User login

The "Bottom Line"

In the almost 10 years I have been writing monthly editorials for EM, I frequently find myself searching for a well-known quote I could adapt, or an analogy I could use to emphasize the main point of an editorial. This practice began with the second editorial “Victims of Our Own Success?” (Emerg Med. 2006;38[7]:9), about the June IOM report, “Hospital Based Emergency Care—At the Breaking Point,” describing overcrowded EDs, long lengths of stay, and subsequent ambulance diversions. To sum up the consequences for EDs, I adapted a quote from the late Yogi Berra about a popular restaurant: “Nobody goes there anymore—it’s too crowded.”

In “The Language of Emergency Medicine” (Emerg Med. 2006;38[12]:9) describing nonmedical terminology old and new, applied to medicine, I suggested a Bush administration motto for all of the non-“pay-for-performance” ED patients waiting to be evaluated, and all those the “gatekeeper” keeps waiting for an inpatient bed: “no patient left behind.”

A discussion of the need for appropriate and timely emergency care for the rapidly increasing numbers of elderly ED patients was entitled “It’s About Time” (Emerg Med. 2007;39[1]:7), and ended with “the golden hour” may not be what it used to be, and the “golden years” for most people never were, but there may nevertheless be a “golden opportunity” for emergency medicine to begin dealing with these increasingly important issues now....”

“The Least We Can Do” (Emerg Med. 2007;39[3]:8) compared working in an ED to performing in a theater in the round—for 8 to 12 hours at a time—and went on to bemoan the too-frequent times we walk past patients “like restaurant waiters who are oblivious to all [our] attempts to get their attention.”

In “Remembering Howard Mofenson” (Emerg Med. 2007;39[5]:7), I wrote about the famed Long Island pediatrician, toxicologist, and highly decorated World War II combat medic who was severely injured for the rest of his life. “I learned a great deal about toxicology and medicine from him. But I also learned something even more valuable to an emergency physician…and that was, to quote another World War II hero, Winston Churchill, “Never give in—never, never, never.”

In “The Razor’s Edge” (Emerg Med. 2007;39[6]:8 and Emerg Med. 2014;46[4]:149), I noted that Occam’s razor, aka the “law of parsimony,” is a paradigm often used to urge internists to seek a single diagnosis, such as tuberculosis or sub-acute bacterial endocarditis to account for a multitude of diverse signs and symptoms. But I noted that in emergency medicine, Gillette’s razor—beginning with its twin bladed Trac II and now including up to five separate blades—was a more apt model for ED patients who often have multiple causes for a single symptom, such loss of consciousness precipitated by syncope and followed by head trauma.

“Those Daily Disasters” (Emerg Med. 2008;40[10]:8 and Emerg Med. 2014;46[10]:436), contrasted the almost instant application of all available human and material medical resources to a declared disaster, with the sluggish response to severe ED overcrowding and surges, and asked why one type of disaster was more important than the other. “This seeming oversight is perhaps best expressed in the words of the late comedian George Carlin. “I’m not concerned about all hell breaking loose, but that part of hell will break loose. It will be much harder to detect.”

The “mixed messages” (Emerg Med. 2008;40[11]:8) given to ED patients who we treat in the middle of the night and then ask why they don’t come in the daytime or go to a primary care physician instead, seemed to be best illustrated by a Richard Tripping “art poem” that cleverly redesigned the familiar red and white reversible plastic shop sign to read “Come in, We’re closed” on one side, and “Sorry, We’re Open” on the other.

Finally, at this time of year, for all of those days in the ED when nothing seems to go right and we get yelled at by unhappy hospital colleagues, or by patients frustrated by an ED visit necessitated by an unresolved medical problem, or a long wait for an inpatient bed, I suggested a remake of Frank Capra’s classical film ‘It’s a Wonderful Life,’ (Emerg Med. 2007;39[12]:8) “demonstrating how much worse the world would be if emergency medicine had never been invented….[and calling] it ‘It’s a Wonderful Specialty.’”

Once again, we wish everyone in emergency medicine a wonderful holiday season, and a very happy and healthy New Year.

To start off the New Year next month, more “bottom lines” will be offered.

In the almost 10 years I have been writing monthly editorials for EM, I frequently find myself searching for a well-known quote I could adapt, or an analogy I could use to emphasize the main point of an editorial. This practice began with the second editorial “Victims of Our Own Success?” (Emerg Med. 2006;38[7]:9), about the June IOM report, “Hospital Based Emergency Care—At the Breaking Point,” describing overcrowded EDs, long lengths of stay, and subsequent ambulance diversions. To sum up the consequences for EDs, I adapted a quote from the late Yogi Berra about a popular restaurant: “Nobody goes there anymore—it’s too crowded.”

In “The Language of Emergency Medicine” (Emerg Med. 2006;38[12]:9) describing nonmedical terminology old and new, applied to medicine, I suggested a Bush administration motto for all of the non-“pay-for-performance” ED patients waiting to be evaluated, and all those the “gatekeeper” keeps waiting for an inpatient bed: “no patient left behind.”

A discussion of the need for appropriate and timely emergency care for the rapidly increasing numbers of elderly ED patients was entitled “It’s About Time” (Emerg Med. 2007;39[1]:7), and ended with “the golden hour” may not be what it used to be, and the “golden years” for most people never were, but there may nevertheless be a “golden opportunity” for emergency medicine to begin dealing with these increasingly important issues now....”

“The Least We Can Do” (Emerg Med. 2007;39[3]:8) compared working in an ED to performing in a theater in the round—for 8 to 12 hours at a time—and went on to bemoan the too-frequent times we walk past patients “like restaurant waiters who are oblivious to all [our] attempts to get their attention.”

In “Remembering Howard Mofenson” (Emerg Med. 2007;39[5]:7), I wrote about the famed Long Island pediatrician, toxicologist, and highly decorated World War II combat medic who was severely injured for the rest of his life. “I learned a great deal about toxicology and medicine from him. But I also learned something even more valuable to an emergency physician…and that was, to quote another World War II hero, Winston Churchill, “Never give in—never, never, never.”

In “The Razor’s Edge” (Emerg Med. 2007;39[6]:8 and Emerg Med. 2014;46[4]:149), I noted that Occam’s razor, aka the “law of parsimony,” is a paradigm often used to urge internists to seek a single diagnosis, such as tuberculosis or sub-acute bacterial endocarditis to account for a multitude of diverse signs and symptoms. But I noted that in emergency medicine, Gillette’s razor—beginning with its twin bladed Trac II and now including up to five separate blades—was a more apt model for ED patients who often have multiple causes for a single symptom, such loss of consciousness precipitated by syncope and followed by head trauma.

“Those Daily Disasters” (Emerg Med. 2008;40[10]:8 and Emerg Med. 2014;46[10]:436), contrasted the almost instant application of all available human and material medical resources to a declared disaster, with the sluggish response to severe ED overcrowding and surges, and asked why one type of disaster was more important than the other. “This seeming oversight is perhaps best expressed in the words of the late comedian George Carlin. “I’m not concerned about all hell breaking loose, but that part of hell will break loose. It will be much harder to detect.”

The “mixed messages” (Emerg Med. 2008;40[11]:8) given to ED patients who we treat in the middle of the night and then ask why they don’t come in the daytime or go to a primary care physician instead, seemed to be best illustrated by a Richard Tripping “art poem” that cleverly redesigned the familiar red and white reversible plastic shop sign to read “Come in, We’re closed” on one side, and “Sorry, We’re Open” on the other.

Finally, at this time of year, for all of those days in the ED when nothing seems to go right and we get yelled at by unhappy hospital colleagues, or by patients frustrated by an ED visit necessitated by an unresolved medical problem, or a long wait for an inpatient bed, I suggested a remake of Frank Capra’s classical film ‘It’s a Wonderful Life,’ (Emerg Med. 2007;39[12]:8) “demonstrating how much worse the world would be if emergency medicine had never been invented….[and calling] it ‘It’s a Wonderful Specialty.’”

