User login

Appropriate antibiotic selection for 12 common infections in obstetric patients

For the infections we most commonly encounter in obstetric practice, I review in this article the selection of specific antibiotics. I focus on the key pathogens that cause these infections, the most useful diagnostic tests, and the most cost-effective antibiotic therapy. Relative cost estimates (high vs low) for drugs are based on information published on the GoodRx website (https://www.goodrx.com/). Actual charges to patients, of course, may vary widely depending on contractual relationships between hospitals, insurance companies, and wholesale vendors. The infections are listed in alphabetical order, not in order of frequency or severity.

1. Bacterial vaginosis

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is a polymicrobial infection that results from perturbation of the normal vaginal flora due to conditions such as pregnancy, hormonal therapy, and changes in the menstrual cycle. It is characterized by a decrease in the vaginal concentration of Lactobacillus crispatus, followed by an increase in Prevotella bivia, Gardnerella vaginalis, Mobiluncus species, Atopobium vaginae, and Megasphaera type 1.1,2

BV is characterized by a thin, white-gray malodorous (fishlike smell) discharge. The vaginal pH is >4.5. Clue cells are apparent on saline microscopy, and the whiff (amine) test is positive when potassium hydroxide is added to a drop of vaginal secretions. Diagnostic accuracy can be improved using one of the new vaginal panel assays such as BD MAX Vaginal Panel (Becton, Dickinson and Company).3

Antibiotic selection

Antibiotic treatment of BV is directed primarily at the anaerobic component of the infection. The preferred treatment is oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 7 days. If the patient cannot tolerate metronidazole, oral clindamycin 300 mg twice daily for 7 days, can be used, although it is more expensive than metronidazole. Topical metronidazole vaginal gel (0.75%), 1 applicatorful daily for 5 days, is effective in treating the local vaginal infection, but it is not effective in preventing systemic complications such as preterm labor, chorioamnionitis, and puerperal endometritis.2 It also is significantly more expensive than the oral formulation of metronidazole. Topical clindamycin cream, 1 applicatorful daily for 5 days, is even more expensive.

Tinidazole 2 g orally daily for 2 days is an effective alternative to oral metronidazole. Single-dose therapy with oral secnidazole (2 g), a 5-nitroimidazole with a longer half-life than metronidazole, has been effective in small studies, but experience with this drug in the United States is limited. Secnidazole is also very expensive.4

2. Candidiasis

Vulvovaginal candidiasis usually is caused by Candida albicans. Other less common species include C tropicalis, C glabrata, C auris, C lusitaniae, and C krusei. The most common clinical findings are vulvovaginal pruritus in association with a curdlike white vaginal discharge. The diagnosis can be established by confirmation of a normal vaginal pH and identification of budding yeast and hyphae on a potassium hydroxide preparation. As noted above for BV, the vaginal panel assay improves the accuracy of clinical diagnosis.3 Culture usually is indicated only in patients with infections that are refractory to therapy.

Continue to: Antibiotic selection...

Antibiotic selection

In the first trimester of pregnancy, vulvovaginal candidiasis should be treated with a topical medication such as clotrimazole cream 1% (50 mg intravaginally daily for 7 days), miconazole cream 2% (100 mg intravaginally daily for 7 days), or terconazole cream 0.4% (50 g intravaginally daily for 7 days). Single-dose formulations or 3-day courses of treatment may not be quite as effective in pregnant patients, but they do offer a more convenient dosing schedule.2,5

Oral fluconazole should not be used in the first trimester of pregnancy because it has been associated with an increased risk for spontaneous abortion and with fetal cardiac septal defects. Beyond the first trimester, oral fluconazole offers an attractive option for treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. The appropriate dose is 150 mg initially, with a repeat dose in 3 days if symptoms persist.2,5

Ibrexafungerp (300 mg twice daily for 1 day) was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for oral treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. However, this drug is teratogenic and is contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation. It also is significantly more expensive than fluconazole.6

3. Cesarean delivery prophylaxis

All women having a cesarean delivery (CD) should receive antibiotic prophylaxis to reduce the risk of endometritis and wound infection.

Antibiotic selection

In my opinion, the preferred regimen is intravenous cefazolin 2 g plus azithromycin 500 mg administered preoperatively.7 Cefazolin can be administered in a rapid bolus; azithromycin should be administered over 1 hour.

In an exceptionally rigorous investigation called the C/SOAP trial (Cesarean Section Optimal Antibiotic Prophylaxis trial), Tita and colleagues showed that the combination of cefazolin plus azithromycin was superior to single-agent prophylaxis (usually with cefazolin) in preventing the composite of endometritis, wound infection, or other infection occurring within 6 weeks of surgery.8 The additive effect of azithromycin was particularly pronounced in patients having CD after labor and rupture of membranes. Harper and associates subsequently validated the cost-effectiveness of this combination regimen using a decision analytic model.9

If the patient has a serious allergy to β-lactam antibiotics, the best alternative regimen for prophylaxis is clindamycin plus gentamicin. The appropriate single intravenous dose of clindamycin is 900 mg; the single dose of gentamicin should be 5 mg/kg of ideal body weight (IBW).7

4. Chlamydia

Chlamydia trachomatis is an obligate intracellular bacterium. In pregnant women, it typically causes urethritis, endocervicitis, and inflammatory proctitis. Along with gonorrhea, it is the cause of an unusual infection/inflammation of the liver capsule, termed Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome (perihepatitis). The diagnosis of chlamydia infection is best confirmed with a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT). The NAAT simultaneously tests for chlamydia and gonorrhea in urine or in secretions obtained from the urethra, endocervix, and rectum.2

Antibiotic selection

The drug of choice for treating chlamydia in pregnancy is azithromycin 1,000 mg orally in a single dose. Erythromycin can be used as an alternative to azithromycin, but it usually is not well tolerated because of gastrointestinal adverse effects. In my practice, the preferred alternative for a patient who cannot tolerate azithromycin is amoxicillin 500 mg orally 3 times daily for 7 days.2,10

Continue to: 5. Chorioamnionitis...

5. Chorioamnionitis

Chorioamnionitis is a polymicrobial infection caused by anaerobes, aerobic gram-negative bacilli (predominantly Escherichia coli), and aerobic gram-positive cocci (primarily group B streptococci [GBS]). The diagnosis usually is made based on clinical examination: maternal fever, maternal and fetal tachycardia, and no other localizing sign of infection. The diagnosis can be confirmed by obtaining a sample of amniotic fluid via amniocentesis or via aspiration through the intrauterine pressure catheter and demonstrating a positive Gram stain, low glucose concentration (<20 mg/dL), positive nitrites, positive leukocyte esterase, and ultimately, a positive bacteriologic culture.2

Antibiotic selection

The initial treatment of chorioamnionitis specifically targets the 2 major organisms that cause neonatal pneumonia, meningitis, and sepsis: GBS and E coli. For many years, the drugs of choice have been intravenous ampicillin (2 g every 6 hours) plus intravenous gentamicin (5 mg/kg of IBW every 24 hours). Gentamicin also can be administered intravenously at a dose of 1.5 mg/kg every 8 hours. I prefer the once-daily dosing for 3 reasons:

- Gentamicin works by a concentration-dependent mechanism; the higher the initial serum concentration, the better the killing effect.

- Once-daily dosing preserves long periods with low trough levels, an effect that minimizes ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity.

- Once-daily dosing is more convenient.

In a patient who has a contraindication to use of an aminoglycoside, aztreonam (2 g intravenously every 8 hours) may be combined with ampicillin.2

If the patient delivers vaginally, 1 dose of each drug should be administered postpartum, and then the antibiotics should be discontinued. If the patient delivers by cesarean, a single dose of a medication with strong anaerobic coverage should be administered immediately after the infant’s umbilical cord is clamped. Options include clindamycin (900 mg intravenously) or metronidazole (500 mg intravenously).11

There are 2 key exceptions to the single postpartum dose rule, however. If the patient is obese (body mass index [BMI] >30 kg/m2) or if the membranes have been ruptured for more than 24 hours, antibiotics should be continued until she has been afebrile and asymptomatic for 24 hours.12

Two single agents are excellent alternatives to the combination ampicillin-gentamicin regimen. One is ampicillin-sulbactam, 3 g intravenously every 6 hours. The other is piperacillin-tazobactam, 3.375 g intravenously every 6 hours. These extended-spectrum penicillins provide exceptionally good coverage against the major pathogens that cause chorioamnionitis. Although more expensive than the combination regimen, they avoid the potential ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity associated with gentamicin.2

6. Endometritis

Puerperal endometritis is significantly more common after CD than after vaginal delivery. The infection is polymicrobial, and the principal pathogens are anaerobic gram-positive cocci, anaerobic gram-negative bacilli, aerobic gram-negative bacilli, and aerobic gram-positive cocci. The diagnosis usually is made almost exclusively based on clinical findings: fever within 24 to 36 hours of delivery, tachycardia, mild tachypnea, and lower abdominal/pelvic pain and tenderness in the absence of any other localizing sign of infection.13

