User login

CE/CME No: CR-1403

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Explain the pathophysiology and etiology of allergic rhinitis (AR).

• Describe the prevalence and types of AR.

• List the differential diagnoses for AR.

• Describe the historical and physical examination findings that are typical

of AR.

• Explain the indications for and types of allergy testing.

• Discuss the types of allergy desensitization therapies/immunotherapies.

FACULTY

Randy D. Danielsen is a Professor and Dean of the Arizona School of Health Sciences, A.T. Still University in Mesa, Arizona, and a long-time PA with the Arizona Asthma & Allergy Institute. Linda S. MacConnell is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Physician Assistant Studies at the Arizona School of Health Sciences, A.T. Still University, and a formally trained otolaryngology PA.

The authors have no financial disclosures to report.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Article begins on next page >>

Allergic rhinitis (AR), one of the most familiar complaints seen in primary care, is a common immunologic condition that occurs in genetically predisposed patients. AR is routinely treated through allergen avoidance and pharmacologic therapy. When these measures fail, however, immunologic treatment may be indicated. This review of AR and its treatment focuses on injection and oral immunotherapy.

Congestion; sneezing (particularly paroxysms); itchy nose, palate, and eyes; and runny nose are symptoms characteristic of allergic rhinitis (AR) seen every day in virtually all primary care offices. Patients are plagued not only by their symptoms, but also by AR-related sleep disturbances, resulting in fatigue and daytime sleepiness, irritability, and memory deficits. In children, these sleep disruptions may even cause behavioral disturbances. Depending on the cause, some patients may experience allergic symptoms only with outdoor environmental exposure and subsequent immunoglobulin E (IgE)–mediated responses to otherwise innocuous allergens, while others find that their symptoms are constant, occurring both indoors and out.

Although the prevalence of AR is increasing,1 allergies are certainly nothing new to humankind. In fact, hieroglyphics and Egyptian wall paintings have been discovered depicting a pharaoh dying from anaphylactic shock after receiving a wasp sting.2 In 1565, Leonardo Botallo described AR, calling it “rose catarrh” (mucous or phlegm) or “rose fever,” based on the mistaken idea that the symptoms were caused by rose pollen.2 John Babcock, an English physician, first diagnosed an upper respiratory disease that he called “hay fever” in 1819.

Seventy years later, Charles Blackley identified pollen as a cause of hay fever, documenting his findings in his 1873 book Experimental Researches on the Causes and Nature of Catarrhus Aestivus.2 Dr. Blackley performed the initial documented attempts at allergy desensitization treatments on himself—a willing patient, as he suffered from AR. He placed rye grass pollen onto his nasal mucosa, finding that after 30 minutes the nostril was completely occluded. He continued his experimentation by repeatedly exposing himself to pollen grains via abraded skin. Alas, he never noted any decrease in his symptoms.3

Presently, AR affects more than 55 million people in the United States4—approximately 10% to 30% of the adult population5 and more than 40% of children.6 The rising prevalence of AR is of concern in older adults, who tend to have related comorbidities (eg, chronic sinusitis, asthma, and otitis media). In fact, AR is the fifth most common chronic disease in the US.7

AR and its treatment impose a great economic burden on the health care system, critical in these days of affordable health care. In fact, in 2005 in the US, the overall (direct medical and indirect) cost of AR was $11.2 billion.8 Direct costs derive from office visits, diagnostic testing, and therapeutics. Costs are considerably higher when indirect expenses, including decreased productivity, missed school and missed workdays to care for children, and costs of travel to medical appointments, are included. In the US, approximately 3.5 million workdays and 2 million school days are lost each year due to AR.9 Decreases in productivity cost an estimated $600 per affected employee per year, all of which results in AR being the fifth costliest chronic disease.10,11

On the next page: Pathophysiology and examination >>

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

AR is an immunologic disorder that occurs in genetically susceptible individuals who produce allergen-specific IgE antibody responses after environmental exposures. The IgE-mediated response causes inflammation of the nasal mucosa. Compared to controls, individuals with AR demonstrate increased amounts of IgE antibodies in the nasal mucosa.11 IgE binds to basophils in the bloodstream and mast cells in tissue. Allergens then attach to IgE on basophils and mast cells, which release histamines, prostaglandins, cytokines, and leukotrienes, with histamine being the most significant mediator in the inflammatory response.

In response to allergy-provoking substances, patients experience immediate- and late-phase symptoms. Symptoms of each stage are similar, but congestion is the hallmark of the late phase. While both phases are clinically important because of their contribution to the patient’s symptoms, most patients experience continued exposure to allergens, resulting in constant, overlapping symptoms.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Patients with AR relate a history of congestion, excessive mucous production, itchy, watery eyes, bouts of sneezing, and more systemic symptoms, such as headache, malaise, and excessive fatigue. It is important to evaluate the degree and duration of the symptoms, noting patterns and triggers, in an effort to confirm the diagnosis and to help the patient evaluate treatment options.

When taking the patient history, always review the family history, which is often notable for allergies and other atopic diseases. Be sure to ask about medications and recreational drug use; a number of substances have been implicated in the development of rhinitis, including anticholinergic medications, oxymetazoline (when overused), and cocaine. Also, question the patient about self-medication and treatment to determine what may or may not have provided relief. Further questioning may also reveal a history of comorbidities, including contact dermatitis, asthma, eczema, and chronic sinusitis.

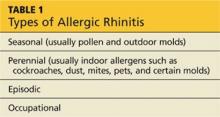

The physical examination of the patient with rhinitis begins with observation of the patient’s outward appearance, which may reveal allergic shiners (dark to purplish areas under the eyes), conjunctivitis, an allergic salute (a transverse crease of the nose caused by upward rubbing of an itchy nose), mouth breathing, and a generally tired appearance. The nasal turbinates are swollen and often pale. Mucous secretions are usually thin and clear. Enlarged tonsils and posterior nasal drainage may be visualized. The types of AR are listed in Table 1.

On the next page: Diagnosis and treatment >>

DIAGNOSIS

Most of the clues needed to arrive at a diagnosis are discovered by taking a careful history and completing a physical examination. AR frequently underlies and/or coexists with acute upper respiratory infection (URI) and acute and chronic sinusitis. Differentiating acute URI and acute sinusitis from AR is usually relatively straightforward, based on the symptoms of the illness. The diagnosis of chronic sinusitis is made by radiologic imaging with CT scan.

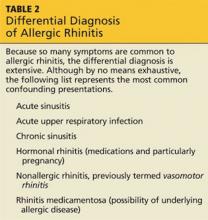

Distinguishing nonallergic rhinitis (NAR) from AR can be far more difficult, because the symptoms of these conditions are similar and chronic in nature (see Table 2). Empiric treatment for AR may be attempted; however, further testing is often needed to differentiate the two. At this point, clinicians may choose to proceed with specific IgE blood tests. Alternatively, many medical practices are prepared to perform or refer for allergy skin testing.

TREATMENT

Avoidance of known triggers is the cornerstone of allergy treatment. Currently, the most effective pharmaceutical treatment for the majority of AR symptoms is inhaled nasal corticosteroids. Although less effective than corticosteroids, antihistamines—both nasal and oral—are a recommended addition to the regimen if the adverse effects and costs to the patient are tolerable. Other treatments include the leukotriene receptor antagonists, intranasal formulations of cromolyn, and the anticholinergic ipratropium bromide nasal spray, which is effective primarily on watery rhinorrhea. If symptoms are not controlled with medication, allergy immunotherapy (AI), the only known disease-modifying therapy for AR, may be indicated.

