User login

Appropriate Analgesic Use in the Emergency Department

Pain, one of the most common reasons patients present to the ED, may be a primary complaint or a warning sign encouraging further evaluation. The decision to treat pain is one of the most frequent therapeutic decisions made by emergency physicians (EPs) and involves a variety of options and considerations. Moreover, the decision of how to treat pain similarly encompasses a wide selection of variables, including etiology and severity of the pain; intravenous (IV) access; medication allergies; renal function; alcohol use; rapidity of onset; patients’ vital signs; patient preference; and mode of transport upon discharge. Given all of these considerations, there is no perfect analgesic to suit every circumstance. Rather, EPs must tailor their analgesic selection to the individual clinical situation and patient.

The literature over the past 20 years is replete with studies demonstrating the undertreatment or inadequate treatment of pain in the ED.1-5 Often referred to as oligoanalgesia,6 contributing factors include physician concerns regarding adverse side effects, secondary gain, and drug addiction. In addition, the increasing pressure placed on EPs to diagnose and dispose patients quickly likely relegates pain control to a secondary concern.

Further complicating the issue, physicians’ own prejudices and perceptions appear to influence their analgesic prescription practice. For example, several studies have demonstrated that black patients do not receive prescriptions for analgesics similar to those written for white patients in general, and particularly not for opioid analgesics. In a meta-analysis of pain treatment disparity studies, blacks were 22% less likely than whites to receive any analgesics, and 29% less likely than whites to receive opioid treatment for the same type of painful conditions.7 Likewise, Hispanic/Latino patients were also 22% less likely than their white counterparts to receive opioid treatment for similar pain.7 Physicians must keep these common biases in mind when treating patients for pain.

The administration of analgesics and the prescription habits of physicians has never been under greater scrutiny. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has benchmarked “median time to pain management for long bone fractures” as a core measure, possibly affecting hospital reimbursement rates. Similarly, every patient satisfaction survey specifically inquires about the timeliness and adequacy of pain control. At the same time, though, the increasing problem of prescription opioid abuse has become the nation’s fastest growing drug problem. In 2013, prescription drug abuse was second only to marijuana as the most abused drug category.8 Contributing to this problem are the frequency and ease with which many physicians prescribe opioids. From 1997 to 2007, the milligram-per-person use of prescription opioids in the United States increased from 74 mg per year to 369 mg per year—an increase of 402%.9 As a result, some legislators are now calling for mandatory educational sessions for any physician prescribing medications containing opioids.

Though there are many classes of medications used to treat pain, and numerous individual drugs within each class, this article focuses on several of the more commonly prescribed medications in the ED, including their mechanisms of action, advantages, and disadvantages. The management of pediatric pain and procedural sedation and analgesia are not discussed in this review, as each of these topics deserves a separate detailed discussion.

Recognizing and Quantifying Pain

The first step in treating pain appropriately is recognition. Physicians must specifically inquire about pain and not rely solely on a patient’s unprompted complaint. Several pain scales exist, including the Faces Pain Scale (ie, pictorial representation of a smiling face on one end indicating “no pain” to a frowning face on the opposite end); the verbal quantitative scale or numerical rating scale (ie, “how would you rate your pain on a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 the worst pain ever?”); and the visual analog scale (ie, a 10-cm linear scale marked at one end with “no pain” and “worst pain imaginable” at the opposite end).10,11 Probably the most commonly used scale in the ED is some variation of the numerical rating scale (NRS).1

Each of these scales has its own advantages and disadvantages, but the important point is that patients are given the opportunity to express the type and degree of pain to the healthcare provider. In addition, a pain scale provides a starting point against which the practitioner (or later practitioners) can determine the success (or failure) of a pain treatment strategy.

Three-Step Ladder

In 1996, the World Health Organization developed a three-step analgesic ladder to guide the management of cancer pain.12 Its use has been expanded over time to include treating pain of noncancer etiology. Mild pain (NRS of 1 to 3) is considered Step 1; moderate pain (NRS 4 to 6) is considered Step 2; and severe pain (NRS 7 to 10) is Step 3. For Step 1 (mild pain), acetaminophen or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) is recommended. For Step 2 (moderate pain), a weak opioid (ie, codeine or hydrocodone) with or without acetaminophen or an NSAID is recommended. Finally, for Step 3 (severe pain), a strong opioid such as morphine or hydromorphone is recommended.

Again, the purpose of the ladder is not to provide a strict protocol for adherence, but rather to provide a reasonable starting point as a guide to the clinician. The key to its successful use is reassessment of the patient to determine if adequate pain relief is achieved.

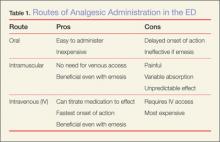

Routes of Administration

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen, the active ingredient in Tylenol, was first marketed in the United States in 1955 as an antipyretic and pain reliever.13 It is a synthetic centrally acting analgesic that is metabolized in the liver. Acetaminophen has been used alone or in combination in hundreds of formulations to treat a wide variety of pain and fever-related conditions. In the ED setting, acetaminophen is frequently used as an antipyretic and—either alone or in combination with opioids—for oral pain control.

Acetaminophen is very well tolerated by most patients, with minimal gastrointestinal (GI) distress. It is inexpensive, and the wide variety of formulations (eg, liquid, tablet, suppository) make it useful in a number of clinical scenarios. Acetaminophen is generally considered to be the only nonopioid analgesic that is safe in pregnancy,14 and it has no sedative or addictive effects.

There are, however, some disadvantages to using acetaminophen. Concerns about its safety and accidental overdose have recently led to the introduction of a 4,000-mg maximum daily dose recommendation15 and heightened concern over using multiple medications containing acetaminophen. In January 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration recommended that no combination medication contain more than 325 mg of acetaminophen because of the risk of toxicity when multiple drugs containing acetaminophen are consumed.

In addition to concerns of inadvertent overdose, another disadvantage of acetaminophen is that while it may be an effective antipyretic and analgesic, it has little or no anti-inflammatory properties. Therefore, in cases requiring an anti-inflammatory agent, an NSAID, when appropriate, would be the more effective option.

NSAIDs

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs function by inhibiting prostaglandin production in the cyclooxygenase 1 and 2 (COX-1 and COX-2) pathways. Ibuprofen, indomethacin, ketorolac, naproxen, and other NSAIDs are chiefly utilized to control pain, inflammation, and fever via the oral route. As production of various prostaglandins via the COX-2 pathway is thought to contribute to fever, inflammation, and pain, inhibition of this pathway by NSAIDs can help alleviate these symptoms. The COX-1 pathway contributes many factors important to the protection and health of the GI tract, and inhibition of this pathway can lead to GI distress and damage. Unfortunately, the most commonly used and available NSAIDs inhibit both COX pathways simultaneously, and in doing so, prompt the GI symptoms which are the most common adverse side effects of therapy. In addition to GI effects of the COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitors, there are also concerns over the associated antiplatelet effects in patients undergoing surgery or potentially suffering from occult or intracranial bleeding.13

Ibuprofen

This is the most commonly used NSAID in the United States and is available without a prescription. Ibuprofen is typically used to treat mild-to-moderate pain from a musculoskeletal or inflammatory source. As an oral nonprescription medication, it can be used advantageously to treat acute pain in the ED and continued in the outpatient setting. Ibuprofen is neither sedating nor addicting, with a rapid onset of action and a plasma half-life of approximately 2 hours.13 However, there is a dose-dependent feature which allows large doses (eg, 800 mg) to be spaced-out every 8 hours while maintaining effective analgesia. Typical doses range from 200 mg to 800 mg orally every 6 to 8 hours, with a maximum dose of 3.2 g/d. Patients should be instructed to take each dose with a meal or snack to help alleviate GI side effects.

