User login

Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome: A Consideration in Orthostatic Intolerance

CE/CME No: CR-1404

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Define postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS).

• List the presenting signs and symptoms of POTS.

• Differentiate POTS from other causes of orthostatic intolerance.

• Explain the common classifications of POTS.

• Enumerate the various referral and treatment options for the clinician to consider when a patient meets the criteria for POTS.

FACULTY

Molly Paulson is an Assistant Professor of Physician Assistant Studies in the College of Health Professions at Grand Valley State University, Grand Rapids, Michigan.

The author has no financial disclosures to report.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Article begins on next page >>

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome may not be the first disorder that clinicians consider when they encounter a patient with orthostatic intolerance, but ignoring this possibility during a differential diagnosis can mean patients continue to experience unexplained dizziness, fatigue, syncope, and a variety of other related signs and symptoms. Arriving at the correct diagnosis will allow you to help patients manage the condition and return to the lives and activities they previously enjoyed.

Clinicians should consider postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS; ICD-9 code 427.89) as part of the differential diagnosis of orthostatic intolerance (OI). Ignoring this possibility can delay proper diagnosis and treatment among patients who meet the criteria for POTS.

When patients present with symptoms of OI of unknown origin, it is important to consider a broad variety of conditions, including POTS, in the differential diagnosis. Clinicians should follow up with appropriate testing to determine if the criteria for any of these conditions are met. Once the cause of the OI is confirmed, appropriate initial care and referral will facilitate improved treatment for the patient.

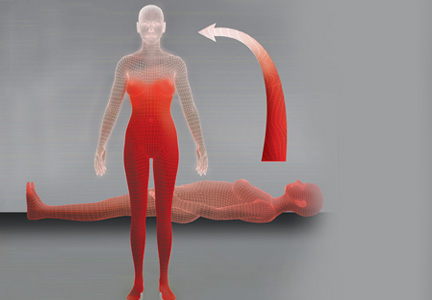

A recent consensus statement defines POTS as an increase in heart rate of at least 30 beats/min or a heart rate of at least 120 beats/min upon standing from a supine position—or in response to a tilt-table test—that is sustained for 10 minutes without evidence of orthostatic hypotension.1,2 Although POTS can be seen in men, most cases occur in women of childbearing age, with a female-to-male ratio of 4:1 to 5:1.2 Patients most commonly present with symptoms similar to orthostatic hypotension.3 Typical symptoms include dizziness, near-syncope or syncope, fatigue, headache, visual changes, lightheadedness, weakness, and abdominal discomfort.4,5 Presenting symptoms also overlap with other, more prevalent disorders, leading to frequent misdiagnosis.

Examples of common initial misdiagnoses for patients with POTS include anxiety, chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, menopause, orthostatic hypotension, unstable angina, and hyperadrenergic states.1,6 Inappropriate or delayed treatment of POTS can lead to significant daily functional impairment similar to that associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or congestive heart failure.4,6,7

UNDERSTANDING ORTHOSTATIC INTOLERANCE

To better understand POTS, clinicians should have a clear understanding of OI. According to Stewart,8 OI is defined by symptoms of impending near-syncope or syncope, including dizziness, headache, fatigue, exercise intolerance, abdominal distress, or a sensation of feeling “hot” accompanied by sweating. These symptoms occur when a patient assumes an upright position and are relieved when the person returns to a supine position.8

Normally, when a person stands, gravitational forces cause a redistribution of 300 to 800 mL of blood in both the splanchnic and lower extremity circulation. This decreases systolic blood pressure and slows cardiac filling. The resultant decreased cardiac output stimulates increased sympathetic tone via the baroreceptors and other mechanisms to restore arterial blood pressure.1,9 In OI, this compensatory mechanism is compromised, and the patient experiences the symptoms of impending near-syncope or syncope, as discussed previously.

A broad array of medical conditions with multiple etiologies meet the criteria for OI.10 Although a comprehensive list of these conditions is beyond the scope of this article, it is essential for the clinician to look for primary and secondary causes of orthostasis by gathering a comprehensive history, followed by an extensive physical exam directed by the history. The patient should be asked about a history of allergies or autoimmune disease, cancers, eating disorders, infections, adverse effects of medication, and signs or symptoms of chronic sympathetic stimulation. It is also important to review the current medication list carefully and evaluate the patient for dysfunction of the cardiac, endocrine, renal, and nervous systems and for psychiatric disorders. A short list of conditions that may present with OI include anemia, anorexia, autoimmune disease, cancers, cardiac disease, diabetes, infections, paraneoplastic syndromes, vascular disease, and volume depletion.2,8,11,12

Hypotension is absent in POTS, but it otherwise also fits the profile of OI. POTS can also present with a host of other nonspecific, nonorthostatic symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, fatigue, migraine headaches, and chest pain.10 This unusual presentation can confound the clinician and complicate the medical picture, making a clear diagnosis difficult.

On the next page: History, epidemiology, and etiology >>

HISTORY, EPIDEMIOLOGY, AND ETIOLOGY

POTS was first recognized and described during the Civil War as irritable heart syndrome or soldier’s heart due to the frequency of the condition in combat soldiers. As more was published about the condition, the list of names grew to include Da Costa syndrome, anxiety neurosis, chronic orthostatic intolerance, effort syndrome, idiopathic hypovolemia, mitral valve prolapse syndrome, orthostatic tachycardia, positional tachycardia syndrome, and finally postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.5,12 Although initially described in men in the military, the condition is more frequently seen in young women from puberty to age 50. Some researchers have proposed that POTS is much more common than recent studies report; they suggest that the condition is underreported both because of the nonspecific nature of the symptoms and because it is not often included in the differential of OI.5

Although some researchers disagree,7,12 most of the literature supports multiple etiologies of POTS.1,2,13 Researchers have divided the syndrome into primary and secondary causes. They have further separated primary POTS into two broad categories based on neuropathic or hyperadrenergic pathology. In both subgroups, POTS is exacerbated by dependent vasodilatation and central hypovolemia.11

In the more common neuropathic POTS, a precipitating factor such as an infection, trauma, pregnancy, or surgery precedes the sudden onset of symptoms. In the majority of patients with neuropathic POTS, high normal to elevated serum norepinephrine (NE) levels are detected, as compared to “normal” controls,5 but known antibodies are not detected. However, in approximately 10% to 15% of patients with a reported antecedent infection, acetylcholine receptor antibodies have been detected.2,14 This form is described in the literature as immune-mediated POTS.2,11,14,15