On the next page: Allergy testing >>

ALLERGY TESTING

In order to distinguish between AR and NAR and to direct treatment toward specific allergen avoidance and immunotherapy, providers have the choice of ordering in vitro blood IgE testing (to measure the antibodies that mediate an allergic response) or in vivo allergy skin testing (to measure the immune response to allergens that induces an allergic atopic reaction). Allergy testing is not a contemporary concept; the first allergy testing was documented in 1656 when Pierre Borel applied egg to a patient’s skin, which exhibited an allergic reaction.2

Allergy skin testing consists of applying multiple allergens to the skin of the patient’s forearms via tiny pinpricks while watching for immediate hypersensitivity reactions. The test begins with the placement of a drop of histamine to serve as a control. If after 10 minutes of watchful waiting the patient develops a reaction to the histamine (a positive test result), it is appropriate to test for antigens by placing drops of suspected allergen extracts on the skin.

After a period of time (usually 20 to 30 minutes), the area is inspected for allergic reaction. An immediate (early phase) wheal and flare (surrounding erythema) reaction may develop. This positive reaction indicates the presence of a mast cell–bound IgE antibody specific to the tested allergen. The size of the reactions is measured in millimeters, allowing for comparison to the histamine control.

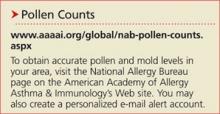

A list of the commonly tested antigens in Arizona, as an example, is shown in Table 3. Antigens vary geographically and even from practice to practice. For up-to-date information on pollen counts by region, visit the American Academy of Allergy Asthma & Immunology Web site (see “Pollen Counts”).

On the next page: Patient selection and allergy immunotherapy >>

Patient Selection

After the clinician has determined that there is a high likelihood that the diagnosis is AR, allergy testing, needed to guide AI, is appropriate. Although not true of specific IgE testing, the accuracy of allergy skin testing results can be adversely affected by several medications. For example, some practitioners may choose to stop first-generation antihistamines two to three days before testing. It is generally accepted that the newer, second-generation antihistamines, which can affect skin-testing results longer, be stopped a week prior to testing.

Patients should be reminded that OTC sleep aids frequently contain antihistamines (particularly diphenhydramine) and that they must be discontinued prior to testing as well. Histamine H2-receptor antagonists such as cimetidine and ranitidine may be stopped a day or two before testing. Although β-blockers are only relatively contraindicated in both allergy testing and AI, many health care providers avoid testing and AI in patients taking oral and/or topical (eye drops) β-blocker therapy. Ultimately, the decision is made by individual health care practices.

In vivo allergy skin testing should not be performed on patients taking tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Patients with significant cardiovascular disease should not undergo testing or treatment. Pregnancy is a relative contraindication, and allergy skin testing and AI are done only with obstetrician approval. Most allergists avoid allergy skin testing in pregnant women, however, because use of epinephrine, if required, introduces the risk for preterm labor.12,13 Special consideration should also be given to patients with immune deficiencies.

Setting for Allergy Evaluation and Treatment

Recently, many primary care practices have added allergy evaluation and management to the procedures and treatments they offer; however, evaluations and testing traditionally have been performed by allergy and immunology specialists, many of whom include PAs and NPs on their staff. PAs and NPs frequently manage the practices’ allergy programs. Allergists who are listed as American Board of Allergy and Immunology (ABAI)–certified have successfully passed the ABAI’s certifying examination. Other medical specialists, including otolaryngologists and the primary care specialties, are also well placed to evaluate patients with common allergy symptoms and provide appropriate treatment.

Allergy Immunotherapy

AI has now become more efficacious, safer, and more tolerable for the patient than when it was first introduced in 1911. At that time, Leonard Noon authored a brief article claiming that allergen-specific injections could modify AR. Unfortunately, Noon died at age 36 from tuberculosis, but his work was carried on by his associate, John Freeman. Together, they established the guidelines upon which contemporary AI is based, including the protocol to gradually increase the dose of allergen serum, starting with initial weekly to biweekly injections. They also voiced warnings about the potential for anaphylaxis.14 To this day, immunotherapy is still accomplished by the gradual administration of increasing amounts of the allergen to which the patient is sensitive. This tempers the abnormal immune response to that allergen, easing allergic symptoms.

In patients with IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions, confirmed by history, physical examination, and allergy skin testing, immunotherapy can be very effective. The results of immunotherapy may last for years and may even prevent the allergic march, the progression of allergic disease experienced by many patients that frequently begins early in life.15 This includes other allergy-related conditions, such as asthma and eczema (atopic dermatitis), and the acquisition of additional new allergies, including those to foods. AI also has been shown to decrease the frequency of comorbidities such as asthma.5 In addition, AI is used in carefully screened patients who desire to reduce the dosages of medication required to control their symptoms.

In a study published in 1999, Durham and colleagues clarified the questions surrounding the amount of time required for ongoing immunotherapy. They found that the desensitization and tolerance to allergens achieved by AI can last up to three years after a three- to four-year course of therapy. They also found that treatment should not start until an allergic component is identified by allergy skin testing or serum tests for allergen-specific IgE.16

As effective as immunotherapy has been documented to be, it is underused as a therapeutic modality. There are only 2 to 3 million patients receiving subcutaneous immunotherapy out of more than 55 million patients with AR.17

On the next page: Types of allergy immunotherapy >>

Types of AI

There are two categories of allergen desensitization therapy. The most common method is subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT), the so-called allergy shots. Less common and still somewhat controversial is sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT). Immunotherapy should be considered for patients who have secondary complications (eg, sinusitis, otitis) or asthma with allergies, or those in whom avoidance measures and medications fail. SCIT or SLIT may be desirable for patients with AR who have difficulty taking regular medications.

Subcutaneous immunotherapy. Currently, SCIT is the most recognized immunotherapy and the only one currently reimbursed by insurance. The procedure involves the subcutaneous injection of increasing doses of therapeutic solutions to which a patient has demonstrated sensitivity. The indications for this treatment are usually inhaled allergens, such as pollens and animal dander. SCIT may also be valuable in patients with asthma and atopic dermatitis.

The most common adverse reaction to allergy injections is a large localized reaction—primarily erythema, pruritus, discomfort, and possibly edema. Severe systemic reactions are extremely rare, with near-fatal to fatal reactions occurring at the rate of only 5.4 per million injections.11 The majority of these rare, albeit serious, complications are caused by higher-than-normal levels of pollen in the environment and dosing errors.11 Because of the uncommon but significant complications, patients undergoing immunotherapy should always receive injections in a medical office equipped with appropriate equipment and staff trained in handling anaphylaxis. It is standard protocol for patients to remain in the office for 30 minutes after administration for observation. Some clinicians prescribe epinephrine injectors (Epi-Pens) for patients to bring to every appointment as a condition for receiving their shot. Because of continuing controversy on this point, others only employ this requirement if the patient has a history of an adverse reaction.

Various protocols exist for the up-dosing of immunotherapy, most of which recommend weekly to twice-weekly injections prior to initiating maintenance therapy. Costs, risks, and benefits must be carefully considered and discussed with the patient prior to initiating immunotherapy.

Many insurance companies reimburse for immunotherapy, with varying copayments. Additionally, the time commitment may be taxing on the patient’s busy schedule. Weekly or biweekly appointments are required initially, and the patient must remain on site for half an hour. Although direct costs of SCIT are relatively easily measured and perhaps compensated, the indirect costs of time spent commuting and at the clinic are less tangible.

Success rates with SCIT may be more than 70% for certain allergens,18 but it is a long-term process with initial improvement often not seen until after six to 12 months of therapy. The benefits of therapy lead not only to reduction and suppression in symptoms (and medication), but also to reduction in comorbidity and lost school or workdays and improvement in quality of life.

Sublingual immunotherapy. Because of the possible safety concerns surrounding SCIT, along with problems relating to patient adherence to weekly office visits, alternative means of achieving allergen desensitization have been implemented. One of these methods, SLIT, has been increasingly supported by clinical evidence, especially in Europe. This therapy consists of applying aqueous allergen extract to the sublingual or oral mucosa, allowing it to be absorbed into the body. Subsequent swallowing of the extract allows the gut to respond with an increase in tolerance. The changes that result from this type of administration appear to be similar to those observed with SCIT.

