User login

Man, 26, With Sudden-Onset Right Lower Quadrant Pain

A 26-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with a chief complaint of abdominal pain. After triage was complete, he was transported to an examination room, where the clinician obtained the history of presenting illness. The onset of pain was approximately 90 minutes prior to arrival at the ED and woke the patient from a “sound sleep.” He stated that the pain initially started as a “3 out of 10” but had progressed to a “12 out of 10,” and he described it as being in the right lower quadrant of his abdomen, with radiation to his right testicle. However, he was unsure where the pain started or if it was worse in either location. Nausea was the primary associated symptom, but he denied vomiting, diarrhea, fever, dysuria, or hematuria. Last, the patient denied history of trauma.

Medical history was noncontributory: He denied previous gastrointestinal diseases, and there was no history of renal stones, urinary tract infection, or any other genitourinary disease. He had no surgical history. The patient smoked less than a pack of cigarettes per day but denied alcohol or drug use.

Physical examination revealed a young man in moderate discomfort. Despite describing his pain as a “12 out of 10,” he had a blood pressure of 121/72 mm Hg; pulse, 59 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and temperature, 96.8°F. HEENT and cardiovascular, respiratory, musculoskeletal, and neurologic exam results were all within normal limits. Abdominal examination revealed a mildly tender right lower quadrant with deep palpation, but no rebound or guarding. Murphy sign was negative.

Because of the complaint of pain radiating to the testicles, a genitourinary examination was performed. The penis appeared unremarkable, with no lesions or discharge. There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy. The scrotum appeared appropriate in size and was also grossly unremarkable. The left testicle was nontender. However, palpation of the right testicle elicited moderate to severe pain. There was no visible swelling, and there were no palpable hernias or other masses. Cremasteric reflex was assessed bilaterally and deemed to be absent on the right side.

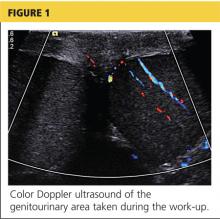

A workup was initiated that included a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and urinalysis; the results of these tests were unremarkable. A differential diagnosis was formed, with emphasis on appendicitis and testicular torsion. Because of the specific nature and location of the pain, both ultrasound and CT of the abdomen/pelvis were considered. It was decided to order the ultrasound, with a plan to perform CT only if ultrasound was unremarkable. The patient was medicated for his pain and the ultrasound commenced. Halfway through the imaging, the clinician and attending physician were summoned to the examination room to review the image seen in Figure 1.

On the next page: Discussion and diagnosis >>

DISCUSSION

Testicular torsion may occur if the testicle twists or rotates on the spermatic cord. The twisting causes arterial ischemia and venous outflow obstruction, cutting off the testicle’s blood supply.1,2 Torsion may be extravaginal or intravaginal, depending on the extent of involvement of the surrounding structures.2

Extravaginal torsion is most commonly seen in neonates and occurs because the entire testicle may freely rotate prior to fixation to the scrotal wall via the tunica vaginalis.2Intravaginal torsion is more common in adolescents and often occurs as a result of a condition known as bell clapper deformity. This congenital abnormality enables the testicle to rotate within the tunica vaginalis and rest transversely in the scrotum instead of in a more vertical orientation.2,3 Torsion occurs if the testicle rotates 90° to 180°, with complete torsion occurring at 360° (torsion may extend to as much as 720°).2 Torsion may also occur as a result of trauma.1

Peak incidence of testicular torsion occurs at ages 13 to 14, but it can occur at any age; torsion affects approximately 1 in 4,000 males younger than 25.2-5 Ninety-five percent of all torsions are intravaginal.2 Torsion is the most common pathology for males who undergo surgical exploration for scrotal pain.3

The main goal in the diagnosis and treatment of torsion is testicular salvage. Torsion is considered a urologic emergency, making early diagnosis and treatment critical to prevent testicular loss. In fact, a review of the relevant literature reveals that the rate of testicular salvage is much higher if the diagnosis is made within 6 to 12 hours.1,2,5 Potential sequelae from delayed treatment include testicular infarction, loss of testicle, infertility problems, infections, cosmetic deformity, and increased risk for testicular malignancy.2

