User login

Agitated and hallucinating, with a throbbing headache

CASE Psychotic, and nonadherent

Mr. K, a 42-year-old Fijian man, is brought to the emergency department by his older brother for evaluation of behavioral agitation. Mr. K is belligerent and threatens to kill his family members. Three years earlier, he was given a diagnosis of schizophrenia and treated at an inpatient psychiatric unit.

At that time, Mr. K was stabilized on risperidone, 4 mg/d. However, he did not follow-up with treatment after discharge and has not taken any psychotropic medications since that time.

His brother reports that Mr. K has been slowly deteriorating, talking to himself, staying up at night, and getting into arguments with his family over his delusional beliefs. Although Mr. K once worked as a security guard, he has not worked in 8 years. He has been living with his family, who are no longer willing to accept him into their home because they fear he might harm them.

In the emergency department, Mr. K reports that he has a throbbing headache. Blood pressure is 177/101 mm Hg; heart rate is 103 beats per minute; respiratory rate is 18 breaths per minute; weight is 185 lb; and body mass index (BMI) is 31.8. Physical examination is unremarkable.

Laboratory values show that sodium is 131 mEq/L; potassium, 3.7 mEq/L; bicarbonate, 26 mEq/L; glucose, 420 mg/dL; hemoglobin A1c,12.7; and urine glucose, 3+. Mr. K denies being told he has diabetes.

What are Mr. K’s risk factors for diabetes?

a) schizophrenia

b) physical inactivity

c) obesity

d) Fijian ethnicity

e) all of the above

The authors’ observations

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in persons with schizophrenia or a schizoaffective disorder is twice that of the general population.1-4 Multiple variables contribute to the increased prevalence of diabetes in this population, including genetic predisposition, environmental and cultural factors related to diet and physical activity, a high rate of smoking,5,6 iatrogenic causes (metabolic dysregulation and weight gain from antipsychotic treatment), and socioeconomic factors (poverty, lack of access to health care). In addition, symptoms of psychosis such as thought disorder, delusions, hallucinations, and cognitive decline in persons with chronic schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder can make basic health maintenance difficult.

In Mr. K’s case, premorbid risk of diabetes was elevated because of his Fijian ethnicity.7 With a BMI of 31.8, obesity further increased that risk.5,6,8 In addition, his untreated chronic mental illness, lack of access to health care, low socioeconomic status, long-standing smoking habit, and previous exposure to antipsychotics also increased his risk of T2DM.

The interaction between diabetes and psychosis contributes to a vicious cycle that makes both conditions worse if either, or both, are untreated. In general, medical comorbidities are associated with depression and neurocognitive impairment in persons with schizophrenia.9 Specifically, diabetes is associated with lower global cognitive functioning among persons with schizophrenia.10 Poor cognitive functioning can, in turn, decrease the patient’s ability to manage his medical illness. Also, persons with schizophrenia are less likely to be treated for diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, as in Mr. K’s case.11

How would you treat Mr. K’s newly diagnosed diabetes?

a) refer him to a primary care physician

b) start an oral agent

c) start sliding-scale insulin

d) start long-acting insulin

e) recommend a carbohydrate-controlled diet=

TREATMENT Stabilization

Mr. K is admitted to the medical unit for treatment of hyperglycemia. The team starts him on amlodipine, 5 mg/d, for hypertension; aripiprazole, 10 mg/d, for psychosis; and sliding-scale insulin (lispro) and 20 units of insulin (glargine) nightly for diabetes. Mr. K’s blood glucose level is well regulated on this regimen; after being medically cleared, he is transferred to the inpatient psychiatric unit.

EVALUATION Denies symptoms

Mr. K appears older than his stated age, is poorly groomed, and is dressed in a hospital gown. He is isolated and appears to be internally preoccupied. He repeatedly denies hearing auditory hallucinations, but often is overheard responding to internal stimuli and mumbling indecipherably in a low tone. His speech is decreased and his affect is flat and guarded. He states that he is not “mental” but that he came to the hospital for “tooth pain.” Every day he asks when he can return home and he asks the staff to call his family to take him home. When informed that his family is not able to care for him, Mr. K states that he would live in a house he owns in Fiji, which his family members state is untrue.

How would you treat Mr. K’s psychosis?

a) continue aripiprazole

b) switch to risperidone, an agent to which he previously responded

c) switch to olanzapine because he has not been sleeping well

d) switch to haloperidol because of diabetes

The authors’ observations

Pharmacotherapy for patients with comorbid schizophrenia and diabetes requires consideration of clinical and psychosocial factors unique to this population.

Antipsychotic choice

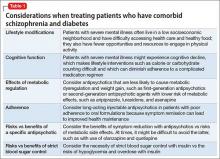

Selection of an antipsychotic agent to address psychosis requires considering its efficacy, side-effect profile, and adherence rates, as well as its potential effects on metabolic regulation and weight (Table 1). Typical antipsychotics are less likely than atypical antipsychotics to cause metabolic dysregulation.12 When treatment with atypical antipsychotics cannot be avoided—such as when side effects or an allergic reaction develop—consider selecting a relatively weight-neutral drug with a lower potential for metabolic dysregulation, such as aripiprazole. However, many times, using an agent with significant effects on metabolic regulation cannot be avoided, making treating and monitoring the resulting metabolic effects even more significant.

