User login

A “no-biopsy” approach to diagnosing celiac disease

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 43-year-old woman presents to the clinic with diffuse, intermittent abdominal discomfort, bloating, and diarrhea that has slowly but steadily worsened over the past few years to now-daily symptoms. She states her overall health is otherwise good. Her review of systems is pertinent only for 8 lbs of unintentional weight loss over the past year and increased fatigue. She takes no supplements or routine over-the-counter or prescription medications, except for low-dose combination oral contraceptives, and is unaware of any family history of gastrointestinal (GI) diseases. She does not drink or smoke. She is up to date with immunizations and with cervical and breast cancer screening. Her body mass index is 23, her vital signs are within normal limits, and her physical exam is normal except for mild, diffuse abdominal tenderness without any masses, organomegaly, or peritoneal signs.

Her diagnostic work-up includes a complete metabolic panel, magnesium level, complete blood count, thyroid-stimulating hormone measurement, cytomegalovirus IgG and IgM serology, and stool studies for fecal leukocytes, ova and parasites, and fecal fat, in addition to a kidney, ureter, and bladder noncontrast computed tomography scan. All diagnostic testing is negative except for slightly elevated fecal fat, thereby decreasing the likelihood of infection, thyroid disorder, electrolyte abnormalities, or malignancy as a source of her symptoms.

She says that based on her online searches, her symptoms seem consistent with CD—with which you concur. However, she is fearful of an endoscopic procedure and asks if there is any other way to diagnose CD.

CD is an immune-mediated disorder in genetically susceptible people that is triggered by dietary gluten, causing damage to the small intestine.1-6 The estimated worldwide prevalence of CD is approximately 1%, with greater prevalence in females.1-6 A strong genetic predisposition also has been noted: prevalence among first-degree relatives is 10% to 44%.2,3,6 Although CD can be diagnosed at any age, in the United States the mean age at diagnosis is in the fifth decade of life.6

The incidence of CD is on the rise due to true increases in disease incidence and prevalence, increased detection through better diagnostic tools, and increased screening of at-risk populations (eg, first-degree relatives, those with specific human leukocyte antigen variant genotypes, and those with certain chromosomal disorders, such as Down syndrome and Turner syndrome).2-6 However, despite the increasing prevalence of CD, most patients remain undiagnosed.1

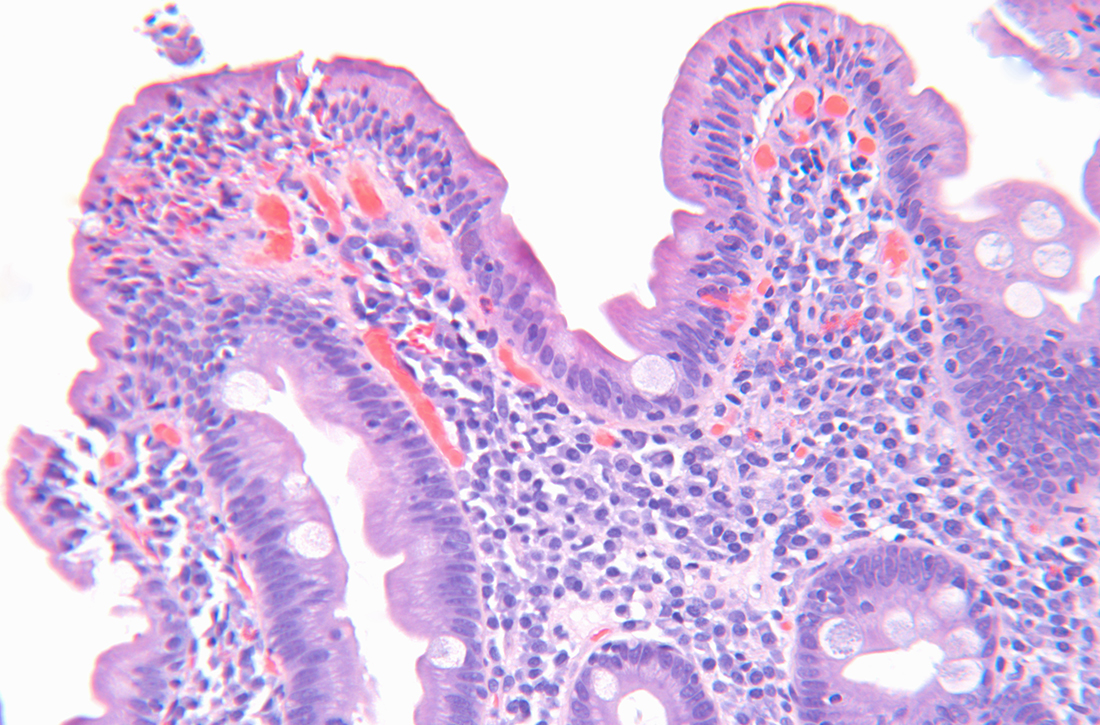

The diagnosis of CD in adults is typically made with elevated serum tTG-IgA and

STUDY SUMMARY

tTG-IgA titers were highly predictive of CD in 3 distinct cohorts

This 2021 hybrid prospective/retrospective study with 3 distinct cohorts aimed to assess the utility of serum tTG-IgA titers compared to traditional EGD with duodenal biopsy for the diagnosis of CD in adult participants (defined as ≥ 16 years of age). A serum tTG-IgA titer ≥ 10 times the ULN was set as the minimal cutoff value, and standardized duodenal biopsy sampling and evaluation for histologic mucosal changes consistent with

Continue to: Cohort 1 was a...

Cohort 1 was a prospective analysis of adults (N = 740) considered to have a high suspicion for CD, recruited from a single CD subspecialty clinic in the United Kingdom. Patients with a previous diagnosis of CD, those adhering to a gluten-free diet, and those with IgA deficiency were excluded. Study patients had tTG-IgA titers drawn and, within 6 weeks, underwent endoscopy with ≥ 1 biopsy from the duodenal bulb and/or the second part of the duodenum. The PPV of tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN in patients with biopsy-proven CD was 98.7% (95% CI, 97%-99.4%).

Cohort 2 was a retrospective analysis of adult patients (N = 532) considered to have low suspicion for CD. These patients were referred for endoscopy for generalized GI complaints in the same hospital as Cohort 1, but not the subspecialty clinic. Exclusion criteria and timing of IgA titers and endoscopy were identical to those of Cohort 1. The PPV of tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN in patients with biopsy-proven CD was 100%.

Cohort 3 (which included patients in 8 countries) was a retrospective analysis of the performance of multiple assays to enhance the validity of this approach in a wide range of settings. Adult patients (N = 145) with tTG-IgA serology positive for celiac who then underwent endoscopy with 4 to 6 duodenal biopsy samples were included in this analysis. Eleven distinct laboratories performed the tTG-IgA assay. The PPV of tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN in patients with biopsy-proven CD was 95.2% (95% CI, 84.6%-98.6%).

In total, this study included 1417 adult patients; 431 (30%) had tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN. Of those patients, 424 (98%) had histopathologic findings on duodenal biopsy consistent with CD.

Of note, there was no standardization as to the assays used for the tTG-IgA titers: Cohort 1 used 2 different manufacturers’ assays, Cohort 2 used 1 assay, and Cohort 3 used 5 assays. Regardless, the “≥ 10 times the ULN” calculation was based on each manufacturer’s published assay ranges. The lack of assay standardization did create variance in false-positive rates, however: Across all 3 cohorts, the false-positive rate for trusting the “≥ 10 times the ULN” threshold as the sole marker for CD in adults increased from 1% (Cohorts 1 and 2) to 5% (all 3 cohorts).

Continue to: WHAT'S NEW

WHAT’S NEW

Less invasive, less costly diagnosis of celiac disease in adults

In adults with symptoms suggestive of CD, the diagnosis can be made with a high level of certainty if a serum tTG-IgA titer is ≥ 10 times the ULN. Through informed, shared decision making in the presence of such a finding, patients may accept a serologic diagnosis and forgo an invasive EGD with biopsy and its inherent costs and risks. Indeed, if the majority of patients with CD are undiagnosed or underdiagnosed, and there exists a minimally invasive blood test that is highly cost effective in the absence of “red flags,” the overall benefit of this path could be substantial.

CAVEATS

“No biopsy” does not mean no risk/benefit discussion

While the PPVs are quite high, the negative predictive value varied greatly: 13%, 98%, and 10% for Cohorts 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Therefore, although serum tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN are useful for diagnosis, a negative result (serum tTG-IgA titers < 10 times the ULN) should not be used to rule out CD, and other testing should be pursued.

