ergonomics, derived from the Greek words ergo (work) and nomos (law), seeks to optimize the interface between the worker, the equipment, and the work environment. This article reviews basic ergonomic principles that endoscopists can apply today and possible innovations that may improve endoscopic ergonomics in the future.

Breadth of the problem

Examinations of injuries related to endoscopy are limited to survey-based and small controlled studies with a 39%-89% overall prevalence of pain or musculoskeletal injuries reported.2 In a survey of 684 American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy members examining injury prevalence and risk factors,3 53% experienced an injury believed to be definitely or probably related to endoscopy. Risk factors included higher procedure volume (more than 20 cases/wk), greater number of hours spent performing endoscopy (more than 16 h/wk), and total number of years spent performing endoscopy2,4. Community practitioners reported injuries at higher rates than those in an academic center. Other suggested but unproven risk factors include age5, sex, hand size, room design, and level of training in ergonomics and endoscopy2. Injuries can be severe and may lead to work load reduction, missed days of work3-5, reduction of activities outside of work, and long-term disability2.

Most surveys reflect symptoms localized to the back, neck, shoulder, elbow, hands/fingers, and thumbs likely from overuse causing strain and soft-tissue microtrauma6. Without time to heal, these injuries may lead to connective tissue weakening and permanent damage. Repetitive hand movements in endoscopy include left thumb abduction, flexion, and extension while manipulating dials and right wrist flexion, extension, and deviation from torqueing the insertion tube. The use of torque is a necessary part of successful colonoscopy; during scope reduction and maneuvering through the sigmoid colon, torque forces and forces applied against the wall of the colon are highest. When of sufficient magnitude and duration, these forces are associated with an increased risk of thumb and wrist injuries. These movements may result in “endoscopist’s thumb“ (i.e., de Quervain’s tenosynovitis) and carpal tunnel syndrome2. Prolonged standing and lead aprons are implicated in back and neck injuries;2,7-9 two-piece aprons,7,10 and antifatigue mats7 are recommended to decrease pressure on the lumbar and cervical disks as well as delay muscle fatigue.

Position of equipment

Endoscopist and patient positioning can be optimized. In the absence of direct data about ergonomics in endoscopy, we rely on surgical laparoscopy data.11,12These studies show that monitors placed directly in front of surgeons at eye-level (rather than off to the side or at the head of the bed) reduced neck and shoulder muscle activity. Monitors should be placed with a height 20 cm lower than the height of the surgeon (endoscopist), suggesting that optimized monitor height should be at eye-level or lower to prevent neck strain. Estimates based on computer simulation and laparoscopy practitioners show that the optimal distance between the endoscopist/surgeon and a 14” monitor is between 52 and 182 cm, which allows for the least amount of image degradation. Many modern monitors are larger (19”-26”), which allows for placement farther from the endoscopist without losing image quality. Bed height affects both spine and arm position; surgical data again suggest that optimal bed height is between elbow height and 10 cm below elbow height.

Immediate practice points

Since poor monitor placement was identified as a major risk factor for musculoskeletal injuries, the first steps in our endoscopy unit were to improve our sightlines. Our adjustable monitors previously were locked into a specific height, and those same monitors now easily are adjusted to heights appropriate to the endoscopist. Our practice has endoscopists from 61” to 77” tall, meaning we needed monitors that could adjust over a 16” height. When designing new endoscopy suites, monitors that adjust from 93 to 162 cm would accommodate the 5th percentile of female height to the 95th percentile of male height. We use adjustable-height beds; a bed that adjusts between 85 and 120 cm would accommodate the 5th percentile of female height to the 95th percentile of male height.

We also moved our monitors to be closer to the opposite side of the bed to accommodate the 3’ to 6’ appropriate to our 16” screens. Our endoscopy suites have cushioned washable mats placed where endoscopists stand that allow for slight instability of the legs, leading to subtle movements of the legs and increased blood flow to reduce foot and leg injuries. We attempt an athletic stance (the endo-athlete) during endoscopy: shoulders back, chest out, knees bent, and feet hip-width apart pointed at the endoscopy screen (Figure 1). These mats help prevent pelvic girdle twisting and turning that may lead to awkward positions and instead leave the endoscopist in an optimized position for the procedure. We encourage endoscopists to keep the scope in the most neutral position possible to reduce overuse of torque and the forces on the wrists and thumbs. When possible, we use two-piece lead aprons for procedures that require fluoroscopy, which transfers some of the weight of the apron from the shoulders to the hips and reduces upper-body strain. Optimization of the room for therapeutic procedures is even more important (with dual screens both fulfilling the criteria we have listed earlier) given the extra weight of the lead on the body. We suggest that, if procedures are performed in cramped endoscopy rooms, placement of additional monitors can help alleviate neck strain and rotation.

