User login

Migraine: Expanding our Tx arsenal

Migraine is a highly disabling primary headache disorder that affects more than 44 million Americans annually.1 The disorder causes pain, photophobia, phonophobia, and nausea that can last for hours, even days. Migraine headaches are 2 times more common in women than in men; although migraine is most common in people 30 to 39 years of age, all ages are affected.2,3 Frequency of migraine headache is variable; chronic migraineurs experience more than 15 headache days a month.

Recent estimates indicate that the cost of acute and chronic migraine headaches reaches approximately $78 million a year in the United States. 4 This high burden of disease has made effective migraine treatment options absolutely essential. Recent advances in our understanding of migraine pathophysiology have led to new therapeutic targets; there are now many novel treatment approaches on the horizon.

In this article, we review the diagnosis and management of migraine in detail. Our emphasis is on evidence-based approaches to acute and prophylactic treatment, including tried-and-true options and newly emerging therapies.

Neuronal dysfunction and a genetic predisposition

Although migraine was once thought to be caused by abnormalities of vasodilation, current research suggests that the disorder has its origins in primary neuronal dysfunction. There appears to be a genetic predisposition toward widespread neuronal hyperexcitability in migraineurs.5 In addition, hypothalamic neurons are thought to initiate migraine by responding to changes in brain homeostasis. Increased parasympathetic tone might activate meningeal pain receptors or lower the threshold for transmitting pain signals from the thalamus to the cortex.6

Prodromal symptoms and aura appear to originate from multiple areas across the brain, including the hypothalamus, cortex, limbic system, and brainstem. This widespread brain involvement might explain why some headache sufferers concurrently experience a variety of symptoms, including fatigue, depression, muscle pain, and an abnormal sensitivity to light, sound, and smell.6,7

Although the exact mechanisms behind each of these symptoms have yet to be defined precisely, waves of neuronal depolarization—known as cortical spreading depression—are suspected to cause migraine aura.8-10 Cortical spreading depression activates the trigeminal pain pathway and leads to the release of pro-inflammatory markers such as calcitonin gene-related protein (CGRP).6 A better understanding of these complex signaling pathways has helped provide potential therapeutic targets for new migraine drugs.

Diagnosis: Close patient inquiry is most helpful

The International Headache Society (IHS) criteria for primary headache disorders serve as the basis for the diagnosis of migraine and its subtypes, which include migraine without aura and migraine with aura. Due to variability of presentation, migraine with aura is further subdivided into migraine with typical aura (with and without headache), migraine with brainstem aura, hemiplegic migraine, and retinal migraine.11

Continue to: How is migraine defined?

How is migraine defined? Simply, migraine is classically defined as a unilateral, pulsating headache of moderate to severe intensity lasting 4 to 72 hours, associated with photophobia and phonophobia or nausea and vomiting, or both.11 Often visual in nature, aura is a set of neurologic symptoms that lasts for minutes and precedes the onset of the headache. The visual aura is often described as a scintillating scotoma that begins near the point of visual fixation and then spreads left or right. Other aura symptoms include tingling or numbness (second most common), speech disturbance (aphasia), motor changes and, in rare cases, a combination of these in succession. By definition, all of these symptoms fully resolve between attacks.11

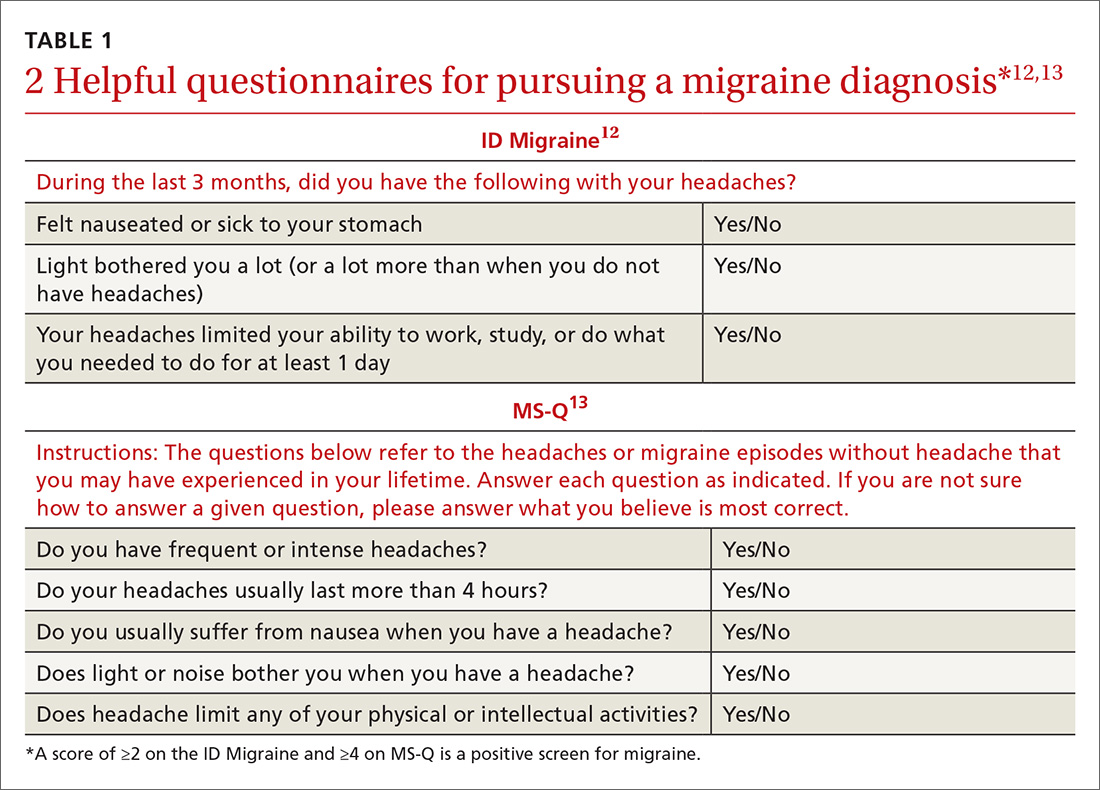

Validated valuable questionnaires. To help with accurate and timely diagnosis, researchers have developed and validated simplified questionnaires that can be completed independently by patients presenting to primary care (TABLE 112,13):

- ID Migraine is a set of 3 questions that scores positive when a patient endorses at least 2 of the 3 symptoms. 12

- MS-Q is similar to the ID Migraine but includes 5 items. A score of ≥4 is a positive screen. 13

The sensitivity and specificity of MS-Q (0.93 and 0.81, respectively) are slightly higher than those of ID Migraine (0.81 and 0.75).13

Remember POUND. This mnemonic device can also be used during history-taking to aid in diagnostic accuracy. Migraine is highly likely (92%) in patients who endorse 4 of the following 5 symptoms and unlikely (17%) in those who endorse ≤2 symptoms14: Pulsatile quality of headache 4 to 72 hOurs in duration, Unilateral location, Nausea or vomiting, and Disabling intensity.

