User login

Operational Lessons from a Large Accountable Care Organization

From Partners HealthCare, Boston, MA.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe operational lessons from a large accountable care organization (ACO).

- Methods: Description of an approach that includes the creation of a sustainable financing mechanism, new incentive structures, a high risk care management program, integrated mental health services, tools for specialist engagement, a post acute strategy, fostering patient engagement, and new clinical and analytic technologies.

- Results: Committed ACOs face challenges in enacting care delivery changes. Key challenges include educating boards and management about requirements for success as an ACO; advocacy for state and federal regulations that support the success of ACOs; and engaging patients as active participants in the changes. Importantly, financial returns (as shared savings) on the investment required for these changes will not be available within short-term contract cycles, so committed organizations will need to plan for the long haul.

- Conclusion: A comprehensive approach undertaken within a system that is capable of integrating care across the full continuum of care delivery has the best chance for successfully managing costs and improving care.

After Massachusetts enacted legislation expanding health insurance to nearly all residents in 2006, additional legislation was enacted that focused on health cost containment. The goal of the many new regulations has been to hold the rate of health care cost growth to the rate of general inflation. Consistent with payment policy changes under the Accountable Care Act, Massachusetts regulatory efforts have emphasized putting health care providers at financial risk for some proportion of increases in costs of care. Providers who contract as accountable care organizations (ACOs) typically conduct their usual fee-for-service billing practices, but in addition the providers also agree to an annual total medical expenses (TME) spending target for an assigned population of patients. An annual reconciliation results in either penalties for exceeding targets or shared savings if spending remains below the target. The reconciliation incorporates a small number of commonly used primary care quality measures.

Partners HealthCare, an integrated health care delivery system in Massachusetts that includes 2 large academic medical centers—Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH)—began deploying new care models designed to reduce the growth in health care costs prior to these policy changes, but the new contracting environment has dramatically accelerated these efforts. Partners HealthCare signed accountable care risk contracts across all major payer categories—commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid—in 2011. Currently, Partners HealthCare has accountability for cost increases for nearly 500,000 lives, making it one of the largest providers of accountable care in the United States [1].

In this paper, we describe some of the initial lessons learned and share some of our concerns for the future success of risk-based contracting. We have organized the paper as we have organized our work—addressing different care services by site of care: primary care, specialty care, non-acute care, patient engagement, and necessary infrastructure. This framework has allowed us to engage the care providers throughout our organization with programs tailored to their specific circumstances. While practical, this framework is nonetheless somewhat artificial because much of our work could be characterized as building bridges between sites of care.

Organizing System-Wide ACO Programs

Focused efforts to lower cost trends and improve outcomes for a defined population began with MGH’s participation in a Medicare demonstration project in 2006. This successful program assigned specially trained nurse care managers to over 2000 of MGH’s highest cost Medicare beneficiaries [2]. The program was expanded in 2009 and then again in 2012, and now includes the entire Partners system. Building on this success, Partners’ providers evolved a broader set of tactics to include data, measurement and evidence-based methods of improving access, continuity, and care coordination to provide population-based health care [3,4]. To coordinate the system-wide work required by new risk contracting arrangements, Partners created the Division of Population Health Management (PHM). PHM works closely with organizational leadership at member institutions to collaboratively design and execute its system-wide accountable care strategy.

PHM has developed capacity, infrastructure, and expertise to implement and manage a clinical strategy for the entire integrated delivery system. This included some governance changes, new management processes, new investments in information technology and establishing system-wide incentives to promote care delivery innovation and improvement. Most importantly, through an extensive planning process Partners identified a comprehensive set of tactics and a multi-year plan for system-wide adoption of those tactics.

The majority of Partners information infrastructure to date was built internally, which allowed for rapid customization and flexibility, but also created significant interoperability problems. Moving forward, the majority of Partners systems will use a single IT platform. Partners has developed and implemented patient registries and care management decision support tools to help focus provider attention on patients most in need of interventions and to support reporting of quality metrics. In addition, Partners continues to expand a comprehensive data warehouse that incorporates a variety of clinical, administrative, and financial data sources to support advanced analytics for self-monitoring and continuous improvement. This extensive network-wide approach over the past several years has generated a number of lessons regarding successful accountable care organization implementation.

Implementing New Financing and Incentive Structures

Once an ACO is formed, the organization needs to restructure management to create organizational accountability for performance (as noted above), determine how to finance programmatic initiatives required to deliver the performance called for in the contracts, and create incentives for all the different providers within the ACO to drive performance towards the system’s goals. These latter two require the ACO to make specific design choices that include some trade-offs.

Partners chose to fund system-level population health management initiatives through a tax on net patient service revenue from its member providers—both hospitals and physicians. Alternative approaches include either setting aside a yearly allocation that is not proportional to a revenue stream or simply allocating the external risk to different operating units and allowing them to determine their own individual approaches (and investments) to managing the financial risk. By linking financing of PHM programs to clinical revenue (independent of risk contracts), and setting a uniform percentage tax, Partners has signaled that the wealthier parts of the system will contribute more to PHM (on an absolute basis) and more importantly that accountable care is a prioritized long-term investment. Allowing each entity within the organization to “sink or swim” based on its own performance was considered inconsistent with the interdependent nature of care delivery in a well functioning system. In addition, investments in the required infrastructure cannot be dependent on annual contract performance due to the volatility in contracted performance and the time it takes for an organization to get a return on their PHM investment.

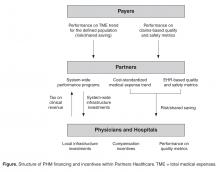

Any organization involved in multiple performance based risk contracts faces the challenge of organizing the tactics and metrics for their providers. It is simply inconsistent with provider values and workflow to manage to different targets for different subpopulations of patients. In our attempts to promote the best possible care for all our patients and at the same time meet the demands of multiple external contract requirements, we have created an internal performance framework (IPF) that uses a single set of performance targets and a single incentive pool for all out contracts. The IPF rewards member institutions for (1) adopting programmatic initiatives (funded through the tax as described above), (2) meeting external quality measure targets, and (3) limiting the growth of cost-standardized medical expense trend (Figure).

Fixing Primary Care

Populations in risk contracts are typically defined by their primary care providers. In addition, the chronic underfunding of primary care in the US has resulted in unsustainable practice environments as well as well known access problems. Finally, the concentration of costs in a relatively small proportion of patients provides the greatest opportunity for ACOs to reduce costs through better care coordination for these patients. This core set of facts has guided our efforts to improve primary care. To address these issues, we have increased funding to primary care through our efforts to certify all 236 practices as patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs). In addition, we have begun transitioning our compensation models to include components based on risk-adjusted panel size and performance on quality metrics. As mentioned above, we have invested heavily in our complex care management program. Finally, we are working on a much tighter integration of mental health services with primary care. In this section we focus on lessons from our care management program and our efforts in mental health integration.