Glycemic control

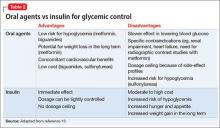

Initiating an agent for glycemic control in persons with newly diagnosed diabetes requires weighing many factors, including mode of delivery (oral or subcutaneous), level of glycemic control required, comorbid medical illness (such as renal impairment and heart failure), cost, and potential long-term side effects of the medication (Table 2).13 Oral agents have a slower effect on lowering the blood glucose level, and each agent carries contraindications, but generally they are more affordable. Many present a low risk of hypoglycemia but sulfonylureas are an exception. In addition, metformin could lead to weight loss over the long term, which further lowers the risk of diabetes.

If, however, tight and immediate glycemic control is needed, subcutaneous insulin injections might be required, although this method is more costly, carries an increased risk of hypoglycemic episodes acutely, and leads to weight gain in the long run because of induced hunger and increased appetite.

Psychosocial factors

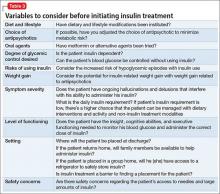

In addition to the clinical variables above, treating diabetes in patients with comorbid schizophrenia requires considering other psychosocial factors that might not be readily apparent (Table 3). For example, patients with schizophrenia might have decreased motivation, self-efficacy, and capacity for self-care when it comes to health maintenance and medication adherence.14 Chronically mentally ill persons might have reduced cognitive functioning that could affect their ability to maintain complicated medication regimens, such as administering insulin and monitoring blood glucose.

In addition, easy access to hypodermic needles and large amounts of insulin could become a safety concern in patients with ongoing hallucinations, delusions, and thought disorder, despite antipsychotic treatment. For example, a patient with schizophrenia and diabetes who has been maintained on insulin might begin hearing voices that tell her to inject her eyeballs with insulin. Similarly, although the risk of hypoglycemic episodes in patients treated with insulin is well known, patients with schizophrenia have a higher risk of acute complications of diabetes than other patients with diabetes.15Psychosocial factors, such as placement, support system, and follow-up care need to be considered. In some instances, the need to administer daily subcutaneous insulin could be a barrier to placement if the facility does not have the staff or expertise to monitor blood glucose and administer insulin.

If the patient is returning home, then the patient or a caretaker will need to be trained to monitor blood glucose and administer insulin. This might be difficult for persons with chronic mental illness who have lost the support and care of their family. Also, consider the issue of storing insulin, which requires refrigeration. Because of the potential complications involved in using insulin in patients with schizophrenia, practitioners should consider managing non-insulin dependent diabetes with an oral hypoglycemic agent, when possible, along with lifestyle modifications.

OUTCOME Weight loss, discharge

Mr. K is transitioned from aripiprazole to higher-potency oral risperidone, titrated to 6 mg/d. At this dosage, he continues to maintain a delusion about owning a house in Fiji, but was seen responding to internal stimuli less often. The treatment team places him on a diabetic and low-sodium diet of 1,800 kcal/d. His fasting blood glucose levels range in the 70s to 110s mg/dL during his first week of hospitalization.

The treatment team starts Mr. K on oral metformin, titrated to 1,000 mg twice daily, while tapering him off insulin lispro and glargine over the course of hospitalization. The transition from insulin to metformin also is considered because Mr. K’s daily insulin requirement is rather low (<0.5 units/kg).

Mr. K’s course is prolonged because his treatment team initiates the process of conservatorship and placement in the community. Approximately 6 months after his admission, Mr. K is discharged to an unlocked facility with support from an intensive outpatient mental health program. At 6 months follow-up with his outpatient provider, Mr. K’s hemoglobin A1c is 7.0 and he weighs 155 lb with a BMI of 26.5.

The authors’ observations

Despite Mr. K’s initial elevated hemoglobin A1c of 12.7 and weight of 185 lb, over approximately 6 months he experiences a 5.7-unit drop in hemoglobin A1c and weight loss of 30 lb with dietary management and metformin—without the need for other agents. Other options for weight-neutral treatment of T2DM include exenatide, which also is available as a once weekly injectable formulation, canagliflozin, and the gliptins (sitagliptin, saxagliptin, and linagliptin) (Table 4).

Mr. K’s improved control of his diabetes occurred despite initiation of an atypical antipsychotic, which would have been expected to cause additional weight gain and make his diabetes worse secondary to metabolic effects.12 Treatment with metformin in particular has been associated with weight loss in patients with16 and without17 comorbid schizophrenia, including those with antipsychotic-induced weight gain.18-20

Bottom Line

Persons with schizophrenia are at higher risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus for many reasons, including metabolic effects of antipsychotics, reduced cognitive functioning, poor self-care, and limited access to health care. Typical antipsychotics are less likely to cause metabolic dysregulation but, if an atypical is needed, one that is relatively weight-neutral should be selected. When choosing an agent for glycemic control, consider a patient’s or a caretaker’s ability to administer medications, monitor blood glucose, and follow dietary recommendations.

Related Resources

• Cohn T. The link between schizophrenia and diabetes. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(10):28-34,46.