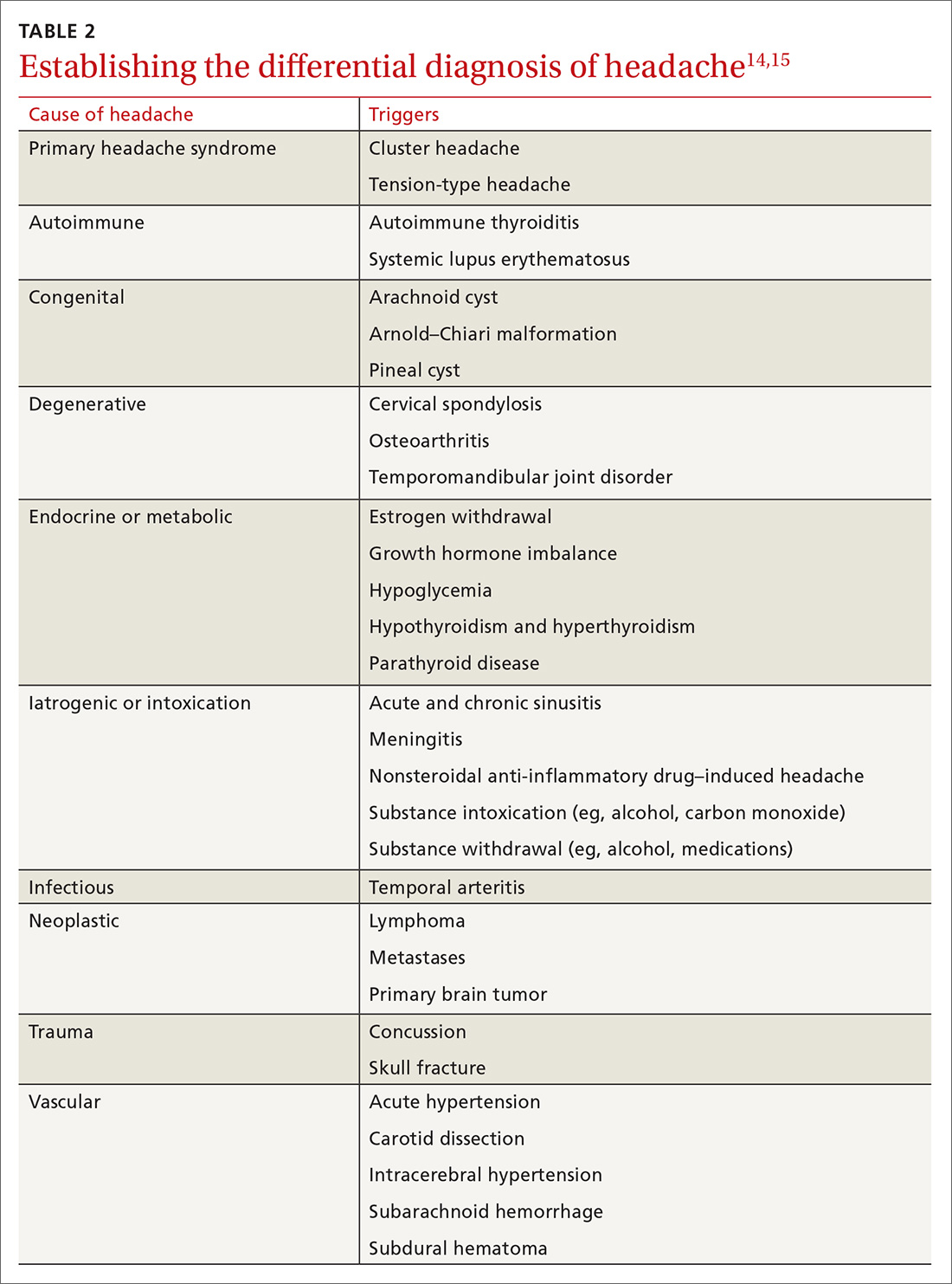

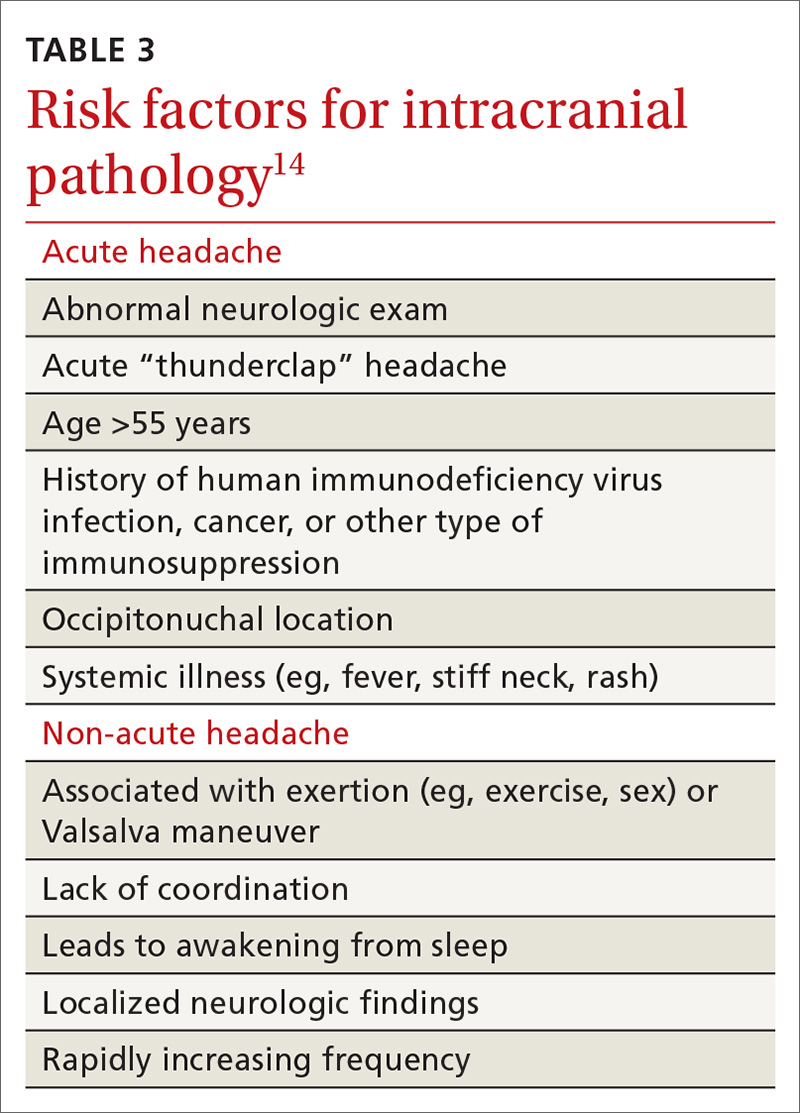

Differential Dx. Although the differential diagnosis of headache is broad (TABLE 214,15), the history alone can often guide clinicians towards the correct assessment. After taking the initial history (headache onset, location, duration, and associated symptoms), focus your attention on assessing the risk of intracranial pathology. This is best accomplished by assessing specific details of the history (TABLE 314) and findings on physical examination15:

- blood pressure measurement (seated, legs uncrossed, feet flat on the floor; having rested for 5 minutes; arm well supported)

- cranial nerve exam

- extremity strength testing

- eye exam (vision, extra-ocular muscles, visual fields, pupillary reactivity, and funduscopic exam)

- gait (tandem walk)

- reflexes.

Continue to: Further testing needed?

Further testing needed? Neuroimaging should be considered only in patients with an abnormal neurologic exam, atypical headache features, or certain risk factors, such as an immune deficiency. There is no role for electroencephalography or other diagnostic testing in migraine.16

Take a multipronged approach to treatment

As with other complex, chronic conditions, the treatment of migraine should take a multifaceted approach, including management of acute symptoms as well as prevention of future headaches. In 2015, the American Headache Society published a systematic review that specified particular treatment goals for migraine sufferers. 17 These goals include:

- headache reduction

- headache relief

- decreased disability from headache

- elimination of nausea and vomiting

- elimination of photophobia and phonophobia.

Our review, which follows, of therapeutic options focuses on the management of migraine in adults. Approaches in special populations (older adults, pregnant women, and children) are discussed afterward.

Pharmacotherapy for acute migraine

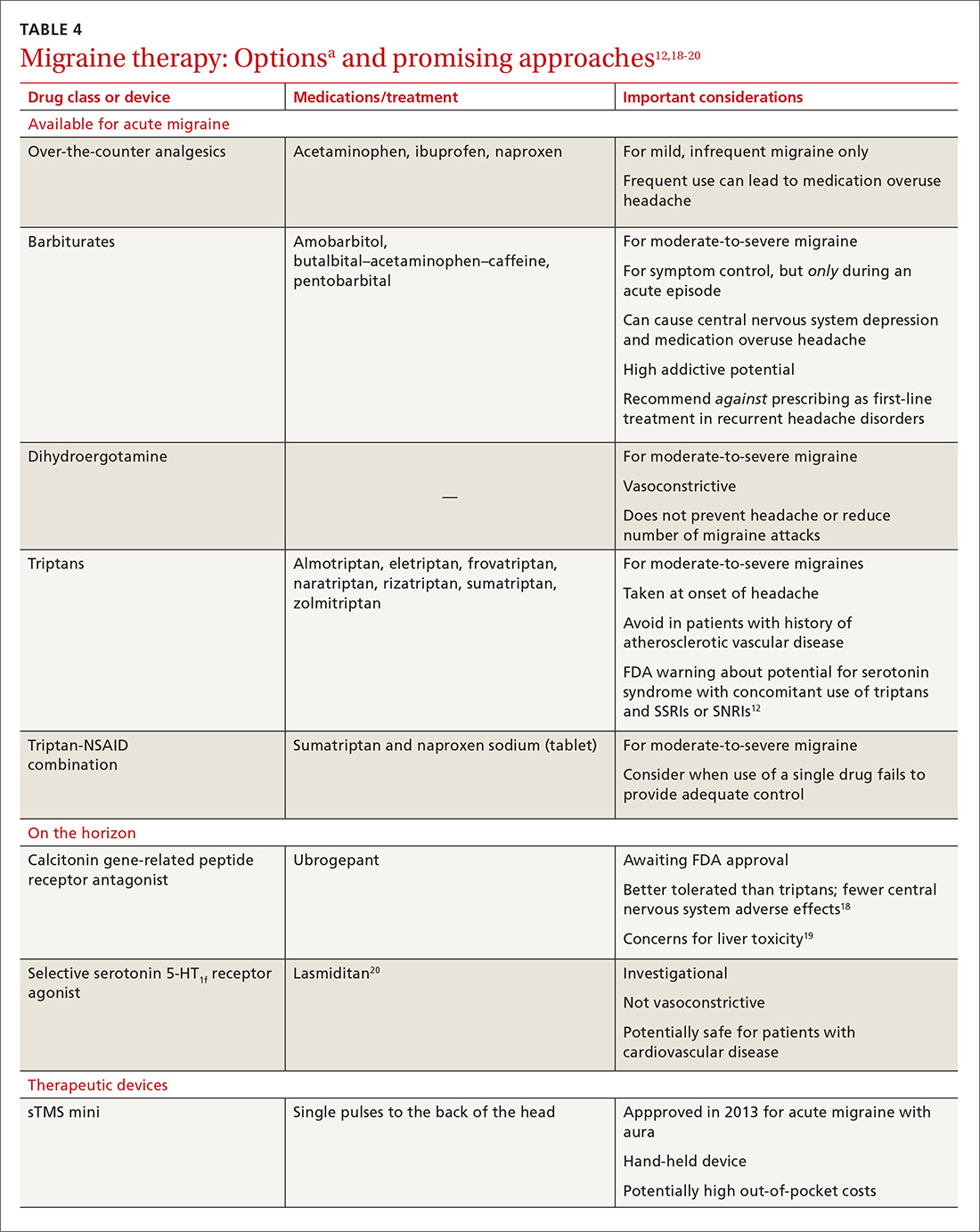

Acute migraine should be treated with an abortive medication at the onset of headache. The immediate goal is to relieve pain within 2 hours and prevent its recurrence within the subsequent 48 hours (TABLE 412,18-20).

In the general population, mild, infrequent migraines can be managed with acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).21

Continue to: For moderate-to-severe migraine...

For moderate-to-severe migraine, triptans, which target serotonin receptors, are the drug of choice for most patients.21 Triptans are superior to placebo in achieving a pain-free state at 2 and 24 hours after administration; eletriptan has the most desirable outcome, with 68% of patients pain free at 2 hours and 54% pain free at 24 hours.22 Triptans are available as sublingual tablets and nasal sprays, as well as subcutaneous injections for patients with significant associated nausea and vomiting. Avoid prescribing triptans for patients with known vascular disease (eg, history of stroke, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, uncontrolled hypertension, or signs and symptoms of these conditions), as well as for patients with severe hepatic impairment.

Importantly, although triptans all have a similar mechanism of action, patients might respond differently to different drugs within the class. If a patient does not get adequate headache relief from an appropriate dosage of a given triptan during a particular migraine episode, a different triptan can be tried during the next migraine.22 Additionally, if a patient experiences an adverse effect from one triptan, this does not necessarily mean that a trial of another triptan at a later time is contraindicated.

For patients who have an incomplete response to migraine treatment or for those with frequent recurrence, the combination formulation of sumatriptan, 85 mg, and naproxen, 500 mg, showed the highest rate of resolution of headache within 2 hours compared with either drug alone.23 A similar result might be found by combining a triptan known to be effective for a patient and an NSAID other than naproxen. If migraine persists despite initial treatment of an attack, a different class of medication should be tried during the course of that attack to attain relief of symptoms of that migraine.21

When a patient is seen in an acute care setting (eg, emergency department, urgent care center) while suffering a migraine, additional treatment options are available. Intravenous (IV) anti-emetics are useful for relieving the pain of migraine and nausea, and can be used in combination with an IV NSAID (eg, ketorolac).21 The most effective anti-emetics are dopamine receptor type-2 blockers, including chlorpromazine, droperidol, metoclopramide, and prochlorperazine, which has the highest level of efficacy.24 Note that these medications do present the risk of a dystonic reaction; diphenhydramine is therefore often used in tandem to mitigate such a response.

Looking ahead. Although triptans are the current first-line therapy for acute migraine, their effectiveness is limited. Only 20% of patients report sustained relief of pain in the 2 to 24 hours after treatment, and the response can vary from episode to episode.25

Continue to: With better understading of the pathophysiology of migraine...

With better understanding of the pathophysiology of migraine, a host of novel anti-migraine drugs are on the horizon.

CGRP receptor antagonists. The neuropeptide CGRP, which mediates central and peripheral nervous system pain signaling, has been noted to be elevated during acute migraine attacks26; clinical trials are therefore underway to evaluate the safety and efficacy of CGRP receptor antagonists.18 These agents appear to be better tolerated than triptans, have fewer vascular and central nervous system adverse effects, and present less of a risk of medication overuse headache.18 Liver toxicity has been seen with some medications in this class and remains an important concern in their development.19

Phase 3 clinical trials for 1 drug in this class, ubrogepant, were completed in late 2017; full analysis of the data is not yet available. Primary outcomes being evaluated include relief of pain at 2 hours and relief from the most bothersome symptoms again at 2 hours.27

Selective serotonin-HT1f receptor agonists, such as lasmiditan, offer another potential approach. Although the exact mechanism of action of these agents is not entirely clear, clinical trials have supported their efficacy and safety.20 Importantly, ongoing trials are specifically targeting patients with known cardiovascular risk factors because they are most likely to benefit from the nonvasoconstrictive mechanism of action.28,29 Adverse effects reported primarily include dizziness, fatigue, and vertigo.