The greatest advantage of ibuprofen and other NSAIDs is their effect on inflammation and the ability to treat the inflammatory cause of pain—not just the symptom. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are well tolerated by most patients and can be obtained without prescription at low cost. Additionally, doses of ibuprofen and acetaminophen can be alternated.

Ketorolac

Often marketed as Toradol, ketorolac is a powerful NSAID available in IV, IM, and oral formulations. Typical doses are 30 mg IV, 60 mg IM, or 10 mg orally every 4 to 6 hours (maximum of 40 mg/d). The basic pharmacology and mechanism of action of ketorolac are similar to ibuprofen. Though ketorolac is useful to treat more severe pain, it should only be used for short-term management of pain (ie, 5 days or less). Ketorolac is often used for postoperative pain, but also is helpful for pain control in patients using opioids. It has been shown to be effective for acute renal colic and can also provide relief for migraine headaches.16,17 In a direct comparison between ketorolac and meperidine (Demerol) for patients suffering from renal stones, ketorolac was found to be more effective and provide longer lasting pain relief.18

The major concern regarding ketorolac relates to potential renal toxicity, and thus caution should be undertaken in prescribing it to patients with known or suspected renal disease. Although this risk is associated with even a single dose, multiple doses increase the danger and therefore should be avoided.

Ketorolac should also be used with caution in patients with asthma. As a subset of asthma patients will experience severe bronchospasm after NSAID administration, clinicians should always determine whether a patient can tolerate NSAIDs.

Renal Toxicity and GI Effects

Concerns over renal toxicity and potential GI distress are the chief disadvantages of NSAID use. While renal toxicity has been reported in patients without pre-existing kidney dysfunction, it is of much greater concern in patients with pre-existing renal disease or decreased glomerular filtration rate. For this reason, care must be exercised when prescribing NSAIDS to elderly patients, patients with diabetes mellitus, or patients with hypertension (or even worse, a combination of these). Prolonged use of NSAIDs can also cause upper GI bleeding. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are contraindicated in pregnant patients.

Opioid analgesics

Morphine

Morphine is the prototypical compound in the opioid class, and has been utilized for more than two centuries since its isolation in 1804.19 Other opioid compounds include codeine, hydrocodone, oxycodone, morphine, and hydromorphone, which represent different functional groups substituted onto the base morphine molecule. All share similar pharmacology, differing primarily only in potency. The onset of action for codeine, hydrocodone, and oxycodone is 30 to 60 minutes when taken orally, with a peak time of 60 to 90 minutes. Codeine and hydrocodone are at the weak-end of the spectrum (Step 2 medications), while morphine and hydromorphone are more potent (Step 3 medications). The majority of opioids and their metabolites are primarily excreted renally (90%-95%).20 Therefore, care must be exercised regarding dosing and frequency when used in patients with renal insufficiency or disease.

Morphine has several features that make it an attractive analgesic for use in the ED. The ability to administer morphine via IV, IM, subcutaneous, or oral route; its quick onset of action; and safety profile are all advantageous. The onset of action is 5 to 10 minutes when given IV. For oral administration, it is 30 to 60 minutes (similar to the other opioids discussed) and can be given as a tablet or syrup.

Morphine decreases the severity of pain, with an apparent increase in tolerance for any remaining discomfort. The potency and central action of morphine make it ideal for managing moderate and severe pain.

As with other analgesics, morphine and its related compounds have associated drawbacks, of which respiratory depression is the most feared, though this is uncommon at therapeutic doses. The respiratory depressant effect is more pronounced in patients with underlying lung disease, depressed mental status, or concurrent use of sedating medication (eg, benzodiazepines).

Another disadvantage to morphine is that it can cause hypotension, limiting its use in certain clinical situations. Repeated or prolonged use may cause slowing or complete arrest of peristaltic waves in the GI tract, which can lead to significant constipation. Pruritus and nausea are two other frequently reported side effects and may necessitate, respectively, coadministration of diphenhydramine (eg, Benadryl) or an antiemetic (eg, Phenergan or Zofran). As an opioid, morphine is potentially addictive, though it is generally thought to require significant intake over several weeks before such problems arise.

The sedation caused by morphine is also of concern, as patients who are under its influence immediately following discharge cannot safely drive, and may actually not be safe to walk or even utilize public transportation. This concern can be lessened by verifying the patient’s mode of transport prior to administration of the medication, ensuring that patients are not overly sedated at the time of discharge and, as much as possible, accompanied home by an adult relative or friend. In comparison to other frequently used opioids, several features can be considered. The duration of action for codeine, hydromorphone, and morphine is similar at 3 to 5 hours.

Hydromorphone

Hydromorphone (Dilaudid) is approximately seven times more potent than morphine, but otherwise very similar. It is frequently the IV opioid of choice for severe pain and also appears to cause pruritus less frequently than morphine. Hydromorphone has a rapid onset of action (1-5 minutes IV; 15-30 minutes orally) and can be titrated to effect when given via the IV route, making it an ideal agent for the pain associated with long bone or pelvic fractures, vasoocclusive crises in patients with sickle cell disease, and renal colic. The oral formulation of hydromorphone can be utilized for severe pain in the appropriate patient population, usually at a dose of 2 to 4 mg every 4 hours.

Codeine

Codeine is frequently prescribed in combination with acetaminophen in a product marketed as Tylenol #3 for mild-to-moderate pain. Because codeine is metabolized in the liver to morphine, it is contraindicated in patients with morphine allergy. Also, the clinician must be aware that codeine is ineffective in 7% to 10% of the population due to an enzyme deficiency.

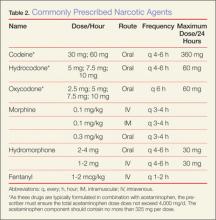

Hydrocodone and oxycodone, which are often combined with acetaminophen and marketed respectively as Vicodin and Percocet, are two additional commonly used compounds in the oral treatment of moderate-to-severe pain. There are numerous preparations containing various strengths of both the opioid and acetaminophen components. Utilizing these medications as initial pain control in the ED can be beneficial, as therapy can be continued as an outpatient. Table 2 provides dosing and frequency information, but the clinician must also be aware of the total amount of acetaminophen administered, especially when being used in conjunction with other medications containing acetaminophen.

Tramadol

Tramadol (Ultram), another oral analgesic with opioid properties, affects several neurotransmitters and is less reliant on the opioid receptors compared to the opioid compounds described above. It is used to treat moderate-to-severe pain and can be considered another option along with codeine, hydrocodone, and oxycodone for oral pain control. Although the complete mechanism of action for tramadol is poorly understood, it appears to be effective in patients who do not respond well to pure opioids, and in patients with neuropathic pain or persistent pain of unclear etiology (eg, fibromyalgia).19 Because of its limited interaction with opioid receptors, tramadol has less potential for abuse and addiction than the opioids. It is also available in several combinations with acetaminophen or ibuprofen.

Conclusion

The ideal medication for treating pain in the ED is one that is effective, easy to administer, and has minimal adverse or residual effects. Generally, the least potent medication that will control pain should be chosen initially. When treating minor traumatic or musculoskeletal pain, initiating pain control with oral medication in the ED may provide patients with relief during imaging or splinting, and help control pain until they can fill outpatient prescriptions. All of the medications discussed in this article can be given in the oral form. However, IV usage may be appropriate when there is need for rapid onset of action, to titrate the medication, or for ease of administration in patients who are vomiting or unable to take anything orally.