• Annamalai A, Tek C. An overview of diabetes management in schizophrenia patients: office based strategies for primary care practitioners and endocrinologists [published online March 23, 2015]. Int J Endocrinol. 2015;2015:969182. doi: 10.1155/2015/969182.

Drug Brand Names

Amlodipine • Norvasc

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Asenapine • Saphris

Canagliflozin • Invokana

Exenatide • Bydureon, Byetta

Glargine • Lantus

Linagliptin • Tradjenta

Lispro • Humalog

Lurasidone • Latuda

Metformin • Glucophage

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Saxagliptin • Onglyza

Sitagliptin • Januvia

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. American Diabetes Association; American Psychiatric Association; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; North American Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):596-601.

2. Heald A. Physical health in schizophrenia: a challenge for antipsychotic therapy. Eur Psychiatry. 2010;25(suppl 2):S6-S11.

3. El-Mallakh P. Doing my best: poverty and self-care among individuals with schizophrenia and diabetes mellitus. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2007;21(1):49-60; discussion 61-63.

4. Rouillon F, Sorbara F. Schizophrenia and diabetes: epidemiological data. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20(suppl 4):S345-S348.

5. Willi C, Bodenmann P, Ghali WA, et al. Active smoking and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2007;298(22):2654-2664.

6. Dome P, Lazary J, Kalapos MP, et al. Smoking, nicotine and neuropsychiatric disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;34(3):295-342.

7. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. For people of African, Mediterranean, or Southeast Asian heritage: important information about diabetes blood tests. http://www.diabetes.niddk.nih.gov/dm/ pubs/asianamerican/index.htm. Published October 2011. Accessed November 18, 2015.

8. Shaten BJ, Smith GD, Kuller LH, et al. Risk factors for the development of type 2 diabetes among men enrolled in the usual care group of the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Diabetes Care. 1993;16(10):1331-1339.

9. Chwastiak LA, Rosenheck RA, McEvoy JP, et al. Interrelationships of psychiatric symptom severity, medical comorbidity, and functioning in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(8):1102-1109.

10. Takayanagi Y, Cascella NG, Sawa A, et al. Diabetes is associated with lower global cognitive function in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;142(1-3):183-187.

11. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

12. Meyer JM, Davis VG, Goff DC, et al. Change in metabolic syndrome parameters with antipsychotic treatment in the CATIE Schizophrenia Trial: prospective data from phase 1. Schizophr Res. 2008;101(1-3):273-286.

13. Inzucchi SE. Clinical practice. Management of hyperglycemia in the hospital setting. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355(18):1903-1911.

14. Chen SR, Chien YP, Kang CM, et al. Comparing self-efficacy and self-care behaviours between outpatients with comorbid schizophrenia and type 2 diabetes and outpatients with only type 2 diabetes. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2014;21(5):414-422.

15. Becker T, Hux J. Risk of acute complications of diabetes among people with schizophrenia in Ontario, Canada. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(2):398-402.

16. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Long-term safety, tolerability, and weight loss associated with metformin in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(4):731-737.

17. Jarskog LF, Hamer RM, Catellier DJ, et al; METS Investigators. Metformin for weight loss and metabolic control in overweight outpatients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1032-1040.

18. Chen CH, Huang MC, Kao CF, et al. Effects of adjunctive metformin on metabolic traits in nondiabetic clozapine-treated patients with schizophrenia and the effect of metformin discontinuation on body weight: a 24-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(5):e424-430. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08186.

19. Wang M, Tong JH, Zhu G, et al. Metformin for treatment of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2012;138(1):54-57.

20. Mizuno Y, Suzuki T, Nakagawa A, et al. Pharmacological strategies to counteract antipsychotic-induced weight gain and metabolic adverse effects in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(6): 1385-1403.

CASE Psychotic, and nonadherent

Mr. K, a 42-year-old Fijian man, is brought to the emergency department by his older brother for evaluation of behavioral agitation. Mr. K is belligerent and threatens to kill his family members. Three years earlier, he was given a diagnosis of schizophrenia and treated at an inpatient psychiatric unit.

At that time, Mr. K was stabilized on risperidone, 4 mg/d. However, he did not follow-up with treatment after discharge and has not taken any psychotropic medications since that time.

His brother reports that Mr. K has been slowly deteriorating, talking to himself, staying up at night, and getting into arguments with his family over his delusional beliefs. Although Mr. K once worked as a security guard, he has not worked in 8 years. He has been living with his family, who are no longer willing to accept him into their home because they fear he might harm them.

In the emergency department, Mr. K reports that he has a throbbing headache. Blood pressure is 177/101 mm Hg; heart rate is 103 beats per minute; respiratory rate is 18 breaths per minute; weight is 185 lb; and body mass index (BMI) is 31.8. Physical examination is unremarkable.

Laboratory values show that sodium is 131 mEq/L; potassium, 3.7 mEq/L; bicarbonate, 26 mEq/L; glucose, 420 mg/dL; hemoglobin A1c,12.7; and urine glucose, 3+. Mr. K denies being told he has diabetes.

