User login

Defying Gravity

Last week, I fell in the driveway. I was taking the trash to the curb when I tripped and fell into the large blue recycling bin. Although it was 6 AM, I jumped up and looked around, horrified that someone may have seen my episode of gracelessness. I did bump my head and spent the rest of the day feeling stupid while rubbing the sore spot.

This incident, though more ego-bruising than anything, really conveyed to me the concerns of falling—not only for the elderly, but for all of us. So, not to be confused with the signature song from the musical Wicked sung by Elphaba (the Wicked Witch of the West) who has a desire to live without limits, my editorial this month discusses sobering limits in our everyday lives. And it does implicate gravity!

According to the National Council on Aging, about 1 in 3 adults ages 65 and older fall each year.1 Unintentional falls are the leading cause of nonfatal and fatal injuries (eg, hip fractures, head trauma) for older adults and result in about 57 fall-related deaths per 100,000 people per year.1,2 In 2013, more than 25,000 elderly individuals in the United States died from unintentional fall injuries.3

Who falls? Who doesn’t? But data indicate that among community-dwelling individuals older than 65, women fall more frequently than their male counterparts.4 But while injury and mortality rates rise dramatically for both sexes, regardless of race, after age 85, men in this age-group are more likely to die from a fall than are women.5

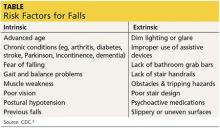

There are many risk factors that contribute to falling (see the table6), with gait and balance problems reported as the most significant contributor to falls among older adults.7 In addition, researchers report an increase in diseases linked to falls: diabetes, heart disease, stroke, arthritis, and Parkinson disease. In many cases, the medication used to treat the disease increases the risk for falling.8 It behooves every clinician to assess for and address any modifiable risk factors at each patient visit; one valuable resource is the CDC’s Compendium of Effective Fall Interventions: What Works for Community-Dwelling Older Adults.9

The issue of falling must be addressed on a larger scale, though. In response to the sobering statistics about falls, retirement communities, assisted living facilities, and nursing homes are trying to balance safety with their residents’ desire to live as they choose. They are hiring architects, interior designers, and engineers to find better ways to create safe living spaces, including installing floor lighting (similar to that on airplanes) that automatically illuminates a pathway to the bathroom when a resident gets out of bed.10

Continue for fall prevention in the community >>

But what about fall prevention in the community? A cost-benefit analysis revealed that community-based fall interventions are feasible and effective and provide a positive return on investment—no small consideration, given our current circumstances: Every 13 seconds, an older adult is treated in the emergency department for a fall, and every 29 minutes, an older adult dies from a fall-related injury.4,5 These estimates will likely rise as the population ages. The financial repercussions of falls and resultant morbidity and mortality may exceed $59 billion by 2020, according to the National Council on Aging.1 However, a 2013 report to Congress by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services indicated that older adults’ participation in a falls prevention program has resulted in reduced health care costs.11

Over the decades, many different approaches have been used to enhance older adults’ participation in such programs. I am proud to report that my university is among the many organizations to address this issue. A.T. Still University of Health Sciences (ATSU) was recently awarded a $95,000 grant by the Baptist Hospitals and Health Systems (BHHS) to support the university’s Fall Prevention Outreach program—the largest university-based fall-prevention initiative in the country.12

Since the program began in 2008, more than 2,000 Arizonans have completed the eight-week curriculum, which gives older adults the tools they need to prevent falls and manage the often-paralyzing fear of falling that comes with growing older. Since injuries sustained from falls are the leading cause of accidental injury deaths in Arizonans ages 65 and older, according to the state’s Department of Health Services, this program gives us an opportunity to have a direct impact on our community.

ATSU uses A Matter of Balance, a nationally recognized fall-prevention curriculum developed by Boston University.13 After receiving special training, teams of ATSU physician assistant, physical therapy, occupational therapy, athletic training, and audiology students offer the curriculum, at no cost, to older citizens at 41 community sites in the Greater Phoenix area. Collaborations with partners ranging from local municipalities to assisted-living communities make the program possible.

Part of the BHHS grant funded the certification of 15 master trainers who teach the two-day A Matter of Balance curriculum to the ATSU students and the community volunteers who will, in turn, lead the sessions. The grant also funded the expansion of the program to an additional 24 sites, for a total of 65.12

For those who wish to identify appropriate evidence-based fall prevention programs in their community, the CDC developed a new guide, Preventing Falls: A Guide to Implementing Effective Community-Based Fall Prevention Programs.14 This “how-to” outlines how community-based organizations initiate and maintain effective programs. It focuses on implementation of fall prevention programs and offers strategies on program planning, development, implementation, and evaluation. This resource provides a solid starting point for those seeking to address this increasingly prevalent issue.

How do you investigate the risk for falls with your patients? I would be interested in hearing from you what resources are available in your community. You can contact me at PAEditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

REFERENCES

1. Cameron K, Schneider E, Childress D, Gilchrist C. (2015). National Council on Aging Falls Free® National Action Plan (2015). www.ncoa.org/FallsFreeNAP. Accessed November 5, 2015.

2. CDC. Important Facts about Falls. www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/falls/adultfalls.html. Accessed November 5, 2015.

3. CDC National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Injury Prevention & Control: Data & Statistics (WISQARSTM). www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/. Accessed August 15, 2013.

4. Carande-Kulis I, Stevens JA, Florence CS, et al. Special Report from the CDC: a cost-benefit analysis of three older adult fall prevention interventions. J Safety Res. 2015;52:65-70.

5. CDC. WISQARS leading causes of nonfatal injury reports: 2006. Accessed November 13, 2006.

6. CDC. Risk factors for falls. http://www.cdc.gov/steadi/pdf/risk_factors_for_falls-a.pdf. Accessed November 4, 2015.

7. Hausdorff JM, Rios DA, Edelberg HK. Gait variability and fall risk in community-living older adults: a 1-year prospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(8):1050-1056.

8. Ambrose AF, Paul G, Hausdorff JM. Risk factors for falls among older adults: a review of the literature. Maturitas. 2013;75(1):51-61.

9. CDC. Compendium of Effective Fall Interventions: What Works for Community-Dwelling Older Adults. 3rd ed. www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/Falls/compendium.html. Accessed November 4, 2015.

10. Hafner K. Bracing for the falls of an aging nation. New York Times. November 2, 2014. www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/11/03/health/bracing-for-the-falls-of-an-aging-nation.html?emc=edit_na_20141102&_r=0. Accessed November 4, 2015.

11. Houry D. The White House Conference on Aging and keeping older adults STEADI and free from falls. www.whitehouseconferenceonaging.gov/blog/post/the-white-house-conference-on-aging-and-keeping-older-adults-steadi-and-free-from-falls1.aspx. Accessed November 4, 2015.

12. Scott K. ATSU receives $95,000 grant to expand Fall Prevention Outreach program [news release]. October 1, 2015. http://news.atsu.edu/index.php/archives/category/arizona-campus. Accessed November 4, 2015.

13. MaineHealth Partnership for Healthy Aging. A Matter of Balance: Managing Concerns About Falls. www.mainehealth.org/AMatterofBalanceFrequentlyAskedQuestions#mob. Accessed November 4, 2015.

14. CDC. Preventing Falls: A Guide to Implementing Effective Community-Based Fall Prevention Programs. www.cdc.gov/HomeandRecreationalSafetyFalls/community_preventfalls.html. Accessed November 4, 2015.

Last week, I fell in the driveway. I was taking the trash to the curb when I tripped and fell into the large blue recycling bin. Although it was 6 AM, I jumped up and looked around, horrified that someone may have seen my episode of gracelessness. I did bump my head and spent the rest of the day feeling stupid while rubbing the sore spot.

This incident, though more ego-bruising than anything, really conveyed to me the concerns of falling—not only for the elderly, but for all of us. So, not to be confused with the signature song from the musical Wicked sung by Elphaba (the Wicked Witch of the West) who has a desire to live without limits, my editorial this month discusses sobering limits in our everyday lives. And it does implicate gravity!