Once again, we wish everyone in emergency medicine a wonderful holiday season, and a very happy and healthy New Year.

To start off the New Year next month, more “bottom lines” will be offered.

In the almost 10 years I have been writing monthly editorials for EM, I frequently find myself searching for a well-known quote I could adapt, or an analogy I could use to emphasize the main point of an editorial. This practice began with the second editorial “Victims of Our Own Success?” (Emerg Med. 2006;38[7]:9), about the June IOM report, “Hospital Based Emergency Care—At the Breaking Point,” describing overcrowded EDs, long lengths of stay, and subsequent ambulance diversions. To sum up the consequences for EDs, I adapted a quote from the late Yogi Berra about a popular restaurant: “Nobody goes there anymore—it’s too crowded.”

In “The Language of Emergency Medicine” (Emerg Med. 2006;38[12]:9) describing nonmedical terminology old and new, applied to medicine, I suggested a Bush administration motto for all of the non-“pay-for-performance” ED patients waiting to be evaluated, and all those the “gatekeeper” keeps waiting for an inpatient bed: “no patient left behind.”

A discussion of the need for appropriate and timely emergency care for the rapidly increasing numbers of elderly ED patients was entitled “It’s About Time” (Emerg Med. 2007;39[1]:7), and ended with “the golden hour” may not be what it used to be, and the “golden years” for most people never were, but there may nevertheless be a “golden opportunity” for emergency medicine to begin dealing with these increasingly important issues now....”

“The Least We Can Do” (Emerg Med. 2007;39[3]:8) compared working in an ED to performing in a theater in the round—for 8 to 12 hours at a time—and went on to bemoan the too-frequent times we walk past patients “like restaurant waiters who are oblivious to all [our] attempts to get their attention.”

In “Remembering Howard Mofenson” (Emerg Med. 2007;39[5]:7), I wrote about the famed Long Island pediatrician, toxicologist, and highly decorated World War II combat medic who was severely injured for the rest of his life. “I learned a great deal about toxicology and medicine from him. But I also learned something even more valuable to an emergency physician…and that was, to quote another World War II hero, Winston Churchill, “Never give in—never, never, never.”

In “The Razor’s Edge” (Emerg Med. 2007;39[6]:8 and Emerg Med. 2014;46[4]:149), I noted that Occam’s razor, aka the “law of parsimony,” is a paradigm often used to urge internists to seek a single diagnosis, such as tuberculosis or sub-acute bacterial endocarditis to account for a multitude of diverse signs and symptoms. But I noted that in emergency medicine, Gillette’s razor—beginning with its twin bladed Trac II and now including up to five separate blades—was a more apt model for ED patients who often have multiple causes for a single symptom, such loss of consciousness precipitated by syncope and followed by head trauma.

“Those Daily Disasters” (Emerg Med. 2008;40[10]:8 and Emerg Med. 2014;46[10]:436), contrasted the almost instant application of all available human and material medical resources to a declared disaster, with the sluggish response to severe ED overcrowding and surges, and asked why one type of disaster was more important than the other. “This seeming oversight is perhaps best expressed in the words of the late comedian George Carlin. “I’m not concerned about all hell breaking loose, but that part of hell will break loose. It will be much harder to detect.”

The “mixed messages” (Emerg Med. 2008;40[11]:8) given to ED patients who we treat in the middle of the night and then ask why they don’t come in the daytime or go to a primary care physician instead, seemed to be best illustrated by a Richard Tripping “art poem” that cleverly redesigned the familiar red and white reversible plastic shop sign to read “Come in, We’re closed” on one side, and “Sorry, We’re Open” on the other.

Finally, at this time of year, for all of those days in the ED when nothing seems to go right and we get yelled at by unhappy hospital colleagues, or by patients frustrated by an ED visit necessitated by an unresolved medical problem, or a long wait for an inpatient bed, I suggested a remake of Frank Capra’s classical film ‘It’s a Wonderful Life,’ (Emerg Med. 2007;39[12]:8) “demonstrating how much worse the world would be if emergency medicine had never been invented….[and calling] it ‘It’s a Wonderful Specialty.’”

Once again, we wish everyone in emergency medicine a wonderful holiday season, and a very happy and healthy New Year.

To start off the New Year next month, more “bottom lines” will be offered.

“Best ED”- News You Can Use*?

Among the many organizations that rate hospitals and medical care—CMS, JCAHO, and Consumer Reports, to name a few—one that has captured the public’s attention since 1990 is the US News & World Report (USNWR) annual list of best hospitals, which includes its “honor roll” of the 15 very best. Yet, emergency medicine (EM) has never been included among the ranked specialties, raising the question, should the “best hospitals” have the best EDs?

Formerly a weekly newsmagazine and now web-based, USNWR still publishes print editions of its popular annual best colleges and best hospitals listings. Widely read and widely reported in other media, the lists appear to resonate strongly with the public, as well as with college and hospital administrators. But what exactly is meant by best? In a press release accompanying its 2015-16 best hospitals list, USNWR describes the purpose of the list as “designed to help patients with life threatening or rare conditions identify hospitals that excel in treating the most difficult cases,” and its honor roll as a list that “highlights hospitals that are exceptional in 16 specialties” (http://www.usnews.com/info/blogs/press-room/2015/07/21/us-news-releases-201516-best-hospitals). Specialties not included, in addition to EM, are internal medicine and surgery, which are represented by subspecialties, or service lines. The ranked list includes cardiology and heart surgery; diabetes and endocrinology; gastroenterology and GI surgery; geriatrics; nephrology; neurology and neurosurgery; pulmonology; rheumatology; and urology. Presumably, like medicine and surgery, EM is too all-encompassing a discipline, but unlike the case for the other two specialties, the need for emergency care in most locations does not allow patients to select the “best” facility for their acute problem. Nevertheless, it is interesting to speculate about the effect inclusion of EM would have on the elite institutions vying for honor roll status, as well as on EM itself.

A July 15, 2015 report on USNWR methodology (http://www.usnews.com/pubfiles/BH2015-16MethodologyReport.pdf) (http://www.usnews.com/info/blogs/press-room/2015/07/21/us-news-releases-201516-best-hospitals) notes that rankings in 12 of the 16 specialties are based on data-driven analyses of volume; technology and other resources (derived principally from the American Hospital Association annual survey); reputation for developing and sustaining the delivery of high-quality care (derived from surveyed physicians); and outcomes-based mostly on CMS risk-adjusted mortality figures. Rankings in the remaining four specialties are based solely on physician surveys of hospital reputation. Hospitals eligible for inclusion on the best hospitals list must either be teaching hospitals, be affiliated with medical schools, or, generally, have 200 or more beds.

Most, if not all, of these criteria can be applied to ranking EDs, but would doing so provide a valid assessment of the best EDs, and if so, to what end? The first question is too complicated to answer here. As for the second, many have argued that the “best ED” isn’t a relevant concept, considering that standards of emergency care demanded of every ED and emergency physician by ABEM, ACEP, ABMS, JCAHO, and more recently, CMS, have been promulgated and implemented nationwide for over three-and-a-half decades. But for the select few hospitals competing for the title of “best,” inclusion of EM among ranked specialties would send a very powerful message and require increased resources to achieve and maintain top standing. Even if EM is not ranked as a discrete specialty, many of the features of a “best ED” can and should be included. Currently, hospitals receive 1 point for being a state-certified, level 1 or level 2 trauma center. Points for other ED “center” designations could also be applied to a hospital’s overall score.

In any case, should USNWR include EM in future best hospitals listings, perhaps many of the measures that will be taken by hospitals to claim the title of “best ED” could subsequently become standard operating procedure for all EDs. So, let the games begin.

*“News You Can Use” is a column that ran in USNWR beginning in 1952.

