User login

“To Conserve Fighting Strength”: The Role of Military Culture in the Delivery of Care

Since 2001, nearly 2,000 US military service members have sustained traumatically acquired limb loss while serving in conflict zones primarily in Afghanistan and Iraq.1 Although most of these patients receive acute and long-term care in a military health facility, polytrauma programs within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) treat other military patients with traumatic injuries while others receive specialized care in civilian medical programs. The Military Advanced Training Center (MATC) at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC) provides a comprehensive rehabilitation program for patients with acquired traumatic limb loss.2

In this paper, we argue that receiving long-term care in military settings provides unique value for military patients because of the background therapeutic work such settings can provide. Currently, there are policy discussions that center on consolidating military health care under the oversight of the Defense Health Agency. This approach would develop a more centralized administration while also pursuing other measures to improve efficiency. When evaluating the current system, one key question remains: Would military service members and dependents seeking specific care or long-term rehabilitation programs be more effectively treated in nonmilitary settings?

Based on qualitative research, we argue that keeping a diverse range of military health programs has a positive and therapeutic impact. We also argue that the emergent literature about the importance of military culture to patients and the need for military cultural competence training for nonmilitary clinicians coupled with the results of a qualitative study of former patients at WRNMMC demonstrate that the social context at military treatment facilities offers a positive therapeutic impact.3

Program Description

This article is grounded in research conducted in the US Armed Forces Amputee Patient Care Program at WRNMMC. The study received WRNMMC Institutional Review Board approval in February 2012 and again for the continuation study in January 2015. The lead investigator for the research project was a medical anthropologist who worked with a research unit in the WRNMMC Department of Rehabilitation.

The main period of data collection occurred in 2 waves, the first between 2012 and 2014 and the second between 2015 and 2019. Patients arrived at WRNMMC within several days from the site of their injuries (nearly all were from Iraq and Afghanistan) via military medical facilities in Germany. After a period of recovery from the acute phase of their injuries, patients transitioned to outpatient housing and began their longer phase of care in the outpatient MATC.

On MATC admission, patients were assigned an occupational therapist, physical therapist, and prosthetist. In addition, rehabilitation physicians and orthopedic surgeons oversaw patient care. Social work and other programs provided additional services as needed.2 Patients were treated primarily for their orthopedic and extremity trauma and for neuropsychiatric injuries, such as mild traumatic brain injury. Other behavioral health services were available to support patients who reported symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, or other neuropsychological issues.

Patients had multiple daily appointments that shifted throughout the duration of their care. Initially a patient might have 2 physical therapy and 2 occupational therapy appointments daily, with each session lasting about an hour. Appointments with the orthotics and prosthetics service, which could be considerably longer were added as needed. These appointments required multiple castings, fittings, adjustments, and other activities. This also was the case with wound care, behavioral health, and other services and departments.

Cultural Competency

A recently published special issue of Academic Psychiatry described the important role that basic knowledge of military culture plays in effective care delivery to active-duty service members, guard and reserve, and veteran patients and families.4 Reger and colleagues also emphasized the importance of awareness of military culture to civilian clinicians particularly those providing care to service members.5

This concern with gaps in knowledge about recognizing the realities of military culture has given rise to an emergent literature on military cultural competence training for clinical providers.6 Cultural competence in health care settings is understood to be the practice of providing care within a social framework that acknowledges the social and cultural background of patients.7 In the military context, as in others, these discussions often are limited to behavioral health settings.8 This emergent literature provides researchers with important insights into understanding the scope and scale of military culture and the importance of delivering culturally competent care.

Beyond the concept of cultural competence, recognizing the importance of culture can be used to understand positive therapeutic impacts. In discussions of culture, service-members, veterans, and family members are shown to have adopted a set of ideas, values, roles, and behaviors. Mastering an awareness of those attributes is part of the process of delivering culturally competent care. At WRNMMC and other military treatment facilities, those attributes are “baked in” to the delivery of service—even when that service is provided by civilians. How that process operates is important to understanding the impact of the organization of clinical care.

Methods

Data were extracted from research conducted between 2012 and 2014 that investigated how former patients evaluated their posttreatment lives considering the care received in the MATC at WRNMMC. We used a lightly structured set of interview questions and categories in each interview that focused on 3 themes in the individual’s pathway to injury: education, joining their branch of service, injury experience. The focus was on developing an understanding of how events antecedent to the injury experience could influence the rehabilitation experience and postcare life. The second focus was on the experience of rehabilitation and to learn how the individual navigated community living after leaving care.