Strategies for managing recurrent episodic migraine

Because of the risk of medication overuse headache with acute treatment, daily preventive therapy for migraine is indicated for any patient with 30 :

- ≥6 headache days a month

- ≥4 headache days a month with some impairment

- ≥3 headache days a month with severe impairment.

Continue to: Treatment begins by having patients identify...

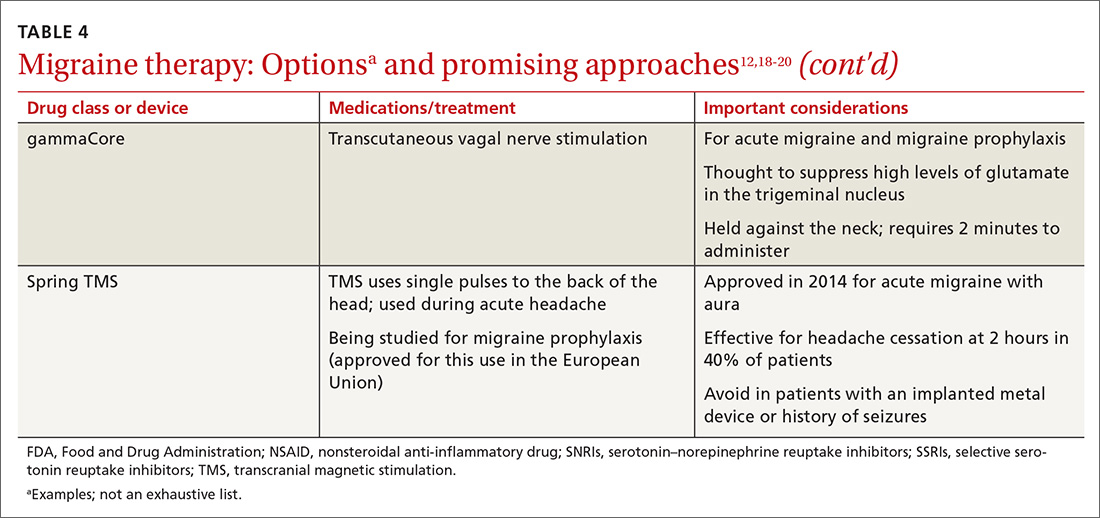

Treatment begins by having patients identify, and then avoid, migraine triggers (TABLE 5). This can be accomplished by having patients keep a headache diary, in which they can enter notations about personal and environmental situations that precede a headache.

For the individual patient, some triggers are modifiable; others are not. Helping a patient develop strategies for coping with triggers, rather than aiming for complete avoidance, might help her (him) manage those that are inescapable (eg stress, menstruation, etc).31 For many patients, however, this is not an adequate intervention and other approaches must be explored. When considering which therapy might be best for a given patient, evaluate her (his) comorbidities and assess that particular treatment for potential secondary benefits and the possibility of adverse effects. Pay attention to the choice of preventive therapy in women who are considering pregnancy because many available treatments are potentially teratogenic.

