User login

Family physicians encounter skin rashes on a daily basis. First steps in making the diagnosis include identifying the characteristics of the rash and determining whether the eruption is accompanied by fever or any other symptoms. In the article that follows, we review 8 viral exanthems of childhood that range from the common (chickenpox) to the not-so-common (Gianotti-Crosti syndrome).

Varicella-zoster virus

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is a human neurotropic alphaherpesvirus that causes a primary infection commonly known as chickenpox (varicella).1 This disease is usually mild and resolves spontaneously.

This highly contagious virus is transmitted by directly touching the blisters, saliva, or mucus of an infected person. It is also transmitted through the air by coughing and sneezing. VZV initiates primary infection by inoculating the respiratory mucosa. It then establishes a lifelong presence in the sensory ganglionic neurons and, thus, can reactivate later in life causing herpes zoster (shingles), which can affect cranial, thoracic, and lumbosacral dermatomes. Acute or chronic neurologic disorders, including cranial nerve palsies, zoster paresis, vasculopathy, meningoencephalitis, and multiple ocular disorders, have been reported after VZV reactivation resulting in herpes-zoster.1

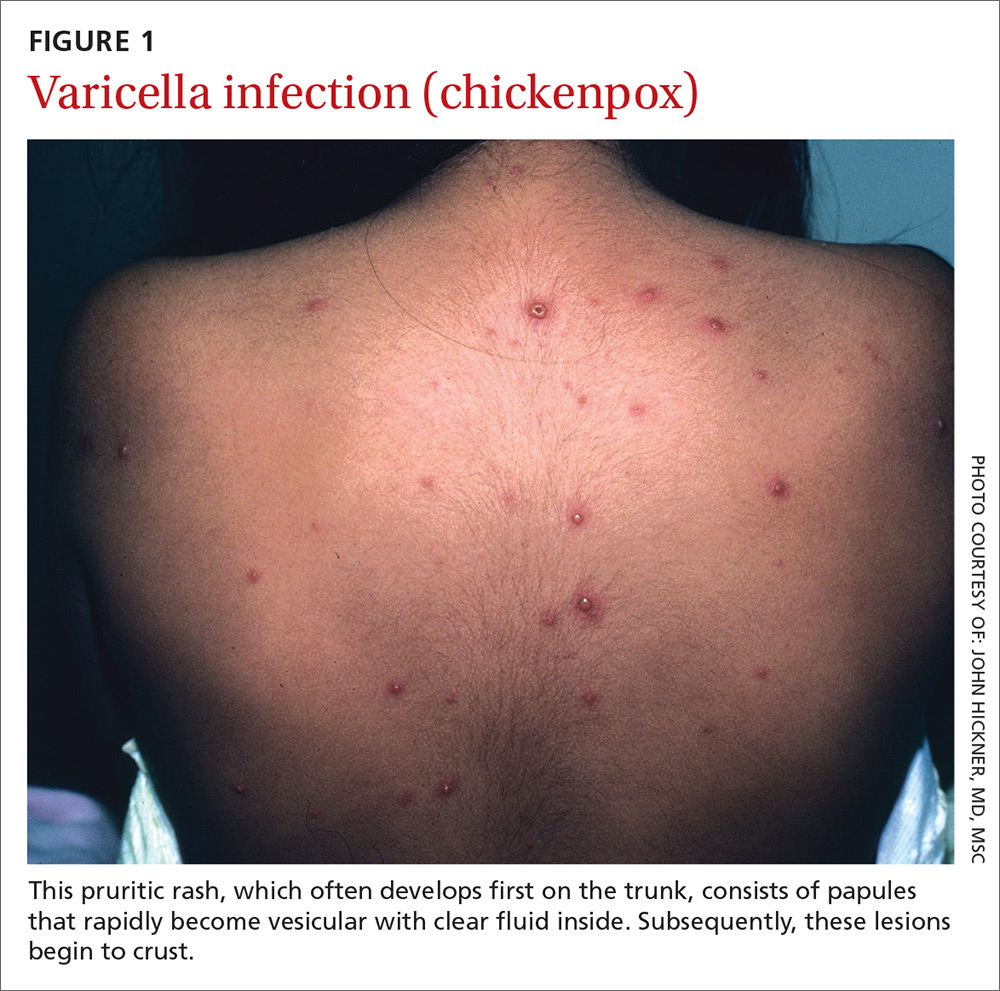

Presentation. With varicella, an extremely pruritic rash follows a brief prodromal stage consisting of a low-grade fever, upper respiratory tract symptoms, tiredness, and fatigue. This exanthem develops rapidly, often beginning on the chest, trunk, or scalp and then spreading to the arms and legs (centrifugally) (FIGURE 1). Varicella also affects mucosal areas of the body, such as the conjunctiva, mouth, rectum, and vagina.

The lesions are papules that rapidly become vesicular with clear fluid inside. Subsequently, the lesions begin to crust. Scabbing occurs within 10 to 14 days. A sure sign of chickenpox is the presence of papules, vesicles, and crusting lesions in close proximity.

Complications. The most common complications of chickenpox—especially in children—are invasive streptococcal and staphylococcal infections.2 The most serious complication occurs when the virus invades the spinal cord, causing myelitis or affecting the cerebral arteries, leading to vasculopathy. Diagnosis of VZV in the central nervous system is based on isolation of the virus in cerebral spinal fluid by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Early diagnosis is important to minimize morbidity and mortality.

Reactivation is sometimes associated with post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN), a severe neuropathic pain syndrome isolated to the dermatomes affected by VZV. PHN can cause pain and suffering for years after shingles resolves, and sometimes is refractory to treatment. PHN may reflect a chronic varicella virus ganglionitis.

A number of treatment choices exist for shingles, but not so much for varicella

Oral treatment. Oral medications such as acyclovir and its prodrug valacyclovir are the current gold standards for the treatment of VZV.3

Famciclovir, the prodrug of penciclovir, is more effective than valacyclovir at resolving acute herpes zoster rash and shortening the duration of PHN.4 Gabapentinoids (eg, pregabalin) are the only oral medications approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat PHN.5

Topical medications can also be used. Lidocaine 5% is favored as first-line therapy for the amelioration of pain due to shingles, as it provides modest pain relief with a better safety and tolerability profile than capsaicin 8% patch, which is a second-line choice. The latter must be applied multiple times daily, has minimal analgesic efficacy, and frequently causes initial pain upon application.

Gabapentinoids and topical analgesics can be used in combination due to the low propensity for drug interactions.6,7 The treatment of choice for focal vasculopathy is intravenous acyclovir, usually for 14 days, although immunocompromised patients should be treated for a longer period of time. Also consider 5 days of steroid therapy for patients with VZV vasculopathy.8

Non-FDA approved treatments include tricyclic antidepressants (TCA), such as amitriptyline, nortriptyline, and desipramine, which are sometimes used as first-line therapy for shingles. TCAs may not work well in patients with burning pain, and can have significant adverse effects, including possible cardiotoxicity.9

Opioids, including oxycodone, morphine, methadone, and tramadol, are sometimes used in pain management, but concern exists for abuse. Because patients may develop physical dependence, use opioids with considerable caution.10

Prevention. The United States became the first country to institute a routine varicella immunization program after a varicella vaccine (Varivax) was licensed in 1995.11 The vaccine has reduced the number of varicella infection cases dramatically.11 Vaccine effectiveness is high, and protective herd immunity is obtained after 2 doses.11-13 The vaccine is administered to children after one year of age with a booster dose administered after the fourth birthday.

A live, attenuated VZV vaccine (Zostavax) is given to individuals ≥60 years of age to prevent or attenuate herpes zoster infection. This vaccine is used to boost VZV-specific cell-mediated immunity in adults, thereby decreasing the burden of herpes zoster and the pain associated with PHN.14

Roseola

Roseola infantum, also known as exanthema subitum and sixth disease, is a common mild acute febrile illness of childhood caused by infection with human herpesvirus (HHV) 6 (the primary agent causing roseola) or 7 (a secondary causal agent for roseola).15 HHV-6 has 2 variants (HHV-6a and HHV-6b). Roseola infantum is mostly associated with the HHV-6b variant, which predominantly affects children 6 to 36 months of age.16

The virus replicates in the salivary glands and is shed through saliva, which is the route of transmission. After a 10- to 15-day incubation period, it remains latent in lymphocytes and monocytes, thus persisting in cells and tissues. It may reactivate late in life, particularly in immunosuppressed individuals. Reactivated infection in immunocompromised patients may be associated with serious illness such as encephalitis/encephalopathy. In patients who have received a bone marrow transplant, it can induce graft vs host disease.17

Presentation. The virus causes a 5- to 6-day illness characterized by high fever (temperature as high as 105°-106° F), miringitis (inflammation of tympanic membranes), and irritability. Once defervescence occurs, an erythematous morbilliform exanthem appears.The rash, which has a discrete macular/papular soft-pink appearance, starts on the trunk and spreads centrifugally to the extremities, neck, and face (FIGURE 2). It usually resolves within one to 2 days.

Complications. The most common complication of roseola is febrile seizures.17 Less common ones include encephalitis, encephalopathy, fatal hemophagocytic syndrome,18 or fulminant hepatitis.19

Treatment and prevention. Treatment depends on symptoms and may include antipyretics for fever management and liquids to maintain hydration. Recovery is usually complete with no significant sequelae. If a child develops a seizure, no antiepileptic drugs are recommended. No vaccine exists.

