User login

Depressed and cognitively impaired

CASE Depressed and anxious

Five years ago, Ms. X, age 60, was diagnosed with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (MDD) with anxiety. This diagnosis was established by a previous psychiatrist. She presents to a clinic for a second opinion.

Since her diagnosis, Ms. X has experienced sad mood, anhedonia, difficulty falling asleep, increased appetite and weight, and decreased concentration and attention. Her anxiety stems from her inability to work, which causes her to worry about her children. In the clinic, the treatment team conducts the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 item scale (GAD-7) with Ms. X. She scores 16 on the PHQ-9, indicating moderately severe depression, and scores 12 on the GAD-7, indicating moderate anxiety.

Ms. X’s current medication regimen consists of venlafaxine extended-release (XR) 225 mg/d, trazodone 100 mg/d at bedtime, and clonazepam 1 mg twice daily. She reports no significant improvement of her symptoms from these medications. Additionally, Ms. X reports that in the past she had been prescribed fluoxetine, citalopram, and duloxetine, but she cannot recall the dosages.

Ms. X appears appropriately groomed, maintains appropriate eye contact, has clear speech, and does not show evidence of internal stimulation; however, she has difficulty following instructions. She makes negative comments about herself such as “I’m worthless” and “Nobody cares about me.” The treatment team decides to taper Ms. X off venlafaxine XR and initiates sertraline 50 mg/d, while continuing trazodone 50 mg/d at bedtime and clonazepam 1 mg twice daily. The team refers her for cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) to address her cognitive distortions, sad mood, and anxiety. Ms. X is asked to follow up with Psychiatry in 1 week.

EVALUATION Unusual behavior

At her CBT intake, Ms. X endorses depression and anxiety. Her PHQ-9 score at this visit is 19 (moderately severe depression) and GAD-7 score is 16 (severe anxiety). The psychologist notes that Ms. X is able to complete activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living without assistance. Ms. X denies any use of illicit substances or alcohol. No gross memory impairment is noted during this appointment, though Ms. X exhibits unusual behavior, including exiting and re-entering the clinic multiple times to repeatedly ask about follow-up appointments. The psychologist concludes that Ms. X’s presentation and behavior can be explained by MDD and pseudodementia.

[polldaddy:12189562]

The authors’ observations

Pseudodementia gained recognition in clinical research >100 years ago.1 Officially coined by Kiloh in 1961, the term was used broadly to categorize psychiatric cases that present like dementia but are the result of reversible causes. More recently, it has been used to describe older adults who present with cognitive deficits in the context of depressive symptoms.2 The goal of evaluation is to determine if the primary issue is a cognitive disorder or a depressive episode. DSM-5-TR does not classify pseudodementia as a distinct diagnosis, but instead categorizes its symptoms as components under other major diagnostic categories. Patients can present with MDD and associated cognitive symptoms, or with a cognitive disorder with depressive symptoms, which would be diagnosed as a cognitive disorder with a major depressive-like episode.3

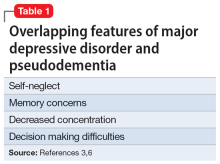

Pseudodementia is rare. Brodaty et al4 found the prevalence of pseudodementia in primary care settings was 0.6%. Older adults (age >65) who live alone are at increased risk of developing pseudodementia, which can be worsened by poor social support and acute psychosocial and environmental changes.5 A key characteristic of this disorder is that as the patient’s depressed mood improves, their memory and cognition also improve.6Table 13,6 outlines overlapping features of MDD and pseudodementia.

Continue to: EVALUATION Worsening depression

EVALUATION Worsening depression

At her Psychiatry follow-up appointment, Ms. X reports that her mood is worse since she ended the relationship with her partner and she feels anxious because the partner was financially supporting her. Her PHQ-9 score is 24 (severe depression) and her GAD-7 score is 12 (moderate anxiety). Ms. X reports tolerating her transition from venlafaxine XR 225 mg/d to sertraline 50 mg/d well.

Additionally, Ms. X reports her children have called her “useless” since she continues to have difficulties following through on household tasks, even though she has no physical impairments that prevent her from completing them. The Psychiatry team observes that Ms. X has no problems walking or moving her arms or legs.

The Psychiatry team administers the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). Ms. X scores 22, indicating mild impairment.

The team recommends a neuropsychological assessment to determine if this MoCA score is due to a cognitive disorder or is rooted in her mood symptoms. The team also recommends an MRI of the brain, complete blood count (CBC), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), and urinalysis (UA).

[polldaddy:12189567]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

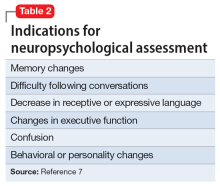

Neuropsychological assessments are important tools for exploring the behavioral manifestations of brain dysfunction (Table 2).7 These assessments factor in elements of neurology, psychiatry, and psychology to provide information about the diagnosis, prognosis, and functional status of patients with medical conditions, especially those with neurocognitive and psychiatric disorders. They combine information from the patient and collateral interviews, behavioral observations, a review of patient records, and objective tests of motor, emotional, and cognitive function.