Because many men hesitate to seek medical attention for symptoms of testicular pain and swelling, the primary care clinician should openly discuss testicular disorders, especially with preadolescent males, during testicular examinations.6

Diagnosis

A testicular examination should be performed on any male presenting with a chief complaint of lower abdominal pain, back/flank pain, or any pain that radiates to the groin. The cremasteric reflex should be assessed because it can help differentiate among the causes of testicular pain.7 It is performed by gently stroking the upper inner thigh and observing for contraction of the ipsilateral testicle. One study found that, in cases of torsion, the absence of a cremasteric reflex had a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 88%.7 See the Table for the differential diagnosis for acute testicular pain.

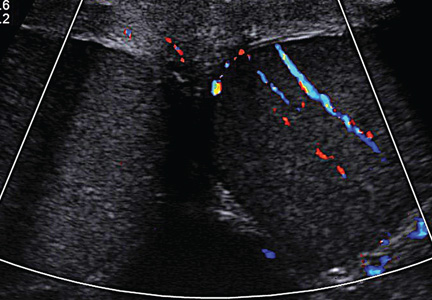

While it is often possible to make the diagnosis of testicular torsion clinically, ultrasound with color Doppler is the diagnostic test of choice in cases for which the cause of acute scrotal pain is unclear.8 Ultrasound provides anatomic detail of the scrotum and its contents, and perfusion is assessed by adding the color Doppler images.8 It is important to note that, while the absence of blood flow is considered diagnostic for testicular torsion, the presence of flow does not necessarily exclude it.4

On the next page: Treatment >>

Treatment

Surgical exploration with intraoperative detorsion and orchiopexy (fixation of the testicle to the scrotal wall) is the mainstay of treatment for testicular torsion.1 Orchiopexy is often performed bilaterally in order to prevent future torsion of the unaffected testicle. In about 40% of males with the bell clapper deformity, the condition is present on both sides.2 Orchiectomy, the complete removal of the testicle, is necessary when the degree of torsion and subsequent ischemia have caused irreversible damage to the testicle.6 In one study in which 2,248 cases of torsion were reviewed, approximately 34% of males required orchiectomy.6

If surgery may be delayed, the clinician may attempt manual detorsion at the bedside. Despite the “open book” method described in many texts—which instructs the practitioner to rotate the testicle laterally—a review of the literature reveals that torsion takes place medially only 70% of the time.1,5 The clinician should always consider this when any attempts at manual detorsion are made and correlate his or her technique with physical examination and the patient’s response.5

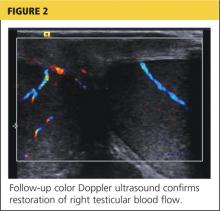

Relief of pain and return of the testicle to its natural longitudinal lie are considered indicators of successful detorsion.1 Color Doppler ultrasound should be used to confirm the return of circulation. However, in one case review of pediatric patients who underwent surgical exploration after manual detorsion, some degree of residual torsion remained in 32%.5 Because of this risk, surgery is still indicated even in cases of successful bedside detorsion.5

On the next page: Case continuation >>

CASE CONTINUATION

The decision to perform bedside ultrasound was made because the diagnosis of testicular torsion is a surgical emergency, and the window of time to prevent complications can be extremely narrow. If the ultrasound had been normal, then a CT scan may have provided additional data on which to base the diagnosis.

The patient was given adequate parenteral pain medication. After color Doppler ultrasound confirmed the torsion, the testicle was laterally rotated approximately 360°. The patient reported alleviation of his symptoms. Color Doppler was again performed to confirm the return of hyperemic blood flow to the affected testicle (Figure 2). The urologist arrived shortly thereafter and the patient was taken to the operating room, where he underwent scrotal exploration and bilateral orchiopexy.