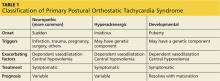

The less common primary hyperadrenergic POTS presents more insidiously and may have a genetic component. As documented in some families, a point mutation in the NE transporter protein has been shown to slow clearance of NE from the synaptic cleft in the central nervous system. This leads to excessive central sympathetic stimulation of the periphery.12,13,16 Developmental POTS, which presents at puberty with lower extremity neuropathy, is another form of primary POTS and resolves with maturity (see Table 1).6

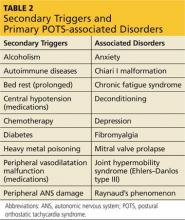

Secondary POTS can be triggered by several known conditions including alcoholism.12,16 Any disease or insult that damages the peripheral autonomic system may precipitate POTS. Examples include autoimmune diseases, diabetes, chemotherapy, and heavy metal poisoning.13 Genetic disorders have also been associated with or can contribute to secondary POTS. Joint hypermobility syndrome (JHS), also known as Ehlers-Danlos type III, is a genetic disorder characterized by defects in the structure of connective tissue.16 In JHS, the connective tissue in blood vessels is more elastic, leading to greater lower extremity pooling and decreased vasoconstrictive response to sympathetic stimulation on standing. The literature also notes that prolonged bed rest and any medications that contribute to central hypotension or interfere with compensatory peripheral vasoconstriction may precipitate POTS (see Table 2).

On the next page: Clinical presentation and differential diagnosis >>

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Patients with POTS frequently present with a sudden onset of OI related to activity or changes from recumbency to standing. They often identify an illness, accident, or surgery preceding the onset of symptoms. Other clinical manifestations of POTS include acrocyanosis, fatigue, headaches, constitutional hypotension, sleep disturbances, and gastrointestinal symptoms.12,13 Frequently, patients come to the emergency department with chest pain, indigestion, fatigue, and heart palpitations,14,15 concerned that they are having a heart attack. Since symptoms resolve with recumbency and no clinical markers for acute coronary syndromes are found, no further workup is obtained, and patients are sent home with the recommendation to see their primary care provider.

The symptoms of POTS are complex, nonspecific, and debilitating. Fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and tachycardia when standing make activities of daily living such as work, home maintenance, and child care challenging. The unpredictable symptoms make life frustrating for patients and their families. The presenting symptoms, the normal results for routine blood tests, and the lack of cardiac abnormalities often lead providers to a diagnosis of anxiety or panic disorder.13 Since the symptoms of POTS are somewhat mitigated by treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors,16 patients and providers often will accept the diagnosis and not investigate the symptoms further.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis of POTS begins with any condition that causes tachycardia or OI. Clinicians should also consider and rule out cardiac abnormalities such as inappropriate tachycardia, supraventricular tachycardia, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, and other cardiac dysrhythmias. Other diagnoses that should be considered are endocrine abnormalities, including hyperthyroidism, hypoadrenalism, and pheochromocytoma; drug adverse effects and interactions, necessitating scrupulous evaluation of the patient’s medication list; changes in volume status; and kidney disease.1 Causes of autonomic dysfunction in both the peripheral and central nervous system, including Chiari I malformation, need to be scrutinized.17

Many conditions within the differential diagnosis can occur concomitantly with POTS and need to be treated, even as further evaluation continues. An extensive history and review of systems is essential to obtain a complete list of symptoms and lead the clinician toward an appropriate physical exam and necessary adjunct testing.

ASSOCIATED DISORDERS

Of the many conditions associated with POTS, JHS is the most common genetic disorder. In this disorder, a genetic mutation produces changes in the composition of the collagen, resulting in enhanced flexibility and compliance of any tissue with collagen in it.16 Mitral valve prolapse is also associated with JHS and POTS.12

POTS is present in 40% of patients diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome, as well as in a high percentage of those with fibromyalgia.6,7 The many related and comorbid ailments preclude a straightforward diagnosis. Testing for more common illnesses, as well as consideration of associated disorders, is essential in the care of the patient with POTS.

On the next page: Testing and referral >>

TESTING AND REFERRAL

An appropriate workup for POTS includes a complete and thorough history plus a comprehensive physical examination. This includes reviewing the patient’s medication list for any medications or combinations of medications that cause cerebral hypoperfusion, volume depletion, tachycardia, or peripheral vasodilation.2 It is essential to explore the family history for genetic disorders12 and to take a detailed social history, including lifestyle habits that may reproduce the symptoms of POTS.

The definitive diagnosis of POTS is made with a tilt-table test. Obtaining in-office orthostatic vitals can substantially increase the index of suspicion for the syndrome. The procedure used to obtain orthostatic vitals varies by institution. However, every protocol includes a period of rest in a supine position, after which the patient is asked to stand and the blood pressure and pulse are measured after a specified number of minutes. If the patient becomes symptomatic on standing, the blood pressure remains unchanged, and the pulse is elevated to at least 30 beats/min from the supine pulse or greater than 20 beats/min after 10 minutes, a diagnosis of POTS must be considered. Unless a more common cause of the tachycardia is found and treated to resolution, tilt-table testing should be ordered to evaluate these patients for POTS.

If POTS is suspected once the history and physical are completed, the patient should be referred to cardiology or neurology for tilt-table testing to confirm the diagnosis. Laboratory testing should include, but not be limited to, a complete blood count with differential, a comprehensive metabolic panel, Westergren sedimentation rate, and thyroid testing. Adrenal testing,11 a search for vitamin deficiencies, autoimmune diseases, and infective causes (eg, Lyme disease and cytomegalovirus), and urinalysis may also be appropriate based on the patient history and presentation.14

Broad ancillary testing and referral may be needed in patients with POTS. According to Giesken,14 an ECG, echocardiogram, cardiac event monitoring, and an evaluation by a cardiologist are essential. Pasupuleti and Vedre17 recommend referral to a neurologist for evaluation for peripheral and central lesions with electromyography and MRI. Depending on the practice, tilt-table testing may be available through either specialty and may guide the work-up. Referrals to an endocrinologist, a rheumatologist, and a nephrologist to evaluate hyperadrenergic states, autoimmune dysfunction, and kidney disease should be considered as well.14,16 Referrals and additional tests may be necessary, even if secondary causes of POTS are not identified. These tests, although extensive and expensive, may help determine the best and most appropriate treatment options to control the patient’s symptoms and restore quality of life.

