User login

Treatment of Acetabular Fractures in Adolescents

In children, pelvic fractures are uncommon, with an incidence ranging from 1% to 4.6% of all pediatric fractures,1-4 and acetabular fractures make up only 0.8% to 15% of pelvic fractures.1,3,5,6 Acetabular fractures are so uncommon in children partly because of the cartilaginous nature of the immature acetabulum. The increased cartilage volume relative to adults provides greater capacity for energy absorption, resulting in greater elastic and plastic deformation before fracture occurrence. More force is therefore required to cause a fracture, and associated visceral injuries, head injuries, and long-bone fractures are common.3,7,8

The impact of acetabular fractures on adolescents warrants special attention because any resulting disability will affect them during their most productive years. Both avascular necrosis (AVN) and degenerative arthritis are particularly devastating complications in this age group. Complications such as premature physeal closure9-15 are unique to adolescents, and there is little information available on how injury in older children affects growth in this area.

There have been very few studies of the outcomes of these injuries in children. Mostly, there have been case reports and small series primarily dealing with nonoperative management of acetabular fractures in adolescents.3,10,11,16-20 By contrast, operative treatment of acetabular fractures in adults has been well described, and outcomes widely reported. As a result, much of our knowledge about managing these injuries is extrapolated from the adult literature. Although treatment of acetabular fractures in adults has evolved substantially, treatment of these injuries in adolescents remains primarily nonoperative. We conducted a study to evaluate outcomes of treatment of adolescent acetabular fractures.

Patients and Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval for this study, we retrospectively reviewed the cases of all adolescent patients admitted with a diagnosis of acetabular fracture to 2 academic institutions between 1991 and 2003. Thirty-eight patients (28 males, 10 females) were identified. Mean age at time of injury was 15 years (range, 11-18 years). Mean follow-up was 3.2 years (range, 5-180 months).

Data on fracture types, treatment methods, associated injuries, complications, union rates, pain, and return to normal activities were collected. Acetabular fractures were classified according to the system of Letournel and Judet.21 There were 20 elementary and 18 associated fractures.

Of the 38 patients, 30 sustained high-energy trauma in motor vehicle accidents (25) or in falls from significant heights (5). The other 8 patients injured themselves playing sports (4 had severe traumatic brain injury, 2 had labial wounds, and 2 had injuries involving the abdominal viscera). Twelve patients had associated pelvic ring injuries, 18 had femoral head dislocations, 2 had femoral head fractures, and 13 had evidence of impaction injury to the femoral head articular cartilage. Twelve patients had marginal impaction of the acetabular wall. Fifteen patients had open triradiate physes at time of injury (Table 1).

Thirty-seven of the 38 patients were treated with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) by an experienced orthopedic trauma surgeon; 1 patient with a stable posterior wall fracture was treated nonoperatively. Surgical indications were articular displacement of more than 1 mm, hip joint instability, irreducible hip dislocation, and intra-articular fracture fragments. In the 37 surgically treated cases, the approaches used were Kocher-Langenbeck (22), ilioinguinal (8), combined Kocher-Langenbeck/ilioinguinal (5), and triradiate (2).

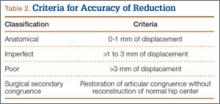

Immediate postoperative radiographs were evaluated by 3 orthopedic surgeons blinded to the patients’ clinical outcomes. Displacement was evaluated on anteroposterior (AP) and Judet views of the pelvis, as described by Matta,22 and reductions were classified as anatomical (0-1 mm of displacement), imperfect (>1 to 3 mm), poor (>3 mm), or surgical secondary congruence (Table 2).

Results

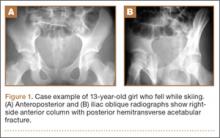

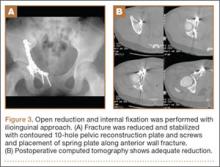

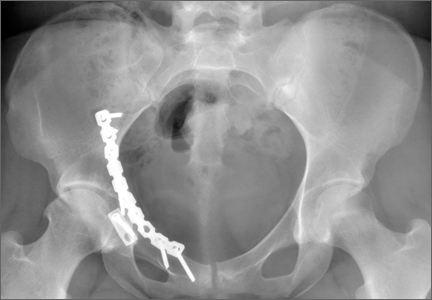

Thirty-seven patients underwent acetabular fracture ORIF. Immediate postoperative radiographs showed 30 anatomical reductions and 7 imperfect reductions. One patient had surgical secondary congruence and developed AVN of the hip. We could not identify an association between the quality of the reduction and the outcome with respect to pain or return to activity. However, no patient had a poor reduction. An illustrative case is presented in Figures 1 to 4.

All acetabular fractures united within 4.5 months (range, 3.0-8.0 months) after the index procedure. Early postoperative complications included 3 cases of meralgia paresthetica and 13 cases of abductor weakness. Meralgia paresthetica resolved spontaneously in all 3 patients. Of the 13 patients with abductor weakness, 11 improved with physical therapy, 1 was limited by the head injury, and 1 subsequently underwent hip fusion. One patient had a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) that was identified before surgery and managed with warfarin.

Other complications included 1 case of deep infection of the surgical wound. This infection presented 4 months after surgery and was treated with débridement, hardware removal, and a 3-month course of antibiotics. Two patients who sustained hip dislocations at time of injury developed AVN of the femoral head. Both developed osteoarthritis, and 1 underwent hip fusion. Eight patients developed heterotopic ossification on the side of the acetabular fracture; 4 of them underwent surgical excision. Four patients required a separate operation for hardware removal. Four patients with triradiate cartilage involvement went on to premature closure. No patient had any leg-length discrepancy or dysplasia at time of follow-up.