Results

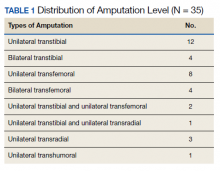

Thirty-five participants with lower extremity amputations were recruited who had been discharged from the Amputee Patient Care Program ≥ 12 months prior to the study (Table 1). Participants were interviewed either over the telephone, or when possible, in person. Interviews were based on a lightly structured schedule designed to elicit accounts of community integration, which attended to reports of belongingness supported by accounts of social engagement in work, school, family, and social events. Interviews were analyzed using a modified content analysis approach. The study did not rely on a structured interview, but as is the case with many qualitative and ethnographic interviews, each session shared themes in common, such as questions about injury experience, rehabilitation experience, life after care (work, school, relationships), and so forth. Interviews were conducted by the lead author who was a medical anthropologist with training in health services research.

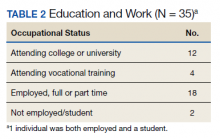

Participants generally described their post-care lives as “successful” that had been built on “good outcomes.” We left these concepts loosely defined to grant participants latitude in developing their own definitions for these ideas. That said, there is reason to view participants' lives as meeting specific criteria of success (Table 2). For example:

- 16 participants attended higher education postrehabilitation;

- 18 participants were working, or had worked, at the time of the interview;

- There was overlap between these groups and the total that had worked or attended school was 33 of 35; and

- 2 participants who had neither worked nor attended school were still recovering from injury complications at the time of the interview.

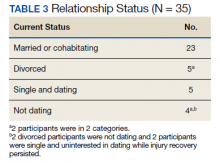

Family and relationships were other areas of success (Table 3). Twenty-three participants were currently in long-term relationships, including a mix of marriage and cohabitation households, while 3 were recently divorced and 2 were divorced for a longer term. Of the 5 participants who had been divorced, 3 were interested in pursuing new relationships. All 5 of these participants had children and were actively involved in their lives. Seven participants were not in relationships. Two participants did not have or seek relationships because of complications associated with their ongoing recovery.

Whether considering the claims of participants, or how the literature conceptualizes successful community living, the evidence of success is supported by the accounts of work, school, and relationships. The attribution of these successes, in part, to the MATC rehabilitation program is important to understand because of the implications that this has on program value. Three features of the program continually emerged in interviews: recovering alongside peers, routine access to the entire treatment team, and ongoing relationships with key health care providers (HCPs).

Working Alongside Peers

Peers are an important element in how former patients remember their time in the rehabilitation program at WRNMMC. One benefit of recovering alongside peers is that it changes patients’ experiences of time. Being with other military patients creates a transitional time that participants said they valued as they shifted from the immediacy of their deployment experiences to the longer term demands of recovery and community reintegration.9 Additionally, sharing the clinical space with patients who had come before allowed participants to visualize a living timeline of their proposed recovery.

For most former patients, remembering the social intensity of their rehabilitation program is an important element in their narratives of recovery. The participants in our study do not necessarily maintain ties with their former peers, but nearly all of them point to support from other patients as being key in their own recovery from both the physical and psychological consequences of their injury.

Routine Access to the Treatment Team

The weekly amputee clinics that put surgeons, physicians, occupational and physical therapists, social workers, and prosthetists in a room with each patient worked to alleviate stress and anxiety in participants’ minds around the complexities of their injuries and care. One of the benefits of a group meeting is that it reduces the risk of miscommunication among HCPs and between HCPs and patients.7,10

These weekly sessions with HCPs and patients led to a second advantage; they promoted patient autonomy and participation in clinical decisions. Patients were able to negotiate clinical goals with their HCPs and then act on them almost immediately. In addition, patients with complex physical injuries, often with neurological or psychiatric comorbidities, were able to describe the full range of their challenges, and HCPs had an opportunity to check in with patients about the problems they faced and level of severity.

The ability to marshal clinical HCPs to attend weekly meetings of this nature with patients may be key for distinguishing military health care from VHA and civilian counterparts. More research on how clinical team/ patient meetings occur in other settings is needed. But one of the hallmark features of these clinic meetings at WRNMMC was their open-endedness. Patients typically were not bound by 15 minute or other temporally delimited meeting intervals. This research indicates that in military health care, the patient is the leader.

