User login

Pessaries for vaginal prolapse: Critical factors to successful fit and continued use

CASE 1. EARLY-STAGE PELVIC ORGAN PROLAPSE

AC is a 64-year-old white woman with early stage III anterior and apical pelvic organ prolapse (POP). The prolapse is now affecting her ability to do some of the things that she enjoys, such as gardening and golfing.

She has hypertension controlled with medication and no other significant medical issues except mild arthritic changes in her hands and hips. She reports being sexually active with her husband on roughly a weekly basis.

On examination, the leading edge of her prolapse is the anterior vaginal wall, protruding 1 cm beyond the introitus, and the cervix is at the hymenal ring. There is no significant posterior wall prolapse.

After she is counseled about all possible treatment approaches for her early-stage POP, the patient elects to try the vaginal pessary. Now, it is your job to determine the optimal pessary based on the extent of her condition and to educate her about the potential side effects and best practices for its ongoing use.

The vaginal pessary is an important component of a gynecologist’s armamentarium. It is a low-risk, cost-effective, nonsurgical treatment option for the management of POP and genuine stress urinary incontinence (SUI).1,2 It is unfortunate that training in North America typically provides clinicians with only a cursory experience with pessary selection and care, minimizing the device’s importance as a viable tool in a practitioner’s ongoing practice. In fact, most clinicians tend to view the pessary with a mixture of reluctance and disregard.

This is regrettable, as a majority (89%) of patients can be successfully fitted with a pessary,3 regardless of their stage or site of prolapse.4 Although high-stage prolapse does not predict failure, ring pessaries are used most successfully with stage II (100%) and stage III (71%) prolapse, while Gellhorn pessaries are most successful with stage IV (64%) prolapse.5

In this article we review the several pessary options available to clinicians, as well as how to insert them and the best scenarios for their use. We also discuss the key requirements for patient assessment and in-office fitting (meant to optimize the fit and, thereby, the success of use), the possible side effects of pessary use that patients need to be aware of, and appropriate follow-up.

WHEN IS A PESSARY YOUR BEST MANAGEMENT APPROACH?

There are several indications for pessary use,6 namely when:

- the patient has significant comorbid risk factors for surgery

- the patient prefers a nonsurgical alternative

- a goal is to avoid reoperation

- POP or cervical insufficiency is present during pregnancy

- the patient desires future fertility

- surgery must be delayed due to treatment of vaginal ulcerations

- the pessary will be used as a postoperative adjunct to mesh-based repair.

Pessaries have very few contraindications (TABLE). However, factors that do negatively affect successful fitting include:

- prior pelvic surgery

- multiparity

- obesity

- SUI

- short vaginal length (<7 cm)

- wide vaginal introitus (>4 fingerbreadths)

- significant posterior vaginal wall defect.5,7-9

There are two main categories of vaginal pessaries: support and space-filling. All pessaries come in different sizes and shapes. Most are made of medical-grade silicone, rendering them durable and autoclavable as well as resistant to absorption of vaginal discharge and odors. The ring pessary with support is the most commonly used support pessary. The Gellhorn pessary is the most commonly used space-filling pessary. It is used as a second-line treatment for patients unable to retain the ring-with-support pessary.

Related Article: Pessary and pelvic floor exercises for incontinence—are two better than one? G. Willy Davila, MD (Examining the Evidence, May 2010)

SUPPORT PESSARY OPTIONS

The support pessaries are used to treat SUI and POP. These pessaries typically are the easiest types for patients to use because they are more comfortable and simpler to remove and insert than space-filling pessaries. For example, a ring pessary is two-dimensional and lies perpendicular to the long axis of the vagina, allowing patients to have intercourse with it in place. Support-type pessaries include the ring, Gehrung, Shaatz, and lever.

Ring

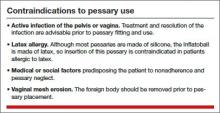

This is the most commonly used pessary because it fits most women. There are four types of ring pessaries: the ring (FIGURE 1A), ring with support (FIGURE 1B), incontinence ring, and incontinence ring with support. The ring pessary is appropriate for all stages of POP. The ring with support has a diaphragm that is useful in women who have uterine prolapse with or without cystocele. The incontinence ring has a knob that is placed beneath the urethra to increase urethral pressure and is useful in cases of SUI.

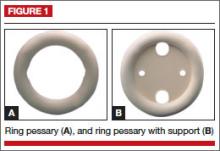

Insertion. Fold the pessary by bringing the two small holes together, and lubricate the leading edge. Insert it past the introitus with the folded edge facing down. Allow the pessary to reopen, and direct it behind the cervix into the posterior fornix (FIGURE 2). Give it a slight twist with your index finger to prevent expulsion.

To see insertion demonstrated, watch Vaginal pessaries: An instructional video

Gehrung

This pessary is designed with an arch-shaped malleable rim with wires incorporated into the arms (FIGURE 3). Use of the Gehrung pessary is rare; it is most often used in women with cystocele or rectocele.

Insertion. Fold the pessary to insert it into the vagina. Upon insertion, keep both heels of the pessary parallel to the posterior vagina with the back arch pushed over the cervix in the anterior fornix and the front arch resting behind the symphysis pubis. The concave surface and diaphragm support the anterior vagina. Place the convex portion of the curve beneath the bulge. The two bases rest on the posterior vagina against the lateral levator muscles.

Shaatz

This support pessary has a circular base similar to the Gellhorn pessary but without the rigid stem (FIGURE 4).

Insertion. Because it is stiff, insert this pessary vertically and then turn it to a horizontal position once it is inside the vagina.

Lever

The Hodge, Smith, and Risser pessaries are collectively called the lever pessaries. They are used to manage uterine retroversion and POP. They are rarely used.

The Hodge pessary is beneficial to patients with a narrow vaginal introitus, mild cystocele, and cervical insufficiency. The anterior portion of a Hodge pessary is rectangular (FIGURE 5A).

The Smith pessary is useful for patients with well-defined pubic notches because the anterior portion is rounded (FIGURE 5B).

For patients with a very shallow pubic notch, the Risser pessary is useful. The Risser’s anterior portion is rectangular with indentation but wider than the Hodge pessary (FIGURE 5C).

Insertion. Fold the pessary and insert it into the vagina with the index finger on the posterior curved bar until the pessary rests behind the cervix and the anterior horizontal bar rests behind the symphysis pubis.

SPACE-OCCUPYING PESSARIES

The second pessary category is the space-filling pessary. These pessaries are used primarily to support severe POP, especially posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse. They have larger bases to support the vaginal apex or cervix; therefore, they are more difficult to insert and remove. When this pessary type is in place, sexual intercourse is not possible. Examples include the Gellhorn, donut, cube, and inflatable pessaries.

Gellhorn

The Gellhorn pessary is the most commonly used space-filling pessary. It has a broad base with a stem (FIGURE 6). The broad base supports the vaginal apex while the stem keeps the circular base from rotating and prevents pessary expulsion. The stem comes in long or short lengths. The concave base provides vaginal suction and keeps the pessary in place. The holes in the stem and base provide vaginal drainage. The Gellhorn pessary is useful for women with more advanced prolapse and less perineal support.

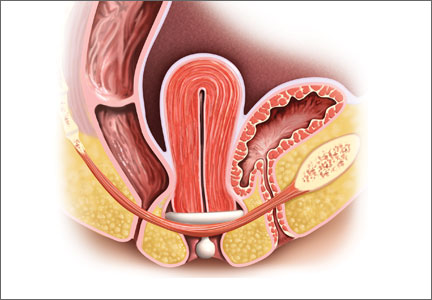

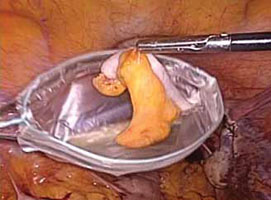

Insertion. Folding one side of the base to the stem, insert the Gellhorn pessary vertically inside the vagina. To facilitate insertion, separate the labia with the nondominant hand or depress the perineum with the index finger. Once the circular base is inside the vagina, push the pessary upward until the tip of the stem is just inside the vaginal introitus (FIGURE 7). Many medical illustrations inaccurately depict the Gellhorn pessary in a final placement that appears too high in the pelvis. This figure, which has the patient in a standing position, shows how low in the pelvis this space-filling pessary can sit in a patient with advanced prolapse.

Remove this pessary by gently pulling the stem while inserting the opposite hand beneath an edge of the pessary base to break the vaginal suction (Watch Vaginal pessaries: An instructional video).

Donut

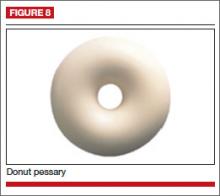

The donut pessary is used for advanced prolapse because it fills a larger space. It is difficult to insert and remove because it is large, thick, and hollow (FIGURE 8).

