User login

Assessing and treating depression in palliative care patients

Depression is highly prevalent in hospice and palliative care settings—especially among cancer patients, in whom the prevalence of depression may be 4 times that of the general population.1 Furthermore, suicide is a relatively common, unwanted consequence of depression among cancer patients.2 Whereas the risk of suicide among advanced cancer patients may be twice that of the general population,3 in specific cancer populations (male patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma) the risk of suicide may be 11 times that of the general population.4

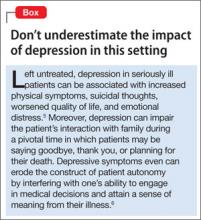

Mental health professionals often are consulted when treating depressed patients with advanced illness, especially when suicidal thoughts or wishes for a hastened death are expressed to oncologists or primary care physicians. To mitigate the effects of depression among seriously ill patients (Box),5,6 mental health professionals must be able to assess and manage depression in patients with progressive, incurable illnesses such as advanced malignancy.

Diagnostic challenges

Assessing depression in seriously ill patients can be a challenge for mental health professionals. Cardinal neurovegetative symptoms of depression, such as anergia, anorexia, impaired concentration, and sleep disturbances, also are common manifestations of advanced medical illness.7 Furthermore, it can be difficult to gauge the significance of psychological distress among cancer patients. Although depressive thoughts and symptoms may be present in 15% to 50% of cancer patients, only 5% to 20% will meet diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD).8,9 You may find it challenging to determine whether to use pharmacotherapy for depressive symptoms or whether engaging in reflective listening and exploring the patient’s concerns is the appropriate therapeutic intervention.

Side effects from commonly used therapeutics for cancer patients—chemotherapeutic agents, opioids, benzodiazepines, glucocorticoids—can mimic depressive symptoms. Clinicians should include hypoactive delirium in the differential diagnosis of depressive symptoms in cancer patients. Delirium is an important consideration in the final days of life because the condition has been shown to occur in as many as 90% of these patients.10 A mistaken diagnosis of depression in a patient who has hypoactive delirium (see “Hospitalized, elderly, and delirious: What should you do for these patients?” page 10) might lead to a prescription for an antidepressant or a psychostimulant, which can exacerbate delirium rather than alleviate depressive symptoms.

Significant attitudinal barriers from both clinicians and patients can lead to under-

recognition and undertreatment of depression. Clinicians may believe the patient’s depression is an appropriate response to the dying process; indeed, feeling sad or depressed may be an appropriate response to bad news or a medical setback, but meeting MDD criteria should be viewed as a pathologic process that has adverse medical, psychological, and social consequences. Time constraints or personal discomfort with existential concerns may prevent a clinician from exploring a patient’s distress out of fear that such discussions may cause the patient to become more depressed.11 Patients may underreport or consciously disguise depressive symptoms in their final weeks of life.12

Responding to these challenges

The Science Committee of the Association of Palliative Medicine performed a thorough assessment of available screening tools and rating scales for depressive symptoms in palliative care. Although the committee found that commonly used tools such as the Edinburgh Depression Scale and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale have validated cutoff thresholds for palliative care patients, the depression screening tool with the highest sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value was the question: “Are you feeling down, depressed, or hopeless most of the time over the last 2 weeks?”13,14

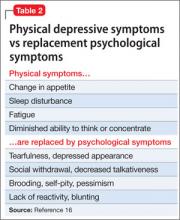

Other short screening algorithms have been validated among palliative care patients (Table 1).15 Endicott proposed a structured approach to help clinicians differentiate MDD from common physical ailments of progressive cancer in which physical criteria for an MDD diagnosis are substituted by affective symptoms (Table 2).16 The improved risk-benefit ratio of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), coupled with the potential significant morbidity associated with MDD and subsyndromal depressive symptoms, makes it necessary to recognize and treat those symptoms even when the cause of the depressive symptoms is unclear.

Psychotherapy in palliative care

Psychotherapeutic interventions such as dignity therapy, which invites patients to utilize a meaning-centered life review to address his (her) existential concerns, may help depressed palliative care patients.17 Evidence suggests a strong association between diminished dignity and depression in patients with advanced illness.18 Individualized psychotherapeutic interventions that provide a framework for addressing dignity-related issues and existential distress among terminally ill patients could help preserve a sense of purpose throughout the dying process. Surveys of dignity therapy have been encouraging: 91% of participants reported being satisfied with dignity therapy and more than two-thirds reported an improved sense of meaning.18

Other promising psychotherapeutic interventions include supportive-expressed group therapy, in which a group of advanced cancer patients meets with a mental health professional and discusses goals of building bonds, refining life’s priorities, and “detoxifying” the experience of death and dying.19 A primary purpose of this therapy is not just to foster improved relationships within a group of cancer patients, but also within their family and oncology team, with the aim of improving compliance with anticancer therapies. Nurse-delivered, one-on-one sessions focusing on depression education, problem-solving, coping techniques, and telecare management of pain and depression also improves outcomes among depressed cancer patients.20

Hospital-based inpatient and outpatient palliative care consultation teams are becoming more common. A randomized controlled trial of early palliative care outpatient consultation for patients with incurable lung cancer showed improved depression outcomes, better quality of life, and a modest improvement in survival.21 Although the most effective elements of a palliative care consult remain unspecified and require further research, improvement in outcomes may result from more effective symptom management, better acknowledgement of the burden of illness on the patient or family, or reduced need for hospitalization. Therefore, mental health professionals should consider palliative care consultation for advanced cancer patients with signs of psychological distress.

