User login

The jealous insomniac

CASE Anxious and jealous

Mrs. H, age 28, presents to the emergency department (ED) with pressured speech, emotional lability, loose associations, and echolalia. On physical examination, Mrs. H is noted to have hand tremors. Mrs. H says she has not slept for the past 5 days and is experiencing anxiety and heart palpitations.

She also says that for the past 2 years she has believed that her husband is having an affair with her best friend. However, her current presentation—which she attributes to the alleged affair—began a week before she came to the ED. According to her husband, Mrs. H was “perfectly fine until a week ago” and her symptoms “appeared out of nowhere.” He reports that this has never happened before.

Mrs. H is admitted to the psychiatry unit. The nursing team reports that on the first night, Mrs. H was “running and screaming on the unit, out of control,” and was “tearful, manicky, and dysphoric.”

Mrs. H has no significant medical or psychiatric history. Her family history is significant for hyperthyroidism in her mother and maternal grandmother. Mrs. H says she smokes cigarettes (1 pack/d) but denies alcohol or illicit drug use.

EVALUATION A telling thyroid panel

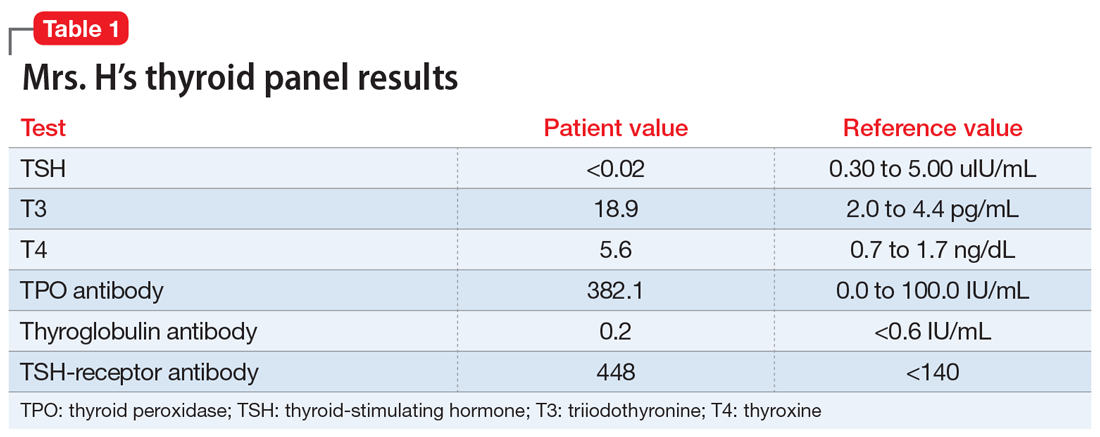

Mrs. H undergoes laboratory testing, including a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and thyroid panel due to her family history of thyroid-related disorders. The thyroid panel shows the presence of the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) receptor antibody; a low TSH level; elevated triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) levels, with T3 > T4; elevated thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibody; and elevated thyroglobulin antibody (Table 1). A scan shows the thyroid gland to be normal/top-normal size and is read by radiology to be indicative of a resolving thyroiditis vs Graves’ disease. An electrocardiogram indicates a heart rate of 139 beats per minute.

[polldaddy:10352133]

The authors’ observations

Mrs. H fits the presentation of psychosis secondary to Graves’ disease. However, our differential consisted of thyroiditis, brief psychotic disorder, delusional disorder (jealous type), and bipolar mania.

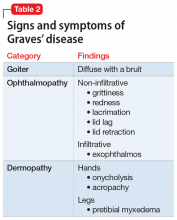

Brief psychotic disorder, bipolar mania, and delusional disorder were better explained by Graves’ disease, and Mrs. H’s jealous delusion resulted in functional impairment, which eliminated delusional disorder. Her family history of hyperthyroidism, as well as her sex and history of tobacco use, supported the diagnosis of Graves’ disease. Although Mrs. H did not experience goiter, ophthalmopathy, or dermopathy, which are common signs and symptoms of Graves’ disease (Table 2), she did present with irritability, insomnia, tachycardia, and a hand tremor. Her psychiatric symptoms included anxiety, emotional lability and, most importantly, psychosis. Her laboratory results included the presence of the TSH-receptor antibody, a low TSH level, and elevated T3 and T4 levels (T3>T4), confirming the diagnosis of early-onset Graves’ disease.