Insertion. Insert it vertically and, once it is placed inside the vagina, rotate it to a horizontal position. A Kelly clamp can be used to grasp the pessary and facilitate removal.

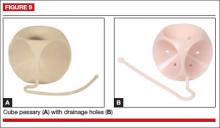

Cube

The cube pessary supports third-degree uterine prolapse by holding the vaginal wall with suction (FIGURE 9). Because of the risk of vaginal erosion and lack of drainage in some designs, the cube pessary requires nightly removal and cleaning.

Insertion. Squeezing the pessary with the thumb, index, and middle fingers, insert the cube pessary at the vaginal apex.

Removal requires breaking the suction by placing a fingertip between the vaginal mucosa and the pessary and compressing the cube between the thumb and forefinger to remove. Gently tugging on the string also helps with removal.

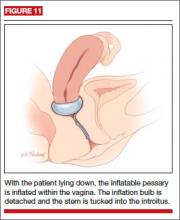

Inflatable

This space-filling pessary is an air-filled ball that is inflated via an attached stem that also enables insertion and removal. The older Inflatoball pessary is made of latex, so its use is contraindicated in patients with latex allergy. Newer inflatable pessaries are silicone-based and consist of an air-filled donut, a stem with a valve, and an air pump (FIGURE 10). Some models also include a deflation key. The inflatable pessary comes in small, medium, large, and extra-large sizes. This pessary type must be removed and cleaned daily.

Insertion. Place the deflated pessary into the vagina. Move the ball-bearing valve within the stem (which controls the air flow) to a lateral projection on the side of the stem. To inflate, attach the inflation bulb. (Inflation typically requires 3 to 5 pumps of the bulb.) Move the ball bearing back into position to maintain the inflation, then detach the bulb. You can leave the stem outside the body or tuck it gently into the introitus (FIGURE 11).

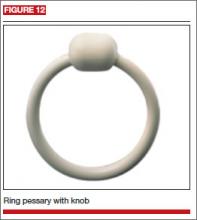

INCONTINENCE PESSARIES

These devices are used specifically for SUI. The incontinence ring (FIGURE 12) and incontinence dish pessaries compress the urethra against the pubic symphysis. The knob is placed beneath the urethra, increasing the urethral closure pressure and thereby preventing urinary incontinence.

Related Article: Update on Urinary Incontinence Karen L. Noblett, MD, MAS, and Stephanie A. Jacobs, MD (December 2011)

CASE 1 CONCLUDED

Given that AC has early-stage POP and is sexually active, a space-occupying pessary is not the optimal choice. Instead, a ring pessary with support is fitted for her trial.

What side effects might a patient anticipate with pessary use?

Vaginal discharge and slight odor are common. Pessary removal and cleaning are usually adequate to eliminate them. Temporary discontinuation of pessary use may be warranted until symptoms subside. If these maneuvers do not resolve the issue, then the patient should be examined to rule out other sources of infection.

Vaginal bleeding. Bleeding from vaginal abrasion and ulceration could be caused by trauma from pessary removal or vaginal impingement. Evaluation is warranted for any vaginal bleeding.

Changes in urinary function. Less commonly, women using a pessary may notice changes in their urinary function. Many women with anterior or apical prolapse will have altered urine streams with slow or trickling flow and possible hesitation upon initiation of voiding.

Alternatively, pessary placement may instigate stress-type incontinence akin to that seen after prolapse surgery. Changing pessary size may alleviate this condition. Otherwise, these side effects may reduce a patient’s willingness to continue pessary use.

How can a patient optimize her use of a pessary?

A patient can remove the pessary on a periodic basis or try to use it continuously. If she cannot or will not remove the pessary, then she will need to come back for scheduled visits, as described in the sidebar, “Essential components of a successfully fitted pessary.” If she is able to remove the pessary on her own, then she can use the device as needed or remove it for intercourse (though it is not necessary). She must remove it weekly, at a minimum, however, to both clean the pessary and give the vaginal walls a “rest,” which can minimize the potential for abrasions or erosions

ESSENTIAL COMPONENTS OF A SUCCESSFULLY FITTED PESSARY

Patient assessment

Accurate selection and placement of a pessary requires appropriate examination and fitting, beginning with determination of the patient’s stage of prolapse and introitus. Key steps include:

– Examine the patient with an empty bladder in the lithotomy position

– Perform bimanual pelvic and speculum examination using a Sims speculum (or bivalve speculum broken in half) with the patient in a supine position

– Administer the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) exam

– Perform digital examination

– Assess vaginal atrophy, vaginal introitus, and vaginal width and length

– Evaluate pelvic floor muscle strength (Kegel squeeze).

Next, gauge the correct pessary size by approximating the number of fingerbreadths accommodated across the vaginal width.

Another method of estimating pessary size is to insert two fingers inside the vagina and estimate the distance between the posterior fornix and the posterior pubic symphysis (Watch Vaginal pessaries: An instructional video). An easy reference is to start with a size 3 or 4 ring pessary if the vaginal introitus is 1 to 2 fingerbreadths in width and the prolapse is stage II to III. If the vagina accommodates 3 to 4 fingerbreadths, or there is stage IV prolapse, use a Gellhorn pessary.

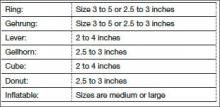

Here are the different types of pessaries and the most common sizes available. (Pessary sizes change in quarter-inch increments.)

In-office trial

Insert the pessary into the vagina using the dominant hand. Using the nondominant hand, separate the introitus and depress the perineal body. Apply a small amount of lubricant to the leading edge of the pessary.

After insertion, ask the patient to strain and cough, ambulate in the office, and void. Reexamine the patient to ensure that the pessary is still in the correct position and that placement has not shifted. Perform the cough leak test with the patient in a standing position and the pessary in place. Re-examine the patient while she is in a standing position. Use the largest pessary that is comfortable for her. Advise her to bring the pessary back to the office if it gets expelled.

This is a trial-and-error process; advise the patient of this. It may require a trial of several styles and sizes to find the right pessary fit. Once you find the correct size, document the final pessary size.

Follow-up

Schedule a follow-up appointment 1 to 2 weeks after insertion. Ask the patient whether she has experienced any discomfort, malodorous discharge, or vaginal bleeding. Also inquire about any changes in urinary habits or bowel movements and related complaints.

Remove the pessary and clean it with mild soap and water. Examine the vagina for pressure points, abrasions, ulcerations, and erosions.

Teach the patient how to remove, clean, and reinsert the pessary, and advise her to perform these tasks on a weekly basis.

Schedule a follow-up visit in 1 to 2 months, and another visit 6 to 12 months after that.

CASE 2. ADVANCED-STAGE POP

BD is an 82-year-old widow (G5P4014) with stage IV vaginal prolapse. She has noticed some scant blood staining on her clothing. She frequently voids small amounts of urine but never feels complete relief. She defecates normally.

Her medical history is significant for coronary artery disease with prior myocardial infarction, with multiple stent placements over the years. She has hypertension, reduced ejection fraction, and diabetes. She is morbidly obese and suffers from degenerative joint disease. She had a vaginal hysterectomy several years ago for benign indications.

Upon examination, BD’s prolapse is large, with excoriations and hyperkeratosis of the skin over the prolapse. It is easily reduced in the office.

What is the best pessary for this patient, and how should she be followed and counseled regarding ongoing care?

Since the failure rate for pessary usage increases with advancing prolapse stage, a space-occupying pessary is most appropriate to try initially. A trial with a support pessary could be useful to allow the excoriations to heal and provide a healthier vaginal environment. A Gellhorn pessary is commonly used. An inflatable pessary could be an alternative if the Gellhorn fails to stay in place. The cube pessary, known to cause more abrasions and erosions than other pessaries, is a poor choice given the state of the patient’s vaginal tissues at baseline.

Space-occupying pessaries are more difficult to insert and remove and have a higher risk of pain or trauma. Start with shorter time intervals between visits, eventually spacing them out for the patient’s convenience. The usual interval for follow-up is 3 to 4 months; longer intervals could be offered if the patient is reliable, adherent, and reports no complaints with pessary use.