Additionally (although rare), patients with CD who have IgA deficiency may obtain false-negative results using the tTG-IgA ≥ 10 times the ULN diagnostic criterion.7,8

Also, both Cohorts 1 and 2 took place in general or subspecialty GI clinics (Cohort 3’s site types were not specified). However, the objective interpretation of tTG-IgA serology means it could be considered as an additional diagnostic tool for primary care physicians, as well.

Finally, if a primary care physician and their patient decide to go the “no-biopsy” route, it should be with a full discussion of the possible risks and benefits of not pursuing EGD. If there are any potential “red flag” symptoms suggesting the possibility of a more concerning differential diagnosis, EGD evaluation should still be pursued. Such symptoms might include (but not be limited to) chronic dyspepsia, dysphagia, weight loss, and unexplained anemia.7

Continue to: CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Diagnostic guidelines still favor EGD with biopsy for adults

The 2013 American College of Gastroenterology guidelines support the use of EGD and duodenal biopsy to diagnose CD in both low- and high-risk patients, regardless of serologic findings.7 In a 2019 Clinical Practice Update, the American Gastrointestinal Association (AGA) stated that when tTG-IgA titers are ≥ 10 times the ULN and EMAs are positive, the PPV is “virtually 100%” for CD. Yet they still state that in this scenario “EGD and duodenal biopsies may then be performed for purposes of differential diagnosis.”8 Furthermore, the AGA does not discuss informed and shared decision making with patients for the option of a “no-biopsy” diagnosis.8

Additionally, there may be challenges in finding commercial laboratories that report reference ranges with a clear ULN. Although costs for the serum tTG-IgA assay vary, they are less expensive than endoscopy with biopsy and histopathologic examination, and therefore may present less of a financial barrier.

1. Penny HA, Raju SA, Lau MS, et al. Accuracy of a no-biopsy approach for the diagnosis of coeliac disease across different adult cohorts. Gut. 2021;70:876-883. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320913

2. Al-Toma A, Volta U, Auricchio R, et al. European Society for the Study of Coeliac Disease (ESsCD) guideline for coeliac disease and other gluten-related disorders. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7:583-613. doi: 10.1177/2050640619844125

3. Caio G, Volta U, Sapone A, et al. Celiac disease: a comprehensive current review. BMC Med. 2019;17:142. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1380-z

4. Lebwohl B, Rubio-Tapia A. Epidemiology, presentation, and diagnosis of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:63-75. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.098

5. Lebwohl B, Sanders DS, Green PHR. Coeliac disease. Lancet. 2018;391:70-81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31796-8

6. Rubin JE, Crowe SE. Celiac disease. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:ITC1-ITC16. doi: 10.7326/AITC202001070

7. Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Kelly CP, et al; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:656-676; quiz 677. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.79

8. Husby S, Murray JA, Katzka DA. AGA clinical practice update on diagnosis and monitoring of celiac disease—changing utility of serology and histologic measures: expert review. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:885-889. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.010

9. Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó I, et al. European Society Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition guidelines for diagnosing coeliac disease 2020. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020;70:141-156. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002497

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 43-year-old woman presents to the clinic with diffuse, intermittent abdominal discomfort, bloating, and diarrhea that has slowly but steadily worsened over the past few years to now-daily symptoms. She states her overall health is otherwise good. Her review of systems is pertinent only for 8 lbs of unintentional weight loss over the past year and increased fatigue. She takes no supplements or routine over-the-counter or prescription medications, except for low-dose combination oral contraceptives, and is unaware of any family history of gastrointestinal (GI) diseases. She does not drink or smoke. She is up to date with immunizations and with cervical and breast cancer screening. Her body mass index is 23, her vital signs are within normal limits, and her physical exam is normal except for mild, diffuse abdominal tenderness without any masses, organomegaly, or peritoneal signs.

Her diagnostic work-up includes a complete metabolic panel, magnesium level, complete blood count, thyroid-stimulating hormone measurement, cytomegalovirus IgG and IgM serology, and stool studies for fecal leukocytes, ova and parasites, and fecal fat, in addition to a kidney, ureter, and bladder noncontrast computed tomography scan. All diagnostic testing is negative except for slightly elevated fecal fat, thereby decreasing the likelihood of infection, thyroid disorder, electrolyte abnormalities, or malignancy as a source of her symptoms.

She says that based on her online searches, her symptoms seem consistent with CD—with which you concur. However, she is fearful of an endoscopic procedure and asks if there is any other way to diagnose CD.

CD is an immune-mediated disorder in genetically susceptible people that is triggered by dietary gluten, causing damage to the small intestine.1-6 The estimated worldwide prevalence of CD is approximately 1%, with greater prevalence in females.1-6 A strong genetic predisposition also has been noted: prevalence among first-degree relatives is 10% to 44%.2,3,6 Although CD can be diagnosed at any age, in the United States the mean age at diagnosis is in the fifth decade of life.6

The incidence of CD is on the rise due to true increases in disease incidence and prevalence, increased detection through better diagnostic tools, and increased screening of at-risk populations (eg, first-degree relatives, those with specific human leukocyte antigen variant genotypes, and those with certain chromosomal disorders, such as Down syndrome and Turner syndrome).2-6 However, despite the increasing prevalence of CD, most patients remain undiagnosed.1

The diagnosis of CD in adults is typically made with elevated serum tTG-IgA and

STUDY SUMMARY

tTG-IgA titers were highly predictive of CD in 3 distinct cohorts

This 2021 hybrid prospective/retrospective study with 3 distinct cohorts aimed to assess the utility of serum tTG-IgA titers compared to traditional EGD with duodenal biopsy for the diagnosis of CD in adult participants (defined as ≥ 16 years of age). A serum tTG-IgA titer ≥ 10 times the ULN was set as the minimal cutoff value, and standardized duodenal biopsy sampling and evaluation for histologic mucosal changes consistent with

Continue to: Cohort 1 was a...

Cohort 1 was a prospective analysis of adults (N = 740) considered to have a high suspicion for CD, recruited from a single CD subspecialty clinic in the United Kingdom. Patients with a previous diagnosis of CD, those adhering to a gluten-free diet, and those with IgA deficiency were excluded. Study patients had tTG-IgA titers drawn and, within 6 weeks, underwent endoscopy with ≥ 1 biopsy from the duodenal bulb and/or the second part of the duodenum. The PPV of tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN in patients with biopsy-proven CD was 98.7% (95% CI, 97%-99.4%).

Cohort 2 was a retrospective analysis of adult patients (N = 532) considered to have low suspicion for CD. These patients were referred for endoscopy for generalized GI complaints in the same hospital as Cohort 1, but not the subspecialty clinic. Exclusion criteria and timing of IgA titers and endoscopy were identical to those of Cohort 1. The PPV of tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN in patients with biopsy-proven CD was 100%.

Cohort 3 (which included patients in 8 countries) was a retrospective analysis of the performance of multiple assays to enhance the validity of this approach in a wide range of settings. Adult patients (N = 145) with tTG-IgA serology positive for celiac who then underwent endoscopy with 4 to 6 duodenal biopsy samples were included in this analysis. Eleven distinct laboratories performed the tTG-IgA assay. The PPV of tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN in patients with biopsy-proven CD was 95.2% (95% CI, 84.6%-98.6%).

In total, this study included 1417 adult patients; 431 (30%) had tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN. Of those patients, 424 (98%) had histopathologic findings on duodenal biopsy consistent with CD.

Of note, there was no standardization as to the assays used for the tTG-IgA titers: Cohort 1 used 2 different manufacturers’ assays, Cohort 2 used 1 assay, and Cohort 3 used 5 assays. Regardless, the “≥ 10 times the ULN” calculation was based on each manufacturer’s published assay ranges. The lack of assay standardization did create variance in false-positive rates, however: Across all 3 cohorts, the false-positive rate for trusting the “≥ 10 times the ULN” threshold as the sole marker for CD in adults increased from 1% (Cohorts 1 and 2) to 5% (all 3 cohorts).

Continue to: WHAT'S NEW

WHAT’S NEW

Less invasive, less costly diagnosis of celiac disease in adults

In adults with symptoms suggestive of CD, the diagnosis can be made with a high level of certainty if a serum tTG-IgA titer is ≥ 10 times the ULN. Through informed, shared decision making in the presence of such a finding, patients may accept a serologic diagnosis and forgo an invasive EGD with biopsy and its inherent costs and risks. Indeed, if the majority of patients with CD are undiagnosed or underdiagnosed, and there exists a minimally invasive blood test that is highly cost effective in the absence of “red flags,” the overall benefit of this path could be substantial.

CAVEATS

“No biopsy” does not mean no risk/benefit discussion

While the PPVs are quite high, the negative predictive value varied greatly: 13%, 98%, and 10% for Cohorts 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Therefore, although serum tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN are useful for diagnosis, a negative result (serum tTG-IgA titers < 10 times the ULN) should not be used to rule out CD, and other testing should be pursued.