Continuity of Care

Continuity of care is a well-understood benefit to working with the same HCP. There were additional unanticipated benefits to assigning patients to HCPs with whom they had worked. The long-term period of care (5-24 months) gave patients the opportunity to develop multifaceted relationships with their HCPs and empowered them to advocate and negotiate for their outcome goals. In addition, the majority of frontline HCPs in physical and occupational therapy were civil ians (all prosthetic providers were civilians). These ongoing relationships had the impact of socializing clinicians into the expectations of military culture (around physical training, endurance and resilience, and disregard of pain).

Physical and occupational therapists occupied multiple roles for their patients, including being teachers, coaches, and sounding boards. Participants frequently described the way that their physical or occupational therapist could, on one hand, push them to achieve more in terms of physical functioning. But on the other hand, participants also talked about the emotional and psychological support they could receive based both on the long duration of their work with their care providers.

Conclusions

The ability to recover alongside peers, have access to the whole treatment team and develop long-term relationships with key care HCPs served as drivers for positive recovery. The impact of these 3 drivers of the social organization of the Amputee Patient Care Program represent an opportunity to highlight the role that the social context of military health care to use in achieving positive therapeutic outcomes. Former patients of the WRNMMC program could rely on a familiar and dependable social context for their care. This social context draws heavily on elements of military culture that structure the preinjury worlds of work and life that patients occupied. Based on these results we argue that the presence of rehabilitation and other clinical units in military medical settings offers an important value to patients and HCPs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Center for Rehabilitation Science Research, Department of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, MD (awards HU0001-11-1-0004 and HU0001-15-2-0003).

1. Grimm PD, Mauntel TC, Potter BK. Combat and noncombat musculoskeletal injuries in the US military. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2019;27(3):84-91. doi:10.1097/JSA.0000000000000246

2. Gajewski D, Granville R. The United States Armed Forces Amputee Patient Care Program. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(10 Spec No.):S183-S187. doi:10.5435/00124635-200600001-00040

3. Messinger S, Bozorghadad S, Pasquina P. Social relationships in rehabilitation and their impact on positive outcomes among amputees with lower limb loss at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. J Rehabil Med. 2018;50(1):86-93. doi:10.2340/16501977-2274

4. Meyer EG. The importance of understanding military culture. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(4):416-418. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0285-1

5. Reger MA, Etherage JR, Reger GM, Gahm GA. Civilian psychologists in an army culture: the ethical challenge of cultural competence. Mil Psychol. 2008;20(1):21-35. doi:10.1080/08995600701753144

6. Convoy S, Westphal RJ. The importance of developing military cultural competence. J Emerg Nurs. 2013;39(6):591-594. doi:10.1016/j.jen.2013.08.010

7. Campinha-Bacote J. The process of cultural competence in the delivery of healthcare services: a model of care. J Transcult Nurs. 2002;13(3):181-201. doi:10.1177/10459602013003003

8. Meyer EG, Hall-Clark BN, Hamaoka D, Peterson AL. Assessment of military cultural competence: a pilot study. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(4):382-388. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0328-7

9. Messinger SD. Rehabilitating time: multiple temporalities among military clinicians and patients. Med Anthropol. 2010;29(2):150-169. doi:10.1080/01459741003715383

10. Williams MV, Davis T, Parker RM, Weiss BD. The role of health literacy in patient-physician communication. Fam Med. 2002;34(5):383-389.

Since 2001, nearly 2,000 US military service members have sustained traumatically acquired limb loss while serving in conflict zones primarily in Afghanistan and Iraq.1 Although most of these patients receive acute and long-term care in a military health facility, polytrauma programs within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) treat other military patients with traumatic injuries while others receive specialized care in civilian medical programs. The Military Advanced Training Center (MATC) at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC) provides a comprehensive rehabilitation program for patients with acquired traumatic limb loss.2

In this paper, we argue that receiving long-term care in military settings provides unique value for military patients because of the background therapeutic work such settings can provide. Currently, there are policy discussions that center on consolidating military health care under the oversight of the Defense Health Agency. This approach would develop a more centralized administration while also pursuing other measures to improve efficiency. When evaluating the current system, one key question remains: Would military service members and dependents seeking specific care or long-term rehabilitation programs be more effectively treated in nonmilitary settings?

