User login

Step by step: Obliterating the vaginal canal to correct pelvic organ prolapse

- LeFort partial colpocleisis

- Colpectomy and colpocleisis

- Colpectomy and colpocleisis after two previously failed obliterative procedures

These videos were selected by Mickey Karram, MD, and are presented courtesy of the International Academy of Pelvic Surgery (IAPS)

This article, with accompanying video footage, is presented with the support of the International Academy of Pelvic Surgery.

As women live longer, on average, pelvic floor disorders are, as a whole, becoming more prevalent and a greater health and social problem. Many women entering the eighth and ninth decades of life display symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse (POP)—often after an unsuccessful trial of a pessary or even surgery.

These elderly patients often have other concomitant medical issues and are not sexually active, making extensive surgery for them less than an ideal solution. Instead, surgical procedures that obliterate the vaginal canal can alleviate their symptoms of POP.

In this article, we provide a step-by-step description of:

- LeFort partial colpocleisis in a woman who still has her uterus in place

- partial or complete colpectomy and colpocleisis in a woman who has post-hysterectomy prolapse

- levator plication and perineorrhaphy, as essential concluding steps in these procedures.

LeFort partial colpocleisis

An obliterative procedure in the form of a LeFort partial colpocleisis is an option when a patient 1) has her uterus and 2) is no longer sexually active. Because the uterus is retained in this procedure, however, keep in mind that it will be difficult to evaluate any uterine bleeding or cervical pathology in the future. Endovaginal ultrasonography or an endometrial biopsy, and a Pap smear, must be done before LeFort surgery.

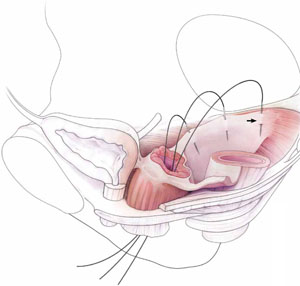

The ideal candidate for LeFort partial colpocleisis is a woman who has complete uterine prolapse, or procidentia (FIGURE 1), which is characterized by symmetric eversion of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls.

FIGURE 1 Pelvic organ prolapse, preoperatively

Top: Uterine procidentia. A patient who has this condition is an ideal candidate for LeFort partial colpocleisis. Bottom: Asymmetric anterior vaginal prolapse.

LeFort partial colpocleisis: Key step by key step

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

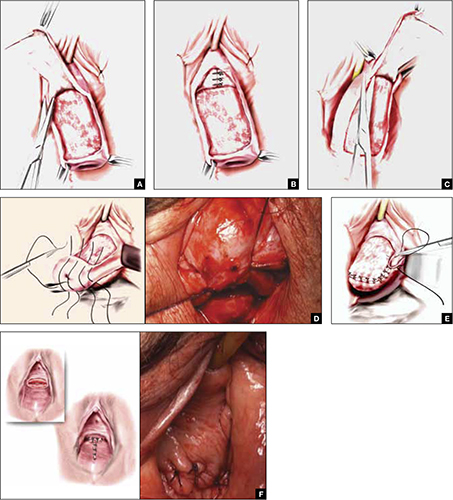

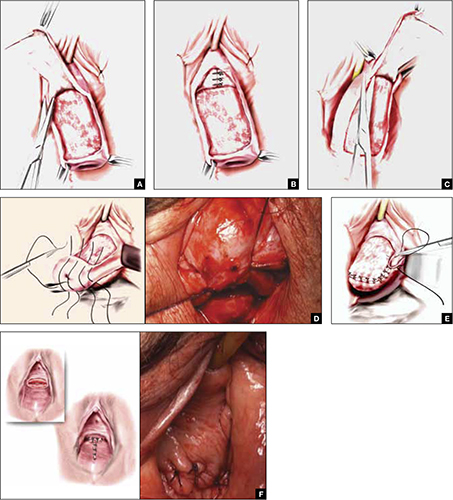

FIGURE 2 shows key steps in performing LeFort partial colpocleisis. See Video #1 at www.obgmanagement.com for demonstrations of how to perform LeFort partial colpocleisis.

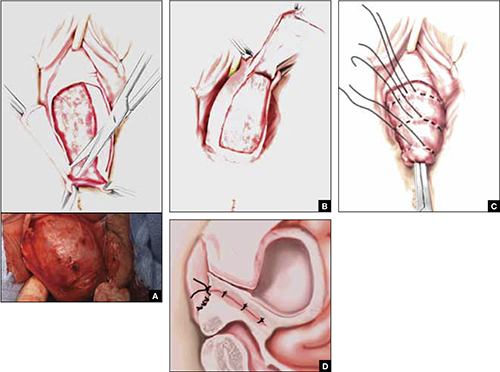

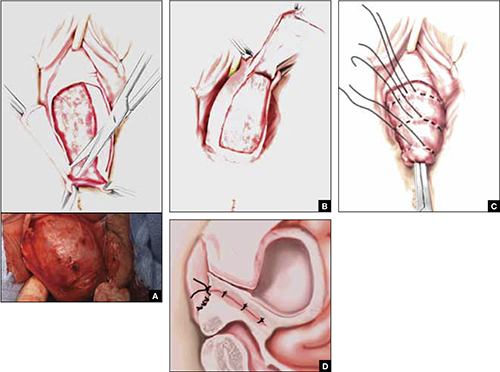

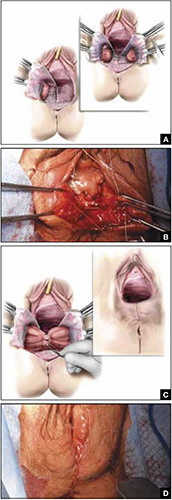

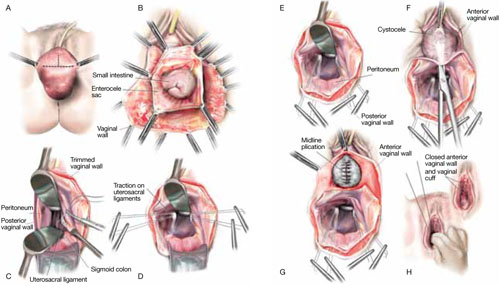

FIGURE 2 Steps: LeFort partial colpocleisis

A. Denude the anterior vaginal epithelium. B. Plicate the neck of the bladder. C. Next, denude the posterior vaginal epithelium. D. Approximate most proximal surfaces. E. Place lateral sutures to allow for drainage canals. F. The uterus has been replaced and most of the distal incisions closed.

Total colpectomy and colpocleisis: Key step by key step

In a patient who has post-hysterectomy prolapse and is not interested in continued sexual function, total colpectomy and colpocleisis provide a highly minimally invasive, durable option to correct her prolapse.

If there is complete eversion of the vagina then, truly, total colpectomy and colpocleisis is the procedure of choice. If there is significant prolapse of only one segment of the pelvic floor, however—for example, the anterior vaginal wall (FIGURE 1)—then aggressive repair of this variant with a narrowing down of the genital hiatus accomplishes the same result without requiring complete removal of what appears to be fairly well supported vaginal mucosa.

Here are key steps for performing partial or complete colpectomy and colpocleisis.

![]()

![]()

Completely remove the vaginal epithelium (FIGURES 3A and 3B); your goal is to leave most of the muscularis of the vaginal wall on the prolapse.

Avoid the peritoneal cavity if at all possible; when the main portion of the prolapse is secondary to an enterocele and the vaginal epithelium is very thin, however, formal excision of the enterocele sac, with closing of the defect, may be required.

![]()

If at all possible, avoid the peritoneum and the wall of the viscera, whether bladder or bowel. Invert the apex of the soft tissue, using the tip of forceps, as each purse-string suture is tied.

There is a variation of this procedure: Perform a separate anterior and posterior colporrhaphy, with two purse-string sutures used to approximate the anterior and posterior segments, thus obliterating any dead space.

![]()

![]()

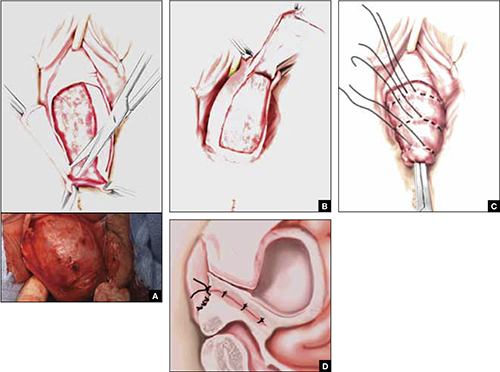

See Video #2 and Video #3 for a demonstration of how to perform a complete colpectomy and colpocleisis. FIGURE 3D shows the completed colpocleisis.

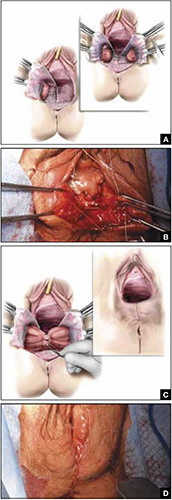

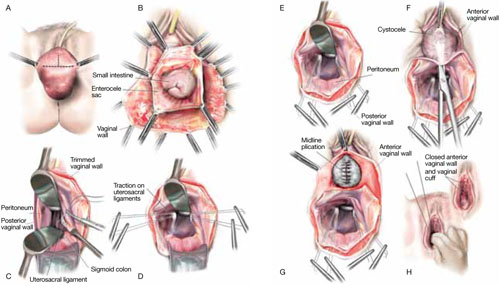

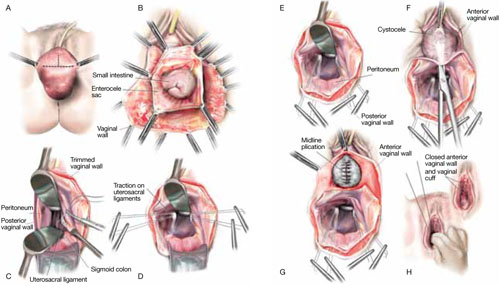

FIGURE 3 Steps: Total colpectomy and colpocleisis

Denude the anterior vaginal epithelium (A) and then the posterior epithelium (B). C. Place sequential purse-string sutures. D. The completed colpocleisis, in cross-section.

