User login

A Practical Approach for Primary Care Practitioners to Evaluate and Manage Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS)are common and tend to increase in frequency with age. Managing LUTS can be complicated, requires an informed discussion between the primary care practitioner (PCP) and patient, and is best achieved by a thorough understanding of the many medical and surgical options available. Over the past 3 decades, medications have become the most common therapy; but recently, newer minimally invasive surgeries have challenged this paradigm. This article provides a comprehensive review for PCPs regarding the evaluation and management of LUTS in men and when to consider a urology referral.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and LUTS are common clinical encounters for most PCPs. About 50% of men will develop LUTS associated with BPH, and symptoms associated with these conditions increase as men age.1,2 Studies have estimated that 90% of men aged 45 to 80 years demonstrate some symptoms of LUTS.3 Strong genetic influence seems to suggest heritability, but BPH also occurs in sporadic forms and is heavily influenced by androgens.4

BPH is a histologic diagnosis, whereas LUTS consists of complex symptomatology related to both static or dynamic components.1 The enlarged prostate gland obstructs the urethra, simultaneously causing an increase in muscle tone and resistance at the bladder neck and prostatic urethra, leading to increased resistance to urine flow. As a result, there is a thickening of the detrusor muscles in the bladder wall and an overall decreased compliance. Urine becomes stored under increased pressure. These changes result in a weak or intermittent urine stream, incomplete emptying of the bladder, postvoid dribble, hesitancy, and irritative symptoms, such as urgency, frequency, and nocturia.

For many patients, BPH associated with LUTS is a quality of life (QOL) issue. The stigma associated with these symptoms often leads to delays in patients seeking care. Many patients do not seek treatment until symptoms have become so severe that changes in bladder health are often irreversible. Early intervention can dramatically improve a patient’s QOL. Also, early intervention has the potential to reduce overall health care expenditures. BPH-related spending exceeds $1 billion each year in the Medicare program alone.5

PCPs are in a unique position to help many patients who present with early-stage LUTS. Given the substantial impact this disease has on QOL, early recognition of symptoms and prompt treatment play a major role. Paramount to this effort is awareness and understanding of various treatments, their advantages, and adverse effects (AEs). This article highlights evidence-based evaluation and treatment of BPH/LUTS for PCPs who treat veterans and recommendations as to when to refer a patient to a urologist.

Evaluation of LUTS and BPH

Evaluation begins with a thorough medical history and physical examination. Particular attention should focus on ruling out other causes of LUTS, such as a urinary tract infection (UTI), acute prostatitis, malignancy, bladder dysfunction, neurogenic bladder, and other obstructive pathology, such as urethral stricture disease. The differential diagnosis of LUTS includes BPH, UTI, bladder neck obstruction, urethral stricture, bladder stones, polydipsia, overactive bladder (OAB), nocturnal polyuria, neurologic disease, genitourinary malignancy, renal failure, and acute/chronic urinary retention.6

Relevant medical history influencing urinary symptoms includes diabetes mellitus, underlying neurologic diseases, previous trauma, sexually transmitted infections, and certain medications. Symptom severity may be obtained using a validated questionnaire, such as the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), which also aids clinicians in assessing the impact of LUTS on QOL. Additionally, urinary frequency or volume records (voiding diary) may help establish the severity of the patient’s symptoms and provide insight into other potential causes for LUTS. Patients with BPH often have concurrent erectile dysfunction (ED) or other sexual dysfunction symptoms. Patients should be evaluated for baseline sexual dysfunction before the initiation of treatment as many therapies worsen symptoms of ED or ejaculatory dysfunction.

A comprehensive physical examination with a focus on the genitourinary system should, at minimum, assess for abnormalities of the urethral meatus, prepuce, penis, groin nodes, and prior surgical scars. A digital rectal examination also should be performed. Although controversial, a digital rectal examination for prostate cancer screening may provide a rough estimate of prostate size, help rule out prostatitis, and detect incident prostate nodules. Prostate size does not necessarily correlate well with the degree of urinary obstruction or LUTS but is an important consideration when deciding among different therapies.1

Laboratory and Adjunctive Tests

A urinalysis with microscopy helps identify other potential causes for urinary symptoms, including infection, proteinuria, or glucosuria. In patients who present with gross or microscopic hematuria, additional consideration should be given to bladder calculi and genitourinary cancer.2 When a reversible source for the hematuria is not identified, these patients require referral to a urologist for a hematuria evaluation.

There is some controversy regarding prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing. Most professional organizations advocate for a shared decision-making approach before testing. The American Cancer Society recommends this informed discussion occur between the patient and the PCP for men aged > 50 years at average risk, men aged > 45 years at high risk of developing prostate cancer (African Americans or first-degree relative with early prostate cancer diagnosis), and aged 40 years for men with more than one first-degree relative with an early prostate cancer diagnosis.7

Adjunctive tests include postvoid residual (PVR), cystoscopy, uroflowmetry, urodynamics, and transrectal ultrasound. However, these are mostly performed by urologists. In some patients with bladder decompensation after prolonged partial bladder outlet obstruction, urodynamics may be used by urologists to determine whether a patient may benefit from an outlet obstruction procedure. Ordering additional imaging or serum studies for the assessment of LUTS is rarely helpful.

Treatment

Treatment includes management with or without lifestyle modification, medication administration, and surgical therapy. New to this paradigm are in-office minimally invasive surgical options. The goal of treatment is not only to reduce patient symptoms and improve QOL, but also to prevent the secondary sequala of urinary retention, bladder failure, and eventual renal impairment.7A basic understanding of these treatments can aid PCPs with appropriate patient counseling and urologic referral.8

Lifestyle and Behavior Modification

Behavior modification is the starting point for all patients with LUTS. Lifestyle modifications for LUTS include avoiding substances that exacerbate symptoms, such as α-agonists (decongestants), caffeine, alcohol, spicy/acidic foods, chocolate, and soda. These substances are known to be bladder irritants. Common medications contributing to LUTS include antidepressants, decongestants, antihistamines, bronchodilators, anticholinergics, and sympathomimetics. To decrease nocturia, behavioral modifications include limiting evening fluid intake, timed diuretic administration for patients already on a diuretic, and elevating legs 1 hour before bedtime. Counseling obese patients to lose weight and increasing physical activity have been linked to reduced LUTS.9 Other behavioral techniques include double voiding: a technique where patients void normally then change positions and return to void to empty the bladder. Another technique is timed voiding: Many patients have impaired sensation when the bladder is full. These patients are encouraged to void at regular intervals.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Multiple nutraceutical compounds claim improved urinary health and symptom reduction. These compounds are marketed to patients with little regulation and oversight since supplements are not regulated or held to the same standard as prescription medications. The most popular nutraceutical for prostate health and LUTS is saw palmetto. Despite its common usage for the treatment of LUTS, little data support saw palmetto health claims. In 2012, a systematic review of 32 randomized trials including 5666 patients compared saw palmetto with a placebo. The study found no difference in urinary symptom scores, urinary flow, or prostate size.10,11 Other phytotherapy compounds often considered for urinary symptoms include stinging nettle extract and β-sitosterol compounds. The mechanism of action of these agents is unknown and efficacy data are lacking.

Historically, acupuncture and pelvic floor physical therapy have been used successfully for OAB symptoms. A meta-analysis found positive beneficial effects of acupuncture compared with a sham control for short- and medium-term follow-up in both IPSS and urine flow rates in some studies; however, when combining the studies for more statistical power, the benefits were less clear.12 Physical therapists with specialized training and certification in pelvic health can incorporate certain bladder training techniques. These include voiding positional changes (double voiding and postvoid urethral milking) and timed voiding.13,14 These interventions often address etiologies of LUTS for which medical therapies are not effective as the sole treatment option.

