User login

Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), which include intrauterine devices (IUDs), implants, and injectables, are being offered to more and more women because of their demonstrated safety, efficacy, and convenience. In other countries, as many as 50% of all women use an IUD, but the United States has been slow to adopt this option.1 In 2002, approximately 2% of US women used an IUD.2 That percentage rose to 5.2% between 2006 and 2008, according to a recent survey.3 In that survey, women consistently expressed a high degree of satisfaction with this method of contraception.3

So why aren’t more US women using an IUD?

A general fear of the IUD persists. Women may not even know why they fear the device; they may have simply heard that it is “bad for you.” The negative press the IUD has received in this country probably is related to poor outcomes associated with use of the Dalkon Shield IUD in the 1970s. As a reminder, the Dalkon Shield was blamed for many cases of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and other negative sequelae as a result of poor patient selection. In addition, some authorities believe the design of the device was severely flawed, with a string that permitted bacteria to get from the vagina to the uterus and tubes.

Today, clinicians and many patients are better educated about the prevention of chlamydia, the primary causative organism of PID and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs); patients also are better informed about safe sex practices. We now know that women should be screened for behaviors that could increase their risk for PID and render them poor candidates for the IUD.

Clinicians also have expressed concerns about reimbursement issues related to the IUD, as well as confusion and difficulty with insertion procedures and the potential for litigation. In this article, I address some of these issues in an attempt to increase the use of this highly effective contraceptive.

What’s available today

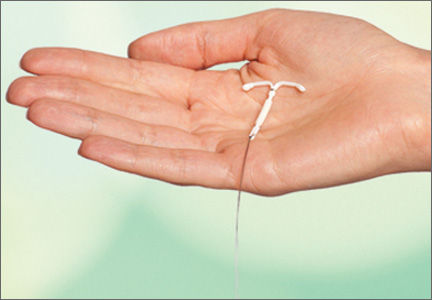

Today there are three IUDs available to US women (FIGURE):

The Copper IUD (ParaGard)—This device can be used for at least 10 years, although, in many countries, it is considered “permanent reversible contraception.” It has the advantage of being nonhormonal, making it an important option for women who cannot or will not use a hormonal contraceptive. Pregnancy is prevented through a “foreign body” effect and the spermicidal action of copper ions. The combination of these two influences prevents fertilization.4

The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) (Mirena)—This IUD is recommended for 5 years of use but may remain effective for as long as 7 years. It contains 52 mg of levonorgestrel, which it releases at a rate of approximately 20 μg/day. In addition to the foreign body effect, this IUD prevents pregnancy through progestogenic mechanisms: It thickens cervical mucus, thins the endometrium, and reduces sperm capacitation.5

The "mini" LNG-IUS (Skyla)—This newly marketed IUD is recommended for 3 years of use. It contains 13.5 mg of levonorgestrel, which it releases at a rate of 14 μg/day. It has the same mechanism of action as Mirena but may be easier to insert owing to its slightly smaller size and preloaded inserter.

Myth #1: The IUD is not suitable for teens and nulliparous women

This myth arose out of concerns about the smaller uterine cavity and cervical diameter of teens and nulliparous women. Today we know that an IUD can be inserted safely in this population. Moreover, because adolescents are at high risk for unintended pregnancy, they stand to benefit uniquely from LARC options, including the IUD. As the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends in a recent Committee Opinion on adolescents and LARCs, the IUD should be a “first-line” option for all women of reproductive age.6

Myth #2: An IUD should not be inserted immediately after childbirth

For many years, it was assumed that an IUD should be inserted in the postpartum period only after uterine involution was completed. However, in 2010, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, which included the following recommendations for breastfeeding or non–breast-feeding women:

• Mirena was given a Level 2 recommendation (advantages outweigh risks) for insertion within 10 minutes after delivery of the placenta

• The copper IUD was given a Level 1 recommendation (no restrictions) for insertion within the same time interval

• From 10 minutes to 4 weeks postpartum, both devices have a Level 2 recommendation for insertion

• Beyond 4 weeks, both devices have a Level 1 recommendation for insertion.7

Immediate post-delivery insertion of an IUD has several benefits, including:

• a reduction in the risk of unintended pregnancy in women who are not breastfeeding

• providing new mothers with a LARC method.

Myth #3: Antibiotics and NSAIDs should be administered

This myth arose from concerns about PID and insertion-related pain. However, a Cochrane Database review found no benefit for prophylactic use of antibiotics prior to insertion of the copper or LNG-IUS devices to prevent PID.8

In fact, data indicate that the incidence of PID is low among women who are appropriate candidates for an IUD. Similarly, Allen and colleagues found that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) did not ameliorate symptoms of cramping during or immediately after insertion of an IUD.9

Myth #4: IUD insertion is difficult

In reality, both the copper IUD and Mirena are easy to insert. In addition, the smaller LNG-IUS (Skyla) comes more completely preloaded in its inserter. In a published Phase 2 trial comparing Mirena with two smaller, lower-dose levonorgestrel-releasing devices, with the lowest-dose product corresponding to the marketed Skyla product, all 738 women given Mirena or the smaller devices experienced successful placement, with 98.5% of placements achieved on the first attempt.10

Various studies have been conducted to evaluate methods to ease insertion, including use of intracervical lidocaine, vaginal and/or oral administration of misoprostol (Cytotec), and vaginal estrogen creams. None was found to be effective in controlled trials. (See the sidebar, “Data-driven tactics for reducing pain on IUD insertion,” by Jennifer Gunter, MD, on page 28.) In the small percentage of women in whom it is difficult to pass a uterine sound through the external and internal os, cervical dilators may be beneficial. Gentle, progressive dilation can be accomplished easily with minimal discomfort to the patient, easing IUD insertion dramatically.

If a clinician does not insert IUDs on a frequent basis, it is prudent to look over the insertion procedure prior to the patient’s arrival. The procedure then can be reviewed with the patient as part of informed consent, which should be documented in the chart.