When prescribing analgesics for pain control after discharge, the clinician must consider potential relative and absolute contraindications. For acetaminophen, liver toxicity is the major concern, and care must be taken not to exceed recommended daily dosing limits with the multitude of available products containing acetaminophen. Physicians should avoid recommending or prescribing acetaminophen to patients with liver disease (ie, cirrhosis) or habitual alcohol abuse.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen and naproxen carry the risk of renal damage, as well as concerns about antiplatelet activity. Because of the tendency for renal function to decline with age, caution must be exercised in using these compounds in older patients and those with preexisting renal dysfunction.

Opioid-containing medications are known for their potency in pain control, but also for their side effects. The most common side effect involves the GI tract, with nausea, vomiting, and constipation. The most dangerous side effect of opioids is respiratory depression; fortunately, this is rarely seen with therapeutic doses. However, somnolence and decreased coordination are significant concerns when prescribing opioids to elderly patients or those already at risk for falls.

There is no ideal single medication to treat all types of pain or situations. However, the choice of medication begins with a decision by the EP to treat pain. Utilizing a stepwise approach, oral medication will usually be effective for mild pain, but IV narcotics will probably be required for severe pain. Frequent reassessment of the patient is critically important for successful pain management in the ED.

Dr Byers is an emergency physician at the Presbyterian Medical Group, department of emergency medicine, Presbyterian Healthcare Services, Albuquerque, New Mexico. Dr Counselman is a distinguished professor of emergency medicine and chairman, department of emergency medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School and Emergency Physicians of Tidewater, Norfolk, Virginia. He is also associate editor-in-chief of the Emergency Medicine editorial board.

- Todd KH. Pain assessment instruments for use in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23(2):285-295.

- Cordell WH, Keene KK, Giles BK, Jones JB, Jones JH, Brizendine EJ. The high prevalence of pain in emergency medical care. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20(3):165-169.

- Tcherny-Lessenot S, Karwowski-Soulié F, Lamarche-Vadel A, Ginsburg C, Brunet F, Vidal-Trecan G. Management and relief of pain in an emergency department from the adult patients’ perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25(6):539-546.

- Karwowski-Soulié F, Lessenot-Tcherny S, Lamarche-Vadel A, et al. Pain in an emergency department: an audit. Eur J Emerg Med. 2006;13(4):218-224.

- Fosnocht DE, Swanson ER, Barton ED. Changing attitudes about pain and pain control in emergency medicine. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23(2):297-306.

- Wilson JE, Pendelton JM. Oligoanalgesia in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 1989;7(6):620-623.

- Meghani SH, Byun E, Gallagher RM. Time to take stock: a meta-analysis and systemic review of analgesic treatment disparities for pain in the United States. Pain Med. 2012;13(2):150-174.

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schutenberg JE; The University of Michigan Institute for Social Research. Monitoring the future: 2013 overview key findings of on adolescent drug use. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2013.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2014.

- Manchikanti L, Fellow B, Ailinani H, Pampati V. Therapeutic use, abuse, and nonmedical use of opioids: a ten year perspective. Pain Physician. 2010;13(5):401-435.

- Silka PA, Roth MM, Moreno G, Merrill L, Geiderman JM. Pain scores improve analgesic administration patterns for trauma patients in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(3):264-270.

- Nelson BP, Cohen D, Lander O, Crawford N, Viccellio AW, Singer AJ. Mandated pain scales improve frequency of ED analgesic administration. Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22(7):582-585.

- World Health Organization. Cancer pain relief with a guide to opioid availability 2nd ed. 1996. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/9241544821.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2014.

- Grosser T, Smyth EM, FitzGerald GA. Anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, and analgesic agents: pharmacotherapy of gout. In: Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollman BC, eds. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12th ed. China: The McGraw Hill Companies; 2011:959-1004.

- Scialli AR, Ang R, Breitmeyer J, Royal MA. A review of the literature on the effects of acetaminophen on pregnancy outcome. Reprod Toxicol. 2010;30(4):495-507.

- Schilling A, Corey R, Leonard M, Eghtesad B. Acetaminophen: old drug, new warnings. Cleveland Clin J Med. 2010;77(1):19-27.

- Shrestha M, Singh R, Moreden J, Hayes JE. Ketorolac vs chlorpromazine in the treatment of acute migraine without aura. A prospective, randomized, double-blind trial. Arch Intern Med.1996;156(15):1725-1728.

- Turkewitz LJ, Casaly JS, Dawson GA, Wirth O, Hurst RJ, Gillette PL. Self-administration of parenteral ketorolac tromethamine for head pain. Headache. 1992;32(9):452-454.

- Larkin GL, Peacock WF 4th, Pearl SM, Blair GA, D’Amico F. Efficacy of ketorolac tromethamine versus meperidine in the ED treatment of acute renal colic. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17(1):6-10.

- Yaksh TL, Wallace MS. Opiods, analgesia and pain management. In: Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollman BC, eds. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12th ed. China: The McGraw Hill Companies; 2011:481-526.

- DeSandre PL, Quest TE. Management of cancer-related pain. Hematol Oncol Clin N Am. 2010;24(3):643-658.

Pain, one of the most common reasons patients present to the ED, may be a primary complaint or a warning sign encouraging further evaluation. The decision to treat pain is one of the most frequent therapeutic decisions made by emergency physicians (EPs) and involves a variety of options and considerations. Moreover, the decision of how to treat pain similarly encompasses a wide selection of variables, including etiology and severity of the pain; intravenous (IV) access; medication allergies; renal function; alcohol use; rapidity of onset; patients’ vital signs; patient preference; and mode of transport upon discharge. Given all of these considerations, there is no perfect analgesic to suit every circumstance. Rather, EPs must tailor their analgesic selection to the individual clinical situation and patient.

The literature over the past 20 years is replete with studies demonstrating the undertreatment or inadequate treatment of pain in the ED.1-5 Often referred to as oligoanalgesia,6 contributing factors include physician concerns regarding adverse side effects, secondary gain, and drug addiction. In addition, the increasing pressure placed on EPs to diagnose and dispose patients quickly likely relegates pain control to a secondary concern.

Further complicating the issue, physicians’ own prejudices and perceptions appear to influence their analgesic prescription practice. For example, several studies have demonstrated that black patients do not receive prescriptions for analgesics similar to those written for white patients in general, and particularly not for opioid analgesics. In a meta-analysis of pain treatment disparity studies, blacks were 22% less likely than whites to receive any analgesics, and 29% less likely than whites to receive opioid treatment for the same type of painful conditions.7 Likewise, Hispanic/Latino patients were also 22% less likely than their white counterparts to receive opioid treatment for similar pain.7 Physicians must keep these common biases in mind when treating patients for pain.

The administration of analgesics and the prescription habits of physicians has never been under greater scrutiny. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has benchmarked “median time to pain management for long bone fractures” as a core measure, possibly affecting hospital reimbursement rates. Similarly, every patient satisfaction survey specifically inquires about the timeliness and adequacy of pain control. At the same time, though, the increasing problem of prescription opioid abuse has become the nation’s fastest growing drug problem. In 2013, prescription drug abuse was second only to marijuana as the most abused drug category.8 Contributing to this problem are the frequency and ease with which many physicians prescribe opioids. From 1997 to 2007, the milligram-per-person use of prescription opioids in the United States increased from 74 mg per year to 369 mg per year—an increase of 402%.9 As a result, some legislators are now calling for mandatory educational sessions for any physician prescribing medications containing opioids.