Medication Management

Medical management includes α-blockers, 5-α-reductase inhibitors (5-α-RIs), antimuscarinic or anticholinergic medicines, β-3 agonists, and phosphodiesterase inhibitors (Table). These medications work independently as well as synergistically. The use of medications to improve symptoms must be balanced against potential AEs and the consequences of a lifetime of drug usage, which can be additive.15,16

First-line pharmacological therapy for BPH is α-blockers, which work by blocking α1A receptors in the prostate and bladder neck, leading to smooth muscle relaxation, increased diameter of the channel, and improved urinary flow. α-receptors in the bladder neck and prostate are expressed with increased frequency with age and are a potential cause for worsening symptoms as men age. Studies demonstrate that these medications reduce symptoms by 30 to 40% and increase flow rates by 16 to 25%.17 Commonly prescribed α-blockers include tamsulosin, alfuzosin, silodosin, doxazosin, and terazosin. Doxazosin and terazosin require dose titrations because they may cause significant hypotension. Orthostatic hypotension typically improves with time and is avoided if the patient takes the medication at bedtime. Both doxazosin and terazosin are on the American Geriatric Society’s Beers Criteria list and should be avoided in older patients.18 Tamsulosin, alfuzosin, and silodosin have a standardized dosing regimen and lower rates of hypotension. Significant AEs include ejaculation dysfunction, nasal congestion, and orthostatic hypotension. Duan and colleagues have linked tamsulosin with dementia. However, this association is not causal and further studies are necessary.19,20 Patients who have taken these agents also are at risk for intraoperative floppy iris syndrome (IFIS). Permanent visual problems can arise if the intraoperative management is not managed to account for IFIS. These medications have a rapid onset of action and work immediately. However, to reach maximum benefit, patients must take the medication for several weeks. Unfortunately, up to one-third of patients will have no improvement with α-blocker therapy, and many patients will discontinue these medications because of significant AEs.6,21

5-α-RIs (finasteride and dutasteride) inhibit the conversion of testosterone to more potent dihydrotestosterone. They effectively reduce prostate volume by 25 to 30%.22 The results occur slowly and can take 6 to 12 months to reach the desired outcome. These medications are effective in men with larger prostates and not as effective in men with smaller prostates.23 These medications can improve urinary flow rates by about 10%, reduce IPSS scores by 20 to 30%, reduce the risk of urinary retention by 50%, and reduce the progression of BPH to the point where surgery is required by 50%.24 Furthermore, 5-α-RIs lower PSA by > 50% after 12 months of treatment.25

A baseline PSA should be established before administration and after 6 months of treatment. Any increase in the PSA even if the level is within normal limits should be evaluated for prostate cancer. Sarkar and colleagues recently published a study evaluating prostate cancer diagnosis in patients treated with 5-α-RI and found there was a delay in diagnosing prostate cancer in this population. Controversy also exists as to the potential of these medications increasing the risk for high-grade prostate cancer, which has led to a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warning. AEs include decreased libido (1.5%), ejaculatory dysfunction (3.4%), gynecomastia (1.3%), and/or ED (1.6%).26-28 A recent study evaluating 5-α-RIs demonstrated about a 2-fold increased risk of depression.29

There are well-established studies that note increased effectiveness when using combined α-blocker therapy with 5-α-RI medications. The Medical Therapy of Prostate Symptoms (MTOPS) and Combination Avodart and Tamsulosin (CombAT) trials showed that the combination of both medications was more effective in improving voiding symptoms and flow rates than either agent alone.15,16 Combination therapy resulted in a 66% reduction in disease progression, 81% reduction in urinary retention, and a 67% reduction in the need for surgery compared with placebo.

Anticholinergic medication use in BPH with LUTS is well established, and their use is often combined with other therapies. Anticholinergics work by inhibiting muscarinic M3 receptors to reduce detrusor muscle contraction. This effectively decreases bladder contractions and delays the desire to void. Kaplan and colleagues showed that tolterodine significantly improved a patient’s QOL when added to α-blocker therapy.30 Patients reported a positive outcome at 12 weeks, which resulted in a reduction in urgency incontinence, urgency, nocturia, and the overall number of voiding episodes within 24 hours.

β-3 agonists are a class of medications for OAB; mirabegron and vibegron have proven effective in reducing similar symptoms. In phase 3 clinical trials, mirabegron improved urinary incontinence episodes by 50% and reduced the number of voids in 24 hours.31 Mirabegron is well tolerated and avoids many common anticholinergic effects.32 Vibegron is the newest medication in the class and could soon become the preferred agent given it does not have cytochrome P450 interactions and does not cause hypertension like mirabegron.33

Anticholinergics should be used with caution in patients with a history of urinary retention, elevated after-void residual, or other medications with known anticholinergic effects. AEs include sedation, confusion, dry mouth, constipation, and potential falls in older patients.18 Recent studies have noted an association with dementia in the prolonged use of these medications in older patients and should be used cautiously.20

Phosphodiesterase-5 enzyme inhibitors (PDE-5) are adjunctive medications shown to improve LUTS. This class of medication is prescribed mostly for ED. However, tadalafil 5 mg taken daily also is FDA approved for the treatment of LUTS secondary to BPH given its prolonged half-life. The exact mechanism for improved BPH symptoms is unknown. Possibly the effects are due to an increase mediated by PDE-5 in cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), which increases smooth muscle relaxation and tissue perfusion of the prostate and bladder.34 There have been limited studies on objective improvement in uroflowmetry parameters compared with other treatments. The daily dosing of tadalafil should not be prescribed in men with a creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min.29 Tadalafil is not considered a first-line agent and is usually reserved for patients who experience ED in addition to BPH. When initiating BPH pharmacologic therapy, the PCP should be aware of adherence and high discontinuation rates.35

Surgical Treatments

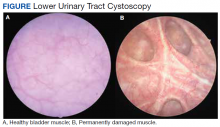

Surgical treatments are often delayed out of fear of potential AEs or considered a last resort when symptoms are too severe.36 Early intervention is required to prevent irreversible deleterious changes to detrusor muscle structure and function (Figure). Patients fear urinary incontinence, ED or ejaculatory dysfunction, and anesthesia complications associated with surgical interventions.6,37 Multiple studies show that patients fare better with early surgical intervention, experiencing improved IPSS scores, urinary flow, and QOL. The following is an overview of the most popular procedures.

Prostatic urethral lift (PUL) using the UroLift System is an FDA-approved, minimally-invasive treatment of LUTS secondary to BPH. This procedure treats prostates < 80 g with an absent median lobe.6,21,38 Permanent implants are placed per the prostatic urethra to displace obstructing prostate tissue laterally. This opens the urethra directly without cutting, heating, or removing any prostate tissue. This procedure is minimally invasive, often done in the office as an outpatient procedure, and offers better symptom relief than medication with a lower risk profile than transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP).39,40 The LIFT study was a multicenter, randomized, blinded trial; patients were randomized 2:1 to undergo UroLift or a sham operation. At 3 years, average improvements were statistically significant for total IPSS reduction (41%), QOL improvement (49%), and improved maximum flow rates by (51%).41 Risk for urinary incontinence is low, and the procedure has been shown to preserve erectile and ejaculatory function. Furthermore, patients report significant improvement in their QOL without the need for medications. Surgical retreatment rates at 5 years are 13.6%, with an additional 10.7% of subjects back on medication therapy with α-blockers or 5-α-RIs.42

Water vapor thermal therapy or Rez¯um uses steam as thermal energy to destroy obstructing prostate tissue and relieve the obstruction.43 The procedure differs from older conductive heat thermotherapies because the steam penetrates prostate zonal anatomy without affecting areas outside the targeted treatment zone. The procedure is done in the office with local anesthesia and provides long-lasting relief of LUTS with minimal risks. Following the procedure, patients require an indwelling urethral catheter for 3 to 7 days, and most patients begin to experience symptom improvement 2 to 4 weeks following the procedure.44 The procedure received FDA approval in 2015. Four-year data show significant improvement in maximal flow rate (50%), IPSS (47%), and QOL (43%).45 Surgical retreatment rates were 4.4%. Criticisms of this treatment include patient discomfort with the office procedure, the requirement for an indwelling catheter for a short period, and lack of long-term outcomes data. Guidelines support use in prostate volumes > 80 g with or without median lobe anatomy.