No steps in the recommended insertion procedure should be omitted, and charting should reflect each step:

1. Perform a bimanual exam

2. Document the appearance of the vagina and cervix

3. Use betadine or another cleansing solution on the cervical portio

4. Apply the tenaculum to the cervix (anterior lip if the uterus is anteverted, posterior lip if it is retroverted)

5. Sound the uterus to determine the optimal depth of IUD insertion. (The recommended uterine depth is 6 to 10 cm. A smaller uterus increases the likelihood of perforation, pain, and expulsion.)

6. Insert the IUD (and document the ease or difficulty of insertion)

7. Trim the string to an appropriate length

8. Assess the patient’s condition after insertion

9. Schedule a return visit in 4 weeks.

Related Article Let’s increase our use of IUDs and improve contraceptive effectiveness in this country Robert L. Barbieri, MD

Myth #5: Perforation is common

Uterine perforation occurs in approximately 1 in every 1,000 insertions.11 If perforation occurs with a copper IUD, remove the device to prevent the formation of intraperitoneal adhesions.12 The LNG-IUS devices do not produce this reaction, although most experts agree that they should be removed when a perforation occurs.13

Anecdotal evidence suggests that perforation may be more common among breastfeeding women, but this finding is far from definitive.

How to select an IUD for a patient: 3 case studies

CASE 1: Heavy bleeding and signs of endometriosis

Amelia, a 26-year-old nulliparous white woman, visits your office for routine examination and asks about her contraceptive options. She has no notable medical history. She has a body mass index (BMI) of 20.2 kg/m2 and exercises regularly. Menarche occurred at age 13. Her menstrual cycles are regular but are getting heavier; she now “soaks” a tampon every hour. She also complains that her cramps are more difficult to manage. She takes ibuprofen 600 mg every 6 hours during the days of heaviest bleeding and cramping, but that approach doesn’t seem to be effective lately. She is in a stable sexual relationship with her boyfriend of 2 years, now her fiancé. They have been using condoms consistently as contraception but don’t plan to start a family for a “few years.” Amelia reports that their sex life is good, although she has been experiencing pain with deep penetration for about 6 months.

Examination reveals a clear cervix and nontender uterus, although the uterus is retroverted. Palpation of the ovaries indicates that they are normal. Her main complaints: dysmenorrhea and heavy menstrual bleeding.

What contraceptive would you suggest?

Amelia would be a good candidate for the LNG-IUS because she is in a stable relationship and wants to postpone pregnancy for several years. Although she has some symptoms suggestive of endometriosis (dyspareunia), they could be relieved by this method.14 Because thinning of the endometrial lining is an inherent mechanism of action of the LNG-IUS, this method could reduce her heavy bleeding.

She should be advised of the risks and benefits of the LNG-IUS, which can be inserted when she begins her next menstrual cycle.

CASE 2: Mother of two with no immediate desire for pregnancy

Tamika is a 19-year-old black woman (G2P2) who has arrived at your clinic for her 6-week postpartum visit. She is not breastfeeding. Her BMI is 25.7 kg/m2. She reports that her baby and 2-year-old are doing “OK” and says she does not want to get pregnant again anytime soon. She is in a relationship with the father of her baby and says he is “working a good job and taking care of me.” Her menstrual cycles have always been normal, with no cramping or heavy bleeding.

Examination reveals that her cervix is clear, her uterus is anteverted and nontender, and her ovaries appear to be normal.

Would this patient be a good candidate for a LARC?

Tamika is an excellent candidate for the copper IUD or LNG-IUS and should be educated about both methods. If she chooses an IUD, it can be inserted at the start of her next menstrual period.

These first two cases illustrate the importance of making no assumptions on the basis of general patient characteristics. Although Tamika may appear to be at greater risk for STI than Amelia, such “typecasting” may lead to inappropriate counseling.

Related Article Malpositioned IUDs: When you should intervene (and when you should not)

At the time of IUD insertion, both patients should be instructed to check for the IUD string periodically, and this recommendation should be documented in their charts.

CASE 3: Anovulatory patient with heavy periods

Mary, 25, is a nulliparous Hispanic woman who has been referred by her primary care provider. She has a BMI of 35.4 kg/m2 and has had menstrual problems since menarche at the age of 14. She reports that her periods are irregular and very heavy, with intermittent pelvic pain that she manages, with some success, with ibuprofen. She has never had a sexual relationship, but she has a boyfriend now and asks about her contraceptive options.

On examination, you discover that Mary has pubic hair distribution over her inner thigh, with primary escutcheon and acanthosis nigricans on the inner thigh. Her vulva is marked by multiple sebaceous cysts, and a speculum exam shows a large amount of estrogenic mucus and a clear cervix. Her uterus is anteverted and nontender. Her ovaries are palpable but may be enlarged, and transvaginal ultrasound reveals that they are cystic. Her diagnosis: hirsutism with probable polycystic ovary syndrome.

Would an IUD be appropriate?

Mary is not a good candidate for an IUD. Neither the copper IUD nor the LNG-IUS would suppress ovarian function sufficiently to reduce the growth of multiple follicles that occurs with polycystic ovary syndrome. She would benefit from a hormonal method (specifically, a combination oral contraceptive) to suppress follicular activity.

Time for a renaissance?

The IUD may be making a comeback. With the unintended pregnancy rate remaining consistently at about 50%, it is important that we offer our patients contraceptive methods that maximize efficacy, safety, and convenience. Today’s IUDs meet all these criteria.

Data-driven tactics for reducing pain on IUD insertion

Many patients worry about the potential for pain with IUD insertion—and this concern can dissuade them from choosing the IUD as a contraceptive. This is regrettable because the IUD has the highest satisfaction rating among reversible contraceptives, as well as the greatest efficacy.

How much pain can your patient expect? In one recent prospective study involving 40 women who received either 1.2% lidocaine or saline infused 3 minutes before IUD insertion, 33% of women reported a pain score of 5 or higher (on a scale of 0–10) at tenaculum placement. This finding means that two-thirds of women had a pain score of 4 or lower. In fact, 46% of women had a pain score of 2 or below.15 (The mean pain scores for insertion were similar with lidocaine and placebo [3.0 vs 3.7, respectively; P=.4]).

