User login

Active Robotics for Total Hip Arthroplasty

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is a successful surgery with positive clinical outcomes and over 95% survivorship at 10-year follow-up and 80% survivorship at 25-year follow-up.1,2 A hip replacement requires strong osteointegration3,4 to prevent femoral osteolysis, and correct implant alignment has been shown to correlate with prolonged implant survivorship and reduced dislocation.5,6 Robotics and computer-assisted navigation have been developed to increase the accuracy of implant placement and reduce outliers with the overall goal of improving long-term results. These technologies have shown significant improvements in implant positioning when compared to conventional techniques.7

The first active robotic system for use in orthopedic procedures, Robodoc (Think Surgical, Inc.), was based on a traditional computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing system. Currently, only 3 robotic systems for THA have clearance in the US: The Mako System (Stryker), Robodoc, and TSolution One (Think Surgical, Inc.). The TSolution One system is based on the legacy technology developed as Robodoc and currently provides assistance during preparation of the femoral canal as well as guidance and positioning assistance during acetabular cup reaming and implanting. The following is a summary of the author’s (DSD) preferred technique for robotic-assisted THA using TSolution One.

How It Works

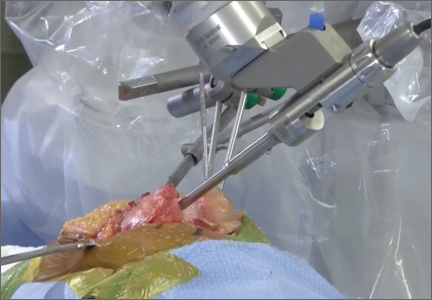

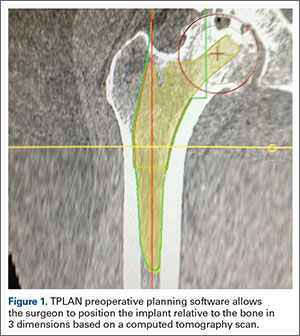

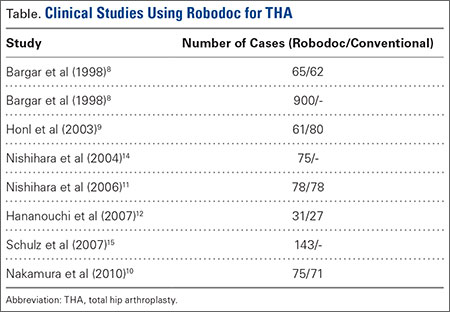

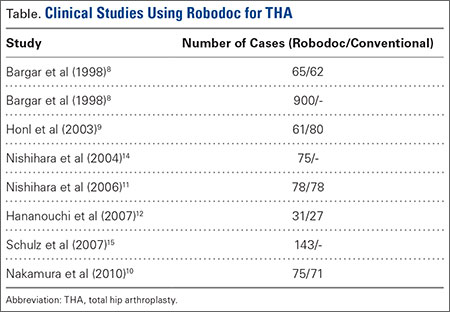

The process begins with preoperative planning (Figure 1). A computed tomography (CT) scan is used to create a detailed 3-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of the patient’s pathologic hip anatomy. The CT scan images are uploaded to TPLAN, a preoperative planning station.

In TPLAN, the user creates a 3D template of the surgical plan for both the femoral and acetabular portions of the procedure. The system has an open platform, meaning that the user is not limited to a single implant design or manufacturer. The surgeon can control every aspect of implant positioning: rotation, anteversion, fit and fill on the femoral side and anteversion, inclination/lateral opening, and depth on the acetabular side. Additional features available to the surgeon include accurately defining bony deficits, identifying outlier implant sizes, and checking for excess native version. The system allows the surgeon to determine the native center of hip rotation, which can then be used during templating to give the patient a hip that feels natural because the native muscle tension is restored. Once the desired plan has been achieved, it is uploaded to the robot.The TCAT robot is an active system similar to those used in manufacturing assembly plants (eg, automobiles) in that it follows a predetermined path and can do so in an efficient manner. More specifically, once the user has defined the patient’s anatomy within its workspace, it will proceed with actively milling the femur as planned with sub-millimeter accuracy without the use of navigation. This is in contrast to a haptic system, where the user manually guides the robotic arm within a predefined boundary.

The acetabular portion of the procedure currently uses a standard reamer system and power tools, but the TCAT guides the surgeon to the planned cup orientation, which is maintained during reaming and impaction.

In the Operating Suite

Once in the operating suite, the plan is uploaded into TCAT. Confirmation of the plan and the patient are incorporated into the surgical “time out.” Currently, the system supports patient positioning in standard lateral decubitus using a posterior approach with a standard operating room table. A posterior approach is undertaken to expose and dislocate the hip, with retractors placed to protect the soft tissues and allow the robot its working space.