Complex Care Management

Provider-led high-risk care management has become the primary clinical lever for cost containment for most accountable care organizations [6]. The design and operational characteristics or our program have been described by Hong et al and are available on our website. Our decade of experience with this program has taught us a few lessons regarding the use of algorithms to identify patients, the management of program costs, and the difficulty of creating meaningful accountability.

Our analysis of commercially available risk prediction algorithms found minimal differences among the various products’ ability to predict high cost patients in the following year. A majority of the algorithms are exclusively claims based, though some include the ability to augment risk predictions with clinical data. Clinicians have played a critical role in improving our ability to identify high-risk patients. We have found that when physicians review a pre-selected set of their own patients, they have some ability to discriminate among patients who are likely to benefit from care management and those who are not. Clinicians are prone to overemphasizing recent events, but review of a list of patients who are predicted of becoming high cost mitigates this problem. Commercially available algorithms can help create an initial list, but physicians can add perspective on such important factors as social support and executive functioning. This additional information improves the specificity of the initial algorithm outputs, allowing clinicians to play an important role in refining the lists of patients eligible for high-risk care management.

The high cost of labor and space make high-risk care management programs among the most costly programs for an ACO. Care management requires a skilled nursing workforce (among others), which should be embedded into the primary care office for optimal effect [6,7].Given the high costs, there is understandable pressure to increase the ratio of patients per care manager. We have found that the optimal ratio is approximately 200 patients per care manager, with a third of the patients having active complex care management issues, a third being passively surveyed, and a third requiring modest care coordination. We continue with our attempts to refine how we manage this critical aspect of care management programs.

How can managers demonstrate that the investment in care coordination is impacting the ACO’s TME trend? Demonstrating a return on investment is difficult because a population of high-cost patients will inevitably show reduced costs in the following year (a phenomenon called regression to the mean). Isolating a well-matched control group to demonstrate program effectiveness would have the unintended consequence of reducing the potential effectiveness of the program. This situation is complicated by the different risk profiles of high-risk patients in different payer categories. For example, potentially avoidable Medicare costs are dominated by hospitalizations and end-of-life issues, Medicaid costs by mental illness and substance abuse, and commercial costs by specialty issues. In lieu of better management tools to assess the performance of our program, we have depended to date on process measures (eg., enrollment targets), patient surveys, and we are experimenting with some limited outcomes metrics (eg, admissions/1000).

Mental Health Integration

Another important lever for medical trend reduction within an ACO is the integration of mental health services into primary care. While our efforts in this complex area are only about a year old, some of our early lessons may prove valuable to others. First, we have worked hard to make the case for investment in mental health services, requiring assembling the evidence both for the magnitude of the problem as well as the effectiveness of available solutions.

A quarter of American adults suffer from diagnosable mental health disorders every year and it is estimated that PCPs manage between 40% and 80% of these patients [8,9].Rates of detection and adequate treatment in primary care settings are currently suboptimal, leading to poor disease management and driving excess utilization. Using claims data within the Partners’ primary care population, we have found medical expenditures are 45% higher for patients with a mental health diagnosis. Over 70% of mental health patients have additional illnesses, and the presence of a mental health disorder complicates overall clinical management [10].This results in a substantial increase in medical cost, independent of psychiatric medical spending [11].In addition, psychiatry shortage and access have become a major issue in mental health services [12].Over 70% of PCPs nationwide reported difficulty in finding high-quality outpatient mental health care for their patients [13].

The dominant clinical model for mental health integration is the collaborative care model (CCM), and evidence for its effectiveness is growing. Randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses have shown that CCMs are successful at improving detection and treatment of mental health disorders [14–16].Cost-savings analyses for many of these programs demonstrate considerable savings and favorable return on investment (ROI). Several CCMs that use nonmedical specialists and consulting psychiatrists to augment the management of mental health disorders for low- to moderate-risk primary care patients have been implemented. However, a majority of the CCMs are disease-specific—eg, integrating depression treatment resources into primary care. The challenge for ACOs is to determine how to build a comprehensive CCM that helps primary care manage the major primary care–based mental health conditions—depression, anxiety and substance abuse—in a coordinated, cost-efficient model. The ACO must consider how to implement both its high-risk program and its CCM programs in a way that is not disruptive but supportive to primary care practices.

Partners is implementing a multipronged strategy to address mental health issues within primary care. First, a universal screening program for mental health disorders using brief, well-validated screening tools (eg, Patient Health Questionnaire 2 and 9) will improve the identification of patients with mental health disorders. Second, consulting psychiatrist and mid-level health care providers, functioning as mental health specialists, will be virtually or physically integrated into our primary care teams. They will assist with issues such as initial clinical assessment; coordinate initiation of a mental health treatment plan; monitor the patient’s response to treatment; provide recommendations for treatment change based on evidence-based protocols and guidance from a consulting psychiatrist; provide therapy and mental health services to patients when indicated; and work closely with the patient to engage, activate, and educate him/her in order to promote disease management and treatment adherence. A unique feature of this integration program is the creation of a network-wide mental health access line for rapid mental health assessment and advice. Third, Partners is deploying sustained, network-wide educational programs that will train primary care personnel in brief interventions for improved disease management such as motivational interviewing, behavioral activation, problem-solving therapy, and other first-line interventions suitable for a primary care setting. Fourth, all primary care practices are developing and deploying standard workflows for the identification and treatment of mental health illnesses, starting with depression. Fifth, telehealth technologies will be used to improve access to specialty care and provide care in the most cost-effective setting. An initial focus is on online cognitive behavioral therapy, with virtual visit technologies to follow. Finally, registries will track mental health outcomes and provide prompts to ensure that follow-up screening tests are administered at periodic intervals and that treatment plans can be modified if progress is insufficient.

Implementing Prayer-Agnostic Programs For Specialty Services

Historically, cost containment by commercial payers focused on limiting access to specialist services. However, since costs are concentrated in a small portion of the population with complex chronic illnesses, considering the problems caused by gatekeeping in the 1990s, limiting access to specialists for the entire population may not be an appropriate lever for lowering TME trend. In addition, enhanced access to specialty services has the potential to reduce costs and improve quality through more efficient testing and treatment regimens. We have approached specialist services with the philosophy that early and coordinated access, through the application of tools such as bi-directional referral management systems and virtual visit capabilities, will have a greater ability to lower costs. The challenge for deploying these tools is that ACOs are built off of an aligned population of patients attributed to primary care physicians. Typically, specialists in ACOs are providing care to both a fee-for-service population as well as the ACO population. The costs of providing a nonbillable service such as virtual visits is not sustainable if a large portion of the patients are not in a risk contract. We have found that integrating virtual visits and e-referrals for a limited set of a specialist’s patients poses workflow and ethical challenges. As a system with 2 prominent academic medical centers, we have therefore focused our efforts on deploying these tools to specialists who have a high proportion of patients from our primary care physicians, and continue to work through these significant challenges.