Working with our nurses was imperative. We first had our nurses watch videos on appropriate ergonomics in the endoscopy suite. Given that endoscopists usually are concentrating their attention on the screens in the suite, we tasked our nurses to not only monitor our patients, but also to observe the physical stance of the endoscopists. Our nurses are encouraged to help our endoscopists focus on their working stance: the nurses help with monitor positioning, and verbal cues when endoscopists are contorting their bodies unnaturally. This intervention requires open two-way communication in the endoscopy suite where safety of both the patient and staff is paramount. We are fortunate to be at an institution that trains fellows; we have two endoscopists in the suite at any time, which allows for additional two-way feedback between fellows and attendings to improve ergonomic positioning.

We also encourage some preventative exercises of the upper extremities to reduce pain and injuries. Stretches should emphasize finger, wrist, forearm, and shoulder flexion and extension. Even a minute of stretching between procedures allows for muscle relaxation and may lead to a decrease in overuse injuries. Adding these elements may seem inefficient and unnecessary if you have never had an injury, but we suggest the following paradigm: think of yourself as an endo-athlete. Similar to an athlete, you have worked years to gain the skills you possess. Taking a few moments to reduce your chances of a career-slowing (or career-ending) injury can pay long-term dividends.

Future remedies

Although there have been substantial advances in endoscopic imaging technology, the process of endoscope rotation and tip deflection has changed little since the development of flexible endoscopy. A freshman engineering student tasked with designing a device to navigate, examine, and provide therapy in the human colon likely would create a device that does not resemble the scope that we use daily to accomplish the task. Numerous investigators currently are working on novel devices designed to examine and deliver therapy to the digestive tract. These devices may diminish an endoscopist’s injury risk through the use of better ergonomic principles. This section is not intended to be a comprehensive review and is not an endorsement of any particular product. Rather, we hope it provides a glimpse into a possible future.

Reducing gravitational load

The concept of a mechanical device to hold some or all of the weight of the endoscope was first published in 197413. Since then, a number of products have been described for this purpose.14-17 In general, these consist of a simple metal tube with a hemicylindrical plastic clip, similar to a microphone stand, or a yoke/strap with a plastic scope holder in the front akin to what a percussionist in a marching band might wear. For a variety of reasons, including limited mobility and issues with disinfection, these devices have not gained traction.

Novel control mechanisms

Some of the largest forces on the endoscopist relate to moving the wheels on the scope head to effect tip deflection via a cable linkage. Because the wheels rotate only in one axis, the options for altering and adjusting load are few. One proposed solution is the use of a system with a fully detachable endoscope handle with a joystick style control deck (E210; Invendo Medical, Kissing, Germany). The control deck uses electromechanical assistance — as opposed to pure mechanical force — to transmit energy to the shaft of the instrument. Such assistive technologies have the potential to decrease injuries by decreased load, particularly on the carpometacarpal joint. Other devices seek to decrease the need for torque and high-load tip deflection though the use of self-propelled, disposable colonoscopes that use an aviation-style joystick (Aer-o-scope; GI View, Kissing, Germany). Although interesting and potentially useful, neither product is currently available for clinical use in the United States.

Robots and magnets

Magnetically controlled wireless capsules have been studied in vivo in human beings on several occasions in the United Kingdom and Asia. Wired colonic capsules are currently under development in the United States. These products use joystick-style controls to direct movement of the capsule. Optimal visualization often requires the patient to rotate through numerous positions and, at least in the stomach, to drink significant quantities of fluid to ensure adequate distention. At present, these devices provide only diagnostic capabilities.

Conclusions

The performance of endoscopy inherently places its practitioners at risk of biomechanical injury. Fortunately, there are numerous ways we can optimize our environment and ourselves. We should treat our bodies as professional athletes do: use good form, encourage colleagues to observe and provide feedback on our actions, optimize our practice facilities, and stretch our muscles. In the future, technological innovations, such as ergonomically designed endoscope handles and self-propelled colonoscopies, may reduce the inherent physical stresses of endoscopy. In doing so, hopefully we can preserve our own health and continue to better the health of our patients as well.