Thirty-four of the 38 patients returned to their regular activities. For these patients, mean time to return to full activity was 7.0 months (range, 3-30 months); there was no difference in mean time to return to full activity between skeletally mature and skeletally immature patients (6.6 vs 7.4 months; P = .57). Of the other 4 patients, 1 had permanent cognitive and physical disability with an ataxic gait as a result of a traumatic brain injury, 2 were limited by AVN (1 underwent hip fusion), and 1 was limited by an ipsilateral knee injury.

Of the 38 patients, 29 were pain-free; 6 had occasional, intermittent mild pain that did not limit their activities; and 3 had severe, activity-limiting pain. Of the 6 patients with mild pain, 2 had femoral impaction injuries, and 4 had marginal impaction injuries. Of the 3 patients with severe pain, 2 developed femoral head AVN, and 1 had multiple ipsilateral extremity injuries involving the femur, knee, and tibia.

Discussion

The traditional treatment for acetabular fractures in children has been nonoperative,8,10 and there are few specific treatment guidelines.13 Recent recommendations are nonoperative treatment for minimally displaced fractures (<1 mm) and acetabular fracture ORIF for fractures displaced more than 2 mm.11 No clear consensus exists on management for fractures displaced 1 to 2 mm. Few studies have investigated the outcomes of operative management of these fractures in the pediatric or adolescent population.

In our series of adolescent acetabular fractures, we examined unions, complications, and return to activity. Of 38 patients with acetabular fractures, 37 were treated with ORIF. Anatomical reduction was achieved in the majority of patients. Posterior wall fractures were by far the most common fracture type, which is consistent with previous reports.10,11 All acetabular fractures united, and most patients were pain-free at latest follow-up. There was a low incidence of major complications in our patient population. One major complication was a DVT in a 14-year-old boy who was in a motor vehicle accident and sustained a T-type fracture of the right acetabulum with contralateral femoral shaft and ankle fractures. The DVT was in the right internal iliac and common femoral veins and was diagnosed on magnetic resonance venography. The patient was treated with warfarin for 3 months without incident.

Two patients developed AVN of the femoral head. One of these patients was an 11-year-old girl who was in a motor vehicle accident and sustained a T-type fracture with marginal impaction of the posterior wall, posterior hip dislocation, and a pelvic ring injury. She was treated with ORIF through combined Kocher-Langenbeck/ilioinguinal approaches. By 4 months after surgery, the acetabular fracture was united. Nine months after surgery, she still had pain (activity-limiting) and a 35° flexion contracture of the hip, and she was ambulating with a cane. The diagnosis was AVN of the hip. The patient underwent hip fusion 1 year after surgery.

The second patient with femoral head AVN was a 12-year-old boy who fell while skiing and sustained a fracture of the posterior wall and a hip dislocation with impaction of the femoral head. Initial treatment at an outside institution consisted of open reduction of the hip and excision of a “loose body” from the joint. Eight weeks after surgery, the patient continued to have pain and was referred to our institution. A second operation was performed. Findings included a defect involving 40% of the posterior wall, and signs that the posterior wall had been excised during the initial operation. The patient eventually developed AVN of the hip. This patient was also diagnosed with a deep wound infection 4 months after surgery. He presented with pain and a fluid collection around the hip. The infection was not confirmed through fluid culture, and, as he eventually developed AVN of the hip, his symptoms may have been the result of chondrolysis or AVN rather than infection.

There were no cases of nonunion or malunion, leg-length discrepancy, or permanent sciatic nerve palsy. Although there were a few cases of premature closure of the triradiate cartilage, no acetabular dysplasia was seen at latest follow-up, likely because of the relative maturity of our pediatric group (age range, 11-18 years). Age at time of injury is thought to be the most important factor influencing growth and development of the acetabulum.9,13 In addition, previous studies have demonstrated a tendency toward acetabular fractures in patients with mature triradiate cartilage—versus pelvic ring injuries in patients with immature triradiate cartilage.8,11 This may also account for the older age of our study group.

Minor complications (eg, meralgia paresthetica) resolved spontaneously. The most common complications were abductor weakness and heterotopic ossification. In only 4 cases was a secondary procedure for excision of the heterotopic bone required. Abductor weakness, more commonly associated with a Kocher-Langenbeck approach to the hip, resolved with therapy in almost all cases. Only 4 of our patients required removal of hardware from the acetabulum.

Although the majority of acetabular fractures resulted from high-energy trauma, 8 cases were sports-related. Six of these involved posterior wall fractures, suggesting the injury resulted from a fall on flexed knee and hip. This was not known to be a common mechanism of injury in this age group.3,7 An additional concern was how to size the posterior wall fragment when not ossified. At one center, preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was effectively used to size the osteochondral posterior wall fragment as standard protocol for patients with posterior wall fractures in this age group—resulting in better decisions regarding the need for ORIF. At the other institution, preoperative MRI was not performed routinely for this subset of patients.

Thirty-four of our 38 patients returned to their normal activities. Of the other 4 patients, 1 was permanently disabled secondary to traumatic brain injury, 1 had other ipsilateral extremity injuries that limited his mobility, and 2 developed AVN of the femoral head. Both patients with AVN had hip dislocations. Four of the 6 patients who were symptomatic during activity sustained impaction injuries of the femoral head or posterior wall. This suggests that poorer outcomes may be associated with dislocation or with articular injuries—similar to what has been reported in the adult literature.

This study had several limitations. First, it was a retrospective case series, so there was no control group for comparison. Second, the relatively short follow-up did not allow evaluation of the incidence of degenerative arthritis secondary to articular injury, the symptoms of which may develop 1 to 2 decades after injury.13 This phenomenon was well described by Letournel and Judet21 in the adult population, and there is no reason to presume the adolescent population is any different. Third, our sample was small and unlikely to represent a uniform sampling of the general pediatric population. Fourth, it was not possible to draw detailed conclusions about the outcome of ORIF for a particular type of acetabular fracture. Fifth, we did not see as many of the associated visceral injuries that are so prevalent in the literature. This may reflect improvement in safety specifications for automobiles, or our group may not have had the most severe or high-energy injuries. Here our population sample may have skewed our results, leading to better than expected outcomes.