Our specialist engagement tools are focused primarily on improving access and coordination or ensuring appropriateness and optimal outcomes. First, virtual visits (asynchronous and synchronous) between patients and providers or between providers help improve access and coordination. Second, referral management systems that allow for pre-consultative communications and review with key clinical data and messages allow for more thoughtful specialist consultations. This active management of referrals allows specialists to provide accelerated “curbside” consults without a formal consult for minor issues, appropriate pre-appointment testing for improved initial in-person consultation, or accelerated scheduling for initial consultation for urgent issues. Third, we are implementing technology and workflows to capture patient-reported outcomes in our specialty practices. We are collecting and reporting this data internally and externally to ensure we are monitoring the metrics that are most important to our patients. Monitoring patient-reported outcomes is especially important when a provider is concurrently implementing cost-containment measures. Fourth, we have developed technology to assess the appropriateness of surgical procedures. This technology combines analytics of both structured and unstructured data in an electronic platform and provide feedback to providers and patients regarding relative risks and benefits of certain procedures [17]. Lastly, we are implementing clinical bundles around select surgical procedures.

As an ACO that includes academic medical centers, we have a particular challenge of balancing the mission of fostering innovative and experimental technologies that may help advance human health and medical science, while ensuring we are stewards of limited financial resources. Academic medical center–led ACOs will need to thoughtfully balance these objectives [4].

Improving Non-Acute Services

We have included both improved access to emergency department alternatives as well as a focus on the appropriate and efficient use of post acute services in our approach to non-acute services. We have approached improving access to urgent care services by both implementing standards for access to primary care (through PCMH transformation) as well as partnering with urgent care providers.

The use of post-acute care services is the main driver of hospital referral region cost variation for both Medicare and Medicaid [18]. If an ACO is taking on risk in either of these payer categories, it is imperative that the organization has a strategy for managing post-acute care. We have been developing the following capabilities:

- Determine most appropriate level of post-acute care upon discharge from an acute facility (eg, home health vs. skilled nursing facility)

- Predict, to some level of reasonable confidence, the length of post-acute services required per episode of care

- Create a high performance post-acute referral network that can meet quality, efficiency and cost standards set forth by the ACO

The challenge in meeting these goals include the lack of high quality data required to execute on the first 2 objectives. In addition, development of a post-acute referral network is dependent on regional market characteristics. For example, if the region’s supply of post-acute facilities is limited, enforcing the ACO standards for high-quality post-acute care may be challenging. Executing a post-acute strategy that helps an ACO meet its financial and quality objectives may be one of the more challenging endeavors the ACO will undertake.

Engaging Patients in Accountable Care

Accountable care contracts provide a new imperative for providers to offer tools that help patients engage in their care outside of the traditional clinical encounter. Promoting shared decision making, where patients share preferences and clinicians incorporate these beliefs into clinical decision-making, is one of our primary patient engagement strategies. Systematic reviews have demonstrated the effectiveness of shared decision making in improving patient awareness and reducing variation in health care utilization [19–21]. In addition to shared decision making, we have invested in new video education tools and have updated our electronic patient portal to allow patients to access their clinical record, review educational materials, and communicate with their care team at their convenience. Patient engagement strategies are also embedded into other initiatives, such as our high-risk care management program. Keeping patient engagement integrated into all of an accountable care organization’s programs, instead of treating it as a distinct program, is critical for success.

Implementing Clinical Information Technology Tools

A majority of current clinical information technology tools have been created for synchronous, in-person delivery of health care, reflecting the dominant mode of care delivery in the US. However, under accountable care payment models, ACOs have the opportunity (and imperative) to deliver care either asynchronously and/or remotely. As we assessed our needs, we recognized several gaps between existing and desired technologies. Though many population health information technology frameworks exist, we have found three broad categories required for successful population health management: advanced data warehousing and analytics, next generation care delivery and coordination tools, and innovative clinical performance management tools.

Advanced data warehousing and analytics: ACOs must be able to integrate and analyze multiple data sources, including payer derived claims data (providing data on care rendered both inside and outside the ACO) as well as administrative data (scheduling, billing), and clinical (both structured and unstructured). This requires an ACO to invest in data warehousing technologies and analytical tools in order to take full advantage of the available information and provide guidance to providers and managers. We continue to build this set of solutions.

Next generation care delivery and coordination tools: The ACO must have new ways to connect various members of the patient care team including patient to provider, and provider to provider. These technologies include but are not limited to asynchronous and synchronous virtual visit capabilities, referral management software and high risk care management software, and remote monitoring for carefully selected patients. We are currently employing all of these types of health information technology.

Innovative clinical performance management tools: Third, the accountable care organization should have clinical performance management technologies that allow its providers to reduce care gaps and improve stewardship of resources. This includes, for example, advanced clinical decision support for radiology ordering and procedures and patient registries with clinical workflow integration.

In general, we have found a majority of accountable care information technology vendors are repurposing their existing assets for new applications towards population health management. For example, warehousing companies with strengths in the financial industry may convert their product for the health care market, or a company built for patient outreach and appointment reminders may convert their product into population health clinical registries. Given the relatively new nature of risk-based contracting, and uncertainty of the future of this payment model, it makes good sense from a vendor perspective to first try to repurpose existing assets, instead of creating built-for-purpose technologies that are more costly, and may not get to market fast enough to meet customer needs. The challenge for providers is that many of these repurposed technologies do not quite solve the particular challenges the provider is attempting to address. Accountable care organizations therefore are faced with challenging decisions regarding the purchase of a less than optimal product, waiting for the product segment to mature, or building the solution themselves.

Conclusion

We have described an approach to ACO success that includes the creation of a sustainable financing mechanism, new incentive structures, a high-risk care management program, integrated mental health services, tools for specialist engagement, a post-acute strategy, fostering patient engagement, and new clinical and analytic technologies. The breadth and depth of these changes to care delivery present numerous daunting challenges. Our experience suggests that partial approaches, implementing just a subset of the approaches listed above, will not constrain cost growth because costs are just shifted to a different part of the care delivery system. We conclude from this experience that a comprehensive approach undertaken within a system that is capable of integrating care across the full continuum of care delivery has the best chance for successfully managing costs and improving care. Nonetheless, the challenges associated with change on this scale are legion. Key challenges facing the committed ACOs include: educating their boards and management about requirements for success as an ACO; advocacy for state and federal regulations that support the success of ACOs; and engaging patients as active participants in the changes. Importantly, financial returns (as shared savings) on the investment required for these changes will not be available within short-term contract cycles, so committed organizations will need to plan for the long haul.

Acknowledgment: The authors would like to thank the leadership of Partners Healthcare for their unambiguous support of the efforts described in this paper, as well as the clinicians, administrators, and support service workers that are committed to the achievement of the goals we have together set for the organization.