Distal levatoroplasty with high perineorrhaphy: Key step by key step

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

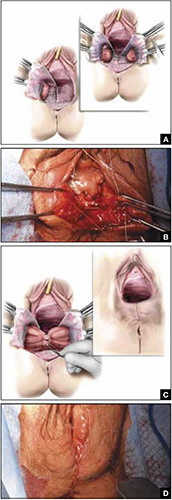

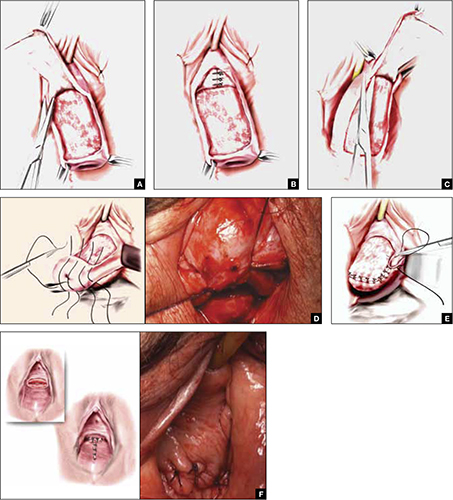

FIGURE 4 Steps: Distal levatoroplasty with high perineorrhaphy

A. Lateral dissection to the levator ani muscles. Inset: levator ani plicated with sequential sutures. B. Place three sutures to plicate the levator ani. C. Secure the plication sutures. Inset C, and D: Completed levatoroplasty.

Our experience

We are often asked questions about the procedures that we’ve just described, including patients’ satisfaction with the outcome, complications, and the risk that prolapse will recur. In the accompanying box, “Questions we’re asked (and answers we give) about obliterative surgery,” opposite, we give our responses to eight common inquiries.

about obliterative surgery

Q1 How satisfied are women with the outcome of these procedures—do many regret having their vaginal canal obliterated?

A Overall, studies indicate that 85% to 100% of patients are “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with the outcomes of obliterative procedures.1 There are rare reports of regret after colpocleisis over loss of coital ability; in one study of a series of procedures,2 5% of subjects expressed regret postoperatively.

Q2 Why is levatoroplasty and perineorrhaphy such an important part of both the LeFort partial colpocleisis and colpectomy and colpocleisis?

A The aim of both these procedures is to reduce prolapsed tissue. The true durability of repair comes from significantly decreasing the caliber of the genital hiatus, with the hope of closing off the bulk of the distal vaginal canal. This can really only be accomplished by utilizing an aggressive levatoroplasty and perineorrhaphy, described in the text.

Q3 How often do patients develop de novo stress incontinence or significant voiding dysfunction, or both, after an obliterative procedure?

A The risk of developing urinary incontinence after an obliterative procedure is difficult to ascertain. In general, patients who had retention or a high postvoid residual volume preoperatively have a good outcome in regard to correcting their voiding dysfunction. This is because, in most cases, the voiding dysfunction is directly related to the anatomic distortion created by the prolapse.

Q4 What is the rate of prolapse recurrence after these procedures, and how is a recurrence managed?

A Multiple studies have documented an excellent anatomic outcome after these procedures, with a prolapse recurrence rate of only 1% to 8%.3 Very little has been written about how to best manage recurrent prolapse after an obliterative procedure. Most surgeons would, most likely, recommend repeat colpocleisis or aggressive levatoroplasty and perineorrhaphy. (Note: The patient whose colpectomy and colpocleisis is shown in Video #3 failed two previous colpectomy and colpocleisis procedures.)

Q5 Can these procedures be performed under local anesthesia, with some intravenous sedation, or under regional anesthesia—thereby avoiding intubation?

A Yes. We have utilized IV sedation and bilateral block successfully to perform these procedures. (Note: Video #3 of LeFort partial colpocleisis shows the procedure performed under local anesthesia.)

Q6 What does the literature say about common complications after these procedures?

A Postoperative morbidity and mortality in the elderly surgical population is a considerable concern. Significant postoperative complications occur in approximately 5% of patients in modern series4—often attributed to the effects of age and to the frail condition of patients who are commonly selected for colpocleisis.

Specifically, approximately 5% of patients experience a postoperative cardiac, thromboembolic, pulmonary, or cerebrovascular event. Transfusion is the most commonly reported major complication related to the procedure itself. Other complications include:

- fever and its associated morbidity

- pneumonia

- ongoing vaginal bleeding

- pyelonephritis

- hematoma

- cystotomy

- ureteral occlusion.

Minor surgical complications occur at a rate of approximately 15%. Surgical mortality is about 1 in 400 cases.

Q7 Do you routinely undertake urodynamic study of patients who are scheduled to undergo an obliterative procedure?

A At minimum, a lower urinary tract evaluation should include a postvoid residual volume study and, we believe, some kind of a filling study and stress test, with reduction of the prolapse. Beyond that, we recommend that you conduct more detailed urodynamic tests on a patient-by-patient basis, when you think that the findings will add to the clinical picture.

Q8 Would you ever perform a vaginal hysterectomy and then proceed with a colpectomy and colpocleisis?

A The principal rationale for performing hysterectomy at the time of colpocleisis is to eliminate the risk of endometrial or cervical carcinoma. Hysterectomy also eliminates the risk of pyometra, a rare but serious complication that can occur when the lateral canals become obstructed after a LeFort procedure.

A recent study5 looked at 1) concomitant hysterectomy in conjunction with colpectomy and colpocleisis and 2) traditional LeFort partial colpocleisis. In this retrospective review, objective and subjective success rates were high, but patients who underwent hysterectomy had a statistically significantly greater decline in postoperative hematocrit and a significant increase in the need for transfusion, compared with patients who did not undergo hysterectomy (35% vs. 13%).

References

1. Fitzgerald MP, Richter HE, Bradley CS, et al. Pelvic support, pelvic symptoms and patient satisfaction after colpocleisis. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(12):1603-1609.

2. Hullfish K, Bobbjerg B, Steers W. Colpocleisis for pelvic organ prolapse Patient Goals Quality of life and Satisfaction. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 Pt 1):341-345.

3. Fitzgerald MP, Brubaker L. Colpocleisis and urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(5):1241-1244.

4. von Pechmann WS, Muton M, Fyffe J, Hale DS. Total colpocleisis with high levator placation for the treatment of advanced organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(1):121-126.

5. Kohli NE, Sze E, Karram M. Pyometra following LeFort colpocleisis. Int Urogyn J. 1996;7(5):264-266.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

- LeFort partial colpocleisis

- Colpectomy and colpocleisis

- Colpectomy and colpocleisis after two previously failed obliterative procedures

These videos were selected by Mickey Karram, MD, and are presented courtesy of the International Academy of Pelvic Surgery (IAPS)

This article, with accompanying video footage, is presented with the support of the International Academy of Pelvic Surgery.

As women live longer, on average, pelvic floor disorders are, as a whole, becoming more prevalent and a greater health and social problem. Many women entering the eighth and ninth decades of life display symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse (POP)—often after an unsuccessful trial of a pessary or even surgery.

These elderly patients often have other concomitant medical issues and are not sexually active, making extensive surgery for them less than an ideal solution. Instead, surgical procedures that obliterate the vaginal canal can alleviate their symptoms of POP.

In this article, we provide a step-by-step description of:

- LeFort partial colpocleisis in a woman who still has her uterus in place

- partial or complete colpectomy and colpocleisis in a woman who has post-hysterectomy prolapse

- levator plication and perineorrhaphy, as essential concluding steps in these procedures.

LeFort partial colpocleisis

An obliterative procedure in the form of a LeFort partial colpocleisis is an option when a patient 1) has her uterus and 2) is no longer sexually active. Because the uterus is retained in this procedure, however, keep in mind that it will be difficult to evaluate any uterine bleeding or cervical pathology in the future. Endovaginal ultrasonography or an endometrial biopsy, and a Pap smear, must be done before LeFort surgery.

The ideal candidate for LeFort partial colpocleisis is a woman who has complete uterine prolapse, or procidentia (FIGURE 1), which is characterized by symmetric eversion of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls.

FIGURE 1 Pelvic organ prolapse, preoperatively

Top: Uterine procidentia. A patient who has this condition is an ideal candidate for LeFort partial colpocleisis. Bottom: Asymmetric anterior vaginal prolapse.

LeFort partial colpocleisis: Key step by key step

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

FIGURE 2 shows key steps in performing LeFort partial colpocleisis. See Video #1 at www.obgmanagement.com for demonstrations of how to perform LeFort partial colpocleisis.

FIGURE 2 Steps: LeFort partial colpocleisis

A. Denude the anterior vaginal epithelium. B. Plicate the neck of the bladder. C. Next, denude the posterior vaginal epithelium. D. Approximate most proximal surfaces. E. Place lateral sutures to allow for drainage canals. F. The uterus has been replaced and most of the distal incisions closed.

Total colpectomy and colpocleisis: Key step by key step

In a patient who has post-hysterectomy prolapse and is not interested in continued sexual function, total colpectomy and colpocleisis provide a highly minimally invasive, durable option to correct her prolapse.

If there is complete eversion of the vagina then, truly, total colpectomy and colpocleisis is the procedure of choice. If there is significant prolapse of only one segment of the pelvic floor, however—for example, the anterior vaginal wall (FIGURE 1)—then aggressive repair of this variant with a narrowing down of the genital hiatus accomplishes the same result without requiring complete removal of what appears to be fairly well supported vaginal mucosa.

Here are key steps for performing partial or complete colpectomy and colpocleisis.

![]()

![]()

Completely remove the vaginal epithelium (FIGURES 3A and 3B); your goal is to leave most of the muscularis of the vaginal wall on the prolapse.

Avoid the peritoneal cavity if at all possible; when the main portion of the prolapse is secondary to an enterocele and the vaginal epithelium is very thin, however, formal excision of the enterocele sac, with closing of the defect, may be required.