One last study limitation, a major one, was the age of our population, 11 to 18 years, which makes it difficult to extrapolate results to the entire pediatric population. On one hand, a more immature skeleton has a higher chance of remodeling and is more forgiving of deformities and small amounts of displacement. On the other hand, injury and premature triradiate cartilage fusion in a younger patient can lead to significant deformity and acetabular dysplasia.9 Whether ORIF of these fractures would alter the outcome of an injury to the triradiate cartilage is yet to be determined.

Conclusion

In agreement with earlier studies,10,11,15,18 the good outcomes in our series correlated with congruence of reduction. Outcome predictors such as dislocation, femoral head injury, and marginal impaction are similar to those described in the adult literature. Although our study did not have a nonoperative group for comparison, the favorable outcomes of ORIF of acetabular fractures suggest that a more aggressive approach to treatment should be considered. Given the added benefits of early, pain-free mobilization, we think that only stable, undisplaced fractures (<1 mm) should be managed nonoperatively. In the adolescent population, we recommend ORIF for optimal management of unstable acetabular fractures, fractures with any hip subluxation, and fractures displaced more than 1 mm.

1. Canale ST, Beaty JH. Fractures of the pelvis. In: Beaty JH, Kassler JR, eds. Rockwood and Wilkin’s Fractures in Children. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:883-991.

2. Demetriades D, Karaiskakis M, Velmahos GC, Alo K, Murray J, Chan L. Pelvic fractures in pediatric and adult trauma patients: are they different injuries? J Trauma. 2003;54(6):1146-1151.

3. Grisoni N, Connor S, Marsh E, Thompson GH, Cooperman DR, Blakemore LC. Pelvic fractures in a pediatric level I trauma center. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16(7):458-463.

4. Ismail N, Bellemare JF, Mollitt DL, Di Scala C, Koeppel B, Tepas JJ. Death from pelvic fracture: children are different. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31(1):82-85.

5. Schlickwei W, Keck T. Pelvic and acetabular fractures in childhood. Injury. 2005;36(suppl 1):A57-A63.

6. Swiontkowski MF. Fractures and dislocations about the hip and pelvis. In: Green NE, Swiontkowski MF, eds. Skeletal Trauma in Children. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2003:371-406.

7. Silber JS, Flynn JM, Koffler KM, Dormans JP, Drummond DS. Analysis of the cause, classification, and associated injuries of 166 consecutive pediatric pelvic fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21(4):446-450.

8. Silber JS, Flynn JM. Changing patterns of pediatric pelvic fractures with skeletal maturation: implications for classification and management. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22(1):22-26.

9. Bucholz RW, Ezaki M, Ogden JA. Injury to the acetabular triradiate physeal cartilage. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64(4):600-609.

10. Heeg M, Klasen HJ, Visser JD. Acetabular fractures in children and adolescents. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989;71(3):418-421.

11. Heeg M, de Ridder VA, Tornetta P, de Lange S, Klasen HJ. Acetabular fractures in children and adolescents. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;(376):80-86.

12. Heeg M, Visser JD, Oostvogel HJ. Injuries of the acetabular triradiate cartilage and sacroiliac joint. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70(1):34-37.

13. Liporace FA, Ong B, Mohaideen A, Ong A, Koval KJ. Development and injury of the triradiate cartilage with its effects on acetabular development: review of the literature. J Trauma. 2003;54(6):1245-1249.

14. Rodrigues KF. Injury of the acetabular epiphysis. Injury. 1973;4(3):258-260.

15. Trousdale RT, Ganz R. Posttraumatic acetabular dysplasia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;(305):124-132.

16. Brooks E, Rosman M. Central fracture-dislocation of the hip in a child. J Trauma. 1988;28(11):1590-1592.

17. Habacker TA, Heinrich SD, Dehne R. Fracture of the superior pelvic quadrant in a child. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;15(1):69-72.

18. Karunakar MA, Goulet JA, Mueller KL, Bedi A, Le TT. Operative treatment of unstable pediatric pelvis and acetabular fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(1):34-38.

19. Rieger H, Brug E. Fractures of the pelvis in children. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;(336);226-239.

20. Torode I, Zieg D. Pelvic fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1985;5(1):76-84.

21. Letournel E, Judet R. Fractures of the Acetabulum. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1993.

22. Matta JM. Fractures of the acetabulum: accuracy of reduction and clinical results in patients managed operatively within three weeks of the injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(11):1632-1645.

In children, pelvic fractures are uncommon, with an incidence ranging from 1% to 4.6% of all pediatric fractures,1-4 and acetabular fractures make up only 0.8% to 15% of pelvic fractures.1,3,5,6 Acetabular fractures are so uncommon in children partly because of the cartilaginous nature of the immature acetabulum. The increased cartilage volume relative to adults provides greater capacity for energy absorption, resulting in greater elastic and plastic deformation before fracture occurrence. More force is therefore required to cause a fracture, and associated visceral injuries, head injuries, and long-bone fractures are common.3,7,8

The impact of acetabular fractures on adolescents warrants special attention because any resulting disability will affect them during their most productive years. Both avascular necrosis (AVN) and degenerative arthritis are particularly devastating complications in this age group. Complications such as premature physeal closure9-15 are unique to adolescents, and there is little information available on how injury in older children affects growth in this area.

There have been very few studies of the outcomes of these injuries in children. Mostly, there have been case reports and small series primarily dealing with nonoperative management of acetabular fractures in adolescents.3,10,11,16-20 By contrast, operative treatment of acetabular fractures in adults has been well described, and outcomes widely reported. As a result, much of our knowledge about managing these injuries is extrapolated from the adult literature. Although treatment of acetabular fractures in adults has evolved substantially, treatment of these injuries in adolescents remains primarily nonoperative. We conducted a study to evaluate outcomes of treatment of adolescent acetabular fractures.

