User login

Conjugated Estrogen Plus Bazedoxifene: A New Approach to Estrogen Therapy

Much of my practice has focused on the treatment of menopausal women, but which of my patients can benefit from this particular combination of conjugated estrogen (CE) 0.45 mg plus bazedoxifene (BZA) 20 mg? I asked Dr Pinkerton this question, and more.

WHICH PATIENTS CAN BENEFIT MOST?

Dr Pinkerton: CE/BZA was tested in healthy postmenopausal women with a uterus who are at risk for bone loss and were reporting 50 or more moderate to severe hot flashes per week. The combination of CE and BZA is a good choice for women who have bothersome menopausal symptoms: hot flashes, night sweats, and sleep disruption or symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA)—although it’s not approved for VVA.

Efficacy and safety data show that compared with placebo

• CE/BZA decreases the frequency and severity of hot flashes at 12 weeks, and those decreases are maintained at 12 months.1,2

• Women taking CE/BZA have greater improvements in sleep, with both decreased sleep disturbance and time to fall asleep.3

• CE/BZA maintained or prevented lumbar spine and hip bone loss in postmenopausal women at risk for osteoporosis.1,4,5

Although fracture data were not captured and the drug was not tested in osteoporotic women, study results showed bone loss prevention at 12 months, which was sustained at 24 months. The improvement in bone mineral density from baseline was about 1% to 1.5%. This was compared with a bone loss of 1.8% in women taking placebo.

In clinical studies, women taking CE/BZA versus placebo also reported a lower incidence of painful intercourse6 and some improvement in health-related quality of life and treatment satisfaction.7,8

In short, CE/BZA is a good option for symptomatic menopausal women with a uterus who have bothersome hot flashes, night sweats, and sleep disruptions and want to prevent bone loss.

WHAT ABOUT ADVERSE EFFECTS?

Dr Pinkerton: In general, CE/BZA has a favorable safety and tolerability profile, with an overall incidence of adverse events similar to placebo. The rates of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, cancers (breast, endometrial, and ovarian), and mortality are comparable to placebo in two-year trials. These data are limited; studies have been conducted in healthy postmenopausal women. Future studies need to define the full risk profile, particularly among overweight or obese women and different ethnic groups, as well as for longer-term use.

IS THERE A ROLE AMONG WOMEN WITH BREAST CANCER?

Dr Pinkerton: CE/BZA has not been tested in women at risk for or who have a history of breast cancer. In preclinical trials of up to two years’ duration, involving healthy postmenopausal women, the rates for breast cancer with CE/BZA were similar to placebo. There are no long-term data, however, and there are no data in women at risk for breast cancer. I recommend that women who have or are at high risk for breast cancer consider nonhormonal treatment options.9–11

HAS THERE BEEN AN ASSOCIATED INCREASE IN BREAST DENSITY WITH CE/BZA?

Dr Pinkerton: No. Data from two randomized clinical trials showed that the breast density changes with 12-month CE/BZA treatment were similar to placebo—which is markedly different from comparisons of placebo and combination estrogen-progestin therapy (EPT), where EPT increased breast density. If indeed this lack of an association translates into fewer breast cancers, it would be wonderful, but we do not have long-term data. We can tell our patients that using CE/BZA has not been shown to increase the risk for breast cancer, at least up to two years.

Continue for differences from traditional EPT >>

WHAT MAKES CE/BZA DIFFERENT FROM TRADITIONAL EPT?

Dr Pinkerton: There are two exciting differences:

• The incidences of breast pain and tenderness were found to be similar to placebo and were significantly lower than those with the comparator EPT (conjugated estrogens 0.45 mg plus medroxyprogesterone acetate [CE/MPA] 1.5 mg).9,10,12

• Bleeding and spotting rates were significantly lower than those found with CE/MPA.13

In addition, high rates of amenorrhea have been found—comparable to placebo.13

CE/BZA is similar to traditional EPT in several ways. For instance, compared with placebo, at two years, CE/BZA was not found to increase the incidence of endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial thickness (increase from baseline was < 1 mm and comparable to placebo), or endometrial cancers.14 Lastly, similar to EPT, there is probably a twofold risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE) with BZA 20 mg alone.15 Importantly, there has been no additive effect on VTE risk when combining CE with BZA; however, we will need longer studies, in older women, to fully evaluate this risk.1

Overall, in symptomatic postmenopausal women with a uterus, randomized controlled data show the same improvement with CE/BZA as that seen with traditional oral EPTs, with improvements in hot flashes; night sweats, with fewer sleep disruptions; and prevention of bone loss. In addition, the changes in cholesterol (an increase in triglyceride levels) and effect on the vagina are the same. Yet, CE/BZA appears to have a neutral effect on the breast and protects against endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer without causing bleeding.9,10 CE/BZA’s VTE and stroke risks are expected to be similar to traditional oral EPT.

Therefore, the major benefit of CE/BZA for women who have a uterus is the lack of significant breast tenderness, lack of changes in breast density, and lack of vaginal bleeding that is often seen with traditional EPT.12

THEN, IS PROGESTOGEN THE HARMFUL AGENT IN TRADITIONAL HT OPTIONS?

Dr Pinkerton: There is evidence that estrogen plus progestogen therapy has more risk for breast cancer than estrogen alone. But in women who have a uterus, you need to protect against uterine cancer so, up until now, the only option was to add progestogen. Some studies suggest the risk for breast cancer may differ depending on the type of progestogen. So it’s a laudable goal to try to protect the endometrium without using a progestogen.

GIVEN ITS SAFETY PROFILE, DO YOU SEE CE/BZA BEING INDICATED FOR WOMEN WITHOUT A UTERUS?

Dr Pinkerton: CE/BZA has been tested only in women with a uterus; there is no indication for using it in hysterectomized women. In the future, unless trial data show a benefit to hysterectomized women—by a reduction in breast cancer compared with estrogen alone—there would be no reason to add BZA to the CE for these women. You would just use CE or another type of estrogen alone.

DO YOU ANTICIPATE BZA BEING USED ALONE?

Dr Pinkerton: For treating osteoporosis in postmenopausal women at increased risk for fracture, BZA alone has greater benefits than risks. It is approved in other countries to prevent or treat osteoporosis. In 2008, Wyeth received an approval letter from the FDA for BZA alone but, for whatever reason, the drug was not brought to market. BZA reduces the number of new lumbar spine fractures by 4% (vs 2% for placebo), with efficacy better in those with a higher risk for fractures. Like raloxifene, it has not been shown effective at reducing nonvertebral fractures, although it maintains spinal bone density.16

BZA available as monotherapy could tempt clinicians to pair it with other estrogens. We must recognize that the combination of the specific estrogen and BZA dose and type need to be balanced to provide endometrial hyperplasia protection. It would not be safe or effective to take BZA as a selective estrogen-receptor modulator and pair it with any other untested systemic estrogen. I do not anticipate, in this country, that BZA will become available as monotherapy, however.

NEW OPTIONS ARE WELCOME

Dr Moore: Novel strategies for clinicians to optimally treat menopausal symptoms are always welcome. I look forward to more data from the SMART trials on CE/BZA and to moving forward as we gain experience with using this new treatment option.

REFERENCES

1. Lobo RA, Pinkerton JV, Gass ML, et al. Evaluation of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and effects on metabolic bone parameters and overall safety profile. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1025–1038.

2. Pinkerton JV, Utian WH, Constantine GD, et al. Relief of vasomotor symptoms with the tissue-selective estrogen complex containing bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2009;16(6): 1116–1124.

3. Pinkerton JV, Pan K, Abraham L, et al. Sleep parameters and health-related quality of life with bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2014;21(3):252–259.

4. Lindsay R, Gallagher JC, Kagan R, et al. Efficacy of tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC) of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE) for osteoporosis prevention in at-risk postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1045–1052.

5. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Lindsay R, et al; SMART-5 Investigators. Effects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on the endometrium and bone.

J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(2):E189–E198.

6. Kagan R, Williams RS, Pan K, Mirkin S, Pickar JH. A randomized, placebo- and active-controlled trial of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE) for treatment of moderate to severe vulvar/vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2010;17(2):281–289.

7. Utian W, Yu H, Bobula J, et al. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens and quality of life in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2009;63(4):

329–335.

8. Abraham L, Pinkerton JV, Messig M, et al. Menopause-specific quality of life across varying menopausal populations with conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene. Maturitas. 2014;78(3):212–218.