Additionally (although rare), patients with CD who have IgA deficiency may obtain false-negative results using the tTG-IgA ≥ 10 times the ULN diagnostic criterion.7,8

Also, both Cohorts 1 and 2 took place in general or subspecialty GI clinics (Cohort 3’s site types were not specified). However, the objective interpretation of tTG-IgA serology means it could be considered as an additional diagnostic tool for primary care physicians, as well.

Finally, if a primary care physician and their patient decide to go the “no-biopsy” route, it should be with a full discussion of the possible risks and benefits of not pursuing EGD. If there are any potential “red flag” symptoms suggesting the possibility of a more concerning differential diagnosis, EGD evaluation should still be pursued. Such symptoms might include (but not be limited to) chronic dyspepsia, dysphagia, weight loss, and unexplained anemia.7

Continue to: CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Diagnostic guidelines still favor EGD with biopsy for adults

The 2013 American College of Gastroenterology guidelines support the use of EGD and duodenal biopsy to diagnose CD in both low- and high-risk patients, regardless of serologic findings.7 In a 2019 Clinical Practice Update, the American Gastrointestinal Association (AGA) stated that when tTG-IgA titers are ≥ 10 times the ULN and EMAs are positive, the PPV is “virtually 100%” for CD. Yet they still state that in this scenario “EGD and duodenal biopsies may then be performed for purposes of differential diagnosis.”8 Furthermore, the AGA does not discuss informed and shared decision making with patients for the option of a “no-biopsy” diagnosis.8

Additionally, there may be challenges in finding commercial laboratories that report reference ranges with a clear ULN. Although costs for the serum tTG-IgA assay vary, they are less expensive than endoscopy with biopsy and histopathologic examination, and therefore may present less of a financial barrier.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 43-year-old woman presents to the clinic with diffuse, intermittent abdominal discomfort, bloating, and diarrhea that has slowly but steadily worsened over the past few years to now-daily symptoms. She states her overall health is otherwise good. Her review of systems is pertinent only for 8 lbs of unintentional weight loss over the past year and increased fatigue. She takes no supplements or routine over-the-counter or prescription medications, except for low-dose combination oral contraceptives, and is unaware of any family history of gastrointestinal (GI) diseases. She does not drink or smoke. She is up to date with immunizations and with cervical and breast cancer screening. Her body mass index is 23, her vital signs are within normal limits, and her physical exam is normal except for mild, diffuse abdominal tenderness without any masses, organomegaly, or peritoneal signs.

Her diagnostic work-up includes a complete metabolic panel, magnesium level, complete blood count, thyroid-stimulating hormone measurement, cytomegalovirus IgG and IgM serology, and stool studies for fecal leukocytes, ova and parasites, and fecal fat, in addition to a kidney, ureter, and bladder noncontrast computed tomography scan. All diagnostic testing is negative except for slightly elevated fecal fat, thereby decreasing the likelihood of infection, thyroid disorder, electrolyte abnormalities, or malignancy as a source of her symptoms.

She says that based on her online searches, her symptoms seem consistent with CD—with which you concur. However, she is fearful of an endoscopic procedure and asks if there is any other way to diagnose CD.

CD is an immune-mediated disorder in genetically susceptible people that is triggered by dietary gluten, causing damage to the small intestine.1-6 The estimated worldwide prevalence of CD is approximately 1%, with greater prevalence in females.1-6 A strong genetic predisposition also has been noted: prevalence among first-degree relatives is 10% to 44%.2,3,6 Although CD can be diagnosed at any age, in the United States the mean age at diagnosis is in the fifth decade of life.6

The incidence of CD is on the rise due to true increases in disease incidence and prevalence, increased detection through better diagnostic tools, and increased screening of at-risk populations (eg, first-degree relatives, those with specific human leukocyte antigen variant genotypes, and those with certain chromosomal disorders, such as Down syndrome and Turner syndrome).2-6 However, despite the increasing prevalence of CD, most patients remain undiagnosed.1

The diagnosis of CD in adults is typically made with elevated serum tTG-IgA and

STUDY SUMMARY

tTG-IgA titers were highly predictive of CD in 3 distinct cohorts

This 2021 hybrid prospective/retrospective study with 3 distinct cohorts aimed to assess the utility of serum tTG-IgA titers compared to traditional EGD with duodenal biopsy for the diagnosis of CD in adult participants (defined as ≥ 16 years of age). A serum tTG-IgA titer ≥ 10 times the ULN was set as the minimal cutoff value, and standardized duodenal biopsy sampling and evaluation for histologic mucosal changes consistent with

Continue to: Cohort 1 was a...

Cohort 1 was a prospective analysis of adults (N = 740) considered to have a high suspicion for CD, recruited from a single CD subspecialty clinic in the United Kingdom. Patients with a previous diagnosis of CD, those adhering to a gluten-free diet, and those with IgA deficiency were excluded. Study patients had tTG-IgA titers drawn and, within 6 weeks, underwent endoscopy with ≥ 1 biopsy from the duodenal bulb and/or the second part of the duodenum. The PPV of tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN in patients with biopsy-proven CD was 98.7% (95% CI, 97%-99.4%).

Cohort 2 was a retrospective analysis of adult patients (N = 532) considered to have low suspicion for CD. These patients were referred for endoscopy for generalized GI complaints in the same hospital as Cohort 1, but not the subspecialty clinic. Exclusion criteria and timing of IgA titers and endoscopy were identical to those of Cohort 1. The PPV of tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN in patients with biopsy-proven CD was 100%.

Cohort 3 (which included patients in 8 countries) was a retrospective analysis of the performance of multiple assays to enhance the validity of this approach in a wide range of settings. Adult patients (N = 145) with tTG-IgA serology positive for celiac who then underwent endoscopy with 4 to 6 duodenal biopsy samples were included in this analysis. Eleven distinct laboratories performed the tTG-IgA assay. The PPV of tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN in patients with biopsy-proven CD was 95.2% (95% CI, 84.6%-98.6%).

In total, this study included 1417 adult patients; 431 (30%) had tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN. Of those patients, 424 (98%) had histopathologic findings on duodenal biopsy consistent with CD.

Of note, there was no standardization as to the assays used for the tTG-IgA titers: Cohort 1 used 2 different manufacturers’ assays, Cohort 2 used 1 assay, and Cohort 3 used 5 assays. Regardless, the “≥ 10 times the ULN” calculation was based on each manufacturer’s published assay ranges. The lack of assay standardization did create variance in false-positive rates, however: Across all 3 cohorts, the false-positive rate for trusting the “≥ 10 times the ULN” threshold as the sole marker for CD in adults increased from 1% (Cohorts 1 and 2) to 5% (all 3 cohorts).

Continue to: WHAT'S NEW

WHAT’S NEW

Less invasive, less costly diagnosis of celiac disease in adults

In adults with symptoms suggestive of CD, the diagnosis can be made with a high level of certainty if a serum tTG-IgA titer is ≥ 10 times the ULN. Through informed, shared decision making in the presence of such a finding, patients may accept a serologic diagnosis and forgo an invasive EGD with biopsy and its inherent costs and risks. Indeed, if the majority of patients with CD are undiagnosed or underdiagnosed, and there exists a minimally invasive blood test that is highly cost effective in the absence of “red flags,” the overall benefit of this path could be substantial.

CAVEATS

“No biopsy” does not mean no risk/benefit discussion

While the PPVs are quite high, the negative predictive value varied greatly: 13%, 98%, and 10% for Cohorts 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Therefore, although serum tTG-IgA titers ≥ 10 times the ULN are useful for diagnosis, a negative result (serum tTG-IgA titers < 10 times the ULN) should not be used to rule out CD, and other testing should be pursued.

Additionally (although rare), patients with CD who have IgA deficiency may obtain false-negative results using the tTG-IgA ≥ 10 times the ULN diagnostic criterion.7,8

Also, both Cohorts 1 and 2 took place in general or subspecialty GI clinics (Cohort 3’s site types were not specified). However, the objective interpretation of tTG-IgA serology means it could be considered as an additional diagnostic tool for primary care physicians, as well.

Finally, if a primary care physician and their patient decide to go the “no-biopsy” route, it should be with a full discussion of the possible risks and benefits of not pursuing EGD. If there are any potential “red flag” symptoms suggesting the possibility of a more concerning differential diagnosis, EGD evaluation should still be pursued. Such symptoms might include (but not be limited to) chronic dyspepsia, dysphagia, weight loss, and unexplained anemia.7

Continue to: CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Diagnostic guidelines still favor EGD with biopsy for adults

The 2013 American College of Gastroenterology guidelines support the use of EGD and duodenal biopsy to diagnose CD in both low- and high-risk patients, regardless of serologic findings.7 In a 2019 Clinical Practice Update, the American Gastrointestinal Association (AGA) stated that when tTG-IgA titers are ≥ 10 times the ULN and EMAs are positive, the PPV is “virtually 100%” for CD. Yet they still state that in this scenario “EGD and duodenal biopsies may then be performed for purposes of differential diagnosis.”8 Furthermore, the AGA does not discuss informed and shared decision making with patients for the option of a “no-biopsy” diagnosis.8

Additionally, there may be challenges in finding commercial laboratories that report reference ranges with a clear ULN. Although costs for the serum tTG-IgA assay vary, they are less expensive than endoscopy with biopsy and histopathologic examination, and therefore may present less of a financial barrier.