Patients and Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval for this study, we retrospectively reviewed the cases of all adolescent patients admitted with a diagnosis of acetabular fracture to 2 academic institutions between 1991 and 2003. Thirty-eight patients (28 males, 10 females) were identified. Mean age at time of injury was 15 years (range, 11-18 years). Mean follow-up was 3.2 years (range, 5-180 months).

Data on fracture types, treatment methods, associated injuries, complications, union rates, pain, and return to normal activities were collected. Acetabular fractures were classified according to the system of Letournel and Judet.21 There were 20 elementary and 18 associated fractures.

Of the 38 patients, 30 sustained high-energy trauma in motor vehicle accidents (25) or in falls from significant heights (5). The other 8 patients injured themselves playing sports (4 had severe traumatic brain injury, 2 had labial wounds, and 2 had injuries involving the abdominal viscera). Twelve patients had associated pelvic ring injuries, 18 had femoral head dislocations, 2 had femoral head fractures, and 13 had evidence of impaction injury to the femoral head articular cartilage. Twelve patients had marginal impaction of the acetabular wall. Fifteen patients had open triradiate physes at time of injury (Table 1).

Thirty-seven of the 38 patients were treated with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) by an experienced orthopedic trauma surgeon; 1 patient with a stable posterior wall fracture was treated nonoperatively. Surgical indications were articular displacement of more than 1 mm, hip joint instability, irreducible hip dislocation, and intra-articular fracture fragments. In the 37 surgically treated cases, the approaches used were Kocher-Langenbeck (22), ilioinguinal (8), combined Kocher-Langenbeck/ilioinguinal (5), and triradiate (2).

Immediate postoperative radiographs were evaluated by 3 orthopedic surgeons blinded to the patients’ clinical outcomes. Displacement was evaluated on anteroposterior (AP) and Judet views of the pelvis, as described by Matta,22 and reductions were classified as anatomical (0-1 mm of displacement), imperfect (>1 to 3 mm), poor (>3 mm), or surgical secondary congruence (Table 2).

Results

Thirty-seven patients underwent acetabular fracture ORIF. Immediate postoperative radiographs showed 30 anatomical reductions and 7 imperfect reductions. One patient had surgical secondary congruence and developed AVN of the hip. We could not identify an association between the quality of the reduction and the outcome with respect to pain or return to activity. However, no patient had a poor reduction. An illustrative case is presented in Figures 1 to 4.

All acetabular fractures united within 4.5 months (range, 3.0-8.0 months) after the index procedure. Early postoperative complications included 3 cases of meralgia paresthetica and 13 cases of abductor weakness. Meralgia paresthetica resolved spontaneously in all 3 patients. Of the 13 patients with abductor weakness, 11 improved with physical therapy, 1 was limited by the head injury, and 1 subsequently underwent hip fusion. One patient had a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) that was identified before surgery and managed with warfarin.

Other complications included 1 case of deep infection of the surgical wound. This infection presented 4 months after surgery and was treated with débridement, hardware removal, and a 3-month course of antibiotics. Two patients who sustained hip dislocations at time of injury developed AVN of the femoral head. Both developed osteoarthritis, and 1 underwent hip fusion. Eight patients developed heterotopic ossification on the side of the acetabular fracture; 4 of them underwent surgical excision. Four patients required a separate operation for hardware removal. Four patients with triradiate cartilage involvement went on to premature closure. No patient had any leg-length discrepancy or dysplasia at time of follow-up.

Thirty-four of the 38 patients returned to their regular activities. For these patients, mean time to return to full activity was 7.0 months (range, 3-30 months); there was no difference in mean time to return to full activity between skeletally mature and skeletally immature patients (6.6 vs 7.4 months; P = .57). Of the other 4 patients, 1 had permanent cognitive and physical disability with an ataxic gait as a result of a traumatic brain injury, 2 were limited by AVN (1 underwent hip fusion), and 1 was limited by an ipsilateral knee injury.

Of the 38 patients, 29 were pain-free; 6 had occasional, intermittent mild pain that did not limit their activities; and 3 had severe, activity-limiting pain. Of the 6 patients with mild pain, 2 had femoral impaction injuries, and 4 had marginal impaction injuries. Of the 3 patients with severe pain, 2 developed femoral head AVN, and 1 had multiple ipsilateral extremity injuries involving the femur, knee, and tibia.

Discussion

The traditional treatment for acetabular fractures in children has been nonoperative,8,10 and there are few specific treatment guidelines.13 Recent recommendations are nonoperative treatment for minimally displaced fractures (<1 mm) and acetabular fracture ORIF for fractures displaced more than 2 mm.11 No clear consensus exists on management for fractures displaced 1 to 2 mm. Few studies have investigated the outcomes of operative management of these fractures in the pediatric or adolescent population.

In our series of adolescent acetabular fractures, we examined unions, complications, and return to activity. Of 38 patients with acetabular fractures, 37 were treated with ORIF. Anatomical reduction was achieved in the majority of patients. Posterior wall fractures were by far the most common fracture type, which is consistent with previous reports.10,11 All acetabular fractures united, and most patients were pain-free at latest follow-up. There was a low incidence of major complications in our patient population. One major complication was a DVT in a 14-year-old boy who was in a motor vehicle accident and sustained a T-type fracture of the right acetabulum with contralateral femoral shaft and ankle fractures. The DVT was in the right internal iliac and common femoral veins and was diagnosed on magnetic resonance venography. The patient was treated with warfarin for 3 months without incident.

Two patients developed AVN of the femoral head. One of these patients was an 11-year-old girl who was in a motor vehicle accident and sustained a T-type fracture with marginal impaction of the posterior wall, posterior hip dislocation, and a pelvic ring injury. She was treated with ORIF through combined Kocher-Langenbeck/ilioinguinal approaches. By 4 months after surgery, the acetabular fracture was united. Nine months after surgery, she still had pain (activity-limiting) and a 35° flexion contracture of the hip, and she was ambulating with a cane. The diagnosis was AVN of the hip. The patient underwent hip fusion 1 year after surgery.