What are Mr. K’s risk factors for diabetes?

a) schizophrenia

b) physical inactivity

c) obesity

d) Fijian ethnicity

e) all of the above

The authors’ observations

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in persons with schizophrenia or a schizoaffective disorder is twice that of the general population.1-4 Multiple variables contribute to the increased prevalence of diabetes in this population, including genetic predisposition, environmental and cultural factors related to diet and physical activity, a high rate of smoking,5,6 iatrogenic causes (metabolic dysregulation and weight gain from antipsychotic treatment), and socioeconomic factors (poverty, lack of access to health care). In addition, symptoms of psychosis such as thought disorder, delusions, hallucinations, and cognitive decline in persons with chronic schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder can make basic health maintenance difficult.

In Mr. K’s case, premorbid risk of diabetes was elevated because of his Fijian ethnicity.7 With a BMI of 31.8, obesity further increased that risk.5,6,8 In addition, his untreated chronic mental illness, lack of access to health care, low socioeconomic status, long-standing smoking habit, and previous exposure to antipsychotics also increased his risk of T2DM.

The interaction between diabetes and psychosis contributes to a vicious cycle that makes both conditions worse if either, or both, are untreated. In general, medical comorbidities are associated with depression and neurocognitive impairment in persons with schizophrenia.9 Specifically, diabetes is associated with lower global cognitive functioning among persons with schizophrenia.10 Poor cognitive functioning can, in turn, decrease the patient’s ability to manage his medical illness. Also, persons with schizophrenia are less likely to be treated for diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, as in Mr. K’s case.11

How would you treat Mr. K’s newly diagnosed diabetes?

a) refer him to a primary care physician

b) start an oral agent

c) start sliding-scale insulin

d) start long-acting insulin

e) recommend a carbohydrate-controlled diet=

TREATMENT Stabilization

Mr. K is admitted to the medical unit for treatment of hyperglycemia. The team starts him on amlodipine, 5 mg/d, for hypertension; aripiprazole, 10 mg/d, for psychosis; and sliding-scale insulin (lispro) and 20 units of insulin (glargine) nightly for diabetes. Mr. K’s blood glucose level is well regulated on this regimen; after being medically cleared, he is transferred to the inpatient psychiatric unit.

EVALUATION Denies symptoms

Mr. K appears older than his stated age, is poorly groomed, and is dressed in a hospital gown. He is isolated and appears to be internally preoccupied. He repeatedly denies hearing auditory hallucinations, but often is overheard responding to internal stimuli and mumbling indecipherably in a low tone. His speech is decreased and his affect is flat and guarded. He states that he is not “mental” but that he came to the hospital for “tooth pain.” Every day he asks when he can return home and he asks the staff to call his family to take him home. When informed that his family is not able to care for him, Mr. K states that he would live in a house he owns in Fiji, which his family members state is untrue.

How would you treat Mr. K’s psychosis?

a) continue aripiprazole

b) switch to risperidone, an agent to which he previously responded

c) switch to olanzapine because he has not been sleeping well

d) switch to haloperidol because of diabetes

The authors’ observations

Pharmacotherapy for patients with comorbid schizophrenia and diabetes requires consideration of clinical and psychosocial factors unique to this population.

Antipsychotic choice

Selection of an antipsychotic agent to address psychosis requires considering its efficacy, side-effect profile, and adherence rates, as well as its potential effects on metabolic regulation and weight (Table 1). Typical antipsychotics are less likely than atypical antipsychotics to cause metabolic dysregulation.12 When treatment with atypical antipsychotics cannot be avoided—such as when side effects or an allergic reaction develop—consider selecting a relatively weight-neutral drug with a lower potential for metabolic dysregulation, such as aripiprazole. However, many times, using an agent with significant effects on metabolic regulation cannot be avoided, making treating and monitoring the resulting metabolic effects even more significant.

Glycemic control

Initiating an agent for glycemic control in persons with newly diagnosed diabetes requires weighing many factors, including mode of delivery (oral or subcutaneous), level of glycemic control required, comorbid medical illness (such as renal impairment and heart failure), cost, and potential long-term side effects of the medication (Table 2).13 Oral agents have a slower effect on lowering the blood glucose level, and each agent carries contraindications, but generally they are more affordable. Many present a low risk of hypoglycemia but sulfonylureas are an exception. In addition, metformin could lead to weight loss over the long term, which further lowers the risk of diabetes.

If, however, tight and immediate glycemic control is needed, subcutaneous insulin injections might be required, although this method is more costly, carries an increased risk of hypoglycemic episodes acutely, and leads to weight gain in the long run because of induced hunger and increased appetite.

Psychosocial factors

In addition to the clinical variables above, treating diabetes in patients with comorbid schizophrenia requires considering other psychosocial factors that might not be readily apparent (Table 3). For example, patients with schizophrenia might have decreased motivation, self-efficacy, and capacity for self-care when it comes to health maintenance and medication adherence.14 Chronically mentally ill persons might have reduced cognitive functioning that could affect their ability to maintain complicated medication regimens, such as administering insulin and monitoring blood glucose.