9. Harvey JA, Pinkerton JV, Baracat EC, et al. Breast density changes in a randomized controlled trial evaluating bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2013;20:(2)138–145.

10. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Pan K, et al. Breast effects of bazedoxifene-conjugated estrogens. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(5):959–968.

11. Kaunitz AM. When should a menopausal woman discontinue hormone therapy? OBG Manag. 2014;26(2):59–65.

12. Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH, Racketa J, Mirkin S. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for menopausal symptom treatment and osteoporosis prevention. Climacteric. 2012;15:(5)411–418.

13. Archer DF, Lewis V, Carr BR, et al. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE): incidence of uterine bleeding in postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1039–1044.

14. Pickar JH, Yeh I-T, Bachmann G, Speroff L. Endometrial effects of a tissue selective estrogen complex (TSEC) containing bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens as a menopausal therapy. Fertil Steril. 2009; 92(3):1018–1024.

15. Mirkin S, Komm BS. Tissue-selective estrogen complexes for postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2013;76(3):213–220.

16. Ellis AG, Reginster JY, Luo X, et al. Bazedoxifene versus oral bisphosphonates for the prevention of nonvertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis at higher risk of fracture. Value Health. 2014;17(4):424–432.

Much of my practice has focused on the treatment of menopausal women, but which of my patients can benefit from this particular combination of conjugated estrogen (CE) 0.45 mg plus bazedoxifene (BZA) 20 mg? I asked Dr Pinkerton this question, and more.

WHICH PATIENTS CAN BENEFIT MOST?

Dr Pinkerton: CE/BZA was tested in healthy postmenopausal women with a uterus who are at risk for bone loss and were reporting 50 or more moderate to severe hot flashes per week. The combination of CE and BZA is a good choice for women who have bothersome menopausal symptoms: hot flashes, night sweats, and sleep disruption or symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA)—although it’s not approved for VVA.

Efficacy and safety data show that compared with placebo

• CE/BZA decreases the frequency and severity of hot flashes at 12 weeks, and those decreases are maintained at 12 months.1,2

• Women taking CE/BZA have greater improvements in sleep, with both decreased sleep disturbance and time to fall asleep.3

• CE/BZA maintained or prevented lumbar spine and hip bone loss in postmenopausal women at risk for osteoporosis.1,4,5

Although fracture data were not captured and the drug was not tested in osteoporotic women, study results showed bone loss prevention at 12 months, which was sustained at 24 months. The improvement in bone mineral density from baseline was about 1% to 1.5%. This was compared with a bone loss of 1.8% in women taking placebo.

In clinical studies, women taking CE/BZA versus placebo also reported a lower incidence of painful intercourse6 and some improvement in health-related quality of life and treatment satisfaction.7,8

In short, CE/BZA is a good option for symptomatic menopausal women with a uterus who have bothersome hot flashes, night sweats, and sleep disruptions and want to prevent bone loss.

WHAT ABOUT ADVERSE EFFECTS?

Dr Pinkerton: In general, CE/BZA has a favorable safety and tolerability profile, with an overall incidence of adverse events similar to placebo. The rates of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, cancers (breast, endometrial, and ovarian), and mortality are comparable to placebo in two-year trials. These data are limited; studies have been conducted in healthy postmenopausal women. Future studies need to define the full risk profile, particularly among overweight or obese women and different ethnic groups, as well as for longer-term use.

IS THERE A ROLE AMONG WOMEN WITH BREAST CANCER?

Dr Pinkerton: CE/BZA has not been tested in women at risk for or who have a history of breast cancer. In preclinical trials of up to two years’ duration, involving healthy postmenopausal women, the rates for breast cancer with CE/BZA were similar to placebo. There are no long-term data, however, and there are no data in women at risk for breast cancer. I recommend that women who have or are at high risk for breast cancer consider nonhormonal treatment options.9–11

HAS THERE BEEN AN ASSOCIATED INCREASE IN BREAST DENSITY WITH CE/BZA?

Dr Pinkerton: No. Data from two randomized clinical trials showed that the breast density changes with 12-month CE/BZA treatment were similar to placebo—which is markedly different from comparisons of placebo and combination estrogen-progestin therapy (EPT), where EPT increased breast density. If indeed this lack of an association translates into fewer breast cancers, it would be wonderful, but we do not have long-term data. We can tell our patients that using CE/BZA has not been shown to increase the risk for breast cancer, at least up to two years.

Continue for differences from traditional EPT >>

WHAT MAKES CE/BZA DIFFERENT FROM TRADITIONAL EPT?

Dr Pinkerton: There are two exciting differences:

• The incidences of breast pain and tenderness were found to be similar to placebo and were significantly lower than those with the comparator EPT (conjugated estrogens 0.45 mg plus medroxyprogesterone acetate [CE/MPA] 1.5 mg).9,10,12

• Bleeding and spotting rates were significantly lower than those found with CE/MPA.13

In addition, high rates of amenorrhea have been found—comparable to placebo.13

CE/BZA is similar to traditional EPT in several ways. For instance, compared with placebo, at two years, CE/BZA was not found to increase the incidence of endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial thickness (increase from baseline was < 1 mm and comparable to placebo), or endometrial cancers.14 Lastly, similar to EPT, there is probably a twofold risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE) with BZA 20 mg alone.15 Importantly, there has been no additive effect on VTE risk when combining CE with BZA; however, we will need longer studies, in older women, to fully evaluate this risk.1

Overall, in symptomatic postmenopausal women with a uterus, randomized controlled data show the same improvement with CE/BZA as that seen with traditional oral EPTs, with improvements in hot flashes; night sweats, with fewer sleep disruptions; and prevention of bone loss. In addition, the changes in cholesterol (an increase in triglyceride levels) and effect on the vagina are the same. Yet, CE/BZA appears to have a neutral effect on the breast and protects against endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer without causing bleeding.9,10 CE/BZA’s VTE and stroke risks are expected to be similar to traditional oral EPT.

Therefore, the major benefit of CE/BZA for women who have a uterus is the lack of significant breast tenderness, lack of changes in breast density, and lack of vaginal bleeding that is often seen with traditional EPT.12

THEN, IS PROGESTOGEN THE HARMFUL AGENT IN TRADITIONAL HT OPTIONS?

Dr Pinkerton: There is evidence that estrogen plus progestogen therapy has more risk for breast cancer than estrogen alone. But in women who have a uterus, you need to protect against uterine cancer so, up until now, the only option was to add progestogen. Some studies suggest the risk for breast cancer may differ depending on the type of progestogen. So it’s a laudable goal to try to protect the endometrium without using a progestogen.

GIVEN ITS SAFETY PROFILE, DO YOU SEE CE/BZA BEING INDICATED FOR WOMEN WITHOUT A UTERUS?

Dr Pinkerton: CE/BZA has been tested only in women with a uterus; there is no indication for using it in hysterectomized women. In the future, unless trial data show a benefit to hysterectomized women—by a reduction in breast cancer compared with estrogen alone—there would be no reason to add BZA to the CE for these women. You would just use CE or another type of estrogen alone.

DO YOU ANTICIPATE BZA BEING USED ALONE?

Dr Pinkerton: For treating osteoporosis in postmenopausal women at increased risk for fracture, BZA alone has greater benefits than risks. It is approved in other countries to prevent or treat osteoporosis. In 2008, Wyeth received an approval letter from the FDA for BZA alone but, for whatever reason, the drug was not brought to market. BZA reduces the number of new lumbar spine fractures by 4% (vs 2% for placebo), with efficacy better in those with a higher risk for fractures. Like raloxifene, it has not been shown effective at reducing nonvertebral fractures, although it maintains spinal bone density.16

BZA available as monotherapy could tempt clinicians to pair it with other estrogens. We must recognize that the combination of the specific estrogen and BZA dose and type need to be balanced to provide endometrial hyperplasia protection. It would not be safe or effective to take BZA as a selective estrogen-receptor modulator and pair it with any other untested systemic estrogen. I do not anticipate, in this country, that BZA will become available as monotherapy, however.

NEW OPTIONS ARE WELCOME

Dr Moore: Novel strategies for clinicians to optimally treat menopausal symptoms are always welcome. I look forward to more data from the SMART trials on CE/BZA and to moving forward as we gain experience with using this new treatment option.

