User login

Vertigo: Diagnosis and Management

CE/CME No: CR-1312

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Explain the incidence, predisposing factors, and pathophysiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV).

• Describe the typical presentation and history of symptoms in the patient with BPPV. Describe exam findings that may point to other causes of vertigo/dizziness.

• Describe how to perform the Dix-Hallpike test, the Epley maneuver, and the liberatory maneuver.

• Discuss diagnosis and management of BPPV based on current clinical practice guidelines. Describe positive Dix-Hallpike test results.

• Discuss evidence-based changes in the approach to patients with vertigo that are needed in primary care and the emergency department.

FACULTY

Mary Jo Howell Collie is a family nurse practitioner at Bland County Medical Clinic in Bastian, Virginia, and serves as a preceptor for nurse practitioner students.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Article begins on next page >>

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo accounts for approximately 42% of cases of vertigo seen in primary care settings and is the single most common cause of vertigo in the United States. Our expert outlines an evidence-based approach to diagnosis, which results in an increase in desirable patient outcomes and a decrease in unnecessary tests and medications.

Dizziness is a common complaint of patients seen in both the primary care setting and the emergency department (ED). Dizziness can be classified as vertigo, disequilibrium, presyncope, and lightheadedness. Psychiatric disorders can be the cause in as many as 16% of patients who present with dizziness.1

Vestibular vertigo is the most common type of dizziness and can result from peripheral vestibular causes and central vestibular causes.1 Peripheral vestibular causes include benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), Ménière’s disease, vestibular neuronitis, labyrinthitis, vestibular schwannoma, perilymphatic fistula, superior semicircular canal dehiscence syndrome, and trauma.2 Central vestibular causes of vertigo include vestibular migraine, vertebrobasilar ischemic stroke, and vertebrobasilar insufficiency (transient ischemic attack).2 (For more information, see Pearson T. Ménière’s disease: a lifelong merry-go-round. Clinician Reviews. 2013;23[10]:38-43.)

BPPV accounts for approximately 42% of cases of vertigo in nonspecialty settings such as primary care and is the single most common cause of vertigo in the United States.3,4 Other common causes include vestibular neuritis (41% of cases), Ménière’s disease (10%), and vascular disease (3%).4

BPPV is a disorder of the inner ear that is characterized by repeated episodes of positional vertigo, a spinning sensation produced by changes in head position relative to gravity. The term benign implies a form of positional vertigo not due to any serious central nervous system (CNS) disorder and carries an overall favorable prognosis. The term paroxysmal describes the sudden and rapid onset of vertigo.4

BPPV typically involves either the posterior semicircular canal (by far the most common) or the lateral (horizontal) semicircular canal.5 BPPV involving the posterior semicircular canal comprises 85% to 95% of all cases of BPPV and is the focus of this article.6

BPPV can be diagnosed and treated by multiple clinical disciplines, and there is considerable variation in the management of BPPV across disciplines.4 Delays in diagnosis and treatment can directly affect patients’ quality of life as well as increase health care costs. Patients with BPPV often receive inappropriately prescribed medications, such as vestibular suppressants, and potentially unnecessary diagnostic tests.4,7-9 In many cases, diagnostic and treatment decisions in regard to BPPV are not guided by current evidence.4

On the next page: Epidemiology >>

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The incidence of dizziness in the general population ranges from 20% to 30%, and with every five-year increase in age, there is a 10% increase in incidence of dizziness.10 Approximately 7.5 million patients are seen in ambulatory care annually with the chief complaint of dizziness.10 Further, with the increasing age of the US population, the incidence and prevalence of dizziness, and hence, of BPPV, will likely increase over the next 20 years.

BPPV is the most common vestibular disorder across the lifespan and most commonly presents between the fifth and seventh decade of life.4 The average age of onset of BPPV is 51 years,3 and it is rarely seen in those 35 and younger without a history of head trauma. The prevalence has been reported to range from 10.7 to 64 per 100,000 population, with a lifetime prevalence of 2.4%.4,11 It is estimated that 9% of elderly patients have unrecognized BPPV and experience greater risk for falls, depression, and interference with activities of daily living as a result.12 This, in turn, can lead to increased caregiver burden, decreased family productivity with resultant costs to society, and increased risk for nursing home placement. When not properly diagnosed and treated, BPPV can lead to significant morbidity, psychosocial problems, and increased medical costs.13

One of the main causes of BPPV is head trauma. Other predisposing factors include inactivity, major surgery, acute alcoholism, and CNS disease. BPPV is idiopathic in approximately 50% to 70% of cases.6 Spontaneous remission of BPPV can occur within days to months, or it can resolve after treatment and then recur.7 The recurrence rate of BPPV has been shown to be between 50% to 56% in some studies.11

Neuhauser et al13 evaluated the burden of dizziness within the general population in Germany, screening a cross-sectional sample of 4,869 participants for moderate or severe dizziness. The researchers estimated that 1.8% of adults seek medical care annually for new symptoms of moderate or severe dizziness or vertigo, and that vestibular vertigo accounts for approximately one third of cases of dizziness and vertigo seen in the medical setting. They commented that the latter finding is in line with other studies that have estimated that more than half of cases of dizziness in the medical setting (primary care, specialty care, and ED) are diagnosed as vestibular vertigo. The researchers also found that medical consultations and hospital visits were more frequent for vestibular vertigo than for nonvestibular dizziness. They concluded that more consideration should be given in primary care to common vestibular disorders, particularly BPPV, for which inexpensive and effective treatment with positioning maneuvers can be performed in the primary care setting.13

SUBOPTIMAL MANAGEMENT OF VERTIGO AND BPPV

Although vertigo can be debilitating and significantly reduce patients’ quality of life,13 40% to 80% of cases remain unexplained and therefore go untreated.14 BPPV not only affects patients physically but can also have serious effects on their emotional well-being.15 Anxiety has been found to be associated with BPPV in some cases. It is estimated that 86% of patients with BPPV symptoms experience problems with activities of daily living and experience work absences.11

According to clinical practice guidelines developed by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAOHNS),health care costs associated with the diagnosis of BPPV alone approach $2 billion per year, and it costs approximately $2,000 per patient to arrive at a diagnosis of BPPV.4 A recent retrospective study examined 1,681 patients who presented to the ED with complaints of vertigo and dizziness over a three-year period.9 Nearly half the patients received a CT scan of the brain and head, resulting in a total cost of $988,200. However, fewer than 1% of the CTs revealed an underlying condition that required intervention. The researchers concluded that, for patients presenting with isolated dizziness, lightheadedness, or vertigo without other symptoms, the likelihood of finding an acute life-threatening abnormality on CT is low, and therefore CT is not helpful.

Newman-Toker et al8 studied 9,472 dizzy patients who visited the ED over a 13-year period; of the 7.4% who were diagnosed with a vestibular disorder, 84% had BPPV or acute peripheral vestibulopathy.8 Patients diagnosed with BPPV were more likely to undergo diagnostic imaging with CT and more likely to receive a prescription for the vestibular suppressant meclizine than nondizzy patients. The researchers concluded that these patients were not managed optimally, citing overuse of diagnostic imaging and prescription meclizine, which is not indicated for treating BPPV.8

The use of unnecessary diagnostic testing for the work-up of vertigo has been well documented in the literature. However, the trend of diagnostic imaging for vertigo and dizziness has continued, imposing an economic burden on the health care system. The reason for this may be twofold. First, primary care and ED providers may not feel confident in their ability to recognize and diagnose BPPV. Second, an underlying component may be the clinician’s perceived need to practice defensive medicine.

A report published by the Department of Health and Human Services included a physician survey regarding litigation.16 Of those surveyed, 79% responded that they had ordered more tests than they felt were needed, due to the fear of being sued. By extrapolation, it is reasonable to assume that similar practices and concerns may apply to nurse practitioners, of whom 70% to 80% work in primary care,17 as well as physician assistants in primary care.