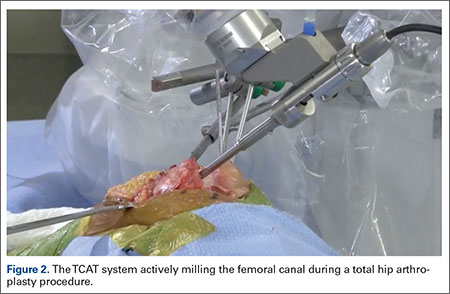

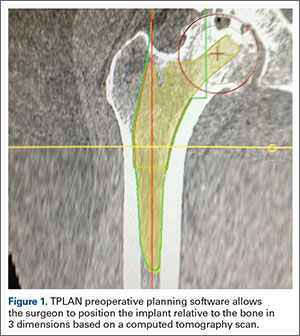

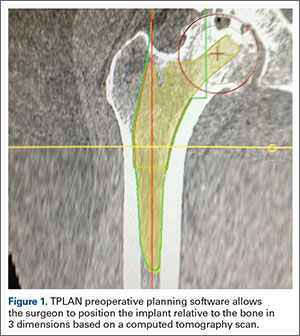

One procedural difference from the standard THA technique is that the femoral head is initially retained to fixate the femur relative to the robot. A 5-mm Schanz pin is placed in the femoral head and then rigidly attached to the base of the robot. During a process called registration, a series of points on the surface of the exposed bone are collected by the surgeon via a digitizer probe attached to the robot. The TCAT monitor will guide the surgeon through point collection using a map showing the patient’s 3D bone model generated from the CT scan. The software then “finds” the patient’s femur in space and matches it to the 3D CT plan. Milling begins with a burr spinning at 80,000 rpm and saline to irrigate and remove bone debris (Figure 2). The actual milling process takes 5 to 15 minutes, depending on the choice and size of the implant.

A bone motion monitor (BMM) is also attached to the femur, along with recovery markers (RM). The BMM immediately pauses the robot during any active bone milling if it senses femoral motion from the original position. The surgeon then touches the RM with the digitizer to re-register the bone’s position and resume the milling process.

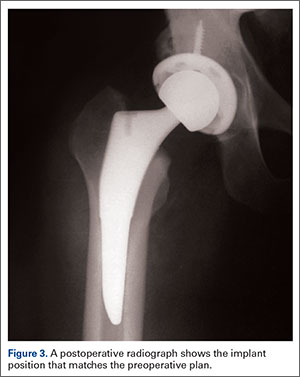

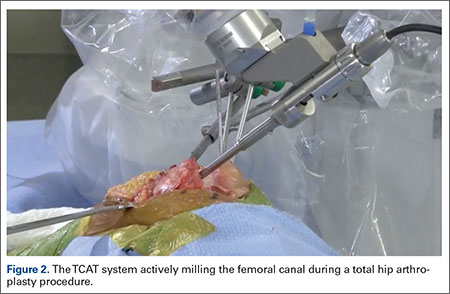

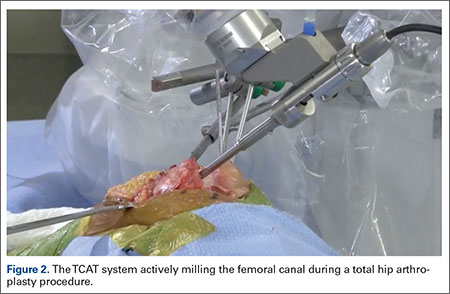

Attention is then turned to the acetabular portion of the procedure. Again, the robot must be rigidly fixed to the patient’s pelvis, along with the RM. Once the surgeon has registered the acetabular position using the digitizer, the robotic arm moves into the preoperatively planned orientation. A universal quick-release allows the surgeon to attach a standard reamer to the robot arm and ream while the robot holds the reamer in place. Once the acetabular preparation is complete, the cup impactor is placed onto the robotic arm and the implant is impacted into the patient. Thereafter, the digitizer can be used to collect points on the surface of the cup and confirm the exact cup placement (Figure 3).

Outcomes

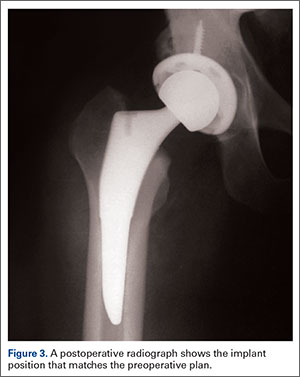

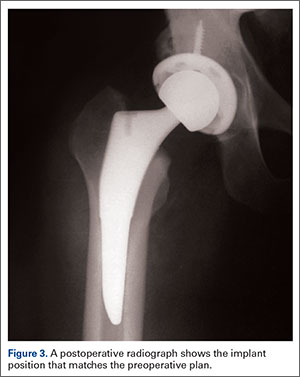

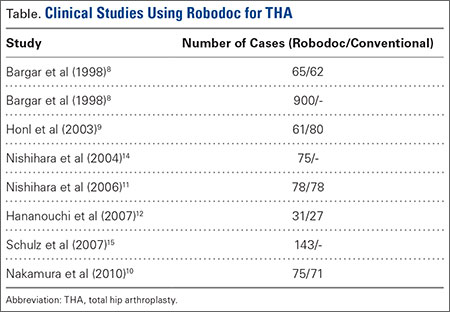

The legacy system, Robodoc, has been used in thousands of clinical cases for both THA and total knee arthroplasty. The Table represents a summary of the THA clinical studies during a time frame in which only the femoral portion of the procedure was available to surgeons.