Though there are many classes of medications used to treat pain, and numerous individual drugs within each class, this article focuses on several of the more commonly prescribed medications in the ED, including their mechanisms of action, advantages, and disadvantages. The management of pediatric pain and procedural sedation and analgesia are not discussed in this review, as each of these topics deserves a separate detailed discussion.

Recognizing and Quantifying Pain

The first step in treating pain appropriately is recognition. Physicians must specifically inquire about pain and not rely solely on a patient’s unprompted complaint. Several pain scales exist, including the Faces Pain Scale (ie, pictorial representation of a smiling face on one end indicating “no pain” to a frowning face on the opposite end); the verbal quantitative scale or numerical rating scale (ie, “how would you rate your pain on a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 the worst pain ever?”); and the visual analog scale (ie, a 10-cm linear scale marked at one end with “no pain” and “worst pain imaginable” at the opposite end).10,11 Probably the most commonly used scale in the ED is some variation of the numerical rating scale (NRS).1

Each of these scales has its own advantages and disadvantages, but the important point is that patients are given the opportunity to express the type and degree of pain to the healthcare provider. In addition, a pain scale provides a starting point against which the practitioner (or later practitioners) can determine the success (or failure) of a pain treatment strategy.

Three-Step Ladder

In 1996, the World Health Organization developed a three-step analgesic ladder to guide the management of cancer pain.12 Its use has been expanded over time to include treating pain of noncancer etiology. Mild pain (NRS of 1 to 3) is considered Step 1; moderate pain (NRS 4 to 6) is considered Step 2; and severe pain (NRS 7 to 10) is Step 3. For Step 1 (mild pain), acetaminophen or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) is recommended. For Step 2 (moderate pain), a weak opioid (ie, codeine or hydrocodone) with or without acetaminophen or an NSAID is recommended. Finally, for Step 3 (severe pain), a strong opioid such as morphine or hydromorphone is recommended.

Again, the purpose of the ladder is not to provide a strict protocol for adherence, but rather to provide a reasonable starting point as a guide to the clinician. The key to its successful use is reassessment of the patient to determine if adequate pain relief is achieved.

Routes of Administration

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen, the active ingredient in Tylenol, was first marketed in the United States in 1955 as an antipyretic and pain reliever.13 It is a synthetic centrally acting analgesic that is metabolized in the liver. Acetaminophen has been used alone or in combination in hundreds of formulations to treat a wide variety of pain and fever-related conditions. In the ED setting, acetaminophen is frequently used as an antipyretic and—either alone or in combination with opioids—for oral pain control.

Acetaminophen is very well tolerated by most patients, with minimal gastrointestinal (GI) distress. It is inexpensive, and the wide variety of formulations (eg, liquid, tablet, suppository) make it useful in a number of clinical scenarios. Acetaminophen is generally considered to be the only nonopioid analgesic that is safe in pregnancy,14 and it has no sedative or addictive effects.

There are, however, some disadvantages to using acetaminophen. Concerns about its safety and accidental overdose have recently led to the introduction of a 4,000-mg maximum daily dose recommendation15 and heightened concern over using multiple medications containing acetaminophen. In January 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration recommended that no combination medication contain more than 325 mg of acetaminophen because of the risk of toxicity when multiple drugs containing acetaminophen are consumed.

In addition to concerns of inadvertent overdose, another disadvantage of acetaminophen is that while it may be an effective antipyretic and analgesic, it has little or no anti-inflammatory properties. Therefore, in cases requiring an anti-inflammatory agent, an NSAID, when appropriate, would be the more effective option.

NSAIDs

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs function by inhibiting prostaglandin production in the cyclooxygenase 1 and 2 (COX-1 and COX-2) pathways. Ibuprofen, indomethacin, ketorolac, naproxen, and other NSAIDs are chiefly utilized to control pain, inflammation, and fever via the oral route. As production of various prostaglandins via the COX-2 pathway is thought to contribute to fever, inflammation, and pain, inhibition of this pathway by NSAIDs can help alleviate these symptoms. The COX-1 pathway contributes many factors important to the protection and health of the GI tract, and inhibition of this pathway can lead to GI distress and damage. Unfortunately, the most commonly used and available NSAIDs inhibit both COX pathways simultaneously, and in doing so, prompt the GI symptoms which are the most common adverse side effects of therapy. In addition to GI effects of the COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitors, there are also concerns over the associated antiplatelet effects in patients undergoing surgery or potentially suffering from occult or intracranial bleeding.13

Ibuprofen

This is the most commonly used NSAID in the United States and is available without a prescription. Ibuprofen is typically used to treat mild-to-moderate pain from a musculoskeletal or inflammatory source. As an oral nonprescription medication, it can be used advantageously to treat acute pain in the ED and continued in the outpatient setting. Ibuprofen is neither sedating nor addicting, with a rapid onset of action and a plasma half-life of approximately 2 hours.13 However, there is a dose-dependent feature which allows large doses (eg, 800 mg) to be spaced-out every 8 hours while maintaining effective analgesia. Typical doses range from 200 mg to 800 mg orally every 6 to 8 hours, with a maximum dose of 3.2 g/d. Patients should be instructed to take each dose with a meal or snack to help alleviate GI side effects.

The greatest advantage of ibuprofen and other NSAIDs is their effect on inflammation and the ability to treat the inflammatory cause of pain—not just the symptom. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are well tolerated by most patients and can be obtained without prescription at low cost. Additionally, doses of ibuprofen and acetaminophen can be alternated.

Ketorolac

Often marketed as Toradol, ketorolac is a powerful NSAID available in IV, IM, and oral formulations. Typical doses are 30 mg IV, 60 mg IM, or 10 mg orally every 4 to 6 hours (maximum of 40 mg/d). The basic pharmacology and mechanism of action of ketorolac are similar to ibuprofen. Though ketorolac is useful to treat more severe pain, it should only be used for short-term management of pain (ie, 5 days or less). Ketorolac is often used for postoperative pain, but also is helpful for pain control in patients using opioids. It has been shown to be effective for acute renal colic and can also provide relief for migraine headaches.16,17 In a direct comparison between ketorolac and meperidine (Demerol) for patients suffering from renal stones, ketorolac was found to be more effective and provide longer lasting pain relief.18

The major concern regarding ketorolac relates to potential renal toxicity, and thus caution should be undertaken in prescribing it to patients with known or suspected renal disease. Although this risk is associated with even a single dose, multiple doses increase the danger and therefore should be avoided.

Ketorolac should also be used with caution in patients with asthma. As a subset of asthma patients will experience severe bronchospasm after NSAID administration, clinicians should always determine whether a patient can tolerate NSAIDs.

Renal Toxicity and GI Effects

Concerns over renal toxicity and potential GI distress are the chief disadvantages of NSAID use. While renal toxicity has been reported in patients without pre-existing kidney dysfunction, it is of much greater concern in patients with pre-existing renal disease or decreased glomerular filtration rate. For this reason, care must be exercised when prescribing NSAIDS to elderly patients, patients with diabetes mellitus, or patients with hypertension (or even worse, a combination of these). Prolonged use of NSAIDs can also cause upper GI bleeding. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are contraindicated in pregnant patients.