In addition, easy access to hypodermic needles and large amounts of insulin could become a safety concern in patients with ongoing hallucinations, delusions, and thought disorder, despite antipsychotic treatment. For example, a patient with schizophrenia and diabetes who has been maintained on insulin might begin hearing voices that tell her to inject her eyeballs with insulin. Similarly, although the risk of hypoglycemic episodes in patients treated with insulin is well known, patients with schizophrenia have a higher risk of acute complications of diabetes than other patients with diabetes.15Psychosocial factors, such as placement, support system, and follow-up care need to be considered. In some instances, the need to administer daily subcutaneous insulin could be a barrier to placement if the facility does not have the staff or expertise to monitor blood glucose and administer insulin.

If the patient is returning home, then the patient or a caretaker will need to be trained to monitor blood glucose and administer insulin. This might be difficult for persons with chronic mental illness who have lost the support and care of their family. Also, consider the issue of storing insulin, which requires refrigeration. Because of the potential complications involved in using insulin in patients with schizophrenia, practitioners should consider managing non-insulin dependent diabetes with an oral hypoglycemic agent, when possible, along with lifestyle modifications.

OUTCOME Weight loss, discharge

Mr. K is transitioned from aripiprazole to higher-potency oral risperidone, titrated to 6 mg/d. At this dosage, he continues to maintain a delusion about owning a house in Fiji, but was seen responding to internal stimuli less often. The treatment team places him on a diabetic and low-sodium diet of 1,800 kcal/d. His fasting blood glucose levels range in the 70s to 110s mg/dL during his first week of hospitalization.

The treatment team starts Mr. K on oral metformin, titrated to 1,000 mg twice daily, while tapering him off insulin lispro and glargine over the course of hospitalization. The transition from insulin to metformin also is considered because Mr. K’s daily insulin requirement is rather low (<0.5 units/kg).

Mr. K’s course is prolonged because his treatment team initiates the process of conservatorship and placement in the community. Approximately 6 months after his admission, Mr. K is discharged to an unlocked facility with support from an intensive outpatient mental health program. At 6 months follow-up with his outpatient provider, Mr. K’s hemoglobin A1c is 7.0 and he weighs 155 lb with a BMI of 26.5.

The authors’ observations

Despite Mr. K’s initial elevated hemoglobin A1c of 12.7 and weight of 185 lb, over approximately 6 months he experiences a 5.7-unit drop in hemoglobin A1c and weight loss of 30 lb with dietary management and metformin—without the need for other agents. Other options for weight-neutral treatment of T2DM include exenatide, which also is available as a once weekly injectable formulation, canagliflozin, and the gliptins (sitagliptin, saxagliptin, and linagliptin) (Table 4).

Mr. K’s improved control of his diabetes occurred despite initiation of an atypical antipsychotic, which would have been expected to cause additional weight gain and make his diabetes worse secondary to metabolic effects.12 Treatment with metformin in particular has been associated with weight loss in patients with16 and without17 comorbid schizophrenia, including those with antipsychotic-induced weight gain.18-20

Bottom Line

Persons with schizophrenia are at higher risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus for many reasons, including metabolic effects of antipsychotics, reduced cognitive functioning, poor self-care, and limited access to health care. Typical antipsychotics are less likely to cause metabolic dysregulation but, if an atypical is needed, one that is relatively weight-neutral should be selected. When choosing an agent for glycemic control, consider a patient’s or a caretaker’s ability to administer medications, monitor blood glucose, and follow dietary recommendations.

Related Resources

• Cohn T. The link between schizophrenia and diabetes. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(10):28-34,46.

• Annamalai A, Tek C. An overview of diabetes management in schizophrenia patients: office based strategies for primary care practitioners and endocrinologists [published online March 23, 2015]. Int J Endocrinol. 2015;2015:969182. doi: 10.1155/2015/969182.

Drug Brand Names

Amlodipine • Norvasc

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Asenapine • Saphris

Canagliflozin • Invokana

Exenatide • Bydureon, Byetta

Glargine • Lantus

Linagliptin • Tradjenta

Lispro • Humalog

Lurasidone • Latuda

Metformin • Glucophage

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Saxagliptin • Onglyza

Sitagliptin • Januvia

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE Psychotic, and nonadherent

Mr. K, a 42-year-old Fijian man, is brought to the emergency department by his older brother for evaluation of behavioral agitation. Mr. K is belligerent and threatens to kill his family members. Three years earlier, he was given a diagnosis of schizophrenia and treated at an inpatient psychiatric unit.

At that time, Mr. K was stabilized on risperidone, 4 mg/d. However, he did not follow-up with treatment after discharge and has not taken any psychotropic medications since that time.

His brother reports that Mr. K has been slowly deteriorating, talking to himself, staying up at night, and getting into arguments with his family over his delusional beliefs. Although Mr. K once worked as a security guard, he has not worked in 8 years. He has been living with his family, who are no longer willing to accept him into their home because they fear he might harm them.

In the emergency department, Mr. K reports that he has a throbbing headache. Blood pressure is 177/101 mm Hg; heart rate is 103 beats per minute; respiratory rate is 18 breaths per minute; weight is 185 lb; and body mass index (BMI) is 31.8. Physical examination is unremarkable.

Laboratory values show that sodium is 131 mEq/L; potassium, 3.7 mEq/L; bicarbonate, 26 mEq/L; glucose, 420 mg/dL; hemoglobin A1c,12.7; and urine glucose, 3+. Mr. K denies being told he has diabetes.