![]()

If at all possible, avoid the peritoneum and the wall of the viscera, whether bladder or bowel. Invert the apex of the soft tissue, using the tip of forceps, as each purse-string suture is tied.

There is a variation of this procedure: Perform a separate anterior and posterior colporrhaphy, with two purse-string sutures used to approximate the anterior and posterior segments, thus obliterating any dead space.

![]()

![]()

See Video #2 and Video #3 for a demonstration of how to perform a complete colpectomy and colpocleisis. FIGURE 3D shows the completed colpocleisis.

FIGURE 3 Steps: Total colpectomy and colpocleisis

Denude the anterior vaginal epithelium (A) and then the posterior epithelium (B). C. Place sequential purse-string sutures. D. The completed colpocleisis, in cross-section.

Distal levatoroplasty with high perineorrhaphy: Key step by key step

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

FIGURE 4 Steps: Distal levatoroplasty with high perineorrhaphy

A. Lateral dissection to the levator ani muscles. Inset: levator ani plicated with sequential sutures. B. Place three sutures to plicate the levator ani. C. Secure the plication sutures. Inset C, and D: Completed levatoroplasty.

Our experience

We are often asked questions about the procedures that we’ve just described, including patients’ satisfaction with the outcome, complications, and the risk that prolapse will recur. In the accompanying box, “Questions we’re asked (and answers we give) about obliterative surgery,” opposite, we give our responses to eight common inquiries.

about obliterative surgery

Q1 How satisfied are women with the outcome of these procedures—do many regret having their vaginal canal obliterated?

A Overall, studies indicate that 85% to 100% of patients are “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with the outcomes of obliterative procedures.1 There are rare reports of regret after colpocleisis over loss of coital ability; in one study of a series of procedures,2 5% of subjects expressed regret postoperatively.

Q2 Why is levatoroplasty and perineorrhaphy such an important part of both the LeFort partial colpocleisis and colpectomy and colpocleisis?

A The aim of both these procedures is to reduce prolapsed tissue. The true durability of repair comes from significantly decreasing the caliber of the genital hiatus, with the hope of closing off the bulk of the distal vaginal canal. This can really only be accomplished by utilizing an aggressive levatoroplasty and perineorrhaphy, described in the text.

Q3 How often do patients develop de novo stress incontinence or significant voiding dysfunction, or both, after an obliterative procedure?

A The risk of developing urinary incontinence after an obliterative procedure is difficult to ascertain. In general, patients who had retention or a high postvoid residual volume preoperatively have a good outcome in regard to correcting their voiding dysfunction. This is because, in most cases, the voiding dysfunction is directly related to the anatomic distortion created by the prolapse.

Q4 What is the rate of prolapse recurrence after these procedures, and how is a recurrence managed?

A Multiple studies have documented an excellent anatomic outcome after these procedures, with a prolapse recurrence rate of only 1% to 8%.3 Very little has been written about how to best manage recurrent prolapse after an obliterative procedure. Most surgeons would, most likely, recommend repeat colpocleisis or aggressive levatoroplasty and perineorrhaphy. (Note: The patient whose colpectomy and colpocleisis is shown in Video #3 failed two previous colpectomy and colpocleisis procedures.)

Q5 Can these procedures be performed under local anesthesia, with some intravenous sedation, or under regional anesthesia—thereby avoiding intubation?

A Yes. We have utilized IV sedation and bilateral block successfully to perform these procedures. (Note: Video #3 of LeFort partial colpocleisis shows the procedure performed under local anesthesia.)

Q6 What does the literature say about common complications after these procedures?

A Postoperative morbidity and mortality in the elderly surgical population is a considerable concern. Significant postoperative complications occur in approximately 5% of patients in modern series4—often attributed to the effects of age and to the frail condition of patients who are commonly selected for colpocleisis.

Specifically, approximately 5% of patients experience a postoperative cardiac, thromboembolic, pulmonary, or cerebrovascular event. Transfusion is the most commonly reported major complication related to the procedure itself. Other complications include:

- fever and its associated morbidity

- pneumonia

- ongoing vaginal bleeding

- pyelonephritis

- hematoma

- cystotomy

- ureteral occlusion.

Minor surgical complications occur at a rate of approximately 15%. Surgical mortality is about 1 in 400 cases.

Q7 Do you routinely undertake urodynamic study of patients who are scheduled to undergo an obliterative procedure?

A At minimum, a lower urinary tract evaluation should include a postvoid residual volume study and, we believe, some kind of a filling study and stress test, with reduction of the prolapse. Beyond that, we recommend that you conduct more detailed urodynamic tests on a patient-by-patient basis, when you think that the findings will add to the clinical picture.

Q8 Would you ever perform a vaginal hysterectomy and then proceed with a colpectomy and colpocleisis?

A The principal rationale for performing hysterectomy at the time of colpocleisis is to eliminate the risk of endometrial or cervical carcinoma. Hysterectomy also eliminates the risk of pyometra, a rare but serious complication that can occur when the lateral canals become obstructed after a LeFort procedure.

A recent study5 looked at 1) concomitant hysterectomy in conjunction with colpectomy and colpocleisis and 2) traditional LeFort partial colpocleisis. In this retrospective review, objective and subjective success rates were high, but patients who underwent hysterectomy had a statistically significantly greater decline in postoperative hematocrit and a significant increase in the need for transfusion, compared with patients who did not undergo hysterectomy (35% vs. 13%).

References

1. Fitzgerald MP, Richter HE, Bradley CS, et al. Pelvic support, pelvic symptoms and patient satisfaction after colpocleisis. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(12):1603-1609.

2. Hullfish K, Bobbjerg B, Steers W. Colpocleisis for pelvic organ prolapse Patient Goals Quality of life and Satisfaction. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 Pt 1):341-345.

3. Fitzgerald MP, Brubaker L. Colpocleisis and urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(5):1241-1244.

4. von Pechmann WS, Muton M, Fyffe J, Hale DS. Total colpocleisis with high levator placation for the treatment of advanced organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(1):121-126.

5. Kohli NE, Sze E, Karram M. Pyometra following LeFort colpocleisis. Int Urogyn J. 1996;7(5):264-266.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

- LeFort partial colpocleisis

- Colpectomy and colpocleisis

- Colpectomy and colpocleisis after two previously failed obliterative procedures

These videos were selected by Mickey Karram, MD, and are presented courtesy of the International Academy of Pelvic Surgery (IAPS)

This article, with accompanying video footage, is presented with the support of the International Academy of Pelvic Surgery.

As women live longer, on average, pelvic floor disorders are, as a whole, becoming more prevalent and a greater health and social problem. Many women entering the eighth and ninth decades of life display symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse (POP)—often after an unsuccessful trial of a pessary or even surgery.

These elderly patients often have other concomitant medical issues and are not sexually active, making extensive surgery for them less than an ideal solution. Instead, surgical procedures that obliterate the vaginal canal can alleviate their symptoms of POP.

In this article, we provide a step-by-step description of:

- LeFort partial colpocleisis in a woman who still has her uterus in place

- partial or complete colpectomy and colpocleisis in a woman who has post-hysterectomy prolapse

- levator plication and perineorrhaphy, as essential concluding steps in these procedures.

LeFort partial colpocleisis

An obliterative procedure in the form of a LeFort partial colpocleisis is an option when a patient 1) has her uterus and 2) is no longer sexually active. Because the uterus is retained in this procedure, however, keep in mind that it will be difficult to evaluate any uterine bleeding or cervical pathology in the future. Endovaginal ultrasonography or an endometrial biopsy, and a Pap smear, must be done before LeFort surgery.

The ideal candidate for LeFort partial colpocleisis is a woman who has complete uterine prolapse, or procidentia (FIGURE 1), which is characterized by symmetric eversion of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls.

FIGURE 1 Pelvic organ prolapse, preoperatively

Top: Uterine procidentia. A patient who has this condition is an ideal candidate for LeFort partial colpocleisis. Bottom: Asymmetric anterior vaginal prolapse.

LeFort partial colpocleisis: Key step by key step

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

FIGURE 2 shows key steps in performing LeFort partial colpocleisis. See Video #1 at www.obgmanagement.com for demonstrations of how to perform LeFort partial colpocleisis.

FIGURE 2 Steps: LeFort partial colpocleisis

A. Denude the anterior vaginal epithelium. B. Plicate the neck of the bladder. C. Next, denude the posterior vaginal epithelium. D. Approximate most proximal surfaces. E. Place lateral sutures to allow for drainage canals. F. The uterus has been replaced and most of the distal incisions closed.

Total colpectomy and colpocleisis: Key step by key step

In a patient who has post-hysterectomy prolapse and is not interested in continued sexual function, total colpectomy and colpocleisis provide a highly minimally invasive, durable option to correct her prolapse.

If there is complete eversion of the vagina then, truly, total colpectomy and colpocleisis is the procedure of choice. If there is significant prolapse of only one segment of the pelvic floor, however—for example, the anterior vaginal wall (FIGURE 1)—then aggressive repair of this variant with a narrowing down of the genital hiatus accomplishes the same result without requiring complete removal of what appears to be fairly well supported vaginal mucosa.

Here are key steps for performing partial or complete colpectomy and colpocleisis.

![]()

![]()

Completely remove the vaginal epithelium (FIGURES 3A and 3B); your goal is to leave most of the muscularis of the vaginal wall on the prolapse.

Avoid the peritoneal cavity if at all possible; when the main portion of the prolapse is secondary to an enterocele and the vaginal epithelium is very thin, however, formal excision of the enterocele sac, with closing of the defect, may be required.

![]()

If at all possible, avoid the peritoneum and the wall of the viscera, whether bladder or bowel. Invert the apex of the soft tissue, using the tip of forceps, as each purse-string suture is tied.

There is a variation of this procedure: Perform a separate anterior and posterior colporrhaphy, with two purse-string sutures used to approximate the anterior and posterior segments, thus obliterating any dead space.