Among other uses, neuropsychological assessments can help identify depression in patients with neurologic impairment, determine the diagnosis and plan of care for patients with concussions, determine the risk of a motor vehicle crash in patients with cognitive impairment, and distinguish Alzheimer disease from vascular dementia.8 Components of such assessments include the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) to assess anxiety, the Dementia Rating Scale-2 and Neuropsychological Assessment Battery-Screening Module to assess dementia, and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) to assess depression.9

EVALUATION Continued cognitive decline

A different psychologist performs the neuropsychological assessment, who conducts the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status Update to determine if Ms. X is experiencing cognitive impairment. Her immediate memory, visuospatial/constructions, language, attention, and delayed memory are significantly impaired for someone her age. The psychologist also administers the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale IV and finds Ms. X’s general cognitive ability is within the low average range of intellectual functioning as measured by Full-Scale IQ. Ms. X scores 29 on the BDI-II, indicating significant depressive symptoms, and 13 on the BAI, indicating mild anxiety symptoms.

Ms. X is diagnosed with MDD and an unspecified neurocognitive disorder. The psychologist recommends she start CBT to address her mood and anxiety symptoms.

Upon reviewing the results with Ms. X, the treatment team again recommends a brain MRI, CBC, CMP, and UA to rule out organic causes of her cognitive decline. Ms. X decides against the MRI and laboratory workup and elects to continue her present medication regimen and CBT.

Several weeks later, Ms. X’s family brings her to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation of worsening mood, decreased personal hygiene, increased irritability, and further cognitive decline. They report she is having an increasingly difficult time remembering things such as where she parked her car. The ED team decides to discontinue clonazepam but continues sertraline and trazodone.

Continue to: CBC, CMP, and UA...

CBC, CMP, and UA are unremarkable. Ms. X undergoes a brain CT scan without contrast, which reveals hyperdense lesions in the inferior left tentorium, posterior fossa. A subsequent brain MRI with contrast reveals a dural-based enhancing mass, inferior to the left tentorium, in the left posterior fossa measuring 2.2 cm x 2.1 cm, suggestive of a meningioma. The team orders a Neurosurgery consult.

[polldaddy:12189571]

The authors’ observations

While most brain tumors are secondary to metastasis, meningiomas are the most common primary CNS tumor. Typically, they are asymptomatic; their diagnosis is often delayed until the patient presents with psychiatric symptoms without any focal neurologic findings. The frontal lobe is the most common location of meningioma. Data from 48 case reports of patients with meningiomas and psychiatric symptoms suggest symptoms do not always correlate with specific brain regions.10,11

Indications for neuroimaging in cases such as Ms. X include an abrupt change in behavior or personality, lack of response to psychiatric treatment, presence of focal neurologic signs, and an unusual psychiatric presentation and development of symptoms.11

TREATMENT Neurosurgery

Neurosurgery recommends and performs a suboccipital craniotomy for biopsy and resection. Ms. X tolerates the procedure well. A meningioma is found in the posterior fossa, near the cerebellar convexity. A biopsy finds no evidence of malignancies.

At her postoperative follow-up appointment several days after the procedure, Ms. X reports new-onset hearing loss and tinnitus.

[polldaddy:12189747]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Patients who require neurosurgery typically already carry a heavy psychiatric burden, which makes it challenging to determine the exact psychiatric consequences of neurosurgery.12-14 For example, research shows that temporal lobe resection and temporal lobectomy for treatment-resistant epilepsy can lead to an exacerbation of baseline psychiatric symptoms and the development of new symptoms (31% to 34%).15,16 However, Bommakanti et al13 found no new psychiatric symptoms after resection of meningiomas, and surgery seemed to play a role in ameliorating psychiatric symptoms in patients with intracranial tumors. Research attempting to document the psychiatric sequelae of neurosurgery has had mixed results, and it is difficult to determine what effects brain surgery has on mental health.

OUTCOME Minimal improvement

Several weeks after neurosurgery, Ms. X and her family report her mood is improved. Her PHQ-9 score improves to 15, but her GAD-7 score increases to 13, 1 point above her previous score.

The treatment team recommends Ms. X continue taking sertraline 50 mg/d and trazodone 50 mg/d at bedtime. Ms. X’s family reports her cognition and memory have not improved; her MoCA score increases by 1 point to 23. The treatment team discusses with Ms. X and her family the possibility that her cognitive problems maybe better explained as a neurocognitive disorder rather than as a result of the meningioma, since her MoCA score has not significantly improved. Ms. X and her family decide to seek a second opinion from a neurologist.

