User login

CE/CME No: CR-1412

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Discuss the evolution in thinking about the pathogenesis of and treatment for vocal cord dysfunction (VCD).

• Describe the three primary functions of the healthy vocal cords.

• List the conditions or factors that may trigger VCD.

• Explain how to differentiate VCD from asthma.

• Develop a treatment plan for VCD that addresses both patient-specific VCD triggers and management of symptomatic episodes.

FACULTY

Linda S. MacConnell is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Physician Assistant Studies and Randy D. Danielsen is a Professor and Dean at the Arizona School of Health Sciences, AT Still University, Mesa. Ms. MacConnell is also a clinical PA affiliated with Enticare, an otolaryngology practice in Chandler, Arizona. Susan Symington is a clinical PA with the Arizona Asthma & Allergy Institute, with which Dr. Danielsen is also affiliated.

Linda MacConnell and Randy Danielsen have no significant financial relationships to disclose. Susan Symington is a member of the speaker’s bureau for Teva Respiratory and Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid for one year from the issue date of December 2014.

Article begins on next page >>

The symptoms of vocal cord dysfunction (VCD) can be mistaken for those

of asthma or other respiratory illnesses. As a result, VCD is often misdiagnosed,

leading to unnecessary, ineffective, costly, or even dangerous treatment. Here are

the facts that will enable you to avoid making an erroneous diagnosis, choosing

potentially harmful treatment, and delaying effective treatment.

A 33-year-old oncology nurse, JD, had moved from Seattle to Phoenix about six months earlier for a job opportunity. Shortly after starting her new job, she had developed intermittent dyspnea on exertion, with a cough lasting several minutes at a time, along with a sensation of heaviness over the larynx and a choking sensation. These symptoms were precipitated by gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), postnasal drainage, stress, and significant environmental change (ie, Seattle to Phoenix). She noticed that, since moving to Phoenix, she frequently cleared her throat but denied any hoarseness, dysphagia, chest tightness, chest pain, or wheezing. She noted nasal congestion and clear nasal discharge on exposure to inhaled irritants (eg, woodstove smoke) and strong fragrances (eg, perfume or cologne).

On physical examination, the patient was alert, oriented, and in no acute distress. She was coughing intermittently but was able to speak in complete sentences. No stridor or dyspnea was noted, either on exertion (jogging in place) or at rest.

HEENT examination was normal, with no scalp lesions or tenderness; face, symmetric; light reflex, symmetric; conjunctivae, clear; sclera white, without lesions or redness; pupils, equal, reactive to light and accommodation; tympanic membranes and canals, clear with intact landmarks; no nasal deformities; nasal mucosa, mildly erythematous with mild engorgement of the turbinates; no nasal polyps seen; nasal septum midline without perforation; no sinus tenderness on percussion; pharynx, clear without exudate; uvula rises on phonation; and oral mucosa and gingivae, pink without lesions. Neck was supple without masses or thyromegaly, and trachea was midline. Lungs were clear to auscultation with normal respiratory movement and no accessory muscle use, with normal anteroposterior diameter. Heart examination revealed regular rate and rhythm, without murmur, clicks, or gallops.

Examination of the skin was normal, without rashes, hives, swelling, petechiae, or significant ecchymosis. There was no palpable cervical, supraclavicular, or axillary adenopathy.

Results of laboratory studies included a normal complete blood count with differential and a normal IgE level of 46.3 IU/mL. Spirometry testing revealed normal values without obstruction; however, there was a flattening of the inspiratory flow loop, with no reversibility after bronchodilator, which was highly suggestive of vocal cord dysfunction (VCD). Perennial nonallergic rhinitis (formerly called vasomotor rhinitis) was confirmed because the patient experienced fewer symptoms to perfume after nasal corticosteroid use. The patient’s GERD was generally well controlled with esomeprazole but was likely a contributing factor to her vocal cord symptoms.

On laryngoscopy, abnormal vocal cord movement toward the midline during both inspiration and expiration was visualized, confirming the diagnosis of VCD.