Based on qualitative research, we argue that keeping a diverse range of military health programs has a positive and therapeutic impact. We also argue that the emergent literature about the importance of military culture to patients and the need for military cultural competence training for nonmilitary clinicians coupled with the results of a qualitative study of former patients at WRNMMC demonstrate that the social context at military treatment facilities offers a positive therapeutic impact.3

Program Description

This article is grounded in research conducted in the US Armed Forces Amputee Patient Care Program at WRNMMC. The study received WRNMMC Institutional Review Board approval in February 2012 and again for the continuation study in January 2015. The lead investigator for the research project was a medical anthropologist who worked with a research unit in the WRNMMC Department of Rehabilitation.

The main period of data collection occurred in 2 waves, the first between 2012 and 2014 and the second between 2015 and 2019. Patients arrived at WRNMMC within several days from the site of their injuries (nearly all were from Iraq and Afghanistan) via military medical facilities in Germany. After a period of recovery from the acute phase of their injuries, patients transitioned to outpatient housing and began their longer phase of care in the outpatient MATC.

On MATC admission, patients were assigned an occupational therapist, physical therapist, and prosthetist. In addition, rehabilitation physicians and orthopedic surgeons oversaw patient care. Social work and other programs provided additional services as needed.2 Patients were treated primarily for their orthopedic and extremity trauma and for neuropsychiatric injuries, such as mild traumatic brain injury. Other behavioral health services were available to support patients who reported symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, or other neuropsychological issues.

Patients had multiple daily appointments that shifted throughout the duration of their care. Initially a patient might have 2 physical therapy and 2 occupational therapy appointments daily, with each session lasting about an hour. Appointments with the orthotics and prosthetics service, which could be considerably longer were added as needed. These appointments required multiple castings, fittings, adjustments, and other activities. This also was the case with wound care, behavioral health, and other services and departments.

Cultural Competency

A recently published special issue of Academic Psychiatry described the important role that basic knowledge of military culture plays in effective care delivery to active-duty service members, guard and reserve, and veteran patients and families.4 Reger and colleagues also emphasized the importance of awareness of military culture to civilian clinicians particularly those providing care to service members.5

This concern with gaps in knowledge about recognizing the realities of military culture has given rise to an emergent literature on military cultural competence training for clinical providers.6 Cultural competence in health care settings is understood to be the practice of providing care within a social framework that acknowledges the social and cultural background of patients.7 In the military context, as in others, these discussions often are limited to behavioral health settings.8 This emergent literature provides researchers with important insights into understanding the scope and scale of military culture and the importance of delivering culturally competent care.

Beyond the concept of cultural competence, recognizing the importance of culture can be used to understand positive therapeutic impacts. In discussions of culture, service-members, veterans, and family members are shown to have adopted a set of ideas, values, roles, and behaviors. Mastering an awareness of those attributes is part of the process of delivering culturally competent care. At WRNMMC and other military treatment facilities, those attributes are “baked in” to the delivery of service—even when that service is provided by civilians. How that process operates is important to understanding the impact of the organization of clinical care.

Methods

Data were extracted from research conducted between 2012 and 2014 that investigated how former patients evaluated their posttreatment lives considering the care received in the MATC at WRNMMC. We used a lightly structured set of interview questions and categories in each interview that focused on 3 themes in the individual’s pathway to injury: education, joining their branch of service, injury experience. The focus was on developing an understanding of how events antecedent to the injury experience could influence the rehabilitation experience and postcare life. The second focus was on the experience of rehabilitation and to learn how the individual navigated community living after leaving care.

Results

Thirty-five participants with lower extremity amputations were recruited who had been discharged from the Amputee Patient Care Program ≥ 12 months prior to the study (Table 1). Participants were interviewed either over the telephone, or when possible, in person. Interviews were based on a lightly structured schedule designed to elicit accounts of community integration, which attended to reports of belongingness supported by accounts of social engagement in work, school, family, and social events. Interviews were analyzed using a modified content analysis approach. The study did not rely on a structured interview, but as is the case with many qualitative and ethnographic interviews, each session shared themes in common, such as questions about injury experience, rehabilitation experience, life after care (work, school, relationships), and so forth. Interviews were conducted by the lead author who was a medical anthropologist with training in health services research.

Participants generally described their post-care lives as “successful” that had been built on “good outcomes.” We left these concepts loosely defined to grant participants latitude in developing their own definitions for these ideas. That said, there is reason to view participants' lives as meeting specific criteria of success (Table 2). For example:

- 16 participants attended higher education postrehabilitation;

- 18 participants were working, or had worked, at the time of the interview;

- There was overlap between these groups and the total that had worked or attended school was 33 of 35; and

- 2 participants who had neither worked nor attended school were still recovering from injury complications at the time of the interview.