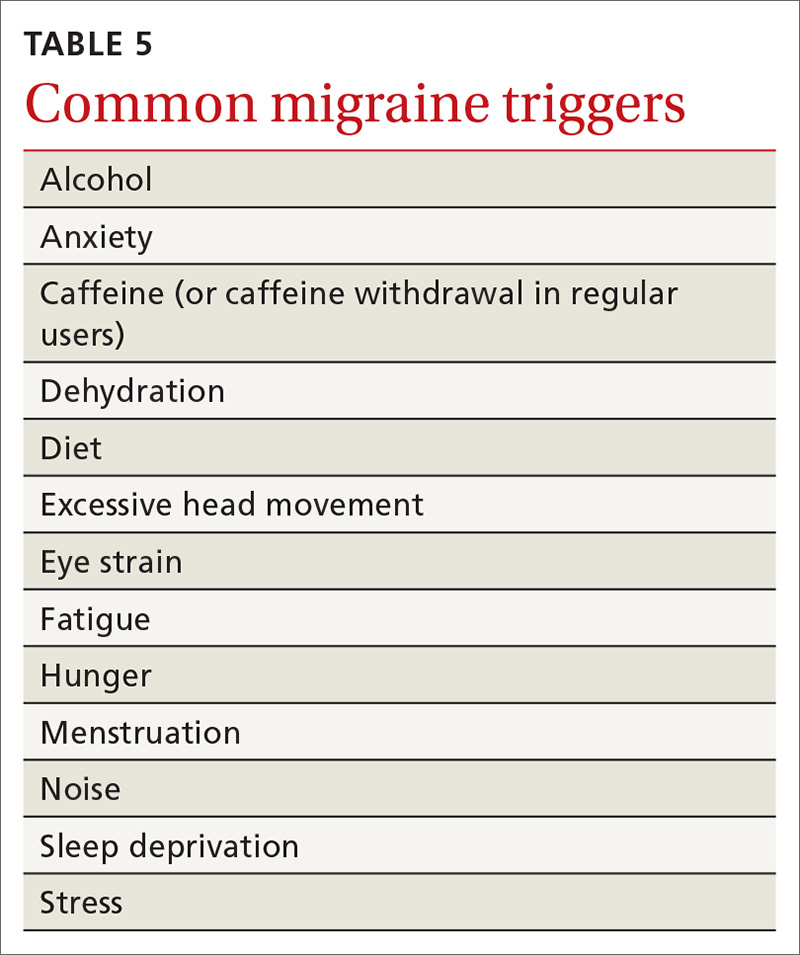

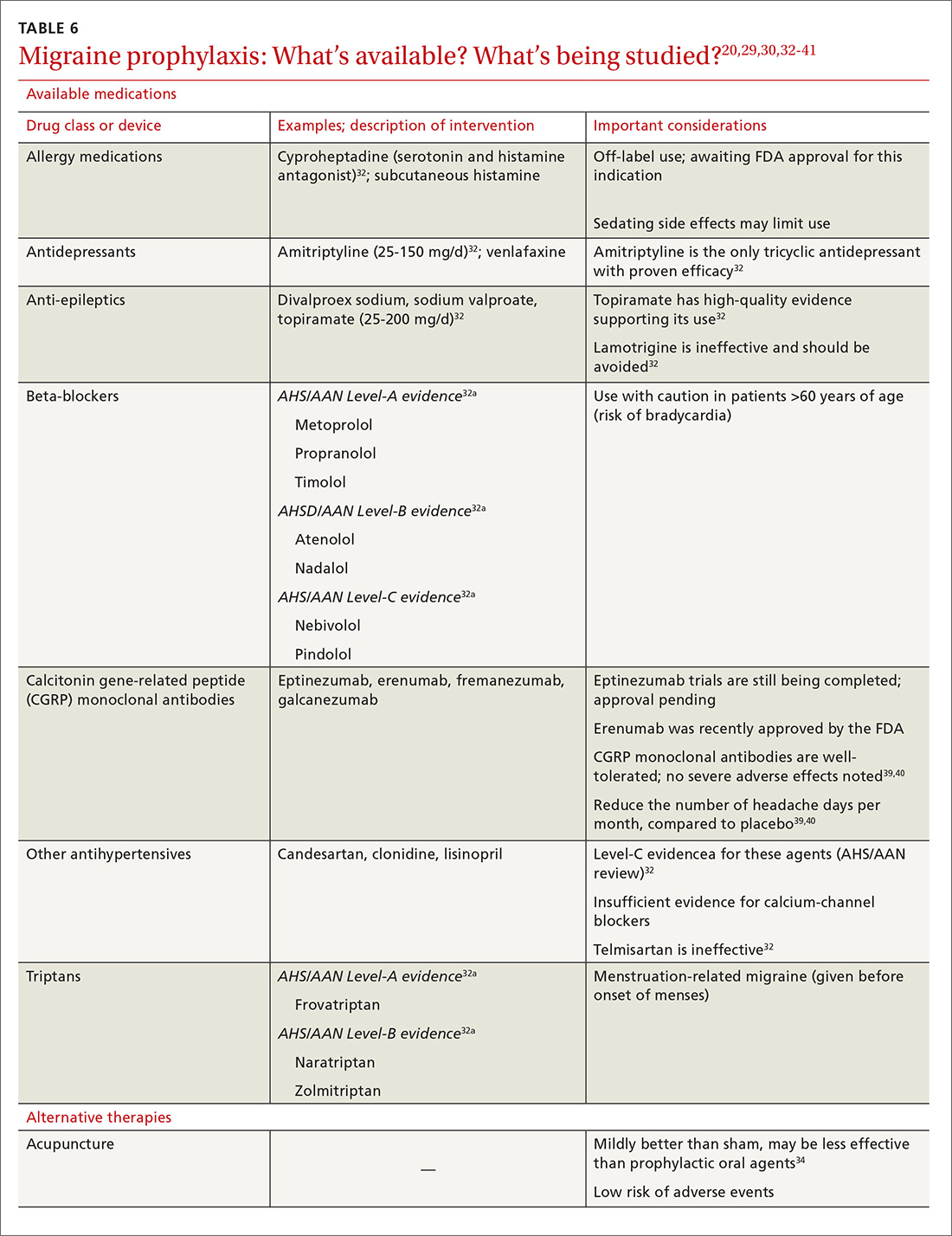

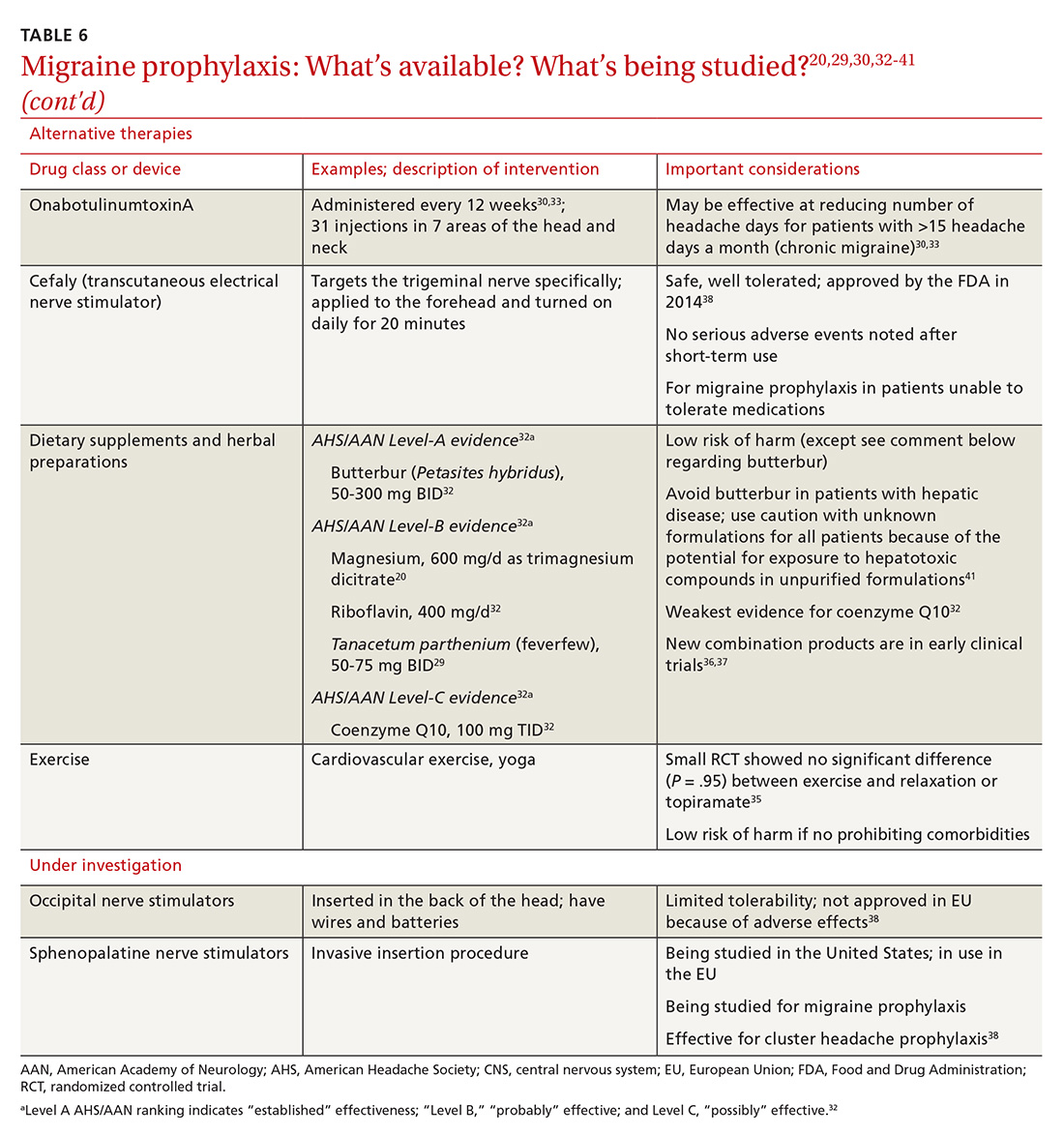

Oral medications. Oral agents from several classes of drugs can be used for migraine prophylaxis, including anti-epileptics,antidepressants, and antihypertensives (TABLE 620,29,30,32-41). Selected anti-epileptics (divalproex sodium, sodium valproate, topiramate) and beta-blockers (metoprolol, propranolol, and timolol) have the strongest evidence to support their use.32 Overall, regular use of prophylactic medications can reduce headache frequency by 50% for approximately 40% to 45% of patients who take them.29 However, adherence may be limited by adverse effects or perceived lack of efficacy, thus reducing their potential for benefit.42

OnabotulinumtoxinA. In patients with chronic migraine (≥15 headache days a month for at least 3 months) who have failed oral medications, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) recommends the use of onabotulinumtoxinA.30 The treatment regimen comprises 31 injections at various sites on the head, neck, and shoulders every 3 months.33

A 2010 large randomized controlled trial showed a decrease in the frequency of headache days for patients receiving onabotulinumtoxinA compared to placebo after a 24-week treatment period (7.8 fewer headache days a month, compared to 6.4 fewer in the placebo group).33 A recent systematic review also noted a reduction of 2 headache days a month compared with placebo; the authors cautioned, however, that data with which to evaluate onabotulinumtoxinA in comparison to other prophylactic agents are limited.43

Continue to: In both studies...

In both studies, the risk of adverse drug events due to onabotulinumtoxinA was high and led to a significant rate of discontinuation.33,43 Despite this, onabotulinumtoxinA remains the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved treatment for chronic migraine, making it reasonable to consider for appropriate patients.

Acupuncture. A 2016 Cochrane review found benefit for patients using acupuncture compared with sham acupuncture.34 When acupuncture was compared with prophylactic agents such as beta-blockers, calcium-channel blockers, and anti-epileptics, however, there was no significant difference between the procedure and pharmacotherapy. Patients willing and able to try acupuncture might see a reduction in the overall number of headaches. Acupuncture has few adverse effects; however, long-term data are lacking.34

Exercise is not supported by robust data for its role as a prophylactic treatment. It is generally considered safe in most populations, however, and can be pursued with little out-of-pocket cost.35

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). The AAN recommends CBT, relaxation therapy, and biofeedback therapy. Accessibility of these services remains limited for many patients, and cost can be prohibitive.16

Supplements used to help prevent migraine include the root of Petasites hybridus (butterbur), magnesium, vitamin B2 (riboflavin), Tanacetum parthenium (feverfew), and coenzyme Q10.16 Although the strength of evidence for these therapies is limited by small trials, their overall risk of adverse effects is low, and they might be easier for patients to obtain than acupuncture or CBT.

Continue to: Butterbur, in particular...

Butterbur, in particular, has been found to be beneficial for migraine prevention in 2 small placebo-controlled trials. In a randomized controlled study of 245 patients P hybridus, (specifically, the German formulation, Petadolex), 75 mg BID, reduced the frequency of migraine attack by 48% at 4 months, compared to placebo (number needed to treat, 5.3).44 No difference was found at lower dosages. The most common reported adverse effect was burping.

Regrettably, unpurified butterbur extract contains pyrrolizidine alkaloids, potentially hepatotoxic and carcinogenic compounds. Because of variations in purification in production facilities in the United States, butterbur supplements might not have all of these compounds removed—and so should be used with caution.41

Magnesium. Studies evaluating the use of magnesium have demonstrated varied results; differences in methods and dosing have limited broad application of findings. As with most supplements considered for prophylactic treatment, magnesium dosing is poorly understood, and bioavailability varies in its different forms. Oral supplementation can be given as magnesium dicitrate, 600 mg/d.45

Recently, products containing various combinations of feverfew, coenzyme Q10, riboflavin, magnesium, and other supplements have shown benefit in early clinical trials.36,37

Neural stimulation. Over the past few years, a variety of transcutaneous nerve stimulator devices have gained FDA approval for use in migraine prophylaxis. The long-term safety and efficacy of these devices is not yet well understood, but they appear to provide headache relief in the short term and decrease the frequency of headache.38 Use of the noninvasive stimulators is limited today by high cost and poor coverage by US health care insurers.

Continue to: Newly available medical therapy

Newly available medical therapy. The FDA recently approved erenumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody for prevention of migraine in adults. This is the first drug in the CGRP antagonist class to be approved for this indication. Trials of this once-monthly, self-injectable drug show promising results for patients whose migraines have been refractory to other therapies.

A recent large trial evaluated 955 adults with migraine, randomizing them to receive erenumab, 70 mg; erenumab, 140 mg; or placebo over 28 weeks.39 The groups receiving erenumab had a nearly 2-fold higher odds of having their migraine reduced by 50%, compared with placebo (number needed to treat with the 140-mg dose, 4.27). Similar numbers of participants from all groups discontinued the study.39 Phase 3 trials that are not yet formally published have produced similarly beneficial results.40,46 The FDA has listed injection site reaction and constipation as the most reported adverse effects.40

Three other anti-CGRP antibodies are likely to be approved in the near future: fremanezumab, galcanezumab, and eptinezumab.

The approach to migraine in special populations

Management of acute and chronic migraine in children, pregnant women, and older adults requires special attention: Treatment approaches are different than they are for adults 19 to 65 years of age.

Pediatric patients. Migraine is the most common acute and recurrent headache syndrome in children. Headaches differ from those of adult migraine as a result of variations in brain maturation, plasticity, and cognitive development.47 Migraine attacks are often of shorter duration in children, lasting 1 to 2 hours, but can still be preceded by visual aura.48 Just as with adults, imaging, electroencephalography, lumbar puncture, and routine labs should be considered only if a child has an abnormal neurological exam or other concerning features (TABLE 214,15).

Continue to: The general approach to migraine treatment...

The general approach to migraine treatment in the pediatric population includes education of the child and family about symptom management. Acetaminophen, NSAIDs, and triptans are approved for abortive therapy in children and should be used for acute headache relief in the same way that they are used in adults. Oral rizatriptan, the most well studied triptan in the pediatric population, is approved for use in children as young as 6 years49; the pediatric dosage is 5 mg/d for patients weighing 20 to 39 kg and 10 mg/d for patients weighing more than 40 kg (same as the adult dosage).

Oral almotriptan and zolmitriptan are also approved for use in children 12 to 17 years of age. Usual dosages are: almotriptan, 12.5 mg at onset, can repeat in 2 hours as needed (maximum dosage, 25 mg/d); and zolmitriptan, 2.5 mg at onset, can repeat in 2 hours as needed (maximum dosage, 10 mg/d).50

For children who are unable to swallow pills or who are vomiting, a non-oral route of administration is preferable. Rizatriptan is available as an orally disintegrating tablet. Zolmitriptan is available in a nasal spray at a dose of 5 mg for children 12 years and older. Sumatriptan is not approved for use in patients younger than 18 years; however, recent studies have shown that it might have good efficacy and tolerability.50

Daily prophylactic treatment for recurrent migraine in the pediatric population is an evolving subject; published guidelines do not exist. It is reasonable to consider treatment using the same guidelines as those in place for adults.51 Topiramate, 1 to 2 mg/kg/d, is the only therapy approved by the FDA for episodic migraine preventive therapy in adolescents.50

Notably, a nonpharmacotherapeutic approach may be more effective for pediatric prevention. In 2017, a large double-blind, placebo-controlled trial investigated the use of amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo for the treatment of recurrent migraine in children 8 to 17 years of age. An interim analysis of the 328 children enrolled found no significant differences in reduction of headache frequency with treatment compared with placebo over a 24-week period; the trial was stopped early due to futility.52

Continue to: The study did show...

The study did show, however, that reducing migraine triggers provided a high level of benefit to study participants. Stress is one of the most common migraine triggers in children; lack of sleep, exposure to a warm climate, and exposure to video games are also notable triggers.53 CBT may augment the efficacy of standard migraine medications in the pediatric population and may help prevent recurrence of episodes.54

Pregnancy. The treatment of migraine is different in pregnant women than it is in nonpregnant adults because of a concern over adverse effects on fetal development. For acute headache treatment, first-line therapies include trigger avoidance and acetaminophen, 1000 mg (maximum dosage, 4000 mg/d).55 If this is ineffective, a 10-mg dose of metoclopramide, as often as every 6 hours (not an FDA-approved indication), can be considered. During the second trimester, NSAIDs can be considered second-line therapy.

Triptans—specifically, sumatriptan and rizatriptan—can also be considered if first-line therapies fail.56 Triptan-exposed pregnant women with migraine have a rate of congenital malformations, spontaneous abortions, and prematurity that is similar to what is seen in pregnant women with migraine who have not been exposed to triptans. However, when triptan-exposed women are compared with healthy, non-migraine-suffering women, the rate of spontaneous abortion appears to be increased in the triptan-exposed population.57

Ergotamine is contraindicated during pregnancy because of its potential to induce uterine contractions and vasospasm, which can be detrimental to the fetus.56Nonpharmacotherapeutic interventions such as heat, ice, massage, rest, and avoidance of triggers are as successful in the pregnant population as in the nonpregnant population. For migraine prevention, coenzyme Q10, vitamins B2 and B6 (pyridoxine), and oral magnesium can be considered. Feverfew and butterbur should be avoided because of concerns about fetal malformation and preterm labor.58

Older adults. Choosing appropriate migraine therapy for older adults requires special consideration because of changes in drug metabolism and risks associated with drug adverse effects. Additionally, few studies of migraine drugs have included large populations of adults older than 65 years; medications should therefore be prescribed cautiously in this population, with particular attention to drug–drug interactions.