Fifth disease

Human parvovirus B19, a minute ssDNA virus, was first associated with human disease in 1981, when it was linked to an aplastic crisis in a patient with sickle cell disease.20 Since then researchers have determined that it is also the cause of erythema infectiosum or fifth disease of childhood. The B19 virus can also cause anemia in the fetus as well as hydrops fetalis. It has been linked to arthralgia and arthritis (especially in adults). There is an association with autoimmune diseases with characteristics similar to rheumatoid arthritis.20

The B19 virus is transmitted via aerosolized respiratory secretions, contaminated blood, or the placenta. The virus replicates in erythroid cells in bone marrow and peripheral blood, thus inhibiting erythropoiesis.21 Once the rash appears, the virus is no longer infectious.22 Seasonal peaks occur in the late winter and spring, with sporadic infections throughout the year.23 More than 70% of the adult population is seropositive for this virus.20

Presentation. Erythema infectiosum is a mild illness in childhood with an incubation period of 6 to 18 days. It presents with a characteristic malar rash on the face that gives patients a slapped cheek appearance (FIGURE 3A). A softer pink-colored “lacy” reticulated rash that blanches when touched may appear on the trunk, arms, and legs (FIGURE 3B).

Another presentation, which involves the hands and feet (glove and sock syndrome) (FIGURES 3C and 3D), consists of a purpuric eruption with painful edema and numerous small confluent petechiae.22,24 A majority of patients present with inflammatory symptoms that tend to resolve without sequelae within 3 weeks of infection.23

A rash is not as prevalent in adults as in children. Adults often present with more systemic systems, such as a debilitating influenza-like illness, arthropathy, transient aplastic anemia in sickle cell-affected individuals, and persistent viral suppression of erythrocyte production in immunocompromised patients and organ-transplant recipients.

Complications. The B19 virus can cause spontaneous abortion in pregnant women and anemia and hydrops fetalis in the fetus.22 Arthritis can occur in children, but is more common in adults, especially in women. The arthritis tends to be symmetrical and affects small joints such as the hands, wrists, and knees.

In one study of parvovirus B19 involving 633 children with sickle cell disease, 68 children developed transient red cell aplasia, 19% of them developed splenic sequestration, and 12% developed acute chest syndrome, a lung-related complication of sickle cell disease that can lower the level of oxygen in the blood and can be fatal.25

Treatment and prevention. Treatment of B19 infection is symptomatic; for example, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are used if joint pain develops. No vaccine exists.

Hand, foot, and mouth disease

Hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) is caused by the picornavirus family, including the Coxsackievirus, Enterovirus, and Echovirus. Infections commonly occur in the spring, summer, and fall. The virus primarily affects infants and children <10 years of age with the infection typically lasting 7 to 10 days.26

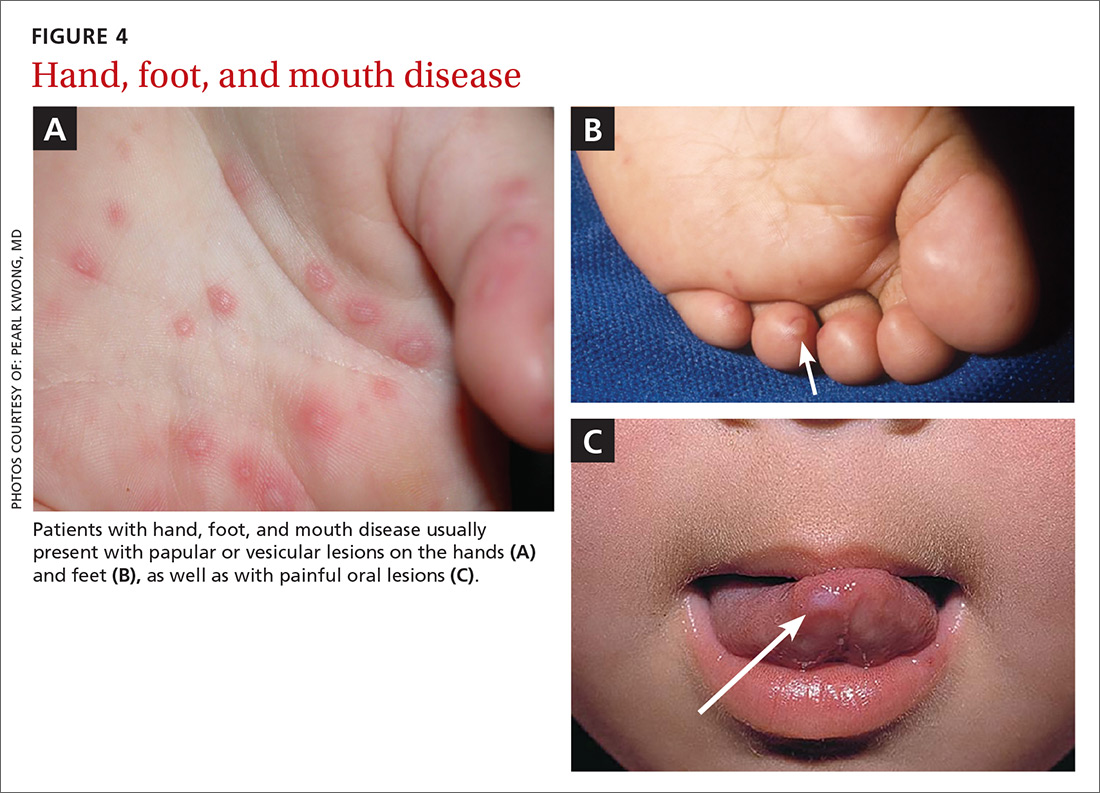

Presentation. The disease usually presents with a febrile episode, progressing to nasal congestion and malaise. One to 2 days later, the classic rash appears. Patients with HFMD usually present with papular or vesicular lesions on the hands and feet and painful oral lesions (FIGURES 4A, 4B, and 4C). The rash may also affect other parts of the body including the legs and buttocks. Desquamation of nails may occur up to one month after the HFM infection.27 Most cases are diagnosed by clinical presentation, but infection can be confirmed by PCR of vesicular lesion fluid.

Complications. In addition to being caused by Coxsackievirus, HFMD may be caused by human Enterovirus A serotype 71 (HEVA-71), which is associated with a high prevalence of acute neurologic disease including aseptic meningitis, poliomyelitis-like paralysis, and encephalitis.26 Of 764 HFMD patients enrolled in a prospective study, 214 cases were associated with Coxsackievirus A 16 (CVA16) infection and 173 cases were associated with HEVA-71 infection. Rare cases of HFMD have led to encephalitis, meningitis, flaccid paralysis, and death.26

Treatment and prevention. HFMD is usually self-limited, and treatment is supportive. There has been interest in developing an HFMD vaccine, but no products are as yet commercially available.

Rubella

Rubella, also known as the German measles or the 3-day measles, is caused by the rubella virus, which is transmitted via respiratory droplets. Up to half of rubella infections are asymptomatic.28-30

Presentation. Rubella typically has an incubation period of 12 to 24 days, with a 5-day prodromal period characterized by fever, headache, and other symptoms typical of an upper respiratory infection, including sore throat, arthralgia, and tender lymphadenopathy.28

The rash often starts as erythematous or as rose-pink macules on the face that progress down the body. The rash can cover the trunk and extremities within 24 hours. (For photos, see https://www.cdc.gov/rubella/about/photos.html.)

Patients are infectious from 7 days prior to the appearance of the rash to 7 days after resolution of the rash. Given the potentially prolonged infectious period, patients hospitalized for rubella infection should be placed on droplet precautions, and children should be kept from day care and school for 7 days after the appearance of the rash.28

Rubella is typically a mild disease in immunocompetent patients; however, immunocompromised patients may develop pneumonia, coagulopathies, or neurologic sequelae including encephalitis.

Complications. Rubella infection, especially during the first trimester, can lead to spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, or congenital rubella syndrome (CRS), a condition characterized by congenital cataracts and “blueberry muffin” skin lesions.31 Infants affected by CRS can also have heart defects, intellectual disabilities, deafness, and low birth weight. Diagnosis of primary maternal infection should be made with serologic tests. Fetal infection can be determined by detection of fetal serum IgM after 22 to 24 weeks of gestation or with viral culture of amniotic fluid.31

Treatment and prevention. Currently, no antiviral treatments are available; however, vaccines are highly effective at preventing infection. Rubella vaccine is usually given as part of the measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine, which is administered at age 12 to 15 months and again between 4 and 6 years of age.

Measles

Measles is a highly contagious disease caused by a virus that belongs to the Morbillivirus genus of the family Paramyxoviridae. Infection occurs through inhalation of, or direct contact with, respiratory droplets from infected people.32

Presentation. People with measles often present with what starts as a macular rash on the face that then spreads downward to the neck, trunk, and extremities (for photos, see http://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/index.html). As the disease progresses, papules can develop and the lesions may coalesce.

The rash is often preceded by 3 to 4 days of malaise and fever (temperature often greater than 104° F), along with the classic symptom triad of cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis. Koplik spots—clustered white lesions on the buccal mucosa—are often present prior to the measles rash and are pathognomonic for measles infection.33

Because the symptoms of measles are easily confused with other viral infections, suspected cases of measles should be confirmed via IgG and IgM antibody tests, by reverse transcription-PCR, or both.34,35 For limited and unusual cases, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention can perform a plaque reduction neutralization assay.35

Complications. Measles infection is self-limited in immunocompetent patients. The most common complications are diarrhea and ear infections, but more serious complications, such as pneumonia, hearing loss, and encephalitis, can occur. Children <2 years of age, particularly boys, are at an increased risk of developing subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, a fatal neurologic disorder that can develop years after the initial measles infection.33,36

Treatment and prevention. Treatment is supportive and usually consists of acetaminophen or NSAIDs and fluids.

