User login

Navigating the postsecondary educational pathway can be an intimidating process for post-9/11 veterans struggling with mental health concerns that may alter learning styles and negatively impact performance.1-4 When significant interference with learning ability is anticipated for more than 6 months, these veterans may qualify for formal academic “reasonable” accommodations under federal disability laws that include the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 as amended in 2008 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. These accommodations enable students to compensate for learning disabilities and help support the transition to student life. Student veterans often are not aware of the existence of academic reasonable accommodations, because military separation classes, civilian postdeployment orientation, and popular media do not routinely cover information on this subject.

With an overall objective to ease veteran reintegration into the civilian world and promote emotional stability, health care providers (HCPs) are in a unique position to promote the use of formal academic accommodations for post-9/11 veterans with psychiatric conditions. However, HCPs must have basic information regarding these interventions before initiating discussions with patients. Current peer-reviewed medical literature has scant information regarding specific aspects of academic reasonable accommodations for individuals with psychiatric diagnoses.

The purpose of this 2-part article (part 2 will be published in May 2016) is to promote a greater understanding of academic accommodations for post-9/11 veterans with psychiatric diagnoses. Part 1 provides a brief background regarding issues pertinent to the post-9/11 student veteran role transition and reviews information regarding various aspects of academic reasonable accommodations, including details on the definition, request process, medical documentation requirements, and common accommodation examples.

Although the focus of the article is on the characteristics of post-9/11 veterans who have separated from military service, it also is relevant for providers involved with service members who have not yet separated. The impact of mental health issues, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and psychosocial stressors on learning ability are potentially applicable to many post-9/11 active-duty soldiers and reservists who are pursuing a secondary education. The academic reasonable accommodations discussed are available to any adult who meets the eligibility criteria—regardless of military status.

Influence of Psychiatric Symptoms on Learning

Although each mental health diagnosis is unique, mental health conditions involving mood share the common symptoms of impaired learning ability.3-8 Problems frequently experienced include decreased concentration, shortened attention span, difficulty in making new memories or storing new information, and the inability to recall information previously learned.6-8 Other reported conditions include difficulty with prioritization of tasks, losing track of time, difficulty focusing on tasks, and taking longer to complete assignments.3,4 Increased irritability accompanies many of these issues. Low tolerance to frustration may occur as evidenced by an outburst of anger or resignation to defeat when minor barriers are encountered, especially when authority figures or bureaucratic rules create those perceived barriers.3,4 Persistent impaired ability to articulate ideas or thoughts and difficulty performing abstract thinking also are often noticed when moderate-to-severe mental health symptoms are present.4,8

Medications commonly used to control psychiatric symptoms and stabilize underlying mental health also can produce adverse effects (AEs) that impact learning ability.9,10 Drug AEs vary but often include significant fatigue, impaired memory, and impaired executive function involving insight, judgment, and/or abstract thinking. Depending on the medication, the individual may experience restlessness or insomnia.

Factors Complicating Successful Integration

The transition period from military service to civilian life presents unique complications for student veterans with symptomatic psychiatric concerns.1,11 Veterans who separate from military service go through a civilian transition period of variable intensity influenced by readjustment difficulties and comorbid conditions.11,12 During this time, veterans are reintegrating into civilian life and assuming new roles that include partner, parent, employee, and family member. This transition can cause many symptoms to appear that potentially influence learning to varying degrees. A summary of impediments to learning in post-9/11 veterans is found in Table 1.

Common transition symptoms include irritability, decreased ability to store and recall information, decreased concentration, decreased attention, and slowed executive functioning.13,14 Sleep disturbances such as altered sleep-wake cycles, nonrestful sleep, inadequate sleep, and nightmares also may occur.13,14 Veterans experiencing these transition period symptoms may face significant difficulties with time management skills, organization, and task execution. If the veteran successfully assimilates into his or her new roles and becomes self-confident within those roles, the symptoms may abate. However, if moderate-to-severe psychiatric symptoms also are present, all transition symptoms likely will have an unpredictable time frame for resolution.3,13,14

Understanding the role responsibilities of student veterans is important in recognizing the added stressors veterans with psychiatric diagnoses have within the academic setting. In general, demographic data indicate that student veterans lead far more complex lives than those of 18- to 22-year-olds who enter postsecondary education without military experience. Student veterans are older, have a broader life experience, and may feel less connected to nonveteran students.15,16 Compared with typical younger college students, undergraduate student veterans are more likely to be married but somewhat less likely to be parents.17 Student veterans who are pursuing graduate degrees are more likely to be married and/or have dependents.17 Those roles imply that student veterans often are juggling multiple responsibilities that are constantly competing for student veterans’ time and attention.

Age differences, multiple roles, and lack of shared life experiences with traditional college students contribute to student veterans’ perceptions of a paucity of campus social support and often lead to a sense of distinct isolation.18,19 These added stressors deplete a veteran’s ability to concentrate on academic studies and may exacerbate the effects of underlying mental health diagnoses, transition issues, and medication use.

Symptomatic psychiatric diagnoses can amplify the difficulties normally experienced when changing from a veteran role to a student veteran role.1 The student veteran’s apprehension about returning to school often is elevated because of the time gap since the veteran was last in a formal, nonmilitary classroom. Acclimated to the structured style of military coursework for many years, student veterans may find adjusting to new teaching styles or different academic expectations awkward.20,21 They may experience heightened anxiety, because expectations of classroom performance may not be as clearcut as it was in the military. Such heightened anxiety can compound learning difficulties caused by underlying emotional states, transition issues, medication AEs, and life stressors.

Related: The VA/DoD Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium: An Overview at Year 1

Many student veterans with impaired learning ability related to psychiatric symptoms also have secondary physical diagnoses that can impede learning. For example, tinnitus and hearing loss are common in combat veterans.22,23 These issues make it hard to participate in a classroom setting because of difficulty in recognizing speech or filtering out background noise. For some, chronic pain may impede concentration, depress mood, worsen irritability, and make prolonged sitting difficult.24,25 Physical disabilities related to amputation or major joint injury may present challenges to participating in certain types of college settings and/or navigating between classes in a timely fashion.26

Although mild-to-moderate TBI sustained in combat often will spontaneously resolve within 3 months, in some individuals, TBI symptoms may persist after months or years.27,28 During this time, learning styles may be altered for veterans exposed to TBI. Similar to the effects caused by other factors impeding learning in post-9/11 veterans, common post-TBI symptoms that reduce academic performance include fatigue, decreased memory, slowed abstract thinking, difficulty articulating thoughts, poor tolerance to frustration, sleep difficulties, chronic pain, and increased irritability.27-29 Veterans with a history of mild TBI often are found to have clinically significant rates of depression, anxiety, or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).27,28,30,31 These findings mirror those found in the general population.32 Mild TBI and PTSD may further complicate the learning process by exacerbating underlying mental health symptoms that already impair academic performance. The degree to which these individuals with TBI and mental health issues will return to premorbid academic functioning is not predictable based on current literature.33

Recognizing the stressors that some combat veterans face in an academic setting is vital to anticipating the added support that is needed by student veterans with concurrent moderate-to-severe psychiatric issues.34 Symptoms usually noted in the transition period may be much more pronounced. Automatic behaviors developed as survival responses during deployment can complicate participation in the educational arena.4,35 Seemingly mundane tasks, such as the daily school commute, can cause significant anxiety and hypervigilance especially when the veterans must navigate crowds and traffic formerly associated with risk of attack in combat-related circumstances.4 Minor roadway debris or roadside construction also can abnormally heighten anxiety because of reflex training to avoid potentially hidden explosive devices during convoy movements.4 Random assignment of a classroom seat can be stress-provoking, because combat veterans’ training compels them to position themselves with the greatest vantage point, usually nearest to exits and with minimal activity behind them.4,35 A need to constantly survey the surroundings for potential cover from hostile events can cause hyper alertness that distracts the student veteran’s full concentration on academic tasks.3,4

Although veterans should be able to adjust learning styles for minor issues or transitory problems, significant psychiatric symptoms have a negative effect on learning and pose a direct threat to academic performance.33,36-38 Moderate-to-severe psychiatric concerns may further heighten transition symptoms, compound psychosocial adjustment, and complicate TBI recovery. In addition, periods of high stress may further provoke symptoms of the underlying psychiatric diagnosis.