SLIT has been in use for almost 30 years; the first published controlled study of this therapy was done in 1986 by Scadding and Brostoff.19 The World Allergy Organization recognized the safety and clinical efficacy of SLIT in 2009 after reviewing more than 60 controlled studies.20

A 2010 meta-analysis, reviewing documents from the prior 20 years of research, showed that SLIT decreased medication use and improved symptoms.21 Generally, SLIT was found to be more effective in adults than children. It was not as effective in patients with asthma as in those who were asthma-free. The timing of initiation of SLIT was also an important finding; when SLIT is used for grass pollen allergy, it should be started at least three months before the beginning of grass season.21 For other allergens, SLIT can be started at any time.

Because it is a home-based treatment, SLIT is far more convenient for the patient and therefore has become more popular in the US in the past decade. Its increased safety also contributes to its popularity. Although SLIT is commonly used in many parts of the world, at this writing, medications used in SLIT have not yet been approved by the US FDA. The FDA is currently reviewing two oral tablets for SLIT, and it is expected that its use in the US will increase once an approved product becomes available.22

It should be noted that no studies have directly compared SCIT and SLIT. Careful consultation between clinician and patient can help the patient arrive at the most appropriate modality for his or her condition based on symptomatology and lifestyle needs.

On the next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

For most patients, AR has little morbidity; however, for some whose rhinitis is moderate to severe, the complications can be a concern. If symptoms are not controlled with avoidance and/or medication, AI may be indicated. It comprises the building up of tolerance to the specific allergens as identified by allergy skin testing or in vitro specific IgE testing. AI, whether SCIT or SLIT, is the only means of altering the abnormal immune system response that underlies AR. Treatment may last as long as three to four years, which provides long-term efficacy of at least three years after cessation of therapy. The long-term prognosis for AR is excellent.

Appreciation is extended to Roxy Irestone, RN, Arizona Asthma & Allergy Institute, for her assistance is gathering factual information for this article.

1. Sibbald B, Rink E, D’Souza M. Is the prevalence of atopy increasing? Br J Gen Pract. 1990;40(337):338-340.

2. History of allergy. Allergy and Asthma Specialists Web site. www.allergyasthmaspecialist.com/allergy-and-asthma-clinic-of-kenosha-sc-education.htm. Accessed February 14, 2014.

3. Blackley CH. Hay Fever: Its Causes, Treatment, and Effective Prevention. London, England: Balliere, Tindall, & Cox; 1880.

4. Settipane RA. Rhinitis: a dose of epidemiological reality. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2003;24(3):147-154.

5. Wallace DV, Dykewicz MS, Bernstein DI, et al. The diagnosis and management of rhinitis: an updated practice parameter. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122(2 suppl):S1-S84.

6. Wright AL, Holberg CJ, Halonen M, et al. Epidemiology of physician-diagnosed allergic rhinitis in childhood. Pediatrics. 1994;94(6):895 -901.

7. Bernstein JA. Allergic and mixed rhinitis: epidemiology and natural history. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010;31:365-369.

8. Meltzer EO, Bukstein DA. The economic impact of allergic rhinitis and current guidelines for treatment. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011; 106(suppl 2):S12-S16.

9. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. Task force on allergic disorders: promoting best practice: raising the standard of care for patients with allergic disorders. Executive summary report. 1998.

10. Nathan RA. The burden of allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2007; 28:3-9.

11. Tran NP, Vickery J, Blaiss MS. Management of rhinitis: allergic and non-allergic. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3:148-156.

12. Disease Summaries: Allergic Diseases and Asthma in Pregnancy. World Allergy Organization. www.worldallergy.org/professional/allergic_

diseases_center/allergy_in_pregnancy/. Accessed February 14, 2014.

13. Simons FE, Ardusso LR, Dimov V, et al. World Allergy Organization Anaphylaxis Guidelines: 2013 update of the evidence base. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2013;162:193-204.

14. Noon L. Prophylactic inoculation against hay fever. Lancet. 1911;177:1572-1573.

15. Purello-D’Ambrosio F, Gangemi S, Merendino RA, et al. Prevention of new sensitizations in monosensitized subjects submitted to specific immunotherapy or not: a retrospective study. Clin & Exper Allergy. 2001;31:1295-1302.

16. Durham SR, Walker SM, Varga EM, et al. Long-term clinical efficacy of grass-pollen immunotherapy. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:468-475.

17. Mohapatra SS, Qazi M, Hellermann G. Immunotherapy for allergies and asthma: present and future. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:276-288.

18. Calderon MA, Alves B, Jacobson M, et al. Allergen injection immunotherapy for seasonal allergic rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007; Iss 1, Art No: CD001936.

19. Scadding GK, Brostoff J. Low dose sublingual therapy in patients with allergic rhinitis due to house dust mite.Clin Allergy. 1986;16:483-491.

20. Canonica GW, Bousquet J, Casale T, et al. Sub-lingual immunotherapy: World Allergy Organization Position Paper 2009. Allergy. 2009;64 suppl 91:1-59.

21. Di Bona D, Plaia A, Scafidi V, et al. Efficacy of sublingual immunotherapy with grass allergens for seasonal allergic rhinitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:558-566.

22. Sikora JM, Tankersley MS; ACAAI Immunotherapy and Diagnostics Committee. Perception and practice of sublingual immunotherapy among practicing allergists in the United States: a follow-up survey. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;110:194-197.

CE/CME No: CR-1403

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Explain the pathophysiology and etiology of allergic rhinitis (AR).

• Describe the prevalence and types of AR.

• List the differential diagnoses for AR.

• Describe the historical and physical examination findings that are typical

of AR.

• Explain the indications for and types of allergy testing.

• Discuss the types of allergy desensitization therapies/immunotherapies.

FACULTY

Randy D. Danielsen is a Professor and Dean of the Arizona School of Health Sciences, A.T. Still University in Mesa, Arizona, and a long-time PA with the Arizona Asthma & Allergy Institute. Linda S. MacConnell is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Physician Assistant Studies at the Arizona School of Health Sciences, A.T. Still University, and a formally trained otolaryngology PA.

The authors have no financial disclosures to report.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Article begins on next page >>

Allergic rhinitis (AR), one of the most familiar complaints seen in primary care, is a common immunologic condition that occurs in genetically predisposed patients. AR is routinely treated through allergen avoidance and pharmacologic therapy. When these measures fail, however, immunologic treatment may be indicated. This review of AR and its treatment focuses on injection and oral immunotherapy.

Congestion; sneezing (particularly paroxysms); itchy nose, palate, and eyes; and runny nose are symptoms characteristic of allergic rhinitis (AR) seen every day in virtually all primary care offices. Patients are plagued not only by their symptoms, but also by AR-related sleep disturbances, resulting in fatigue and daytime sleepiness, irritability, and memory deficits. In children, these sleep disruptions may even cause behavioral disturbances. Depending on the cause, some patients may experience allergic symptoms only with outdoor environmental exposure and subsequent immunoglobulin E (IgE)–mediated responses to otherwise innocuous allergens, while others find that their symptoms are constant, occurring both indoors and out.

Although the prevalence of AR is increasing,1 allergies are certainly nothing new to humankind. In fact, hieroglyphics and Egyptian wall paintings have been discovered depicting a pharaoh dying from anaphylactic shock after receiving a wasp sting.2 In 1565, Leonardo Botallo described AR, calling it “rose catarrh” (mucous or phlegm) or “rose fever,” based on the mistaken idea that the symptoms were caused by rose pollen.2 John Babcock, an English physician, first diagnosed an upper respiratory disease that he called “hay fever” in 1819.