Bottom Line

Pseudodementia is a term used to describe older adults who present with cognitive issues in the context of depressive symptoms. Even in the absence of focal findings, neuroimaging should be considered as part of the workup in patients who continue to experience a progressive decline in mood and cognitive function.

Related Resources

- Moller MD, Parmenter BA, Lane DW. Neuropsychological testing: a useful but underutilized resource. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(11):40-46,51.

- Pollak J. Psychological/neuropsychological testing: when to refer for reexamination. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(9):18- 19,30-31,37. doi:10.12788/cp.0157

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Sertraline • Zoloft

Trazodone • Oleptro

Venlafaxine extended- release • Effexor XR

1. Nussbaum PD. (1994). Pseudodementia: a slow death. Neuropsychol Rev. 1994;4(2):71-90. doi:10.1007/BF01874829

2. Kang H, Zhao F, You L, et al. (2014). Pseudo-dementia: a neuropsychological review. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 17(2):147-154. doi:10.4103/0972-2327.132613

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, text revision. American Psychiatric Association; 2022.

4. Brodaty H, Connors MH. Pseudodementia, pseudo-pseudodementia, and pseudodepression. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2020;12(1):e12027. doi:10.1002/dad2.12027

5. Sekhon S, Marwaha R. Depressive Cognitive Disorders. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559256/

6. Brown WA. Pseudodementia: issues in diagnosis. Psychiatric Times. April 9, 2005. Accessed February 3, 2023. www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/pseudodementia-issues-diagnosis

7. Kulas JF, Naugle RI. (2003). Indications for neuropsychological assessment. Cleve Clin J Med. 2003;70(9):785-792.

8. Braun M, Tupper D, Kaufmann P, et al. Neuropsychological assessment: a valuable tool in the diagnosis and management of neurological, neurodevelopmental, medical, and psychiatric disorders. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2011;24(3):107-114.

9. Michels TC, Tiu AY, Graver CJ. Neuropsychological evaluation in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(5):495-502.

10. Wiemels J, Wrensch M, Claus EB. Epidemiology and etiology of meningioma. J Neurooncol. 2010;99(3):307-314. doi:10.1007/s11060-010-0386-3

11. Gyawali S, Sharma P, Mahapatra A. Meningioma and psychiatric symptoms: an individual patient data analysis. Asian J Psychiatr. 2019;42:94-103. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2019.03.029

12. McAllister TW. Neurobehavioral sequelae of traumatic brain injury: evaluation and management. World Psychiatry. 2008;7(1):3-10. doi:10.1002/j.2051-5545.2008.tb00139.x

13. Bommakanti K, Gaddamanugu P, Alladi S, et al. Pre-operative and post-operative psychiatric manifestations in patients with supratentorial meningiomas. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016;147:24-29. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2016.05.018

14. Devinsky O, Barr WB, Vickrey BG, et al. Changes in depression and anxiety after resective surgery for epilepsy. Neurology. 2005;65(11):1744-1749. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000187114.71524.c3

15. Blumer D, Wakhlu S, Davies K, et al. Psychiatric outcome of temporal lobectomy for epilepsy: incidence and treatment of psychiatric complications. Epilepsia. 1998;39(5):478-486. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01409.x

16. Glosser G, Zwil AS, Glosser DS, et al. Psychiatric aspects of temporal lobe epilepsy before and after anterior temporal lobectomy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68(1):53-58. doi:10.1136/jnnp.68.1.53

CASE Depressed and anxious

Five years ago, Ms. X, age 60, was diagnosed with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (MDD) with anxiety. This diagnosis was established by a previous psychiatrist. She presents to a clinic for a second opinion.

Since her diagnosis, Ms. X has experienced sad mood, anhedonia, difficulty falling asleep, increased appetite and weight, and decreased concentration and attention. Her anxiety stems from her inability to work, which causes her to worry about her children. In the clinic, the treatment team conducts the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 item scale (GAD-7) with Ms. X. She scores 16 on the PHQ-9, indicating moderately severe depression, and scores 12 on the GAD-7, indicating moderate anxiety.

Ms. X’s current medication regimen consists of venlafaxine extended-release (XR) 225 mg/d, trazodone 100 mg/d at bedtime, and clonazepam 1 mg twice daily. She reports no significant improvement of her symptoms from these medications. Additionally, Ms. X reports that in the past she had been prescribed fluoxetine, citalopram, and duloxetine, but she cannot recall the dosages.

Ms. X appears appropriately groomed, maintains appropriate eye contact, has clear speech, and does not show evidence of internal stimulation; however, she has difficulty following instructions. She makes negative comments about herself such as “I’m worthless” and “Nobody cares about me.” The treatment team decides to taper Ms. X off venlafaxine XR and initiates sertraline 50 mg/d, while continuing trazodone 50 mg/d at bedtime and clonazepam 1 mg twice daily. The team refers her for cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) to address her cognitive distortions, sad mood, and anxiety. Ms. X is asked to follow up with Psychiatry in 1 week.

