User login

Returning to work after a patient assault

Mr. B, age 23, is admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit for depression. During his hospitalization, Mr. B becomes fixated on obtaining specific medications, including controlled substances. He is treated by Dr. M, a psychiatrist early in her training. In a difficult conversation, Dr. M tells Mr. B he will not be prescribed the medications he is requesting and explains why. Mr. B responds by jumping across a table and repeatedly punching Dr. M. Unit staff restrains Mr. B, and Dr. M leaves to seek medical care.

Assaults perpetrated against employees on inpatient psychiatric units are common.1 Assaults on physicians can occur at any level of training, including during residency.2 This is not a new phenomenon: concerns about patients assaulting psychiatrists and other inpatient staff have been reported for decades.3-5 Most research surrounding this topic has focused on risk factors for violence and prevention.6 Research regarding the aftermath of a patient assault and what services an employee requires have primarily centered on nurses.7,8

Practical guidance for a psychiatrist who has been assaulted and wants to return to work is difficult to find. This article provides strategies to help psychiatrists (and their colleagues) transition back to work after being the victim of a patient assault. While the recommendations we provide can be applied to trainees as well as attending physicians, there are some considerations specific to residents who have been assaulted (Box9,10).

Box

Psychiatry residents who are the targets of violence (such as Dr. M) require unique management, including evaluation of how the assault impacts their training and the role of the program director. Additionally, according to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Common Program Requirements, residency programs must address residents’ wellbeing, including “evaluating workplace safety data and addressing the safety of residents and faculty members.”9 These specific considerations for residents are guided by the most recent program requirements through ACGME, as well as the policies of the specific institution overseeing the residency. Some institutions have developed resources to assist in this area, such as the WELL Toolkit from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.10

Having a plan for after an assault

The aftereffects of a patient assault can take a significant toll on the individual who is assaulted. A 2021 article about psychiatric mental health nurses by Dean et al8 identified multiple potential repercussions of unaddressed workplace violence, including role confusion, job dissatisfaction, decreased resiliency traits, poor coping methods, increased attrition rate, and increased expenditures related to assault injuries. Providing appropriate services and having a plan for how best to support an assaulted psychiatrist are likely to mitigate these effects. This can be grouped into 4 categories: 1) seeking immediate care, 2) removing the patient from your care, 3) easing back into the environment, and 4) finding long-term support.

1. Seeking immediate care

“Round or be rounded on” is a phrase that encapsulates many physicians’ attitude regarding their own health care and may contribute to their refusal of medical care following acute trauma such as an assault. Feelings of shock, guilt, and shame may also lead to a psychiatrist’s initial hesitation to seek treatment. However, it is important for the victim of an assault to be promptly evaluated and treated.

Elevated adrenaline in the aftermath of a physical engagement may mask the perception of injuries, and there is a risk for exposure to blood-borne pathogens. Regardless of the severity of injuries, seeking medical care establishes documentation of any injuries that can later serve as a record for workers’ compensation claims or if legal action is taken.