Pharmacotherapy options

Antidepressants. Patients with excessive guilt, anhedonia, hopelessness, or ruminative thinking along with a related impairment in quality of life may benefit from pharmacotherapy regardless of whether they meet diagnostic criteria for MDD. Although SSRIs and SNRIs have become a mainstay in managing depression, placebo-controlled trials have yielded mixed results in depressed cancer patients. Furthermore, differences in efficacy among these antidepressants may not be significant, according to a recent meta-analysis.22

Select an antidepressant based on the patient’s past treatment response, target symptoms, and potential for adverse events. Mirtazapine has relatively few drug interactions; the side effects of sedation and weight gain may be welcome among patients with insomnia and impaired appetite.23 Furthermore, mirtazapine is a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist,24 which suggests it might act as an effective antiemetic.25 Other SNRIs, such as venlafaxine and duloxetine, have demonstrated benefits in managing neuropathic pain in patients who do not have cancer.26

Psychostimulants. Patients with a prognosis of days or weeks might not have enough time for an antidepressant to achieve full effect. Open prospective trials and pilot studies have shown that psychostimulants can improve cancer-related fatigue and quality of life while also augmenting the action of antidepressants.27 Psychostimulants, such as methylphenidate, have been used for treating cancer-related fatigue and depressive symptoms in medically ill patients. Their rapid onset of action, coupled with minimal side effect profile, make them a good choice for seriously ill patients with significant neurovegetative symptoms of a depressive disorder. Note: Avoid psychostimulants in patients with delirium and use with caution in patients with heart disease.28

Novel agents. A growing body of preclinical research suggests that glutamate may be involved in the pathophysiology of MDD. Ketamine modulates glutamate neurotransmission as an N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonist. A recent evaluation of a single dose IV of ketamine in a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial found that depressed patients receiving ketamine experienced significant improvement their depressive symptoms.29 Irwin and Iglewicz30 describe 2 hospice patients administered a single oral dose of ketamine, which provided rapid relief of depressive symptoms and was well tolerated.

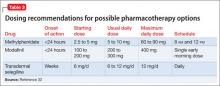

Transdermal selegiline may help patients who have trouble taking oral medications, including antidepressants. Inability to tolerate or absorb medications may be related to several conditions such as head and neck cancer, severe mucositis, and dysphagia. The dose-related dietary requirements—tyramine restriction—and careful monitoring for drug interactions may limit the use of selegiline in medically ill patients.31Table 3 features a list of dosing recommendations for pharmacotherapeutic options.32

Use the strategy of “start low, go slow” when initiating and adjusting antidepressants because patients with cancer and other advanced illnesses often have concomitant organ failure and are at risk of drug interactions. Carefully review your patient’s medication list for agents that are no longer beneficial or possibly contributing to depressive symptoms to help reduce the risk of adverse pharmacokinetic and pharmaco-dynamic interactions.

Requests for a hastened death

As many as 8.5% of terminally ill patients have a sustained and pervasive wish for an early death.33 Although requests for a hastened death may evoke strong emotional reactions and compel many clinicians to recoil or harshly reject such requests, consider such requests as an opportunity to gain insight into the patient’s narrative of his (her) suffering. The clinician’s role in such cases is to identify suicidality and perform a thorough suicide risk assessment. Interventions to prevent suicide should attempt to balance the seriousness of self-harm threats with restrictions on the patient’s liberty.34

Clinicians also need to consider the patient’s prognosis in their decision-making. For example, an extremely depressed or suicidal patient may not benefit from psychiatric hospitalization if she (he) has progressive neurovegetative symptoms and a prognosis of only a few weeks to live. These situations often are challenging and require a careful, informed discussion of the risks and benefits of all proposed interventions.

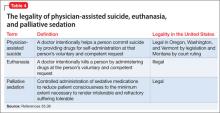

Clinicians also should be familiar with distinctions among ethical issues in end-of-life care, including physician-assisted suicide, euthanasia, and palliative sedation (Table 4).35,36

In Oregon, requests for physician-assisted suicide and hastened death through the state’s Death with Dignity Act often are short lived, and may not persist when clinicians offer patients good symptom management and psychological support.37 Requests for a hastened death often are motivated by loss of control, inability to find meaning in death, indignity from being dependent, and concern for future suffering and burden on loved ones.37

Carefully evaluate requests for hastened death in a manner that balances your personal and professional integrity. To preserve personal integrity, clearly communicate therapeutic interventions that you can and cannot provide. To ensure the patient does not feel abandoned, identify factors that contribute to the patient’s suffering and express a desire to search for alternative care approaches that will be mutually acceptable to the patient and to you.

Advance care planning and palliative care consultations may help in these circumstances. A randomized trial comparing advance care planning vs standard care in hospitalized geriatric patients found that advance care planning was more likely to lead to end-of-life wishes that were recognized by clinicians, and was associated with less distress, anxiety, and depression as reported by bereaved family members.38

Clinicians can assist patients with advanced care planning by helping them fill out advance directives, such as durable health care power of attorney documents and a living will. Palliative care clinicians can offer specialty-level assistance in advance care planning, provide focused assessments of physical and psychosocial symptoms, develop appropriate clinical goals, and assist in coordinating individualized care plans for seriously ill patients.2

Bottom Line

Depression commonly is encountered in hospice and palliative care patients and is associated with morbidity and distress. Validated screening tools can help you distinguish major depressive disorder from depressive symptoms in this population. Several psychotherapeutic techniques have been shown to be beneficial. In addition to traditional antidepressants, psychostimulants or ketamine may help address acute depressive symptoms in patients who have days or weeks to live.

Related Resources

- American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. www.aahpm.org.

- Death with Dignity National Center. www.deathwithdignity.org.

- National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. www.nhpco.org.

- Oregon Health Authority. Death with Dignity Act. http://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/Evaluationresearch/deathwithdignityact/Pages/index.aspx.

Drug Brand Names

Duloxetine • Cymbalta Modafinil • Provigil

Ketamine • Ketalar Selegiline (transdermal) • EMSAM

Methylphenidate • Concerta, Ritalin Mirtazipine • Remeron

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Irwin SA, Rao S, Bower K, et al. Psychiatric issues in palliative care: recognition of depression in patients enrolled in hospice care. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(2):158-163.

2. Misono S, Weiss NS, Fann JR, et al. Incidence of suicide in persons with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(29):4731-4738.

3. Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, et al. Depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death in terminally ill patients with cancer. JAMA. 2000;284(22):2907-2911.

4. Turaga KK, Malafa MP, Jacobsen PB, et al. Suicide in patients with pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(3):642-647.

5. Rosenstein DL. Depression and end-of-life care for patients with cancer. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13(1):101-108.

6. King DA, Heisel MJ, Lyness JM. Assessment and psychological treatment of depression in older adults with terminal or life-threatening illness. Clin Psychol (New York). 2005;12(3):339-353.