EVALUATION Unusual behavior

At her CBT intake, Ms. X endorses depression and anxiety. Her PHQ-9 score at this visit is 19 (moderately severe depression) and GAD-7 score is 16 (severe anxiety). The psychologist notes that Ms. X is able to complete activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living without assistance. Ms. X denies any use of illicit substances or alcohol. No gross memory impairment is noted during this appointment, though Ms. X exhibits unusual behavior, including exiting and re-entering the clinic multiple times to repeatedly ask about follow-up appointments. The psychologist concludes that Ms. X’s presentation and behavior can be explained by MDD and pseudodementia.

[polldaddy:12189562]

The authors’ observations

Pseudodementia gained recognition in clinical research >100 years ago.1 Officially coined by Kiloh in 1961, the term was used broadly to categorize psychiatric cases that present like dementia but are the result of reversible causes. More recently, it has been used to describe older adults who present with cognitive deficits in the context of depressive symptoms.2 The goal of evaluation is to determine if the primary issue is a cognitive disorder or a depressive episode. DSM-5-TR does not classify pseudodementia as a distinct diagnosis, but instead categorizes its symptoms as components under other major diagnostic categories. Patients can present with MDD and associated cognitive symptoms, or with a cognitive disorder with depressive symptoms, which would be diagnosed as a cognitive disorder with a major depressive-like episode.3

Pseudodementia is rare. Brodaty et al4 found the prevalence of pseudodementia in primary care settings was 0.6%. Older adults (age >65) who live alone are at increased risk of developing pseudodementia, which can be worsened by poor social support and acute psychosocial and environmental changes.5 A key characteristic of this disorder is that as the patient’s depressed mood improves, their memory and cognition also improve.6Table 13,6 outlines overlapping features of MDD and pseudodementia.

Continue to: EVALUATION Worsening depression

EVALUATION Worsening depression

At her Psychiatry follow-up appointment, Ms. X reports that her mood is worse since she ended the relationship with her partner and she feels anxious because the partner was financially supporting her. Her PHQ-9 score is 24 (severe depression) and her GAD-7 score is 12 (moderate anxiety). Ms. X reports tolerating her transition from venlafaxine XR 225 mg/d to sertraline 50 mg/d well.

Additionally, Ms. X reports her children have called her “useless” since she continues to have difficulties following through on household tasks, even though she has no physical impairments that prevent her from completing them. The Psychiatry team observes that Ms. X has no problems walking or moving her arms or legs.

The Psychiatry team administers the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). Ms. X scores 22, indicating mild impairment.

The team recommends a neuropsychological assessment to determine if this MoCA score is due to a cognitive disorder or is rooted in her mood symptoms. The team also recommends an MRI of the brain, complete blood count (CBC), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), and urinalysis (UA).

[polldaddy:12189567]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Neuropsychological assessments are important tools for exploring the behavioral manifestations of brain dysfunction (Table 2).7 These assessments factor in elements of neurology, psychiatry, and psychology to provide information about the diagnosis, prognosis, and functional status of patients with medical conditions, especially those with neurocognitive and psychiatric disorders. They combine information from the patient and collateral interviews, behavioral observations, a review of patient records, and objective tests of motor, emotional, and cognitive function.

Among other uses, neuropsychological assessments can help identify depression in patients with neurologic impairment, determine the diagnosis and plan of care for patients with concussions, determine the risk of a motor vehicle crash in patients with cognitive impairment, and distinguish Alzheimer disease from vascular dementia.8 Components of such assessments include the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) to assess anxiety, the Dementia Rating Scale-2 and Neuropsychological Assessment Battery-Screening Module to assess dementia, and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) to assess depression.9

EVALUATION Continued cognitive decline

A different psychologist performs the neuropsychological assessment, who conducts the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status Update to determine if Ms. X is experiencing cognitive impairment. Her immediate memory, visuospatial/constructions, language, attention, and delayed memory are significantly impaired for someone her age. The psychologist also administers the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale IV and finds Ms. X’s general cognitive ability is within the low average range of intellectual functioning as measured by Full-Scale IQ. Ms. X scores 29 on the BDI-II, indicating significant depressive symptoms, and 13 on the BAI, indicating mild anxiety symptoms.

Ms. X is diagnosed with MDD and an unspecified neurocognitive disorder. The psychologist recommends she start CBT to address her mood and anxiety symptoms.

Upon reviewing the results with Ms. X, the treatment team again recommends a brain MRI, CBC, CMP, and UA to rule out organic causes of her cognitive decline. Ms. X decides against the MRI and laboratory workup and elects to continue her present medication regimen and CBT.