Pain reducing options

The evidence validates (or fails to disprove) the value of the following interventions to make insertion more comfortable for patients:

• Naproxen (550 mg) administration 40 minutes prior to insertion. One small study found it to be better than placebo.9

• Nonopioid pain medication. One small, randomized, double-blinded clinical trial found that tramadol was even more effective than naproxen at relieving insertion-related pain.16

• Injection of lidocaine into the cervix. Although this intervention is common, data supporting it are scarce. One small, high-quality study found no benefit, compared with placebo. However, if you have had success with this approach in the past, I would not discourage you from continuing to offer it, as a single small study is insufficient to disprove it.15 More data are needed.

• Keeping the patient calm. Anxiety increases the perception of pain. Studies have demonstrated that women who expect pain at insertion are more likely to experience it. Encourage the patient to breathe diaphragmatically, and remind her that she is likely to be very happy with her choice of the IUD.

Many other interventions don’t seem to be effective, although they may be offered frequently. Unproven methods include administration of NSAIDs other than naproxen, use of misoprostol (which can increase cramping), application of topical lidocaine to the cervix, and insertion during menses (although the LNG-IUS is inserted during the menstrual period to render it effective during the first month of use).

The studies described here come from the general population of reproductive-age women. If a patient has cervical scarring or a history of difficult or painful insertion, she may be more likely to experience pain, and these data may not apply to her.

—Jennifer Gunter, MD

Dr. Gunter is an ObGyn in San Francisco. She is the author of The Preemie Primer: A Complete Guide for Parents of Premature Babies—from Birth through the Toddler Years and Beyond (Da Capo Press, 2010). Dr. Gunter blogs at www.drjengunter.com, and you can find her on Twitter at @DrJenGunter. She is an OBG Management Contributing Editor.

Dr. Gunter reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. 2006 Pan EU study on female contraceptives [unpublished data]. Bayer Schering Pharma; 2007.

2. Moser WD, Martinex GM, Chandra A, Abma JC, Wilson SJ. Use of contraception and use of family planning services in the United States: 1982–2002. Advance data from vital and health statistics; No. 350. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics. 2004;350:1–36.

3. Finer LB, Jerman J, Kavanaugh ML. Changes in use of long-acting contraceptive methods in the United States, 2007–2009. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(4):893–897.

4. Ortiz ME, Croxatto HB, Bardin CW. Mechanisms of action of intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1996;51(12 Suppl):S42–S51.

5. Barbosa I, Olsson SE, Odlind V, Goncalves T, Coutinho E. Ovarian function after seven years’ use of a levonorgestrel IUD. Adv Contracept. 1995;11(2):85–95.

6. Committee on Adolescent Health Care Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion #539: Adolescents and long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(4):983–988.

7. CDC. US medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2010. MMWR Early Release. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr59e0528.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2013.

8. Grimes DA, Lopez LM, Schulz KF. Antibiotics for prevention with IUDs. Cochrane summaries. http://summaries.cochrane.org/CD001327/antibiotics-for-prevention-with-iuds. Published May 16, 2012. Accessed August 18, 2013.

9. Allen RH, Bartz D, Grimes DA, Hubacher D, O’Brien P. Interventions for pain with intrauterine device insertion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009; (3):CD007373.

10. Gemzell-Danielsson K, Schellschmidt I, Apter D. A randomized phase II study describing the efficacy, bleeding profile, and safety of two low-dose levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive systems and Mirena. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(3):616-622.e1-e3.

11. Grimes DA. Intrauterine devices (IUDs). In: Hatcher RA, ed. Contraceptive Technology. 19th ed. New York, New York: Ardent Media; 2007:117–143.

12. Hatcher RA. Contraceptive Technology. New York, New York: Ardent Media; 2011.

13. Adoni A, Ben C. The management of intrauterine devices following uterine perforation. Contraception. 1991;43(1):77.

14. Petta CA, Ferriani RA, Abrao MS, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and a depot GnRH analogue for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(7):1993–1998.

15. Nelson AL, Fong JK. Intrauterine infusion of lidocaine does not reduce pain scores during IUD insertion. Contraception. 2013;88(1):37–40.

16. Karabayirli S, Ayrim AA, Muslu B. Comparison of the analgesic effects of oral tramadol and naproxen sodium on pain relief during IUD insertion. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19(5):581–584.

Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), which include intrauterine devices (IUDs), implants, and injectables, are being offered to more and more women because of their demonstrated safety, efficacy, and convenience. In other countries, as many as 50% of all women use an IUD, but the United States has been slow to adopt this option.1 In 2002, approximately 2% of US women used an IUD.2 That percentage rose to 5.2% between 2006 and 2008, according to a recent survey.3 In that survey, women consistently expressed a high degree of satisfaction with this method of contraception.3

So why aren’t more US women using an IUD?

A general fear of the IUD persists. Women may not even know why they fear the device; they may have simply heard that it is “bad for you.” The negative press the IUD has received in this country probably is related to poor outcomes associated with use of the Dalkon Shield IUD in the 1970s. As a reminder, the Dalkon Shield was blamed for many cases of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and other negative sequelae as a result of poor patient selection. In addition, some authorities believe the design of the device was severely flawed, with a string that permitted bacteria to get from the vagina to the uterus and tubes.

Today, clinicians and many patients are better educated about the prevention of chlamydia, the primary causative organism of PID and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs); patients also are better informed about safe sex practices. We now know that women should be screened for behaviors that could increase their risk for PID and render them poor candidates for the IUD.

Clinicians also have expressed concerns about reimbursement issues related to the IUD, as well as confusion and difficulty with insertion procedures and the potential for litigation. In this article, I address some of these issues in an attempt to increase the use of this highly effective contraceptive.