The second patient with femoral head AVN was a 12-year-old boy who fell while skiing and sustained a fracture of the posterior wall and a hip dislocation with impaction of the femoral head. Initial treatment at an outside institution consisted of open reduction of the hip and excision of a “loose body” from the joint. Eight weeks after surgery, the patient continued to have pain and was referred to our institution. A second operation was performed. Findings included a defect involving 40% of the posterior wall, and signs that the posterior wall had been excised during the initial operation. The patient eventually developed AVN of the hip. This patient was also diagnosed with a deep wound infection 4 months after surgery. He presented with pain and a fluid collection around the hip. The infection was not confirmed through fluid culture, and, as he eventually developed AVN of the hip, his symptoms may have been the result of chondrolysis or AVN rather than infection.

There were no cases of nonunion or malunion, leg-length discrepancy, or permanent sciatic nerve palsy. Although there were a few cases of premature closure of the triradiate cartilage, no acetabular dysplasia was seen at latest follow-up, likely because of the relative maturity of our pediatric group (age range, 11-18 years). Age at time of injury is thought to be the most important factor influencing growth and development of the acetabulum.9,13 In addition, previous studies have demonstrated a tendency toward acetabular fractures in patients with mature triradiate cartilage—versus pelvic ring injuries in patients with immature triradiate cartilage.8,11 This may also account for the older age of our study group.

Minor complications (eg, meralgia paresthetica) resolved spontaneously. The most common complications were abductor weakness and heterotopic ossification. In only 4 cases was a secondary procedure for excision of the heterotopic bone required. Abductor weakness, more commonly associated with a Kocher-Langenbeck approach to the hip, resolved with therapy in almost all cases. Only 4 of our patients required removal of hardware from the acetabulum.

Although the majority of acetabular fractures resulted from high-energy trauma, 8 cases were sports-related. Six of these involved posterior wall fractures, suggesting the injury resulted from a fall on flexed knee and hip. This was not known to be a common mechanism of injury in this age group.3,7 An additional concern was how to size the posterior wall fragment when not ossified. At one center, preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was effectively used to size the osteochondral posterior wall fragment as standard protocol for patients with posterior wall fractures in this age group—resulting in better decisions regarding the need for ORIF. At the other institution, preoperative MRI was not performed routinely for this subset of patients.

Thirty-four of our 38 patients returned to their normal activities. Of the other 4 patients, 1 was permanently disabled secondary to traumatic brain injury, 1 had other ipsilateral extremity injuries that limited his mobility, and 2 developed AVN of the femoral head. Both patients with AVN had hip dislocations. Four of the 6 patients who were symptomatic during activity sustained impaction injuries of the femoral head or posterior wall. This suggests that poorer outcomes may be associated with dislocation or with articular injuries—similar to what has been reported in the adult literature.

This study had several limitations. First, it was a retrospective case series, so there was no control group for comparison. Second, the relatively short follow-up did not allow evaluation of the incidence of degenerative arthritis secondary to articular injury, the symptoms of which may develop 1 to 2 decades after injury.13 This phenomenon was well described by Letournel and Judet21 in the adult population, and there is no reason to presume the adolescent population is any different. Third, our sample was small and unlikely to represent a uniform sampling of the general pediatric population. Fourth, it was not possible to draw detailed conclusions about the outcome of ORIF for a particular type of acetabular fracture. Fifth, we did not see as many of the associated visceral injuries that are so prevalent in the literature. This may reflect improvement in safety specifications for automobiles, or our group may not have had the most severe or high-energy injuries. Here our population sample may have skewed our results, leading to better than expected outcomes.

One last study limitation, a major one, was the age of our population, 11 to 18 years, which makes it difficult to extrapolate results to the entire pediatric population. On one hand, a more immature skeleton has a higher chance of remodeling and is more forgiving of deformities and small amounts of displacement. On the other hand, injury and premature triradiate cartilage fusion in a younger patient can lead to significant deformity and acetabular dysplasia.9 Whether ORIF of these fractures would alter the outcome of an injury to the triradiate cartilage is yet to be determined.

Conclusion

In agreement with earlier studies,10,11,15,18 the good outcomes in our series correlated with congruence of reduction. Outcome predictors such as dislocation, femoral head injury, and marginal impaction are similar to those described in the adult literature. Although our study did not have a nonoperative group for comparison, the favorable outcomes of ORIF of acetabular fractures suggest that a more aggressive approach to treatment should be considered. Given the added benefits of early, pain-free mobilization, we think that only stable, undisplaced fractures (<1 mm) should be managed nonoperatively. In the adolescent population, we recommend ORIF for optimal management of unstable acetabular fractures, fractures with any hip subluxation, and fractures displaced more than 1 mm.

In children, pelvic fractures are uncommon, with an incidence ranging from 1% to 4.6% of all pediatric fractures,1-4 and acetabular fractures make up only 0.8% to 15% of pelvic fractures.1,3,5,6 Acetabular fractures are so uncommon in children partly because of the cartilaginous nature of the immature acetabulum. The increased cartilage volume relative to adults provides greater capacity for energy absorption, resulting in greater elastic and plastic deformation before fracture occurrence. More force is therefore required to cause a fracture, and associated visceral injuries, head injuries, and long-bone fractures are common.3,7,8

The impact of acetabular fractures on adolescents warrants special attention because any resulting disability will affect them during their most productive years. Both avascular necrosis (AVN) and degenerative arthritis are particularly devastating complications in this age group. Complications such as premature physeal closure9-15 are unique to adolescents, and there is little information available on how injury in older children affects growth in this area.