Among the many organizations that rate hospitals and medical care—CMS, JCAHO, and Consumer Reports, to name a few—one that has captured the public’s attention since 1990 is the US News & World Report (USNWR) annual list of best hospitals, which includes its “honor roll” of the 15 very best. Yet, emergency medicine (EM) has never been included among the ranked specialties, raising the question, should the “best hospitals” have the best EDs?

Formerly a weekly newsmagazine and now web-based, USNWR still publishes print editions of its popular annual best colleges and best hospitals listings. Widely read and widely reported in other media, the lists appear to resonate strongly with the public, as well as with college and hospital administrators. But what exactly is meant by best? In a press release accompanying its 2015-16 best hospitals list, USNWR describes the purpose of the list as “designed to help patients with life threatening or rare conditions identify hospitals that excel in treating the most difficult cases,” and its honor roll as a list that “highlights hospitals that are exceptional in 16 specialties” (http://www.usnews.com/info/blogs/press-room/2015/07/21/us-news-releases-201516-best-hospitals). Specialties not included, in addition to EM, are internal medicine and surgery, which are represented by subspecialties, or service lines. The ranked list includes cardiology and heart surgery; diabetes and endocrinology; gastroenterology and GI surgery; geriatrics; nephrology; neurology and neurosurgery; pulmonology; rheumatology; and urology. Presumably, like medicine and surgery, EM is too all-encompassing a discipline, but unlike the case for the other two specialties, the need for emergency care in most locations does not allow patients to select the “best” facility for their acute problem. Nevertheless, it is interesting to speculate about the effect inclusion of EM would have on the elite institutions vying for honor roll status, as well as on EM itself.

A July 15, 2015 report on USNWR methodology (http://www.usnews.com/pubfiles/BH2015-16MethodologyReport.pdf) (http://www.usnews.com/info/blogs/press-room/2015/07/21/us-news-releases-201516-best-hospitals) notes that rankings in 12 of the 16 specialties are based on data-driven analyses of volume; technology and other resources (derived principally from the American Hospital Association annual survey); reputation for developing and sustaining the delivery of high-quality care (derived from surveyed physicians); and outcomes-based mostly on CMS risk-adjusted mortality figures. Rankings in the remaining four specialties are based solely on physician surveys of hospital reputation. Hospitals eligible for inclusion on the best hospitals list must either be teaching hospitals, be affiliated with medical schools, or, generally, have 200 or more beds.

Most, if not all, of these criteria can be applied to ranking EDs, but would doing so provide a valid assessment of the best EDs, and if so, to what end? The first question is too complicated to answer here. As for the second, many have argued that the “best ED” isn’t a relevant concept, considering that standards of emergency care demanded of every ED and emergency physician by ABEM, ACEP, ABMS, JCAHO, and more recently, CMS, have been promulgated and implemented nationwide for over three-and-a-half decades. But for the select few hospitals competing for the title of “best,” inclusion of EM among ranked specialties would send a very powerful message and require increased resources to achieve and maintain top standing. Even if EM is not ranked as a discrete specialty, many of the features of a “best ED” can and should be included. Currently, hospitals receive 1 point for being a state-certified, level 1 or level 2 trauma center. Points for other ED “center” designations could also be applied to a hospital’s overall score.

In any case, should USNWR include EM in future best hospitals listings, perhaps many of the measures that will be taken by hospitals to claim the title of “best ED” could subsequently become standard operating procedure for all EDs. So, let the games begin.

*“News You Can Use” is a column that ran in USNWR beginning in 1952.

Among the many organizations that rate hospitals and medical care—CMS, JCAHO, and Consumer Reports, to name a few—one that has captured the public’s attention since 1990 is the US News & World Report (USNWR) annual list of best hospitals, which includes its “honor roll” of the 15 very best. Yet, emergency medicine (EM) has never been included among the ranked specialties, raising the question, should the “best hospitals” have the best EDs?

Formerly a weekly newsmagazine and now web-based, USNWR still publishes print editions of its popular annual best colleges and best hospitals listings. Widely read and widely reported in other media, the lists appear to resonate strongly with the public, as well as with college and hospital administrators. But what exactly is meant by best? In a press release accompanying its 2015-16 best hospitals list, USNWR describes the purpose of the list as “designed to help patients with life threatening or rare conditions identify hospitals that excel in treating the most difficult cases,” and its honor roll as a list that “highlights hospitals that are exceptional in 16 specialties” (http://www.usnews.com/info/blogs/press-room/2015/07/21/us-news-releases-201516-best-hospitals). Specialties not included, in addition to EM, are internal medicine and surgery, which are represented by subspecialties, or service lines. The ranked list includes cardiology and heart surgery; diabetes and endocrinology; gastroenterology and GI surgery; geriatrics; nephrology; neurology and neurosurgery; pulmonology; rheumatology; and urology. Presumably, like medicine and surgery, EM is too all-encompassing a discipline, but unlike the case for the other two specialties, the need for emergency care in most locations does not allow patients to select the “best” facility for their acute problem. Nevertheless, it is interesting to speculate about the effect inclusion of EM would have on the elite institutions vying for honor roll status, as well as on EM itself.

A July 15, 2015 report on USNWR methodology (http://www.usnews.com/pubfiles/BH2015-16MethodologyReport.pdf) (http://www.usnews.com/info/blogs/press-room/2015/07/21/us-news-releases-201516-best-hospitals) notes that rankings in 12 of the 16 specialties are based on data-driven analyses of volume; technology and other resources (derived principally from the American Hospital Association annual survey); reputation for developing and sustaining the delivery of high-quality care (derived from surveyed physicians); and outcomes-based mostly on CMS risk-adjusted mortality figures. Rankings in the remaining four specialties are based solely on physician surveys of hospital reputation. Hospitals eligible for inclusion on the best hospitals list must either be teaching hospitals, be affiliated with medical schools, or, generally, have 200 or more beds.

Most, if not all, of these criteria can be applied to ranking EDs, but would doing so provide a valid assessment of the best EDs, and if so, to what end? The first question is too complicated to answer here. As for the second, many have argued that the “best ED” isn’t a relevant concept, considering that standards of emergency care demanded of every ED and emergency physician by ABEM, ACEP, ABMS, JCAHO, and more recently, CMS, have been promulgated and implemented nationwide for over three-and-a-half decades. But for the select few hospitals competing for the title of “best,” inclusion of EM among ranked specialties would send a very powerful message and require increased resources to achieve and maintain top standing. Even if EM is not ranked as a discrete specialty, many of the features of a “best ED” can and should be included. Currently, hospitals receive 1 point for being a state-certified, level 1 or level 2 trauma center. Points for other ED “center” designations could also be applied to a hospital’s overall score.

In any case, should USNWR include EM in future best hospitals listings, perhaps many of the measures that will be taken by hospitals to claim the title of “best ED” could subsequently become standard operating procedure for all EDs. So, let the games begin.

*“News You Can Use” is a column that ran in USNWR beginning in 1952.

Harold Osborn, MD, Paul Krochmal, MD, and ACEP Scientific Assembly

Several years ago, I read an op-ed piece in the New York Times about how celebrating Christmas is different for children and adults. While most children experience pure joy, adults’ joy is usually tempered with the sadness of thinking about family members and friends who were part of past celebrations but have since passed away. So too, now when I attend annual ACEP scientific assemblies, my thoughts frequently turn to some of the pioneering emergency physicians (EPs) who I no longer encounter in the convention center hallways, session rooms, and exhibition halls. |

At ACEP this year, I will be thinking a lot about Harold Osborn, MD, who died at the age of 71 after a long illness in New Rochelle, NY on April 30, 2015 (http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/nytimes/obituary.aspx?pid=175075119). “Oz” was a striking figure in the ED and in the corridors of ACEP meetings over the years, as his ponytail turned from black to white. Having embraced radical politics by the time he obtained his MD degree from Columbia University in 1970, Oz was a fierce advocate of healthcare reform, particularly emergency medicine (EM) and health issues affecting poor and minority populations. During residency training at Lincoln Hospital in the South Bronx, Oz organized and led community-oriented care initiatives, including detox and holistic medicine programs. He also was a leading advocate of more rational working conditions for house officers a decade before work-hour reform became part of the New York State health code and later nationwide ACGME standards.