What’s available today

Today there are three IUDs available to US women (FIGURE):

The Copper IUD (ParaGard)—This device can be used for at least 10 years, although, in many countries, it is considered “permanent reversible contraception.” It has the advantage of being nonhormonal, making it an important option for women who cannot or will not use a hormonal contraceptive. Pregnancy is prevented through a “foreign body” effect and the spermicidal action of copper ions. The combination of these two influences prevents fertilization.4

The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) (Mirena)—This IUD is recommended for 5 years of use but may remain effective for as long as 7 years. It contains 52 mg of levonorgestrel, which it releases at a rate of approximately 20 μg/day. In addition to the foreign body effect, this IUD prevents pregnancy through progestogenic mechanisms: It thickens cervical mucus, thins the endometrium, and reduces sperm capacitation.5

The "mini" LNG-IUS (Skyla)—This newly marketed IUD is recommended for 3 years of use. It contains 13.5 mg of levonorgestrel, which it releases at a rate of 14 μg/day. It has the same mechanism of action as Mirena but may be easier to insert owing to its slightly smaller size and preloaded inserter.

Myth #1: The IUD is not suitable for teens and nulliparous women

This myth arose out of concerns about the smaller uterine cavity and cervical diameter of teens and nulliparous women. Today we know that an IUD can be inserted safely in this population. Moreover, because adolescents are at high risk for unintended pregnancy, they stand to benefit uniquely from LARC options, including the IUD. As the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends in a recent Committee Opinion on adolescents and LARCs, the IUD should be a “first-line” option for all women of reproductive age.6

Myth #2: An IUD should not be inserted immediately after childbirth

For many years, it was assumed that an IUD should be inserted in the postpartum period only after uterine involution was completed. However, in 2010, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, which included the following recommendations for breastfeeding or non–breast-feeding women:

• Mirena was given a Level 2 recommendation (advantages outweigh risks) for insertion within 10 minutes after delivery of the placenta

• The copper IUD was given a Level 1 recommendation (no restrictions) for insertion within the same time interval

• From 10 minutes to 4 weeks postpartum, both devices have a Level 2 recommendation for insertion

• Beyond 4 weeks, both devices have a Level 1 recommendation for insertion.7

Immediate post-delivery insertion of an IUD has several benefits, including:

• a reduction in the risk of unintended pregnancy in women who are not breastfeeding

• providing new mothers with a LARC method.

Myth #3: Antibiotics and NSAIDs should be administered

This myth arose from concerns about PID and insertion-related pain. However, a Cochrane Database review found no benefit for prophylactic use of antibiotics prior to insertion of the copper or LNG-IUS devices to prevent PID.8

In fact, data indicate that the incidence of PID is low among women who are appropriate candidates for an IUD. Similarly, Allen and colleagues found that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) did not ameliorate symptoms of cramping during or immediately after insertion of an IUD.9

Myth #4: IUD insertion is difficult

In reality, both the copper IUD and Mirena are easy to insert. In addition, the smaller LNG-IUS (Skyla) comes more completely preloaded in its inserter. In a published Phase 2 trial comparing Mirena with two smaller, lower-dose levonorgestrel-releasing devices, with the lowest-dose product corresponding to the marketed Skyla product, all 738 women given Mirena or the smaller devices experienced successful placement, with 98.5% of placements achieved on the first attempt.10

Various studies have been conducted to evaluate methods to ease insertion, including use of intracervical lidocaine, vaginal and/or oral administration of misoprostol (Cytotec), and vaginal estrogen creams. None was found to be effective in controlled trials. (See the sidebar, “Data-driven tactics for reducing pain on IUD insertion,” by Jennifer Gunter, MD, on page 28.) In the small percentage of women in whom it is difficult to pass a uterine sound through the external and internal os, cervical dilators may be beneficial. Gentle, progressive dilation can be accomplished easily with minimal discomfort to the patient, easing IUD insertion dramatically.

If a clinician does not insert IUDs on a frequent basis, it is prudent to look over the insertion procedure prior to the patient’s arrival. The procedure then can be reviewed with the patient as part of informed consent, which should be documented in the chart.

No steps in the recommended insertion procedure should be omitted, and charting should reflect each step:

1. Perform a bimanual exam

2. Document the appearance of the vagina and cervix

3. Use betadine or another cleansing solution on the cervical portio

4. Apply the tenaculum to the cervix (anterior lip if the uterus is anteverted, posterior lip if it is retroverted)

5. Sound the uterus to determine the optimal depth of IUD insertion. (The recommended uterine depth is 6 to 10 cm. A smaller uterus increases the likelihood of perforation, pain, and expulsion.)

6. Insert the IUD (and document the ease or difficulty of insertion)

7. Trim the string to an appropriate length

8. Assess the patient’s condition after insertion

9. Schedule a return visit in 4 weeks.

Related Article Let’s increase our use of IUDs and improve contraceptive effectiveness in this country Robert L. Barbieri, MD

Myth #5: Perforation is common

Uterine perforation occurs in approximately 1 in every 1,000 insertions.11 If perforation occurs with a copper IUD, remove the device to prevent the formation of intraperitoneal adhesions.12 The LNG-IUS devices do not produce this reaction, although most experts agree that they should be removed when a perforation occurs.13

Anecdotal evidence suggests that perforation may be more common among breastfeeding women, but this finding is far from definitive.

How to select an IUD for a patient: 3 case studies

CASE 1: Heavy bleeding and signs of endometriosis

Amelia, a 26-year-old nulliparous white woman, visits your office for routine examination and asks about her contraceptive options. She has no notable medical history. She has a body mass index (BMI) of 20.2 kg/m2 and exercises regularly. Menarche occurred at age 13. Her menstrual cycles are regular but are getting heavier; she now “soaks” a tampon every hour. She also complains that her cramps are more difficult to manage. She takes ibuprofen 600 mg every 6 hours during the days of heaviest bleeding and cramping, but that approach doesn’t seem to be effective lately. She is in a stable sexual relationship with her boyfriend of 2 years, now her fiancé. They have been using condoms consistently as contraception but don’t plan to start a family for a “few years.” Amelia reports that their sex life is good, although she has been experiencing pain with deep penetration for about 6 months.

Examination reveals a clear cervix and nontender uterus, although the uterus is retroverted. Palpation of the ovaries indicates that they are normal. Her main complaints: dysmenorrhea and heavy menstrual bleeding.