![]()

![]()

See Video #2 and Video #3 for a demonstration of how to perform a complete colpectomy and colpocleisis. FIGURE 3D shows the completed colpocleisis.

FIGURE 3 Steps: Total colpectomy and colpocleisis

Denude the anterior vaginal epithelium (A) and then the posterior epithelium (B). C. Place sequential purse-string sutures. D. The completed colpocleisis, in cross-section.

Distal levatoroplasty with high perineorrhaphy: Key step by key step

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

FIGURE 4 Steps: Distal levatoroplasty with high perineorrhaphy

A. Lateral dissection to the levator ani muscles. Inset: levator ani plicated with sequential sutures. B. Place three sutures to plicate the levator ani. C. Secure the plication sutures. Inset C, and D: Completed levatoroplasty.

Our experience

We are often asked questions about the procedures that we’ve just described, including patients’ satisfaction with the outcome, complications, and the risk that prolapse will recur. In the accompanying box, “Questions we’re asked (and answers we give) about obliterative surgery,” opposite, we give our responses to eight common inquiries.

about obliterative surgery

Q1 How satisfied are women with the outcome of these procedures—do many regret having their vaginal canal obliterated?

A Overall, studies indicate that 85% to 100% of patients are “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with the outcomes of obliterative procedures.1 There are rare reports of regret after colpocleisis over loss of coital ability; in one study of a series of procedures,2 5% of subjects expressed regret postoperatively.

Q2 Why is levatoroplasty and perineorrhaphy such an important part of both the LeFort partial colpocleisis and colpectomy and colpocleisis?

A The aim of both these procedures is to reduce prolapsed tissue. The true durability of repair comes from significantly decreasing the caliber of the genital hiatus, with the hope of closing off the bulk of the distal vaginal canal. This can really only be accomplished by utilizing an aggressive levatoroplasty and perineorrhaphy, described in the text.

Q3 How often do patients develop de novo stress incontinence or significant voiding dysfunction, or both, after an obliterative procedure?

A The risk of developing urinary incontinence after an obliterative procedure is difficult to ascertain. In general, patients who had retention or a high postvoid residual volume preoperatively have a good outcome in regard to correcting their voiding dysfunction. This is because, in most cases, the voiding dysfunction is directly related to the anatomic distortion created by the prolapse.

Q4 What is the rate of prolapse recurrence after these procedures, and how is a recurrence managed?

A Multiple studies have documented an excellent anatomic outcome after these procedures, with a prolapse recurrence rate of only 1% to 8%.3 Very little has been written about how to best manage recurrent prolapse after an obliterative procedure. Most surgeons would, most likely, recommend repeat colpocleisis or aggressive levatoroplasty and perineorrhaphy. (Note: The patient whose colpectomy and colpocleisis is shown in Video #3 failed two previous colpectomy and colpocleisis procedures.)

Q5 Can these procedures be performed under local anesthesia, with some intravenous sedation, or under regional anesthesia—thereby avoiding intubation?

A Yes. We have utilized IV sedation and bilateral block successfully to perform these procedures. (Note: Video #3 of LeFort partial colpocleisis shows the procedure performed under local anesthesia.)

Q6 What does the literature say about common complications after these procedures?

A Postoperative morbidity and mortality in the elderly surgical population is a considerable concern. Significant postoperative complications occur in approximately 5% of patients in modern series4—often attributed to the effects of age and to the frail condition of patients who are commonly selected for colpocleisis.

Specifically, approximately 5% of patients experience a postoperative cardiac, thromboembolic, pulmonary, or cerebrovascular event. Transfusion is the most commonly reported major complication related to the procedure itself. Other complications include:

- fever and its associated morbidity

- pneumonia

- ongoing vaginal bleeding

- pyelonephritis

- hematoma

- cystotomy

- ureteral occlusion.

Minor surgical complications occur at a rate of approximately 15%. Surgical mortality is about 1 in 400 cases.

Q7 Do you routinely undertake urodynamic study of patients who are scheduled to undergo an obliterative procedure?

A At minimum, a lower urinary tract evaluation should include a postvoid residual volume study and, we believe, some kind of a filling study and stress test, with reduction of the prolapse. Beyond that, we recommend that you conduct more detailed urodynamic tests on a patient-by-patient basis, when you think that the findings will add to the clinical picture.

Q8 Would you ever perform a vaginal hysterectomy and then proceed with a colpectomy and colpocleisis?

A The principal rationale for performing hysterectomy at the time of colpocleisis is to eliminate the risk of endometrial or cervical carcinoma. Hysterectomy also eliminates the risk of pyometra, a rare but serious complication that can occur when the lateral canals become obstructed after a LeFort procedure.

A recent study5 looked at 1) concomitant hysterectomy in conjunction with colpectomy and colpocleisis and 2) traditional LeFort partial colpocleisis. In this retrospective review, objective and subjective success rates were high, but patients who underwent hysterectomy had a statistically significantly greater decline in postoperative hematocrit and a significant increase in the need for transfusion, compared with patients who did not undergo hysterectomy (35% vs. 13%).

References

1. Fitzgerald MP, Richter HE, Bradley CS, et al. Pelvic support, pelvic symptoms and patient satisfaction after colpocleisis. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(12):1603-1609.

2. Hullfish K, Bobbjerg B, Steers W. Colpocleisis for pelvic organ prolapse Patient Goals Quality of life and Satisfaction. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 Pt 1):341-345.

3. Fitzgerald MP, Brubaker L. Colpocleisis and urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(5):1241-1244.

4. von Pechmann WS, Muton M, Fyffe J, Hale DS. Total colpocleisis with high levator placation for the treatment of advanced organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(1):121-126.

5. Kohli NE, Sze E, Karram M. Pyometra following LeFort colpocleisis. Int Urogyn J. 1996;7(5):264-266.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

High uterosacral vaginal vault suspension to repair enterocele and apical prolapse

- Pelvic anatomy of high intraperitoneal vaginal vault suspension

- Anatomy of the uterosacral ligament

- High uterosacral suspension (complete uterine procidentia)

- High uterosacral suspension (post-hysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse)

These videos were selected by Mickey Karram, MD, and Christine Vaccaro, DO, and are presented courtesy of the International Academy of Pelvic Surgery (IAPS).

This article, with accompanying video footage, is presented with the support of the International Academy of Pelvic Surgery.

The concept of utilizing the uterosacral ligaments to support the vaginal cuff and correct an enterocele is nothing new: As early as 1957, Milton McCall described what became known as the McCall culdoplasty, in which sutures incorporated the uterosacral ligaments into the posterior vaginal vault to obliterate the cul-de-sac and suspend or support the vaginal apex at the time of vaginal hysterectomy.1

Later, in the 1990s, Richardson promoted the concept that, in patients who have pelvic organ prolapse, the uterosacral ligaments do not become attenuated, instead, they break at specific points.

Shull and colleagues took this idea and described how utilizing uterosacral ligaments to support the vaginal cuff can be performed vaginally—by passing sutures bilaterally through the uterosacral ligaments near the level of the ischial spine.2

Since Shull described this procedure, numerous published studies have demonstrated outcomes similar to other vaginal suspension procedures, such as sacrospinous ligament suspension.3-5

Potential advantages of a high uterosacral vaginal vault suspension are that:

- it provides good apical support without significantly distorting the vaginal axis, making it applicable to all types of vaginal prolapse

- intraperitoneal passage of sutures can be a lot cleaner and simpler than passing sutures, or anchors, through retroperitoneal structures, such as the sacrospinous ligament (FIGURE 1).

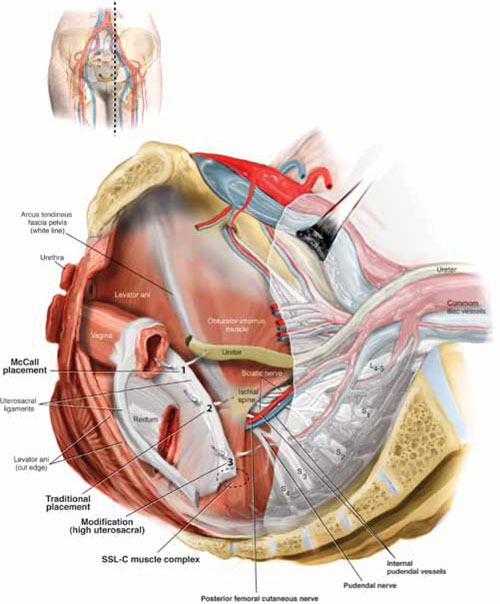

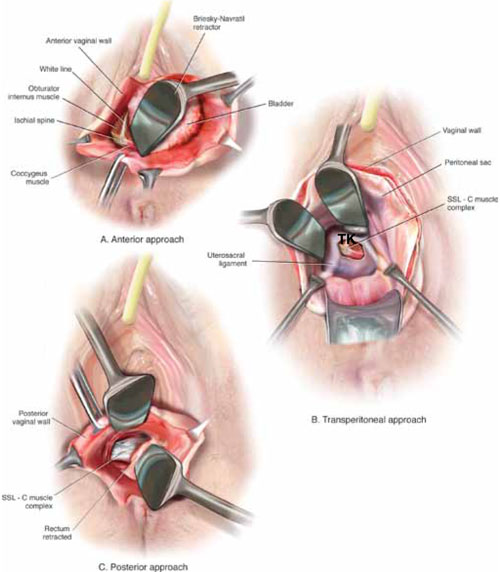

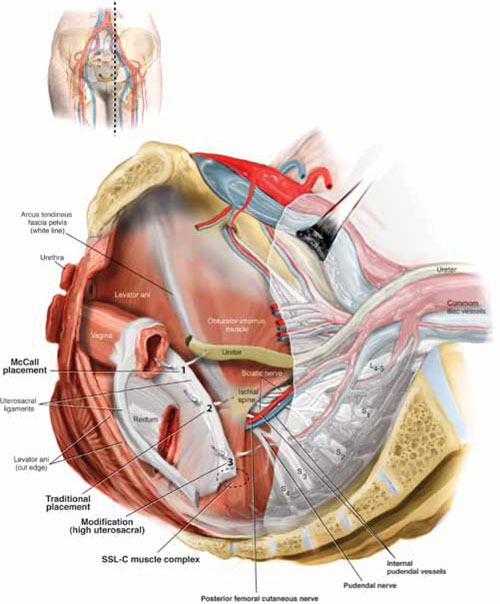

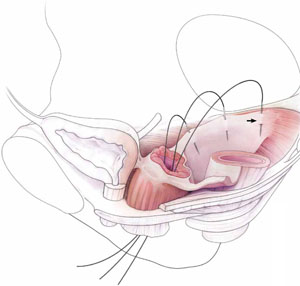

FIGURE 1 Locating intraperitoneal sutures during uterosacral suspension

Cross-section of the pelvic floor shows where sutures are placed as part of McCall culdoplasty (1), traditional uterosacral suspension (2), and modified high uterosacral suspension (3). Note: High uterosacral suspension may involve passing the suture through the sacrospinous ligament–coccygeus (SSL-C) muscle complex (dashed oval) because a segment of the uterosacral ligament inserts into that structure.