A live attenuated version of the measles vaccine is highly effective against the measles virus and has greatly reduced the number of measles cases globally.37 The measles vaccine is usually given in 2 doses—the first one after one year of age, and the second one before entering kindergarten. The most common adverse reactions to the vaccine are pain at the injection site and fever. Despite the fact that the MMR vaccine is effective and relatively benign, measles outbreaks continue to occur, as some parents forego routine childhood immunizations because of religious or other personal beliefs or safety concerns.38

Molluscum contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is caused by the MC virus, a member of the poxvirus family. The virus is transmitted by direct contact with the skin lesions. This skin condition is seen mainly in children, although it can occur in adults.

A study conducted in England and Wales that obtained information from the Royal College of General Practitioners reported an incidence of 15.0-17.2/1000 population over a 10-year period (1994-2003) with no variation between sexes.39 There is an association between atopic dermatitis and MC; 24% of children with atopic dermatitis develop MC.40 There might also be an association between recent swimming in a public pool and development of MC lesions.41

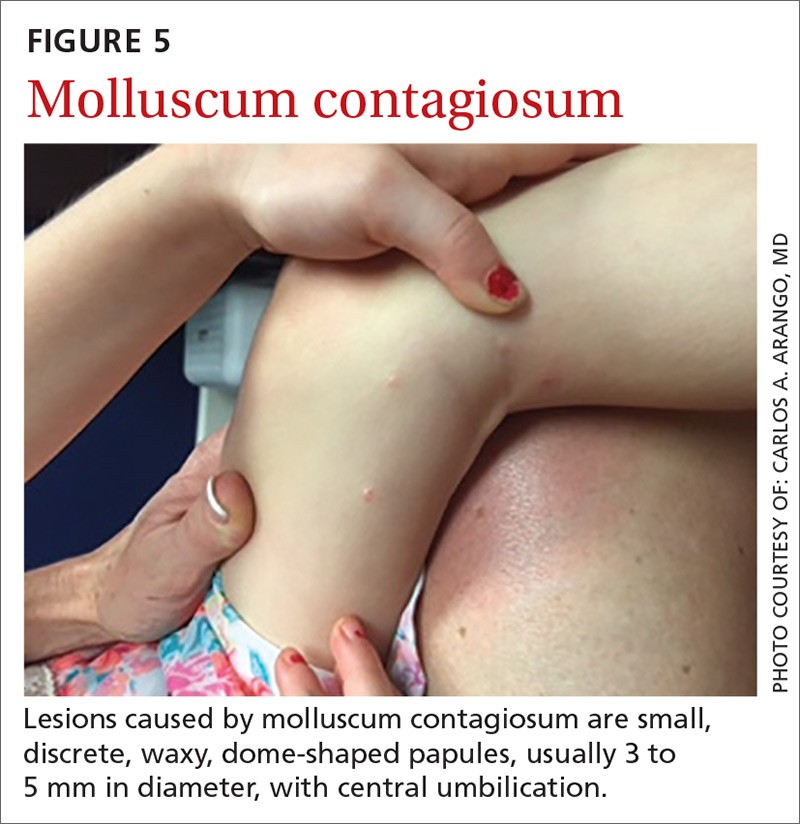

Presentation. Lesions caused by MC are small, discrete, waxy dome-shaped papules with central umbilication that are usually 3 to 5 mm in diameter (FIGURE 5).42,43 In immunocompetent patients, there are usually fewer than 20 lesions, which resolve within a year. However, in immunocompromised patients, the number of lesions is usually higher, and the diameter of each may be greater than 1 cm.42

Complications. The lesions are usually self-limited, but on occasion can become secondarily infected, usually with gram-positive organisms such as Staphylococcus aureus. Very rarely, abscesses develop requiring topical and/or systemic antimicrobials and perhaps incision and drainage.44

Treatment and prevention. Because the infection is often self-limited and benign, the preferred therapeutic modality is watchful waiting. Other treatments for MC include curettage, chemical agents, immune modulators, and antiviral drugs. A 2009 Cochran review of 11 studies involving 495 patients found “no single intervention to be convincingly effective in the treatment of molluscum contagiosum.”45 And no vaccine exists.

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome (GCS), also known as papular acrodermatitis of childhood, is a relatively rare, self-limited exanthema that usually affects infants and children 6 months to 12 years of age (peak occurrence is in one- to 6-year-olds). Although there have been reports of adults with this syndrome, it is unusual in this age group.

Pathogenesis is still unknown. Although GCS itself isn’t contagious, the viruses that can cause it may be. Initially, researchers believed that GCS was linked to acute hepatitis B virus infection, but more recently other viral and bacterial infections have been associated with the condition.46

The most commonly associated virus in the United States is Epstein-Barr virus; other viruses include hepatitis A virus, cytomegalovirus, coxsackievirus, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza virus, rotavirus, the mumps virus, parvovirus, and molluscum contagiosum.

Bacterial infections, such as those caused by Bartonella henselae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and group A streptococci may trigger GCS.47-49

Vaccines that have been implicated in GCS include those for polio, diphtheria/pertussis/tetanus, MMR, hepatitis A and B, as well as the influenza vaccine.48-51

Presentation. While GCS is relatively rare, its presentation is classic, making it easy to diagnose once it’s included in the differential. The pruritic rash usually consists of acute-onset monomorphous, flat-topped or dome-shaped red-brown papules and papulovesicles, one to 10 mm in size, located symmetrically on the face (FIGURE 6), the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs, and, less commonly, the buttocks. It rarely affects other parts of the body.48

The diagnosis is usually based on the characteristic rash and the benign nature of the condition; other than the rash, patients are typically asymptomatic and healthy. Sometimes a biopsy is performed and it reveals a dense lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with a strong cytoplasmic immunopositivity for beta-defensin-4 in the stratum corneum, granulosum, and spinosum.52

The lesions spontaneously resolve within 8 to 12 weeks. GCS usually presents during spring and early summer and affects both sexes equally.46

Treatment and prevention. Treatment is usually symptomatic, with the use of oral antihistamines if the lesions become pruritic. Topical steroids may be used, and, in a few cases, oral corticosteroids may be considered. No vaccine exists.

CORRESPONDENCE

Carlos A. Arango, MD, 8399 Bayberry Road, Jacksonville, FL 32256; carlos.arango@jax.ufl.edu.

1. Kennedy PG, Rovnak J, Badani H, et al. A comparison of herpes simplex virus type 1 and varicella-zoster virus latency and reactivation. J Gen Virol. 2015;96(Pt 7):1581-1602.

2. Blumental S, Sabbe M, Lepage P, the Belgian Group for Varicella. Varicella paediatric hospitalisations in Belgium: a 1-year national survey. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101:16-22.

3. Sampathkumar P, Drage LA, Martin DP. Herpes zoster (shingles) and postherpetic neuralgia. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2009;84:274-280.

4. Ono F, Yasumoto S, Furumura M, et al. Comparison between famciclovir and valacyclovir for acute pain in adult Japanese immunocompetent patients with herpes zoster. J Dermatol. 2012;39:902-908.

5. Massengill JS, Kittredge JL. Practical considerations in the pharmacological treatment of post-herpetic neuralgia for the primary care provider. J Pain Res. 2014;7:125-132.

6. Nalamachu S, Morley-Forster P. Diagnosing and managing postherpetic neuralgia. Drugs & Aging. 2012;29:863-869.

7. Hempenstall K, Nurmikko TJ, Johnson RW, et al. Analgesic therapy in postherpetic neuralgia: a quantitative systematic review. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e164.

8. Gilden D, Cohrs RJ, Mahalingam R, et al. Varicella zoster virus vasculopathies: diverse clinical manifestations, laboratory features, pathogenesis, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2009;9:731-740.

9. Stankus SJ, Dlugopolski M, Packer D. Management of herpes zoster (shingles) and post herpetic neuralgia. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61:2437-2444.

10. Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Audette J, et al. Recommendations for the pharmacological management of neuropathic pain: an overview and literature update. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(3 Suppl):S3-S14.

11. Thomas CA, Shwe T, Bixler D, et al. Two-dose varicella vaccine effectiveness and rash severity in outbreaks of varicella among public school students. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33:1164-1168.

12. Helmuth IG, Poulsen A, Suppli CH, et al. Varicella in Europe-a review of the epidemiology and experience with vaccination. Vaccine. 2015;33:2406-2413.

13. Marin M, Marti M, Kambhampati A, et al. Global varicella vaccine effectiveness: a metanalysis. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e20153741.

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What everyone should know about shingles vaccine. Available at: www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/shingles/public/index.html. Accessed September 12, 2017.

15. Tanaka K, Kondo T, Torigoe S, et al. Human herpesvirus 7: another causal agent for roseola (exanthem subitum). J Pediatr. 1994;125:1-5.

16. Caserta MT, Mock DJ, Dewhurst S. Human herpesvirus 6. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:829-833.

17. Koch WC. Fifth (human parvovirus) and sixth (herpesvirus 6) diseases. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2001;14:343-356.