REFERENCES

1. Lobo RA, Pinkerton JV, Gass ML, et al. Evaluation of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and effects on metabolic bone parameters and overall safety profile. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1025–1038.

2. Pinkerton JV, Utian WH, Constantine GD, et al. Relief of vasomotor symptoms with the tissue-selective estrogen complex containing bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2009;16(6): 1116–1124.

3. Pinkerton JV, Pan K, Abraham L, et al. Sleep parameters and health-related quality of life with bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2014;21(3):252–259.

4. Lindsay R, Gallagher JC, Kagan R, et al. Efficacy of tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC) of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE) for osteoporosis prevention in at-risk postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1045–1052.

5. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Lindsay R, et al; SMART-5 Investigators. Effects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on the endometrium and bone.

J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(2):E189–E198.

6. Kagan R, Williams RS, Pan K, Mirkin S, Pickar JH. A randomized, placebo- and active-controlled trial of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE) for treatment of moderate to severe vulvar/vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2010;17(2):281–289.

7. Utian W, Yu H, Bobula J, et al. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens and quality of life in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2009;63(4):

329–335.

8. Abraham L, Pinkerton JV, Messig M, et al. Menopause-specific quality of life across varying menopausal populations with conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene. Maturitas. 2014;78(3):212–218.

9. Harvey JA, Pinkerton JV, Baracat EC, et al. Breast density changes in a randomized controlled trial evaluating bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2013;20:(2)138–145.

10. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Pan K, et al. Breast effects of bazedoxifene-conjugated estrogens. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(5):959–968.

11. Kaunitz AM. When should a menopausal woman discontinue hormone therapy? OBG Manag. 2014;26(2):59–65.

12. Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH, Racketa J, Mirkin S. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for menopausal symptom treatment and osteoporosis prevention. Climacteric. 2012;15:(5)411–418.

13. Archer DF, Lewis V, Carr BR, et al. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE): incidence of uterine bleeding in postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1039–1044.

14. Pickar JH, Yeh I-T, Bachmann G, Speroff L. Endometrial effects of a tissue selective estrogen complex (TSEC) containing bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens as a menopausal therapy. Fertil Steril. 2009; 92(3):1018–1024.

15. Mirkin S, Komm BS. Tissue-selective estrogen complexes for postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2013;76(3):213–220.

16. Ellis AG, Reginster JY, Luo X, et al. Bazedoxifene versus oral bisphosphonates for the prevention of nonvertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis at higher risk of fracture. Value Health. 2014;17(4):424–432.

Much of my practice has focused on the treatment of menopausal women, but which of my patients can benefit from this particular combination of conjugated estrogen (CE) 0.45 mg plus bazedoxifene (BZA) 20 mg? I asked Dr Pinkerton this question, and more.

WHICH PATIENTS CAN BENEFIT MOST?

Dr Pinkerton: CE/BZA was tested in healthy postmenopausal women with a uterus who are at risk for bone loss and were reporting 50 or more moderate to severe hot flashes per week. The combination of CE and BZA is a good choice for women who have bothersome menopausal symptoms: hot flashes, night sweats, and sleep disruption or symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA)—although it’s not approved for VVA.

Efficacy and safety data show that compared with placebo

• CE/BZA decreases the frequency and severity of hot flashes at 12 weeks, and those decreases are maintained at 12 months.1,2

• Women taking CE/BZA have greater improvements in sleep, with both decreased sleep disturbance and time to fall asleep.3

• CE/BZA maintained or prevented lumbar spine and hip bone loss in postmenopausal women at risk for osteoporosis.1,4,5

Although fracture data were not captured and the drug was not tested in osteoporotic women, study results showed bone loss prevention at 12 months, which was sustained at 24 months. The improvement in bone mineral density from baseline was about 1% to 1.5%. This was compared with a bone loss of 1.8% in women taking placebo.

In clinical studies, women taking CE/BZA versus placebo also reported a lower incidence of painful intercourse6 and some improvement in health-related quality of life and treatment satisfaction.7,8

In short, CE/BZA is a good option for symptomatic menopausal women with a uterus who have bothersome hot flashes, night sweats, and sleep disruptions and want to prevent bone loss.

WHAT ABOUT ADVERSE EFFECTS?

Dr Pinkerton: In general, CE/BZA has a favorable safety and tolerability profile, with an overall incidence of adverse events similar to placebo. The rates of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, cancers (breast, endometrial, and ovarian), and mortality are comparable to placebo in two-year trials. These data are limited; studies have been conducted in healthy postmenopausal women. Future studies need to define the full risk profile, particularly among overweight or obese women and different ethnic groups, as well as for longer-term use.

IS THERE A ROLE AMONG WOMEN WITH BREAST CANCER?

Dr Pinkerton: CE/BZA has not been tested in women at risk for or who have a history of breast cancer. In preclinical trials of up to two years’ duration, involving healthy postmenopausal women, the rates for breast cancer with CE/BZA were similar to placebo. There are no long-term data, however, and there are no data in women at risk for breast cancer. I recommend that women who have or are at high risk for breast cancer consider nonhormonal treatment options.9–11

HAS THERE BEEN AN ASSOCIATED INCREASE IN BREAST DENSITY WITH CE/BZA?

Dr Pinkerton: No. Data from two randomized clinical trials showed that the breast density changes with 12-month CE/BZA treatment were similar to placebo—which is markedly different from comparisons of placebo and combination estrogen-progestin therapy (EPT), where EPT increased breast density. If indeed this lack of an association translates into fewer breast cancers, it would be wonderful, but we do not have long-term data. We can tell our patients that using CE/BZA has not been shown to increase the risk for breast cancer, at least up to two years.

Continue for differences from traditional EPT >>

WHAT MAKES CE/BZA DIFFERENT FROM TRADITIONAL EPT?

Dr Pinkerton: There are two exciting differences:

• The incidences of breast pain and tenderness were found to be similar to placebo and were significantly lower than those with the comparator EPT (conjugated estrogens 0.45 mg plus medroxyprogesterone acetate [CE/MPA] 1.5 mg).9,10,12

• Bleeding and spotting rates were significantly lower than those found with CE/MPA.13

In addition, high rates of amenorrhea have been found—comparable to placebo.13

CE/BZA is similar to traditional EPT in several ways. For instance, compared with placebo, at two years, CE/BZA was not found to increase the incidence of endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial thickness (increase from baseline was < 1 mm and comparable to placebo), or endometrial cancers.14 Lastly, similar to EPT, there is probably a twofold risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE) with BZA 20 mg alone.15 Importantly, there has been no additive effect on VTE risk when combining CE with BZA; however, we will need longer studies, in older women, to fully evaluate this risk.1

Overall, in symptomatic postmenopausal women with a uterus, randomized controlled data show the same improvement with CE/BZA as that seen with traditional oral EPTs, with improvements in hot flashes; night sweats, with fewer sleep disruptions; and prevention of bone loss. In addition, the changes in cholesterol (an increase in triglyceride levels) and effect on the vagina are the same. Yet, CE/BZA appears to have a neutral effect on the breast and protects against endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer without causing bleeding.9,10 CE/BZA’s VTE and stroke risks are expected to be similar to traditional oral EPT.

Therefore, the major benefit of CE/BZA for women who have a uterus is the lack of significant breast tenderness, lack of changes in breast density, and lack of vaginal bleeding that is often seen with traditional EPT.12

THEN, IS PROGESTOGEN THE HARMFUL AGENT IN TRADITIONAL HT OPTIONS?

Dr Pinkerton: There is evidence that estrogen plus progestogen therapy has more risk for breast cancer than estrogen alone. But in women who have a uterus, you need to protect against uterine cancer so, up until now, the only option was to add progestogen. Some studies suggest the risk for breast cancer may differ depending on the type of progestogen. So it’s a laudable goal to try to protect the endometrium without using a progestogen.

GIVEN ITS SAFETY PROFILE, DO YOU SEE CE/BZA BEING INDICATED FOR WOMEN WITHOUT A UTERUS?

Dr Pinkerton: CE/BZA has been tested only in women with a uterus; there is no indication for using it in hysterectomized women. In the future, unless trial data show a benefit to hysterectomized women—by a reduction in breast cancer compared with estrogen alone—there would be no reason to add BZA to the CE for these women. You would just use CE or another type of estrogen alone.

DO YOU ANTICIPATE BZA BEING USED ALONE?