Corresponding author: Sreekanth K. Chaguturu, MD, 800 Boylston St., Ste. 1150, Boston, MA 02199, schaguturu@partners.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Modern Healthcare’s 2014 accountable care organizations survey. Accessed 13 Aug 2014 at www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20140712/DATA/500032360/accountable-care-organizations-2014-excel-full-results.

2. McCall N, Cromwell J, Urato C. Evaluation of Medicare Care Management for High Cost Beneficiaries (CMHCB) Demonstration: Massachusetts General Hospital and Massachusetts General Physicians Organization (MGH). Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2010 Sept:1–171.

3. Milford CE, Ferris TG. A modified “golden rule” for health care organizations. Mayo Clin Proc 2012;87:717–20.

4. Nabel EG, Ferris TG, Slavin PL. Balancing AMCs’ missions and health care costs – mission impossible? N Engl J Med 2013;369:994–6.

5. Torchiana DF, Colton DG, Rao SK, et al. Massachusetts General Physicians Organization’s quality incentive program produces encouraging results. Health Aff 2013;32:1748–56.

6. Hong CS, Abrams MK, Ferris TG. Toward increased adoption of complex care management. N Engl J Med 2014;371:491–3.

7. Hong CS, Siegel AL, Ferris TG. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients: what makes for a successful care management program? Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 2014;19:1–19.

8. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:617–27.

9. Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, et al. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2515–23.

10. Druss BG, Walker ER. Mental disorders and medical comorbidity. Research synthesis report no. 21. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2011.

11. Melek S, Norris D. Chronic conditions and comorbid psychological disorders. Milliman Research Report. Seattle, WA: Milliman; 2008.

12. Leslie DL, Rosenbeck RA. Comparing quality of mental health care for public-sector and privately insured populations. Psychiatr Serv 2000; 51:650–5.

13. Goldman W. Economic grand rounds: is there a shortage of psychiatrists? Psychiatr Serv 2001;52:1587–9.

14. Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, et al. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:2314–21.

15. Woltmann E, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron B, et al. Comparative effectiveness of collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions across primary, specialty, and behavioral health care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 2012;169:790–804.

16. Bower P, Gilbody S, Richards D, et al. Collaborative care for depression in primary care, making sense of a complex intervention: systematic review and meta-regression. Br J Psychiatry 2006;189:484–93.

17. Milford CE, Hutter MM, Lillemoe KD, Ferris TG. Optimizing appropriate use of procedures in an era of payment reform. Ann Surg 2014;260:204–4.

18. Geographic variation in spending, utilization and quality: Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. May 2013. Accessed 13 Aug 2014 at http://iom.edu/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2013/Geographic-Variation/Sub-Contractor/Acumen-Medicare-Medicaid.pdf

19. Stacey D, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(10)CD001431.

20. Oshima Lee E, Emanuel EJ. Shared decision making to improve care and reduce costs. N Engl J Med 2013;368:6–8.

21. Arterburn D, Wellman R, Westbrook E, et al. Introducing decision aids at Group Health was linked to sharply lower hip and knee surgery rates and costs. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:2094–104.

From Partners HealthCare, Boston, MA.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe operational lessons from a large accountable care organization (ACO).

- Methods: Description of an approach that includes the creation of a sustainable financing mechanism, new incentive structures, a high risk care management program, integrated mental health services, tools for specialist engagement, a post acute strategy, fostering patient engagement, and new clinical and analytic technologies.

- Results: Committed ACOs face challenges in enacting care delivery changes. Key challenges include educating boards and management about requirements for success as an ACO; advocacy for state and federal regulations that support the success of ACOs; and engaging patients as active participants in the changes. Importantly, financial returns (as shared savings) on the investment required for these changes will not be available within short-term contract cycles, so committed organizations will need to plan for the long haul.

- Conclusion: A comprehensive approach undertaken within a system that is capable of integrating care across the full continuum of care delivery has the best chance for successfully managing costs and improving care.

After Massachusetts enacted legislation expanding health insurance to nearly all residents in 2006, additional legislation was enacted that focused on health cost containment. The goal of the many new regulations has been to hold the rate of health care cost growth to the rate of general inflation. Consistent with payment policy changes under the Accountable Care Act, Massachusetts regulatory efforts have emphasized putting health care providers at financial risk for some proportion of increases in costs of care. Providers who contract as accountable care organizations (ACOs) typically conduct their usual fee-for-service billing practices, but in addition the providers also agree to an annual total medical expenses (TME) spending target for an assigned population of patients. An annual reconciliation results in either penalties for exceeding targets or shared savings if spending remains below the target. The reconciliation incorporates a small number of commonly used primary care quality measures.

Partners HealthCare, an integrated health care delivery system in Massachusetts that includes 2 large academic medical centers—Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH)—began deploying new care models designed to reduce the growth in health care costs prior to these policy changes, but the new contracting environment has dramatically accelerated these efforts. Partners HealthCare signed accountable care risk contracts across all major payer categories—commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid—in 2011. Currently, Partners HealthCare has accountability for cost increases for nearly 500,000 lives, making it one of the largest providers of accountable care in the United States [1].

In this paper, we describe some of the initial lessons learned and share some of our concerns for the future success of risk-based contracting. We have organized the paper as we have organized our work—addressing different care services by site of care: primary care, specialty care, non-acute care, patient engagement, and necessary infrastructure. This framework has allowed us to engage the care providers throughout our organization with programs tailored to their specific circumstances. While practical, this framework is nonetheless somewhat artificial because much of our work could be characterized as building bridges between sites of care.

Organizing System-Wide ACO Programs

Focused efforts to lower cost trends and improve outcomes for a defined population began with MGH’s participation in a Medicare demonstration project in 2006. This successful program assigned specially trained nurse care managers to over 2000 of MGH’s highest cost Medicare beneficiaries [2]. The program was expanded in 2009 and then again in 2012, and now includes the entire Partners system. Building on this success, Partners’ providers evolved a broader set of tactics to include data, measurement and evidence-based methods of improving access, continuity, and care coordination to provide population-based health care [3,4]. To coordinate the system-wide work required by new risk contracting arrangements, Partners created the Division of Population Health Management (PHM). PHM works closely with organizational leadership at member institutions to collaboratively design and execute its system-wide accountable care strategy.

PHM has developed capacity, infrastructure, and expertise to implement and manage a clinical strategy for the entire integrated delivery system. This included some governance changes, new management processes, new investments in information technology and establishing system-wide incentives to promote care delivery innovation and improvement. Most importantly, through an extensive planning process Partners identified a comprehensive set of tactics and a multi-year plan for system-wide adoption of those tactics.

The majority of Partners information infrastructure to date was built internally, which allowed for rapid customization and flexibility, but also created significant interoperability problems. Moving forward, the majority of Partners systems will use a single IT platform. Partners has developed and implemented patient registries and care management decision support tools to help focus provider attention on patients most in need of interventions and to support reporting of quality metrics. In addition, Partners continues to expand a comprehensive data warehouse that incorporates a variety of clinical, administrative, and financial data sources to support advanced analytics for self-monitoring and continuous improvement. This extensive network-wide approach over the past several years has generated a number of lessons regarding successful accountable care organization implementation.