A disadvantage of the procedure is that the uterosacral ligament may, at times, lie in close proximity to the ureter. Studies have shown that the ureter can become kinked when sutures in this procedure are passed too far laterally.2-5

High uterosacral suspension has been our operation of choice for 11 years for patients who have pelvic organ prolapse in which the peritoneum is accessible (see “How this procedure evolved in our hands”). In this article, we provide a step-by-step description of the procedure. Four accompanying videos that further illuminate those steps are noted in the text here at appropriate places.(For example, Video #1, immediately below, sets the stage for the step-by-step discussion by reviewing pertinent pelvic anatomy.)

- When we first performed high uterosacral vaginal vault suspension as described by Shull and colleagues,1 we mobilized vaginal muscularis off the epithelium and suspended the epithelium and muscularis separately, making sure that sutures were passed through the anterior and Posterior vaginal walls.

- Initially, we thought that a large cul-de-sac needed to be obliterated in the midline with internal McCall-type stitches that were separate and distinct from the uterosacral suspension sutures. We no longer do this routinely because we believe that the numerous sutures that are passed through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall, including the peritoneum, effectively obliterate the enterocele and keep down the incidence of recurrent enterocele and high rectocele.

- We have come to realize that sutures placed medial and cephalad to the ischial spine are often passed through a portion of the coccygeus muscle-sacrospinous ligament complex. At times, a small window can be made in the peritoneum that provides direct access to this complex (FIGURE 1; FIGURE 3).

References

1. Shull BL, Bachofen C, Coates KW, Kuehl TJ. A transvaginal approach to repair of apical and other associated sites of pelvic organ prolapse with uterosacral ligaments. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(6):1365-1374.

1. Enter the peritoneum

It’s our opinion that, even though extraperitoneal uterosacral suspension procedures have been described, the pertinent anatomic structures (again, see Video #1) are not easily identifiable unless suspension is undertaken intraperitoneally. Entering the peritoneum is, obviously, not a concern if the patient is undergoing vaginal hysterectomy. If the patient has post-hysterectomy prolapse, however, you must be able to isolate an enterocele and enter the peritoneum (follow FIGURE 2, beginning here and through subsequent steps of the procedure).

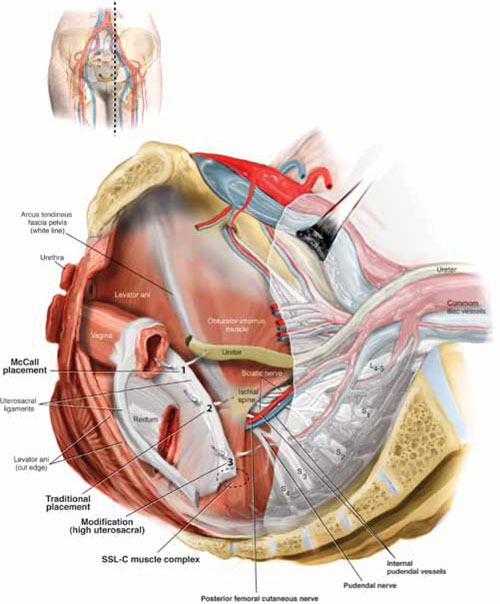

FIGURE 2 Step by step: High uterosacral vaginal vault suspension

A The most prominent portion of the prolapsed vaginal vault is grasped with two Allis clamps. B The vaginal wall is opened up and the enterocele sac is identified and entered. C The bowel is packed high into the pelvis using large laparotomy sponges. The retractor lifts the sponges out of the lower pelvis, thus completely exposing the cul-de-sac. When appropriate traction is placed downward on the uterosacral ligaments with an Allis clamp, the uterosacral ligaments are easily palpated bilaterally. D Delayed absorbable sutures have been passed through the uppermost portion of the uterosacral ligaments on each side, and have been individually tagged.

E Each end of the previously passed sutures is brought out through the posterior peritoneum and the posterior vaginal wall. (A free needle is used to pass both ends of these delayed absorbable sutures through the full thickness of the vaginal wall.) F Anterior colporrhaphy is begun by initiating dissection between the prolapsed bladder and the anterior vaginal wall. G Anterior colporrhaphy is complete. H The vagina has been appropriately trimmed and closed with interrupted or continuous delayed absorbable sutures. Delayed absorbable sutures that were previously brought out through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall are then tied; doing so elevates the prolapsed vaginal vault high up into the hollow of the sacrum.Once you have entered the peritoneum, the cul-de-sac must be relatively free of adhesive disease if you are to be able to continue with this procedure. (See “5 surgical pearls for high ureterosacral vaginal vault suspension”)

- Be prepared to convert to a sacrospinous fixation if you cannot enter the enterocele sac or if the posterior cul-de-sac is obliterated with adhesions

- Pass the sutures through durable tissue so that, when traction is placed on the sutures, there is minimal movement of peritoneum. Doing so might avoid kinking of the ureter.

- Pass the sutures through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall, including the peritoneum. Doing so not only suspends the apex but tremendously facilitates support for the posterior vaginal wall (FIGURE 4).

- When prolapse is very large, excise redundant portions of the upper part of the posterior vaginal wall and peritoneum—making sure, however, that you keep all layers together for performing the suspension. (See VIDEO #4, showing high uterosacral suspension in a patient who has complete uterine procidentia.)

- Do not try to pass a ureteral stent if you do not see indigo carmine dye spill from the ureteral orifices; to do so can be difficult after repair of prolapse, even in the hands of a skilled urologist. It is best instead to:

- identify the offending suture

- cut it

- visualize the spill of dye-colored urine

- proceed with either replacing the cut suture or maintaining the suspension with other, remaining sutures.

In our experience, when we have also performed an anterior repair, the ureter is kinked in at least 50% of cases because of one of the sutures that was used to correct the cystocele.

2. Pack the bowel; expose the uterosacral ligaments

Next, pack the small bowel out of the cul-de-sac to allow easy access and visualization of the uppermost portions of the uterosacral ligament. This is best accomplished by passing large, moistened laparotomy sponges intraperitoneally and elevating them with a large retractor (e.g., Deaver, Breisky-Navrital, Sweetheart).

When the bowel is appropriately packed, the retractor lifts the intestinal contents out of the pelvis, usually allowing easy access to the proximal or uppermost portion of the uterosacral ligaments (see Video #3, which focuses on the anatomy of the uterosacral ligament).

When performing high uterosacral suspension, it is possible to pass sutures through the coccygeus muscle-sacrospinous ligament complex (arrow) because a segment of the uterosacral ligament inserts into that structure.

3. Palpate the ischial spines bilaterally

It’s important that you palpate the ischial spines. Often, the ureter can be palpated against the pelvic sidewall. If you palpate the ischial spines and continue to palpate medially and cephalad, you can usually palpate the coccygeus muscle-sacrospinous ligament complex transperitoneally because a portion of the uterosacral ligament inserts into the sacrospinous ligament.6

If sutures can be passed at this level, the result will (usually) be a vagina that is, at minimum, approximately 9 cm long.

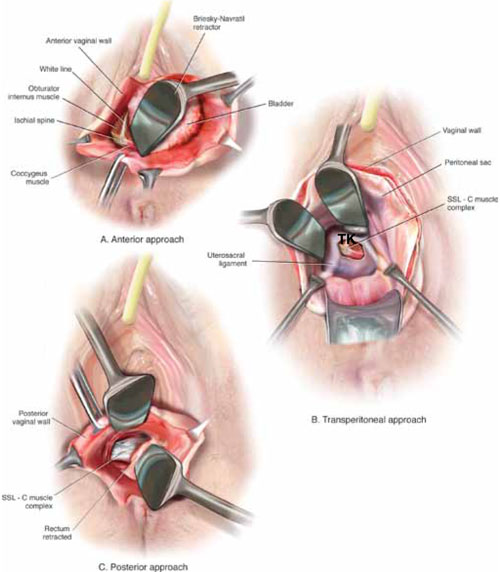

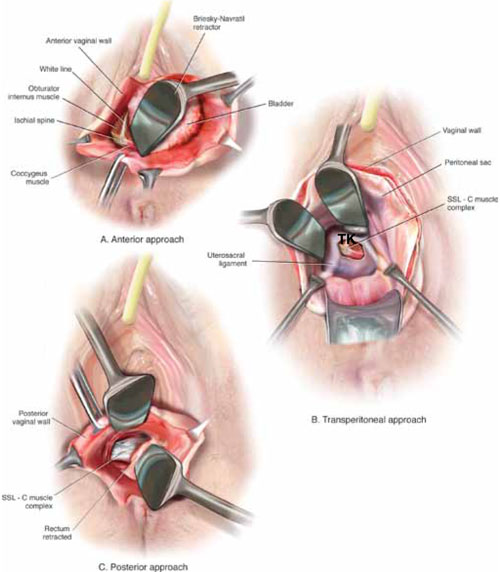

FIGURE 3 Access to the sacrospinous ligament

The sacrospinous ligament can be palpated and exposed along any one of three approaches: anterior paravaginally (A), transperitoneally (B), and posterior pararectally (C).