Dr Pinkerton: For treating osteoporosis in postmenopausal women at increased risk for fracture, BZA alone has greater benefits than risks. It is approved in other countries to prevent or treat osteoporosis. In 2008, Wyeth received an approval letter from the FDA for BZA alone but, for whatever reason, the drug was not brought to market. BZA reduces the number of new lumbar spine fractures by 4% (vs 2% for placebo), with efficacy better in those with a higher risk for fractures. Like raloxifene, it has not been shown effective at reducing nonvertebral fractures, although it maintains spinal bone density.16

BZA available as monotherapy could tempt clinicians to pair it with other estrogens. We must recognize that the combination of the specific estrogen and BZA dose and type need to be balanced to provide endometrial hyperplasia protection. It would not be safe or effective to take BZA as a selective estrogen-receptor modulator and pair it with any other untested systemic estrogen. I do not anticipate, in this country, that BZA will become available as monotherapy, however.

NEW OPTIONS ARE WELCOME

Dr Moore: Novel strategies for clinicians to optimally treat menopausal symptoms are always welcome. I look forward to more data from the SMART trials on CE/BZA and to moving forward as we gain experience with using this new treatment option.

REFERENCES

1. Lobo RA, Pinkerton JV, Gass ML, et al. Evaluation of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and effects on metabolic bone parameters and overall safety profile. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1025–1038.

2. Pinkerton JV, Utian WH, Constantine GD, et al. Relief of vasomotor symptoms with the tissue-selective estrogen complex containing bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2009;16(6): 1116–1124.

3. Pinkerton JV, Pan K, Abraham L, et al. Sleep parameters and health-related quality of life with bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2014;21(3):252–259.

4. Lindsay R, Gallagher JC, Kagan R, et al. Efficacy of tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC) of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE) for osteoporosis prevention in at-risk postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1045–1052.

5. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Lindsay R, et al; SMART-5 Investigators. Effects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on the endometrium and bone.

J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(2):E189–E198.

6. Kagan R, Williams RS, Pan K, Mirkin S, Pickar JH. A randomized, placebo- and active-controlled trial of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE) for treatment of moderate to severe vulvar/vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2010;17(2):281–289.

7. Utian W, Yu H, Bobula J, et al. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens and quality of life in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2009;63(4):

329–335.

8. Abraham L, Pinkerton JV, Messig M, et al. Menopause-specific quality of life across varying menopausal populations with conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene. Maturitas. 2014;78(3):212–218.

9. Harvey JA, Pinkerton JV, Baracat EC, et al. Breast density changes in a randomized controlled trial evaluating bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2013;20:(2)138–145.

10. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Pan K, et al. Breast effects of bazedoxifene-conjugated estrogens. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(5):959–968.

11. Kaunitz AM. When should a menopausal woman discontinue hormone therapy? OBG Manag. 2014;26(2):59–65.

12. Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH, Racketa J, Mirkin S. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for menopausal symptom treatment and osteoporosis prevention. Climacteric. 2012;15:(5)411–418.

13. Archer DF, Lewis V, Carr BR, et al. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE): incidence of uterine bleeding in postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1039–1044.

14. Pickar JH, Yeh I-T, Bachmann G, Speroff L. Endometrial effects of a tissue selective estrogen complex (TSEC) containing bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens as a menopausal therapy. Fertil Steril. 2009; 92(3):1018–1024.

15. Mirkin S, Komm BS. Tissue-selective estrogen complexes for postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2013;76(3):213–220.

16. Ellis AG, Reginster JY, Luo X, et al. Bazedoxifene versus oral bisphosphonates for the prevention of nonvertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis at higher risk of fracture. Value Health. 2014;17(4):424–432.

Conjugated estrogen plus bazedoxifene—a new approach to estrogen therapy

In this special installment of Cases in Menopause, I interview series contributor and menopause expert JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD. We discuss a fairly new therapy: the combination conjugated estrogen and bazedoxifene (CE/BZA; Duavee) for the treatment of moderate to severe hot flashes due to menopause and the prevention of menopausal osteoporosis.

Much of my practice has focused on the treatment of menopausal women, but which of my patients can benefit from this particular combination of CE 0.45 mg plus BZA 20 mg? I asked Dr. Pinkerton this question, and more.

Which patients can benefit most?

Dr. Pinkerton CE/BZA was tested in healthy postmenopausal women with a uterus at risk for bone loss who were reporting 50 or more moderate to severe hot flashes per week. The combination of CE and BZA is a good choice for women who have bothersome menopausal symptoms: hot flashes, night sweats, and sleep disruption or symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA)—although it’s not approved for VVA.

Efficacy and safety data show that compared with placebo:

- CE/BZA decreases the frequency and severity of hot flashes at 12 weeks, and those decreases are maintained at 12 months.1,2

- Women taking CE/BZA have greater improvements in sleep, with both decreased sleep disturbance and time to fall asleep.3

- CE/BZA maintained or prevented lumbar spine and hip bone loss in postmenopausal women at risk for osteoporosis. 1,4,5

Although fracture data were not captured and the drug was not tested in osteoporotic women, study results showed bone loss prevention at 12 months, which was sustained at 24 months. The improvement in bone mineral density from baseline was about 1% to 1.5%. This was compared with a bone loss of 1.8% in women taking placebo (P<.01).

In clinical studies, women taking CE/BZA versus placebo also have reported a lower incidence of painful intercourse,6 and some improvement in health-related quality of life and treatment satisfaction.7,8

In short, CE/BZA is a good option for symptomatic menopausal women with a uterus who have bothersome hot flashes, night sweats, and sleep disruptions and want to prevent bone loss.

What about adverse effects?

Dr. Pinkerton In general, CE/BZA has a favorable safety and tolerability profile, with an overall incidence of adverse events similar to placebo. The rates of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, cancers (breast, endometrial, and ovarian), and mortality are comparable to placebo in 2-year trials. These data are limited; studies have been conducted in healthy postmenopausal women. Future studies need to define the full risk profile, particularly among overweight or obese women and different ethnic groups and for longer-term use.

Is there a role among women with breast cancer?

Dr. Pinkerton CE/BZA has not been tested in women at risk for or with prior breast cancer. In preclinical trials of up to 2 years, involving healthy postmenopausal women, the rates for breast cancer with CE/BZA were similar to placebo. There are no long-term data, however, and there are no data in women at risk for breast cancer. I recommend that women who have or are at high risk for breast cancer consider nonhormonal treatment options.9–11

Has there been an associated increase in breast density with CE/BZA?

Dr. Pinkerton No. Data from two randomized clinical trials showed that the breast density changes with 12-month CE/BZA treatment was similar to placebo—which is markedly different from comparisons of placebo and combination estrogen-progestin therapy (EPT), where EPT increased breast density. If indeed this lack of an association translates into fewer breast cancers, it would be wonderful, but we do not have long-term data. We can tell our patients that using CE/BZA has not been shown to increase the risk of breast cancer, at least up to 2 years.

What makes CE/BZA different from traditional EPT?

Dr. Pinkerton There are two exciting differences:

- The incidences of breast pain and tenderness were found to be similar to placebo, and were significantly less than those with the comparator EPT (conjugated estrogens 0.45 mg plus medroxyprogesterone acetate [CE/MPA] 1.5 mg).9,10,12

- Bleeding and spotting rates were significantly less than those found with CE/MPA.13

In addition, high rates of amenorrhea have been found—comparable to placebo.13

CE/BZA is similar to traditional EPT in several ways. For instance, compared with placebo, at 2 years, CE/BZA was not found to increase the incidence of endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial thickness (increase from baseline was <1 mm and comparable to placebo), or endometrial cancers.14 Lastly, similar to EPT, there is probably a twofold risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) with BZA 20 mg alone.15 Importantly, there has been no additive effect on VTE risk when combining CE with BZA; however, we will need longer studies, in older women, to fully evaluate this risk.1

Overall, in symptomatic postmenopausal women with a uterus, randomized controlled data show the same improvement with CE/BZA as that seen with traditional oral EPTs, with improvements in hot flashes; night sweats, with fewer sleep disruptions; and prevention of bone loss. In addition, the changes in cholesterol (an increase in triglyceride levels) and effect on the vagina are the same. Yet, CE/BZA appears to have a neutral effect on the breast and protects against endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer without causing bleeding.9,10 CE/BZA’s VTE and stroke risks are expected to be similar to traditional oral EPT.