Implementing New Financing and Incentive Structures

Once an ACO is formed, the organization needs to restructure management to create organizational accountability for performance (as noted above), determine how to finance programmatic initiatives required to deliver the performance called for in the contracts, and create incentives for all the different providers within the ACO to drive performance towards the system’s goals. These latter two require the ACO to make specific design choices that include some trade-offs.

Partners chose to fund system-level population health management initiatives through a tax on net patient service revenue from its member providers—both hospitals and physicians. Alternative approaches include either setting aside a yearly allocation that is not proportional to a revenue stream or simply allocating the external risk to different operating units and allowing them to determine their own individual approaches (and investments) to managing the financial risk. By linking financing of PHM programs to clinical revenue (independent of risk contracts), and setting a uniform percentage tax, Partners has signaled that the wealthier parts of the system will contribute more to PHM (on an absolute basis) and more importantly that accountable care is a prioritized long-term investment. Allowing each entity within the organization to “sink or swim” based on its own performance was considered inconsistent with the interdependent nature of care delivery in a well functioning system. In addition, investments in the required infrastructure cannot be dependent on annual contract performance due to the volatility in contracted performance and the time it takes for an organization to get a return on their PHM investment.

Any organization involved in multiple performance based risk contracts faces the challenge of organizing the tactics and metrics for their providers. It is simply inconsistent with provider values and workflow to manage to different targets for different subpopulations of patients. In our attempts to promote the best possible care for all our patients and at the same time meet the demands of multiple external contract requirements, we have created an internal performance framework (IPF) that uses a single set of performance targets and a single incentive pool for all out contracts. The IPF rewards member institutions for (1) adopting programmatic initiatives (funded through the tax as described above), (2) meeting external quality measure targets, and (3) limiting the growth of cost-standardized medical expense trend (Figure).

Fixing Primary Care

Populations in risk contracts are typically defined by their primary care providers. In addition, the chronic underfunding of primary care in the US has resulted in unsustainable practice environments as well as well known access problems. Finally, the concentration of costs in a relatively small proportion of patients provides the greatest opportunity for ACOs to reduce costs through better care coordination for these patients. This core set of facts has guided our efforts to improve primary care. To address these issues, we have increased funding to primary care through our efforts to certify all 236 practices as patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs). In addition, we have begun transitioning our compensation models to include components based on risk-adjusted panel size and performance on quality metrics. As mentioned above, we have invested heavily in our complex care management program. Finally, we are working on a much tighter integration of mental health services with primary care. In this section we focus on lessons from our care management program and our efforts in mental health integration.

Complex Care Management

Provider-led high-risk care management has become the primary clinical lever for cost containment for most accountable care organizations [6]. The design and operational characteristics or our program have been described by Hong et al and are available on our website. Our decade of experience with this program has taught us a few lessons regarding the use of algorithms to identify patients, the management of program costs, and the difficulty of creating meaningful accountability.

Our analysis of commercially available risk prediction algorithms found minimal differences among the various products’ ability to predict high cost patients in the following year. A majority of the algorithms are exclusively claims based, though some include the ability to augment risk predictions with clinical data. Clinicians have played a critical role in improving our ability to identify high-risk patients. We have found that when physicians review a pre-selected set of their own patients, they have some ability to discriminate among patients who are likely to benefit from care management and those who are not. Clinicians are prone to overemphasizing recent events, but review of a list of patients who are predicted of becoming high cost mitigates this problem. Commercially available algorithms can help create an initial list, but physicians can add perspective on such important factors as social support and executive functioning. This additional information improves the specificity of the initial algorithm outputs, allowing clinicians to play an important role in refining the lists of patients eligible for high-risk care management.

The high cost of labor and space make high-risk care management programs among the most costly programs for an ACO. Care management requires a skilled nursing workforce (among others), which should be embedded into the primary care office for optimal effect [6,7].Given the high costs, there is understandable pressure to increase the ratio of patients per care manager. We have found that the optimal ratio is approximately 200 patients per care manager, with a third of the patients having active complex care management issues, a third being passively surveyed, and a third requiring modest care coordination. We continue with our attempts to refine how we manage this critical aspect of care management programs.

How can managers demonstrate that the investment in care coordination is impacting the ACO’s TME trend? Demonstrating a return on investment is difficult because a population of high-cost patients will inevitably show reduced costs in the following year (a phenomenon called regression to the mean). Isolating a well-matched control group to demonstrate program effectiveness would have the unintended consequence of reducing the potential effectiveness of the program. This situation is complicated by the different risk profiles of high-risk patients in different payer categories. For example, potentially avoidable Medicare costs are dominated by hospitalizations and end-of-life issues, Medicaid costs by mental illness and substance abuse, and commercial costs by specialty issues. In lieu of better management tools to assess the performance of our program, we have depended to date on process measures (eg., enrollment targets), patient surveys, and we are experimenting with some limited outcomes metrics (eg, admissions/1000).

Mental Health Integration

Another important lever for medical trend reduction within an ACO is the integration of mental health services into primary care. While our efforts in this complex area are only about a year old, some of our early lessons may prove valuable to others. First, we have worked hard to make the case for investment in mental health services, requiring assembling the evidence both for the magnitude of the problem as well as the effectiveness of available solutions.

A quarter of American adults suffer from diagnosable mental health disorders every year and it is estimated that PCPs manage between 40% and 80% of these patients [8,9].Rates of detection and adequate treatment in primary care settings are currently suboptimal, leading to poor disease management and driving excess utilization. Using claims data within the Partners’ primary care population, we have found medical expenditures are 45% higher for patients with a mental health diagnosis. Over 70% of mental health patients have additional illnesses, and the presence of a mental health disorder complicates overall clinical management [10].This results in a substantial increase in medical cost, independent of psychiatric medical spending [11].In addition, psychiatry shortage and access have become a major issue in mental health services [12].Over 70% of PCPs nationwide reported difficulty in finding high-quality outpatient mental health care for their patients [13].

The dominant clinical model for mental health integration is the collaborative care model (CCM), and evidence for its effectiveness is growing. Randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses have shown that CCMs are successful at improving detection and treatment of mental health disorders [14–16].Cost-savings analyses for many of these programs demonstrate considerable savings and favorable return on investment (ROI). Several CCMs that use nonmedical specialists and consulting psychiatrists to augment the management of mental health disorders for low- to moderate-risk primary care patients have been implemented. However, a majority of the CCMs are disease-specific—eg, integrating depression treatment resources into primary care. The challenge for ACOs is to determine how to build a comprehensive CCM that helps primary care manage the major primary care–based mental health conditions—depression, anxiety and substance abuse—in a coordinated, cost-efficient model. The ACO must consider how to implement both its high-risk program and its CCM programs in a way that is not disruptive but supportive to primary care practices.