4. Pass the sutures

We prefer to pass two or three sutures on each side, utilizing a long, straight needle holder. Because we eventually pass the sutures through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall, we’ve opted for a delayed absorbable suture—preferably, 0 Vicryl on a CT-2 needle.

A Breisky-Navrital retractor is utilized to retract the sigmoid colon in the opposite direction of the ligament in which the sutures are being passed. At times, attaching a light to a suction device or a retractor is also helpful to visualize this area.

Use an Allis clamp to elevate and apply traction on the distal uterosacral ligament; this facilitates palpation and visualization of the appropriate site for placement of the sutures. The exact area of suture passage is best identified by palpation.

(Note: In early descriptions of this procedure, permanent sutures were utilized; again, we use delayed absorbable sutures because all sutures are brought out through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall. Permanent suture in our approach would be unacceptable because the sutures are tied in the lumen of the vagina. In some other modifications of this procedure, sutures are passed through the muscular layer of the vagina to exclude epithelium; under those circumstances, permanent sutures can be utilized.)

Once the sutures are brought through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall—including the peritoneum, if possible—tag them individually. If the anterior segment is well-supported, close the vaginal incision with a continuous delayed absorbable suture.

Tie the suspension sutures, elevating the apex into the hollow of the sacrum.

If anterior colporrhaphy is needed, perform that repair. Close the anterior vaginal wall as well as the vaginal cuff before tying off the suspension sutures.

5. Ensure that the ureters are patent

After the sutures are tied, instruct the anesthesiologist to administer 5 cc of indigo carmine dye intravenously. Assuming no renal compromise, you should see dye in the bladder 5 to 10 minutes later. If the patient is elderly or if you want to expedite this step, furosemide, 5 to 10 mg, can be given by IV push.

Next, perform cystoscopy to ensure ureteral patency. You should observe a spill of dye-colored urine out of both ureteral orifices. If dye does not spill from either orifice after a reasonable wait (usually, 20 minutes), assume that the ureter on that side is obstructed.

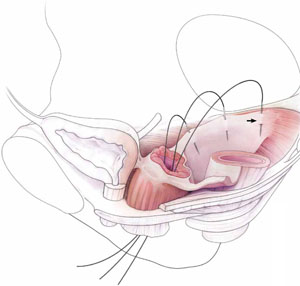

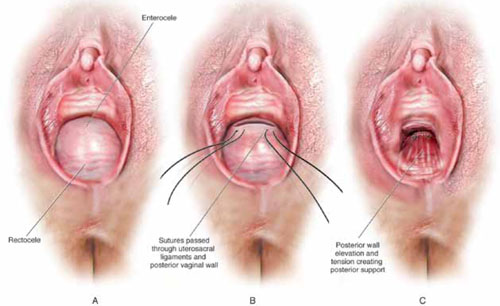

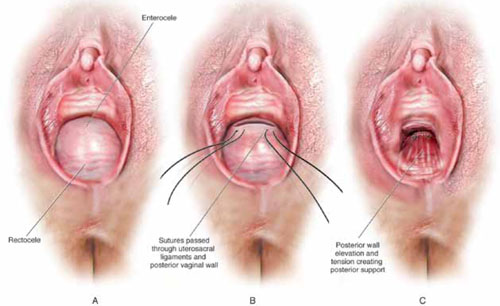

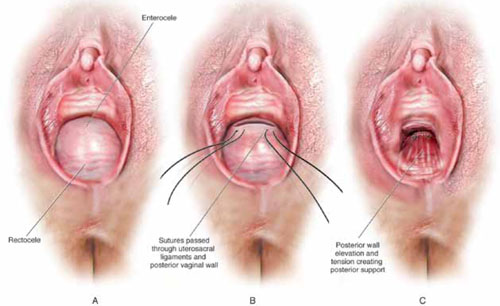

FIGURE 4 Providing support for the posterior vaginal wall

A View of a posterior vaginal wall defect secondary to an enterocele and rectocele. B After entry into the enterocele sac, intraperitoneal suspension sutures are brought out through the full thickness of the vaginal wall at the level of the apex. C Tying these sutures after the vaginal incision is closed at the apex not only results in greater vaginal length but also contributes to overall support of the entire posterior vaginal wall.

6. Completely reconstruct the vagina

The remainder of steps required to complete the procedure usually involve posterior colporrhaphy and perineoplasty. We also reserve placement of a synthetic midurethral sling (if one is needed) until after the vault procedure is complete.

Refer to FIGURE 2 for a step-by step guide to how best to perform high uterosacral vaginal vault suspension.

Questions often asked about this procedure

What do I do if I can’t isolate an enterocele sac and enter it?

Perform a unilateral or bilateral sacrospinous ligament colpopexy.

Is it always possible to identify a usable uterosacral ligament in patients who have advanced prolapse?

We’ve found it extremely rare not to be able identify a usable and durable structure.

The trick to identifying the ligament is to pass an Allis clamp so that one end is positioned intraperitoneally, as high up as possible, and the other end is on the vaginal mucosa side. Elevating the clamp puts the ligament on tension. These clamps are usually placed between 4 and 5 o’clock on the left side and between 7 and 8 o’clock on the right side.

With appropriate traction, the ligament can usually be easily palpated.

If I don’t see indigo carmine dye spilling from one side during cystoscopy, what sequence of events should I undertake?

If the only sutures placed on that side were the uterosacral ligament sutures, cut them individually. If the ureter spills dye after a suture is cut, decide whether you think it is appropriate to replace that suture. Sometimes, unilateral suspension or a suspension with one remaining suture on the side where you cut a suture or two is sufficient.

If you do want to replace a cut suture, ureteral patency must be confirmed again after it is replaced.

No further management of the ureter is required—that is, it isn’t necessary to catheterize the ureter or perform postoperative imaging studies. If anterior colporrhaphy has also been performed, however, apply your highest index of suspicion to determine the source of the offending suture: the uterosacral suspension or the anterior repair.*

If the patient has severe hip or leg pain postoperatively, what should I suspect is wrong? How should I manage this complication?

The nerve to the levator ani runs within the coccygeus muscle. In a thin patient, in whom deep bites are taken, the nerve is often injured or trapped. Such trauma can cause hip pain that is fairly severe but that is almost always self-limiting and requires only nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication. Usually, this complication resolves within 2 weeks after surgery.

Significant postoperative pain that radiates down the back of the thigh or down the leg all the way to the foot is of greater concern because one of the sacral nerve segments has most likely been injured or stretched. Obtain a neurology consult; rarely, it becomes necessary to take the patient back to surgery to cut the offending suture.

*For detailed discussion of this subject, see the International Academy of Pelvic Surgery’s August 2010 “Case of the month” at www.academyofpelvicsurgery.com.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. McCall ML. Posterior culdeplasty; surgical correction of enterocele during vaginal hysterectomy; a preliminary report. Obstet Gynecol. 1957;10(6):595-602.

2. Shull BL, Bachofen C, Coates KW, Kuehl TJ. A transvaginal approach to repair of apical and other associated sites of pelvic organ prolapse with uterosacral ligaments. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(6):1365-1374.

3. Barber MD, Visco AG, Weidner AC, Amundsen CL, Bump RC. Bilateral uterosacral ligament vaginal vault suspension with site-specific endopelvic fascia defect repair for treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(6):1402-1411.

4. Karram M, Goldwasser S, Kleeman S, Steele A, Vassallo B, Walsh P. High uterosacral vaginal vault suspension with fascial reconstruction for vaginal repair of enterocele and vaginal vault prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185(6):1339-1343.

5. Silva WA, Pauls RN, Segal JL, Rooney CM, Kleeman SD, Karram MM. Uterosacral ligament vault suspension: five-year outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(2):255-263.

6. Umek WH, Morgan DM, Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JOL. Quantitative analysis of uterosacral ligament origin and insertion points by magnetic resonance imaging. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;13(3):447-451.

- Pelvic anatomy of high intraperitoneal vaginal vault suspension

- Anatomy of the uterosacral ligament

- High uterosacral suspension (complete uterine procidentia)

- High uterosacral suspension (post-hysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse)

These videos were selected by Mickey Karram, MD, and Christine Vaccaro, DO, and are presented courtesy of the International Academy of Pelvic Surgery (IAPS).

This article, with accompanying video footage, is presented with the support of the International Academy of Pelvic Surgery.

The concept of utilizing the uterosacral ligaments to support the vaginal cuff and correct an enterocele is nothing new: As early as 1957, Milton McCall described what became known as the McCall culdoplasty, in which sutures incorporated the uterosacral ligaments into the posterior vaginal vault to obliterate the cul-de-sac and suspend or support the vaginal apex at the time of vaginal hysterectomy.1

Later, in the 1990s, Richardson promoted the concept that, in patients who have pelvic organ prolapse, the uterosacral ligaments do not become attenuated, instead, they break at specific points.

Shull and colleagues took this idea and described how utilizing uterosacral ligaments to support the vaginal cuff can be performed vaginally—by passing sutures bilaterally through the uterosacral ligaments near the level of the ischial spine.2

Since Shull described this procedure, numerous published studies have demonstrated outcomes similar to other vaginal suspension procedures, such as sacrospinous ligament suspension.3-5

Potential advantages of a high uterosacral vaginal vault suspension are that:

- it provides good apical support without significantly distorting the vaginal axis, making it applicable to all types of vaginal prolapse

- intraperitoneal passage of sutures can be a lot cleaner and simpler than passing sutures, or anchors, through retroperitoneal structures, such as the sacrospinous ligament (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1 Locating intraperitoneal sutures during uterosacral suspension

Cross-section of the pelvic floor shows where sutures are placed as part of McCall culdoplasty (1), traditional uterosacral suspension (2), and modified high uterosacral suspension (3). Note: High uterosacral suspension may involve passing the suture through the sacrospinous ligament–coccygeus (SSL-C) muscle complex (dashed oval) because a segment of the uterosacral ligament inserts into that structure.