Continue to: Just as for younger adults...

Just as for younger adults, mild symptoms can be managed effectively with acetaminophen. NSAIDs may be used as well, but carry increased risks of gastric bleeding and elevation in blood pressure.59 The use of triptans is acceptable for the appropriate patient, but should be avoided in patients with known vascular disease.60 Antiemetics present an increased risk of extrapyramidal adverse effects in the elderly and should be used with caution at the lowest effective dosage.59 Novel mechanisms of action make some of the newer agents potentially safer for use in older adults when treating acute migraine.

For migraine prevention in older adults, particular attention should be paid to reducing triggers and minimizing polypharmacy.

More and more, successful treatment is within reach

With many clinical trials evaluating novel drugs underway, and additional studies contributing to our understanding of nonpharmacotherapeutic approaches to migraine treatment, improved headache control may become increasingly common over the next few years.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kathryn McGrath, MD, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Thomas Jefferson University, 1015 Walnut St, Philadelphia PA 19107; Kathryn.mcgrath@jefferson.edu.

1. Stokes M, Becker WJ, Lipton RB, et al. Cost of health care among patients with chronic and episodic migraine in Canada and the USA: results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). Headache. 2011;51:1058-1077.

2. Smitherman TA, Burch R, Sheikh H, et al. The prevalence, impact, and treatment of migraine and severe headaches in the United States: a review of statistics from national surveillance studies. Headache. 2013;53:427-436.

3. Burch RC, Loder S, Loder E, et al. The prevalence and burden of migraine and severe headache in the United States: updated statistics from government health surveillance studies. Headache. 2015;55:21-34.

4. Gooch CL, Pracht E, Borenstein AR. The burden of neurological disease in the United States: a summary report and call to action. Ann Neurol. 2017;81:479-484.

5. Ferrari MD, Klever RR, Terwindt GM, et al. Migraine pathophysiology: lessons from mouse models and human genetics. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:65-80.

6. Burstein R, Noseda R, Borsook D. Migraine: multiple processes, complex pathophysiology. J Neurosc. 2015;35:6619-6629.

7. Maniyar FH, Sprenger T, Monteith T, et al. Brain activations in the premonitory phase of nitroglycerin-triggered migraine attacks. Brain. 2013;137(Pt 1):232-241.

8. Cutrer FM, Sorensen AG, Weisskoff RM, et al. Perfusion‐weighted imaging defects during spontaneous migrainous aura. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:25-31.

9. Hadjikhani N, Sanchez Del Rio MS, Wu O, et al. Mechanisms of migraine aura revealed by functional MRI in human visual cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:4687-4692.

10. Pietrobon D, Moskowitz MA. Pathophysiology of migraine. Ann Rev Physiol. 2013;75:365-391.

11. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33:629-808.

12. Lipton RB, Dodick D, Sadovsky RE, et al; ID Migraine validation study. A self-administered screener for migraine in primary care: The ID Migraine™ validation study. Neurology. 2003;61:375-382.

13. Láinez MJ, Domínguez M, Rejas J, et al. Development and validation of the Migraine Screen Questionnaire (MS‐Q). Headache. 2005;45:1328-1338.

14. Detsky ME, McDonald DR, Baerlocher MO, et al. Does this patient with headache have a migraine or need neuroimaging? JAMA. 2006;296:1274-1283.

15. Becker WJ, Findlay T, Moga C, et al. Guideline for primary care management of headache in adults. Can Fam Physician. 2015;61:670-679.

16. Silberstein SD. Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000;55:754-762.

17. Marmura MJ, Silberstein SD, Schwedt TJ. The acute treatment of migraine in adults: the American Headache Society evidence assessment of migraine pharmacotherapies. Headache. 2015;55:3-20.

18. Voss T, Lipton RB, Dodick DW, et al. A phase IIb randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ubrogepant for the acute treatment of migraine. Cephalalgia. 2016;36:887-898.

19. Russo AF. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP): a new target for migraine. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;55:533-552.

20. Färkkilä M, Diener HC, Géraud G, et al; COL MIG-202 study group. Efficacy and tolerability of lasmiditan, an oral 5-HT(1F) receptor agonist, for the acute treatment of migraine: a phase 2 randomised, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, dose-ranging study. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:405-413.

21. Pringsheim T, Davenport WJ, Marmura MJ, et al. How to apply the AHS evidence assessment of the acute treatment of migraine in adults to your patient with migraine. Headache. 2016;56:1194-1200.

22. Thorlund K, Mills EJ, Wu P, et al. Comparative efficacy of triptans for the abortive treatment of migraine: a multiple treatment comparison meta-analysis. Cephalalgia. 2014;34:258-267.

23. Law S, Derry S, Moore RA. Sumatriptan plus naproxen for acute migraine attacks in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(10):CD008541.

24. Orr SL, Aubé M, Becker WJ, et al. Canadian Headache Society systematic review and recommendations on the treatment of migraine pain in emergency settings. Cephalalgia. 2015;35:271-284.

25. Ferrari MD, Goadsby PJ, Roon KI, et al. Triptans (serotonin, 5‐HT1B/1D agonists) in migraine: detailed results and methods of a meta‐analysis of 53 trials. Cephalalgia. 2002;22:633-658.

26. Goadsby PJ, Edvinsson L. The trigeminovascular system and migraine: studies characterizing cerebrovascular and neuropeptide changes seen in humans and cats. Ann Neurol. 1993;33:48-56.

27. A phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled single attack study to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of oral ubrogepant in the acute treatment of migraine. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT02828020. Accessed November 16, 2018.

28. Rubio-Beltrán E, Labastida-Ramírez A, Villalón CM, et al. Is selective 5-HT1F receptor agonism an entity apart from that of the triptans in antimigraine therapy? Pharmacol Ther. 2018;186:88-97.

29. Diener HC, Charles A, Goadsby PJ, et al. New therapeutic approaches for the prevention and treatment of migraine. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:1010-1022.

30. Lipton RB, Silberstein SD. Episodic and chronic migraine headache: breaking down barriers to optimal treatment and prevention. Headache. 2015;55 Suppl 2:103-122.

31. Martin PR. Behavioral management of migraine headache triggers: learning to cope with triggers. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2010;14:221-227.

32. Loder E, Burch R, Rizzoli P. The 2012 AHS/AAN guidelines for prevention of episodic migraine: a summary and comparison with other recent clinical practice guidelines. Headache. 2012;52:930-945.

33. Dodick DW, Turkel CC, DeGryse RE, et al; PREEMPT Chronic Migraine Study Group. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: pooled results from the double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled phases of the PREEMPT clinical program. Headache. 2010;50:921-936.

34. Linde K, Allais G, Brinkhaus B, et al. Acupuncture for the prevention of episodic migraine. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016(6):CD001218.

35. Varkey E, Cider Å, Carlsson J, et al. Exercise as migraine prophylaxis: a randomized study using relaxation and topiramate as controls. Cephalalgia. 2011;31:1428-1438.

36. Guilbot A, Bangratz M, Abdellah SA, et al. A combination of coenzyme Q10, feverfew and magnesium for migraine prophylaxis: a prospective observational study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17:433.

37. Dalla Volta G, Zavarize P, Ngonga G, et al. Combination of Tanacethum partenium, 5-hydrossitriptophan (5-Http) and magnesium in the prophylaxis of episodic migraine without aura (AURASTOP®) an observational study. Int J Neuro Brain Dis. 2017;4:1-4.

38. Puledda F, Goadsby PJ. An update on non‐pharmacological neuromodulation for the acute and preventive treatment of migraine. Headache. 2017;57:685-691.

39. Goadsby PJ, Reuter U, Hallström Y, et al. A controlled trial of erenumab for episodic migraine. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2123-2132.

40. Reuter U. Efficacy and safety of erenumab in episodic migraine patients with 2-4 prior preventive treatment failures: Results from the Phase 3b LIBERTY study. Abstract 009, AAN 2018 Annual Meeting; April 24, 2018.

41. Diener HC, Freitag FG, Danesch U. Safety profile of a special butterbur extract from Petasites hybridus in migraine prevention with emphasis on the liver. Cephalalgia Reports. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2515816318759304. 2018 May 2. Accessed December 15, 2018.

42. Kingston WS, Halker R. Determinants of suboptimal migraine diagnosis and treatment in the primary care setting. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2017;24:319-324.

43. Herd CP, Tomlinson CL, Rick C, et al. Botulinum toxins for the prevention of migraine in adults. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD011616.

44. Lipton RB, Göbel H, Einhäupl KM, et al. Petasites hybridus root (butterbur) is an effective preventive treatment for migraine. Neurology. 2004;63:2240-2244.

45. Von Luckner A, Riederer F. Magnesium in migraine prophylaxis—is there an evidence‐based rationale? A systematic review. Headache. 2018;58:199-209.

46. Tepper S, Ashina M, Reuter U, et al. Safety and efficacy of erenumab for preventive treatment of chronic migraine: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:425-434.

47. Sonal Sekhar M, Sasidharan S, Joseph S, et al. Migraine management: How do the adult and paediatric migraines differ? Saudi Pharm J. 2012;20:1-7.

48. Lewis DW. Pediatric migraine. In: Lewis DW. Clinician’s Manual on Treatment of Pediatric Migraine. London, UK: Springer Healthcare Ltd; 2010:15-26.

49. Ho TW, Pearlman E, Lewis D, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of rizatriptan in pediatric migraineurs: results from a randomized double-blind, placebo controlled trial using a novel adaptive enrichment design. Cephalagia. 2012;32:750-765.

50. Khrizman M, Pakalnis A. Management of pediatric migraine: current therapies. Pediatr Ann. 2018;47:e55-e60.

51. Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al; AMPP Advisory Group. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68:343-349.

52. Powers SW, Coffey CS, Chamberlin LA, et al; CHAMP Investigators. Trial of amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo for pediatric migraine. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:115-124.

53. Neut D, Fily A, Cuvellier JC, et al. The prevalence of triggers in paediatric migraine: a questionnaire study in 102 children and adolescents. J Headache Pain. 2012;13:61-65.

54. Ng QX, Venkatanarayanan N, Kumar L. A systematic review and meta‐analysis of the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for the management of pediatric migraine. Headache. s2017;57:349-362.

55. Lipton RB, Baggish JS, Stewart WF, et al. Efficacy and safety of acetaminophen in the treatment of migraine: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3486-3492.

56. Lucas S. Medication use in the treatment of migraine during pregnancy and lactation. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2009;13:392-398.

57. Marchenko A, Etwel F, Olutunfesse O, et al. Pregnancy outcome following prenatal exposure to triptan medications: a meta-analysis. Headache. 2015:55:490-501.

58. Wells RE, Turner DP, Lee M, et al. Managing migraine during pregnancy and lactation. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2016;16:40.

59. Haan J, Hollander J, Ferrari MD. Migraine in the elderly: a review. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:97-106.

60. Gladstone JP, Eross EJ, Dodick DW. Migraine in special populations. Treatment strategies for children and adolescents, pregnant women, and the elderly. Postgrad Med. 2004;115:39-44,47-50.