BACKGROUND

VCD is a partial upper airway obstruction caused by paradoxical adduction (medial movement) of the vocal cords.1 Although it is primarily associated with inspiration, it sometimes manifests during expiration as well.

The true incidence of VCD is uncertain; different studies have found incidence rates varying from 2% to 27%, with higher rates in patients with asthma.1,2 However, highlighting the risk for misdiagnosis, some 10% of patients evaluated for asthma unresponsive to aggressive treatment were found, in fact, to have VCD alone.2

Similarly, although VCD is generally more common in women than in men, the reported female-to-male ratio has varied from 2:1 to 4:1.1,2,4 Some reports suggest that VCD is seen more frequently in younger women, with average ages at diagnosis of 14.5 in adolescents and 33 in adults.2,3 Others identify a broader age range, with most patients older than 50.4

Historically, VCD has been known by a variety of names and has been observed clinically since 1842. In that year, Dunglison referred to it as hysteric croup, describing a disorder of the laryngeal muscles brought on by “hysteria.”5 Later, Mackenzie was able to visualize adduction of the vocal cords during inspiration in patients with stridor by using a laryngoscope.6 Osler demonstrated his understanding of the condition in 1902, stating, “Spasm of muscles may occur with violent inspiratory effort and great distress, and may even lead to cyanosis. Extraordinary cries may be produced either inspiratory or expiratory.”7

More recently, in 1974, Patterson et al reported finding laryngoscopic evidence of VCD, which they termed Munchausen’s stridor.8 They used this descriptor to report on the case of a young woman with 15 hospital admissions for this condition. At the time, the etiology of the condition was believed to be largely psychologic, and its evaluation was consigned to psychiatrists and other mental health practitioners.

As laryngoscopy became more widely available in the 1970s and 1980s, diagnosis of VCD increased, although the condition remains underrecognized.9 Ibrahim et al suggest that primary care clinicians may not be as aware of VCD as they should be and may not consider laryngoscopy for possible VCD in patients whose asthma is poorly controlled.2

Disagreement persists with regard to the preferred name for the condition. Because numerous disorders involve abnormal vocal cord function, Christopher proposed moving away from the broad term VCD and toward a more descriptive term: paradoxical vocal fold motion (PVFM) disorder.10 Interestingly, use of the two terms seems to be divided along specialty lines: VCD is preferred by allergy, pulmonology, and mental health specialists, while PVFM is favored by otolaryngology specialists and speech-language pathologists.11

Further complicating awareness and recognition of VCD is its longstanding reputation as a psychologic disorder. In fact, the paradigm has shifted away from defining VCD as a purely psychopathologic entity to the identification of numerous functional etiologies for the disorder. This, however, has resulted in many new terms to describe the condition, including nonorganic upper airway obstruction, pseudoasthma, irritable larynx syndrome, factitious asthma, spasmodic croup, functional upper airway obstruction, episodic laryngeal dyskinesia, functional laryngeal obstruction, functional laryngeal stridor, and episodic paroxysmal laryngospasm.1

Regardless of its name, an understanding of VCD is essential for both primary care and specialty clinicians because of its frequent misdiagnosis as asthma, allergies, or severe upper airway obstruction. When it is misdiagnosed as asthma, aggressive asthma treatments—to which VCD does not respond—may be prescribed, including high-dose inhaled and systemic corticosteroids and bronchodilators. Patients may experience multiple emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations and, in some cases, may be subjected to tracheostomies and intubation.

Continue for vocal cord physiology and functions >>

VOCAL CORD PHYSIOLOGY AND FUNCTIONS

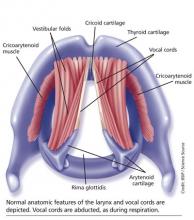

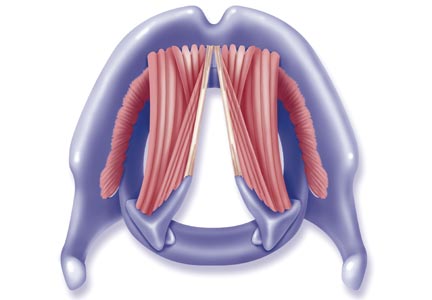

The vocal cords are located within the larynx. Abduction, or opening, of the cords is controlled by the posterior cricoarytenoid muscle; adduction, or closing, occurs via contraction of the lateral cricoarytenoid muscle. These muscles are innervated by the recurrent laryngeal nerve to control the width of the space—the rima glottidis—between the cords. During inspiration, the glottis opens; during expiration, it narrows but remains open.12