A disadvantage of the procedure is that the uterosacral ligament may, at times, lie in close proximity to the ureter. Studies have shown that the ureter can become kinked when sutures in this procedure are passed too far laterally.2-5

High uterosacral suspension has been our operation of choice for 11 years for patients who have pelvic organ prolapse in which the peritoneum is accessible (see “How this procedure evolved in our hands”). In this article, we provide a step-by-step description of the procedure. Four accompanying videos that further illuminate those steps are noted in the text here at appropriate places.(For example, Video #1, immediately below, sets the stage for the step-by-step discussion by reviewing pertinent pelvic anatomy.)

- When we first performed high uterosacral vaginal vault suspension as described by Shull and colleagues,1 we mobilized vaginal muscularis off the epithelium and suspended the epithelium and muscularis separately, making sure that sutures were passed through the anterior and Posterior vaginal walls.

- Initially, we thought that a large cul-de-sac needed to be obliterated in the midline with internal McCall-type stitches that were separate and distinct from the uterosacral suspension sutures. We no longer do this routinely because we believe that the numerous sutures that are passed through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall, including the peritoneum, effectively obliterate the enterocele and keep down the incidence of recurrent enterocele and high rectocele.

- We have come to realize that sutures placed medial and cephalad to the ischial spine are often passed through a portion of the coccygeus muscle-sacrospinous ligament complex. At times, a small window can be made in the peritoneum that provides direct access to this complex (FIGURE 1; FIGURE 3).

References

1. Shull BL, Bachofen C, Coates KW, Kuehl TJ. A transvaginal approach to repair of apical and other associated sites of pelvic organ prolapse with uterosacral ligaments. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(6):1365-1374.

1. Enter the peritoneum

It’s our opinion that, even though extraperitoneal uterosacral suspension procedures have been described, the pertinent anatomic structures (again, see Video #1) are not easily identifiable unless suspension is undertaken intraperitoneally. Entering the peritoneum is, obviously, not a concern if the patient is undergoing vaginal hysterectomy. If the patient has post-hysterectomy prolapse, however, you must be able to isolate an enterocele and enter the peritoneum (follow FIGURE 2, beginning here and through subsequent steps of the procedure).

FIGURE 2 Step by step: High uterosacral vaginal vault suspension

A The most prominent portion of the prolapsed vaginal vault is grasped with two Allis clamps. B The vaginal wall is opened up and the enterocele sac is identified and entered. C The bowel is packed high into the pelvis using large laparotomy sponges. The retractor lifts the sponges out of the lower pelvis, thus completely exposing the cul-de-sac. When appropriate traction is placed downward on the uterosacral ligaments with an Allis clamp, the uterosacral ligaments are easily palpated bilaterally. D Delayed absorbable sutures have been passed through the uppermost portion of the uterosacral ligaments on each side, and have been individually tagged.

E Each end of the previously passed sutures is brought out through the posterior peritoneum and the posterior vaginal wall. (A free needle is used to pass both ends of these delayed absorbable sutures through the full thickness of the vaginal wall.) F Anterior colporrhaphy is begun by initiating dissection between the prolapsed bladder and the anterior vaginal wall. G Anterior colporrhaphy is complete. H The vagina has been appropriately trimmed and closed with interrupted or continuous delayed absorbable sutures. Delayed absorbable sutures that were previously brought out through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall are then tied; doing so elevates the prolapsed vaginal vault high up into the hollow of the sacrum.Once you have entered the peritoneum, the cul-de-sac must be relatively free of adhesive disease if you are to be able to continue with this procedure. (See “5 surgical pearls for high ureterosacral vaginal vault suspension”)

- Be prepared to convert to a sacrospinous fixation if you cannot enter the enterocele sac or if the posterior cul-de-sac is obliterated with adhesions

- Pass the sutures through durable tissue so that, when traction is placed on the sutures, there is minimal movement of peritoneum. Doing so might avoid kinking of the ureter.

- Pass the sutures through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall, including the peritoneum. Doing so not only suspends the apex but tremendously facilitates support for the posterior vaginal wall (FIGURE 4).

- When prolapse is very large, excise redundant portions of the upper part of the posterior vaginal wall and peritoneum—making sure, however, that you keep all layers together for performing the suspension. (See VIDEO #4, showing high uterosacral suspension in a patient who has complete uterine procidentia.)

- Do not try to pass a ureteral stent if you do not see indigo carmine dye spill from the ureteral orifices; to do so can be difficult after repair of prolapse, even in the hands of a skilled urologist. It is best instead to:

- identify the offending suture

- cut it

- visualize the spill of dye-colored urine

- proceed with either replacing the cut suture or maintaining the suspension with other, remaining sutures.

In our experience, when we have also performed an anterior repair, the ureter is kinked in at least 50% of cases because of one of the sutures that was used to correct the cystocele.

2. Pack the bowel; expose the uterosacral ligaments

Next, pack the small bowel out of the cul-de-sac to allow easy access and visualization of the uppermost portions of the uterosacral ligament. This is best accomplished by passing large, moistened laparotomy sponges intraperitoneally and elevating them with a large retractor (e.g., Deaver, Breisky-Navrital, Sweetheart).

When the bowel is appropriately packed, the retractor lifts the intestinal contents out of the pelvis, usually allowing easy access to the proximal or uppermost portion of the uterosacral ligaments (see Video #3, which focuses on the anatomy of the uterosacral ligament).

When performing high uterosacral suspension, it is possible to pass sutures through the coccygeus muscle-sacrospinous ligament complex (arrow) because a segment of the uterosacral ligament inserts into that structure.

3. Palpate the ischial spines bilaterally

It’s important that you palpate the ischial spines. Often, the ureter can be palpated against the pelvic sidewall. If you palpate the ischial spines and continue to palpate medially and cephalad, you can usually palpate the coccygeus muscle-sacrospinous ligament complex transperitoneally because a portion of the uterosacral ligament inserts into the sacrospinous ligament.6

If sutures can be passed at this level, the result will (usually) be a vagina that is, at minimum, approximately 9 cm long.

FIGURE 3 Access to the sacrospinous ligament

The sacrospinous ligament can be palpated and exposed along any one of three approaches: anterior paravaginally (A), transperitoneally (B), and posterior pararectally (C).

4. Pass the sutures

We prefer to pass two or three sutures on each side, utilizing a long, straight needle holder. Because we eventually pass the sutures through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall, we’ve opted for a delayed absorbable suture—preferably, 0 Vicryl on a CT-2 needle.

A Breisky-Navrital retractor is utilized to retract the sigmoid colon in the opposite direction of the ligament in which the sutures are being passed. At times, attaching a light to a suction device or a retractor is also helpful to visualize this area.

Use an Allis clamp to elevate and apply traction on the distal uterosacral ligament; this facilitates palpation and visualization of the appropriate site for placement of the sutures. The exact area of suture passage is best identified by palpation.

(Note: In early descriptions of this procedure, permanent sutures were utilized; again, we use delayed absorbable sutures because all sutures are brought out through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall. Permanent suture in our approach would be unacceptable because the sutures are tied in the lumen of the vagina. In some other modifications of this procedure, sutures are passed through the muscular layer of the vagina to exclude epithelium; under those circumstances, permanent sutures can be utilized.)

Once the sutures are brought through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall—including the peritoneum, if possible—tag them individually. If the anterior segment is well-supported, close the vaginal incision with a continuous delayed absorbable suture.

Tie the suspension sutures, elevating the apex into the hollow of the sacrum.

If anterior colporrhaphy is needed, perform that repair. Close the anterior vaginal wall as well as the vaginal cuff before tying off the suspension sutures.

5. Ensure that the ureters are patent

After the sutures are tied, instruct the anesthesiologist to administer 5 cc of indigo carmine dye intravenously. Assuming no renal compromise, you should see dye in the bladder 5 to 10 minutes later. If the patient is elderly or if you want to expedite this step, furosemide, 5 to 10 mg, can be given by IV push.

Next, perform cystoscopy to ensure ureteral patency. You should observe a spill of dye-colored urine out of both ureteral orifices. If dye does not spill from either orifice after a reasonable wait (usually, 20 minutes), assume that the ureter on that side is obstructed.

FIGURE 4 Providing support for the posterior vaginal wall

A View of a posterior vaginal wall defect secondary to an enterocele and rectocele. B After entry into the enterocele sac, intraperitoneal suspension sutures are brought out through the full thickness of the vaginal wall at the level of the apex. C Tying these sutures after the vaginal incision is closed at the apex not only results in greater vaginal length but also contributes to overall support of the entire posterior vaginal wall.

6. Completely reconstruct the vagina

The remainder of steps required to complete the procedure usually involve posterior colporrhaphy and perineoplasty. We also reserve placement of a synthetic midurethral sling (if one is needed) until after the vault procedure is complete.

Refer to FIGURE 2 for a step-by step guide to how best to perform high uterosacral vaginal vault suspension.

Questions often asked about this procedure

What do I do if I can’t isolate an enterocele sac and enter it?

Perform a unilateral or bilateral sacrospinous ligament colpopexy.

Is it always possible to identify a usable uterosacral ligament in patients who have advanced prolapse?

We’ve found it extremely rare not to be able identify a usable and durable structure.

The trick to identifying the ligament is to pass an Allis clamp so that one end is positioned intraperitoneally, as high up as possible, and the other end is on the vaginal mucosa side. Elevating the clamp puts the ligament on tension. These clamps are usually placed between 4 and 5 o’clock on the left side and between 7 and 8 o’clock on the right side.

With appropriate traction, the ligament can usually be easily palpated.

If I don’t see indigo carmine dye spilling from one side during cystoscopy, what sequence of events should I undertake?

If the only sutures placed on that side were the uterosacral ligament sutures, cut them individually. If the ureter spills dye after a suture is cut, decide whether you think it is appropriate to replace that suture. Sometimes, unilateral suspension or a suspension with one remaining suture on the side where you cut a suture or two is sufficient.