On the next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

A testicular examination should be performed on any male presenting with a chief complaint of lower abdominal pain, back/flank pain, or any pain that radiates to the groin. Testicular torsion is most commonly seen in infants and adolescents but can occur at any age. The condition is a surgical emergency and the goal is testicular salvage, which is most likely to occur before 12 hours have elapsed since the onset of symptoms. An important component of the physical examination is attempting to elicit the cremasteric reflex, which is likely to be absent in the presence of torsion.

The primary care provider’s goal is to rapidly diagnose testicular torsion, then refer the patient immediately to a urologist or ED. The skilled clinician may attempt manual detorsion, based on his/her expertise and comfort level; however, this procedure should never delay prompt surgical intervention.

REFERENCES

1. Eyre RC. Evaluation of the acute scrotum in adults. www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-of-the-acute-scrotum-in-adults. Accessed May 16, 2014.

2. Ogunyemi OI, Weiker M, Abel EJ. Testicular torsion. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2036003-overview. Accessed May 16, 2014.

3. Khan F, Muoka O, Watson GM. Bell clapper testis, torsion, and detorsion: a case report. Case Rep Urol. 2011;2011:631970.

4. Molokwu CN, Somani BK, Goodman CM. Outcomes of scrotal exploration for acute scrotal pain suspicious of testicular torsion: a consecutive case series of 173 patients. BJU Int. 2011;107(6):990-993.

5. Sessions AE, Rabinowitz R, Hulbert WC, et al. Testicular torsion: direction, degree, duration and disinformation. J Urol. 2003;169(2):663-665.

6. Mansbach JM, Forbes P, Peters C. Testicular torsion and risk factors for orchiectomy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:1167-1171.

7. Schmitz D, Safranek S. How useful is a physical exam in diagnosing testicular torsion? J Fam Pract. 2009;58(8):433-434.

8. D’Andrea A, Coppolino F, Cesarano E, et al. US in the assessment of acute scrotum. Crit Ultrasound J. 2013;5(suppl 1):S8. www.criticalultrasound journal.com/content/5/S1/S8/. Accessed May 16, 2014.

A 26-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with a chief complaint of abdominal pain. After triage was complete, he was transported to an examination room, where the clinician obtained the history of presenting illness. The onset of pain was approximately 90 minutes prior to arrival at the ED and woke the patient from a “sound sleep.” He stated that the pain initially started as a “3 out of 10” but had progressed to a “12 out of 10,” and he described it as being in the right lower quadrant of his abdomen, with radiation to his right testicle. However, he was unsure where the pain started or if it was worse in either location. Nausea was the primary associated symptom, but he denied vomiting, diarrhea, fever, dysuria, or hematuria. Last, the patient denied history of trauma.

Medical history was noncontributory: He denied previous gastrointestinal diseases, and there was no history of renal stones, urinary tract infection, or any other genitourinary disease. He had no surgical history. The patient smoked less than a pack of cigarettes per day but denied alcohol or drug use.

Physical examination revealed a young man in moderate discomfort. Despite describing his pain as a “12 out of 10,” he had a blood pressure of 121/72 mm Hg; pulse, 59 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and temperature, 96.8°F. HEENT and cardiovascular, respiratory, musculoskeletal, and neurologic exam results were all within normal limits. Abdominal examination revealed a mildly tender right lower quadrant with deep palpation, but no rebound or guarding. Murphy sign was negative.

Because of the complaint of pain radiating to the testicles, a genitourinary examination was performed. The penis appeared unremarkable, with no lesions or discharge. There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy. The scrotum appeared appropriate in size and was also grossly unremarkable. The left testicle was nontender. However, palpation of the right testicle elicited moderate to severe pain. There was no visible swelling, and there were no palpable hernias or other masses. Cremasteric reflex was assessed bilaterally and deemed to be absent on the right side.

A workup was initiated that included a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and urinalysis; the results of these tests were unremarkable. A differential diagnosis was formed, with emphasis on appendicitis and testicular torsion. Because of the specific nature and location of the pain, both ultrasound and CT of the abdomen/pelvis were considered. It was decided to order the ultrasound, with a plan to perform CT only if ultrasound was unremarkable. The patient was medicated for his pain and the ultrasound commenced. Halfway through the imaging, the clinician and attending physician were summoned to the examination room to review the image seen in Figure 1.