References

1. Rabin RC. Gastroenterologist shortage is forecast. (Available at: www.nytimes.com/2009/01/09/health/research/09gastro.html.) The New York Times, Jan. 9;2009.

2. Pedrosa MC, Farraye FA, Shergill AK. et al. Minimizing occupational hazards in endoscopy: personal protective equipment, radiation safety, and ergonomics. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:227-35.

3. Ridtitid W, Coté GA, Leung W, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for musculoskeletal injuries related to endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:294-302.e294.

4. Geraghty J, George R, Babbs C. A questionnaire study assessing overuse injuries in United Kingdom endoscopists and any effect from the introduction of the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program on these injuries. Gastrointest Endos. 2011;73:1069-70.

5. Kuwabara T, Urabe Y, Hiyama T, et al. Prevalence and impact of musculoskeletal pain in Japanese gastrointestinal endoscopists: a controlled study. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1488-93.

6. Rempel DM, Harrison RJ, Barnhart S. Work-related cumulative trauma disorders of the upper extremity. JAMA 1992;267:838-42.

7. O’Sullivan S, Bridge G, Ponich T. Musculoskeletal injuries among ERCP endoscopists in Canada. Can J Gastroenterol. 2002;16:369-74.

8. Moore B, vanSonnenberg E, Casola G. et al. The relationship between back pain and lead apron use in radiologists. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;158:191-3.

9. Ross AM, Segal J, Borenstein D, et al. Prevalence of spinal disc disease among interventional cardiologists. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:68-70.

10. Buschbacher R. Overuse syndromes among endoscopists. Endoscopy. 1994;26:539-44.

11. Matern U, Faist M, Kehl K, et al. Monitor position in laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:436-40.

12. Haveran LA, Novitsky YW, Czerniach DR, et al. Optimizing laparoscopic task efficiency: the role of camera and monitor positions. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:980-4.

13. Nivatvongs S, Goldberg SM. Holder for the fiberoptic colonoscope. Dis Colon Rectum. 1974;17:273-4.

14. Eusebio EB. A practical aid in colonoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:996-7.

15. Rattan J, Rozen P. A new colonoscope holder. Dis Colon Rectum. 1987;30:639-40.

16. Marks G. A new technique of hand reversal using a harness-type endoscope holder for twin-knob colonoscopy and flexible fiberoptic sigmoidoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24:567-8.

17. Hayashi Y, Sunada K, Yamamoto H. Prototype holder adequately supports the overtube in balloon-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:682.

Dr. Young is professor of medicine, director, digestive disease division, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Md.; Dr. Commander Singla is assistant professor of medicine, Uniformed Services University, director, Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Services, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md.; Dr. Major Kwok is assistant professor of medicine, Uniformed Services University, associate fellowship program director, gastroenterology, National Capital Consortium, Bethesda, Md.; and Dr. Deriban is associate professor of medicine, fellowship program director, gastroenterology, University Hospital Skopje, Macedonia.

As physicians, we work hard to take excellent care of our patients. Years of thoughtful practice and continuous learning allow us to deliver the best that medicine can provide. We often take poor care of ourselves, which can lead to burnout and physical injuries. As gastroenterologists, we spend substantial time performing endoscopic procedures that require repetitive motions such as flexion and extension of the wrist and fingers and torsional movements of the right hand, which may lead to overuse injuries. The volume of endoscopic procedures performed by a typical gastroenterologist has increased significantly in the past 20 years. Moreover, experts predict that by 2020 we will have too few endoscopists to meet clinical demands.1 It is imperative that we do whatever possible to ensure overuse injuries do not prematurely prevent us from providing much-needed care. One way to achieve this goal is to focus on ergonomics. The study of ergonomics, derived from the Greek words ergo (work) and nomos (law), seeks to optimize the interface between the worker, the equipment, and the work environment. This article reviews basic ergonomic principles that endoscopists can apply today and possible innovations that may improve endoscopic ergonomics in the future.