On the next page: Treatment >>

TREATMENT

Once the diagnosis of POTS has been confirmed, symptomatic treatment tailored to the patient’s symptoms can begin. Secondary POTS often resolves with effective treatment of the causative disease. One of the most important aspects of effective treatment of primary POTS is to educate patients on how to control their symptoms. Patients must understand that primary POTS cannot be “cured” by current medical therapies. They need to be aware of the erratic symptoms and be proactive in preventing them from occurring. Both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatments are helpful, but a multidisciplinary approach appears to be most efficacious for optimizing return to baseline function in patients.14,16

To prevent exacerbations, patients should avoid situations that precipitate symptoms, such as prolonged standing, inadequate water intake, and cold and hot environments. In addition, providers should advise patients to optimize their fluid status. The literature recommends adding up to 20 g of sodium to the diet daily, and patients should be instructed to drink a minimum of two liters of water during the course of the day.13,16 This includes drinking at least eight ounces of water before rising from a recumbent position. Patients should also be instructed to sleep on an incline7 and to gradually transition to standing when getting up in the morning or after a nap.12 Clinicians should also recommend waist-high graded elastic hose, an abdominal girdle, or both, to assist venous return from the lower extremities and to avoid splanchnic pooling.13

Exercise training has been shown to be effective in treating symptoms of POTS. A recent study published by Fu et al7 demonstrated improved oxygen uptake, increased blood volume, increased cardiac output, and increased left ventricular mass with graduated exercise over a period of several months. The study group demonstrated a lower average resting heart rate and improved exercise tolerance on completion of the trial. In fact, the study reported that after training, more than half of the study patients (10 of 19) no longer fulfilled the criteria for POTS, and all patients who underwent training experienced significant improvements in quality of life.7

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPIES

Pharmacologic therapies for POTS abound. Treatments must be tailored to each patient’s needs based on the suspected or proven etiology of POTS, as well as any associated or comorbid conditions. Fludrocortisone will decrease salt loss and increase plasma volume in patients with hypovolemia. Midodrine improves vasoconstriction in the extremities. Beta-blockers slow the heart rate and prevent vasodilation. Clonidine can lower the blood pressure and decrease the heart rate by preventing central sympathetic stimulation.12 Alternatively, or in conjunction with the other treatment modalities, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may improve sleep, slow the heart rate,16 improve mood, and alleviate gastrointestinal symptoms. As with all medications, clinicians must discuss the risks, benefits, adverse effects, alternatives, and potential interactions with the patient prior to starting medications.

On the next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

POTS most often presents as OI, which is why investigation of OI should include consideration of POTS as part of the differential diagnosis. Untreated, the symptoms of POTS can prevent patients from participating in normal life activities, including recreation, school, and work, leading to dysfunction, disability, and depression.7 A prompt diagnosis, confirmed by tilt-table testing, will expedite appropriate referral, ancillary testing, and treatment. Optimal therapy has not been established, yet individualized patient education, along with the development of a personalized program to alleviate symptoms, will provide patients with a sense of hope and control over the syndrome. This approach will enable patients and their families to manage the condition and optimize their quality of life.

The author would like to thank Michael Whitehead, DHSc, MPAS, PA-C, DFAAPA, an adjunct professor at A. T. Still University in Mesa, Arizona, for his input on this article.

1. Freeman R, Wieling W, Axelrod FB, et al. Consensus statement on the definition of orthostatic hypotension, neurally mediated syncope and the postural tachycardia syndrome.Clin Auton Res. 2011;21:69-72.

2. Johnson JN, Mack KJ, Kuntz NL, et al. Postural orthostatic tachcardia syndrome: a clinical review. Pediatr Neurol. 2009;42:77-85.

3. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institiute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Postural Tachycardia Syndrome Information Page. 2011. www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/postural_tachycardia_syndrome/postural_tachycardia_syndrome.htm. Accessed March 24, 2014.

4. Agarwal AK, Garg R, Ritch A, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:478-480.

5. Jacob G, Costa F, Shannon JR, et al. The neuropathic postural tachycardia syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1008-1014.

6. Staud R. Autonomic dysfunction in fibromyalgia syndrome: postural orthostatic tachycardia. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2008;10:463-466.

7. Fu Q, VanGundy TB, Galbreath MM, et al. Cardiac origins of the postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:

2858-2868.

8. Stewart JM. Postural tachycardia syndrome and reflex syncope: similarities and differences. J Pediatr. 2009;154:481-485.

9. Lanier JB, Mote MB, Clay EC. Evaluation and management of orthostatic hypotension. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:527-536.

10. Ojha A, McNeeley K, Heller E, et al. Orthostatic syndromes differ in syncope frequency. Am J Med. 2010;123:245-249.

11. Graham U, Ritchie KM. Reminder of important clinical lesson: postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009: bcr10.2008.1132. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3029273. Accessed March 24, 2014.

12. Mathias CJ, Low DA, Iodice V, et al. Postural tachycardia syndrome—current experience and concepts. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8:22-34.

13. Thanavaro JL, Thanavaro KL. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. Heart Lung. 2011;40:554-560.

14. Giesken B, Collins M. A 46-year-old woman with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. JAAPA. 2013;26:30-34.

15. Low PA, Sandroni P, Joyner M, et al. Postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS). J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:352-358.

16. Busmer L. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Primary Health Care. 2011;21:16-20.

17. Pasupuleti DV, Vedre A. Postural orthostatic tachycardia warrants investigation of Chiari I malformation as a possible cause. Cardiology. 2005;103:55-56.

CE/CME No: CR-1404

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Define postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS).

• List the presenting signs and symptoms of POTS.

• Differentiate POTS from other causes of orthostatic intolerance.

• Explain the common classifications of POTS.

• Enumerate the various referral and treatment options for the clinician to consider when a patient meets the criteria for POTS.

FACULTY

Molly Paulson is an Assistant Professor of Physician Assistant Studies in the College of Health Professions at Grand Valley State University, Grand Rapids, Michigan.

The author has no financial disclosures to report.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Article begins on next page >>

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome may not be the first disorder that clinicians consider when they encounter a patient with orthostatic intolerance, but ignoring this possibility during a differential diagnosis can mean patients continue to experience unexplained dizziness, fatigue, syncope, and a variety of other related signs and symptoms. Arriving at the correct diagnosis will allow you to help patients manage the condition and return to the lives and activities they previously enjoyed.

Clinicians should consider postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS; ICD-9 code 427.89) as part of the differential diagnosis of orthostatic intolerance (OI). Ignoring this possibility can delay proper diagnosis and treatment among patients who meet the criteria for POTS.

When patients present with symptoms of OI of unknown origin, it is important to consider a broad variety of conditions, including POTS, in the differential diagnosis. Clinicians should follow up with appropriate testing to determine if the criteria for any of these conditions are met. Once the cause of the OI is confirmed, appropriate initial care and referral will facilitate improved treatment for the patient.

A recent consensus statement defines POTS as an increase in heart rate of at least 30 beats/min or a heart rate of at least 120 beats/min upon standing from a supine position—or in response to a tilt-table test—that is sustained for 10 minutes without evidence of orthostatic hypotension.1,2 Although POTS can be seen in men, most cases occur in women of childbearing age, with a female-to-male ratio of 4:1 to 5:1.2 Patients most commonly present with symptoms similar to orthostatic hypotension.3 Typical symptoms include dizziness, near-syncope or syncope, fatigue, headache, visual changes, lightheadedness, weakness, and abdominal discomfort.4,5 Presenting symptoms also overlap with other, more prevalent disorders, leading to frequent misdiagnosis.