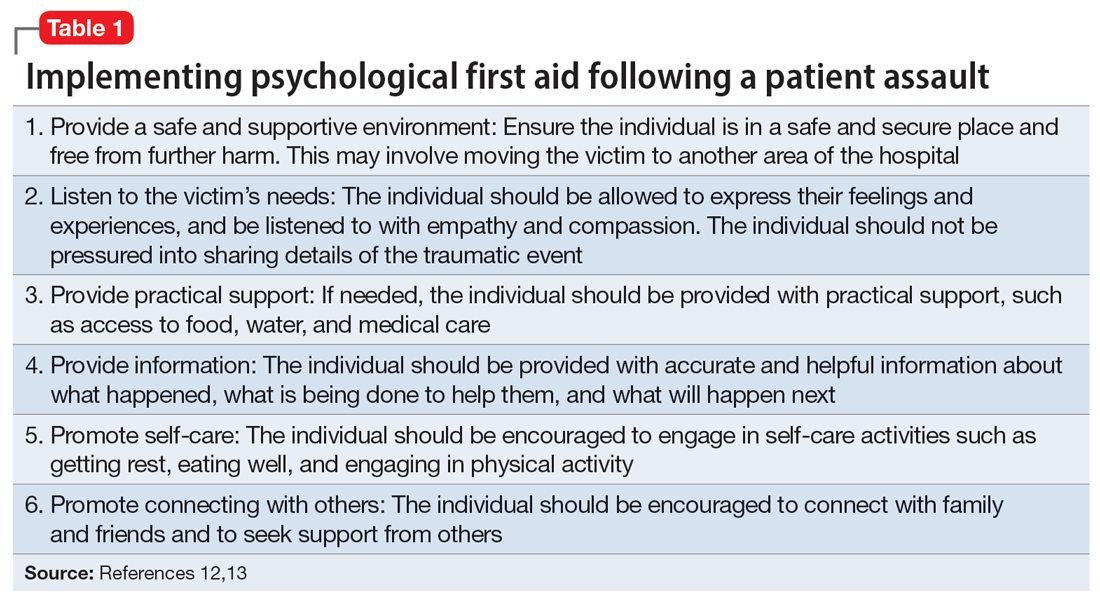

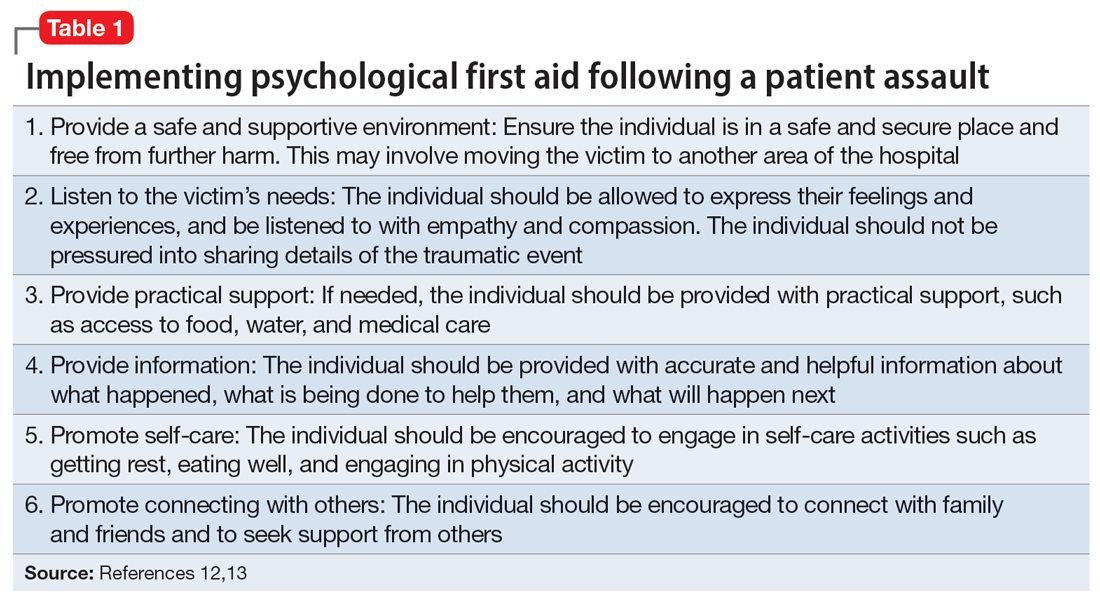

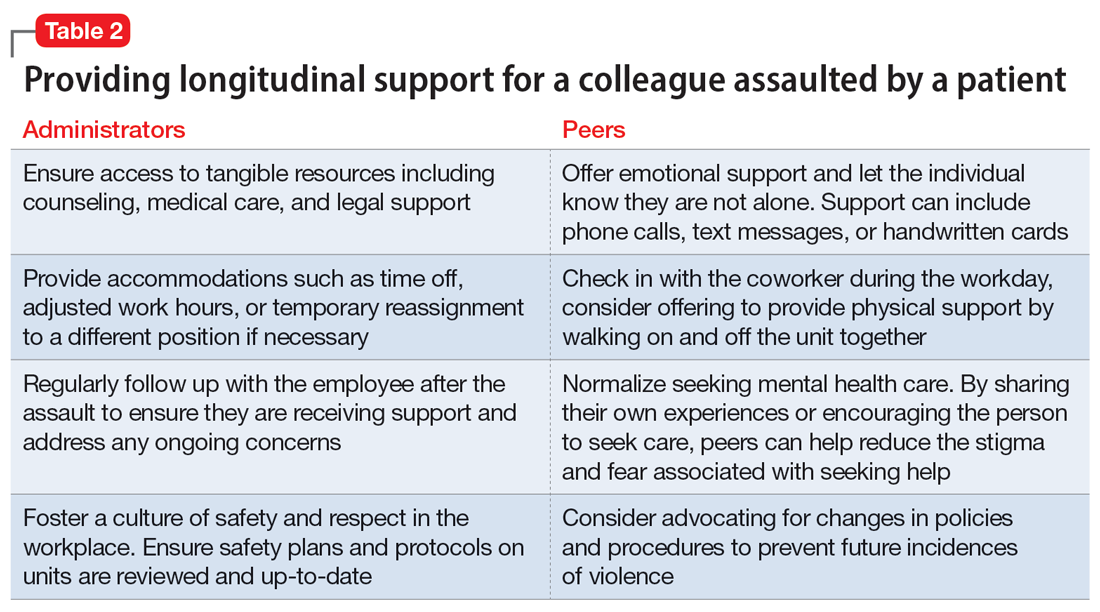

In addition to medical needs, immediate psychological support should be considered. Compulsory participation in crisis intervention stress debriefing, particularly when performed by untrained individuals, is not recommended due to questions about its demonstrated efficacy and potential to increase the risk of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the long term.11,12 However, research has established the need for immediate support that does not necessarily involve a discussion of the traumatic event. One option is psychological first aid (PFA), an intervention supported by the World Health Organization. Originally developed for victims of mass crisis events, PFA easily translates to the hospital setting.12,13 PFA focuses on the immediate, basic needs of the victim to reduce distress and anxiety and encourage adaptive coping. Table 112,13 summarizes key components of PFA.

Continue to: PFA can be compared...

PFA can be compared to medical first aid in the field prior to reaching the hospital. In the case of Dr. M, other residents collaborated to transport her to the hospital, keep attendings and program directors apprised of the situation, and bring her snacks and comfort items to the hospital. Dr. M also received support from attending physicians at a neighboring hospital who helped coordinate her care. Essentially, she received a de facto version of PFA. However, given the evidence behind PFA and the unfortunate rate of violence against health care staff, institutions and organizations may offer training in PFA to ensure this level of support for all victims.

Multiple groups may take the lead to support a physician following an injury, including human resources, employee health, or other offices within the institution. The principles of PFA can be used to guide these employees in assisting the victim. Even if such employees are not trained in PFA, they can align with these principles by ensuring access to counseling and medical care, assisting with time off and accommodations, and helping the victim of an assault navigate the legal and administrative processes. Workers’ compensation can be a challenging process, and an institution’s human resources department should be available to assist the assaulted individual in navigating resources both within and outside of what they are able to offer.

2. Removing the patient from the psychiatrist’s care

During her recovery, Dr. M heard from a few peers that what happened was an occupational hazard. On some level, they were correct. While the public does not perceive a career in medicine to be physically dangerous, violence is a rampant problem in health care. Research shows that health care professionals are up to 16 times more likely to experience violence than other occupations; the odds for nurses are even higher.8

The frequency and pervasiveness of violence against health care professionals create an environment in which it can become an expected, and even accepted, phenomenon. However, violence cannot and should not be viewed as a normal part of workplace culture. A 2016 study by Moylan et al7 found that many nurses believe violence is part of their role, and therefore do not recognize the need to report such incidents or seek the necessary support. In other studies, only 30% of nurses reported violence, and the rate of reporting by physicians was 26%.14 This underreporting likely represents the role confusion surrounding whether caring for self or caring for the patient takes precedent, as well as normative expectations surrounding violence in the workplace.

It must be made clear to the victim that their safety is a priority and violence will not be tolerated. An institution’s administration can achieve this by immediately removing the patient from the victim’s care. In many cases, discharge of the patient from the clinic or facility may be warranted. A psychiatrist should not be expected to continue as the primary physician for a patient who has assaulted them; transfer to another psychiatrist is necessary if discharge is not an appropriate option. In a scenario in which a psychiatrist must maintain the treating relationship with a patient who assaulted them until the patient can be placed with another clinician (eg, as might occur on a unit with severely limited resources), staff chaperones can be considered when interacting with the patient.

Continue to: An institution's adminstration...