7. Block SD. Assessing and managing depression in the terminally ill patient. ACP-ASIM End-of-Life Care Consensus Panel. American College of Physicians - American Society of Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(3):209-218.

8. Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, et al. Prevalence of depression in the terminally ill: effects of diagnostic criteria and symptom threshold judgments. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(4):537-540.

9. Massie MJ. Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;(32):57-71.

10. Spiller JA, Keen JC. Hypoactive delirium: assessing the extent of the problem for inpatient specialist palliative care. Palliat Med. 2006;20(1):17-23.

11. Maguire P. Improving the detection of psychiatric problems in cancer patients. Soc Sci Med. 1985;20(8):819-823.

12. Hinton J. Can home care maintain an acceptable quality of life for patients with terminal cancer and their relatives? Palliat Med. 1994;8(3):183-196.

13. Lloyd-Williams M, Spiller J, Ward J. Which depression screening tools should be used in palliative care? Palliat Med. 2003;17(1):40-43.

14. Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, et al. “Are you depressed?” Screening for depression in the terminally ill. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(5):674-676.

15. Robinson JA, Crawford GB. Identifying palliative care patients with symptoms of depression: an algorithm. Palliat Med. 2005;19(4):278-287.

16. Endicott J. Measurement of depression in patients with cancer. Cancer. 1984;53(10 suppl):2243-2249.

17. Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, et al. Dignity therapy: a novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(24):5520-5525.

18. Chochinov HM. Dignity-conserving care-a new model for palliative care: helping the patient feel valued. JAMA. 2002;287(17):2253-2260.

19. Kissane DW, Grabsch B, Clarke DM, et al. Supportive-expressive group therapy: the transformation of existential ambivalence into creative living while enhancing adherence to anti-cancer therapies. Psychooncology. 2004;13(11):

755-768.

20. Strong V, Waters R, Hibberd C, et al. Management of depression for people with cancer (SMaRT oncology 1): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9632):40-48.

21. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-742.

22. Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Morgan LC, et al. Comparative benefits and harms of second-generation antidepressants for treating major depressive disorder: an updated meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(11):772-785.

23. Kast RE, Foley KF. Cancer chemotherapy and cachexia: mirtazapine and olanzapine are 5-HT3 antagonists with good antinausea effects. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2007; 16(4):351-354.

24. Anttila SA, Leinonen EV. A review of the pharmacological and clinical profile of mirtazapine. CNS Drug Rev. 2001; 7(3):249-264.

25. Pae CU. Low-dose mirtazapine may be successful treatment option for severe nausea and vomiting. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30(6):

1143-1145.

26. Saarto T, Wiffen PJ. Antidepressants for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD005454.

27. Pereira J, Bruera E. Depression with psychomotor retardation: diagnostic challenges and the use of psychostimulants. J Palliat Med. 2001;4(1):15-21.

28. Jackson V, Block S. # 061 Use of Psycho-Stimulants in Palliative Care, 2nd ed. End of Life/Palliative Education Resource Center. Medical College of Wisconsin. http://www.eperc.mcw.edu/EPERC/FastFactsIndex/ff_061.htm. Accessed December 28, 2012.

29. Berman RM, Cappiello A, Anand A, et al. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47(4):351-354.

30. Irwin SA, Iglewicz A. Oral ketamine for the rapid treatment of depression and anxiety in patients receiving hospice care. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(7):903-908.

31. Attard A, Ranjith G, Taylor D. Alternative routes to oral antidepressant therapy: case vignette and literature review. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(4):449-454.

32. Rozans M, Dreisbach A, Lertora JJ, et al. Palliative uses of methylphenidate in patients with cancer: a review. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(1):335-339.

33. Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, et al. Desire for death in the terminally ill. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(8):1185-1191.

34. Marks S, Heinrich TW, Rosielle D. Case report: are clinicians obligated to medically treat a suicide attempt in a patient with a prognosis of weeks? J Palliat Med. 2012;15(1):134-137.

35. Materstvedt LJ, Clark D, Ellershaw J, et al. Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: a view from an EAPC Ethics Task Force. Palliat Med. 2003;17(2):97-101; discussion 102-179.

36. Kirk TW, Mahon MM; Palliative Sedation Task Force of the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization Ethics Committee. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) position statement and commentary on the use of palliative sedation in imminently dying terminally ill patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010; 39(5):914-923.

37. Okie S. Physician-assisted suicide--Oregon and beyond. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(16):1627-1630.

38. Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, et al. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c134

Depression is highly prevalent in hospice and palliative care settings—especially among cancer patients, in whom the prevalence of depression may be 4 times that of the general population.1 Furthermore, suicide is a relatively common, unwanted consequence of depression among cancer patients.2 Whereas the risk of suicide among advanced cancer patients may be twice that of the general population,3 in specific cancer populations (male patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma) the risk of suicide may be 11 times that of the general population.4

Mental health professionals often are consulted when treating depressed patients with advanced illness, especially when suicidal thoughts or wishes for a hastened death are expressed to oncologists or primary care physicians. To mitigate the effects of depression among seriously ill patients (Box),5,6 mental health professionals must be able to assess and manage depression in patients with progressive, incurable illnesses such as advanced malignancy.

Diagnostic challenges

Assessing depression in seriously ill patients can be a challenge for mental health professionals. Cardinal neurovegetative symptoms of depression, such as anergia, anorexia, impaired concentration, and sleep disturbances, also are common manifestations of advanced medical illness.7 Furthermore, it can be difficult to gauge the significance of psychological distress among cancer patients. Although depressive thoughts and symptoms may be present in 15% to 50% of cancer patients, only 5% to 20% will meet diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD).8,9 You may find it challenging to determine whether to use pharmacotherapy for depressive symptoms or whether engaging in reflective listening and exploring the patient’s concerns is the appropriate therapeutic intervention.

Side effects from commonly used therapeutics for cancer patients—chemotherapeutic agents, opioids, benzodiazepines, glucocorticoids—can mimic depressive symptoms. Clinicians should include hypoactive delirium in the differential diagnosis of depressive symptoms in cancer patients. Delirium is an important consideration in the final days of life because the condition has been shown to occur in as many as 90% of these patients.10 A mistaken diagnosis of depression in a patient who has hypoactive delirium (see “Hospitalized, elderly, and delirious: What should you do for these patients?” page 10) might lead to a prescription for an antidepressant or a psychostimulant, which can exacerbate delirium rather than alleviate depressive symptoms.