Bargar and colleagues8 describe the first Robodoc clinical trial in the US, along with the first 900 THA procedures performed in Germany. In the US, researchers conducted a prospective, randomized control study with 65 robotic cases and 62 conventional control cases. In terms of functional outcomes, there were no differences between the 2 groups. The robot group had improved radiographic fit and component positioning but significantly increased surgical time and blood loss. There were no femoral fractures in the robot group but 3 cases in the control group. In Germany, they reported on 870 primary THAs and 30 revision THA cases. For the primary cases, Harris hip scores rose from 43.7 preoperatively to 91.5 postoperatively. Complication rates were similar to conventional techniques, except the robot cases had no intraoperative femoral fractures.

Several prospective randomized clinical studies compared use of the Robodoc system with a conventional technique. The group studied by Honl and colleagues9 included 61 robotic cases and 80 conventional cases. The robot group had significant improvements in limb-length equality and varus-valgus orientation of the stem. When the revision cases were excluded, the authors found the Harris hip scores, prosthetic alignment, and limb length differentials were better for the robotic group at both 6 and 12 months.

Nakamura and colleagues10 looked at 75 robotic cases and 71 conventional cases. The results showed that at 2 and 3 years postoperatively, the robotic group had better Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) scores, but by 5 years postoperatively, the differences were no longer significant. The robotic group had a smaller range for leg length inequality (0-12 mm) compared to the conventional group (0-29 mm). The results also showed that at both 2 and 5 years postoperatively, there was more significant stress shielding of the proximal femur, suggesting greater bone loss in the conventional group.

Nishihara and colleagues11 had 78 subjects in each of the robotic and conventional groups and found significantly better Merle d’Aubigné hip scores at 2 years postoperatively in the robotic group. The conventional group suffered 5 intraoperative fractures compared with none in the robotic group, along with greater estimated blood loss, an increased use of undersized stems, higher-than-expected vertical seating, and unexpected femoral anteversion. The robotic cases did, however, take 19 minutes longer than the conventional cases.

Hananouchi and colleagues12 looked at periprosthetic bone remodeling in 31 robotic hips and 27 conventional hips to determine whether load was effectively transferred from implant to bone after using the Robodoc system to prepare the femoral canal. Using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) to measure bone density, they found significantly less bone loss in the proximal periprosthetic areas in the robotic group compared to the conventional group; however, there were no differences in the Merle d’Aubigné hip scores.

Lim and colleagues13 looked specifically at alignment accuracy and clinical outcomes specifically for short femoral stem implants. In a group of 24 robotic cases and 25 conventional cases, they found significantly improved stem alignment and leg length inequality and no differences in Harris Hip score, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) score, or complications at 24 months.

In 2004, Nishihara and colleagues14 evaluated the accuracy of femoral canal preparation using postoperative CT images for 75 cases of THA performed with the original pin-based version of Robodoc. The results showed that the differences between the preoperative plan and the postoperative CT were <5% in terms of canal fill, <1 mm in gap, and <1° in mediolateral and anteroposterior alignment with no reported fractures or complications. They concluded that the Robodoc system resulted in a high degree of accuracy.

Schulz and colleagues15 reported on 97 of 143 consecutive cases performed from 1997 to 2002. Technical complications were described in 9 cases. Five of the reported complications included the BMM pausing cutting as designed for patient safety, which led to re-registration, and slightly prolonged surgery. The remaining 4 complications included 2 femoral shaft fissures requiring wire cerclage, 1 case of damage to the acetabular rim from the milling device, and 1 defect of the greater trochanter that was milled. In terms of clinical results, they found that the complications, functional outcomes, and radiographic outcomes were comparable to conventional techniques. The rate of femoral shaft fissures, which had been zero in all other studies with Robodoc, was comparable to conventional technique.

Conclusion

The most significant change in hip arthroplasty until now has been the transition from a cemented technique to a press-fit or ingrowth prosthesis.16 The first robotic surgery was performed in the US in 1992 using the legacy system upon which the current TSolution One was based. Since then, the use of surgical robots has seen a 30% increase annually over the last decade in a variety of surgical fields.17 In orthopedics, specifically THA, the results have shown that robotics clearly offers benefits in terms of accuracy, precision, and reproducibility. These benefits will likely translate into improved long-term outcomes and increased survivorship in future studies.

1. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780-785.

2. National Joint Registry. National Joint Registry for England and Wales. 7th annual report. Available at: http://www.njrcentre.org.uk/njrcentre/portals/0/njr%207th%20annual%20report%202010.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2016.

3. Paul HA, Bargar WL, Mittlestadt B, et al. Development of a surgical robot for cementless total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;285:57-66.

4. Bobyn JD, Engh CA. Human histology of bone-porous metal implant interface. Orthopedics. 1984;7(9):1410.

5. Barrack RL. Dislocation after total hip arthroplasty: Implant design and orientation. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003;11(2):89-99.

6. Miki H, Sugano N, Yonenobu K, Tsuda K, Hattori M, Suzuki N. Detecting cause of dislocation after total hip arthroplasty by patient-specific four-dimensional motion analysis. Clin Biomech. 2013;28(2):182-186.