Seventy years later, Charles Blackley identified pollen as a cause of hay fever, documenting his findings in his 1873 book Experimental Researches on the Causes and Nature of Catarrhus Aestivus.2 Dr. Blackley performed the initial documented attempts at allergy desensitization treatments on himself—a willing patient, as he suffered from AR. He placed rye grass pollen onto his nasal mucosa, finding that after 30 minutes the nostril was completely occluded. He continued his experimentation by repeatedly exposing himself to pollen grains via abraded skin. Alas, he never noted any decrease in his symptoms.3

Presently, AR affects more than 55 million people in the United States4—approximately 10% to 30% of the adult population5 and more than 40% of children.6 The rising prevalence of AR is of concern in older adults, who tend to have related comorbidities (eg, chronic sinusitis, asthma, and otitis media). In fact, AR is the fifth most common chronic disease in the US.7

AR and its treatment impose a great economic burden on the health care system, critical in these days of affordable health care. In fact, in 2005 in the US, the overall (direct medical and indirect) cost of AR was $11.2 billion.8 Direct costs derive from office visits, diagnostic testing, and therapeutics. Costs are considerably higher when indirect expenses, including decreased productivity, missed school and missed workdays to care for children, and costs of travel to medical appointments, are included. In the US, approximately 3.5 million workdays and 2 million school days are lost each year due to AR.9 Decreases in productivity cost an estimated $600 per affected employee per year, all of which results in AR being the fifth costliest chronic disease.10,11

On the next page: Pathophysiology and examination >>

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

AR is an immunologic disorder that occurs in genetically susceptible individuals who produce allergen-specific IgE antibody responses after environmental exposures. The IgE-mediated response causes inflammation of the nasal mucosa. Compared to controls, individuals with AR demonstrate increased amounts of IgE antibodies in the nasal mucosa.11 IgE binds to basophils in the bloodstream and mast cells in tissue. Allergens then attach to IgE on basophils and mast cells, which release histamines, prostaglandins, cytokines, and leukotrienes, with histamine being the most significant mediator in the inflammatory response.

In response to allergy-provoking substances, patients experience immediate- and late-phase symptoms. Symptoms of each stage are similar, but congestion is the hallmark of the late phase. While both phases are clinically important because of their contribution to the patient’s symptoms, most patients experience continued exposure to allergens, resulting in constant, overlapping symptoms.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Patients with AR relate a history of congestion, excessive mucous production, itchy, watery eyes, bouts of sneezing, and more systemic symptoms, such as headache, malaise, and excessive fatigue. It is important to evaluate the degree and duration of the symptoms, noting patterns and triggers, in an effort to confirm the diagnosis and to help the patient evaluate treatment options.

When taking the patient history, always review the family history, which is often notable for allergies and other atopic diseases. Be sure to ask about medications and recreational drug use; a number of substances have been implicated in the development of rhinitis, including anticholinergic medications, oxymetazoline (when overused), and cocaine. Also, question the patient about self-medication and treatment to determine what may or may not have provided relief. Further questioning may also reveal a history of comorbidities, including contact dermatitis, asthma, eczema, and chronic sinusitis.

The physical examination of the patient with rhinitis begins with observation of the patient’s outward appearance, which may reveal allergic shiners (dark to purplish areas under the eyes), conjunctivitis, an allergic salute (a transverse crease of the nose caused by upward rubbing of an itchy nose), mouth breathing, and a generally tired appearance. The nasal turbinates are swollen and often pale. Mucous secretions are usually thin and clear. Enlarged tonsils and posterior nasal drainage may be visualized. The types of AR are listed in Table 1.

On the next page: Diagnosis and treatment >>

DIAGNOSIS

Most of the clues needed to arrive at a diagnosis are discovered by taking a careful history and completing a physical examination. AR frequently underlies and/or coexists with acute upper respiratory infection (URI) and acute and chronic sinusitis. Differentiating acute URI and acute sinusitis from AR is usually relatively straightforward, based on the symptoms of the illness. The diagnosis of chronic sinusitis is made by radiologic imaging with CT scan.

Distinguishing nonallergic rhinitis (NAR) from AR can be far more difficult, because the symptoms of these conditions are similar and chronic in nature (see Table 2). Empiric treatment for AR may be attempted; however, further testing is often needed to differentiate the two. At this point, clinicians may choose to proceed with specific IgE blood tests. Alternatively, many medical practices are prepared to perform or refer for allergy skin testing.

TREATMENT

Avoidance of known triggers is the cornerstone of allergy treatment. Currently, the most effective pharmaceutical treatment for the majority of AR symptoms is inhaled nasal corticosteroids. Although less effective than corticosteroids, antihistamines—both nasal and oral—are a recommended addition to the regimen if the adverse effects and costs to the patient are tolerable. Other treatments include the leukotriene receptor antagonists, intranasal formulations of cromolyn, and the anticholinergic ipratropium bromide nasal spray, which is effective primarily on watery rhinorrhea. If symptoms are not controlled with medication, allergy immunotherapy (AI), the only known disease-modifying therapy for AR, may be indicated.

On the next page: Allergy testing >>

ALLERGY TESTING

In order to distinguish between AR and NAR and to direct treatment toward specific allergen avoidance and immunotherapy, providers have the choice of ordering in vitro blood IgE testing (to measure the antibodies that mediate an allergic response) or in vivo allergy skin testing (to measure the immune response to allergens that induces an allergic atopic reaction). Allergy testing is not a contemporary concept; the first allergy testing was documented in 1656 when Pierre Borel applied egg to a patient’s skin, which exhibited an allergic reaction.2

Allergy skin testing consists of applying multiple allergens to the skin of the patient’s forearms via tiny pinpricks while watching for immediate hypersensitivity reactions. The test begins with the placement of a drop of histamine to serve as a control. If after 10 minutes of watchful waiting the patient develops a reaction to the histamine (a positive test result), it is appropriate to test for antigens by placing drops of suspected allergen extracts on the skin.

After a period of time (usually 20 to 30 minutes), the area is inspected for allergic reaction. An immediate (early phase) wheal and flare (surrounding erythema) reaction may develop. This positive reaction indicates the presence of a mast cell–bound IgE antibody specific to the tested allergen. The size of the reactions is measured in millimeters, allowing for comparison to the histamine control.

A list of the commonly tested antigens in Arizona, as an example, is shown in Table 3. Antigens vary geographically and even from practice to practice. For up-to-date information on pollen counts by region, visit the American Academy of Allergy Asthma & Immunology Web site (see “Pollen Counts”).

On the next page: Patient selection and allergy immunotherapy >>

Patient Selection

After the clinician has determined that there is a high likelihood that the diagnosis is AR, allergy testing, needed to guide AI, is appropriate. Although not true of specific IgE testing, the accuracy of allergy skin testing results can be adversely affected by several medications. For example, some practitioners may choose to stop first-generation antihistamines two to three days before testing. It is generally accepted that the newer, second-generation antihistamines, which can affect skin-testing results longer, be stopped a week prior to testing.

Patients should be reminded that OTC sleep aids frequently contain antihistamines (particularly diphenhydramine) and that they must be discontinued prior to testing as well. Histamine H2-receptor antagonists such as cimetidine and ranitidine may be stopped a day or two before testing. Although β-blockers are only relatively contraindicated in both allergy testing and AI, many health care providers avoid testing and AI in patients taking oral and/or topical (eye drops) β-blocker therapy. Ultimately, the decision is made by individual health care practices.

In vivo allergy skin testing should not be performed on patients taking tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Patients with significant cardiovascular disease should not undergo testing or treatment. Pregnancy is a relative contraindication, and allergy skin testing and AI are done only with obstetrician approval. Most allergists avoid allergy skin testing in pregnant women, however, because use of epinephrine, if required, introduces the risk for preterm labor.12,13 Special consideration should also be given to patients with immune deficiencies.