Antibiotic selection

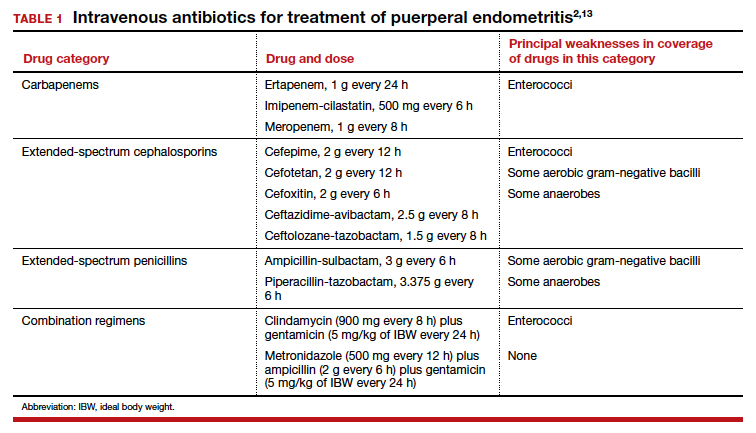

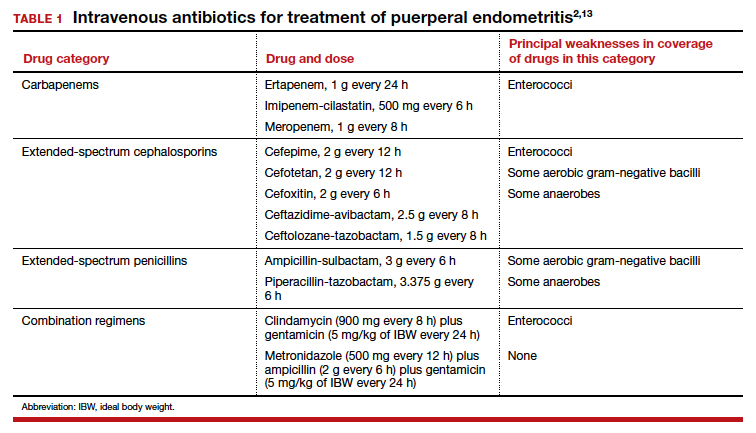

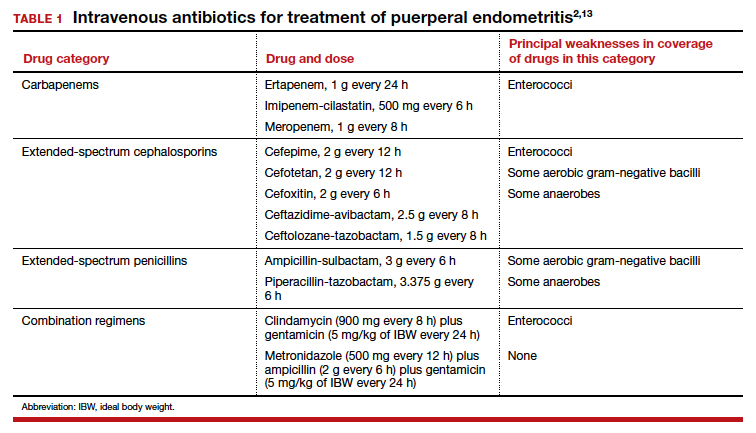

Effective treatment of endometritis requires administration of antibiotics that provide coverage against the broad range of pelvic pathogens. For many years, the gold standard of treatment has been the combination regimens of clindamycin plus gentamicin or metronidazole plus ampicillin plus gentamicin. These drugs are available in generic form and are relatively inexpensive. However, several broad-spectrum single agents are now available for treatment of endometritis. Although they are moderately more expensive than the generic combination regimens, they usually are very well tolerated, and they avoid the potential nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity associated with gentamicin. TABLE 1 summarizes the dosing regimens of these various agents and their potential weaknesses in coverage.2,13

7. Gonorrhea

Gonorrhea is caused by the gram-negative diplococcus, Neisseria gonorrhoeae. The organism has a propensity to infect columnar epithelium and uroepithelium, and, typically, it causes a localized infection of the urethra, endocervix, and rectum. The organism also can cause an oropharyngeal infection, a disseminated infection (most commonly manifested by dermatitis and arthritis), and perihepatitis.

The diagnosis is best confirmed by a NAAT that can simultaneously test for gonorrhea and chlamydia in urine or in secretions obtained from the urethra, endocervix, and rectum.2,10

Antibiotic selection

The drugs of choice for treating uncomplicated gonococcal infection in pregnancy are a single dose of ceftriaxone 500 mg intramuscularly, or cefixime 800 mg orally. If the patient is allergic to β-lactam antibiotics, the recommended treatment is gentamicin 240 mg intramuscularly in a single dose, combined with azithromycin 2,000 mg orally.14

8. Group B streptococci prophylaxis

The first-line agents for GBS prophylaxis are penicillin and ampicillin. Resistance of GBS to either of these antibiotics is extremely rare. The appropriate penicillin dose is 3 million U intravenously every 4 hours; the intravenous dose of ampicillin is 2 g initially, then 1 g every 4 hours. I prefer penicillin for prophylaxis because it has a narrower spectrum of activity and is less likely to cause antibiotic-associated diarrhea. The antibiotic should be continued until delivery of the neonate.2,15,16

If the patient has a mild allergy to penicillin, the drug of choice is cefazolin 2 g intravenously initially, then 1 g every 8 hours. If the patient’s allergy to β-lactam antibiotics is severe, the alternative agents are vancomycin (20 mg/kg intravenously every 8 hours infused over 1–2 hours; maximum single dose of 2 g) and clindamycin (900 mg intravenously every 8 hours). The latter drug should be used only if sensitivity testing has confirmed that the GBS strain is sensitive to clindamycin. Resistance to clindamycin usually ranges from 10% to 15%.2,15,16

9. Puerperal mastitis

The principal microorganisms that cause puerperal mastitis are the aerobic streptococci and staphylococci that form part of the normal skin flora. The diagnosis usually is made based on the characteristic clinical findings: erythema, tenderness, and warmth in an area of the breast accompanied by a purulent nipple discharge and fever and chills. The vast majority of cases can be treated with oral antibiotics on an outpatient basis. The key indications for hospitalization are severe illness, particularly in an immunocompromised patient, and suspicion of a breast abscess.2

Continue to: Antibiotic selection...

Antibiotic selection

The initial drug of choice for treatment of mastitis is dicloxacillin sodium 500 mg every 6 hours for 7 to 10 days. If the patient has a mild allergy to penicillin, the appropriate alternative is cephalexin 500 mg every 8 hours for 7 to 10 days. If the patient’s allergy to penicillin is severe, 2 alternatives are possible. One is clindamycin 300 mg twice daily for 7 to 10 days; the other is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength (800 mg/160 mg), twice daily for 7 to 10 days. The latter 2 drugs are also of great value if the patient fails to respond to initial therapy and/or infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is suspected.2 I prefer the latter agent because it is less expensive than clindamycin and is less likely to cause antibiotic-induced diarrhea.

If hospitalization is required, the drug of choice is intravenous vancomycin. The appropriate dosage is 20 mg/kg every 8 to 12 hours (maximum single dose of 2 g).2

10. Syphilis

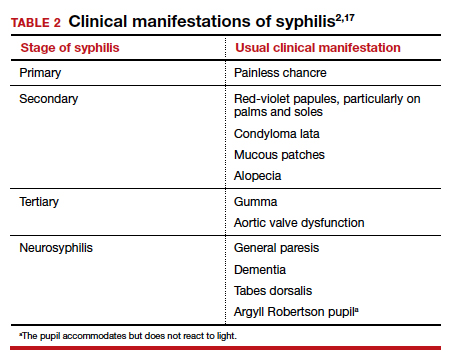

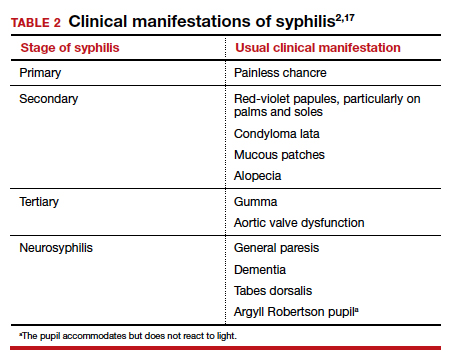

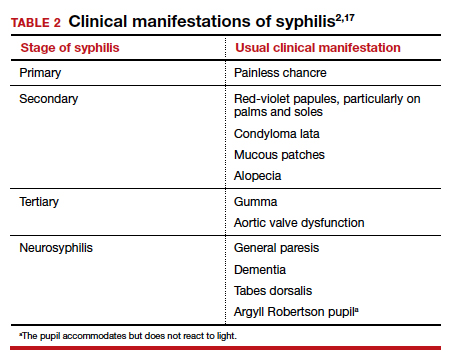

Syphilis is caused by the spirochete bacterium, Treponema pallidum. The diagnosis can be made by clinical examination if the characteristic findings listed in TABLE 2 are present.2,17 However, most patients in our practice will have latent syphilis, and the diagnosis must be established based on serologic screening.17