Examples of common initial misdiagnoses for patients with POTS include anxiety, chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, menopause, orthostatic hypotension, unstable angina, and hyperadrenergic states.1,6 Inappropriate or delayed treatment of POTS can lead to significant daily functional impairment similar to that associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or congestive heart failure.4,6,7

UNDERSTANDING ORTHOSTATIC INTOLERANCE

To better understand POTS, clinicians should have a clear understanding of OI. According to Stewart,8 OI is defined by symptoms of impending near-syncope or syncope, including dizziness, headache, fatigue, exercise intolerance, abdominal distress, or a sensation of feeling “hot” accompanied by sweating. These symptoms occur when a patient assumes an upright position and are relieved when the person returns to a supine position.8

Normally, when a person stands, gravitational forces cause a redistribution of 300 to 800 mL of blood in both the splanchnic and lower extremity circulation. This decreases systolic blood pressure and slows cardiac filling. The resultant decreased cardiac output stimulates increased sympathetic tone via the baroreceptors and other mechanisms to restore arterial blood pressure.1,9 In OI, this compensatory mechanism is compromised, and the patient experiences the symptoms of impending near-syncope or syncope, as discussed previously.

A broad array of medical conditions with multiple etiologies meet the criteria for OI.10 Although a comprehensive list of these conditions is beyond the scope of this article, it is essential for the clinician to look for primary and secondary causes of orthostasis by gathering a comprehensive history, followed by an extensive physical exam directed by the history. The patient should be asked about a history of allergies or autoimmune disease, cancers, eating disorders, infections, adverse effects of medication, and signs or symptoms of chronic sympathetic stimulation. It is also important to review the current medication list carefully and evaluate the patient for dysfunction of the cardiac, endocrine, renal, and nervous systems and for psychiatric disorders. A short list of conditions that may present with OI include anemia, anorexia, autoimmune disease, cancers, cardiac disease, diabetes, infections, paraneoplastic syndromes, vascular disease, and volume depletion.2,8,11,12

Hypotension is absent in POTS, but it otherwise also fits the profile of OI. POTS can also present with a host of other nonspecific, nonorthostatic symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, fatigue, migraine headaches, and chest pain.10 This unusual presentation can confound the clinician and complicate the medical picture, making a clear diagnosis difficult.

On the next page: History, epidemiology, and etiology >>

HISTORY, EPIDEMIOLOGY, AND ETIOLOGY

POTS was first recognized and described during the Civil War as irritable heart syndrome or soldier’s heart due to the frequency of the condition in combat soldiers. As more was published about the condition, the list of names grew to include Da Costa syndrome, anxiety neurosis, chronic orthostatic intolerance, effort syndrome, idiopathic hypovolemia, mitral valve prolapse syndrome, orthostatic tachycardia, positional tachycardia syndrome, and finally postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.5,12 Although initially described in men in the military, the condition is more frequently seen in young women from puberty to age 50. Some researchers have proposed that POTS is much more common than recent studies report; they suggest that the condition is underreported both because of the nonspecific nature of the symptoms and because it is not often included in the differential of OI.5

Although some researchers disagree,7,12 most of the literature supports multiple etiologies of POTS.1,2,13 Researchers have divided the syndrome into primary and secondary causes. They have further separated primary POTS into two broad categories based on neuropathic or hyperadrenergic pathology. In both subgroups, POTS is exacerbated by dependent vasodilatation and central hypovolemia.11

In the more common neuropathic POTS, a precipitating factor such as an infection, trauma, pregnancy, or surgery precedes the sudden onset of symptoms. In the majority of patients with neuropathic POTS, high normal to elevated serum norepinephrine (NE) levels are detected, as compared to “normal” controls,5 but known antibodies are not detected. However, in approximately 10% to 15% of patients with a reported antecedent infection, acetylcholine receptor antibodies have been detected.2,14 This form is described in the literature as immune-mediated POTS.2,11,14,15

The less common primary hyperadrenergic POTS presents more insidiously and may have a genetic component. As documented in some families, a point mutation in the NE transporter protein has been shown to slow clearance of NE from the synaptic cleft in the central nervous system. This leads to excessive central sympathetic stimulation of the periphery.12,13,16 Developmental POTS, which presents at puberty with lower extremity neuropathy, is another form of primary POTS and resolves with maturity (see Table 1).6

Secondary POTS can be triggered by several known conditions including alcoholism.12,16 Any disease or insult that damages the peripheral autonomic system may precipitate POTS. Examples include autoimmune diseases, diabetes, chemotherapy, and heavy metal poisoning.13 Genetic disorders have also been associated with or can contribute to secondary POTS. Joint hypermobility syndrome (JHS), also known as Ehlers-Danlos type III, is a genetic disorder characterized by defects in the structure of connective tissue.16 In JHS, the connective tissue in blood vessels is more elastic, leading to greater lower extremity pooling and decreased vasoconstrictive response to sympathetic stimulation on standing. The literature also notes that prolonged bed rest and any medications that contribute to central hypotension or interfere with compensatory peripheral vasoconstriction may precipitate POTS (see Table 2).

On the next page: Clinical presentation and differential diagnosis >>

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Patients with POTS frequently present with a sudden onset of OI related to activity or changes from recumbency to standing. They often identify an illness, accident, or surgery preceding the onset of symptoms. Other clinical manifestations of POTS include acrocyanosis, fatigue, headaches, constitutional hypotension, sleep disturbances, and gastrointestinal symptoms.12,13 Frequently, patients come to the emergency department with chest pain, indigestion, fatigue, and heart palpitations,14,15 concerned that they are having a heart attack. Since symptoms resolve with recumbency and no clinical markers for acute coronary syndromes are found, no further workup is obtained, and patients are sent home with the recommendation to see their primary care provider.