Significant attitudinal barriers from both clinicians and patients can lead to under-

recognition and undertreatment of depression. Clinicians may believe the patient’s depression is an appropriate response to the dying process; indeed, feeling sad or depressed may be an appropriate response to bad news or a medical setback, but meeting MDD criteria should be viewed as a pathologic process that has adverse medical, psychological, and social consequences. Time constraints or personal discomfort with existential concerns may prevent a clinician from exploring a patient’s distress out of fear that such discussions may cause the patient to become more depressed.11 Patients may underreport or consciously disguise depressive symptoms in their final weeks of life.12

Responding to these challenges

The Science Committee of the Association of Palliative Medicine performed a thorough assessment of available screening tools and rating scales for depressive symptoms in palliative care. Although the committee found that commonly used tools such as the Edinburgh Depression Scale and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale have validated cutoff thresholds for palliative care patients, the depression screening tool with the highest sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value was the question: “Are you feeling down, depressed, or hopeless most of the time over the last 2 weeks?”13,14

Other short screening algorithms have been validated among palliative care patients (Table 1).15 Endicott proposed a structured approach to help clinicians differentiate MDD from common physical ailments of progressive cancer in which physical criteria for an MDD diagnosis are substituted by affective symptoms (Table 2).16 The improved risk-benefit ratio of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), coupled with the potential significant morbidity associated with MDD and subsyndromal depressive symptoms, makes it necessary to recognize and treat those symptoms even when the cause of the depressive symptoms is unclear.

Psychotherapy in palliative care

Psychotherapeutic interventions such as dignity therapy, which invites patients to utilize a meaning-centered life review to address his (her) existential concerns, may help depressed palliative care patients.17 Evidence suggests a strong association between diminished dignity and depression in patients with advanced illness.18 Individualized psychotherapeutic interventions that provide a framework for addressing dignity-related issues and existential distress among terminally ill patients could help preserve a sense of purpose throughout the dying process. Surveys of dignity therapy have been encouraging: 91% of participants reported being satisfied with dignity therapy and more than two-thirds reported an improved sense of meaning.18

Other promising psychotherapeutic interventions include supportive-expressed group therapy, in which a group of advanced cancer patients meets with a mental health professional and discusses goals of building bonds, refining life’s priorities, and “detoxifying” the experience of death and dying.19 A primary purpose of this therapy is not just to foster improved relationships within a group of cancer patients, but also within their family and oncology team, with the aim of improving compliance with anticancer therapies. Nurse-delivered, one-on-one sessions focusing on depression education, problem-solving, coping techniques, and telecare management of pain and depression also improves outcomes among depressed cancer patients.20

Hospital-based inpatient and outpatient palliative care consultation teams are becoming more common. A randomized controlled trial of early palliative care outpatient consultation for patients with incurable lung cancer showed improved depression outcomes, better quality of life, and a modest improvement in survival.21 Although the most effective elements of a palliative care consult remain unspecified and require further research, improvement in outcomes may result from more effective symptom management, better acknowledgement of the burden of illness on the patient or family, or reduced need for hospitalization. Therefore, mental health professionals should consider palliative care consultation for advanced cancer patients with signs of psychological distress.

Pharmacotherapy options

Antidepressants. Patients with excessive guilt, anhedonia, hopelessness, or ruminative thinking along with a related impairment in quality of life may benefit from pharmacotherapy regardless of whether they meet diagnostic criteria for MDD. Although SSRIs and SNRIs have become a mainstay in managing depression, placebo-controlled trials have yielded mixed results in depressed cancer patients. Furthermore, differences in efficacy among these antidepressants may not be significant, according to a recent meta-analysis.22

Select an antidepressant based on the patient’s past treatment response, target symptoms, and potential for adverse events. Mirtazapine has relatively few drug interactions; the side effects of sedation and weight gain may be welcome among patients with insomnia and impaired appetite.23 Furthermore, mirtazapine is a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist,24 which suggests it might act as an effective antiemetic.25 Other SNRIs, such as venlafaxine and duloxetine, have demonstrated benefits in managing neuropathic pain in patients who do not have cancer.26

Psychostimulants. Patients with a prognosis of days or weeks might not have enough time for an antidepressant to achieve full effect. Open prospective trials and pilot studies have shown that psychostimulants can improve cancer-related fatigue and quality of life while also augmenting the action of antidepressants.27 Psychostimulants, such as methylphenidate, have been used for treating cancer-related fatigue and depressive symptoms in medically ill patients. Their rapid onset of action, coupled with minimal side effect profile, make them a good choice for seriously ill patients with significant neurovegetative symptoms of a depressive disorder. Note: Avoid psychostimulants in patients with delirium and use with caution in patients with heart disease.28

Novel agents. A growing body of preclinical research suggests that glutamate may be involved in the pathophysiology of MDD. Ketamine modulates glutamate neurotransmission as an N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonist. A recent evaluation of a single dose IV of ketamine in a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial found that depressed patients receiving ketamine experienced significant improvement their depressive symptoms.29 Irwin and Iglewicz30 describe 2 hospice patients administered a single oral dose of ketamine, which provided rapid relief of depressive symptoms and was well tolerated.

Transdermal selegiline may help patients who have trouble taking oral medications, including antidepressants. Inability to tolerate or absorb medications may be related to several conditions such as head and neck cancer, severe mucositis, and dysphagia. The dose-related dietary requirements—tyramine restriction—and careful monitoring for drug interactions may limit the use of selegiline in medically ill patients.31Table 3 features a list of dosing recommendations for pharmacotherapeutic options.32

Use the strategy of “start low, go slow” when initiating and adjusting antidepressants because patients with cancer and other advanced illnesses often have concomitant organ failure and are at risk of drug interactions. Carefully review your patient’s medication list for agents that are no longer beneficial or possibly contributing to depressive symptoms to help reduce the risk of adverse pharmacokinetic and pharmaco-dynamic interactions.