At times Oz’s unrelenting zeal could make you crazy, but he would also be the first person to come to your aid, or defense, if there was a need. As an EP with a growing interest in treating overdoses and poisonings in the Bronx, Oz worked with Lewis Goldfrank, MD, with whom he coauthored many early chapters of Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies. In 1993, Oz became one of the first academic chairs of EM in the New York metropolitan area.

In a career spanning more than 30 years, Oz never hesitated to champion a health-related cause he believed in—often at great personal risk and sacrifice. His strong advocacy helped elevate the standards for New York City receiving hospital EDs, even as many worried that his moving so fast would prompt an unsympathetic healthcare establishment to take back recent EM gains. Looking back now, almost everything Oz fought for has become standard practice for EM in New York and elsewhere.

I will also be thinking about Paul Krochmal, MD, at ACEP this year. Paul, who died unexpectedly in his sleep at the age of 67, on August 25, 2015, was one of the very first EM residents trained at Einstein/Jacobi Hospital in the Bronx, at a time when the entire residency consisted of three residents in each of 2 years. An imposing figure with a thick mustache longer then the handlebar of his BMW motorcycle, Paul was smart, skilled, gentle, and understanding. He befriended everyone he met and was an effective ambassador for EM in the days when the rest of academia had trouble figuring out who we were and how we fit in.

If you would like to read about how one EP can profoundly affect the lives of so many members of his community, and about the truly inspiring legacy Paul leaves behind, read the short obituary about him followed by more than 60 brief tributes, in the August 27, 2015 issue of the Southington Citizen (http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/thesouthingtoncitizen/obituary.aspx?pid=175654394).

As for the pure joy of youth, I still remember clearly the first ACEP Scientific Assembly I attended in San Francisco, in 1977. Registering late, I couldn’t obtain a room at any of the convention hotels and ended up staying at the Hotel California—really! I suppose it’s fair to say that, paraphrasing the song of the same name, I may have checked out after the meeting, but part of me never left.

Several years ago, I read an op-ed piece in the New York Times about how celebrating Christmas is different for children and adults. While most children experience pure joy, adults’ joy is usually tempered with the sadness of thinking about family members and friends who were part of past celebrations but have since passed away. So too, now when I attend annual ACEP scientific assemblies, my thoughts frequently turn to some of the pioneering emergency physicians (EPs) who I no longer encounter in the convention center hallways, session rooms, and exhibition halls. |

At ACEP this year, I will be thinking a lot about Harold Osborn, MD, who died at the age of 71 after a long illness in New Rochelle, NY on April 30, 2015 (http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/nytimes/obituary.aspx?pid=175075119). “Oz” was a striking figure in the ED and in the corridors of ACEP meetings over the years, as his ponytail turned from black to white. Having embraced radical politics by the time he obtained his MD degree from Columbia University in 1970, Oz was a fierce advocate of healthcare reform, particularly emergency medicine (EM) and health issues affecting poor and minority populations. During residency training at Lincoln Hospital in the South Bronx, Oz organized and led community-oriented care initiatives, including detox and holistic medicine programs. He also was a leading advocate of more rational working conditions for house officers a decade before work-hour reform became part of the New York State health code and later nationwide ACGME standards.

At times Oz’s unrelenting zeal could make you crazy, but he would also be the first person to come to your aid, or defense, if there was a need. As an EP with a growing interest in treating overdoses and poisonings in the Bronx, Oz worked with Lewis Goldfrank, MD, with whom he coauthored many early chapters of Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies. In 1993, Oz became one of the first academic chairs of EM in the New York metropolitan area.

In a career spanning more than 30 years, Oz never hesitated to champion a health-related cause he believed in—often at great personal risk and sacrifice. His strong advocacy helped elevate the standards for New York City receiving hospital EDs, even as many worried that his moving so fast would prompt an unsympathetic healthcare establishment to take back recent EM gains. Looking back now, almost everything Oz fought for has become standard practice for EM in New York and elsewhere.

I will also be thinking about Paul Krochmal, MD, at ACEP this year. Paul, who died unexpectedly in his sleep at the age of 67, on August 25, 2015, was one of the very first EM residents trained at Einstein/Jacobi Hospital in the Bronx, at a time when the entire residency consisted of three residents in each of 2 years. An imposing figure with a thick mustache longer then the handlebar of his BMW motorcycle, Paul was smart, skilled, gentle, and understanding. He befriended everyone he met and was an effective ambassador for EM in the days when the rest of academia had trouble figuring out who we were and how we fit in.

If you would like to read about how one EP can profoundly affect the lives of so many members of his community, and about the truly inspiring legacy Paul leaves behind, read the short obituary about him followed by more than 60 brief tributes, in the August 27, 2015 issue of the Southington Citizen (http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/thesouthingtoncitizen/obituary.aspx?pid=175654394).

As for the pure joy of youth, I still remember clearly the first ACEP Scientific Assembly I attended in San Francisco, in 1977. Registering late, I couldn’t obtain a room at any of the convention hotels and ended up staying at the Hotel California—really! I suppose it’s fair to say that, paraphrasing the song of the same name, I may have checked out after the meeting, but part of me never left.

Several years ago, I read an op-ed piece in the New York Times about how celebrating Christmas is different for children and adults. While most children experience pure joy, adults’ joy is usually tempered with the sadness of thinking about family members and friends who were part of past celebrations but have since passed away. So too, now when I attend annual ACEP scientific assemblies, my thoughts frequently turn to some of the pioneering emergency physicians (EPs) who I no longer encounter in the convention center hallways, session rooms, and exhibition halls. |

At ACEP this year, I will be thinking a lot about Harold Osborn, MD, who died at the age of 71 after a long illness in New Rochelle, NY on April 30, 2015 (http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/nytimes/obituary.aspx?pid=175075119). “Oz” was a striking figure in the ED and in the corridors of ACEP meetings over the years, as his ponytail turned from black to white. Having embraced radical politics by the time he obtained his MD degree from Columbia University in 1970, Oz was a fierce advocate of healthcare reform, particularly emergency medicine (EM) and health issues affecting poor and minority populations. During residency training at Lincoln Hospital in the South Bronx, Oz organized and led community-oriented care initiatives, including detox and holistic medicine programs. He also was a leading advocate of more rational working conditions for house officers a decade before work-hour reform became part of the New York State health code and later nationwide ACGME standards.

At times Oz’s unrelenting zeal could make you crazy, but he would also be the first person to come to your aid, or defense, if there was a need. As an EP with a growing interest in treating overdoses and poisonings in the Bronx, Oz worked with Lewis Goldfrank, MD, with whom he coauthored many early chapters of Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies. In 1993, Oz became one of the first academic chairs of EM in the New York metropolitan area.

In a career spanning more than 30 years, Oz never hesitated to champion a health-related cause he believed in—often at great personal risk and sacrifice. His strong advocacy helped elevate the standards for New York City receiving hospital EDs, even as many worried that his moving so fast would prompt an unsympathetic healthcare establishment to take back recent EM gains. Looking back now, almost everything Oz fought for has become standard practice for EM in New York and elsewhere.

I will also be thinking about Paul Krochmal, MD, at ACEP this year. Paul, who died unexpectedly in his sleep at the age of 67, on August 25, 2015, was one of the very first EM residents trained at Einstein/Jacobi Hospital in the Bronx, at a time when the entire residency consisted of three residents in each of 2 years. An imposing figure with a thick mustache longer then the handlebar of his BMW motorcycle, Paul was smart, skilled, gentle, and understanding. He befriended everyone he met and was an effective ambassador for EM in the days when the rest of academia had trouble figuring out who we were and how we fit in.