Continue to: Graves' disease

Graves’ disease

Graves’ disease is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism, representing approximately 50% to 80% of cases.1 Graves’ disease occurs most often in women, smokers, and those with a personal or family history of autoimmune disease; although patients of any age may be affected, the peak incidence occurs between age 40 and 60.1

Graves’ disease results from the production of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies that activate the TSH receptor on the surface of thyroid follicular cells.1 The presence of the TSH-receptor antibody, in addition to a low TSH and elevated T3 and T4 levels (T3>T4), are common laboratory findings in patients with this disease. A thyroid scan will also show increased radiotracer accumulation.

Patients with Graves’ disease, as well as those with hyperthyroidism, tend to report weight loss, increased appetite, heat intolerance, irritability, insomnia, and palpitations. In addition to the above symptoms, the identifying signs and symptoms of Graves’ disease include a goiter, ophthalmopathy, and dermopathy (Table 2). Rarely, patients with Graves’ disease can present with psychosis, which is often complicated by thyrotoxicosis.2

[polldaddy:10352135]

TREATMENT Antipsychotic and a beta blocker

Based on her signs, symptoms, and laboratory findings, Mrs. H receives risperidone, 1 mg twice daily, for psychosis, and atenolol, 25 mg twice daily, for heart palpitations. Over 4 days, her symptoms decrease; she experiences more linear thought and decreased flight-of-ideas, and becomes unsure about the truth of her husband’s alleged affair. Her impulsive behaviors and severe mood lability cease. Her tachycardia remains controlled with atenolol.

The authors’ observations

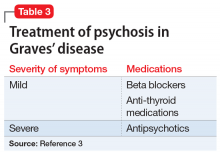

Rapid initiation of treatment is important when managing patients with Graves’ disease, because untreated patients have a higher risk of psychiatric illness, cardiac disease, arrhythmia, and sudden cardiac death.1 Patients with Graves’ disease typically are treated with thionamides, radioactive iodine, and/or surgery. When a patient presents with psychosis as a result of thyrotoxicosis, treatment focuses on improving the thyrotoxicosis through anti-thyroid medications and beta blockers (Table 33). Psychotropic medications, such as antipsychotics, are not indicated for primary treatment, but are given to patients who have severe psychosis until symptoms have resolved.3 For Mrs. H, the severity of her psychosis necessitated risperidone in addition to atenolol.

OUTCOME Continuous medical management; no ablation

Mrs. H is discharged with immediate outpatient follow-up with an endocrinology team to discuss the best long-term management of her thyroiditis. Mrs. H opts for continuous medical management (as opposed to ablation) and is administered methimazole, 15 mg/d, to treat Graves’ disease.

The authors’ observations

This case provides useful information regarding recognizing psychosis as the initial sign of Graves’ disease. Although Graves’ disease represents 50% to 80% of cases of hyperthyroidism,1 psychosis as the first clinical presentation of this disease is extremely rare. Several case reports, however, have described this phenomenon,2,3 and further studies would be helpful to determine its true prevalence.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Although extremely rare, psychosis as the initial clinical presentation of Graves’ disease can occur. The early diagnosis of Graves’ disease is critical to prevent cardiovascular implications and death.

Related Resources

- Abraham P, Acharya S. Current and emerging treatment options for Graves’ hyperthyroidism. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2010;6:29-40.

- Bunevicius R, Prange AJ Jr. Psychiatric manifestations of Graves’ hyperthyroidism: pathophysiology and treatment options. CNS Drugs. 2006;20(11):897-909.

- Ginsberg J. Diagnosis and management of Graves’ disease. CMAJ. 2003;168(5):575-585.

Drug Brand Names

Atenolol • Tenormin

Methimazole • Tapazole

Risperidone • Risperdal

1. Girgis C, Champion B, Wall J. Current concepts in Graves’ disease. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2011;2(3):135-144.

2. Urias-Uribe L, Valdez-Solis E, González-Milán C, et al. Psychosis crisis associated with thyrotoxicosis due to Graves’ disease. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2017;2017:6803682. doi: 10.1155/2017/6803682.

3. Ugwu ET, Maluze J, Onyebueke GC. Graves’ thyrotoxicosis presenting as schizophreniform psychosis: a case report and literature review. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2017;15(1):e41977. doi: 10.5812/ijem.41977.

CASE Anxious and jealous

Mrs. H, age 28, presents to the emergency department (ED) with pressured speech, emotional lability, loose associations, and echolalia. On physical examination, Mrs. H is noted to have hand tremors. Mrs. H says she has not slept for the past 5 days and is experiencing anxiety and heart palpitations.