1. Penny HA, Raju SA, Lau MS, et al. Accuracy of a no-biopsy approach for the diagnosis of coeliac disease across different adult cohorts. Gut. 2021;70:876-883. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320913

2. Al-Toma A, Volta U, Auricchio R, et al. European Society for the Study of Coeliac Disease (ESsCD) guideline for coeliac disease and other gluten-related disorders. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7:583-613. doi: 10.1177/2050640619844125

3. Caio G, Volta U, Sapone A, et al. Celiac disease: a comprehensive current review. BMC Med. 2019;17:142. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1380-z

4. Lebwohl B, Rubio-Tapia A. Epidemiology, presentation, and diagnosis of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:63-75. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.098

5. Lebwohl B, Sanders DS, Green PHR. Coeliac disease. Lancet. 2018;391:70-81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31796-8

6. Rubin JE, Crowe SE. Celiac disease. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:ITC1-ITC16. doi: 10.7326/AITC202001070

7. Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Kelly CP, et al; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:656-676; quiz 677. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.79

8. Husby S, Murray JA, Katzka DA. AGA clinical practice update on diagnosis and monitoring of celiac disease—changing utility of serology and histologic measures: expert review. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:885-889. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.010

9. Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó I, et al. European Society Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition guidelines for diagnosing coeliac disease 2020. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020;70:141-156. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002497

1. Penny HA, Raju SA, Lau MS, et al. Accuracy of a no-biopsy approach for the diagnosis of coeliac disease across different adult cohorts. Gut. 2021;70:876-883. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320913

2. Al-Toma A, Volta U, Auricchio R, et al. European Society for the Study of Coeliac Disease (ESsCD) guideline for coeliac disease and other gluten-related disorders. United European Gastroenterol J. 2019;7:583-613. doi: 10.1177/2050640619844125

3. Caio G, Volta U, Sapone A, et al. Celiac disease: a comprehensive current review. BMC Med. 2019;17:142. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1380-z

4. Lebwohl B, Rubio-Tapia A. Epidemiology, presentation, and diagnosis of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:63-75. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.098

5. Lebwohl B, Sanders DS, Green PHR. Coeliac disease. Lancet. 2018;391:70-81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31796-8

6. Rubin JE, Crowe SE. Celiac disease. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:ITC1-ITC16. doi: 10.7326/AITC202001070

7. Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Kelly CP, et al; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:656-676; quiz 677. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.79

8. Husby S, Murray JA, Katzka DA. AGA clinical practice update on diagnosis and monitoring of celiac disease—changing utility of serology and histologic measures: expert review. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:885-889. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.010

9. Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó I, et al. European Society Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition guidelines for diagnosing coeliac disease 2020. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020;70:141-156. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002497

PRACTICE CHANGER

Consider a “no-biopsy” approach by evaluating serum immunoglobulin (Ig) A anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTG-IgA) antibody titers in adult patients who present with symptoms concerning for celiac disease (CD). An increase of ≥ 10 times the upper limit of normal (ULN) for tTG-IgA has a positive predictive value (PPV) of ≥ 95% for diagnosing CD when compared with esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with duodenal biopsy—the current gold standard.

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: Consistent findings from 3 good-quality diagnostic cohorts presented in a single study.1

Penny HA, Raju SA, Lau MS, et al. Accuracy of a no-biopsy approach for the diagnosis of coeliac disease across different adult cohorts. Gut. 2021;70:876-883. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320913

Confidently rule out CAP in the outpatient setting

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

An otherwise healthy 56-year-old woman presents to the emergency department (ED) with a productive cough of 4 days’ duration. A review of her history is negative for recurrent upper respiratory infections, smoking, or environmental exposures. Her physical exam is unremarkable and, more specifically, her pulmonary exam and vital signs (temperature, respiratory rate, and heart rate) are within normal limits. The patient states that last year her friend had similar symptoms and was given a diagnosis of pneumonia. Is it necessary to order a chest x-ray in this patient to rule out community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)?

CAP is a common pulmonary condition seen in the outpatient setting in the United States, representing more than 4.5 million outpatient visits in the years 2009 to 2010.2 Historically, a diagnosis of CAP has been based on clinical findings in conjunction with infiltrates seen on chest x-ray.

In 2017, more than 5 million visits to the ED were due to a cough.3 The use of radiographic imaging in EDs has been increasing. There were 49 million x-rays and 2.7 million noncardiac chest computed tomography (CT) scans performed in 2016, many of which were for patients with cough.3,4 Although imaging is an extremely useful tool and indicated in many instances, the ability to rule out CAP in an adult who presents with a cough by using a set of simple, clinically based heuristics without requiring imaging would help to increase efficiency, limit cost, and decrease exposure of patients to unnecessary and potentially harmful diagnostic studies.

Clinical decision rules (CDRs) are simple heuristics that can stratify patients as either high risk or low risk for specific diseases. Two older large, prospective cross-sectional studies developed CDRs to determine the probability of CAP based on symptoms (eg, night sweats, myalgias, and sputum production) and clinical findings (eg, temperature > 37.8 °C [100 °F], tachypnea, tachycardia, rales, and decreased breath sounds).5,6 This meta-analysis includes these studies and more recent studies7-9 used to develop a CDR that focuses solely on a few specific signs and symptoms that can reliably rule out CAP without imaging, and so prove highly useful for busy primary care clinicians.

STUDY SUMMARY

This simple approach rules out CAP in outpatients 99.6% of the time

This systematic review and meta-analysis included studies that used 2 or more signs, symptoms, or point-of-care tests to determine the patient’s risk for CAP.1 Twelve studies (N = 10,254) met inclusion criteria by applying a CDR to adults or adolescents presenting with respiratory signs or symptoms potentially suggestive of CAP to either an outpatient setting or an ED. Prospective cohort, cross-sectional, and case-control studies were included when a chest x-ray or CT was utilized as the primary reference standard. Exclusion criteria included studies of military or nursing home populations and studies in which the majority of patients had hospital- or ventilator-associated pneumonia or were immunocompromised.

A simple, highly useful CDR emerged from 3 of the studies (N = 1865).7-9 Two of these studies were described as case-control studies with prospective enrollment of patients older than 17 years in both outpatient and ED settings.7,8 One study was conducted in the United States (mean age, 65 years) and the other in Iran (mean age, 60 years). The third was a Chilean prospective cohort study of ED patients older than 15 years (mean age, 53 years).9 In each of these studies, the outpatient or ED physicians collected all clinical data and documented their physical exam prior to receiving the chest radiograph results. The radiologists were masked to the clinical findings at the time of their interpretation.

Results. From the meta-analysis, a simple CDR emerged for patients with normal vital signs (temperature, respiratory rate, and heart rate) and a normal pulmonary exam that virtually ruled out CAP (sensitivity = 96%; 95% CI, 92%–98%; and negative likelihood ratio = 0.10; 95% CI, 0.07–0.13). In patients presenting to an outpatient clinic with acute cough with a 4% baseline prevalence rate of pneumonia, this CDR ruled out CAP 99.6% of the time.

Continue to: WHAT'S NEW

WHAT’S NEW

A clinical decision rule validated for accuracy

This is the first validated CDR that accurately rules out CAP in the outpatient or ED setting using parameters easily obtainable during a clinical exam.

CAVEATS

Proceed with caution in the young and the very old

Two of the 3 studies in this CDR had an overall moderate risk of bias, whereas the third study was determined to be at low risk of bias, based on appraisal with the Quality Assessment Tool for Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) framework.10

The mean age range in these 3 studies was 53 to 66 years (without further data such as standard deviation), suggesting that application of the CDR to adults who fall at extremes of age should be done with a modicum of caution.

Additionally, although the symptom complex of COVID-19 pneumonia would suggest that this CDR would likely remain accurate today, it has not been validated in patients with COVID-19 infection.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Potential reluctance to forgo imaging

Beyond the caveats regarding COVID-19, the use of a simple CDR to reliably exclude pneumonia should have no barrier to implementation in an outpatient primary care setting or ED, although there could be reluctance on the part of both providers and patients to fully embrace this simple tool without a confirmatory chest x-ray.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Marchello CS, Ebell MH, Dale AP, et al. Signs and symptoms that rule out community-acquired pneumonia in outpatient adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32:234-247.