Requests for a hastened death

As many as 8.5% of terminally ill patients have a sustained and pervasive wish for an early death.33 Although requests for a hastened death may evoke strong emotional reactions and compel many clinicians to recoil or harshly reject such requests, consider such requests as an opportunity to gain insight into the patient’s narrative of his (her) suffering. The clinician’s role in such cases is to identify suicidality and perform a thorough suicide risk assessment. Interventions to prevent suicide should attempt to balance the seriousness of self-harm threats with restrictions on the patient’s liberty.34

Clinicians also need to consider the patient’s prognosis in their decision-making. For example, an extremely depressed or suicidal patient may not benefit from psychiatric hospitalization if she (he) has progressive neurovegetative symptoms and a prognosis of only a few weeks to live. These situations often are challenging and require a careful, informed discussion of the risks and benefits of all proposed interventions.

Clinicians also should be familiar with distinctions among ethical issues in end-of-life care, including physician-assisted suicide, euthanasia, and palliative sedation (Table 4).35,36

In Oregon, requests for physician-assisted suicide and hastened death through the state’s Death with Dignity Act often are short lived, and may not persist when clinicians offer patients good symptom management and psychological support.37 Requests for a hastened death often are motivated by loss of control, inability to find meaning in death, indignity from being dependent, and concern for future suffering and burden on loved ones.37

Carefully evaluate requests for hastened death in a manner that balances your personal and professional integrity. To preserve personal integrity, clearly communicate therapeutic interventions that you can and cannot provide. To ensure the patient does not feel abandoned, identify factors that contribute to the patient’s suffering and express a desire to search for alternative care approaches that will be mutually acceptable to the patient and to you.

Advance care planning and palliative care consultations may help in these circumstances. A randomized trial comparing advance care planning vs standard care in hospitalized geriatric patients found that advance care planning was more likely to lead to end-of-life wishes that were recognized by clinicians, and was associated with less distress, anxiety, and depression as reported by bereaved family members.38

Clinicians can assist patients with advanced care planning by helping them fill out advance directives, such as durable health care power of attorney documents and a living will. Palliative care clinicians can offer specialty-level assistance in advance care planning, provide focused assessments of physical and psychosocial symptoms, develop appropriate clinical goals, and assist in coordinating individualized care plans for seriously ill patients.2

Bottom Line

Depression commonly is encountered in hospice and palliative care patients and is associated with morbidity and distress. Validated screening tools can help you distinguish major depressive disorder from depressive symptoms in this population. Several psychotherapeutic techniques have been shown to be beneficial. In addition to traditional antidepressants, psychostimulants or ketamine may help address acute depressive symptoms in patients who have days or weeks to live.

Related Resources

- American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. www.aahpm.org.

- Death with Dignity National Center. www.deathwithdignity.org.

- National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. www.nhpco.org.

- Oregon Health Authority. Death with Dignity Act. http://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/Evaluationresearch/deathwithdignityact/Pages/index.aspx.

Drug Brand Names

Duloxetine • Cymbalta Modafinil • Provigil

Ketamine • Ketalar Selegiline (transdermal) • EMSAM

Methylphenidate • Concerta, Ritalin Mirtazipine • Remeron

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Depression is highly prevalent in hospice and palliative care settings—especially among cancer patients, in whom the prevalence of depression may be 4 times that of the general population.1 Furthermore, suicide is a relatively common, unwanted consequence of depression among cancer patients.2 Whereas the risk of suicide among advanced cancer patients may be twice that of the general population,3 in specific cancer populations (male patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma) the risk of suicide may be 11 times that of the general population.4

Mental health professionals often are consulted when treating depressed patients with advanced illness, especially when suicidal thoughts or wishes for a hastened death are expressed to oncologists or primary care physicians. To mitigate the effects of depression among seriously ill patients (Box),5,6 mental health professionals must be able to assess and manage depression in patients with progressive, incurable illnesses such as advanced malignancy.

Diagnostic challenges

Assessing depression in seriously ill patients can be a challenge for mental health professionals. Cardinal neurovegetative symptoms of depression, such as anergia, anorexia, impaired concentration, and sleep disturbances, also are common manifestations of advanced medical illness.7 Furthermore, it can be difficult to gauge the significance of psychological distress among cancer patients. Although depressive thoughts and symptoms may be present in 15% to 50% of cancer patients, only 5% to 20% will meet diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD).8,9 You may find it challenging to determine whether to use pharmacotherapy for depressive symptoms or whether engaging in reflective listening and exploring the patient’s concerns is the appropriate therapeutic intervention.

Side effects from commonly used therapeutics for cancer patients—chemotherapeutic agents, opioids, benzodiazepines, glucocorticoids—can mimic depressive symptoms. Clinicians should include hypoactive delirium in the differential diagnosis of depressive symptoms in cancer patients. Delirium is an important consideration in the final days of life because the condition has been shown to occur in as many as 90% of these patients.10 A mistaken diagnosis of depression in a patient who has hypoactive delirium (see “Hospitalized, elderly, and delirious: What should you do for these patients?” page 10) might lead to a prescription for an antidepressant or a psychostimulant, which can exacerbate delirium rather than alleviate depressive symptoms.

Significant attitudinal barriers from both clinicians and patients can lead to under-

recognition and undertreatment of depression. Clinicians may believe the patient’s depression is an appropriate response to the dying process; indeed, feeling sad or depressed may be an appropriate response to bad news or a medical setback, but meeting MDD criteria should be viewed as a pathologic process that has adverse medical, psychological, and social consequences. Time constraints or personal discomfort with existential concerns may prevent a clinician from exploring a patient’s distress out of fear that such discussions may cause the patient to become more depressed.11 Patients may underreport or consciously disguise depressive symptoms in their final weeks of life.12

Responding to these challenges

The Science Committee of the Association of Palliative Medicine performed a thorough assessment of available screening tools and rating scales for depressive symptoms in palliative care. Although the committee found that commonly used tools such as the Edinburgh Depression Scale and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale have validated cutoff thresholds for palliative care patients, the depression screening tool with the highest sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value was the question: “Are you feeling down, depressed, or hopeless most of the time over the last 2 weeks?”13,14

Other short screening algorithms have been validated among palliative care patients (Table 1).15 Endicott proposed a structured approach to help clinicians differentiate MDD from common physical ailments of progressive cancer in which physical criteria for an MDD diagnosis are substituted by affective symptoms (Table 2).16 The improved risk-benefit ratio of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), coupled with the potential significant morbidity associated with MDD and subsyndromal depressive symptoms, makes it necessary to recognize and treat those symptoms even when the cause of the depressive symptoms is unclear.