According to the National Council on Aging, about 1 in 3 adults ages 65 and older fall each year.1 Unintentional falls are the leading cause of nonfatal and fatal injuries (eg, hip fractures, head trauma) for older adults and result in about 57 fall-related deaths per 100,000 people per year.1,2 In 2013, more than 25,000 elderly individuals in the United States died from unintentional fall injuries.3

Who falls? Who doesn’t? But data indicate that among community-dwelling individuals older than 65, women fall more frequently than their male counterparts.4 But while injury and mortality rates rise dramatically for both sexes, regardless of race, after age 85, men in this age-group are more likely to die from a fall than are women.5

There are many risk factors that contribute to falling (see the table6), with gait and balance problems reported as the most significant contributor to falls among older adults.7 In addition, researchers report an increase in diseases linked to falls: diabetes, heart disease, stroke, arthritis, and Parkinson disease. In many cases, the medication used to treat the disease increases the risk for falling.8 It behooves every clinician to assess for and address any modifiable risk factors at each patient visit; one valuable resource is the CDC’s Compendium of Effective Fall Interventions: What Works for Community-Dwelling Older Adults.9

The issue of falling must be addressed on a larger scale, though. In response to the sobering statistics about falls, retirement communities, assisted living facilities, and nursing homes are trying to balance safety with their residents’ desire to live as they choose. They are hiring architects, interior designers, and engineers to find better ways to create safe living spaces, including installing floor lighting (similar to that on airplanes) that automatically illuminates a pathway to the bathroom when a resident gets out of bed.10

Continue for fall prevention in the community >>

But what about fall prevention in the community? A cost-benefit analysis revealed that community-based fall interventions are feasible and effective and provide a positive return on investment—no small consideration, given our current circumstances: Every 13 seconds, an older adult is treated in the emergency department for a fall, and every 29 minutes, an older adult dies from a fall-related injury.4,5 These estimates will likely rise as the population ages. The financial repercussions of falls and resultant morbidity and mortality may exceed $59 billion by 2020, according to the National Council on Aging.1 However, a 2013 report to Congress by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services indicated that older adults’ participation in a falls prevention program has resulted in reduced health care costs.11

Over the decades, many different approaches have been used to enhance older adults’ participation in such programs. I am proud to report that my university is among the many organizations to address this issue. A.T. Still University of Health Sciences (ATSU) was recently awarded a $95,000 grant by the Baptist Hospitals and Health Systems (BHHS) to support the university’s Fall Prevention Outreach program—the largest university-based fall-prevention initiative in the country.12

Since the program began in 2008, more than 2,000 Arizonans have completed the eight-week curriculum, which gives older adults the tools they need to prevent falls and manage the often-paralyzing fear of falling that comes with growing older. Since injuries sustained from falls are the leading cause of accidental injury deaths in Arizonans ages 65 and older, according to the state’s Department of Health Services, this program gives us an opportunity to have a direct impact on our community.

ATSU uses A Matter of Balance, a nationally recognized fall-prevention curriculum developed by Boston University.13 After receiving special training, teams of ATSU physician assistant, physical therapy, occupational therapy, athletic training, and audiology students offer the curriculum, at no cost, to older citizens at 41 community sites in the Greater Phoenix area. Collaborations with partners ranging from local municipalities to assisted-living communities make the program possible.

Part of the BHHS grant funded the certification of 15 master trainers who teach the two-day A Matter of Balance curriculum to the ATSU students and the community volunteers who will, in turn, lead the sessions. The grant also funded the expansion of the program to an additional 24 sites, for a total of 65.12

For those who wish to identify appropriate evidence-based fall prevention programs in their community, the CDC developed a new guide, Preventing Falls: A Guide to Implementing Effective Community-Based Fall Prevention Programs.14 This “how-to” outlines how community-based organizations initiate and maintain effective programs. It focuses on implementation of fall prevention programs and offers strategies on program planning, development, implementation, and evaluation. This resource provides a solid starting point for those seeking to address this increasingly prevalent issue.

How do you investigate the risk for falls with your patients? I would be interested in hearing from you what resources are available in your community. You can contact me at PAEditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

REFERENCES

1. Cameron K, Schneider E, Childress D, Gilchrist C. (2015). National Council on Aging Falls Free® National Action Plan (2015). www.ncoa.org/FallsFreeNAP. Accessed November 5, 2015.

2. CDC. Important Facts about Falls. www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/falls/adultfalls.html. Accessed November 5, 2015.

3. CDC National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Injury Prevention & Control: Data & Statistics (WISQARSTM). www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/. Accessed August 15, 2013.

4. Carande-Kulis I, Stevens JA, Florence CS, et al. Special Report from the CDC: a cost-benefit analysis of three older adult fall prevention interventions. J Safety Res. 2015;52:65-70.

5. CDC. WISQARS leading causes of nonfatal injury reports: 2006. Accessed November 13, 2006.

6. CDC. Risk factors for falls. http://www.cdc.gov/steadi/pdf/risk_factors_for_falls-a.pdf. Accessed November 4, 2015.

7. Hausdorff JM, Rios DA, Edelberg HK. Gait variability and fall risk in community-living older adults: a 1-year prospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(8):1050-1056.

8. Ambrose AF, Paul G, Hausdorff JM. Risk factors for falls among older adults: a review of the literature. Maturitas. 2013;75(1):51-61.

9. CDC. Compendium of Effective Fall Interventions: What Works for Community-Dwelling Older Adults. 3rd ed. www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/Falls/compendium.html. Accessed November 4, 2015.

10. Hafner K. Bracing for the falls of an aging nation. New York Times. November 2, 2014. www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/11/03/health/bracing-for-the-falls-of-an-aging-nation.html?emc=edit_na_20141102&_r=0. Accessed November 4, 2015.

11. Houry D. The White House Conference on Aging and keeping older adults STEADI and free from falls. www.whitehouseconferenceonaging.gov/blog/post/the-white-house-conference-on-aging-and-keeping-older-adults-steadi-and-free-from-falls1.aspx. Accessed November 4, 2015.

12. Scott K. ATSU receives $95,000 grant to expand Fall Prevention Outreach program [news release]. October 1, 2015. http://news.atsu.edu/index.php/archives/category/arizona-campus. Accessed November 4, 2015.

13. MaineHealth Partnership for Healthy Aging. A Matter of Balance: Managing Concerns About Falls. www.mainehealth.org/AMatterofBalanceFrequentlyAskedQuestions#mob. Accessed November 4, 2015.

14. CDC. Preventing Falls: A Guide to Implementing Effective Community-Based Fall Prevention Programs. www.cdc.gov/HomeandRecreationalSafetyFalls/community_preventfalls.html. Accessed November 4, 2015.

Last week, I fell in the driveway. I was taking the trash to the curb when I tripped and fell into the large blue recycling bin. Although it was 6 AM, I jumped up and looked around, horrified that someone may have seen my episode of gracelessness. I did bump my head and spent the rest of the day feeling stupid while rubbing the sore spot.

This incident, though more ego-bruising than anything, really conveyed to me the concerns of falling—not only for the elderly, but for all of us. So, not to be confused with the signature song from the musical Wicked sung by Elphaba (the Wicked Witch of the West) who has a desire to live without limits, my editorial this month discusses sobering limits in our everyday lives. And it does implicate gravity!