Migraine is a highly disabling primary headache disorder that affects more than 44 million Americans annually.1 The disorder causes pain, photophobia, phonophobia, and nausea that can last for hours, even days. Migraine headaches are 2 times more common in women than in men; although migraine is most common in people 30 to 39 years of age, all ages are affected.2,3 Frequency of migraine headache is variable; chronic migraineurs experience more than 15 headache days a month.

Recent estimates indicate that the cost of acute and chronic migraine headaches reaches approximately $78 million a year in the United States. 4 This high burden of disease has made effective migraine treatment options absolutely essential. Recent advances in our understanding of migraine pathophysiology have led to new therapeutic targets; there are now many novel treatment approaches on the horizon.

In this article, we review the diagnosis and management of migraine in detail. Our emphasis is on evidence-based approaches to acute and prophylactic treatment, including tried-and-true options and newly emerging therapies.

Neuronal dysfunction and a genetic predisposition

Although migraine was once thought to be caused by abnormalities of vasodilation, current research suggests that the disorder has its origins in primary neuronal dysfunction. There appears to be a genetic predisposition toward widespread neuronal hyperexcitability in migraineurs.5 In addition, hypothalamic neurons are thought to initiate migraine by responding to changes in brain homeostasis. Increased parasympathetic tone might activate meningeal pain receptors or lower the threshold for transmitting pain signals from the thalamus to the cortex.6

Prodromal symptoms and aura appear to originate from multiple areas across the brain, including the hypothalamus, cortex, limbic system, and brainstem. This widespread brain involvement might explain why some headache sufferers concurrently experience a variety of symptoms, including fatigue, depression, muscle pain, and an abnormal sensitivity to light, sound, and smell.6,7

Although the exact mechanisms behind each of these symptoms have yet to be defined precisely, waves of neuronal depolarization—known as cortical spreading depression—are suspected to cause migraine aura.8-10 Cortical spreading depression activates the trigeminal pain pathway and leads to the release of pro-inflammatory markers such as calcitonin gene-related protein (CGRP).6 A better understanding of these complex signaling pathways has helped provide potential therapeutic targets for new migraine drugs.

Diagnosis: Close patient inquiry is most helpful

The International Headache Society (IHS) criteria for primary headache disorders serve as the basis for the diagnosis of migraine and its subtypes, which include migraine without aura and migraine with aura. Due to variability of presentation, migraine with aura is further subdivided into migraine with typical aura (with and without headache), migraine with brainstem aura, hemiplegic migraine, and retinal migraine.11

Continue to: How is migraine defined?

How is migraine defined? Simply, migraine is classically defined as a unilateral, pulsating headache of moderate to severe intensity lasting 4 to 72 hours, associated with photophobia and phonophobia or nausea and vomiting, or both.11 Often visual in nature, aura is a set of neurologic symptoms that lasts for minutes and precedes the onset of the headache. The visual aura is often described as a scintillating scotoma that begins near the point of visual fixation and then spreads left or right. Other aura symptoms include tingling or numbness (second most common), speech disturbance (aphasia), motor changes and, in rare cases, a combination of these in succession. By definition, all of these symptoms fully resolve between attacks.11

Validated valuable questionnaires. To help with accurate and timely diagnosis, researchers have developed and validated simplified questionnaires that can be completed independently by patients presenting to primary care (TABLE 112,13):

- ID Migraine is a set of 3 questions that scores positive when a patient endorses at least 2 of the 3 symptoms. 12

- MS-Q is similar to the ID Migraine but includes 5 items. A score of ≥4 is a positive screen. 13

The sensitivity and specificity of MS-Q (0.93 and 0.81, respectively) are slightly higher than those of ID Migraine (0.81 and 0.75).13

Remember POUND. This mnemonic device can also be used during history-taking to aid in diagnostic accuracy. Migraine is highly likely (92%) in patients who endorse 4 of the following 5 symptoms and unlikely (17%) in those who endorse ≤2 symptoms14: Pulsatile quality of headache 4 to 72 hOurs in duration, Unilateral location, Nausea or vomiting, and Disabling intensity.

Differential Dx. Although the differential diagnosis of headache is broad (TABLE 214,15), the history alone can often guide clinicians towards the correct assessment. After taking the initial history (headache onset, location, duration, and associated symptoms), focus your attention on assessing the risk of intracranial pathology. This is best accomplished by assessing specific details of the history (TABLE 314) and findings on physical examination15:

- blood pressure measurement (seated, legs uncrossed, feet flat on the floor; having rested for 5 minutes; arm well supported)

- cranial nerve exam

- extremity strength testing

- eye exam (vision, extra-ocular muscles, visual fields, pupillary reactivity, and funduscopic exam)

- gait (tandem walk)

- reflexes.

Continue to: Further testing needed?

Further testing needed? Neuroimaging should be considered only in patients with an abnormal neurologic exam, atypical headache features, or certain risk factors, such as an immune deficiency. There is no role for electroencephalography or other diagnostic testing in migraine.16

Take a multipronged approach to treatment

As with other complex, chronic conditions, the treatment of migraine should take a multifaceted approach, including management of acute symptoms as well as prevention of future headaches. In 2015, the American Headache Society published a systematic review that specified particular treatment goals for migraine sufferers. 17 These goals include:

- headache reduction

- headache relief

- decreased disability from headache

- elimination of nausea and vomiting

- elimination of photophobia and phonophobia.

Our review, which follows, of therapeutic options focuses on the management of migraine in adults. Approaches in special populations (older adults, pregnant women, and children) are discussed afterward.

Pharmacotherapy for acute migraine

Acute migraine should be treated with an abortive medication at the onset of headache. The immediate goal is to relieve pain within 2 hours and prevent its recurrence within the subsequent 48 hours (TABLE 412,18-20).

In the general population, mild, infrequent migraines can be managed with acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).21

Continue to: For moderate-to-severe migraine...

For moderate-to-severe migraine, triptans, which target serotonin receptors, are the drug of choice for most patients.21 Triptans are superior to placebo in achieving a pain-free state at 2 and 24 hours after administration; eletriptan has the most desirable outcome, with 68% of patients pain free at 2 hours and 54% pain free at 24 hours.22 Triptans are available as sublingual tablets and nasal sprays, as well as subcutaneous injections for patients with significant associated nausea and vomiting. Avoid prescribing triptans for patients with known vascular disease (eg, history of stroke, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, uncontrolled hypertension, or signs and symptoms of these conditions), as well as for patients with severe hepatic impairment.

Importantly, although triptans all have a similar mechanism of action, patients might respond differently to different drugs within the class. If a patient does not get adequate headache relief from an appropriate dosage of a given triptan during a particular migraine episode, a different triptan can be tried during the next migraine.22 Additionally, if a patient experiences an adverse effect from one triptan, this does not necessarily mean that a trial of another triptan at a later time is contraindicated.

For patients who have an incomplete response to migraine treatment or for those with frequent recurrence, the combination formulation of sumatriptan, 85 mg, and naproxen, 500 mg, showed the highest rate of resolution of headache within 2 hours compared with either drug alone.23 A similar result might be found by combining a triptan known to be effective for a patient and an NSAID other than naproxen. If migraine persists despite initial treatment of an attack, a different class of medication should be tried during the course of that attack to attain relief of symptoms of that migraine.21

When a patient is seen in an acute care setting (eg, emergency department, urgent care center) while suffering a migraine, additional treatment options are available. Intravenous (IV) anti-emetics are useful for relieving the pain of migraine and nausea, and can be used in combination with an IV NSAID (eg, ketorolac).21 The most effective anti-emetics are dopamine receptor type-2 blockers, including chlorpromazine, droperidol, metoclopramide, and prochlorperazine, which has the highest level of efficacy.24 Note that these medications do present the risk of a dystonic reaction; diphenhydramine is therefore often used in tandem to mitigate such a response.

Looking ahead. Although triptans are the current first-line therapy for acute migraine, their effectiveness is limited. Only 20% of patients report sustained relief of pain in the 2 to 24 hours after treatment, and the response can vary from episode to episode.25

Continue to: With better understading of the pathophysiology of migraine...

With better understanding of the pathophysiology of migraine, a host of novel anti-migraine drugs are on the horizon.

CGRP receptor antagonists. The neuropeptide CGRP, which mediates central and peripheral nervous system pain signaling, has been noted to be elevated during acute migraine attacks26; clinical trials are therefore underway to evaluate the safety and efficacy of CGRP receptor antagonists.18 These agents appear to be better tolerated than triptans, have fewer vascular and central nervous system adverse effects, and present less of a risk of medication overuse headache.18 Liver toxicity has been seen with some medications in this class and remains an important concern in their development.19

Phase 3 clinical trials for 1 drug in this class, ubrogepant, were completed in late 2017; full analysis of the data is not yet available. Primary outcomes being evaluated include relief of pain at 2 hours and relief from the most bothersome symptoms again at 2 hours.27

Selective serotonin-HT1f receptor agonists, such as lasmiditan, offer another potential approach. Although the exact mechanism of action of these agents is not entirely clear, clinical trials have supported their efficacy and safety.20 Importantly, ongoing trials are specifically targeting patients with known cardiovascular risk factors because they are most likely to benefit from the nonvasoconstrictive mechanism of action.28,29 Adverse effects reported primarily include dizziness, fatigue, and vertigo.

Strategies for managing recurrent episodic migraine

Because of the risk of medication overuse headache with acute treatment, daily preventive therapy for migraine is indicated for any patient with 30 :

- ≥6 headache days a month

- ≥4 headache days a month with some impairment

- ≥3 headache days a month with severe impairment.

Continue to: Treatment begins by having patients identify...

Treatment begins by having patients identify, and then avoid, migraine triggers (TABLE 5). This can be accomplished by having patients keep a headache diary, in which they can enter notations about personal and environmental situations that precede a headache.

For the individual patient, some triggers are modifiable; others are not. Helping a patient develop strategies for coping with triggers, rather than aiming for complete avoidance, might help her (him) manage those that are inescapable (eg stress, menstruation, etc).31 For many patients, however, this is not an adequate intervention and other approaches must be explored. When considering which therapy might be best for a given patient, evaluate her (his) comorbidities and assess that particular treatment for potential secondary benefits and the possibility of adverse effects. Pay attention to the choice of preventive therapy in women who are considering pregnancy because many available treatments are potentially teratogenic.

Oral medications. Oral agents from several classes of drugs can be used for migraine prophylaxis, including anti-epileptics,antidepressants, and antihypertensives (TABLE 620,29,30,32-41). Selected anti-epileptics (divalproex sodium, sodium valproate, topiramate) and beta-blockers (metoprolol, propranolol, and timolol) have the strongest evidence to support their use.32 Overall, regular use of prophylactic medications can reduce headache frequency by 50% for approximately 40% to 45% of patients who take them.29 However, adherence may be limited by adverse effects or perceived lack of efficacy, thus reducing their potential for benefit.42

OnabotulinumtoxinA. In patients with chronic migraine (≥15 headache days a month for at least 3 months) who have failed oral medications, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) recommends the use of onabotulinumtoxinA.30 The treatment regimen comprises 31 injections at various sites on the head, neck, and shoulders every 3 months.33

A 2010 large randomized controlled trial showed a decrease in the frequency of headache days for patients receiving onabotulinumtoxinA compared to placebo after a 24-week treatment period (7.8 fewer headache days a month, compared to 6.4 fewer in the placebo group).33 A recent systematic review also noted a reduction of 2 headache days a month compared with placebo; the authors cautioned, however, that data with which to evaluate onabotulinumtoxinA in comparison to other prophylactic agents are limited.43

Continue to: In both studies...