What are Mr. K’s risk factors for diabetes?

a) schizophrenia

b) physical inactivity

c) obesity

d) Fijian ethnicity

e) all of the above

The authors’ observations

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in persons with schizophrenia or a schizoaffective disorder is twice that of the general population.1-4 Multiple variables contribute to the increased prevalence of diabetes in this population, including genetic predisposition, environmental and cultural factors related to diet and physical activity, a high rate of smoking,5,6 iatrogenic causes (metabolic dysregulation and weight gain from antipsychotic treatment), and socioeconomic factors (poverty, lack of access to health care). In addition, symptoms of psychosis such as thought disorder, delusions, hallucinations, and cognitive decline in persons with chronic schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder can make basic health maintenance difficult.

In Mr. K’s case, premorbid risk of diabetes was elevated because of his Fijian ethnicity.7 With a BMI of 31.8, obesity further increased that risk.5,6,8 In addition, his untreated chronic mental illness, lack of access to health care, low socioeconomic status, long-standing smoking habit, and previous exposure to antipsychotics also increased his risk of T2DM.

The interaction between diabetes and psychosis contributes to a vicious cycle that makes both conditions worse if either, or both, are untreated. In general, medical comorbidities are associated with depression and neurocognitive impairment in persons with schizophrenia.9 Specifically, diabetes is associated with lower global cognitive functioning among persons with schizophrenia.10 Poor cognitive functioning can, in turn, decrease the patient’s ability to manage his medical illness. Also, persons with schizophrenia are less likely to be treated for diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, as in Mr. K’s case.11

How would you treat Mr. K’s newly diagnosed diabetes?

a) refer him to a primary care physician

b) start an oral agent

c) start sliding-scale insulin

d) start long-acting insulin

e) recommend a carbohydrate-controlled diet=

TREATMENT Stabilization

Mr. K is admitted to the medical unit for treatment of hyperglycemia. The team starts him on amlodipine, 5 mg/d, for hypertension; aripiprazole, 10 mg/d, for psychosis; and sliding-scale insulin (lispro) and 20 units of insulin (glargine) nightly for diabetes. Mr. K’s blood glucose level is well regulated on this regimen; after being medically cleared, he is transferred to the inpatient psychiatric unit.

EVALUATION Denies symptoms

Mr. K appears older than his stated age, is poorly groomed, and is dressed in a hospital gown. He is isolated and appears to be internally preoccupied. He repeatedly denies hearing auditory hallucinations, but often is overheard responding to internal stimuli and mumbling indecipherably in a low tone. His speech is decreased and his affect is flat and guarded. He states that he is not “mental” but that he came to the hospital for “tooth pain.” Every day he asks when he can return home and he asks the staff to call his family to take him home. When informed that his family is not able to care for him, Mr. K states that he would live in a house he owns in Fiji, which his family members state is untrue.

How would you treat Mr. K’s psychosis?

a) continue aripiprazole

b) switch to risperidone, an agent to which he previously responded

c) switch to olanzapine because he has not been sleeping well

d) switch to haloperidol because of diabetes

The authors’ observations

Pharmacotherapy for patients with comorbid schizophrenia and diabetes requires consideration of clinical and psychosocial factors unique to this population.

Antipsychotic choice

Selection of an antipsychotic agent to address psychosis requires considering its efficacy, side-effect profile, and adherence rates, as well as its potential effects on metabolic regulation and weight (Table 1). Typical antipsychotics are less likely than atypical antipsychotics to cause metabolic dysregulation.12 When treatment with atypical antipsychotics cannot be avoided—such as when side effects or an allergic reaction develop—consider selecting a relatively weight-neutral drug with a lower potential for metabolic dysregulation, such as aripiprazole. However, many times, using an agent with significant effects on metabolic regulation cannot be avoided, making treating and monitoring the resulting metabolic effects even more significant.

Glycemic control

Initiating an agent for glycemic control in persons with newly diagnosed diabetes requires weighing many factors, including mode of delivery (oral or subcutaneous), level of glycemic control required, comorbid medical illness (such as renal impairment and heart failure), cost, and potential long-term side effects of the medication (Table 2).13 Oral agents have a slower effect on lowering the blood glucose level, and each agent carries contraindications, but generally they are more affordable. Many present a low risk of hypoglycemia but sulfonylureas are an exception. In addition, metformin could lead to weight loss over the long term, which further lowers the risk of diabetes.

If, however, tight and immediate glycemic control is needed, subcutaneous insulin injections might be required, although this method is more costly, carries an increased risk of hypoglycemic episodes acutely, and leads to weight gain in the long run because of induced hunger and increased appetite.

Psychosocial factors

In addition to the clinical variables above, treating diabetes in patients with comorbid schizophrenia requires considering other psychosocial factors that might not be readily apparent (Table 3). For example, patients with schizophrenia might have decreased motivation, self-efficacy, and capacity for self-care when it comes to health maintenance and medication adherence.14 Chronically mentally ill persons might have reduced cognitive functioning that could affect their ability to maintain complicated medication regimens, such as administering insulin and monitoring blood glucose.