According to the National Council on Aging, about 1 in 3 adults ages 65 and older fall each year.1 Unintentional falls are the leading cause of nonfatal and fatal injuries (eg, hip fractures, head trauma) for older adults and result in about 57 fall-related deaths per 100,000 people per year.1,2 In 2013, more than 25,000 elderly individuals in the United States died from unintentional fall injuries.3

Who falls? Who doesn’t? But data indicate that among community-dwelling individuals older than 65, women fall more frequently than their male counterparts.4 But while injury and mortality rates rise dramatically for both sexes, regardless of race, after age 85, men in this age-group are more likely to die from a fall than are women.5

There are many risk factors that contribute to falling (see the table6), with gait and balance problems reported as the most significant contributor to falls among older adults.7 In addition, researchers report an increase in diseases linked to falls: diabetes, heart disease, stroke, arthritis, and Parkinson disease. In many cases, the medication used to treat the disease increases the risk for falling.8 It behooves every clinician to assess for and address any modifiable risk factors at each patient visit; one valuable resource is the CDC’s Compendium of Effective Fall Interventions: What Works for Community-Dwelling Older Adults.9

The issue of falling must be addressed on a larger scale, though. In response to the sobering statistics about falls, retirement communities, assisted living facilities, and nursing homes are trying to balance safety with their residents’ desire to live as they choose. They are hiring architects, interior designers, and engineers to find better ways to create safe living spaces, including installing floor lighting (similar to that on airplanes) that automatically illuminates a pathway to the bathroom when a resident gets out of bed.10

Continue for fall prevention in the community >>

But what about fall prevention in the community? A cost-benefit analysis revealed that community-based fall interventions are feasible and effective and provide a positive return on investment—no small consideration, given our current circumstances: Every 13 seconds, an older adult is treated in the emergency department for a fall, and every 29 minutes, an older adult dies from a fall-related injury.4,5 These estimates will likely rise as the population ages. The financial repercussions of falls and resultant morbidity and mortality may exceed $59 billion by 2020, according to the National Council on Aging.1 However, a 2013 report to Congress by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services indicated that older adults’ participation in a falls prevention program has resulted in reduced health care costs.11

Over the decades, many different approaches have been used to enhance older adults’ participation in such programs. I am proud to report that my university is among the many organizations to address this issue. A.T. Still University of Health Sciences (ATSU) was recently awarded a $95,000 grant by the Baptist Hospitals and Health Systems (BHHS) to support the university’s Fall Prevention Outreach program—the largest university-based fall-prevention initiative in the country.12

Since the program began in 2008, more than 2,000 Arizonans have completed the eight-week curriculum, which gives older adults the tools they need to prevent falls and manage the often-paralyzing fear of falling that comes with growing older. Since injuries sustained from falls are the leading cause of accidental injury deaths in Arizonans ages 65 and older, according to the state’s Department of Health Services, this program gives us an opportunity to have a direct impact on our community.

ATSU uses A Matter of Balance, a nationally recognized fall-prevention curriculum developed by Boston University.13 After receiving special training, teams of ATSU physician assistant, physical therapy, occupational therapy, athletic training, and audiology students offer the curriculum, at no cost, to older citizens at 41 community sites in the Greater Phoenix area. Collaborations with partners ranging from local municipalities to assisted-living communities make the program possible.

Part of the BHHS grant funded the certification of 15 master trainers who teach the two-day A Matter of Balance curriculum to the ATSU students and the community volunteers who will, in turn, lead the sessions. The grant also funded the expansion of the program to an additional 24 sites, for a total of 65.12

For those who wish to identify appropriate evidence-based fall prevention programs in their community, the CDC developed a new guide, Preventing Falls: A Guide to Implementing Effective Community-Based Fall Prevention Programs.14 This “how-to” outlines how community-based organizations initiate and maintain effective programs. It focuses on implementation of fall prevention programs and offers strategies on program planning, development, implementation, and evaluation. This resource provides a solid starting point for those seeking to address this increasingly prevalent issue.

How do you investigate the risk for falls with your patients? I would be interested in hearing from you what resources are available in your community. You can contact me at PAEditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

REFERENCES

1. Cameron K, Schneider E, Childress D, Gilchrist C. (2015). National Council on Aging Falls Free® National Action Plan (2015). www.ncoa.org/FallsFreeNAP. Accessed November 5, 2015.

2. CDC. Important Facts about Falls. www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/falls/adultfalls.html. Accessed November 5, 2015.

3. CDC National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Injury Prevention & Control: Data & Statistics (WISQARSTM). www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/. Accessed August 15, 2013.

4. Carande-Kulis I, Stevens JA, Florence CS, et al. Special Report from the CDC: a cost-benefit analysis of three older adult fall prevention interventions. J Safety Res. 2015;52:65-70.

5. CDC. WISQARS leading causes of nonfatal injury reports: 2006. Accessed November 13, 2006.

6. CDC. Risk factors for falls. http://www.cdc.gov/steadi/pdf/risk_factors_for_falls-a.pdf. Accessed November 4, 2015.

7. Hausdorff JM, Rios DA, Edelberg HK. Gait variability and fall risk in community-living older adults: a 1-year prospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(8):1050-1056.

8. Ambrose AF, Paul G, Hausdorff JM. Risk factors for falls among older adults: a review of the literature. Maturitas. 2013;75(1):51-61.

9. CDC. Compendium of Effective Fall Interventions: What Works for Community-Dwelling Older Adults. 3rd ed. www.cdc.gov/homeandrecreationalsafety/Falls/compendium.html. Accessed November 4, 2015.

10. Hafner K. Bracing for the falls of an aging nation. New York Times. November 2, 2014. www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/11/03/health/bracing-for-the-falls-of-an-aging-nation.html?emc=edit_na_20141102&_r=0. Accessed November 4, 2015.

11. Houry D. The White House Conference on Aging and keeping older adults STEADI and free from falls. www.whitehouseconferenceonaging.gov/blog/post/the-white-house-conference-on-aging-and-keeping-older-adults-steadi-and-free-from-falls1.aspx. Accessed November 4, 2015.

12. Scott K. ATSU receives $95,000 grant to expand Fall Prevention Outreach program [news release]. October 1, 2015. http://news.atsu.edu/index.php/archives/category/arizona-campus. Accessed November 4, 2015.

13. MaineHealth Partnership for Healthy Aging. A Matter of Balance: Managing Concerns About Falls. www.mainehealth.org/AMatterofBalanceFrequentlyAskedQuestions#mob. Accessed November 4, 2015.

14. CDC. Preventing Falls: A Guide to Implementing Effective Community-Based Fall Prevention Programs. www.cdc.gov/HomeandRecreationalSafetyFalls/community_preventfalls.html. Accessed November 4, 2015.

To Thine Own Health Be True

After 40 years as a PA (including 21 in academia), tucking myself safely into my seventh decade of life, I was feeling fairly invincible. Yes, I was experiencing increased fatigue and intermittent dizziness, but I attributed those to normal aging and my hectic schedule. Purely to get my colleagues and loved ones off my back, I agreed to see my primary care physician—but, feeling that I had little time for this and knowing that my health was just fine, thank you, I scheduled my appointment for a month later.

That appointment resulted in a referral to a cardiologist (which I didn’t think I needed) and a carotid ultrasound (which yielded negative results). I was still begrudging the time spent on these appointments, when my treadmill test revealed some ST changes in the lateral leads. OK, yes, I do have a positive family history for heart disease! But still, I was surprised.

This finding led to a nuclear treadmill test, which showed some ischemia. The cardiologist suggested an angiogram to rule out a probable false-positive result. Now, I really didn’t have time for this, either—but having gone this far, I felt it was important just to get it over with. Thank goodness I did!

During my angiogram (by the way, they give you great LaLa Land drugs), the interventional cardiologist discovered a 95% blockage of the circumflex, a 95% blockage of the right coronary artery, and a 60% blockage of the LAD. The big decision at that point, amidst the obvious shock of my mortality, was whether to opt for an open-heart bypass or stents. I chose stents (which, by the way, have had a significant impact on my energy level). My cardiologist tells me that, without the stents, if I had experienced a total occlusion event, I would not have survived. Quite a sobering thought!

My purpose in sharing this story is not to call attention to myself but rather to offer a wake-up call to those of us who think we are invincible. Many colleagues who have heard my story have decided to get their own long-delayed treadmill or other health-related tests. So here is my call to action to all of you: Take care of your health. The irony is that, for health care providers, this can be difficult.