The symptoms of POTS are complex, nonspecific, and debilitating. Fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and tachycardia when standing make activities of daily living such as work, home maintenance, and child care challenging. The unpredictable symptoms make life frustrating for patients and their families. The presenting symptoms, the normal results for routine blood tests, and the lack of cardiac abnormalities often lead providers to a diagnosis of anxiety or panic disorder.13 Since the symptoms of POTS are somewhat mitigated by treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors,16 patients and providers often will accept the diagnosis and not investigate the symptoms further.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis of POTS begins with any condition that causes tachycardia or OI. Clinicians should also consider and rule out cardiac abnormalities such as inappropriate tachycardia, supraventricular tachycardia, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, and other cardiac dysrhythmias. Other diagnoses that should be considered are endocrine abnormalities, including hyperthyroidism, hypoadrenalism, and pheochromocytoma; drug adverse effects and interactions, necessitating scrupulous evaluation of the patient’s medication list; changes in volume status; and kidney disease.1 Causes of autonomic dysfunction in both the peripheral and central nervous system, including Chiari I malformation, need to be scrutinized.17

Many conditions within the differential diagnosis can occur concomitantly with POTS and need to be treated, even as further evaluation continues. An extensive history and review of systems is essential to obtain a complete list of symptoms and lead the clinician toward an appropriate physical exam and necessary adjunct testing.

ASSOCIATED DISORDERS

Of the many conditions associated with POTS, JHS is the most common genetic disorder. In this disorder, a genetic mutation produces changes in the composition of the collagen, resulting in enhanced flexibility and compliance of any tissue with collagen in it.16 Mitral valve prolapse is also associated with JHS and POTS.12

POTS is present in 40% of patients diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome, as well as in a high percentage of those with fibromyalgia.6,7 The many related and comorbid ailments preclude a straightforward diagnosis. Testing for more common illnesses, as well as consideration of associated disorders, is essential in the care of the patient with POTS.

On the next page: Testing and referral >>

TESTING AND REFERRAL

An appropriate workup for POTS includes a complete and thorough history plus a comprehensive physical examination. This includes reviewing the patient’s medication list for any medications or combinations of medications that cause cerebral hypoperfusion, volume depletion, tachycardia, or peripheral vasodilation.2 It is essential to explore the family history for genetic disorders12 and to take a detailed social history, including lifestyle habits that may reproduce the symptoms of POTS.

The definitive diagnosis of POTS is made with a tilt-table test. Obtaining in-office orthostatic vitals can substantially increase the index of suspicion for the syndrome. The procedure used to obtain orthostatic vitals varies by institution. However, every protocol includes a period of rest in a supine position, after which the patient is asked to stand and the blood pressure and pulse are measured after a specified number of minutes. If the patient becomes symptomatic on standing, the blood pressure remains unchanged, and the pulse is elevated to at least 30 beats/min from the supine pulse or greater than 20 beats/min after 10 minutes, a diagnosis of POTS must be considered. Unless a more common cause of the tachycardia is found and treated to resolution, tilt-table testing should be ordered to evaluate these patients for POTS.

If POTS is suspected once the history and physical are completed, the patient should be referred to cardiology or neurology for tilt-table testing to confirm the diagnosis. Laboratory testing should include, but not be limited to, a complete blood count with differential, a comprehensive metabolic panel, Westergren sedimentation rate, and thyroid testing. Adrenal testing,11 a search for vitamin deficiencies, autoimmune diseases, and infective causes (eg, Lyme disease and cytomegalovirus), and urinalysis may also be appropriate based on the patient history and presentation.14

Broad ancillary testing and referral may be needed in patients with POTS. According to Giesken,14 an ECG, echocardiogram, cardiac event monitoring, and an evaluation by a cardiologist are essential. Pasupuleti and Vedre17 recommend referral to a neurologist for evaluation for peripheral and central lesions with electromyography and MRI. Depending on the practice, tilt-table testing may be available through either specialty and may guide the work-up. Referrals to an endocrinologist, a rheumatologist, and a nephrologist to evaluate hyperadrenergic states, autoimmune dysfunction, and kidney disease should be considered as well.14,16 Referrals and additional tests may be necessary, even if secondary causes of POTS are not identified. These tests, although extensive and expensive, may help determine the best and most appropriate treatment options to control the patient’s symptoms and restore quality of life.

On the next page: Treatment >>

TREATMENT

Once the diagnosis of POTS has been confirmed, symptomatic treatment tailored to the patient’s symptoms can begin. Secondary POTS often resolves with effective treatment of the causative disease. One of the most important aspects of effective treatment of primary POTS is to educate patients on how to control their symptoms. Patients must understand that primary POTS cannot be “cured” by current medical therapies. They need to be aware of the erratic symptoms and be proactive in preventing them from occurring. Both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatments are helpful, but a multidisciplinary approach appears to be most efficacious for optimizing return to baseline function in patients.14,16

To prevent exacerbations, patients should avoid situations that precipitate symptoms, such as prolonged standing, inadequate water intake, and cold and hot environments. In addition, providers should advise patients to optimize their fluid status. The literature recommends adding up to 20 g of sodium to the diet daily, and patients should be instructed to drink a minimum of two liters of water during the course of the day.13,16 This includes drinking at least eight ounces of water before rising from a recumbent position. Patients should also be instructed to sleep on an incline7 and to gradually transition to standing when getting up in the morning or after a nap.12 Clinicians should also recommend waist-high graded elastic hose, an abdominal girdle, or both, to assist venous return from the lower extremities and to avoid splanchnic pooling.13

Exercise training has been shown to be effective in treating symptoms of POTS. A recent study published by Fu et al7 demonstrated improved oxygen uptake, increased blood volume, increased cardiac output, and increased left ventricular mass with graduated exercise over a period of several months. The study group demonstrated a lower average resting heart rate and improved exercise tolerance on completion of the trial. In fact, the study reported that after training, more than half of the study patients (10 of 19) no longer fulfilled the criteria for POTS, and all patients who underwent training experienced significant improvements in quality of life.7

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPIES

Pharmacologic therapies for POTS abound. Treatments must be tailored to each patient’s needs based on the suspected or proven etiology of POTS, as well as any associated or comorbid conditions. Fludrocortisone will decrease salt loss and increase plasma volume in patients with hypovolemia. Midodrine improves vasoconstriction in the extremities. Beta-blockers slow the heart rate and prevent vasodilation. Clonidine can lower the blood pressure and decrease the heart rate by preventing central sympathetic stimulation.12 Alternatively, or in conjunction with the other treatment modalities, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may improve sleep, slow the heart rate,16 improve mood, and alleviate gastrointestinal symptoms. As with all medications, clinicians must discuss the risks, benefits, adverse effects, alternatives, and potential interactions with the patient prior to starting medications.

On the next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

POTS most often presents as OI, which is why investigation of OI should include consideration of POTS as part of the differential diagnosis. Untreated, the symptoms of POTS can prevent patients from participating in normal life activities, including recreation, school, and work, leading to dysfunction, disability, and depression.7 A prompt diagnosis, confirmed by tilt-table testing, will expedite appropriate referral, ancillary testing, and treatment. Optimal therapy has not been established, yet individualized patient education, along with the development of a personalized program to alleviate symptoms, will provide patients with a sense of hope and control over the syndrome. This approach will enable patients and their families to manage the condition and optimize their quality of life.