Related Article: Update on pelvic floor dysfunction: Focus on urinary incontinence Alexis A. Dieter, MD, and Cindy L. Amundsen, MD (November 2013)

OUTCOMES

Only short- and medium-term outcomes for pessary use have been described in the literature. Short-term (2 months) satisfaction and continued use, along with resolution of prolapse, occurred in 92% of patients.7 Previous hysterectomy or prolapse surgery may influence the short-term success of pessary use.10

More than half of sexually active women achieved long-term use (up to 2 years), regardless of prolapse severity. Brincat and colleagues found that long-term pessary use (1 to 2 years) approached 60% in 132 women with both urinary incontinence and prolapse. Women being treated for POP were more likely to continue pessary use than women being treated for SUI.11 Age, parity, estrogen use, and sexual activity were characteristics also studied in pessary fitting. Neither sexual activity nor stage of prolapse was a contraindication to use of a pessary; long-term use was found to be acceptable in sexually active women.11

Successful fitting of a vaginal pessary has been associated with improvement in voiding, urinary and fecal urgency, and incontinence. A vaginal pessary is a viable nonsurgical option for the management of POP and urinary incontinence and remains an optimal minimally invasive approach to such disorders.

CASE 2 CONCLUDED

The patient returns to the clinic 1 month after the original insertion. The pessary is removed, and the vagina is inspected, with no abrasions or ulcerations found. The vaginal cavity and pessary are cleaned with a mild soap-and-water mixture. The pessary is lubricated and reinserted. This process is repeated 2 months later, with subsequent follow-up intervals doubled (up to 6 months between visits) when the patient has no complaints of discharge or odor.

- Colmer, WM Jr. Use of the pessary. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1953;65(1):170–174.

- Culligan PJ. Nonsurgical management to pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(4):852–860.

- Nygaard IE, Heit M. Stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(3):607–620.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 85: Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(3):717–729.

- Clemons JL, Aguilar VC, Tillinghast TA, Jackson ND, Myers DL. Risk factors associated with an unsuccessful pessary fitting trial in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(2):345–350.

- Clemons JL, Brubaker L, Falk SJ. Vaginal pessary treatment of prolapse and incontinence. UpToDate. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/vaginal-pessary-treatment-of-prolapse-and-incontinence. Updated February 8, 2013. Accessed November 7, 2013.

- Mutone MF, Terry C, Hale DS, Benson JT. Factors which influence the short-term success of pessary management of pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(1):89–94.

- Fernando RJ, Thakar R, Sultan AH, Shah SM, Jones PW. Effect of vaginal pessaries on symptoms associated with pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(1):93–99.

- Weber AM, Richter HE. Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(3):615–634.

- Donnelly MJ, Powell-Morgan S, Olsen AL, et al. Vaginal pessaries for the management of stress and mixed incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2004;15(5):302–307.

- Brincat C, Kenton K, Fitzgerald MP, et al. Sexual activity predicts continued pessary use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(1):198–200.

CASE 1. EARLY-STAGE PELVIC ORGAN PROLAPSE

AC is a 64-year-old white woman with early stage III anterior and apical pelvic organ prolapse (POP). The prolapse is now affecting her ability to do some of the things that she enjoys, such as gardening and golfing.

She has hypertension controlled with medication and no other significant medical issues except mild arthritic changes in her hands and hips. She reports being sexually active with her husband on roughly a weekly basis.

On examination, the leading edge of her prolapse is the anterior vaginal wall, protruding 1 cm beyond the introitus, and the cervix is at the hymenal ring. There is no significant posterior wall prolapse.

After she is counseled about all possible treatment approaches for her early-stage POP, the patient elects to try the vaginal pessary. Now, it is your job to determine the optimal pessary based on the extent of her condition and to educate her about the potential side effects and best practices for its ongoing use.

The vaginal pessary is an important component of a gynecologist’s armamentarium. It is a low-risk, cost-effective, nonsurgical treatment option for the management of POP and genuine stress urinary incontinence (SUI).1,2 It is unfortunate that training in North America typically provides clinicians with only a cursory experience with pessary selection and care, minimizing the device’s importance as a viable tool in a practitioner’s ongoing practice. In fact, most clinicians tend to view the pessary with a mixture of reluctance and disregard.

This is regrettable, as a majority (89%) of patients can be successfully fitted with a pessary,3 regardless of their stage or site of prolapse.4 Although high-stage prolapse does not predict failure, ring pessaries are used most successfully with stage II (100%) and stage III (71%) prolapse, while Gellhorn pessaries are most successful with stage IV (64%) prolapse.5

In this article we review the several pessary options available to clinicians, as well as how to insert them and the best scenarios for their use. We also discuss the key requirements for patient assessment and in-office fitting (meant to optimize the fit and, thereby, the success of use), the possible side effects of pessary use that patients need to be aware of, and appropriate follow-up.

WHEN IS A PESSARY YOUR BEST MANAGEMENT APPROACH?

There are several indications for pessary use,6 namely when:

- the patient has significant comorbid risk factors for surgery

- the patient prefers a nonsurgical alternative

- a goal is to avoid reoperation

- POP or cervical insufficiency is present during pregnancy

- the patient desires future fertility

- surgery must be delayed due to treatment of vaginal ulcerations

- the pessary will be used as a postoperative adjunct to mesh-based repair.

Pessaries have very few contraindications (TABLE). However, factors that do negatively affect successful fitting include:

- prior pelvic surgery

- multiparity

- obesity

- SUI

- short vaginal length (<7 cm)

- wide vaginal introitus (>4 fingerbreadths)

- significant posterior vaginal wall defect.5,7-9

There are two main categories of vaginal pessaries: support and space-filling. All pessaries come in different sizes and shapes. Most are made of medical-grade silicone, rendering them durable and autoclavable as well as resistant to absorption of vaginal discharge and odors. The ring pessary with support is the most commonly used support pessary. The Gellhorn pessary is the most commonly used space-filling pessary. It is used as a second-line treatment for patients unable to retain the ring-with-support pessary.

Related Article: Pessary and pelvic floor exercises for incontinence—are two better than one? G. Willy Davila, MD (Examining the Evidence, May 2010)

SUPPORT PESSARY OPTIONS

The support pessaries are used to treat SUI and POP. These pessaries typically are the easiest types for patients to use because they are more comfortable and simpler to remove and insert than space-filling pessaries. For example, a ring pessary is two-dimensional and lies perpendicular to the long axis of the vagina, allowing patients to have intercourse with it in place. Support-type pessaries include the ring, Gehrung, Shaatz, and lever.

Ring

This is the most commonly used pessary because it fits most women. There are four types of ring pessaries: the ring (FIGURE 1A), ring with support (FIGURE 1B), incontinence ring, and incontinence ring with support. The ring pessary is appropriate for all stages of POP. The ring with support has a diaphragm that is useful in women who have uterine prolapse with or without cystocele. The incontinence ring has a knob that is placed beneath the urethra to increase urethral pressure and is useful in cases of SUI.

Insertion. Fold the pessary by bringing the two small holes together, and lubricate the leading edge. Insert it past the introitus with the folded edge facing down. Allow the pessary to reopen, and direct it behind the cervix into the posterior fornix (FIGURE 2). Give it a slight twist with your index finger to prevent expulsion.

To see insertion demonstrated, watch Vaginal pessaries: An instructional video

Gehrung

This pessary is designed with an arch-shaped malleable rim with wires incorporated into the arms (FIGURE 3). Use of the Gehrung pessary is rare; it is most often used in women with cystocele or rectocele.

Insertion. Fold the pessary to insert it into the vagina. Upon insertion, keep both heels of the pessary parallel to the posterior vagina with the back arch pushed over the cervix in the anterior fornix and the front arch resting behind the symphysis pubis. The concave surface and diaphragm support the anterior vagina. Place the convex portion of the curve beneath the bulge. The two bases rest on the posterior vagina against the lateral levator muscles.

Shaatz

This support pessary has a circular base similar to the Gellhorn pessary but without the rigid stem (FIGURE 4).

Insertion. Because it is stiff, insert this pessary vertically and then turn it to a horizontal position once it is inside the vagina.

Lever

The Hodge, Smith, and Risser pessaries are collectively called the lever pessaries. They are used to manage uterine retroversion and POP. They are rarely used.

The Hodge pessary is beneficial to patients with a narrow vaginal introitus, mild cystocele, and cervical insufficiency. The anterior portion of a Hodge pessary is rectangular (FIGURE 5A).

The Smith pessary is useful for patients with well-defined pubic notches because the anterior portion is rounded (FIGURE 5B).

For patients with a very shallow pubic notch, the Risser pessary is useful. The Risser’s anterior portion is rectangular with indentation but wider than the Hodge pessary (FIGURE 5C).

Insertion. Fold the pessary and insert it into the vagina with the index finger on the posterior curved bar until the pessary rests behind the cervix and the anterior horizontal bar rests behind the symphysis pubis.

SPACE-OCCUPYING PESSARIES

The second pessary category is the space-filling pessary. These pessaries are used primarily to support severe POP, especially posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse. They have larger bases to support the vaginal apex or cervix; therefore, they are more difficult to insert and remove. When this pessary type is in place, sexual intercourse is not possible. Examples include the Gellhorn, donut, cube, and inflatable pessaries.