Setting for Allergy Evaluation and Treatment

Recently, many primary care practices have added allergy evaluation and management to the procedures and treatments they offer; however, evaluations and testing traditionally have been performed by allergy and immunology specialists, many of whom include PAs and NPs on their staff. PAs and NPs frequently manage the practices’ allergy programs. Allergists who are listed as American Board of Allergy and Immunology (ABAI)–certified have successfully passed the ABAI’s certifying examination. Other medical specialists, including otolaryngologists and the primary care specialties, are also well placed to evaluate patients with common allergy symptoms and provide appropriate treatment.

Allergy Immunotherapy

AI has now become more efficacious, safer, and more tolerable for the patient than when it was first introduced in 1911. At that time, Leonard Noon authored a brief article claiming that allergen-specific injections could modify AR. Unfortunately, Noon died at age 36 from tuberculosis, but his work was carried on by his associate, John Freeman. Together, they established the guidelines upon which contemporary AI is based, including the protocol to gradually increase the dose of allergen serum, starting with initial weekly to biweekly injections. They also voiced warnings about the potential for anaphylaxis.14 To this day, immunotherapy is still accomplished by the gradual administration of increasing amounts of the allergen to which the patient is sensitive. This tempers the abnormal immune response to that allergen, easing allergic symptoms.

In patients with IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions, confirmed by history, physical examination, and allergy skin testing, immunotherapy can be very effective. The results of immunotherapy may last for years and may even prevent the allergic march, the progression of allergic disease experienced by many patients that frequently begins early in life.15 This includes other allergy-related conditions, such as asthma and eczema (atopic dermatitis), and the acquisition of additional new allergies, including those to foods. AI also has been shown to decrease the frequency of comorbidities such as asthma.5 In addition, AI is used in carefully screened patients who desire to reduce the dosages of medication required to control their symptoms.

In a study published in 1999, Durham and colleagues clarified the questions surrounding the amount of time required for ongoing immunotherapy. They found that the desensitization and tolerance to allergens achieved by AI can last up to three years after a three- to four-year course of therapy. They also found that treatment should not start until an allergic component is identified by allergy skin testing or serum tests for allergen-specific IgE.16

As effective as immunotherapy has been documented to be, it is underused as a therapeutic modality. There are only 2 to 3 million patients receiving subcutaneous immunotherapy out of more than 55 million patients with AR.17

On the next page: Types of allergy immunotherapy >>

Types of AI

There are two categories of allergen desensitization therapy. The most common method is subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT), the so-called allergy shots. Less common and still somewhat controversial is sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT). Immunotherapy should be considered for patients who have secondary complications (eg, sinusitis, otitis) or asthma with allergies, or those in whom avoidance measures and medications fail. SCIT or SLIT may be desirable for patients with AR who have difficulty taking regular medications.

Subcutaneous immunotherapy. Currently, SCIT is the most recognized immunotherapy and the only one currently reimbursed by insurance. The procedure involves the subcutaneous injection of increasing doses of therapeutic solutions to which a patient has demonstrated sensitivity. The indications for this treatment are usually inhaled allergens, such as pollens and animal dander. SCIT may also be valuable in patients with asthma and atopic dermatitis.

The most common adverse reaction to allergy injections is a large localized reaction—primarily erythema, pruritus, discomfort, and possibly edema. Severe systemic reactions are extremely rare, with near-fatal to fatal reactions occurring at the rate of only 5.4 per million injections.11 The majority of these rare, albeit serious, complications are caused by higher-than-normal levels of pollen in the environment and dosing errors.11 Because of the uncommon but significant complications, patients undergoing immunotherapy should always receive injections in a medical office equipped with appropriate equipment and staff trained in handling anaphylaxis. It is standard protocol for patients to remain in the office for 30 minutes after administration for observation. Some clinicians prescribe epinephrine injectors (Epi-Pens) for patients to bring to every appointment as a condition for receiving their shot. Because of continuing controversy on this point, others only employ this requirement if the patient has a history of an adverse reaction.

Various protocols exist for the up-dosing of immunotherapy, most of which recommend weekly to twice-weekly injections prior to initiating maintenance therapy. Costs, risks, and benefits must be carefully considered and discussed with the patient prior to initiating immunotherapy.

Many insurance companies reimburse for immunotherapy, with varying copayments. Additionally, the time commitment may be taxing on the patient’s busy schedule. Weekly or biweekly appointments are required initially, and the patient must remain on site for half an hour. Although direct costs of SCIT are relatively easily measured and perhaps compensated, the indirect costs of time spent commuting and at the clinic are less tangible.

Success rates with SCIT may be more than 70% for certain allergens,18 but it is a long-term process with initial improvement often not seen until after six to 12 months of therapy. The benefits of therapy lead not only to reduction and suppression in symptoms (and medication), but also to reduction in comorbidity and lost school or workdays and improvement in quality of life.

Sublingual immunotherapy. Because of the possible safety concerns surrounding SCIT, along with problems relating to patient adherence to weekly office visits, alternative means of achieving allergen desensitization have been implemented. One of these methods, SLIT, has been increasingly supported by clinical evidence, especially in Europe. This therapy consists of applying aqueous allergen extract to the sublingual or oral mucosa, allowing it to be absorbed into the body. Subsequent swallowing of the extract allows the gut to respond with an increase in tolerance. The changes that result from this type of administration appear to be similar to those observed with SCIT.

SLIT has been in use for almost 30 years; the first published controlled study of this therapy was done in 1986 by Scadding and Brostoff.19 The World Allergy Organization recognized the safety and clinical efficacy of SLIT in 2009 after reviewing more than 60 controlled studies.20

A 2010 meta-analysis, reviewing documents from the prior 20 years of research, showed that SLIT decreased medication use and improved symptoms.21 Generally, SLIT was found to be more effective in adults than children. It was not as effective in patients with asthma as in those who were asthma-free. The timing of initiation of SLIT was also an important finding; when SLIT is used for grass pollen allergy, it should be started at least three months before the beginning of grass season.21 For other allergens, SLIT can be started at any time.

Because it is a home-based treatment, SLIT is far more convenient for the patient and therefore has become more popular in the US in the past decade. Its increased safety also contributes to its popularity. Although SLIT is commonly used in many parts of the world, at this writing, medications used in SLIT have not yet been approved by the US FDA. The FDA is currently reviewing two oral tablets for SLIT, and it is expected that its use in the US will increase once an approved product becomes available.22

It should be noted that no studies have directly compared SCIT and SLIT. Careful consultation between clinician and patient can help the patient arrive at the most appropriate modality for his or her condition based on symptomatology and lifestyle needs.

On the next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

For most patients, AR has little morbidity; however, for some whose rhinitis is moderate to severe, the complications can be a concern. If symptoms are not controlled with avoidance and/or medication, AI may be indicated. It comprises the building up of tolerance to the specific allergens as identified by allergy skin testing or in vitro specific IgE testing. AI, whether SCIT or SLIT, is the only means of altering the abnormal immune system response that underlies AR. Treatment may last as long as three to four years, which provides long-term efficacy of at least three years after cessation of therapy. The long-term prognosis for AR is excellent.

Appreciation is extended to Roxy Irestone, RN, Arizona Asthma & Allergy Institute, for her assistance is gathering factual information for this article.

CE/CME No: CR-1403

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Explain the pathophysiology and etiology of allergic rhinitis (AR).

• Describe the prevalence and types of AR.

• List the differential diagnoses for AR.

• Describe the historical and physical examination findings that are typical

of AR.

• Explain the indications for and types of allergy testing.

• Discuss the types of allergy desensitization therapies/immunotherapies.

FACULTY

Randy D. Danielsen is a Professor and Dean of the Arizona School of Health Sciences, A.T. Still University in Mesa, Arizona, and a long-time PA with the Arizona Asthma & Allergy Institute. Linda S. MacConnell is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Physician Assistant Studies at the Arizona School of Health Sciences, A.T. Still University, and a formally trained otolaryngology PA.