Psychotherapy in palliative care

Psychotherapeutic interventions such as dignity therapy, which invites patients to utilize a meaning-centered life review to address his (her) existential concerns, may help depressed palliative care patients.17 Evidence suggests a strong association between diminished dignity and depression in patients with advanced illness.18 Individualized psychotherapeutic interventions that provide a framework for addressing dignity-related issues and existential distress among terminally ill patients could help preserve a sense of purpose throughout the dying process. Surveys of dignity therapy have been encouraging: 91% of participants reported being satisfied with dignity therapy and more than two-thirds reported an improved sense of meaning.18

Other promising psychotherapeutic interventions include supportive-expressed group therapy, in which a group of advanced cancer patients meets with a mental health professional and discusses goals of building bonds, refining life’s priorities, and “detoxifying” the experience of death and dying.19 A primary purpose of this therapy is not just to foster improved relationships within a group of cancer patients, but also within their family and oncology team, with the aim of improving compliance with anticancer therapies. Nurse-delivered, one-on-one sessions focusing on depression education, problem-solving, coping techniques, and telecare management of pain and depression also improves outcomes among depressed cancer patients.20

Hospital-based inpatient and outpatient palliative care consultation teams are becoming more common. A randomized controlled trial of early palliative care outpatient consultation for patients with incurable lung cancer showed improved depression outcomes, better quality of life, and a modest improvement in survival.21 Although the most effective elements of a palliative care consult remain unspecified and require further research, improvement in outcomes may result from more effective symptom management, better acknowledgement of the burden of illness on the patient or family, or reduced need for hospitalization. Therefore, mental health professionals should consider palliative care consultation for advanced cancer patients with signs of psychological distress.

Pharmacotherapy options

Antidepressants. Patients with excessive guilt, anhedonia, hopelessness, or ruminative thinking along with a related impairment in quality of life may benefit from pharmacotherapy regardless of whether they meet diagnostic criteria for MDD. Although SSRIs and SNRIs have become a mainstay in managing depression, placebo-controlled trials have yielded mixed results in depressed cancer patients. Furthermore, differences in efficacy among these antidepressants may not be significant, according to a recent meta-analysis.22

Select an antidepressant based on the patient’s past treatment response, target symptoms, and potential for adverse events. Mirtazapine has relatively few drug interactions; the side effects of sedation and weight gain may be welcome among patients with insomnia and impaired appetite.23 Furthermore, mirtazapine is a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist,24 which suggests it might act as an effective antiemetic.25 Other SNRIs, such as venlafaxine and duloxetine, have demonstrated benefits in managing neuropathic pain in patients who do not have cancer.26

Psychostimulants. Patients with a prognosis of days or weeks might not have enough time for an antidepressant to achieve full effect. Open prospective trials and pilot studies have shown that psychostimulants can improve cancer-related fatigue and quality of life while also augmenting the action of antidepressants.27 Psychostimulants, such as methylphenidate, have been used for treating cancer-related fatigue and depressive symptoms in medically ill patients. Their rapid onset of action, coupled with minimal side effect profile, make them a good choice for seriously ill patients with significant neurovegetative symptoms of a depressive disorder. Note: Avoid psychostimulants in patients with delirium and use with caution in patients with heart disease.28

Novel agents. A growing body of preclinical research suggests that glutamate may be involved in the pathophysiology of MDD. Ketamine modulates glutamate neurotransmission as an N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonist. A recent evaluation of a single dose IV of ketamine in a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial found that depressed patients receiving ketamine experienced significant improvement their depressive symptoms.29 Irwin and Iglewicz30 describe 2 hospice patients administered a single oral dose of ketamine, which provided rapid relief of depressive symptoms and was well tolerated.

Transdermal selegiline may help patients who have trouble taking oral medications, including antidepressants. Inability to tolerate or absorb medications may be related to several conditions such as head and neck cancer, severe mucositis, and dysphagia. The dose-related dietary requirements—tyramine restriction—and careful monitoring for drug interactions may limit the use of selegiline in medically ill patients.31Table 3 features a list of dosing recommendations for pharmacotherapeutic options.32

Use the strategy of “start low, go slow” when initiating and adjusting antidepressants because patients with cancer and other advanced illnesses often have concomitant organ failure and are at risk of drug interactions. Carefully review your patient’s medication list for agents that are no longer beneficial or possibly contributing to depressive symptoms to help reduce the risk of adverse pharmacokinetic and pharmaco-dynamic interactions.

Requests for a hastened death

As many as 8.5% of terminally ill patients have a sustained and pervasive wish for an early death.33 Although requests for a hastened death may evoke strong emotional reactions and compel many clinicians to recoil or harshly reject such requests, consider such requests as an opportunity to gain insight into the patient’s narrative of his (her) suffering. The clinician’s role in such cases is to identify suicidality and perform a thorough suicide risk assessment. Interventions to prevent suicide should attempt to balance the seriousness of self-harm threats with restrictions on the patient’s liberty.34

Clinicians also need to consider the patient’s prognosis in their decision-making. For example, an extremely depressed or suicidal patient may not benefit from psychiatric hospitalization if she (he) has progressive neurovegetative symptoms and a prognosis of only a few weeks to live. These situations often are challenging and require a careful, informed discussion of the risks and benefits of all proposed interventions.

Clinicians also should be familiar with distinctions among ethical issues in end-of-life care, including physician-assisted suicide, euthanasia, and palliative sedation (Table 4).35,36

In Oregon, requests for physician-assisted suicide and hastened death through the state’s Death with Dignity Act often are short lived, and may not persist when clinicians offer patients good symptom management and psychological support.37 Requests for a hastened death often are motivated by loss of control, inability to find meaning in death, indignity from being dependent, and concern for future suffering and burden on loved ones.37

Carefully evaluate requests for hastened death in a manner that balances your personal and professional integrity. To preserve personal integrity, clearly communicate therapeutic interventions that you can and cannot provide. To ensure the patient does not feel abandoned, identify factors that contribute to the patient’s suffering and express a desire to search for alternative care approaches that will be mutually acceptable to the patient and to you.