The vocal cords are involved in three main functions: protection of the airway, respiration, and phonation (vocal production). These functions are at least partially controlled involuntarily by brain stem reflexes; however, only airway protection—the most important of these functions—is reflexive and involuntary.12 Respiration may be controlled voluntarily, and phonation is primarily voluntary. Closure of the vocal cords is under the control of the laryngeal nerve branches of the vagal nerve.12,13

The vocal cords normally abduct during inspiration to allow air to pass through them into the trachea and the lungs. Sniffing, puffing, snuffling, and panting also cause the vocal cords to abduct. The vocal cords adduct with phonation (talking, singing), coughing, clearing the throat, performing the Valsalva maneuver, and swallowing. During expiration, 10% to 40% adduction is considered normal.14

VOCAL CORD DYSFUNCTION

Pathogenesis and etiology

VCD is a nonspecific term, and a number of factors may be involved in its development.15 Although the precise cause of VCD is unknown, it is believed to result from laryngeal hyperresponsiveness. This exaggerated responsiveness may be prompted by irritant and nonirritant triggers of the sensory receptors in the larynx, trachea, and large airways that mediate cough and glottis closure reflexes.16

VCD may be among a group of airway disorders triggered by occupational exposures, including irritants and psychologic stressors. For example, occupationally triggered VCD was diagnosed in rescue, recovery, and cleanup workers at the World Trade Center disaster site.4

A history of childhood sexual abuse has also been associated by some researchers with the development of VCD. For example, Freedman et al reported that, of 47 patients with VCD, 14 identified such a history and five were suspected of having been sexually abused as children.17

Paradoxical movement of the vocal cords causes them to close when they should open. (Click here for a video on normal and abnormal vocal cord movement.) VCD generally occurs during inspiration, causing obstruction of the incoming air through the larynx. Symptoms of VCD frequently include dyspnea, coughing, wheezing, hoarseness, and tightness or pain in the throat.

Examination of the flow-volume loops recorded when a patient experiences “wheezing” during spirometry testing reveals a flattened inspiratory loop, indicating a decrease of airflow into the lungs (see Figure 1).13,16 “Wheezing” is actually a misnomer in this situation because the term typically refers to sounds that occur during expiration.

Triggers

Physiologic, psychologic, and neurologic factors may all contribute to VCD.1,15 Conditions that can trigger VCD include

• Asthma

• Postnasal drip

• Recent upper respiratory illness (URI)

• Talking, singing

• Exercise

• Cough

• Voice strain

• Stress, anxiety, tension, elevated emotions

• Common irritants (eg, strong smells)

• Airborne irritants

• Rhinosinusitis

• GERD

• Use of certain medications

Identification of a particular patient’s triggers is key to successful management of VCD.

PATIENT PRESENTATION

Although there is no “typical” patient with VCD, the condition occurs more frequently in women, with the most common age at onset between 20 and 40 years. However, VCD has been seen in very young children and in adults as old as 83, and its diagnosis in the pediatric population is increasing.18

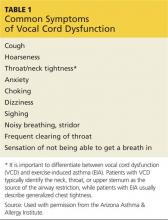

The patient may present with complaints of atypical chest pain, throat tightness, stridor, choking, difficult vocalization, cough and sometimes dysphagia, GERD, or rhinosinusitis (see Table 1). These signs and symptoms may occur without provocation, or patients may relate a history of triggers such as anxiety, irritant exposure, or exercise. In fact, about 14% of VCD is associated with exercise, particularly in young female athletes who experience shortness of breath and even stridor with exercise.19

A characteristic finding on physical examination is inspiratory stridor, along with respiratory distress.20 The stridor is best auscultated not over the anterior chest wall but over the tracheal area of the anterior neck.