18. Marabelle A, Bergeron C, Billaud G, et al. Hemophagocytic syndrome revealing primary HHV-6 infection. J Pediatr. 2010;157:511.

19. Charnot-Katsikasa A, Baewer D, Cook L, et al. Fulminant hepatic failure attributed to infection with human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) in an immunocompetent woman: a case report and review of the literature. J Clin Virol. 2016;75:27-32.

20. Corcoran A, Doyle S. Advances in the biology, diagnosis and host-pathogen interactions of parvovirus B19. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53(Pt 6):459-475.

21. Dolin R. Parvovirus erythema infectiousum, Aplastic anemia. In: Mandell, Douglas, Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone Inc; 1990:1231-1232.

22. Servey JT, Reamy BV, Hodge J. Clinical presentations of parvovirus B19 infection. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75:373-376.

23. Martin DR, Schlott DW, Flynn JA. Clinical problem-solving. No respecter of age. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1856-1859.

24. Ozaydin V, Eceviz A, Sari Dogan F, et al. An adult patient who presented to emergency service with a papular purpuric gloves and socks syndrome: a case report. Turk J Emerg Med. 2014;14:179-181.

25. Smith-Whitley K, Zhao H, Hodinka RL, et al. Epidemiology of human parvovirus B19 in children with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2004;103:422-427.

26. Tu PV, Thao NT, Perera D, et al. Epidemiologic and virologic investigation of hand, foot, and mouth disease, Southern Vietnam, 2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1733-1741.

27. Ferrari B, Taliercio V, Hornos L, et al. Onychomadesis associated with mouth, hand and foot disease. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2013;111:e148-e151.

28. Alter SJ, Bennett JS, Koranyi K, et al. Common childhood viral infections. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2015;45:21-53.

29. Lambert N, Strebel P, Orenstein W, et al. Rubella. Lancet. 2015;385:2297-2307.

30. Silasi M, Cardenas I, Kwon JY, et al. Viral infections during pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2015;73:199-213.

31. Tang JW, Aarons E, Hesketh LM, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital rubella infection in the second trimester of pregnancy Prenat Diagn. 2003;23:509-512.

32. Naim HY. Measles virus. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11:21-26.

33. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles (Rubeola). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/index.html. Accessed April 28, 2016.

34. Takao S, Shigemoto N, Shimazu Y, et al. Detection of exanthematic viruses using a TaqMan real-time PCR assay panel in patients with clinically diagnosed or suspected measles. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2012;65:444-448.

35. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles (Rubeola). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/measles/lab-tools/rt-pcr.html. Accessed April 28, 2016.

36. Griffin DE, Lin WH, Pan CH. Measles virus, immune control, and persistence. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2012;36:649-662.

37. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles, vaccination. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/measles/vaccination.html. Accessed April 28, 2016.

38. Campos-Outcalt D. Measles: Why it’s still a threat. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:446-449.

39. Olsen JR, Gallacher J, Piguet V, et al. Epidemiology of molluscum contagiosum in children: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2014;31:130-136.

40. Dohil MA, Lin P, Lee J, et al. The epidemiology of molluscum contagiosum in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:47-54.

41. Choong KY, Roberts LJ. Molluscum contagiosum, swimming and bathing: a clinical analysis. Australas J Dermatol. 1999;40:89-92.

42. Martin P. Interventions for molluscum contagiosum in people infected with human immunodeficiency virus: a systematic review. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:956-966.

43. Chen X, Anstey AV, Bugert JJ. Molluscum contagiosum virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:877-888.

44. Lacour M, Posfay-Barbe KM, La Scala GC. Staphylococcus lugdunensis abscesses complicating molluscum contagiosum in two children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:289-291.

45. van der Wouden JC, van der Sande R, van Suijlekom-Smit LW, et al. Interventions for cutaneous molluscum contagiosum. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;CD004767.

46. Tagawa C, Speakman M. Photo quiz. Papular rash in a child after a fever. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:59-60.

47. Brandt O, Abeck D, Gianotti R, et al. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:136-145.

48. Retrouvey M, Koch LH, Williams JV. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome following childhood vaccinations. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:137-138.

49. Velangi SS, Tidman MJ. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome after measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:1122-1123.

50. Lacour M, Harms M. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome as a result of vaccination and Epstein-Barr virus infection. Eur J Pediatr. 1995;154:688-689.

51. Kroeskop A, Lewis AB, Barril FA, et al. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome after H1N1-influenza vaccine. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:595-596.

52. Caltabiano R, Vecchio GM, De Pasquale R, et al. Human beta-defensin 4 expression in Gianotti-Crosti. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2013;21:43-47.

Family physicians encounter skin rashes on a daily basis. First steps in making the diagnosis include identifying the characteristics of the rash and determining whether the eruption is accompanied by fever or any other symptoms. In the article that follows, we review 8 viral exanthems of childhood that range from the common (chickenpox) to the not-so-common (Gianotti-Crosti syndrome).

Varicella-zoster virus

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is a human neurotropic alphaherpesvirus that causes a primary infection commonly known as chickenpox (varicella).1 This disease is usually mild and resolves spontaneously.

This highly contagious virus is transmitted by directly touching the blisters, saliva, or mucus of an infected person. It is also transmitted through the air by coughing and sneezing. VZV initiates primary infection by inoculating the respiratory mucosa. It then establishes a lifelong presence in the sensory ganglionic neurons and, thus, can reactivate later in life causing herpes zoster (shingles), which can affect cranial, thoracic, and lumbosacral dermatomes. Acute or chronic neurologic disorders, including cranial nerve palsies, zoster paresis, vasculopathy, meningoencephalitis, and multiple ocular disorders, have been reported after VZV reactivation resulting in herpes-zoster.1

Presentation. With varicella, an extremely pruritic rash follows a brief prodromal stage consisting of a low-grade fever, upper respiratory tract symptoms, tiredness, and fatigue. This exanthem develops rapidly, often beginning on the chest, trunk, or scalp and then spreading to the arms and legs (centrifugally) (FIGURE 1). Varicella also affects mucosal areas of the body, such as the conjunctiva, mouth, rectum, and vagina.

The lesions are papules that rapidly become vesicular with clear fluid inside. Subsequently, the lesions begin to crust. Scabbing occurs within 10 to 14 days. A sure sign of chickenpox is the presence of papules, vesicles, and crusting lesions in close proximity.

Complications. The most common complications of chickenpox—especially in children—are invasive streptococcal and staphylococcal infections.2 The most serious complication occurs when the virus invades the spinal cord, causing myelitis or affecting the cerebral arteries, leading to vasculopathy. Diagnosis of VZV in the central nervous system is based on isolation of the virus in cerebral spinal fluid by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Early diagnosis is important to minimize morbidity and mortality.

Reactivation is sometimes associated with post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN), a severe neuropathic pain syndrome isolated to the dermatomes affected by VZV. PHN can cause pain and suffering for years after shingles resolves, and sometimes is refractory to treatment. PHN may reflect a chronic varicella virus ganglionitis.

A number of treatment choices exist for shingles, but not so much for varicella

Oral treatment. Oral medications such as acyclovir and its prodrug valacyclovir are the current gold standards for the treatment of VZV.3

Famciclovir, the prodrug of penciclovir, is more effective than valacyclovir at resolving acute herpes zoster rash and shortening the duration of PHN.4 Gabapentinoids (eg, pregabalin) are the only oral medications approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat PHN.5

Topical medications can also be used. Lidocaine 5% is favored as first-line therapy for the amelioration of pain due to shingles, as it provides modest pain relief with a better safety and tolerability profile than capsaicin 8% patch, which is a second-line choice. The latter must be applied multiple times daily, has minimal analgesic efficacy, and frequently causes initial pain upon application.

Gabapentinoids and topical analgesics can be used in combination due to the low propensity for drug interactions.6,7 The treatment of choice for focal vasculopathy is intravenous acyclovir, usually for 14 days, although immunocompromised patients should be treated for a longer period of time. Also consider 5 days of steroid therapy for patients with VZV vasculopathy.8

Non-FDA approved treatments include tricyclic antidepressants (TCA), such as amitriptyline, nortriptyline, and desipramine, which are sometimes used as first-line therapy for shingles. TCAs may not work well in patients with burning pain, and can have significant adverse effects, including possible cardiotoxicity.9

Opioids, including oxycodone, morphine, methadone, and tramadol, are sometimes used in pain management, but concern exists for abuse. Because patients may develop physical dependence, use opioids with considerable caution.10

Prevention. The United States became the first country to institute a routine varicella immunization program after a varicella vaccine (Varivax) was licensed in 1995.11 The vaccine has reduced the number of varicella infection cases dramatically.11 Vaccine effectiveness is high, and protective herd immunity is obtained after 2 doses.11-13 The vaccine is administered to children after one year of age with a booster dose administered after the fourth birthday.