Advance care planning and palliative care consultations may help in these circumstances. A randomized trial comparing advance care planning vs standard care in hospitalized geriatric patients found that advance care planning was more likely to lead to end-of-life wishes that were recognized by clinicians, and was associated with less distress, anxiety, and depression as reported by bereaved family members.38

Clinicians can assist patients with advanced care planning by helping them fill out advance directives, such as durable health care power of attorney documents and a living will. Palliative care clinicians can offer specialty-level assistance in advance care planning, provide focused assessments of physical and psychosocial symptoms, develop appropriate clinical goals, and assist in coordinating individualized care plans for seriously ill patients.2

Bottom Line

Depression commonly is encountered in hospice and palliative care patients and is associated with morbidity and distress. Validated screening tools can help you distinguish major depressive disorder from depressive symptoms in this population. Several psychotherapeutic techniques have been shown to be beneficial. In addition to traditional antidepressants, psychostimulants or ketamine may help address acute depressive symptoms in patients who have days or weeks to live.

Related Resources

- American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. www.aahpm.org.

- Death with Dignity National Center. www.deathwithdignity.org.

- National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. www.nhpco.org.

- Oregon Health Authority. Death with Dignity Act. http://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/Evaluationresearch/deathwithdignityact/Pages/index.aspx.

Drug Brand Names

Duloxetine • Cymbalta Modafinil • Provigil

Ketamine • Ketalar Selegiline (transdermal) • EMSAM

Methylphenidate • Concerta, Ritalin Mirtazipine • Remeron

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Irwin SA, Rao S, Bower K, et al. Psychiatric issues in palliative care: recognition of depression in patients enrolled in hospice care. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(2):158-163.

2. Misono S, Weiss NS, Fann JR, et al. Incidence of suicide in persons with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(29):4731-4738.

3. Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, et al. Depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death in terminally ill patients with cancer. JAMA. 2000;284(22):2907-2911.

4. Turaga KK, Malafa MP, Jacobsen PB, et al. Suicide in patients with pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(3):642-647.

5. Rosenstein DL. Depression and end-of-life care for patients with cancer. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13(1):101-108.

6. King DA, Heisel MJ, Lyness JM. Assessment and psychological treatment of depression in older adults with terminal or life-threatening illness. Clin Psychol (New York). 2005;12(3):339-353.

7. Block SD. Assessing and managing depression in the terminally ill patient. ACP-ASIM End-of-Life Care Consensus Panel. American College of Physicians - American Society of Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(3):209-218.

8. Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, et al. Prevalence of depression in the terminally ill: effects of diagnostic criteria and symptom threshold judgments. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(4):537-540.

9. Massie MJ. Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;(32):57-71.

10. Spiller JA, Keen JC. Hypoactive delirium: assessing the extent of the problem for inpatient specialist palliative care. Palliat Med. 2006;20(1):17-23.

11. Maguire P. Improving the detection of psychiatric problems in cancer patients. Soc Sci Med. 1985;20(8):819-823.

12. Hinton J. Can home care maintain an acceptable quality of life for patients with terminal cancer and their relatives? Palliat Med. 1994;8(3):183-196.

13. Lloyd-Williams M, Spiller J, Ward J. Which depression screening tools should be used in palliative care? Palliat Med. 2003;17(1):40-43.

14. Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, et al. “Are you depressed?” Screening for depression in the terminally ill. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(5):674-676.

15. Robinson JA, Crawford GB. Identifying palliative care patients with symptoms of depression: an algorithm. Palliat Med. 2005;19(4):278-287.

16. Endicott J. Measurement of depression in patients with cancer. Cancer. 1984;53(10 suppl):2243-2249.

17. Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, et al. Dignity therapy: a novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(24):5520-5525.

18. Chochinov HM. Dignity-conserving care-a new model for palliative care: helping the patient feel valued. JAMA. 2002;287(17):2253-2260.

19. Kissane DW, Grabsch B, Clarke DM, et al. Supportive-expressive group therapy: the transformation of existential ambivalence into creative living while enhancing adherence to anti-cancer therapies. Psychooncology. 2004;13(11):

755-768.

20. Strong V, Waters R, Hibberd C, et al. Management of depression for people with cancer (SMaRT oncology 1): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9632):40-48.

21. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-742.

22. Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Morgan LC, et al. Comparative benefits and harms of second-generation antidepressants for treating major depressive disorder: an updated meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(11):772-785.

23. Kast RE, Foley KF. Cancer chemotherapy and cachexia: mirtazapine and olanzapine are 5-HT3 antagonists with good antinausea effects. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2007; 16(4):351-354.

24. Anttila SA, Leinonen EV. A review of the pharmacological and clinical profile of mirtazapine. CNS Drug Rev. 2001; 7(3):249-264.

25. Pae CU. Low-dose mirtazapine may be successful treatment option for severe nausea and vomiting. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30(6):

1143-1145.

26. Saarto T, Wiffen PJ. Antidepressants for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD005454.

27. Pereira J, Bruera E. Depression with psychomotor retardation: diagnostic challenges and the use of psychostimulants. J Palliat Med. 2001;4(1):15-21.

28. Jackson V, Block S. # 061 Use of Psycho-Stimulants in Palliative Care, 2nd ed. End of Life/Palliative Education Resource Center. Medical College of Wisconsin. http://www.eperc.mcw.edu/EPERC/FastFactsIndex/ff_061.htm. Accessed December 28, 2012.

29. Berman RM, Cappiello A, Anand A, et al. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47(4):351-354.

30. Irwin SA, Iglewicz A. Oral ketamine for the rapid treatment of depression and anxiety in patients receiving hospice care. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(7):903-908.

31. Attard A, Ranjith G, Taylor D. Alternative routes to oral antidepressant therapy: case vignette and literature review. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(4):449-454.