She also says that for the past 2 years she has believed that her husband is having an affair with her best friend. However, her current presentation—which she attributes to the alleged affair—began a week before she came to the ED. According to her husband, Mrs. H was “perfectly fine until a week ago” and her symptoms “appeared out of nowhere.” He reports that this has never happened before.

Mrs. H is admitted to the psychiatry unit. The nursing team reports that on the first night, Mrs. H was “running and screaming on the unit, out of control,” and was “tearful, manicky, and dysphoric.”

Mrs. H has no significant medical or psychiatric history. Her family history is significant for hyperthyroidism in her mother and maternal grandmother. Mrs. H says she smokes cigarettes (1 pack/d) but denies alcohol or illicit drug use.

EVALUATION A telling thyroid panel

Mrs. H undergoes laboratory testing, including a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and thyroid panel due to her family history of thyroid-related disorders. The thyroid panel shows the presence of the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) receptor antibody; a low TSH level; elevated triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) levels, with T3 > T4; elevated thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibody; and elevated thyroglobulin antibody (Table 1). A scan shows the thyroid gland to be normal/top-normal size and is read by radiology to be indicative of a resolving thyroiditis vs Graves’ disease. An electrocardiogram indicates a heart rate of 139 beats per minute.

[polldaddy:10352133]

The authors’ observations

Mrs. H fits the presentation of psychosis secondary to Graves’ disease. However, our differential consisted of thyroiditis, brief psychotic disorder, delusional disorder (jealous type), and bipolar mania.

Brief psychotic disorder, bipolar mania, and delusional disorder were better explained by Graves’ disease, and Mrs. H’s jealous delusion resulted in functional impairment, which eliminated delusional disorder. Her family history of hyperthyroidism, as well as her sex and history of tobacco use, supported the diagnosis of Graves’ disease. Although Mrs. H did not experience goiter, ophthalmopathy, or dermopathy, which are common signs and symptoms of Graves’ disease (Table 2), she did present with irritability, insomnia, tachycardia, and a hand tremor. Her psychiatric symptoms included anxiety, emotional lability and, most importantly, psychosis. Her laboratory results included the presence of the TSH-receptor antibody, a low TSH level, and elevated T3 and T4 levels (T3>T4), confirming the diagnosis of early-onset Graves’ disease.

Continue to: Graves' disease

Graves’ disease

Graves’ disease is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism, representing approximately 50% to 80% of cases.1 Graves’ disease occurs most often in women, smokers, and those with a personal or family history of autoimmune disease; although patients of any age may be affected, the peak incidence occurs between age 40 and 60.1

Graves’ disease results from the production of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies that activate the TSH receptor on the surface of thyroid follicular cells.1 The presence of the TSH-receptor antibody, in addition to a low TSH and elevated T3 and T4 levels (T3>T4), are common laboratory findings in patients with this disease. A thyroid scan will also show increased radiotracer accumulation.

Patients with Graves’ disease, as well as those with hyperthyroidism, tend to report weight loss, increased appetite, heat intolerance, irritability, insomnia, and palpitations. In addition to the above symptoms, the identifying signs and symptoms of Graves’ disease include a goiter, ophthalmopathy, and dermopathy (Table 2). Rarely, patients with Graves’ disease can present with psychosis, which is often complicated by thyrotoxicosis.2

[polldaddy:10352135]

TREATMENT Antipsychotic and a beta blocker

Based on her signs, symptoms, and laboratory findings, Mrs. H receives risperidone, 1 mg twice daily, for psychosis, and atenolol, 25 mg twice daily, for heart palpitations. Over 4 days, her symptoms decrease; she experiences more linear thought and decreased flight-of-ideas, and becomes unsure about the truth of her husband’s alleged affair. Her impulsive behaviors and severe mood lability cease. Her tachycardia remains controlled with atenolol.

The authors’ observations

Rapid initiation of treatment is important when managing patients with Graves’ disease, because untreated patients have a higher risk of psychiatric illness, cardiac disease, arrhythmia, and sudden cardiac death.1 Patients with Graves’ disease typically are treated with thionamides, radioactive iodine, and/or surgery. When a patient presents with psychosis as a result of thyrotoxicosis, treatment focuses on improving the thyrotoxicosis through anti-thyroid medications and beta blockers (Table 33). Psychotropic medications, such as antipsychotics, are not indicated for primary treatment, but are given to patients who have severe psychosis until symptoms have resolved.3 For Mrs. H, the severity of her psychosis necessitated risperidone in addition to atenolol.