Reasonable Accommodations

In postsecondary education, reasonable accommodations are formal modifications or adjustments in the school environment that enable individuals with physical or psychological issues to successfully learn and function within the academic institution. In general, these academic accommodations for student veterans with mental health diagnoses involve modifying the learning environment to compensate for delays in executive functioning, such as memorization, recall, and complex analysis. Coursework is not altered; rather specific actions are used to assist the student to process and recall the material more easily. The reasonable accommodations also may be structured in a way that avoids exacerbating an underlying mental health diagnosis, such as PTSD or anxiety. The purpose of reasonable accommodations is to effectively remove barriers to a student veteran’s ability to learn and succeed academically.

Federal law states that reasonable accommodations must be implemented by all schools that accept federal monies—including GI bill payments.39 Although schools are not required to implement all preferred accommodations requested by veterans, academic institutions are required to implement reasonable, effective strategies for the individual student veteran with a psychological diagnosis that causes learning impairment. However, these institutions are not required to proactively determine who might qualify for such accommodations. A school will not initiate formal academic accommodations unless a veteran makes a specific request and provides qualifying documentation.

Many veterans qualify for reasonable accommodations in the academic setting to compensate for the negative impact that mental health issues can have on academic performance. Specifically, student veterans with psychiatric diagnoses are classified as having a learning disability and are eligible to receive academic accommodations if the psychiatric condition substantially limits, or is expected to limit, learning for more than 6 months.39 Individuals with psychiatric conditions in remission are still classified as having a disability if the disorder would impede learning when symptomatic. A veteran does not need to establish verification of a psychiatric diagnosis connected to military service in order to receive formal academic accommodations. Student veterans who qualify for formal academic accommodations can be fully functional in all other areas of their lives. Examples of qualifying psychiatric diagnoses include PTSD, depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia.

Although accommodations are individually tailored, there are frequently used accommodations for student veterans with psychiatric diagnoses that have been extremely helpful for those who qualify. Additional time for testing helps the student veteran compensate for the difficulty with abstract thinking, concentration, attention, and recall. Low stimulus testing environments, such as a quiet room, enable a veteran to more easily concentrate. Additional time for completion of assignments without academic penalties is beneficial for a veteran experiencing difficulty with attention, focus, concentration, and organization. Assistance with note-taking or advanced access to lecture notes helps the veteran compensate for decreased focus, attention, and short-term memory impairment. Permitting short breaks without repercussions during a lecture allows the veteran to regain focus and composure if he or she is having difficulties with concentration, attention, restlessness, anxiety, body pain, or emotional flares. Tutoring can help the veteran overcome slowed executive functioning. Faculty-approved notes on an index card may help the veteran compensate for extreme difficulty with memory recall. To prevent visual distraction while reading, use of a blank note card or blank sheet of paper during testing may make it easier for the veteran to focus on each sentence or test question.

On a case-by-case basis, other creative strategies may be used to enable the student veteran to participate more fully in the academic setting. Preferential class scheduling can be arranged to compensate for severely altered sleep patterns. Such changes to the schedule mean a veteran would not have to attend classes during a time frame when his or her body is accustomed to sleeping. Flexibility with class attendance decreases external stressors for the veteran who is having intermittent difficulty with severe sleep disturbances or anxiety in group settings. “Unstacking” midterms or finals allows the student veteran to avoid back-to-back exams and enables him or her to study more effectively for each exam. Virtual classes with self-pacing options may provide more flexibility to complete course requirements while the veteran is dealing with fluctuating emotional symptoms.

Legal Process

Barring undue hardship to provide accommodations, the ADA of 1990 as amended in 2008 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 enable equal rights and access to benefits and services for all individuals with disabilities to the same degree as persons without such disabilities in multiple environments including the academic setting. Although the U.S. military system narrowly interprets the term disability, individuals classified as having disabilities under these federal laws fall under a much broader definition. Specifically, any person with “a physical or mental impairment that constitutes or results in substantial impediment” of one of life’s major activities is considered to have a disability.39 As per the ADA of 1990, learning is defined as one of the major life activities.39 This law recognizes that the individual with a learning disability may be fully functional in all other areas of his or her life.

Related: Using Life Stories to Connect Veterans and Providers

Because students must officially request and receive approval for these accommodations within the academic institution, the veteran should speak with the school’s disability resource center counselor regarding the process. If the school does not have a disability resource center, then the student veteran should speak to an admissions counselor at the academic facility. The discussion with the facility’s counselor should include which types of accommodations may be possible to compensate for the veteran’s learning impediments. The counselor will inform the veteran of the required medical documentation that enables the school to grant the needed academic accommodations. In general, veterans can qualify for academic accommodations by receiving a letter with medical documentation of the psychiatric disorder, its anticipated effect on learning, and if known, the suggested reasonable accommodations to compensate for the learning deficit. The veteran can receive a qualifying letter from a psychologist, psychiatrist, PCP, social worker, or licensed counselor with the expertise to diagnose and document the disorder. Student veterans can take this letter to the school’s disability resource center to enable the institution to approve and adopt the accommodations for the student veteran. To ensure compliance with privacy regulations and any facility privacy policies, most providers require a signed release of information form before providing the medical documentation letter.

Such letters need to contain only the basic information required by the disability resource center at each school. Common information required for such a letter includes a clear statement that the disorder and diagnosis are present, the symptoms experienced by the student veteran as a result of the diagnosis, and the impact of those symptoms on the veteran’s learning abilities. If possible, the letter also should specify recommended accommodations that can help the student veteran compensate for the disability. Additional details that some schools may request include associated psychological or medical diagnoses and a listing of medications prescribed to the veteran with AEs experienced. Depending on the institution’s individual policy, the letters may require yearly updates. Federal law forbids schools from requiring onerous amounts of documentation to support the need for academic accommodations.

How many of the preapproved accommodations are used is up to the student veteran. Depending on their baseline functional status and mental health issues, eligible veterans may not need to use all the accommodations each semester or for every class. However, formal accommodations are much easier to implement when needed if the student veteran already has the school preapprove them.

Conclusion

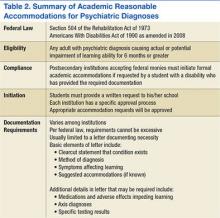

Acquired learning disabilities can prevent successful transition to the student veteran role. Implementation of academic reasonable accommodations is an important avenue by which qualifying post-9/11 student veterans with psychiatric diagnoses can compensate for the negative impact mental health symptoms have on learning styles and academic performance. Because academic stressors and emotional stability are closely intertwined, it is crucial that eligible post-9/11 veterans understand and accept the benefits that formal academic accommodations provide in postsecondary education. Academic accommodations should be offered to empower veterans with mental health concerns. A summary of academic reasonable accommodations is provided in Table 2.