An institution’s administration should provide support if the psychiatrist chooses to press charges. At the core of our ethos as physicians is “do no harm,” and for some, the prospect of filing charges may be a difficult decision. However, health care professionals do not have an ethical obligation to put themselves in danger of serious bodily harm.15 While there is no one-size-fits-all answer to the question of whether or not to press charges against a patient who has committed an assault, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration considers the perception that violence is tolerated and victims are unable to report to law enforcement an organizational risk factor for workplace violence.16

As leaders in the workplace, physicians should set the precedent that violence will not be tolerated by reporting incidents to police and filing charges when appropriate. In the case of Dr. M, she received full support from her institution’s administration in filing charges against Mr. B due to the specific details of the assault.

3. Easing back into the environment

Despite assurances from her superiors that she could take time off, Dr. M wanted to return to work as soon as possible. She considered the balance between her physical injuries and desire to return to work and ultimately returned to work 5 days after the assault. She did well with supportive measures from administration and other staff, including the use of technician escorts on the unit, peer support, and frequent communication with and check-ins from management.

The decision on how quickly to return to work should always lie with the individual who was assaulted. The administration should offer time off without hesitation. Victims of an assault may feel overwhelmed by 2 diverging paths on how to return to a traumatic environment: avoid the location at all costs, or try to “face their fears” and return as quickly as possible. Research from outside medicine indicates that the timing of returning to work after a traumatic injury may not be nearly as important as the method of returning, and who makes this decision.17 Predictors of return to work after an assault include not only the severity of the trauma and amount of distress symptoms, but also any actual or perceived injustice on the part of the victim.17 Although this study was not specific to health care employees, it suggests that overall, an employee who does not feel a sense of control over their choice to return to work could perceive that as an injustice on the part of administration, leading to decreased job satisfaction.17

A study by Lamothe et al18 that was specific to health care professionals found that despite the importance of self-efficacy for the assault victim, perceived organizational support had an even greater protective effect following patient violence.Additionally, monitoring for signs of distress among victims after an episode of violence could prevent further violence by reducing the risk for subsequent victimization.18 This highlights the need for leadership of an inpatient unit to be keenly aware of how an assault on a psychiatrist or other health care professional may change the work environment and create a need to help staff navigate the new normal they may face on the unit.