7. Sugano N. Computer-assisted orthopaedic surgery and robotic surgery in total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Surg. 2013;5(1):1-9.

8. Bargar WL, Bauer A, Börner M. Primary and revision total hip replacement using the Robodoc system. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1998;354:82-91.

9. Honl M, Dierk O, Gauck C, et al. Comparison of robotic-assisted and manual implantation of primary total hip replacement: a prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(8):1470-1478.

10. Nakamura N, Sugano N, Nishii T, Kakimoto A, Miki H. A comparison between robotic-assisted and manual implantation of cementless total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(4):1072-1081.

11. Nishihara S, Sugano N, Nishii T, Miki H, Nakamura N, Yoshikawa H. Comparison between hand rasping and robotic milling for stem implantation in cementless total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(7):957-966.

12. Hananouchi T, Sugano N, Nishii T, et al. Effect of robotic milling on periprosthetic bone remodeling. J Orthop Res. 2007;25(8):1062-1069.

13. Lim SJ, Ko KR, Park CW, Moon YW, Park YS. Robot-assisted primary cementless total hip arthroplasty with a short femoral stem: a prospective randomized short-term outcome study. Comput Aided Surg. 2015;20(1):41-46.

14. Nishihara S, Sugano N, Nishii T, et al. Clinical accuracy evaluation of femoral canal preparation using the ROBODOC system. J Orthop Sci. 2004;9(5):452-461.

15. Schulz AP, Seide K, Queitsch C, et al. Results of total hip replacement using the Robodoc surgical assistant system: clinical outcome and evaluation of complications for 97 procedures. Int J Med Robot. 2007;3(4):301-306.

16. Wyatt M, Hooper G, Framptom C, Rothwell A. Survival outcomes of cemented compared to uncemented stems in primary total hip replacement. World J Orthop. 2014;5(5):591-596.

17. Howard B. Is robotic surgery right for you? AARP The Magazine. December 2013/January 2014. Available at: http://www.aarp.org/health/conditions-treatments/info-12-2013/robotic-surgery-risks-benefits.html. Accessed April 12, 2016.

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is a successful surgery with positive clinical outcomes and over 95% survivorship at 10-year follow-up and 80% survivorship at 25-year follow-up.1,2 A hip replacement requires strong osteointegration3,4 to prevent femoral osteolysis, and correct implant alignment has been shown to correlate with prolonged implant survivorship and reduced dislocation.5,6 Robotics and computer-assisted navigation have been developed to increase the accuracy of implant placement and reduce outliers with the overall goal of improving long-term results. These technologies have shown significant improvements in implant positioning when compared to conventional techniques.7

The first active robotic system for use in orthopedic procedures, Robodoc (Think Surgical, Inc.), was based on a traditional computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing system. Currently, only 3 robotic systems for THA have clearance in the US: The Mako System (Stryker), Robodoc, and TSolution One (Think Surgical, Inc.). The TSolution One system is based on the legacy technology developed as Robodoc and currently provides assistance during preparation of the femoral canal as well as guidance and positioning assistance during acetabular cup reaming and implanting. The following is a summary of the author’s (DSD) preferred technique for robotic-assisted THA using TSolution One.

How It Works

The process begins with preoperative planning (Figure 1). A computed tomography (CT) scan is used to create a detailed 3-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of the patient’s pathologic hip anatomy. The CT scan images are uploaded to TPLAN, a preoperative planning station.

In TPLAN, the user creates a 3D template of the surgical plan for both the femoral and acetabular portions of the procedure. The system has an open platform, meaning that the user is not limited to a single implant design or manufacturer. The surgeon can control every aspect of implant positioning: rotation, anteversion, fit and fill on the femoral side and anteversion, inclination/lateral opening, and depth on the acetabular side. Additional features available to the surgeon include accurately defining bony deficits, identifying outlier implant sizes, and checking for excess native version. The system allows the surgeon to determine the native center of hip rotation, which can then be used during templating to give the patient a hip that feels natural because the native muscle tension is restored. Once the desired plan has been achieved, it is uploaded to the robot.The TCAT robot is an active system similar to those used in manufacturing assembly plants (eg, automobiles) in that it follows a predetermined path and can do so in an efficient manner. More specifically, once the user has defined the patient’s anatomy within its workspace, it will proceed with actively milling the femur as planned with sub-millimeter accuracy without the use of navigation. This is in contrast to a haptic system, where the user manually guides the robotic arm within a predefined boundary.

The acetabular portion of the procedure currently uses a standard reamer system and power tools, but the TCAT guides the surgeon to the planned cup orientation, which is maintained during reaming and impaction.

In the Operating Suite

Once in the operating suite, the plan is uploaded into TCAT. Confirmation of the plan and the patient are incorporated into the surgical “time out.” Currently, the system supports patient positioning in standard lateral decubitus using a posterior approach with a standard operating room table. A posterior approach is undertaken to expose and dislocate the hip, with retractors placed to protect the soft tissues and allow the robot its working space.