OUTCOME Continuous medical management; no ablation

Mrs. H is discharged with immediate outpatient follow-up with an endocrinology team to discuss the best long-term management of her thyroiditis. Mrs. H opts for continuous medical management (as opposed to ablation) and is administered methimazole, 15 mg/d, to treat Graves’ disease.

The authors’ observations

This case provides useful information regarding recognizing psychosis as the initial sign of Graves’ disease. Although Graves’ disease represents 50% to 80% of cases of hyperthyroidism,1 psychosis as the first clinical presentation of this disease is extremely rare. Several case reports, however, have described this phenomenon,2,3 and further studies would be helpful to determine its true prevalence.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Although extremely rare, psychosis as the initial clinical presentation of Graves’ disease can occur. The early diagnosis of Graves’ disease is critical to prevent cardiovascular implications and death.

Related Resources

- Abraham P, Acharya S. Current and emerging treatment options for Graves’ hyperthyroidism. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2010;6:29-40.

- Bunevicius R, Prange AJ Jr. Psychiatric manifestations of Graves’ hyperthyroidism: pathophysiology and treatment options. CNS Drugs. 2006;20(11):897-909.

- Ginsberg J. Diagnosis and management of Graves’ disease. CMAJ. 2003;168(5):575-585.

Drug Brand Names

Atenolol • Tenormin

Methimazole • Tapazole

Risperidone • Risperdal

CASE Anxious and jealous

Mrs. H, age 28, presents to the emergency department (ED) with pressured speech, emotional lability, loose associations, and echolalia. On physical examination, Mrs. H is noted to have hand tremors. Mrs. H says she has not slept for the past 5 days and is experiencing anxiety and heart palpitations.

She also says that for the past 2 years she has believed that her husband is having an affair with her best friend. However, her current presentation—which she attributes to the alleged affair—began a week before she came to the ED. According to her husband, Mrs. H was “perfectly fine until a week ago” and her symptoms “appeared out of nowhere.” He reports that this has never happened before.

Mrs. H is admitted to the psychiatry unit. The nursing team reports that on the first night, Mrs. H was “running and screaming on the unit, out of control,” and was “tearful, manicky, and dysphoric.”

Mrs. H has no significant medical or psychiatric history. Her family history is significant for hyperthyroidism in her mother and maternal grandmother. Mrs. H says she smokes cigarettes (1 pack/d) but denies alcohol or illicit drug use.

EVALUATION A telling thyroid panel

Mrs. H undergoes laboratory testing, including a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and thyroid panel due to her family history of thyroid-related disorders. The thyroid panel shows the presence of the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) receptor antibody; a low TSH level; elevated triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) levels, with T3 > T4; elevated thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibody; and elevated thyroglobulin antibody (Table 1). A scan shows the thyroid gland to be normal/top-normal size and is read by radiology to be indicative of a resolving thyroiditis vs Graves’ disease. An electrocardiogram indicates a heart rate of 139 beats per minute.

[polldaddy:10352133]

The authors’ observations

Mrs. H fits the presentation of psychosis secondary to Graves’ disease. However, our differential consisted of thyroiditis, brief psychotic disorder, delusional disorder (jealous type), and bipolar mania.

Brief psychotic disorder, bipolar mania, and delusional disorder were better explained by Graves’ disease, and Mrs. H’s jealous delusion resulted in functional impairment, which eliminated delusional disorder. Her family history of hyperthyroidism, as well as her sex and history of tobacco use, supported the diagnosis of Graves’ disease. Although Mrs. H did not experience goiter, ophthalmopathy, or dermopathy, which are common signs and symptoms of Graves’ disease (Table 2), she did present with irritability, insomnia, tachycardia, and a hand tremor. Her psychiatric symptoms included anxiety, emotional lability and, most importantly, psychosis. Her laboratory results included the presence of the TSH-receptor antibody, a low TSH level, and elevated T3 and T4 levels (T3>T4), confirming the diagnosis of early-onset Graves’ disease.