Therefore, the major benefit of CE/BZA for women who have a uterus is the lack of significant breast tenderness, lack of changes in breast density, and lack of vaginal bleeding that is often seen with traditional EPT.12

Then, is progestogen the harmful agent in traditional HT options?

Dr. Pinkerton There is evidence that estrogen plus progestogen therapy has more risk for breast cancer than estrogen alone. But in women who have a uterus, you need to protect against uterine cancer so, up until now, the only option was to add progestogen. Some studies suggest the risk of breast cancer may differ depending on the type of progestogen. So it’s a laudable goal to try to protect the endometrium without using a progestogen.

Given its safety profile, do you see CE/BZA being indicated for women without a uterus?

Dr. Pinkerton CE/BZA has been tested only in women with a uterus; there is no indication for using it in hysterectomized women. In the future, unless trial data show a benefit to hysterectomized women—by a reduction in breast cancer compared with estrogen alone—there would be no reason to add BZA to the CE for these women. You would just use CE or another type of estrogen alone.

Do you anticipate BZA being used alone?

Dr. Pinkerton For treating osteoporosis in postmenopausal women at increased fracture risk, BZA alone has greater benefits than risks. It is approved in other countries to prevent or treat osteoporosis. In 2008, Wyeth received an approval letter from the US Food and Drug Administration for BZA alone but, for whatever reason, the drug was not brought to market. BZA reduces the number of new lumbar spine fractures by 4% (vs 2% for placebo), with efficacy better in those with a higher risk of fractures. Like raloxifene, it has not been shown effective at reducing nonvertebral fractures, although it maintains spinal bone density.16

BZA available as monotherapy could tempt clinicians to pair it with other estrogens. We must recognize that the combination of the specific estrogen and BZA dose and type need to be balanced to provide endometrial hyperplasia protection. It would not be safe or effective to take BZA as a selective estrogen-receptor modulator and pair it with any other untested systemic estrogen. I do not anticipate, in this country, that BZA will become available as monotherapy.

New options are welcome

Dr. Moore Novel strategies for clinicians to optimally treat menopausal symptoms are always welcome. I look forward to more data from the SMART trials on CE/BZA and to moving forward as we gain experience with using this new treatment option.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Lobo RA, Pinkerton JV, Gass ML, et al. Evaluation of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and effects on metabolic bone parameters and overall safety profile. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1025–1038.

2. Pinkerton JV, Utian WH, Constantine GD, Olivier S, Pickar JH. Relief of vasomotor symptoms with the tissue-selective estrogen complex containing bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2009;16:(6)1116–1124.

3. Pinkerton JV, Pan K, Abraham L, et al. Sleep parameters and health-related quality of life with bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2014;21(3):252–259.

4. Lindsay R, Gallagher JC, Kagan R, Pickar JH, Constantine G. Efficacy of tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC) of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE) for osteoporosis prevention in at-risk postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1045–1052.

5. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Lindsay R, et al; SMART-5 Investigators. Effects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on the endometrium and bone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(2):E189–E198.

6. Kagan R, Williams RS, Pan K, Mirkin S, Pickar JH. A randomized, placebo- and active-controlled trial of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE) for treatment of moderate to severe vulvar/vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2010;17(2):281–289.

7. Utian W, Yu H, Bobula J, Mirkin S, Olivier S, Pickar JH. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens and quality of life in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2009;63:(4)329–335.

8. Abraham L, Pinkerton JV, Messig M, Ryan KA, Komm BS, Mirkin S. Menopause-specific quality of life across varying menopausal populations with conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene. Maturitas. 2014;78(3):212–218.

9. Harvey JA, Pinkerton JV, Baracat EC, Shi H, Chines AA, Mirkin S. Breast density changes in a randomized controlled trial evaluating bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2013;20:(2)138–145.

10. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Pan K, et al. Breast effects of bazedoxifene-conjugated estrogens. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(5):959–968.

11. Kaunitz AM. When should a menopausal woman discontinue hormone therapy? OBG Manag. 2014;26(2):59–65.

12. Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH, Racketa J, Mirkin S. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for menopausal symptom treatment and osteoporosis prevention. Climacteric. 2012;15:(5)411–418.

13. Archer DF, Lewis V, Carr BR, Olivier S, Pickar JH. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE): incidence of uterine bleeding in postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1039–1044.

14. Pickar JH, Yeh I-T, Bachmann G, Speroff L. Endometrial effects of a tissue selective estrogen complex (TSEC) containing bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens as a menopausal therapy. Fertil Steril. 2009; 92(3):1018–1024.

15. Mirkin S, Komm BS. Tissue-selective estrogen complexes for postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2013;76(3):213–220.

16. Ellis AG, Reginster JY, Luo X, et al. Bazedoxifene versus oral bisphosphonates for the prevention of nonvertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis at higher risk of fracture. Value Health. 2014;17(4):424–432.

In this special installment of Cases in Menopause, I interview series contributor and menopause expert JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD. We discuss a fairly new therapy: the combination conjugated estrogen and bazedoxifene (CE/BZA; Duavee) for the treatment of moderate to severe hot flashes due to menopause and the prevention of menopausal osteoporosis.

Much of my practice has focused on the treatment of menopausal women, but which of my patients can benefit from this particular combination of CE 0.45 mg plus BZA 20 mg? I asked Dr. Pinkerton this question, and more.

Which patients can benefit most?

Dr. Pinkerton CE/BZA was tested in healthy postmenopausal women with a uterus at risk for bone loss who were reporting 50 or more moderate to severe hot flashes per week. The combination of CE and BZA is a good choice for women who have bothersome menopausal symptoms: hot flashes, night sweats, and sleep disruption or symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA)—although it’s not approved for VVA.

Efficacy and safety data show that compared with placebo:

- CE/BZA decreases the frequency and severity of hot flashes at 12 weeks, and those decreases are maintained at 12 months.1,2

- Women taking CE/BZA have greater improvements in sleep, with both decreased sleep disturbance and time to fall asleep.3

- CE/BZA maintained or prevented lumbar spine and hip bone loss in postmenopausal women at risk for osteoporosis. 1,4,5

Although fracture data were not captured and the drug was not tested in osteoporotic women, study results showed bone loss prevention at 12 months, which was sustained at 24 months. The improvement in bone mineral density from baseline was about 1% to 1.5%. This was compared with a bone loss of 1.8% in women taking placebo (P<.01).

In clinical studies, women taking CE/BZA versus placebo also have reported a lower incidence of painful intercourse,6 and some improvement in health-related quality of life and treatment satisfaction.7,8

In short, CE/BZA is a good option for symptomatic menopausal women with a uterus who have bothersome hot flashes, night sweats, and sleep disruptions and want to prevent bone loss.

What about adverse effects?

Dr. Pinkerton In general, CE/BZA has a favorable safety and tolerability profile, with an overall incidence of adverse events similar to placebo. The rates of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, cancers (breast, endometrial, and ovarian), and mortality are comparable to placebo in 2-year trials. These data are limited; studies have been conducted in healthy postmenopausal women. Future studies need to define the full risk profile, particularly among overweight or obese women and different ethnic groups and for longer-term use.

Is there a role among women with breast cancer?

Dr. Pinkerton CE/BZA has not been tested in women at risk for or with prior breast cancer. In preclinical trials of up to 2 years, involving healthy postmenopausal women, the rates for breast cancer with CE/BZA were similar to placebo. There are no long-term data, however, and there are no data in women at risk for breast cancer. I recommend that women who have or are at high risk for breast cancer consider nonhormonal treatment options.9–11

Has there been an associated increase in breast density with CE/BZA?

Dr. Pinkerton No. Data from two randomized clinical trials showed that the breast density changes with 12-month CE/BZA treatment was similar to placebo—which is markedly different from comparisons of placebo and combination estrogen-progestin therapy (EPT), where EPT increased breast density. If indeed this lack of an association translates into fewer breast cancers, it would be wonderful, but we do not have long-term data. We can tell our patients that using CE/BZA has not been shown to increase the risk of breast cancer, at least up to 2 years.

What makes CE/BZA different from traditional EPT?