A live, attenuated VZV vaccine (Zostavax) is given to individuals ≥60 years of age to prevent or attenuate herpes zoster infection. This vaccine is used to boost VZV-specific cell-mediated immunity in adults, thereby decreasing the burden of herpes zoster and the pain associated with PHN.14

Roseola

Roseola infantum, also known as exanthema subitum and sixth disease, is a common mild acute febrile illness of childhood caused by infection with human herpesvirus (HHV) 6 (the primary agent causing roseola) or 7 (a secondary causal agent for roseola).15 HHV-6 has 2 variants (HHV-6a and HHV-6b). Roseola infantum is mostly associated with the HHV-6b variant, which predominantly affects children 6 to 36 months of age.16

The virus replicates in the salivary glands and is shed through saliva, which is the route of transmission. After a 10- to 15-day incubation period, it remains latent in lymphocytes and monocytes, thus persisting in cells and tissues. It may reactivate late in life, particularly in immunosuppressed individuals. Reactivated infection in immunocompromised patients may be associated with serious illness such as encephalitis/encephalopathy. In patients who have received a bone marrow transplant, it can induce graft vs host disease.17

Presentation. The virus causes a 5- to 6-day illness characterized by high fever (temperature as high as 105°-106° F), miringitis (inflammation of tympanic membranes), and irritability. Once defervescence occurs, an erythematous morbilliform exanthem appears.The rash, which has a discrete macular/papular soft-pink appearance, starts on the trunk and spreads centrifugally to the extremities, neck, and face (FIGURE 2). It usually resolves within one to 2 days.

Complications. The most common complication of roseola is febrile seizures.17 Less common ones include encephalitis, encephalopathy, fatal hemophagocytic syndrome,18 or fulminant hepatitis.19

Treatment and prevention. Treatment depends on symptoms and may include antipyretics for fever management and liquids to maintain hydration. Recovery is usually complete with no significant sequelae. If a child develops a seizure, no antiepileptic drugs are recommended. No vaccine exists.

Fifth disease

Human parvovirus B19, a minute ssDNA virus, was first associated with human disease in 1981, when it was linked to an aplastic crisis in a patient with sickle cell disease.20 Since then researchers have determined that it is also the cause of erythema infectiosum or fifth disease of childhood. The B19 virus can also cause anemia in the fetus as well as hydrops fetalis. It has been linked to arthralgia and arthritis (especially in adults). There is an association with autoimmune diseases with characteristics similar to rheumatoid arthritis.20

The B19 virus is transmitted via aerosolized respiratory secretions, contaminated blood, or the placenta. The virus replicates in erythroid cells in bone marrow and peripheral blood, thus inhibiting erythropoiesis.21 Once the rash appears, the virus is no longer infectious.22 Seasonal peaks occur in the late winter and spring, with sporadic infections throughout the year.23 More than 70% of the adult population is seropositive for this virus.20

Presentation. Erythema infectiosum is a mild illness in childhood with an incubation period of 6 to 18 days. It presents with a characteristic malar rash on the face that gives patients a slapped cheek appearance (FIGURE 3A). A softer pink-colored “lacy” reticulated rash that blanches when touched may appear on the trunk, arms, and legs (FIGURE 3B).

Another presentation, which involves the hands and feet (glove and sock syndrome) (FIGURES 3C and 3D), consists of a purpuric eruption with painful edema and numerous small confluent petechiae.22,24 A majority of patients present with inflammatory symptoms that tend to resolve without sequelae within 3 weeks of infection.23

A rash is not as prevalent in adults as in children. Adults often present with more systemic systems, such as a debilitating influenza-like illness, arthropathy, transient aplastic anemia in sickle cell-affected individuals, and persistent viral suppression of erythrocyte production in immunocompromised patients and organ-transplant recipients.

Complications. The B19 virus can cause spontaneous abortion in pregnant women and anemia and hydrops fetalis in the fetus.22 Arthritis can occur in children, but is more common in adults, especially in women. The arthritis tends to be symmetrical and affects small joints such as the hands, wrists, and knees.

In one study of parvovirus B19 involving 633 children with sickle cell disease, 68 children developed transient red cell aplasia, 19% of them developed splenic sequestration, and 12% developed acute chest syndrome, a lung-related complication of sickle cell disease that can lower the level of oxygen in the blood and can be fatal.25

Treatment and prevention. Treatment of B19 infection is symptomatic; for example, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are used if joint pain develops. No vaccine exists.

Hand, foot, and mouth disease

Hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) is caused by the picornavirus family, including the Coxsackievirus, Enterovirus, and Echovirus. Infections commonly occur in the spring, summer, and fall. The virus primarily affects infants and children <10 years of age with the infection typically lasting 7 to 10 days.26

Presentation. The disease usually presents with a febrile episode, progressing to nasal congestion and malaise. One to 2 days later, the classic rash appears. Patients with HFMD usually present with papular or vesicular lesions on the hands and feet and painful oral lesions (FIGURES 4A, 4B, and 4C). The rash may also affect other parts of the body including the legs and buttocks. Desquamation of nails may occur up to one month after the HFM infection.27 Most cases are diagnosed by clinical presentation, but infection can be confirmed by PCR of vesicular lesion fluid.

Complications. In addition to being caused by Coxsackievirus, HFMD may be caused by human Enterovirus A serotype 71 (HEVA-71), which is associated with a high prevalence of acute neurologic disease including aseptic meningitis, poliomyelitis-like paralysis, and encephalitis.26 Of 764 HFMD patients enrolled in a prospective study, 214 cases were associated with Coxsackievirus A 16 (CVA16) infection and 173 cases were associated with HEVA-71 infection. Rare cases of HFMD have led to encephalitis, meningitis, flaccid paralysis, and death.26

Treatment and prevention. HFMD is usually self-limited, and treatment is supportive. There has been interest in developing an HFMD vaccine, but no products are as yet commercially available.

Rubella

Rubella, also known as the German measles or the 3-day measles, is caused by the rubella virus, which is transmitted via respiratory droplets. Up to half of rubella infections are asymptomatic.28-30

Presentation. Rubella typically has an incubation period of 12 to 24 days, with a 5-day prodromal period characterized by fever, headache, and other symptoms typical of an upper respiratory infection, including sore throat, arthralgia, and tender lymphadenopathy.28

The rash often starts as erythematous or as rose-pink macules on the face that progress down the body. The rash can cover the trunk and extremities within 24 hours. (For photos, see https://www.cdc.gov/rubella/about/photos.html.)

Patients are infectious from 7 days prior to the appearance of the rash to 7 days after resolution of the rash. Given the potentially prolonged infectious period, patients hospitalized for rubella infection should be placed on droplet precautions, and children should be kept from day care and school for 7 days after the appearance of the rash.28

Rubella is typically a mild disease in immunocompetent patients; however, immunocompromised patients may develop pneumonia, coagulopathies, or neurologic sequelae including encephalitis.

Complications. Rubella infection, especially during the first trimester, can lead to spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, or congenital rubella syndrome (CRS), a condition characterized by congenital cataracts and “blueberry muffin” skin lesions.31 Infants affected by CRS can also have heart defects, intellectual disabilities, deafness, and low birth weight. Diagnosis of primary maternal infection should be made with serologic tests. Fetal infection can be determined by detection of fetal serum IgM after 22 to 24 weeks of gestation or with viral culture of amniotic fluid.31

Treatment and prevention. Currently, no antiviral treatments are available; however, vaccines are highly effective at preventing infection. Rubella vaccine is usually given as part of the measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine, which is administered at age 12 to 15 months and again between 4 and 6 years of age.

Measles

Measles is a highly contagious disease caused by a virus that belongs to the Morbillivirus genus of the family Paramyxoviridae. Infection occurs through inhalation of, or direct contact with, respiratory droplets from infected people.32

Presentation. People with measles often present with what starts as a macular rash on the face that then spreads downward to the neck, trunk, and extremities (for photos, see http://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/index.html). As the disease progresses, papules can develop and the lesions may coalesce.

The rash is often preceded by 3 to 4 days of malaise and fever (temperature often greater than 104° F), along with the classic symptom triad of cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis. Koplik spots—clustered white lesions on the buccal mucosa—are often present prior to the measles rash and are pathognomonic for measles infection.33

Because the symptoms of measles are easily confused with other viral infections, suspected cases of measles should be confirmed via IgG and IgM antibody tests, by reverse transcription-PCR, or both.34,35 For limited and unusual cases, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention can perform a plaque reduction neutralization assay.35

Complications. Measles infection is self-limited in immunocompetent patients. The most common complications are diarrhea and ear infections, but more serious complications, such as pneumonia, hearing loss, and encephalitis, can occur. Children <2 years of age, particularly boys, are at an increased risk of developing subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, a fatal neurologic disorder that can develop years after the initial measles infection.33,36

Treatment and prevention. Treatment is supportive and usually consists of acetaminophen or NSAIDs and fluids.

A live attenuated version of the measles vaccine is highly effective against the measles virus and has greatly reduced the number of measles cases globally.37 The measles vaccine is usually given in 2 doses—the first one after one year of age, and the second one before entering kindergarten. The most common adverse reactions to the vaccine are pain at the injection site and fever. Despite the fact that the MMR vaccine is effective and relatively benign, measles outbreaks continue to occur, as some parents forego routine childhood immunizations because of religious or other personal beliefs or safety concerns.38

Molluscum contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is caused by the MC virus, a member of the poxvirus family. The virus is transmitted by direct contact with the skin lesions. This skin condition is seen mainly in children, although it can occur in adults.