The way clinicians approach this topic will greatly influence veterans’ perspective on academic accommodations. Because there can be a stigma associated with the term learning disability in addition to a general lack of understanding about formal academic accommodations, post-9/11 veterans may not readily pursue the accommodations. Therefore, HCPs should be aware of the best methods for addressing student veterans’ concerns regarding identification of learning disabilities and use of academic accommodations. Unfortunately, information regarding these topics is not readily available in peer-reviewed literature or popular media. Therefore, in part 2, practical interventions for holding crucial conversations with post-9/11 veterans are discussed using a theoretical framework.

1. Barry AE, Whiteman SD, MacDermid Wadsworth S. Student service members/veterans in higher education: a systematic review. J Stud Aff Res Pract. 2014;51(1):30-42.

2. Vasterling JJ, Verfaellie M, Sullivan KD. Mild traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder in returning veterans: perspectives from cognitive neuroscience. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):674-684.

3. Church TE. Returning veterans on campus with war related injuries and the long road back home. J Postsecond Educ Disabil. 2009;22(1):43-52.

4. Ellison ML, Mueller L, Smelson D, et al. Supporting the education goals of post-9/11 veterans with self-reported PTSD symptoms: a needs assessment. Psychiatr Rehab J. 2012;35(3):209-217.

5. Burriss L, Ayers E, Ginsberg J, Powell DA. Learning and memory impairment in PTSD: relationship to depression. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(2):149-157.

6. Sweeney JA, Kmiec JA, Kupfer DJ. Neuropsychologic impairments in bipolar and unipolar mood disorders on the CANTAB neurocognitive battery. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(7):674-684.

7. Chamberlain SR, Sahakian BJ. The neuropsychology of mood disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2006;8(6):458-463.

8. Jaeger J, Berns S, Uzelac S, Davis-Conway S. Neurocognitive deficits and disability in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2006;145(1):39-48.

9. Fava M, Graves LM, Benazzi F, et al. A cross-sectional study of the prevalence of cognitive and physical symptoms during long-term antidepressant treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(11):1754-1759.

10. Senturk V, Goker C, Bilgic A, et al. Impaired verbal memory and otherwise spared cognition in remitted bipolar patients on monotherapy with lithium or valproate. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(suppl 1):136-144.

11. Sayer NA, Noorbaloochi S, Frazier P, Carlson K, Gravely A, Murdoch M. Reintegration problems and treatment interests among Iraq and Afghanistan combat veterans receiving VA medical care. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(6):589-597.

12. Larson GE, Norman SB. Prospective prediction of functional difficulties among recently separated veterans. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2014;51(3):415-427.

13. Slone LB, Friedman MJ. After the War Zone: A Practical Guide for Returning Troops and Their Families. Boston, MA: Da Capo Press; 2008.

14. Walker RL, Clark ME, Sanders SH. The “postdeployment multi-symptom disorder”: an emerging syndrome in need of a new treatment paradigm. Psychol Serv. 2010;7(3):136-147.

15. DiRamio D, Ackerman R, Mitchell RL. From combat to campus: voices of student-veterans. NASPA J. 2008;45(1):73-102.

16. Rumann CB, Hamrick FA. Student veterans in transition: re-enrolling after war zone deployments. J High Educ. 2010;81(4):431-459.

17. Radford AW. Stats in Brief. Military Service Members and Veterans: A Profile of Those Enrolled in Undergraduate and Graduate Education in 2007-08. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2011.

18. Whiteman SD, Barry AE, Mroczek, DK, MacDermid Wadsworth S. The development and implications of peer emotional support for student service members/veterans and civilian college students. J Couns Psychol. 2013;60(2):265-278.

19. Griffin KA, Gilbert CK. Better transitions for troops: an application of Schlossberg’s transition framework to analyses of barriers and institutional support structures for student veterans. J High Educ. 2015;86(1):71-97.

20. Steel JL, Salcedo N, Coley J. Service Members in School: Military Veterans’ Experiences Using the Post-9/11 GI Bill and Pursuing Postsecondary Education. Rand Corporation Website. http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monographs/2011/RAND_MG1083.pdf. Published November 2010. Accessed March 7, 2016.

21. Jones KC. Understanding student veterans in transition. Qual Rep. 2013;18:1-14. http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR18/jones74.pdf. Published September 16, 2013. Accessed March 7, 2016.

22. Saunders GH, Griest SE. Hearing loss in veterans and the need for hearing loss prevention programs. Noise Health. 2009;11(42):14-21.

23. Yankaskas K. Prelude: noise-induced tinnitus and hearing loss in the military. Hear Res. 2013;295:3-8.

24. Hart RP, Martelli MF, Zasler ND. Chronic pain and neuropsychological functioning. Neuropsychol Rev. 2000;10(3):131-149.

25. Sjogren P, Thomsen AB, Olsen AK. Impaired neuropsychological performance in chronic nonmalignant pain patients receiving long-term oral opioid therapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19(2):100-108.

26. McDaniel N, Wolf G, Mahaffy C, Teggins J. Inclusion of students with disabilities in a college chemistry laboratory course. J Postsecond Educ Disabil. 1994;11(1):20-28.

27. Morissette SB, Woodward M, Kimbrel NA, et al. Deployment-related TBI, persistent postconcussive symptoms, PTSD, and depression in OEF/OIF veterans. Rehab Psychol. 2011;56(4):340-350.

28. Orff HJ, Hays CC, Heldreth AA, Stein MB, Twamley EW. Clinical considerations in the evaluation and management of patients following traumatic brain injury. Focus. 2013;11(3):328-340.

29. Schiehser DM, Twamley EW, Liu L, et al. The relationship between postconcussive symptoms and quality of life in veterans with mild to moderate traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2014;30(4):E21-E28.

30. Carlson KF, Nelson D, Orazem RJ, Nugent S, Cifu DX, Sayer NA. Psychiatric diagnoses among Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans screened for deployment-related traumatic brain injury. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23(1):17-24.

31. Taylor BC, Hagel EM, Carlson KF, et al. Prevalence and costs of co-occurring traumatic brain injury with and without psychiatric disturbance and pain among Afghanistan and Iraq war veteran VA Users. Med Care. 2012;50(4):342-346.

32. Bryant RA, O’Donnell ML, Creamer M, McFarlane AC, Clark CR, Silove D. The psychiatric sequelae of traumatic injury. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):312-320.

33. Dolan S, Martindale S, Robinson J, et al. Neuropsychological sequelae of PTSD and TBI following war deployment among OEF/OIF veterans. Neuropsychol Rev. 2012;22(1):21-34.

34. Elliot M, Gonzalez C, Larsen B. U.S. military veterans transition to college: combat, PTSD, and alienation on campus. J Stud Aff Res Pract. 2011;48(3):279-296.

35. Rumann CB, Hamrick FA. Student veterans in transition: re-enrolling after war zone deployments. J High Educ. 2010;81(4):431-458.

36. Deroma VM, Leach JB, Leverett JP. The relationship between depression and college academic performance. Coll Stud J. 2009;43(2):325-334.

37. Brackney BE, Karabenick SA. Psychopathology and academic performance: the role of motivation and learning strategies. J Couns Psychol. 1995;42(4):456-465.

38. Airaksinen E, Larsson M, Lundberg I, Forsell Y. Cognitive functions in depressive disorders: evidence from a population-based study. Psychol Med. 2004;34(1):83-91.

39. United States Access Board. Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990. United States Access Board Website. https://www.access-board.gov/the-board/laws/americans-with-disabilities-act-intro?highlights. Approved July 26, 1990. Accessed March 7, 2016.