If you would like to read about how one EP can profoundly affect the lives of so many members of his community, and about the truly inspiring legacy Paul leaves behind, read the short obituary about him followed by more than 60 brief tributes, in the August 27, 2015 issue of the Southington Citizen (http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/thesouthingtoncitizen/obituary.aspx?pid=175654394).

As for the pure joy of youth, I still remember clearly the first ACEP Scientific Assembly I attended in San Francisco, in 1977. Registering late, I couldn’t obtain a room at any of the convention hotels and ended up staying at the Hotel California—really! I suppose it’s fair to say that, paraphrasing the song of the same name, I may have checked out after the meeting, but part of me never left.

Unsung Heroes: ED Social Workers

When we think of essential nonphysician ED staff and the roles they play in the successful management of our patients, we tend to think of nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, technicians, pharmacists, patient representatives, and even transporters, housekeepers, and clerks. But we typically overlook the ED social worker, without whose efforts the modern ED would come to a grinding halt. In the early years after emergency medicine (EM) became a specialty, few, if any, EDs were staffed around the clock by social workers. This was true even in the county and municipal acute care hospitals now referred to as “safety net” hospitals.

In those days, the role of the ED social worker frequently centered around contacting the appropriate agencies for cases of child abuse and sexual assault and arranging transportation or shelter for patients who were to be discharged from the ED.

But just as the roles of EM and EDs have evolved and expanded enormously in recent decades, so too has the role of and need for ED social workers. The presence of a skilled ED social worker will almost always make it possible to safely discharge several patients a day to their homes—with arrangements made for the services and medical equipment needed—instead of admitting them to inpatient beds. Such needed services include physical and occupational therapists, visiting nurses for wound care, medication management, blood work, intravenous infusions, and meal preparation and delivery (“Meals on Wheels,” etc). Durable medical equipment needs include bedside commodes, rails, grab bars, and hospital beds. Even preventive medicine is now initiated by the ED social worker, who arranges for age-appropriate home-safety assessments and equipment installations for the increasing number of elderly who have “aged in place” in the same dwelling over many years.

As the percentage of ED patients over the age of 65—currently 18%—continues to rise during the next 40 to 50 years, the need for skilled ED social workers is increasing exponentially. There is frequently a need to temporarily relocate older discharged ED patients with families or friends when they are alone, for assessing whether a spouse or family member is capable of caring for a discharged patient at home, and even for arranging care of a pet for patients who live alone and require admission. Another way of looking at the current situation is that EDs now serve two clients—our patients and the hospital and healthcare system. Many patients who were formerly admitted to hospitals are now expected to be sent home from the ED to avoid diminishing hospital reimbursement for short-stay “observation services,” or denials. At the same time, the complex range and degree of health insurance coverage that patients have, and the scarce availability of appropriate, timely physician follow-up, are beyond the ability of an EP to deal with while continuing to care for other patients.

As the number of ED patients eligible for Medicare and Medicaid continues to rise, and the benefits are linked to changing requirements for length and type of care (“two-midnight rule” and observation services, for example), the 24/7 ED social worker has become a truly essential member of the ED staff—and now is the time to start ramping up the coverage.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank NewYork Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center ED Social Workers, George Haskell, LMSW, and Laura Kramer, LMSW, for providing details regarding the home services and equipment they arrange for patients discharged from our ED.

When we think of essential nonphysician ED staff and the roles they play in the successful management of our patients, we tend to think of nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, technicians, pharmacists, patient representatives, and even transporters, housekeepers, and clerks. But we typically overlook the ED social worker, without whose efforts the modern ED would come to a grinding halt. In the early years after emergency medicine (EM) became a specialty, few, if any, EDs were staffed around the clock by social workers. This was true even in the county and municipal acute care hospitals now referred to as “safety net” hospitals.

In those days, the role of the ED social worker frequently centered around contacting the appropriate agencies for cases of child abuse and sexual assault and arranging transportation or shelter for patients who were to be discharged from the ED.

But just as the roles of EM and EDs have evolved and expanded enormously in recent decades, so too has the role of and need for ED social workers. The presence of a skilled ED social worker will almost always make it possible to safely discharge several patients a day to their homes—with arrangements made for the services and medical equipment needed—instead of admitting them to inpatient beds. Such needed services include physical and occupational therapists, visiting nurses for wound care, medication management, blood work, intravenous infusions, and meal preparation and delivery (“Meals on Wheels,” etc). Durable medical equipment needs include bedside commodes, rails, grab bars, and hospital beds. Even preventive medicine is now initiated by the ED social worker, who arranges for age-appropriate home-safety assessments and equipment installations for the increasing number of elderly who have “aged in place” in the same dwelling over many years.

As the percentage of ED patients over the age of 65—currently 18%—continues to rise during the next 40 to 50 years, the need for skilled ED social workers is increasing exponentially. There is frequently a need to temporarily relocate older discharged ED patients with families or friends when they are alone, for assessing whether a spouse or family member is capable of caring for a discharged patient at home, and even for arranging care of a pet for patients who live alone and require admission. Another way of looking at the current situation is that EDs now serve two clients—our patients and the hospital and healthcare system. Many patients who were formerly admitted to hospitals are now expected to be sent home from the ED to avoid diminishing hospital reimbursement for short-stay “observation services,” or denials. At the same time, the complex range and degree of health insurance coverage that patients have, and the scarce availability of appropriate, timely physician follow-up, are beyond the ability of an EP to deal with while continuing to care for other patients.

As the number of ED patients eligible for Medicare and Medicaid continues to rise, and the benefits are linked to changing requirements for length and type of care (“two-midnight rule” and observation services, for example), the 24/7 ED social worker has become a truly essential member of the ED staff—and now is the time to start ramping up the coverage.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank NewYork Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center ED Social Workers, George Haskell, LMSW, and Laura Kramer, LMSW, for providing details regarding the home services and equipment they arrange for patients discharged from our ED.

When we think of essential nonphysician ED staff and the roles they play in the successful management of our patients, we tend to think of nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, technicians, pharmacists, patient representatives, and even transporters, housekeepers, and clerks. But we typically overlook the ED social worker, without whose efforts the modern ED would come to a grinding halt. In the early years after emergency medicine (EM) became a specialty, few, if any, EDs were staffed around the clock by social workers. This was true even in the county and municipal acute care hospitals now referred to as “safety net” hospitals.

In those days, the role of the ED social worker frequently centered around contacting the appropriate agencies for cases of child abuse and sexual assault and arranging transportation or shelter for patients who were to be discharged from the ED.

But just as the roles of EM and EDs have evolved and expanded enormously in recent decades, so too has the role of and need for ED social workers. The presence of a skilled ED social worker will almost always make it possible to safely discharge several patients a day to their homes—with arrangements made for the services and medical equipment needed—instead of admitting them to inpatient beds. Such needed services include physical and occupational therapists, visiting nurses for wound care, medication management, blood work, intravenous infusions, and meal preparation and delivery (“Meals on Wheels,” etc). Durable medical equipment needs include bedside commodes, rails, grab bars, and hospital beds. Even preventive medicine is now initiated by the ED social worker, who arranges for age-appropriate home-safety assessments and equipment installations for the increasing number of elderly who have “aged in place” in the same dwelling over many years.

As the percentage of ED patients over the age of 65—currently 18%—continues to rise during the next 40 to 50 years, the need for skilled ED social workers is increasing exponentially. There is frequently a need to temporarily relocate older discharged ED patients with families or friends when they are alone, for assessing whether a spouse or family member is capable of caring for a discharged patient at home, and even for arranging care of a pet for patients who live alone and require admission. Another way of looking at the current situation is that EDs now serve two clients—our patients and the hospital and healthcare system. Many patients who were formerly admitted to hospitals are now expected to be sent home from the ED to avoid diminishing hospital reimbursement for short-stay “observation services,” or denials. At the same time, the complex range and degree of health insurance coverage that patients have, and the scarce availability of appropriate, timely physician follow-up, are beyond the ability of an EP to deal with while continuing to care for other patients.