A study conducted in England and Wales that obtained information from the Royal College of General Practitioners reported an incidence of 15.0-17.2/1000 population over a 10-year period (1994-2003) with no variation between sexes.39 There is an association between atopic dermatitis and MC; 24% of children with atopic dermatitis develop MC.40 There might also be an association between recent swimming in a public pool and development of MC lesions.41

Presentation. Lesions caused by MC are small, discrete, waxy dome-shaped papules with central umbilication that are usually 3 to 5 mm in diameter (FIGURE 5).42,43 In immunocompetent patients, there are usually fewer than 20 lesions, which resolve within a year. However, in immunocompromised patients, the number of lesions is usually higher, and the diameter of each may be greater than 1 cm.42

Complications. The lesions are usually self-limited, but on occasion can become secondarily infected, usually with gram-positive organisms such as Staphylococcus aureus. Very rarely, abscesses develop requiring topical and/or systemic antimicrobials and perhaps incision and drainage.44

Treatment and prevention. Because the infection is often self-limited and benign, the preferred therapeutic modality is watchful waiting. Other treatments for MC include curettage, chemical agents, immune modulators, and antiviral drugs. A 2009 Cochran review of 11 studies involving 495 patients found “no single intervention to be convincingly effective in the treatment of molluscum contagiosum.”45 And no vaccine exists.

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome (GCS), also known as papular acrodermatitis of childhood, is a relatively rare, self-limited exanthema that usually affects infants and children 6 months to 12 years of age (peak occurrence is in one- to 6-year-olds). Although there have been reports of adults with this syndrome, it is unusual in this age group.

Pathogenesis is still unknown. Although GCS itself isn’t contagious, the viruses that can cause it may be. Initially, researchers believed that GCS was linked to acute hepatitis B virus infection, but more recently other viral and bacterial infections have been associated with the condition.46

The most commonly associated virus in the United States is Epstein-Barr virus; other viruses include hepatitis A virus, cytomegalovirus, coxsackievirus, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza virus, rotavirus, the mumps virus, parvovirus, and molluscum contagiosum.

Bacterial infections, such as those caused by Bartonella henselae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and group A streptococci may trigger GCS.47-49

Vaccines that have been implicated in GCS include those for polio, diphtheria/pertussis/tetanus, MMR, hepatitis A and B, as well as the influenza vaccine.48-51

Presentation. While GCS is relatively rare, its presentation is classic, making it easy to diagnose once it’s included in the differential. The pruritic rash usually consists of acute-onset monomorphous, flat-topped or dome-shaped red-brown papules and papulovesicles, one to 10 mm in size, located symmetrically on the face (FIGURE 6), the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs, and, less commonly, the buttocks. It rarely affects other parts of the body.48

The diagnosis is usually based on the characteristic rash and the benign nature of the condition; other than the rash, patients are typically asymptomatic and healthy. Sometimes a biopsy is performed and it reveals a dense lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with a strong cytoplasmic immunopositivity for beta-defensin-4 in the stratum corneum, granulosum, and spinosum.52

The lesions spontaneously resolve within 8 to 12 weeks. GCS usually presents during spring and early summer and affects both sexes equally.46

Treatment and prevention. Treatment is usually symptomatic, with the use of oral antihistamines if the lesions become pruritic. Topical steroids may be used, and, in a few cases, oral corticosteroids may be considered. No vaccine exists.

CORRESPONDENCE

Carlos A. Arango, MD, 8399 Bayberry Road, Jacksonville, FL 32256; carlos.arango@jax.ufl.edu.

Family physicians encounter skin rashes on a daily basis. First steps in making the diagnosis include identifying the characteristics of the rash and determining whether the eruption is accompanied by fever or any other symptoms. In the article that follows, we review 8 viral exanthems of childhood that range from the common (chickenpox) to the not-so-common (Gianotti-Crosti syndrome).

Varicella-zoster virus

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is a human neurotropic alphaherpesvirus that causes a primary infection commonly known as chickenpox (varicella).1 This disease is usually mild and resolves spontaneously.

This highly contagious virus is transmitted by directly touching the blisters, saliva, or mucus of an infected person. It is also transmitted through the air by coughing and sneezing. VZV initiates primary infection by inoculating the respiratory mucosa. It then establishes a lifelong presence in the sensory ganglionic neurons and, thus, can reactivate later in life causing herpes zoster (shingles), which can affect cranial, thoracic, and lumbosacral dermatomes. Acute or chronic neurologic disorders, including cranial nerve palsies, zoster paresis, vasculopathy, meningoencephalitis, and multiple ocular disorders, have been reported after VZV reactivation resulting in herpes-zoster.1

Presentation. With varicella, an extremely pruritic rash follows a brief prodromal stage consisting of a low-grade fever, upper respiratory tract symptoms, tiredness, and fatigue. This exanthem develops rapidly, often beginning on the chest, trunk, or scalp and then spreading to the arms and legs (centrifugally) (FIGURE 1). Varicella also affects mucosal areas of the body, such as the conjunctiva, mouth, rectum, and vagina.

The lesions are papules that rapidly become vesicular with clear fluid inside. Subsequently, the lesions begin to crust. Scabbing occurs within 10 to 14 days. A sure sign of chickenpox is the presence of papules, vesicles, and crusting lesions in close proximity.

Complications. The most common complications of chickenpox—especially in children—are invasive streptococcal and staphylococcal infections.2 The most serious complication occurs when the virus invades the spinal cord, causing myelitis or affecting the cerebral arteries, leading to vasculopathy. Diagnosis of VZV in the central nervous system is based on isolation of the virus in cerebral spinal fluid by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Early diagnosis is important to minimize morbidity and mortality.

Reactivation is sometimes associated with post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN), a severe neuropathic pain syndrome isolated to the dermatomes affected by VZV. PHN can cause pain and suffering for years after shingles resolves, and sometimes is refractory to treatment. PHN may reflect a chronic varicella virus ganglionitis.

A number of treatment choices exist for shingles, but not so much for varicella

Oral treatment. Oral medications such as acyclovir and its prodrug valacyclovir are the current gold standards for the treatment of VZV.3

Famciclovir, the prodrug of penciclovir, is more effective than valacyclovir at resolving acute herpes zoster rash and shortening the duration of PHN.4 Gabapentinoids (eg, pregabalin) are the only oral medications approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat PHN.5

Topical medications can also be used. Lidocaine 5% is favored as first-line therapy for the amelioration of pain due to shingles, as it provides modest pain relief with a better safety and tolerability profile than capsaicin 8% patch, which is a second-line choice. The latter must be applied multiple times daily, has minimal analgesic efficacy, and frequently causes initial pain upon application.

Gabapentinoids and topical analgesics can be used in combination due to the low propensity for drug interactions.6,7 The treatment of choice for focal vasculopathy is intravenous acyclovir, usually for 14 days, although immunocompromised patients should be treated for a longer period of time. Also consider 5 days of steroid therapy for patients with VZV vasculopathy.8

Non-FDA approved treatments include tricyclic antidepressants (TCA), such as amitriptyline, nortriptyline, and desipramine, which are sometimes used as first-line therapy for shingles. TCAs may not work well in patients with burning pain, and can have significant adverse effects, including possible cardiotoxicity.9

Opioids, including oxycodone, morphine, methadone, and tramadol, are sometimes used in pain management, but concern exists for abuse. Because patients may develop physical dependence, use opioids with considerable caution.10

Prevention. The United States became the first country to institute a routine varicella immunization program after a varicella vaccine (Varivax) was licensed in 1995.11 The vaccine has reduced the number of varicella infection cases dramatically.11 Vaccine effectiveness is high, and protective herd immunity is obtained after 2 doses.11-13 The vaccine is administered to children after one year of age with a booster dose administered after the fourth birthday.

A live, attenuated VZV vaccine (Zostavax) is given to individuals ≥60 years of age to prevent or attenuate herpes zoster infection. This vaccine is used to boost VZV-specific cell-mediated immunity in adults, thereby decreasing the burden of herpes zoster and the pain associated with PHN.14

Roseola

Roseola infantum, also known as exanthema subitum and sixth disease, is a common mild acute febrile illness of childhood caused by infection with human herpesvirus (HHV) 6 (the primary agent causing roseola) or 7 (a secondary causal agent for roseola).15 HHV-6 has 2 variants (HHV-6a and HHV-6b). Roseola infantum is mostly associated with the HHV-6b variant, which predominantly affects children 6 to 36 months of age.16

The virus replicates in the salivary glands and is shed through saliva, which is the route of transmission. After a 10- to 15-day incubation period, it remains latent in lymphocytes and monocytes, thus persisting in cells and tissues. It may reactivate late in life, particularly in immunosuppressed individuals. Reactivated infection in immunocompromised patients may be associated with serious illness such as encephalitis/encephalopathy. In patients who have received a bone marrow transplant, it can induce graft vs host disease.17

Presentation. The virus causes a 5- to 6-day illness characterized by high fever (temperature as high as 105°-106° F), miringitis (inflammation of tympanic membranes), and irritability. Once defervescence occurs, an erythematous morbilliform exanthem appears.The rash, which has a discrete macular/papular soft-pink appearance, starts on the trunk and spreads centrifugally to the extremities, neck, and face (FIGURE 2). It usually resolves within one to 2 days.

Complications. The most common complication of roseola is febrile seizures.17 Less common ones include encephalitis, encephalopathy, fatal hemophagocytic syndrome,18 or fulminant hepatitis.19

Treatment and prevention. Treatment depends on symptoms and may include antipyretics for fever management and liquids to maintain hydration. Recovery is usually complete with no significant sequelae. If a child develops a seizure, no antiepileptic drugs are recommended. No vaccine exists.