Opioid analgesics

Morphine

Morphine is the prototypical compound in the opioid class, and has been utilized for more than two centuries since its isolation in 1804.19 Other opioid compounds include codeine, hydrocodone, oxycodone, morphine, and hydromorphone, which represent different functional groups substituted onto the base morphine molecule. All share similar pharmacology, differing primarily only in potency. The onset of action for codeine, hydrocodone, and oxycodone is 30 to 60 minutes when taken orally, with a peak time of 60 to 90 minutes. Codeine and hydrocodone are at the weak-end of the spectrum (Step 2 medications), while morphine and hydromorphone are more potent (Step 3 medications). The majority of opioids and their metabolites are primarily excreted renally (90%-95%).20 Therefore, care must be exercised regarding dosing and frequency when used in patients with renal insufficiency or disease.

Morphine has several features that make it an attractive analgesic for use in the ED. The ability to administer morphine via IV, IM, subcutaneous, or oral route; its quick onset of action; and safety profile are all advantageous. The onset of action is 5 to 10 minutes when given IV. For oral administration, it is 30 to 60 minutes (similar to the other opioids discussed) and can be given as a tablet or syrup.

Morphine decreases the severity of pain, with an apparent increase in tolerance for any remaining discomfort. The potency and central action of morphine make it ideal for managing moderate and severe pain.

As with other analgesics, morphine and its related compounds have associated drawbacks, of which respiratory depression is the most feared, though this is uncommon at therapeutic doses. The respiratory depressant effect is more pronounced in patients with underlying lung disease, depressed mental status, or concurrent use of sedating medication (eg, benzodiazepines).

Another disadvantage to morphine is that it can cause hypotension, limiting its use in certain clinical situations. Repeated or prolonged use may cause slowing or complete arrest of peristaltic waves in the GI tract, which can lead to significant constipation. Pruritus and nausea are two other frequently reported side effects and may necessitate, respectively, coadministration of diphenhydramine (eg, Benadryl) or an antiemetic (eg, Phenergan or Zofran). As an opioid, morphine is potentially addictive, though it is generally thought to require significant intake over several weeks before such problems arise.

The sedation caused by morphine is also of concern, as patients who are under its influence immediately following discharge cannot safely drive, and may actually not be safe to walk or even utilize public transportation. This concern can be lessened by verifying the patient’s mode of transport prior to administration of the medication, ensuring that patients are not overly sedated at the time of discharge and, as much as possible, accompanied home by an adult relative or friend. In comparison to other frequently used opioids, several features can be considered. The duration of action for codeine, hydromorphone, and morphine is similar at 3 to 5 hours.

Hydromorphone

Hydromorphone (Dilaudid) is approximately seven times more potent than morphine, but otherwise very similar. It is frequently the IV opioid of choice for severe pain and also appears to cause pruritus less frequently than morphine. Hydromorphone has a rapid onset of action (1-5 minutes IV; 15-30 minutes orally) and can be titrated to effect when given via the IV route, making it an ideal agent for the pain associated with long bone or pelvic fractures, vasoocclusive crises in patients with sickle cell disease, and renal colic. The oral formulation of hydromorphone can be utilized for severe pain in the appropriate patient population, usually at a dose of 2 to 4 mg every 4 hours.

Codeine

Codeine is frequently prescribed in combination with acetaminophen in a product marketed as Tylenol #3 for mild-to-moderate pain. Because codeine is metabolized in the liver to morphine, it is contraindicated in patients with morphine allergy. Also, the clinician must be aware that codeine is ineffective in 7% to 10% of the population due to an enzyme deficiency.

Hydrocodone and oxycodone, which are often combined with acetaminophen and marketed respectively as Vicodin and Percocet, are two additional commonly used compounds in the oral treatment of moderate-to-severe pain. There are numerous preparations containing various strengths of both the opioid and acetaminophen components. Utilizing these medications as initial pain control in the ED can be beneficial, as therapy can be continued as an outpatient. Table 2 provides dosing and frequency information, but the clinician must also be aware of the total amount of acetaminophen administered, especially when being used in conjunction with other medications containing acetaminophen.

Tramadol

Tramadol (Ultram), another oral analgesic with opioid properties, affects several neurotransmitters and is less reliant on the opioid receptors compared to the opioid compounds described above. It is used to treat moderate-to-severe pain and can be considered another option along with codeine, hydrocodone, and oxycodone for oral pain control. Although the complete mechanism of action for tramadol is poorly understood, it appears to be effective in patients who do not respond well to pure opioids, and in patients with neuropathic pain or persistent pain of unclear etiology (eg, fibromyalgia).19 Because of its limited interaction with opioid receptors, tramadol has less potential for abuse and addiction than the opioids. It is also available in several combinations with acetaminophen or ibuprofen.

Conclusion

The ideal medication for treating pain in the ED is one that is effective, easy to administer, and has minimal adverse or residual effects. Generally, the least potent medication that will control pain should be chosen initially. When treating minor traumatic or musculoskeletal pain, initiating pain control with oral medication in the ED may provide patients with relief during imaging or splinting, and help control pain until they can fill outpatient prescriptions. All of the medications discussed in this article can be given in the oral form. However, IV usage may be appropriate when there is need for rapid onset of action, to titrate the medication, or for ease of administration in patients who are vomiting or unable to take anything orally.

When prescribing analgesics for pain control after discharge, the clinician must consider potential relative and absolute contraindications. For acetaminophen, liver toxicity is the major concern, and care must be taken not to exceed recommended daily dosing limits with the multitude of available products containing acetaminophen. Physicians should avoid recommending or prescribing acetaminophen to patients with liver disease (ie, cirrhosis) or habitual alcohol abuse.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen and naproxen carry the risk of renal damage, as well as concerns about antiplatelet activity. Because of the tendency for renal function to decline with age, caution must be exercised in using these compounds in older patients and those with preexisting renal dysfunction.

Opioid-containing medications are known for their potency in pain control, but also for their side effects. The most common side effect involves the GI tract, with nausea, vomiting, and constipation. The most dangerous side effect of opioids is respiratory depression; fortunately, this is rarely seen with therapeutic doses. However, somnolence and decreased coordination are significant concerns when prescribing opioids to elderly patients or those already at risk for falls.

There is no ideal single medication to treat all types of pain or situations. However, the choice of medication begins with a decision by the EP to treat pain. Utilizing a stepwise approach, oral medication will usually be effective for mild pain, but IV narcotics will probably be required for severe pain. Frequent reassessment of the patient is critically important for successful pain management in the ED.

Dr Byers is an emergency physician at the Presbyterian Medical Group, department of emergency medicine, Presbyterian Healthcare Services, Albuquerque, New Mexico. Dr Counselman is a distinguished professor of emergency medicine and chairman, department of emergency medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School and Emergency Physicians of Tidewater, Norfolk, Virginia. He is also associate editor-in-chief of the Emergency Medicine editorial board.

Pain, one of the most common reasons patients present to the ED, may be a primary complaint or a warning sign encouraging further evaluation. The decision to treat pain is one of the most frequent therapeutic decisions made by emergency physicians (EPs) and involves a variety of options and considerations. Moreover, the decision of how to treat pain similarly encompasses a wide selection of variables, including etiology and severity of the pain; intravenous (IV) access; medication allergies; renal function; alcohol use; rapidity of onset; patients’ vital signs; patient preference; and mode of transport upon discharge. Given all of these considerations, there is no perfect analgesic to suit every circumstance. Rather, EPs must tailor their analgesic selection to the individual clinical situation and patient.

The literature over the past 20 years is replete with studies demonstrating the undertreatment or inadequate treatment of pain in the ED.1-5 Often referred to as oligoanalgesia,6 contributing factors include physician concerns regarding adverse side effects, secondary gain, and drug addiction. In addition, the increasing pressure placed on EPs to diagnose and dispose patients quickly likely relegates pain control to a secondary concern.