Continue to: Finding long-term support

4. Finding long-term support

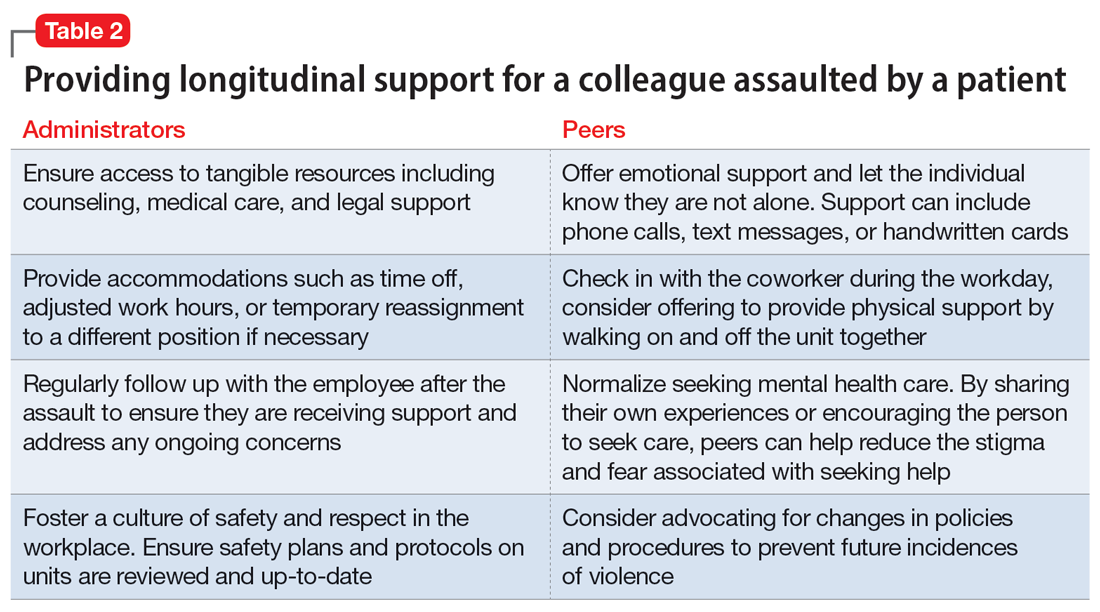

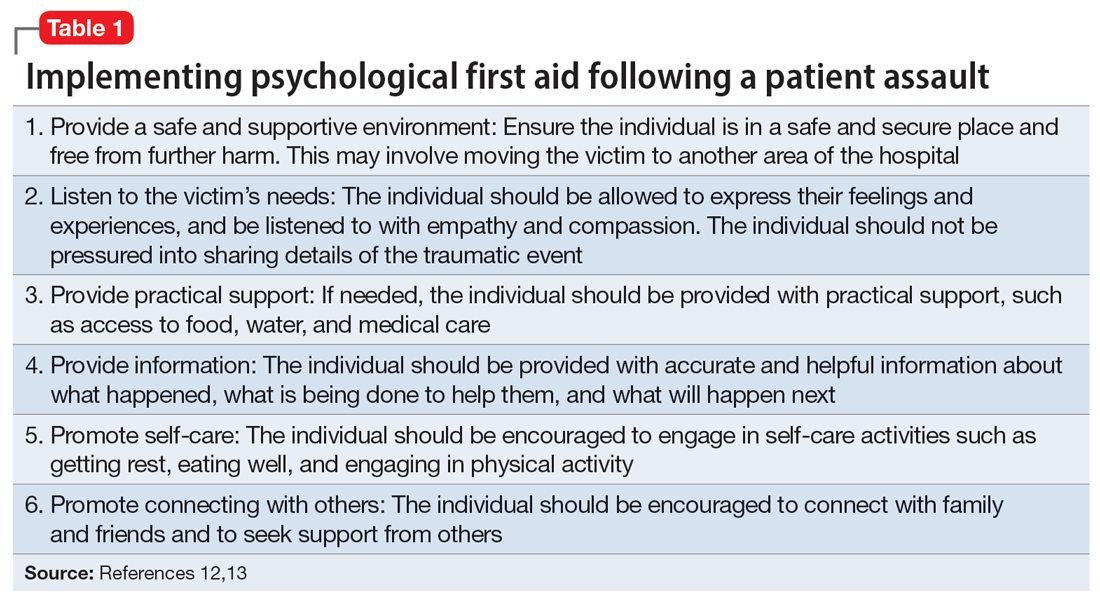

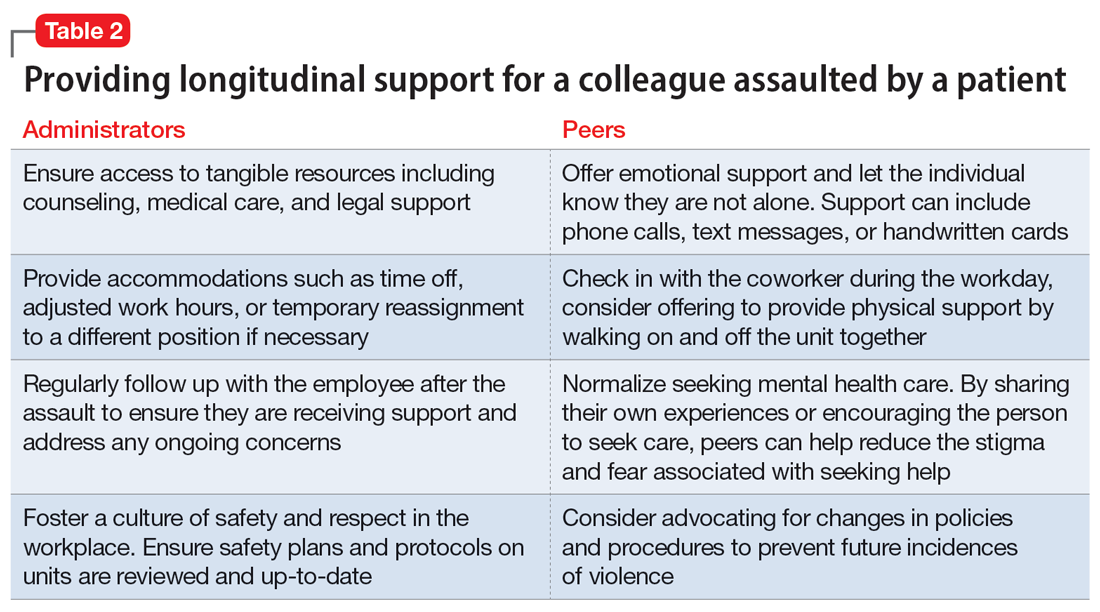

Longitudinal support is key in the initial transition back to work, as well as in the following weeks and months. Studies assessing the impacts of patient assault on mental health nurses indicate that while most individuals exposed to a traumatic event do not develop PTSD, many reported continued somatic symptoms, and more still reported ongoing psychological effects such as recurring thoughts of the assault, fear, generalized anger, and feeling a loss of control.8 Peer support is a common method employed by physicians and nurses alike, but administrative support is also essential.8

Regardless which form of psychotherapy, medication treatment, or peer support is utilized, access to the tools the psychiatrist finds most helpful is crucial to making them feel safe and comfortable returning to their role. Table 2 details practical steps administrators and peers can take to facilitate longitudinal support in these situations. In the case of Dr. M, administration was not only supportive in encouraging time off, but also in allowing protected time for therapy when she endorsed distress over the event. The combination of immediate responses and more long-term support greatly helped Dr. M continue her role as a psychiatrist and remain satisfied with her work.

Bottom Line

Being assaulted by a patient can make a psychiatrist reluctant to return to work. Strategies to ease this transition include seeking immediate care, removing the patient from the care of the psychiatrist who was assaulted, easing back into the environment, and finding long-term support.

Related Resources

- Lapic S, Joshi KG. What to do after a patient assaults you. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(10):53-54.

- Joshi KG. Workplace violence: enhance your safety in outpatient settings. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(8):37-38. doi:10.12788/cp.0163

- Su D. Harassment of health care workers: a survey. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(6):48-50. doi:10.12788/cp.0135

- Rozel JS, Wiles C, Amin P. Too close for comfort: when the psychiatrist is stalked. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(1): 23-28. doi:10.12788/cp.0209

1. Odes R, Chapman S, Harrison R, et al. Frequency of violence towards healthcare workers in the United States’ inpatient psychiatric hospitals: a systematic review of literature. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2021;30(1):27-46.

2. Chaimowitz GA, Moscovitch A. Patient assaults on psychiatric residents: the Canadian experience. Can J Psychiatry. 1991;36(2):107-111.

3. Faulkner LR, Grimm NR, MacFarland BH, et al. Threats and assaults against psychiatrists. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1990;18(1):37-46.

4. Carmel H, Hunter M. Psychiatrists injured by patient attack. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1991;19(3):309-316.

5. Kwok S, Ostermeyer B, Coverdale J. A systematic review of the prevalence of patient assaults against residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(3):296-300.

6. Weltens I, Bak M, Verhagen S, et al. Aggression on the psychiatric ward: prevalence and risk factors. A systematic review of the literature. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0258346.

7. Moylan L, McManus M, Cullinan M, et al. Need for specialized support services for nurse victims of physical assault by psychiatric patients. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2016;37(7):446-450.

8. Dean L, Butler A, Cuddigan J. The impact of workplace violence toward psychiatric mental health nurses: identifying the facilitators and barriers to supportive resources. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2021;27(3):189-202.

9. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common program requirements (Residency). July 2023. Accessed September 20, 2023. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/cprresidency_2023v3.pdf

10. WELL Toolkit. UPMC GME Well-Being. October 3, 2022. Accessed September 20, 2023. https://gmewellness.upmc.com/

11. Rose S, Bisson J, Churchill R, et al. Psychological debriefing for preventing post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD000560.

12. Flannery RB Jr, Farley E, Rego S, et al. Characteristics of staff victims of psychiatric patient assaults: 15-year analysis of the Assaulted Staff Action Program (ASAP). Psychiatr Q. 2007;78(1):25-37.

13. Gispen F, Wu AW. Psychological first aid: CPR for mental health crises in healthcare. J Patient Saf Risk Manag. 2018:23(2):51-53.

14. Phillips JP. Workplace violence against health care workers in the United States. N Eng J Med. 2016;374(17):1661-1669.

15. Baby M, Glue P, Carlyle D. ‘Violence is not part of our job’: a thematic analysis of psychiatric mental health nurses’ experiences of patient assaults from a New Zealand perspective. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2014;35(9):647-655.

16. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Guidelines for Preventing Workplace Violence for Healthcare and Social Service Workers. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, US Dept of Labor; 2015.

17. Giummarra, MJ, Cameron PA, Ponsford J, et al. Return to work after traumatic injury: increased work-related disability in injured persons receiving financial compensation is mediated by perceived injustice. J Occup Rehabil. 2017;27(2):173-185.