As the number of ED patients eligible for Medicare and Medicaid continues to rise, and the benefits are linked to changing requirements for length and type of care (“two-midnight rule” and observation services, for example), the 24/7 ED social worker has become a truly essential member of the ED staff—and now is the time to start ramping up the coverage.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank NewYork Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center ED Social Workers, George Haskell, LMSW, and Laura Kramer, LMSW, for providing details regarding the home services and equipment they arrange for patients discharged from our ED.

"The Times They Are A-Changin"

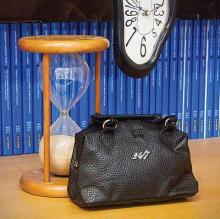

In April 1977, shortly after the new American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM) was constituted, it adopted the hourglass as its symbol for the unique nature of emergency medicine—a specialty in large part defined by the very brief time in which emergency physicians (EPs) must correctly identify and treat serious, life-threatening conditions. Incorporating the concept of the “golden hour” in which to prevent the irreversible consequences of serious trauma, and the frequently even shorter period to effectively intervene after cardiovascular and neurovascular catastrophes, the hourglass has become a powerful symbol that all emergency physicians are very, very proud of.

In the years since the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) recognized Emergency Medicine as the 23rd specialty, though much about emergency medicine has remained the same, much has also changed. Currently, the time patients spend in EDs throughout the country is all too frequently determined, not by the time required to diagnose and initiate treatment for their illnesses, but by the time required for an inpatient bed to become available or for safe, reliable outpatient care to be arranged. In some hospitals, ED patients who are admitted and require inpatient care or “observation services” continue to be cared for by EPs and ED nurses, while in other hospitals the care and responsibility for such patients is transferred to the appropriate inpatient service—even as the patients remain for hours or days on ED stretchers on the ground floor of the hospital. In some cases, an entire “hospitalization” takes place in the ED.

Similarly, when the specialty of emergency medicine was first established, it faced not only time, but resource-limitations as well. Few CT scanners then were commonly available in close proximity to EDs; afterward, when CT scans did become easily accessible to ED patients and MRI scanners began to appear, no one considered MRI scans to be “ED procedures” because of the time required to complete the studies. This, of course, was before managed-care appeared on the scene and, more recently, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) began to seriously question the need for some admissions and short hospital stays. The 2013 Rand Research Report on the “Evolving Role of Emergency Departments in the United States” (http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR200/RR280/RAND_RR280.pdf) clearly describes the many other things that emergency medicine now encompasses.

If the venerable hourglass no longer depicts all that emergency medicine has become, is it time to freshen the image or adopt a new symbol? One other extremely significant time-related feature of emergency medicine that has endured is the recognition that the hours during which the human body gets sick or injured are not restricted to typical work hours or work days, and that, as the title of Brian Zink’s book suggests, EPs are trained to care for “Anyone, Anything, Anytime” (Anyone, Anything, Anytime: A History of Emergency Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby, Inc; 2006). Perhaps, the time has come to add “24/7” to the hourglass symbol. This suggestion is not as frivolous as it may sound, as increasingly federal and state governments and private insurers are using the availability of care 24 hours a day, 7 days a week as a principal characteristic that differentiates emergency medicine, and the higher reimbursement rates it commands, from the care provided by urgent care and “convenient care” centers.

In April 1977, shortly after the new American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM) was constituted, it adopted the hourglass as its symbol for the unique nature of emergency medicine—a specialty in large part defined by the very brief time in which emergency physicians (EPs) must correctly identify and treat serious, life-threatening conditions. Incorporating the concept of the “golden hour” in which to prevent the irreversible consequences of serious trauma, and the frequently even shorter period to effectively intervene after cardiovascular and neurovascular catastrophes, the hourglass has become a powerful symbol that all emergency physicians are very, very proud of.

In the years since the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) recognized Emergency Medicine as the 23rd specialty, though much about emergency medicine has remained the same, much has also changed. Currently, the time patients spend in EDs throughout the country is all too frequently determined, not by the time required to diagnose and initiate treatment for their illnesses, but by the time required for an inpatient bed to become available or for safe, reliable outpatient care to be arranged. In some hospitals, ED patients who are admitted and require inpatient care or “observation services” continue to be cared for by EPs and ED nurses, while in other hospitals the care and responsibility for such patients is transferred to the appropriate inpatient service—even as the patients remain for hours or days on ED stretchers on the ground floor of the hospital. In some cases, an entire “hospitalization” takes place in the ED.

Similarly, when the specialty of emergency medicine was first established, it faced not only time, but resource-limitations as well. Few CT scanners then were commonly available in close proximity to EDs; afterward, when CT scans did become easily accessible to ED patients and MRI scanners began to appear, no one considered MRI scans to be “ED procedures” because of the time required to complete the studies. This, of course, was before managed-care appeared on the scene and, more recently, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) began to seriously question the need for some admissions and short hospital stays. The 2013 Rand Research Report on the “Evolving Role of Emergency Departments in the United States” (http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR200/RR280/RAND_RR280.pdf) clearly describes the many other things that emergency medicine now encompasses.

If the venerable hourglass no longer depicts all that emergency medicine has become, is it time to freshen the image or adopt a new symbol? One other extremely significant time-related feature of emergency medicine that has endured is the recognition that the hours during which the human body gets sick or injured are not restricted to typical work hours or work days, and that, as the title of Brian Zink’s book suggests, EPs are trained to care for “Anyone, Anything, Anytime” (Anyone, Anything, Anytime: A History of Emergency Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby, Inc; 2006). Perhaps, the time has come to add “24/7” to the hourglass symbol. This suggestion is not as frivolous as it may sound, as increasingly federal and state governments and private insurers are using the availability of care 24 hours a day, 7 days a week as a principal characteristic that differentiates emergency medicine, and the higher reimbursement rates it commands, from the care provided by urgent care and “convenient care” centers.

In April 1977, shortly after the new American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM) was constituted, it adopted the hourglass as its symbol for the unique nature of emergency medicine—a specialty in large part defined by the very brief time in which emergency physicians (EPs) must correctly identify and treat serious, life-threatening conditions. Incorporating the concept of the “golden hour” in which to prevent the irreversible consequences of serious trauma, and the frequently even shorter period to effectively intervene after cardiovascular and neurovascular catastrophes, the hourglass has become a powerful symbol that all emergency physicians are very, very proud of.

In the years since the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) recognized Emergency Medicine as the 23rd specialty, though much about emergency medicine has remained the same, much has also changed. Currently, the time patients spend in EDs throughout the country is all too frequently determined, not by the time required to diagnose and initiate treatment for their illnesses, but by the time required for an inpatient bed to become available or for safe, reliable outpatient care to be arranged. In some hospitals, ED patients who are admitted and require inpatient care or “observation services” continue to be cared for by EPs and ED nurses, while in other hospitals the care and responsibility for such patients is transferred to the appropriate inpatient service—even as the patients remain for hours or days on ED stretchers on the ground floor of the hospital. In some cases, an entire “hospitalization” takes place in the ED.

Similarly, when the specialty of emergency medicine was first established, it faced not only time, but resource-limitations as well. Few CT scanners then were commonly available in close proximity to EDs; afterward, when CT scans did become easily accessible to ED patients and MRI scanners began to appear, no one considered MRI scans to be “ED procedures” because of the time required to complete the studies. This, of course, was before managed-care appeared on the scene and, more recently, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) began to seriously question the need for some admissions and short hospital stays. The 2013 Rand Research Report on the “Evolving Role of Emergency Departments in the United States” (http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR200/RR280/RAND_RR280.pdf) clearly describes the many other things that emergency medicine now encompasses.