Although medications are used frequently for treating dizziness, this practice is not supported by evidence-based criteria.7 Overuse of vestibular suppressants for treatment of BPPV has been identified in the literature in both primary care settings and the ED; in particular, use of meclizine for treatment of dizziness and vertigo needs to be reconsidered.4,8

On the next page: Pathophysiology and patient presentation >>

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

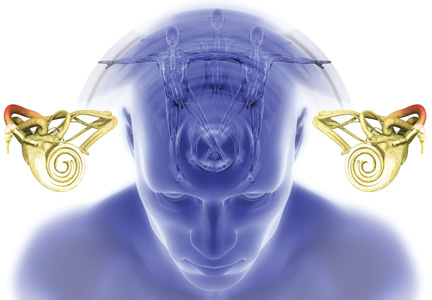

BPPV most commonly is believed to result from calcium carbonate and protein crystals called otoconia becoming dislodged from the inner ear (utricle) and settling in one of the semicircular canals (most commonly the posterior); this theory is known as canalithiasis.18 When the patient moves certain ways, the otoconia shift and cause an abnormal stimulation of the motion sensor in the affected ear. This stimulation causes conflicting signals from the two labyrinths of the inner ear, resulting in brief, intense sensations of vertigo.18 A video describing the pathophysiology is available at www.youtube.com/watch?v=gDOrltSBvKI.

PATIENT PRESENTATION AND HISTORY

The patient’s description of symptoms is critical in the work-up for dizziness. It is important to ask patients to describe their symptoms using words other than “dizzy,” as the meaning of the word may vary from person to person.10

Dizziness includes a variety of symptoms such as vertigo, unsteadiness, weakness, presyncope, syncope, lightheadedness, or falling. Vertigo is the illusion of a rotational movement of one’s self or surroundings, a spinning sensation.19 True vertigo is most likely due to peripheral vestibular disorders. Complaints of disequilibrium and ataxia point to central pathology.2 Nonvertigo symptoms—generalized weakness, lightheadedness, imbalance, unsteadiness, and tilting sensations—can point to CNS, cardiovascular, and systemic diseases and require further investigation.4,10,18

A complete health history, including medications and assessing for head trauma, ear disease, or surgery, can be helpful in rendering a diagnosis. Patients should also be questioned about caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol use. A patient-centered questionnaire can be developed to guide the clinician in obtaining a thorough history of the patient’s perceptions of his/her symptoms. An important question to ask is, “Do you get dizzy when rolling over in bed?” A “yes” answer to this question raises the clinical suspicion for BPPV.

A typical description of BPPV symptoms includes a brief episode (less than a minute) of intense vertigo that can be brought about by positional changes associated with everyday activities such as rolling over in bed, tilting the head to look upward (eg, to place an object on a shelf higher than the head), or bending forward at the waist (eg, to tie shoes).4,18 This vertigo may occur frequently for weeks, disappear for months, and then begin again. Some patients may report that they were dizzy for hours or all day. On further questioning, however, the clinician may determine that the dizziness actually occurred in short, intense episodes,which, due to their severity, may be perceived as lasting longer than a minute.18 Commonly, patients may report periods of feeling imbalanced between BPPV episodes.4 Patients will sometimes report avoiding or modifying movements that commonly provoke symptoms in order to prevent an episode of vertigo.

Although the patient’s history can persuade the examiner to diagnose BPPV in a majority of cases, the AAOHNS guidelines state that history alone is insufficient to render an accurate diagnosis of BPPV.4

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The extent and focus of the physical examination is based on the patient’s history and symptoms. The goal of the exam is to reproduce the symptoms and to determine whether the patient has a benign cause of vertigo. Vital signs should always be obtained. A full head and neck exam should be performed to evaluate the ears, nose, and throat, since BPPV can occur secondary to other inner ear disorders.6 A complete neurologic exam should be done to assess for abnormalities in gait, coordination, and sensation. A thorough cardiovascular exam should be done to assess for carotid bruits and abnormal heart rate or rhythm. A carotid doppler, electrocardiogram, or Holter monitoring should be ordered only if abnormalities are found on the exam and/or there is a strong clinical suspicion of a cardiac cause based on the patient’s symptom history.20

The Dix-Hallpike maneuver should be performed in patients with vertigo to assess for posterior semicircular canal BPPV (see “Performing the Dix-Hallpike maneuver”).5 Although positive results from the Dix-Hallpike are the gold standard for diagnosing BPPV, negative results do not rule out BPPV since the patient may be asymptomatic on the day of the test.4,18 In patients with significant vascular disease, cervical stenosis and radiculopathies, severe kyphoscoliosis, Down syndrome, spinal cord injuries, low back dysfunction, ankylosing spondylitis, or morbid obesity, the Dix-Hallpike maneuver should be performed with caution.4 Obese patients may require an additional examiner for support.

If a positive response is observed on the initial side, no further testing is required; the examiner should immediately begin treatment with the canalith repositioning maneuver (described in the Treatment section). When the test response is negative, however, the maneuver should be repeated on the opposite side to confirm which ear is involved. Rarely is a response elicited in both the right and left ear-down positions with corresponding nystagmus; such a response is typically associated with head trauma.4

To rule out orthostatic hypotension, a possible source of “faintness” or “dizziness,” measure for changes in blood pressure (eg, decrease of 20 mm Hg systolic, decrease of 10 mm Hg diastolic) and pulse (eg, increase of 30 beats/min) from the supine to standing positions.20 These measurements should be performed after the Dix-Hallpike maneuver because the changes in patient position required to test BP may affect the results of the Dix-Hallpike maneuver. With the exception of positive results on the Dix-Hallpike test, the patient with BPPV will generally have unremarkable findings on the physical exam.3

On the next page: Lab work-up and imaging >>

LABORATORY WORK-UP AND IMAGING

There is no lab work that assists in making the diagnosis of BPPV. Radiographic imaging21 and laboratory testing are not beneficial and are in fact unnecessary and inappropriate in the patient with probable BPPV.6,8,20 There are no radiologic findings in the patient with BPPV alone.4,22 Clinical practice guidelines recommend against radiologic imaging in patients with BPPV, unless the diagnosis is uncertain or there are additional or unrelated exam findings or symptoms that justify testing.4

DIAGNOSIS

The Dix-Hallpike maneuver is considered the gold standard for diagnosing BPPV,4 although it is possible for the Dix-Hallpike test results to be negative in a patient with BPPV. If the test is negative and there is a strong clinical suspicion for BPPV, the patient may need to come back for a second visit to repeat the maneuver.4 The clinician may also consider referral to a specialist who performs vestibular function testing in order to decrease the time from the onset of symptoms to diagnosis and proper treatment.

According to the AAOHNS guidelines for BPPV, the specific diagnostic criteria for posterior canal BPPV include the patient history of repeated episodes of vertigo related to changes in head position; vertigo and nystagmus elicited on physical exam by the Dix-Hallpike test with a latency period between the onset and completion of the test; and an increase in intensity and then resolution within a minute of onset of the provoked vertigo and nystagmus.4

Patients should be questioned about associated hearing loss. Vertigo accompanied by hearing loss is typically not BPPV, but can be caused by Ménière’s disease or labyrinthitis. Patients presenting with Ménière’s disease commonly have sustained vertigo (lasting for hours), tinnitus, and fluctuating hearing loss.4 Vestibular labyrinthitis typically presents with severe vertigo that lasts from days to weeks (constant and not related to movement), severe nausea and vomiting, hearing loss, and tinnitus.4

Orthostatic hypotension, another cause of dizziness, should always be in the differential. Visual changes, ataxia, confusion, slurred speech, and numbness point to central causes of dizziness such as vertebrobasilar ischemic stroke or vertebrobasilar insufficiency.20

Once the BPPV diagnosis is made, it should be documented in the patient’s medical record. Using a diagnosis code for vertigo or dizziness is insufficient because it only describes the patient’s symptoms and is inadequate for follow-up and continuity of care. Nor does such a code provide the patient with the concise diagnosis needed to engage in self-care. Further, the incidence of the disease remains undocumented for purposes of research on BPPV.

On the next page: Treatment and management >>

TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT

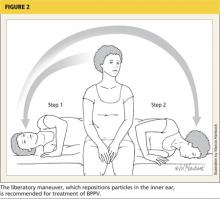

Particle repositioning maneuvers are the recommended treatment for BPPV. These maneuvers have a success rate of greater than 90%5,6 and usually provide immediate resolution of symptoms.23 The canalith repositioning maneuver (CRP; also called the Epley maneuver) and the liberatory maneuver (LM; also called the Semont maneuver) are effective treatments for posterior canal BPPV (see “The Epley Maneuver”).4 The CRP can be performed immediately following positive results on the Dix-Hallpike test.