If you do want to replace a cut suture, ureteral patency must be confirmed again after it is replaced.

No further management of the ureter is required—that is, it isn’t necessary to catheterize the ureter or perform postoperative imaging studies. If anterior colporrhaphy has also been performed, however, apply your highest index of suspicion to determine the source of the offending suture: the uterosacral suspension or the anterior repair.*

If the patient has severe hip or leg pain postoperatively, what should I suspect is wrong? How should I manage this complication?

The nerve to the levator ani runs within the coccygeus muscle. In a thin patient, in whom deep bites are taken, the nerve is often injured or trapped. Such trauma can cause hip pain that is fairly severe but that is almost always self-limiting and requires only nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication. Usually, this complication resolves within 2 weeks after surgery.

Significant postoperative pain that radiates down the back of the thigh or down the leg all the way to the foot is of greater concern because one of the sacral nerve segments has most likely been injured or stretched. Obtain a neurology consult; rarely, it becomes necessary to take the patient back to surgery to cut the offending suture.

*For detailed discussion of this subject, see the International Academy of Pelvic Surgery’s August 2010 “Case of the month” at www.academyofpelvicsurgery.com.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

- Pelvic anatomy of high intraperitoneal vaginal vault suspension

- Anatomy of the uterosacral ligament

- High uterosacral suspension (complete uterine procidentia)

- High uterosacral suspension (post-hysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse)

These videos were selected by Mickey Karram, MD, and Christine Vaccaro, DO, and are presented courtesy of the International Academy of Pelvic Surgery (IAPS).

This article, with accompanying video footage, is presented with the support of the International Academy of Pelvic Surgery.

The concept of utilizing the uterosacral ligaments to support the vaginal cuff and correct an enterocele is nothing new: As early as 1957, Milton McCall described what became known as the McCall culdoplasty, in which sutures incorporated the uterosacral ligaments into the posterior vaginal vault to obliterate the cul-de-sac and suspend or support the vaginal apex at the time of vaginal hysterectomy.1

Later, in the 1990s, Richardson promoted the concept that, in patients who have pelvic organ prolapse, the uterosacral ligaments do not become attenuated, instead, they break at specific points.

Shull and colleagues took this idea and described how utilizing uterosacral ligaments to support the vaginal cuff can be performed vaginally—by passing sutures bilaterally through the uterosacral ligaments near the level of the ischial spine.2

Since Shull described this procedure, numerous published studies have demonstrated outcomes similar to other vaginal suspension procedures, such as sacrospinous ligament suspension.3-5

Potential advantages of a high uterosacral vaginal vault suspension are that:

- it provides good apical support without significantly distorting the vaginal axis, making it applicable to all types of vaginal prolapse

- intraperitoneal passage of sutures can be a lot cleaner and simpler than passing sutures, or anchors, through retroperitoneal structures, such as the sacrospinous ligament (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1 Locating intraperitoneal sutures during uterosacral suspension

Cross-section of the pelvic floor shows where sutures are placed as part of McCall culdoplasty (1), traditional uterosacral suspension (2), and modified high uterosacral suspension (3). Note: High uterosacral suspension may involve passing the suture through the sacrospinous ligament–coccygeus (SSL-C) muscle complex (dashed oval) because a segment of the uterosacral ligament inserts into that structure.

A disadvantage of the procedure is that the uterosacral ligament may, at times, lie in close proximity to the ureter. Studies have shown that the ureter can become kinked when sutures in this procedure are passed too far laterally.2-5

High uterosacral suspension has been our operation of choice for 11 years for patients who have pelvic organ prolapse in which the peritoneum is accessible (see “How this procedure evolved in our hands”). In this article, we provide a step-by-step description of the procedure. Four accompanying videos that further illuminate those steps are noted in the text here at appropriate places.(For example, Video #1, immediately below, sets the stage for the step-by-step discussion by reviewing pertinent pelvic anatomy.)

- When we first performed high uterosacral vaginal vault suspension as described by Shull and colleagues,1 we mobilized vaginal muscularis off the epithelium and suspended the epithelium and muscularis separately, making sure that sutures were passed through the anterior and Posterior vaginal walls.

- Initially, we thought that a large cul-de-sac needed to be obliterated in the midline with internal McCall-type stitches that were separate and distinct from the uterosacral suspension sutures. We no longer do this routinely because we believe that the numerous sutures that are passed through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall, including the peritoneum, effectively obliterate the enterocele and keep down the incidence of recurrent enterocele and high rectocele.

- We have come to realize that sutures placed medial and cephalad to the ischial spine are often passed through a portion of the coccygeus muscle-sacrospinous ligament complex. At times, a small window can be made in the peritoneum that provides direct access to this complex (FIGURE 1; FIGURE 3).

References

1. Shull BL, Bachofen C, Coates KW, Kuehl TJ. A transvaginal approach to repair of apical and other associated sites of pelvic organ prolapse with uterosacral ligaments. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(6):1365-1374.

1. Enter the peritoneum

It’s our opinion that, even though extraperitoneal uterosacral suspension procedures have been described, the pertinent anatomic structures (again, see Video #1) are not easily identifiable unless suspension is undertaken intraperitoneally. Entering the peritoneum is, obviously, not a concern if the patient is undergoing vaginal hysterectomy. If the patient has post-hysterectomy prolapse, however, you must be able to isolate an enterocele and enter the peritoneum (follow FIGURE 2, beginning here and through subsequent steps of the procedure).

FIGURE 2 Step by step: High uterosacral vaginal vault suspension

A The most prominent portion of the prolapsed vaginal vault is grasped with two Allis clamps. B The vaginal wall is opened up and the enterocele sac is identified and entered. C The bowel is packed high into the pelvis using large laparotomy sponges. The retractor lifts the sponges out of the lower pelvis, thus completely exposing the cul-de-sac. When appropriate traction is placed downward on the uterosacral ligaments with an Allis clamp, the uterosacral ligaments are easily palpated bilaterally. D Delayed absorbable sutures have been passed through the uppermost portion of the uterosacral ligaments on each side, and have been individually tagged.

E Each end of the previously passed sutures is brought out through the posterior peritoneum and the posterior vaginal wall. (A free needle is used to pass both ends of these delayed absorbable sutures through the full thickness of the vaginal wall.) F Anterior colporrhaphy is begun by initiating dissection between the prolapsed bladder and the anterior vaginal wall. G Anterior colporrhaphy is complete. H The vagina has been appropriately trimmed and closed with interrupted or continuous delayed absorbable sutures. Delayed absorbable sutures that were previously brought out through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall are then tied; doing so elevates the prolapsed vaginal vault high up into the hollow of the sacrum.Once you have entered the peritoneum, the cul-de-sac must be relatively free of adhesive disease if you are to be able to continue with this procedure. (See “5 surgical pearls for high ureterosacral vaginal vault suspension”)

- Be prepared to convert to a sacrospinous fixation if you cannot enter the enterocele sac or if the posterior cul-de-sac is obliterated with adhesions

- Pass the sutures through durable tissue so that, when traction is placed on the sutures, there is minimal movement of peritoneum. Doing so might avoid kinking of the ureter.

- Pass the sutures through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall, including the peritoneum. Doing so not only suspends the apex but tremendously facilitates support for the posterior vaginal wall (FIGURE 4).

- When prolapse is very large, excise redundant portions of the upper part of the posterior vaginal wall and peritoneum—making sure, however, that you keep all layers together for performing the suspension. (See VIDEO #4, showing high uterosacral suspension in a patient who has complete uterine procidentia.)

- Do not try to pass a ureteral stent if you do not see indigo carmine dye spill from the ureteral orifices; to do so can be difficult after repair of prolapse, even in the hands of a skilled urologist. It is best instead to:

- identify the offending suture

- cut it

- visualize the spill of dye-colored urine

- proceed with either replacing the cut suture or maintaining the suspension with other, remaining sutures.

In our experience, when we have also performed an anterior repair, the ureter is kinked in at least 50% of cases because of one of the sutures that was used to correct the cystocele.

2. Pack the bowel; expose the uterosacral ligaments

Next, pack the small bowel out of the cul-de-sac to allow easy access and visualization of the uppermost portions of the uterosacral ligament. This is best accomplished by passing large, moistened laparotomy sponges intraperitoneally and elevating them with a large retractor (e.g., Deaver, Breisky-Navrital, Sweetheart).

When the bowel is appropriately packed, the retractor lifts the intestinal contents out of the pelvis, usually allowing easy access to the proximal or uppermost portion of the uterosacral ligaments (see Video #3, which focuses on the anatomy of the uterosacral ligament).

When performing high uterosacral suspension, it is possible to pass sutures through the coccygeus muscle-sacrospinous ligament complex (arrow) because a segment of the uterosacral ligament inserts into that structure.

3. Palpate the ischial spines bilaterally

It’s important that you palpate the ischial spines. Often, the ureter can be palpated against the pelvic sidewall. If you palpate the ischial spines and continue to palpate medially and cephalad, you can usually palpate the coccygeus muscle-sacrospinous ligament complex transperitoneally because a portion of the uterosacral ligament inserts into the sacrospinous ligament.6

If sutures can be passed at this level, the result will (usually) be a vagina that is, at minimum, approximately 9 cm long.

FIGURE 3 Access to the sacrospinous ligament

The sacrospinous ligament can be palpated and exposed along any one of three approaches: anterior paravaginally (A), transperitoneally (B), and posterior pararectally (C).

4. Pass the sutures

We prefer to pass two or three sutures on each side, utilizing a long, straight needle holder. Because we eventually pass the sutures through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall, we’ve opted for a delayed absorbable suture—preferably, 0 Vicryl on a CT-2 needle.

A Breisky-Navrital retractor is utilized to retract the sigmoid colon in the opposite direction of the ligament in which the sutures are being passed. At times, attaching a light to a suction device or a retractor is also helpful to visualize this area.

Use an Allis clamp to elevate and apply traction on the distal uterosacral ligament; this facilitates palpation and visualization of the appropriate site for placement of the sutures. The exact area of suture passage is best identified by palpation.