What contraceptive would you suggest?

Amelia would be a good candidate for the LNG-IUS because she is in a stable relationship and wants to postpone pregnancy for several years. Although she has some symptoms suggestive of endometriosis (dyspareunia), they could be relieved by this method.14 Because thinning of the endometrial lining is an inherent mechanism of action of the LNG-IUS, this method could reduce her heavy bleeding.

She should be advised of the risks and benefits of the LNG-IUS, which can be inserted when she begins her next menstrual cycle.

CASE 2: Mother of two with no immediate desire for pregnancy

Tamika is a 19-year-old black woman (G2P2) who has arrived at your clinic for her 6-week postpartum visit. She is not breastfeeding. Her BMI is 25.7 kg/m2. She reports that her baby and 2-year-old are doing “OK” and says she does not want to get pregnant again anytime soon. She is in a relationship with the father of her baby and says he is “working a good job and taking care of me.” Her menstrual cycles have always been normal, with no cramping or heavy bleeding.

Examination reveals that her cervix is clear, her uterus is anteverted and nontender, and her ovaries appear to be normal.

Would this patient be a good candidate for a LARC?

Tamika is an excellent candidate for the copper IUD or LNG-IUS and should be educated about both methods. If she chooses an IUD, it can be inserted at the start of her next menstrual period.

These first two cases illustrate the importance of making no assumptions on the basis of general patient characteristics. Although Tamika may appear to be at greater risk for STI than Amelia, such “typecasting” may lead to inappropriate counseling.

Related Article Malpositioned IUDs: When you should intervene (and when you should not)

At the time of IUD insertion, both patients should be instructed to check for the IUD string periodically, and this recommendation should be documented in their charts.

CASE 3: Anovulatory patient with heavy periods

Mary, 25, is a nulliparous Hispanic woman who has been referred by her primary care provider. She has a BMI of 35.4 kg/m2 and has had menstrual problems since menarche at the age of 14. She reports that her periods are irregular and very heavy, with intermittent pelvic pain that she manages, with some success, with ibuprofen. She has never had a sexual relationship, but she has a boyfriend now and asks about her contraceptive options.

On examination, you discover that Mary has pubic hair distribution over her inner thigh, with primary escutcheon and acanthosis nigricans on the inner thigh. Her vulva is marked by multiple sebaceous cysts, and a speculum exam shows a large amount of estrogenic mucus and a clear cervix. Her uterus is anteverted and nontender. Her ovaries are palpable but may be enlarged, and transvaginal ultrasound reveals that they are cystic. Her diagnosis: hirsutism with probable polycystic ovary syndrome.

Would an IUD be appropriate?

Mary is not a good candidate for an IUD. Neither the copper IUD nor the LNG-IUS would suppress ovarian function sufficiently to reduce the growth of multiple follicles that occurs with polycystic ovary syndrome. She would benefit from a hormonal method (specifically, a combination oral contraceptive) to suppress follicular activity.

Time for a renaissance?

The IUD may be making a comeback. With the unintended pregnancy rate remaining consistently at about 50%, it is important that we offer our patients contraceptive methods that maximize efficacy, safety, and convenience. Today’s IUDs meet all these criteria.

Data-driven tactics for reducing pain on IUD insertion

Many patients worry about the potential for pain with IUD insertion—and this concern can dissuade them from choosing the IUD as a contraceptive. This is regrettable because the IUD has the highest satisfaction rating among reversible contraceptives, as well as the greatest efficacy.

How much pain can your patient expect? In one recent prospective study involving 40 women who received either 1.2% lidocaine or saline infused 3 minutes before IUD insertion, 33% of women reported a pain score of 5 or higher (on a scale of 0–10) at tenaculum placement. This finding means that two-thirds of women had a pain score of 4 or lower. In fact, 46% of women had a pain score of 2 or below.15 (The mean pain scores for insertion were similar with lidocaine and placebo [3.0 vs 3.7, respectively; P=.4]).

Pain reducing options

The evidence validates (or fails to disprove) the value of the following interventions to make insertion more comfortable for patients:

• Naproxen (550 mg) administration 40 minutes prior to insertion. One small study found it to be better than placebo.9

• Nonopioid pain medication. One small, randomized, double-blinded clinical trial found that tramadol was even more effective than naproxen at relieving insertion-related pain.16

• Injection of lidocaine into the cervix. Although this intervention is common, data supporting it are scarce. One small, high-quality study found no benefit, compared with placebo. However, if you have had success with this approach in the past, I would not discourage you from continuing to offer it, as a single small study is insufficient to disprove it.15 More data are needed.

• Keeping the patient calm. Anxiety increases the perception of pain. Studies have demonstrated that women who expect pain at insertion are more likely to experience it. Encourage the patient to breathe diaphragmatically, and remind her that she is likely to be very happy with her choice of the IUD.

Many other interventions don’t seem to be effective, although they may be offered frequently. Unproven methods include administration of NSAIDs other than naproxen, use of misoprostol (which can increase cramping), application of topical lidocaine to the cervix, and insertion during menses (although the LNG-IUS is inserted during the menstrual period to render it effective during the first month of use).

The studies described here come from the general population of reproductive-age women. If a patient has cervical scarring or a history of difficult or painful insertion, she may be more likely to experience pain, and these data may not apply to her.

—Jennifer Gunter, MD

Dr. Gunter is an ObGyn in San Francisco. She is the author of The Preemie Primer: A Complete Guide for Parents of Premature Babies—from Birth through the Toddler Years and Beyond (Da Capo Press, 2010). Dr. Gunter blogs at www.drjengunter.com, and you can find her on Twitter at @DrJenGunter. She is an OBG Management Contributing Editor.

Dr. Gunter reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), which include intrauterine devices (IUDs), implants, and injectables, are being offered to more and more women because of their demonstrated safety, efficacy, and convenience. In other countries, as many as 50% of all women use an IUD, but the United States has been slow to adopt this option.1 In 2002, approximately 2% of US women used an IUD.2 That percentage rose to 5.2% between 2006 and 2008, according to a recent survey.3 In that survey, women consistently expressed a high degree of satisfaction with this method of contraception.3

So why aren’t more US women using an IUD?