Gellhorn

The Gellhorn pessary is the most commonly used space-filling pessary. It has a broad base with a stem (FIGURE 6). The broad base supports the vaginal apex while the stem keeps the circular base from rotating and prevents pessary expulsion. The stem comes in long or short lengths. The concave base provides vaginal suction and keeps the pessary in place. The holes in the stem and base provide vaginal drainage. The Gellhorn pessary is useful for women with more advanced prolapse and less perineal support.

Insertion. Folding one side of the base to the stem, insert the Gellhorn pessary vertically inside the vagina. To facilitate insertion, separate the labia with the nondominant hand or depress the perineum with the index finger. Once the circular base is inside the vagina, push the pessary upward until the tip of the stem is just inside the vaginal introitus (FIGURE 7). Many medical illustrations inaccurately depict the Gellhorn pessary in a final placement that appears too high in the pelvis. This figure, which has the patient in a standing position, shows how low in the pelvis this space-filling pessary can sit in a patient with advanced prolapse.

Remove this pessary by gently pulling the stem while inserting the opposite hand beneath an edge of the pessary base to break the vaginal suction (Watch Vaginal pessaries: An instructional video).

Donut

The donut pessary is used for advanced prolapse because it fills a larger space. It is difficult to insert and remove because it is large, thick, and hollow (FIGURE 8).

Insertion. Insert it vertically and, once it is placed inside the vagina, rotate it to a horizontal position. A Kelly clamp can be used to grasp the pessary and facilitate removal.

Cube

The cube pessary supports third-degree uterine prolapse by holding the vaginal wall with suction (FIGURE 9). Because of the risk of vaginal erosion and lack of drainage in some designs, the cube pessary requires nightly removal and cleaning.

Insertion. Squeezing the pessary with the thumb, index, and middle fingers, insert the cube pessary at the vaginal apex.

Removal requires breaking the suction by placing a fingertip between the vaginal mucosa and the pessary and compressing the cube between the thumb and forefinger to remove. Gently tugging on the string also helps with removal.

Inflatable

This space-filling pessary is an air-filled ball that is inflated via an attached stem that also enables insertion and removal. The older Inflatoball pessary is made of latex, so its use is contraindicated in patients with latex allergy. Newer inflatable pessaries are silicone-based and consist of an air-filled donut, a stem with a valve, and an air pump (FIGURE 10). Some models also include a deflation key. The inflatable pessary comes in small, medium, large, and extra-large sizes. This pessary type must be removed and cleaned daily.

Insertion. Place the deflated pessary into the vagina. Move the ball-bearing valve within the stem (which controls the air flow) to a lateral projection on the side of the stem. To inflate, attach the inflation bulb. (Inflation typically requires 3 to 5 pumps of the bulb.) Move the ball bearing back into position to maintain the inflation, then detach the bulb. You can leave the stem outside the body or tuck it gently into the introitus (FIGURE 11).

INCONTINENCE PESSARIES

These devices are used specifically for SUI. The incontinence ring (FIGURE 12) and incontinence dish pessaries compress the urethra against the pubic symphysis. The knob is placed beneath the urethra, increasing the urethral closure pressure and thereby preventing urinary incontinence.

Related Article: Update on Urinary Incontinence Karen L. Noblett, MD, MAS, and Stephanie A. Jacobs, MD (December 2011)

CASE 1 CONCLUDED

Given that AC has early-stage POP and is sexually active, a space-occupying pessary is not the optimal choice. Instead, a ring pessary with support is fitted for her trial.

What side effects might a patient anticipate with pessary use?

Vaginal discharge and slight odor are common. Pessary removal and cleaning are usually adequate to eliminate them. Temporary discontinuation of pessary use may be warranted until symptoms subside. If these maneuvers do not resolve the issue, then the patient should be examined to rule out other sources of infection.

Vaginal bleeding. Bleeding from vaginal abrasion and ulceration could be caused by trauma from pessary removal or vaginal impingement. Evaluation is warranted for any vaginal bleeding.

Changes in urinary function. Less commonly, women using a pessary may notice changes in their urinary function. Many women with anterior or apical prolapse will have altered urine streams with slow or trickling flow and possible hesitation upon initiation of voiding.

Alternatively, pessary placement may instigate stress-type incontinence akin to that seen after prolapse surgery. Changing pessary size may alleviate this condition. Otherwise, these side effects may reduce a patient’s willingness to continue pessary use.

How can a patient optimize her use of a pessary?

A patient can remove the pessary on a periodic basis or try to use it continuously. If she cannot or will not remove the pessary, then she will need to come back for scheduled visits, as described in the sidebar, “Essential components of a successfully fitted pessary.” If she is able to remove the pessary on her own, then she can use the device as needed or remove it for intercourse (though it is not necessary). She must remove it weekly, at a minimum, however, to both clean the pessary and give the vaginal walls a “rest,” which can minimize the potential for abrasions or erosions

ESSENTIAL COMPONENTS OF A SUCCESSFULLY FITTED PESSARY

Patient assessment

Accurate selection and placement of a pessary requires appropriate examination and fitting, beginning with determination of the patient’s stage of prolapse and introitus. Key steps include:

– Examine the patient with an empty bladder in the lithotomy position

– Perform bimanual pelvic and speculum examination using a Sims speculum (or bivalve speculum broken in half) with the patient in a supine position

– Administer the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) exam

– Perform digital examination

– Assess vaginal atrophy, vaginal introitus, and vaginal width and length

– Evaluate pelvic floor muscle strength (Kegel squeeze).

Next, gauge the correct pessary size by approximating the number of fingerbreadths accommodated across the vaginal width.

Another method of estimating pessary size is to insert two fingers inside the vagina and estimate the distance between the posterior fornix and the posterior pubic symphysis (Watch Vaginal pessaries: An instructional video). An easy reference is to start with a size 3 or 4 ring pessary if the vaginal introitus is 1 to 2 fingerbreadths in width and the prolapse is stage II to III. If the vagina accommodates 3 to 4 fingerbreadths, or there is stage IV prolapse, use a Gellhorn pessary.

Here are the different types of pessaries and the most common sizes available. (Pessary sizes change in quarter-inch increments.)

In-office trial

Insert the pessary into the vagina using the dominant hand. Using the nondominant hand, separate the introitus and depress the perineal body. Apply a small amount of lubricant to the leading edge of the pessary.

After insertion, ask the patient to strain and cough, ambulate in the office, and void. Reexamine the patient to ensure that the pessary is still in the correct position and that placement has not shifted. Perform the cough leak test with the patient in a standing position and the pessary in place. Re-examine the patient while she is in a standing position. Use the largest pessary that is comfortable for her. Advise her to bring the pessary back to the office if it gets expelled.

This is a trial-and-error process; advise the patient of this. It may require a trial of several styles and sizes to find the right pessary fit. Once you find the correct size, document the final pessary size.

Follow-up

Schedule a follow-up appointment 1 to 2 weeks after insertion. Ask the patient whether she has experienced any discomfort, malodorous discharge, or vaginal bleeding. Also inquire about any changes in urinary habits or bowel movements and related complaints.

Remove the pessary and clean it with mild soap and water. Examine the vagina for pressure points, abrasions, ulcerations, and erosions.

Teach the patient how to remove, clean, and reinsert the pessary, and advise her to perform these tasks on a weekly basis.

Schedule a follow-up visit in 1 to 2 months, and another visit 6 to 12 months after that.

CASE 2. ADVANCED-STAGE POP

BD is an 82-year-old widow (G5P4014) with stage IV vaginal prolapse. She has noticed some scant blood staining on her clothing. She frequently voids small amounts of urine but never feels complete relief. She defecates normally.

Her medical history is significant for coronary artery disease with prior myocardial infarction, with multiple stent placements over the years. She has hypertension, reduced ejection fraction, and diabetes. She is morbidly obese and suffers from degenerative joint disease. She had a vaginal hysterectomy several years ago for benign indications.

Upon examination, BD’s prolapse is large, with excoriations and hyperkeratosis of the skin over the prolapse. It is easily reduced in the office.

What is the best pessary for this patient, and how should she be followed and counseled regarding ongoing care?

Since the failure rate for pessary usage increases with advancing prolapse stage, a space-occupying pessary is most appropriate to try initially. A trial with a support pessary could be useful to allow the excoriations to heal and provide a healthier vaginal environment. A Gellhorn pessary is commonly used. An inflatable pessary could be an alternative if the Gellhorn fails to stay in place. The cube pessary, known to cause more abrasions and erosions than other pessaries, is a poor choice given the state of the patient’s vaginal tissues at baseline.