Continue for differential diagnosis >>

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Distinguishing VCD from other disorders can be challenging. Differential diagnosis should include

• Non–vocal cord adduction disorders, such as thyroid goiter, upper airway hemorrhage, caustic ingestion, neoplastic disorders, rheumatoid cricoarytenoid arthritis, pharyngeal abscess, angioedema, pulmonary embolus21

• Anatomic defects (eg, laryngomalacia, subglottic stenosis)

• Tracheal masses (eg, enlarged thyroid gland)

• Vocal cord polyps

• Laryngospasm

• Vocal cord paresis

• Neurologic causes (eg, brain stem compression, severe cortical injury, nuclear or lower motor neuron injury, movement disorders)

• Nonorganic causes (eg, factitious symptoms or malingering; conversion disorder)22

• Reactive airway disease.

Some disorders are easier to distinguish from VCD than others. For example, although laryngospasm may produce similar symptoms, episodes are brief, lasting seconds to minutes; VCD episodes may last hours to days.

Asthma

Even the most astute clinician will be unable to obtain adequate information from the patient history to differentiate VCD from asthma. There is a significant overlap of symptoms—shortness of breath, cough, wheezing—and frequently, the diseases coexist. History is often negative for chest pain, but it is common for patients with VCD, when asked to describe their symptoms, to report chest tightness. The clinician therefore needs to ask the patient to point to where the tightness is felt—in the chest or in the neck over the laryngeal area—to distinguish the source.

Asthma symptoms usually increase over a few hours, days, or weeks but respond to medications that open the airway and reduce inflammation (inhaled β-agonists and corticosteroids). VCD symptoms usually occur or decrease suddenly and do not respond well to traditional asthma treatments.

Other differences between asthma and VCD symptoms include voice changes and time of day when symptoms occur. The person with VCD will experience voice changes, such as hoarseness, as well as prolonged coughing episodes. Patients with asthma may awaken at night because of breathlessness, while most patients with VCD experience symptoms only during the day.

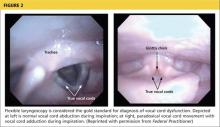

The diagnosis is generally confirmed if VCD is seen on direct laryngoscopic visualization during a symptomatic episode. In terms of adduction, the anterior cords will appear normal, but the posterior portion of the cords will display the classic “glottis chink” (see Figure 2).9

If the diagnosis is in question, videostroboscopy, a technique that provides a magnified slow-motion view of vocal cord vibration, can help identify or exclude pathologic conditions of the vocal cords.23

Convincing the patient of the validity of the diagnosis may be problematic if the patient has been previously diagnosed with and treated for another condition. The diagnosis should be explained and the patient counseled what appropriate care for VCD entails (see discussion under “Patient education and self-care”).

TREATMENT

Acute episode

During an acute VCD episode, offering the patient calm reassurance can be effective in resolving the episode. Simple breathing guidance may also be beneficial; instructing the patient to breathe rapidly and shallowly (ie, pant) can result in immediate resolution of symptoms.24 The patient can be advised to utilize other techniques, such as diaphragmatic breathing, breathing through the nose, breathing through a straw, pursed-lip breathing, and exhaling with a hissing sound.25

Long-term management

Although various strategies are employed in the management of VCD, well-designed studies on which to base treatment decisions have not been performed. Of course, control and management of possible underlying triggers or disorders should be implemented. Because etiology is rarely known, treatment for VCD is generally empiric.

Evidence does exist, however, to suggest that voice therapy, the treatment of choice for muscle tension dysphonia, is also effective for VCD. Speech therapy with specific voice and breathing exercises can enable the patient to manage the condition, thereby reducing ED visits, hospitalizations, and treatment costs.26

Patient education and self-care

Patient education is a critical component of VCD management. The clinician should explain the functions of the larynx to the patient, including the normal functioning of the vocal cords during respiration, speaking, swallowing, coughing, throat clearing, and breath holding. It may also enhance patients’ understanding of VCD to view their diagnostic laryngoscopy or videostroboscopy films.21

The patient should be advised to rest the voice, hydrate, utilize sialagogues (lozenges, gum) to stimulate salivation, reduce exposure to triggers when possible, and decrease stress. She should be encouraged to track VCD triggers by documenting what she is doing, where, and when, at the time of a VCD episode.