Several weeks later, Ms. X’s family brings her to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation of worsening mood, decreased personal hygiene, increased irritability, and further cognitive decline. They report she is having an increasingly difficult time remembering things such as where she parked her car. The ED team decides to discontinue clonazepam but continues sertraline and trazodone.

Continue to: CBC, CMP, and UA...

CBC, CMP, and UA are unremarkable. Ms. X undergoes a brain CT scan without contrast, which reveals hyperdense lesions in the inferior left tentorium, posterior fossa. A subsequent brain MRI with contrast reveals a dural-based enhancing mass, inferior to the left tentorium, in the left posterior fossa measuring 2.2 cm x 2.1 cm, suggestive of a meningioma. The team orders a Neurosurgery consult.

[polldaddy:12189571]

The authors’ observations

While most brain tumors are secondary to metastasis, meningiomas are the most common primary CNS tumor. Typically, they are asymptomatic; their diagnosis is often delayed until the patient presents with psychiatric symptoms without any focal neurologic findings. The frontal lobe is the most common location of meningioma. Data from 48 case reports of patients with meningiomas and psychiatric symptoms suggest symptoms do not always correlate with specific brain regions.10,11

Indications for neuroimaging in cases such as Ms. X include an abrupt change in behavior or personality, lack of response to psychiatric treatment, presence of focal neurologic signs, and an unusual psychiatric presentation and development of symptoms.11

TREATMENT Neurosurgery

Neurosurgery recommends and performs a suboccipital craniotomy for biopsy and resection. Ms. X tolerates the procedure well. A meningioma is found in the posterior fossa, near the cerebellar convexity. A biopsy finds no evidence of malignancies.

At her postoperative follow-up appointment several days after the procedure, Ms. X reports new-onset hearing loss and tinnitus.

[polldaddy:12189747]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Patients who require neurosurgery typically already carry a heavy psychiatric burden, which makes it challenging to determine the exact psychiatric consequences of neurosurgery.12-14 For example, research shows that temporal lobe resection and temporal lobectomy for treatment-resistant epilepsy can lead to an exacerbation of baseline psychiatric symptoms and the development of new symptoms (31% to 34%).15,16 However, Bommakanti et al13 found no new psychiatric symptoms after resection of meningiomas, and surgery seemed to play a role in ameliorating psychiatric symptoms in patients with intracranial tumors. Research attempting to document the psychiatric sequelae of neurosurgery has had mixed results, and it is difficult to determine what effects brain surgery has on mental health.

OUTCOME Minimal improvement

Several weeks after neurosurgery, Ms. X and her family report her mood is improved. Her PHQ-9 score improves to 15, but her GAD-7 score increases to 13, 1 point above her previous score.

The treatment team recommends Ms. X continue taking sertraline 50 mg/d and trazodone 50 mg/d at bedtime. Ms. X’s family reports her cognition and memory have not improved; her MoCA score increases by 1 point to 23. The treatment team discusses with Ms. X and her family the possibility that her cognitive problems maybe better explained as a neurocognitive disorder rather than as a result of the meningioma, since her MoCA score has not significantly improved. Ms. X and her family decide to seek a second opinion from a neurologist.

Bottom Line

Pseudodementia is a term used to describe older adults who present with cognitive issues in the context of depressive symptoms. Even in the absence of focal findings, neuroimaging should be considered as part of the workup in patients who continue to experience a progressive decline in mood and cognitive function.

Related Resources

- Moller MD, Parmenter BA, Lane DW. Neuropsychological testing: a useful but underutilized resource. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(11):40-46,51.

- Pollak J. Psychological/neuropsychological testing: when to refer for reexamination. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(9):18- 19,30-31,37. doi:10.12788/cp.0157

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Sertraline • Zoloft

Trazodone • Oleptro

Venlafaxine extended- release • Effexor XR

CASE Depressed and anxious

Five years ago, Ms. X, age 60, was diagnosed with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (MDD) with anxiety. This diagnosis was established by a previous psychiatrist. She presents to a clinic for a second opinion.

Since her diagnosis, Ms. X has experienced sad mood, anhedonia, difficulty falling asleep, increased appetite and weight, and decreased concentration and attention. Her anxiety stems from her inability to work, which causes her to worry about her children. In the clinic, the treatment team conducts the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 item scale (GAD-7) with Ms. X. She scores 16 on the PHQ-9, indicating moderately severe depression, and scores 12 on the GAD-7, indicating moderate anxiety.

Ms. X’s current medication regimen consists of venlafaxine extended-release (XR) 225 mg/d, trazodone 100 mg/d at bedtime, and clonazepam 1 mg twice daily. She reports no significant improvement of her symptoms from these medications. Additionally, Ms. X reports that in the past she had been prescribed fluoxetine, citalopram, and duloxetine, but she cannot recall the dosages.