Space-occupying pessaries are more difficult to insert and remove and have a higher risk of pain or trauma. Start with shorter time intervals between visits, eventually spacing them out for the patient’s convenience. The usual interval for follow-up is 3 to 4 months; longer intervals could be offered if the patient is reliable, adherent, and reports no complaints with pessary use.

Related Article: Update on pelvic floor dysfunction: Focus on urinary incontinence Alexis A. Dieter, MD, and Cindy L. Amundsen, MD (November 2013)

OUTCOMES

Only short- and medium-term outcomes for pessary use have been described in the literature. Short-term (2 months) satisfaction and continued use, along with resolution of prolapse, occurred in 92% of patients.7 Previous hysterectomy or prolapse surgery may influence the short-term success of pessary use.10

More than half of sexually active women achieved long-term use (up to 2 years), regardless of prolapse severity. Brincat and colleagues found that long-term pessary use (1 to 2 years) approached 60% in 132 women with both urinary incontinence and prolapse. Women being treated for POP were more likely to continue pessary use than women being treated for SUI.11 Age, parity, estrogen use, and sexual activity were characteristics also studied in pessary fitting. Neither sexual activity nor stage of prolapse was a contraindication to use of a pessary; long-term use was found to be acceptable in sexually active women.11

Successful fitting of a vaginal pessary has been associated with improvement in voiding, urinary and fecal urgency, and incontinence. A vaginal pessary is a viable nonsurgical option for the management of POP and urinary incontinence and remains an optimal minimally invasive approach to such disorders.

CASE 2 CONCLUDED

The patient returns to the clinic 1 month after the original insertion. The pessary is removed, and the vagina is inspected, with no abrasions or ulcerations found. The vaginal cavity and pessary are cleaned with a mild soap-and-water mixture. The pessary is lubricated and reinserted. This process is repeated 2 months later, with subsequent follow-up intervals doubled (up to 6 months between visits) when the patient has no complaints of discharge or odor.

CASE 1. EARLY-STAGE PELVIC ORGAN PROLAPSE

AC is a 64-year-old white woman with early stage III anterior and apical pelvic organ prolapse (POP). The prolapse is now affecting her ability to do some of the things that she enjoys, such as gardening and golfing.

She has hypertension controlled with medication and no other significant medical issues except mild arthritic changes in her hands and hips. She reports being sexually active with her husband on roughly a weekly basis.

On examination, the leading edge of her prolapse is the anterior vaginal wall, protruding 1 cm beyond the introitus, and the cervix is at the hymenal ring. There is no significant posterior wall prolapse.

After she is counseled about all possible treatment approaches for her early-stage POP, the patient elects to try the vaginal pessary. Now, it is your job to determine the optimal pessary based on the extent of her condition and to educate her about the potential side effects and best practices for its ongoing use.

The vaginal pessary is an important component of a gynecologist’s armamentarium. It is a low-risk, cost-effective, nonsurgical treatment option for the management of POP and genuine stress urinary incontinence (SUI).1,2 It is unfortunate that training in North America typically provides clinicians with only a cursory experience with pessary selection and care, minimizing the device’s importance as a viable tool in a practitioner’s ongoing practice. In fact, most clinicians tend to view the pessary with a mixture of reluctance and disregard.

This is regrettable, as a majority (89%) of patients can be successfully fitted with a pessary,3 regardless of their stage or site of prolapse.4 Although high-stage prolapse does not predict failure, ring pessaries are used most successfully with stage II (100%) and stage III (71%) prolapse, while Gellhorn pessaries are most successful with stage IV (64%) prolapse.5

In this article we review the several pessary options available to clinicians, as well as how to insert them and the best scenarios for their use. We also discuss the key requirements for patient assessment and in-office fitting (meant to optimize the fit and, thereby, the success of use), the possible side effects of pessary use that patients need to be aware of, and appropriate follow-up.

WHEN IS A PESSARY YOUR BEST MANAGEMENT APPROACH?

There are several indications for pessary use,6 namely when:

- the patient has significant comorbid risk factors for surgery

- the patient prefers a nonsurgical alternative

- a goal is to avoid reoperation

- POP or cervical insufficiency is present during pregnancy

- the patient desires future fertility

- surgery must be delayed due to treatment of vaginal ulcerations

- the pessary will be used as a postoperative adjunct to mesh-based repair.

Pessaries have very few contraindications (TABLE). However, factors that do negatively affect successful fitting include:

- prior pelvic surgery

- multiparity

- obesity

- SUI

- short vaginal length (<7 cm)

- wide vaginal introitus (>4 fingerbreadths)

- significant posterior vaginal wall defect.5,7-9

There are two main categories of vaginal pessaries: support and space-filling. All pessaries come in different sizes and shapes. Most are made of medical-grade silicone, rendering them durable and autoclavable as well as resistant to absorption of vaginal discharge and odors. The ring pessary with support is the most commonly used support pessary. The Gellhorn pessary is the most commonly used space-filling pessary. It is used as a second-line treatment for patients unable to retain the ring-with-support pessary.

Related Article: Pessary and pelvic floor exercises for incontinence—are two better than one? G. Willy Davila, MD (Examining the Evidence, May 2010)

SUPPORT PESSARY OPTIONS

The support pessaries are used to treat SUI and POP. These pessaries typically are the easiest types for patients to use because they are more comfortable and simpler to remove and insert than space-filling pessaries. For example, a ring pessary is two-dimensional and lies perpendicular to the long axis of the vagina, allowing patients to have intercourse with it in place. Support-type pessaries include the ring, Gehrung, Shaatz, and lever.

Ring

This is the most commonly used pessary because it fits most women. There are four types of ring pessaries: the ring (FIGURE 1A), ring with support (FIGURE 1B), incontinence ring, and incontinence ring with support. The ring pessary is appropriate for all stages of POP. The ring with support has a diaphragm that is useful in women who have uterine prolapse with or without cystocele. The incontinence ring has a knob that is placed beneath the urethra to increase urethral pressure and is useful in cases of SUI.

Insertion. Fold the pessary by bringing the two small holes together, and lubricate the leading edge. Insert it past the introitus with the folded edge facing down. Allow the pessary to reopen, and direct it behind the cervix into the posterior fornix (FIGURE 2). Give it a slight twist with your index finger to prevent expulsion.

To see insertion demonstrated, watch Vaginal pessaries: An instructional video

Gehrung

This pessary is designed with an arch-shaped malleable rim with wires incorporated into the arms (FIGURE 3). Use of the Gehrung pessary is rare; it is most often used in women with cystocele or rectocele.

Insertion. Fold the pessary to insert it into the vagina. Upon insertion, keep both heels of the pessary parallel to the posterior vagina with the back arch pushed over the cervix in the anterior fornix and the front arch resting behind the symphysis pubis. The concave surface and diaphragm support the anterior vagina. Place the convex portion of the curve beneath the bulge. The two bases rest on the posterior vagina against the lateral levator muscles.

Shaatz

This support pessary has a circular base similar to the Gellhorn pessary but without the rigid stem (FIGURE 4).

Insertion. Because it is stiff, insert this pessary vertically and then turn it to a horizontal position once it is inside the vagina.

Lever

The Hodge, Smith, and Risser pessaries are collectively called the lever pessaries. They are used to manage uterine retroversion and POP. They are rarely used.

The Hodge pessary is beneficial to patients with a narrow vaginal introitus, mild cystocele, and cervical insufficiency. The anterior portion of a Hodge pessary is rectangular (FIGURE 5A).

The Smith pessary is useful for patients with well-defined pubic notches because the anterior portion is rounded (FIGURE 5B).

For patients with a very shallow pubic notch, the Risser pessary is useful. The Risser’s anterior portion is rectangular with indentation but wider than the Hodge pessary (FIGURE 5C).

Insertion. Fold the pessary and insert it into the vagina with the index finger on the posterior curved bar until the pessary rests behind the cervix and the anterior horizontal bar rests behind the symphysis pubis.

SPACE-OCCUPYING PESSARIES

The second pessary category is the space-filling pessary. These pessaries are used primarily to support severe POP, especially posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse. They have larger bases to support the vaginal apex or cervix; therefore, they are more difficult to insert and remove. When this pessary type is in place, sexual intercourse is not possible. Examples include the Gellhorn, donut, cube, and inflatable pessaries.

Gellhorn

The Gellhorn pessary is the most commonly used space-filling pessary. It has a broad base with a stem (FIGURE 6). The broad base supports the vaginal apex while the stem keeps the circular base from rotating and prevents pessary expulsion. The stem comes in long or short lengths. The concave base provides vaginal suction and keeps the pessary in place. The holes in the stem and base provide vaginal drainage. The Gellhorn pessary is useful for women with more advanced prolapse and less perineal support.