Dr. Pinkerton There are two exciting differences:

- The incidences of breast pain and tenderness were found to be similar to placebo, and were significantly less than those with the comparator EPT (conjugated estrogens 0.45 mg plus medroxyprogesterone acetate [CE/MPA] 1.5 mg).9,10,12

- Bleeding and spotting rates were significantly less than those found with CE/MPA.13

In addition, high rates of amenorrhea have been found—comparable to placebo.13

CE/BZA is similar to traditional EPT in several ways. For instance, compared with placebo, at 2 years, CE/BZA was not found to increase the incidence of endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial thickness (increase from baseline was <1 mm and comparable to placebo), or endometrial cancers.14 Lastly, similar to EPT, there is probably a twofold risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) with BZA 20 mg alone.15 Importantly, there has been no additive effect on VTE risk when combining CE with BZA; however, we will need longer studies, in older women, to fully evaluate this risk.1

Overall, in symptomatic postmenopausal women with a uterus, randomized controlled data show the same improvement with CE/BZA as that seen with traditional oral EPTs, with improvements in hot flashes; night sweats, with fewer sleep disruptions; and prevention of bone loss. In addition, the changes in cholesterol (an increase in triglyceride levels) and effect on the vagina are the same. Yet, CE/BZA appears to have a neutral effect on the breast and protects against endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer without causing bleeding.9,10 CE/BZA’s VTE and stroke risks are expected to be similar to traditional oral EPT.

Therefore, the major benefit of CE/BZA for women who have a uterus is the lack of significant breast tenderness, lack of changes in breast density, and lack of vaginal bleeding that is often seen with traditional EPT.12

Then, is progestogen the harmful agent in traditional HT options?

Dr. Pinkerton There is evidence that estrogen plus progestogen therapy has more risk for breast cancer than estrogen alone. But in women who have a uterus, you need to protect against uterine cancer so, up until now, the only option was to add progestogen. Some studies suggest the risk of breast cancer may differ depending on the type of progestogen. So it’s a laudable goal to try to protect the endometrium without using a progestogen.

Given its safety profile, do you see CE/BZA being indicated for women without a uterus?

Dr. Pinkerton CE/BZA has been tested only in women with a uterus; there is no indication for using it in hysterectomized women. In the future, unless trial data show a benefit to hysterectomized women—by a reduction in breast cancer compared with estrogen alone—there would be no reason to add BZA to the CE for these women. You would just use CE or another type of estrogen alone.

Do you anticipate BZA being used alone?

Dr. Pinkerton For treating osteoporosis in postmenopausal women at increased fracture risk, BZA alone has greater benefits than risks. It is approved in other countries to prevent or treat osteoporosis. In 2008, Wyeth received an approval letter from the US Food and Drug Administration for BZA alone but, for whatever reason, the drug was not brought to market. BZA reduces the number of new lumbar spine fractures by 4% (vs 2% for placebo), with efficacy better in those with a higher risk of fractures. Like raloxifene, it has not been shown effective at reducing nonvertebral fractures, although it maintains spinal bone density.16

BZA available as monotherapy could tempt clinicians to pair it with other estrogens. We must recognize that the combination of the specific estrogen and BZA dose and type need to be balanced to provide endometrial hyperplasia protection. It would not be safe or effective to take BZA as a selective estrogen-receptor modulator and pair it with any other untested systemic estrogen. I do not anticipate, in this country, that BZA will become available as monotherapy.

New options are welcome

Dr. Moore Novel strategies for clinicians to optimally treat menopausal symptoms are always welcome. I look forward to more data from the SMART trials on CE/BZA and to moving forward as we gain experience with using this new treatment option.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

In this special installment of Cases in Menopause, I interview series contributor and menopause expert JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD. We discuss a fairly new therapy: the combination conjugated estrogen and bazedoxifene (CE/BZA; Duavee) for the treatment of moderate to severe hot flashes due to menopause and the prevention of menopausal osteoporosis.

Much of my practice has focused on the treatment of menopausal women, but which of my patients can benefit from this particular combination of CE 0.45 mg plus BZA 20 mg? I asked Dr. Pinkerton this question, and more.

Which patients can benefit most?

Dr. Pinkerton CE/BZA was tested in healthy postmenopausal women with a uterus at risk for bone loss who were reporting 50 or more moderate to severe hot flashes per week. The combination of CE and BZA is a good choice for women who have bothersome menopausal symptoms: hot flashes, night sweats, and sleep disruption or symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA)—although it’s not approved for VVA.

Efficacy and safety data show that compared with placebo:

- CE/BZA decreases the frequency and severity of hot flashes at 12 weeks, and those decreases are maintained at 12 months.1,2

- Women taking CE/BZA have greater improvements in sleep, with both decreased sleep disturbance and time to fall asleep.3

- CE/BZA maintained or prevented lumbar spine and hip bone loss in postmenopausal women at risk for osteoporosis. 1,4,5

Although fracture data were not captured and the drug was not tested in osteoporotic women, study results showed bone loss prevention at 12 months, which was sustained at 24 months. The improvement in bone mineral density from baseline was about 1% to 1.5%. This was compared with a bone loss of 1.8% in women taking placebo (P<.01).

In clinical studies, women taking CE/BZA versus placebo also have reported a lower incidence of painful intercourse,6 and some improvement in health-related quality of life and treatment satisfaction.7,8

In short, CE/BZA is a good option for symptomatic menopausal women with a uterus who have bothersome hot flashes, night sweats, and sleep disruptions and want to prevent bone loss.

What about adverse effects?

Dr. Pinkerton In general, CE/BZA has a favorable safety and tolerability profile, with an overall incidence of adverse events similar to placebo. The rates of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, cancers (breast, endometrial, and ovarian), and mortality are comparable to placebo in 2-year trials. These data are limited; studies have been conducted in healthy postmenopausal women. Future studies need to define the full risk profile, particularly among overweight or obese women and different ethnic groups and for longer-term use.

Is there a role among women with breast cancer?

Dr. Pinkerton CE/BZA has not been tested in women at risk for or with prior breast cancer. In preclinical trials of up to 2 years, involving healthy postmenopausal women, the rates for breast cancer with CE/BZA were similar to placebo. There are no long-term data, however, and there are no data in women at risk for breast cancer. I recommend that women who have or are at high risk for breast cancer consider nonhormonal treatment options.9–11

Has there been an associated increase in breast density with CE/BZA?

Dr. Pinkerton No. Data from two randomized clinical trials showed that the breast density changes with 12-month CE/BZA treatment was similar to placebo—which is markedly different from comparisons of placebo and combination estrogen-progestin therapy (EPT), where EPT increased breast density. If indeed this lack of an association translates into fewer breast cancers, it would be wonderful, but we do not have long-term data. We can tell our patients that using CE/BZA has not been shown to increase the risk of breast cancer, at least up to 2 years.

What makes CE/BZA different from traditional EPT?

Dr. Pinkerton There are two exciting differences:

- The incidences of breast pain and tenderness were found to be similar to placebo, and were significantly less than those with the comparator EPT (conjugated estrogens 0.45 mg plus medroxyprogesterone acetate [CE/MPA] 1.5 mg).9,10,12

- Bleeding and spotting rates were significantly less than those found with CE/MPA.13

In addition, high rates of amenorrhea have been found—comparable to placebo.13

CE/BZA is similar to traditional EPT in several ways. For instance, compared with placebo, at 2 years, CE/BZA was not found to increase the incidence of endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial thickness (increase from baseline was <1 mm and comparable to placebo), or endometrial cancers.14 Lastly, similar to EPT, there is probably a twofold risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) with BZA 20 mg alone.15 Importantly, there has been no additive effect on VTE risk when combining CE with BZA; however, we will need longer studies, in older women, to fully evaluate this risk.1

Overall, in symptomatic postmenopausal women with a uterus, randomized controlled data show the same improvement with CE/BZA as that seen with traditional oral EPTs, with improvements in hot flashes; night sweats, with fewer sleep disruptions; and prevention of bone loss. In addition, the changes in cholesterol (an increase in triglyceride levels) and effect on the vagina are the same. Yet, CE/BZA appears to have a neutral effect on the breast and protects against endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer without causing bleeding.9,10 CE/BZA’s VTE and stroke risks are expected to be similar to traditional oral EPT.

Therefore, the major benefit of CE/BZA for women who have a uterus is the lack of significant breast tenderness, lack of changes in breast density, and lack of vaginal bleeding that is often seen with traditional EPT.12

Then, is progestogen the harmful agent in traditional HT options?