Two exercises—“paused breathing” and “belly breathing”—can be used by patients to learn how to relax the vocal cords (see “Patient Handout”). Patients should practice these exercises three times a day so that they can be easily recalled and performed during VCD episodes.

Continue for outcomes >>

OUTCOMES

Little is known about long-term outcomes for patients with VCD. The current literature consists of poorly described and conflicting case reports and results of small trials. Although documentation is lacking, the authors agree that, by educating the patient about the diagnosis, teaching effective VCD management strategies, and referring patients for voice therapy, clinicians can help patients achieve signicant improvement. Further investigation is needed to enhance our knowledge of the causes of VCD and to research additional diagnostic modalities and treatments.2

CASE PATIENT

After diagnosing VCD, the clinician explained the normal functioning of the vocal cords and how certain factors may cause them to close during inspiration. The patient then understood why bronchodilator therapy had failed to relieve her symptoms. She was counseled to continue her inhaled nasal steroid and proton pump inhibitor for her perennial nonallergic rhinitis and GERD, respectively, because these conditions may trigger her VCD, and to take steps to manage her stress. She learned breathing techniques to alleviate acute episodes of VCD and was informed of the option of voice therapy with a speech therapist if needed.

At six-week follow-up, the patient reported that she was complying with her medication regimen, had made an effort to relax more, and had experienced no acute attacks of VCD since her last visit.

CONCLUSION

Patients with symptoms suggestive of VCD require a thorough evaluation, including laryngoscopic examination, to ensure accurate diagnosis and avoid a too-common misdiagnosis. Primary care clinicians should know about VCD and, if not trained in the performance of flexible laryngoscopy, should refer the symptomatic patient to a specialist for appropriate work-up.

1. Hoyte FCL. Vocal cord dysfunction. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2013;33:1-22.

2. Ibrahim WH, Gheriani HA, Almohamed AA, Raza T. Paradoxical vocal cord motion disorder: past, present and future. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:164-172.

3. Powell DM, Karanfilov BI, Beechler KB, et al. Paradoxical vocal cord dysfunction in juveniles. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126(1):29-34.

4. Husein OF, Husein TN, Gardner R, et al. Formal psychological testing in patients with paradoxical vocal fold dysfunction. Laryngoscope. 2008; 118(4):740-747.

5. Dunglison RD. The Practice of Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lea and Blanchard; 1842:257-258.

6. MacKenzie M. Use of Laryngoscopy in Diseases of the Throat. Philadelphia, PA: Lindsey and Blackeston; 1869:246-250.

7. Osler W. Hysteria. In: The Principles and Practice of Medicine. 4th ed. New York, NY: Appleton; 1902:1111-1112.

8. Patterson R, Schatz M, Horton M. Munchausen’s stridor: non-organic laryngeal obstruction. Clin Allergy. 1974;4:307-310.

9. Christopher KL, Wood RP 2nd, Eckert RC, et al. Vocal cord dysfunction presenting as asthma. N Engl J Med. 1983;308(26):1566-1570.

10. Christopher KL. Understanding vocal cord dysfunction: a step in the right direction with a long road ahead. Chest. 2006;129(4):842-843.

11. Christopher KL, Morris MJ. Vocal cord dysfunction, paradoxic vocal fold motion, or laryngomalacia? Our understanding requires an interdisciplinary approach. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 2010;43:43-66.

12. Sasaki CT, Weaver EM. Physiology of the larynx. Am J Med. 1997;103:9S-18S.

13. Balkissoon R. Occupational upper airway disease. Clin Chest Med. 2002;23:717-725.

14. Murakami Y, Kirschner JA. Mechanical and physiological properties of reflex laryngeal closure. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1972;81(1):59-71.