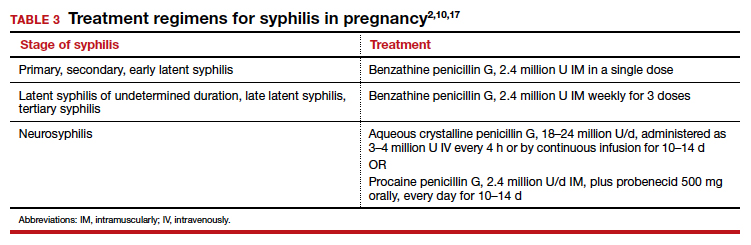

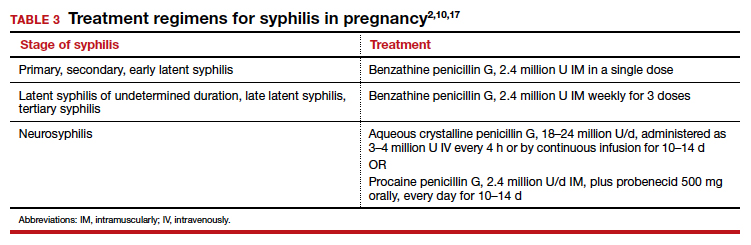

Antibiotic selection

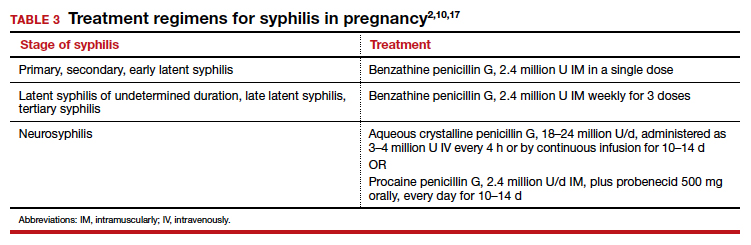

In pregnancy, the treatment of choice for syphilis is penicillin (TABLE 3).2,10,17 Only penicillin has been proven effective in treating both maternal and fetal infection. If the patient has a history of allergy to penicillin, she should undergo skin testing to determine if she is truly allergic. If hypersensitivity is confirmed, the patient should be desensitized and then treated with the appropriate regimen outlined in TABLE 3. Of interest, within a short period of time after treatment, the patient’s sensitivity to penicillin will be reestablished, and she should not be treated again with penicillin unless she undergoes another desensitization process.2,17

11. Trichomoniasis

Trichomoniasis is caused by the flagellated protozoan, Trichomonas vaginalis. The condition is characterized by a distinct yellowish-green vaginal discharge. The vaginal pH is >4.5, and motile flagellated organisms are easily visualized on saline microscopy. The vaginal panel assay also is a valuable diagnostic test.3

Antibiotic selection

The drug of choice for trichomoniasis is oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 7 days. The patient’s sexual partner(s) should be treated concurrently to prevent reinfection. Most treatment failures are due to poor compliance with therapy on the part of either the patient or her partner(s); true drug resistance is uncommon. When antibiotic resistance is strongly suspected, the patient may be treated with a single 2-g oral dose of tinidazole.2

12. Urinary tract infections

Urethritis

Acute urethritis usually is caused by C trachomatis or N gonorrhoeae. The treatment of infections with these 2 organisms is discussed above.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria and acute cystitis

Bladder infections are caused primarily by E coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Proteus species. Gram-positive cocci such as enterococci, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, and GBS are less common pathogens.18

The key diagnostic criterion for asymptomatic bacteriuria is a colony count greater than 100,000 organisms/mL of a single uropathogen on a clean-catch midstream urine specimen.18

The usual clinical manifestations of acute cystitis include frequency, urgency, hesitancy, suprapubic discomfort, and a low-grade fever. The diagnosis is most effectively confirmed by obtaining urine by catheterization and demonstrating a positive nitrite and positive leukocyte esterase reaction on dipstick examination. The finding of a urine pH of 8 or greater usually indicates an infection caused by Proteus species. When urine is obtained by catheterization, the criterion for defining a positive culture is greater than 100 colonies/mL.18

Antibiotic selection. In the first trimester, the preferred agents for treatment of a lower urinary tract infection are oral amoxicillin (875 mg twice daily) or cephalexin (500 mg every 8 hours). For an initial infection, a 3-day course of therapy usually is adequate. For a recurrent infection, a 7- to 10-day course is indicated.

Beyond the first trimester, nitrofurantoin monohydrate macrocrystals (100 mg orally twice daily) or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength (800 mg/160 mg twice daily) are the preferred agents. Unless no other oral drug is likely to be effective, these 2 drugs should be avoided in the first trimester. The former has been associated with eye, heart, and cleft defects. The latter has been associated with neural tube defects, cardiac anomalies, choanal atresia, and diaphragmatic hernia.18

Acute pyelonephritis

Acute infections of the kidney usually are caused by the aerobic gram-negative bacilli: E coli, K pneumoniae, and Proteus species. Enterococci, S saprophyticus, and GBS are less likely to cause upper tract infection as opposed to bladder infection.

The typical clinical manifestations of acute pyelonephritis include high fever and chills in association with flank pain and tenderness. The diagnosis is best confirmed by obtaining urine by catheterization and documenting the presence of a positive nitrite and leukocyte esterase reaction. Again, an elevated urine pH is indicative of an infection secondary to Proteus species. The criterion for defining a positive culture from catheterized urine is greater than 100 colonies/mL.2,18

Antibiotic selection. Patients in the first half of pregnancy who are hemodynamically stable and who show no signs of preterm labor may be treated with oral antibiotics as outpatients. The 2 drugs of choice are amoxicillin-clavulanate (875 mg twice daily for 7 to 10 days) or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength (800 mg/160 mg twice daily for 7 to 10 days).

For unstable patients in the first half of pregnancy and for essentially all patients in the second half of pregnancy, parenteral treatment should be administered on an inpatient basis. My preference for treatment is ceftriaxone, 2 g intravenously every 24 hours. The drug provides excellent coverage against almost all the uropathogens. It has a convenient dosing schedule, and it usually is very well tolerated. Parenteral therapy should be continued until the patient has been afebrile and asymptomatic for 24 to 48 hours. At this point, the patient can be transitioned to one of the oral regimens listed above and managed as an outpatient. If the patient is allergic to β-lactam antibiotics, an excellent alternative is aztreonam, 2 g intravenously every 8 hours.2,18 ●

- Reeder CF, Duff P. A case of BV during pregnancy: best management approach. OBG Manag. 2021;33(2):38-42.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infection in pregnancy: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al, eds. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies, 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1145.

- Broache M, Cammarata CL, Stonebraker E, et al. Performance of a vaginal panel assay compared with the clinical diagnosis of vaginitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:853-859.

- Hiller SL, Nyirjesy P, Waldbaum AS, et al. Secnidazole treatment of bacterial vaginosis: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:379-386.

- Kirkpatrick K, Duff P. Candidiasis: the essentials of diagnosis and treatment. OBG Manag. 2020;32(8):27-29, 34.

- Ibrexafungerp (Brexafemme) for vulvovaginal candidiasis. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2021;63:141-143.

- Duff P. Prevention of infection after cesarean delivery. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;62:758-770.

- Tita AT, Szychowski JM, Boggess K, et al; for the C/SOAP Trial Consortium. Adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis for cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1231-1241.

- Harper LM, Kilgore M, Szychowski JM, et al. Economic evaluation of adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis for cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:328-334.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(RR3):1-137.

- Edwards RK, Duff P. Single additional dose postpartum therapy for women with chorioamnionitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(5 pt 1):957-961.

- Black LP, Hinson L, Duff P. Limited course of antibiotic treatment for chorioamnionitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:1102-1105.

- Duff P. Fever following cesarean delivery: what are your steps for management? OBG Manag. 2021;33(12):26-30, 35.

- St Cyr S, Barbee L, Warkowski KA, et al. Update to CDC’s treatment guidelines for gonococcal infection, 2020. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1911-1916.

- Prevention of group B streptococcal early-onset disease in newborns: ACOG committee opinion summary, number 782. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:1.

- Duff P. Preventing early-onset group B streptococcal disease in newborns. OBG Manag. 2019;31(12):26, 28-31.

- Finley TA, Duff P. Syphilis: cutting risk through primary prevention and prenatal screening. OBG Manag. 2020;32(11):20, 22-27.

- Duff P. UTIs in pregnancy: managing urethritis, asymptomatic bacteriuria, cystitis, and pyelonephritis. OBG Manag. 2022;34(1):42-46.

For the infections we most commonly encounter in obstetric practice, I review in this article the selection of specific antibiotics. I focus on the key pathogens that cause these infections, the most useful diagnostic tests, and the most cost-effective antibiotic therapy. Relative cost estimates (high vs low) for drugs are based on information published on the GoodRx website (https://www.goodrx.com/). Actual charges to patients, of course, may vary widely depending on contractual relationships between hospitals, insurance companies, and wholesale vendors. The infections are listed in alphabetical order, not in order of frequency or severity.

1. Bacterial vaginosis

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is a polymicrobial infection that results from perturbation of the normal vaginal flora due to conditions such as pregnancy, hormonal therapy, and changes in the menstrual cycle. It is characterized by a decrease in the vaginal concentration of Lactobacillus crispatus, followed by an increase in Prevotella bivia, Gardnerella vaginalis, Mobiluncus species, Atopobium vaginae, and Megasphaera type 1.1,2

BV is characterized by a thin, white-gray malodorous (fishlike smell) discharge. The vaginal pH is >4.5. Clue cells are apparent on saline microscopy, and the whiff (amine) test is positive when potassium hydroxide is added to a drop of vaginal secretions. Diagnostic accuracy can be improved using one of the new vaginal panel assays such as BD MAX Vaginal Panel (Becton, Dickinson and Company).3

Antibiotic selection

Antibiotic treatment of BV is directed primarily at the anaerobic component of the infection. The preferred treatment is oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 7 days. If the patient cannot tolerate metronidazole, oral clindamycin 300 mg twice daily for 7 days, can be used, although it is more expensive than metronidazole. Topical metronidazole vaginal gel (0.75%), 1 applicatorful daily for 5 days, is effective in treating the local vaginal infection, but it is not effective in preventing systemic complications such as preterm labor, chorioamnionitis, and puerperal endometritis.2 It also is significantly more expensive than the oral formulation of metronidazole. Topical clindamycin cream, 1 applicatorful daily for 5 days, is even more expensive.