Partners is implementing a multipronged strategy to address mental health issues within primary care. First, a universal screening program for mental health disorders using brief, well-validated screening tools (eg, Patient Health Questionnaire 2 and 9) will improve the identification of patients with mental health disorders. Second, consulting psychiatrist and mid-level health care providers, functioning as mental health specialists, will be virtually or physically integrated into our primary care teams. They will assist with issues such as initial clinical assessment; coordinate initiation of a mental health treatment plan; monitor the patient’s response to treatment; provide recommendations for treatment change based on evidence-based protocols and guidance from a consulting psychiatrist; provide therapy and mental health services to patients when indicated; and work closely with the patient to engage, activate, and educate him/her in order to promote disease management and treatment adherence. A unique feature of this integration program is the creation of a network-wide mental health access line for rapid mental health assessment and advice. Third, Partners is deploying sustained, network-wide educational programs that will train primary care personnel in brief interventions for improved disease management such as motivational interviewing, behavioral activation, problem-solving therapy, and other first-line interventions suitable for a primary care setting. Fourth, all primary care practices are developing and deploying standard workflows for the identification and treatment of mental health illnesses, starting with depression. Fifth, telehealth technologies will be used to improve access to specialty care and provide care in the most cost-effective setting. An initial focus is on online cognitive behavioral therapy, with virtual visit technologies to follow. Finally, registries will track mental health outcomes and provide prompts to ensure that follow-up screening tests are administered at periodic intervals and that treatment plans can be modified if progress is insufficient.

Implementing Prayer-Agnostic Programs For Specialty Services

Historically, cost containment by commercial payers focused on limiting access to specialist services. However, since costs are concentrated in a small portion of the population with complex chronic illnesses, considering the problems caused by gatekeeping in the 1990s, limiting access to specialists for the entire population may not be an appropriate lever for lowering TME trend. In addition, enhanced access to specialty services has the potential to reduce costs and improve quality through more efficient testing and treatment regimens. We have approached specialist services with the philosophy that early and coordinated access, through the application of tools such as bi-directional referral management systems and virtual visit capabilities, will have a greater ability to lower costs. The challenge for deploying these tools is that ACOs are built off of an aligned population of patients attributed to primary care physicians. Typically, specialists in ACOs are providing care to both a fee-for-service population as well as the ACO population. The costs of providing a nonbillable service such as virtual visits is not sustainable if a large portion of the patients are not in a risk contract. We have found that integrating virtual visits and e-referrals for a limited set of a specialist’s patients poses workflow and ethical challenges. As a system with 2 prominent academic medical centers, we have therefore focused our efforts on deploying these tools to specialists who have a high proportion of patients from our primary care physicians, and continue to work through these significant challenges.

Our specialist engagement tools are focused primarily on improving access and coordination or ensuring appropriateness and optimal outcomes. First, virtual visits (asynchronous and synchronous) between patients and providers or between providers help improve access and coordination. Second, referral management systems that allow for pre-consultative communications and review with key clinical data and messages allow for more thoughtful specialist consultations. This active management of referrals allows specialists to provide accelerated “curbside” consults without a formal consult for minor issues, appropriate pre-appointment testing for improved initial in-person consultation, or accelerated scheduling for initial consultation for urgent issues. Third, we are implementing technology and workflows to capture patient-reported outcomes in our specialty practices. We are collecting and reporting this data internally and externally to ensure we are monitoring the metrics that are most important to our patients. Monitoring patient-reported outcomes is especially important when a provider is concurrently implementing cost-containment measures. Fourth, we have developed technology to assess the appropriateness of surgical procedures. This technology combines analytics of both structured and unstructured data in an electronic platform and provide feedback to providers and patients regarding relative risks and benefits of certain procedures [17]. Lastly, we are implementing clinical bundles around select surgical procedures.

As an ACO that includes academic medical centers, we have a particular challenge of balancing the mission of fostering innovative and experimental technologies that may help advance human health and medical science, while ensuring we are stewards of limited financial resources. Academic medical center–led ACOs will need to thoughtfully balance these objectives [4].

Improving Non-Acute Services

We have included both improved access to emergency department alternatives as well as a focus on the appropriate and efficient use of post acute services in our approach to non-acute services. We have approached improving access to urgent care services by both implementing standards for access to primary care (through PCMH transformation) as well as partnering with urgent care providers.

The use of post-acute care services is the main driver of hospital referral region cost variation for both Medicare and Medicaid [18]. If an ACO is taking on risk in either of these payer categories, it is imperative that the organization has a strategy for managing post-acute care. We have been developing the following capabilities:

- Determine most appropriate level of post-acute care upon discharge from an acute facility (eg, home health vs. skilled nursing facility)

- Predict, to some level of reasonable confidence, the length of post-acute services required per episode of care

- Create a high performance post-acute referral network that can meet quality, efficiency and cost standards set forth by the ACO

The challenge in meeting these goals include the lack of high quality data required to execute on the first 2 objectives. In addition, development of a post-acute referral network is dependent on regional market characteristics. For example, if the region’s supply of post-acute facilities is limited, enforcing the ACO standards for high-quality post-acute care may be challenging. Executing a post-acute strategy that helps an ACO meet its financial and quality objectives may be one of the more challenging endeavors the ACO will undertake.

Engaging Patients in Accountable Care

Accountable care contracts provide a new imperative for providers to offer tools that help patients engage in their care outside of the traditional clinical encounter. Promoting shared decision making, where patients share preferences and clinicians incorporate these beliefs into clinical decision-making, is one of our primary patient engagement strategies. Systematic reviews have demonstrated the effectiveness of shared decision making in improving patient awareness and reducing variation in health care utilization [19–21]. In addition to shared decision making, we have invested in new video education tools and have updated our electronic patient portal to allow patients to access their clinical record, review educational materials, and communicate with their care team at their convenience. Patient engagement strategies are also embedded into other initiatives, such as our high-risk care management program. Keeping patient engagement integrated into all of an accountable care organization’s programs, instead of treating it as a distinct program, is critical for success.

Implementing Clinical Information Technology Tools

A majority of current clinical information technology tools have been created for synchronous, in-person delivery of health care, reflecting the dominant mode of care delivery in the US. However, under accountable care payment models, ACOs have the opportunity (and imperative) to deliver care either asynchronously and/or remotely. As we assessed our needs, we recognized several gaps between existing and desired technologies. Though many population health information technology frameworks exist, we have found three broad categories required for successful population health management: advanced data warehousing and analytics, next generation care delivery and coordination tools, and innovative clinical performance management tools.

Advanced data warehousing and analytics: ACOs must be able to integrate and analyze multiple data sources, including payer derived claims data (providing data on care rendered both inside and outside the ACO) as well as administrative data (scheduling, billing), and clinical (both structured and unstructured). This requires an ACO to invest in data warehousing technologies and analytical tools in order to take full advantage of the available information and provide guidance to providers and managers. We continue to build this set of solutions.