There have been very few studies of the outcomes of these injuries in children. Mostly, there have been case reports and small series primarily dealing with nonoperative management of acetabular fractures in adolescents.3,10,11,16-20 By contrast, operative treatment of acetabular fractures in adults has been well described, and outcomes widely reported. As a result, much of our knowledge about managing these injuries is extrapolated from the adult literature. Although treatment of acetabular fractures in adults has evolved substantially, treatment of these injuries in adolescents remains primarily nonoperative. We conducted a study to evaluate outcomes of treatment of adolescent acetabular fractures.

Patients and Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval for this study, we retrospectively reviewed the cases of all adolescent patients admitted with a diagnosis of acetabular fracture to 2 academic institutions between 1991 and 2003. Thirty-eight patients (28 males, 10 females) were identified. Mean age at time of injury was 15 years (range, 11-18 years). Mean follow-up was 3.2 years (range, 5-180 months).

Data on fracture types, treatment methods, associated injuries, complications, union rates, pain, and return to normal activities were collected. Acetabular fractures were classified according to the system of Letournel and Judet.21 There were 20 elementary and 18 associated fractures.

Of the 38 patients, 30 sustained high-energy trauma in motor vehicle accidents (25) or in falls from significant heights (5). The other 8 patients injured themselves playing sports (4 had severe traumatic brain injury, 2 had labial wounds, and 2 had injuries involving the abdominal viscera). Twelve patients had associated pelvic ring injuries, 18 had femoral head dislocations, 2 had femoral head fractures, and 13 had evidence of impaction injury to the femoral head articular cartilage. Twelve patients had marginal impaction of the acetabular wall. Fifteen patients had open triradiate physes at time of injury (Table 1).

Thirty-seven of the 38 patients were treated with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) by an experienced orthopedic trauma surgeon; 1 patient with a stable posterior wall fracture was treated nonoperatively. Surgical indications were articular displacement of more than 1 mm, hip joint instability, irreducible hip dislocation, and intra-articular fracture fragments. In the 37 surgically treated cases, the approaches used were Kocher-Langenbeck (22), ilioinguinal (8), combined Kocher-Langenbeck/ilioinguinal (5), and triradiate (2).

Immediate postoperative radiographs were evaluated by 3 orthopedic surgeons blinded to the patients’ clinical outcomes. Displacement was evaluated on anteroposterior (AP) and Judet views of the pelvis, as described by Matta,22 and reductions were classified as anatomical (0-1 mm of displacement), imperfect (>1 to 3 mm), poor (>3 mm), or surgical secondary congruence (Table 2).

Results

Thirty-seven patients underwent acetabular fracture ORIF. Immediate postoperative radiographs showed 30 anatomical reductions and 7 imperfect reductions. One patient had surgical secondary congruence and developed AVN of the hip. We could not identify an association between the quality of the reduction and the outcome with respect to pain or return to activity. However, no patient had a poor reduction. An illustrative case is presented in Figures 1 to 4.

All acetabular fractures united within 4.5 months (range, 3.0-8.0 months) after the index procedure. Early postoperative complications included 3 cases of meralgia paresthetica and 13 cases of abductor weakness. Meralgia paresthetica resolved spontaneously in all 3 patients. Of the 13 patients with abductor weakness, 11 improved with physical therapy, 1 was limited by the head injury, and 1 subsequently underwent hip fusion. One patient had a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) that was identified before surgery and managed with warfarin.

Other complications included 1 case of deep infection of the surgical wound. This infection presented 4 months after surgery and was treated with débridement, hardware removal, and a 3-month course of antibiotics. Two patients who sustained hip dislocations at time of injury developed AVN of the femoral head. Both developed osteoarthritis, and 1 underwent hip fusion. Eight patients developed heterotopic ossification on the side of the acetabular fracture; 4 of them underwent surgical excision. Four patients required a separate operation for hardware removal. Four patients with triradiate cartilage involvement went on to premature closure. No patient had any leg-length discrepancy or dysplasia at time of follow-up.

Thirty-four of the 38 patients returned to their regular activities. For these patients, mean time to return to full activity was 7.0 months (range, 3-30 months); there was no difference in mean time to return to full activity between skeletally mature and skeletally immature patients (6.6 vs 7.4 months; P = .57). Of the other 4 patients, 1 had permanent cognitive and physical disability with an ataxic gait as a result of a traumatic brain injury, 2 were limited by AVN (1 underwent hip fusion), and 1 was limited by an ipsilateral knee injury.

Of the 38 patients, 29 were pain-free; 6 had occasional, intermittent mild pain that did not limit their activities; and 3 had severe, activity-limiting pain. Of the 6 patients with mild pain, 2 had femoral impaction injuries, and 4 had marginal impaction injuries. Of the 3 patients with severe pain, 2 developed femoral head AVN, and 1 had multiple ipsilateral extremity injuries involving the femur, knee, and tibia.

Discussion

The traditional treatment for acetabular fractures in children has been nonoperative,8,10 and there are few specific treatment guidelines.13 Recent recommendations are nonoperative treatment for minimally displaced fractures (<1 mm) and acetabular fracture ORIF for fractures displaced more than 2 mm.11 No clear consensus exists on management for fractures displaced 1 to 2 mm. Few studies have investigated the outcomes of operative management of these fractures in the pediatric or adolescent population.

In our series of adolescent acetabular fractures, we examined unions, complications, and return to activity. Of 38 patients with acetabular fractures, 37 were treated with ORIF. Anatomical reduction was achieved in the majority of patients. Posterior wall fractures were by far the most common fracture type, which is consistent with previous reports.10,11 All acetabular fractures united, and most patients were pain-free at latest follow-up. There was a low incidence of major complications in our patient population. One major complication was a DVT in a 14-year-old boy who was in a motor vehicle accident and sustained a T-type fracture of the right acetabulum with contralateral femoral shaft and ankle fractures. The DVT was in the right internal iliac and common femoral veins and was diagnosed on magnetic resonance venography. The patient was treated with warfarin for 3 months without incident.