TURP is the gold standard to which other treatments are compared.46 The surgery is performed in the operating room where urologists use a rigid cystoscope and resection element to effectively carve out and cauterize obstructing prostate tissue. Patients typically recover for a short period with an indwelling urethral catheter that is often removed 12 to 24 hours after surgery. New research points out that despite increasing mean age (55% of patients are aged > 70 years with associated comorbidities), the morbidity of TURP was < 1% and mortality rate of 0 to 0.3%.47 Postoperative complications include bleeding that requires a transfusion (3%), retrograde ejaculation (65%), and rare urinary incontinence (2%).47 Surgical retreatment rates for patients following a TURP are approximately 13 to 15% at 8 years.34

Laser surgery for BPH includes multiple techniques: photovaporization of the prostate using a Greenlight XPS laser, holmium laser ablation, and holmium laser enucleation (HoLEP). Proponents of these treatments cite lower bleeding risks compared with TURP, but the operation is largely surgeon dependent on the technology chosen. Most studies comparing these technologies with TURP show similar outcomes of IPSS reports, quality of life improvements, and complications.

Patients with extremely large prostates, > 100 g or 4 times the normal size, pose a unique challenge to surgical treatment. Historically, patients were treated with an open simple prostatectomy operation or staged TURP procedures. Today, urologists use newer, safer ways to treat these patients. Both HoLEP and robot-assisted simple prostatectomy work well in relieving urinary symptoms with lower complications compared with older open surgery. Other minimally invasive procedures, such as prostatic artery embolism, have been described for the treatment of BPH specifically in men who may be unfit for surgery.48Future treatments are constantly evolving. Many unanswered questions remain about BPH and the role of inflammation, metabolic dysfunction, obesity, and other genetic factors driving BPH and prostate growth. Pharmaceutical opportunities exist in mechanisms aimed to reduce prostate growth, induce cellular apoptosis, as well as other drugs to reduce bladder symptoms. Newer, minimally invasive therapies also will become more readily available, such as Aquablation, which is the first FDA-granted surgical robot for the autonomous removal of prostatic tissue due to BPH.49 However, the goal of all future therapies should include the balance of alleviating disruptive symptoms while demonstrating a favorable risk profile. Many men discontinue taking medications, yet few present for surgery. Most concerning is the significant population of men who will develop irreversible bladder dysfunction while waiting for the perfect treatment. There are many opportunities for an effective treatment that is less invasive than surgery, provides durable relief, has minimal AEs, and is affordable.

Conclusions

There is no perfect treatment for patients with LUTS. All interventions have potential AEs and associated complications. Medications are often started as first-line therapy but are often discontinued at the onset of significant AEs. This process is often repeated. Many patients will try different medications without any significant improvement in their symptoms or short-term relief, which results in the gradual progression of the disease.

The PCP plays a significant role in the initial evaluation and management of BPH. These frontline clinicians can recognize patients who may already be experiencing sequela of prolonged bladder outlet obstruction and refer these men to urologists promptly. Counseling patients about their treatment options is an important duty for all PCPs.

A clear understanding of the available treatment options will help PCPs counsel patients appropriately about lifestyle modification, medications, and surgical treatment options for their symptoms. The treatment of this disorder is a rapidly evolving topic with the constant introduction of new technologies and medications, which are certain to continue to play an important role for PCPs and urologists.

1. Roehrborn CG. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: an overview. Rev Urol. 2005;7 Suppl 9(Suppl 9):S3-S14

2. McVary KT. Clinical manifestations and diagnostic evaluation of benign prostatic hyperplasia. UpToDate. Updated November 18, 2021. Accessed November 23, 2021. https:// www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and -diagnostic-evaluation-of-benign-prostatic-hyperplasia

3. McVary KT. BPH: epidemiology and comorbidities. Am J Manag Care. 2006;12(5 Suppl):S122-S128.

4. Ho CK, Habib FK. Estrogen and androgen signaling in the pathogenesis of BPH. Nat Rev Urol. 2011;8(1):29-41. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2010.207

5. Rensing AJ, Kuxhausen A, Vetter J, Strope SA. Differences in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia: comparing the primary care physician and the urologist. Urol Pract. 2017;4(3):193-199. doi:10.1016/j.urpr.2016.07.002

6. Foster HE, Barry MJ, Dahm P, et al. Surgical management of lower urinary tract symptoms attributed to benign prostatic hyperplasia: AUA guideline. J Urol. 2018;200(3):612- 619. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2018.05.048

7. Landau A, Welliver C. Analyzing and characterizing why men seek care for lower urinary tract symptoms. Curr Urol Rep. 2020;21(12):58. Published 2020 Oct 30. doi:10.1007/s11934-020-01006-w

8. Das AK, Leong JY, Roehrborn CG. Office-based therapies for benign prostatic hyperplasia: a review and update. Can J Urol. 2019;26(4 Suppl 1):2-7.

9. Parsons JK, Sarma AV, McVary K, Wei JT. Obesity and benign prostatic hyperplasia: clinical connections, emerging etiological paradigms and future directions. J Urol. 2013;189(1 Suppl):S102-S106. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2012.11.029

10. Pattanaik S, Mavuduru RS, Panda A, et al. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors for lower urinary tract symptoms consistent with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11(11):CD010060. Published 2018 Nov 16. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010060.pub2

11. McVary KT. Medical treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. UpToDate. Updated October 4, 2021. Accessed November 23, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents /medical-treatment-of-benign-prostatic-hyperplasia

12. Zhang W, Ma L, Bauer BA, Liu Z, Lu Y. Acupuncture for benign prostatic hyperplasia: A systematic review and metaanalysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0174586. Published 2017 Apr 4. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0174586

13. Newman DK, Guzzo T, Lee D, Jayadevappa R. An evidence- based strategy for the conservative management of the male patient with incontinence. Curr Opin Urol. 2014;24(6):553-559. doi:10.1097/MOU.0000000000000115

14. Newman DK, Wein AJ. Office-based behavioral therapy for management of incontinence and other pelvic disorders. Urol Clin North Am. 2013;40(4):613-635. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2013.07.010

15. McConnell JD, Roehrborn CG, Bautista OM, et al. The long-term effect of doxazosin, finasteride, and combination therapy on the clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(25):2387-2398. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa030656

16. Roehrborn CG, Barkin J, Siami P, et al. Clinical outcomes after combined therapy with dutasteride plus tamsulosin or either monotherapy in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) by baseline characteristics: 4-year results from the randomized, double-blind Combination of Avodart and Tamsulosin (CombAT) trial. BJU Int. 2011;107(6):946-954. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10124.x

17. Djavan B, Marberger M. A meta-analysis on the efficacy and tolerability of alpha1-adrenoceptor antagonists in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic obstruction. Eur Urol. 1999;36(1):1-13. doi:10.1159/000019919

18. By the American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227-2246. doi:10.1111/jgs.13702

19. Duan Y, Grady JJ, Albertsen PC, Helen Wu Z. Tamsulosin and the risk of dementia in older men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2018;27(3):340- 348. doi:10.1002/pds.4361

20. Coupland CAC, Hill T, Dening T, Morriss R, Moore M, Hippisley-Cox J. Anticholinergic drug exposure and the risk of dementia: a nested case-control study. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(8):1084-1093. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0677

21. Parsons JK, Dahm P, Köhler TS, Lerner LB, Wilt TJ. Surgical management of lower urinary tract symptoms attributed to benign prostatic hyperplasia: AUA guideline amendment 2020. J Urol. 2020;204(4):799-804. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000001298

22. Smith AB, Carson CC. Finasteride in the treatment of patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia: a review. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2009;5(3):535-545. doi:10.2147/tcrm.s6195

23. Andriole GL, Guess HA, Epstein JI, et al. Treatment with finasteride preserves usefulness of prostate-specific antigen in the detection of prostate cancer: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. PLESS Study Group. Proscar Long-term Efficacy and Safety Study. Urology. 1998;52(2):195-202. doi:10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00184-8

24. McConnell JD, Bruskewitz R, Walsh P, et al. The effect of finasteride on the risk of acute urinary retention and the need for surgical treatment among men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Finasteride Long-Term Efficacy and Safety Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(9):557-563. doi:10.1056/NEJM199802263380901

25. Rittmaster RS. 5alpha-reductase inhibitors in benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer risk reduction. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;22(2):389-402. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2008.01.016

26. La Torre A, Giupponi G, Duffy D, Conca A, Cai T, Scardigli A. Sexual dysfunction related to drugs: a critical review. Part V: α-blocker and 5-ARI drugs. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2016;49(1):3-13. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1565100