Insertion. Folding one side of the base to the stem, insert the Gellhorn pessary vertically inside the vagina. To facilitate insertion, separate the labia with the nondominant hand or depress the perineum with the index finger. Once the circular base is inside the vagina, push the pessary upward until the tip of the stem is just inside the vaginal introitus (FIGURE 7). Many medical illustrations inaccurately depict the Gellhorn pessary in a final placement that appears too high in the pelvis. This figure, which has the patient in a standing position, shows how low in the pelvis this space-filling pessary can sit in a patient with advanced prolapse.

Remove this pessary by gently pulling the stem while inserting the opposite hand beneath an edge of the pessary base to break the vaginal suction (Watch Vaginal pessaries: An instructional video).

Donut

The donut pessary is used for advanced prolapse because it fills a larger space. It is difficult to insert and remove because it is large, thick, and hollow (FIGURE 8).

Insertion. Insert it vertically and, once it is placed inside the vagina, rotate it to a horizontal position. A Kelly clamp can be used to grasp the pessary and facilitate removal.

Cube

The cube pessary supports third-degree uterine prolapse by holding the vaginal wall with suction (FIGURE 9). Because of the risk of vaginal erosion and lack of drainage in some designs, the cube pessary requires nightly removal and cleaning.

Insertion. Squeezing the pessary with the thumb, index, and middle fingers, insert the cube pessary at the vaginal apex.

Removal requires breaking the suction by placing a fingertip between the vaginal mucosa and the pessary and compressing the cube between the thumb and forefinger to remove. Gently tugging on the string also helps with removal.

Inflatable

This space-filling pessary is an air-filled ball that is inflated via an attached stem that also enables insertion and removal. The older Inflatoball pessary is made of latex, so its use is contraindicated in patients with latex allergy. Newer inflatable pessaries are silicone-based and consist of an air-filled donut, a stem with a valve, and an air pump (FIGURE 10). Some models also include a deflation key. The inflatable pessary comes in small, medium, large, and extra-large sizes. This pessary type must be removed and cleaned daily.

Insertion. Place the deflated pessary into the vagina. Move the ball-bearing valve within the stem (which controls the air flow) to a lateral projection on the side of the stem. To inflate, attach the inflation bulb. (Inflation typically requires 3 to 5 pumps of the bulb.) Move the ball bearing back into position to maintain the inflation, then detach the bulb. You can leave the stem outside the body or tuck it gently into the introitus (FIGURE 11).

INCONTINENCE PESSARIES

These devices are used specifically for SUI. The incontinence ring (FIGURE 12) and incontinence dish pessaries compress the urethra against the pubic symphysis. The knob is placed beneath the urethra, increasing the urethral closure pressure and thereby preventing urinary incontinence.

Related Article: Update on Urinary Incontinence Karen L. Noblett, MD, MAS, and Stephanie A. Jacobs, MD (December 2011)

CASE 1 CONCLUDED

Given that AC has early-stage POP and is sexually active, a space-occupying pessary is not the optimal choice. Instead, a ring pessary with support is fitted for her trial.

What side effects might a patient anticipate with pessary use?

Vaginal discharge and slight odor are common. Pessary removal and cleaning are usually adequate to eliminate them. Temporary discontinuation of pessary use may be warranted until symptoms subside. If these maneuvers do not resolve the issue, then the patient should be examined to rule out other sources of infection.

Vaginal bleeding. Bleeding from vaginal abrasion and ulceration could be caused by trauma from pessary removal or vaginal impingement. Evaluation is warranted for any vaginal bleeding.

Changes in urinary function. Less commonly, women using a pessary may notice changes in their urinary function. Many women with anterior or apical prolapse will have altered urine streams with slow or trickling flow and possible hesitation upon initiation of voiding.

Alternatively, pessary placement may instigate stress-type incontinence akin to that seen after prolapse surgery. Changing pessary size may alleviate this condition. Otherwise, these side effects may reduce a patient’s willingness to continue pessary use.

How can a patient optimize her use of a pessary?

A patient can remove the pessary on a periodic basis or try to use it continuously. If she cannot or will not remove the pessary, then she will need to come back for scheduled visits, as described in the sidebar, “Essential components of a successfully fitted pessary.” If she is able to remove the pessary on her own, then she can use the device as needed or remove it for intercourse (though it is not necessary). She must remove it weekly, at a minimum, however, to both clean the pessary and give the vaginal walls a “rest,” which can minimize the potential for abrasions or erosions

ESSENTIAL COMPONENTS OF A SUCCESSFULLY FITTED PESSARY

Patient assessment

Accurate selection and placement of a pessary requires appropriate examination and fitting, beginning with determination of the patient’s stage of prolapse and introitus. Key steps include:

– Examine the patient with an empty bladder in the lithotomy position

– Perform bimanual pelvic and speculum examination using a Sims speculum (or bivalve speculum broken in half) with the patient in a supine position

– Administer the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) exam

– Perform digital examination

– Assess vaginal atrophy, vaginal introitus, and vaginal width and length

– Evaluate pelvic floor muscle strength (Kegel squeeze).

Next, gauge the correct pessary size by approximating the number of fingerbreadths accommodated across the vaginal width.

Another method of estimating pessary size is to insert two fingers inside the vagina and estimate the distance between the posterior fornix and the posterior pubic symphysis (Watch Vaginal pessaries: An instructional video). An easy reference is to start with a size 3 or 4 ring pessary if the vaginal introitus is 1 to 2 fingerbreadths in width and the prolapse is stage II to III. If the vagina accommodates 3 to 4 fingerbreadths, or there is stage IV prolapse, use a Gellhorn pessary.

Here are the different types of pessaries and the most common sizes available. (Pessary sizes change in quarter-inch increments.)

In-office trial

Insert the pessary into the vagina using the dominant hand. Using the nondominant hand, separate the introitus and depress the perineal body. Apply a small amount of lubricant to the leading edge of the pessary.

After insertion, ask the patient to strain and cough, ambulate in the office, and void. Reexamine the patient to ensure that the pessary is still in the correct position and that placement has not shifted. Perform the cough leak test with the patient in a standing position and the pessary in place. Re-examine the patient while she is in a standing position. Use the largest pessary that is comfortable for her. Advise her to bring the pessary back to the office if it gets expelled.

This is a trial-and-error process; advise the patient of this. It may require a trial of several styles and sizes to find the right pessary fit. Once you find the correct size, document the final pessary size.

Follow-up

Schedule a follow-up appointment 1 to 2 weeks after insertion. Ask the patient whether she has experienced any discomfort, malodorous discharge, or vaginal bleeding. Also inquire about any changes in urinary habits or bowel movements and related complaints.

Remove the pessary and clean it with mild soap and water. Examine the vagina for pressure points, abrasions, ulcerations, and erosions.

Teach the patient how to remove, clean, and reinsert the pessary, and advise her to perform these tasks on a weekly basis.

Schedule a follow-up visit in 1 to 2 months, and another visit 6 to 12 months after that.

CASE 2. ADVANCED-STAGE POP

BD is an 82-year-old widow (G5P4014) with stage IV vaginal prolapse. She has noticed some scant blood staining on her clothing. She frequently voids small amounts of urine but never feels complete relief. She defecates normally.

Her medical history is significant for coronary artery disease with prior myocardial infarction, with multiple stent placements over the years. She has hypertension, reduced ejection fraction, and diabetes. She is morbidly obese and suffers from degenerative joint disease. She had a vaginal hysterectomy several years ago for benign indications.

Upon examination, BD’s prolapse is large, with excoriations and hyperkeratosis of the skin over the prolapse. It is easily reduced in the office.

What is the best pessary for this patient, and how should she be followed and counseled regarding ongoing care?

Since the failure rate for pessary usage increases with advancing prolapse stage, a space-occupying pessary is most appropriate to try initially. A trial with a support pessary could be useful to allow the excoriations to heal and provide a healthier vaginal environment. A Gellhorn pessary is commonly used. An inflatable pessary could be an alternative if the Gellhorn fails to stay in place. The cube pessary, known to cause more abrasions and erosions than other pessaries, is a poor choice given the state of the patient’s vaginal tissues at baseline.

Space-occupying pessaries are more difficult to insert and remove and have a higher risk of pain or trauma. Start with shorter time intervals between visits, eventually spacing them out for the patient’s convenience. The usual interval for follow-up is 3 to 4 months; longer intervals could be offered if the patient is reliable, adherent, and reports no complaints with pessary use.