Navigating the postsecondary educational pathway can be an intimidating process for post-9/11 veterans struggling with mental health concerns that may alter learning styles and negatively impact performance.1-4 When significant interference with learning ability is anticipated for more than 6 months, these veterans may qualify for formal academic “reasonable” accommodations under federal disability laws that include the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 as amended in 2008 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. These accommodations enable students to compensate for learning disabilities and help support the transition to student life. Student veterans often are not aware of the existence of academic reasonable accommodations, because military separation classes, civilian postdeployment orientation, and popular media do not routinely cover information on this subject.

With an overall objective to ease veteran reintegration into the civilian world and promote emotional stability, health care providers (HCPs) are in a unique position to promote the use of formal academic accommodations for post-9/11 veterans with psychiatric conditions. However, HCPs must have basic information regarding these interventions before initiating discussions with patients. Current peer-reviewed medical literature has scant information regarding specific aspects of academic reasonable accommodations for individuals with psychiatric diagnoses.

The purpose of this 2-part article (part 2 will be published in May 2016) is to promote a greater understanding of academic accommodations for post-9/11 veterans with psychiatric diagnoses. Part 1 provides a brief background regarding issues pertinent to the post-9/11 student veteran role transition and reviews information regarding various aspects of academic reasonable accommodations, including details on the definition, request process, medical documentation requirements, and common accommodation examples.

Although the focus of the article is on the characteristics of post-9/11 veterans who have separated from military service, it also is relevant for providers involved with service members who have not yet separated. The impact of mental health issues, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and psychosocial stressors on learning ability are potentially applicable to many post-9/11 active-duty soldiers and reservists who are pursuing a secondary education. The academic reasonable accommodations discussed are available to any adult who meets the eligibility criteria—regardless of military status.

Influence of Psychiatric Symptoms on Learning

Although each mental health diagnosis is unique, mental health conditions involving mood share the common symptoms of impaired learning ability.3-8 Problems frequently experienced include decreased concentration, shortened attention span, difficulty in making new memories or storing new information, and the inability to recall information previously learned.6-8 Other reported conditions include difficulty with prioritization of tasks, losing track of time, difficulty focusing on tasks, and taking longer to complete assignments.3,4 Increased irritability accompanies many of these issues. Low tolerance to frustration may occur as evidenced by an outburst of anger or resignation to defeat when minor barriers are encountered, especially when authority figures or bureaucratic rules create those perceived barriers.3,4 Persistent impaired ability to articulate ideas or thoughts and difficulty performing abstract thinking also are often noticed when moderate-to-severe mental health symptoms are present.4,8

Medications commonly used to control psychiatric symptoms and stabilize underlying mental health also can produce adverse effects (AEs) that impact learning ability.9,10 Drug AEs vary but often include significant fatigue, impaired memory, and impaired executive function involving insight, judgment, and/or abstract thinking. Depending on the medication, the individual may experience restlessness or insomnia.

Factors Complicating Successful Integration

The transition period from military service to civilian life presents unique complications for student veterans with symptomatic psychiatric concerns.1,11 Veterans who separate from military service go through a civilian transition period of variable intensity influenced by readjustment difficulties and comorbid conditions.11,12 During this time, veterans are reintegrating into civilian life and assuming new roles that include partner, parent, employee, and family member. This transition can cause many symptoms to appear that potentially influence learning to varying degrees. A summary of impediments to learning in post-9/11 veterans is found in Table 1.

Common transition symptoms include irritability, decreased ability to store and recall information, decreased concentration, decreased attention, and slowed executive functioning.13,14 Sleep disturbances such as altered sleep-wake cycles, nonrestful sleep, inadequate sleep, and nightmares also may occur.13,14 Veterans experiencing these transition period symptoms may face significant difficulties with time management skills, organization, and task execution. If the veteran successfully assimilates into his or her new roles and becomes self-confident within those roles, the symptoms may abate. However, if moderate-to-severe psychiatric symptoms also are present, all transition symptoms likely will have an unpredictable time frame for resolution.3,13,14

Understanding the role responsibilities of student veterans is important in recognizing the added stressors veterans with psychiatric diagnoses have within the academic setting. In general, demographic data indicate that student veterans lead far more complex lives than those of 18- to 22-year-olds who enter postsecondary education without military experience. Student veterans are older, have a broader life experience, and may feel less connected to nonveteran students.15,16 Compared with typical younger college students, undergraduate student veterans are more likely to be married but somewhat less likely to be parents.17 Student veterans who are pursuing graduate degrees are more likely to be married and/or have dependents.17 Those roles imply that student veterans often are juggling multiple responsibilities that are constantly competing for student veterans’ time and attention.

Age differences, multiple roles, and lack of shared life experiences with traditional college students contribute to student veterans’ perceptions of a paucity of campus social support and often lead to a sense of distinct isolation.18,19 These added stressors deplete a veteran’s ability to concentrate on academic studies and may exacerbate the effects of underlying mental health diagnoses, transition issues, and medication use.

Symptomatic psychiatric diagnoses can amplify the difficulties normally experienced when changing from a veteran role to a student veteran role.1 The student veteran’s apprehension about returning to school often is elevated because of the time gap since the veteran was last in a formal, nonmilitary classroom. Acclimated to the structured style of military coursework for many years, student veterans may find adjusting to new teaching styles or different academic expectations awkward.20,21 They may experience heightened anxiety, because expectations of classroom performance may not be as clearcut as it was in the military. Such heightened anxiety can compound learning difficulties caused by underlying emotional states, transition issues, medication AEs, and life stressors.

Related: The VA/DoD Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium: An Overview at Year 1

Many student veterans with impaired learning ability related to psychiatric symptoms also have secondary physical diagnoses that can impede learning. For example, tinnitus and hearing loss are common in combat veterans.22,23 These issues make it hard to participate in a classroom setting because of difficulty in recognizing speech or filtering out background noise. For some, chronic pain may impede concentration, depress mood, worsen irritability, and make prolonged sitting difficult.24,25 Physical disabilities related to amputation or major joint injury may present challenges to participating in certain types of college settings and/or navigating between classes in a timely fashion.26

Although mild-to-moderate TBI sustained in combat often will spontaneously resolve within 3 months, in some individuals, TBI symptoms may persist after months or years.27,28 During this time, learning styles may be altered for veterans exposed to TBI. Similar to the effects caused by other factors impeding learning in post-9/11 veterans, common post-TBI symptoms that reduce academic performance include fatigue, decreased memory, slowed abstract thinking, difficulty articulating thoughts, poor tolerance to frustration, sleep difficulties, chronic pain, and increased irritability.27-29 Veterans with a history of mild TBI often are found to have clinically significant rates of depression, anxiety, or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).27,28,30,31 These findings mirror those found in the general population.32 Mild TBI and PTSD may further complicate the learning process by exacerbating underlying mental health symptoms that already impair academic performance. The degree to which these individuals with TBI and mental health issues will return to premorbid academic functioning is not predictable based on current literature.33

Recognizing the stressors that some combat veterans face in an academic setting is vital to anticipating the added support that is needed by student veterans with concurrent moderate-to-severe psychiatric issues.34 Symptoms usually noted in the transition period may be much more pronounced. Automatic behaviors developed as survival responses during deployment can complicate participation in the educational arena.4,35 Seemingly mundane tasks, such as the daily school commute, can cause significant anxiety and hypervigilance especially when the veterans must navigate crowds and traffic formerly associated with risk of attack in combat-related circumstances.4 Minor roadway debris or roadside construction also can abnormally heighten anxiety because of reflex training to avoid potentially hidden explosive devices during convoy movements.4 Random assignment of a classroom seat can be stress-provoking, because combat veterans’ training compels them to position themselves with the greatest vantage point, usually nearest to exits and with minimal activity behind them.4,35 A need to constantly survey the surroundings for potential cover from hostile events can cause hyper alertness that distracts the student veteran’s full concentration on academic tasks.3,4

Although veterans should be able to adjust learning styles for minor issues or transitory problems, significant psychiatric symptoms have a negative effect on learning and pose a direct threat to academic performance.33,36-38 Moderate-to-severe psychiatric concerns may further heighten transition symptoms, compound psychosocial adjustment, and complicate TBI recovery. In addition, periods of high stress may further provoke symptoms of the underlying psychiatric diagnosis.

Reasonable Accommodations

In postsecondary education, reasonable accommodations are formal modifications or adjustments in the school environment that enable individuals with physical or psychological issues to successfully learn and function within the academic institution. In general, these academic accommodations for student veterans with mental health diagnoses involve modifying the learning environment to compensate for delays in executive functioning, such as memorization, recall, and complex analysis. Coursework is not altered; rather specific actions are used to assist the student to process and recall the material more easily. The reasonable accommodations also may be structured in a way that avoids exacerbating an underlying mental health diagnosis, such as PTSD or anxiety. The purpose of reasonable accommodations is to effectively remove barriers to a student veteran’s ability to learn and succeed academically.

Federal law states that reasonable accommodations must be implemented by all schools that accept federal monies—including GI bill payments.39 Although schools are not required to implement all preferred accommodations requested by veterans, academic institutions are required to implement reasonable, effective strategies for the individual student veteran with a psychological diagnosis that causes learning impairment. However, these institutions are not required to proactively determine who might qualify for such accommodations. A school will not initiate formal academic accommodations unless a veteran makes a specific request and provides qualifying documentation.

Many veterans qualify for reasonable accommodations in the academic setting to compensate for the negative impact that mental health issues can have on academic performance. Specifically, student veterans with psychiatric diagnoses are classified as having a learning disability and are eligible to receive academic accommodations if the psychiatric condition substantially limits, or is expected to limit, learning for more than 6 months.39 Individuals with psychiatric conditions in remission are still classified as having a disability if the disorder would impede learning when symptomatic. A veteran does not need to establish verification of a psychiatric diagnosis connected to military service in order to receive formal academic accommodations. Student veterans who qualify for formal academic accommodations can be fully functional in all other areas of their lives. Examples of qualifying psychiatric diagnoses include PTSD, depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia.

Although accommodations are individually tailored, there are frequently used accommodations for student veterans with psychiatric diagnoses that have been extremely helpful for those who qualify. Additional time for testing helps the student veteran compensate for the difficulty with abstract thinking, concentration, attention, and recall. Low stimulus testing environments, such as a quiet room, enable a veteran to more easily concentrate. Additional time for completion of assignments without academic penalties is beneficial for a veteran experiencing difficulty with attention, focus, concentration, and organization. Assistance with note-taking or advanced access to lecture notes helps the veteran compensate for decreased focus, attention, and short-term memory impairment. Permitting short breaks without repercussions during a lecture allows the veteran to regain focus and composure if he or she is having difficulties with concentration, attention, restlessness, anxiety, body pain, or emotional flares. Tutoring can help the veteran overcome slowed executive functioning. Faculty-approved notes on an index card may help the veteran compensate for extreme difficulty with memory recall. To prevent visual distraction while reading, use of a blank note card or blank sheet of paper during testing may make it easier for the veteran to focus on each sentence or test question.

On a case-by-case basis, other creative strategies may be used to enable the student veteran to participate more fully in the academic setting. Preferential class scheduling can be arranged to compensate for severely altered sleep patterns. Such changes to the schedule mean a veteran would not have to attend classes during a time frame when his or her body is accustomed to sleeping. Flexibility with class attendance decreases external stressors for the veteran who is having intermittent difficulty with severe sleep disturbances or anxiety in group settings. “Unstacking” midterms or finals allows the student veteran to avoid back-to-back exams and enables him or her to study more effectively for each exam. Virtual classes with self-pacing options may provide more flexibility to complete course requirements while the veteran is dealing with fluctuating emotional symptoms.

Legal Process

Barring undue hardship to provide accommodations, the ADA of 1990 as amended in 2008 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 enable equal rights and access to benefits and services for all individuals with disabilities to the same degree as persons without such disabilities in multiple environments including the academic setting. Although the U.S. military system narrowly interprets the term disability, individuals classified as having disabilities under these federal laws fall under a much broader definition. Specifically, any person with “a physical or mental impairment that constitutes or results in substantial impediment” of one of life’s major activities is considered to have a disability.39 As per the ADA of 1990, learning is defined as one of the major life activities.39 This law recognizes that the individual with a learning disability may be fully functional in all other areas of his or her life.

Related: Using Life Stories to Connect Veterans and Providers

Because students must officially request and receive approval for these accommodations within the academic institution, the veteran should speak with the school’s disability resource center counselor regarding the process. If the school does not have a disability resource center, then the student veteran should speak to an admissions counselor at the academic facility. The discussion with the facility’s counselor should include which types of accommodations may be possible to compensate for the veteran’s learning impediments. The counselor will inform the veteran of the required medical documentation that enables the school to grant the needed academic accommodations. In general, veterans can qualify for academic accommodations by receiving a letter with medical documentation of the psychiatric disorder, its anticipated effect on learning, and if known, the suggested reasonable accommodations to compensate for the learning deficit. The veteran can receive a qualifying letter from a psychologist, psychiatrist, PCP, social worker, or licensed counselor with the expertise to diagnose and document the disorder. Student veterans can take this letter to the school’s disability resource center to enable the institution to approve and adopt the accommodations for the student veteran. To ensure compliance with privacy regulations and any facility privacy policies, most providers require a signed release of information form before providing the medical documentation letter.

Such letters need to contain only the basic information required by the disability resource center at each school. Common information required for such a letter includes a clear statement that the disorder and diagnosis are present, the symptoms experienced by the student veteran as a result of the diagnosis, and the impact of those symptoms on the veteran’s learning abilities. If possible, the letter also should specify recommended accommodations that can help the student veteran compensate for the disability. Additional details that some schools may request include associated psychological or medical diagnoses and a listing of medications prescribed to the veteran with AEs experienced. Depending on the institution’s individual policy, the letters may require yearly updates. Federal law forbids schools from requiring onerous amounts of documentation to support the need for academic accommodations.

How many of the preapproved accommodations are used is up to the student veteran. Depending on their baseline functional status and mental health issues, eligible veterans may not need to use all the accommodations each semester or for every class. However, formal accommodations are much easier to implement when needed if the student veteran already has the school preapprove them.

Conclusion

Acquired learning disabilities can prevent successful transition to the student veteran role. Implementation of academic reasonable accommodations is an important avenue by which qualifying post-9/11 student veterans with psychiatric diagnoses can compensate for the negative impact mental health symptoms have on learning styles and academic performance. Because academic stressors and emotional stability are closely intertwined, it is crucial that eligible post-9/11 veterans understand and accept the benefits that formal academic accommodations provide in postsecondary education. Academic accommodations should be offered to empower veterans with mental health concerns. A summary of academic reasonable accommodations is provided in Table 2.

The way clinicians approach this topic will greatly influence veterans’ perspective on academic accommodations. Because there can be a stigma associated with the term learning disability in addition to a general lack of understanding about formal academic accommodations, post-9/11 veterans may not readily pursue the accommodations. Therefore, HCPs should be aware of the best methods for addressing student veterans’ concerns regarding identification of learning disabilities and use of academic accommodations. Unfortunately, information regarding these topics is not readily available in peer-reviewed literature or popular media. Therefore, in part 2, practical interventions for holding crucial conversations with post-9/11 veterans are discussed using a theoretical framework.

Navigating the postsecondary educational pathway can be an intimidating process for post-9/11 veterans struggling with mental health concerns that may alter learning styles and negatively impact performance.1-4 When significant interference with learning ability is anticipated for more than 6 months, these veterans may qualify for formal academic “reasonable” accommodations under federal disability laws that include the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 as amended in 2008 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. These accommodations enable students to compensate for learning disabilities and help support the transition to student life. Student veterans often are not aware of the existence of academic reasonable accommodations, because military separation classes, civilian postdeployment orientation, and popular media do not routinely cover information on this subject.

With an overall objective to ease veteran reintegration into the civilian world and promote emotional stability, health care providers (HCPs) are in a unique position to promote the use of formal academic accommodations for post-9/11 veterans with psychiatric conditions. However, HCPs must have basic information regarding these interventions before initiating discussions with patients. Current peer-reviewed medical literature has scant information regarding specific aspects of academic reasonable accommodations for individuals with psychiatric diagnoses.

The purpose of this 2-part article (part 2 will be published in May 2016) is to promote a greater understanding of academic accommodations for post-9/11 veterans with psychiatric diagnoses. Part 1 provides a brief background regarding issues pertinent to the post-9/11 student veteran role transition and reviews information regarding various aspects of academic reasonable accommodations, including details on the definition, request process, medical documentation requirements, and common accommodation examples.

Although the focus of the article is on the characteristics of post-9/11 veterans who have separated from military service, it also is relevant for providers involved with service members who have not yet separated. The impact of mental health issues, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and psychosocial stressors on learning ability are potentially applicable to many post-9/11 active-duty soldiers and reservists who are pursuing a secondary education. The academic reasonable accommodations discussed are available to any adult who meets the eligibility criteria—regardless of military status.

Influence of Psychiatric Symptoms on Learning

Although each mental health diagnosis is unique, mental health conditions involving mood share the common symptoms of impaired learning ability.3-8 Problems frequently experienced include decreased concentration, shortened attention span, difficulty in making new memories or storing new information, and the inability to recall information previously learned.6-8 Other reported conditions include difficulty with prioritization of tasks, losing track of time, difficulty focusing on tasks, and taking longer to complete assignments.3,4 Increased irritability accompanies many of these issues. Low tolerance to frustration may occur as evidenced by an outburst of anger or resignation to defeat when minor barriers are encountered, especially when authority figures or bureaucratic rules create those perceived barriers.3,4 Persistent impaired ability to articulate ideas or thoughts and difficulty performing abstract thinking also are often noticed when moderate-to-severe mental health symptoms are present.4,8

Medications commonly used to control psychiatric symptoms and stabilize underlying mental health also can produce adverse effects (AEs) that impact learning ability.9,10 Drug AEs vary but often include significant fatigue, impaired memory, and impaired executive function involving insight, judgment, and/or abstract thinking. Depending on the medication, the individual may experience restlessness or insomnia.

Factors Complicating Successful Integration

The transition period from military service to civilian life presents unique complications for student veterans with symptomatic psychiatric concerns.1,11 Veterans who separate from military service go through a civilian transition period of variable intensity influenced by readjustment difficulties and comorbid conditions.11,12 During this time, veterans are reintegrating into civilian life and assuming new roles that include partner, parent, employee, and family member. This transition can cause many symptoms to appear that potentially influence learning to varying degrees. A summary of impediments to learning in post-9/11 veterans is found in Table 1.

Common transition symptoms include irritability, decreased ability to store and recall information, decreased concentration, decreased attention, and slowed executive functioning.13,14 Sleep disturbances such as altered sleep-wake cycles, nonrestful sleep, inadequate sleep, and nightmares also may occur.13,14 Veterans experiencing these transition period symptoms may face significant difficulties with time management skills, organization, and task execution. If the veteran successfully assimilates into his or her new roles and becomes self-confident within those roles, the symptoms may abate. However, if moderate-to-severe psychiatric symptoms also are present, all transition symptoms likely will have an unpredictable time frame for resolution.3,13,14

Understanding the role responsibilities of student veterans is important in recognizing the added stressors veterans with psychiatric diagnoses have within the academic setting. In general, demographic data indicate that student veterans lead far more complex lives than those of 18- to 22-year-olds who enter postsecondary education without military experience. Student veterans are older, have a broader life experience, and may feel less connected to nonveteran students.15,16 Compared with typical younger college students, undergraduate student veterans are more likely to be married but somewhat less likely to be parents.17 Student veterans who are pursuing graduate degrees are more likely to be married and/or have dependents.17 Those roles imply that student veterans often are juggling multiple responsibilities that are constantly competing for student veterans’ time and attention.

Age differences, multiple roles, and lack of shared life experiences with traditional college students contribute to student veterans’ perceptions of a paucity of campus social support and often lead to a sense of distinct isolation.18,19 These added stressors deplete a veteran’s ability to concentrate on academic studies and may exacerbate the effects of underlying mental health diagnoses, transition issues, and medication use.

Symptomatic psychiatric diagnoses can amplify the difficulties normally experienced when changing from a veteran role to a student veteran role.1 The student veteran’s apprehension about returning to school often is elevated because of the time gap since the veteran was last in a formal, nonmilitary classroom. Acclimated to the structured style of military coursework for many years, student veterans may find adjusting to new teaching styles or different academic expectations awkward.20,21 They may experience heightened anxiety, because expectations of classroom performance may not be as clearcut as it was in the military. Such heightened anxiety can compound learning difficulties caused by underlying emotional states, transition issues, medication AEs, and life stressors.

Related: The VA/DoD Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium: An Overview at Year 1

Many student veterans with impaired learning ability related to psychiatric symptoms also have secondary physical diagnoses that can impede learning. For example, tinnitus and hearing loss are common in combat veterans.22,23 These issues make it hard to participate in a classroom setting because of difficulty in recognizing speech or filtering out background noise. For some, chronic pain may impede concentration, depress mood, worsen irritability, and make prolonged sitting difficult.24,25 Physical disabilities related to amputation or major joint injury may present challenges to participating in certain types of college settings and/or navigating between classes in a timely fashion.26

Although mild-to-moderate TBI sustained in combat often will spontaneously resolve within 3 months, in some individuals, TBI symptoms may persist after months or years.27,28 During this time, learning styles may be altered for veterans exposed to TBI. Similar to the effects caused by other factors impeding learning in post-9/11 veterans, common post-TBI symptoms that reduce academic performance include fatigue, decreased memory, slowed abstract thinking, difficulty articulating thoughts, poor tolerance to frustration, sleep difficulties, chronic pain, and increased irritability.27-29 Veterans with a history of mild TBI often are found to have clinically significant rates of depression, anxiety, or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).27,28,30,31 These findings mirror those found in the general population.32 Mild TBI and PTSD may further complicate the learning process by exacerbating underlying mental health symptoms that already impair academic performance. The degree to which these individuals with TBI and mental health issues will return to premorbid academic functioning is not predictable based on current literature.33

Recognizing the stressors that some combat veterans face in an academic setting is vital to anticipating the added support that is needed by student veterans with concurrent moderate-to-severe psychiatric issues.34 Symptoms usually noted in the transition period may be much more pronounced. Automatic behaviors developed as survival responses during deployment can complicate participation in the educational arena.4,35 Seemingly mundane tasks, such as the daily school commute, can cause significant anxiety and hypervigilance especially when the veterans must navigate crowds and traffic formerly associated with risk of attack in combat-related circumstances.4 Minor roadway debris or roadside construction also can abnormally heighten anxiety because of reflex training to avoid potentially hidden explosive devices during convoy movements.4 Random assignment of a classroom seat can be stress-provoking, because combat veterans’ training compels them to position themselves with the greatest vantage point, usually nearest to exits and with minimal activity behind them.4,35 A need to constantly survey the surroundings for potential cover from hostile events can cause hyper alertness that distracts the student veteran’s full concentration on academic tasks.3,4

Although veterans should be able to adjust learning styles for minor issues or transitory problems, significant psychiatric symptoms have a negative effect on learning and pose a direct threat to academic performance.33,36-38 Moderate-to-severe psychiatric concerns may further heighten transition symptoms, compound psychosocial adjustment, and complicate TBI recovery. In addition, periods of high stress may further provoke symptoms of the underlying psychiatric diagnosis.

Reasonable Accommodations

In postsecondary education, reasonable accommodations are formal modifications or adjustments in the school environment that enable individuals with physical or psychological issues to successfully learn and function within the academic institution. In general, these academic accommodations for student veterans with mental health diagnoses involve modifying the learning environment to compensate for delays in executive functioning, such as memorization, recall, and complex analysis. Coursework is not altered; rather specific actions are used to assist the student to process and recall the material more easily. The reasonable accommodations also may be structured in a way that avoids exacerbating an underlying mental health diagnosis, such as PTSD or anxiety. The purpose of reasonable accommodations is to effectively remove barriers to a student veteran’s ability to learn and succeed academically.

Federal law states that reasonable accommodations must be implemented by all schools that accept federal monies—including GI bill payments.39 Although schools are not required to implement all preferred accommodations requested by veterans, academic institutions are required to implement reasonable, effective strategies for the individual student veteran with a psychological diagnosis that causes learning impairment. However, these institutions are not required to proactively determine who might qualify for such accommodations. A school will not initiate formal academic accommodations unless a veteran makes a specific request and provides qualifying documentation.

Many veterans qualify for reasonable accommodations in the academic setting to compensate for the negative impact that mental health issues can have on academic performance. Specifically, student veterans with psychiatric diagnoses are classified as having a learning disability and are eligible to receive academic accommodations if the psychiatric condition substantially limits, or is expected to limit, learning for more than 6 months.39 Individuals with psychiatric conditions in remission are still classified as having a disability if the disorder would impede learning when symptomatic. A veteran does not need to establish verification of a psychiatric diagnosis connected to military service in order to receive formal academic accommodations. Student veterans who qualify for formal academic accommodations can be fully functional in all other areas of their lives. Examples of qualifying psychiatric diagnoses include PTSD, depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia.

Although accommodations are individually tailored, there are frequently used accommodations for student veterans with psychiatric diagnoses that have been extremely helpful for those who qualify. Additional time for testing helps the student veteran compensate for the difficulty with abstract thinking, concentration, attention, and recall. Low stimulus testing environments, such as a quiet room, enable a veteran to more easily concentrate. Additional time for completion of assignments without academic penalties is beneficial for a veteran experiencing difficulty with attention, focus, concentration, and organization. Assistance with note-taking or advanced access to lecture notes helps the veteran compensate for decreased focus, attention, and short-term memory impairment. Permitting short breaks without repercussions during a lecture allows the veteran to regain focus and composure if he or she is having difficulties with concentration, attention, restlessness, anxiety, body pain, or emotional flares. Tutoring can help the veteran overcome slowed executive functioning. Faculty-approved notes on an index card may help the veteran compensate for extreme difficulty with memory recall. To prevent visual distraction while reading, use of a blank note card or blank sheet of paper during testing may make it easier for the veteran to focus on each sentence or test question.

On a case-by-case basis, other creative strategies may be used to enable the student veteran to participate more fully in the academic setting. Preferential class scheduling can be arranged to compensate for severely altered sleep patterns. Such changes to the schedule mean a veteran would not have to attend classes during a time frame when his or her body is accustomed to sleeping. Flexibility with class attendance decreases external stressors for the veteran who is having intermittent difficulty with severe sleep disturbances or anxiety in group settings. “Unstacking” midterms or finals allows the student veteran to avoid back-to-back exams and enables him or her to study more effectively for each exam. Virtual classes with self-pacing options may provide more flexibility to complete course requirements while the veteran is dealing with fluctuating emotional symptoms.

Legal Process

Barring undue hardship to provide accommodations, the ADA of 1990 as amended in 2008 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 enable equal rights and access to benefits and services for all individuals with disabilities to the same degree as persons without such disabilities in multiple environments including the academic setting. Although the U.S. military system narrowly interprets the term disability, individuals classified as having disabilities under these federal laws fall under a much broader definition. Specifically, any person with “a physical or mental impairment that constitutes or results in substantial impediment” of one of life’s major activities is considered to have a disability.39 As per the ADA of 1990, learning is defined as one of the major life activities.39 This law recognizes that the individual with a learning disability may be fully functional in all other areas of his or her life.

Related: Using Life Stories to Connect Veterans and Providers

Because students must officially request and receive approval for these accommodations within the academic institution, the veteran should speak with the school’s disability resource center counselor regarding the process. If the school does not have a disability resource center, then the student veteran should speak to an admissions counselor at the academic facility. The discussion with the facility’s counselor should include which types of accommodations may be possible to compensate for the veteran’s learning impediments. The counselor will inform the veteran of the required medical documentation that enables the school to grant the needed academic accommodations. In general, veterans can qualify for academic accommodations by receiving a letter with medical documentation of the psychiatric disorder, its anticipated effect on learning, and if known, the suggested reasonable accommodations to compensate for the learning deficit. The veteran can receive a qualifying letter from a psychologist, psychiatrist, PCP, social worker, or licensed counselor with the expertise to diagnose and document the disorder. Student veterans can take this letter to the school’s disability resource center to enable the institution to approve and adopt the accommodations for the student veteran. To ensure compliance with privacy regulations and any facility privacy policies, most providers require a signed release of information form before providing the medical documentation letter.

Such letters need to contain only the basic information required by the disability resource center at each school. Common information required for such a letter includes a clear statement that the disorder and diagnosis are present, the symptoms experienced by the student veteran as a result of the diagnosis, and the impact of those symptoms on the veteran’s learning abilities. If possible, the letter also should specify recommended accommodations that can help the student veteran compensate for the disability. Additional details that some schools may request include associated psychological or medical diagnoses and a listing of medications prescribed to the veteran with AEs experienced. Depending on the institution’s individual policy, the letters may require yearly updates. Federal law forbids schools from requiring onerous amounts of documentation to support the need for academic accommodations.

How many of the preapproved accommodations are used is up to the student veteran. Depending on their baseline functional status and mental health issues, eligible veterans may not need to use all the accommodations each semester or for every class. However, formal accommodations are much easier to implement when needed if the student veteran already has the school preapprove them.

Conclusion

Acquired learning disabilities can prevent successful transition to the student veteran role. Implementation of academic reasonable accommodations is an important avenue by which qualifying post-9/11 student veterans with psychiatric diagnoses can compensate for the negative impact mental health symptoms have on learning styles and academic performance. Because academic stressors and emotional stability are closely intertwined, it is crucial that eligible post-9/11 veterans understand and accept the benefits that formal academic accommodations provide in postsecondary education. Academic accommodations should be offered to empower veterans with mental health concerns. A summary of academic reasonable accommodations is provided in Table 2.

The way clinicians approach this topic will greatly influence veterans’ perspective on academic accommodations. Because there can be a stigma associated with the term learning disability in addition to a general lack of understanding about formal academic accommodations, post-9/11 veterans may not readily pursue the accommodations. Therefore, HCPs should be aware of the best methods for addressing student veterans’ concerns regarding identification of learning disabilities and use of academic accommodations. Unfortunately, information regarding these topics is not readily available in peer-reviewed literature or popular media. Therefore, in part 2, practical interventions for holding crucial conversations with post-9/11 veterans are discussed using a theoretical framework.

1. Barry AE, Whiteman SD, MacDermid Wadsworth S. Student service members/veterans in higher education: a systematic review. J Stud Aff Res Pract. 2014;51(1):30-42.

2. Vasterling JJ, Verfaellie M, Sullivan KD. Mild traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder in returning veterans: perspectives from cognitive neuroscience. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):674-684.

3. Church TE. Returning veterans on campus with war related injuries and the long road back home. J Postsecond Educ Disabil. 2009;22(1):43-52.

4. Ellison ML, Mueller L, Smelson D, et al. Supporting the education goals of post-9/11 veterans with self-reported PTSD symptoms: a needs assessment. Psychiatr Rehab J. 2012;35(3):209-217.

5. Burriss L, Ayers E, Ginsberg J, Powell DA. Learning and memory impairment in PTSD: relationship to depression. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(2):149-157.

6. Sweeney JA, Kmiec JA, Kupfer DJ. Neuropsychologic impairments in bipolar and unipolar mood disorders on the CANTAB neurocognitive battery. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(7):674-684.

7. Chamberlain SR, Sahakian BJ. The neuropsychology of mood disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2006;8(6):458-463.

8. Jaeger J, Berns S, Uzelac S, Davis-Conway S. Neurocognitive deficits and disability in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2006;145(1):39-48.

9. Fava M, Graves LM, Benazzi F, et al. A cross-sectional study of the prevalence of cognitive and physical symptoms during long-term antidepressant treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(11):1754-1759.

10. Senturk V, Goker C, Bilgic A, et al. Impaired verbal memory and otherwise spared cognition in remitted bipolar patients on monotherapy with lithium or valproate. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9(suppl 1):136-144.

11. Sayer NA, Noorbaloochi S, Frazier P, Carlson K, Gravely A, Murdoch M. Reintegration problems and treatment interests among Iraq and Afghanistan combat veterans receiving VA medical care. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(6):589-597.

12. Larson GE, Norman SB. Prospective prediction of functional difficulties among recently separated veterans. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2014;51(3):415-427.

13. Slone LB, Friedman MJ. After the War Zone: A Practical Guide for Returning Troops and Their Families. Boston, MA: Da Capo Press; 2008.

14. Walker RL, Clark ME, Sanders SH. The “postdeployment multi-symptom disorder”: an emerging syndrome in need of a new treatment paradigm. Psychol Serv. 2010;7(3):136-147.

15. DiRamio D, Ackerman R, Mitchell RL. From combat to campus: voices of student-veterans. NASPA J. 2008;45(1):73-102.

16. Rumann CB, Hamrick FA. Student veterans in transition: re-enrolling after war zone deployments. J High Educ. 2010;81(4):431-459.

17. Radford AW. Stats in Brief. Military Service Members and Veterans: A Profile of Those Enrolled in Undergraduate and Graduate Education in 2007-08. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2011.

18. Whiteman SD, Barry AE, Mroczek, DK, MacDermid Wadsworth S. The development and implications of peer emotional support for student service members/veterans and civilian college students. J Couns Psychol. 2013;60(2):265-278.

19. Griffin KA, Gilbert CK. Better transitions for troops: an application of Schlossberg’s transition framework to analyses of barriers and institutional support structures for student veterans. J High Educ. 2015;86(1):71-97.

20. Steel JL, Salcedo N, Coley J. Service Members in School: Military Veterans’ Experiences Using the Post-9/11 GI Bill and Pursuing Postsecondary Education. Rand Corporation Website. http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monographs/2011/RAND_MG1083.pdf. Published November 2010. Accessed March 7, 2016.

21. Jones KC. Understanding student veterans in transition. Qual Rep. 2013;18:1-14. http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR18/jones74.pdf. Published September 16, 2013. Accessed March 7, 2016.

22. Saunders GH, Griest SE. Hearing loss in veterans and the need for hearing loss prevention programs. Noise Health. 2009;11(42):14-21.

23. Yankaskas K. Prelude: noise-induced tinnitus and hearing loss in the military. Hear Res. 2013;295:3-8.

24. Hart RP, Martelli MF, Zasler ND. Chronic pain and neuropsychological functioning. Neuropsychol Rev. 2000;10(3):131-149.

25. Sjogren P, Thomsen AB, Olsen AK. Impaired neuropsychological performance in chronic nonmalignant pain patients receiving long-term oral opioid therapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19(2):100-108.

26. McDaniel N, Wolf G, Mahaffy C, Teggins J. Inclusion of students with disabilities in a college chemistry laboratory course. J Postsecond Educ Disabil. 1994;11(1):20-28.

27. Morissette SB, Woodward M, Kimbrel NA, et al. Deployment-related TBI, persistent postconcussive symptoms, PTSD, and depression in OEF/OIF veterans. Rehab Psychol. 2011;56(4):340-350.

28. Orff HJ, Hays CC, Heldreth AA, Stein MB, Twamley EW. Clinical considerations in the evaluation and management of patients following traumatic brain injury. Focus. 2013;11(3):328-340.

29. Schiehser DM, Twamley EW, Liu L, et al. The relationship between postconcussive symptoms and quality of life in veterans with mild to moderate traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2014;30(4):E21-E28.

30. Carlson KF, Nelson D, Orazem RJ, Nugent S, Cifu DX, Sayer NA. Psychiatric diagnoses among Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans screened for deployment-related traumatic brain injury. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23(1):17-24.

31. Taylor BC, Hagel EM, Carlson KF, et al. Prevalence and costs of co-occurring traumatic brain injury with and without psychiatric disturbance and pain among Afghanistan and Iraq war veteran VA Users. Med Care. 2012;50(4):342-346.

32. Bryant RA, O’Donnell ML, Creamer M, McFarlane AC, Clark CR, Silove D. The psychiatric sequelae of traumatic injury. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):312-320.

33. Dolan S, Martindale S, Robinson J, et al. Neuropsychological sequelae of PTSD and TBI following war deployment among OEF/OIF veterans. Neuropsychol Rev. 2012;22(1):21-34.

34. Elliot M, Gonzalez C, Larsen B. U.S. military veterans transition to college: combat, PTSD, and alienation on campus. J Stud Aff Res Pract. 2011;48(3):279-296.

35. Rumann CB, Hamrick FA. Student veterans in transition: re-enrolling after war zone deployments. J High Educ. 2010;81(4):431-458.

36. Deroma VM, Leach JB, Leverett JP. The relationship between depression and college academic performance. Coll Stud J. 2009;43(2):325-334.

37. Brackney BE, Karabenick SA. Psychopathology and academic performance: the role of motivation and learning strategies. J Couns Psychol. 1995;42(4):456-465.

38. Airaksinen E, Larsson M, Lundberg I, Forsell Y. Cognitive functions in depressive disorders: evidence from a population-based study. Psychol Med. 2004;34(1):83-91.

39. United States Access Board. Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990. United States Access Board Website. https://www.access-board.gov/the-board/laws/americans-with-disabilities-act-intro?highlights. Approved July 26, 1990. Accessed March 7, 2016.

1. Barry AE, Whiteman SD, MacDermid Wadsworth S. Student service members/veterans in higher education: a systematic review. J Stud Aff Res Pract. 2014;51(1):30-42.

2. Vasterling JJ, Verfaellie M, Sullivan KD. Mild traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress disorder in returning veterans: perspectives from cognitive neuroscience. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):674-684.