Tinidazole 2 g orally daily for 2 days is an effective alternative to oral metronidazole. Single-dose therapy with oral secnidazole (2 g), a 5-nitroimidazole with a longer half-life than metronidazole, has been effective in small studies, but experience with this drug in the United States is limited. Secnidazole is also very expensive.4

2. Candidiasis

Vulvovaginal candidiasis usually is caused by Candida albicans. Other less common species include C tropicalis, C glabrata, C auris, C lusitaniae, and C krusei. The most common clinical findings are vulvovaginal pruritus in association with a curdlike white vaginal discharge. The diagnosis can be established by confirmation of a normal vaginal pH and identification of budding yeast and hyphae on a potassium hydroxide preparation. As noted above for BV, the vaginal panel assay improves the accuracy of clinical diagnosis.3 Culture usually is indicated only in patients with infections that are refractory to therapy.

Continue to: Antibiotic selection...

Antibiotic selection

In the first trimester of pregnancy, vulvovaginal candidiasis should be treated with a topical medication such as clotrimazole cream 1% (50 mg intravaginally daily for 7 days), miconazole cream 2% (100 mg intravaginally daily for 7 days), or terconazole cream 0.4% (50 g intravaginally daily for 7 days). Single-dose formulations or 3-day courses of treatment may not be quite as effective in pregnant patients, but they do offer a more convenient dosing schedule.2,5

Oral fluconazole should not be used in the first trimester of pregnancy because it has been associated with an increased risk for spontaneous abortion and with fetal cardiac septal defects. Beyond the first trimester, oral fluconazole offers an attractive option for treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. The appropriate dose is 150 mg initially, with a repeat dose in 3 days if symptoms persist.2,5

Ibrexafungerp (300 mg twice daily for 1 day) was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for oral treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. However, this drug is teratogenic and is contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation. It also is significantly more expensive than fluconazole.6

3. Cesarean delivery prophylaxis

All women having a cesarean delivery (CD) should receive antibiotic prophylaxis to reduce the risk of endometritis and wound infection.

Antibiotic selection

In my opinion, the preferred regimen is intravenous cefazolin 2 g plus azithromycin 500 mg administered preoperatively.7 Cefazolin can be administered in a rapid bolus; azithromycin should be administered over 1 hour.

In an exceptionally rigorous investigation called the C/SOAP trial (Cesarean Section Optimal Antibiotic Prophylaxis trial), Tita and colleagues showed that the combination of cefazolin plus azithromycin was superior to single-agent prophylaxis (usually with cefazolin) in preventing the composite of endometritis, wound infection, or other infection occurring within 6 weeks of surgery.8 The additive effect of azithromycin was particularly pronounced in patients having CD after labor and rupture of membranes. Harper and associates subsequently validated the cost-effectiveness of this combination regimen using a decision analytic model.9

If the patient has a serious allergy to β-lactam antibiotics, the best alternative regimen for prophylaxis is clindamycin plus gentamicin. The appropriate single intravenous dose of clindamycin is 900 mg; the single dose of gentamicin should be 5 mg/kg of ideal body weight (IBW).7

4. Chlamydia

Chlamydia trachomatis is an obligate intracellular bacterium. In pregnant women, it typically causes urethritis, endocervicitis, and inflammatory proctitis. Along with gonorrhea, it is the cause of an unusual infection/inflammation of the liver capsule, termed Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome (perihepatitis). The diagnosis of chlamydia infection is best confirmed with a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT). The NAAT simultaneously tests for chlamydia and gonorrhea in urine or in secretions obtained from the urethra, endocervix, and rectum.2

Antibiotic selection

The drug of choice for treating chlamydia in pregnancy is azithromycin 1,000 mg orally in a single dose. Erythromycin can be used as an alternative to azithromycin, but it usually is not well tolerated because of gastrointestinal adverse effects. In my practice, the preferred alternative for a patient who cannot tolerate azithromycin is amoxicillin 500 mg orally 3 times daily for 7 days.2,10

Continue to: 5. Chorioamnionitis...

5. Chorioamnionitis

Chorioamnionitis is a polymicrobial infection caused by anaerobes, aerobic gram-negative bacilli (predominantly Escherichia coli), and aerobic gram-positive cocci (primarily group B streptococci [GBS]). The diagnosis usually is made based on clinical examination: maternal fever, maternal and fetal tachycardia, and no other localizing sign of infection. The diagnosis can be confirmed by obtaining a sample of amniotic fluid via amniocentesis or via aspiration through the intrauterine pressure catheter and demonstrating a positive Gram stain, low glucose concentration (<20 mg/dL), positive nitrites, positive leukocyte esterase, and ultimately, a positive bacteriologic culture.2

Antibiotic selection

The initial treatment of chorioamnionitis specifically targets the 2 major organisms that cause neonatal pneumonia, meningitis, and sepsis: GBS and E coli. For many years, the drugs of choice have been intravenous ampicillin (2 g every 6 hours) plus intravenous gentamicin (5 mg/kg of IBW every 24 hours). Gentamicin also can be administered intravenously at a dose of 1.5 mg/kg every 8 hours. I prefer the once-daily dosing for 3 reasons:

- Gentamicin works by a concentration-dependent mechanism; the higher the initial serum concentration, the better the killing effect.

- Once-daily dosing preserves long periods with low trough levels, an effect that minimizes ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity.

- Once-daily dosing is more convenient.

In a patient who has a contraindication to use of an aminoglycoside, aztreonam (2 g intravenously every 8 hours) may be combined with ampicillin.2

If the patient delivers vaginally, 1 dose of each drug should be administered postpartum, and then the antibiotics should be discontinued. If the patient delivers by cesarean, a single dose of a medication with strong anaerobic coverage should be administered immediately after the infant’s umbilical cord is clamped. Options include clindamycin (900 mg intravenously) or metronidazole (500 mg intravenously).11

There are 2 key exceptions to the single postpartum dose rule, however. If the patient is obese (body mass index [BMI] >30 kg/m2) or if the membranes have been ruptured for more than 24 hours, antibiotics should be continued until she has been afebrile and asymptomatic for 24 hours.12

Two single agents are excellent alternatives to the combination ampicillin-gentamicin regimen. One is ampicillin-sulbactam, 3 g intravenously every 6 hours. The other is piperacillin-tazobactam, 3.375 g intravenously every 6 hours. These extended-spectrum penicillins provide exceptionally good coverage against the major pathogens that cause chorioamnionitis. Although more expensive than the combination regimen, they avoid the potential ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity associated with gentamicin.2

6. Endometritis

Puerperal endometritis is significantly more common after CD than after vaginal delivery. The infection is polymicrobial, and the principal pathogens are anaerobic gram-positive cocci, anaerobic gram-negative bacilli, aerobic gram-negative bacilli, and aerobic gram-positive cocci. The diagnosis usually is made almost exclusively based on clinical findings: fever within 24 to 36 hours of delivery, tachycardia, mild tachypnea, and lower abdominal/pelvic pain and tenderness in the absence of any other localizing sign of infection.13

Antibiotic selection

Effective treatment of endometritis requires administration of antibiotics that provide coverage against the broad range of pelvic pathogens. For many years, the gold standard of treatment has been the combination regimens of clindamycin plus gentamicin or metronidazole plus ampicillin plus gentamicin. These drugs are available in generic form and are relatively inexpensive. However, several broad-spectrum single agents are now available for treatment of endometritis. Although they are moderately more expensive than the generic combination regimens, they usually are very well tolerated, and they avoid the potential nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity associated with gentamicin. TABLE 1 summarizes the dosing regimens of these various agents and their potential weaknesses in coverage.2,13

7. Gonorrhea

Gonorrhea is caused by the gram-negative diplococcus, Neisseria gonorrhoeae. The organism has a propensity to infect columnar epithelium and uroepithelium, and, typically, it causes a localized infection of the urethra, endocervix, and rectum. The organism also can cause an oropharyngeal infection, a disseminated infection (most commonly manifested by dermatitis and arthritis), and perihepatitis.

The diagnosis is best confirmed by a NAAT that can simultaneously test for gonorrhea and chlamydia in urine or in secretions obtained from the urethra, endocervix, and rectum.2,10

Antibiotic selection

The drugs of choice for treating uncomplicated gonococcal infection in pregnancy are a single dose of ceftriaxone 500 mg intramuscularly, or cefixime 800 mg orally. If the patient is allergic to β-lactam antibiotics, the recommended treatment is gentamicin 240 mg intramuscularly in a single dose, combined with azithromycin 2,000 mg orally.14

8. Group B streptococci prophylaxis

The first-line agents for GBS prophylaxis are penicillin and ampicillin. Resistance of GBS to either of these antibiotics is extremely rare. The appropriate penicillin dose is 3 million U intravenously every 4 hours; the intravenous dose of ampicillin is 2 g initially, then 1 g every 4 hours. I prefer penicillin for prophylaxis because it has a narrower spectrum of activity and is less likely to cause antibiotic-associated diarrhea. The antibiotic should be continued until delivery of the neonate.2,15,16

If the patient has a mild allergy to penicillin, the drug of choice is cefazolin 2 g intravenously initially, then 1 g every 8 hours. If the patient’s allergy to β-lactam antibiotics is severe, the alternative agents are vancomycin (20 mg/kg intravenously every 8 hours infused over 1–2 hours; maximum single dose of 2 g) and clindamycin (900 mg intravenously every 8 hours). The latter drug should be used only if sensitivity testing has confirmed that the GBS strain is sensitive to clindamycin. Resistance to clindamycin usually ranges from 10% to 15%.2,15,16

9. Puerperal mastitis

The principal microorganisms that cause puerperal mastitis are the aerobic streptococci and staphylococci that form part of the normal skin flora. The diagnosis usually is made based on the characteristic clinical findings: erythema, tenderness, and warmth in an area of the breast accompanied by a purulent nipple discharge and fever and chills. The vast majority of cases can be treated with oral antibiotics on an outpatient basis. The key indications for hospitalization are severe illness, particularly in an immunocompromised patient, and suspicion of a breast abscess.2

Continue to: Antibiotic selection...