If the venerable hourglass no longer depicts all that emergency medicine has become, is it time to freshen the image or adopt a new symbol? One other extremely significant time-related feature of emergency medicine that has endured is the recognition that the hours during which the human body gets sick or injured are not restricted to typical work hours or work days, and that, as the title of Brian Zink’s book suggests, EPs are trained to care for “Anyone, Anything, Anytime” (Anyone, Anything, Anytime: A History of Emergency Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby, Inc; 2006). Perhaps, the time has come to add “24/7” to the hourglass symbol. This suggestion is not as frivolous as it may sound, as increasingly federal and state governments and private insurers are using the availability of care 24 hours a day, 7 days a week as a principal characteristic that differentiates emergency medicine, and the higher reimbursement rates it commands, from the care provided by urgent care and “convenient care” centers.

A National Disgrace--Drug Shortages Continue

[Updating an editorial that first appeared in the August 2012 issue.]

Until recently, shortages of critically needed medications in this country were rare and unthinkable. But now, the unthinkable has become commonplace. In August 2012, I wrote about the seemingly endless supply problems and proposed some possible remedies, but in the 3 years since, not much has changed.

Cold War era images of empty Soviet Russia supermarket shelves still remain vivid reminders of a failed system of government. So, who would have predicted that in the 21st century, the United States of America, winner of the Cold War, would have hospital pharmacy shelves bereft of essential medications, including many of the sterile, injectable, crashcart meds we rely on during resuscitations? According to a November 2011 U.S. Government Accountability Office report (GAO-12-116), there were 1,190 drug shortages between 2001-2011 with the number increasing annually since 2006. Drug shortages have not escaped physician or public attention, and a lot of finger pointing among government agencies, manufacturers, and distributors, have made most of us feel like a parent trying to break up a loud argument between siblings: “I don’t care who started it, just stop it NOW!”

One of the most critical types of shortages involves sterile, injectable, generic meds (such as epinephrine), accounting for more than half the shortages since 2009. During resuscitations, physicians and paramedics rely on the immediate availability of premixed, ready-to-use unit doses packaged in sealed, prefilled syringes. All such preparations must be sterile and most are generic, necessitating short expiration dates and tightly controlled inventories to maintain sterility of properly produced preparations, while contamination during the manufacturing process itself results in nationwide recalls and production halts. Because these generic medications have no patent protection and do not command the higher prices of newer, brand-name drugs, there is little incentive for manufacturers to make costly changes in production methods aimed at reducing future shortages. As noted in an August 2010 NEJM article on a shortage of propofol (2010;363[9]:806-807), most such drugs are manufactured by only two or three companies Should a manufacturer suspend or discontinue production, widespread shortages are felt immediately. Although the FDA has the authority to regulate pharmaceutical production to ensure safety, it cannot mandate continued production.

Relying on information from the Utah Drug Information Service, the GAO (http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-14-194) found that the total number of shortages increased each year since 2007, even in years (2012, 2013) when the rate of new shortages decreased, because ongoing shortages were slow to resolve. Disturbingly, current shortages include such basics as saline, dextrose, nitroglycerin, anti-emetics, and epinephrine packaged for use in resuscitations, all affecting large numbers of patients. Manufacturer-provided information to the Utah Drug Information Service (http://www.ashp.org/DocLibrary/Policy/DrugShortages/Drug-Shortages-Statistics.pdf) regarding the reasons for shortages in 2014 indicate “manufacturing problems” were responsible for 25%, “supply/demand” for 17%, “business decisions/ discontinue” for 9%, with 47% listed as “unknown.”

What can be done to avoid shortages? First, a short list of “never event” drug shortages should be identified. For established medications and formulations too essential to be allowed to fail, the federal government should consider relaxing or delaying requirements for new, costly changes in their manufacture, or should pay for the mandated changes. The government should also consider offering incentives for pharmaceutical companies to continue producing critically-needed, low-profit generics that require costly manufacturing changes, perhaps by extending patent protection for one of the company’s more profitable products. As a last resort, the government should consider manufacturing the medication itself.

In the almost 15 years since an Annals of Emergency Medicine article appeared on “the challenge of drug shortages for emergency medicine” (2002;40[8]:598-602),—enough time for three Soviet-style “5 year plans”—new shortages and their deleterious effects on patient care have continued.

[Updating an editorial that first appeared in the August 2012 issue.]

Until recently, shortages of critically needed medications in this country were rare and unthinkable. But now, the unthinkable has become commonplace. In August 2012, I wrote about the seemingly endless supply problems and proposed some possible remedies, but in the 3 years since, not much has changed.

Cold War era images of empty Soviet Russia supermarket shelves still remain vivid reminders of a failed system of government. So, who would have predicted that in the 21st century, the United States of America, winner of the Cold War, would have hospital pharmacy shelves bereft of essential medications, including many of the sterile, injectable, crashcart meds we rely on during resuscitations? According to a November 2011 U.S. Government Accountability Office report (GAO-12-116), there were 1,190 drug shortages between 2001-2011 with the number increasing annually since 2006. Drug shortages have not escaped physician or public attention, and a lot of finger pointing among government agencies, manufacturers, and distributors, have made most of us feel like a parent trying to break up a loud argument between siblings: “I don’t care who started it, just stop it NOW!”

One of the most critical types of shortages involves sterile, injectable, generic meds (such as epinephrine), accounting for more than half the shortages since 2009. During resuscitations, physicians and paramedics rely on the immediate availability of premixed, ready-to-use unit doses packaged in sealed, prefilled syringes. All such preparations must be sterile and most are generic, necessitating short expiration dates and tightly controlled inventories to maintain sterility of properly produced preparations, while contamination during the manufacturing process itself results in nationwide recalls and production halts. Because these generic medications have no patent protection and do not command the higher prices of newer, brand-name drugs, there is little incentive for manufacturers to make costly changes in production methods aimed at reducing future shortages. As noted in an August 2010 NEJM article on a shortage of propofol (2010;363[9]:806-807), most such drugs are manufactured by only two or three companies Should a manufacturer suspend or discontinue production, widespread shortages are felt immediately. Although the FDA has the authority to regulate pharmaceutical production to ensure safety, it cannot mandate continued production.

Relying on information from the Utah Drug Information Service, the GAO (http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-14-194) found that the total number of shortages increased each year since 2007, even in years (2012, 2013) when the rate of new shortages decreased, because ongoing shortages were slow to resolve. Disturbingly, current shortages include such basics as saline, dextrose, nitroglycerin, anti-emetics, and epinephrine packaged for use in resuscitations, all affecting large numbers of patients. Manufacturer-provided information to the Utah Drug Information Service (http://www.ashp.org/DocLibrary/Policy/DrugShortages/Drug-Shortages-Statistics.pdf) regarding the reasons for shortages in 2014 indicate “manufacturing problems” were responsible for 25%, “supply/demand” for 17%, “business decisions/ discontinue” for 9%, with 47% listed as “unknown.”

What can be done to avoid shortages? First, a short list of “never event” drug shortages should be identified. For established medications and formulations too essential to be allowed to fail, the federal government should consider relaxing or delaying requirements for new, costly changes in their manufacture, or should pay for the mandated changes. The government should also consider offering incentives for pharmaceutical companies to continue producing critically-needed, low-profit generics that require costly manufacturing changes, perhaps by extending patent protection for one of the company’s more profitable products. As a last resort, the government should consider manufacturing the medication itself.

In the almost 15 years since an Annals of Emergency Medicine article appeared on “the challenge of drug shortages for emergency medicine” (2002;40[8]:598-602),—enough time for three Soviet-style “5 year plans”—new shortages and their deleterious effects on patient care have continued.

[Updating an editorial that first appeared in the August 2012 issue.]

Until recently, shortages of critically needed medications in this country were rare and unthinkable. But now, the unthinkable has become commonplace. In August 2012, I wrote about the seemingly endless supply problems and proposed some possible remedies, but in the 3 years since, not much has changed.