The CRP depends on gravity to treat BPPV.24 The otoconia settle in the lowest part of the semicircular canals as the patient is moved through a series of positions. The maneuver requires the patient to be rotated 180° (through four positions) beginning with the affected side and then to the uninvolved side before returning to a sitting position.24 Each position is maintained for at least 30 s. Once the otoconia migrate out of the affected semicircular canal and back into the vestibule, the particles should dissolve.

The LM begins with the patient in a seated position with the head turned away from the affected side (see Figure 2). The clinician quickly moves the patient into a side-lying position toward the affected side, with the head turned upward and supported there for approximately 30 s (Step 1).The clinician then quickly moves the patient through the initial seated position (without pausing) to the opposite side-lying position without changing the head position (Step 2). With the head now facing downward, the patient remains motionless for another 30 s before the clinician brings the patient upright to the original seated position. Although patients are sometimes advised to remain upright for 24 to 48 h following in-office treatment (which is not believed to cause harm), there is insufficient evidence to support this recommendation.4

For ongoing care, current clinical guidelines recommend that practitioners offer either vestibular rehabilitation (performed by a clinician or self-administered by the patient) or provide for watchful waiting and follow-up based on the natural course of spontaneous resolution of symptoms.4

On the next page: Patient education and referral >>

PATIENT EDUCATION

It is important to remember that vertigo is a symptom, while BPPV is a diagnosis. Therefore, merely informing the patient that he or she has vertigo is not sufficient. The patient (and his/her family, if present) should be educated about the cause of the patient’s vertigo. The patient should be provided with information about BPPV that is delivered both verbally and through printed health education materials.

The chances and unpredictability of recurrence should be discussed. Ideally, the patient should be instructed to make a same-day follow-up appointment for treatment should symptoms recur. Patients, particularly the elderly, should be counseled about the risk for falls; fall risk assessment questionnaires with recommendations for prevention of injury are helpful.4

The patient with BPPV should be provided with instructions, including diagrams, of how to perform modified CRP exercises at home. Helpful videos are available on the Internet for patient use. For example, the University of Michigan has created videos for a patient diagnosed with BPPV of the right ear (www.youtube.com/watch?v=BY4UeRmTYmA) and the left ear (www.youtube.com/watch?v=lh72suV2p20).

In self-administered CRP, the patient moves through the same positions used for in-office CRP, except that the patient’s head is extended over the edge of a pillow.24 Patients should be instructed to stop the home exercises once they are symptom free for 24 h or more.

FOLLOW-UP AND REFERRAL

The need for follow-up varies depending on the patient’s response to treatment and the incidence of recurrence. Clinical practice guidelines recommend follow-up within a month of initial observation or treatment to reassess and confirm resolution of symptoms.4 Referral to specialists for treatment should be considered without delay if the primary care clinician does not feel confident treating BPPV and/or is unsure of the diagnosis based on the results of the Dix-Hallpike test, particularly if the patient’s quality of life is affected and safety is a concern.

On the next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

BPPV is a common disorder that presents most often in the primary care setting. However, most dizzy patients never see a specialist or clinician who is skilled in providing vestibular evaluation and treatment. To avoid missing the diagnosis or ordering unnecessary diagnostic and laboratory tests, clinicians can readily perform the Dix-Hallpike test and CRP in the office on patients with suspected BPPV.

CRP and vestibular rehabilitation have been proven effective in treating chronic disequilibrium and vertigo. Studies have reported that the mean wait time from initial presentation of symptoms to successful treatment was 92 weeks; 85% of these patients had immediate symptom resolution after the first treatment session with a specialist trained in CRP.25 Improvement in recognition of BPPV at the primary care level will markedly reduce the lag time to treatment.

The author would like to thank Alan L. Desmond, AuD, and Dr. Brian Collie, ENT, for their mentorship and expertise in vestibular disorders.

1. Kroenke K, Hoffman RM, Einstadter D. How common are various causes of dizziness? A critical review. Southern Med J. 2000;93:160-167.

2. Thompson TL, Amedee R. Vertigo: a review of common peripheral and central vestibular disorders.Ochsner J. 2009;9:20-26.

3. Li JC, Egan RE. Neurologic manifestations of benign positional vertigo (2012). Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1158940-overview. Accessed November 14, 2013.

4. Bhattacharyya N, Baugh RF, Orvidas L, et al. Clinical practice guideline: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryng Head Neck Surg. 2008; 139:S47-S81.

5. Steenerson RL, Cronin GW, Marbach PM. Effectiveness of treatment techniques in 923 cases of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:226-231.

6. Parnes LS, Agrawal SK, Atlas J. Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). CMAJ. 2003;169:681-693.

7. Desmond AL. Vestibular Function: Clinical and Practice Management. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2011:1-276.

8. Newman-Toker DE, Camargo CA, Hsieh Y, et al. Disconnect between charted vestibular diagnoses and emergency department management decisions: a cross-sectional analysis from a nationally representative sample. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:970-977.

9. Ahsan SF, Syamal MN, Yaremchuk K, et al. The costs and utility of imaging in evaluating dizzy patients in the emergency room. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:2250-2253.

10. Chan Y. Differential diagnosis of dizziness. Curr Opin Otolaryng Head Neck Surg. 2009;17:200-203.

11. von Brevern M, Radtke A, Lezius F, et al. Epidemiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a population based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:710-715.

12. Oghalai JS, Manolidis S, Barth JL, et al. Unrecognized benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in elderly patients. Otolaryng Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:630-634.

13. Neuhauser HK, Radtke A, von Brevern, et al. Burden of dizziness and vertigo in the community. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2118-2124.

14. Holmes S, Padgham ND. A review of the burden of vertigo. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(19-20):2690-2701.

15. Pollak L, Segal P, Stryjer R, Stern HG. Beliefs and emotional reactions in patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a longitudinal study. Am J Otolaryng. 2012;33:221-225.

16. US Department of Health and Human Services. Confronting the new health care crisis: improving health care quality and lowering costs by fixing our medical liability system (2002). http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/litrefm.pdf. Accessed November 14, 2013.

17. Naylor MD, Kurtzman ET. The role of nurse practitioners in reinventing primary care. Health Affairs. 2010;29:893-899.

18. Desmond AL. Dizziness Reference Guide. Chatham, IL: Micromedical Technologies; 2009.

19. Goebel JA. The ten-minute examination of the dizzy patient. Semin Neurol. 2001;21:391-398.

20. Post RE, Dickerson LM. Dizziness: a diagnostic approach.Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:361-368.

21. Korres S, Riga M, Papacharalampous G, et al. Relative diagnostic importance of electronystagmography and magnetic resonance imaging in vestibular disorders. J Laryngol Otol. 2009;123:851-856.

22. American College of Radiology Expert Panel on Neurologic Imaging. American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria [report], 2008. www.acr.org/~/media/ACR/Documents/AppCriteria/Diagnostic/Vertigo HearingLoss.pdf. Accessed November 14, 2013.

23. Lee S-H, Kim JS. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Clin Neurol. 2010;6:51-63.

24. Helminski JO, Zee DS, Janssen I, Hain TC. Effectiveness of particle repositioning maneuvers in the treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2010;90:663-678.

25. Fife D, Fitzgerald JE. Do patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo receive prompt treatment? Analysis of waiting times and human and financial costs associated with current practice. Int Journal Audiol. 2005;44:50-57.

CE/CME No: CR-1312

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Explain the incidence, predisposing factors, and pathophysiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV).

• Describe the typical presentation and history of symptoms in the patient with BPPV. Describe exam findings that may point to other causes of vertigo/dizziness.

• Describe how to perform the Dix-Hallpike test, the Epley maneuver, and the liberatory maneuver.

• Discuss diagnosis and management of BPPV based on current clinical practice guidelines. Describe positive Dix-Hallpike test results.

• Discuss evidence-based changes in the approach to patients with vertigo that are needed in primary care and the emergency department.