Family and relationships were other areas of success (Table 3). Twenty-three participants were currently in long-term relationships, including a mix of marriage and cohabitation households, while 3 were recently divorced and 2 were divorced for a longer term. Of the 5 participants who had been divorced, 3 were interested in pursuing new relationships. All 5 of these participants had children and were actively involved in their lives. Seven participants were not in relationships. Two participants did not have or seek relationships because of complications associated with their ongoing recovery.

Whether considering the claims of participants, or how the literature conceptualizes successful community living, the evidence of success is supported by the accounts of work, school, and relationships. The attribution of these successes, in part, to the MATC rehabilitation program is important to understand because of the implications that this has on program value. Three features of the program continually emerged in interviews: recovering alongside peers, routine access to the entire treatment team, and ongoing relationships with key health care providers (HCPs).

Working Alongside Peers

Peers are an important element in how former patients remember their time in the rehabilitation program at WRNMMC. One benefit of recovering alongside peers is that it changes patients’ experiences of time. Being with other military patients creates a transitional time that participants said they valued as they shifted from the immediacy of their deployment experiences to the longer term demands of recovery and community reintegration.9 Additionally, sharing the clinical space with patients who had come before allowed participants to visualize a living timeline of their proposed recovery.

For most former patients, remembering the social intensity of their rehabilitation program is an important element in their narratives of recovery. The participants in our study do not necessarily maintain ties with their former peers, but nearly all of them point to support from other patients as being key in their own recovery from both the physical and psychological consequences of their injury.

Routine Access to the Treatment Team

The weekly amputee clinics that put surgeons, physicians, occupational and physical therapists, social workers, and prosthetists in a room with each patient worked to alleviate stress and anxiety in participants’ minds around the complexities of their injuries and care. One of the benefits of a group meeting is that it reduces the risk of miscommunication among HCPs and between HCPs and patients.7,10

These weekly sessions with HCPs and patients led to a second advantage; they promoted patient autonomy and participation in clinical decisions. Patients were able to negotiate clinical goals with their HCPs and then act on them almost immediately. In addition, patients with complex physical injuries, often with neurological or psychiatric comorbidities, were able to describe the full range of their challenges, and HCPs had an opportunity to check in with patients about the problems they faced and level of severity.

The ability to marshal clinical HCPs to attend weekly meetings of this nature with patients may be key for distinguishing military health care from VHA and civilian counterparts. More research on how clinical team/ patient meetings occur in other settings is needed. But one of the hallmark features of these clinic meetings at WRNMMC was their open-endedness. Patients typically were not bound by 15 minute or other temporally delimited meeting intervals. This research indicates that in military health care, the patient is the leader.

Continuity of Care

Continuity of care is a well-understood benefit to working with the same HCP. There were additional unanticipated benefits to assigning patients to HCPs with whom they had worked. The long-term period of care (5-24 months) gave patients the opportunity to develop multifaceted relationships with their HCPs and empowered them to advocate and negotiate for their outcome goals. In addition, the majority of frontline HCPs in physical and occupational therapy were civil ians (all prosthetic providers were civilians). These ongoing relationships had the impact of socializing clinicians into the expectations of military culture (around physical training, endurance and resilience, and disregard of pain).

Physical and occupational therapists occupied multiple roles for their patients, including being teachers, coaches, and sounding boards. Participants frequently described the way that their physical or occupational therapist could, on one hand, push them to achieve more in terms of physical functioning. But on the other hand, participants also talked about the emotional and psychological support they could receive based both on the long duration of their work with their care providers.

Conclusions

The ability to recover alongside peers, have access to the whole treatment team and develop long-term relationships with key care HCPs served as drivers for positive recovery. The impact of these 3 drivers of the social organization of the Amputee Patient Care Program represent an opportunity to highlight the role that the social context of military health care to use in achieving positive therapeutic outcomes. Former patients of the WRNMMC program could rely on a familiar and dependable social context for their care. This social context draws heavily on elements of military culture that structure the preinjury worlds of work and life that patients occupied. Based on these results we argue that the presence of rehabilitation and other clinical units in military medical settings offers an important value to patients and HCPs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Center for Rehabilitation Science Research, Department of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, MD (awards HU0001-11-1-0004 and HU0001-15-2-0003).