2. St Sauver JL, Warner DO, Yawn BP, et al. Why patients visit their doctors: assessing the most prevalent conditions in a defined American population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:56-67.

3. CDC. National Center for Health Statistics. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2017. Emergency Department Summary Tables. Accessed March 24, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2017_ed_web_tables-508.pdf

4. Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al; CDC EPIC Study Team. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among US adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:415-427.

5. Heckerling PS, Tape TG, Wigton RS, et al. Clinical prediction rule for pulmonary infiltrates. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:664-670.

6. Diehr P, Wood RW, Bushyhead J, et al. Prediction of pneumonia in outpatients with acute cough—a statistical approach. J Chronic Dis. 1984;37:215-225.

7. O’Brien WT Sr, Rohweder DA, Lattin GE Jr, et al. Clinical indicators of radiographic findings in patients with suspected community-acquired pneumonia: who needs a chest x-ray? J Am Coll Radiol. 2006;3:703-706.

8. Ebrahimzadeh A, Mohammadifard M, Naseh G, et al. Clinical and laboratory findings in patients with acute respiratory symptoms that suggest the necessity of chest x-ray for community-acquired pneumonia. Iran J Radiol. 2015;12:e13547.

9. Saldías PF, Cabrera TD, de Solminihac LI, et al. Valor predictivo de la historia clínica y examen físico en el diagnóstico de neumonía del adulto adquirida en la comunidad [Predictive value of history and physical examination for the diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia in adults]. Abstract in English. Rev Med Chil. 2007;135:143-152.

10. Whiting PF, Rutjes AWS, Westwood ME, et al; QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:529-536.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

An otherwise healthy 56-year-old woman presents to the emergency department (ED) with a productive cough of 4 days’ duration. A review of her history is negative for recurrent upper respiratory infections, smoking, or environmental exposures. Her physical exam is unremarkable and, more specifically, her pulmonary exam and vital signs (temperature, respiratory rate, and heart rate) are within normal limits. The patient states that last year her friend had similar symptoms and was given a diagnosis of pneumonia. Is it necessary to order a chest x-ray in this patient to rule out community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)?

CAP is a common pulmonary condition seen in the outpatient setting in the United States, representing more than 4.5 million outpatient visits in the years 2009 to 2010.2 Historically, a diagnosis of CAP has been based on clinical findings in conjunction with infiltrates seen on chest x-ray.

In 2017, more than 5 million visits to the ED were due to a cough.3 The use of radiographic imaging in EDs has been increasing. There were 49 million x-rays and 2.7 million noncardiac chest computed tomography (CT) scans performed in 2016, many of which were for patients with cough.3,4 Although imaging is an extremely useful tool and indicated in many instances, the ability to rule out CAP in an adult who presents with a cough by using a set of simple, clinically based heuristics without requiring imaging would help to increase efficiency, limit cost, and decrease exposure of patients to unnecessary and potentially harmful diagnostic studies.

Clinical decision rules (CDRs) are simple heuristics that can stratify patients as either high risk or low risk for specific diseases. Two older large, prospective cross-sectional studies developed CDRs to determine the probability of CAP based on symptoms (eg, night sweats, myalgias, and sputum production) and clinical findings (eg, temperature > 37.8 °C [100 °F], tachypnea, tachycardia, rales, and decreased breath sounds).5,6 This meta-analysis includes these studies and more recent studies7-9 used to develop a CDR that focuses solely on a few specific signs and symptoms that can reliably rule out CAP without imaging, and so prove highly useful for busy primary care clinicians.

STUDY SUMMARY

This simple approach rules out CAP in outpatients 99.6% of the time

This systematic review and meta-analysis included studies that used 2 or more signs, symptoms, or point-of-care tests to determine the patient’s risk for CAP.1 Twelve studies (N = 10,254) met inclusion criteria by applying a CDR to adults or adolescents presenting with respiratory signs or symptoms potentially suggestive of CAP to either an outpatient setting or an ED. Prospective cohort, cross-sectional, and case-control studies were included when a chest x-ray or CT was utilized as the primary reference standard. Exclusion criteria included studies of military or nursing home populations and studies in which the majority of patients had hospital- or ventilator-associated pneumonia or were immunocompromised.

A simple, highly useful CDR emerged from 3 of the studies (N = 1865).7-9 Two of these studies were described as case-control studies with prospective enrollment of patients older than 17 years in both outpatient and ED settings.7,8 One study was conducted in the United States (mean age, 65 years) and the other in Iran (mean age, 60 years). The third was a Chilean prospective cohort study of ED patients older than 15 years (mean age, 53 years).9 In each of these studies, the outpatient or ED physicians collected all clinical data and documented their physical exam prior to receiving the chest radiograph results. The radiologists were masked to the clinical findings at the time of their interpretation.

Results. From the meta-analysis, a simple CDR emerged for patients with normal vital signs (temperature, respiratory rate, and heart rate) and a normal pulmonary exam that virtually ruled out CAP (sensitivity = 96%; 95% CI, 92%–98%; and negative likelihood ratio = 0.10; 95% CI, 0.07–0.13). In patients presenting to an outpatient clinic with acute cough with a 4% baseline prevalence rate of pneumonia, this CDR ruled out CAP 99.6% of the time.

Continue to: WHAT'S NEW

WHAT’S NEW

A clinical decision rule validated for accuracy

This is the first validated CDR that accurately rules out CAP in the outpatient or ED setting using parameters easily obtainable during a clinical exam.

CAVEATS

Proceed with caution in the young and the very old

Two of the 3 studies in this CDR had an overall moderate risk of bias, whereas the third study was determined to be at low risk of bias, based on appraisal with the Quality Assessment Tool for Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) framework.10

The mean age range in these 3 studies was 53 to 66 years (without further data such as standard deviation), suggesting that application of the CDR to adults who fall at extremes of age should be done with a modicum of caution.

Additionally, although the symptom complex of COVID-19 pneumonia would suggest that this CDR would likely remain accurate today, it has not been validated in patients with COVID-19 infection.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Potential reluctance to forgo imaging

Beyond the caveats regarding COVID-19, the use of a simple CDR to reliably exclude pneumonia should have no barrier to implementation in an outpatient primary care setting or ED, although there could be reluctance on the part of both providers and patients to fully embrace this simple tool without a confirmatory chest x-ray.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

An otherwise healthy 56-year-old woman presents to the emergency department (ED) with a productive cough of 4 days’ duration. A review of her history is negative for recurrent upper respiratory infections, smoking, or environmental exposures. Her physical exam is unremarkable and, more specifically, her pulmonary exam and vital signs (temperature, respiratory rate, and heart rate) are within normal limits. The patient states that last year her friend had similar symptoms and was given a diagnosis of pneumonia. Is it necessary to order a chest x-ray in this patient to rule out community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)?

CAP is a common pulmonary condition seen in the outpatient setting in the United States, representing more than 4.5 million outpatient visits in the years 2009 to 2010.2 Historically, a diagnosis of CAP has been based on clinical findings in conjunction with infiltrates seen on chest x-ray.

In 2017, more than 5 million visits to the ED were due to a cough.3 The use of radiographic imaging in EDs has been increasing. There were 49 million x-rays and 2.7 million noncardiac chest computed tomography (CT) scans performed in 2016, many of which were for patients with cough.3,4 Although imaging is an extremely useful tool and indicated in many instances, the ability to rule out CAP in an adult who presents with a cough by using a set of simple, clinically based heuristics without requiring imaging would help to increase efficiency, limit cost, and decrease exposure of patients to unnecessary and potentially harmful diagnostic studies.

Clinical decision rules (CDRs) are simple heuristics that can stratify patients as either high risk or low risk for specific diseases. Two older large, prospective cross-sectional studies developed CDRs to determine the probability of CAP based on symptoms (eg, night sweats, myalgias, and sputum production) and clinical findings (eg, temperature > 37.8 °C [100 °F], tachypnea, tachycardia, rales, and decreased breath sounds).5,6 This meta-analysis includes these studies and more recent studies7-9 used to develop a CDR that focuses solely on a few specific signs and symptoms that can reliably rule out CAP without imaging, and so prove highly useful for busy primary care clinicians.

STUDY SUMMARY

This simple approach rules out CAP in outpatients 99.6% of the time

This systematic review and meta-analysis included studies that used 2 or more signs, symptoms, or point-of-care tests to determine the patient’s risk for CAP.1 Twelve studies (N = 10,254) met inclusion criteria by applying a CDR to adults or adolescents presenting with respiratory signs or symptoms potentially suggestive of CAP to either an outpatient setting or an ED. Prospective cohort, cross-sectional, and case-control studies were included when a chest x-ray or CT was utilized as the primary reference standard. Exclusion criteria included studies of military or nursing home populations and studies in which the majority of patients had hospital- or ventilator-associated pneumonia or were immunocompromised.