18. Lamothe J, Boyer R, Guay S. A longitudinal analysis of psychological distress among healthcare workers following patient violence. Can J Behav Sci. 2021;53(1):48-58.

Mr. B, age 23, is admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit for depression. During his hospitalization, Mr. B becomes fixated on obtaining specific medications, including controlled substances. He is treated by Dr. M, a psychiatrist early in her training. In a difficult conversation, Dr. M tells Mr. B he will not be prescribed the medications he is requesting and explains why. Mr. B responds by jumping across a table and repeatedly punching Dr. M. Unit staff restrains Mr. B, and Dr. M leaves to seek medical care.

Assaults perpetrated against employees on inpatient psychiatric units are common.1 Assaults on physicians can occur at any level of training, including during residency.2 This is not a new phenomenon: concerns about patients assaulting psychiatrists and other inpatient staff have been reported for decades.3-5 Most research surrounding this topic has focused on risk factors for violence and prevention.6 Research regarding the aftermath of a patient assault and what services an employee requires have primarily centered on nurses.7,8

Practical guidance for a psychiatrist who has been assaulted and wants to return to work is difficult to find. This article provides strategies to help psychiatrists (and their colleagues) transition back to work after being the victim of a patient assault. While the recommendations we provide can be applied to trainees as well as attending physicians, there are some considerations specific to residents who have been assaulted (Box9,10).

Box

Psychiatry residents who are the targets of violence (such as Dr. M) require unique management, including evaluation of how the assault impacts their training and the role of the program director. Additionally, according to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Common Program Requirements, residency programs must address residents’ wellbeing, including “evaluating workplace safety data and addressing the safety of residents and faculty members.”9 These specific considerations for residents are guided by the most recent program requirements through ACGME, as well as the policies of the specific institution overseeing the residency. Some institutions have developed resources to assist in this area, such as the WELL Toolkit from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.10

Having a plan for after an assault

The aftereffects of a patient assault can take a significant toll on the individual who is assaulted. A 2021 article about psychiatric mental health nurses by Dean et al8 identified multiple potential repercussions of unaddressed workplace violence, including role confusion, job dissatisfaction, decreased resiliency traits, poor coping methods, increased attrition rate, and increased expenditures related to assault injuries. Providing appropriate services and having a plan for how best to support an assaulted psychiatrist are likely to mitigate these effects. This can be grouped into 4 categories: 1) seeking immediate care, 2) removing the patient from your care, 3) easing back into the environment, and 4) finding long-term support.

1. Seeking immediate care

“Round or be rounded on” is a phrase that encapsulates many physicians’ attitude regarding their own health care and may contribute to their refusal of medical care following acute trauma such as an assault. Feelings of shock, guilt, and shame may also lead to a psychiatrist’s initial hesitation to seek treatment. However, it is important for the victim of an assault to be promptly evaluated and treated.

Elevated adrenaline in the aftermath of a physical engagement may mask the perception of injuries, and there is a risk for exposure to blood-borne pathogens. Regardless of the severity of injuries, seeking medical care establishes documentation of any injuries that can later serve as a record for workers’ compensation claims or if legal action is taken.

In addition to medical needs, immediate psychological support should be considered. Compulsory participation in crisis intervention stress debriefing, particularly when performed by untrained individuals, is not recommended due to questions about its demonstrated efficacy and potential to increase the risk of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the long term.11,12 However, research has established the need for immediate support that does not necessarily involve a discussion of the traumatic event. One option is psychological first aid (PFA), an intervention supported by the World Health Organization. Originally developed for victims of mass crisis events, PFA easily translates to the hospital setting.12,13 PFA focuses on the immediate, basic needs of the victim to reduce distress and anxiety and encourage adaptive coping. Table 112,13 summarizes key components of PFA.

Continue to: PFA can be compared...

PFA can be compared to medical first aid in the field prior to reaching the hospital. In the case of Dr. M, other residents collaborated to transport her to the hospital, keep attendings and program directors apprised of the situation, and bring her snacks and comfort items to the hospital. Dr. M also received support from attending physicians at a neighboring hospital who helped coordinate her care. Essentially, she received a de facto version of PFA. However, given the evidence behind PFA and the unfortunate rate of violence against health care staff, institutions and organizations may offer training in PFA to ensure this level of support for all victims.

Multiple groups may take the lead to support a physician following an injury, including human resources, employee health, or other offices within the institution. The principles of PFA can be used to guide these employees in assisting the victim. Even if such employees are not trained in PFA, they can align with these principles by ensuring access to counseling and medical care, assisting with time off and accommodations, and helping the victim of an assault navigate the legal and administrative processes. Workers’ compensation can be a challenging process, and an institution’s human resources department should be available to assist the assaulted individual in navigating resources both within and outside of what they are able to offer.

2. Removing the patient from the psychiatrist’s care

During her recovery, Dr. M heard from a few peers that what happened was an occupational hazard. On some level, they were correct. While the public does not perceive a career in medicine to be physically dangerous, violence is a rampant problem in health care. Research shows that health care professionals are up to 16 times more likely to experience violence than other occupations; the odds for nurses are even higher.8

The frequency and pervasiveness of violence against health care professionals create an environment in which it can become an expected, and even accepted, phenomenon. However, violence cannot and should not be viewed as a normal part of workplace culture. A 2016 study by Moylan et al7 found that many nurses believe violence is part of their role, and therefore do not recognize the need to report such incidents or seek the necessary support. In other studies, only 30% of nurses reported violence, and the rate of reporting by physicians was 26%.14 This underreporting likely represents the role confusion surrounding whether caring for self or caring for the patient takes precedent, as well as normative expectations surrounding violence in the workplace.

It must be made clear to the victim that their safety is a priority and violence will not be tolerated. An institution’s administration can achieve this by immediately removing the patient from the victim’s care. In many cases, discharge of the patient from the clinic or facility may be warranted. A psychiatrist should not be expected to continue as the primary physician for a patient who has assaulted them; transfer to another psychiatrist is necessary if discharge is not an appropriate option. In a scenario in which a psychiatrist must maintain the treating relationship with a patient who assaulted them until the patient can be placed with another clinician (eg, as might occur on a unit with severely limited resources), staff chaperones can be considered when interacting with the patient.

Continue to: An institution's adminstration...