The author would like to thank Michael Whitehead, DHSc, MPAS, PA-C, DFAAPA, an adjunct professor at A. T. Still University in Mesa, Arizona, for his input on this article.

CE/CME No: CR-1404

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Define postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS).

• List the presenting signs and symptoms of POTS.

• Differentiate POTS from other causes of orthostatic intolerance.

• Explain the common classifications of POTS.

• Enumerate the various referral and treatment options for the clinician to consider when a patient meets the criteria for POTS.

FACULTY

Molly Paulson is an Assistant Professor of Physician Assistant Studies in the College of Health Professions at Grand Valley State University, Grand Rapids, Michigan.

The author has no financial disclosures to report.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Article begins on next page >>

Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome may not be the first disorder that clinicians consider when they encounter a patient with orthostatic intolerance, but ignoring this possibility during a differential diagnosis can mean patients continue to experience unexplained dizziness, fatigue, syncope, and a variety of other related signs and symptoms. Arriving at the correct diagnosis will allow you to help patients manage the condition and return to the lives and activities they previously enjoyed.

Clinicians should consider postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS; ICD-9 code 427.89) as part of the differential diagnosis of orthostatic intolerance (OI). Ignoring this possibility can delay proper diagnosis and treatment among patients who meet the criteria for POTS.

When patients present with symptoms of OI of unknown origin, it is important to consider a broad variety of conditions, including POTS, in the differential diagnosis. Clinicians should follow up with appropriate testing to determine if the criteria for any of these conditions are met. Once the cause of the OI is confirmed, appropriate initial care and referral will facilitate improved treatment for the patient.

A recent consensus statement defines POTS as an increase in heart rate of at least 30 beats/min or a heart rate of at least 120 beats/min upon standing from a supine position—or in response to a tilt-table test—that is sustained for 10 minutes without evidence of orthostatic hypotension.1,2 Although POTS can be seen in men, most cases occur in women of childbearing age, with a female-to-male ratio of 4:1 to 5:1.2 Patients most commonly present with symptoms similar to orthostatic hypotension.3 Typical symptoms include dizziness, near-syncope or syncope, fatigue, headache, visual changes, lightheadedness, weakness, and abdominal discomfort.4,5 Presenting symptoms also overlap with other, more prevalent disorders, leading to frequent misdiagnosis.

Examples of common initial misdiagnoses for patients with POTS include anxiety, chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, menopause, orthostatic hypotension, unstable angina, and hyperadrenergic states.1,6 Inappropriate or delayed treatment of POTS can lead to significant daily functional impairment similar to that associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or congestive heart failure.4,6,7

UNDERSTANDING ORTHOSTATIC INTOLERANCE

To better understand POTS, clinicians should have a clear understanding of OI. According to Stewart,8 OI is defined by symptoms of impending near-syncope or syncope, including dizziness, headache, fatigue, exercise intolerance, abdominal distress, or a sensation of feeling “hot” accompanied by sweating. These symptoms occur when a patient assumes an upright position and are relieved when the person returns to a supine position.8

Normally, when a person stands, gravitational forces cause a redistribution of 300 to 800 mL of blood in both the splanchnic and lower extremity circulation. This decreases systolic blood pressure and slows cardiac filling. The resultant decreased cardiac output stimulates increased sympathetic tone via the baroreceptors and other mechanisms to restore arterial blood pressure.1,9 In OI, this compensatory mechanism is compromised, and the patient experiences the symptoms of impending near-syncope or syncope, as discussed previously.

A broad array of medical conditions with multiple etiologies meet the criteria for OI.10 Although a comprehensive list of these conditions is beyond the scope of this article, it is essential for the clinician to look for primary and secondary causes of orthostasis by gathering a comprehensive history, followed by an extensive physical exam directed by the history. The patient should be asked about a history of allergies or autoimmune disease, cancers, eating disorders, infections, adverse effects of medication, and signs or symptoms of chronic sympathetic stimulation. It is also important to review the current medication list carefully and evaluate the patient for dysfunction of the cardiac, endocrine, renal, and nervous systems and for psychiatric disorders. A short list of conditions that may present with OI include anemia, anorexia, autoimmune disease, cancers, cardiac disease, diabetes, infections, paraneoplastic syndromes, vascular disease, and volume depletion.2,8,11,12

Hypotension is absent in POTS, but it otherwise also fits the profile of OI. POTS can also present with a host of other nonspecific, nonorthostatic symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, fatigue, migraine headaches, and chest pain.10 This unusual presentation can confound the clinician and complicate the medical picture, making a clear diagnosis difficult.

On the next page: History, epidemiology, and etiology >>

HISTORY, EPIDEMIOLOGY, AND ETIOLOGY

POTS was first recognized and described during the Civil War as irritable heart syndrome or soldier’s heart due to the frequency of the condition in combat soldiers. As more was published about the condition, the list of names grew to include Da Costa syndrome, anxiety neurosis, chronic orthostatic intolerance, effort syndrome, idiopathic hypovolemia, mitral valve prolapse syndrome, orthostatic tachycardia, positional tachycardia syndrome, and finally postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome.5,12 Although initially described in men in the military, the condition is more frequently seen in young women from puberty to age 50. Some researchers have proposed that POTS is much more common than recent studies report; they suggest that the condition is underreported both because of the nonspecific nature of the symptoms and because it is not often included in the differential of OI.5

Although some researchers disagree,7,12 most of the literature supports multiple etiologies of POTS.1,2,13 Researchers have divided the syndrome into primary and secondary causes. They have further separated primary POTS into two broad categories based on neuropathic or hyperadrenergic pathology. In both subgroups, POTS is exacerbated by dependent vasodilatation and central hypovolemia.11

In the more common neuropathic POTS, a precipitating factor such as an infection, trauma, pregnancy, or surgery precedes the sudden onset of symptoms. In the majority of patients with neuropathic POTS, high normal to elevated serum norepinephrine (NE) levels are detected, as compared to “normal” controls,5 but known antibodies are not detected. However, in approximately 10% to 15% of patients with a reported antecedent infection, acetylcholine receptor antibodies have been detected.2,14 This form is described in the literature as immune-mediated POTS.2,11,14,15

The less common primary hyperadrenergic POTS presents more insidiously and may have a genetic component. As documented in some families, a point mutation in the NE transporter protein has been shown to slow clearance of NE from the synaptic cleft in the central nervous system. This leads to excessive central sympathetic stimulation of the periphery.12,13,16 Developmental POTS, which presents at puberty with lower extremity neuropathy, is another form of primary POTS and resolves with maturity (see Table 1).6

Secondary POTS can be triggered by several known conditions including alcoholism.12,16 Any disease or insult that damages the peripheral autonomic system may precipitate POTS. Examples include autoimmune diseases, diabetes, chemotherapy, and heavy metal poisoning.13 Genetic disorders have also been associated with or can contribute to secondary POTS. Joint hypermobility syndrome (JHS), also known as Ehlers-Danlos type III, is a genetic disorder characterized by defects in the structure of connective tissue.16 In JHS, the connective tissue in blood vessels is more elastic, leading to greater lower extremity pooling and decreased vasoconstrictive response to sympathetic stimulation on standing. The literature also notes that prolonged bed rest and any medications that contribute to central hypotension or interfere with compensatory peripheral vasoconstriction may precipitate POTS (see Table 2).