Antibiotic selection

The initial drug of choice for treatment of mastitis is dicloxacillin sodium 500 mg every 6 hours for 7 to 10 days. If the patient has a mild allergy to penicillin, the appropriate alternative is cephalexin 500 mg every 8 hours for 7 to 10 days. If the patient’s allergy to penicillin is severe, 2 alternatives are possible. One is clindamycin 300 mg twice daily for 7 to 10 days; the other is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength (800 mg/160 mg), twice daily for 7 to 10 days. The latter 2 drugs are also of great value if the patient fails to respond to initial therapy and/or infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is suspected.2 I prefer the latter agent because it is less expensive than clindamycin and is less likely to cause antibiotic-induced diarrhea.

If hospitalization is required, the drug of choice is intravenous vancomycin. The appropriate dosage is 20 mg/kg every 8 to 12 hours (maximum single dose of 2 g).2

10. Syphilis

Syphilis is caused by the spirochete bacterium, Treponema pallidum. The diagnosis can be made by clinical examination if the characteristic findings listed in TABLE 2 are present.2,17 However, most patients in our practice will have latent syphilis, and the diagnosis must be established based on serologic screening.17

Antibiotic selection

In pregnancy, the treatment of choice for syphilis is penicillin (TABLE 3).2,10,17 Only penicillin has been proven effective in treating both maternal and fetal infection. If the patient has a history of allergy to penicillin, she should undergo skin testing to determine if she is truly allergic. If hypersensitivity is confirmed, the patient should be desensitized and then treated with the appropriate regimen outlined in TABLE 3. Of interest, within a short period of time after treatment, the patient’s sensitivity to penicillin will be reestablished, and she should not be treated again with penicillin unless she undergoes another desensitization process.2,17

11. Trichomoniasis

Trichomoniasis is caused by the flagellated protozoan, Trichomonas vaginalis. The condition is characterized by a distinct yellowish-green vaginal discharge. The vaginal pH is >4.5, and motile flagellated organisms are easily visualized on saline microscopy. The vaginal panel assay also is a valuable diagnostic test.3

Antibiotic selection

The drug of choice for trichomoniasis is oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 7 days. The patient’s sexual partner(s) should be treated concurrently to prevent reinfection. Most treatment failures are due to poor compliance with therapy on the part of either the patient or her partner(s); true drug resistance is uncommon. When antibiotic resistance is strongly suspected, the patient may be treated with a single 2-g oral dose of tinidazole.2

12. Urinary tract infections

Urethritis

Acute urethritis usually is caused by C trachomatis or N gonorrhoeae. The treatment of infections with these 2 organisms is discussed above.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria and acute cystitis

Bladder infections are caused primarily by E coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Proteus species. Gram-positive cocci such as enterococci, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, and GBS are less common pathogens.18

The key diagnostic criterion for asymptomatic bacteriuria is a colony count greater than 100,000 organisms/mL of a single uropathogen on a clean-catch midstream urine specimen.18

The usual clinical manifestations of acute cystitis include frequency, urgency, hesitancy, suprapubic discomfort, and a low-grade fever. The diagnosis is most effectively confirmed by obtaining urine by catheterization and demonstrating a positive nitrite and positive leukocyte esterase reaction on dipstick examination. The finding of a urine pH of 8 or greater usually indicates an infection caused by Proteus species. When urine is obtained by catheterization, the criterion for defining a positive culture is greater than 100 colonies/mL.18

Antibiotic selection. In the first trimester, the preferred agents for treatment of a lower urinary tract infection are oral amoxicillin (875 mg twice daily) or cephalexin (500 mg every 8 hours). For an initial infection, a 3-day course of therapy usually is adequate. For a recurrent infection, a 7- to 10-day course is indicated.

Beyond the first trimester, nitrofurantoin monohydrate macrocrystals (100 mg orally twice daily) or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength (800 mg/160 mg twice daily) are the preferred agents. Unless no other oral drug is likely to be effective, these 2 drugs should be avoided in the first trimester. The former has been associated with eye, heart, and cleft defects. The latter has been associated with neural tube defects, cardiac anomalies, choanal atresia, and diaphragmatic hernia.18

Acute pyelonephritis

Acute infections of the kidney usually are caused by the aerobic gram-negative bacilli: E coli, K pneumoniae, and Proteus species. Enterococci, S saprophyticus, and GBS are less likely to cause upper tract infection as opposed to bladder infection.

The typical clinical manifestations of acute pyelonephritis include high fever and chills in association with flank pain and tenderness. The diagnosis is best confirmed by obtaining urine by catheterization and documenting the presence of a positive nitrite and leukocyte esterase reaction. Again, an elevated urine pH is indicative of an infection secondary to Proteus species. The criterion for defining a positive culture from catheterized urine is greater than 100 colonies/mL.2,18

Antibiotic selection. Patients in the first half of pregnancy who are hemodynamically stable and who show no signs of preterm labor may be treated with oral antibiotics as outpatients. The 2 drugs of choice are amoxicillin-clavulanate (875 mg twice daily for 7 to 10 days) or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength (800 mg/160 mg twice daily for 7 to 10 days).

For unstable patients in the first half of pregnancy and for essentially all patients in the second half of pregnancy, parenteral treatment should be administered on an inpatient basis. My preference for treatment is ceftriaxone, 2 g intravenously every 24 hours. The drug provides excellent coverage against almost all the uropathogens. It has a convenient dosing schedule, and it usually is very well tolerated. Parenteral therapy should be continued until the patient has been afebrile and asymptomatic for 24 to 48 hours. At this point, the patient can be transitioned to one of the oral regimens listed above and managed as an outpatient. If the patient is allergic to β-lactam antibiotics, an excellent alternative is aztreonam, 2 g intravenously every 8 hours.2,18 ●

For the infections we most commonly encounter in obstetric practice, I review in this article the selection of specific antibiotics. I focus on the key pathogens that cause these infections, the most useful diagnostic tests, and the most cost-effective antibiotic therapy. Relative cost estimates (high vs low) for drugs are based on information published on the GoodRx website (https://www.goodrx.com/). Actual charges to patients, of course, may vary widely depending on contractual relationships between hospitals, insurance companies, and wholesale vendors. The infections are listed in alphabetical order, not in order of frequency or severity.

1. Bacterial vaginosis

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is a polymicrobial infection that results from perturbation of the normal vaginal flora due to conditions such as pregnancy, hormonal therapy, and changes in the menstrual cycle. It is characterized by a decrease in the vaginal concentration of Lactobacillus crispatus, followed by an increase in Prevotella bivia, Gardnerella vaginalis, Mobiluncus species, Atopobium vaginae, and Megasphaera type 1.1,2

BV is characterized by a thin, white-gray malodorous (fishlike smell) discharge. The vaginal pH is >4.5. Clue cells are apparent on saline microscopy, and the whiff (amine) test is positive when potassium hydroxide is added to a drop of vaginal secretions. Diagnostic accuracy can be improved using one of the new vaginal panel assays such as BD MAX Vaginal Panel (Becton, Dickinson and Company).3

Antibiotic selection

Antibiotic treatment of BV is directed primarily at the anaerobic component of the infection. The preferred treatment is oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 7 days. If the patient cannot tolerate metronidazole, oral clindamycin 300 mg twice daily for 7 days, can be used, although it is more expensive than metronidazole. Topical metronidazole vaginal gel (0.75%), 1 applicatorful daily for 5 days, is effective in treating the local vaginal infection, but it is not effective in preventing systemic complications such as preterm labor, chorioamnionitis, and puerperal endometritis.2 It also is significantly more expensive than the oral formulation of metronidazole. Topical clindamycin cream, 1 applicatorful daily for 5 days, is even more expensive.

Tinidazole 2 g orally daily for 2 days is an effective alternative to oral metronidazole. Single-dose therapy with oral secnidazole (2 g), a 5-nitroimidazole with a longer half-life than metronidazole, has been effective in small studies, but experience with this drug in the United States is limited. Secnidazole is also very expensive.4

2. Candidiasis

Vulvovaginal candidiasis usually is caused by Candida albicans. Other less common species include C tropicalis, C glabrata, C auris, C lusitaniae, and C krusei. The most common clinical findings are vulvovaginal pruritus in association with a curdlike white vaginal discharge. The diagnosis can be established by confirmation of a normal vaginal pH and identification of budding yeast and hyphae on a potassium hydroxide preparation. As noted above for BV, the vaginal panel assay improves the accuracy of clinical diagnosis.3 Culture usually is indicated only in patients with infections that are refractory to therapy.

Continue to: Antibiotic selection...

Antibiotic selection

In the first trimester of pregnancy, vulvovaginal candidiasis should be treated with a topical medication such as clotrimazole cream 1% (50 mg intravaginally daily for 7 days), miconazole cream 2% (100 mg intravaginally daily for 7 days), or terconazole cream 0.4% (50 g intravaginally daily for 7 days). Single-dose formulations or 3-day courses of treatment may not be quite as effective in pregnant patients, but they do offer a more convenient dosing schedule.2,5

Oral fluconazole should not be used in the first trimester of pregnancy because it has been associated with an increased risk for spontaneous abortion and with fetal cardiac septal defects. Beyond the first trimester, oral fluconazole offers an attractive option for treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. The appropriate dose is 150 mg initially, with a repeat dose in 3 days if symptoms persist.2,5

Ibrexafungerp (300 mg twice daily for 1 day) was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for oral treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. However, this drug is teratogenic and is contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation. It also is significantly more expensive than fluconazole.6

3. Cesarean delivery prophylaxis

All women having a cesarean delivery (CD) should receive antibiotic prophylaxis to reduce the risk of endometritis and wound infection.