A general fear of the IUD persists. Women may not even know why they fear the device; they may have simply heard that it is “bad for you.” The negative press the IUD has received in this country probably is related to poor outcomes associated with use of the Dalkon Shield IUD in the 1970s. As a reminder, the Dalkon Shield was blamed for many cases of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and other negative sequelae as a result of poor patient selection. In addition, some authorities believe the design of the device was severely flawed, with a string that permitted bacteria to get from the vagina to the uterus and tubes.

Today, clinicians and many patients are better educated about the prevention of chlamydia, the primary causative organism of PID and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs); patients also are better informed about safe sex practices. We now know that women should be screened for behaviors that could increase their risk for PID and render them poor candidates for the IUD.

Clinicians also have expressed concerns about reimbursement issues related to the IUD, as well as confusion and difficulty with insertion procedures and the potential for litigation. In this article, I address some of these issues in an attempt to increase the use of this highly effective contraceptive.

What’s available today

Today there are three IUDs available to US women (FIGURE):

The Copper IUD (ParaGard)—This device can be used for at least 10 years, although, in many countries, it is considered “permanent reversible contraception.” It has the advantage of being nonhormonal, making it an important option for women who cannot or will not use a hormonal contraceptive. Pregnancy is prevented through a “foreign body” effect and the spermicidal action of copper ions. The combination of these two influences prevents fertilization.4

The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) (Mirena)—This IUD is recommended for 5 years of use but may remain effective for as long as 7 years. It contains 52 mg of levonorgestrel, which it releases at a rate of approximately 20 μg/day. In addition to the foreign body effect, this IUD prevents pregnancy through progestogenic mechanisms: It thickens cervical mucus, thins the endometrium, and reduces sperm capacitation.5

The "mini" LNG-IUS (Skyla)—This newly marketed IUD is recommended for 3 years of use. It contains 13.5 mg of levonorgestrel, which it releases at a rate of 14 μg/day. It has the same mechanism of action as Mirena but may be easier to insert owing to its slightly smaller size and preloaded inserter.

Myth #1: The IUD is not suitable for teens and nulliparous women

This myth arose out of concerns about the smaller uterine cavity and cervical diameter of teens and nulliparous women. Today we know that an IUD can be inserted safely in this population. Moreover, because adolescents are at high risk for unintended pregnancy, they stand to benefit uniquely from LARC options, including the IUD. As the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends in a recent Committee Opinion on adolescents and LARCs, the IUD should be a “first-line” option for all women of reproductive age.6

Myth #2: An IUD should not be inserted immediately after childbirth

For many years, it was assumed that an IUD should be inserted in the postpartum period only after uterine involution was completed. However, in 2010, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, which included the following recommendations for breastfeeding or non–breast-feeding women:

• Mirena was given a Level 2 recommendation (advantages outweigh risks) for insertion within 10 minutes after delivery of the placenta

• The copper IUD was given a Level 1 recommendation (no restrictions) for insertion within the same time interval

• From 10 minutes to 4 weeks postpartum, both devices have a Level 2 recommendation for insertion

• Beyond 4 weeks, both devices have a Level 1 recommendation for insertion.7

Immediate post-delivery insertion of an IUD has several benefits, including:

• a reduction in the risk of unintended pregnancy in women who are not breastfeeding

• providing new mothers with a LARC method.

Myth #3: Antibiotics and NSAIDs should be administered

This myth arose from concerns about PID and insertion-related pain. However, a Cochrane Database review found no benefit for prophylactic use of antibiotics prior to insertion of the copper or LNG-IUS devices to prevent PID.8

In fact, data indicate that the incidence of PID is low among women who are appropriate candidates for an IUD. Similarly, Allen and colleagues found that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) did not ameliorate symptoms of cramping during or immediately after insertion of an IUD.9

Myth #4: IUD insertion is difficult

In reality, both the copper IUD and Mirena are easy to insert. In addition, the smaller LNG-IUS (Skyla) comes more completely preloaded in its inserter. In a published Phase 2 trial comparing Mirena with two smaller, lower-dose levonorgestrel-releasing devices, with the lowest-dose product corresponding to the marketed Skyla product, all 738 women given Mirena or the smaller devices experienced successful placement, with 98.5% of placements achieved on the first attempt.10

Various studies have been conducted to evaluate methods to ease insertion, including use of intracervical lidocaine, vaginal and/or oral administration of misoprostol (Cytotec), and vaginal estrogen creams. None was found to be effective in controlled trials. (See the sidebar, “Data-driven tactics for reducing pain on IUD insertion,” by Jennifer Gunter, MD, on page 28.) In the small percentage of women in whom it is difficult to pass a uterine sound through the external and internal os, cervical dilators may be beneficial. Gentle, progressive dilation can be accomplished easily with minimal discomfort to the patient, easing IUD insertion dramatically.

If a clinician does not insert IUDs on a frequent basis, it is prudent to look over the insertion procedure prior to the patient’s arrival. The procedure then can be reviewed with the patient as part of informed consent, which should be documented in the chart.

No steps in the recommended insertion procedure should be omitted, and charting should reflect each step:

1. Perform a bimanual exam

2. Document the appearance of the vagina and cervix

3. Use betadine or another cleansing solution on the cervical portio

4. Apply the tenaculum to the cervix (anterior lip if the uterus is anteverted, posterior lip if it is retroverted)

5. Sound the uterus to determine the optimal depth of IUD insertion. (The recommended uterine depth is 6 to 10 cm. A smaller uterus increases the likelihood of perforation, pain, and expulsion.)

6. Insert the IUD (and document the ease or difficulty of insertion)

7. Trim the string to an appropriate length

8. Assess the patient’s condition after insertion

9. Schedule a return visit in 4 weeks.

Related Article Let’s increase our use of IUDs and improve contraceptive effectiveness in this country Robert L. Barbieri, MD

Myth #5: Perforation is common

Uterine perforation occurs in approximately 1 in every 1,000 insertions.11 If perforation occurs with a copper IUD, remove the device to prevent the formation of intraperitoneal adhesions.12 The LNG-IUS devices do not produce this reaction, although most experts agree that they should be removed when a perforation occurs.13

Anecdotal evidence suggests that perforation may be more common among breastfeeding women, but this finding is far from definitive.