Further complicating the issue, physicians’ own prejudices and perceptions appear to influence their analgesic prescription practice. For example, several studies have demonstrated that black patients do not receive prescriptions for analgesics similar to those written for white patients in general, and particularly not for opioid analgesics. In a meta-analysis of pain treatment disparity studies, blacks were 22% less likely than whites to receive any analgesics, and 29% less likely than whites to receive opioid treatment for the same type of painful conditions.7 Likewise, Hispanic/Latino patients were also 22% less likely than their white counterparts to receive opioid treatment for similar pain.7 Physicians must keep these common biases in mind when treating patients for pain.

The administration of analgesics and the prescription habits of physicians has never been under greater scrutiny. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has benchmarked “median time to pain management for long bone fractures” as a core measure, possibly affecting hospital reimbursement rates. Similarly, every patient satisfaction survey specifically inquires about the timeliness and adequacy of pain control. At the same time, though, the increasing problem of prescription opioid abuse has become the nation’s fastest growing drug problem. In 2013, prescription drug abuse was second only to marijuana as the most abused drug category.8 Contributing to this problem are the frequency and ease with which many physicians prescribe opioids. From 1997 to 2007, the milligram-per-person use of prescription opioids in the United States increased from 74 mg per year to 369 mg per year—an increase of 402%.9 As a result, some legislators are now calling for mandatory educational sessions for any physician prescribing medications containing opioids.

Though there are many classes of medications used to treat pain, and numerous individual drugs within each class, this article focuses on several of the more commonly prescribed medications in the ED, including their mechanisms of action, advantages, and disadvantages. The management of pediatric pain and procedural sedation and analgesia are not discussed in this review, as each of these topics deserves a separate detailed discussion.

Recognizing and Quantifying Pain

The first step in treating pain appropriately is recognition. Physicians must specifically inquire about pain and not rely solely on a patient’s unprompted complaint. Several pain scales exist, including the Faces Pain Scale (ie, pictorial representation of a smiling face on one end indicating “no pain” to a frowning face on the opposite end); the verbal quantitative scale or numerical rating scale (ie, “how would you rate your pain on a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 the worst pain ever?”); and the visual analog scale (ie, a 10-cm linear scale marked at one end with “no pain” and “worst pain imaginable” at the opposite end).10,11 Probably the most commonly used scale in the ED is some variation of the numerical rating scale (NRS).1

Each of these scales has its own advantages and disadvantages, but the important point is that patients are given the opportunity to express the type and degree of pain to the healthcare provider. In addition, a pain scale provides a starting point against which the practitioner (or later practitioners) can determine the success (or failure) of a pain treatment strategy.

Three-Step Ladder

In 1996, the World Health Organization developed a three-step analgesic ladder to guide the management of cancer pain.12 Its use has been expanded over time to include treating pain of noncancer etiology. Mild pain (NRS of 1 to 3) is considered Step 1; moderate pain (NRS 4 to 6) is considered Step 2; and severe pain (NRS 7 to 10) is Step 3. For Step 1 (mild pain), acetaminophen or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) is recommended. For Step 2 (moderate pain), a weak opioid (ie, codeine or hydrocodone) with or without acetaminophen or an NSAID is recommended. Finally, for Step 3 (severe pain), a strong opioid such as morphine or hydromorphone is recommended.

Again, the purpose of the ladder is not to provide a strict protocol for adherence, but rather to provide a reasonable starting point as a guide to the clinician. The key to its successful use is reassessment of the patient to determine if adequate pain relief is achieved.

Routes of Administration

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen, the active ingredient in Tylenol, was first marketed in the United States in 1955 as an antipyretic and pain reliever.13 It is a synthetic centrally acting analgesic that is metabolized in the liver. Acetaminophen has been used alone or in combination in hundreds of formulations to treat a wide variety of pain and fever-related conditions. In the ED setting, acetaminophen is frequently used as an antipyretic and—either alone or in combination with opioids—for oral pain control.

Acetaminophen is very well tolerated by most patients, with minimal gastrointestinal (GI) distress. It is inexpensive, and the wide variety of formulations (eg, liquid, tablet, suppository) make it useful in a number of clinical scenarios. Acetaminophen is generally considered to be the only nonopioid analgesic that is safe in pregnancy,14 and it has no sedative or addictive effects.

There are, however, some disadvantages to using acetaminophen. Concerns about its safety and accidental overdose have recently led to the introduction of a 4,000-mg maximum daily dose recommendation15 and heightened concern over using multiple medications containing acetaminophen. In January 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration recommended that no combination medication contain more than 325 mg of acetaminophen because of the risk of toxicity when multiple drugs containing acetaminophen are consumed.

In addition to concerns of inadvertent overdose, another disadvantage of acetaminophen is that while it may be an effective antipyretic and analgesic, it has little or no anti-inflammatory properties. Therefore, in cases requiring an anti-inflammatory agent, an NSAID, when appropriate, would be the more effective option.

NSAIDs

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs function by inhibiting prostaglandin production in the cyclooxygenase 1 and 2 (COX-1 and COX-2) pathways. Ibuprofen, indomethacin, ketorolac, naproxen, and other NSAIDs are chiefly utilized to control pain, inflammation, and fever via the oral route. As production of various prostaglandins via the COX-2 pathway is thought to contribute to fever, inflammation, and pain, inhibition of this pathway by NSAIDs can help alleviate these symptoms. The COX-1 pathway contributes many factors important to the protection and health of the GI tract, and inhibition of this pathway can lead to GI distress and damage. Unfortunately, the most commonly used and available NSAIDs inhibit both COX pathways simultaneously, and in doing so, prompt the GI symptoms which are the most common adverse side effects of therapy. In addition to GI effects of the COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitors, there are also concerns over the associated antiplatelet effects in patients undergoing surgery or potentially suffering from occult or intracranial bleeding.13

Ibuprofen

This is the most commonly used NSAID in the United States and is available without a prescription. Ibuprofen is typically used to treat mild-to-moderate pain from a musculoskeletal or inflammatory source. As an oral nonprescription medication, it can be used advantageously to treat acute pain in the ED and continued in the outpatient setting. Ibuprofen is neither sedating nor addicting, with a rapid onset of action and a plasma half-life of approximately 2 hours.13 However, there is a dose-dependent feature which allows large doses (eg, 800 mg) to be spaced-out every 8 hours while maintaining effective analgesia. Typical doses range from 200 mg to 800 mg orally every 6 to 8 hours, with a maximum dose of 3.2 g/d. Patients should be instructed to take each dose with a meal or snack to help alleviate GI side effects.

The greatest advantage of ibuprofen and other NSAIDs is their effect on inflammation and the ability to treat the inflammatory cause of pain—not just the symptom. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are well tolerated by most patients and can be obtained without prescription at low cost. Additionally, doses of ibuprofen and acetaminophen can be alternated.

Ketorolac

Often marketed as Toradol, ketorolac is a powerful NSAID available in IV, IM, and oral formulations. Typical doses are 30 mg IV, 60 mg IM, or 10 mg orally every 4 to 6 hours (maximum of 40 mg/d). The basic pharmacology and mechanism of action of ketorolac are similar to ibuprofen. Though ketorolac is useful to treat more severe pain, it should only be used for short-term management of pain (ie, 5 days or less). Ketorolac is often used for postoperative pain, but also is helpful for pain control in patients using opioids. It has been shown to be effective for acute renal colic and can also provide relief for migraine headaches.16,17 In a direct comparison between ketorolac and meperidine (Demerol) for patients suffering from renal stones, ketorolac was found to be more effective and provide longer lasting pain relief.18

The major concern regarding ketorolac relates to potential renal toxicity, and thus caution should be undertaken in prescribing it to patients with known or suspected renal disease. Although this risk is associated with even a single dose, multiple doses increase the danger and therefore should be avoided.