27. Corona G, Tirabassi G, Santi D, et al. Sexual dysfunction in subjects treated with inhibitors of 5α-reductase for benign prostatic hyperplasia: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Andrology. 2017;5(4):671-678. doi:10.1111/andr.12353

28. Trost L, Saitz TR, Hellstrom WJ. Side effects of 5-alpha reductase inhibitors: a comprehensive review. Sex Med Rev. 2013;1(1):24-41. doi:10.1002/smrj.3

29. Welk B, McArthur E, Ordon M, Anderson KK, Hayward J, Dixon S. Association of suicidality and depression with 5α-reductase inhibitors. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):683-691. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0089

30. Kaplan SA, Roehrborn CG, Rovner ES, Carlsson M, Bavendam T, Guan Z. Tolterodine and tamsulosin for treatment of men with lower urinary tract symptoms and overactive bladder: a randomized controlled trial [published correction appears in JAMA. 2007 Mar 21:297(11):1195] [published correction appears in JAMA. 2007 Oct 24;298(16):1864]. JAMA. 2006;296(19):2319-2328. doi:10.1001/jama.296.19.2319

31. Nitti VW, Auerbach S, Martin N, Calhoun A, Lee M, Herschorn S. Results of a randomized phase III trial of mirabegron in patients with overactive bladder. J Urol. 2013;189(4):1388-1395. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2012.10.017

32. Chapple CR, Cardozo L, Nitti VW, Siddiqui E, Michel MC. Mirabegron in overactive bladder: a review of efficacy, safety, and tolerability. Neurourol Urodyn. 2014;33(1):17-30. doi:10.1002/nau.22505

33. Rutman MP, King JR, Bennett N, Ankrom W, Mudd PN. PD14-01 once-daily vibegron, a novel oral β3 agonist does not inhibit CYP2D6, a common pathway for drug metabolism in patients on OAB medications. J Urol. 2019;201(Suppl 4):e231. doi:10.1097/01.JU.0000555478.73162.19

34. Bo K, Frawley HC, Haylen BT, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for the conservative and nonpharmacological management of female pelvic floor dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36(2):221- 244. doi:10.1002/nau.23107

35. Cindolo L, Pirozzi L, Fanizza C, et al. Drug adherence and clinical outcomes for patients under pharmacological therapy for lower urinary tract symptoms related to benign prostatic hyperplasia: population-based cohort study. Eur Urol. 2015;68(3):418-425. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2014.11.006

36. Ruhaiyem ME, Alshehri AA, Saade M, Shoabi TA, Zahoor H, Tawfeeq NA. Fear of going under general anesthesia: a cross-sectional study. Saudi J Anaesth. 2016;10(3):317- 321. doi:10.4103/1658-354X.179094

37. Hashim MJ. Patient-centered communication: basic skills. Am Fam Physician. 2017;95(1):29-34.

38. Roehrborn CG, Barkin J, Gange SN, et al. Five year results of the prospective randomized controlled prostatic urethral L.I.F.T. study. Can J Urol. 2017;24(3):8802-8813.

39. Gratzke C, Barber N, Speakman MJ, et al. Prostatic urethral lift vs transurethral resection of the prostate: 2-year results of the BPH6 prospective, multicentre, randomized study. BJU Int. 2017;119(5):767-775.doi:10.1111/bju.13714

40. Sønksen J, Barber NJ, Speakman MJ, et al. Prospective, randomized, multinational study of prostatic urethral lift versus transurethral resection of the prostate: 12-month results from the BPH6 study. Eur Urol. 2015;68(4):643-652. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2015.04.024

41. Roehrborn CG, Gange SN, Shore ND, et al. The prostatic urethral lift for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms associated with prostate enlargement due to benign prostatic hyperplasia: the L.I.F.T. Study. J Urol. 2013;190(6):2161-2167. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2013.05.116

42. McNicholas TA. Benign prostatic hyperplasia and new treatment options - a critical appraisal of the UroLift system. Med Devices (Auckl). 2016;9:115-123. Published 2016 May 19. doi:10.2147/MDER.S60780

43. McVary KT, Rogers T, Roehrborn CG. Rezuˉm Water Vapor thermal therapy for lower urinary tract symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia: 4-year results from randomized controlled study. Urology. 2019;126:171-179. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2018.12.041

44. Bole R, Gopalakrishna A, Kuang R, et al. Comparative postoperative outcomes of Rezˉum prostate ablation in patients with large versus small glands. J Endourol. 2020;34(7):778-781. doi:10.1089/end.2020.0177

45. Darson MF, Alexander EE, Schiffman ZJ, et al. Procedural techniques and multicenter postmarket experience using minimally invasive convective radiofrequency thermal therapy with Rezˉum system for treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hyperplasia. Res Rep Urol. 2017;9:159-168. Published 2017 Aug 21. doi:10.2147/RRU.S143679

46. Baazeem A, Elhilali MM. Surgical management of benign prostatic hyperplasia: current evidence. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2008;5(10):540-549. doi:10.1038/ncpuro1214

47. Rassweiler J, Teber D, Kuntz R, Hofmann R. Complications of transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP)- -incidence, management, and prevention. Eur Urol. 2006;50(5):969-980. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.042

48. Abt D, Schmid HP, Speakman MJ. Reasons to consider prostatic artery embolization. World J Urol. 2021;39(7):2301-2306. doi:10.1007/s00345-021-03601-z

49. Nguyen DD, Barber N, Bidair M, et al. Waterjet Ablation Therapy for Endoscopic Resection of prostate tissue trial (WATER) vs WATER II: comparing Aquablation therapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia in30-80and80-150mLprostates. BJUInt. 2020;125(1):112-122. doi:10.1111/bju.14917.

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS)are common and tend to increase in frequency with age. Managing LUTS can be complicated, requires an informed discussion between the primary care practitioner (PCP) and patient, and is best achieved by a thorough understanding of the many medical and surgical options available. Over the past 3 decades, medications have become the most common therapy; but recently, newer minimally invasive surgeries have challenged this paradigm. This article provides a comprehensive review for PCPs regarding the evaluation and management of LUTS in men and when to consider a urology referral.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and LUTS are common clinical encounters for most PCPs. About 50% of men will develop LUTS associated with BPH, and symptoms associated with these conditions increase as men age.1,2 Studies have estimated that 90% of men aged 45 to 80 years demonstrate some symptoms of LUTS.3 Strong genetic influence seems to suggest heritability, but BPH also occurs in sporadic forms and is heavily influenced by androgens.4

BPH is a histologic diagnosis, whereas LUTS consists of complex symptomatology related to both static or dynamic components.1 The enlarged prostate gland obstructs the urethra, simultaneously causing an increase in muscle tone and resistance at the bladder neck and prostatic urethra, leading to increased resistance to urine flow. As a result, there is a thickening of the detrusor muscles in the bladder wall and an overall decreased compliance. Urine becomes stored under increased pressure. These changes result in a weak or intermittent urine stream, incomplete emptying of the bladder, postvoid dribble, hesitancy, and irritative symptoms, such as urgency, frequency, and nocturia.

For many patients, BPH associated with LUTS is a quality of life (QOL) issue. The stigma associated with these symptoms often leads to delays in patients seeking care. Many patients do not seek treatment until symptoms have become so severe that changes in bladder health are often irreversible. Early intervention can dramatically improve a patient’s QOL. Also, early intervention has the potential to reduce overall health care expenditures. BPH-related spending exceeds $1 billion each year in the Medicare program alone.5

PCPs are in a unique position to help many patients who present with early-stage LUTS. Given the substantial impact this disease has on QOL, early recognition of symptoms and prompt treatment play a major role. Paramount to this effort is awareness and understanding of various treatments, their advantages, and adverse effects (AEs). This article highlights evidence-based evaluation and treatment of BPH/LUTS for PCPs who treat veterans and recommendations as to when to refer a patient to a urologist.