One procedural difference from the standard THA technique is that the femoral head is initially retained to fixate the femur relative to the robot. A 5-mm Schanz pin is placed in the femoral head and then rigidly attached to the base of the robot. During a process called registration, a series of points on the surface of the exposed bone are collected by the surgeon via a digitizer probe attached to the robot. The TCAT monitor will guide the surgeon through point collection using a map showing the patient’s 3D bone model generated from the CT scan. The software then “finds” the patient’s femur in space and matches it to the 3D CT plan. Milling begins with a burr spinning at 80,000 rpm and saline to irrigate and remove bone debris (Figure 2). The actual milling process takes 5 to 15 minutes, depending on the choice and size of the implant.

A bone motion monitor (BMM) is also attached to the femur, along with recovery markers (RM). The BMM immediately pauses the robot during any active bone milling if it senses femoral motion from the original position. The surgeon then touches the RM with the digitizer to re-register the bone’s position and resume the milling process.

Attention is then turned to the acetabular portion of the procedure. Again, the robot must be rigidly fixed to the patient’s pelvis, along with the RM. Once the surgeon has registered the acetabular position using the digitizer, the robotic arm moves into the preoperatively planned orientation. A universal quick-release allows the surgeon to attach a standard reamer to the robot arm and ream while the robot holds the reamer in place. Once the acetabular preparation is complete, the cup impactor is placed onto the robotic arm and the implant is impacted into the patient. Thereafter, the digitizer can be used to collect points on the surface of the cup and confirm the exact cup placement (Figure 3).

Outcomes

The legacy system, Robodoc, has been used in thousands of clinical cases for both THA and total knee arthroplasty. The Table represents a summary of the THA clinical studies during a time frame in which only the femoral portion of the procedure was available to surgeons.

Bargar and colleagues8 describe the first Robodoc clinical trial in the US, along with the first 900 THA procedures performed in Germany. In the US, researchers conducted a prospective, randomized control study with 65 robotic cases and 62 conventional control cases. In terms of functional outcomes, there were no differences between the 2 groups. The robot group had improved radiographic fit and component positioning but significantly increased surgical time and blood loss. There were no femoral fractures in the robot group but 3 cases in the control group. In Germany, they reported on 870 primary THAs and 30 revision THA cases. For the primary cases, Harris hip scores rose from 43.7 preoperatively to 91.5 postoperatively. Complication rates were similar to conventional techniques, except the robot cases had no intraoperative femoral fractures.

Several prospective randomized clinical studies compared use of the Robodoc system with a conventional technique. The group studied by Honl and colleagues9 included 61 robotic cases and 80 conventional cases. The robot group had significant improvements in limb-length equality and varus-valgus orientation of the stem. When the revision cases were excluded, the authors found the Harris hip scores, prosthetic alignment, and limb length differentials were better for the robotic group at both 6 and 12 months.

Nakamura and colleagues10 looked at 75 robotic cases and 71 conventional cases. The results showed that at 2 and 3 years postoperatively, the robotic group had better Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) scores, but by 5 years postoperatively, the differences were no longer significant. The robotic group had a smaller range for leg length inequality (0-12 mm) compared to the conventional group (0-29 mm). The results also showed that at both 2 and 5 years postoperatively, there was more significant stress shielding of the proximal femur, suggesting greater bone loss in the conventional group.

Nishihara and colleagues11 had 78 subjects in each of the robotic and conventional groups and found significantly better Merle d’Aubigné hip scores at 2 years postoperatively in the robotic group. The conventional group suffered 5 intraoperative fractures compared with none in the robotic group, along with greater estimated blood loss, an increased use of undersized stems, higher-than-expected vertical seating, and unexpected femoral anteversion. The robotic cases did, however, take 19 minutes longer than the conventional cases.

Hananouchi and colleagues12 looked at periprosthetic bone remodeling in 31 robotic hips and 27 conventional hips to determine whether load was effectively transferred from implant to bone after using the Robodoc system to prepare the femoral canal. Using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) to measure bone density, they found significantly less bone loss in the proximal periprosthetic areas in the robotic group compared to the conventional group; however, there were no differences in the Merle d’Aubigné hip scores.

Lim and colleagues13 looked specifically at alignment accuracy and clinical outcomes specifically for short femoral stem implants. In a group of 24 robotic cases and 25 conventional cases, they found significantly improved stem alignment and leg length inequality and no differences in Harris Hip score, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) score, or complications at 24 months.

In 2004, Nishihara and colleagues14 evaluated the accuracy of femoral canal preparation using postoperative CT images for 75 cases of THA performed with the original pin-based version of Robodoc. The results showed that the differences between the preoperative plan and the postoperative CT were <5% in terms of canal fill, <1 mm in gap, and <1° in mediolateral and anteroposterior alignment with no reported fractures or complications. They concluded that the Robodoc system resulted in a high degree of accuracy.

Schulz and colleagues15 reported on 97 of 143 consecutive cases performed from 1997 to 2002. Technical complications were described in 9 cases. Five of the reported complications included the BMM pausing cutting as designed for patient safety, which led to re-registration, and slightly prolonged surgery. The remaining 4 complications included 2 femoral shaft fissures requiring wire cerclage, 1 case of damage to the acetabular rim from the milling device, and 1 defect of the greater trochanter that was milled. In terms of clinical results, they found that the complications, functional outcomes, and radiographic outcomes were comparable to conventional techniques. The rate of femoral shaft fissures, which had been zero in all other studies with Robodoc, was comparable to conventional technique.