FACULTY

Mary Jo Howell Collie is a family nurse practitioner at Bland County Medical Clinic in Bastian, Virginia, and serves as a preceptor for nurse practitioner students.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Article begins on next page >>

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo accounts for approximately 42% of cases of vertigo seen in primary care settings and is the single most common cause of vertigo in the United States. Our expert outlines an evidence-based approach to diagnosis, which results in an increase in desirable patient outcomes and a decrease in unnecessary tests and medications.

Dizziness is a common complaint of patients seen in both the primary care setting and the emergency department (ED). Dizziness can be classified as vertigo, disequilibrium, presyncope, and lightheadedness. Psychiatric disorders can be the cause in as many as 16% of patients who present with dizziness.1

Vestibular vertigo is the most common type of dizziness and can result from peripheral vestibular causes and central vestibular causes.1 Peripheral vestibular causes include benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), Ménière’s disease, vestibular neuronitis, labyrinthitis, vestibular schwannoma, perilymphatic fistula, superior semicircular canal dehiscence syndrome, and trauma.2 Central vestibular causes of vertigo include vestibular migraine, vertebrobasilar ischemic stroke, and vertebrobasilar insufficiency (transient ischemic attack).2 (For more information, see Pearson T. Ménière’s disease: a lifelong merry-go-round. Clinician Reviews. 2013;23[10]:38-43.)

BPPV accounts for approximately 42% of cases of vertigo in nonspecialty settings such as primary care and is the single most common cause of vertigo in the United States.3,4 Other common causes include vestibular neuritis (41% of cases), Ménière’s disease (10%), and vascular disease (3%).4

BPPV is a disorder of the inner ear that is characterized by repeated episodes of positional vertigo, a spinning sensation produced by changes in head position relative to gravity. The term benign implies a form of positional vertigo not due to any serious central nervous system (CNS) disorder and carries an overall favorable prognosis. The term paroxysmal describes the sudden and rapid onset of vertigo.4

BPPV typically involves either the posterior semicircular canal (by far the most common) or the lateral (horizontal) semicircular canal.5 BPPV involving the posterior semicircular canal comprises 85% to 95% of all cases of BPPV and is the focus of this article.6

BPPV can be diagnosed and treated by multiple clinical disciplines, and there is considerable variation in the management of BPPV across disciplines.4 Delays in diagnosis and treatment can directly affect patients’ quality of life as well as increase health care costs. Patients with BPPV often receive inappropriately prescribed medications, such as vestibular suppressants, and potentially unnecessary diagnostic tests.4,7-9 In many cases, diagnostic and treatment decisions in regard to BPPV are not guided by current evidence.4

On the next page: Epidemiology >>

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The incidence of dizziness in the general population ranges from 20% to 30%, and with every five-year increase in age, there is a 10% increase in incidence of dizziness.10 Approximately 7.5 million patients are seen in ambulatory care annually with the chief complaint of dizziness.10 Further, with the increasing age of the US population, the incidence and prevalence of dizziness, and hence, of BPPV, will likely increase over the next 20 years.

BPPV is the most common vestibular disorder across the lifespan and most commonly presents between the fifth and seventh decade of life.4 The average age of onset of BPPV is 51 years,3 and it is rarely seen in those 35 and younger without a history of head trauma. The prevalence has been reported to range from 10.7 to 64 per 100,000 population, with a lifetime prevalence of 2.4%.4,11 It is estimated that 9% of elderly patients have unrecognized BPPV and experience greater risk for falls, depression, and interference with activities of daily living as a result.12 This, in turn, can lead to increased caregiver burden, decreased family productivity with resultant costs to society, and increased risk for nursing home placement. When not properly diagnosed and treated, BPPV can lead to significant morbidity, psychosocial problems, and increased medical costs.13

One of the main causes of BPPV is head trauma. Other predisposing factors include inactivity, major surgery, acute alcoholism, and CNS disease. BPPV is idiopathic in approximately 50% to 70% of cases.6 Spontaneous remission of BPPV can occur within days to months, or it can resolve after treatment and then recur.7 The recurrence rate of BPPV has been shown to be between 50% to 56% in some studies.11

Neuhauser et al13 evaluated the burden of dizziness within the general population in Germany, screening a cross-sectional sample of 4,869 participants for moderate or severe dizziness. The researchers estimated that 1.8% of adults seek medical care annually for new symptoms of moderate or severe dizziness or vertigo, and that vestibular vertigo accounts for approximately one third of cases of dizziness and vertigo seen in the medical setting. They commented that the latter finding is in line with other studies that have estimated that more than half of cases of dizziness in the medical setting (primary care, specialty care, and ED) are diagnosed as vestibular vertigo. The researchers also found that medical consultations and hospital visits were more frequent for vestibular vertigo than for nonvestibular dizziness. They concluded that more consideration should be given in primary care to common vestibular disorders, particularly BPPV, for which inexpensive and effective treatment with positioning maneuvers can be performed in the primary care setting.13

SUBOPTIMAL MANAGEMENT OF VERTIGO AND BPPV

Although vertigo can be debilitating and significantly reduce patients’ quality of life,13 40% to 80% of cases remain unexplained and therefore go untreated.14 BPPV not only affects patients physically but can also have serious effects on their emotional well-being.15 Anxiety has been found to be associated with BPPV in some cases. It is estimated that 86% of patients with BPPV symptoms experience problems with activities of daily living and experience work absences.11

According to clinical practice guidelines developed by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAOHNS),health care costs associated with the diagnosis of BPPV alone approach $2 billion per year, and it costs approximately $2,000 per patient to arrive at a diagnosis of BPPV.4 A recent retrospective study examined 1,681 patients who presented to the ED with complaints of vertigo and dizziness over a three-year period.9 Nearly half the patients received a CT scan of the brain and head, resulting in a total cost of $988,200. However, fewer than 1% of the CTs revealed an underlying condition that required intervention. The researchers concluded that, for patients presenting with isolated dizziness, lightheadedness, or vertigo without other symptoms, the likelihood of finding an acute life-threatening abnormality on CT is low, and therefore CT is not helpful.

Newman-Toker et al8 studied 9,472 dizzy patients who visited the ED over a 13-year period; of the 7.4% who were diagnosed with a vestibular disorder, 84% had BPPV or acute peripheral vestibulopathy.8 Patients diagnosed with BPPV were more likely to undergo diagnostic imaging with CT and more likely to receive a prescription for the vestibular suppressant meclizine than nondizzy patients. The researchers concluded that these patients were not managed optimally, citing overuse of diagnostic imaging and prescription meclizine, which is not indicated for treating BPPV.8

The use of unnecessary diagnostic testing for the work-up of vertigo has been well documented in the literature. However, the trend of diagnostic imaging for vertigo and dizziness has continued, imposing an economic burden on the health care system. The reason for this may be twofold. First, primary care and ED providers may not feel confident in their ability to recognize and diagnose BPPV. Second, an underlying component may be the clinician’s perceived need to practice defensive medicine.

A report published by the Department of Health and Human Services included a physician survey regarding litigation.16 Of those surveyed, 79% responded that they had ordered more tests than they felt were needed, due to the fear of being sued. By extrapolation, it is reasonable to assume that similar practices and concerns may apply to nurse practitioners, of whom 70% to 80% work in primary care,17 as well as physician assistants in primary care.

Although medications are used frequently for treating dizziness, this practice is not supported by evidence-based criteria.7 Overuse of vestibular suppressants for treatment of BPPV has been identified in the literature in both primary care settings and the ED; in particular, use of meclizine for treatment of dizziness and vertigo needs to be reconsidered.4,8

On the next page: Pathophysiology and patient presentation >>

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

BPPV most commonly is believed to result from calcium carbonate and protein crystals called otoconia becoming dislodged from the inner ear (utricle) and settling in one of the semicircular canals (most commonly the posterior); this theory is known as canalithiasis.18 When the patient moves certain ways, the otoconia shift and cause an abnormal stimulation of the motion sensor in the affected ear. This stimulation causes conflicting signals from the two labyrinths of the inner ear, resulting in brief, intense sensations of vertigo.18 A video describing the pathophysiology is available at www.youtube.com/watch?v=gDOrltSBvKI.