Continue to: Graves' disease

Graves’ disease

Graves’ disease is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism, representing approximately 50% to 80% of cases.1 Graves’ disease occurs most often in women, smokers, and those with a personal or family history of autoimmune disease; although patients of any age may be affected, the peak incidence occurs between age 40 and 60.1

Graves’ disease results from the production of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies that activate the TSH receptor on the surface of thyroid follicular cells.1 The presence of the TSH-receptor antibody, in addition to a low TSH and elevated T3 and T4 levels (T3>T4), are common laboratory findings in patients with this disease. A thyroid scan will also show increased radiotracer accumulation.

Patients with Graves’ disease, as well as those with hyperthyroidism, tend to report weight loss, increased appetite, heat intolerance, irritability, insomnia, and palpitations. In addition to the above symptoms, the identifying signs and symptoms of Graves’ disease include a goiter, ophthalmopathy, and dermopathy (Table 2). Rarely, patients with Graves’ disease can present with psychosis, which is often complicated by thyrotoxicosis.2

[polldaddy:10352135]

TREATMENT Antipsychotic and a beta blocker

Based on her signs, symptoms, and laboratory findings, Mrs. H receives risperidone, 1 mg twice daily, for psychosis, and atenolol, 25 mg twice daily, for heart palpitations. Over 4 days, her symptoms decrease; she experiences more linear thought and decreased flight-of-ideas, and becomes unsure about the truth of her husband’s alleged affair. Her impulsive behaviors and severe mood lability cease. Her tachycardia remains controlled with atenolol.

The authors’ observations

Rapid initiation of treatment is important when managing patients with Graves’ disease, because untreated patients have a higher risk of psychiatric illness, cardiac disease, arrhythmia, and sudden cardiac death.1 Patients with Graves’ disease typically are treated with thionamides, radioactive iodine, and/or surgery. When a patient presents with psychosis as a result of thyrotoxicosis, treatment focuses on improving the thyrotoxicosis through anti-thyroid medications and beta blockers (Table 33). Psychotropic medications, such as antipsychotics, are not indicated for primary treatment, but are given to patients who have severe psychosis until symptoms have resolved.3 For Mrs. H, the severity of her psychosis necessitated risperidone in addition to atenolol.

OUTCOME Continuous medical management; no ablation

Mrs. H is discharged with immediate outpatient follow-up with an endocrinology team to discuss the best long-term management of her thyroiditis. Mrs. H opts for continuous medical management (as opposed to ablation) and is administered methimazole, 15 mg/d, to treat Graves’ disease.

The authors’ observations

This case provides useful information regarding recognizing psychosis as the initial sign of Graves’ disease. Although Graves’ disease represents 50% to 80% of cases of hyperthyroidism,1 psychosis as the first clinical presentation of this disease is extremely rare. Several case reports, however, have described this phenomenon,2,3 and further studies would be helpful to determine its true prevalence.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Although extremely rare, psychosis as the initial clinical presentation of Graves’ disease can occur. The early diagnosis of Graves’ disease is critical to prevent cardiovascular implications and death.

Related Resources

- Abraham P, Acharya S. Current and emerging treatment options for Graves’ hyperthyroidism. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2010;6:29-40.

- Bunevicius R, Prange AJ Jr. Psychiatric manifestations of Graves’ hyperthyroidism: pathophysiology and treatment options. CNS Drugs. 2006;20(11):897-909.

- Ginsberg J. Diagnosis and management of Graves’ disease. CMAJ. 2003;168(5):575-585.

Drug Brand Names

Atenolol • Tenormin

Methimazole • Tapazole

Risperidone • Risperdal

1. Girgis C, Champion B, Wall J. Current concepts in Graves’ disease. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2011;2(3):135-144.

2. Urias-Uribe L, Valdez-Solis E, González-Milán C, et al. Psychosis crisis associated with thyrotoxicosis due to Graves’ disease. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2017;2017:6803682. doi: 10.1155/2017/6803682.

3. Ugwu ET, Maluze J, Onyebueke GC. Graves’ thyrotoxicosis presenting as schizophreniform psychosis: a case report and literature review. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2017;15(1):e41977. doi: 10.5812/ijem.41977.

1. Girgis C, Champion B, Wall J. Current concepts in Graves’ disease. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2011;2(3):135-144.

2. Urias-Uribe L, Valdez-Solis E, González-Milán C, et al. Psychosis crisis associated with thyrotoxicosis due to Graves’ disease. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2017;2017:6803682. doi: 10.1155/2017/6803682.

3. Ugwu ET, Maluze J, Onyebueke GC. Graves’ thyrotoxicosis presenting as schizophreniform psychosis: a case report and literature review. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2017;15(1):e41977. doi: 10.5812/ijem.41977.