Fifth disease

Human parvovirus B19, a minute ssDNA virus, was first associated with human disease in 1981, when it was linked to an aplastic crisis in a patient with sickle cell disease.20 Since then researchers have determined that it is also the cause of erythema infectiosum or fifth disease of childhood. The B19 virus can also cause anemia in the fetus as well as hydrops fetalis. It has been linked to arthralgia and arthritis (especially in adults). There is an association with autoimmune diseases with characteristics similar to rheumatoid arthritis.20

The B19 virus is transmitted via aerosolized respiratory secretions, contaminated blood, or the placenta. The virus replicates in erythroid cells in bone marrow and peripheral blood, thus inhibiting erythropoiesis.21 Once the rash appears, the virus is no longer infectious.22 Seasonal peaks occur in the late winter and spring, with sporadic infections throughout the year.23 More than 70% of the adult population is seropositive for this virus.20

Presentation. Erythema infectiosum is a mild illness in childhood with an incubation period of 6 to 18 days. It presents with a characteristic malar rash on the face that gives patients a slapped cheek appearance (FIGURE 3A). A softer pink-colored “lacy” reticulated rash that blanches when touched may appear on the trunk, arms, and legs (FIGURE 3B).

Another presentation, which involves the hands and feet (glove and sock syndrome) (FIGURES 3C and 3D), consists of a purpuric eruption with painful edema and numerous small confluent petechiae.22,24 A majority of patients present with inflammatory symptoms that tend to resolve without sequelae within 3 weeks of infection.23

A rash is not as prevalent in adults as in children. Adults often present with more systemic systems, such as a debilitating influenza-like illness, arthropathy, transient aplastic anemia in sickle cell-affected individuals, and persistent viral suppression of erythrocyte production in immunocompromised patients and organ-transplant recipients.

Complications. The B19 virus can cause spontaneous abortion in pregnant women and anemia and hydrops fetalis in the fetus.22 Arthritis can occur in children, but is more common in adults, especially in women. The arthritis tends to be symmetrical and affects small joints such as the hands, wrists, and knees.

In one study of parvovirus B19 involving 633 children with sickle cell disease, 68 children developed transient red cell aplasia, 19% of them developed splenic sequestration, and 12% developed acute chest syndrome, a lung-related complication of sickle cell disease that can lower the level of oxygen in the blood and can be fatal.25

Treatment and prevention. Treatment of B19 infection is symptomatic; for example, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are used if joint pain develops. No vaccine exists.

Hand, foot, and mouth disease

Hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) is caused by the picornavirus family, including the Coxsackievirus, Enterovirus, and Echovirus. Infections commonly occur in the spring, summer, and fall. The virus primarily affects infants and children <10 years of age with the infection typically lasting 7 to 10 days.26

Presentation. The disease usually presents with a febrile episode, progressing to nasal congestion and malaise. One to 2 days later, the classic rash appears. Patients with HFMD usually present with papular or vesicular lesions on the hands and feet and painful oral lesions (FIGURES 4A, 4B, and 4C). The rash may also affect other parts of the body including the legs and buttocks. Desquamation of nails may occur up to one month after the HFM infection.27 Most cases are diagnosed by clinical presentation, but infection can be confirmed by PCR of vesicular lesion fluid.

Complications. In addition to being caused by Coxsackievirus, HFMD may be caused by human Enterovirus A serotype 71 (HEVA-71), which is associated with a high prevalence of acute neurologic disease including aseptic meningitis, poliomyelitis-like paralysis, and encephalitis.26 Of 764 HFMD patients enrolled in a prospective study, 214 cases were associated with Coxsackievirus A 16 (CVA16) infection and 173 cases were associated with HEVA-71 infection. Rare cases of HFMD have led to encephalitis, meningitis, flaccid paralysis, and death.26

Treatment and prevention. HFMD is usually self-limited, and treatment is supportive. There has been interest in developing an HFMD vaccine, but no products are as yet commercially available.

Rubella

Rubella, also known as the German measles or the 3-day measles, is caused by the rubella virus, which is transmitted via respiratory droplets. Up to half of rubella infections are asymptomatic.28-30

Presentation. Rubella typically has an incubation period of 12 to 24 days, with a 5-day prodromal period characterized by fever, headache, and other symptoms typical of an upper respiratory infection, including sore throat, arthralgia, and tender lymphadenopathy.28

The rash often starts as erythematous or as rose-pink macules on the face that progress down the body. The rash can cover the trunk and extremities within 24 hours. (For photos, see https://www.cdc.gov/rubella/about/photos.html.)

Patients are infectious from 7 days prior to the appearance of the rash to 7 days after resolution of the rash. Given the potentially prolonged infectious period, patients hospitalized for rubella infection should be placed on droplet precautions, and children should be kept from day care and school for 7 days after the appearance of the rash.28

Rubella is typically a mild disease in immunocompetent patients; however, immunocompromised patients may develop pneumonia, coagulopathies, or neurologic sequelae including encephalitis.

Complications. Rubella infection, especially during the first trimester, can lead to spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, or congenital rubella syndrome (CRS), a condition characterized by congenital cataracts and “blueberry muffin” skin lesions.31 Infants affected by CRS can also have heart defects, intellectual disabilities, deafness, and low birth weight. Diagnosis of primary maternal infection should be made with serologic tests. Fetal infection can be determined by detection of fetal serum IgM after 22 to 24 weeks of gestation or with viral culture of amniotic fluid.31

Treatment and prevention. Currently, no antiviral treatments are available; however, vaccines are highly effective at preventing infection. Rubella vaccine is usually given as part of the measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine, which is administered at age 12 to 15 months and again between 4 and 6 years of age.

Measles

Measles is a highly contagious disease caused by a virus that belongs to the Morbillivirus genus of the family Paramyxoviridae. Infection occurs through inhalation of, or direct contact with, respiratory droplets from infected people.32

Presentation. People with measles often present with what starts as a macular rash on the face that then spreads downward to the neck, trunk, and extremities (for photos, see http://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/index.html). As the disease progresses, papules can develop and the lesions may coalesce.

The rash is often preceded by 3 to 4 days of malaise and fever (temperature often greater than 104° F), along with the classic symptom triad of cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis. Koplik spots—clustered white lesions on the buccal mucosa—are often present prior to the measles rash and are pathognomonic for measles infection.33

Because the symptoms of measles are easily confused with other viral infections, suspected cases of measles should be confirmed via IgG and IgM antibody tests, by reverse transcription-PCR, or both.34,35 For limited and unusual cases, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention can perform a plaque reduction neutralization assay.35

Complications. Measles infection is self-limited in immunocompetent patients. The most common complications are diarrhea and ear infections, but more serious complications, such as pneumonia, hearing loss, and encephalitis, can occur. Children <2 years of age, particularly boys, are at an increased risk of developing subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, a fatal neurologic disorder that can develop years after the initial measles infection.33,36

Treatment and prevention. Treatment is supportive and usually consists of acetaminophen or NSAIDs and fluids.

A live attenuated version of the measles vaccine is highly effective against the measles virus and has greatly reduced the number of measles cases globally.37 The measles vaccine is usually given in 2 doses—the first one after one year of age, and the second one before entering kindergarten. The most common adverse reactions to the vaccine are pain at the injection site and fever. Despite the fact that the MMR vaccine is effective and relatively benign, measles outbreaks continue to occur, as some parents forego routine childhood immunizations because of religious or other personal beliefs or safety concerns.38

Molluscum contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is caused by the MC virus, a member of the poxvirus family. The virus is transmitted by direct contact with the skin lesions. This skin condition is seen mainly in children, although it can occur in adults.

A study conducted in England and Wales that obtained information from the Royal College of General Practitioners reported an incidence of 15.0-17.2/1000 population over a 10-year period (1994-2003) with no variation between sexes.39 There is an association between atopic dermatitis and MC; 24% of children with atopic dermatitis develop MC.40 There might also be an association between recent swimming in a public pool and development of MC lesions.41

Presentation. Lesions caused by MC are small, discrete, waxy dome-shaped papules with central umbilication that are usually 3 to 5 mm in diameter (FIGURE 5).42,43 In immunocompetent patients, there are usually fewer than 20 lesions, which resolve within a year. However, in immunocompromised patients, the number of lesions is usually higher, and the diameter of each may be greater than 1 cm.42

Complications. The lesions are usually self-limited, but on occasion can become secondarily infected, usually with gram-positive organisms such as Staphylococcus aureus. Very rarely, abscesses develop requiring topical and/or systemic antimicrobials and perhaps incision and drainage.44

Treatment and prevention. Because the infection is often self-limited and benign, the preferred therapeutic modality is watchful waiting. Other treatments for MC include curettage, chemical agents, immune modulators, and antiviral drugs. A 2009 Cochran review of 11 studies involving 495 patients found “no single intervention to be convincingly effective in the treatment of molluscum contagiosum.”45 And no vaccine exists.

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome

Gianotti-Crosti syndrome (GCS), also known as papular acrodermatitis of childhood, is a relatively rare, self-limited exanthema that usually affects infants and children 6 months to 12 years of age (peak occurrence is in one- to 6-year-olds). Although there have been reports of adults with this syndrome, it is unusual in this age group.

Pathogenesis is still unknown. Although GCS itself isn’t contagious, the viruses that can cause it may be. Initially, researchers believed that GCS was linked to acute hepatitis B virus infection, but more recently other viral and bacterial infections have been associated with the condition.46

The most commonly associated virus in the United States is Epstein-Barr virus; other viruses include hepatitis A virus, cytomegalovirus, coxsackievirus, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza virus, rotavirus, the mumps virus, parvovirus, and molluscum contagiosum.