Breadth of the problem

Examinations of injuries related to endoscopy are limited to survey-based and small controlled studies with a 39%-89% overall prevalence of pain or musculoskeletal injuries reported.2 In a survey of 684 American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy members examining injury prevalence and risk factors,3 53% experienced an injury believed to be definitely or probably related to endoscopy. Risk factors included higher procedure volume (more than 20 cases/wk), greater number of hours spent performing endoscopy (more than 16 h/wk), and total number of years spent performing endoscopy2,4. Community practitioners reported injuries at higher rates than those in an academic center. Other suggested but unproven risk factors include age5, sex, hand size, room design, and level of training in ergonomics and endoscopy2. Injuries can be severe and may lead to work load reduction, missed days of work3-5, reduction of activities outside of work, and long-term disability2.

Most surveys reflect symptoms localized to the back, neck, shoulder, elbow, hands/fingers, and thumbs likely from overuse causing strain and soft-tissue microtrauma6. Without time to heal, these injuries may lead to connective tissue weakening and permanent damage. Repetitive hand movements in endoscopy include left thumb abduction, flexion, and extension while manipulating dials and right wrist flexion, extension, and deviation from torqueing the insertion tube. The use of torque is a necessary part of successful colonoscopy; during scope reduction and maneuvering through the sigmoid colon, torque forces and forces applied against the wall of the colon are highest. When of sufficient magnitude and duration, these forces are associated with an increased risk of thumb and wrist injuries. These movements may result in “endoscopist’s thumb“ (i.e., de Quervain’s tenosynovitis) and carpal tunnel syndrome2. Prolonged standing and lead aprons are implicated in back and neck injuries;2,7-9 two-piece aprons,7,10 and antifatigue mats7 are recommended to decrease pressure on the lumbar and cervical disks as well as delay muscle fatigue.

Position of equipment

Endoscopist and patient positioning can be optimized. In the absence of direct data about ergonomics in endoscopy, we rely on surgical laparoscopy data.11,12These studies show that monitors placed directly in front of surgeons at eye-level (rather than off to the side or at the head of the bed) reduced neck and shoulder muscle activity. Monitors should be placed with a height 20 cm lower than the height of the surgeon (endoscopist), suggesting that optimized monitor height should be at eye-level or lower to prevent neck strain. Estimates based on computer simulation and laparoscopy practitioners show that the optimal distance between the endoscopist/surgeon and a 14” monitor is between 52 and 182 cm, which allows for the least amount of image degradation. Many modern monitors are larger (19”-26”), which allows for placement farther from the endoscopist without losing image quality. Bed height affects both spine and arm position; surgical data again suggest that optimal bed height is between elbow height and 10 cm below elbow height.

Immediate practice points

Since poor monitor placement was identified as a major risk factor for musculoskeletal injuries, the first steps in our endoscopy unit were to improve our sightlines. Our adjustable monitors previously were locked into a specific height, and those same monitors now easily are adjusted to heights appropriate to the endoscopist. Our practice has endoscopists from 61” to 77” tall, meaning we needed monitors that could adjust over a 16” height. When designing new endoscopy suites, monitors that adjust from 93 to 162 cm would accommodate the 5th percentile of female height to the 95th percentile of male height. We use adjustable-height beds; a bed that adjusts between 85 and 120 cm would accommodate the 5th percentile of female height to the 95th percentile of male height.

We also moved our monitors to be closer to the opposite side of the bed to accommodate the 3’ to 6’ appropriate to our 16” screens. Our endoscopy suites have cushioned washable mats placed where endoscopists stand that allow for slight instability of the legs, leading to subtle movements of the legs and increased blood flow to reduce foot and leg injuries. We attempt an athletic stance (the endo-athlete) during endoscopy: shoulders back, chest out, knees bent, and feet hip-width apart pointed at the endoscopy screen (Figure 1). These mats help prevent pelvic girdle twisting and turning that may lead to awkward positions and instead leave the endoscopist in an optimized position for the procedure. We encourage endoscopists to keep the scope in the most neutral position possible to reduce overuse of torque and the forces on the wrists and thumbs. When possible, we use two-piece lead aprons for procedures that require fluoroscopy, which transfers some of the weight of the apron from the shoulders to the hips and reduces upper-body strain. Optimization of the room for therapeutic procedures is even more important (with dual screens both fulfilling the criteria we have listed earlier) given the extra weight of the lead on the body. We suggest that, if procedures are performed in cramped endoscopy rooms, placement of additional monitors can help alleviate neck strain and rotation.