Next generation care delivery and coordination tools: The ACO must have new ways to connect various members of the patient care team including patient to provider, and provider to provider. These technologies include but are not limited to asynchronous and synchronous virtual visit capabilities, referral management software and high risk care management software, and remote monitoring for carefully selected patients. We are currently employing all of these types of health information technology.

Innovative clinical performance management tools: Third, the accountable care organization should have clinical performance management technologies that allow its providers to reduce care gaps and improve stewardship of resources. This includes, for example, advanced clinical decision support for radiology ordering and procedures and patient registries with clinical workflow integration.

In general, we have found a majority of accountable care information technology vendors are repurposing their existing assets for new applications towards population health management. For example, warehousing companies with strengths in the financial industry may convert their product for the health care market, or a company built for patient outreach and appointment reminders may convert their product into population health clinical registries. Given the relatively new nature of risk-based contracting, and uncertainty of the future of this payment model, it makes good sense from a vendor perspective to first try to repurpose existing assets, instead of creating built-for-purpose technologies that are more costly, and may not get to market fast enough to meet customer needs. The challenge for providers is that many of these repurposed technologies do not quite solve the particular challenges the provider is attempting to address. Accountable care organizations therefore are faced with challenging decisions regarding the purchase of a less than optimal product, waiting for the product segment to mature, or building the solution themselves.

Conclusion

We have described an approach to ACO success that includes the creation of a sustainable financing mechanism, new incentive structures, a high-risk care management program, integrated mental health services, tools for specialist engagement, a post-acute strategy, fostering patient engagement, and new clinical and analytic technologies. The breadth and depth of these changes to care delivery present numerous daunting challenges. Our experience suggests that partial approaches, implementing just a subset of the approaches listed above, will not constrain cost growth because costs are just shifted to a different part of the care delivery system. We conclude from this experience that a comprehensive approach undertaken within a system that is capable of integrating care across the full continuum of care delivery has the best chance for successfully managing costs and improving care. Nonetheless, the challenges associated with change on this scale are legion. Key challenges facing the committed ACOs include: educating their boards and management about requirements for success as an ACO; advocacy for state and federal regulations that support the success of ACOs; and engaging patients as active participants in the changes. Importantly, financial returns (as shared savings) on the investment required for these changes will not be available within short-term contract cycles, so committed organizations will need to plan for the long haul.

Acknowledgment: The authors would like to thank the leadership of Partners Healthcare for their unambiguous support of the efforts described in this paper, as well as the clinicians, administrators, and support service workers that are committed to the achievement of the goals we have together set for the organization.

Corresponding author: Sreekanth K. Chaguturu, MD, 800 Boylston St., Ste. 1150, Boston, MA 02199, schaguturu@partners.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

From Partners HealthCare, Boston, MA.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe operational lessons from a large accountable care organization (ACO).

- Methods: Description of an approach that includes the creation of a sustainable financing mechanism, new incentive structures, a high risk care management program, integrated mental health services, tools for specialist engagement, a post acute strategy, fostering patient engagement, and new clinical and analytic technologies.

- Results: Committed ACOs face challenges in enacting care delivery changes. Key challenges include educating boards and management about requirements for success as an ACO; advocacy for state and federal regulations that support the success of ACOs; and engaging patients as active participants in the changes. Importantly, financial returns (as shared savings) on the investment required for these changes will not be available within short-term contract cycles, so committed organizations will need to plan for the long haul.

- Conclusion: A comprehensive approach undertaken within a system that is capable of integrating care across the full continuum of care delivery has the best chance for successfully managing costs and improving care.

After Massachusetts enacted legislation expanding health insurance to nearly all residents in 2006, additional legislation was enacted that focused on health cost containment. The goal of the many new regulations has been to hold the rate of health care cost growth to the rate of general inflation. Consistent with payment policy changes under the Accountable Care Act, Massachusetts regulatory efforts have emphasized putting health care providers at financial risk for some proportion of increases in costs of care. Providers who contract as accountable care organizations (ACOs) typically conduct their usual fee-for-service billing practices, but in addition the providers also agree to an annual total medical expenses (TME) spending target for an assigned population of patients. An annual reconciliation results in either penalties for exceeding targets or shared savings if spending remains below the target. The reconciliation incorporates a small number of commonly used primary care quality measures.

Partners HealthCare, an integrated health care delivery system in Massachusetts that includes 2 large academic medical centers—Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH)—began deploying new care models designed to reduce the growth in health care costs prior to these policy changes, but the new contracting environment has dramatically accelerated these efforts. Partners HealthCare signed accountable care risk contracts across all major payer categories—commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid—in 2011. Currently, Partners HealthCare has accountability for cost increases for nearly 500,000 lives, making it one of the largest providers of accountable care in the United States [1].

In this paper, we describe some of the initial lessons learned and share some of our concerns for the future success of risk-based contracting. We have organized the paper as we have organized our work—addressing different care services by site of care: primary care, specialty care, non-acute care, patient engagement, and necessary infrastructure. This framework has allowed us to engage the care providers throughout our organization with programs tailored to their specific circumstances. While practical, this framework is nonetheless somewhat artificial because much of our work could be characterized as building bridges between sites of care.

Organizing System-Wide ACO Programs

Focused efforts to lower cost trends and improve outcomes for a defined population began with MGH’s participation in a Medicare demonstration project in 2006. This successful program assigned specially trained nurse care managers to over 2000 of MGH’s highest cost Medicare beneficiaries [2]. The program was expanded in 2009 and then again in 2012, and now includes the entire Partners system. Building on this success, Partners’ providers evolved a broader set of tactics to include data, measurement and evidence-based methods of improving access, continuity, and care coordination to provide population-based health care [3,4]. To coordinate the system-wide work required by new risk contracting arrangements, Partners created the Division of Population Health Management (PHM). PHM works closely with organizational leadership at member institutions to collaboratively design and execute its system-wide accountable care strategy.

PHM has developed capacity, infrastructure, and expertise to implement and manage a clinical strategy for the entire integrated delivery system. This included some governance changes, new management processes, new investments in information technology and establishing system-wide incentives to promote care delivery innovation and improvement. Most importantly, through an extensive planning process Partners identified a comprehensive set of tactics and a multi-year plan for system-wide adoption of those tactics.

The majority of Partners information infrastructure to date was built internally, which allowed for rapid customization and flexibility, but also created significant interoperability problems. Moving forward, the majority of Partners systems will use a single IT platform. Partners has developed and implemented patient registries and care management decision support tools to help focus provider attention on patients most in need of interventions and to support reporting of quality metrics. In addition, Partners continues to expand a comprehensive data warehouse that incorporates a variety of clinical, administrative, and financial data sources to support advanced analytics for self-monitoring and continuous improvement. This extensive network-wide approach over the past several years has generated a number of lessons regarding successful accountable care organization implementation.