Since 2001, nearly 2,000 US military service members have sustained traumatically acquired limb loss while serving in conflict zones primarily in Afghanistan and Iraq.1 Although most of these patients receive acute and long-term care in a military health facility, polytrauma programs within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) treat other military patients with traumatic injuries while others receive specialized care in civilian medical programs. The Military Advanced Training Center (MATC) at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC) provides a comprehensive rehabilitation program for patients with acquired traumatic limb loss.2

In this paper, we argue that receiving long-term care in military settings provides unique value for military patients because of the background therapeutic work such settings can provide. Currently, there are policy discussions that center on consolidating military health care under the oversight of the Defense Health Agency. This approach would develop a more centralized administration while also pursuing other measures to improve efficiency. When evaluating the current system, one key question remains: Would military service members and dependents seeking specific care or long-term rehabilitation programs be more effectively treated in nonmilitary settings?

Based on qualitative research, we argue that keeping a diverse range of military health programs has a positive and therapeutic impact. We also argue that the emergent literature about the importance of military culture to patients and the need for military cultural competence training for nonmilitary clinicians coupled with the results of a qualitative study of former patients at WRNMMC demonstrate that the social context at military treatment facilities offers a positive therapeutic impact.3

Program Description

This article is grounded in research conducted in the US Armed Forces Amputee Patient Care Program at WRNMMC. The study received WRNMMC Institutional Review Board approval in February 2012 and again for the continuation study in January 2015. The lead investigator for the research project was a medical anthropologist who worked with a research unit in the WRNMMC Department of Rehabilitation.

The main period of data collection occurred in 2 waves, the first between 2012 and 2014 and the second between 2015 and 2019. Patients arrived at WRNMMC within several days from the site of their injuries (nearly all were from Iraq and Afghanistan) via military medical facilities in Germany. After a period of recovery from the acute phase of their injuries, patients transitioned to outpatient housing and began their longer phase of care in the outpatient MATC.

On MATC admission, patients were assigned an occupational therapist, physical therapist, and prosthetist. In addition, rehabilitation physicians and orthopedic surgeons oversaw patient care. Social work and other programs provided additional services as needed.2 Patients were treated primarily for their orthopedic and extremity trauma and for neuropsychiatric injuries, such as mild traumatic brain injury. Other behavioral health services were available to support patients who reported symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, or other neuropsychological issues.

Patients had multiple daily appointments that shifted throughout the duration of their care. Initially a patient might have 2 physical therapy and 2 occupational therapy appointments daily, with each session lasting about an hour. Appointments with the orthotics and prosthetics service, which could be considerably longer were added as needed. These appointments required multiple castings, fittings, adjustments, and other activities. This also was the case with wound care, behavioral health, and other services and departments.

Cultural Competency

A recently published special issue of Academic Psychiatry described the important role that basic knowledge of military culture plays in effective care delivery to active-duty service members, guard and reserve, and veteran patients and families.4 Reger and colleagues also emphasized the importance of awareness of military culture to civilian clinicians particularly those providing care to service members.5

This concern with gaps in knowledge about recognizing the realities of military culture has given rise to an emergent literature on military cultural competence training for clinical providers.6 Cultural competence in health care settings is understood to be the practice of providing care within a social framework that acknowledges the social and cultural background of patients.7 In the military context, as in others, these discussions often are limited to behavioral health settings.8 This emergent literature provides researchers with important insights into understanding the scope and scale of military culture and the importance of delivering culturally competent care.

Beyond the concept of cultural competence, recognizing the importance of culture can be used to understand positive therapeutic impacts. In discussions of culture, service-members, veterans, and family members are shown to have adopted a set of ideas, values, roles, and behaviors. Mastering an awareness of those attributes is part of the process of delivering culturally competent care. At WRNMMC and other military treatment facilities, those attributes are “baked in” to the delivery of service—even when that service is provided by civilians. How that process operates is important to understanding the impact of the organization of clinical care.

Methods

Data were extracted from research conducted between 2012 and 2014 that investigated how former patients evaluated their posttreatment lives considering the care received in the MATC at WRNMMC. We used a lightly structured set of interview questions and categories in each interview that focused on 3 themes in the individual’s pathway to injury: education, joining their branch of service, injury experience. The focus was on developing an understanding of how events antecedent to the injury experience could influence the rehabilitation experience and postcare life. The second focus was on the experience of rehabilitation and to learn how the individual navigated community living after leaving care.