Those who care for others often have a tough time caring for themselves. We know that physicians are notoriously bad patients, and I think PAs/NPs are no different. We deal with life-and-death issues all the time, and outward displays of distress are, at a minimum, discouraged. In general, our training and accumulated experience help us to develop good coping skills: We are taught to ignore basic human needs (like hunger and fatigue) and to remain capable, competent, and compassionate clinicians under highly stressful conditions.

Nonetheless, we experience these high levels of stress and seldom act to relieve them. As long ago as 1886, Dr William Ogle exposed clinicians’ vulnerability to high mortality risks, but to this day, the subject remains fairly neglected.1 Perhaps as a result of stigma—we worry about confidentiality, or that our colleagues will consider us inadequate or incompetent clinicians, or that a display of “weakness” means we have failed in some way—we often wait too long to seek treatment. Often, it takes a crisis before we stop to care for ourselves.

Continue for suggestions on how to take care of yourself >>

We promote the health of our patients, but we often forget that if health is to be sustained, those who provide the help must be capable of caring for both themselves and others.2 Without being overly prescriptive, I would like to share with you some suggestions for how you can take care of yourself:

1. Maintain a positive attitude. Yes, we often set ourselves up for failure, but we must have patience with ourselves. There are countless ways to practice reflection and find some time to think; it could entail an artistic outlet such as painting, sculpting, sewing, or singing. A colleague of mine listens to affirmations (now available by smartphone app) that she says help her succeed in her daily endeavors.

2. Identify your support systems. You know who they are: family, friends, and colleagues who bring positive support to your life. Spend more time with them. Clinicians with strong family or social connections are generally healthier than those who lack a support network. Make plans with supportive family members and friends, or seek out activities where you can meet new people.

3. Choose healthy, well-balanced meals. This is probably one of the most difficult tasks, due to our hectic and busy lifestyles. We should strive for low-fat, low-sugar, low-salt, high-fiber, and reasonably low-calorie meals. And drink more water—at least 6 to 8 glasses per day.

4. Get an appropriate amount of sleep. Restorative rest is one of the things you can control and should—no, must—give priority to. It is known that sleep is key to competent delivery of care. The National Sleep Foundation suggests seven to nine hours per night for those ages 26 to 64 and seven to eight hours per night for those older than 65.3 (In fact, some studies have suggested an increase in stroke linked to sleeping longer in older age.4)

5. Exercise. Schedule time for a sustainable exercise program. Put it on your calendar, and make that the one meeting that is essential. (This is another area in which technology can help, by providing reminders that you need to get up and move.) You don’t have to go to the gym twice a day or run a marathon. Walking for an hour three or four times a week will make a difference; even a 5-minute walk after a stressful meeting can help. Just do it!

6. Schedule time for R&R. Over the past decade, a staggering number of studies have demonstrated that our work performance plummets when we work prolonged periods without a break. Use your vacation time! A recent Harvard Business Review article reported that employees who take vacation are actually more productive.5 Make time for yourself—no one else will!

7. Take care of your mental health. Stress is a fact of life. Do what you can to relieve it; develop good coping skills and use them. You may find that keeping a journal in which you can vent your frustrations and fears or taking your dog for a long walk helps to relieve tension. Find what works for you. And make sure to laugh and find the humor in life. Laughter has been shown to boost the immune system and ease pain. It’s a great way to relax!

8. Take care of your physical health. Caring for your body is one of the best things you can do for yourself. Reduce or eliminate risk factors. Please get your routine health promotion procedures done (eg, colonoscopy, Pap smear, mammogram). And when you experience signs of illness, don’t ignore them! Seek advice early for anything out of the ordinary, be it intermittent dizziness, recurrent fatigue, unintended weight loss, feelings of despair—I could go on.

If even a handful of you heed these suggestions, and doing so makes a difference in your health and longevity, then I have completed my mission for this editorial.

We should be role models for our patients. The societal focus on healthy lifestyles is a challenge for all of us, but the benefits are enormous. I would love to hear from you regarding ways to enhance our physical and mental health and avoid early morbidity or mortality. You can reach me at PAEditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

REFERENCES

1. Woods R. Physician, heal thyself: the health and mortality of Victorian doctors. Soc Hist Med. 1966;9(1):1-30.

2. Borchardt GL. Role models for health promotion: the challenge for nurses. Nurs Forum. 2000;35(3):29-32.

3. Hershkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, et al. National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health. 2015;1(1):40-43.

4. Leng Y, Cappuccio FP, Wainwright NWJ, et al. Sleep duration and risk of fatal and nonfatal stroke: a prospective study and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2015;84(11):1072-1079.

5. Friedman R. Dear boss: your team wants you to go on vacation. Harvard Bus Rev. June 15, 2015.

After 40 years as a PA (including 21 in academia), tucking myself safely into my seventh decade of life, I was feeling fairly invincible. Yes, I was experiencing increased fatigue and intermittent dizziness, but I attributed those to normal aging and my hectic schedule. Purely to get my colleagues and loved ones off my back, I agreed to see my primary care physician—but, feeling that I had little time for this and knowing that my health was just fine, thank you, I scheduled my appointment for a month later.

That appointment resulted in a referral to a cardiologist (which I didn’t think I needed) and a carotid ultrasound (which yielded negative results). I was still begrudging the time spent on these appointments, when my treadmill test revealed some ST changes in the lateral leads. OK, yes, I do have a positive family history for heart disease! But still, I was surprised.

This finding led to a nuclear treadmill test, which showed some ischemia. The cardiologist suggested an angiogram to rule out a probable false-positive result. Now, I really didn’t have time for this, either—but having gone this far, I felt it was important just to get it over with. Thank goodness I did!

During my angiogram (by the way, they give you great LaLa Land drugs), the interventional cardiologist discovered a 95% blockage of the circumflex, a 95% blockage of the right coronary artery, and a 60% blockage of the LAD. The big decision at that point, amidst the obvious shock of my mortality, was whether to opt for an open-heart bypass or stents. I chose stents (which, by the way, have had a significant impact on my energy level). My cardiologist tells me that, without the stents, if I had experienced a total occlusion event, I would not have survived. Quite a sobering thought!

My purpose in sharing this story is not to call attention to myself but rather to offer a wake-up call to those of us who think we are invincible. Many colleagues who have heard my story have decided to get their own long-delayed treadmill or other health-related tests. So here is my call to action to all of you: Take care of your health. The irony is that, for health care providers, this can be difficult.

Those who care for others often have a tough time caring for themselves. We know that physicians are notoriously bad patients, and I think PAs/NPs are no different. We deal with life-and-death issues all the time, and outward displays of distress are, at a minimum, discouraged. In general, our training and accumulated experience help us to develop good coping skills: We are taught to ignore basic human needs (like hunger and fatigue) and to remain capable, competent, and compassionate clinicians under highly stressful conditions.

Nonetheless, we experience these high levels of stress and seldom act to relieve them. As long ago as 1886, Dr William Ogle exposed clinicians’ vulnerability to high mortality risks, but to this day, the subject remains fairly neglected.1 Perhaps as a result of stigma—we worry about confidentiality, or that our colleagues will consider us inadequate or incompetent clinicians, or that a display of “weakness” means we have failed in some way—we often wait too long to seek treatment. Often, it takes a crisis before we stop to care for ourselves.

Continue for suggestions on how to take care of yourself >>

We promote the health of our patients, but we often forget that if health is to be sustained, those who provide the help must be capable of caring for both themselves and others.2 Without being overly prescriptive, I would like to share with you some suggestions for how you can take care of yourself:

1. Maintain a positive attitude. Yes, we often set ourselves up for failure, but we must have patience with ourselves. There are countless ways to practice reflection and find some time to think; it could entail an artistic outlet such as painting, sculpting, sewing, or singing. A colleague of mine listens to affirmations (now available by smartphone app) that she says help her succeed in her daily endeavors.