In both studies, the risk of adverse drug events due to onabotulinumtoxinA was high and led to a significant rate of discontinuation.33,43 Despite this, onabotulinumtoxinA remains the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved treatment for chronic migraine, making it reasonable to consider for appropriate patients.

Acupuncture. A 2016 Cochrane review found benefit for patients using acupuncture compared with sham acupuncture.34 When acupuncture was compared with prophylactic agents such as beta-blockers, calcium-channel blockers, and anti-epileptics, however, there was no significant difference between the procedure and pharmacotherapy. Patients willing and able to try acupuncture might see a reduction in the overall number of headaches. Acupuncture has few adverse effects; however, long-term data are lacking.34

Exercise is not supported by robust data for its role as a prophylactic treatment. It is generally considered safe in most populations, however, and can be pursued with little out-of-pocket cost.35

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). The AAN recommends CBT, relaxation therapy, and biofeedback therapy. Accessibility of these services remains limited for many patients, and cost can be prohibitive.16

Supplements used to help prevent migraine include the root of Petasites hybridus (butterbur), magnesium, vitamin B2 (riboflavin), Tanacetum parthenium (feverfew), and coenzyme Q10.16 Although the strength of evidence for these therapies is limited by small trials, their overall risk of adverse effects is low, and they might be easier for patients to obtain than acupuncture or CBT.

Continue to: Butterbur, in particular...

Butterbur, in particular, has been found to be beneficial for migraine prevention in 2 small placebo-controlled trials. In a randomized controlled study of 245 patients P hybridus, (specifically, the German formulation, Petadolex), 75 mg BID, reduced the frequency of migraine attack by 48% at 4 months, compared to placebo (number needed to treat, 5.3).44 No difference was found at lower dosages. The most common reported adverse effect was burping.

Regrettably, unpurified butterbur extract contains pyrrolizidine alkaloids, potentially hepatotoxic and carcinogenic compounds. Because of variations in purification in production facilities in the United States, butterbur supplements might not have all of these compounds removed—and so should be used with caution.41

Magnesium. Studies evaluating the use of magnesium have demonstrated varied results; differences in methods and dosing have limited broad application of findings. As with most supplements considered for prophylactic treatment, magnesium dosing is poorly understood, and bioavailability varies in its different forms. Oral supplementation can be given as magnesium dicitrate, 600 mg/d.45

Recently, products containing various combinations of feverfew, coenzyme Q10, riboflavin, magnesium, and other supplements have shown benefit in early clinical trials.36,37

Neural stimulation. Over the past few years, a variety of transcutaneous nerve stimulator devices have gained FDA approval for use in migraine prophylaxis. The long-term safety and efficacy of these devices is not yet well understood, but they appear to provide headache relief in the short term and decrease the frequency of headache.38 Use of the noninvasive stimulators is limited today by high cost and poor coverage by US health care insurers.

Continue to: Newly available medical therapy

Newly available medical therapy. The FDA recently approved erenumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody for prevention of migraine in adults. This is the first drug in the CGRP antagonist class to be approved for this indication. Trials of this once-monthly, self-injectable drug show promising results for patients whose migraines have been refractory to other therapies.

A recent large trial evaluated 955 adults with migraine, randomizing them to receive erenumab, 70 mg; erenumab, 140 mg; or placebo over 28 weeks.39 The groups receiving erenumab had a nearly 2-fold higher odds of having their migraine reduced by 50%, compared with placebo (number needed to treat with the 140-mg dose, 4.27). Similar numbers of participants from all groups discontinued the study.39 Phase 3 trials that are not yet formally published have produced similarly beneficial results.40,46 The FDA has listed injection site reaction and constipation as the most reported adverse effects.40

Three other anti-CGRP antibodies are likely to be approved in the near future: fremanezumab, galcanezumab, and eptinezumab.

The approach to migraine in special populations

Management of acute and chronic migraine in children, pregnant women, and older adults requires special attention: Treatment approaches are different than they are for adults 19 to 65 years of age.

Pediatric patients. Migraine is the most common acute and recurrent headache syndrome in children. Headaches differ from those of adult migraine as a result of variations in brain maturation, plasticity, and cognitive development.47 Migraine attacks are often of shorter duration in children, lasting 1 to 2 hours, but can still be preceded by visual aura.48 Just as with adults, imaging, electroencephalography, lumbar puncture, and routine labs should be considered only if a child has an abnormal neurological exam or other concerning features (TABLE 214,15).

Continue to: The general approach to migraine treatment...

The general approach to migraine treatment in the pediatric population includes education of the child and family about symptom management. Acetaminophen, NSAIDs, and triptans are approved for abortive therapy in children and should be used for acute headache relief in the same way that they are used in adults. Oral rizatriptan, the most well studied triptan in the pediatric population, is approved for use in children as young as 6 years49; the pediatric dosage is 5 mg/d for patients weighing 20 to 39 kg and 10 mg/d for patients weighing more than 40 kg (same as the adult dosage).

Oral almotriptan and zolmitriptan are also approved for use in children 12 to 17 years of age. Usual dosages are: almotriptan, 12.5 mg at onset, can repeat in 2 hours as needed (maximum dosage, 25 mg/d); and zolmitriptan, 2.5 mg at onset, can repeat in 2 hours as needed (maximum dosage, 10 mg/d).50

For children who are unable to swallow pills or who are vomiting, a non-oral route of administration is preferable. Rizatriptan is available as an orally disintegrating tablet. Zolmitriptan is available in a nasal spray at a dose of 5 mg for children 12 years and older. Sumatriptan is not approved for use in patients younger than 18 years; however, recent studies have shown that it might have good efficacy and tolerability.50

Daily prophylactic treatment for recurrent migraine in the pediatric population is an evolving subject; published guidelines do not exist. It is reasonable to consider treatment using the same guidelines as those in place for adults.51 Topiramate, 1 to 2 mg/kg/d, is the only therapy approved by the FDA for episodic migraine preventive therapy in adolescents.50

Notably, a nonpharmacotherapeutic approach may be more effective for pediatric prevention. In 2017, a large double-blind, placebo-controlled trial investigated the use of amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo for the treatment of recurrent migraine in children 8 to 17 years of age. An interim analysis of the 328 children enrolled found no significant differences in reduction of headache frequency with treatment compared with placebo over a 24-week period; the trial was stopped early due to futility.52

Continue to: The study did show...

The study did show, however, that reducing migraine triggers provided a high level of benefit to study participants. Stress is one of the most common migraine triggers in children; lack of sleep, exposure to a warm climate, and exposure to video games are also notable triggers.53 CBT may augment the efficacy of standard migraine medications in the pediatric population and may help prevent recurrence of episodes.54

Pregnancy. The treatment of migraine is different in pregnant women than it is in nonpregnant adults because of a concern over adverse effects on fetal development. For acute headache treatment, first-line therapies include trigger avoidance and acetaminophen, 1000 mg (maximum dosage, 4000 mg/d).55 If this is ineffective, a 10-mg dose of metoclopramide, as often as every 6 hours (not an FDA-approved indication), can be considered. During the second trimester, NSAIDs can be considered second-line therapy.

Triptans—specifically, sumatriptan and rizatriptan—can also be considered if first-line therapies fail.56 Triptan-exposed pregnant women with migraine have a rate of congenital malformations, spontaneous abortions, and prematurity that is similar to what is seen in pregnant women with migraine who have not been exposed to triptans. However, when triptan-exposed women are compared with healthy, non-migraine-suffering women, the rate of spontaneous abortion appears to be increased in the triptan-exposed population.57

Ergotamine is contraindicated during pregnancy because of its potential to induce uterine contractions and vasospasm, which can be detrimental to the fetus.56Nonpharmacotherapeutic interventions such as heat, ice, massage, rest, and avoidance of triggers are as successful in the pregnant population as in the nonpregnant population. For migraine prevention, coenzyme Q10, vitamins B2 and B6 (pyridoxine), and oral magnesium can be considered. Feverfew and butterbur should be avoided because of concerns about fetal malformation and preterm labor.58

Older adults. Choosing appropriate migraine therapy for older adults requires special consideration because of changes in drug metabolism and risks associated with drug adverse effects. Additionally, few studies of migraine drugs have included large populations of adults older than 65 years; medications should therefore be prescribed cautiously in this population, with particular attention to drug–drug interactions.

Continue to: Just as for younger adults...

Just as for younger adults, mild symptoms can be managed effectively with acetaminophen. NSAIDs may be used as well, but carry increased risks of gastric bleeding and elevation in blood pressure.59 The use of triptans is acceptable for the appropriate patient, but should be avoided in patients with known vascular disease.60 Antiemetics present an increased risk of extrapyramidal adverse effects in the elderly and should be used with caution at the lowest effective dosage.59 Novel mechanisms of action make some of the newer agents potentially safer for use in older adults when treating acute migraine.

For migraine prevention in older adults, particular attention should be paid to reducing triggers and minimizing polypharmacy.

More and more, successful treatment is within reach

With many clinical trials evaluating novel drugs underway, and additional studies contributing to our understanding of nonpharmacotherapeutic approaches to migraine treatment, improved headache control may become increasingly common over the next few years.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kathryn McGrath, MD, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Thomas Jefferson University, 1015 Walnut St, Philadelphia PA 19107; Kathryn.mcgrath@jefferson.edu.

Migraine is a highly disabling primary headache disorder that affects more than 44 million Americans annually.1 The disorder causes pain, photophobia, phonophobia, and nausea that can last for hours, even days. Migraine headaches are 2 times more common in women than in men; although migraine is most common in people 30 to 39 years of age, all ages are affected.2,3 Frequency of migraine headache is variable; chronic migraineurs experience more than 15 headache days a month.

Recent estimates indicate that the cost of acute and chronic migraine headaches reaches approximately $78 million a year in the United States. 4 This high burden of disease has made effective migraine treatment options absolutely essential. Recent advances in our understanding of migraine pathophysiology have led to new therapeutic targets; there are now many novel treatment approaches on the horizon.

In this article, we review the diagnosis and management of migraine in detail. Our emphasis is on evidence-based approaches to acute and prophylactic treatment, including tried-and-true options and newly emerging therapies.

Neuronal dysfunction and a genetic predisposition

Although migraine was once thought to be caused by abnormalities of vasodilation, current research suggests that the disorder has its origins in primary neuronal dysfunction. There appears to be a genetic predisposition toward widespread neuronal hyperexcitability in migraineurs.5 In addition, hypothalamic neurons are thought to initiate migraine by responding to changes in brain homeostasis. Increased parasympathetic tone might activate meningeal pain receptors or lower the threshold for transmitting pain signals from the thalamus to the cortex.6

Prodromal symptoms and aura appear to originate from multiple areas across the brain, including the hypothalamus, cortex, limbic system, and brainstem. This widespread brain involvement might explain why some headache sufferers concurrently experience a variety of symptoms, including fatigue, depression, muscle pain, and an abnormal sensitivity to light, sound, and smell.6,7

Although the exact mechanisms behind each of these symptoms have yet to be defined precisely, waves of neuronal depolarization—known as cortical spreading depression—are suspected to cause migraine aura.8-10 Cortical spreading depression activates the trigeminal pain pathway and leads to the release of pro-inflammatory markers such as calcitonin gene-related protein (CGRP).6 A better understanding of these complex signaling pathways has helped provide potential therapeutic targets for new migraine drugs.