How to select an IUD for a patient: 3 case studies

CASE 1: Heavy bleeding and signs of endometriosis

Amelia, a 26-year-old nulliparous white woman, visits your office for routine examination and asks about her contraceptive options. She has no notable medical history. She has a body mass index (BMI) of 20.2 kg/m2 and exercises regularly. Menarche occurred at age 13. Her menstrual cycles are regular but are getting heavier; she now “soaks” a tampon every hour. She also complains that her cramps are more difficult to manage. She takes ibuprofen 600 mg every 6 hours during the days of heaviest bleeding and cramping, but that approach doesn’t seem to be effective lately. She is in a stable sexual relationship with her boyfriend of 2 years, now her fiancé. They have been using condoms consistently as contraception but don’t plan to start a family for a “few years.” Amelia reports that their sex life is good, although she has been experiencing pain with deep penetration for about 6 months.

Examination reveals a clear cervix and nontender uterus, although the uterus is retroverted. Palpation of the ovaries indicates that they are normal. Her main complaints: dysmenorrhea and heavy menstrual bleeding.

What contraceptive would you suggest?

Amelia would be a good candidate for the LNG-IUS because she is in a stable relationship and wants to postpone pregnancy for several years. Although she has some symptoms suggestive of endometriosis (dyspareunia), they could be relieved by this method.14 Because thinning of the endometrial lining is an inherent mechanism of action of the LNG-IUS, this method could reduce her heavy bleeding.

She should be advised of the risks and benefits of the LNG-IUS, which can be inserted when she begins her next menstrual cycle.

CASE 2: Mother of two with no immediate desire for pregnancy

Tamika is a 19-year-old black woman (G2P2) who has arrived at your clinic for her 6-week postpartum visit. She is not breastfeeding. Her BMI is 25.7 kg/m2. She reports that her baby and 2-year-old are doing “OK” and says she does not want to get pregnant again anytime soon. She is in a relationship with the father of her baby and says he is “working a good job and taking care of me.” Her menstrual cycles have always been normal, with no cramping or heavy bleeding.

Examination reveals that her cervix is clear, her uterus is anteverted and nontender, and her ovaries appear to be normal.

Would this patient be a good candidate for a LARC?

Tamika is an excellent candidate for the copper IUD or LNG-IUS and should be educated about both methods. If she chooses an IUD, it can be inserted at the start of her next menstrual period.

These first two cases illustrate the importance of making no assumptions on the basis of general patient characteristics. Although Tamika may appear to be at greater risk for STI than Amelia, such “typecasting” may lead to inappropriate counseling.

Related Article Malpositioned IUDs: When you should intervene (and when you should not)

At the time of IUD insertion, both patients should be instructed to check for the IUD string periodically, and this recommendation should be documented in their charts.

CASE 3: Anovulatory patient with heavy periods

Mary, 25, is a nulliparous Hispanic woman who has been referred by her primary care provider. She has a BMI of 35.4 kg/m2 and has had menstrual problems since menarche at the age of 14. She reports that her periods are irregular and very heavy, with intermittent pelvic pain that she manages, with some success, with ibuprofen. She has never had a sexual relationship, but she has a boyfriend now and asks about her contraceptive options.

On examination, you discover that Mary has pubic hair distribution over her inner thigh, with primary escutcheon and acanthosis nigricans on the inner thigh. Her vulva is marked by multiple sebaceous cysts, and a speculum exam shows a large amount of estrogenic mucus and a clear cervix. Her uterus is anteverted and nontender. Her ovaries are palpable but may be enlarged, and transvaginal ultrasound reveals that they are cystic. Her diagnosis: hirsutism with probable polycystic ovary syndrome.

Would an IUD be appropriate?

Mary is not a good candidate for an IUD. Neither the copper IUD nor the LNG-IUS would suppress ovarian function sufficiently to reduce the growth of multiple follicles that occurs with polycystic ovary syndrome. She would benefit from a hormonal method (specifically, a combination oral contraceptive) to suppress follicular activity.

Time for a renaissance?

The IUD may be making a comeback. With the unintended pregnancy rate remaining consistently at about 50%, it is important that we offer our patients contraceptive methods that maximize efficacy, safety, and convenience. Today’s IUDs meet all these criteria.

Data-driven tactics for reducing pain on IUD insertion

Many patients worry about the potential for pain with IUD insertion—and this concern can dissuade them from choosing the IUD as a contraceptive. This is regrettable because the IUD has the highest satisfaction rating among reversible contraceptives, as well as the greatest efficacy.

How much pain can your patient expect? In one recent prospective study involving 40 women who received either 1.2% lidocaine or saline infused 3 minutes before IUD insertion, 33% of women reported a pain score of 5 or higher (on a scale of 0–10) at tenaculum placement. This finding means that two-thirds of women had a pain score of 4 or lower. In fact, 46% of women had a pain score of 2 or below.15 (The mean pain scores for insertion were similar with lidocaine and placebo [3.0 vs 3.7, respectively; P=.4]).

Pain reducing options

The evidence validates (or fails to disprove) the value of the following interventions to make insertion more comfortable for patients:

• Naproxen (550 mg) administration 40 minutes prior to insertion. One small study found it to be better than placebo.9

• Nonopioid pain medication. One small, randomized, double-blinded clinical trial found that tramadol was even more effective than naproxen at relieving insertion-related pain.16

• Injection of lidocaine into the cervix. Although this intervention is common, data supporting it are scarce. One small, high-quality study found no benefit, compared with placebo. However, if you have had success with this approach in the past, I would not discourage you from continuing to offer it, as a single small study is insufficient to disprove it.15 More data are needed.

• Keeping the patient calm. Anxiety increases the perception of pain. Studies have demonstrated that women who expect pain at insertion are more likely to experience it. Encourage the patient to breathe diaphragmatically, and remind her that she is likely to be very happy with her choice of the IUD.