2. Identify your support systems. You know who they are: family, friends, and colleagues who bring positive support to your life. Spend more time with them. Clinicians with strong family or social connections are generally healthier than those who lack a support network. Make plans with supportive family members and friends, or seek out activities where you can meet new people.

3. Choose healthy, well-balanced meals. This is probably one of the most difficult tasks, due to our hectic and busy lifestyles. We should strive for low-fat, low-sugar, low-salt, high-fiber, and reasonably low-calorie meals. And drink more water—at least 6 to 8 glasses per day.

4. Get an appropriate amount of sleep. Restorative rest is one of the things you can control and should—no, must—give priority to. It is known that sleep is key to competent delivery of care. The National Sleep Foundation suggests seven to nine hours per night for those ages 26 to 64 and seven to eight hours per night for those older than 65.3 (In fact, some studies have suggested an increase in stroke linked to sleeping longer in older age.4)

5. Exercise. Schedule time for a sustainable exercise program. Put it on your calendar, and make that the one meeting that is essential. (This is another area in which technology can help, by providing reminders that you need to get up and move.) You don’t have to go to the gym twice a day or run a marathon. Walking for an hour three or four times a week will make a difference; even a 5-minute walk after a stressful meeting can help. Just do it!

6. Schedule time for R&R. Over the past decade, a staggering number of studies have demonstrated that our work performance plummets when we work prolonged periods without a break. Use your vacation time! A recent Harvard Business Review article reported that employees who take vacation are actually more productive.5 Make time for yourself—no one else will!

7. Take care of your mental health. Stress is a fact of life. Do what you can to relieve it; develop good coping skills and use them. You may find that keeping a journal in which you can vent your frustrations and fears or taking your dog for a long walk helps to relieve tension. Find what works for you. And make sure to laugh and find the humor in life. Laughter has been shown to boost the immune system and ease pain. It’s a great way to relax!

8. Take care of your physical health. Caring for your body is one of the best things you can do for yourself. Reduce or eliminate risk factors. Please get your routine health promotion procedures done (eg, colonoscopy, Pap smear, mammogram). And when you experience signs of illness, don’t ignore them! Seek advice early for anything out of the ordinary, be it intermittent dizziness, recurrent fatigue, unintended weight loss, feelings of despair—I could go on.

If even a handful of you heed these suggestions, and doing so makes a difference in your health and longevity, then I have completed my mission for this editorial.

We should be role models for our patients. The societal focus on healthy lifestyles is a challenge for all of us, but the benefits are enormous. I would love to hear from you regarding ways to enhance our physical and mental health and avoid early morbidity or mortality. You can reach me at PAEditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

REFERENCES

1. Woods R. Physician, heal thyself: the health and mortality of Victorian doctors. Soc Hist Med. 1966;9(1):1-30.

2. Borchardt GL. Role models for health promotion: the challenge for nurses. Nurs Forum. 2000;35(3):29-32.

3. Hershkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, et al. National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health. 2015;1(1):40-43.

4. Leng Y, Cappuccio FP, Wainwright NWJ, et al. Sleep duration and risk of fatal and nonfatal stroke: a prospective study and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2015;84(11):1072-1079.

5. Friedman R. Dear boss: your team wants you to go on vacation. Harvard Bus Rev. June 15, 2015.

After 40 years as a PA (including 21 in academia), tucking myself safely into my seventh decade of life, I was feeling fairly invincible. Yes, I was experiencing increased fatigue and intermittent dizziness, but I attributed those to normal aging and my hectic schedule. Purely to get my colleagues and loved ones off my back, I agreed to see my primary care physician—but, feeling that I had little time for this and knowing that my health was just fine, thank you, I scheduled my appointment for a month later.

That appointment resulted in a referral to a cardiologist (which I didn’t think I needed) and a carotid ultrasound (which yielded negative results). I was still begrudging the time spent on these appointments, when my treadmill test revealed some ST changes in the lateral leads. OK, yes, I do have a positive family history for heart disease! But still, I was surprised.

This finding led to a nuclear treadmill test, which showed some ischemia. The cardiologist suggested an angiogram to rule out a probable false-positive result. Now, I really didn’t have time for this, either—but having gone this far, I felt it was important just to get it over with. Thank goodness I did!

During my angiogram (by the way, they give you great LaLa Land drugs), the interventional cardiologist discovered a 95% blockage of the circumflex, a 95% blockage of the right coronary artery, and a 60% blockage of the LAD. The big decision at that point, amidst the obvious shock of my mortality, was whether to opt for an open-heart bypass or stents. I chose stents (which, by the way, have had a significant impact on my energy level). My cardiologist tells me that, without the stents, if I had experienced a total occlusion event, I would not have survived. Quite a sobering thought!

My purpose in sharing this story is not to call attention to myself but rather to offer a wake-up call to those of us who think we are invincible. Many colleagues who have heard my story have decided to get their own long-delayed treadmill or other health-related tests. So here is my call to action to all of you: Take care of your health. The irony is that, for health care providers, this can be difficult.

Those who care for others often have a tough time caring for themselves. We know that physicians are notoriously bad patients, and I think PAs/NPs are no different. We deal with life-and-death issues all the time, and outward displays of distress are, at a minimum, discouraged. In general, our training and accumulated experience help us to develop good coping skills: We are taught to ignore basic human needs (like hunger and fatigue) and to remain capable, competent, and compassionate clinicians under highly stressful conditions.

Nonetheless, we experience these high levels of stress and seldom act to relieve them. As long ago as 1886, Dr William Ogle exposed clinicians’ vulnerability to high mortality risks, but to this day, the subject remains fairly neglected.1 Perhaps as a result of stigma—we worry about confidentiality, or that our colleagues will consider us inadequate or incompetent clinicians, or that a display of “weakness” means we have failed in some way—we often wait too long to seek treatment. Often, it takes a crisis before we stop to care for ourselves.

Continue for suggestions on how to take care of yourself >>

We promote the health of our patients, but we often forget that if health is to be sustained, those who provide the help must be capable of caring for both themselves and others.2 Without being overly prescriptive, I would like to share with you some suggestions for how you can take care of yourself:

1. Maintain a positive attitude. Yes, we often set ourselves up for failure, but we must have patience with ourselves. There are countless ways to practice reflection and find some time to think; it could entail an artistic outlet such as painting, sculpting, sewing, or singing. A colleague of mine listens to affirmations (now available by smartphone app) that she says help her succeed in her daily endeavors.

2. Identify your support systems. You know who they are: family, friends, and colleagues who bring positive support to your life. Spend more time with them. Clinicians with strong family or social connections are generally healthier than those who lack a support network. Make plans with supportive family members and friends, or seek out activities where you can meet new people.

3. Choose healthy, well-balanced meals. This is probably one of the most difficult tasks, due to our hectic and busy lifestyles. We should strive for low-fat, low-sugar, low-salt, high-fiber, and reasonably low-calorie meals. And drink more water—at least 6 to 8 glasses per day.

4. Get an appropriate amount of sleep. Restorative rest is one of the things you can control and should—no, must—give priority to. It is known that sleep is key to competent delivery of care. The National Sleep Foundation suggests seven to nine hours per night for those ages 26 to 64 and seven to eight hours per night for those older than 65.3 (In fact, some studies have suggested an increase in stroke linked to sleeping longer in older age.4)

5. Exercise. Schedule time for a sustainable exercise program. Put it on your calendar, and make that the one meeting that is essential. (This is another area in which technology can help, by providing reminders that you need to get up and move.) You don’t have to go to the gym twice a day or run a marathon. Walking for an hour three or four times a week will make a difference; even a 5-minute walk after a stressful meeting can help. Just do it!

6. Schedule time for R&R. Over the past decade, a staggering number of studies have demonstrated that our work performance plummets when we work prolonged periods without a break. Use your vacation time! A recent Harvard Business Review article reported that employees who take vacation are actually more productive.5 Make time for yourself—no one else will!