Ketorolac should also be used with caution in patients with asthma. As a subset of asthma patients will experience severe bronchospasm after NSAID administration, clinicians should always determine whether a patient can tolerate NSAIDs.

Renal Toxicity and GI Effects

Concerns over renal toxicity and potential GI distress are the chief disadvantages of NSAID use. While renal toxicity has been reported in patients without pre-existing kidney dysfunction, it is of much greater concern in patients with pre-existing renal disease or decreased glomerular filtration rate. For this reason, care must be exercised when prescribing NSAIDS to elderly patients, patients with diabetes mellitus, or patients with hypertension (or even worse, a combination of these). Prolonged use of NSAIDs can also cause upper GI bleeding. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are contraindicated in pregnant patients.

Opioid analgesics

Morphine

Morphine is the prototypical compound in the opioid class, and has been utilized for more than two centuries since its isolation in 1804.19 Other opioid compounds include codeine, hydrocodone, oxycodone, morphine, and hydromorphone, which represent different functional groups substituted onto the base morphine molecule. All share similar pharmacology, differing primarily only in potency. The onset of action for codeine, hydrocodone, and oxycodone is 30 to 60 minutes when taken orally, with a peak time of 60 to 90 minutes. Codeine and hydrocodone are at the weak-end of the spectrum (Step 2 medications), while morphine and hydromorphone are more potent (Step 3 medications). The majority of opioids and their metabolites are primarily excreted renally (90%-95%).20 Therefore, care must be exercised regarding dosing and frequency when used in patients with renal insufficiency or disease.

Morphine has several features that make it an attractive analgesic for use in the ED. The ability to administer morphine via IV, IM, subcutaneous, or oral route; its quick onset of action; and safety profile are all advantageous. The onset of action is 5 to 10 minutes when given IV. For oral administration, it is 30 to 60 minutes (similar to the other opioids discussed) and can be given as a tablet or syrup.

Morphine decreases the severity of pain, with an apparent increase in tolerance for any remaining discomfort. The potency and central action of morphine make it ideal for managing moderate and severe pain.

As with other analgesics, morphine and its related compounds have associated drawbacks, of which respiratory depression is the most feared, though this is uncommon at therapeutic doses. The respiratory depressant effect is more pronounced in patients with underlying lung disease, depressed mental status, or concurrent use of sedating medication (eg, benzodiazepines).

Another disadvantage to morphine is that it can cause hypotension, limiting its use in certain clinical situations. Repeated or prolonged use may cause slowing or complete arrest of peristaltic waves in the GI tract, which can lead to significant constipation. Pruritus and nausea are two other frequently reported side effects and may necessitate, respectively, coadministration of diphenhydramine (eg, Benadryl) or an antiemetic (eg, Phenergan or Zofran). As an opioid, morphine is potentially addictive, though it is generally thought to require significant intake over several weeks before such problems arise.

The sedation caused by morphine is also of concern, as patients who are under its influence immediately following discharge cannot safely drive, and may actually not be safe to walk or even utilize public transportation. This concern can be lessened by verifying the patient’s mode of transport prior to administration of the medication, ensuring that patients are not overly sedated at the time of discharge and, as much as possible, accompanied home by an adult relative or friend. In comparison to other frequently used opioids, several features can be considered. The duration of action for codeine, hydromorphone, and morphine is similar at 3 to 5 hours.

Hydromorphone

Hydromorphone (Dilaudid) is approximately seven times more potent than morphine, but otherwise very similar. It is frequently the IV opioid of choice for severe pain and also appears to cause pruritus less frequently than morphine. Hydromorphone has a rapid onset of action (1-5 minutes IV; 15-30 minutes orally) and can be titrated to effect when given via the IV route, making it an ideal agent for the pain associated with long bone or pelvic fractures, vasoocclusive crises in patients with sickle cell disease, and renal colic. The oral formulation of hydromorphone can be utilized for severe pain in the appropriate patient population, usually at a dose of 2 to 4 mg every 4 hours.

Codeine

Codeine is frequently prescribed in combination with acetaminophen in a product marketed as Tylenol #3 for mild-to-moderate pain. Because codeine is metabolized in the liver to morphine, it is contraindicated in patients with morphine allergy. Also, the clinician must be aware that codeine is ineffective in 7% to 10% of the population due to an enzyme deficiency.

Hydrocodone and oxycodone, which are often combined with acetaminophen and marketed respectively as Vicodin and Percocet, are two additional commonly used compounds in the oral treatment of moderate-to-severe pain. There are numerous preparations containing various strengths of both the opioid and acetaminophen components. Utilizing these medications as initial pain control in the ED can be beneficial, as therapy can be continued as an outpatient. Table 2 provides dosing and frequency information, but the clinician must also be aware of the total amount of acetaminophen administered, especially when being used in conjunction with other medications containing acetaminophen.

Tramadol

Tramadol (Ultram), another oral analgesic with opioid properties, affects several neurotransmitters and is less reliant on the opioid receptors compared to the opioid compounds described above. It is used to treat moderate-to-severe pain and can be considered another option along with codeine, hydrocodone, and oxycodone for oral pain control. Although the complete mechanism of action for tramadol is poorly understood, it appears to be effective in patients who do not respond well to pure opioids, and in patients with neuropathic pain or persistent pain of unclear etiology (eg, fibromyalgia).19 Because of its limited interaction with opioid receptors, tramadol has less potential for abuse and addiction than the opioids. It is also available in several combinations with acetaminophen or ibuprofen.

Conclusion

The ideal medication for treating pain in the ED is one that is effective, easy to administer, and has minimal adverse or residual effects. Generally, the least potent medication that will control pain should be chosen initially. When treating minor traumatic or musculoskeletal pain, initiating pain control with oral medication in the ED may provide patients with relief during imaging or splinting, and help control pain until they can fill outpatient prescriptions. All of the medications discussed in this article can be given in the oral form. However, IV usage may be appropriate when there is need for rapid onset of action, to titrate the medication, or for ease of administration in patients who are vomiting or unable to take anything orally.

When prescribing analgesics for pain control after discharge, the clinician must consider potential relative and absolute contraindications. For acetaminophen, liver toxicity is the major concern, and care must be taken not to exceed recommended daily dosing limits with the multitude of available products containing acetaminophen. Physicians should avoid recommending or prescribing acetaminophen to patients with liver disease (ie, cirrhosis) or habitual alcohol abuse.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ibuprofen and naproxen carry the risk of renal damage, as well as concerns about antiplatelet activity. Because of the tendency for renal function to decline with age, caution must be exercised in using these compounds in older patients and those with preexisting renal dysfunction.

Opioid-containing medications are known for their potency in pain control, but also for their side effects. The most common side effect involves the GI tract, with nausea, vomiting, and constipation. The most dangerous side effect of opioids is respiratory depression; fortunately, this is rarely seen with therapeutic doses. However, somnolence and decreased coordination are significant concerns when prescribing opioids to elderly patients or those already at risk for falls.