Diagnosis: Close patient inquiry is most helpful

The International Headache Society (IHS) criteria for primary headache disorders serve as the basis for the diagnosis of migraine and its subtypes, which include migraine without aura and migraine with aura. Due to variability of presentation, migraine with aura is further subdivided into migraine with typical aura (with and without headache), migraine with brainstem aura, hemiplegic migraine, and retinal migraine.11

Continue to: How is migraine defined?

How is migraine defined? Simply, migraine is classically defined as a unilateral, pulsating headache of moderate to severe intensity lasting 4 to 72 hours, associated with photophobia and phonophobia or nausea and vomiting, or both.11 Often visual in nature, aura is a set of neurologic symptoms that lasts for minutes and precedes the onset of the headache. The visual aura is often described as a scintillating scotoma that begins near the point of visual fixation and then spreads left or right. Other aura symptoms include tingling or numbness (second most common), speech disturbance (aphasia), motor changes and, in rare cases, a combination of these in succession. By definition, all of these symptoms fully resolve between attacks.11

Validated valuable questionnaires. To help with accurate and timely diagnosis, researchers have developed and validated simplified questionnaires that can be completed independently by patients presenting to primary care (TABLE 112,13):

- ID Migraine is a set of 3 questions that scores positive when a patient endorses at least 2 of the 3 symptoms. 12

- MS-Q is similar to the ID Migraine but includes 5 items. A score of ≥4 is a positive screen. 13

The sensitivity and specificity of MS-Q (0.93 and 0.81, respectively) are slightly higher than those of ID Migraine (0.81 and 0.75).13

Remember POUND. This mnemonic device can also be used during history-taking to aid in diagnostic accuracy. Migraine is highly likely (92%) in patients who endorse 4 of the following 5 symptoms and unlikely (17%) in those who endorse ≤2 symptoms14: Pulsatile quality of headache 4 to 72 hOurs in duration, Unilateral location, Nausea or vomiting, and Disabling intensity.

Differential Dx. Although the differential diagnosis of headache is broad (TABLE 214,15), the history alone can often guide clinicians towards the correct assessment. After taking the initial history (headache onset, location, duration, and associated symptoms), focus your attention on assessing the risk of intracranial pathology. This is best accomplished by assessing specific details of the history (TABLE 314) and findings on physical examination15:

- blood pressure measurement (seated, legs uncrossed, feet flat on the floor; having rested for 5 minutes; arm well supported)

- cranial nerve exam

- extremity strength testing

- eye exam (vision, extra-ocular muscles, visual fields, pupillary reactivity, and funduscopic exam)

- gait (tandem walk)

- reflexes.

Continue to: Further testing needed?

Further testing needed? Neuroimaging should be considered only in patients with an abnormal neurologic exam, atypical headache features, or certain risk factors, such as an immune deficiency. There is no role for electroencephalography or other diagnostic testing in migraine.16

Take a multipronged approach to treatment

As with other complex, chronic conditions, the treatment of migraine should take a multifaceted approach, including management of acute symptoms as well as prevention of future headaches. In 2015, the American Headache Society published a systematic review that specified particular treatment goals for migraine sufferers. 17 These goals include:

- headache reduction

- headache relief

- decreased disability from headache

- elimination of nausea and vomiting

- elimination of photophobia and phonophobia.

Our review, which follows, of therapeutic options focuses on the management of migraine in adults. Approaches in special populations (older adults, pregnant women, and children) are discussed afterward.

Pharmacotherapy for acute migraine

Acute migraine should be treated with an abortive medication at the onset of headache. The immediate goal is to relieve pain within 2 hours and prevent its recurrence within the subsequent 48 hours (TABLE 412,18-20).

In the general population, mild, infrequent migraines can be managed with acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).21

Continue to: For moderate-to-severe migraine...

For moderate-to-severe migraine, triptans, which target serotonin receptors, are the drug of choice for most patients.21 Triptans are superior to placebo in achieving a pain-free state at 2 and 24 hours after administration; eletriptan has the most desirable outcome, with 68% of patients pain free at 2 hours and 54% pain free at 24 hours.22 Triptans are available as sublingual tablets and nasal sprays, as well as subcutaneous injections for patients with significant associated nausea and vomiting. Avoid prescribing triptans for patients with known vascular disease (eg, history of stroke, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, uncontrolled hypertension, or signs and symptoms of these conditions), as well as for patients with severe hepatic impairment.

Importantly, although triptans all have a similar mechanism of action, patients might respond differently to different drugs within the class. If a patient does not get adequate headache relief from an appropriate dosage of a given triptan during a particular migraine episode, a different triptan can be tried during the next migraine.22 Additionally, if a patient experiences an adverse effect from one triptan, this does not necessarily mean that a trial of another triptan at a later time is contraindicated.

For patients who have an incomplete response to migraine treatment or for those with frequent recurrence, the combination formulation of sumatriptan, 85 mg, and naproxen, 500 mg, showed the highest rate of resolution of headache within 2 hours compared with either drug alone.23 A similar result might be found by combining a triptan known to be effective for a patient and an NSAID other than naproxen. If migraine persists despite initial treatment of an attack, a different class of medication should be tried during the course of that attack to attain relief of symptoms of that migraine.21

When a patient is seen in an acute care setting (eg, emergency department, urgent care center) while suffering a migraine, additional treatment options are available. Intravenous (IV) anti-emetics are useful for relieving the pain of migraine and nausea, and can be used in combination with an IV NSAID (eg, ketorolac).21 The most effective anti-emetics are dopamine receptor type-2 blockers, including chlorpromazine, droperidol, metoclopramide, and prochlorperazine, which has the highest level of efficacy.24 Note that these medications do present the risk of a dystonic reaction; diphenhydramine is therefore often used in tandem to mitigate such a response.

Looking ahead. Although triptans are the current first-line therapy for acute migraine, their effectiveness is limited. Only 20% of patients report sustained relief of pain in the 2 to 24 hours after treatment, and the response can vary from episode to episode.25

Continue to: With better understading of the pathophysiology of migraine...

With better understanding of the pathophysiology of migraine, a host of novel anti-migraine drugs are on the horizon.

CGRP receptor antagonists. The neuropeptide CGRP, which mediates central and peripheral nervous system pain signaling, has been noted to be elevated during acute migraine attacks26; clinical trials are therefore underway to evaluate the safety and efficacy of CGRP receptor antagonists.18 These agents appear to be better tolerated than triptans, have fewer vascular and central nervous system adverse effects, and present less of a risk of medication overuse headache.18 Liver toxicity has been seen with some medications in this class and remains an important concern in their development.19

Phase 3 clinical trials for 1 drug in this class, ubrogepant, were completed in late 2017; full analysis of the data is not yet available. Primary outcomes being evaluated include relief of pain at 2 hours and relief from the most bothersome symptoms again at 2 hours.27

Selective serotonin-HT1f receptor agonists, such as lasmiditan, offer another potential approach. Although the exact mechanism of action of these agents is not entirely clear, clinical trials have supported their efficacy and safety.20 Importantly, ongoing trials are specifically targeting patients with known cardiovascular risk factors because they are most likely to benefit from the nonvasoconstrictive mechanism of action.28,29 Adverse effects reported primarily include dizziness, fatigue, and vertigo.

Strategies for managing recurrent episodic migraine

Because of the risk of medication overuse headache with acute treatment, daily preventive therapy for migraine is indicated for any patient with 30 :

- ≥6 headache days a month

- ≥4 headache days a month with some impairment

- ≥3 headache days a month with severe impairment.

Continue to: Treatment begins by having patients identify...

Treatment begins by having patients identify, and then avoid, migraine triggers (TABLE 5). This can be accomplished by having patients keep a headache diary, in which they can enter notations about personal and environmental situations that precede a headache.

For the individual patient, some triggers are modifiable; others are not. Helping a patient develop strategies for coping with triggers, rather than aiming for complete avoidance, might help her (him) manage those that are inescapable (eg stress, menstruation, etc).31 For many patients, however, this is not an adequate intervention and other approaches must be explored. When considering which therapy might be best for a given patient, evaluate her (his) comorbidities and assess that particular treatment for potential secondary benefits and the possibility of adverse effects. Pay attention to the choice of preventive therapy in women who are considering pregnancy because many available treatments are potentially teratogenic.

Oral medications. Oral agents from several classes of drugs can be used for migraine prophylaxis, including anti-epileptics,antidepressants, and antihypertensives (TABLE 620,29,30,32-41). Selected anti-epileptics (divalproex sodium, sodium valproate, topiramate) and beta-blockers (metoprolol, propranolol, and timolol) have the strongest evidence to support their use.32 Overall, regular use of prophylactic medications can reduce headache frequency by 50% for approximately 40% to 45% of patients who take them.29 However, adherence may be limited by adverse effects or perceived lack of efficacy, thus reducing their potential for benefit.42

OnabotulinumtoxinA. In patients with chronic migraine (≥15 headache days a month for at least 3 months) who have failed oral medications, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) recommends the use of onabotulinumtoxinA.30 The treatment regimen comprises 31 injections at various sites on the head, neck, and shoulders every 3 months.33

A 2010 large randomized controlled trial showed a decrease in the frequency of headache days for patients receiving onabotulinumtoxinA compared to placebo after a 24-week treatment period (7.8 fewer headache days a month, compared to 6.4 fewer in the placebo group).33 A recent systematic review also noted a reduction of 2 headache days a month compared with placebo; the authors cautioned, however, that data with which to evaluate onabotulinumtoxinA in comparison to other prophylactic agents are limited.43

Continue to: In both studies...

In both studies, the risk of adverse drug events due to onabotulinumtoxinA was high and led to a significant rate of discontinuation.33,43 Despite this, onabotulinumtoxinA remains the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved treatment for chronic migraine, making it reasonable to consider for appropriate patients.

Acupuncture. A 2016 Cochrane review found benefit for patients using acupuncture compared with sham acupuncture.34 When acupuncture was compared with prophylactic agents such as beta-blockers, calcium-channel blockers, and anti-epileptics, however, there was no significant difference between the procedure and pharmacotherapy. Patients willing and able to try acupuncture might see a reduction in the overall number of headaches. Acupuncture has few adverse effects; however, long-term data are lacking.34

Exercise is not supported by robust data for its role as a prophylactic treatment. It is generally considered safe in most populations, however, and can be pursued with little out-of-pocket cost.35

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). The AAN recommends CBT, relaxation therapy, and biofeedback therapy. Accessibility of these services remains limited for many patients, and cost can be prohibitive.16

Supplements used to help prevent migraine include the root of Petasites hybridus (butterbur), magnesium, vitamin B2 (riboflavin), Tanacetum parthenium (feverfew), and coenzyme Q10.16 Although the strength of evidence for these therapies is limited by small trials, their overall risk of adverse effects is low, and they might be easier for patients to obtain than acupuncture or CBT.