7. Take care of your mental health. Stress is a fact of life. Do what you can to relieve it; develop good coping skills and use them. You may find that keeping a journal in which you can vent your frustrations and fears or taking your dog for a long walk helps to relieve tension. Find what works for you. And make sure to laugh and find the humor in life. Laughter has been shown to boost the immune system and ease pain. It’s a great way to relax!

8. Take care of your physical health. Caring for your body is one of the best things you can do for yourself. Reduce or eliminate risk factors. Please get your routine health promotion procedures done (eg, colonoscopy, Pap smear, mammogram). And when you experience signs of illness, don’t ignore them! Seek advice early for anything out of the ordinary, be it intermittent dizziness, recurrent fatigue, unintended weight loss, feelings of despair—I could go on.

If even a handful of you heed these suggestions, and doing so makes a difference in your health and longevity, then I have completed my mission for this editorial.

We should be role models for our patients. The societal focus on healthy lifestyles is a challenge for all of us, but the benefits are enormous. I would love to hear from you regarding ways to enhance our physical and mental health and avoid early morbidity or mortality. You can reach me at PAEditor@frontlinemedcom.com.

REFERENCES

1. Woods R. Physician, heal thyself: the health and mortality of Victorian doctors. Soc Hist Med. 1966;9(1):1-30.

2. Borchardt GL. Role models for health promotion: the challenge for nurses. Nurs Forum. 2000;35(3):29-32.

3. Hershkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, et al. National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health. 2015;1(1):40-43.

4. Leng Y, Cappuccio FP, Wainwright NWJ, et al. Sleep duration and risk of fatal and nonfatal stroke: a prospective study and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2015;84(11):1072-1079.

5. Friedman R. Dear boss: your team wants you to go on vacation. Harvard Bus Rev. June 15, 2015.

Going for the Gold

As we enter 2015 and approach the golden (50th) anniversary of both the NP and PA professions, dating back to Dr. Loretta Ford1 at the University of Colorado and Dr. Eugene Stead2 at Duke University (circa 1965), it is important to reflect on not only where we have been but also where we want our professions to go in the next half-century.

Since I am a PA, some may suggest that it is dangerous and ambitious for me to speak/project for both professions. They may also note that the professions are distinct and my suggestions and reflections do not apply to NPs. Well, I guess I am willing to take that risk. As a colleague, friend, and co-Editor-in-Chief of Marie-Eileen Onieal, I have found that we agree much more often on issues (both political and practical) than we disagree.

NPs and PAs have worked diligently over the past half-century to develop our individual professions, in terms of reimbursement, prescribing privileges, state licensure, commissioning in the uniformed services, and expansion of scope of practice. Studies continue to show that we provide quality health care with similar outcomes as physicians, thus making us cost-effective members of the health care team.3-7

So, here we are in 2015. While it is difficult to get accurate data, Table 1 shows the number of clinicians reported in the most recent US Health Workforce Chartbook.8 As we well know, our professions have grown exponentially from our humble beginnings in the mid-1960s. (The first class of PAs comprised four students, if you recall.)

At the risk of sounding like a fossil (Oh never mind—I am a fossil!), let me be presumptuous and share with you six areas in which I think both professions can “do more” through the second half-century of our existence. In my opinion, we should focus on:

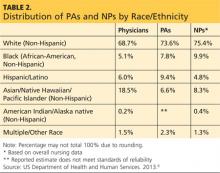

1. Diversity. As presented in Table 2, the majority of PAs and NPs are (non-Hispanic) white. Our efforts, should you agree with me, must start at the educational program level, through recruitment and retention of students from unrepresented and underrepresented groups. Another focal point should be the recruitment and retention of faculty and staff in these programs who reflect the diversity of our nation.

When I consider the origins of my profession, the key point is opportunity. Dr. Stead and other pioneers sought to fill a serious need for health care providers while also creating opportunities for military medics who were highly skilled but who did not meet requirements for many jobs within the medical community. Now it is time for us to ensure that other groups have similar opportunities to advance themselves and also fill gaps in the health care system.

Continue for more areas to focus on >>

2. Workforce planning and policy. This requires better data collection and an improved information infrastructure. In a 2014 editorial, Rod Hooker suggested that this is the golden age for PAs (about whom he was writing, although the same holds true for NPs) because US health care reform has identified our contributions to society and new policies place us upfront and center stage in producing labor solutions.9

It is time for our professions to do a better job in studying and reporting the important contributions we make in health care delivery. We need to have a place at the table—be it within a facility or at the state or federal level—whenever policy, utilization, and roles are discussed. Even if we as employees are subordinate to management in a particular setting, we should have a voice in how we are utilized in the workplace; we should ensure that those who make decisions—if we are not them—have the fullest picture of who we are and what we can do. It is not enough to use anecdotal evidence; we need to have data readily at hand that unequivocally support our assertions of value to patient care.

Hooker went so far as to call for the creation of a “physician assistant institute” to assist in the development and dissemination of reliable information about the profession. I think this is an idea whose time has come, but who will step up to the plate? If you are an NP, you may say, “What about us?” I would suggest this issue pertains to both of our professions—and in fact, this is an area in which I would encourage a collaborative effort. What a concept!

3. Ethics. In the past decade, there has been a renewed focus on maintaining an ethical culture in health care. As clinicians, we practice in an environment that affects the lives of everyone. Our patients and their family members expect high-quality care, patient safety, and use of the latest and most appropriate technology.

In the middle of this climate, we find a health care system that is probably the most entrepreneurial, corporatized, and profit-driven health system in the world. Most of our practice settings (outside the federal government) are for-profit entities. It is easy in this environment to fall victim to conflicts of interest and to acquire an economically oriented practice attitude.

If our first priority is the best possible health care for our patients, then integrity and ethical behavior naturally follow. Professionalism at its very heart places the patient’s interests ahead of our own. We must keep this in mind as we navigate the ever-changing health system.

Next page: Key area number four >>

4. Humanitarianism. I would encourage us to be actively engaged in promoting human welfare and social reforms with no prejudice on grounds of gender, sexual orientation, or religious or ethnic differences. Our goal should be to save lives, relieve suffering, and maintain human dignity.

How do we do this? Many of us have at some point in our careers volunteered our professional services at free clinics or other venues that provide health care to those who otherwise have difficulty accessing it. Some of us take that spirit a step further, traveling abroad on medical missions or responding to natural disasters or civil disturbances.

While using our medical and nursing skills for the good of society is ideal, we can also represent ourselves and our professions well by being good members of the community—not just the “medical” community. Perhaps we provide food and shelter to the homeless in our area or mentor young people.

Anything we do to help not only benefits us and the recipient; it also shows the community that our concept of “care” extends beyond the confines of the clinic or emergency department or operating theater in which we work. We have a very special calling, and I’m always pleased when our professional journals highlight the efforts of our colleagues to “help out”; their stories should inspire us all.

5. Appreciation. As NPs and PAs, we provide health care (whether from a medical or nursing standpoint), a revered calling since the days of Hippocrates. This privilege allows us to enter into a bond with our patients and assist them in a personal and fundamental way. It is no small thing to be involved in curing illness and promoting well-being. We should always remember that our role carries responsibility as well as provides rewards.

Despite the greater availability of diagnostic technologies and advancements in therapeutic abilities, we continue to see increasing disparities in the delivery of health care. Our professions must work diligently to find ways to address the issues of quality, accessibility, and cost of health care in the US. What kind of “stewards” will we be? That is our heritage!

Continue for the last area PAs and NPs need to grow in >>

6. Action. At the risk of sounding like a cheerleader, being part of the NP or PA profession is something special; it always has been and always will be. Our professions have grown impressively in numbers, utilization, and stature. We need to cultivate and support our professions and their representative organizations (ie, AANP and AAPA).