Ms. X appears appropriately groomed, maintains appropriate eye contact, has clear speech, and does not show evidence of internal stimulation; however, she has difficulty following instructions. She makes negative comments about herself such as “I’m worthless” and “Nobody cares about me.” The treatment team decides to taper Ms. X off venlafaxine XR and initiates sertraline 50 mg/d, while continuing trazodone 50 mg/d at bedtime and clonazepam 1 mg twice daily. The team refers her for cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) to address her cognitive distortions, sad mood, and anxiety. Ms. X is asked to follow up with Psychiatry in 1 week.

EVALUATION Unusual behavior

At her CBT intake, Ms. X endorses depression and anxiety. Her PHQ-9 score at this visit is 19 (moderately severe depression) and GAD-7 score is 16 (severe anxiety). The psychologist notes that Ms. X is able to complete activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living without assistance. Ms. X denies any use of illicit substances or alcohol. No gross memory impairment is noted during this appointment, though Ms. X exhibits unusual behavior, including exiting and re-entering the clinic multiple times to repeatedly ask about follow-up appointments. The psychologist concludes that Ms. X’s presentation and behavior can be explained by MDD and pseudodementia.

[polldaddy:12189562]

The authors’ observations

Pseudodementia gained recognition in clinical research >100 years ago.1 Officially coined by Kiloh in 1961, the term was used broadly to categorize psychiatric cases that present like dementia but are the result of reversible causes. More recently, it has been used to describe older adults who present with cognitive deficits in the context of depressive symptoms.2 The goal of evaluation is to determine if the primary issue is a cognitive disorder or a depressive episode. DSM-5-TR does not classify pseudodementia as a distinct diagnosis, but instead categorizes its symptoms as components under other major diagnostic categories. Patients can present with MDD and associated cognitive symptoms, or with a cognitive disorder with depressive symptoms, which would be diagnosed as a cognitive disorder with a major depressive-like episode.3

Pseudodementia is rare. Brodaty et al4 found the prevalence of pseudodementia in primary care settings was 0.6%. Older adults (age >65) who live alone are at increased risk of developing pseudodementia, which can be worsened by poor social support and acute psychosocial and environmental changes.5 A key characteristic of this disorder is that as the patient’s depressed mood improves, their memory and cognition also improve.6Table 13,6 outlines overlapping features of MDD and pseudodementia.

Continue to: EVALUATION Worsening depression

EVALUATION Worsening depression

At her Psychiatry follow-up appointment, Ms. X reports that her mood is worse since she ended the relationship with her partner and she feels anxious because the partner was financially supporting her. Her PHQ-9 score is 24 (severe depression) and her GAD-7 score is 12 (moderate anxiety). Ms. X reports tolerating her transition from venlafaxine XR 225 mg/d to sertraline 50 mg/d well.

Additionally, Ms. X reports her children have called her “useless” since she continues to have difficulties following through on household tasks, even though she has no physical impairments that prevent her from completing them. The Psychiatry team observes that Ms. X has no problems walking or moving her arms or legs.

The Psychiatry team administers the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). Ms. X scores 22, indicating mild impairment.

The team recommends a neuropsychological assessment to determine if this MoCA score is due to a cognitive disorder or is rooted in her mood symptoms. The team also recommends an MRI of the brain, complete blood count (CBC), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), and urinalysis (UA).

[polldaddy:12189567]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Neuropsychological assessments are important tools for exploring the behavioral manifestations of brain dysfunction (Table 2).7 These assessments factor in elements of neurology, psychiatry, and psychology to provide information about the diagnosis, prognosis, and functional status of patients with medical conditions, especially those with neurocognitive and psychiatric disorders. They combine information from the patient and collateral interviews, behavioral observations, a review of patient records, and objective tests of motor, emotional, and cognitive function.

Among other uses, neuropsychological assessments can help identify depression in patients with neurologic impairment, determine the diagnosis and plan of care for patients with concussions, determine the risk of a motor vehicle crash in patients with cognitive impairment, and distinguish Alzheimer disease from vascular dementia.8 Components of such assessments include the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) to assess anxiety, the Dementia Rating Scale-2 and Neuropsychological Assessment Battery-Screening Module to assess dementia, and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) to assess depression.9

EVALUATION Continued cognitive decline

A different psychologist performs the neuropsychological assessment, who conducts the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status Update to determine if Ms. X is experiencing cognitive impairment. Her immediate memory, visuospatial/constructions, language, attention, and delayed memory are significantly impaired for someone her age. The psychologist also administers the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale IV and finds Ms. X’s general cognitive ability is within the low average range of intellectual functioning as measured by Full-Scale IQ. Ms. X scores 29 on the BDI-II, indicating significant depressive symptoms, and 13 on the BAI, indicating mild anxiety symptoms.

Ms. X is diagnosed with MDD and an unspecified neurocognitive disorder. The psychologist recommends she start CBT to address her mood and anxiety symptoms.