Implementing New Financing and Incentive Structures

Once an ACO is formed, the organization needs to restructure management to create organizational accountability for performance (as noted above), determine how to finance programmatic initiatives required to deliver the performance called for in the contracts, and create incentives for all the different providers within the ACO to drive performance towards the system’s goals. These latter two require the ACO to make specific design choices that include some trade-offs.

Partners chose to fund system-level population health management initiatives through a tax on net patient service revenue from its member providers—both hospitals and physicians. Alternative approaches include either setting aside a yearly allocation that is not proportional to a revenue stream or simply allocating the external risk to different operating units and allowing them to determine their own individual approaches (and investments) to managing the financial risk. By linking financing of PHM programs to clinical revenue (independent of risk contracts), and setting a uniform percentage tax, Partners has signaled that the wealthier parts of the system will contribute more to PHM (on an absolute basis) and more importantly that accountable care is a prioritized long-term investment. Allowing each entity within the organization to “sink or swim” based on its own performance was considered inconsistent with the interdependent nature of care delivery in a well functioning system. In addition, investments in the required infrastructure cannot be dependent on annual contract performance due to the volatility in contracted performance and the time it takes for an organization to get a return on their PHM investment.

Any organization involved in multiple performance based risk contracts faces the challenge of organizing the tactics and metrics for their providers. It is simply inconsistent with provider values and workflow to manage to different targets for different subpopulations of patients. In our attempts to promote the best possible care for all our patients and at the same time meet the demands of multiple external contract requirements, we have created an internal performance framework (IPF) that uses a single set of performance targets and a single incentive pool for all out contracts. The IPF rewards member institutions for (1) adopting programmatic initiatives (funded through the tax as described above), (2) meeting external quality measure targets, and (3) limiting the growth of cost-standardized medical expense trend (Figure).

Fixing Primary Care

Populations in risk contracts are typically defined by their primary care providers. In addition, the chronic underfunding of primary care in the US has resulted in unsustainable practice environments as well as well known access problems. Finally, the concentration of costs in a relatively small proportion of patients provides the greatest opportunity for ACOs to reduce costs through better care coordination for these patients. This core set of facts has guided our efforts to improve primary care. To address these issues, we have increased funding to primary care through our efforts to certify all 236 practices as patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs). In addition, we have begun transitioning our compensation models to include components based on risk-adjusted panel size and performance on quality metrics. As mentioned above, we have invested heavily in our complex care management program. Finally, we are working on a much tighter integration of mental health services with primary care. In this section we focus on lessons from our care management program and our efforts in mental health integration.

Complex Care Management

Provider-led high-risk care management has become the primary clinical lever for cost containment for most accountable care organizations [6]. The design and operational characteristics or our program have been described by Hong et al and are available on our website. Our decade of experience with this program has taught us a few lessons regarding the use of algorithms to identify patients, the management of program costs, and the difficulty of creating meaningful accountability.

Our analysis of commercially available risk prediction algorithms found minimal differences among the various products’ ability to predict high cost patients in the following year. A majority of the algorithms are exclusively claims based, though some include the ability to augment risk predictions with clinical data. Clinicians have played a critical role in improving our ability to identify high-risk patients. We have found that when physicians review a pre-selected set of their own patients, they have some ability to discriminate among patients who are likely to benefit from care management and those who are not. Clinicians are prone to overemphasizing recent events, but review of a list of patients who are predicted of becoming high cost mitigates this problem. Commercially available algorithms can help create an initial list, but physicians can add perspective on such important factors as social support and executive functioning. This additional information improves the specificity of the initial algorithm outputs, allowing clinicians to play an important role in refining the lists of patients eligible for high-risk care management.

The high cost of labor and space make high-risk care management programs among the most costly programs for an ACO. Care management requires a skilled nursing workforce (among others), which should be embedded into the primary care office for optimal effect [6,7].Given the high costs, there is understandable pressure to increase the ratio of patients per care manager. We have found that the optimal ratio is approximately 200 patients per care manager, with a third of the patients having active complex care management issues, a third being passively surveyed, and a third requiring modest care coordination. We continue with our attempts to refine how we manage this critical aspect of care management programs.

How can managers demonstrate that the investment in care coordination is impacting the ACO’s TME trend? Demonstrating a return on investment is difficult because a population of high-cost patients will inevitably show reduced costs in the following year (a phenomenon called regression to the mean). Isolating a well-matched control group to demonstrate program effectiveness would have the unintended consequence of reducing the potential effectiveness of the program. This situation is complicated by the different risk profiles of high-risk patients in different payer categories. For example, potentially avoidable Medicare costs are dominated by hospitalizations and end-of-life issues, Medicaid costs by mental illness and substance abuse, and commercial costs by specialty issues. In lieu of better management tools to assess the performance of our program, we have depended to date on process measures (eg., enrollment targets), patient surveys, and we are experimenting with some limited outcomes metrics (eg, admissions/1000).

Mental Health Integration

Another important lever for medical trend reduction within an ACO is the integration of mental health services into primary care. While our efforts in this complex area are only about a year old, some of our early lessons may prove valuable to others. First, we have worked hard to make the case for investment in mental health services, requiring assembling the evidence both for the magnitude of the problem as well as the effectiveness of available solutions.

A quarter of American adults suffer from diagnosable mental health disorders every year and it is estimated that PCPs manage between 40% and 80% of these patients [8,9].Rates of detection and adequate treatment in primary care settings are currently suboptimal, leading to poor disease management and driving excess utilization. Using claims data within the Partners’ primary care population, we have found medical expenditures are 45% higher for patients with a mental health diagnosis. Over 70% of mental health patients have additional illnesses, and the presence of a mental health disorder complicates overall clinical management [10].This results in a substantial increase in medical cost, independent of psychiatric medical spending [11].In addition, psychiatry shortage and access have become a major issue in mental health services [12].Over 70% of PCPs nationwide reported difficulty in finding high-quality outpatient mental health care for their patients [13].

The dominant clinical model for mental health integration is the collaborative care model (CCM), and evidence for its effectiveness is growing. Randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses have shown that CCMs are successful at improving detection and treatment of mental health disorders [14–16].Cost-savings analyses for many of these programs demonstrate considerable savings and favorable return on investment (ROI). Several CCMs that use nonmedical specialists and consulting psychiatrists to augment the management of mental health disorders for low- to moderate-risk primary care patients have been implemented. However, a majority of the CCMs are disease-specific—eg, integrating depression treatment resources into primary care. The challenge for ACOs is to determine how to build a comprehensive CCM that helps primary care manage the major primary care–based mental health conditions—depression, anxiety and substance abuse—in a coordinated, cost-efficient model. The ACO must consider how to implement both its high-risk program and its CCM programs in a way that is not disruptive but supportive to primary care practices.