Antibiotic selection

In my opinion, the preferred regimen is intravenous cefazolin 2 g plus azithromycin 500 mg administered preoperatively.7 Cefazolin can be administered in a rapid bolus; azithromycin should be administered over 1 hour.

In an exceptionally rigorous investigation called the C/SOAP trial (Cesarean Section Optimal Antibiotic Prophylaxis trial), Tita and colleagues showed that the combination of cefazolin plus azithromycin was superior to single-agent prophylaxis (usually with cefazolin) in preventing the composite of endometritis, wound infection, or other infection occurring within 6 weeks of surgery.8 The additive effect of azithromycin was particularly pronounced in patients having CD after labor and rupture of membranes. Harper and associates subsequently validated the cost-effectiveness of this combination regimen using a decision analytic model.9

If the patient has a serious allergy to β-lactam antibiotics, the best alternative regimen for prophylaxis is clindamycin plus gentamicin. The appropriate single intravenous dose of clindamycin is 900 mg; the single dose of gentamicin should be 5 mg/kg of ideal body weight (IBW).7

4. Chlamydia

Chlamydia trachomatis is an obligate intracellular bacterium. In pregnant women, it typically causes urethritis, endocervicitis, and inflammatory proctitis. Along with gonorrhea, it is the cause of an unusual infection/inflammation of the liver capsule, termed Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome (perihepatitis). The diagnosis of chlamydia infection is best confirmed with a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT). The NAAT simultaneously tests for chlamydia and gonorrhea in urine or in secretions obtained from the urethra, endocervix, and rectum.2

Antibiotic selection

The drug of choice for treating chlamydia in pregnancy is azithromycin 1,000 mg orally in a single dose. Erythromycin can be used as an alternative to azithromycin, but it usually is not well tolerated because of gastrointestinal adverse effects. In my practice, the preferred alternative for a patient who cannot tolerate azithromycin is amoxicillin 500 mg orally 3 times daily for 7 days.2,10

Continue to: 5. Chorioamnionitis...

5. Chorioamnionitis

Chorioamnionitis is a polymicrobial infection caused by anaerobes, aerobic gram-negative bacilli (predominantly Escherichia coli), and aerobic gram-positive cocci (primarily group B streptococci [GBS]). The diagnosis usually is made based on clinical examination: maternal fever, maternal and fetal tachycardia, and no other localizing sign of infection. The diagnosis can be confirmed by obtaining a sample of amniotic fluid via amniocentesis or via aspiration through the intrauterine pressure catheter and demonstrating a positive Gram stain, low glucose concentration (<20 mg/dL), positive nitrites, positive leukocyte esterase, and ultimately, a positive bacteriologic culture.2

Antibiotic selection

The initial treatment of chorioamnionitis specifically targets the 2 major organisms that cause neonatal pneumonia, meningitis, and sepsis: GBS and E coli. For many years, the drugs of choice have been intravenous ampicillin (2 g every 6 hours) plus intravenous gentamicin (5 mg/kg of IBW every 24 hours). Gentamicin also can be administered intravenously at a dose of 1.5 mg/kg every 8 hours. I prefer the once-daily dosing for 3 reasons:

- Gentamicin works by a concentration-dependent mechanism; the higher the initial serum concentration, the better the killing effect.

- Once-daily dosing preserves long periods with low trough levels, an effect that minimizes ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity.

- Once-daily dosing is more convenient.

In a patient who has a contraindication to use of an aminoglycoside, aztreonam (2 g intravenously every 8 hours) may be combined with ampicillin.2

If the patient delivers vaginally, 1 dose of each drug should be administered postpartum, and then the antibiotics should be discontinued. If the patient delivers by cesarean, a single dose of a medication with strong anaerobic coverage should be administered immediately after the infant’s umbilical cord is clamped. Options include clindamycin (900 mg intravenously) or metronidazole (500 mg intravenously).11

There are 2 key exceptions to the single postpartum dose rule, however. If the patient is obese (body mass index [BMI] >30 kg/m2) or if the membranes have been ruptured for more than 24 hours, antibiotics should be continued until she has been afebrile and asymptomatic for 24 hours.12

Two single agents are excellent alternatives to the combination ampicillin-gentamicin regimen. One is ampicillin-sulbactam, 3 g intravenously every 6 hours. The other is piperacillin-tazobactam, 3.375 g intravenously every 6 hours. These extended-spectrum penicillins provide exceptionally good coverage against the major pathogens that cause chorioamnionitis. Although more expensive than the combination regimen, they avoid the potential ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity associated with gentamicin.2

6. Endometritis

Puerperal endometritis is significantly more common after CD than after vaginal delivery. The infection is polymicrobial, and the principal pathogens are anaerobic gram-positive cocci, anaerobic gram-negative bacilli, aerobic gram-negative bacilli, and aerobic gram-positive cocci. The diagnosis usually is made almost exclusively based on clinical findings: fever within 24 to 36 hours of delivery, tachycardia, mild tachypnea, and lower abdominal/pelvic pain and tenderness in the absence of any other localizing sign of infection.13

Antibiotic selection

Effective treatment of endometritis requires administration of antibiotics that provide coverage against the broad range of pelvic pathogens. For many years, the gold standard of treatment has been the combination regimens of clindamycin plus gentamicin or metronidazole plus ampicillin plus gentamicin. These drugs are available in generic form and are relatively inexpensive. However, several broad-spectrum single agents are now available for treatment of endometritis. Although they are moderately more expensive than the generic combination regimens, they usually are very well tolerated, and they avoid the potential nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity associated with gentamicin. TABLE 1 summarizes the dosing regimens of these various agents and their potential weaknesses in coverage.2,13

7. Gonorrhea

Gonorrhea is caused by the gram-negative diplococcus, Neisseria gonorrhoeae. The organism has a propensity to infect columnar epithelium and uroepithelium, and, typically, it causes a localized infection of the urethra, endocervix, and rectum. The organism also can cause an oropharyngeal infection, a disseminated infection (most commonly manifested by dermatitis and arthritis), and perihepatitis.

The diagnosis is best confirmed by a NAAT that can simultaneously test for gonorrhea and chlamydia in urine or in secretions obtained from the urethra, endocervix, and rectum.2,10

Antibiotic selection

The drugs of choice for treating uncomplicated gonococcal infection in pregnancy are a single dose of ceftriaxone 500 mg intramuscularly, or cefixime 800 mg orally. If the patient is allergic to β-lactam antibiotics, the recommended treatment is gentamicin 240 mg intramuscularly in a single dose, combined with azithromycin 2,000 mg orally.14

8. Group B streptococci prophylaxis

The first-line agents for GBS prophylaxis are penicillin and ampicillin. Resistance of GBS to either of these antibiotics is extremely rare. The appropriate penicillin dose is 3 million U intravenously every 4 hours; the intravenous dose of ampicillin is 2 g initially, then 1 g every 4 hours. I prefer penicillin for prophylaxis because it has a narrower spectrum of activity and is less likely to cause antibiotic-associated diarrhea. The antibiotic should be continued until delivery of the neonate.2,15,16

If the patient has a mild allergy to penicillin, the drug of choice is cefazolin 2 g intravenously initially, then 1 g every 8 hours. If the patient’s allergy to β-lactam antibiotics is severe, the alternative agents are vancomycin (20 mg/kg intravenously every 8 hours infused over 1–2 hours; maximum single dose of 2 g) and clindamycin (900 mg intravenously every 8 hours). The latter drug should be used only if sensitivity testing has confirmed that the GBS strain is sensitive to clindamycin. Resistance to clindamycin usually ranges from 10% to 15%.2,15,16

9. Puerperal mastitis

The principal microorganisms that cause puerperal mastitis are the aerobic streptococci and staphylococci that form part of the normal skin flora. The diagnosis usually is made based on the characteristic clinical findings: erythema, tenderness, and warmth in an area of the breast accompanied by a purulent nipple discharge and fever and chills. The vast majority of cases can be treated with oral antibiotics on an outpatient basis. The key indications for hospitalization are severe illness, particularly in an immunocompromised patient, and suspicion of a breast abscess.2

Continue to: Antibiotic selection...

Antibiotic selection

The initial drug of choice for treatment of mastitis is dicloxacillin sodium 500 mg every 6 hours for 7 to 10 days. If the patient has a mild allergy to penicillin, the appropriate alternative is cephalexin 500 mg every 8 hours for 7 to 10 days. If the patient’s allergy to penicillin is severe, 2 alternatives are possible. One is clindamycin 300 mg twice daily for 7 to 10 days; the other is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength (800 mg/160 mg), twice daily for 7 to 10 days. The latter 2 drugs are also of great value if the patient fails to respond to initial therapy and/or infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is suspected.2 I prefer the latter agent because it is less expensive than clindamycin and is less likely to cause antibiotic-induced diarrhea.