Cold War era images of empty Soviet Russia supermarket shelves still remain vivid reminders of a failed system of government. So, who would have predicted that in the 21st century, the United States of America, winner of the Cold War, would have hospital pharmacy shelves bereft of essential medications, including many of the sterile, injectable, crashcart meds we rely on during resuscitations? According to a November 2011 U.S. Government Accountability Office report (GAO-12-116), there were 1,190 drug shortages between 2001-2011 with the number increasing annually since 2006. Drug shortages have not escaped physician or public attention, and a lot of finger pointing among government agencies, manufacturers, and distributors, have made most of us feel like a parent trying to break up a loud argument between siblings: “I don’t care who started it, just stop it NOW!”

One of the most critical types of shortages involves sterile, injectable, generic meds (such as epinephrine), accounting for more than half the shortages since 2009. During resuscitations, physicians and paramedics rely on the immediate availability of premixed, ready-to-use unit doses packaged in sealed, prefilled syringes. All such preparations must be sterile and most are generic, necessitating short expiration dates and tightly controlled inventories to maintain sterility of properly produced preparations, while contamination during the manufacturing process itself results in nationwide recalls and production halts. Because these generic medications have no patent protection and do not command the higher prices of newer, brand-name drugs, there is little incentive for manufacturers to make costly changes in production methods aimed at reducing future shortages. As noted in an August 2010 NEJM article on a shortage of propofol (2010;363[9]:806-807), most such drugs are manufactured by only two or three companies Should a manufacturer suspend or discontinue production, widespread shortages are felt immediately. Although the FDA has the authority to regulate pharmaceutical production to ensure safety, it cannot mandate continued production.

Relying on information from the Utah Drug Information Service, the GAO (http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-14-194) found that the total number of shortages increased each year since 2007, even in years (2012, 2013) when the rate of new shortages decreased, because ongoing shortages were slow to resolve. Disturbingly, current shortages include such basics as saline, dextrose, nitroglycerin, anti-emetics, and epinephrine packaged for use in resuscitations, all affecting large numbers of patients. Manufacturer-provided information to the Utah Drug Information Service (http://www.ashp.org/DocLibrary/Policy/DrugShortages/Drug-Shortages-Statistics.pdf) regarding the reasons for shortages in 2014 indicate “manufacturing problems” were responsible for 25%, “supply/demand” for 17%, “business decisions/ discontinue” for 9%, with 47% listed as “unknown.”

What can be done to avoid shortages? First, a short list of “never event” drug shortages should be identified. For established medications and formulations too essential to be allowed to fail, the federal government should consider relaxing or delaying requirements for new, costly changes in their manufacture, or should pay for the mandated changes. The government should also consider offering incentives for pharmaceutical companies to continue producing critically-needed, low-profit generics that require costly manufacturing changes, perhaps by extending patent protection for one of the company’s more profitable products. As a last resort, the government should consider manufacturing the medication itself.

In the almost 15 years since an Annals of Emergency Medicine article appeared on “the challenge of drug shortages for emergency medicine” (2002;40[8]:598-602),—enough time for three Soviet-style “5 year plans”—new shortages and their deleterious effects on patient care have continued.

Broadside Journalism

In a May 2, 2015 editorial “Stroke of Fate,” respected Times columnist Maureen Dowd wrote about her niece’s experience after suffering a vertebral artery dissection that had been “diagnosed correctly and acted on in the ED,” according to a subsequent letter written by neurologist Louis R. Caplan, MD, who was quoted extensively in the column. Noting that the incidence of strokes has been rising among younger adults, the column took issue with the advice of doctors who told her niece to cut back on physical activity. Dr Caplan was consulted for a second opinion and determined that the imaging studies had been misinterpreted and that the vertebral artery had only narrowed, not closed, allowing the patient to resume her active lifestyle.

Though the column did not specify which doctors had misinterpreted the studies or who had given the unnecessarily restrictive advice, it is difficult to imagine that EPs were responsible for either. Nevertheless, Dr Caplan was subsequently quoted as saying that “stroke experts have had a hard time getting the message across to ER personnel that if a stroke is suspected, a vascular image must be taken as well as a brain image” and that going to an “ER” because of a neurological problem is similar to “run[ning] your Rolls-Royce into the local gas station.” He also said that he is afraid to go to the “emergency room” because he thinks it’s dangerous, and that patients have to “worry about the quality of treatment” there.

In a letter to emergency medicine colleagues after the column appeared, Dr Caplan apologized for quotes taken out of context, and wrote “feel free to convey…to your colleagues” that he did not mean to throw stones at EPs, but wanted to point out that undue limitations on activities can become more disabling than the stroke itself and that system issues, such as long waits and lack of access to past records, not the competency of EPs, made patients afraid. He added that he did “not think being in an ED is dangerous, but is frightening to many patients.”

Clearly, we can all agree on the need for vascular as well as other types of imaging for certain stroke presentations, and that statements in the column were not intended to be understood exactly as written— though to date, no clarifications have since appeared in the column or newspaper. But when such criticism appears in a powerful, respected, and widely disseminated media source, it is almost impossible to undo whatever damage may have been done to public perceptions of ED safety and quality of care. Although many EPs have read or learned of the subsequent clarifying letter, few nonphysicians will ever see or appreciate the disclaimers and clarifications.

To avoid such unfortunate situations in the future, all physicians must be very, very careful in framing statements to the media, and should assume that their remarks will not be placed “in context,” or nuanced as they intended. Most important, is to not disparage entire specialties or use slang terms such as “ER docs” to indicate lesser expertise than one’s own specialty. Doing so can only unnecessarily heighten patients’ fears.

In a May 2, 2015 editorial “Stroke of Fate,” respected Times columnist Maureen Dowd wrote about her niece’s experience after suffering a vertebral artery dissection that had been “diagnosed correctly and acted on in the ED,” according to a subsequent letter written by neurologist Louis R. Caplan, MD, who was quoted extensively in the column. Noting that the incidence of strokes has been rising among younger adults, the column took issue with the advice of doctors who told her niece to cut back on physical activity. Dr Caplan was consulted for a second opinion and determined that the imaging studies had been misinterpreted and that the vertebral artery had only narrowed, not closed, allowing the patient to resume her active lifestyle.

Though the column did not specify which doctors had misinterpreted the studies or who had given the unnecessarily restrictive advice, it is difficult to imagine that EPs were responsible for either. Nevertheless, Dr Caplan was subsequently quoted as saying that “stroke experts have had a hard time getting the message across to ER personnel that if a stroke is suspected, a vascular image must be taken as well as a brain image” and that going to an “ER” because of a neurological problem is similar to “run[ning] your Rolls-Royce into the local gas station.” He also said that he is afraid to go to the “emergency room” because he thinks it’s dangerous, and that patients have to “worry about the quality of treatment” there.

In a letter to emergency medicine colleagues after the column appeared, Dr Caplan apologized for quotes taken out of context, and wrote “feel free to convey…to your colleagues” that he did not mean to throw stones at EPs, but wanted to point out that undue limitations on activities can become more disabling than the stroke itself and that system issues, such as long waits and lack of access to past records, not the competency of EPs, made patients afraid. He added that he did “not think being in an ED is dangerous, but is frightening to many patients.”

Clearly, we can all agree on the need for vascular as well as other types of imaging for certain stroke presentations, and that statements in the column were not intended to be understood exactly as written— though to date, no clarifications have since appeared in the column or newspaper. But when such criticism appears in a powerful, respected, and widely disseminated media source, it is almost impossible to undo whatever damage may have been done to public perceptions of ED safety and quality of care. Although many EPs have read or learned of the subsequent clarifying letter, few nonphysicians will ever see or appreciate the disclaimers and clarifications.

To avoid such unfortunate situations in the future, all physicians must be very, very careful in framing statements to the media, and should assume that their remarks will not be placed “in context,” or nuanced as they intended. Most important, is to not disparage entire specialties or use slang terms such as “ER docs” to indicate lesser expertise than one’s own specialty. Doing so can only unnecessarily heighten patients’ fears.