Two patients developed AVN of the femoral head. One of these patients was an 11-year-old girl who was in a motor vehicle accident and sustained a T-type fracture with marginal impaction of the posterior wall, posterior hip dislocation, and a pelvic ring injury. She was treated with ORIF through combined Kocher-Langenbeck/ilioinguinal approaches. By 4 months after surgery, the acetabular fracture was united. Nine months after surgery, she still had pain (activity-limiting) and a 35° flexion contracture of the hip, and she was ambulating with a cane. The diagnosis was AVN of the hip. The patient underwent hip fusion 1 year after surgery.

The second patient with femoral head AVN was a 12-year-old boy who fell while skiing and sustained a fracture of the posterior wall and a hip dislocation with impaction of the femoral head. Initial treatment at an outside institution consisted of open reduction of the hip and excision of a “loose body” from the joint. Eight weeks after surgery, the patient continued to have pain and was referred to our institution. A second operation was performed. Findings included a defect involving 40% of the posterior wall, and signs that the posterior wall had been excised during the initial operation. The patient eventually developed AVN of the hip. This patient was also diagnosed with a deep wound infection 4 months after surgery. He presented with pain and a fluid collection around the hip. The infection was not confirmed through fluid culture, and, as he eventually developed AVN of the hip, his symptoms may have been the result of chondrolysis or AVN rather than infection.

There were no cases of nonunion or malunion, leg-length discrepancy, or permanent sciatic nerve palsy. Although there were a few cases of premature closure of the triradiate cartilage, no acetabular dysplasia was seen at latest follow-up, likely because of the relative maturity of our pediatric group (age range, 11-18 years). Age at time of injury is thought to be the most important factor influencing growth and development of the acetabulum.9,13 In addition, previous studies have demonstrated a tendency toward acetabular fractures in patients with mature triradiate cartilage—versus pelvic ring injuries in patients with immature triradiate cartilage.8,11 This may also account for the older age of our study group.

Minor complications (eg, meralgia paresthetica) resolved spontaneously. The most common complications were abductor weakness and heterotopic ossification. In only 4 cases was a secondary procedure for excision of the heterotopic bone required. Abductor weakness, more commonly associated with a Kocher-Langenbeck approach to the hip, resolved with therapy in almost all cases. Only 4 of our patients required removal of hardware from the acetabulum.

Although the majority of acetabular fractures resulted from high-energy trauma, 8 cases were sports-related. Six of these involved posterior wall fractures, suggesting the injury resulted from a fall on flexed knee and hip. This was not known to be a common mechanism of injury in this age group.3,7 An additional concern was how to size the posterior wall fragment when not ossified. At one center, preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was effectively used to size the osteochondral posterior wall fragment as standard protocol for patients with posterior wall fractures in this age group—resulting in better decisions regarding the need for ORIF. At the other institution, preoperative MRI was not performed routinely for this subset of patients.

Thirty-four of our 38 patients returned to their normal activities. Of the other 4 patients, 1 was permanently disabled secondary to traumatic brain injury, 1 had other ipsilateral extremity injuries that limited his mobility, and 2 developed AVN of the femoral head. Both patients with AVN had hip dislocations. Four of the 6 patients who were symptomatic during activity sustained impaction injuries of the femoral head or posterior wall. This suggests that poorer outcomes may be associated with dislocation or with articular injuries—similar to what has been reported in the adult literature.

This study had several limitations. First, it was a retrospective case series, so there was no control group for comparison. Second, the relatively short follow-up did not allow evaluation of the incidence of degenerative arthritis secondary to articular injury, the symptoms of which may develop 1 to 2 decades after injury.13 This phenomenon was well described by Letournel and Judet21 in the adult population, and there is no reason to presume the adolescent population is any different. Third, our sample was small and unlikely to represent a uniform sampling of the general pediatric population. Fourth, it was not possible to draw detailed conclusions about the outcome of ORIF for a particular type of acetabular fracture. Fifth, we did not see as many of the associated visceral injuries that are so prevalent in the literature. This may reflect improvement in safety specifications for automobiles, or our group may not have had the most severe or high-energy injuries. Here our population sample may have skewed our results, leading to better than expected outcomes.

One last study limitation, a major one, was the age of our population, 11 to 18 years, which makes it difficult to extrapolate results to the entire pediatric population. On one hand, a more immature skeleton has a higher chance of remodeling and is more forgiving of deformities and small amounts of displacement. On the other hand, injury and premature triradiate cartilage fusion in a younger patient can lead to significant deformity and acetabular dysplasia.9 Whether ORIF of these fractures would alter the outcome of an injury to the triradiate cartilage is yet to be determined.

Conclusion

In agreement with earlier studies,10,11,15,18 the good outcomes in our series correlated with congruence of reduction. Outcome predictors such as dislocation, femoral head injury, and marginal impaction are similar to those described in the adult literature. Although our study did not have a nonoperative group for comparison, the favorable outcomes of ORIF of acetabular fractures suggest that a more aggressive approach to treatment should be considered. Given the added benefits of early, pain-free mobilization, we think that only stable, undisplaced fractures (<1 mm) should be managed nonoperatively. In the adolescent population, we recommend ORIF for optimal management of unstable acetabular fractures, fractures with any hip subluxation, and fractures displaced more than 1 mm.

1. Canale ST, Beaty JH. Fractures of the pelvis. In: Beaty JH, Kassler JR, eds. Rockwood and Wilkin’s Fractures in Children. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:883-991.

2. Demetriades D, Karaiskakis M, Velmahos GC, Alo K, Murray J, Chan L. Pelvic fractures in pediatric and adult trauma patients: are they different injuries? J Trauma. 2003;54(6):1146-1151.

3. Grisoni N, Connor S, Marsh E, Thompson GH, Cooperman DR, Blakemore LC. Pelvic fractures in a pediatric level I trauma center. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16(7):458-463.