In the early decades of each profession, individuals with a great deal of passion and dedication created, advanced, and led these organizations on both state and national levels—and even an international level. You know who they are! Without them, we would not have made the strides that we have as professionals—the attainment of licensure, authority, and reimbursement.

Now that we are being truly recognized for our role in the health care team and our contributions to patient care, some of us may become complacent with regard to our professional organizations. But there will always be legislative and regulatory gains to make, and strong representation (and “strength in numbers”) is the best way to achieve our professional goals. Please, let’s continue to support our organizations not only via membership (which provides funding for initiatives) but also by participating in whatever ways we can to further our professions.

If we are going to fully cement our place in America’s health care system, NPs and PAs must strive to keep up the national dialogue about our patients, their needs, and how our contributions address those needs. I hope you agree. Please share your thoughts with me at PAEditor@frontline medcom.com.

REFERENCES

1. Ridgway S. Loretta Ford, founded nurse practitioner movement. Working Nurse. www.workingnurse.com/articles/loretta-ford-founded-nurse-practitioner-movement. Accessed January 16, 2015.

2. Physician Assistant History Society. Eugene A. Stead Jr, MD. http://pahx.org/stead-jr-eugene. Accessed January 16, 2015.

3. Kartha A, Restuccia J, Burgess J, et al. Nurse practitioner and physician assistant scope of practice in 118 acute care hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2014:9(10); 615-620.

4. Naylor MD, Kurtzman ET. The role of nurse practitioners in reinventing primary care. Health Affairs. 2010;29(5):893-899.

5. Horrocks S, Anderson E, Salisbury C. Systematic review of whether nurse practitioners working in primary care can provide equivalent care to doctors. BMJ. 2002;324:819-823.

6. Halter M, Drennan V, Chattopadhyay K, et al. The contribution of physician assistants in primary care: a systematic review. BMC Health Services Research. 2013;13:223-236.

7. Hooker RS, Everett CM. The contributions of physician assistants in primary care systems. Health Social Care Commun. 2012;20(1):20-31.

8. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. The US Health Workforce Chartbook. Part 1: Clinicians. Rockville, MD; 2013.

9. Hooker R. A physician assistant institute [editorial]. J Phys Assist Ed. 2014;25(3):5-6.

As we enter 2015 and approach the golden (50th) anniversary of both the NP and PA professions, dating back to Dr. Loretta Ford1 at the University of Colorado and Dr. Eugene Stead2 at Duke University (circa 1965), it is important to reflect on not only where we have been but also where we want our professions to go in the next half-century.

Since I am a PA, some may suggest that it is dangerous and ambitious for me to speak/project for both professions. They may also note that the professions are distinct and my suggestions and reflections do not apply to NPs. Well, I guess I am willing to take that risk. As a colleague, friend, and co-Editor-in-Chief of Marie-Eileen Onieal, I have found that we agree much more often on issues (both political and practical) than we disagree.

NPs and PAs have worked diligently over the past half-century to develop our individual professions, in terms of reimbursement, prescribing privileges, state licensure, commissioning in the uniformed services, and expansion of scope of practice. Studies continue to show that we provide quality health care with similar outcomes as physicians, thus making us cost-effective members of the health care team.3-7

So, here we are in 2015. While it is difficult to get accurate data, Table 1 shows the number of clinicians reported in the most recent US Health Workforce Chartbook.8 As we well know, our professions have grown exponentially from our humble beginnings in the mid-1960s. (The first class of PAs comprised four students, if you recall.)

At the risk of sounding like a fossil (Oh never mind—I am a fossil!), let me be presumptuous and share with you six areas in which I think both professions can “do more” through the second half-century of our existence. In my opinion, we should focus on:

1. Diversity. As presented in Table 2, the majority of PAs and NPs are (non-Hispanic) white. Our efforts, should you agree with me, must start at the educational program level, through recruitment and retention of students from unrepresented and underrepresented groups. Another focal point should be the recruitment and retention of faculty and staff in these programs who reflect the diversity of our nation.

When I consider the origins of my profession, the key point is opportunity. Dr. Stead and other pioneers sought to fill a serious need for health care providers while also creating opportunities for military medics who were highly skilled but who did not meet requirements for many jobs within the medical community. Now it is time for us to ensure that other groups have similar opportunities to advance themselves and also fill gaps in the health care system.

Continue for more areas to focus on >>

2. Workforce planning and policy. This requires better data collection and an improved information infrastructure. In a 2014 editorial, Rod Hooker suggested that this is the golden age for PAs (about whom he was writing, although the same holds true for NPs) because US health care reform has identified our contributions to society and new policies place us upfront and center stage in producing labor solutions.9

It is time for our professions to do a better job in studying and reporting the important contributions we make in health care delivery. We need to have a place at the table—be it within a facility or at the state or federal level—whenever policy, utilization, and roles are discussed. Even if we as employees are subordinate to management in a particular setting, we should have a voice in how we are utilized in the workplace; we should ensure that those who make decisions—if we are not them—have the fullest picture of who we are and what we can do. It is not enough to use anecdotal evidence; we need to have data readily at hand that unequivocally support our assertions of value to patient care.

Hooker went so far as to call for the creation of a “physician assistant institute” to assist in the development and dissemination of reliable information about the profession. I think this is an idea whose time has come, but who will step up to the plate? If you are an NP, you may say, “What about us?” I would suggest this issue pertains to both of our professions—and in fact, this is an area in which I would encourage a collaborative effort. What a concept!

3. Ethics. In the past decade, there has been a renewed focus on maintaining an ethical culture in health care. As clinicians, we practice in an environment that affects the lives of everyone. Our patients and their family members expect high-quality care, patient safety, and use of the latest and most appropriate technology.

In the middle of this climate, we find a health care system that is probably the most entrepreneurial, corporatized, and profit-driven health system in the world. Most of our practice settings (outside the federal government) are for-profit entities. It is easy in this environment to fall victim to conflicts of interest and to acquire an economically oriented practice attitude.

If our first priority is the best possible health care for our patients, then integrity and ethical behavior naturally follow. Professionalism at its very heart places the patient’s interests ahead of our own. We must keep this in mind as we navigate the ever-changing health system.

Next page: Key area number four >>

4. Humanitarianism. I would encourage us to be actively engaged in promoting human welfare and social reforms with no prejudice on grounds of gender, sexual orientation, or religious or ethnic differences. Our goal should be to save lives, relieve suffering, and maintain human dignity.

How do we do this? Many of us have at some point in our careers volunteered our professional services at free clinics or other venues that provide health care to those who otherwise have difficulty accessing it. Some of us take that spirit a step further, traveling abroad on medical missions or responding to natural disasters or civil disturbances.

While using our medical and nursing skills for the good of society is ideal, we can also represent ourselves and our professions well by being good members of the community—not just the “medical” community. Perhaps we provide food and shelter to the homeless in our area or mentor young people.

Anything we do to help not only benefits us and the recipient; it also shows the community that our concept of “care” extends beyond the confines of the clinic or emergency department or operating theater in which we work. We have a very special calling, and I’m always pleased when our professional journals highlight the efforts of our colleagues to “help out”; their stories should inspire us all.

5. Appreciation. As NPs and PAs, we provide health care (whether from a medical or nursing standpoint), a revered calling since the days of Hippocrates. This privilege allows us to enter into a bond with our patients and assist them in a personal and fundamental way. It is no small thing to be involved in curing illness and promoting well-being. We should always remember that our role carries responsibility as well as provides rewards.

Despite the greater availability of diagnostic technologies and advancements in therapeutic abilities, we continue to see increasing disparities in the delivery of health care. Our professions must work diligently to find ways to address the issues of quality, accessibility, and cost of health care in the US. What kind of “stewards” will we be? That is our heritage!

Continue for the last area PAs and NPs need to grow in >>

6. Action. At the risk of sounding like a cheerleader, being part of the NP or PA profession is something special; it always has been and always will be. Our professions have grown impressively in numbers, utilization, and stature. We need to cultivate and support our professions and their representative organizations (ie, AANP and AAPA).