An institution’s administration should provide support if the psychiatrist chooses to press charges. At the core of our ethos as physicians is “do no harm,” and for some, the prospect of filing charges may be a difficult decision. However, health care professionals do not have an ethical obligation to put themselves in danger of serious bodily harm.15 While there is no one-size-fits-all answer to the question of whether or not to press charges against a patient who has committed an assault, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration considers the perception that violence is tolerated and victims are unable to report to law enforcement an organizational risk factor for workplace violence.16

As leaders in the workplace, physicians should set the precedent that violence will not be tolerated by reporting incidents to police and filing charges when appropriate. In the case of Dr. M, she received full support from her institution’s administration in filing charges against Mr. B due to the specific details of the assault.

3. Easing back into the environment

Despite assurances from her superiors that she could take time off, Dr. M wanted to return to work as soon as possible. She considered the balance between her physical injuries and desire to return to work and ultimately returned to work 5 days after the assault. She did well with supportive measures from administration and other staff, including the use of technician escorts on the unit, peer support, and frequent communication with and check-ins from management.

The decision on how quickly to return to work should always lie with the individual who was assaulted. The administration should offer time off without hesitation. Victims of an assault may feel overwhelmed by 2 diverging paths on how to return to a traumatic environment: avoid the location at all costs, or try to “face their fears” and return as quickly as possible. Research from outside medicine indicates that the timing of returning to work after a traumatic injury may not be nearly as important as the method of returning, and who makes this decision.17 Predictors of return to work after an assault include not only the severity of the trauma and amount of distress symptoms, but also any actual or perceived injustice on the part of the victim.17 Although this study was not specific to health care employees, it suggests that overall, an employee who does not feel a sense of control over their choice to return to work could perceive that as an injustice on the part of administration, leading to decreased job satisfaction.17

A study by Lamothe et al18 that was specific to health care professionals found that despite the importance of self-efficacy for the assault victim, perceived organizational support had an even greater protective effect following patient violence.Additionally, monitoring for signs of distress among victims after an episode of violence could prevent further violence by reducing the risk for subsequent victimization.18 This highlights the need for leadership of an inpatient unit to be keenly aware of how an assault on a psychiatrist or other health care professional may change the work environment and create a need to help staff navigate the new normal they may face on the unit.

Continue to: Finding long-term support

4. Finding long-term support

Longitudinal support is key in the initial transition back to work, as well as in the following weeks and months. Studies assessing the impacts of patient assault on mental health nurses indicate that while most individuals exposed to a traumatic event do not develop PTSD, many reported continued somatic symptoms, and more still reported ongoing psychological effects such as recurring thoughts of the assault, fear, generalized anger, and feeling a loss of control.8 Peer support is a common method employed by physicians and nurses alike, but administrative support is also essential.8

Regardless which form of psychotherapy, medication treatment, or peer support is utilized, access to the tools the psychiatrist finds most helpful is crucial to making them feel safe and comfortable returning to their role. Table 2 details practical steps administrators and peers can take to facilitate longitudinal support in these situations. In the case of Dr. M, administration was not only supportive in encouraging time off, but also in allowing protected time for therapy when she endorsed distress over the event. The combination of immediate responses and more long-term support greatly helped Dr. M continue her role as a psychiatrist and remain satisfied with her work.

Bottom Line

Being assaulted by a patient can make a psychiatrist reluctant to return to work. Strategies to ease this transition include seeking immediate care, removing the patient from the care of the psychiatrist who was assaulted, easing back into the environment, and finding long-term support.

Related Resources

- Lapic S, Joshi KG. What to do after a patient assaults you. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(10):53-54.

- Joshi KG. Workplace violence: enhance your safety in outpatient settings. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(8):37-38. doi:10.12788/cp.0163

- Su D. Harassment of health care workers: a survey. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(6):48-50. doi:10.12788/cp.0135

- Rozel JS, Wiles C, Amin P. Too close for comfort: when the psychiatrist is stalked. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(1): 23-28. doi:10.12788/cp.0209

Mr. B, age 23, is admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit for depression. During his hospitalization, Mr. B becomes fixated on obtaining specific medications, including controlled substances. He is treated by Dr. M, a psychiatrist early in her training. In a difficult conversation, Dr. M tells Mr. B he will not be prescribed the medications he is requesting and explains why. Mr. B responds by jumping across a table and repeatedly punching Dr. M. Unit staff restrains Mr. B, and Dr. M leaves to seek medical care.

Assaults perpetrated against employees on inpatient psychiatric units are common.1 Assaults on physicians can occur at any level of training, including during residency.2 This is not a new phenomenon: concerns about patients assaulting psychiatrists and other inpatient staff have been reported for decades.3-5 Most research surrounding this topic has focused on risk factors for violence and prevention.6 Research regarding the aftermath of a patient assault and what services an employee requires have primarily centered on nurses.7,8

Practical guidance for a psychiatrist who has been assaulted and wants to return to work is difficult to find. This article provides strategies to help psychiatrists (and their colleagues) transition back to work after being the victim of a patient assault. While the recommendations we provide can be applied to trainees as well as attending physicians, there are some considerations specific to residents who have been assaulted (Box9,10).

Box

Psychiatry residents who are the targets of violence (such as Dr. M) require unique management, including evaluation of how the assault impacts their training and the role of the program director. Additionally, according to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Common Program Requirements, residency programs must address residents’ wellbeing, including “evaluating workplace safety data and addressing the safety of residents and faculty members.”9 These specific considerations for residents are guided by the most recent program requirements through ACGME, as well as the policies of the specific institution overseeing the residency. Some institutions have developed resources to assist in this area, such as the WELL Toolkit from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.10

Having a plan for after an assault

The aftereffects of a patient assault can take a significant toll on the individual who is assaulted. A 2021 article about psychiatric mental health nurses by Dean et al8 identified multiple potential repercussions of unaddressed workplace violence, including role confusion, job dissatisfaction, decreased resiliency traits, poor coping methods, increased attrition rate, and increased expenditures related to assault injuries. Providing appropriate services and having a plan for how best to support an assaulted psychiatrist are likely to mitigate these effects. This can be grouped into 4 categories: 1) seeking immediate care, 2) removing the patient from your care, 3) easing back into the environment, and 4) finding long-term support.

1. Seeking immediate care

“Round or be rounded on” is a phrase that encapsulates many physicians’ attitude regarding their own health care and may contribute to their refusal of medical care following acute trauma such as an assault. Feelings of shock, guilt, and shame may also lead to a psychiatrist’s initial hesitation to seek treatment. However, it is important for the victim of an assault to be promptly evaluated and treated.

Elevated adrenaline in the aftermath of a physical engagement may mask the perception of injuries, and there is a risk for exposure to blood-borne pathogens. Regardless of the severity of injuries, seeking medical care establishes documentation of any injuries that can later serve as a record for workers’ compensation claims or if legal action is taken.