4. Ismail N, Bellemare JF, Mollitt DL, Di Scala C, Koeppel B, Tepas JJ. Death from pelvic fracture: children are different. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31(1):82-85.

5. Schlickwei W, Keck T. Pelvic and acetabular fractures in childhood. Injury. 2005;36(suppl 1):A57-A63.

6. Swiontkowski MF. Fractures and dislocations about the hip and pelvis. In: Green NE, Swiontkowski MF, eds. Skeletal Trauma in Children. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2003:371-406.

7. Silber JS, Flynn JM, Koffler KM, Dormans JP, Drummond DS. Analysis of the cause, classification, and associated injuries of 166 consecutive pediatric pelvic fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21(4):446-450.

8. Silber JS, Flynn JM. Changing patterns of pediatric pelvic fractures with skeletal maturation: implications for classification and management. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22(1):22-26.

9. Bucholz RW, Ezaki M, Ogden JA. Injury to the acetabular triradiate physeal cartilage. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64(4):600-609.

10. Heeg M, Klasen HJ, Visser JD. Acetabular fractures in children and adolescents. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989;71(3):418-421.

11. Heeg M, de Ridder VA, Tornetta P, de Lange S, Klasen HJ. Acetabular fractures in children and adolescents. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;(376):80-86.

12. Heeg M, Visser JD, Oostvogel HJ. Injuries of the acetabular triradiate cartilage and sacroiliac joint. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70(1):34-37.

13. Liporace FA, Ong B, Mohaideen A, Ong A, Koval KJ. Development and injury of the triradiate cartilage with its effects on acetabular development: review of the literature. J Trauma. 2003;54(6):1245-1249.

14. Rodrigues KF. Injury of the acetabular epiphysis. Injury. 1973;4(3):258-260.

15. Trousdale RT, Ganz R. Posttraumatic acetabular dysplasia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;(305):124-132.

16. Brooks E, Rosman M. Central fracture-dislocation of the hip in a child. J Trauma. 1988;28(11):1590-1592.

17. Habacker TA, Heinrich SD, Dehne R. Fracture of the superior pelvic quadrant in a child. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;15(1):69-72.

18. Karunakar MA, Goulet JA, Mueller KL, Bedi A, Le TT. Operative treatment of unstable pediatric pelvis and acetabular fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(1):34-38.

19. Rieger H, Brug E. Fractures of the pelvis in children. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;(336);226-239.

20. Torode I, Zieg D. Pelvic fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1985;5(1):76-84.

21. Letournel E, Judet R. Fractures of the Acetabulum. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1993.

22. Matta JM. Fractures of the acetabulum: accuracy of reduction and clinical results in patients managed operatively within three weeks of the injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(11):1632-1645.

1. Canale ST, Beaty JH. Fractures of the pelvis. In: Beaty JH, Kassler JR, eds. Rockwood and Wilkin’s Fractures in Children. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:883-991.

2. Demetriades D, Karaiskakis M, Velmahos GC, Alo K, Murray J, Chan L. Pelvic fractures in pediatric and adult trauma patients: are they different injuries? J Trauma. 2003;54(6):1146-1151.

3. Grisoni N, Connor S, Marsh E, Thompson GH, Cooperman DR, Blakemore LC. Pelvic fractures in a pediatric level I trauma center. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16(7):458-463.

4. Ismail N, Bellemare JF, Mollitt DL, Di Scala C, Koeppel B, Tepas JJ. Death from pelvic fracture: children are different. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31(1):82-85.

5. Schlickwei W, Keck T. Pelvic and acetabular fractures in childhood. Injury. 2005;36(suppl 1):A57-A63.

6. Swiontkowski MF. Fractures and dislocations about the hip and pelvis. In: Green NE, Swiontkowski MF, eds. Skeletal Trauma in Children. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2003:371-406.

7. Silber JS, Flynn JM, Koffler KM, Dormans JP, Drummond DS. Analysis of the cause, classification, and associated injuries of 166 consecutive pediatric pelvic fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21(4):446-450.

8. Silber JS, Flynn JM. Changing patterns of pediatric pelvic fractures with skeletal maturation: implications for classification and management. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22(1):22-26.

9. Bucholz RW, Ezaki M, Ogden JA. Injury to the acetabular triradiate physeal cartilage. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64(4):600-609.

10. Heeg M, Klasen HJ, Visser JD. Acetabular fractures in children and adolescents. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989;71(3):418-421.

11. Heeg M, de Ridder VA, Tornetta P, de Lange S, Klasen HJ. Acetabular fractures in children and adolescents. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;(376):80-86.

12. Heeg M, Visser JD, Oostvogel HJ. Injuries of the acetabular triradiate cartilage and sacroiliac joint. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70(1):34-37.

13. Liporace FA, Ong B, Mohaideen A, Ong A, Koval KJ. Development and injury of the triradiate cartilage with its effects on acetabular development: review of the literature. J Trauma. 2003;54(6):1245-1249.

14. Rodrigues KF. Injury of the acetabular epiphysis. Injury. 1973;4(3):258-260.

15. Trousdale RT, Ganz R. Posttraumatic acetabular dysplasia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;(305):124-132.

16. Brooks E, Rosman M. Central fracture-dislocation of the hip in a child. J Trauma. 1988;28(11):1590-1592.

17. Habacker TA, Heinrich SD, Dehne R. Fracture of the superior pelvic quadrant in a child. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;15(1):69-72.

18. Karunakar MA, Goulet JA, Mueller KL, Bedi A, Le TT. Operative treatment of unstable pediatric pelvis and acetabular fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25(1):34-38.

19. Rieger H, Brug E. Fractures of the pelvis in children. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;(336);226-239.

20. Torode I, Zieg D. Pelvic fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1985;5(1):76-84.

21. Letournel E, Judet R. Fractures of the Acetabulum. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1993.

22. Matta JM. Fractures of the acetabulum: accuracy of reduction and clinical results in patients managed operatively within three weeks of the injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(11):1632-1645.