15. Forrest LA, Husein T, Husein O. Paradoxical vocal cord motion disorder: classification and treatment. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:844-853.

16. Altman KW, Simpson CB, Amin MR, et al. Cough and paradoxical vocal fold motion. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127(6):501-511.

17. Freedman MR, Rosenberg SJ, Schmaling KB. Childhood sexual abuse in patients with paradoxical vocal cord dysfunction. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1991;179(5):295-298.

18. Buddiga P. Vocal cord dysfunction. Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/137782-overview. Accessed November 12, 2014.

19. Chiang T, Marcinow AM, deSilva BW, et al. Exercise-induced paradoxical vocal fold motion disorder: diagnosis and management. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:727-731.

20. Morris MJ, Deal LE, Bean DR, et al. Vocal cord dysfunction in patients with exertional dyspnea. Chest. 1999;116(6):1676-1682.

21. Hicks M, Brugman SM, Katial R. Vocal cord dysfunction/paradoxical vocal fold motion. Prim Care. 2008;35(1):81-103.

22. Maschka DA, Bauman NM, McCray PB, et al. A classification scheme for paradoxical vocal fold motion. Laryngoscope. 1997;107(11):1429-1435.

23. Uloza V, Vegiene A, Pribuisiene R, Saferis V. Quantitative evaluation of video laryngostroboscopy: reliability of the basic parameters. J Voice. 2013;27(3):361-368.

24. Pitchenik AF. Functional laryngeal obstruction relieved by panting. Chest. 1991;100(5):1465-1467.

25. Deckert J, Deckert L. Vocal cord dysfunction. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81(2):156-160.

26. Carding PN, Horsley IA, Docherty GJ. A study of the effectiveness of voice therapy in the treatment of 45 patients with nonorganic dysphonia. J Voice. 1999;13(1):72-104.

CE/CME No: CR-1412

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Discuss the evolution in thinking about the pathogenesis of and treatment for vocal cord dysfunction (VCD).

• Describe the three primary functions of the healthy vocal cords.

• List the conditions or factors that may trigger VCD.

• Explain how to differentiate VCD from asthma.

• Develop a treatment plan for VCD that addresses both patient-specific VCD triggers and management of symptomatic episodes.

FACULTY

Linda S. MacConnell is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Physician Assistant Studies and Randy D. Danielsen is a Professor and Dean at the Arizona School of Health Sciences, AT Still University, Mesa. Ms. MacConnell is also a clinical PA affiliated with Enticare, an otolaryngology practice in Chandler, Arizona. Susan Symington is a clinical PA with the Arizona Asthma & Allergy Institute, with which Dr. Danielsen is also affiliated.

Linda MacConnell and Randy Danielsen have no significant financial relationships to disclose. Susan Symington is a member of the speaker’s bureau for Teva Respiratory and Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid for one year from the issue date of December 2014.

Article begins on next page >>

The symptoms of vocal cord dysfunction (VCD) can be mistaken for those

of asthma or other respiratory illnesses. As a result, VCD is often misdiagnosed,

leading to unnecessary, ineffective, costly, or even dangerous treatment. Here are

the facts that will enable you to avoid making an erroneous diagnosis, choosing

potentially harmful treatment, and delaying effective treatment.

A 33-year-old oncology nurse, JD, had moved from Seattle to Phoenix about six months earlier for a job opportunity. Shortly after starting her new job, she had developed intermittent dyspnea on exertion, with a cough lasting several minutes at a time, along with a sensation of heaviness over the larynx and a choking sensation. These symptoms were precipitated by gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), postnasal drainage, stress, and significant environmental change (ie, Seattle to Phoenix). She noticed that, since moving to Phoenix, she frequently cleared her throat but denied any hoarseness, dysphagia, chest tightness, chest pain, or wheezing. She noted nasal congestion and clear nasal discharge on exposure to inhaled irritants (eg, woodstove smoke) and strong fragrances (eg, perfume or cologne).

On physical examination, the patient was alert, oriented, and in no acute distress. She was coughing intermittently but was able to speak in complete sentences. No stridor or dyspnea was noted, either on exertion (jogging in place) or at rest.