On the next page: Discussion and diagnosis >>

DISCUSSION

Testicular torsion may occur if the testicle twists or rotates on the spermatic cord. The twisting causes arterial ischemia and venous outflow obstruction, cutting off the testicle’s blood supply.1,2 Torsion may be extravaginal or intravaginal, depending on the extent of involvement of the surrounding structures.2

Extravaginal torsion is most commonly seen in neonates and occurs because the entire testicle may freely rotate prior to fixation to the scrotal wall via the tunica vaginalis.2Intravaginal torsion is more common in adolescents and often occurs as a result of a condition known as bell clapper deformity. This congenital abnormality enables the testicle to rotate within the tunica vaginalis and rest transversely in the scrotum instead of in a more vertical orientation.2,3 Torsion occurs if the testicle rotates 90° to 180°, with complete torsion occurring at 360° (torsion may extend to as much as 720°).2 Torsion may also occur as a result of trauma.1

Peak incidence of testicular torsion occurs at ages 13 to 14, but it can occur at any age; torsion affects approximately 1 in 4,000 males younger than 25.2-5 Ninety-five percent of all torsions are intravaginal.2 Torsion is the most common pathology for males who undergo surgical exploration for scrotal pain.3

The main goal in the diagnosis and treatment of torsion is testicular salvage. Torsion is considered a urologic emergency, making early diagnosis and treatment critical to prevent testicular loss. In fact, a review of the relevant literature reveals that the rate of testicular salvage is much higher if the diagnosis is made within 6 to 12 hours.1,2,5 Potential sequelae from delayed treatment include testicular infarction, loss of testicle, infertility problems, infections, cosmetic deformity, and increased risk for testicular malignancy.2

Because many men hesitate to seek medical attention for symptoms of testicular pain and swelling, the primary care clinician should openly discuss testicular disorders, especially with preadolescent males, during testicular examinations.6

Diagnosis

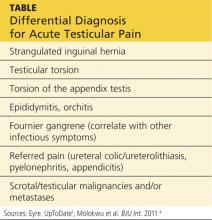

A testicular examination should be performed on any male presenting with a chief complaint of lower abdominal pain, back/flank pain, or any pain that radiates to the groin. The cremasteric reflex should be assessed because it can help differentiate among the causes of testicular pain.7 It is performed by gently stroking the upper inner thigh and observing for contraction of the ipsilateral testicle. One study found that, in cases of torsion, the absence of a cremasteric reflex had a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 88%.7 See the Table for the differential diagnosis for acute testicular pain.

While it is often possible to make the diagnosis of testicular torsion clinically, ultrasound with color Doppler is the diagnostic test of choice in cases for which the cause of acute scrotal pain is unclear.8 Ultrasound provides anatomic detail of the scrotum and its contents, and perfusion is assessed by adding the color Doppler images.8 It is important to note that, while the absence of blood flow is considered diagnostic for testicular torsion, the presence of flow does not necessarily exclude it.4

On the next page: Treatment >>

Treatment

Surgical exploration with intraoperative detorsion and orchiopexy (fixation of the testicle to the scrotal wall) is the mainstay of treatment for testicular torsion.1 Orchiopexy is often performed bilaterally in order to prevent future torsion of the unaffected testicle. In about 40% of males with the bell clapper deformity, the condition is present on both sides.2 Orchiectomy, the complete removal of the testicle, is necessary when the degree of torsion and subsequent ischemia have caused irreversible damage to the testicle.6 In one study in which 2,248 cases of torsion were reviewed, approximately 34% of males required orchiectomy.6

If surgery may be delayed, the clinician may attempt manual detorsion at the bedside. Despite the “open book” method described in many texts—which instructs the practitioner to rotate the testicle laterally—a review of the literature reveals that torsion takes place medially only 70% of the time.1,5 The clinician should always consider this when any attempts at manual detorsion are made and correlate his or her technique with physical examination and the patient’s response.5

Relief of pain and return of the testicle to its natural longitudinal lie are considered indicators of successful detorsion.1 Color Doppler ultrasound should be used to confirm the return of circulation. However, in one case review of pediatric patients who underwent surgical exploration after manual detorsion, some degree of residual torsion remained in 32%.5 Because of this risk, surgery is still indicated even in cases of successful bedside detorsion.5

On the next page: Case continuation >>

CASE CONTINUATION

The decision to perform bedside ultrasound was made because the diagnosis of testicular torsion is a surgical emergency, and the window of time to prevent complications can be extremely narrow. If the ultrasound had been normal, then a CT scan may have provided additional data on which to base the diagnosis.