32. Rozans M, Dreisbach A, Lertora JJ, et al. Palliative uses of methylphenidate in patients with cancer: a review. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(1):335-339.

33. Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, et al. Desire for death in the terminally ill. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(8):1185-1191.

34. Marks S, Heinrich TW, Rosielle D. Case report: are clinicians obligated to medically treat a suicide attempt in a patient with a prognosis of weeks? J Palliat Med. 2012;15(1):134-137.

35. Materstvedt LJ, Clark D, Ellershaw J, et al. Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: a view from an EAPC Ethics Task Force. Palliat Med. 2003;17(2):97-101; discussion 102-179.

36. Kirk TW, Mahon MM; Palliative Sedation Task Force of the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization Ethics Committee. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) position statement and commentary on the use of palliative sedation in imminently dying terminally ill patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010; 39(5):914-923.

37. Okie S. Physician-assisted suicide--Oregon and beyond. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(16):1627-1630.

38. Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, et al. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c134

1. Irwin SA, Rao S, Bower K, et al. Psychiatric issues in palliative care: recognition of depression in patients enrolled in hospice care. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(2):158-163.

2. Misono S, Weiss NS, Fann JR, et al. Incidence of suicide in persons with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(29):4731-4738.

3. Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, et al. Depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death in terminally ill patients with cancer. JAMA. 2000;284(22):2907-2911.

4. Turaga KK, Malafa MP, Jacobsen PB, et al. Suicide in patients with pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2011;117(3):642-647.

5. Rosenstein DL. Depression and end-of-life care for patients with cancer. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13(1):101-108.

6. King DA, Heisel MJ, Lyness JM. Assessment and psychological treatment of depression in older adults with terminal or life-threatening illness. Clin Psychol (New York). 2005;12(3):339-353.

7. Block SD. Assessing and managing depression in the terminally ill patient. ACP-ASIM End-of-Life Care Consensus Panel. American College of Physicians - American Society of Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(3):209-218.

8. Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, et al. Prevalence of depression in the terminally ill: effects of diagnostic criteria and symptom threshold judgments. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(4):537-540.

9. Massie MJ. Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;(32):57-71.

10. Spiller JA, Keen JC. Hypoactive delirium: assessing the extent of the problem for inpatient specialist palliative care. Palliat Med. 2006;20(1):17-23.

11. Maguire P. Improving the detection of psychiatric problems in cancer patients. Soc Sci Med. 1985;20(8):819-823.

12. Hinton J. Can home care maintain an acceptable quality of life for patients with terminal cancer and their relatives? Palliat Med. 1994;8(3):183-196.

13. Lloyd-Williams M, Spiller J, Ward J. Which depression screening tools should be used in palliative care? Palliat Med. 2003;17(1):40-43.

14. Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, et al. “Are you depressed?” Screening for depression in the terminally ill. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(5):674-676.

15. Robinson JA, Crawford GB. Identifying palliative care patients with symptoms of depression: an algorithm. Palliat Med. 2005;19(4):278-287.

16. Endicott J. Measurement of depression in patients with cancer. Cancer. 1984;53(10 suppl):2243-2249.

17. Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, et al. Dignity therapy: a novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(24):5520-5525.

18. Chochinov HM. Dignity-conserving care-a new model for palliative care: helping the patient feel valued. JAMA. 2002;287(17):2253-2260.

19. Kissane DW, Grabsch B, Clarke DM, et al. Supportive-expressive group therapy: the transformation of existential ambivalence into creative living while enhancing adherence to anti-cancer therapies. Psychooncology. 2004;13(11):

755-768.

20. Strong V, Waters R, Hibberd C, et al. Management of depression for people with cancer (SMaRT oncology 1): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9632):40-48.

21. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-742.

22. Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Morgan LC, et al. Comparative benefits and harms of second-generation antidepressants for treating major depressive disorder: an updated meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(11):772-785.

23. Kast RE, Foley KF. Cancer chemotherapy and cachexia: mirtazapine and olanzapine are 5-HT3 antagonists with good antinausea effects. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2007; 16(4):351-354.

24. Anttila SA, Leinonen EV. A review of the pharmacological and clinical profile of mirtazapine. CNS Drug Rev. 2001; 7(3):249-264.

25. Pae CU. Low-dose mirtazapine may be successful treatment option for severe nausea and vomiting. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30(6):

1143-1145.

26. Saarto T, Wiffen PJ. Antidepressants for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD005454.

27. Pereira J, Bruera E. Depression with psychomotor retardation: diagnostic challenges and the use of psychostimulants. J Palliat Med. 2001;4(1):15-21.

28. Jackson V, Block S. # 061 Use of Psycho-Stimulants in Palliative Care, 2nd ed. End of Life/Palliative Education Resource Center. Medical College of Wisconsin. http://www.eperc.mcw.edu/EPERC/FastFactsIndex/ff_061.htm. Accessed December 28, 2012.

29. Berman RM, Cappiello A, Anand A, et al. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47(4):351-354.

30. Irwin SA, Iglewicz A. Oral ketamine for the rapid treatment of depression and anxiety in patients receiving hospice care. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(7):903-908.

31. Attard A, Ranjith G, Taylor D. Alternative routes to oral antidepressant therapy: case vignette and literature review. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(4):449-454.

32. Rozans M, Dreisbach A, Lertora JJ, et al. Palliative uses of methylphenidate in patients with cancer: a review. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(1):335-339.

33. Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, et al. Desire for death in the terminally ill. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(8):1185-1191.

34. Marks S, Heinrich TW, Rosielle D. Case report: are clinicians obligated to medically treat a suicide attempt in a patient with a prognosis of weeks? J Palliat Med. 2012;15(1):134-137.

35. Materstvedt LJ, Clark D, Ellershaw J, et al. Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: a view from an EAPC Ethics Task Force. Palliat Med. 2003;17(2):97-101; discussion 102-179.

36. Kirk TW, Mahon MM; Palliative Sedation Task Force of the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization Ethics Committee. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) position statement and commentary on the use of palliative sedation in imminently dying terminally ill patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010; 39(5):914-923.

37. Okie S. Physician-assisted suicide--Oregon and beyond. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(16):1627-1630.

38. Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, et al. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c134