HEENT examination was normal, with no scalp lesions or tenderness; face, symmetric; light reflex, symmetric; conjunctivae, clear; sclera white, without lesions or redness; pupils, equal, reactive to light and accommodation; tympanic membranes and canals, clear with intact landmarks; no nasal deformities; nasal mucosa, mildly erythematous with mild engorgement of the turbinates; no nasal polyps seen; nasal septum midline without perforation; no sinus tenderness on percussion; pharynx, clear without exudate; uvula rises on phonation; and oral mucosa and gingivae, pink without lesions. Neck was supple without masses or thyromegaly, and trachea was midline. Lungs were clear to auscultation with normal respiratory movement and no accessory muscle use, with normal anteroposterior diameter. Heart examination revealed regular rate and rhythm, without murmur, clicks, or gallops.

Examination of the skin was normal, without rashes, hives, swelling, petechiae, or significant ecchymosis. There was no palpable cervical, supraclavicular, or axillary adenopathy.

Results of laboratory studies included a normal complete blood count with differential and a normal IgE level of 46.3 IU/mL. Spirometry testing revealed normal values without obstruction; however, there was a flattening of the inspiratory flow loop, with no reversibility after bronchodilator, which was highly suggestive of vocal cord dysfunction (VCD). Perennial nonallergic rhinitis (formerly called vasomotor rhinitis) was confirmed because the patient experienced fewer symptoms to perfume after nasal corticosteroid use. The patient’s GERD was generally well controlled with esomeprazole but was likely a contributing factor to her vocal cord symptoms.

On laryngoscopy, abnormal vocal cord movement toward the midline during both inspiration and expiration was visualized, confirming the diagnosis of VCD.

BACKGROUND

VCD is a partial upper airway obstruction caused by paradoxical adduction (medial movement) of the vocal cords.1 Although it is primarily associated with inspiration, it sometimes manifests during expiration as well.

The true incidence of VCD is uncertain; different studies have found incidence rates varying from 2% to 27%, with higher rates in patients with asthma.1,2 However, highlighting the risk for misdiagnosis, some 10% of patients evaluated for asthma unresponsive to aggressive treatment were found, in fact, to have VCD alone.2

Similarly, although VCD is generally more common in women than in men, the reported female-to-male ratio has varied from 2:1 to 4:1.1,2,4 Some reports suggest that VCD is seen more frequently in younger women, with average ages at diagnosis of 14.5 in adolescents and 33 in adults.2,3 Others identify a broader age range, with most patients older than 50.4

Historically, VCD has been known by a variety of names and has been observed clinically since 1842. In that year, Dunglison referred to it as hysteric croup, describing a disorder of the laryngeal muscles brought on by “hysteria.”5 Later, Mackenzie was able to visualize adduction of the vocal cords during inspiration in patients with stridor by using a laryngoscope.6 Osler demonstrated his understanding of the condition in 1902, stating, “Spasm of muscles may occur with violent inspiratory effort and great distress, and may even lead to cyanosis. Extraordinary cries may be produced either inspiratory or expiratory.”7

More recently, in 1974, Patterson et al reported finding laryngoscopic evidence of VCD, which they termed Munchausen’s stridor.8 They used this descriptor to report on the case of a young woman with 15 hospital admissions for this condition. At the time, the etiology of the condition was believed to be largely psychologic, and its evaluation was consigned to psychiatrists and other mental health practitioners.

As laryngoscopy became more widely available in the 1970s and 1980s, diagnosis of VCD increased, although the condition remains underrecognized.9 Ibrahim et al suggest that primary care clinicians may not be as aware of VCD as they should be and may not consider laryngoscopy for possible VCD in patients whose asthma is poorly controlled.2

Disagreement persists with regard to the preferred name for the condition. Because numerous disorders involve abnormal vocal cord function, Christopher proposed moving away from the broad term VCD and toward a more descriptive term: paradoxical vocal fold motion (PVFM) disorder.10 Interestingly, use of the two terms seems to be divided along specialty lines: VCD is preferred by allergy, pulmonology, and mental health specialists, while PVFM is favored by otolaryngology specialists and speech-language pathologists.11