PATIENT PRESENTATION AND HISTORY

The patient’s description of symptoms is critical in the work-up for dizziness. It is important to ask patients to describe their symptoms using words other than “dizzy,” as the meaning of the word may vary from person to person.10

Dizziness includes a variety of symptoms such as vertigo, unsteadiness, weakness, presyncope, syncope, lightheadedness, or falling. Vertigo is the illusion of a rotational movement of one’s self or surroundings, a spinning sensation.19 True vertigo is most likely due to peripheral vestibular disorders. Complaints of disequilibrium and ataxia point to central pathology.2 Nonvertigo symptoms—generalized weakness, lightheadedness, imbalance, unsteadiness, and tilting sensations—can point to CNS, cardiovascular, and systemic diseases and require further investigation.4,10,18

A complete health history, including medications and assessing for head trauma, ear disease, or surgery, can be helpful in rendering a diagnosis. Patients should also be questioned about caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol use. A patient-centered questionnaire can be developed to guide the clinician in obtaining a thorough history of the patient’s perceptions of his/her symptoms. An important question to ask is, “Do you get dizzy when rolling over in bed?” A “yes” answer to this question raises the clinical suspicion for BPPV.

A typical description of BPPV symptoms includes a brief episode (less than a minute) of intense vertigo that can be brought about by positional changes associated with everyday activities such as rolling over in bed, tilting the head to look upward (eg, to place an object on a shelf higher than the head), or bending forward at the waist (eg, to tie shoes).4,18 This vertigo may occur frequently for weeks, disappear for months, and then begin again. Some patients may report that they were dizzy for hours or all day. On further questioning, however, the clinician may determine that the dizziness actually occurred in short, intense episodes,which, due to their severity, may be perceived as lasting longer than a minute.18 Commonly, patients may report periods of feeling imbalanced between BPPV episodes.4 Patients will sometimes report avoiding or modifying movements that commonly provoke symptoms in order to prevent an episode of vertigo.

Although the patient’s history can persuade the examiner to diagnose BPPV in a majority of cases, the AAOHNS guidelines state that history alone is insufficient to render an accurate diagnosis of BPPV.4

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The extent and focus of the physical examination is based on the patient’s history and symptoms. The goal of the exam is to reproduce the symptoms and to determine whether the patient has a benign cause of vertigo. Vital signs should always be obtained. A full head and neck exam should be performed to evaluate the ears, nose, and throat, since BPPV can occur secondary to other inner ear disorders.6 A complete neurologic exam should be done to assess for abnormalities in gait, coordination, and sensation. A thorough cardiovascular exam should be done to assess for carotid bruits and abnormal heart rate or rhythm. A carotid doppler, electrocardiogram, or Holter monitoring should be ordered only if abnormalities are found on the exam and/or there is a strong clinical suspicion of a cardiac cause based on the patient’s symptom history.20

The Dix-Hallpike maneuver should be performed in patients with vertigo to assess for posterior semicircular canal BPPV (see “Performing the Dix-Hallpike maneuver”).5 Although positive results from the Dix-Hallpike are the gold standard for diagnosing BPPV, negative results do not rule out BPPV since the patient may be asymptomatic on the day of the test.4,18 In patients with significant vascular disease, cervical stenosis and radiculopathies, severe kyphoscoliosis, Down syndrome, spinal cord injuries, low back dysfunction, ankylosing spondylitis, or morbid obesity, the Dix-Hallpike maneuver should be performed with caution.4 Obese patients may require an additional examiner for support.

If a positive response is observed on the initial side, no further testing is required; the examiner should immediately begin treatment with the canalith repositioning maneuver (described in the Treatment section). When the test response is negative, however, the maneuver should be repeated on the opposite side to confirm which ear is involved. Rarely is a response elicited in both the right and left ear-down positions with corresponding nystagmus; such a response is typically associated with head trauma.4

To rule out orthostatic hypotension, a possible source of “faintness” or “dizziness,” measure for changes in blood pressure (eg, decrease of 20 mm Hg systolic, decrease of 10 mm Hg diastolic) and pulse (eg, increase of 30 beats/min) from the supine to standing positions.20 These measurements should be performed after the Dix-Hallpike maneuver because the changes in patient position required to test BP may affect the results of the Dix-Hallpike maneuver. With the exception of positive results on the Dix-Hallpike test, the patient with BPPV will generally have unremarkable findings on the physical exam.3

On the next page: Lab work-up and imaging >>

LABORATORY WORK-UP AND IMAGING

There is no lab work that assists in making the diagnosis of BPPV. Radiographic imaging21 and laboratory testing are not beneficial and are in fact unnecessary and inappropriate in the patient with probable BPPV.6,8,20 There are no radiologic findings in the patient with BPPV alone.4,22 Clinical practice guidelines recommend against radiologic imaging in patients with BPPV, unless the diagnosis is uncertain or there are additional or unrelated exam findings or symptoms that justify testing.4

DIAGNOSIS

The Dix-Hallpike maneuver is considered the gold standard for diagnosing BPPV,4 although it is possible for the Dix-Hallpike test results to be negative in a patient with BPPV. If the test is negative and there is a strong clinical suspicion for BPPV, the patient may need to come back for a second visit to repeat the maneuver.4 The clinician may also consider referral to a specialist who performs vestibular function testing in order to decrease the time from the onset of symptoms to diagnosis and proper treatment.

According to the AAOHNS guidelines for BPPV, the specific diagnostic criteria for posterior canal BPPV include the patient history of repeated episodes of vertigo related to changes in head position; vertigo and nystagmus elicited on physical exam by the Dix-Hallpike test with a latency period between the onset and completion of the test; and an increase in intensity and then resolution within a minute of onset of the provoked vertigo and nystagmus.4

Patients should be questioned about associated hearing loss. Vertigo accompanied by hearing loss is typically not BPPV, but can be caused by Ménière’s disease or labyrinthitis. Patients presenting with Ménière’s disease commonly have sustained vertigo (lasting for hours), tinnitus, and fluctuating hearing loss.4 Vestibular labyrinthitis typically presents with severe vertigo that lasts from days to weeks (constant and not related to movement), severe nausea and vomiting, hearing loss, and tinnitus.4

Orthostatic hypotension, another cause of dizziness, should always be in the differential. Visual changes, ataxia, confusion, slurred speech, and numbness point to central causes of dizziness such as vertebrobasilar ischemic stroke or vertebrobasilar insufficiency.20

Once the BPPV diagnosis is made, it should be documented in the patient’s medical record. Using a diagnosis code for vertigo or dizziness is insufficient because it only describes the patient’s symptoms and is inadequate for follow-up and continuity of care. Nor does such a code provide the patient with the concise diagnosis needed to engage in self-care. Further, the incidence of the disease remains undocumented for purposes of research on BPPV.

On the next page: Treatment and management >>

TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT

Particle repositioning maneuvers are the recommended treatment for BPPV. These maneuvers have a success rate of greater than 90%5,6 and usually provide immediate resolution of symptoms.23 The canalith repositioning maneuver (CRP; also called the Epley maneuver) and the liberatory maneuver (LM; also called the Semont maneuver) are effective treatments for posterior canal BPPV (see “The Epley Maneuver”).4 The CRP can be performed immediately following positive results on the Dix-Hallpike test.

The CRP depends on gravity to treat BPPV.24 The otoconia settle in the lowest part of the semicircular canals as the patient is moved through a series of positions. The maneuver requires the patient to be rotated 180° (through four positions) beginning with the affected side and then to the uninvolved side before returning to a sitting position.24 Each position is maintained for at least 30 s. Once the otoconia migrate out of the affected semicircular canal and back into the vestibule, the particles should dissolve.