In addition to medical needs, immediate psychological support should be considered. Compulsory participation in crisis intervention stress debriefing, particularly when performed by untrained individuals, is not recommended due to questions about its demonstrated efficacy and potential to increase the risk of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the long term.11,12 However, research has established the need for immediate support that does not necessarily involve a discussion of the traumatic event. One option is psychological first aid (PFA), an intervention supported by the World Health Organization. Originally developed for victims of mass crisis events, PFA easily translates to the hospital setting.12,13 PFA focuses on the immediate, basic needs of the victim to reduce distress and anxiety and encourage adaptive coping. Table 112,13 summarizes key components of PFA.

Continue to: PFA can be compared...

PFA can be compared to medical first aid in the field prior to reaching the hospital. In the case of Dr. M, other residents collaborated to transport her to the hospital, keep attendings and program directors apprised of the situation, and bring her snacks and comfort items to the hospital. Dr. M also received support from attending physicians at a neighboring hospital who helped coordinate her care. Essentially, she received a de facto version of PFA. However, given the evidence behind PFA and the unfortunate rate of violence against health care staff, institutions and organizations may offer training in PFA to ensure this level of support for all victims.

Multiple groups may take the lead to support a physician following an injury, including human resources, employee health, or other offices within the institution. The principles of PFA can be used to guide these employees in assisting the victim. Even if such employees are not trained in PFA, they can align with these principles by ensuring access to counseling and medical care, assisting with time off and accommodations, and helping the victim of an assault navigate the legal and administrative processes. Workers’ compensation can be a challenging process, and an institution’s human resources department should be available to assist the assaulted individual in navigating resources both within and outside of what they are able to offer.

2. Removing the patient from the psychiatrist’s care

During her recovery, Dr. M heard from a few peers that what happened was an occupational hazard. On some level, they were correct. While the public does not perceive a career in medicine to be physically dangerous, violence is a rampant problem in health care. Research shows that health care professionals are up to 16 times more likely to experience violence than other occupations; the odds for nurses are even higher.8

The frequency and pervasiveness of violence against health care professionals create an environment in which it can become an expected, and even accepted, phenomenon. However, violence cannot and should not be viewed as a normal part of workplace culture. A 2016 study by Moylan et al7 found that many nurses believe violence is part of their role, and therefore do not recognize the need to report such incidents or seek the necessary support. In other studies, only 30% of nurses reported violence, and the rate of reporting by physicians was 26%.14 This underreporting likely represents the role confusion surrounding whether caring for self or caring for the patient takes precedent, as well as normative expectations surrounding violence in the workplace.

It must be made clear to the victim that their safety is a priority and violence will not be tolerated. An institution’s administration can achieve this by immediately removing the patient from the victim’s care. In many cases, discharge of the patient from the clinic or facility may be warranted. A psychiatrist should not be expected to continue as the primary physician for a patient who has assaulted them; transfer to another psychiatrist is necessary if discharge is not an appropriate option. In a scenario in which a psychiatrist must maintain the treating relationship with a patient who assaulted them until the patient can be placed with another clinician (eg, as might occur on a unit with severely limited resources), staff chaperones can be considered when interacting with the patient.

Continue to: An institution's adminstration...

An institution’s administration should provide support if the psychiatrist chooses to press charges. At the core of our ethos as physicians is “do no harm,” and for some, the prospect of filing charges may be a difficult decision. However, health care professionals do not have an ethical obligation to put themselves in danger of serious bodily harm.15 While there is no one-size-fits-all answer to the question of whether or not to press charges against a patient who has committed an assault, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration considers the perception that violence is tolerated and victims are unable to report to law enforcement an organizational risk factor for workplace violence.16

As leaders in the workplace, physicians should set the precedent that violence will not be tolerated by reporting incidents to police and filing charges when appropriate. In the case of Dr. M, she received full support from her institution’s administration in filing charges against Mr. B due to the specific details of the assault.

3. Easing back into the environment

Despite assurances from her superiors that she could take time off, Dr. M wanted to return to work as soon as possible. She considered the balance between her physical injuries and desire to return to work and ultimately returned to work 5 days after the assault. She did well with supportive measures from administration and other staff, including the use of technician escorts on the unit, peer support, and frequent communication with and check-ins from management.

The decision on how quickly to return to work should always lie with the individual who was assaulted. The administration should offer time off without hesitation. Victims of an assault may feel overwhelmed by 2 diverging paths on how to return to a traumatic environment: avoid the location at all costs, or try to “face their fears” and return as quickly as possible. Research from outside medicine indicates that the timing of returning to work after a traumatic injury may not be nearly as important as the method of returning, and who makes this decision.17 Predictors of return to work after an assault include not only the severity of the trauma and amount of distress symptoms, but also any actual or perceived injustice on the part of the victim.17 Although this study was not specific to health care employees, it suggests that overall, an employee who does not feel a sense of control over their choice to return to work could perceive that as an injustice on the part of administration, leading to decreased job satisfaction.17

A study by Lamothe et al18 that was specific to health care professionals found that despite the importance of self-efficacy for the assault victim, perceived organizational support had an even greater protective effect following patient violence.Additionally, monitoring for signs of distress among victims after an episode of violence could prevent further violence by reducing the risk for subsequent victimization.18 This highlights the need for leadership of an inpatient unit to be keenly aware of how an assault on a psychiatrist or other health care professional may change the work environment and create a need to help staff navigate the new normal they may face on the unit.

Continue to: Finding long-term support

4. Finding long-term support

Longitudinal support is key in the initial transition back to work, as well as in the following weeks and months. Studies assessing the impacts of patient assault on mental health nurses indicate that while most individuals exposed to a traumatic event do not develop PTSD, many reported continued somatic symptoms, and more still reported ongoing psychological effects such as recurring thoughts of the assault, fear, generalized anger, and feeling a loss of control.8 Peer support is a common method employed by physicians and nurses alike, but administrative support is also essential.8

Regardless which form of psychotherapy, medication treatment, or peer support is utilized, access to the tools the psychiatrist finds most helpful is crucial to making them feel safe and comfortable returning to their role. Table 2 details practical steps administrators and peers can take to facilitate longitudinal support in these situations. In the case of Dr. M, administration was not only supportive in encouraging time off, but also in allowing protected time for therapy when she endorsed distress over the event. The combination of immediate responses and more long-term support greatly helped Dr. M continue her role as a psychiatrist and remain satisfied with her work.