A simple, highly useful CDR emerged from 3 of the studies (N = 1865).7-9 Two of these studies were described as case-control studies with prospective enrollment of patients older than 17 years in both outpatient and ED settings.7,8 One study was conducted in the United States (mean age, 65 years) and the other in Iran (mean age, 60 years). The third was a Chilean prospective cohort study of ED patients older than 15 years (mean age, 53 years).9 In each of these studies, the outpatient or ED physicians collected all clinical data and documented their physical exam prior to receiving the chest radiograph results. The radiologists were masked to the clinical findings at the time of their interpretation.

Results. From the meta-analysis, a simple CDR emerged for patients with normal vital signs (temperature, respiratory rate, and heart rate) and a normal pulmonary exam that virtually ruled out CAP (sensitivity = 96%; 95% CI, 92%–98%; and negative likelihood ratio = 0.10; 95% CI, 0.07–0.13). In patients presenting to an outpatient clinic with acute cough with a 4% baseline prevalence rate of pneumonia, this CDR ruled out CAP 99.6% of the time.

Continue to: WHAT'S NEW

WHAT’S NEW

A clinical decision rule validated for accuracy

This is the first validated CDR that accurately rules out CAP in the outpatient or ED setting using parameters easily obtainable during a clinical exam.

CAVEATS

Proceed with caution in the young and the very old

Two of the 3 studies in this CDR had an overall moderate risk of bias, whereas the third study was determined to be at low risk of bias, based on appraisal with the Quality Assessment Tool for Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) framework.10

The mean age range in these 3 studies was 53 to 66 years (without further data such as standard deviation), suggesting that application of the CDR to adults who fall at extremes of age should be done with a modicum of caution.

Additionally, although the symptom complex of COVID-19 pneumonia would suggest that this CDR would likely remain accurate today, it has not been validated in patients with COVID-19 infection.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Potential reluctance to forgo imaging

Beyond the caveats regarding COVID-19, the use of a simple CDR to reliably exclude pneumonia should have no barrier to implementation in an outpatient primary care setting or ED, although there could be reluctance on the part of both providers and patients to fully embrace this simple tool without a confirmatory chest x-ray.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Marchello CS, Ebell MH, Dale AP, et al. Signs and symptoms that rule out community-acquired pneumonia in outpatient adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32:234-247.

2. St Sauver JL, Warner DO, Yawn BP, et al. Why patients visit their doctors: assessing the most prevalent conditions in a defined American population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:56-67.

3. CDC. National Center for Health Statistics. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2017. Emergency Department Summary Tables. Accessed March 24, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2017_ed_web_tables-508.pdf

4. Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al; CDC EPIC Study Team. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among US adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:415-427.

5. Heckerling PS, Tape TG, Wigton RS, et al. Clinical prediction rule for pulmonary infiltrates. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:664-670.

6. Diehr P, Wood RW, Bushyhead J, et al. Prediction of pneumonia in outpatients with acute cough—a statistical approach. J Chronic Dis. 1984;37:215-225.

7. O’Brien WT Sr, Rohweder DA, Lattin GE Jr, et al. Clinical indicators of radiographic findings in patients with suspected community-acquired pneumonia: who needs a chest x-ray? J Am Coll Radiol. 2006;3:703-706.

8. Ebrahimzadeh A, Mohammadifard M, Naseh G, et al. Clinical and laboratory findings in patients with acute respiratory symptoms that suggest the necessity of chest x-ray for community-acquired pneumonia. Iran J Radiol. 2015;12:e13547.

9. Saldías PF, Cabrera TD, de Solminihac LI, et al. Valor predictivo de la historia clínica y examen físico en el diagnóstico de neumonía del adulto adquirida en la comunidad [Predictive value of history and physical examination for the diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia in adults]. Abstract in English. Rev Med Chil. 2007;135:143-152.

10. Whiting PF, Rutjes AWS, Westwood ME, et al; QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:529-536.

1. Marchello CS, Ebell MH, Dale AP, et al. Signs and symptoms that rule out community-acquired pneumonia in outpatient adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32:234-247.

2. St Sauver JL, Warner DO, Yawn BP, et al. Why patients visit their doctors: assessing the most prevalent conditions in a defined American population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:56-67.

3. CDC. National Center for Health Statistics. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2017. Emergency Department Summary Tables. Accessed March 24, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2017_ed_web_tables-508.pdf

4. Jain S, Self WH, Wunderink RG, et al; CDC EPIC Study Team. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among US adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:415-427.

5. Heckerling PS, Tape TG, Wigton RS, et al. Clinical prediction rule for pulmonary infiltrates. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:664-670.

6. Diehr P, Wood RW, Bushyhead J, et al. Prediction of pneumonia in outpatients with acute cough—a statistical approach. J Chronic Dis. 1984;37:215-225.

7. O’Brien WT Sr, Rohweder DA, Lattin GE Jr, et al. Clinical indicators of radiographic findings in patients with suspected community-acquired pneumonia: who needs a chest x-ray? J Am Coll Radiol. 2006;3:703-706.

8. Ebrahimzadeh A, Mohammadifard M, Naseh G, et al. Clinical and laboratory findings in patients with acute respiratory symptoms that suggest the necessity of chest x-ray for community-acquired pneumonia. Iran J Radiol. 2015;12:e13547.

9. Saldías PF, Cabrera TD, de Solminihac LI, et al. Valor predictivo de la historia clínica y examen físico en el diagnóstico de neumonía del adulto adquirida en la comunidad [Predictive value of history and physical examination for the diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia in adults]. Abstract in English. Rev Med Chil. 2007;135:143-152.

10. Whiting PF, Rutjes AWS, Westwood ME, et al; QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:529-536.

PRACTICE CHANGER

You can safely rule out community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)—without requiring a chest x-ray—in an otherwise healthy adult outpatient who has an acute cough, a normal pulmonary exam, and normal vital signs using this simple clinical decision rule (CDR).1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: Based on a systematic review of prospective case-control studies and randomized controlled trials in the outpatient setting.1

Marchello CS, Ebell MH, Dale AP, et al. Signs and symptoms that rule out community-acquired pneumonia in outpatient adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32:234-247.

Surgery vs conservative management for AC joint repair: How do the 2 compare?

When not considering the grade of acromioclavicular (AC) joint dislocation, both conservative and surgical management lead to positive outcomes, although surgically managed patients require more time out of work (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, Cochrane review of low-quality randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

For Rockwood grade III dislocations, surgical intervention provides a better cosmetic outcome but increases infection risk (SOR: B, meta-analysis of retrospective case series).

Consensus guidelines suggest conservative management for Rockwood grade I to II dislocations and surgical repair for Rockwood grade IV to VI dislocations (SOR: C, expert opinion).

Similar outcomes, except when it comes to return to work

A 2010 Cochrane review of 2 RCTs and one quasi-randomized trial (174 patients, 93% male, moderate to high risk of bias) compared surgical intervention with conservative management of acute AC separations of unspecified Rockwood classification.1 Surgeries included coracoclavicular fixation with a cancellous screw or transfixation of the AC joint with Steinmann pins or Kirschner wires.

Conservative treatment included immobilization of the shoulder using an arm sling for 2 to 4 weeks. Patients were evaluated for a minimum of 12 months with a nonvalidated scoring system that measured pain, motion, and function or strength.

At one year, 63 of 76 patients (83%) in the post-surgical group and 74 of 84 patients (88%) in the conservative intervention group had either good or excellent results with no significant difference in unsatisfactory outcomes (relative risk [RR]=1.49; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.75-2.95). (Fourteen patients—7 in each group—were lost to follow-up.) Moreover, the review found no significant difference in treatment failures requiring a subsequent operation between the groups—11 of 83 (13%) surgical patients and 7 of 91 (8%) conservatively managed patients (RR=1.72; 95% CI, 0.72-4.12).

Notably, regardless of activity level, surgical patients consistently returned to previous work functions later than patients managed conservatively. The mean convalescence time ranged from 8 to 11 weeks for surgical patients and 4 to 6 weeks for conservatively managed patients (P<.05).

A look at cosmetic results and risk of infection

A 2011 meta-analysis of 6 retrospective case series (379 patients, approximately 88% male) compared operative with nonoperative management in patients with acute, closed Rockwood grade III AC dislocations.2 Operative techniques varied; nonoperative patients each received physiotherapy or rehabilitation therapy and most were treated with a sling. Patient follow-up varied from 32 months to 10.8 years.