The LM begins with the patient in a seated position with the head turned away from the affected side (see Figure 2). The clinician quickly moves the patient into a side-lying position toward the affected side, with the head turned upward and supported there for approximately 30 s (Step 1).The clinician then quickly moves the patient through the initial seated position (without pausing) to the opposite side-lying position without changing the head position (Step 2). With the head now facing downward, the patient remains motionless for another 30 s before the clinician brings the patient upright to the original seated position. Although patients are sometimes advised to remain upright for 24 to 48 h following in-office treatment (which is not believed to cause harm), there is insufficient evidence to support this recommendation.4

For ongoing care, current clinical guidelines recommend that practitioners offer either vestibular rehabilitation (performed by a clinician or self-administered by the patient) or provide for watchful waiting and follow-up based on the natural course of spontaneous resolution of symptoms.4

On the next page: Patient education and referral >>

PATIENT EDUCATION

It is important to remember that vertigo is a symptom, while BPPV is a diagnosis. Therefore, merely informing the patient that he or she has vertigo is not sufficient. The patient (and his/her family, if present) should be educated about the cause of the patient’s vertigo. The patient should be provided with information about BPPV that is delivered both verbally and through printed health education materials.

The chances and unpredictability of recurrence should be discussed. Ideally, the patient should be instructed to make a same-day follow-up appointment for treatment should symptoms recur. Patients, particularly the elderly, should be counseled about the risk for falls; fall risk assessment questionnaires with recommendations for prevention of injury are helpful.4

The patient with BPPV should be provided with instructions, including diagrams, of how to perform modified CRP exercises at home. Helpful videos are available on the Internet for patient use. For example, the University of Michigan has created videos for a patient diagnosed with BPPV of the right ear (www.youtube.com/watch?v=BY4UeRmTYmA) and the left ear (www.youtube.com/watch?v=lh72suV2p20).

In self-administered CRP, the patient moves through the same positions used for in-office CRP, except that the patient’s head is extended over the edge of a pillow.24 Patients should be instructed to stop the home exercises once they are symptom free for 24 h or more.

FOLLOW-UP AND REFERRAL

The need for follow-up varies depending on the patient’s response to treatment and the incidence of recurrence. Clinical practice guidelines recommend follow-up within a month of initial observation or treatment to reassess and confirm resolution of symptoms.4 Referral to specialists for treatment should be considered without delay if the primary care clinician does not feel confident treating BPPV and/or is unsure of the diagnosis based on the results of the Dix-Hallpike test, particularly if the patient’s quality of life is affected and safety is a concern.

On the next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

BPPV is a common disorder that presents most often in the primary care setting. However, most dizzy patients never see a specialist or clinician who is skilled in providing vestibular evaluation and treatment. To avoid missing the diagnosis or ordering unnecessary diagnostic and laboratory tests, clinicians can readily perform the Dix-Hallpike test and CRP in the office on patients with suspected BPPV.

CRP and vestibular rehabilitation have been proven effective in treating chronic disequilibrium and vertigo. Studies have reported that the mean wait time from initial presentation of symptoms to successful treatment was 92 weeks; 85% of these patients had immediate symptom resolution after the first treatment session with a specialist trained in CRP.25 Improvement in recognition of BPPV at the primary care level will markedly reduce the lag time to treatment.

The author would like to thank Alan L. Desmond, AuD, and Dr. Brian Collie, ENT, for their mentorship and expertise in vestibular disorders.

CE/CME No: CR-1312

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Explain the incidence, predisposing factors, and pathophysiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV).

• Describe the typical presentation and history of symptoms in the patient with BPPV. Describe exam findings that may point to other causes of vertigo/dizziness.

• Describe how to perform the Dix-Hallpike test, the Epley maneuver, and the liberatory maneuver.

• Discuss diagnosis and management of BPPV based on current clinical practice guidelines. Describe positive Dix-Hallpike test results.

• Discuss evidence-based changes in the approach to patients with vertigo that are needed in primary care and the emergency department.

FACULTY

Mary Jo Howell Collie is a family nurse practitioner at Bland County Medical Clinic in Bastian, Virginia, and serves as a preceptor for nurse practitioner students.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Article begins on next page >>

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo accounts for approximately 42% of cases of vertigo seen in primary care settings and is the single most common cause of vertigo in the United States. Our expert outlines an evidence-based approach to diagnosis, which results in an increase in desirable patient outcomes and a decrease in unnecessary tests and medications.

Dizziness is a common complaint of patients seen in both the primary care setting and the emergency department (ED). Dizziness can be classified as vertigo, disequilibrium, presyncope, and lightheadedness. Psychiatric disorders can be the cause in as many as 16% of patients who present with dizziness.1

Vestibular vertigo is the most common type of dizziness and can result from peripheral vestibular causes and central vestibular causes.1 Peripheral vestibular causes include benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), Ménière’s disease, vestibular neuronitis, labyrinthitis, vestibular schwannoma, perilymphatic fistula, superior semicircular canal dehiscence syndrome, and trauma.2 Central vestibular causes of vertigo include vestibular migraine, vertebrobasilar ischemic stroke, and vertebrobasilar insufficiency (transient ischemic attack).2 (For more information, see Pearson T. Ménière’s disease: a lifelong merry-go-round. Clinician Reviews. 2013;23[10]:38-43.)

BPPV accounts for approximately 42% of cases of vertigo in nonspecialty settings such as primary care and is the single most common cause of vertigo in the United States.3,4 Other common causes include vestibular neuritis (41% of cases), Ménière’s disease (10%), and vascular disease (3%).4

BPPV is a disorder of the inner ear that is characterized by repeated episodes of positional vertigo, a spinning sensation produced by changes in head position relative to gravity. The term benign implies a form of positional vertigo not due to any serious central nervous system (CNS) disorder and carries an overall favorable prognosis. The term paroxysmal describes the sudden and rapid onset of vertigo.4

BPPV typically involves either the posterior semicircular canal (by far the most common) or the lateral (horizontal) semicircular canal.5 BPPV involving the posterior semicircular canal comprises 85% to 95% of all cases of BPPV and is the focus of this article.6

BPPV can be diagnosed and treated by multiple clinical disciplines, and there is considerable variation in the management of BPPV across disciplines.4 Delays in diagnosis and treatment can directly affect patients’ quality of life as well as increase health care costs. Patients with BPPV often receive inappropriately prescribed medications, such as vestibular suppressants, and potentially unnecessary diagnostic tests.4,7-9 In many cases, diagnostic and treatment decisions in regard to BPPV are not guided by current evidence.4

On the next page: Epidemiology >>

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The incidence of dizziness in the general population ranges from 20% to 30%, and with every five-year increase in age, there is a 10% increase in incidence of dizziness.10 Approximately 7.5 million patients are seen in ambulatory care annually with the chief complaint of dizziness.10 Further, with the increasing age of the US population, the incidence and prevalence of dizziness, and hence, of BPPV, will likely increase over the next 20 years.

BPPV is the most common vestibular disorder across the lifespan and most commonly presents between the fifth and seventh decade of life.4 The average age of onset of BPPV is 51 years,3 and it is rarely seen in those 35 and younger without a history of head trauma. The prevalence has been reported to range from 10.7 to 64 per 100,000 population, with a lifetime prevalence of 2.4%.4,11 It is estimated that 9% of elderly patients have unrecognized BPPV and experience greater risk for falls, depression, and interference with activities of daily living as a result.12 This, in turn, can lead to increased caregiver burden, decreased family productivity with resultant costs to society, and increased risk for nursing home placement. When not properly diagnosed and treated, BPPV can lead to significant morbidity, psychosocial problems, and increased medical costs.13

One of the main causes of BPPV is head trauma. Other predisposing factors include inactivity, major surgery, acute alcoholism, and CNS disease. BPPV is idiopathic in approximately 50% to 70% of cases.6 Spontaneous remission of BPPV can occur within days to months, or it can resolve after treatment and then recur.7 The recurrence rate of BPPV has been shown to be between 50% to 56% in some studies.11

Neuhauser et al13 evaluated the burden of dizziness within the general population in Germany, screening a cross-sectional sample of 4,869 participants for moderate or severe dizziness. The researchers estimated that 1.8% of adults seek medical care annually for new symptoms of moderate or severe dizziness or vertigo, and that vestibular vertigo accounts for approximately one third of cases of dizziness and vertigo seen in the medical setting. They commented that the latter finding is in line with other studies that have estimated that more than half of cases of dizziness in the medical setting (primary care, specialty care, and ED) are diagnosed as vestibular vertigo. The researchers also found that medical consultations and hospital visits were more frequent for vestibular vertigo than for nonvestibular dizziness. They concluded that more consideration should be given in primary care to common vestibular disorders, particularly BPPV, for which inexpensive and effective treatment with positioning maneuvers can be performed in the primary care setting.13