On the next page: Clinical presentation and differential diagnosis >>

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Patients with POTS frequently present with a sudden onset of OI related to activity or changes from recumbency to standing. They often identify an illness, accident, or surgery preceding the onset of symptoms. Other clinical manifestations of POTS include acrocyanosis, fatigue, headaches, constitutional hypotension, sleep disturbances, and gastrointestinal symptoms.12,13 Frequently, patients come to the emergency department with chest pain, indigestion, fatigue, and heart palpitations,14,15 concerned that they are having a heart attack. Since symptoms resolve with recumbency and no clinical markers for acute coronary syndromes are found, no further workup is obtained, and patients are sent home with the recommendation to see their primary care provider.

The symptoms of POTS are complex, nonspecific, and debilitating. Fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and tachycardia when standing make activities of daily living such as work, home maintenance, and child care challenging. The unpredictable symptoms make life frustrating for patients and their families. The presenting symptoms, the normal results for routine blood tests, and the lack of cardiac abnormalities often lead providers to a diagnosis of anxiety or panic disorder.13 Since the symptoms of POTS are somewhat mitigated by treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors,16 patients and providers often will accept the diagnosis and not investigate the symptoms further.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis of POTS begins with any condition that causes tachycardia or OI. Clinicians should also consider and rule out cardiac abnormalities such as inappropriate tachycardia, supraventricular tachycardia, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, and other cardiac dysrhythmias. Other diagnoses that should be considered are endocrine abnormalities, including hyperthyroidism, hypoadrenalism, and pheochromocytoma; drug adverse effects and interactions, necessitating scrupulous evaluation of the patient’s medication list; changes in volume status; and kidney disease.1 Causes of autonomic dysfunction in both the peripheral and central nervous system, including Chiari I malformation, need to be scrutinized.17

Many conditions within the differential diagnosis can occur concomitantly with POTS and need to be treated, even as further evaluation continues. An extensive history and review of systems is essential to obtain a complete list of symptoms and lead the clinician toward an appropriate physical exam and necessary adjunct testing.

ASSOCIATED DISORDERS

Of the many conditions associated with POTS, JHS is the most common genetic disorder. In this disorder, a genetic mutation produces changes in the composition of the collagen, resulting in enhanced flexibility and compliance of any tissue with collagen in it.16 Mitral valve prolapse is also associated with JHS and POTS.12

POTS is present in 40% of patients diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome, as well as in a high percentage of those with fibromyalgia.6,7 The many related and comorbid ailments preclude a straightforward diagnosis. Testing for more common illnesses, as well as consideration of associated disorders, is essential in the care of the patient with POTS.

On the next page: Testing and referral >>

TESTING AND REFERRAL

An appropriate workup for POTS includes a complete and thorough history plus a comprehensive physical examination. This includes reviewing the patient’s medication list for any medications or combinations of medications that cause cerebral hypoperfusion, volume depletion, tachycardia, or peripheral vasodilation.2 It is essential to explore the family history for genetic disorders12 and to take a detailed social history, including lifestyle habits that may reproduce the symptoms of POTS.

The definitive diagnosis of POTS is made with a tilt-table test. Obtaining in-office orthostatic vitals can substantially increase the index of suspicion for the syndrome. The procedure used to obtain orthostatic vitals varies by institution. However, every protocol includes a period of rest in a supine position, after which the patient is asked to stand and the blood pressure and pulse are measured after a specified number of minutes. If the patient becomes symptomatic on standing, the blood pressure remains unchanged, and the pulse is elevated to at least 30 beats/min from the supine pulse or greater than 20 beats/min after 10 minutes, a diagnosis of POTS must be considered. Unless a more common cause of the tachycardia is found and treated to resolution, tilt-table testing should be ordered to evaluate these patients for POTS.

If POTS is suspected once the history and physical are completed, the patient should be referred to cardiology or neurology for tilt-table testing to confirm the diagnosis. Laboratory testing should include, but not be limited to, a complete blood count with differential, a comprehensive metabolic panel, Westergren sedimentation rate, and thyroid testing. Adrenal testing,11 a search for vitamin deficiencies, autoimmune diseases, and infective causes (eg, Lyme disease and cytomegalovirus), and urinalysis may also be appropriate based on the patient history and presentation.14

Broad ancillary testing and referral may be needed in patients with POTS. According to Giesken,14 an ECG, echocardiogram, cardiac event monitoring, and an evaluation by a cardiologist are essential. Pasupuleti and Vedre17 recommend referral to a neurologist for evaluation for peripheral and central lesions with electromyography and MRI. Depending on the practice, tilt-table testing may be available through either specialty and may guide the work-up. Referrals to an endocrinologist, a rheumatologist, and a nephrologist to evaluate hyperadrenergic states, autoimmune dysfunction, and kidney disease should be considered as well.14,16 Referrals and additional tests may be necessary, even if secondary causes of POTS are not identified. These tests, although extensive and expensive, may help determine the best and most appropriate treatment options to control the patient’s symptoms and restore quality of life.

On the next page: Treatment >>

TREATMENT

Once the diagnosis of POTS has been confirmed, symptomatic treatment tailored to the patient’s symptoms can begin. Secondary POTS often resolves with effective treatment of the causative disease. One of the most important aspects of effective treatment of primary POTS is to educate patients on how to control their symptoms. Patients must understand that primary POTS cannot be “cured” by current medical therapies. They need to be aware of the erratic symptoms and be proactive in preventing them from occurring. Both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatments are helpful, but a multidisciplinary approach appears to be most efficacious for optimizing return to baseline function in patients.14,16

To prevent exacerbations, patients should avoid situations that precipitate symptoms, such as prolonged standing, inadequate water intake, and cold and hot environments. In addition, providers should advise patients to optimize their fluid status. The literature recommends adding up to 20 g of sodium to the diet daily, and patients should be instructed to drink a minimum of two liters of water during the course of the day.13,16 This includes drinking at least eight ounces of water before rising from a recumbent position. Patients should also be instructed to sleep on an incline7 and to gradually transition to standing when getting up in the morning or after a nap.12 Clinicians should also recommend waist-high graded elastic hose, an abdominal girdle, or both, to assist venous return from the lower extremities and to avoid splanchnic pooling.13