In addition, easy access to hypodermic needles and large amounts of insulin could become a safety concern in patients with ongoing hallucinations, delusions, and thought disorder, despite antipsychotic treatment. For example, a patient with schizophrenia and diabetes who has been maintained on insulin might begin hearing voices that tell her to inject her eyeballs with insulin. Similarly, although the risk of hypoglycemic episodes in patients treated with insulin is well known, patients with schizophrenia have a higher risk of acute complications of diabetes than other patients with diabetes.15Psychosocial factors, such as placement, support system, and follow-up care need to be considered. In some instances, the need to administer daily subcutaneous insulin could be a barrier to placement if the facility does not have the staff or expertise to monitor blood glucose and administer insulin.

If the patient is returning home, then the patient or a caretaker will need to be trained to monitor blood glucose and administer insulin. This might be difficult for persons with chronic mental illness who have lost the support and care of their family. Also, consider the issue of storing insulin, which requires refrigeration. Because of the potential complications involved in using insulin in patients with schizophrenia, practitioners should consider managing non-insulin dependent diabetes with an oral hypoglycemic agent, when possible, along with lifestyle modifications.

OUTCOME Weight loss, discharge

Mr. K is transitioned from aripiprazole to higher-potency oral risperidone, titrated to 6 mg/d. At this dosage, he continues to maintain a delusion about owning a house in Fiji, but was seen responding to internal stimuli less often. The treatment team places him on a diabetic and low-sodium diet of 1,800 kcal/d. His fasting blood glucose levels range in the 70s to 110s mg/dL during his first week of hospitalization.

The treatment team starts Mr. K on oral metformin, titrated to 1,000 mg twice daily, while tapering him off insulin lispro and glargine over the course of hospitalization. The transition from insulin to metformin also is considered because Mr. K’s daily insulin requirement is rather low (<0.5 units/kg).

Mr. K’s course is prolonged because his treatment team initiates the process of conservatorship and placement in the community. Approximately 6 months after his admission, Mr. K is discharged to an unlocked facility with support from an intensive outpatient mental health program. At 6 months follow-up with his outpatient provider, Mr. K’s hemoglobin A1c is 7.0 and he weighs 155 lb with a BMI of 26.5.

The authors’ observations

Despite Mr. K’s initial elevated hemoglobin A1c of 12.7 and weight of 185 lb, over approximately 6 months he experiences a 5.7-unit drop in hemoglobin A1c and weight loss of 30 lb with dietary management and metformin—without the need for other agents. Other options for weight-neutral treatment of T2DM include exenatide, which also is available as a once weekly injectable formulation, canagliflozin, and the gliptins (sitagliptin, saxagliptin, and linagliptin) (Table 4).

Mr. K’s improved control of his diabetes occurred despite initiation of an atypical antipsychotic, which would have been expected to cause additional weight gain and make his diabetes worse secondary to metabolic effects.12 Treatment with metformin in particular has been associated with weight loss in patients with16 and without17 comorbid schizophrenia, including those with antipsychotic-induced weight gain.18-20

Bottom Line

Persons with schizophrenia are at higher risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus for many reasons, including metabolic effects of antipsychotics, reduced cognitive functioning, poor self-care, and limited access to health care. Typical antipsychotics are less likely to cause metabolic dysregulation but, if an atypical is needed, one that is relatively weight-neutral should be selected. When choosing an agent for glycemic control, consider a patient’s or a caretaker’s ability to administer medications, monitor blood glucose, and follow dietary recommendations.

Related Resources

• Cohn T. The link between schizophrenia and diabetes. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(10):28-34,46.

• Annamalai A, Tek C. An overview of diabetes management in schizophrenia patients: office based strategies for primary care practitioners and endocrinologists [published online March 23, 2015]. Int J Endocrinol. 2015;2015:969182. doi: 10.1155/2015/969182.

Drug Brand Names

Amlodipine • Norvasc

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Asenapine • Saphris

Canagliflozin • Invokana

Exenatide • Bydureon, Byetta

Glargine • Lantus

Linagliptin • Tradjenta

Lispro • Humalog

Lurasidone • Latuda

Metformin • Glucophage

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Saxagliptin • Onglyza

Sitagliptin • Januvia

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. American Diabetes Association; American Psychiatric Association; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; North American Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):596-601.

2. Heald A. Physical health in schizophrenia: a challenge for antipsychotic therapy. Eur Psychiatry. 2010;25(suppl 2):S6-S11.

3. El-Mallakh P. Doing my best: poverty and self-care among individuals with schizophrenia and diabetes mellitus. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2007;21(1):49-60; discussion 61-63.

4. Rouillon F, Sorbara F. Schizophrenia and diabetes: epidemiological data. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20(suppl 4):S345-S348.

5. Willi C, Bodenmann P, Ghali WA, et al. Active smoking and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2007;298(22):2654-2664.

6. Dome P, Lazary J, Kalapos MP, et al. Smoking, nicotine and neuropsychiatric disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;34(3):295-342.

7. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. For people of African, Mediterranean, or Southeast Asian heritage: important information about diabetes blood tests. http://www.diabetes.niddk.nih.gov/dm/ pubs/asianamerican/index.htm. Published October 2011. Accessed November 18, 2015.