Dr. Pinkerton There is evidence that estrogen plus progestogen therapy has more risk for breast cancer than estrogen alone. But in women who have a uterus, you need to protect against uterine cancer so, up until now, the only option was to add progestogen. Some studies suggest the risk of breast cancer may differ depending on the type of progestogen. So it’s a laudable goal to try to protect the endometrium without using a progestogen.

Given its safety profile, do you see CE/BZA being indicated for women without a uterus?

Dr. Pinkerton CE/BZA has been tested only in women with a uterus; there is no indication for using it in hysterectomized women. In the future, unless trial data show a benefit to hysterectomized women—by a reduction in breast cancer compared with estrogen alone—there would be no reason to add BZA to the CE for these women. You would just use CE or another type of estrogen alone.

Do you anticipate BZA being used alone?

Dr. Pinkerton For treating osteoporosis in postmenopausal women at increased fracture risk, BZA alone has greater benefits than risks. It is approved in other countries to prevent or treat osteoporosis. In 2008, Wyeth received an approval letter from the US Food and Drug Administration for BZA alone but, for whatever reason, the drug was not brought to market. BZA reduces the number of new lumbar spine fractures by 4% (vs 2% for placebo), with efficacy better in those with a higher risk of fractures. Like raloxifene, it has not been shown effective at reducing nonvertebral fractures, although it maintains spinal bone density.16

BZA available as monotherapy could tempt clinicians to pair it with other estrogens. We must recognize that the combination of the specific estrogen and BZA dose and type need to be balanced to provide endometrial hyperplasia protection. It would not be safe or effective to take BZA as a selective estrogen-receptor modulator and pair it with any other untested systemic estrogen. I do not anticipate, in this country, that BZA will become available as monotherapy.

New options are welcome

Dr. Moore Novel strategies for clinicians to optimally treat menopausal symptoms are always welcome. I look forward to more data from the SMART trials on CE/BZA and to moving forward as we gain experience with using this new treatment option.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Lobo RA, Pinkerton JV, Gass ML, et al. Evaluation of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and effects on metabolic bone parameters and overall safety profile. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1025–1038.

2. Pinkerton JV, Utian WH, Constantine GD, Olivier S, Pickar JH. Relief of vasomotor symptoms with the tissue-selective estrogen complex containing bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2009;16:(6)1116–1124.

3. Pinkerton JV, Pan K, Abraham L, et al. Sleep parameters and health-related quality of life with bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2014;21(3):252–259.

4. Lindsay R, Gallagher JC, Kagan R, Pickar JH, Constantine G. Efficacy of tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC) of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE) for osteoporosis prevention in at-risk postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1045–1052.

5. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Lindsay R, et al; SMART-5 Investigators. Effects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on the endometrium and bone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(2):E189–E198.

6. Kagan R, Williams RS, Pan K, Mirkin S, Pickar JH. A randomized, placebo- and active-controlled trial of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE) for treatment of moderate to severe vulvar/vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2010;17(2):281–289.

7. Utian W, Yu H, Bobula J, Mirkin S, Olivier S, Pickar JH. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens and quality of life in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2009;63:(4)329–335.

8. Abraham L, Pinkerton JV, Messig M, Ryan KA, Komm BS, Mirkin S. Menopause-specific quality of life across varying menopausal populations with conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene. Maturitas. 2014;78(3):212–218.

9. Harvey JA, Pinkerton JV, Baracat EC, Shi H, Chines AA, Mirkin S. Breast density changes in a randomized controlled trial evaluating bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2013;20:(2)138–145.

10. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Pan K, et al. Breast effects of bazedoxifene-conjugated estrogens. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(5):959–968.

11. Kaunitz AM. When should a menopausal woman discontinue hormone therapy? OBG Manag. 2014;26(2):59–65.

12. Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH, Racketa J, Mirkin S. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for menopausal symptom treatment and osteoporosis prevention. Climacteric. 2012;15:(5)411–418.

13. Archer DF, Lewis V, Carr BR, Olivier S, Pickar JH. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE): incidence of uterine bleeding in postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1039–1044.

14. Pickar JH, Yeh I-T, Bachmann G, Speroff L. Endometrial effects of a tissue selective estrogen complex (TSEC) containing bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens as a menopausal therapy. Fertil Steril. 2009; 92(3):1018–1024.

15. Mirkin S, Komm BS. Tissue-selective estrogen complexes for postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2013;76(3):213–220.

16. Ellis AG, Reginster JY, Luo X, et al. Bazedoxifene versus oral bisphosphonates for the prevention of nonvertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis at higher risk of fracture. Value Health. 2014;17(4):424–432.

1. Lobo RA, Pinkerton JV, Gass ML, et al. Evaluation of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and effects on metabolic bone parameters and overall safety profile. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1025–1038.

2. Pinkerton JV, Utian WH, Constantine GD, Olivier S, Pickar JH. Relief of vasomotor symptoms with the tissue-selective estrogen complex containing bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2009;16:(6)1116–1124.

3. Pinkerton JV, Pan K, Abraham L, et al. Sleep parameters and health-related quality of life with bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2014;21(3):252–259.

4. Lindsay R, Gallagher JC, Kagan R, Pickar JH, Constantine G. Efficacy of tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC) of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE) for osteoporosis prevention in at-risk postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1045–1052.

5. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Lindsay R, et al; SMART-5 Investigators. Effects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on the endometrium and bone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(2):E189–E198.

6. Kagan R, Williams RS, Pan K, Mirkin S, Pickar JH. A randomized, placebo- and active-controlled trial of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE) for treatment of moderate to severe vulvar/vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2010;17(2):281–289.

7. Utian W, Yu H, Bobula J, Mirkin S, Olivier S, Pickar JH. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens and quality of life in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2009;63:(4)329–335.

8. Abraham L, Pinkerton JV, Messig M, Ryan KA, Komm BS, Mirkin S. Menopause-specific quality of life across varying menopausal populations with conjugated estrogens/bazedoxifene. Maturitas. 2014;78(3):212–218.

9. Harvey JA, Pinkerton JV, Baracat EC, Shi H, Chines AA, Mirkin S. Breast density changes in a randomized controlled trial evaluating bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2013;20:(2)138–145.

10. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Pan K, et al. Breast effects of bazedoxifene-conjugated estrogens. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(5):959–968.

11. Kaunitz AM. When should a menopausal woman discontinue hormone therapy? OBG Manag. 2014;26(2):59–65.

12. Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH, Racketa J, Mirkin S. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for menopausal symptom treatment and osteoporosis prevention. Climacteric. 2012;15:(5)411–418.

13. Archer DF, Lewis V, Carr BR, Olivier S, Pickar JH. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens (BZA/CE): incidence of uterine bleeding in postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:1039–1044.

14. Pickar JH, Yeh I-T, Bachmann G, Speroff L. Endometrial effects of a tissue selective estrogen complex (TSEC) containing bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens as a menopausal therapy. Fertil Steril. 2009; 92(3):1018–1024.

15. Mirkin S, Komm BS. Tissue-selective estrogen complexes for postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 2013;76(3):213–220.

16. Ellis AG, Reginster JY, Luo X, et al. Bazedoxifene versus oral bisphosphonates for the prevention of nonvertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis at higher risk of fracture. Value Health. 2014;17(4):424–432.

5 IUD myths dispelled

Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), which include intrauterine devices (IUDs), implants, and injectables, are being offered to more and more women because of their demonstrated safety, efficacy, and convenience. In other countries, as many as 50% of all women use an IUD, but the United States has been slow to adopt this option.1 In 2002, approximately 2% of US women used an IUD.2 That percentage rose to 5.2% between 2006 and 2008, according to a recent survey.3 In that survey, women consistently expressed a high degree of satisfaction with this method of contraception.3

So why aren’t more US women using an IUD?

A general fear of the IUD persists. Women may not even know why they fear the device; they may have simply heard that it is “bad for you.” The negative press the IUD has received in this country probably is related to poor outcomes associated with use of the Dalkon Shield IUD in the 1970s. As a reminder, the Dalkon Shield was blamed for many cases of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and other negative sequelae as a result of poor patient selection. In addition, some authorities believe the design of the device was severely flawed, with a string that permitted bacteria to get from the vagina to the uterus and tubes.

Today, clinicians and many patients are better educated about the prevention of chlamydia, the primary causative organism of PID and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs); patients also are better informed about safe sex practices. We now know that women should be screened for behaviors that could increase their risk for PID and render them poor candidates for the IUD.

