Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a potentially serious sleep disorder in which breathing repeatedly stops and starts during sleep. OSA occurs when the throat muscles intermittently relax and block the airway during sleep. The condition is usually associated with several other chronic medical conditions leading to poor quality of life.

It is estimated that at least 25 million adults are affected by OSA in the United States. Further, the obesity epidemic has increased the prevalence of OSA in the last 2 decades. The prevalence of OSA can be higher in patients undergoing surgery. For example, 70% of the patients undergoing bariatric surgery have OSA, whereas 48% of patients undergoing cardiac surgery have moderate-severe OSA. Alarmingly, in 80% of patients with moderate-severe OSA, the disorder remains undiagnosed and untreated, threatening public health and safety.

Patients with OSA can experience multiple complications when receiving sedatives and opioids during anesthesia (Opperer. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 122[5]:1321). These drugs may diminish the protective arousal reflex triggered by bouts of hypoxia, thereby increasing the risk of prolonged periods of apnea and possibly respiratory arrest. Sedatives and narcotics can decrease pharyngeal muscle tone, which can worsen the existing OSA and increase upper airway resistance. Undiagnosed and untreated OSA may be a contributing factor in many of these complications. Effective screening/diagnosis and treatment of OSA are considered to be important steps to reduce health-care spending, improve chronic disease management, and reduce complications.

The STOP-Bang Questionnaire

The gold standard for the diagnosis of OSA is overnight polysomnography. However, it is time consuming, labor intensive, and costly. The STOP-Bang Questionnaire is considered to be the most validated screening tool for OSA for various populations (Nagappa et al. PLoS One. 2015;10[12]:e0143697).

The STOP-Bang Questionnaire includes four questions used in the STOP Questionnaire plus four additional demographic queries, a total of eight dichotomous (yes/no) questions related to the clinical features of sleep apnea (Snoring, Tiredness, Observed apnea, high blood Pressure, BMI, age, neck circumference, and male gender). For each question, answering “yes” scores 1, a “no” response scores 0, and the total score ranges from 0 to 8 (see www.stopbang.ca). The Questionnaire can be completed quickly and easily (usually within 1-2 minutes), and the overall response rates are typically high (90%-100%). Because of its ease of use, efficiency, and high sensitivity, the STOP-Bang Questionnaire has been widely adopted in various populations, such as sleep clinics and the surgical and general population.

The STOP-Bang Questionnaire has demonstrated a high sensitivity using a cutoff score of greater than or equal to 3: 84% in detecting any sleep apnea (apnea-hypopnea index greater than 5 events/h), 93% in detecting moderate to severe sleep apnea (AHI greater than 15 events/h), and almost 100% in detecting severe sleep apnea (AHI greater than 30 events/h). The corresponding specificities were 56.4%, 43%, and 37% (Chung et al. Anesthesiology. 2008;108[5]:812). If patients score 0-2 on the STOP-Bang Questionnaire, they are considered to be at low risk of OSA, and the possibility of moderate to severe sleep apnea can be ruled out.

The modest specificity of the STOP-Bang Questionnaire may yield moderately high false-positive cases. This may lead to unwanted sleep study referrals and increased health care expenditure. There are several ways by which the specificity can be improved, thereby decreasing false-positive rates.

Setting a threshold for the STOP-Bang scores in different population

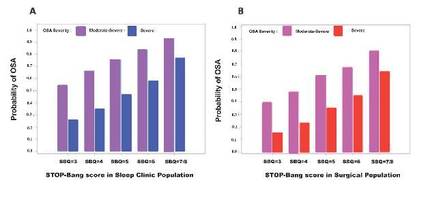

The main advantage of the STOP-Bang scores is its flexibility to use different scores for different populations. For example, in a bariatric population, a STOP-Bang score of greater than or equal to 4 can be used. On the other hand, in an ENT population, where we would like to identify a majority of patients with moderate-severe OSA, a STOP-Bang score of greater than or equal to 5 can be used. In the sleep clinic population, as the STOP-Bang score cut-off increased from 3 to 8, the specificity increased from 52% to 100%, and the PPV increased continuously from 93% to 100% for any OSA (AHI greater than or equal to 5). A similar pattern was seen in the surgical population, as the STOP-Bang score cutoff increased from 3 to greater than or equal to 7, the specificity increased from 40% to 98%, and the PPV increased from 75% to 82% for any OSA (AHI greater than or equal to 5) (Nagappa et al. PLoS One. 2015;10[12]:e0143697).

Regional practices should decide the appropriate threshold of screening tests, after considering the implications for missed diagnoses and cost of care. There is a trade-off between sensitivity and specificity. At lower thresholds, there is improved sensitivity with potentially increased resource utilization, whereas increasing the threshold will result in loss of sensitivity and increased false-negative rates but improved resource utilization. A higher threshold should be adopted in the population with a lower prevalence of OSA.