Bottom Line

Being assaulted by a patient can make a psychiatrist reluctant to return to work. Strategies to ease this transition include seeking immediate care, removing the patient from the care of the psychiatrist who was assaulted, easing back into the environment, and finding long-term support.

Related Resources

- Lapic S, Joshi KG. What to do after a patient assaults you. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(10):53-54.

- Joshi KG. Workplace violence: enhance your safety in outpatient settings. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(8):37-38. doi:10.12788/cp.0163

- Su D. Harassment of health care workers: a survey. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(6):48-50. doi:10.12788/cp.0135

- Rozel JS, Wiles C, Amin P. Too close for comfort: when the psychiatrist is stalked. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(1): 23-28. doi:10.12788/cp.0209

1. Odes R, Chapman S, Harrison R, et al. Frequency of violence towards healthcare workers in the United States’ inpatient psychiatric hospitals: a systematic review of literature. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2021;30(1):27-46.

2. Chaimowitz GA, Moscovitch A. Patient assaults on psychiatric residents: the Canadian experience. Can J Psychiatry. 1991;36(2):107-111.

3. Faulkner LR, Grimm NR, MacFarland BH, et al. Threats and assaults against psychiatrists. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1990;18(1):37-46.

4. Carmel H, Hunter M. Psychiatrists injured by patient attack. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1991;19(3):309-316.

5. Kwok S, Ostermeyer B, Coverdale J. A systematic review of the prevalence of patient assaults against residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(3):296-300.

6. Weltens I, Bak M, Verhagen S, et al. Aggression on the psychiatric ward: prevalence and risk factors. A systematic review of the literature. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0258346.

7. Moylan L, McManus M, Cullinan M, et al. Need for specialized support services for nurse victims of physical assault by psychiatric patients. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2016;37(7):446-450.

8. Dean L, Butler A, Cuddigan J. The impact of workplace violence toward psychiatric mental health nurses: identifying the facilitators and barriers to supportive resources. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2021;27(3):189-202.

9. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common program requirements (Residency). July 2023. Accessed September 20, 2023. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/cprresidency_2023v3.pdf

10. WELL Toolkit. UPMC GME Well-Being. October 3, 2022. Accessed September 20, 2023. https://gmewellness.upmc.com/

11. Rose S, Bisson J, Churchill R, et al. Psychological debriefing for preventing post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD000560.

12. Flannery RB Jr, Farley E, Rego S, et al. Characteristics of staff victims of psychiatric patient assaults: 15-year analysis of the Assaulted Staff Action Program (ASAP). Psychiatr Q. 2007;78(1):25-37.

13. Gispen F, Wu AW. Psychological first aid: CPR for mental health crises in healthcare. J Patient Saf Risk Manag. 2018:23(2):51-53.

14. Phillips JP. Workplace violence against health care workers in the United States. N Eng J Med. 2016;374(17):1661-1669.

15. Baby M, Glue P, Carlyle D. ‘Violence is not part of our job’: a thematic analysis of psychiatric mental health nurses’ experiences of patient assaults from a New Zealand perspective. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2014;35(9):647-655.

16. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Guidelines for Preventing Workplace Violence for Healthcare and Social Service Workers. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, US Dept of Labor; 2015.

17. Giummarra, MJ, Cameron PA, Ponsford J, et al. Return to work after traumatic injury: increased work-related disability in injured persons receiving financial compensation is mediated by perceived injustice. J Occup Rehabil. 2017;27(2):173-185.

18. Lamothe J, Boyer R, Guay S. A longitudinal analysis of psychological distress among healthcare workers following patient violence. Can J Behav Sci. 2021;53(1):48-58.

1. Odes R, Chapman S, Harrison R, et al. Frequency of violence towards healthcare workers in the United States’ inpatient psychiatric hospitals: a systematic review of literature. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2021;30(1):27-46.

2. Chaimowitz GA, Moscovitch A. Patient assaults on psychiatric residents: the Canadian experience. Can J Psychiatry. 1991;36(2):107-111.

3. Faulkner LR, Grimm NR, MacFarland BH, et al. Threats and assaults against psychiatrists. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1990;18(1):37-46.

4. Carmel H, Hunter M. Psychiatrists injured by patient attack. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1991;19(3):309-316.

5. Kwok S, Ostermeyer B, Coverdale J. A systematic review of the prevalence of patient assaults against residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(3):296-300.

6. Weltens I, Bak M, Verhagen S, et al. Aggression on the psychiatric ward: prevalence and risk factors. A systematic review of the literature. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0258346.

7. Moylan L, McManus M, Cullinan M, et al. Need for specialized support services for nurse victims of physical assault by psychiatric patients. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2016;37(7):446-450.

8. Dean L, Butler A, Cuddigan J. The impact of workplace violence toward psychiatric mental health nurses: identifying the facilitators and barriers to supportive resources. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2021;27(3):189-202.

9. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common program requirements (Residency). July 2023. Accessed September 20, 2023. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/cprresidency_2023v3.pdf

10. WELL Toolkit. UPMC GME Well-Being. October 3, 2022. Accessed September 20, 2023. https://gmewellness.upmc.com/

11. Rose S, Bisson J, Churchill R, et al. Psychological debriefing for preventing post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD000560.

12. Flannery RB Jr, Farley E, Rego S, et al. Characteristics of staff victims of psychiatric patient assaults: 15-year analysis of the Assaulted Staff Action Program (ASAP). Psychiatr Q. 2007;78(1):25-37.

13. Gispen F, Wu AW. Psychological first aid: CPR for mental health crises in healthcare. J Patient Saf Risk Manag. 2018:23(2):51-53.

14. Phillips JP. Workplace violence against health care workers in the United States. N Eng J Med. 2016;374(17):1661-1669.

15. Baby M, Glue P, Carlyle D. ‘Violence is not part of our job’: a thematic analysis of psychiatric mental health nurses’ experiences of patient assaults from a New Zealand perspective. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2014;35(9):647-655.

16. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Guidelines for Preventing Workplace Violence for Healthcare and Social Service Workers. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, US Dept of Labor; 2015.

17. Giummarra, MJ, Cameron PA, Ponsford J, et al. Return to work after traumatic injury: increased work-related disability in injured persons receiving financial compensation is mediated by perceived injustice. J Occup Rehabil. 2017;27(2):173-185.

18. Lamothe J, Boyer R, Guay S. A longitudinal analysis of psychological distress among healthcare workers following patient violence. Can J Behav Sci. 2021;53(1):48-58.