If hospitalization is required, the drug of choice is intravenous vancomycin. The appropriate dosage is 20 mg/kg every 8 to 12 hours (maximum single dose of 2 g).2

10. Syphilis

Syphilis is caused by the spirochete bacterium, Treponema pallidum. The diagnosis can be made by clinical examination if the characteristic findings listed in TABLE 2 are present.2,17 However, most patients in our practice will have latent syphilis, and the diagnosis must be established based on serologic screening.17

Antibiotic selection

In pregnancy, the treatment of choice for syphilis is penicillin (TABLE 3).2,10,17 Only penicillin has been proven effective in treating both maternal and fetal infection. If the patient has a history of allergy to penicillin, she should undergo skin testing to determine if she is truly allergic. If hypersensitivity is confirmed, the patient should be desensitized and then treated with the appropriate regimen outlined in TABLE 3. Of interest, within a short period of time after treatment, the patient’s sensitivity to penicillin will be reestablished, and she should not be treated again with penicillin unless she undergoes another desensitization process.2,17

11. Trichomoniasis

Trichomoniasis is caused by the flagellated protozoan, Trichomonas vaginalis. The condition is characterized by a distinct yellowish-green vaginal discharge. The vaginal pH is >4.5, and motile flagellated organisms are easily visualized on saline microscopy. The vaginal panel assay also is a valuable diagnostic test.3

Antibiotic selection

The drug of choice for trichomoniasis is oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 7 days. The patient’s sexual partner(s) should be treated concurrently to prevent reinfection. Most treatment failures are due to poor compliance with therapy on the part of either the patient or her partner(s); true drug resistance is uncommon. When antibiotic resistance is strongly suspected, the patient may be treated with a single 2-g oral dose of tinidazole.2

12. Urinary tract infections

Urethritis

Acute urethritis usually is caused by C trachomatis or N gonorrhoeae. The treatment of infections with these 2 organisms is discussed above.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria and acute cystitis

Bladder infections are caused primarily by E coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Proteus species. Gram-positive cocci such as enterococci, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, and GBS are less common pathogens.18

The key diagnostic criterion for asymptomatic bacteriuria is a colony count greater than 100,000 organisms/mL of a single uropathogen on a clean-catch midstream urine specimen.18

The usual clinical manifestations of acute cystitis include frequency, urgency, hesitancy, suprapubic discomfort, and a low-grade fever. The diagnosis is most effectively confirmed by obtaining urine by catheterization and demonstrating a positive nitrite and positive leukocyte esterase reaction on dipstick examination. The finding of a urine pH of 8 or greater usually indicates an infection caused by Proteus species. When urine is obtained by catheterization, the criterion for defining a positive culture is greater than 100 colonies/mL.18

Antibiotic selection. In the first trimester, the preferred agents for treatment of a lower urinary tract infection are oral amoxicillin (875 mg twice daily) or cephalexin (500 mg every 8 hours). For an initial infection, a 3-day course of therapy usually is adequate. For a recurrent infection, a 7- to 10-day course is indicated.

Beyond the first trimester, nitrofurantoin monohydrate macrocrystals (100 mg orally twice daily) or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength (800 mg/160 mg twice daily) are the preferred agents. Unless no other oral drug is likely to be effective, these 2 drugs should be avoided in the first trimester. The former has been associated with eye, heart, and cleft defects. The latter has been associated with neural tube defects, cardiac anomalies, choanal atresia, and diaphragmatic hernia.18

Acute pyelonephritis

Acute infections of the kidney usually are caused by the aerobic gram-negative bacilli: E coli, K pneumoniae, and Proteus species. Enterococci, S saprophyticus, and GBS are less likely to cause upper tract infection as opposed to bladder infection.

The typical clinical manifestations of acute pyelonephritis include high fever and chills in association with flank pain and tenderness. The diagnosis is best confirmed by obtaining urine by catheterization and documenting the presence of a positive nitrite and leukocyte esterase reaction. Again, an elevated urine pH is indicative of an infection secondary to Proteus species. The criterion for defining a positive culture from catheterized urine is greater than 100 colonies/mL.2,18

Antibiotic selection. Patients in the first half of pregnancy who are hemodynamically stable and who show no signs of preterm labor may be treated with oral antibiotics as outpatients. The 2 drugs of choice are amoxicillin-clavulanate (875 mg twice daily for 7 to 10 days) or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole double strength (800 mg/160 mg twice daily for 7 to 10 days).

For unstable patients in the first half of pregnancy and for essentially all patients in the second half of pregnancy, parenteral treatment should be administered on an inpatient basis. My preference for treatment is ceftriaxone, 2 g intravenously every 24 hours. The drug provides excellent coverage against almost all the uropathogens. It has a convenient dosing schedule, and it usually is very well tolerated. Parenteral therapy should be continued until the patient has been afebrile and asymptomatic for 24 to 48 hours. At this point, the patient can be transitioned to one of the oral regimens listed above and managed as an outpatient. If the patient is allergic to β-lactam antibiotics, an excellent alternative is aztreonam, 2 g intravenously every 8 hours.2,18 ●

- Reeder CF, Duff P. A case of BV during pregnancy: best management approach. OBG Manag. 2021;33(2):38-42.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infection in pregnancy: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al, eds. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies, 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1145.

- Broache M, Cammarata CL, Stonebraker E, et al. Performance of a vaginal panel assay compared with the clinical diagnosis of vaginitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:853-859.

- Hiller SL, Nyirjesy P, Waldbaum AS, et al. Secnidazole treatment of bacterial vaginosis: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:379-386.

- Kirkpatrick K, Duff P. Candidiasis: the essentials of diagnosis and treatment. OBG Manag. 2020;32(8):27-29, 34.

- Ibrexafungerp (Brexafemme) for vulvovaginal candidiasis. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2021;63:141-143.

- Duff P. Prevention of infection after cesarean delivery. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;62:758-770.

- Tita AT, Szychowski JM, Boggess K, et al; for the C/SOAP Trial Consortium. Adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis for cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1231-1241.

- Harper LM, Kilgore M, Szychowski JM, et al. Economic evaluation of adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis for cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:328-334.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(RR3):1-137.

- Edwards RK, Duff P. Single additional dose postpartum therapy for women with chorioamnionitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(5 pt 1):957-961.

- Black LP, Hinson L, Duff P. Limited course of antibiotic treatment for chorioamnionitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:1102-1105.

- Duff P. Fever following cesarean delivery: what are your steps for management? OBG Manag. 2021;33(12):26-30, 35.

- St Cyr S, Barbee L, Warkowski KA, et al. Update to CDC’s treatment guidelines for gonococcal infection, 2020. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1911-1916.

- Prevention of group B streptococcal early-onset disease in newborns: ACOG committee opinion summary, number 782. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:1.

- Duff P. Preventing early-onset group B streptococcal disease in newborns. OBG Manag. 2019;31(12):26, 28-31.

- Finley TA, Duff P. Syphilis: cutting risk through primary prevention and prenatal screening. OBG Manag. 2020;32(11):20, 22-27.

- Duff P. UTIs in pregnancy: managing urethritis, asymptomatic bacteriuria, cystitis, and pyelonephritis. OBG Manag. 2022;34(1):42-46.

- Reeder CF, Duff P. A case of BV during pregnancy: best management approach. OBG Manag. 2021;33(2):38-42.

- Duff P. Maternal and perinatal infection in pregnancy: bacterial. In: Landon MB, Galan HL, Jauniaux ERM, et al, eds. Gabbe’s Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies, 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021:1124-1145.

- Broache M, Cammarata CL, Stonebraker E, et al. Performance of a vaginal panel assay compared with the clinical diagnosis of vaginitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:853-859.

- Hiller SL, Nyirjesy P, Waldbaum AS, et al. Secnidazole treatment of bacterial vaginosis: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:379-386.

- Kirkpatrick K, Duff P. Candidiasis: the essentials of diagnosis and treatment. OBG Manag. 2020;32(8):27-29, 34.

- Ibrexafungerp (Brexafemme) for vulvovaginal candidiasis. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2021;63:141-143.

- Duff P. Prevention of infection after cesarean delivery. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;62:758-770.

- Tita AT, Szychowski JM, Boggess K, et al; for the C/SOAP Trial Consortium. Adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis for cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1231-1241.

- Harper LM, Kilgore M, Szychowski JM, et al. Economic evaluation of adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis for cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:328-334.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(RR3):1-137.

- Edwards RK, Duff P. Single additional dose postpartum therapy for women with chorioamnionitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(5 pt 1):957-961.

- Black LP, Hinson L, Duff P. Limited course of antibiotic treatment for chorioamnionitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:1102-1105.

- Duff P. Fever following cesarean delivery: what are your steps for management? OBG Manag. 2021;33(12):26-30, 35.

- St Cyr S, Barbee L, Warkowski KA, et al. Update to CDC’s treatment guidelines for gonococcal infection, 2020. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1911-1916.

- Prevention of group B streptococcal early-onset disease in newborns: ACOG committee opinion summary, number 782. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:1.

- Duff P. Preventing early-onset group B streptococcal disease in newborns. OBG Manag. 2019;31(12):26, 28-31.

- Finley TA, Duff P. Syphilis: cutting risk through primary prevention and prenatal screening. OBG Manag. 2020;32(11):20, 22-27.

- Duff P. UTIs in pregnancy: managing urethritis, asymptomatic bacteriuria, cystitis, and pyelonephritis. OBG Manag. 2022;34(1):42-46.