Bacterial infections, such as those caused by Bartonella henselae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and group A streptococci may trigger GCS.47-49

Vaccines that have been implicated in GCS include those for polio, diphtheria/pertussis/tetanus, MMR, hepatitis A and B, as well as the influenza vaccine.48-51

Presentation. While GCS is relatively rare, its presentation is classic, making it easy to diagnose once it’s included in the differential. The pruritic rash usually consists of acute-onset monomorphous, flat-topped or dome-shaped red-brown papules and papulovesicles, one to 10 mm in size, located symmetrically on the face (FIGURE 6), the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs, and, less commonly, the buttocks. It rarely affects other parts of the body.48

The diagnosis is usually based on the characteristic rash and the benign nature of the condition; other than the rash, patients are typically asymptomatic and healthy. Sometimes a biopsy is performed and it reveals a dense lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with a strong cytoplasmic immunopositivity for beta-defensin-4 in the stratum corneum, granulosum, and spinosum.52

The lesions spontaneously resolve within 8 to 12 weeks. GCS usually presents during spring and early summer and affects both sexes equally.46

Treatment and prevention. Treatment is usually symptomatic, with the use of oral antihistamines if the lesions become pruritic. Topical steroids may be used, and, in a few cases, oral corticosteroids may be considered. No vaccine exists.

CORRESPONDENCE

Carlos A. Arango, MD, 8399 Bayberry Road, Jacksonville, FL 32256; carlos.arango@jax.ufl.edu.

1. Kennedy PG, Rovnak J, Badani H, et al. A comparison of herpes simplex virus type 1 and varicella-zoster virus latency and reactivation. J Gen Virol. 2015;96(Pt 7):1581-1602.

2. Blumental S, Sabbe M, Lepage P, the Belgian Group for Varicella. Varicella paediatric hospitalisations in Belgium: a 1-year national survey. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101:16-22.

3. Sampathkumar P, Drage LA, Martin DP. Herpes zoster (shingles) and postherpetic neuralgia. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2009;84:274-280.

4. Ono F, Yasumoto S, Furumura M, et al. Comparison between famciclovir and valacyclovir for acute pain in adult Japanese immunocompetent patients with herpes zoster. J Dermatol. 2012;39:902-908.

5. Massengill JS, Kittredge JL. Practical considerations in the pharmacological treatment of post-herpetic neuralgia for the primary care provider. J Pain Res. 2014;7:125-132.

6. Nalamachu S, Morley-Forster P. Diagnosing and managing postherpetic neuralgia. Drugs & Aging. 2012;29:863-869.

7. Hempenstall K, Nurmikko TJ, Johnson RW, et al. Analgesic therapy in postherpetic neuralgia: a quantitative systematic review. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e164.

8. Gilden D, Cohrs RJ, Mahalingam R, et al. Varicella zoster virus vasculopathies: diverse clinical manifestations, laboratory features, pathogenesis, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2009;9:731-740.

9. Stankus SJ, Dlugopolski M, Packer D. Management of herpes zoster (shingles) and post herpetic neuralgia. Am Fam Physician. 2000;61:2437-2444.

10. Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Audette J, et al. Recommendations for the pharmacological management of neuropathic pain: an overview and literature update. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(3 Suppl):S3-S14.

11. Thomas CA, Shwe T, Bixler D, et al. Two-dose varicella vaccine effectiveness and rash severity in outbreaks of varicella among public school students. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33:1164-1168.

12. Helmuth IG, Poulsen A, Suppli CH, et al. Varicella in Europe-a review of the epidemiology and experience with vaccination. Vaccine. 2015;33:2406-2413.

13. Marin M, Marti M, Kambhampati A, et al. Global varicella vaccine effectiveness: a metanalysis. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e20153741.

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What everyone should know about shingles vaccine. Available at: www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/shingles/public/index.html. Accessed September 12, 2017.

15. Tanaka K, Kondo T, Torigoe S, et al. Human herpesvirus 7: another causal agent for roseola (exanthem subitum). J Pediatr. 1994;125:1-5.

16. Caserta MT, Mock DJ, Dewhurst S. Human herpesvirus 6. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:829-833.

17. Koch WC. Fifth (human parvovirus) and sixth (herpesvirus 6) diseases. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2001;14:343-356.

18. Marabelle A, Bergeron C, Billaud G, et al. Hemophagocytic syndrome revealing primary HHV-6 infection. J Pediatr. 2010;157:511.

19. Charnot-Katsikasa A, Baewer D, Cook L, et al. Fulminant hepatic failure attributed to infection with human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) in an immunocompetent woman: a case report and review of the literature. J Clin Virol. 2016;75:27-32.

20. Corcoran A, Doyle S. Advances in the biology, diagnosis and host-pathogen interactions of parvovirus B19. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53(Pt 6):459-475.

21. Dolin R. Parvovirus erythema infectiousum, Aplastic anemia. In: Mandell, Douglas, Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone Inc; 1990:1231-1232.

22. Servey JT, Reamy BV, Hodge J. Clinical presentations of parvovirus B19 infection. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75:373-376.

23. Martin DR, Schlott DW, Flynn JA. Clinical problem-solving. No respecter of age. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1856-1859.

24. Ozaydin V, Eceviz A, Sari Dogan F, et al. An adult patient who presented to emergency service with a papular purpuric gloves and socks syndrome: a case report. Turk J Emerg Med. 2014;14:179-181.

25. Smith-Whitley K, Zhao H, Hodinka RL, et al. Epidemiology of human parvovirus B19 in children with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2004;103:422-427.

26. Tu PV, Thao NT, Perera D, et al. Epidemiologic and virologic investigation of hand, foot, and mouth disease, Southern Vietnam, 2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1733-1741.

27. Ferrari B, Taliercio V, Hornos L, et al. Onychomadesis associated with mouth, hand and foot disease. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2013;111:e148-e151.

28. Alter SJ, Bennett JS, Koranyi K, et al. Common childhood viral infections. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2015;45:21-53.

29. Lambert N, Strebel P, Orenstein W, et al. Rubella. Lancet. 2015;385:2297-2307.

30. Silasi M, Cardenas I, Kwon JY, et al. Viral infections during pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2015;73:199-213.

31. Tang JW, Aarons E, Hesketh LM, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital rubella infection in the second trimester of pregnancy Prenat Diagn. 2003;23:509-512.

32. Naim HY. Measles virus. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11:21-26.

33. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles (Rubeola). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/index.html. Accessed April 28, 2016.

34. Takao S, Shigemoto N, Shimazu Y, et al. Detection of exanthematic viruses using a TaqMan real-time PCR assay panel in patients with clinically diagnosed or suspected measles. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2012;65:444-448.

35. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles (Rubeola). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/measles/lab-tools/rt-pcr.html. Accessed April 28, 2016.

36. Griffin DE, Lin WH, Pan CH. Measles virus, immune control, and persistence. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2012;36:649-662.

37. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles, vaccination. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/measles/vaccination.html. Accessed April 28, 2016.

38. Campos-Outcalt D. Measles: Why it’s still a threat. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:446-449.

39. Olsen JR, Gallacher J, Piguet V, et al. Epidemiology of molluscum contagiosum in children: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2014;31:130-136.

40. Dohil MA, Lin P, Lee J, et al. The epidemiology of molluscum contagiosum in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:47-54.

41. Choong KY, Roberts LJ. Molluscum contagiosum, swimming and bathing: a clinical analysis. Australas J Dermatol. 1999;40:89-92.

42. Martin P. Interventions for molluscum contagiosum in people infected with human immunodeficiency virus: a systematic review. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:956-966.

43. Chen X, Anstey AV, Bugert JJ. Molluscum contagiosum virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:877-888.

44. Lacour M, Posfay-Barbe KM, La Scala GC. Staphylococcus lugdunensis abscesses complicating molluscum contagiosum in two children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:289-291.

45. van der Wouden JC, van der Sande R, van Suijlekom-Smit LW, et al. Interventions for cutaneous molluscum contagiosum. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;CD004767.

46. Tagawa C, Speakman M. Photo quiz. Papular rash in a child after a fever. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:59-60.

47. Brandt O, Abeck D, Gianotti R, et al. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:136-145.

48. Retrouvey M, Koch LH, Williams JV. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome following childhood vaccinations. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:137-138.

49. Velangi SS, Tidman MJ. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome after measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:1122-1123.

50. Lacour M, Harms M. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome as a result of vaccination and Epstein-Barr virus infection. Eur J Pediatr. 1995;154:688-689.

51. Kroeskop A, Lewis AB, Barril FA, et al. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome after H1N1-influenza vaccine. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28:595-596.

52. Caltabiano R, Vecchio GM, De Pasquale R, et al. Human beta-defensin 4 expression in Gianotti-Crosti. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2013;21:43-47.

1. Kennedy PG, Rovnak J, Badani H, et al. A comparison of herpes simplex virus type 1 and varicella-zoster virus latency and reactivation. J Gen Virol. 2015;96(Pt 7):1581-1602.

2. Blumental S, Sabbe M, Lepage P, the Belgian Group for Varicella. Varicella paediatric hospitalisations in Belgium: a 1-year national survey. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101:16-22.

3. Sampathkumar P, Drage LA, Martin DP. Herpes zoster (shingles) and postherpetic neuralgia. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2009;84:274-280.

4. Ono F, Yasumoto S, Furumura M, et al. Comparison between famciclovir and valacyclovir for acute pain in adult Japanese immunocompetent patients with herpes zoster. J Dermatol. 2012;39:902-908.