Results

Thirty-five participants with lower extremity amputations were recruited who had been discharged from the Amputee Patient Care Program ≥ 12 months prior to the study (Table 1). Participants were interviewed either over the telephone, or when possible, in person. Interviews were based on a lightly structured schedule designed to elicit accounts of community integration, which attended to reports of belongingness supported by accounts of social engagement in work, school, family, and social events. Interviews were analyzed using a modified content analysis approach. The study did not rely on a structured interview, but as is the case with many qualitative and ethnographic interviews, each session shared themes in common, such as questions about injury experience, rehabilitation experience, life after care (work, school, relationships), and so forth. Interviews were conducted by the lead author who was a medical anthropologist with training in health services research.

Participants generally described their post-care lives as “successful” that had been built on “good outcomes.” We left these concepts loosely defined to grant participants latitude in developing their own definitions for these ideas. That said, there is reason to view participants' lives as meeting specific criteria of success (Table 2). For example:

- 16 participants attended higher education postrehabilitation;

- 18 participants were working, or had worked, at the time of the interview;

- There was overlap between these groups and the total that had worked or attended school was 33 of 35; and

- 2 participants who had neither worked nor attended school were still recovering from injury complications at the time of the interview.

Family and relationships were other areas of success (Table 3). Twenty-three participants were currently in long-term relationships, including a mix of marriage and cohabitation households, while 3 were recently divorced and 2 were divorced for a longer term. Of the 5 participants who had been divorced, 3 were interested in pursuing new relationships. All 5 of these participants had children and were actively involved in their lives. Seven participants were not in relationships. Two participants did not have or seek relationships because of complications associated with their ongoing recovery.

Whether considering the claims of participants, or how the literature conceptualizes successful community living, the evidence of success is supported by the accounts of work, school, and relationships. The attribution of these successes, in part, to the MATC rehabilitation program is important to understand because of the implications that this has on program value. Three features of the program continually emerged in interviews: recovering alongside peers, routine access to the entire treatment team, and ongoing relationships with key health care providers (HCPs).

Working Alongside Peers

Peers are an important element in how former patients remember their time in the rehabilitation program at WRNMMC. One benefit of recovering alongside peers is that it changes patients’ experiences of time. Being with other military patients creates a transitional time that participants said they valued as they shifted from the immediacy of their deployment experiences to the longer term demands of recovery and community reintegration.9 Additionally, sharing the clinical space with patients who had come before allowed participants to visualize a living timeline of their proposed recovery.

For most former patients, remembering the social intensity of their rehabilitation program is an important element in their narratives of recovery. The participants in our study do not necessarily maintain ties with their former peers, but nearly all of them point to support from other patients as being key in their own recovery from both the physical and psychological consequences of their injury.

Routine Access to the Treatment Team

The weekly amputee clinics that put surgeons, physicians, occupational and physical therapists, social workers, and prosthetists in a room with each patient worked to alleviate stress and anxiety in participants’ minds around the complexities of their injuries and care. One of the benefits of a group meeting is that it reduces the risk of miscommunication among HCPs and between HCPs and patients.7,10

These weekly sessions with HCPs and patients led to a second advantage; they promoted patient autonomy and participation in clinical decisions. Patients were able to negotiate clinical goals with their HCPs and then act on them almost immediately. In addition, patients with complex physical injuries, often with neurological or psychiatric comorbidities, were able to describe the full range of their challenges, and HCPs had an opportunity to check in with patients about the problems they faced and level of severity.

The ability to marshal clinical HCPs to attend weekly meetings of this nature with patients may be key for distinguishing military health care from VHA and civilian counterparts. More research on how clinical team/ patient meetings occur in other settings is needed. But one of the hallmark features of these clinic meetings at WRNMMC was their open-endedness. Patients typically were not bound by 15 minute or other temporally delimited meeting intervals. This research indicates that in military health care, the patient is the leader.

Continuity of Care

Continuity of care is a well-understood benefit to working with the same HCP. There were additional unanticipated benefits to assigning patients to HCPs with whom they had worked. The long-term period of care (5-24 months) gave patients the opportunity to develop multifaceted relationships with their HCPs and empowered them to advocate and negotiate for their outcome goals. In addition, the majority of frontline HCPs in physical and occupational therapy were civil ians (all prosthetic providers were civilians). These ongoing relationships had the impact of socializing clinicians into the expectations of military culture (around physical training, endurance and resilience, and disregard of pain).

Physical and occupational therapists occupied multiple roles for their patients, including being teachers, coaches, and sounding boards. Participants frequently described the way that their physical or occupational therapist could, on one hand, push them to achieve more in terms of physical functioning. But on the other hand, participants also talked about the emotional and psychological support they could receive based both on the long duration of their work with their care providers.