Related Article: Update on pelvic floor dysfunction: Focus on urinary incontinence Alexis A. Dieter, MD, and Cindy L. Amundsen, MD (November 2013)

OUTCOMES

Only short- and medium-term outcomes for pessary use have been described in the literature. Short-term (2 months) satisfaction and continued use, along with resolution of prolapse, occurred in 92% of patients.7 Previous hysterectomy or prolapse surgery may influence the short-term success of pessary use.10

More than half of sexually active women achieved long-term use (up to 2 years), regardless of prolapse severity. Brincat and colleagues found that long-term pessary use (1 to 2 years) approached 60% in 132 women with both urinary incontinence and prolapse. Women being treated for POP were more likely to continue pessary use than women being treated for SUI.11 Age, parity, estrogen use, and sexual activity were characteristics also studied in pessary fitting. Neither sexual activity nor stage of prolapse was a contraindication to use of a pessary; long-term use was found to be acceptable in sexually active women.11

Successful fitting of a vaginal pessary has been associated with improvement in voiding, urinary and fecal urgency, and incontinence. A vaginal pessary is a viable nonsurgical option for the management of POP and urinary incontinence and remains an optimal minimally invasive approach to such disorders.

CASE 2 CONCLUDED

The patient returns to the clinic 1 month after the original insertion. The pessary is removed, and the vagina is inspected, with no abrasions or ulcerations found. The vaginal cavity and pessary are cleaned with a mild soap-and-water mixture. The pessary is lubricated and reinserted. This process is repeated 2 months later, with subsequent follow-up intervals doubled (up to 6 months between visits) when the patient has no complaints of discharge or odor.

- Colmer, WM Jr. Use of the pessary. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1953;65(1):170–174.

- Culligan PJ. Nonsurgical management to pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(4):852–860.

- Nygaard IE, Heit M. Stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(3):607–620.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 85: Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(3):717–729.

- Clemons JL, Aguilar VC, Tillinghast TA, Jackson ND, Myers DL. Risk factors associated with an unsuccessful pessary fitting trial in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(2):345–350.

- Clemons JL, Brubaker L, Falk SJ. Vaginal pessary treatment of prolapse and incontinence. UpToDate. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/vaginal-pessary-treatment-of-prolapse-and-incontinence. Updated February 8, 2013. Accessed November 7, 2013.

- Mutone MF, Terry C, Hale DS, Benson JT. Factors which influence the short-term success of pessary management of pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(1):89–94.

- Fernando RJ, Thakar R, Sultan AH, Shah SM, Jones PW. Effect of vaginal pessaries on symptoms associated with pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(1):93–99.

- Weber AM, Richter HE. Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(3):615–634.

- Donnelly MJ, Powell-Morgan S, Olsen AL, et al. Vaginal pessaries for the management of stress and mixed incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2004;15(5):302–307.

- Brincat C, Kenton K, Fitzgerald MP, et al. Sexual activity predicts continued pessary use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(1):198–200.

- Colmer, WM Jr. Use of the pessary. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1953;65(1):170–174.

- Culligan PJ. Nonsurgical management to pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(4):852–860.

- Nygaard IE, Heit M. Stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(3):607–620.

- ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 85: Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(3):717–729.

- Clemons JL, Aguilar VC, Tillinghast TA, Jackson ND, Myers DL. Risk factors associated with an unsuccessful pessary fitting trial in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(2):345–350.

- Clemons JL, Brubaker L, Falk SJ. Vaginal pessary treatment of prolapse and incontinence. UpToDate. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/vaginal-pessary-treatment-of-prolapse-and-incontinence. Updated February 8, 2013. Accessed November 7, 2013.

- Mutone MF, Terry C, Hale DS, Benson JT. Factors which influence the short-term success of pessary management of pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(1):89–94.

- Fernando RJ, Thakar R, Sultan AH, Shah SM, Jones PW. Effect of vaginal pessaries on symptoms associated with pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(1):93–99.

- Weber AM, Richter HE. Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(3):615–634.

- Donnelly MJ, Powell-Morgan S, Olsen AL, et al. Vaginal pessaries for the management of stress and mixed incontinence. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2004;15(5):302–307.

- Brincat C, Kenton K, Fitzgerald MP, et al. Sexual activity predicts continued pessary use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(1):198–200.

![]()

Teresa Tam, MD

In this 15-minute video Dr. Tam demonstrates insertion and removal of the ring and Gellhorn pessaries and illustrates proper technique for estimating pessary size.

Elective laparoscopic appendectomy in gynecologic surgery: When, why, and how

Videos provided by Teresa Tam, MD, and Gerald Harkins, MD

CASE: Should appendectomy be included in total

laparoscopic hysterectomy?

A 39-year-old mother of two continues to experience severe dysmenorrhea and persistent menorrhagia despite undergoing endometrial ablation 2 years earlier. Her obstetric and gynecologic history is remarkable for a diagnosis of chronic pelvic pain, endometriosis, and failed endometrial ablation. Both her children were delivered by cesarean, and she has undergone tubal ligation. She requests hysterectomy to address the dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia once and for all.

A pelvic exam reveals an anteverted, 10-weeks’ size uterus with no adnexal masses or tenderness. After extensive discussion of the surgical procedure, the patient signs a consent for total laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Would you recommend appendectomy, too?

Prophylactic removal of the appendix during a benign gynecologic procedure is known as “elective incidental appendectomy.”1 Incidental appendectomy at the time of cesarean delivery was reported initially in 1959.2 Subsequent studies of removal of a normal-appearing appendix at the time of gynecologic surgery have met with considerable debate. Proponents argue that removal of the appendix at the time of abdominal hysterectomy does not increase operative time or postoperative morbidity. More important, it does prevent future appendicitis.3-5

Some surgeons disagree, citing an increase in operative time, hospital costs, and patient morbidity as reasonable concerns. They also note that appendectomy requires an additional surgical procedure, which could increase the risk of infection and other complications and lead to adhesion formation.

Advantages of incidental appendectomy include technical ease, low patient morbidity and mortality, and significant diagnostic and protective value.6 It also prevents conflicting diagnoses, especially in patients who have chronic pelvic pain, a ruptured ovarian cyst, or endometriosis. Other patients likely to benefit from elective incidental appendectomy are those who are undergoing abdominal radiation or chemotherapy, women unable to communicate health complaints, and those who are planning to undergo complex abdominal or pelvic procedures that are likely to cause extensive adhesions.1

In this article, we describe the rationale behind this procedure, as well as the technical steps involved.

The laparoscopic approach is preferred

Appendectomy is commonly performed laparoscopically. Semm first described this approach in 1983.7 Several studies since have reported that incidental laparoscopic appendectomy is safe, easy to perform, and should be offered to patients undergoing a concomitant gynecologic procedure.8-10 Laparoscopic removal of a normal appendix does not add morbidity or prolong hospitalization, compared with diagnostic laparoscopy. A large study drawing from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database found laparoscopic removal of the appendix to be associated with lower mortality, fewer complications, shorter hospitalization, and lower mean hospital charges, compared with open appendectomy.11 The same study found laparoscopic appendectomy to be the procedure of choice in both perforated and nonperforated appendicitis.

Overweight and obese patients also may benefit from the laparoscopic approach because it avoids problems associated with an open incision, such as the need for abdominal wall retraction, a longer hospital stay, and a risk of wound infection, compared with smaller incisions—especially in this high-risk population.12

Cost is another issue. Any prolonged surgical time and higher medical costs required for incidental appendectomy decrease as surgical proficiency and experience rise. The concomitant performance of endoscopic procedures can also reduce the risk associated with anesthesia for reoperations.

Endometriosis patients stand to benefit from appendectomy

There is compelling evidence that elective appendectomy is beneficial in patients who have endometriosis. Endometriosis of the bowel has been reported in 5.3% of all histologically proven endometriosis cases, with appendiceal endometriosis found in approximately 1% of women with endometriosis.13 Despite the low prevalence (2.8%) of appendiceal endometriosis,14 some studies reported a high incidence of appendiceal endometriosis when incidental appendectomy was performed. Patients who report right lower quadrant (RLQ) pain, chronic pelvic pain, and ovarian endometrioma had the highest incidence of abnormal histopathologic findings.15-17 Because most women with endometriosis present with these symptoms, it is prudent to counsel patients preoperatively about the incidence of appendiceal endometriosis and to visually examine the appendix during gynecologic surgery to identify incidental appendiceal pathology.

Age may influence the appendectomy decision

The incidence of acute appendicitis is highest among people aged 10 to 19 years. The estimated lifetime risk of appendicitis is 6.7%.18 The surgical dilemma is whether to perform incidental appendectomy in the nonadolescent population, which is at lower risk for appendicitis, as a preventive measure.