The authors have no financial disclosures to report.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

Article begins on next page >>

Allergic rhinitis (AR), one of the most familiar complaints seen in primary care, is a common immunologic condition that occurs in genetically predisposed patients. AR is routinely treated through allergen avoidance and pharmacologic therapy. When these measures fail, however, immunologic treatment may be indicated. This review of AR and its treatment focuses on injection and oral immunotherapy.

Congestion; sneezing (particularly paroxysms); itchy nose, palate, and eyes; and runny nose are symptoms characteristic of allergic rhinitis (AR) seen every day in virtually all primary care offices. Patients are plagued not only by their symptoms, but also by AR-related sleep disturbances, resulting in fatigue and daytime sleepiness, irritability, and memory deficits. In children, these sleep disruptions may even cause behavioral disturbances. Depending on the cause, some patients may experience allergic symptoms only with outdoor environmental exposure and subsequent immunoglobulin E (IgE)–mediated responses to otherwise innocuous allergens, while others find that their symptoms are constant, occurring both indoors and out.

Although the prevalence of AR is increasing,1 allergies are certainly nothing new to humankind. In fact, hieroglyphics and Egyptian wall paintings have been discovered depicting a pharaoh dying from anaphylactic shock after receiving a wasp sting.2 In 1565, Leonardo Botallo described AR, calling it “rose catarrh” (mucous or phlegm) or “rose fever,” based on the mistaken idea that the symptoms were caused by rose pollen.2 John Babcock, an English physician, first diagnosed an upper respiratory disease that he called “hay fever” in 1819.

Seventy years later, Charles Blackley identified pollen as a cause of hay fever, documenting his findings in his 1873 book Experimental Researches on the Causes and Nature of Catarrhus Aestivus.2 Dr. Blackley performed the initial documented attempts at allergy desensitization treatments on himself—a willing patient, as he suffered from AR. He placed rye grass pollen onto his nasal mucosa, finding that after 30 minutes the nostril was completely occluded. He continued his experimentation by repeatedly exposing himself to pollen grains via abraded skin. Alas, he never noted any decrease in his symptoms.3

Presently, AR affects more than 55 million people in the United States4—approximately 10% to 30% of the adult population5 and more than 40% of children.6 The rising prevalence of AR is of concern in older adults, who tend to have related comorbidities (eg, chronic sinusitis, asthma, and otitis media). In fact, AR is the fifth most common chronic disease in the US.7

AR and its treatment impose a great economic burden on the health care system, critical in these days of affordable health care. In fact, in 2005 in the US, the overall (direct medical and indirect) cost of AR was $11.2 billion.8 Direct costs derive from office visits, diagnostic testing, and therapeutics. Costs are considerably higher when indirect expenses, including decreased productivity, missed school and missed workdays to care for children, and costs of travel to medical appointments, are included. In the US, approximately 3.5 million workdays and 2 million school days are lost each year due to AR.9 Decreases in productivity cost an estimated $600 per affected employee per year, all of which results in AR being the fifth costliest chronic disease.10,11

On the next page: Pathophysiology and examination >>

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

AR is an immunologic disorder that occurs in genetically susceptible individuals who produce allergen-specific IgE antibody responses after environmental exposures. The IgE-mediated response causes inflammation of the nasal mucosa. Compared to controls, individuals with AR demonstrate increased amounts of IgE antibodies in the nasal mucosa.11 IgE binds to basophils in the bloodstream and mast cells in tissue. Allergens then attach to IgE on basophils and mast cells, which release histamines, prostaglandins, cytokines, and leukotrienes, with histamine being the most significant mediator in the inflammatory response.

In response to allergy-provoking substances, patients experience immediate- and late-phase symptoms. Symptoms of each stage are similar, but congestion is the hallmark of the late phase. While both phases are clinically important because of their contribution to the patient’s symptoms, most patients experience continued exposure to allergens, resulting in constant, overlapping symptoms.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Patients with AR relate a history of congestion, excessive mucous production, itchy, watery eyes, bouts of sneezing, and more systemic symptoms, such as headache, malaise, and excessive fatigue. It is important to evaluate the degree and duration of the symptoms, noting patterns and triggers, in an effort to confirm the diagnosis and to help the patient evaluate treatment options.

When taking the patient history, always review the family history, which is often notable for allergies and other atopic diseases. Be sure to ask about medications and recreational drug use; a number of substances have been implicated in the development of rhinitis, including anticholinergic medications, oxymetazoline (when overused), and cocaine. Also, question the patient about self-medication and treatment to determine what may or may not have provided relief. Further questioning may also reveal a history of comorbidities, including contact dermatitis, asthma, eczema, and chronic sinusitis.

The physical examination of the patient with rhinitis begins with observation of the patient’s outward appearance, which may reveal allergic shiners (dark to purplish areas under the eyes), conjunctivitis, an allergic salute (a transverse crease of the nose caused by upward rubbing of an itchy nose), mouth breathing, and a generally tired appearance. The nasal turbinates are swollen and often pale. Mucous secretions are usually thin and clear. Enlarged tonsils and posterior nasal drainage may be visualized. The types of AR are listed in Table 1.

On the next page: Diagnosis and treatment >>

DIAGNOSIS

Most of the clues needed to arrive at a diagnosis are discovered by taking a careful history and completing a physical examination. AR frequently underlies and/or coexists with acute upper respiratory infection (URI) and acute and chronic sinusitis. Differentiating acute URI and acute sinusitis from AR is usually relatively straightforward, based on the symptoms of the illness. The diagnosis of chronic sinusitis is made by radiologic imaging with CT scan.

Distinguishing nonallergic rhinitis (NAR) from AR can be far more difficult, because the symptoms of these conditions are similar and chronic in nature (see Table 2). Empiric treatment for AR may be attempted; however, further testing is often needed to differentiate the two. At this point, clinicians may choose to proceed with specific IgE blood tests. Alternatively, many medical practices are prepared to perform or refer for allergy skin testing.

TREATMENT

Avoidance of known triggers is the cornerstone of allergy treatment. Currently, the most effective pharmaceutical treatment for the majority of AR symptoms is inhaled nasal corticosteroids. Although less effective than corticosteroids, antihistamines—both nasal and oral—are a recommended addition to the regimen if the adverse effects and costs to the patient are tolerable. Other treatments include the leukotriene receptor antagonists, intranasal formulations of cromolyn, and the anticholinergic ipratropium bromide nasal spray, which is effective primarily on watery rhinorrhea. If symptoms are not controlled with medication, allergy immunotherapy (AI), the only known disease-modifying therapy for AR, may be indicated.

On the next page: Allergy testing >>

ALLERGY TESTING

In order to distinguish between AR and NAR and to direct treatment toward specific allergen avoidance and immunotherapy, providers have the choice of ordering in vitro blood IgE testing (to measure the antibodies that mediate an allergic response) or in vivo allergy skin testing (to measure the immune response to allergens that induces an allergic atopic reaction). Allergy testing is not a contemporary concept; the first allergy testing was documented in 1656 when Pierre Borel applied egg to a patient’s skin, which exhibited an allergic reaction.2

Allergy skin testing consists of applying multiple allergens to the skin of the patient’s forearms via tiny pinpricks while watching for immediate hypersensitivity reactions. The test begins with the placement of a drop of histamine to serve as a control. If after 10 minutes of watchful waiting the patient develops a reaction to the histamine (a positive test result), it is appropriate to test for antigens by placing drops of suspected allergen extracts on the skin.

After a period of time (usually 20 to 30 minutes), the area is inspected for allergic reaction. An immediate (early phase) wheal and flare (surrounding erythema) reaction may develop. This positive reaction indicates the presence of a mast cell–bound IgE antibody specific to the tested allergen. The size of the reactions is measured in millimeters, allowing for comparison to the histamine control.