Conclusion

The most significant change in hip arthroplasty until now has been the transition from a cemented technique to a press-fit or ingrowth prosthesis.16 The first robotic surgery was performed in the US in 1992 using the legacy system upon which the current TSolution One was based. Since then, the use of surgical robots has seen a 30% increase annually over the last decade in a variety of surgical fields.17 In orthopedics, specifically THA, the results have shown that robotics clearly offers benefits in terms of accuracy, precision, and reproducibility. These benefits will likely translate into improved long-term outcomes and increased survivorship in future studies.

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is a successful surgery with positive clinical outcomes and over 95% survivorship at 10-year follow-up and 80% survivorship at 25-year follow-up.1,2 A hip replacement requires strong osteointegration3,4 to prevent femoral osteolysis, and correct implant alignment has been shown to correlate with prolonged implant survivorship and reduced dislocation.5,6 Robotics and computer-assisted navigation have been developed to increase the accuracy of implant placement and reduce outliers with the overall goal of improving long-term results. These technologies have shown significant improvements in implant positioning when compared to conventional techniques.7

The first active robotic system for use in orthopedic procedures, Robodoc (Think Surgical, Inc.), was based on a traditional computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing system. Currently, only 3 robotic systems for THA have clearance in the US: The Mako System (Stryker), Robodoc, and TSolution One (Think Surgical, Inc.). The TSolution One system is based on the legacy technology developed as Robodoc and currently provides assistance during preparation of the femoral canal as well as guidance and positioning assistance during acetabular cup reaming and implanting. The following is a summary of the author’s (DSD) preferred technique for robotic-assisted THA using TSolution One.

How It Works

The process begins with preoperative planning (Figure 1). A computed tomography (CT) scan is used to create a detailed 3-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of the patient’s pathologic hip anatomy. The CT scan images are uploaded to TPLAN, a preoperative planning station.

In TPLAN, the user creates a 3D template of the surgical plan for both the femoral and acetabular portions of the procedure. The system has an open platform, meaning that the user is not limited to a single implant design or manufacturer. The surgeon can control every aspect of implant positioning: rotation, anteversion, fit and fill on the femoral side and anteversion, inclination/lateral opening, and depth on the acetabular side. Additional features available to the surgeon include accurately defining bony deficits, identifying outlier implant sizes, and checking for excess native version. The system allows the surgeon to determine the native center of hip rotation, which can then be used during templating to give the patient a hip that feels natural because the native muscle tension is restored. Once the desired plan has been achieved, it is uploaded to the robot.The TCAT robot is an active system similar to those used in manufacturing assembly plants (eg, automobiles) in that it follows a predetermined path and can do so in an efficient manner. More specifically, once the user has defined the patient’s anatomy within its workspace, it will proceed with actively milling the femur as planned with sub-millimeter accuracy without the use of navigation. This is in contrast to a haptic system, where the user manually guides the robotic arm within a predefined boundary.

The acetabular portion of the procedure currently uses a standard reamer system and power tools, but the TCAT guides the surgeon to the planned cup orientation, which is maintained during reaming and impaction.

In the Operating Suite

Once in the operating suite, the plan is uploaded into TCAT. Confirmation of the plan and the patient are incorporated into the surgical “time out.” Currently, the system supports patient positioning in standard lateral decubitus using a posterior approach with a standard operating room table. A posterior approach is undertaken to expose and dislocate the hip, with retractors placed to protect the soft tissues and allow the robot its working space.

One procedural difference from the standard THA technique is that the femoral head is initially retained to fixate the femur relative to the robot. A 5-mm Schanz pin is placed in the femoral head and then rigidly attached to the base of the robot. During a process called registration, a series of points on the surface of the exposed bone are collected by the surgeon via a digitizer probe attached to the robot. The TCAT monitor will guide the surgeon through point collection using a map showing the patient’s 3D bone model generated from the CT scan. The software then “finds” the patient’s femur in space and matches it to the 3D CT plan. Milling begins with a burr spinning at 80,000 rpm and saline to irrigate and remove bone debris (Figure 2). The actual milling process takes 5 to 15 minutes, depending on the choice and size of the implant.

A bone motion monitor (BMM) is also attached to the femur, along with recovery markers (RM). The BMM immediately pauses the robot during any active bone milling if it senses femoral motion from the original position. The surgeon then touches the RM with the digitizer to re-register the bone’s position and resume the milling process.

Attention is then turned to the acetabular portion of the procedure. Again, the robot must be rigidly fixed to the patient’s pelvis, along with the RM. Once the surgeon has registered the acetabular position using the digitizer, the robotic arm moves into the preoperatively planned orientation. A universal quick-release allows the surgeon to attach a standard reamer to the robot arm and ream while the robot holds the reamer in place. Once the acetabular preparation is complete, the cup impactor is placed onto the robotic arm and the implant is impacted into the patient. Thereafter, the digitizer can be used to collect points on the surface of the cup and confirm the exact cup placement (Figure 3).