Conclusions

The ability to recover alongside peers, have access to the whole treatment team and develop long-term relationships with key care HCPs served as drivers for positive recovery. The impact of these 3 drivers of the social organization of the Amputee Patient Care Program represent an opportunity to highlight the role that the social context of military health care to use in achieving positive therapeutic outcomes. Former patients of the WRNMMC program could rely on a familiar and dependable social context for their care. This social context draws heavily on elements of military culture that structure the preinjury worlds of work and life that patients occupied. Based on these results we argue that the presence of rehabilitation and other clinical units in military medical settings offers an important value to patients and HCPs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Center for Rehabilitation Science Research, Department of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, MD (awards HU0001-11-1-0004 and HU0001-15-2-0003).

1. Grimm PD, Mauntel TC, Potter BK. Combat and noncombat musculoskeletal injuries in the US military. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2019;27(3):84-91. doi:10.1097/JSA.0000000000000246

2. Gajewski D, Granville R. The United States Armed Forces Amputee Patient Care Program. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(10 Spec No.):S183-S187. doi:10.5435/00124635-200600001-00040

3. Messinger S, Bozorghadad S, Pasquina P. Social relationships in rehabilitation and their impact on positive outcomes among amputees with lower limb loss at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. J Rehabil Med. 2018;50(1):86-93. doi:10.2340/16501977-2274

4. Meyer EG. The importance of understanding military culture. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(4):416-418. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0285-1

5. Reger MA, Etherage JR, Reger GM, Gahm GA. Civilian psychologists in an army culture: the ethical challenge of cultural competence. Mil Psychol. 2008;20(1):21-35. doi:10.1080/08995600701753144

6. Convoy S, Westphal RJ. The importance of developing military cultural competence. J Emerg Nurs. 2013;39(6):591-594. doi:10.1016/j.jen.2013.08.010

7. Campinha-Bacote J. The process of cultural competence in the delivery of healthcare services: a model of care. J Transcult Nurs. 2002;13(3):181-201. doi:10.1177/10459602013003003

8. Meyer EG, Hall-Clark BN, Hamaoka D, Peterson AL. Assessment of military cultural competence: a pilot study. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(4):382-388. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0328-7

9. Messinger SD. Rehabilitating time: multiple temporalities among military clinicians and patients. Med Anthropol. 2010;29(2):150-169. doi:10.1080/01459741003715383

10. Williams MV, Davis T, Parker RM, Weiss BD. The role of health literacy in patient-physician communication. Fam Med. 2002;34(5):383-389.

1. Grimm PD, Mauntel TC, Potter BK. Combat and noncombat musculoskeletal injuries in the US military. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2019;27(3):84-91. doi:10.1097/JSA.0000000000000246

2. Gajewski D, Granville R. The United States Armed Forces Amputee Patient Care Program. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14(10 Spec No.):S183-S187. doi:10.5435/00124635-200600001-00040

3. Messinger S, Bozorghadad S, Pasquina P. Social relationships in rehabilitation and their impact on positive outcomes among amputees with lower limb loss at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. J Rehabil Med. 2018;50(1):86-93. doi:10.2340/16501977-2274

4. Meyer EG. The importance of understanding military culture. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(4):416-418. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0285-1

5. Reger MA, Etherage JR, Reger GM, Gahm GA. Civilian psychologists in an army culture: the ethical challenge of cultural competence. Mil Psychol. 2008;20(1):21-35. doi:10.1080/08995600701753144

6. Convoy S, Westphal RJ. The importance of developing military cultural competence. J Emerg Nurs. 2013;39(6):591-594. doi:10.1016/j.jen.2013.08.010

7. Campinha-Bacote J. The process of cultural competence in the delivery of healthcare services: a model of care. J Transcult Nurs. 2002;13(3):181-201. doi:10.1177/10459602013003003

8. Meyer EG, Hall-Clark BN, Hamaoka D, Peterson AL. Assessment of military cultural competence: a pilot study. Acad Psychiatry. 2015;39(4):382-388. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0328-7

9. Messinger SD. Rehabilitating time: multiple temporalities among military clinicians and patients. Med Anthropol. 2010;29(2):150-169. doi:10.1080/01459741003715383

10. Williams MV, Davis T, Parker RM, Weiss BD. The role of health literacy in patient-physician communication. Fam Med. 2002;34(5):383-389.