Four of the included studies suggested that nonoperative management resulted in poorer cosmetic results (methods not defined) compared with the operative group (11 of 115 surgical patients [10%], 74 of 88 nonoperative patients [84%]; risk difference [RD]=−0.79; 95% CI, −0.92 to −0.66; number needed to harm [NNH]=>2). Two of the studies evaluated the duration of sick leave and found a longer leave with operative management (50 operative and 54 nonoperative patients; mean difference=3.3; 95% CI, 2.1-4.5).

Five of the studies observed an increased risk of infection following operative management (8 of 175 [5%] operative patients compared with 0 of 152 [0%] nonoperative patients; RD=0.05; 95% CI, 0.01-0.09; NNH=20).

Recommendations depend on the grade of the injury

The American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine recommends against routine surgical repair for Grade III AC joint separations.3 The College also recommends nonoperative management for patients with grade I to II AC dislocations and surgical repair for patients with grades IV to VI and select grade III AC dislocations.

1. Tamaoki MJS, Belloti JC, Lenza M, et al. Surgical versus conservative interventions for treating acromioclavicular dislocation of the shoulder in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(8):CD007429.

2. Smith TO, Chester R, Pearse EO, et al. Operative versus non-operative management following Rockwood grade III acromioclavicular separation: a meta-analysis of the current evidence base. J Orthopaed Traumatol. 2011;12:19–27.

3. Hegmann KT. Shoulder disorders. In: Occupational Medicine Practice Guidelines. Evaluation and Management of Common Health Problems and Functional Recovery in Workers. 3rd ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine; 2011:1-297.

When not considering the grade of acromioclavicular (AC) joint dislocation, both conservative and surgical management lead to positive outcomes, although surgically managed patients require more time out of work (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, Cochrane review of low-quality randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

For Rockwood grade III dislocations, surgical intervention provides a better cosmetic outcome but increases infection risk (SOR: B, meta-analysis of retrospective case series).

Consensus guidelines suggest conservative management for Rockwood grade I to II dislocations and surgical repair for Rockwood grade IV to VI dislocations (SOR: C, expert opinion).

Similar outcomes, except when it comes to return to work

A 2010 Cochrane review of 2 RCTs and one quasi-randomized trial (174 patients, 93% male, moderate to high risk of bias) compared surgical intervention with conservative management of acute AC separations of unspecified Rockwood classification.1 Surgeries included coracoclavicular fixation with a cancellous screw or transfixation of the AC joint with Steinmann pins or Kirschner wires.

Conservative treatment included immobilization of the shoulder using an arm sling for 2 to 4 weeks. Patients were evaluated for a minimum of 12 months with a nonvalidated scoring system that measured pain, motion, and function or strength.

At one year, 63 of 76 patients (83%) in the post-surgical group and 74 of 84 patients (88%) in the conservative intervention group had either good or excellent results with no significant difference in unsatisfactory outcomes (relative risk [RR]=1.49; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.75-2.95). (Fourteen patients—7 in each group—were lost to follow-up.) Moreover, the review found no significant difference in treatment failures requiring a subsequent operation between the groups—11 of 83 (13%) surgical patients and 7 of 91 (8%) conservatively managed patients (RR=1.72; 95% CI, 0.72-4.12).

Notably, regardless of activity level, surgical patients consistently returned to previous work functions later than patients managed conservatively. The mean convalescence time ranged from 8 to 11 weeks for surgical patients and 4 to 6 weeks for conservatively managed patients (P<.05).

A look at cosmetic results and risk of infection

A 2011 meta-analysis of 6 retrospective case series (379 patients, approximately 88% male) compared operative with nonoperative management in patients with acute, closed Rockwood grade III AC dislocations.2 Operative techniques varied; nonoperative patients each received physiotherapy or rehabilitation therapy and most were treated with a sling. Patient follow-up varied from 32 months to 10.8 years.

Four of the included studies suggested that nonoperative management resulted in poorer cosmetic results (methods not defined) compared with the operative group (11 of 115 surgical patients [10%], 74 of 88 nonoperative patients [84%]; risk difference [RD]=−0.79; 95% CI, −0.92 to −0.66; number needed to harm [NNH]=>2). Two of the studies evaluated the duration of sick leave and found a longer leave with operative management (50 operative and 54 nonoperative patients; mean difference=3.3; 95% CI, 2.1-4.5).

Five of the studies observed an increased risk of infection following operative management (8 of 175 [5%] operative patients compared with 0 of 152 [0%] nonoperative patients; RD=0.05; 95% CI, 0.01-0.09; NNH=20).

Recommendations depend on the grade of the injury

The American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine recommends against routine surgical repair for Grade III AC joint separations.3 The College also recommends nonoperative management for patients with grade I to II AC dislocations and surgical repair for patients with grades IV to VI and select grade III AC dislocations.

When not considering the grade of acromioclavicular (AC) joint dislocation, both conservative and surgical management lead to positive outcomes, although surgically managed patients require more time out of work (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, Cochrane review of low-quality randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

For Rockwood grade III dislocations, surgical intervention provides a better cosmetic outcome but increases infection risk (SOR: B, meta-analysis of retrospective case series).

Consensus guidelines suggest conservative management for Rockwood grade I to II dislocations and surgical repair for Rockwood grade IV to VI dislocations (SOR: C, expert opinion).

Similar outcomes, except when it comes to return to work

A 2010 Cochrane review of 2 RCTs and one quasi-randomized trial (174 patients, 93% male, moderate to high risk of bias) compared surgical intervention with conservative management of acute AC separations of unspecified Rockwood classification.1 Surgeries included coracoclavicular fixation with a cancellous screw or transfixation of the AC joint with Steinmann pins or Kirschner wires.

Conservative treatment included immobilization of the shoulder using an arm sling for 2 to 4 weeks. Patients were evaluated for a minimum of 12 months with a nonvalidated scoring system that measured pain, motion, and function or strength.

At one year, 63 of 76 patients (83%) in the post-surgical group and 74 of 84 patients (88%) in the conservative intervention group had either good or excellent results with no significant difference in unsatisfactory outcomes (relative risk [RR]=1.49; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.75-2.95). (Fourteen patients—7 in each group—were lost to follow-up.) Moreover, the review found no significant difference in treatment failures requiring a subsequent operation between the groups—11 of 83 (13%) surgical patients and 7 of 91 (8%) conservatively managed patients (RR=1.72; 95% CI, 0.72-4.12).

Notably, regardless of activity level, surgical patients consistently returned to previous work functions later than patients managed conservatively. The mean convalescence time ranged from 8 to 11 weeks for surgical patients and 4 to 6 weeks for conservatively managed patients (P<.05).

A look at cosmetic results and risk of infection

A 2011 meta-analysis of 6 retrospective case series (379 patients, approximately 88% male) compared operative with nonoperative management in patients with acute, closed Rockwood grade III AC dislocations.2 Operative techniques varied; nonoperative patients each received physiotherapy or rehabilitation therapy and most were treated with a sling. Patient follow-up varied from 32 months to 10.8 years.

Four of the included studies suggested that nonoperative management resulted in poorer cosmetic results (methods not defined) compared with the operative group (11 of 115 surgical patients [10%], 74 of 88 nonoperative patients [84%]; risk difference [RD]=−0.79; 95% CI, −0.92 to −0.66; number needed to harm [NNH]=>2). Two of the studies evaluated the duration of sick leave and found a longer leave with operative management (50 operative and 54 nonoperative patients; mean difference=3.3; 95% CI, 2.1-4.5).

Five of the studies observed an increased risk of infection following operative management (8 of 175 [5%] operative patients compared with 0 of 152 [0%] nonoperative patients; RD=0.05; 95% CI, 0.01-0.09; NNH=20).

Recommendations depend on the grade of the injury

The American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine recommends against routine surgical repair for Grade III AC joint separations.3 The College also recommends nonoperative management for patients with grade I to II AC dislocations and surgical repair for patients with grades IV to VI and select grade III AC dislocations.

1. Tamaoki MJS, Belloti JC, Lenza M, et al. Surgical versus conservative interventions for treating acromioclavicular dislocation of the shoulder in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(8):CD007429.

2. Smith TO, Chester R, Pearse EO, et al. Operative versus non-operative management following Rockwood grade III acromioclavicular separation: a meta-analysis of the current evidence base. J Orthopaed Traumatol. 2011;12:19–27.

3. Hegmann KT. Shoulder disorders. In: Occupational Medicine Practice Guidelines. Evaluation and Management of Common Health Problems and Functional Recovery in Workers. 3rd ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine; 2011:1-297.

1. Tamaoki MJS, Belloti JC, Lenza M, et al. Surgical versus conservative interventions for treating acromioclavicular dislocation of the shoulder in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(8):CD007429.