8. Shaten BJ, Smith GD, Kuller LH, et al. Risk factors for the development of type 2 diabetes among men enrolled in the usual care group of the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Diabetes Care. 1993;16(10):1331-1339.

9. Chwastiak LA, Rosenheck RA, McEvoy JP, et al. Interrelationships of psychiatric symptom severity, medical comorbidity, and functioning in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(8):1102-1109.

10. Takayanagi Y, Cascella NG, Sawa A, et al. Diabetes is associated with lower global cognitive function in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;142(1-3):183-187.

11. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

12. Meyer JM, Davis VG, Goff DC, et al. Change in metabolic syndrome parameters with antipsychotic treatment in the CATIE Schizophrenia Trial: prospective data from phase 1. Schizophr Res. 2008;101(1-3):273-286.

13. Inzucchi SE. Clinical practice. Management of hyperglycemia in the hospital setting. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355(18):1903-1911.

14. Chen SR, Chien YP, Kang CM, et al. Comparing self-efficacy and self-care behaviours between outpatients with comorbid schizophrenia and type 2 diabetes and outpatients with only type 2 diabetes. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2014;21(5):414-422.

15. Becker T, Hux J. Risk of acute complications of diabetes among people with schizophrenia in Ontario, Canada. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(2):398-402.

16. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Long-term safety, tolerability, and weight loss associated with metformin in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(4):731-737.

17. Jarskog LF, Hamer RM, Catellier DJ, et al; METS Investigators. Metformin for weight loss and metabolic control in overweight outpatients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1032-1040.

18. Chen CH, Huang MC, Kao CF, et al. Effects of adjunctive metformin on metabolic traits in nondiabetic clozapine-treated patients with schizophrenia and the effect of metformin discontinuation on body weight: a 24-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(5):e424-430. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08186.

19. Wang M, Tong JH, Zhu G, et al. Metformin for treatment of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2012;138(1):54-57.

20. Mizuno Y, Suzuki T, Nakagawa A, et al. Pharmacological strategies to counteract antipsychotic-induced weight gain and metabolic adverse effects in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(6): 1385-1403.

1. American Diabetes Association; American Psychiatric Association; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists; North American Association for the Study of Obesity. Consensus development conference on antipsychotic drugs and obesity and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):596-601.

2. Heald A. Physical health in schizophrenia: a challenge for antipsychotic therapy. Eur Psychiatry. 2010;25(suppl 2):S6-S11.

3. El-Mallakh P. Doing my best: poverty and self-care among individuals with schizophrenia and diabetes mellitus. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2007;21(1):49-60; discussion 61-63.

4. Rouillon F, Sorbara F. Schizophrenia and diabetes: epidemiological data. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20(suppl 4):S345-S348.

5. Willi C, Bodenmann P, Ghali WA, et al. Active smoking and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2007;298(22):2654-2664.

6. Dome P, Lazary J, Kalapos MP, et al. Smoking, nicotine and neuropsychiatric disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;34(3):295-342.

7. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. For people of African, Mediterranean, or Southeast Asian heritage: important information about diabetes blood tests. http://www.diabetes.niddk.nih.gov/dm/ pubs/asianamerican/index.htm. Published October 2011. Accessed November 18, 2015.

8. Shaten BJ, Smith GD, Kuller LH, et al. Risk factors for the development of type 2 diabetes among men enrolled in the usual care group of the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Diabetes Care. 1993;16(10):1331-1339.

9. Chwastiak LA, Rosenheck RA, McEvoy JP, et al. Interrelationships of psychiatric symptom severity, medical comorbidity, and functioning in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(8):1102-1109.

10. Takayanagi Y, Cascella NG, Sawa A, et al. Diabetes is associated with lower global cognitive function in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;142(1-3):183-187.

11. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

12. Meyer JM, Davis VG, Goff DC, et al. Change in metabolic syndrome parameters with antipsychotic treatment in the CATIE Schizophrenia Trial: prospective data from phase 1. Schizophr Res. 2008;101(1-3):273-286.

13. Inzucchi SE. Clinical practice. Management of hyperglycemia in the hospital setting. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355(18):1903-1911.

14. Chen SR, Chien YP, Kang CM, et al. Comparing self-efficacy and self-care behaviours between outpatients with comorbid schizophrenia and type 2 diabetes and outpatients with only type 2 diabetes. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2014;21(5):414-422.

15. Becker T, Hux J. Risk of acute complications of diabetes among people with schizophrenia in Ontario, Canada. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(2):398-402.

16. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Long-term safety, tolerability, and weight loss associated with metformin in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(4):731-737.

17. Jarskog LF, Hamer RM, Catellier DJ, et al; METS Investigators. Metformin for weight loss and metabolic control in overweight outpatients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1032-1040.

18. Chen CH, Huang MC, Kao CF, et al. Effects of adjunctive metformin on metabolic traits in nondiabetic clozapine-treated patients with schizophrenia and the effect of metformin discontinuation on body weight: a 24-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(5):e424-430. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08186.

19. Wang M, Tong JH, Zhu G, et al. Metformin for treatment of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2012;138(1):54-57.

20. Mizuno Y, Suzuki T, Nakagawa A, et al. Pharmacological strategies to counteract antipsychotic-induced weight gain and metabolic adverse effects in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(6): 1385-1403.