Exercise training has been shown to be effective in treating symptoms of POTS. A recent study published by Fu et al7 demonstrated improved oxygen uptake, increased blood volume, increased cardiac output, and increased left ventricular mass with graduated exercise over a period of several months. The study group demonstrated a lower average resting heart rate and improved exercise tolerance on completion of the trial. In fact, the study reported that after training, more than half of the study patients (10 of 19) no longer fulfilled the criteria for POTS, and all patients who underwent training experienced significant improvements in quality of life.7

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPIES

Pharmacologic therapies for POTS abound. Treatments must be tailored to each patient’s needs based on the suspected or proven etiology of POTS, as well as any associated or comorbid conditions. Fludrocortisone will decrease salt loss and increase plasma volume in patients with hypovolemia. Midodrine improves vasoconstriction in the extremities. Beta-blockers slow the heart rate and prevent vasodilation. Clonidine can lower the blood pressure and decrease the heart rate by preventing central sympathetic stimulation.12 Alternatively, or in conjunction with the other treatment modalities, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may improve sleep, slow the heart rate,16 improve mood, and alleviate gastrointestinal symptoms. As with all medications, clinicians must discuss the risks, benefits, adverse effects, alternatives, and potential interactions with the patient prior to starting medications.

On the next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

POTS most often presents as OI, which is why investigation of OI should include consideration of POTS as part of the differential diagnosis. Untreated, the symptoms of POTS can prevent patients from participating in normal life activities, including recreation, school, and work, leading to dysfunction, disability, and depression.7 A prompt diagnosis, confirmed by tilt-table testing, will expedite appropriate referral, ancillary testing, and treatment. Optimal therapy has not been established, yet individualized patient education, along with the development of a personalized program to alleviate symptoms, will provide patients with a sense of hope and control over the syndrome. This approach will enable patients and their families to manage the condition and optimize their quality of life.

The author would like to thank Michael Whitehead, DHSc, MPAS, PA-C, DFAAPA, an adjunct professor at A. T. Still University in Mesa, Arizona, for his input on this article.

1. Freeman R, Wieling W, Axelrod FB, et al. Consensus statement on the definition of orthostatic hypotension, neurally mediated syncope and the postural tachycardia syndrome.Clin Auton Res. 2011;21:69-72.

2. Johnson JN, Mack KJ, Kuntz NL, et al. Postural orthostatic tachcardia syndrome: a clinical review. Pediatr Neurol. 2009;42:77-85.

3. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institiute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Postural Tachycardia Syndrome Information Page. 2011. www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/postural_tachycardia_syndrome/postural_tachycardia_syndrome.htm. Accessed March 24, 2014.

4. Agarwal AK, Garg R, Ritch A, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:478-480.

5. Jacob G, Costa F, Shannon JR, et al. The neuropathic postural tachycardia syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1008-1014.

6. Staud R. Autonomic dysfunction in fibromyalgia syndrome: postural orthostatic tachycardia. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2008;10:463-466.

7. Fu Q, VanGundy TB, Galbreath MM, et al. Cardiac origins of the postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:

2858-2868.

8. Stewart JM. Postural tachycardia syndrome and reflex syncope: similarities and differences. J Pediatr. 2009;154:481-485.

9. Lanier JB, Mote MB, Clay EC. Evaluation and management of orthostatic hypotension. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:527-536.

10. Ojha A, McNeeley K, Heller E, et al. Orthostatic syndromes differ in syncope frequency. Am J Med. 2010;123:245-249.

11. Graham U, Ritchie KM. Reminder of important clinical lesson: postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009: bcr10.2008.1132. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3029273. Accessed March 24, 2014.

12. Mathias CJ, Low DA, Iodice V, et al. Postural tachycardia syndrome—current experience and concepts. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8:22-34.

13. Thanavaro JL, Thanavaro KL. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. Heart Lung. 2011;40:554-560.

14. Giesken B, Collins M. A 46-year-old woman with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. JAAPA. 2013;26:30-34.

15. Low PA, Sandroni P, Joyner M, et al. Postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS). J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:352-358.

16. Busmer L. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Primary Health Care. 2011;21:16-20.

17. Pasupuleti DV, Vedre A. Postural orthostatic tachycardia warrants investigation of Chiari I malformation as a possible cause. Cardiology. 2005;103:55-56.

1. Freeman R, Wieling W, Axelrod FB, et al. Consensus statement on the definition of orthostatic hypotension, neurally mediated syncope and the postural tachycardia syndrome.Clin Auton Res. 2011;21:69-72.

2. Johnson JN, Mack KJ, Kuntz NL, et al. Postural orthostatic tachcardia syndrome: a clinical review. Pediatr Neurol. 2009;42:77-85.

3. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institiute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Postural Tachycardia Syndrome Information Page. 2011. www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/postural_tachycardia_syndrome/postural_tachycardia_syndrome.htm. Accessed March 24, 2014.

4. Agarwal AK, Garg R, Ritch A, et al. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:478-480.

5. Jacob G, Costa F, Shannon JR, et al. The neuropathic postural tachycardia syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1008-1014.

6. Staud R. Autonomic dysfunction in fibromyalgia syndrome: postural orthostatic tachycardia. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2008;10:463-466.

7. Fu Q, VanGundy TB, Galbreath MM, et al. Cardiac origins of the postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:

2858-2868.

8. Stewart JM. Postural tachycardia syndrome and reflex syncope: similarities and differences. J Pediatr. 2009;154:481-485.

9. Lanier JB, Mote MB, Clay EC. Evaluation and management of orthostatic hypotension. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:527-536.

10. Ojha A, McNeeley K, Heller E, et al. Orthostatic syndromes differ in syncope frequency. Am J Med. 2010;123:245-249.

11. Graham U, Ritchie KM. Reminder of important clinical lesson: postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009: bcr10.2008.1132. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3029273. Accessed March 24, 2014.

12. Mathias CJ, Low DA, Iodice V, et al. Postural tachycardia syndrome—current experience and concepts. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8:22-34.

13. Thanavaro JL, Thanavaro KL. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. Heart Lung. 2011;40:554-560.

14. Giesken B, Collins M. A 46-year-old woman with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. JAAPA. 2013;26:30-34.

15. Low PA, Sandroni P, Joyner M, et al. Postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS). J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009;20:352-358.

16. Busmer L. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Primary Health Care. 2011;21:16-20.

17. Pasupuleti DV, Vedre A. Postural orthostatic tachycardia warrants investigation of Chiari I malformation as a possible cause. Cardiology. 2005;103:55-56.