Evaluation of LUTS and BPH

Evaluation begins with a thorough medical history and physical examination. Particular attention should focus on ruling out other causes of LUTS, such as a urinary tract infection (UTI), acute prostatitis, malignancy, bladder dysfunction, neurogenic bladder, and other obstructive pathology, such as urethral stricture disease. The differential diagnosis of LUTS includes BPH, UTI, bladder neck obstruction, urethral stricture, bladder stones, polydipsia, overactive bladder (OAB), nocturnal polyuria, neurologic disease, genitourinary malignancy, renal failure, and acute/chronic urinary retention.6

Relevant medical history influencing urinary symptoms includes diabetes mellitus, underlying neurologic diseases, previous trauma, sexually transmitted infections, and certain medications. Symptom severity may be obtained using a validated questionnaire, such as the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), which also aids clinicians in assessing the impact of LUTS on QOL. Additionally, urinary frequency or volume records (voiding diary) may help establish the severity of the patient’s symptoms and provide insight into other potential causes for LUTS. Patients with BPH often have concurrent erectile dysfunction (ED) or other sexual dysfunction symptoms. Patients should be evaluated for baseline sexual dysfunction before the initiation of treatment as many therapies worsen symptoms of ED or ejaculatory dysfunction.

A comprehensive physical examination with a focus on the genitourinary system should, at minimum, assess for abnormalities of the urethral meatus, prepuce, penis, groin nodes, and prior surgical scars. A digital rectal examination also should be performed. Although controversial, a digital rectal examination for prostate cancer screening may provide a rough estimate of prostate size, help rule out prostatitis, and detect incident prostate nodules. Prostate size does not necessarily correlate well with the degree of urinary obstruction or LUTS but is an important consideration when deciding among different therapies.1

Laboratory and Adjunctive Tests

A urinalysis with microscopy helps identify other potential causes for urinary symptoms, including infection, proteinuria, or glucosuria. In patients who present with gross or microscopic hematuria, additional consideration should be given to bladder calculi and genitourinary cancer.2 When a reversible source for the hematuria is not identified, these patients require referral to a urologist for a hematuria evaluation.

There is some controversy regarding prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing. Most professional organizations advocate for a shared decision-making approach before testing. The American Cancer Society recommends this informed discussion occur between the patient and the PCP for men aged > 50 years at average risk, men aged > 45 years at high risk of developing prostate cancer (African Americans or first-degree relative with early prostate cancer diagnosis), and aged 40 years for men with more than one first-degree relative with an early prostate cancer diagnosis.7

Adjunctive tests include postvoid residual (PVR), cystoscopy, uroflowmetry, urodynamics, and transrectal ultrasound. However, these are mostly performed by urologists. In some patients with bladder decompensation after prolonged partial bladder outlet obstruction, urodynamics may be used by urologists to determine whether a patient may benefit from an outlet obstruction procedure. Ordering additional imaging or serum studies for the assessment of LUTS is rarely helpful.

Treatment

Treatment includes management with or without lifestyle modification, medication administration, and surgical therapy. New to this paradigm are in-office minimally invasive surgical options. The goal of treatment is not only to reduce patient symptoms and improve QOL, but also to prevent the secondary sequala of urinary retention, bladder failure, and eventual renal impairment.7A basic understanding of these treatments can aid PCPs with appropriate patient counseling and urologic referral.8

Lifestyle and Behavior Modification

Behavior modification is the starting point for all patients with LUTS. Lifestyle modifications for LUTS include avoiding substances that exacerbate symptoms, such as α-agonists (decongestants), caffeine, alcohol, spicy/acidic foods, chocolate, and soda. These substances are known to be bladder irritants. Common medications contributing to LUTS include antidepressants, decongestants, antihistamines, bronchodilators, anticholinergics, and sympathomimetics. To decrease nocturia, behavioral modifications include limiting evening fluid intake, timed diuretic administration for patients already on a diuretic, and elevating legs 1 hour before bedtime. Counseling obese patients to lose weight and increasing physical activity have been linked to reduced LUTS.9 Other behavioral techniques include double voiding: a technique where patients void normally then change positions and return to void to empty the bladder. Another technique is timed voiding: Many patients have impaired sensation when the bladder is full. These patients are encouraged to void at regular intervals.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Multiple nutraceutical compounds claim improved urinary health and symptom reduction. These compounds are marketed to patients with little regulation and oversight since supplements are not regulated or held to the same standard as prescription medications. The most popular nutraceutical for prostate health and LUTS is saw palmetto. Despite its common usage for the treatment of LUTS, little data support saw palmetto health claims. In 2012, a systematic review of 32 randomized trials including 5666 patients compared saw palmetto with a placebo. The study found no difference in urinary symptom scores, urinary flow, or prostate size.10,11 Other phytotherapy compounds often considered for urinary symptoms include stinging nettle extract and β-sitosterol compounds. The mechanism of action of these agents is unknown and efficacy data are lacking.

Historically, acupuncture and pelvic floor physical therapy have been used successfully for OAB symptoms. A meta-analysis found positive beneficial effects of acupuncture compared with a sham control for short- and medium-term follow-up in both IPSS and urine flow rates in some studies; however, when combining the studies for more statistical power, the benefits were less clear.12 Physical therapists with specialized training and certification in pelvic health can incorporate certain bladder training techniques. These include voiding positional changes (double voiding and postvoid urethral milking) and timed voiding.13,14 These interventions often address etiologies of LUTS for which medical therapies are not effective as the sole treatment option.

Medication Management

Medical management includes α-blockers, 5-α-reductase inhibitors (5-α-RIs), antimuscarinic or anticholinergic medicines, β-3 agonists, and phosphodiesterase inhibitors (Table). These medications work independently as well as synergistically. The use of medications to improve symptoms must be balanced against potential AEs and the consequences of a lifetime of drug usage, which can be additive.15,16

First-line pharmacological therapy for BPH is α-blockers, which work by blocking α1A receptors in the prostate and bladder neck, leading to smooth muscle relaxation, increased diameter of the channel, and improved urinary flow. α-receptors in the bladder neck and prostate are expressed with increased frequency with age and are a potential cause for worsening symptoms as men age. Studies demonstrate that these medications reduce symptoms by 30 to 40% and increase flow rates by 16 to 25%.17 Commonly prescribed α-blockers include tamsulosin, alfuzosin, silodosin, doxazosin, and terazosin. Doxazosin and terazosin require dose titrations because they may cause significant hypotension. Orthostatic hypotension typically improves with time and is avoided if the patient takes the medication at bedtime. Both doxazosin and terazosin are on the American Geriatric Society’s Beers Criteria list and should be avoided in older patients.18 Tamsulosin, alfuzosin, and silodosin have a standardized dosing regimen and lower rates of hypotension. Significant AEs include ejaculation dysfunction, nasal congestion, and orthostatic hypotension. Duan and colleagues have linked tamsulosin with dementia. However, this association is not causal and further studies are necessary.19,20 Patients who have taken these agents also are at risk for intraoperative floppy iris syndrome (IFIS). Permanent visual problems can arise if the intraoperative management is not managed to account for IFIS. These medications have a rapid onset of action and work immediately. However, to reach maximum benefit, patients must take the medication for several weeks. Unfortunately, up to one-third of patients will have no improvement with α-blocker therapy, and many patients will discontinue these medications because of significant AEs.6,21

5-α-RIs (finasteride and dutasteride) inhibit the conversion of testosterone to more potent dihydrotestosterone. They effectively reduce prostate volume by 25 to 30%.22 The results occur slowly and can take 6 to 12 months to reach the desired outcome. These medications are effective in men with larger prostates and not as effective in men with smaller prostates.23 These medications can improve urinary flow rates by about 10%, reduce IPSS scores by 20 to 30%, reduce the risk of urinary retention by 50%, and reduce the progression of BPH to the point where surgery is required by 50%.24 Furthermore, 5-α-RIs lower PSA by > 50% after 12 months of treatment.25

A baseline PSA should be established before administration and after 6 months of treatment. Any increase in the PSA even if the level is within normal limits should be evaluated for prostate cancer. Sarkar and colleagues recently published a study evaluating prostate cancer diagnosis in patients treated with 5-α-RI and found there was a delay in diagnosing prostate cancer in this population. Controversy also exists as to the potential of these medications increasing the risk for high-grade prostate cancer, which has led to a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warning. AEs include decreased libido (1.5%), ejaculatory dysfunction (3.4%), gynecomastia (1.3%), and/or ED (1.6%).26-28 A recent study evaluating 5-α-RIs demonstrated about a 2-fold increased risk of depression.29

There are well-established studies that note increased effectiveness when using combined α-blocker therapy with 5-α-RI medications. The Medical Therapy of Prostate Symptoms (MTOPS) and Combination Avodart and Tamsulosin (CombAT) trials showed that the combination of both medications was more effective in improving voiding symptoms and flow rates than either agent alone.15,16 Combination therapy resulted in a 66% reduction in disease progression, 81% reduction in urinary retention, and a 67% reduction in the need for surgery compared with placebo.