The patient was given adequate parenteral pain medication. After color Doppler ultrasound confirmed the torsion, the testicle was laterally rotated approximately 360°. The patient reported alleviation of his symptoms. Color Doppler was again performed to confirm the return of hyperemic blood flow to the affected testicle (Figure 2). The urologist arrived shortly thereafter and the patient was taken to the operating room, where he underwent scrotal exploration and bilateral orchiopexy.

On the next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

A testicular examination should be performed on any male presenting with a chief complaint of lower abdominal pain, back/flank pain, or any pain that radiates to the groin. Testicular torsion is most commonly seen in infants and adolescents but can occur at any age. The condition is a surgical emergency and the goal is testicular salvage, which is most likely to occur before 12 hours have elapsed since the onset of symptoms. An important component of the physical examination is attempting to elicit the cremasteric reflex, which is likely to be absent in the presence of torsion.

The primary care provider’s goal is to rapidly diagnose testicular torsion, then refer the patient immediately to a urologist or ED. The skilled clinician may attempt manual detorsion, based on his/her expertise and comfort level; however, this procedure should never delay prompt surgical intervention.

REFERENCES

1. Eyre RC. Evaluation of the acute scrotum in adults. www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-of-the-acute-scrotum-in-adults. Accessed May 16, 2014.

2. Ogunyemi OI, Weiker M, Abel EJ. Testicular torsion. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2036003-overview. Accessed May 16, 2014.

3. Khan F, Muoka O, Watson GM. Bell clapper testis, torsion, and detorsion: a case report. Case Rep Urol. 2011;2011:631970.

4. Molokwu CN, Somani BK, Goodman CM. Outcomes of scrotal exploration for acute scrotal pain suspicious of testicular torsion: a consecutive case series of 173 patients. BJU Int. 2011;107(6):990-993.

5. Sessions AE, Rabinowitz R, Hulbert WC, et al. Testicular torsion: direction, degree, duration and disinformation. J Urol. 2003;169(2):663-665.

6. Mansbach JM, Forbes P, Peters C. Testicular torsion and risk factors for orchiectomy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:1167-1171.

7. Schmitz D, Safranek S. How useful is a physical exam in diagnosing testicular torsion? J Fam Pract. 2009;58(8):433-434.

8. D’Andrea A, Coppolino F, Cesarano E, et al. US in the assessment of acute scrotum. Crit Ultrasound J. 2013;5(suppl 1):S8. www.criticalultrasound journal.com/content/5/S1/S8/. Accessed May 16, 2014.

A 26-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with a chief complaint of abdominal pain. After triage was complete, he was transported to an examination room, where the clinician obtained the history of presenting illness. The onset of pain was approximately 90 minutes prior to arrival at the ED and woke the patient from a “sound sleep.” He stated that the pain initially started as a “3 out of 10” but had progressed to a “12 out of 10,” and he described it as being in the right lower quadrant of his abdomen, with radiation to his right testicle. However, he was unsure where the pain started or if it was worse in either location. Nausea was the primary associated symptom, but he denied vomiting, diarrhea, fever, dysuria, or hematuria. Last, the patient denied history of trauma.

Medical history was noncontributory: He denied previous gastrointestinal diseases, and there was no history of renal stones, urinary tract infection, or any other genitourinary disease. He had no surgical history. The patient smoked less than a pack of cigarettes per day but denied alcohol or drug use.