Commonly used antibiotics in ObGyn practice

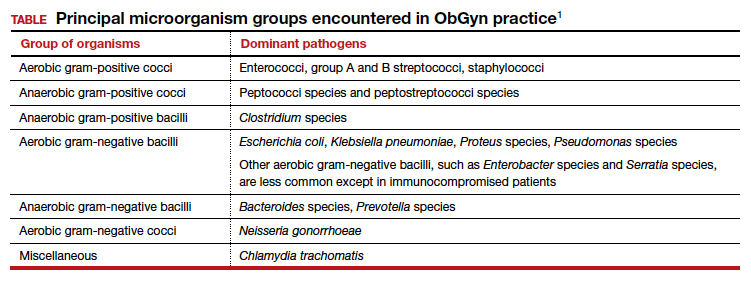

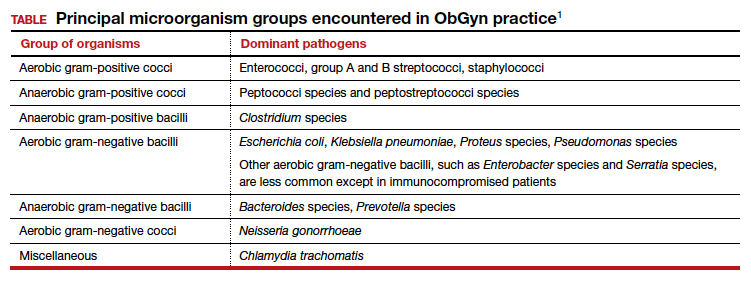

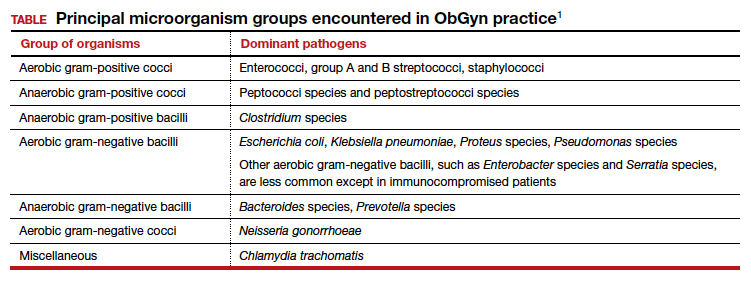

In this article, I provide a simplified, practical review of the principal antibiotics that we use on a daily basis to treat bacterial infections. The antibiotics are listed in alphabetical order, either individually or by group. I focus first on the mechanism of action and spectrum of activity of the drugs used against the usual pelvic pathogens (TABLE).1 I then review their principal adverse effects, relative cost (categorized as low, intermediate, and high), and the key indications for these drugs in obstetrics and gynecology. In a forthcoming 2-part companion article, I will review how to select specific antibiotics and their dosing regimens for the most commonly encountered bacterial infections in our clinical practice.

Aminoglycoside antibiotics

The aminoglycosides include amikacin, gentamicin, plazomicin, and tobramycin.2,3 The 2 agents most commonly used in our specialty are amikacin and gentamicin. The drugs may be administered intramuscularly or intravenously, and they specifically target aerobic gram-negative bacilli. They also provide coverage against staphylococci and gonococci. Ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity are their principal adverse effects.

Aminoglycosides are used primarily as single agents to treat pyelonephritis caused by highly resistant bacteria and in combination with agents such as clindamycin and metronidazole to treat polymicrobial infections, including chorioamnionitis, puerperal endometritis, and pelvic inflammatory disease. Of all the aminoglycosides, gentamicin is clearly the least expensive.

Carbapenems

The original carbapenem widely introduced into clinical practice was imipenem-cilastatin. Imipenem, the active antibiotic, inhibits bacterial cell wall synthesis. Cilastatin inhibits renal dehydropeptidase I and, thereby, slows the metabolism of imipenem by the kidney. Other carbapenems include meropenem and ertapenem.

The carbapenems have the widest spectrum of activity against the pelvic pathogens of any antibiotic. They provide excellent coverage of aerobic and anaerobic gram-positive cocci and aerobic and anaerobic gram-negative bacilli. They do not cover methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and the enterococci very well.

A major adverse effect of the carbapenems is an allergic reaction, including anaphylaxis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and there is some minimal cross-sensitivity with the β-lactam antibiotics. Other important, but fortunately rare, adverse effects include neurotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, and Clostridium difficile colitis.4

As a group, the carbapenems are relatively more expensive than most other agents. Their principal application in our specialty is for single-agent treatment of serious polymicrobial infections, such as puerperal endometritis, pelvic cellulitis, and pelvic abscess, especially in patients who have a contraindication to the use of combination antibiotic regimens that include an aminoglycoside.1,2

Cephalosporins

The cephalosporins are β-lactam antibiotics that act by disrupting the synthesis of the bacterial cell wall. They may be administered orally, intramuscularly, and intravenously. The most common adverse effects associated with these agents are an allergic reaction, which can range from a mild rash to anaphylaxis and the Stevens-Johnson syndrome; central nervous system toxicity; and antibiotic-induced diarrhea, including C difficile colitis.1,2,4

This group of antibiotics can be confusing because it includes so many agents, and their spectrum of activity varies. I find it helpful to think about the coverage of these agents as limited spectrum versus intermediate spectrum versus extended spectrum.

The limited-spectrum cephalosporin prototypes are cephalexin (oral administration) and cefazolin (parenteral administration). This group of cephalosporins provides excellent coverage of aerobic and anaerobic gram-positive cocci. They are excellent against staphylococci, except for MRSA. Coverage is moderate for aerobic gram-negative bacilli but only limited for anaerobic gram-negative bacilli. They do not cover the enterococci. In our specialty, their principal application is for treatment of mastitis, urinary tract infections (UTIs), and wound infections and for prophylaxis against group B streptococcus (GBS) infection and post-cesarean infection.2,5 The cost of these drugs is relatively low.

The prototypes of the intermediate-spectrum cephalosporins are cefixime (oral) and ceftriaxone (parenteral). Both drugs have strong activity against aerobic and anaerobic streptococci, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, most aerobic gram-negative bacilli, and Treponema pallidum (principally, ceftriaxone). They are not consistently effective against staphylococci, particularly MRSA, and enterococci. Their key indications in obstetrics and gynecology are treatment of gonorrhea, syphilis (in penicillin-allergic patients), and acute pyelonephritis. Compared with the limited-spectrum cephalosporins, these antibiotics are moderately expensive.1,2

The 3 extended-spectrum cephalosporins used most commonly in our specialty are cefepime, cefotetan, and cefoxitin. These agents are administered intramuscularly and intravenously, and they provide very good coverage against aerobic and anaerobic gram-positive cocci, with the exception of staphylococci and enterococci. They have very good coverage against most gram-negative aerobic bacilli and excellent coverage against anerobic microorganisms. Their primary application in our specialty is for single-agent treatment of polymicrobial infections, such as puerperal endometritis and pelvic cellulitis. When used in combination with doxycycline, they are valuable in treating pelvic inflammatory disease. These drugs are more expensive than the limited-spectrum or intermediate-spectrum agents. They should not be used routinely as prophylaxis for pelvic surgery.1,2,5

Continue to: Fluorinated quinolones...

Fluorinated quinolones

The fluorinated quinolones include several agents, but the 3 most commonly used in our specialty are ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, and levofloxacin. All 3 drugs can be administered orally; ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin also are available in intravenous formulations. These drugs interfere with bacterial protein synthesis by targeting DNA gyrase, an enzyme that introduces negative supertwists into DNA and separates interlocked DNA molecules.

These drugs provide excellent coverage against gram-negative bacilli, including Haemophilus influenzae; gram-negative cocci, such as N gonorrhoeae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Moraxella catarrhalis; and many staphylococci species. Levofloxacin, but not the other 2 drugs, provides moderate coverage against anaerobes. Ofloxacin and levofloxacin are active against chlamydia. Levofloxacin also covers the mycoplasma organisms that are responsible for atypical pneumonia.

As a group, the fluorinated quinolones are moderately expensive. The most likely adverse effects with these agents are gastrointestinal (GI) upset, headache, agitation, and sleep disturbance. Allergic reactions are rare. These drugs are of primary value in our specialty in treating gonorrhea, chlamydia, complicated UTIs, and respiratory tract infections.1,2,6

The penicillins

Penicillin

Penicillin, a β-lactam antibiotic, was one of the first antibiotics developed and employed in clinical practice. It may be administered orally, intramuscularly, and intravenously. Penicillin exerts its effect by interfering with bacterial cell wall synthesis. Its principal spectrum of activity is against aerobic streptococci, such as group A and B streptococcus; most anaerobic gram-positive cocci that are present in the vaginal flora; some anaerobic gram-negative bacilli; and T pallidum. Penicillin is not effective against the majority of staphylococci species, enterococci, or aerobic gram-negative bacilli, such as Escherichia coli.

Penicillin’s major adverse effect is an allergic reaction, experienced by less than 10% of recipients.7 Most reactions are mild and are characterized by a morbilliform skin rash. However, some reactions are severe and take the form of an urticarial skin eruption, laryngospasm, bronchospasm, and overt anaphylaxis. The cost of both oral and parenteral penicillin formulations is very low. In obstetrics and gynecology, penicillin is used primarily for the treatment of group A and B streptococci infections, clostridial infections, and syphilis.1,2

Ampicillin and amoxicillin

The β-lactam antibiotics ampicillin and amoxicillin also act by interfering with bacterial cell wall synthesis. Amoxicillin is administered orally; ampicillin may be administered orally, intramuscularly, and intravenously. Their spectrum of activity includes group A and B streptococci, enterococci, most anaerobic gram-positive cocci, some anaerobic gram-negative bacilli, many aerobic gram-negative bacilli, and clostridial organisms.

Like penicillin, ampicillin and amoxicillin may cause allergic reactions that range from mild rashes to anaphylaxis. Unlike the more narrow-spectrum penicillin, they may cause antibiotic-associated diarrhea, including C difficile colitis,4 and they may eliminate part of the normal vaginal flora and stimulate an overgrowth of yeast organisms in the vagina. The cost of ampicillin and amoxicillin is very low. These 2 agents are used primarily for treatment of group A and B streptococci infections and some UTIs, particularly those caused by enterococci.1,2

Dicloxacillin sodium