We lack randomized trials on the benefit of incidental appendectomy. A retrospective study of open procedures supported incidental appendectomy in patients younger than 35 years; for patients 35 to 50, the decision was left to the clinical judgment of the surgeon, based on the patient’s clinical condition.4 The same study failed to support incidental appendectomy in women older than 50 years.

When the appendix is not easily accessible, or the surgical complexity of the gynecologic procedure prevents the surgeon from safely performing an appendectomy, it is better to complete the planned gynecologic surgery and forgo the appendectomy. It is acceptable to make the decision to refrain from the appendectomy intraoperatively if the risk of complications outweighs the likely benefits. The practice of cautionary discretion demonstrates sound judgment and avoids compromising the safety of the patient.

1. Maintain at least three laparoscopic sites

- After the laparoscopic gynecologic procedure, maintain three trocar sites—preferably, two 5-mm trocars and one 12-mm trocar.

- The first 5-mm trocar, at the umbilical incision, accommodates the laparoscopic camera. The second 5-mm trocar serves as an accessory port for laparoscopic instruments and is inserted into the RLQ.

- The 12-mm trocar in the left lower quadrant (LLQ) is also used to insert endoscopic instruments. This trocar site will be used at the conclusion of the appendectomy to accommodate the mechanical stapling device and the specimen bag for removal of the excised organ.

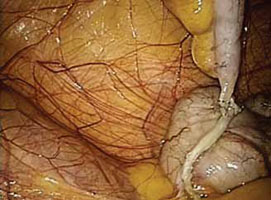

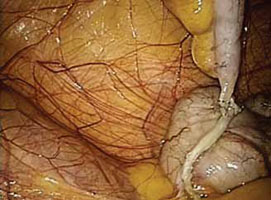

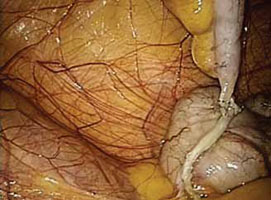

FIGURE 1: Visualize the appendix. Identify the cecum and ileocolic junction to locate the appendix.

2. Identify the appendix

- Perform a careful visual exploration of the abdominal contents to exclude other intra-abdominal pathology.

- Identify the cecum and ileocolic junction to locate the appendix (FIGURE 1).

- Visually inspect the appendix and identify any gross appendiceal pathology.

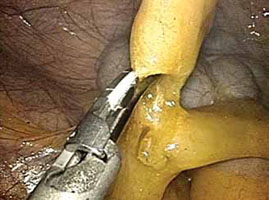

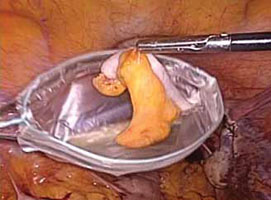

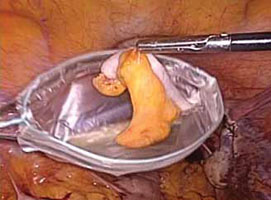

FIGURE 2: Divide the mesoappendix

Isolate, cauterize, and divide the mesoappendix using 5-mm ultrasonic shears.

3. Dissect the appendix (VIDEO 1)

- Insert an atraumatic forceps through the 5-mm right accessory trocar.

- Grasp the fatty tissue at the tip of the appendix and provide some traction.

- Elevate the appendix to facilitate visualization of the mesoappendix.

- Isolate the mesoappendix and cauterize and divide it using 5-mm ultrasonic shears inserted through the RLQ trocar (FIGURE 2).

- Release some of the upward tension from the specimen retraction by dropping the height of the instrument to prevent undue trauma and bleeding.

- Make a window between the mesentery and the base of the appendix to facilitate dissection.

- Skeletonize the mesoappendix at the junction of the appendiceal base and the cecum.

- During skeletonization, pay special attention to the appendiceal artery at the base of the mesoappendix.

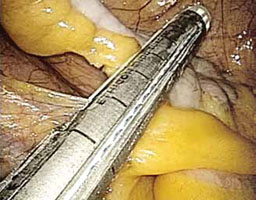

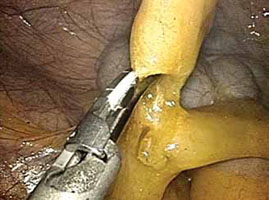

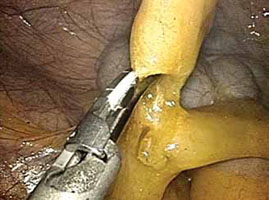

FIGURE 3: Apply the stapling device

Apply the stapling device across the base of the appendix.

4. Resect the appendix (VIDEO 2)

- Insert an automatic stapling device through the 12-mm port and apply it across the base of the appendix (FIGURE 3).

- Apply the mechanical stapling device for 15 seconds to crush the base of the appendix and empty its contents.

- Visualize both sides of the stapler to ensure that it is placed at the base of the appendix.

- Always check the tip of the device to ensure that the jaws of the stapling device fully compress the appendix and have not inadvertently grasped other abdominal contents.

- With the stapling device compressing the base of the appendix, release some of the upward tension on the specimen by dropping the height of the retraction.

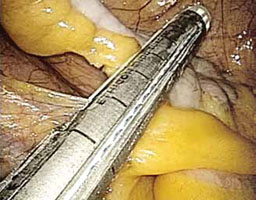

- Activate the stapling device and completely excise the appendix from its base

(FIGURE 4). - Thoroughly inspect the appendiceal stump to ensure hemostasis (FIGURE 5).

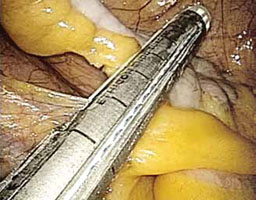

FIGURE 4: Excise the appendix

Activate the stapling device and completely excise the appendix from its base.

FIGURE 5: Ensure hemostasis

Thoroughly inspect the appendiceal stump and ensure hemostasis.

5. Remove the specimen (VIDEO 3)

- Remove the stapling device and replace it with a specimen retrieval bag, inserting it through the 12-mm port.

- Place the amputated appendix in the specimen retrieval bag to prevent abdominal contamination (FIGURE 6).

- Close the specimen retrieval bag inside the abdomen.

- Refrain from removing the specimen bag through the trocar or forcefully passing the appendix through a small incision. We usually withdraw the 12-mm trocar, then remove the cinched bag containing the resected appendix under direct visualization. We take all precautionary measures to prevent breakage of the bag, which would leak appendiceal contents into the abdomen.

FIGURE 6: Remove the specimen

Place the amputated appendix in the specimen retrieval bag and remove it, intact, through the patient’s abdomen.

6. Perform a few last measures

- If the surgeon chooses, suction and irrigation can be performed at the completion of the appendectomy procedure.

- Send all surgical specimens to pathology for evaluation.

- Complete the operation in the usual laparoscopic fashion. Remove all instruments, and close the 12-mm trocar port site using the Carter Thomason fascial closure device. Close the remaining port sites using 2-0 interrupted suture (Monocryl). Apply skin adhesive to all laparoscopic incisions.

- For more on surgical technique of appendectomy, see Baggish,19 Jaffe and Berger,20 and Daniell and colleagues.21

Coding for appendectomy is fairly straightforward if you know the rules, but prophylactic removal of the appendix, whether performed at the time of a laparoscopic or open abdominal primary procedure, will usually lead to reimbursement difficulties for surgeons even though CPT codes exist to report the procedure. Knowing when and how to bill and document the circumstances for removal will go a long way in getting payment for the procedure. Note that these rules apply to a single surgeon who is performing the entire surgery. When an ObGyn is performing gyn procedures, but a general surgeon is the one who removes the appendix, that surgeon will not be subject to bundling rules, but will still have to make a case with the payer for removing an otherwise normal appendix.

There are 5 codes that can be used to report an appendectomy:

- 44950 Appendectomy;

- 44955 Appendectomy; when done for indicated purpose at time of other major procedure (not as separate procedure)

- 44960 Appendectomy; for ruptured appendix with abscess or generalized peritonitis

- 44970 Laparoscopy, surgical, appendectomy code

- 44979, Unlisted laparoscopy procedure, appendix.

Code 44950 represents either a stand-alone procedure or an incidental appendectomy when performed with other open abdominal procedures. Under CPT guidelines this code would only be reported 1) when this is the only procedure performed and the appendix is removed for a diagnosis other than rupture with abscess, or 2) with a modifier -52 added if the surgeon believes that an incidental appendectomy needs to be reported. Use of a modifier -52 will lead to review of the documentation by the payer, and it will be up to the surgeon to convince the payer that he should be paid for taking out an appendix that is found to be normal. Billing 44950 with other abdominal procedures without this modifier will lead to an outright denial due to bundling edits, which permanently bundle 44950 with all major abdominal procedures.