Physical examination revealed a young man in moderate discomfort. Despite describing his pain as a “12 out of 10,” he had a blood pressure of 121/72 mm Hg; pulse, 59 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and temperature, 96.8°F. HEENT and cardiovascular, respiratory, musculoskeletal, and neurologic exam results were all within normal limits. Abdominal examination revealed a mildly tender right lower quadrant with deep palpation, but no rebound or guarding. Murphy sign was negative.

Because of the complaint of pain radiating to the testicles, a genitourinary examination was performed. The penis appeared unremarkable, with no lesions or discharge. There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy. The scrotum appeared appropriate in size and was also grossly unremarkable. The left testicle was nontender. However, palpation of the right testicle elicited moderate to severe pain. There was no visible swelling, and there were no palpable hernias or other masses. Cremasteric reflex was assessed bilaterally and deemed to be absent on the right side.

A workup was initiated that included a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and urinalysis; the results of these tests were unremarkable. A differential diagnosis was formed, with emphasis on appendicitis and testicular torsion. Because of the specific nature and location of the pain, both ultrasound and CT of the abdomen/pelvis were considered. It was decided to order the ultrasound, with a plan to perform CT only if ultrasound was unremarkable. The patient was medicated for his pain and the ultrasound commenced. Halfway through the imaging, the clinician and attending physician were summoned to the examination room to review the image seen in Figure 1.

On the next page: Discussion and diagnosis >>

DISCUSSION

Testicular torsion may occur if the testicle twists or rotates on the spermatic cord. The twisting causes arterial ischemia and venous outflow obstruction, cutting off the testicle’s blood supply.1,2 Torsion may be extravaginal or intravaginal, depending on the extent of involvement of the surrounding structures.2

Extravaginal torsion is most commonly seen in neonates and occurs because the entire testicle may freely rotate prior to fixation to the scrotal wall via the tunica vaginalis.2Intravaginal torsion is more common in adolescents and often occurs as a result of a condition known as bell clapper deformity. This congenital abnormality enables the testicle to rotate within the tunica vaginalis and rest transversely in the scrotum instead of in a more vertical orientation.2,3 Torsion occurs if the testicle rotates 90° to 180°, with complete torsion occurring at 360° (torsion may extend to as much as 720°).2 Torsion may also occur as a result of trauma.1

Peak incidence of testicular torsion occurs at ages 13 to 14, but it can occur at any age; torsion affects approximately 1 in 4,000 males younger than 25.2-5 Ninety-five percent of all torsions are intravaginal.2 Torsion is the most common pathology for males who undergo surgical exploration for scrotal pain.3

The main goal in the diagnosis and treatment of torsion is testicular salvage. Torsion is considered a urologic emergency, making early diagnosis and treatment critical to prevent testicular loss. In fact, a review of the relevant literature reveals that the rate of testicular salvage is much higher if the diagnosis is made within 6 to 12 hours.1,2,5 Potential sequelae from delayed treatment include testicular infarction, loss of testicle, infertility problems, infections, cosmetic deformity, and increased risk for testicular malignancy.2

Because many men hesitate to seek medical attention for symptoms of testicular pain and swelling, the primary care clinician should openly discuss testicular disorders, especially with preadolescent males, during testicular examinations.6

Diagnosis

A testicular examination should be performed on any male presenting with a chief complaint of lower abdominal pain, back/flank pain, or any pain that radiates to the groin. The cremasteric reflex should be assessed because it can help differentiate among the causes of testicular pain.7 It is performed by gently stroking the upper inner thigh and observing for contraction of the ipsilateral testicle. One study found that, in cases of torsion, the absence of a cremasteric reflex had a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 88%.7 See the Table for the differential diagnosis for acute testicular pain.