In the early decades of each profession, individuals with a great deal of passion and dedication created, advanced, and led these organizations on both state and national levels—and even an international level. You know who they are! Without them, we would not have made the strides that we have as professionals—the attainment of licensure, authority, and reimbursement.

Now that we are being truly recognized for our role in the health care team and our contributions to patient care, some of us may become complacent with regard to our professional organizations. But there will always be legislative and regulatory gains to make, and strong representation (and “strength in numbers”) is the best way to achieve our professional goals. Please, let’s continue to support our organizations not only via membership (which provides funding for initiatives) but also by participating in whatever ways we can to further our professions.

If we are going to fully cement our place in America’s health care system, NPs and PAs must strive to keep up the national dialogue about our patients, their needs, and how our contributions address those needs. I hope you agree. Please share your thoughts with me at PAEditor@frontline medcom.com.

REFERENCES

1. Ridgway S. Loretta Ford, founded nurse practitioner movement. Working Nurse. www.workingnurse.com/articles/loretta-ford-founded-nurse-practitioner-movement. Accessed January 16, 2015.

2. Physician Assistant History Society. Eugene A. Stead Jr, MD. http://pahx.org/stead-jr-eugene. Accessed January 16, 2015.

3. Kartha A, Restuccia J, Burgess J, et al. Nurse practitioner and physician assistant scope of practice in 118 acute care hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2014:9(10); 615-620.

4. Naylor MD, Kurtzman ET. The role of nurse practitioners in reinventing primary care. Health Affairs. 2010;29(5):893-899.

5. Horrocks S, Anderson E, Salisbury C. Systematic review of whether nurse practitioners working in primary care can provide equivalent care to doctors. BMJ. 2002;324:819-823.

6. Halter M, Drennan V, Chattopadhyay K, et al. The contribution of physician assistants in primary care: a systematic review. BMC Health Services Research. 2013;13:223-236.

7. Hooker RS, Everett CM. The contributions of physician assistants in primary care systems. Health Social Care Commun. 2012;20(1):20-31.

8. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. The US Health Workforce Chartbook. Part 1: Clinicians. Rockville, MD; 2013.

9. Hooker R. A physician assistant institute [editorial]. J Phys Assist Ed. 2014;25(3):5-6.

As we enter 2015 and approach the golden (50th) anniversary of both the NP and PA professions, dating back to Dr. Loretta Ford1 at the University of Colorado and Dr. Eugene Stead2 at Duke University (circa 1965), it is important to reflect on not only where we have been but also where we want our professions to go in the next half-century.

Since I am a PA, some may suggest that it is dangerous and ambitious for me to speak/project for both professions. They may also note that the professions are distinct and my suggestions and reflections do not apply to NPs. Well, I guess I am willing to take that risk. As a colleague, friend, and co-Editor-in-Chief of Marie-Eileen Onieal, I have found that we agree much more often on issues (both political and practical) than we disagree.

NPs and PAs have worked diligently over the past half-century to develop our individual professions, in terms of reimbursement, prescribing privileges, state licensure, commissioning in the uniformed services, and expansion of scope of practice. Studies continue to show that we provide quality health care with similar outcomes as physicians, thus making us cost-effective members of the health care team.3-7

So, here we are in 2015. While it is difficult to get accurate data, Table 1 shows the number of clinicians reported in the most recent US Health Workforce Chartbook.8 As we well know, our professions have grown exponentially from our humble beginnings in the mid-1960s. (The first class of PAs comprised four students, if you recall.)

At the risk of sounding like a fossil (Oh never mind—I am a fossil!), let me be presumptuous and share with you six areas in which I think both professions can “do more” through the second half-century of our existence. In my opinion, we should focus on:

1. Diversity. As presented in Table 2, the majority of PAs and NPs are (non-Hispanic) white. Our efforts, should you agree with me, must start at the educational program level, through recruitment and retention of students from unrepresented and underrepresented groups. Another focal point should be the recruitment and retention of faculty and staff in these programs who reflect the diversity of our nation.

When I consider the origins of my profession, the key point is opportunity. Dr. Stead and other pioneers sought to fill a serious need for health care providers while also creating opportunities for military medics who were highly skilled but who did not meet requirements for many jobs within the medical community. Now it is time for us to ensure that other groups have similar opportunities to advance themselves and also fill gaps in the health care system.

Continue for more areas to focus on >>

2. Workforce planning and policy. This requires better data collection and an improved information infrastructure. In a 2014 editorial, Rod Hooker suggested that this is the golden age for PAs (about whom he was writing, although the same holds true for NPs) because US health care reform has identified our contributions to society and new policies place us upfront and center stage in producing labor solutions.9

It is time for our professions to do a better job in studying and reporting the important contributions we make in health care delivery. We need to have a place at the table—be it within a facility or at the state or federal level—whenever policy, utilization, and roles are discussed. Even if we as employees are subordinate to management in a particular setting, we should have a voice in how we are utilized in the workplace; we should ensure that those who make decisions—if we are not them—have the fullest picture of who we are and what we can do. It is not enough to use anecdotal evidence; we need to have data readily at hand that unequivocally support our assertions of value to patient care.

Hooker went so far as to call for the creation of a “physician assistant institute” to assist in the development and dissemination of reliable information about the profession. I think this is an idea whose time has come, but who will step up to the plate? If you are an NP, you may say, “What about us?” I would suggest this issue pertains to both of our professions—and in fact, this is an area in which I would encourage a collaborative effort. What a concept!

3. Ethics. In the past decade, there has been a renewed focus on maintaining an ethical culture in health care. As clinicians, we practice in an environment that affects the lives of everyone. Our patients and their family members expect high-quality care, patient safety, and use of the latest and most appropriate technology.

In the middle of this climate, we find a health care system that is probably the most entrepreneurial, corporatized, and profit-driven health system in the world. Most of our practice settings (outside the federal government) are for-profit entities. It is easy in this environment to fall victim to conflicts of interest and to acquire an economically oriented practice attitude.

If our first priority is the best possible health care for our patients, then integrity and ethical behavior naturally follow. Professionalism at its very heart places the patient’s interests ahead of our own. We must keep this in mind as we navigate the ever-changing health system.

Next page: Key area number four >>

4. Humanitarianism. I would encourage us to be actively engaged in promoting human welfare and social reforms with no prejudice on grounds of gender, sexual orientation, or religious or ethnic differences. Our goal should be to save lives, relieve suffering, and maintain human dignity.

How do we do this? Many of us have at some point in our careers volunteered our professional services at free clinics or other venues that provide health care to those who otherwise have difficulty accessing it. Some of us take that spirit a step further, traveling abroad on medical missions or responding to natural disasters or civil disturbances.

While using our medical and nursing skills for the good of society is ideal, we can also represent ourselves and our professions well by being good members of the community—not just the “medical” community. Perhaps we provide food and shelter to the homeless in our area or mentor young people.

Anything we do to help not only benefits us and the recipient; it also shows the community that our concept of “care” extends beyond the confines of the clinic or emergency department or operating theater in which we work. We have a very special calling, and I’m always pleased when our professional journals highlight the efforts of our colleagues to “help out”; their stories should inspire us all.

5. Appreciation. As NPs and PAs, we provide health care (whether from a medical or nursing standpoint), a revered calling since the days of Hippocrates. This privilege allows us to enter into a bond with our patients and assist them in a personal and fundamental way. It is no small thing to be involved in curing illness and promoting well-being. We should always remember that our role carries responsibility as well as provides rewards.

Despite the greater availability of diagnostic technologies and advancements in therapeutic abilities, we continue to see increasing disparities in the delivery of health care. Our professions must work diligently to find ways to address the issues of quality, accessibility, and cost of health care in the US. What kind of “stewards” will we be? That is our heritage!

Continue for the last area PAs and NPs need to grow in >>