Upon reviewing the results with Ms. X, the treatment team again recommends a brain MRI, CBC, CMP, and UA to rule out organic causes of her cognitive decline. Ms. X decides against the MRI and laboratory workup and elects to continue her present medication regimen and CBT.

Several weeks later, Ms. X’s family brings her to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation of worsening mood, decreased personal hygiene, increased irritability, and further cognitive decline. They report she is having an increasingly difficult time remembering things such as where she parked her car. The ED team decides to discontinue clonazepam but continues sertraline and trazodone.

Continue to: CBC, CMP, and UA...

CBC, CMP, and UA are unremarkable. Ms. X undergoes a brain CT scan without contrast, which reveals hyperdense lesions in the inferior left tentorium, posterior fossa. A subsequent brain MRI with contrast reveals a dural-based enhancing mass, inferior to the left tentorium, in the left posterior fossa measuring 2.2 cm x 2.1 cm, suggestive of a meningioma. The team orders a Neurosurgery consult.

[polldaddy:12189571]

The authors’ observations

While most brain tumors are secondary to metastasis, meningiomas are the most common primary CNS tumor. Typically, they are asymptomatic; their diagnosis is often delayed until the patient presents with psychiatric symptoms without any focal neurologic findings. The frontal lobe is the most common location of meningioma. Data from 48 case reports of patients with meningiomas and psychiatric symptoms suggest symptoms do not always correlate with specific brain regions.10,11

Indications for neuroimaging in cases such as Ms. X include an abrupt change in behavior or personality, lack of response to psychiatric treatment, presence of focal neurologic signs, and an unusual psychiatric presentation and development of symptoms.11

TREATMENT Neurosurgery

Neurosurgery recommends and performs a suboccipital craniotomy for biopsy and resection. Ms. X tolerates the procedure well. A meningioma is found in the posterior fossa, near the cerebellar convexity. A biopsy finds no evidence of malignancies.

At her postoperative follow-up appointment several days after the procedure, Ms. X reports new-onset hearing loss and tinnitus.

[polldaddy:12189747]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Patients who require neurosurgery typically already carry a heavy psychiatric burden, which makes it challenging to determine the exact psychiatric consequences of neurosurgery.12-14 For example, research shows that temporal lobe resection and temporal lobectomy for treatment-resistant epilepsy can lead to an exacerbation of baseline psychiatric symptoms and the development of new symptoms (31% to 34%).15,16 However, Bommakanti et al13 found no new psychiatric symptoms after resection of meningiomas, and surgery seemed to play a role in ameliorating psychiatric symptoms in patients with intracranial tumors. Research attempting to document the psychiatric sequelae of neurosurgery has had mixed results, and it is difficult to determine what effects brain surgery has on mental health.

OUTCOME Minimal improvement

Several weeks after neurosurgery, Ms. X and her family report her mood is improved. Her PHQ-9 score improves to 15, but her GAD-7 score increases to 13, 1 point above her previous score.

The treatment team recommends Ms. X continue taking sertraline 50 mg/d and trazodone 50 mg/d at bedtime. Ms. X’s family reports her cognition and memory have not improved; her MoCA score increases by 1 point to 23. The treatment team discusses with Ms. X and her family the possibility that her cognitive problems maybe better explained as a neurocognitive disorder rather than as a result of the meningioma, since her MoCA score has not significantly improved. Ms. X and her family decide to seek a second opinion from a neurologist.

Bottom Line

Pseudodementia is a term used to describe older adults who present with cognitive issues in the context of depressive symptoms. Even in the absence of focal findings, neuroimaging should be considered as part of the workup in patients who continue to experience a progressive decline in mood and cognitive function.

Related Resources

- Moller MD, Parmenter BA, Lane DW. Neuropsychological testing: a useful but underutilized resource. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(11):40-46,51.

- Pollak J. Psychological/neuropsychological testing: when to refer for reexamination. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(9):18- 19,30-31,37. doi:10.12788/cp.0157

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Sertraline • Zoloft

Trazodone • Oleptro

Venlafaxine extended- release • Effexor XR

1. Nussbaum PD. (1994). Pseudodementia: a slow death. Neuropsychol Rev. 1994;4(2):71-90. doi:10.1007/BF01874829

2. Kang H, Zhao F, You L, et al. (2014). Pseudo-dementia: a neuropsychological review. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 17(2):147-154. doi:10.4103/0972-2327.132613

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, text revision. American Psychiatric Association; 2022.