Anticholinergic medication use in BPH with LUTS is well established, and their use is often combined with other therapies. Anticholinergics work by inhibiting muscarinic M3 receptors to reduce detrusor muscle contraction. This effectively decreases bladder contractions and delays the desire to void. Kaplan and colleagues showed that tolterodine significantly improved a patient’s QOL when added to α-blocker therapy.30 Patients reported a positive outcome at 12 weeks, which resulted in a reduction in urgency incontinence, urgency, nocturia, and the overall number of voiding episodes within 24 hours.

β-3 agonists are a class of medications for OAB; mirabegron and vibegron have proven effective in reducing similar symptoms. In phase 3 clinical trials, mirabegron improved urinary incontinence episodes by 50% and reduced the number of voids in 24 hours.31 Mirabegron is well tolerated and avoids many common anticholinergic effects.32 Vibegron is the newest medication in the class and could soon become the preferred agent given it does not have cytochrome P450 interactions and does not cause hypertension like mirabegron.33

Anticholinergics should be used with caution in patients with a history of urinary retention, elevated after-void residual, or other medications with known anticholinergic effects. AEs include sedation, confusion, dry mouth, constipation, and potential falls in older patients.18 Recent studies have noted an association with dementia in the prolonged use of these medications in older patients and should be used cautiously.20

Phosphodiesterase-5 enzyme inhibitors (PDE-5) are adjunctive medications shown to improve LUTS. This class of medication is prescribed mostly for ED. However, tadalafil 5 mg taken daily also is FDA approved for the treatment of LUTS secondary to BPH given its prolonged half-life. The exact mechanism for improved BPH symptoms is unknown. Possibly the effects are due to an increase mediated by PDE-5 in cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), which increases smooth muscle relaxation and tissue perfusion of the prostate and bladder.34 There have been limited studies on objective improvement in uroflowmetry parameters compared with other treatments. The daily dosing of tadalafil should not be prescribed in men with a creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min.29 Tadalafil is not considered a first-line agent and is usually reserved for patients who experience ED in addition to BPH. When initiating BPH pharmacologic therapy, the PCP should be aware of adherence and high discontinuation rates.35

Surgical Treatments

Surgical treatments are often delayed out of fear of potential AEs or considered a last resort when symptoms are too severe.36 Early intervention is required to prevent irreversible deleterious changes to detrusor muscle structure and function (Figure). Patients fear urinary incontinence, ED or ejaculatory dysfunction, and anesthesia complications associated with surgical interventions.6,37 Multiple studies show that patients fare better with early surgical intervention, experiencing improved IPSS scores, urinary flow, and QOL. The following is an overview of the most popular procedures.

Prostatic urethral lift (PUL) using the UroLift System is an FDA-approved, minimally-invasive treatment of LUTS secondary to BPH. This procedure treats prostates < 80 g with an absent median lobe.6,21,38 Permanent implants are placed per the prostatic urethra to displace obstructing prostate tissue laterally. This opens the urethra directly without cutting, heating, or removing any prostate tissue. This procedure is minimally invasive, often done in the office as an outpatient procedure, and offers better symptom relief than medication with a lower risk profile than transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP).39,40 The LIFT study was a multicenter, randomized, blinded trial; patients were randomized 2:1 to undergo UroLift or a sham operation. At 3 years, average improvements were statistically significant for total IPSS reduction (41%), QOL improvement (49%), and improved maximum flow rates by (51%).41 Risk for urinary incontinence is low, and the procedure has been shown to preserve erectile and ejaculatory function. Furthermore, patients report significant improvement in their QOL without the need for medications. Surgical retreatment rates at 5 years are 13.6%, with an additional 10.7% of subjects back on medication therapy with α-blockers or 5-α-RIs.42

Water vapor thermal therapy or Rez¯um uses steam as thermal energy to destroy obstructing prostate tissue and relieve the obstruction.43 The procedure differs from older conductive heat thermotherapies because the steam penetrates prostate zonal anatomy without affecting areas outside the targeted treatment zone. The procedure is done in the office with local anesthesia and provides long-lasting relief of LUTS with minimal risks. Following the procedure, patients require an indwelling urethral catheter for 3 to 7 days, and most patients begin to experience symptom improvement 2 to 4 weeks following the procedure.44 The procedure received FDA approval in 2015. Four-year data show significant improvement in maximal flow rate (50%), IPSS (47%), and QOL (43%).45 Surgical retreatment rates were 4.4%. Criticisms of this treatment include patient discomfort with the office procedure, the requirement for an indwelling catheter for a short period, and lack of long-term outcomes data. Guidelines support use in prostate volumes > 80 g with or without median lobe anatomy.

TURP is the gold standard to which other treatments are compared.46 The surgery is performed in the operating room where urologists use a rigid cystoscope and resection element to effectively carve out and cauterize obstructing prostate tissue. Patients typically recover for a short period with an indwelling urethral catheter that is often removed 12 to 24 hours after surgery. New research points out that despite increasing mean age (55% of patients are aged > 70 years with associated comorbidities), the morbidity of TURP was < 1% and mortality rate of 0 to 0.3%.47 Postoperative complications include bleeding that requires a transfusion (3%), retrograde ejaculation (65%), and rare urinary incontinence (2%).47 Surgical retreatment rates for patients following a TURP are approximately 13 to 15% at 8 years.34

Laser surgery for BPH includes multiple techniques: photovaporization of the prostate using a Greenlight XPS laser, holmium laser ablation, and holmium laser enucleation (HoLEP). Proponents of these treatments cite lower bleeding risks compared with TURP, but the operation is largely surgeon dependent on the technology chosen. Most studies comparing these technologies with TURP show similar outcomes of IPSS reports, quality of life improvements, and complications.

Patients with extremely large prostates, > 100 g or 4 times the normal size, pose a unique challenge to surgical treatment. Historically, patients were treated with an open simple prostatectomy operation or staged TURP procedures. Today, urologists use newer, safer ways to treat these patients. Both HoLEP and robot-assisted simple prostatectomy work well in relieving urinary symptoms with lower complications compared with older open surgery. Other minimally invasive procedures, such as prostatic artery embolism, have been described for the treatment of BPH specifically in men who may be unfit for surgery.48Future treatments are constantly evolving. Many unanswered questions remain about BPH and the role of inflammation, metabolic dysfunction, obesity, and other genetic factors driving BPH and prostate growth. Pharmaceutical opportunities exist in mechanisms aimed to reduce prostate growth, induce cellular apoptosis, as well as other drugs to reduce bladder symptoms. Newer, minimally invasive therapies also will become more readily available, such as Aquablation, which is the first FDA-granted surgical robot for the autonomous removal of prostatic tissue due to BPH.49 However, the goal of all future therapies should include the balance of alleviating disruptive symptoms while demonstrating a favorable risk profile. Many men discontinue taking medications, yet few present for surgery. Most concerning is the significant population of men who will develop irreversible bladder dysfunction while waiting for the perfect treatment. There are many opportunities for an effective treatment that is less invasive than surgery, provides durable relief, has minimal AEs, and is affordable.

Conclusions

There is no perfect treatment for patients with LUTS. All interventions have potential AEs and associated complications. Medications are often started as first-line therapy but are often discontinued at the onset of significant AEs. This process is often repeated. Many patients will try different medications without any significant improvement in their symptoms or short-term relief, which results in the gradual progression of the disease.

The PCP plays a significant role in the initial evaluation and management of BPH. These frontline clinicians can recognize patients who may already be experiencing sequela of prolonged bladder outlet obstruction and refer these men to urologists promptly. Counseling patients about their treatment options is an important duty for all PCPs.

A clear understanding of the available treatment options will help PCPs counsel patients appropriately about lifestyle modification, medications, and surgical treatment options for their symptoms. The treatment of this disorder is a rapidly evolving topic with the constant introduction of new technologies and medications, which are certain to continue to play an important role for PCPs and urologists.