2. Smith TO, Chester R, Pearse EO, et al. Operative versus non-operative management following Rockwood grade III acromioclavicular separation: a meta-analysis of the current evidence base. J Orthopaed Traumatol. 2011;12:19–27.

3. Hegmann KT. Shoulder disorders. In: Occupational Medicine Practice Guidelines. Evaluation and Management of Common Health Problems and Functional Recovery in Workers. 3rd ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine; 2011:1-297.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Which interventions can increase breastfeeding duration?

Breastfeeding support, beyond standard care, from lay people or professionals increases both short- and long-term breastfeeding duration (strength of recommendation: B, meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials [RCTs] with demonstrated heterogeneity).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

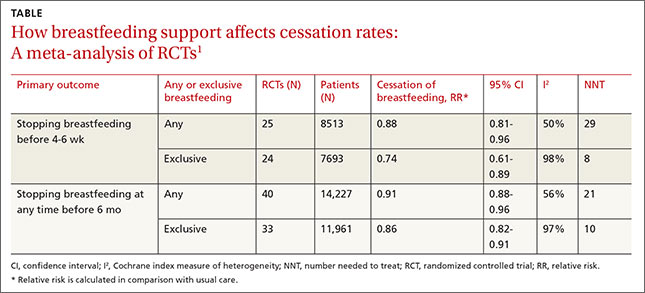

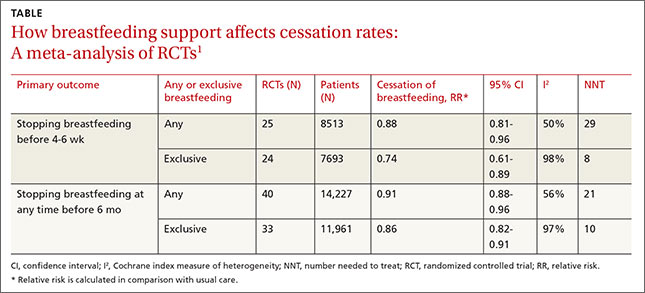

A 2012 Cochrane review of 52 studies (44 RCTs and 8 cluster-randomized trials; N=56,451) assessed the overall effectiveness of multiple supportive measures on decreasing cessation of “any” (partial and exclusive) and “exclusive” breastfeeding compared with usual care.1 Participants were healthy breastfeeding mothers of healthy term babies. Support interventions were defined broadly but included individual and group interactions, as well as contact in person or over the phone by professionals or lay volunteers. Patients were approached proactively or reactively upon request, and the interventions occurred one or more times.

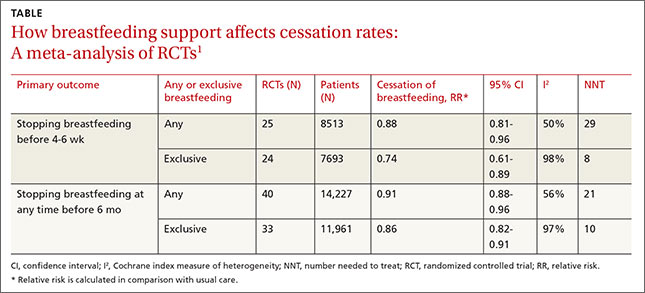

The interventions reduced discontinuation rates among both “exclusive” and “any” breastfeeding mothers (TABLE1). The review found lay and professional support to be equally effective at promoting continuation of breastfeeding. Limitations include a moderate to high amount of heterogeneity, as well as the inherent difficulty of blinding subjects in the studies.

Lay support can make a significant difference in the short term

A 2008 systematic review of 38 RCTs (N=29,020) compared any counseling or behavioral intervention initiated from a clinician’s practice (office or hospital) with usual care.2 The review excluded community and peer-initiated interventions. The reviewers defined breastfeeding duration as follows: initiation (up to 2 weeks), short-term (one to 3 months), intermediate-term (4 to 5 months), long-term (6 to 8 months), and prolonged (9 or more months). Investigators also analyzed breastfeeding rates by “exclusive” and “nonexclusive” (formula supplementation) regimens.

For nonexclusive breastfeeding, the review found interventions to promote breastfeeding improved rates only at initiation (18 RCTs, N=7688; relative risk [RR] for cessation of breastfeeding=1.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.0-1.08; number needed to treat [NNT]=38) and in the short term (18 RCTs, N= 19,358; RR=1.10; 95% CI, 1.02-1.19; NNT=7). For exclusive breastfeeding, interventions improved rates only in the short term (17 RCTs, N=20,552; RR=1.72; 95% CI, 1.0-2.97; NNT=3).

The review found that lay support (defined as counseling or social support from peers) but not professional support was significantly associated with improving rates of both “nonexclusive” and “exclusive’ breastfeeding, but only over the short term (5 RCTs, N not provided; RR=1.22; 95% CI, 1.08-1.37; and 4 RCTs, N not provided; RR=1.65; 95% CI, 1.03-2.63; respectively). As with the Cochrane review, the results for all study groups demonstrated moderate to significant heterogeneity.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Surgeon General, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists all recommend that women be educated about the benefits of breastfeeding and receive supportive interventions before and after delivery.3-6

1. Renfrew MJ, McCormick FM, Wade A, et al. Support for healthy breastfeeding mothers with healthy term babies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD001141.

2. Chung M, Raman G, Trikalinos T, et al. Interventions in primary care to promote breastfeeding: an evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:565-582.

3. United States Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Support Breastfeeding. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General Web site. Available at: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/calls/breastfeeding/. Accessed January 19, 2015.

4. American Academy of Family Physicians. Breastfeeding, Family Physicians Supporting (Position Paper). American Academy of Family Physicians Web site. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/breastfeeding-support.html (updated Nov. 4, 2014). Accessed January 19, 2015.

5. Johnson M, Landers S, Noble L, et al. American Academy of Pediatrics, Section on Breastfeeding. Policy Statement: Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e827–e841.

6. Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 361: Breastfeeding: maternal and infant aspects. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(2 Pt 1):479-480.

Breastfeeding support, beyond standard care, from lay people or professionals increases both short- and long-term breastfeeding duration (strength of recommendation: B, meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials [RCTs] with demonstrated heterogeneity).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2012 Cochrane review of 52 studies (44 RCTs and 8 cluster-randomized trials; N=56,451) assessed the overall effectiveness of multiple supportive measures on decreasing cessation of “any” (partial and exclusive) and “exclusive” breastfeeding compared with usual care.1 Participants were healthy breastfeeding mothers of healthy term babies. Support interventions were defined broadly but included individual and group interactions, as well as contact in person or over the phone by professionals or lay volunteers. Patients were approached proactively or reactively upon request, and the interventions occurred one or more times.

The interventions reduced discontinuation rates among both “exclusive” and “any” breastfeeding mothers (TABLE1). The review found lay and professional support to be equally effective at promoting continuation of breastfeeding. Limitations include a moderate to high amount of heterogeneity, as well as the inherent difficulty of blinding subjects in the studies.

Lay support can make a significant difference in the short term

A 2008 systematic review of 38 RCTs (N=29,020) compared any counseling or behavioral intervention initiated from a clinician’s practice (office or hospital) with usual care.2 The review excluded community and peer-initiated interventions. The reviewers defined breastfeeding duration as follows: initiation (up to 2 weeks), short-term (one to 3 months), intermediate-term (4 to 5 months), long-term (6 to 8 months), and prolonged (9 or more months). Investigators also analyzed breastfeeding rates by “exclusive” and “nonexclusive” (formula supplementation) regimens.

For nonexclusive breastfeeding, the review found interventions to promote breastfeeding improved rates only at initiation (18 RCTs, N=7688; relative risk [RR] for cessation of breastfeeding=1.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.0-1.08; number needed to treat [NNT]=38) and in the short term (18 RCTs, N= 19,358; RR=1.10; 95% CI, 1.02-1.19; NNT=7). For exclusive breastfeeding, interventions improved rates only in the short term (17 RCTs, N=20,552; RR=1.72; 95% CI, 1.0-2.97; NNT=3).

The review found that lay support (defined as counseling or social support from peers) but not professional support was significantly associated with improving rates of both “nonexclusive” and “exclusive’ breastfeeding, but only over the short term (5 RCTs, N not provided; RR=1.22; 95% CI, 1.08-1.37; and 4 RCTs, N not provided; RR=1.65; 95% CI, 1.03-2.63; respectively). As with the Cochrane review, the results for all study groups demonstrated moderate to significant heterogeneity.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Surgeon General, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists all recommend that women be educated about the benefits of breastfeeding and receive supportive interventions before and after delivery.3-6

Breastfeeding support, beyond standard care, from lay people or professionals increases both short- and long-term breastfeeding duration (strength of recommendation: B, meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials [RCTs] with demonstrated heterogeneity).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY