User login

With the number of aging Americans projected to grow dramatically in the next several years, the need for primary palliative care and advance care planning (ACP) is more important than ever. Patients and their families want and expect palliative care when needed, but initial conversations about ACP can be difficult for them. Appropriate timing in raising this subject and clear communication can give patients the opportunity, while they are still independent, to set their goals for medical care.

For the past several decades, political decisions and judicial cases have shaped palliative care as we know it today. And its shape is still evolving. In support of ACP, advocacy groups at a national level are developing models that practitioners can use to engage patients in setting goals. And Medicare is now reimbursing primary care providers for this work that they have been doing for years (although many still may not be billing for the service).

Finally, the busy primary care office may have its own set of challenges in addressing ACP. Our aim in this review is to identify the barriers we face and the solutions we can implement to make a difference in our patients’ end-of-life care planning.

LANDMARK EVENTS HAVE DEFINED ACP TODAY

In 1969, Luis Kutner, an Illinois attorney, proposed the idea of a “living will,” envisioned as a document specifying the types of treatment a person would be willing to receive were he or she unable at a later time to participate in making a decision.1 In 1976, California became the first state to give living wills the power of the law through the Natural Death Act.2

Throughout the 1970s and ‘80s, several high-profile court cases brought this idea into the national spotlight. In 1975, the New Jersey Supreme Court granted the parents of 21-year-old Karen Ann Quinlan the right to discontinue the treatment sustaining her in a persistent vegetative state. Ms. Quinlan was removed from the ventilator and lived nine more months before dying in a nursing home.

In 1983, age 25, Nancy Cruzan was involved in a motor vehicle accident that left her in a persistent vegetative state. She remained so until 1988, when her parents asked that her feeding tube be removed. The hospital refused, indicating that it would lead to her death. The family sued, and the case eventually went to the US Supreme Court in 1989.

In a 5-to-4 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that a state was legally able to require “clear and convincing evidence” of a patient’s wish for removal of life-sustaining therapies. Cruzan’s family was able to provide such evidence, and her artificial nutrition was withheld. She died 12 days later.

The Cruzan case was instrumental in furthering ACP, leading to the passage of the Patient Self Determination Act by Congress in 1990. All federally funded health care facilities were now required to educate patients of their rights in determining their medical care and to ask about advance directives.3 The ACP movement gained additional momentum from the landmark SUPPORT study that documented shortcomings in communication between physicians and patients/families about treatment preferences and end-of-life care in US hospitals.4

In the Terri Schiavo case, the patient’s husband disagreed with the life-sustaining decisions of his wife’s parents, given her persistent vegetative state and the fact that she had no chance of meaningful recovery. After a prolonged national debate, it was ultimately decided that the husband could elect to withhold artificial nutrition. (She died in 2005.) The Schiavo case, as well as the Institute of Medicine’s report on Dying in America, influenced Congress in 2016 to pass legislation funding ACP conversations.5

THE DEMONSTRATED BENEFITS OF ACP

When done comprehensively, ACP yields many benefits for patients and families and for the health care system. A systematic review demonstrated that, despite the few studies examining the economic cost of ACP, the process may lead to decreased health care costs in certain populations (nursing home residents, community-dwelling adults with dementia, and those living in high health care–spending regions) and at the very least does not increase health care costs.6 ACP has increased the number of do-not-resuscitate orders and has decreased hospitalizations, admissions to intensive care units, and rates of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, mechanical ventilation, and use of tube feeding.6-8

More noteworthy than the decrease in resource utilization and potential cost savings is the impact that ACP can have on a patient’s quality of life. Patients who receive aggressive care at the end of life tend to experience decreased quality of life compared with those receiving hospice care.7 Quality-of-life scores for patients in hospice improved with the length of enrollment in that care.7 When ACP discussions have taken place, the care patients receive at the end of life tends to conform more closely to their wishes and to increase family satisfaction.9-11

One reason that practitioners often give for not completing ACP is the fear of increasing patient or family anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). However, studies have shown this concern to be unfounded.7,12 While ACP studies have not shown a decrease in rates of anxiety or PTSD, no study has shown an increase in these psychologic morbidities.8

Caveats to keep in mind. Not all studies have shown unambiguous benefits related to ACP. Among the systematic reviews previously noted, there was significant variability in quality of data. Additionally, some experts argue that the traditional view of ACP (ie, completion of a single advance directive/living will) is outdated and should be replaced with a method that prepares patients and families to anticipate “in-the-moment decision making.”13 While we still believe that completion of an advance directive is useful, the experts’ point is well taken, especially since many patients change their preferences over time (and typically toward more aggressive care).14,15 While the advance directive serves a role, it is more important to help patients recognize their goals and preferences and to facilitate ongoing discussions between the patient and his or her family/surrogate decision-maker and providers.

A SNAPSHOT OF PARTICIPATION IN ACP

Despite the ACP movement and the likely benefits associated with it, most individuals have not participated. Rates of completion do seem to be rising, but there is still room for improvement. Among all individuals older than 18, only 26.3% have an advance directive.16 In a cohort of older patients seen in an emergency department, only 40% had a living will, while nearly 54% had a designated health care power of attorney.17 Perhaps more alarming is the lack of ACP for those patients almost all providers would agree need it: the long-term care population. The National Center for Health Statistics has reported that only 28% of home health care patients, 65% of nursing home residents, and 88% of hospice patients have an advance directive on file.18

PROVIDER AND PATIENT BARRIERS TO ACP

If ACP can decrease resource utilization and improve caregiver compliance with a patient’s wishes for end of life, the obvious question is: Why isn’t it done more often? A longstanding barrier for providers has been that these types of discussions are time intensive and have not been billable. However, since January 1, 2016, we are now able to bill for these discussions. (More on this in a bit.) Providers do cite other barriers, though.

A recent systematic review showed that ACP is hindered by time constraints imposed by other clinical and administrative tasks that are heavily monitored.19 Barriers to engaging in ACP reported by patients include a reluctance to think about dying, a belief that family or providers will know what to do, difficulty understanding ACP forms, and the absence of a person who can serve as a surrogate decision-maker.20,21

NATIONAL MODELS TO HELP WITH IMPLEMENTATION

The percentage of individuals with an advance directive in the US has not increased significantly over the past decade.22 The lack of traction in completion and use of advance directives has led several authors to question the utility of this older model of ACP.22 Several experts in the field believe that more robust, ongoing goals-of-care conversations between patients, families, and providers are equally, or even more, important than the completion of actual advance directive documents.23,24

National models such as the POLST (Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment) paradigm have become popular in several states (www.polst.org). Intended for those with estimated life expectancy of less than one year, POLST is not an advance directive but a physician order for these seriously ill patients. Emergency medical service workers are legally able to follow a POLST document but not a living will or advance directive—a significant reason for those with end-stage illness to consider completing a POLST document with their health care provider. Programs such as “Respecting Choices” have incorporated POLST documentation as part of ongoing goals-of-care conversations between patients and health care providers (www.gundersenhealth.org/respecting-choices).

Many groups have developed products to encourage patients and their families to initiate conversations at home. An example is the Conversation Project, a free online resource available in multiple languages that can help break the ice for patients and get them talking about their wishes for end-of-life care (www.theconversationproject.org). It poses simple stimulating questions such as “What kind of role do you want to have in the decision-making process?” and “What are your concerns about treatment?”

HOW-TO TIPS FOR ACP IN OUTPATIENT SETTINGS

When approaching the topic of ACP with patients, it’s important to do so over time, starting as soon as possible with older patients and those with chronic illness that confers a high risk for significant morbidity or mortality. Assess each patient’s understanding of ACP and readiness to discuss the topic. Many patients think of ACP in the context of a document (eg, living will), so asking about the existence of a living will may help to start the conversation. Alternatively, consider inquiring about whether the patient has had experience with family or friends at the end of life or during a difficult medical situation, and whether the patient has thought about making personal plans for such a situation.25

When a patient is ready to have this conversation, your goal should be three-fold:26

- Help the patient articulate personal values, goals, and preferences.

- Ask the patient to formally assign health care power of attorney (POA) to a trusted individual or to name a surrogate decision-maker. Document this decision in the medical record.

- Help the patient translate expressed values into specific medical care plans, if applicable.

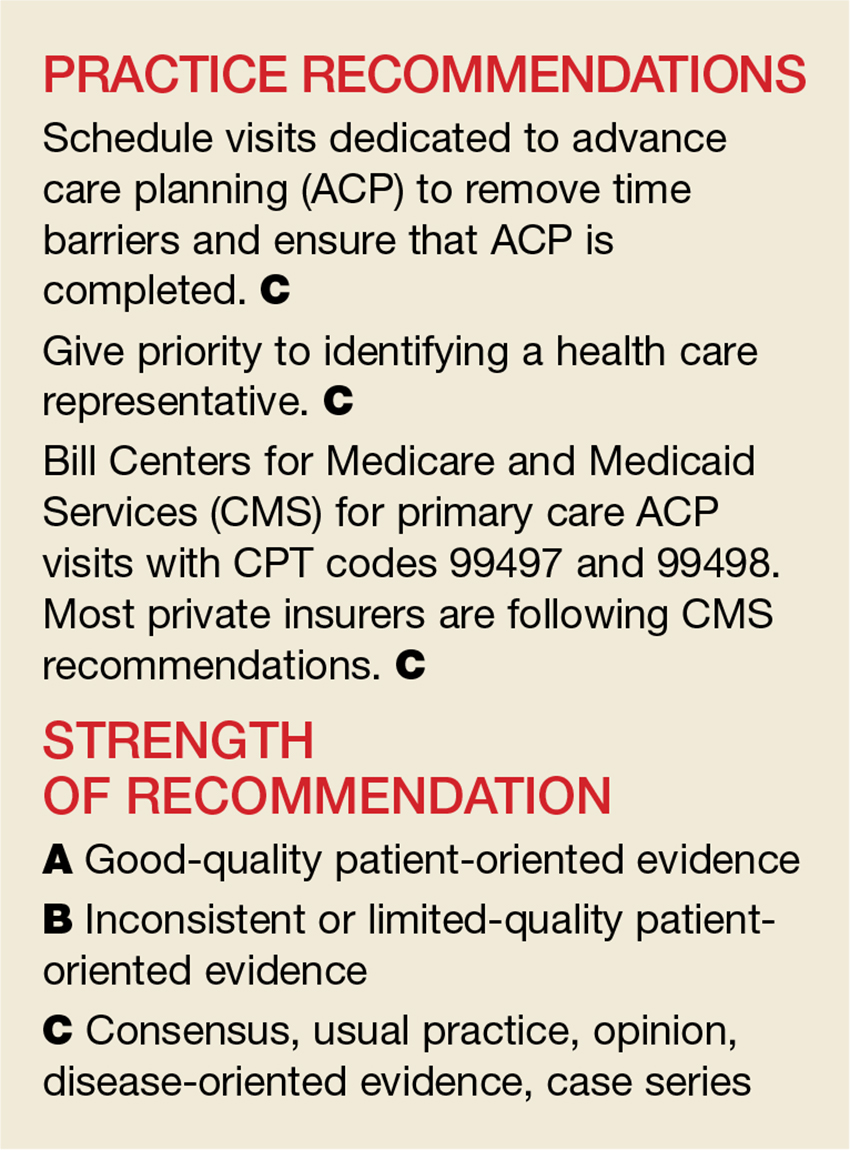

Because ACP conversations are often time consuming, it’s a good idea to schedule separate appointments to focus on this alone. If, however, a patient is unable to return for a dedicated ACP visit, a first step that can be completed in a reasonably short period would be choosing a surrogate decision-maker.

Helping a patient articulate personal values may be eased by asking such questions as, “Have you ever thought about what kind of care you would want if the time came when you could not make your own decisions?” or “What worries you the most about possibly not being able to make your own decisions?”27 If the patient is able to identify a surrogate decision-maker before the ACP appointment, ask that this person attend. A family member or close friend may remember instances in which the patient expressed health care preferences, and their presence can help to minimize gaps in communication.

Once the patient’s preferences are clear, document them in the medical record. Some preferences may be suitable for translation into POLST orders or an advance directive, but this is less important than the overall discussion. ACP should be an ongoing conversation, since a patient’s goals may change over time. And encourage the patient to share any desired change in plans with their surrogate decision-maker or update the POA document.

BE SURE TO BILL FOR ACP SERVICES

To encourage office-based providers to conduct ACP, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) implemented payment for CPT codes 99497 and 99498.

CPT code 99497 covers the first 30 minutes of face-to-face time with patients or their family members or medical decision-makers. This time can be used to discuss living wills or advance directives.

CPT code 99498 can be applied to each additional 30 minutes of ACP services. Typically, this billing code would be used as an add-on for a particular diagnosis, such as heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or pancreatic cancer.

CPT Code 99497 equates to 2.40 relative-value units (RVU) with an estimated payment of $85.99, while CPT code 99498 equates to 2.09 RVU with an estimated payment of $74.88.28

According to CMS, there is no annual limit to the number of times the ACP codes can be billed for a particular patient. And there are no restrictions regarding location of service, meaning a provider could perform this in an outpatient setting, an inpatient setting, or a long-term care facility. All health care providers are allowed to bill with this code. Also worth noting: You don’t need to complete any particular documentation for a visit to be billed as an ACP service. CMS provides a helpful Q & A at www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/Downloads/FAQ-Advance-Care-Planning.pdf.

1. Kutner L. Due process of euthanasia: the living will, a proposal. Indiana Law J. 1969;44:539-554.

2. California Law Revision Commission. 2000 Health Care Decisions Law and Revised Power of Attorney Law. www.clrc.ca.gov/pub/Printed-Reports/Pub208.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

3. H.R. 5067 - 101st Congress. Patient Self Determination Act of 1990. www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/101/hr5067. Accessed August 14, 2017.

4. The SUPPORT Principle Investigators. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments (SUPPORT). JAMA. 1995;274:1591-1598.

5. Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2015.

6. Dixon J, Matosevic T, Knapp M. The economic evidence for advance care planning: systematic review of evidence. Palliat Med. 2015;29:869-884.

7. Wright AA, Ray A, Mack JW, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental-health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665-1673.

8. Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens JAC, van der Heide A. The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2014;28:1000-1025.

9. Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, et al. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1345.

10. Morrison RS, Chichin E, Carter J, et al. The effect of a social work intervention to enhance advance care planning documentation in the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:290-294.

11. Schamp R, Tenkku L. Managed death in a PACE: pathways in present and advance directives. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2006;7:339-344.

12. Walczak A, Butow PN, Bu S, et al. A systematic review of evidence for end-of-life communication interventions: who do they target, how are they structured and do they work? Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99:3-16.

13. Sudore RL, Fried TR. Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:256-261.

14. Straton JB, Wang NY, Meoni LA, et al. Physical functioning, depression, and preferences for treatment at the end of life: the Johns Hopkins Precursors study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:577-582.

15. Fried TR, Byers AL, Gallo WT, et al. Prospective study of health status preferences and changes in preferences over time in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:890-895.

16. Rao JK, Anderson LA, Lin F, et al. Completion of advance directives among U.S. consumers. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46:65-70.

17. Grudzen CR, Buonocore P, Steinberg J, et al; AAHPM Research Committee Writing Group. Concordance of advance care plans with inpatient directives in the electronic medical record for older patients admitted from the emergency department. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51:647-651.

18. Jones AL, Moss AJ, Harris-Kojetin LD. Use of advance directives in long-term care populations. NCHS Data Brief. 2011;(54):1-8.

19. Lund S, Richardson A, May C. Barriers to advance care planning at the end of life: an explanatory systematic review of implementation studies. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116629.

20. Fried TR, Bullock K, Iannone L, et al. Understanding advance care planning as a process of health behavior change. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1547-1555.

21. Schickedanz AD, Schillinger D, Landefeld CS, et al. A clinical framework for improving the advance care planning process: start with patients’ self-identified barriers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:31-39.

22. Winter L, Parks SM, Diamond JJ. Ask a different question, get a different answer: why living wills are poor guides to care preferences at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:567-572.

23. Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. www.nap.edu/read/18748/chapter/1. Accessed August 14, 2017.

24. Sudore RL, Schickedanz AD, Landefeld CS, et al. Engagement in multiple steps of the advance care planning process: a descriptive study of diverse older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1006-1013.

25. McMahan RD, Knight SJ, Fried TR, et al. Advance care planning beyond advance directives: perspectives from patients and surrogates. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46:355-365.

26. Lum HD, Sudore RL, Bekelman DB. Advance care planning in the elderly. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99:391-403.

27. Lum HD, Sudore RL. Advance care planning and goals of care communication in older adults with cardiovascular disease and multi-morbidity. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32:247-260.

28. American College of Physicians. Advanced Care Planning: Implementation for practices. www.acponline.org/system/files/documents/practice-resources/business-resources/payment/advance_care_planning_toolkit.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

With the number of aging Americans projected to grow dramatically in the next several years, the need for primary palliative care and advance care planning (ACP) is more important than ever. Patients and their families want and expect palliative care when needed, but initial conversations about ACP can be difficult for them. Appropriate timing in raising this subject and clear communication can give patients the opportunity, while they are still independent, to set their goals for medical care.

For the past several decades, political decisions and judicial cases have shaped palliative care as we know it today. And its shape is still evolving. In support of ACP, advocacy groups at a national level are developing models that practitioners can use to engage patients in setting goals. And Medicare is now reimbursing primary care providers for this work that they have been doing for years (although many still may not be billing for the service).

Finally, the busy primary care office may have its own set of challenges in addressing ACP. Our aim in this review is to identify the barriers we face and the solutions we can implement to make a difference in our patients’ end-of-life care planning.

LANDMARK EVENTS HAVE DEFINED ACP TODAY

In 1969, Luis Kutner, an Illinois attorney, proposed the idea of a “living will,” envisioned as a document specifying the types of treatment a person would be willing to receive were he or she unable at a later time to participate in making a decision.1 In 1976, California became the first state to give living wills the power of the law through the Natural Death Act.2

Throughout the 1970s and ‘80s, several high-profile court cases brought this idea into the national spotlight. In 1975, the New Jersey Supreme Court granted the parents of 21-year-old Karen Ann Quinlan the right to discontinue the treatment sustaining her in a persistent vegetative state. Ms. Quinlan was removed from the ventilator and lived nine more months before dying in a nursing home.

In 1983, age 25, Nancy Cruzan was involved in a motor vehicle accident that left her in a persistent vegetative state. She remained so until 1988, when her parents asked that her feeding tube be removed. The hospital refused, indicating that it would lead to her death. The family sued, and the case eventually went to the US Supreme Court in 1989.

In a 5-to-4 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that a state was legally able to require “clear and convincing evidence” of a patient’s wish for removal of life-sustaining therapies. Cruzan’s family was able to provide such evidence, and her artificial nutrition was withheld. She died 12 days later.

The Cruzan case was instrumental in furthering ACP, leading to the passage of the Patient Self Determination Act by Congress in 1990. All federally funded health care facilities were now required to educate patients of their rights in determining their medical care and to ask about advance directives.3 The ACP movement gained additional momentum from the landmark SUPPORT study that documented shortcomings in communication between physicians and patients/families about treatment preferences and end-of-life care in US hospitals.4

In the Terri Schiavo case, the patient’s husband disagreed with the life-sustaining decisions of his wife’s parents, given her persistent vegetative state and the fact that she had no chance of meaningful recovery. After a prolonged national debate, it was ultimately decided that the husband could elect to withhold artificial nutrition. (She died in 2005.) The Schiavo case, as well as the Institute of Medicine’s report on Dying in America, influenced Congress in 2016 to pass legislation funding ACP conversations.5

THE DEMONSTRATED BENEFITS OF ACP

When done comprehensively, ACP yields many benefits for patients and families and for the health care system. A systematic review demonstrated that, despite the few studies examining the economic cost of ACP, the process may lead to decreased health care costs in certain populations (nursing home residents, community-dwelling adults with dementia, and those living in high health care–spending regions) and at the very least does not increase health care costs.6 ACP has increased the number of do-not-resuscitate orders and has decreased hospitalizations, admissions to intensive care units, and rates of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, mechanical ventilation, and use of tube feeding.6-8

More noteworthy than the decrease in resource utilization and potential cost savings is the impact that ACP can have on a patient’s quality of life. Patients who receive aggressive care at the end of life tend to experience decreased quality of life compared with those receiving hospice care.7 Quality-of-life scores for patients in hospice improved with the length of enrollment in that care.7 When ACP discussions have taken place, the care patients receive at the end of life tends to conform more closely to their wishes and to increase family satisfaction.9-11

One reason that practitioners often give for not completing ACP is the fear of increasing patient or family anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). However, studies have shown this concern to be unfounded.7,12 While ACP studies have not shown a decrease in rates of anxiety or PTSD, no study has shown an increase in these psychologic morbidities.8

Caveats to keep in mind. Not all studies have shown unambiguous benefits related to ACP. Among the systematic reviews previously noted, there was significant variability in quality of data. Additionally, some experts argue that the traditional view of ACP (ie, completion of a single advance directive/living will) is outdated and should be replaced with a method that prepares patients and families to anticipate “in-the-moment decision making.”13 While we still believe that completion of an advance directive is useful, the experts’ point is well taken, especially since many patients change their preferences over time (and typically toward more aggressive care).14,15 While the advance directive serves a role, it is more important to help patients recognize their goals and preferences and to facilitate ongoing discussions between the patient and his or her family/surrogate decision-maker and providers.

A SNAPSHOT OF PARTICIPATION IN ACP

Despite the ACP movement and the likely benefits associated with it, most individuals have not participated. Rates of completion do seem to be rising, but there is still room for improvement. Among all individuals older than 18, only 26.3% have an advance directive.16 In a cohort of older patients seen in an emergency department, only 40% had a living will, while nearly 54% had a designated health care power of attorney.17 Perhaps more alarming is the lack of ACP for those patients almost all providers would agree need it: the long-term care population. The National Center for Health Statistics has reported that only 28% of home health care patients, 65% of nursing home residents, and 88% of hospice patients have an advance directive on file.18

PROVIDER AND PATIENT BARRIERS TO ACP

If ACP can decrease resource utilization and improve caregiver compliance with a patient’s wishes for end of life, the obvious question is: Why isn’t it done more often? A longstanding barrier for providers has been that these types of discussions are time intensive and have not been billable. However, since January 1, 2016, we are now able to bill for these discussions. (More on this in a bit.) Providers do cite other barriers, though.

A recent systematic review showed that ACP is hindered by time constraints imposed by other clinical and administrative tasks that are heavily monitored.19 Barriers to engaging in ACP reported by patients include a reluctance to think about dying, a belief that family or providers will know what to do, difficulty understanding ACP forms, and the absence of a person who can serve as a surrogate decision-maker.20,21

NATIONAL MODELS TO HELP WITH IMPLEMENTATION

The percentage of individuals with an advance directive in the US has not increased significantly over the past decade.22 The lack of traction in completion and use of advance directives has led several authors to question the utility of this older model of ACP.22 Several experts in the field believe that more robust, ongoing goals-of-care conversations between patients, families, and providers are equally, or even more, important than the completion of actual advance directive documents.23,24

National models such as the POLST (Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment) paradigm have become popular in several states (www.polst.org). Intended for those with estimated life expectancy of less than one year, POLST is not an advance directive but a physician order for these seriously ill patients. Emergency medical service workers are legally able to follow a POLST document but not a living will or advance directive—a significant reason for those with end-stage illness to consider completing a POLST document with their health care provider. Programs such as “Respecting Choices” have incorporated POLST documentation as part of ongoing goals-of-care conversations between patients and health care providers (www.gundersenhealth.org/respecting-choices).

Many groups have developed products to encourage patients and their families to initiate conversations at home. An example is the Conversation Project, a free online resource available in multiple languages that can help break the ice for patients and get them talking about their wishes for end-of-life care (www.theconversationproject.org). It poses simple stimulating questions such as “What kind of role do you want to have in the decision-making process?” and “What are your concerns about treatment?”

HOW-TO TIPS FOR ACP IN OUTPATIENT SETTINGS

When approaching the topic of ACP with patients, it’s important to do so over time, starting as soon as possible with older patients and those with chronic illness that confers a high risk for significant morbidity or mortality. Assess each patient’s understanding of ACP and readiness to discuss the topic. Many patients think of ACP in the context of a document (eg, living will), so asking about the existence of a living will may help to start the conversation. Alternatively, consider inquiring about whether the patient has had experience with family or friends at the end of life or during a difficult medical situation, and whether the patient has thought about making personal plans for such a situation.25

When a patient is ready to have this conversation, your goal should be three-fold:26

- Help the patient articulate personal values, goals, and preferences.

- Ask the patient to formally assign health care power of attorney (POA) to a trusted individual or to name a surrogate decision-maker. Document this decision in the medical record.

- Help the patient translate expressed values into specific medical care plans, if applicable.

Because ACP conversations are often time consuming, it’s a good idea to schedule separate appointments to focus on this alone. If, however, a patient is unable to return for a dedicated ACP visit, a first step that can be completed in a reasonably short period would be choosing a surrogate decision-maker.

Helping a patient articulate personal values may be eased by asking such questions as, “Have you ever thought about what kind of care you would want if the time came when you could not make your own decisions?” or “What worries you the most about possibly not being able to make your own decisions?”27 If the patient is able to identify a surrogate decision-maker before the ACP appointment, ask that this person attend. A family member or close friend may remember instances in which the patient expressed health care preferences, and their presence can help to minimize gaps in communication.

Once the patient’s preferences are clear, document them in the medical record. Some preferences may be suitable for translation into POLST orders or an advance directive, but this is less important than the overall discussion. ACP should be an ongoing conversation, since a patient’s goals may change over time. And encourage the patient to share any desired change in plans with their surrogate decision-maker or update the POA document.

BE SURE TO BILL FOR ACP SERVICES

To encourage office-based providers to conduct ACP, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) implemented payment for CPT codes 99497 and 99498.

CPT code 99497 covers the first 30 minutes of face-to-face time with patients or their family members or medical decision-makers. This time can be used to discuss living wills or advance directives.

CPT code 99498 can be applied to each additional 30 minutes of ACP services. Typically, this billing code would be used as an add-on for a particular diagnosis, such as heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or pancreatic cancer.

CPT Code 99497 equates to 2.40 relative-value units (RVU) with an estimated payment of $85.99, while CPT code 99498 equates to 2.09 RVU with an estimated payment of $74.88.28

According to CMS, there is no annual limit to the number of times the ACP codes can be billed for a particular patient. And there are no restrictions regarding location of service, meaning a provider could perform this in an outpatient setting, an inpatient setting, or a long-term care facility. All health care providers are allowed to bill with this code. Also worth noting: You don’t need to complete any particular documentation for a visit to be billed as an ACP service. CMS provides a helpful Q & A at www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/Downloads/FAQ-Advance-Care-Planning.pdf.

With the number of aging Americans projected to grow dramatically in the next several years, the need for primary palliative care and advance care planning (ACP) is more important than ever. Patients and their families want and expect palliative care when needed, but initial conversations about ACP can be difficult for them. Appropriate timing in raising this subject and clear communication can give patients the opportunity, while they are still independent, to set their goals for medical care.

For the past several decades, political decisions and judicial cases have shaped palliative care as we know it today. And its shape is still evolving. In support of ACP, advocacy groups at a national level are developing models that practitioners can use to engage patients in setting goals. And Medicare is now reimbursing primary care providers for this work that they have been doing for years (although many still may not be billing for the service).

Finally, the busy primary care office may have its own set of challenges in addressing ACP. Our aim in this review is to identify the barriers we face and the solutions we can implement to make a difference in our patients’ end-of-life care planning.

LANDMARK EVENTS HAVE DEFINED ACP TODAY

In 1969, Luis Kutner, an Illinois attorney, proposed the idea of a “living will,” envisioned as a document specifying the types of treatment a person would be willing to receive were he or she unable at a later time to participate in making a decision.1 In 1976, California became the first state to give living wills the power of the law through the Natural Death Act.2

Throughout the 1970s and ‘80s, several high-profile court cases brought this idea into the national spotlight. In 1975, the New Jersey Supreme Court granted the parents of 21-year-old Karen Ann Quinlan the right to discontinue the treatment sustaining her in a persistent vegetative state. Ms. Quinlan was removed from the ventilator and lived nine more months before dying in a nursing home.

In 1983, age 25, Nancy Cruzan was involved in a motor vehicle accident that left her in a persistent vegetative state. She remained so until 1988, when her parents asked that her feeding tube be removed. The hospital refused, indicating that it would lead to her death. The family sued, and the case eventually went to the US Supreme Court in 1989.

In a 5-to-4 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that a state was legally able to require “clear and convincing evidence” of a patient’s wish for removal of life-sustaining therapies. Cruzan’s family was able to provide such evidence, and her artificial nutrition was withheld. She died 12 days later.

The Cruzan case was instrumental in furthering ACP, leading to the passage of the Patient Self Determination Act by Congress in 1990. All federally funded health care facilities were now required to educate patients of their rights in determining their medical care and to ask about advance directives.3 The ACP movement gained additional momentum from the landmark SUPPORT study that documented shortcomings in communication between physicians and patients/families about treatment preferences and end-of-life care in US hospitals.4

In the Terri Schiavo case, the patient’s husband disagreed with the life-sustaining decisions of his wife’s parents, given her persistent vegetative state and the fact that she had no chance of meaningful recovery. After a prolonged national debate, it was ultimately decided that the husband could elect to withhold artificial nutrition. (She died in 2005.) The Schiavo case, as well as the Institute of Medicine’s report on Dying in America, influenced Congress in 2016 to pass legislation funding ACP conversations.5

THE DEMONSTRATED BENEFITS OF ACP

When done comprehensively, ACP yields many benefits for patients and families and for the health care system. A systematic review demonstrated that, despite the few studies examining the economic cost of ACP, the process may lead to decreased health care costs in certain populations (nursing home residents, community-dwelling adults with dementia, and those living in high health care–spending regions) and at the very least does not increase health care costs.6 ACP has increased the number of do-not-resuscitate orders and has decreased hospitalizations, admissions to intensive care units, and rates of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, mechanical ventilation, and use of tube feeding.6-8

More noteworthy than the decrease in resource utilization and potential cost savings is the impact that ACP can have on a patient’s quality of life. Patients who receive aggressive care at the end of life tend to experience decreased quality of life compared with those receiving hospice care.7 Quality-of-life scores for patients in hospice improved with the length of enrollment in that care.7 When ACP discussions have taken place, the care patients receive at the end of life tends to conform more closely to their wishes and to increase family satisfaction.9-11

One reason that practitioners often give for not completing ACP is the fear of increasing patient or family anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). However, studies have shown this concern to be unfounded.7,12 While ACP studies have not shown a decrease in rates of anxiety or PTSD, no study has shown an increase in these psychologic morbidities.8

Caveats to keep in mind. Not all studies have shown unambiguous benefits related to ACP. Among the systematic reviews previously noted, there was significant variability in quality of data. Additionally, some experts argue that the traditional view of ACP (ie, completion of a single advance directive/living will) is outdated and should be replaced with a method that prepares patients and families to anticipate “in-the-moment decision making.”13 While we still believe that completion of an advance directive is useful, the experts’ point is well taken, especially since many patients change their preferences over time (and typically toward more aggressive care).14,15 While the advance directive serves a role, it is more important to help patients recognize their goals and preferences and to facilitate ongoing discussions between the patient and his or her family/surrogate decision-maker and providers.

A SNAPSHOT OF PARTICIPATION IN ACP

Despite the ACP movement and the likely benefits associated with it, most individuals have not participated. Rates of completion do seem to be rising, but there is still room for improvement. Among all individuals older than 18, only 26.3% have an advance directive.16 In a cohort of older patients seen in an emergency department, only 40% had a living will, while nearly 54% had a designated health care power of attorney.17 Perhaps more alarming is the lack of ACP for those patients almost all providers would agree need it: the long-term care population. The National Center for Health Statistics has reported that only 28% of home health care patients, 65% of nursing home residents, and 88% of hospice patients have an advance directive on file.18

PROVIDER AND PATIENT BARRIERS TO ACP

If ACP can decrease resource utilization and improve caregiver compliance with a patient’s wishes for end of life, the obvious question is: Why isn’t it done more often? A longstanding barrier for providers has been that these types of discussions are time intensive and have not been billable. However, since January 1, 2016, we are now able to bill for these discussions. (More on this in a bit.) Providers do cite other barriers, though.

A recent systematic review showed that ACP is hindered by time constraints imposed by other clinical and administrative tasks that are heavily monitored.19 Barriers to engaging in ACP reported by patients include a reluctance to think about dying, a belief that family or providers will know what to do, difficulty understanding ACP forms, and the absence of a person who can serve as a surrogate decision-maker.20,21

NATIONAL MODELS TO HELP WITH IMPLEMENTATION

The percentage of individuals with an advance directive in the US has not increased significantly over the past decade.22 The lack of traction in completion and use of advance directives has led several authors to question the utility of this older model of ACP.22 Several experts in the field believe that more robust, ongoing goals-of-care conversations between patients, families, and providers are equally, or even more, important than the completion of actual advance directive documents.23,24

National models such as the POLST (Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment) paradigm have become popular in several states (www.polst.org). Intended for those with estimated life expectancy of less than one year, POLST is not an advance directive but a physician order for these seriously ill patients. Emergency medical service workers are legally able to follow a POLST document but not a living will or advance directive—a significant reason for those with end-stage illness to consider completing a POLST document with their health care provider. Programs such as “Respecting Choices” have incorporated POLST documentation as part of ongoing goals-of-care conversations between patients and health care providers (www.gundersenhealth.org/respecting-choices).

Many groups have developed products to encourage patients and their families to initiate conversations at home. An example is the Conversation Project, a free online resource available in multiple languages that can help break the ice for patients and get them talking about their wishes for end-of-life care (www.theconversationproject.org). It poses simple stimulating questions such as “What kind of role do you want to have in the decision-making process?” and “What are your concerns about treatment?”

HOW-TO TIPS FOR ACP IN OUTPATIENT SETTINGS

When approaching the topic of ACP with patients, it’s important to do so over time, starting as soon as possible with older patients and those with chronic illness that confers a high risk for significant morbidity or mortality. Assess each patient’s understanding of ACP and readiness to discuss the topic. Many patients think of ACP in the context of a document (eg, living will), so asking about the existence of a living will may help to start the conversation. Alternatively, consider inquiring about whether the patient has had experience with family or friends at the end of life or during a difficult medical situation, and whether the patient has thought about making personal plans for such a situation.25

When a patient is ready to have this conversation, your goal should be three-fold:26

- Help the patient articulate personal values, goals, and preferences.

- Ask the patient to formally assign health care power of attorney (POA) to a trusted individual or to name a surrogate decision-maker. Document this decision in the medical record.

- Help the patient translate expressed values into specific medical care plans, if applicable.

Because ACP conversations are often time consuming, it’s a good idea to schedule separate appointments to focus on this alone. If, however, a patient is unable to return for a dedicated ACP visit, a first step that can be completed in a reasonably short period would be choosing a surrogate decision-maker.

Helping a patient articulate personal values may be eased by asking such questions as, “Have you ever thought about what kind of care you would want if the time came when you could not make your own decisions?” or “What worries you the most about possibly not being able to make your own decisions?”27 If the patient is able to identify a surrogate decision-maker before the ACP appointment, ask that this person attend. A family member or close friend may remember instances in which the patient expressed health care preferences, and their presence can help to minimize gaps in communication.

Once the patient’s preferences are clear, document them in the medical record. Some preferences may be suitable for translation into POLST orders or an advance directive, but this is less important than the overall discussion. ACP should be an ongoing conversation, since a patient’s goals may change over time. And encourage the patient to share any desired change in plans with their surrogate decision-maker or update the POA document.

BE SURE TO BILL FOR ACP SERVICES

To encourage office-based providers to conduct ACP, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) implemented payment for CPT codes 99497 and 99498.

CPT code 99497 covers the first 30 minutes of face-to-face time with patients or their family members or medical decision-makers. This time can be used to discuss living wills or advance directives.

CPT code 99498 can be applied to each additional 30 minutes of ACP services. Typically, this billing code would be used as an add-on for a particular diagnosis, such as heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or pancreatic cancer.

CPT Code 99497 equates to 2.40 relative-value units (RVU) with an estimated payment of $85.99, while CPT code 99498 equates to 2.09 RVU with an estimated payment of $74.88.28

According to CMS, there is no annual limit to the number of times the ACP codes can be billed for a particular patient. And there are no restrictions regarding location of service, meaning a provider could perform this in an outpatient setting, an inpatient setting, or a long-term care facility. All health care providers are allowed to bill with this code. Also worth noting: You don’t need to complete any particular documentation for a visit to be billed as an ACP service. CMS provides a helpful Q & A at www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/Downloads/FAQ-Advance-Care-Planning.pdf.

1. Kutner L. Due process of euthanasia: the living will, a proposal. Indiana Law J. 1969;44:539-554.

2. California Law Revision Commission. 2000 Health Care Decisions Law and Revised Power of Attorney Law. www.clrc.ca.gov/pub/Printed-Reports/Pub208.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

3. H.R. 5067 - 101st Congress. Patient Self Determination Act of 1990. www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/101/hr5067. Accessed August 14, 2017.

4. The SUPPORT Principle Investigators. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments (SUPPORT). JAMA. 1995;274:1591-1598.

5. Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2015.

6. Dixon J, Matosevic T, Knapp M. The economic evidence for advance care planning: systematic review of evidence. Palliat Med. 2015;29:869-884.

7. Wright AA, Ray A, Mack JW, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental-health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665-1673.

8. Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens JAC, van der Heide A. The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2014;28:1000-1025.

9. Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, et al. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1345.

10. Morrison RS, Chichin E, Carter J, et al. The effect of a social work intervention to enhance advance care planning documentation in the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:290-294.

11. Schamp R, Tenkku L. Managed death in a PACE: pathways in present and advance directives. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2006;7:339-344.

12. Walczak A, Butow PN, Bu S, et al. A systematic review of evidence for end-of-life communication interventions: who do they target, how are they structured and do they work? Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99:3-16.

13. Sudore RL, Fried TR. Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:256-261.

14. Straton JB, Wang NY, Meoni LA, et al. Physical functioning, depression, and preferences for treatment at the end of life: the Johns Hopkins Precursors study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:577-582.

15. Fried TR, Byers AL, Gallo WT, et al. Prospective study of health status preferences and changes in preferences over time in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:890-895.

16. Rao JK, Anderson LA, Lin F, et al. Completion of advance directives among U.S. consumers. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46:65-70.

17. Grudzen CR, Buonocore P, Steinberg J, et al; AAHPM Research Committee Writing Group. Concordance of advance care plans with inpatient directives in the electronic medical record for older patients admitted from the emergency department. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51:647-651.

18. Jones AL, Moss AJ, Harris-Kojetin LD. Use of advance directives in long-term care populations. NCHS Data Brief. 2011;(54):1-8.

19. Lund S, Richardson A, May C. Barriers to advance care planning at the end of life: an explanatory systematic review of implementation studies. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116629.

20. Fried TR, Bullock K, Iannone L, et al. Understanding advance care planning as a process of health behavior change. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1547-1555.

21. Schickedanz AD, Schillinger D, Landefeld CS, et al. A clinical framework for improving the advance care planning process: start with patients’ self-identified barriers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:31-39.

22. Winter L, Parks SM, Diamond JJ. Ask a different question, get a different answer: why living wills are poor guides to care preferences at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:567-572.

23. Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. www.nap.edu/read/18748/chapter/1. Accessed August 14, 2017.

24. Sudore RL, Schickedanz AD, Landefeld CS, et al. Engagement in multiple steps of the advance care planning process: a descriptive study of diverse older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1006-1013.

25. McMahan RD, Knight SJ, Fried TR, et al. Advance care planning beyond advance directives: perspectives from patients and surrogates. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46:355-365.

26. Lum HD, Sudore RL, Bekelman DB. Advance care planning in the elderly. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99:391-403.

27. Lum HD, Sudore RL. Advance care planning and goals of care communication in older adults with cardiovascular disease and multi-morbidity. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32:247-260.

28. American College of Physicians. Advanced Care Planning: Implementation for practices. www.acponline.org/system/files/documents/practice-resources/business-resources/payment/advance_care_planning_toolkit.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

1. Kutner L. Due process of euthanasia: the living will, a proposal. Indiana Law J. 1969;44:539-554.

2. California Law Revision Commission. 2000 Health Care Decisions Law and Revised Power of Attorney Law. www.clrc.ca.gov/pub/Printed-Reports/Pub208.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.

3. H.R. 5067 - 101st Congress. Patient Self Determination Act of 1990. www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/101/hr5067. Accessed August 14, 2017.

4. The SUPPORT Principle Investigators. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments (SUPPORT). JAMA. 1995;274:1591-1598.

5. Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2015.

6. Dixon J, Matosevic T, Knapp M. The economic evidence for advance care planning: systematic review of evidence. Palliat Med. 2015;29:869-884.

7. Wright AA, Ray A, Mack JW, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental-health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665-1673.

8. Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens JAC, van der Heide A. The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2014;28:1000-1025.

9. Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, et al. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1345.

10. Morrison RS, Chichin E, Carter J, et al. The effect of a social work intervention to enhance advance care planning documentation in the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:290-294.

11. Schamp R, Tenkku L. Managed death in a PACE: pathways in present and advance directives. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2006;7:339-344.

12. Walczak A, Butow PN, Bu S, et al. A systematic review of evidence for end-of-life communication interventions: who do they target, how are they structured and do they work? Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99:3-16.

13. Sudore RL, Fried TR. Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:256-261.

14. Straton JB, Wang NY, Meoni LA, et al. Physical functioning, depression, and preferences for treatment at the end of life: the Johns Hopkins Precursors study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:577-582.

15. Fried TR, Byers AL, Gallo WT, et al. Prospective study of health status preferences and changes in preferences over time in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:890-895.

16. Rao JK, Anderson LA, Lin F, et al. Completion of advance directives among U.S. consumers. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46:65-70.

17. Grudzen CR, Buonocore P, Steinberg J, et al; AAHPM Research Committee Writing Group. Concordance of advance care plans with inpatient directives in the electronic medical record for older patients admitted from the emergency department. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51:647-651.

18. Jones AL, Moss AJ, Harris-Kojetin LD. Use of advance directives in long-term care populations. NCHS Data Brief. 2011;(54):1-8.

19. Lund S, Richardson A, May C. Barriers to advance care planning at the end of life: an explanatory systematic review of implementation studies. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116629.

20. Fried TR, Bullock K, Iannone L, et al. Understanding advance care planning as a process of health behavior change. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1547-1555.

21. Schickedanz AD, Schillinger D, Landefeld CS, et al. A clinical framework for improving the advance care planning process: start with patients’ self-identified barriers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:31-39.

22. Winter L, Parks SM, Diamond JJ. Ask a different question, get a different answer: why living wills are poor guides to care preferences at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:567-572.

23. Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. www.nap.edu/read/18748/chapter/1. Accessed August 14, 2017.

24. Sudore RL, Schickedanz AD, Landefeld CS, et al. Engagement in multiple steps of the advance care planning process: a descriptive study of diverse older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1006-1013.

25. McMahan RD, Knight SJ, Fried TR, et al. Advance care planning beyond advance directives: perspectives from patients and surrogates. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46:355-365.

26. Lum HD, Sudore RL, Bekelman DB. Advance care planning in the elderly. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99:391-403.

27. Lum HD, Sudore RL. Advance care planning and goals of care communication in older adults with cardiovascular disease and multi-morbidity. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32:247-260.

28. American College of Physicians. Advanced Care Planning: Implementation for practices. www.acponline.org/system/files/documents/practice-resources/business-resources/payment/advance_care_planning_toolkit.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2017.