A list of the commonly tested antigens in Arizona, as an example, is shown in Table 3. Antigens vary geographically and even from practice to practice. For up-to-date information on pollen counts by region, visit the American Academy of Allergy Asthma & Immunology Web site (see “Pollen Counts”).

On the next page: Patient selection and allergy immunotherapy >>

Patient Selection

After the clinician has determined that there is a high likelihood that the diagnosis is AR, allergy testing, needed to guide AI, is appropriate. Although not true of specific IgE testing, the accuracy of allergy skin testing results can be adversely affected by several medications. For example, some practitioners may choose to stop first-generation antihistamines two to three days before testing. It is generally accepted that the newer, second-generation antihistamines, which can affect skin-testing results longer, be stopped a week prior to testing.

Patients should be reminded that OTC sleep aids frequently contain antihistamines (particularly diphenhydramine) and that they must be discontinued prior to testing as well. Histamine H2-receptor antagonists such as cimetidine and ranitidine may be stopped a day or two before testing. Although β-blockers are only relatively contraindicated in both allergy testing and AI, many health care providers avoid testing and AI in patients taking oral and/or topical (eye drops) β-blocker therapy. Ultimately, the decision is made by individual health care practices.

In vivo allergy skin testing should not be performed on patients taking tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Patients with significant cardiovascular disease should not undergo testing or treatment. Pregnancy is a relative contraindication, and allergy skin testing and AI are done only with obstetrician approval. Most allergists avoid allergy skin testing in pregnant women, however, because use of epinephrine, if required, introduces the risk for preterm labor.12,13 Special consideration should also be given to patients with immune deficiencies.

Setting for Allergy Evaluation and Treatment

Recently, many primary care practices have added allergy evaluation and management to the procedures and treatments they offer; however, evaluations and testing traditionally have been performed by allergy and immunology specialists, many of whom include PAs and NPs on their staff. PAs and NPs frequently manage the practices’ allergy programs. Allergists who are listed as American Board of Allergy and Immunology (ABAI)–certified have successfully passed the ABAI’s certifying examination. Other medical specialists, including otolaryngologists and the primary care specialties, are also well placed to evaluate patients with common allergy symptoms and provide appropriate treatment.

Allergy Immunotherapy

AI has now become more efficacious, safer, and more tolerable for the patient than when it was first introduced in 1911. At that time, Leonard Noon authored a brief article claiming that allergen-specific injections could modify AR. Unfortunately, Noon died at age 36 from tuberculosis, but his work was carried on by his associate, John Freeman. Together, they established the guidelines upon which contemporary AI is based, including the protocol to gradually increase the dose of allergen serum, starting with initial weekly to biweekly injections. They also voiced warnings about the potential for anaphylaxis.14 To this day, immunotherapy is still accomplished by the gradual administration of increasing amounts of the allergen to which the patient is sensitive. This tempers the abnormal immune response to that allergen, easing allergic symptoms.

In patients with IgE-mediated hypersensitivity reactions, confirmed by history, physical examination, and allergy skin testing, immunotherapy can be very effective. The results of immunotherapy may last for years and may even prevent the allergic march, the progression of allergic disease experienced by many patients that frequently begins early in life.15 This includes other allergy-related conditions, such as asthma and eczema (atopic dermatitis), and the acquisition of additional new allergies, including those to foods. AI also has been shown to decrease the frequency of comorbidities such as asthma.5 In addition, AI is used in carefully screened patients who desire to reduce the dosages of medication required to control their symptoms.

In a study published in 1999, Durham and colleagues clarified the questions surrounding the amount of time required for ongoing immunotherapy. They found that the desensitization and tolerance to allergens achieved by AI can last up to three years after a three- to four-year course of therapy. They also found that treatment should not start until an allergic component is identified by allergy skin testing or serum tests for allergen-specific IgE.16

As effective as immunotherapy has been documented to be, it is underused as a therapeutic modality. There are only 2 to 3 million patients receiving subcutaneous immunotherapy out of more than 55 million patients with AR.17

On the next page: Types of allergy immunotherapy >>

Types of AI

There are two categories of allergen desensitization therapy. The most common method is subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT), the so-called allergy shots. Less common and still somewhat controversial is sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT). Immunotherapy should be considered for patients who have secondary complications (eg, sinusitis, otitis) or asthma with allergies, or those in whom avoidance measures and medications fail. SCIT or SLIT may be desirable for patients with AR who have difficulty taking regular medications.

Subcutaneous immunotherapy. Currently, SCIT is the most recognized immunotherapy and the only one currently reimbursed by insurance. The procedure involves the subcutaneous injection of increasing doses of therapeutic solutions to which a patient has demonstrated sensitivity. The indications for this treatment are usually inhaled allergens, such as pollens and animal dander. SCIT may also be valuable in patients with asthma and atopic dermatitis.

The most common adverse reaction to allergy injections is a large localized reaction—primarily erythema, pruritus, discomfort, and possibly edema. Severe systemic reactions are extremely rare, with near-fatal to fatal reactions occurring at the rate of only 5.4 per million injections.11 The majority of these rare, albeit serious, complications are caused by higher-than-normal levels of pollen in the environment and dosing errors.11 Because of the uncommon but significant complications, patients undergoing immunotherapy should always receive injections in a medical office equipped with appropriate equipment and staff trained in handling anaphylaxis. It is standard protocol for patients to remain in the office for 30 minutes after administration for observation. Some clinicians prescribe epinephrine injectors (Epi-Pens) for patients to bring to every appointment as a condition for receiving their shot. Because of continuing controversy on this point, others only employ this requirement if the patient has a history of an adverse reaction.

Various protocols exist for the up-dosing of immunotherapy, most of which recommend weekly to twice-weekly injections prior to initiating maintenance therapy. Costs, risks, and benefits must be carefully considered and discussed with the patient prior to initiating immunotherapy.

Many insurance companies reimburse for immunotherapy, with varying copayments. Additionally, the time commitment may be taxing on the patient’s busy schedule. Weekly or biweekly appointments are required initially, and the patient must remain on site for half an hour. Although direct costs of SCIT are relatively easily measured and perhaps compensated, the indirect costs of time spent commuting and at the clinic are less tangible.

Success rates with SCIT may be more than 70% for certain allergens,18 but it is a long-term process with initial improvement often not seen until after six to 12 months of therapy. The benefits of therapy lead not only to reduction and suppression in symptoms (and medication), but also to reduction in comorbidity and lost school or workdays and improvement in quality of life.

Sublingual immunotherapy. Because of the possible safety concerns surrounding SCIT, along with problems relating to patient adherence to weekly office visits, alternative means of achieving allergen desensitization have been implemented. One of these methods, SLIT, has been increasingly supported by clinical evidence, especially in Europe. This therapy consists of applying aqueous allergen extract to the sublingual or oral mucosa, allowing it to be absorbed into the body. Subsequent swallowing of the extract allows the gut to respond with an increase in tolerance. The changes that result from this type of administration appear to be similar to those observed with SCIT.

SLIT has been in use for almost 30 years; the first published controlled study of this therapy was done in 1986 by Scadding and Brostoff.19 The World Allergy Organization recognized the safety and clinical efficacy of SLIT in 2009 after reviewing more than 60 controlled studies.20

A 2010 meta-analysis, reviewing documents from the prior 20 years of research, showed that SLIT decreased medication use and improved symptoms.21 Generally, SLIT was found to be more effective in adults than children. It was not as effective in patients with asthma as in those who were asthma-free. The timing of initiation of SLIT was also an important finding; when SLIT is used for grass pollen allergy, it should be started at least three months before the beginning of grass season.21 For other allergens, SLIT can be started at any time.