Many other interventions don’t seem to be effective, although they may be offered frequently. Unproven methods include administration of NSAIDs other than naproxen, use of misoprostol (which can increase cramping), application of topical lidocaine to the cervix, and insertion during menses (although the LNG-IUS is inserted during the menstrual period to render it effective during the first month of use).

The studies described here come from the general population of reproductive-age women. If a patient has cervical scarring or a history of difficult or painful insertion, she may be more likely to experience pain, and these data may not apply to her.

—Jennifer Gunter, MD

Dr. Gunter is an ObGyn in San Francisco. She is the author of The Preemie Primer: A Complete Guide for Parents of Premature Babies—from Birth through the Toddler Years and Beyond (Da Capo Press, 2010). Dr. Gunter blogs at www.drjengunter.com, and you can find her on Twitter at @DrJenGunter. She is an OBG Management Contributing Editor.

Dr. Gunter reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

1. 2006 Pan EU study on female contraceptives [unpublished data]. Bayer Schering Pharma; 2007.

2. Moser WD, Martinex GM, Chandra A, Abma JC, Wilson SJ. Use of contraception and use of family planning services in the United States: 1982–2002. Advance data from vital and health statistics; No. 350. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics. 2004;350:1–36.

3. Finer LB, Jerman J, Kavanaugh ML. Changes in use of long-acting contraceptive methods in the United States, 2007–2009. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(4):893–897.

4. Ortiz ME, Croxatto HB, Bardin CW. Mechanisms of action of intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1996;51(12 Suppl):S42–S51.

5. Barbosa I, Olsson SE, Odlind V, Goncalves T, Coutinho E. Ovarian function after seven years’ use of a levonorgestrel IUD. Adv Contracept. 1995;11(2):85–95.

6. Committee on Adolescent Health Care Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion #539: Adolescents and long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(4):983–988.

7. CDC. US medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2010. MMWR Early Release. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr59e0528.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2013.

8. Grimes DA, Lopez LM, Schulz KF. Antibiotics for prevention with IUDs. Cochrane summaries. http://summaries.cochrane.org/CD001327/antibiotics-for-prevention-with-iuds. Published May 16, 2012. Accessed August 18, 2013.

9. Allen RH, Bartz D, Grimes DA, Hubacher D, O’Brien P. Interventions for pain with intrauterine device insertion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009; (3):CD007373.

10. Gemzell-Danielsson K, Schellschmidt I, Apter D. A randomized phase II study describing the efficacy, bleeding profile, and safety of two low-dose levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive systems and Mirena. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(3):616-622.e1-e3.

11. Grimes DA. Intrauterine devices (IUDs). In: Hatcher RA, ed. Contraceptive Technology. 19th ed. New York, New York: Ardent Media; 2007:117–143.

12. Hatcher RA. Contraceptive Technology. New York, New York: Ardent Media; 2011.

13. Adoni A, Ben C. The management of intrauterine devices following uterine perforation. Contraception. 1991;43(1):77.

14. Petta CA, Ferriani RA, Abrao MS, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and a depot GnRH analogue for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(7):1993–1998.

15. Nelson AL, Fong JK. Intrauterine infusion of lidocaine does not reduce pain scores during IUD insertion. Contraception. 2013;88(1):37–40.

16. Karabayirli S, Ayrim AA, Muslu B. Comparison of the analgesic effects of oral tramadol and naproxen sodium on pain relief during IUD insertion. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19(5):581–584.

1. 2006 Pan EU study on female contraceptives [unpublished data]. Bayer Schering Pharma; 2007.

2. Moser WD, Martinex GM, Chandra A, Abma JC, Wilson SJ. Use of contraception and use of family planning services in the United States: 1982–2002. Advance data from vital and health statistics; No. 350. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics. 2004;350:1–36.

3. Finer LB, Jerman J, Kavanaugh ML. Changes in use of long-acting contraceptive methods in the United States, 2007–2009. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(4):893–897.

4. Ortiz ME, Croxatto HB, Bardin CW. Mechanisms of action of intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1996;51(12 Suppl):S42–S51.

5. Barbosa I, Olsson SE, Odlind V, Goncalves T, Coutinho E. Ovarian function after seven years’ use of a levonorgestrel IUD. Adv Contracept. 1995;11(2):85–95.

6. Committee on Adolescent Health Care Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion #539: Adolescents and long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(4):983–988.

7. CDC. US medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2010. MMWR Early Release. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr59e0528.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2013.

8. Grimes DA, Lopez LM, Schulz KF. Antibiotics for prevention with IUDs. Cochrane summaries. http://summaries.cochrane.org/CD001327/antibiotics-for-prevention-with-iuds. Published May 16, 2012. Accessed August 18, 2013.

9. Allen RH, Bartz D, Grimes DA, Hubacher D, O’Brien P. Interventions for pain with intrauterine device insertion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009; (3):CD007373.

10. Gemzell-Danielsson K, Schellschmidt I, Apter D. A randomized phase II study describing the efficacy, bleeding profile, and safety of two low-dose levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine contraceptive systems and Mirena. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(3):616-622.e1-e3.

11. Grimes DA. Intrauterine devices (IUDs). In: Hatcher RA, ed. Contraceptive Technology. 19th ed. New York, New York: Ardent Media; 2007:117–143.

12. Hatcher RA. Contraceptive Technology. New York, New York: Ardent Media; 2011.

13. Adoni A, Ben C. The management of intrauterine devices following uterine perforation. Contraception. 1991;43(1):77.

14. Petta CA, Ferriani RA, Abrao MS, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and a depot GnRH analogue for the treatment of chronic pelvic pain in women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(7):1993–1998.

15. Nelson AL, Fong JK. Intrauterine infusion of lidocaine does not reduce pain scores during IUD insertion. Contraception. 2013;88(1):37–40.

16. Karabayirli S, Ayrim AA, Muslu B. Comparison of the analgesic effects of oral tramadol and naproxen sodium on pain relief during IUD insertion. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19(5):581–584.