Outcomes

The legacy system, Robodoc, has been used in thousands of clinical cases for both THA and total knee arthroplasty. The Table represents a summary of the THA clinical studies during a time frame in which only the femoral portion of the procedure was available to surgeons.

Bargar and colleagues8 describe the first Robodoc clinical trial in the US, along with the first 900 THA procedures performed in Germany. In the US, researchers conducted a prospective, randomized control study with 65 robotic cases and 62 conventional control cases. In terms of functional outcomes, there were no differences between the 2 groups. The robot group had improved radiographic fit and component positioning but significantly increased surgical time and blood loss. There were no femoral fractures in the robot group but 3 cases in the control group. In Germany, they reported on 870 primary THAs and 30 revision THA cases. For the primary cases, Harris hip scores rose from 43.7 preoperatively to 91.5 postoperatively. Complication rates were similar to conventional techniques, except the robot cases had no intraoperative femoral fractures.

Several prospective randomized clinical studies compared use of the Robodoc system with a conventional technique. The group studied by Honl and colleagues9 included 61 robotic cases and 80 conventional cases. The robot group had significant improvements in limb-length equality and varus-valgus orientation of the stem. When the revision cases were excluded, the authors found the Harris hip scores, prosthetic alignment, and limb length differentials were better for the robotic group at both 6 and 12 months.

Nakamura and colleagues10 looked at 75 robotic cases and 71 conventional cases. The results showed that at 2 and 3 years postoperatively, the robotic group had better Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) scores, but by 5 years postoperatively, the differences were no longer significant. The robotic group had a smaller range for leg length inequality (0-12 mm) compared to the conventional group (0-29 mm). The results also showed that at both 2 and 5 years postoperatively, there was more significant stress shielding of the proximal femur, suggesting greater bone loss in the conventional group.

Nishihara and colleagues11 had 78 subjects in each of the robotic and conventional groups and found significantly better Merle d’Aubigné hip scores at 2 years postoperatively in the robotic group. The conventional group suffered 5 intraoperative fractures compared with none in the robotic group, along with greater estimated blood loss, an increased use of undersized stems, higher-than-expected vertical seating, and unexpected femoral anteversion. The robotic cases did, however, take 19 minutes longer than the conventional cases.

Hananouchi and colleagues12 looked at periprosthetic bone remodeling in 31 robotic hips and 27 conventional hips to determine whether load was effectively transferred from implant to bone after using the Robodoc system to prepare the femoral canal. Using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) to measure bone density, they found significantly less bone loss in the proximal periprosthetic areas in the robotic group compared to the conventional group; however, there were no differences in the Merle d’Aubigné hip scores.

Lim and colleagues13 looked specifically at alignment accuracy and clinical outcomes specifically for short femoral stem implants. In a group of 24 robotic cases and 25 conventional cases, they found significantly improved stem alignment and leg length inequality and no differences in Harris Hip score, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) score, or complications at 24 months.

In 2004, Nishihara and colleagues14 evaluated the accuracy of femoral canal preparation using postoperative CT images for 75 cases of THA performed with the original pin-based version of Robodoc. The results showed that the differences between the preoperative plan and the postoperative CT were <5% in terms of canal fill, <1 mm in gap, and <1° in mediolateral and anteroposterior alignment with no reported fractures or complications. They concluded that the Robodoc system resulted in a high degree of accuracy.

Schulz and colleagues15 reported on 97 of 143 consecutive cases performed from 1997 to 2002. Technical complications were described in 9 cases. Five of the reported complications included the BMM pausing cutting as designed for patient safety, which led to re-registration, and slightly prolonged surgery. The remaining 4 complications included 2 femoral shaft fissures requiring wire cerclage, 1 case of damage to the acetabular rim from the milling device, and 1 defect of the greater trochanter that was milled. In terms of clinical results, they found that the complications, functional outcomes, and radiographic outcomes were comparable to conventional techniques. The rate of femoral shaft fissures, which had been zero in all other studies with Robodoc, was comparable to conventional technique.

Conclusion

The most significant change in hip arthroplasty until now has been the transition from a cemented technique to a press-fit or ingrowth prosthesis.16 The first robotic surgery was performed in the US in 1992 using the legacy system upon which the current TSolution One was based. Since then, the use of surgical robots has seen a 30% increase annually over the last decade in a variety of surgical fields.17 In orthopedics, specifically THA, the results have shown that robotics clearly offers benefits in terms of accuracy, precision, and reproducibility. These benefits will likely translate into improved long-term outcomes and increased survivorship in future studies.

1. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780-785.

2. National Joint Registry. National Joint Registry for England and Wales. 7th annual report. Available at: http://www.njrcentre.org.uk/njrcentre/portals/0/njr%207th%20annual%20report%202010.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2016.

3. Paul HA, Bargar WL, Mittlestadt B, et al. Development of a surgical robot for cementless total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;285:57-66.

4. Bobyn JD, Engh CA. Human histology of bone-porous metal implant interface. Orthopedics. 1984;7(9):1410.

5. Barrack RL. Dislocation after total hip arthroplasty: Implant design and orientation. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003;11(2):89-99.