Because it is a home-based treatment, SLIT is far more convenient for the patient and therefore has become more popular in the US in the past decade. Its increased safety also contributes to its popularity. Although SLIT is commonly used in many parts of the world, at this writing, medications used in SLIT have not yet been approved by the US FDA. The FDA is currently reviewing two oral tablets for SLIT, and it is expected that its use in the US will increase once an approved product becomes available.22

It should be noted that no studies have directly compared SCIT and SLIT. Careful consultation between clinician and patient can help the patient arrive at the most appropriate modality for his or her condition based on symptomatology and lifestyle needs.

On the next page: Conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

For most patients, AR has little morbidity; however, for some whose rhinitis is moderate to severe, the complications can be a concern. If symptoms are not controlled with avoidance and/or medication, AI may be indicated. It comprises the building up of tolerance to the specific allergens as identified by allergy skin testing or in vitro specific IgE testing. AI, whether SCIT or SLIT, is the only means of altering the abnormal immune system response that underlies AR. Treatment may last as long as three to four years, which provides long-term efficacy of at least three years after cessation of therapy. The long-term prognosis for AR is excellent.

Appreciation is extended to Roxy Irestone, RN, Arizona Asthma & Allergy Institute, for her assistance is gathering factual information for this article.

1. Sibbald B, Rink E, D’Souza M. Is the prevalence of atopy increasing? Br J Gen Pract. 1990;40(337):338-340.

2. History of allergy. Allergy and Asthma Specialists Web site. www.allergyasthmaspecialist.com/allergy-and-asthma-clinic-of-kenosha-sc-education.htm. Accessed February 14, 2014.

3. Blackley CH. Hay Fever: Its Causes, Treatment, and Effective Prevention. London, England: Balliere, Tindall, & Cox; 1880.

4. Settipane RA. Rhinitis: a dose of epidemiological reality. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2003;24(3):147-154.

5. Wallace DV, Dykewicz MS, Bernstein DI, et al. The diagnosis and management of rhinitis: an updated practice parameter. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122(2 suppl):S1-S84.

6. Wright AL, Holberg CJ, Halonen M, et al. Epidemiology of physician-diagnosed allergic rhinitis in childhood. Pediatrics. 1994;94(6):895 -901.

7. Bernstein JA. Allergic and mixed rhinitis: epidemiology and natural history. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010;31:365-369.

8. Meltzer EO, Bukstein DA. The economic impact of allergic rhinitis and current guidelines for treatment. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011; 106(suppl 2):S12-S16.

9. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. Task force on allergic disorders: promoting best practice: raising the standard of care for patients with allergic disorders. Executive summary report. 1998.

10. Nathan RA. The burden of allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2007; 28:3-9.

11. Tran NP, Vickery J, Blaiss MS. Management of rhinitis: allergic and non-allergic. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3:148-156.

12. Disease Summaries: Allergic Diseases and Asthma in Pregnancy. World Allergy Organization. www.worldallergy.org/professional/allergic_

diseases_center/allergy_in_pregnancy/. Accessed February 14, 2014.

13. Simons FE, Ardusso LR, Dimov V, et al. World Allergy Organization Anaphylaxis Guidelines: 2013 update of the evidence base. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2013;162:193-204.

14. Noon L. Prophylactic inoculation against hay fever. Lancet. 1911;177:1572-1573.

15. Purello-D’Ambrosio F, Gangemi S, Merendino RA, et al. Prevention of new sensitizations in monosensitized subjects submitted to specific immunotherapy or not: a retrospective study. Clin & Exper Allergy. 2001;31:1295-1302.

16. Durham SR, Walker SM, Varga EM, et al. Long-term clinical efficacy of grass-pollen immunotherapy. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:468-475.

17. Mohapatra SS, Qazi M, Hellermann G. Immunotherapy for allergies and asthma: present and future. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:276-288.

18. Calderon MA, Alves B, Jacobson M, et al. Allergen injection immunotherapy for seasonal allergic rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007; Iss 1, Art No: CD001936.

19. Scadding GK, Brostoff J. Low dose sublingual therapy in patients with allergic rhinitis due to house dust mite.Clin Allergy. 1986;16:483-491.

20. Canonica GW, Bousquet J, Casale T, et al. Sub-lingual immunotherapy: World Allergy Organization Position Paper 2009. Allergy. 2009;64 suppl 91:1-59.

21. Di Bona D, Plaia A, Scafidi V, et al. Efficacy of sublingual immunotherapy with grass allergens for seasonal allergic rhinitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:558-566.

22. Sikora JM, Tankersley MS; ACAAI Immunotherapy and Diagnostics Committee. Perception and practice of sublingual immunotherapy among practicing allergists in the United States: a follow-up survey. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;110:194-197.

1. Sibbald B, Rink E, D’Souza M. Is the prevalence of atopy increasing? Br J Gen Pract. 1990;40(337):338-340.

2. History of allergy. Allergy and Asthma Specialists Web site. www.allergyasthmaspecialist.com/allergy-and-asthma-clinic-of-kenosha-sc-education.htm. Accessed February 14, 2014.

3. Blackley CH. Hay Fever: Its Causes, Treatment, and Effective Prevention. London, England: Balliere, Tindall, & Cox; 1880.

4. Settipane RA. Rhinitis: a dose of epidemiological reality. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2003;24(3):147-154.

5. Wallace DV, Dykewicz MS, Bernstein DI, et al. The diagnosis and management of rhinitis: an updated practice parameter. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122(2 suppl):S1-S84.

6. Wright AL, Holberg CJ, Halonen M, et al. Epidemiology of physician-diagnosed allergic rhinitis in childhood. Pediatrics. 1994;94(6):895 -901.

7. Bernstein JA. Allergic and mixed rhinitis: epidemiology and natural history. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010;31:365-369.

8. Meltzer EO, Bukstein DA. The economic impact of allergic rhinitis and current guidelines for treatment. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011; 106(suppl 2):S12-S16.

9. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. Task force on allergic disorders: promoting best practice: raising the standard of care for patients with allergic disorders. Executive summary report. 1998.

10. Nathan RA. The burden of allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2007; 28:3-9.

11. Tran NP, Vickery J, Blaiss MS. Management of rhinitis: allergic and non-allergic. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3:148-156.

12. Disease Summaries: Allergic Diseases and Asthma in Pregnancy. World Allergy Organization. www.worldallergy.org/professional/allergic_

diseases_center/allergy_in_pregnancy/. Accessed February 14, 2014.

13. Simons FE, Ardusso LR, Dimov V, et al. World Allergy Organization Anaphylaxis Guidelines: 2013 update of the evidence base. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2013;162:193-204.

14. Noon L. Prophylactic inoculation against hay fever. Lancet. 1911;177:1572-1573.

15. Purello-D’Ambrosio F, Gangemi S, Merendino RA, et al. Prevention of new sensitizations in monosensitized subjects submitted to specific immunotherapy or not: a retrospective study. Clin & Exper Allergy. 2001;31:1295-1302.

16. Durham SR, Walker SM, Varga EM, et al. Long-term clinical efficacy of grass-pollen immunotherapy. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:468-475.

17. Mohapatra SS, Qazi M, Hellermann G. Immunotherapy for allergies and asthma: present and future. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:276-288.

18. Calderon MA, Alves B, Jacobson M, et al. Allergen injection immunotherapy for seasonal allergic rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007; Iss 1, Art No: CD001936.

19. Scadding GK, Brostoff J. Low dose sublingual therapy in patients with allergic rhinitis due to house dust mite.Clin Allergy. 1986;16:483-491.

20. Canonica GW, Bousquet J, Casale T, et al. Sub-lingual immunotherapy: World Allergy Organization Position Paper 2009. Allergy. 2009;64 suppl 91:1-59.

21. Di Bona D, Plaia A, Scafidi V, et al. Efficacy of sublingual immunotherapy with grass allergens for seasonal allergic rhinitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:558-566.

22. Sikora JM, Tankersley MS; ACAAI Immunotherapy and Diagnostics Committee. Perception and practice of sublingual immunotherapy among practicing allergists in the United States: a follow-up survey. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;110:194-197.