4. Brodaty H, Connors MH. Pseudodementia, pseudo-pseudodementia, and pseudodepression. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2020;12(1):e12027. doi:10.1002/dad2.12027

5. Sekhon S, Marwaha R. Depressive Cognitive Disorders. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559256/

6. Brown WA. Pseudodementia: issues in diagnosis. Psychiatric Times. April 9, 2005. Accessed February 3, 2023. www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/pseudodementia-issues-diagnosis

7. Kulas JF, Naugle RI. (2003). Indications for neuropsychological assessment. Cleve Clin J Med. 2003;70(9):785-792.

8. Braun M, Tupper D, Kaufmann P, et al. Neuropsychological assessment: a valuable tool in the diagnosis and management of neurological, neurodevelopmental, medical, and psychiatric disorders. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2011;24(3):107-114.

9. Michels TC, Tiu AY, Graver CJ. Neuropsychological evaluation in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(5):495-502.

10. Wiemels J, Wrensch M, Claus EB. Epidemiology and etiology of meningioma. J Neurooncol. 2010;99(3):307-314. doi:10.1007/s11060-010-0386-3

11. Gyawali S, Sharma P, Mahapatra A. Meningioma and psychiatric symptoms: an individual patient data analysis. Asian J Psychiatr. 2019;42:94-103. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2019.03.029

12. McAllister TW. Neurobehavioral sequelae of traumatic brain injury: evaluation and management. World Psychiatry. 2008;7(1):3-10. doi:10.1002/j.2051-5545.2008.tb00139.x

13. Bommakanti K, Gaddamanugu P, Alladi S, et al. Pre-operative and post-operative psychiatric manifestations in patients with supratentorial meningiomas. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016;147:24-29. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2016.05.018

14. Devinsky O, Barr WB, Vickrey BG, et al. Changes in depression and anxiety after resective surgery for epilepsy. Neurology. 2005;65(11):1744-1749. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000187114.71524.c3

15. Blumer D, Wakhlu S, Davies K, et al. Psychiatric outcome of temporal lobectomy for epilepsy: incidence and treatment of psychiatric complications. Epilepsia. 1998;39(5):478-486. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01409.x

16. Glosser G, Zwil AS, Glosser DS, et al. Psychiatric aspects of temporal lobe epilepsy before and after anterior temporal lobectomy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68(1):53-58. doi:10.1136/jnnp.68.1.53

1. Nussbaum PD. (1994). Pseudodementia: a slow death. Neuropsychol Rev. 1994;4(2):71-90. doi:10.1007/BF01874829

2. Kang H, Zhao F, You L, et al. (2014). Pseudo-dementia: a neuropsychological review. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 17(2):147-154. doi:10.4103/0972-2327.132613

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, text revision. American Psychiatric Association; 2022.

4. Brodaty H, Connors MH. Pseudodementia, pseudo-pseudodementia, and pseudodepression. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2020;12(1):e12027. doi:10.1002/dad2.12027

5. Sekhon S, Marwaha R. Depressive Cognitive Disorders. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559256/

6. Brown WA. Pseudodementia: issues in diagnosis. Psychiatric Times. April 9, 2005. Accessed February 3, 2023. www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/pseudodementia-issues-diagnosis

7. Kulas JF, Naugle RI. (2003). Indications for neuropsychological assessment. Cleve Clin J Med. 2003;70(9):785-792.

8. Braun M, Tupper D, Kaufmann P, et al. Neuropsychological assessment: a valuable tool in the diagnosis and management of neurological, neurodevelopmental, medical, and psychiatric disorders. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2011;24(3):107-114.

9. Michels TC, Tiu AY, Graver CJ. Neuropsychological evaluation in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(5):495-502.

10. Wiemels J, Wrensch M, Claus EB. Epidemiology and etiology of meningioma. J Neurooncol. 2010;99(3):307-314. doi:10.1007/s11060-010-0386-3

11. Gyawali S, Sharma P, Mahapatra A. Meningioma and psychiatric symptoms: an individual patient data analysis. Asian J Psychiatr. 2019;42:94-103. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2019.03.029

12. McAllister TW. Neurobehavioral sequelae of traumatic brain injury: evaluation and management. World Psychiatry. 2008;7(1):3-10. doi:10.1002/j.2051-5545.2008.tb00139.x

13. Bommakanti K, Gaddamanugu P, Alladi S, et al. Pre-operative and post-operative psychiatric manifestations in patients with supratentorial meningiomas. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016;147:24-29. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2016.05.018

14. Devinsky O, Barr WB, Vickrey BG, et al. Changes in depression and anxiety after resective surgery for epilepsy. Neurology. 2005;65(11):1744-1749. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000187114.71524.c3

15. Blumer D, Wakhlu S, Davies K, et al. Psychiatric outcome of temporal lobectomy for epilepsy: incidence and treatment of psychiatric complications. Epilepsia. 1998;39(5):478-486. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01409.x

16. Glosser G, Zwil AS, Glosser DS, et al. Psychiatric aspects of temporal lobe epilepsy before and after anterior temporal lobectomy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68(1):53-58. doi:10.1136/jnnp.68.1.53