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS)are common and tend to increase in frequency with age. Managing LUTS can be complicated, requires an informed discussion between the primary care practitioner (PCP) and patient, and is best achieved by a thorough understanding of the many medical and surgical options available. Over the past 3 decades, medications have become the most common therapy; but recently, newer minimally invasive surgeries have challenged this paradigm. This article provides a comprehensive review for PCPs regarding the evaluation and management of LUTS in men and when to consider a urology referral.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and LUTS are common clinical encounters for most PCPs. About 50% of men will develop LUTS associated with BPH, and symptoms associated with these conditions increase as men age.1,2 Studies have estimated that 90% of men aged 45 to 80 years demonstrate some symptoms of LUTS.3 Strong genetic influence seems to suggest heritability, but BPH also occurs in sporadic forms and is heavily influenced by androgens.4

BPH is a histologic diagnosis, whereas LUTS consists of complex symptomatology related to both static or dynamic components.1 The enlarged prostate gland obstructs the urethra, simultaneously causing an increase in muscle tone and resistance at the bladder neck and prostatic urethra, leading to increased resistance to urine flow. As a result, there is a thickening of the detrusor muscles in the bladder wall and an overall decreased compliance. Urine becomes stored under increased pressure. These changes result in a weak or intermittent urine stream, incomplete emptying of the bladder, postvoid dribble, hesitancy, and irritative symptoms, such as urgency, frequency, and nocturia.

For many patients, BPH associated with LUTS is a quality of life (QOL) issue. The stigma associated with these symptoms often leads to delays in patients seeking care. Many patients do not seek treatment until symptoms have become so severe that changes in bladder health are often irreversible. Early intervention can dramatically improve a patient’s QOL. Also, early intervention has the potential to reduce overall health care expenditures. BPH-related spending exceeds $1 billion each year in the Medicare program alone.5

PCPs are in a unique position to help many patients who present with early-stage LUTS. Given the substantial impact this disease has on QOL, early recognition of symptoms and prompt treatment play a major role. Paramount to this effort is awareness and understanding of various treatments, their advantages, and adverse effects (AEs). This article highlights evidence-based evaluation and treatment of BPH/LUTS for PCPs who treat veterans and recommendations as to when to refer a patient to a urologist.

Evaluation of LUTS and BPH

Evaluation begins with a thorough medical history and physical examination. Particular attention should focus on ruling out other causes of LUTS, such as a urinary tract infection (UTI), acute prostatitis, malignancy, bladder dysfunction, neurogenic bladder, and other obstructive pathology, such as urethral stricture disease. The differential diagnosis of LUTS includes BPH, UTI, bladder neck obstruction, urethral stricture, bladder stones, polydipsia, overactive bladder (OAB), nocturnal polyuria, neurologic disease, genitourinary malignancy, renal failure, and acute/chronic urinary retention.6

Relevant medical history influencing urinary symptoms includes diabetes mellitus, underlying neurologic diseases, previous trauma, sexually transmitted infections, and certain medications. Symptom severity may be obtained using a validated questionnaire, such as the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), which also aids clinicians in assessing the impact of LUTS on QOL. Additionally, urinary frequency or volume records (voiding diary) may help establish the severity of the patient’s symptoms and provide insight into other potential causes for LUTS. Patients with BPH often have concurrent erectile dysfunction (ED) or other sexual dysfunction symptoms. Patients should be evaluated for baseline sexual dysfunction before the initiation of treatment as many therapies worsen symptoms of ED or ejaculatory dysfunction.

A comprehensive physical examination with a focus on the genitourinary system should, at minimum, assess for abnormalities of the urethral meatus, prepuce, penis, groin nodes, and prior surgical scars. A digital rectal examination also should be performed. Although controversial, a digital rectal examination for prostate cancer screening may provide a rough estimate of prostate size, help rule out prostatitis, and detect incident prostate nodules. Prostate size does not necessarily correlate well with the degree of urinary obstruction or LUTS but is an important consideration when deciding among different therapies.1

Laboratory and Adjunctive Tests

A urinalysis with microscopy helps identify other potential causes for urinary symptoms, including infection, proteinuria, or glucosuria. In patients who present with gross or microscopic hematuria, additional consideration should be given to bladder calculi and genitourinary cancer.2 When a reversible source for the hematuria is not identified, these patients require referral to a urologist for a hematuria evaluation.

There is some controversy regarding prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing. Most professional organizations advocate for a shared decision-making approach before testing. The American Cancer Society recommends this informed discussion occur between the patient and the PCP for men aged > 50 years at average risk, men aged > 45 years at high risk of developing prostate cancer (African Americans or first-degree relative with early prostate cancer diagnosis), and aged 40 years for men with more than one first-degree relative with an early prostate cancer diagnosis.7

Adjunctive tests include postvoid residual (PVR), cystoscopy, uroflowmetry, urodynamics, and transrectal ultrasound. However, these are mostly performed by urologists. In some patients with bladder decompensation after prolonged partial bladder outlet obstruction, urodynamics may be used by urologists to determine whether a patient may benefit from an outlet obstruction procedure. Ordering additional imaging or serum studies for the assessment of LUTS is rarely helpful.

Treatment

Treatment includes management with or without lifestyle modification, medication administration, and surgical therapy. New to this paradigm are in-office minimally invasive surgical options. The goal of treatment is not only to reduce patient symptoms and improve QOL, but also to prevent the secondary sequala of urinary retention, bladder failure, and eventual renal impairment.7A basic understanding of these treatments can aid PCPs with appropriate patient counseling and urologic referral.8

Lifestyle and Behavior Modification

Behavior modification is the starting point for all patients with LUTS. Lifestyle modifications for LUTS include avoiding substances that exacerbate symptoms, such as α-agonists (decongestants), caffeine, alcohol, spicy/acidic foods, chocolate, and soda. These substances are known to be bladder irritants. Common medications contributing to LUTS include antidepressants, decongestants, antihistamines, bronchodilators, anticholinergics, and sympathomimetics. To decrease nocturia, behavioral modifications include limiting evening fluid intake, timed diuretic administration for patients already on a diuretic, and elevating legs 1 hour before bedtime. Counseling obese patients to lose weight and increasing physical activity have been linked to reduced LUTS.9 Other behavioral techniques include double voiding: a technique where patients void normally then change positions and return to void to empty the bladder. Another technique is timed voiding: Many patients have impaired sensation when the bladder is full. These patients are encouraged to void at regular intervals.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Multiple nutraceutical compounds claim improved urinary health and symptom reduction. These compounds are marketed to patients with little regulation and oversight since supplements are not regulated or held to the same standard as prescription medications. The most popular nutraceutical for prostate health and LUTS is saw palmetto. Despite its common usage for the treatment of LUTS, little data support saw palmetto health claims. In 2012, a systematic review of 32 randomized trials including 5666 patients compared saw palmetto with a placebo. The study found no difference in urinary symptom scores, urinary flow, or prostate size.10,11 Other phytotherapy compounds often considered for urinary symptoms include stinging nettle extract and β-sitosterol compounds. The mechanism of action of these agents is unknown and efficacy data are lacking.

Historically, acupuncture and pelvic floor physical therapy have been used successfully for OAB symptoms. A meta-analysis found positive beneficial effects of acupuncture compared with a sham control for short- and medium-term follow-up in both IPSS and urine flow rates in some studies; however, when combining the studies for more statistical power, the benefits were less clear.12 Physical therapists with specialized training and certification in pelvic health can incorporate certain bladder training techniques. These include voiding positional changes (double voiding and postvoid urethral milking) and timed voiding.13,14 These interventions often address etiologies of LUTS for which medical therapies are not effective as the sole treatment option.