SUBOPTIMAL MANAGEMENT OF VERTIGO AND BPPV

Although vertigo can be debilitating and significantly reduce patients’ quality of life,13 40% to 80% of cases remain unexplained and therefore go untreated.14 BPPV not only affects patients physically but can also have serious effects on their emotional well-being.15 Anxiety has been found to be associated with BPPV in some cases. It is estimated that 86% of patients with BPPV symptoms experience problems with activities of daily living and experience work absences.11

According to clinical practice guidelines developed by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAOHNS),health care costs associated with the diagnosis of BPPV alone approach $2 billion per year, and it costs approximately $2,000 per patient to arrive at a diagnosis of BPPV.4 A recent retrospective study examined 1,681 patients who presented to the ED with complaints of vertigo and dizziness over a three-year period.9 Nearly half the patients received a CT scan of the brain and head, resulting in a total cost of $988,200. However, fewer than 1% of the CTs revealed an underlying condition that required intervention. The researchers concluded that, for patients presenting with isolated dizziness, lightheadedness, or vertigo without other symptoms, the likelihood of finding an acute life-threatening abnormality on CT is low, and therefore CT is not helpful.

Newman-Toker et al8 studied 9,472 dizzy patients who visited the ED over a 13-year period; of the 7.4% who were diagnosed with a vestibular disorder, 84% had BPPV or acute peripheral vestibulopathy.8 Patients diagnosed with BPPV were more likely to undergo diagnostic imaging with CT and more likely to receive a prescription for the vestibular suppressant meclizine than nondizzy patients. The researchers concluded that these patients were not managed optimally, citing overuse of diagnostic imaging and prescription meclizine, which is not indicated for treating BPPV.8

The use of unnecessary diagnostic testing for the work-up of vertigo has been well documented in the literature. However, the trend of diagnostic imaging for vertigo and dizziness has continued, imposing an economic burden on the health care system. The reason for this may be twofold. First, primary care and ED providers may not feel confident in their ability to recognize and diagnose BPPV. Second, an underlying component may be the clinician’s perceived need to practice defensive medicine.

A report published by the Department of Health and Human Services included a physician survey regarding litigation.16 Of those surveyed, 79% responded that they had ordered more tests than they felt were needed, due to the fear of being sued. By extrapolation, it is reasonable to assume that similar practices and concerns may apply to nurse practitioners, of whom 70% to 80% work in primary care,17 as well as physician assistants in primary care.

Although medications are used frequently for treating dizziness, this practice is not supported by evidence-based criteria.7 Overuse of vestibular suppressants for treatment of BPPV has been identified in the literature in both primary care settings and the ED; in particular, use of meclizine for treatment of dizziness and vertigo needs to be reconsidered.4,8

On the next page: Pathophysiology and patient presentation >>

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

BPPV most commonly is believed to result from calcium carbonate and protein crystals called otoconia becoming dislodged from the inner ear (utricle) and settling in one of the semicircular canals (most commonly the posterior); this theory is known as canalithiasis.18 When the patient moves certain ways, the otoconia shift and cause an abnormal stimulation of the motion sensor in the affected ear. This stimulation causes conflicting signals from the two labyrinths of the inner ear, resulting in brief, intense sensations of vertigo.18 A video describing the pathophysiology is available at www.youtube.com/watch?v=gDOrltSBvKI.

PATIENT PRESENTATION AND HISTORY

The patient’s description of symptoms is critical in the work-up for dizziness. It is important to ask patients to describe their symptoms using words other than “dizzy,” as the meaning of the word may vary from person to person.10

Dizziness includes a variety of symptoms such as vertigo, unsteadiness, weakness, presyncope, syncope, lightheadedness, or falling. Vertigo is the illusion of a rotational movement of one’s self or surroundings, a spinning sensation.19 True vertigo is most likely due to peripheral vestibular disorders. Complaints of disequilibrium and ataxia point to central pathology.2 Nonvertigo symptoms—generalized weakness, lightheadedness, imbalance, unsteadiness, and tilting sensations—can point to CNS, cardiovascular, and systemic diseases and require further investigation.4,10,18

A complete health history, including medications and assessing for head trauma, ear disease, or surgery, can be helpful in rendering a diagnosis. Patients should also be questioned about caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol use. A patient-centered questionnaire can be developed to guide the clinician in obtaining a thorough history of the patient’s perceptions of his/her symptoms. An important question to ask is, “Do you get dizzy when rolling over in bed?” A “yes” answer to this question raises the clinical suspicion for BPPV.

A typical description of BPPV symptoms includes a brief episode (less than a minute) of intense vertigo that can be brought about by positional changes associated with everyday activities such as rolling over in bed, tilting the head to look upward (eg, to place an object on a shelf higher than the head), or bending forward at the waist (eg, to tie shoes).4,18 This vertigo may occur frequently for weeks, disappear for months, and then begin again. Some patients may report that they were dizzy for hours or all day. On further questioning, however, the clinician may determine that the dizziness actually occurred in short, intense episodes,which, due to their severity, may be perceived as lasting longer than a minute.18 Commonly, patients may report periods of feeling imbalanced between BPPV episodes.4 Patients will sometimes report avoiding or modifying movements that commonly provoke symptoms in order to prevent an episode of vertigo.

Although the patient’s history can persuade the examiner to diagnose BPPV in a majority of cases, the AAOHNS guidelines state that history alone is insufficient to render an accurate diagnosis of BPPV.4

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The extent and focus of the physical examination is based on the patient’s history and symptoms. The goal of the exam is to reproduce the symptoms and to determine whether the patient has a benign cause of vertigo. Vital signs should always be obtained. A full head and neck exam should be performed to evaluate the ears, nose, and throat, since BPPV can occur secondary to other inner ear disorders.6 A complete neurologic exam should be done to assess for abnormalities in gait, coordination, and sensation. A thorough cardiovascular exam should be done to assess for carotid bruits and abnormal heart rate or rhythm. A carotid doppler, electrocardiogram, or Holter monitoring should be ordered only if abnormalities are found on the exam and/or there is a strong clinical suspicion of a cardiac cause based on the patient’s symptom history.20

The Dix-Hallpike maneuver should be performed in patients with vertigo to assess for posterior semicircular canal BPPV (see “Performing the Dix-Hallpike maneuver”).5 Although positive results from the Dix-Hallpike are the gold standard for diagnosing BPPV, negative results do not rule out BPPV since the patient may be asymptomatic on the day of the test.4,18 In patients with significant vascular disease, cervical stenosis and radiculopathies, severe kyphoscoliosis, Down syndrome, spinal cord injuries, low back dysfunction, ankylosing spondylitis, or morbid obesity, the Dix-Hallpike maneuver should be performed with caution.4 Obese patients may require an additional examiner for support.

If a positive response is observed on the initial side, no further testing is required; the examiner should immediately begin treatment with the canalith repositioning maneuver (described in the Treatment section). When the test response is negative, however, the maneuver should be repeated on the opposite side to confirm which ear is involved. Rarely is a response elicited in both the right and left ear-down positions with corresponding nystagmus; such a response is typically associated with head trauma.4

To rule out orthostatic hypotension, a possible source of “faintness” or “dizziness,” measure for changes in blood pressure (eg, decrease of 20 mm Hg systolic, decrease of 10 mm Hg diastolic) and pulse (eg, increase of 30 beats/min) from the supine to standing positions.20 These measurements should be performed after the Dix-Hallpike maneuver because the changes in patient position required to test BP may affect the results of the Dix-Hallpike maneuver. With the exception of positive results on the Dix-Hallpike test, the patient with BPPV will generally have unremarkable findings on the physical exam.3

On the next page: Lab work-up and imaging >>

LABORATORY WORK-UP AND IMAGING

There is no lab work that assists in making the diagnosis of BPPV. Radiographic imaging21 and laboratory testing are not beneficial and are in fact unnecessary and inappropriate in the patient with probable BPPV.6,8,20 There are no radiologic findings in the patient with BPPV alone.4,22 Clinical practice guidelines recommend against radiologic imaging in patients with BPPV, unless the diagnosis is uncertain or there are additional or unrelated exam findings or symptoms that justify testing.4

DIAGNOSIS

The Dix-Hallpike maneuver is considered the gold standard for diagnosing BPPV,4 although it is possible for the Dix-Hallpike test results to be negative in a patient with BPPV. If the test is negative and there is a strong clinical suspicion for BPPV, the patient may need to come back for a second visit to repeat the maneuver.4 The clinician may also consider referral to a specialist who performs vestibular function testing in order to decrease the time from the onset of symptoms to diagnosis and proper treatment.