There is no ideal single medication to treat all types of pain or situations. However, the choice of medication begins with a decision by the EP to treat pain. Utilizing a stepwise approach, oral medication will usually be effective for mild pain, but IV narcotics will probably be required for severe pain. Frequent reassessment of the patient is critically important for successful pain management in the ED.

Dr Byers is an emergency physician at the Presbyterian Medical Group, department of emergency medicine, Presbyterian Healthcare Services, Albuquerque, New Mexico. Dr Counselman is a distinguished professor of emergency medicine and chairman, department of emergency medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School and Emergency Physicians of Tidewater, Norfolk, Virginia. He is also associate editor-in-chief of the Emergency Medicine editorial board.

- Todd KH. Pain assessment instruments for use in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23(2):285-295.

- Cordell WH, Keene KK, Giles BK, Jones JB, Jones JH, Brizendine EJ. The high prevalence of pain in emergency medical care. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20(3):165-169.

- Tcherny-Lessenot S, Karwowski-Soulié F, Lamarche-Vadel A, Ginsburg C, Brunet F, Vidal-Trecan G. Management and relief of pain in an emergency department from the adult patients’ perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25(6):539-546.

- Karwowski-Soulié F, Lessenot-Tcherny S, Lamarche-Vadel A, et al. Pain in an emergency department: an audit. Eur J Emerg Med. 2006;13(4):218-224.

- Fosnocht DE, Swanson ER, Barton ED. Changing attitudes about pain and pain control in emergency medicine. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23(2):297-306.

- Wilson JE, Pendelton JM. Oligoanalgesia in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 1989;7(6):620-623.

- Meghani SH, Byun E, Gallagher RM. Time to take stock: a meta-analysis and systemic review of analgesic treatment disparities for pain in the United States. Pain Med. 2012;13(2):150-174.

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schutenberg JE; The University of Michigan Institute for Social Research. Monitoring the future: 2013 overview key findings of on adolescent drug use. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2013.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2014.

- Manchikanti L, Fellow B, Ailinani H, Pampati V. Therapeutic use, abuse, and nonmedical use of opioids: a ten year perspective. Pain Physician. 2010;13(5):401-435.

- Silka PA, Roth MM, Moreno G, Merrill L, Geiderman JM. Pain scores improve analgesic administration patterns for trauma patients in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(3):264-270.

- Nelson BP, Cohen D, Lander O, Crawford N, Viccellio AW, Singer AJ. Mandated pain scales improve frequency of ED analgesic administration. Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22(7):582-585.

- World Health Organization. Cancer pain relief with a guide to opioid availability 2nd ed. 1996. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/9241544821.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2014.

- Grosser T, Smyth EM, FitzGerald GA. Anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, and analgesic agents: pharmacotherapy of gout. In: Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollman BC, eds. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12th ed. China: The McGraw Hill Companies; 2011:959-1004.

- Scialli AR, Ang R, Breitmeyer J, Royal MA. A review of the literature on the effects of acetaminophen on pregnancy outcome. Reprod Toxicol. 2010;30(4):495-507.

- Schilling A, Corey R, Leonard M, Eghtesad B. Acetaminophen: old drug, new warnings. Cleveland Clin J Med. 2010;77(1):19-27.

- Shrestha M, Singh R, Moreden J, Hayes JE. Ketorolac vs chlorpromazine in the treatment of acute migraine without aura. A prospective, randomized, double-blind trial. Arch Intern Med.1996;156(15):1725-1728.

- Turkewitz LJ, Casaly JS, Dawson GA, Wirth O, Hurst RJ, Gillette PL. Self-administration of parenteral ketorolac tromethamine for head pain. Headache. 1992;32(9):452-454.

- Larkin GL, Peacock WF 4th, Pearl SM, Blair GA, D’Amico F. Efficacy of ketorolac tromethamine versus meperidine in the ED treatment of acute renal colic. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17(1):6-10.

- Yaksh TL, Wallace MS. Opiods, analgesia and pain management. In: Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollman BC, eds. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12th ed. China: The McGraw Hill Companies; 2011:481-526.

- DeSandre PL, Quest TE. Management of cancer-related pain. Hematol Oncol Clin N Am. 2010;24(3):643-658.

- Todd KH. Pain assessment instruments for use in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23(2):285-295.

- Cordell WH, Keene KK, Giles BK, Jones JB, Jones JH, Brizendine EJ. The high prevalence of pain in emergency medical care. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20(3):165-169.

- Tcherny-Lessenot S, Karwowski-Soulié F, Lamarche-Vadel A, Ginsburg C, Brunet F, Vidal-Trecan G. Management and relief of pain in an emergency department from the adult patients’ perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25(6):539-546.

- Karwowski-Soulié F, Lessenot-Tcherny S, Lamarche-Vadel A, et al. Pain in an emergency department: an audit. Eur J Emerg Med. 2006;13(4):218-224.

- Fosnocht DE, Swanson ER, Barton ED. Changing attitudes about pain and pain control in emergency medicine. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23(2):297-306.

- Wilson JE, Pendelton JM. Oligoanalgesia in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 1989;7(6):620-623.

- Meghani SH, Byun E, Gallagher RM. Time to take stock: a meta-analysis and systemic review of analgesic treatment disparities for pain in the United States. Pain Med. 2012;13(2):150-174.

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schutenberg JE; The University of Michigan Institute for Social Research. Monitoring the future: 2013 overview key findings of on adolescent drug use. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2013.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2014.

- Manchikanti L, Fellow B, Ailinani H, Pampati V. Therapeutic use, abuse, and nonmedical use of opioids: a ten year perspective. Pain Physician. 2010;13(5):401-435.

- Silka PA, Roth MM, Moreno G, Merrill L, Geiderman JM. Pain scores improve analgesic administration patterns for trauma patients in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(3):264-270.

- Nelson BP, Cohen D, Lander O, Crawford N, Viccellio AW, Singer AJ. Mandated pain scales improve frequency of ED analgesic administration. Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22(7):582-585.

- World Health Organization. Cancer pain relief with a guide to opioid availability 2nd ed. 1996. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/9241544821.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2014.

- Grosser T, Smyth EM, FitzGerald GA. Anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, and analgesic agents: pharmacotherapy of gout. In: Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollman BC, eds. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12th ed. China: The McGraw Hill Companies; 2011:959-1004.

- Scialli AR, Ang R, Breitmeyer J, Royal MA. A review of the literature on the effects of acetaminophen on pregnancy outcome. Reprod Toxicol. 2010;30(4):495-507.

- Schilling A, Corey R, Leonard M, Eghtesad B. Acetaminophen: old drug, new warnings. Cleveland Clin J Med. 2010;77(1):19-27.

- Shrestha M, Singh R, Moreden J, Hayes JE. Ketorolac vs chlorpromazine in the treatment of acute migraine without aura. A prospective, randomized, double-blind trial. Arch Intern Med.1996;156(15):1725-1728.

- Turkewitz LJ, Casaly JS, Dawson GA, Wirth O, Hurst RJ, Gillette PL. Self-administration of parenteral ketorolac tromethamine for head pain. Headache. 1992;32(9):452-454.

- Larkin GL, Peacock WF 4th, Pearl SM, Blair GA, D’Amico F. Efficacy of ketorolac tromethamine versus meperidine in the ED treatment of acute renal colic. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17(1):6-10.

- Yaksh TL, Wallace MS. Opiods, analgesia and pain management. In: Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollman BC, eds. Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12th ed. China: The McGraw Hill Companies; 2011:481-526.

- DeSandre PL, Quest TE. Management of cancer-related pain. Hematol Oncol Clin N Am. 2010;24(3):643-658.