Clinicians also have expressed concerns about reimbursement issues related to the IUD, as well as confusion and difficulty with insertion procedures and the potential for litigation. In this article, I address some of these issues in an attempt to increase the use of this highly effective contraceptive.

What’s available today

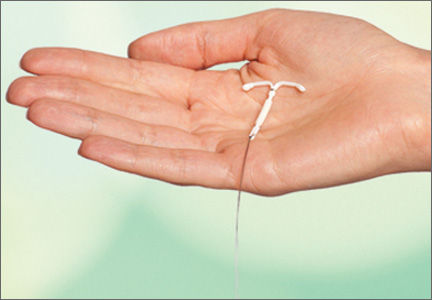

Today there are three IUDs available to US women (FIGURE):

The Copper IUD (ParaGard)—This device can be used for at least 10 years, although, in many countries, it is considered “permanent reversible contraception.” It has the advantage of being nonhormonal, making it an important option for women who cannot or will not use a hormonal contraceptive. Pregnancy is prevented through a “foreign body” effect and the spermicidal action of copper ions. The combination of these two influences prevents fertilization.4

The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) (Mirena)—This IUD is recommended for 5 years of use but may remain effective for as long as 7 years. It contains 52 mg of levonorgestrel, which it releases at a rate of approximately 20 μg/day. In addition to the foreign body effect, this IUD prevents pregnancy through progestogenic mechanisms: It thickens cervical mucus, thins the endometrium, and reduces sperm capacitation.5

The "mini" LNG-IUS (Skyla)—This newly marketed IUD is recommended for 3 years of use. It contains 13.5 mg of levonorgestrel, which it releases at a rate of 14 μg/day. It has the same mechanism of action as Mirena but may be easier to insert owing to its slightly smaller size and preloaded inserter.

Myth #1: The IUD is not suitable for teens and nulliparous women

This myth arose out of concerns about the smaller uterine cavity and cervical diameter of teens and nulliparous women. Today we know that an IUD can be inserted safely in this population. Moreover, because adolescents are at high risk for unintended pregnancy, they stand to benefit uniquely from LARC options, including the IUD. As the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends in a recent Committee Opinion on adolescents and LARCs, the IUD should be a “first-line” option for all women of reproductive age.6

Myth #2: An IUD should not be inserted immediately after childbirth

For many years, it was assumed that an IUD should be inserted in the postpartum period only after uterine involution was completed. However, in 2010, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, which included the following recommendations for breastfeeding or non–breast-feeding women:

• Mirena was given a Level 2 recommendation (advantages outweigh risks) for insertion within 10 minutes after delivery of the placenta

• The copper IUD was given a Level 1 recommendation (no restrictions) for insertion within the same time interval

• From 10 minutes to 4 weeks postpartum, both devices have a Level 2 recommendation for insertion

• Beyond 4 weeks, both devices have a Level 1 recommendation for insertion.7

Immediate post-delivery insertion of an IUD has several benefits, including:

• a reduction in the risk of unintended pregnancy in women who are not breastfeeding

• providing new mothers with a LARC method.

Myth #3: Antibiotics and NSAIDs should be administered

This myth arose from concerns about PID and insertion-related pain. However, a Cochrane Database review found no benefit for prophylactic use of antibiotics prior to insertion of the copper or LNG-IUS devices to prevent PID.8

In fact, data indicate that the incidence of PID is low among women who are appropriate candidates for an IUD. Similarly, Allen and colleagues found that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) did not ameliorate symptoms of cramping during or immediately after insertion of an IUD.9

Myth #4: IUD insertion is difficult

In reality, both the copper IUD and Mirena are easy to insert. In addition, the smaller LNG-IUS (Skyla) comes more completely preloaded in its inserter. In a published Phase 2 trial comparing Mirena with two smaller, lower-dose levonorgestrel-releasing devices, with the lowest-dose product corresponding to the marketed Skyla product, all 738 women given Mirena or the smaller devices experienced successful placement, with 98.5% of placements achieved on the first attempt.10

Various studies have been conducted to evaluate methods to ease insertion, including use of intracervical lidocaine, vaginal and/or oral administration of misoprostol (Cytotec), and vaginal estrogen creams. None was found to be effective in controlled trials. (See the sidebar, “Data-driven tactics for reducing pain on IUD insertion,” by Jennifer Gunter, MD, on page 28.) In the small percentage of women in whom it is difficult to pass a uterine sound through the external and internal os, cervical dilators may be beneficial. Gentle, progressive dilation can be accomplished easily with minimal discomfort to the patient, easing IUD insertion dramatically.

If a clinician does not insert IUDs on a frequent basis, it is prudent to look over the insertion procedure prior to the patient’s arrival. The procedure then can be reviewed with the patient as part of informed consent, which should be documented in the chart.

No steps in the recommended insertion procedure should be omitted, and charting should reflect each step:

1. Perform a bimanual exam

2. Document the appearance of the vagina and cervix

3. Use betadine or another cleansing solution on the cervical portio

4. Apply the tenaculum to the cervix (anterior lip if the uterus is anteverted, posterior lip if it is retroverted)

5. Sound the uterus to determine the optimal depth of IUD insertion. (The recommended uterine depth is 6 to 10 cm. A smaller uterus increases the likelihood of perforation, pain, and expulsion.)

6. Insert the IUD (and document the ease or difficulty of insertion)

7. Trim the string to an appropriate length

8. Assess the patient’s condition after insertion

9. Schedule a return visit in 4 weeks.

Related Article Let’s increase our use of IUDs and improve contraceptive effectiveness in this country Robert L. Barbieri, MD

Myth #5: Perforation is common

Uterine perforation occurs in approximately 1 in every 1,000 insertions.11 If perforation occurs with a copper IUD, remove the device to prevent the formation of intraperitoneal adhesions.12 The LNG-IUS devices do not produce this reaction, although most experts agree that they should be removed when a perforation occurs.13

Anecdotal evidence suggests that perforation may be more common among breastfeeding women, but this finding is far from definitive.

How to select an IUD for a patient: 3 case studies

CASE 1: Heavy bleeding and signs of endometriosis

Amelia, a 26-year-old nulliparous white woman, visits your office for routine examination and asks about her contraceptive options. She has no notable medical history. She has a body mass index (BMI) of 20.2 kg/m2 and exercises regularly. Menarche occurred at age 13. Her menstrual cycles are regular but are getting heavier; she now “soaks” a tampon every hour. She also complains that her cramps are more difficult to manage. She takes ibuprofen 600 mg every 6 hours during the days of heaviest bleeding and cramping, but that approach doesn’t seem to be effective lately. She is in a stable sexual relationship with her boyfriend of 2 years, now her fiancé. They have been using condoms consistently as contraception but don’t plan to start a family for a “few years.” Amelia reports that their sex life is good, although she has been experiencing pain with deep penetration for about 6 months.

Examination reveals a clear cervix and nontender uterus, although the uterus is retroverted. Palpation of the ovaries indicates that they are normal. Her main complaints: dysmenorrhea and heavy menstrual bleeding.

What contraceptive would you suggest?

Amelia would be a good candidate for the LNG-IUS because she is in a stable relationship and wants to postpone pregnancy for several years. Although she has some symptoms suggestive of endometriosis (dyspareunia), they could be relieved by this method.14 Because thinning of the endometrial lining is an inherent mechanism of action of the LNG-IUS, this method could reduce her heavy bleeding.

She should be advised of the risks and benefits of the LNG-IUS, which can be inserted when she begins her next menstrual cycle.

CASE 2: Mother of two with no immediate desire for pregnancy

Tamika is a 19-year-old black woman (G2P2) who has arrived at your clinic for her 6-week postpartum visit. She is not breastfeeding. Her BMI is 25.7 kg/m2. She reports that her baby and 2-year-old are doing “OK” and says she does not want to get pregnant again anytime soon. She is in a relationship with the father of her baby and says he is “working a good job and taking care of me.” Her menstrual cycles have always been normal, with no cramping or heavy bleeding.

Examination reveals that her cervix is clear, her uterus is anteverted and nontender, and her ovaries appear to be normal.

Would this patient be a good candidate for a LARC?

Tamika is an excellent candidate for the copper IUD or LNG-IUS and should be educated about both methods. If she chooses an IUD, it can be inserted at the start of her next menstrual period.