Medication Management

Medical management includes α-blockers, 5-α-reductase inhibitors (5-α-RIs), antimuscarinic or anticholinergic medicines, β-3 agonists, and phosphodiesterase inhibitors (Table). These medications work independently as well as synergistically. The use of medications to improve symptoms must be balanced against potential AEs and the consequences of a lifetime of drug usage, which can be additive.15,16

First-line pharmacological therapy for BPH is α-blockers, which work by blocking α1A receptors in the prostate and bladder neck, leading to smooth muscle relaxation, increased diameter of the channel, and improved urinary flow. α-receptors in the bladder neck and prostate are expressed with increased frequency with age and are a potential cause for worsening symptoms as men age. Studies demonstrate that these medications reduce symptoms by 30 to 40% and increase flow rates by 16 to 25%.17 Commonly prescribed α-blockers include tamsulosin, alfuzosin, silodosin, doxazosin, and terazosin. Doxazosin and terazosin require dose titrations because they may cause significant hypotension. Orthostatic hypotension typically improves with time and is avoided if the patient takes the medication at bedtime. Both doxazosin and terazosin are on the American Geriatric Society’s Beers Criteria list and should be avoided in older patients.18 Tamsulosin, alfuzosin, and silodosin have a standardized dosing regimen and lower rates of hypotension. Significant AEs include ejaculation dysfunction, nasal congestion, and orthostatic hypotension. Duan and colleagues have linked tamsulosin with dementia. However, this association is not causal and further studies are necessary.19,20 Patients who have taken these agents also are at risk for intraoperative floppy iris syndrome (IFIS). Permanent visual problems can arise if the intraoperative management is not managed to account for IFIS. These medications have a rapid onset of action and work immediately. However, to reach maximum benefit, patients must take the medication for several weeks. Unfortunately, up to one-third of patients will have no improvement with α-blocker therapy, and many patients will discontinue these medications because of significant AEs.6,21

5-α-RIs (finasteride and dutasteride) inhibit the conversion of testosterone to more potent dihydrotestosterone. They effectively reduce prostate volume by 25 to 30%.22 The results occur slowly and can take 6 to 12 months to reach the desired outcome. These medications are effective in men with larger prostates and not as effective in men with smaller prostates.23 These medications can improve urinary flow rates by about 10%, reduce IPSS scores by 20 to 30%, reduce the risk of urinary retention by 50%, and reduce the progression of BPH to the point where surgery is required by 50%.24 Furthermore, 5-α-RIs lower PSA by > 50% after 12 months of treatment.25

A baseline PSA should be established before administration and after 6 months of treatment. Any increase in the PSA even if the level is within normal limits should be evaluated for prostate cancer. Sarkar and colleagues recently published a study evaluating prostate cancer diagnosis in patients treated with 5-α-RI and found there was a delay in diagnosing prostate cancer in this population. Controversy also exists as to the potential of these medications increasing the risk for high-grade prostate cancer, which has led to a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warning. AEs include decreased libido (1.5%), ejaculatory dysfunction (3.4%), gynecomastia (1.3%), and/or ED (1.6%).26-28 A recent study evaluating 5-α-RIs demonstrated about a 2-fold increased risk of depression.29

There are well-established studies that note increased effectiveness when using combined α-blocker therapy with 5-α-RI medications. The Medical Therapy of Prostate Symptoms (MTOPS) and Combination Avodart and Tamsulosin (CombAT) trials showed that the combination of both medications was more effective in improving voiding symptoms and flow rates than either agent alone.15,16 Combination therapy resulted in a 66% reduction in disease progression, 81% reduction in urinary retention, and a 67% reduction in the need for surgery compared with placebo.

Anticholinergic medication use in BPH with LUTS is well established, and their use is often combined with other therapies. Anticholinergics work by inhibiting muscarinic M3 receptors to reduce detrusor muscle contraction. This effectively decreases bladder contractions and delays the desire to void. Kaplan and colleagues showed that tolterodine significantly improved a patient’s QOL when added to α-blocker therapy.30 Patients reported a positive outcome at 12 weeks, which resulted in a reduction in urgency incontinence, urgency, nocturia, and the overall number of voiding episodes within 24 hours.

β-3 agonists are a class of medications for OAB; mirabegron and vibegron have proven effective in reducing similar symptoms. In phase 3 clinical trials, mirabegron improved urinary incontinence episodes by 50% and reduced the number of voids in 24 hours.31 Mirabegron is well tolerated and avoids many common anticholinergic effects.32 Vibegron is the newest medication in the class and could soon become the preferred agent given it does not have cytochrome P450 interactions and does not cause hypertension like mirabegron.33

Anticholinergics should be used with caution in patients with a history of urinary retention, elevated after-void residual, or other medications with known anticholinergic effects. AEs include sedation, confusion, dry mouth, constipation, and potential falls in older patients.18 Recent studies have noted an association with dementia in the prolonged use of these medications in older patients and should be used cautiously.20

Phosphodiesterase-5 enzyme inhibitors (PDE-5) are adjunctive medications shown to improve LUTS. This class of medication is prescribed mostly for ED. However, tadalafil 5 mg taken daily also is FDA approved for the treatment of LUTS secondary to BPH given its prolonged half-life. The exact mechanism for improved BPH symptoms is unknown. Possibly the effects are due to an increase mediated by PDE-5 in cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), which increases smooth muscle relaxation and tissue perfusion of the prostate and bladder.34 There have been limited studies on objective improvement in uroflowmetry parameters compared with other treatments. The daily dosing of tadalafil should not be prescribed in men with a creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min.29 Tadalafil is not considered a first-line agent and is usually reserved for patients who experience ED in addition to BPH. When initiating BPH pharmacologic therapy, the PCP should be aware of adherence and high discontinuation rates.35

Surgical Treatments

Surgical treatments are often delayed out of fear of potential AEs or considered a last resort when symptoms are too severe.36 Early intervention is required to prevent irreversible deleterious changes to detrusor muscle structure and function (Figure). Patients fear urinary incontinence, ED or ejaculatory dysfunction, and anesthesia complications associated with surgical interventions.6,37 Multiple studies show that patients fare better with early surgical intervention, experiencing improved IPSS scores, urinary flow, and QOL. The following is an overview of the most popular procedures.

Prostatic urethral lift (PUL) using the UroLift System is an FDA-approved, minimally-invasive treatment of LUTS secondary to BPH. This procedure treats prostates < 80 g with an absent median lobe.6,21,38 Permanent implants are placed per the prostatic urethra to displace obstructing prostate tissue laterally. This opens the urethra directly without cutting, heating, or removing any prostate tissue. This procedure is minimally invasive, often done in the office as an outpatient procedure, and offers better symptom relief than medication with a lower risk profile than transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP).39,40 The LIFT study was a multicenter, randomized, blinded trial; patients were randomized 2:1 to undergo UroLift or a sham operation. At 3 years, average improvements were statistically significant for total IPSS reduction (41%), QOL improvement (49%), and improved maximum flow rates by (51%).41 Risk for urinary incontinence is low, and the procedure has been shown to preserve erectile and ejaculatory function. Furthermore, patients report significant improvement in their QOL without the need for medications. Surgical retreatment rates at 5 years are 13.6%, with an additional 10.7% of subjects back on medication therapy with α-blockers or 5-α-RIs.42

Water vapor thermal therapy or Rez¯um uses steam as thermal energy to destroy obstructing prostate tissue and relieve the obstruction.43 The procedure differs from older conductive heat thermotherapies because the steam penetrates prostate zonal anatomy without affecting areas outside the targeted treatment zone. The procedure is done in the office with local anesthesia and provides long-lasting relief of LUTS with minimal risks. Following the procedure, patients require an indwelling urethral catheter for 3 to 7 days, and most patients begin to experience symptom improvement 2 to 4 weeks following the procedure.44 The procedure received FDA approval in 2015. Four-year data show significant improvement in maximal flow rate (50%), IPSS (47%), and QOL (43%).45 Surgical retreatment rates were 4.4%. Criticisms of this treatment include patient discomfort with the office procedure, the requirement for an indwelling catheter for a short period, and lack of long-term outcomes data. Guidelines support use in prostate volumes > 80 g with or without median lobe anatomy.

TURP is the gold standard to which other treatments are compared.46 The surgery is performed in the operating room where urologists use a rigid cystoscope and resection element to effectively carve out and cauterize obstructing prostate tissue. Patients typically recover for a short period with an indwelling urethral catheter that is often removed 12 to 24 hours after surgery. New research points out that despite increasing mean age (55% of patients are aged > 70 years with associated comorbidities), the morbidity of TURP was < 1% and mortality rate of 0 to 0.3%.47 Postoperative complications include bleeding that requires a transfusion (3%), retrograde ejaculation (65%), and rare urinary incontinence (2%).47 Surgical retreatment rates for patients following a TURP are approximately 13 to 15% at 8 years.34