According to the AAOHNS guidelines for BPPV, the specific diagnostic criteria for posterior canal BPPV include the patient history of repeated episodes of vertigo related to changes in head position; vertigo and nystagmus elicited on physical exam by the Dix-Hallpike test with a latency period between the onset and completion of the test; and an increase in intensity and then resolution within a minute of onset of the provoked vertigo and nystagmus.4

Patients should be questioned about associated hearing loss. Vertigo accompanied by hearing loss is typically not BPPV, but can be caused by Ménière’s disease or labyrinthitis. Patients presenting with Ménière’s disease commonly have sustained vertigo (lasting for hours), tinnitus, and fluctuating hearing loss.4 Vestibular labyrinthitis typically presents with severe vertigo that lasts from days to weeks (constant and not related to movement), severe nausea and vomiting, hearing loss, and tinnitus.4

Orthostatic hypotension, another cause of dizziness, should always be in the differential. Visual changes, ataxia, confusion, slurred speech, and numbness point to central causes of dizziness such as vertebrobasilar ischemic stroke or vertebrobasilar insufficiency.20

Once the BPPV diagnosis is made, it should be documented in the patient’s medical record. Using a diagnosis code for vertigo or dizziness is insufficient because it only describes the patient’s symptoms and is inadequate for follow-up and continuity of care. Nor does such a code provide the patient with the concise diagnosis needed to engage in self-care. Further, the incidence of the disease remains undocumented for purposes of research on BPPV.

On the next page: Treatment and management >>

TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT

Particle repositioning maneuvers are the recommended treatment for BPPV. These maneuvers have a success rate of greater than 90%5,6 and usually provide immediate resolution of symptoms.23 The canalith repositioning maneuver (CRP; also called the Epley maneuver) and the liberatory maneuver (LM; also called the Semont maneuver) are effective treatments for posterior canal BPPV (see “The Epley Maneuver”).4 The CRP can be performed immediately following positive results on the Dix-Hallpike test.

The CRP depends on gravity to treat BPPV.24 The otoconia settle in the lowest part of the semicircular canals as the patient is moved through a series of positions. The maneuver requires the patient to be rotated 180° (through four positions) beginning with the affected side and then to the uninvolved side before returning to a sitting position.24 Each position is maintained for at least 30 s. Once the otoconia migrate out of the affected semicircular canal and back into the vestibule, the particles should dissolve.

The LM begins with the patient in a seated position with the head turned away from the affected side (see Figure 2). The clinician quickly moves the patient into a side-lying position toward the affected side, with the head turned upward and supported there for approximately 30 s (Step 1).The clinician then quickly moves the patient through the initial seated position (without pausing) to the opposite side-lying position without changing the head position (Step 2). With the head now facing downward, the patient remains motionless for another 30 s before the clinician brings the patient upright to the original seated position. Although patients are sometimes advised to remain upright for 24 to 48 h following in-office treatment (which is not believed to cause harm), there is insufficient evidence to support this recommendation.4

For ongoing care, current clinical guidelines recommend that practitioners offer either vestibular rehabilitation (performed by a clinician or self-administered by the patient) or provide for watchful waiting and follow-up based on the natural course of spontaneous resolution of symptoms.4

On the next page: Patient education and referral >>

PATIENT EDUCATION

It is important to remember that vertigo is a symptom, while BPPV is a diagnosis. Therefore, merely informing the patient that he or she has vertigo is not sufficient. The patient (and his/her family, if present) should be educated about the cause of the patient’s vertigo. The patient should be provided with information about BPPV that is delivered both verbally and through printed health education materials.

The chances and unpredictability of recurrence should be discussed. Ideally, the patient should be instructed to make a same-day follow-up appointment for treatment should symptoms recur. Patients, particularly the elderly, should be counseled about the risk for falls; fall risk assessment questionnaires with recommendations for prevention of injury are helpful.4

The patient with BPPV should be provided with instructions, including diagrams, of how to perform modified CRP exercises at home. Helpful videos are available on the Internet for patient use. For example, the University of Michigan has created videos for a patient diagnosed with BPPV of the right ear (www.youtube.com/watch?v=BY4UeRmTYmA) and the left ear (www.youtube.com/watch?v=lh72suV2p20).

In self-administered CRP, the patient moves through the same positions used for in-office CRP, except that the patient’s head is extended over the edge of a pillow.24 Patients should be instructed to stop the home exercises once they are symptom free for 24 h or more.

FOLLOW-UP AND REFERRAL

The need for follow-up varies depending on the patient’s response to treatment and the incidence of recurrence. Clinical practice guidelines recommend follow-up within a month of initial observation or treatment to reassess and confirm resolution of symptoms.4 Referral to specialists for treatment should be considered without delay if the primary care clinician does not feel confident treating BPPV and/or is unsure of the diagnosis based on the results of the Dix-Hallpike test, particularly if the patient’s quality of life is affected and safety is a concern.

On the next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

BPPV is a common disorder that presents most often in the primary care setting. However, most dizzy patients never see a specialist or clinician who is skilled in providing vestibular evaluation and treatment. To avoid missing the diagnosis or ordering unnecessary diagnostic and laboratory tests, clinicians can readily perform the Dix-Hallpike test and CRP in the office on patients with suspected BPPV.

CRP and vestibular rehabilitation have been proven effective in treating chronic disequilibrium and vertigo. Studies have reported that the mean wait time from initial presentation of symptoms to successful treatment was 92 weeks; 85% of these patients had immediate symptom resolution after the first treatment session with a specialist trained in CRP.25 Improvement in recognition of BPPV at the primary care level will markedly reduce the lag time to treatment.

The author would like to thank Alan L. Desmond, AuD, and Dr. Brian Collie, ENT, for their mentorship and expertise in vestibular disorders.

1. Kroenke K, Hoffman RM, Einstadter D. How common are various causes of dizziness? A critical review. Southern Med J. 2000;93:160-167.

2. Thompson TL, Amedee R. Vertigo: a review of common peripheral and central vestibular disorders.Ochsner J. 2009;9:20-26.

3. Li JC, Egan RE. Neurologic manifestations of benign positional vertigo (2012). Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1158940-overview. Accessed November 14, 2013.

4. Bhattacharyya N, Baugh RF, Orvidas L, et al. Clinical practice guideline: benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryng Head Neck Surg. 2008; 139:S47-S81.

5. Steenerson RL, Cronin GW, Marbach PM. Effectiveness of treatment techniques in 923 cases of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:226-231.

6. Parnes LS, Agrawal SK, Atlas J. Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). CMAJ. 2003;169:681-693.

7. Desmond AL. Vestibular Function: Clinical and Practice Management. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2011:1-276.

8. Newman-Toker DE, Camargo CA, Hsieh Y, et al. Disconnect between charted vestibular diagnoses and emergency department management decisions: a cross-sectional analysis from a nationally representative sample. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:970-977.

9. Ahsan SF, Syamal MN, Yaremchuk K, et al. The costs and utility of imaging in evaluating dizzy patients in the emergency room. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:2250-2253.

10. Chan Y. Differential diagnosis of dizziness. Curr Opin Otolaryng Head Neck Surg. 2009;17:200-203.

11. von Brevern M, Radtke A, Lezius F, et al. Epidemiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a population based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:710-715.

12. Oghalai JS, Manolidis S, Barth JL, et al. Unrecognized benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in elderly patients. Otolaryng Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:630-634.

13. Neuhauser HK, Radtke A, von Brevern, et al. Burden of dizziness and vertigo in the community. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2118-2124.

14. Holmes S, Padgham ND. A review of the burden of vertigo. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(19-20):2690-2701.