6. Miki H, Sugano N, Yonenobu K, Tsuda K, Hattori M, Suzuki N. Detecting cause of dislocation after total hip arthroplasty by patient-specific four-dimensional motion analysis. Clin Biomech. 2013;28(2):182-186.

7. Sugano N. Computer-assisted orthopaedic surgery and robotic surgery in total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Surg. 2013;5(1):1-9.

8. Bargar WL, Bauer A, Börner M. Primary and revision total hip replacement using the Robodoc system. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1998;354:82-91.

9. Honl M, Dierk O, Gauck C, et al. Comparison of robotic-assisted and manual implantation of primary total hip replacement: a prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(8):1470-1478.

10. Nakamura N, Sugano N, Nishii T, Kakimoto A, Miki H. A comparison between robotic-assisted and manual implantation of cementless total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(4):1072-1081.

11. Nishihara S, Sugano N, Nishii T, Miki H, Nakamura N, Yoshikawa H. Comparison between hand rasping and robotic milling for stem implantation in cementless total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(7):957-966.

12. Hananouchi T, Sugano N, Nishii T, et al. Effect of robotic milling on periprosthetic bone remodeling. J Orthop Res. 2007;25(8):1062-1069.

13. Lim SJ, Ko KR, Park CW, Moon YW, Park YS. Robot-assisted primary cementless total hip arthroplasty with a short femoral stem: a prospective randomized short-term outcome study. Comput Aided Surg. 2015;20(1):41-46.

14. Nishihara S, Sugano N, Nishii T, et al. Clinical accuracy evaluation of femoral canal preparation using the ROBODOC system. J Orthop Sci. 2004;9(5):452-461.

15. Schulz AP, Seide K, Queitsch C, et al. Results of total hip replacement using the Robodoc surgical assistant system: clinical outcome and evaluation of complications for 97 procedures. Int J Med Robot. 2007;3(4):301-306.

16. Wyatt M, Hooper G, Framptom C, Rothwell A. Survival outcomes of cemented compared to uncemented stems in primary total hip replacement. World J Orthop. 2014;5(5):591-596.

17. Howard B. Is robotic surgery right for you? AARP The Magazine. December 2013/January 2014. Available at: http://www.aarp.org/health/conditions-treatments/info-12-2013/robotic-surgery-risks-benefits.html. Accessed April 12, 2016.

1. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780-785.

2. National Joint Registry. National Joint Registry for England and Wales. 7th annual report. Available at: http://www.njrcentre.org.uk/njrcentre/portals/0/njr%207th%20annual%20report%202010.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2016.

3. Paul HA, Bargar WL, Mittlestadt B, et al. Development of a surgical robot for cementless total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;285:57-66.

4. Bobyn JD, Engh CA. Human histology of bone-porous metal implant interface. Orthopedics. 1984;7(9):1410.

5. Barrack RL. Dislocation after total hip arthroplasty: Implant design and orientation. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003;11(2):89-99.

6. Miki H, Sugano N, Yonenobu K, Tsuda K, Hattori M, Suzuki N. Detecting cause of dislocation after total hip arthroplasty by patient-specific four-dimensional motion analysis. Clin Biomech. 2013;28(2):182-186.

7. Sugano N. Computer-assisted orthopaedic surgery and robotic surgery in total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Surg. 2013;5(1):1-9.

8. Bargar WL, Bauer A, Börner M. Primary and revision total hip replacement using the Robodoc system. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1998;354:82-91.

9. Honl M, Dierk O, Gauck C, et al. Comparison of robotic-assisted and manual implantation of primary total hip replacement: a prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(8):1470-1478.

10. Nakamura N, Sugano N, Nishii T, Kakimoto A, Miki H. A comparison between robotic-assisted and manual implantation of cementless total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(4):1072-1081.

11. Nishihara S, Sugano N, Nishii T, Miki H, Nakamura N, Yoshikawa H. Comparison between hand rasping and robotic milling for stem implantation in cementless total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(7):957-966.

12. Hananouchi T, Sugano N, Nishii T, et al. Effect of robotic milling on periprosthetic bone remodeling. J Orthop Res. 2007;25(8):1062-1069.

13. Lim SJ, Ko KR, Park CW, Moon YW, Park YS. Robot-assisted primary cementless total hip arthroplasty with a short femoral stem: a prospective randomized short-term outcome study. Comput Aided Surg. 2015;20(1):41-46.

14. Nishihara S, Sugano N, Nishii T, et al. Clinical accuracy evaluation of femoral canal preparation using the ROBODOC system. J Orthop Sci. 2004;9(5):452-461.

15. Schulz AP, Seide K, Queitsch C, et al. Results of total hip replacement using the Robodoc surgical assistant system: clinical outcome and evaluation of complications for 97 procedures. Int J Med Robot. 2007;3(4):301-306.

16. Wyatt M, Hooper G, Framptom C, Rothwell A. Survival outcomes of cemented compared to uncemented stems in primary total hip replacement. World J Orthop. 2014;5(5):591-596.

17. Howard B. Is robotic surgery right for you? AARP The Magazine. December 2013/January 2014. Available at: http://www.aarp.org/health/conditions-treatments/info-12-2013/robotic-surgery-risks-benefits.html. Accessed April 12, 2016.