While it is often possible to make the diagnosis of testicular torsion clinically, ultrasound with color Doppler is the diagnostic test of choice in cases for which the cause of acute scrotal pain is unclear.8 Ultrasound provides anatomic detail of the scrotum and its contents, and perfusion is assessed by adding the color Doppler images.8 It is important to note that, while the absence of blood flow is considered diagnostic for testicular torsion, the presence of flow does not necessarily exclude it.4

On the next page: Treatment >>

Treatment

Surgical exploration with intraoperative detorsion and orchiopexy (fixation of the testicle to the scrotal wall) is the mainstay of treatment for testicular torsion.1 Orchiopexy is often performed bilaterally in order to prevent future torsion of the unaffected testicle. In about 40% of males with the bell clapper deformity, the condition is present on both sides.2 Orchiectomy, the complete removal of the testicle, is necessary when the degree of torsion and subsequent ischemia have caused irreversible damage to the testicle.6 In one study in which 2,248 cases of torsion were reviewed, approximately 34% of males required orchiectomy.6

If surgery may be delayed, the clinician may attempt manual detorsion at the bedside. Despite the “open book” method described in many texts—which instructs the practitioner to rotate the testicle laterally—a review of the literature reveals that torsion takes place medially only 70% of the time.1,5 The clinician should always consider this when any attempts at manual detorsion are made and correlate his or her technique with physical examination and the patient’s response.5

Relief of pain and return of the testicle to its natural longitudinal lie are considered indicators of successful detorsion.1 Color Doppler ultrasound should be used to confirm the return of circulation. However, in one case review of pediatric patients who underwent surgical exploration after manual detorsion, some degree of residual torsion remained in 32%.5 Because of this risk, surgery is still indicated even in cases of successful bedside detorsion.5

On the next page: Case continuation >>

CASE CONTINUATION

The decision to perform bedside ultrasound was made because the diagnosis of testicular torsion is a surgical emergency, and the window of time to prevent complications can be extremely narrow. If the ultrasound had been normal, then a CT scan may have provided additional data on which to base the diagnosis.

The patient was given adequate parenteral pain medication. After color Doppler ultrasound confirmed the torsion, the testicle was laterally rotated approximately 360°. The patient reported alleviation of his symptoms. Color Doppler was again performed to confirm the return of hyperemic blood flow to the affected testicle (Figure 2). The urologist arrived shortly thereafter and the patient was taken to the operating room, where he underwent scrotal exploration and bilateral orchiopexy.

On the next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

A testicular examination should be performed on any male presenting with a chief complaint of lower abdominal pain, back/flank pain, or any pain that radiates to the groin. Testicular torsion is most commonly seen in infants and adolescents but can occur at any age. The condition is a surgical emergency and the goal is testicular salvage, which is most likely to occur before 12 hours have elapsed since the onset of symptoms. An important component of the physical examination is attempting to elicit the cremasteric reflex, which is likely to be absent in the presence of torsion.

The primary care provider’s goal is to rapidly diagnose testicular torsion, then refer the patient immediately to a urologist or ED. The skilled clinician may attempt manual detorsion, based on his/her expertise and comfort level; however, this procedure should never delay prompt surgical intervention.

REFERENCES

1. Eyre RC. Evaluation of the acute scrotum in adults. www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-of-the-acute-scrotum-in-adults. Accessed May 16, 2014.

2. Ogunyemi OI, Weiker M, Abel EJ. Testicular torsion. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2036003-overview. Accessed May 16, 2014.

3. Khan F, Muoka O, Watson GM. Bell clapper testis, torsion, and detorsion: a case report. Case Rep Urol. 2011;2011:631970.

4. Molokwu CN, Somani BK, Goodman CM. Outcomes of scrotal exploration for acute scrotal pain suspicious of testicular torsion: a consecutive case series of 173 patients. BJU Int. 2011;107(6):990-993.

5. Sessions AE, Rabinowitz R, Hulbert WC, et al. Testicular torsion: direction, degree, duration and disinformation. J Urol. 2003;169(2):663-665.

6. Mansbach JM, Forbes P, Peters C. Testicular torsion and risk factors for orchiectomy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:1167-1171.

7. Schmitz D, Safranek S. How useful is a physical exam in diagnosing testicular torsion? J Fam Pract. 2009;58(8):433-434.

8. D’Andrea A, Coppolino F, Cesarano E, et al. US in the assessment of acute scrotum. Crit Ultrasound J. 2013;5(suppl 1):S8. www.criticalultrasound journal.com/content/5/S1/S8/. Accessed May 16, 2014.