Working with our nurses was imperative. We first had our nurses watch videos on appropriate ergonomics in the endoscopy suite. Given that endoscopists usually are concentrating their attention on the screens in the suite, we tasked our nurses to not only monitor our patients, but also to observe the physical stance of the endoscopists. Our nurses are encouraged to help our endoscopists focus on their working stance: the nurses help with monitor positioning, and verbal cues when endoscopists are contorting their bodies unnaturally. This intervention requires open two-way communication in the endoscopy suite where safety of both the patient and staff is paramount. We are fortunate to be at an institution that trains fellows; we have two endoscopists in the suite at any time, which allows for additional two-way feedback between fellows and attendings to improve ergonomic positioning.

We also encourage some preventative exercises of the upper extremities to reduce pain and injuries. Stretches should emphasize finger, wrist, forearm, and shoulder flexion and extension. Even a minute of stretching between procedures allows for muscle relaxation and may lead to a decrease in overuse injuries. Adding these elements may seem inefficient and unnecessary if you have never had an injury, but we suggest the following paradigm: think of yourself as an endo-athlete. Similar to an athlete, you have worked years to gain the skills you possess. Taking a few moments to reduce your chances of a career-slowing (or career-ending) injury can pay long-term dividends.

Future remedies

Although there have been substantial advances in endoscopic imaging technology, the process of endoscope rotation and tip deflection has changed little since the development of flexible endoscopy. A freshman engineering student tasked with designing a device to navigate, examine, and provide therapy in the human colon likely would create a device that does not resemble the scope that we use daily to accomplish the task. Numerous investigators currently are working on novel devices designed to examine and deliver therapy to the digestive tract. These devices may diminish an endoscopist’s injury risk through the use of better ergonomic principles. This section is not intended to be a comprehensive review and is not an endorsement of any particular product. Rather, we hope it provides a glimpse into a possible future.

Reducing gravitational load

The concept of a mechanical device to hold some or all of the weight of the endoscope was first published in 197413. Since then, a number of products have been described for this purpose.14-17 In general, these consist of a simple metal tube with a hemicylindrical plastic clip, similar to a microphone stand, or a yoke/strap with a plastic scope holder in the front akin to what a percussionist in a marching band might wear. For a variety of reasons, including limited mobility and issues with disinfection, these devices have not gained traction.

Novel control mechanisms

Some of the largest forces on the endoscopist relate to moving the wheels on the scope head to effect tip deflection via a cable linkage. Because the wheels rotate only in one axis, the options for altering and adjusting load are few. One proposed solution is the use of a system with a fully detachable endoscope handle with a joystick style control deck (E210; Invendo Medical, Kissing, Germany). The control deck uses electromechanical assistance — as opposed to pure mechanical force — to transmit energy to the shaft of the instrument. Such assistive technologies have the potential to decrease injuries by decreased load, particularly on the carpometacarpal joint. Other devices seek to decrease the need for torque and high-load tip deflection though the use of self-propelled, disposable colonoscopes that use an aviation-style joystick (Aer-o-scope; GI View, Kissing, Germany). Although interesting and potentially useful, neither product is currently available for clinical use in the United States.

Robots and magnets

Magnetically controlled wireless capsules have been studied in vivo in human beings on several occasions in the United Kingdom and Asia. Wired colonic capsules are currently under development in the United States. These products use joystick-style controls to direct movement of the capsule. Optimal visualization often requires the patient to rotate through numerous positions and, at least in the stomach, to drink significant quantities of fluid to ensure adequate distention. At present, these devices provide only diagnostic capabilities.

Conclusions

The performance of endoscopy inherently places its practitioners at risk of biomechanical injury. Fortunately, there are numerous ways we can optimize our environment and ourselves. We should treat our bodies as professional athletes do: use good form, encourage colleagues to observe and provide feedback on our actions, optimize our practice facilities, and stretch our muscles. In the future, technological innovations, such as ergonomically designed endoscope handles and self-propelled colonoscopies, may reduce the inherent physical stresses of endoscopy. In doing so, hopefully we can preserve our own health and continue to better the health of our patients as well.

References

1. Rabin RC. Gastroenterologist shortage is forecast. (Available at: www.nytimes.com/2009/01/09/health/research/09gastro.html.) The New York Times, Jan. 9;2009.

2. Pedrosa MC, Farraye FA, Shergill AK. et al. Minimizing occupational hazards in endoscopy: personal protective equipment, radiation safety, and ergonomics. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:227-35.

3. Ridtitid W, Coté GA, Leung W, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for musculoskeletal injuries related to endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:294-302.e294.