Further complicating awareness and recognition of VCD is its longstanding reputation as a psychologic disorder. In fact, the paradigm has shifted away from defining VCD as a purely psychopathologic entity to the identification of numerous functional etiologies for the disorder. This, however, has resulted in many new terms to describe the condition, including nonorganic upper airway obstruction, pseudoasthma, irritable larynx syndrome, factitious asthma, spasmodic croup, functional upper airway obstruction, episodic laryngeal dyskinesia, functional laryngeal obstruction, functional laryngeal stridor, and episodic paroxysmal laryngospasm.1

Regardless of its name, an understanding of VCD is essential for both primary care and specialty clinicians because of its frequent misdiagnosis as asthma, allergies, or severe upper airway obstruction. When it is misdiagnosed as asthma, aggressive asthma treatments—to which VCD does not respond—may be prescribed, including high-dose inhaled and systemic corticosteroids and bronchodilators. Patients may experience multiple emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations and, in some cases, may be subjected to tracheostomies and intubation.

Continue for vocal cord physiology and functions >>

VOCAL CORD PHYSIOLOGY AND FUNCTIONS

The vocal cords are located within the larynx. Abduction, or opening, of the cords is controlled by the posterior cricoarytenoid muscle; adduction, or closing, occurs via contraction of the lateral cricoarytenoid muscle. These muscles are innervated by the recurrent laryngeal nerve to control the width of the space—the rima glottidis—between the cords. During inspiration, the glottis opens; during expiration, it narrows but remains open.12

The vocal cords are involved in three main functions: protection of the airway, respiration, and phonation (vocal production). These functions are at least partially controlled involuntarily by brain stem reflexes; however, only airway protection—the most important of these functions—is reflexive and involuntary.12 Respiration may be controlled voluntarily, and phonation is primarily voluntary. Closure of the vocal cords is under the control of the laryngeal nerve branches of the vagal nerve.12,13

The vocal cords normally abduct during inspiration to allow air to pass through them into the trachea and the lungs. Sniffing, puffing, snuffling, and panting also cause the vocal cords to abduct. The vocal cords adduct with phonation (talking, singing), coughing, clearing the throat, performing the Valsalva maneuver, and swallowing. During expiration, 10% to 40% adduction is considered normal.14

VOCAL CORD DYSFUNCTION

Pathogenesis and etiology

VCD is a nonspecific term, and a number of factors may be involved in its development.15 Although the precise cause of VCD is unknown, it is believed to result from laryngeal hyperresponsiveness. This exaggerated responsiveness may be prompted by irritant and nonirritant triggers of the sensory receptors in the larynx, trachea, and large airways that mediate cough and glottis closure reflexes.16

VCD may be among a group of airway disorders triggered by occupational exposures, including irritants and psychologic stressors. For example, occupationally triggered VCD was diagnosed in rescue, recovery, and cleanup workers at the World Trade Center disaster site.4

A history of childhood sexual abuse has also been associated by some researchers with the development of VCD. For example, Freedman et al reported that, of 47 patients with VCD, 14 identified such a history and five were suspected of having been sexually abused as children.17

Paradoxical movement of the vocal cords causes them to close when they should open. (Click here for a video on normal and abnormal vocal cord movement.) VCD generally occurs during inspiration, causing obstruction of the incoming air through the larynx. Symptoms of VCD frequently include dyspnea, coughing, wheezing, hoarseness, and tightness or pain in the throat.

Examination of the flow-volume loops recorded when a patient experiences “wheezing” during spirometry testing reveals a flattened inspiratory loop, indicating a decrease of airflow into the lungs (see Figure 1).13,16 “Wheezing” is actually a misnomer in this situation because the term typically refers to sounds that occur during expiration.

Triggers

Physiologic, psychologic, and neurologic factors may all contribute to VCD.1,15 Conditions that can trigger VCD include

• Asthma

• Postnasal drip

• Recent upper respiratory illness (URI)

• Talking, singing

• Exercise

• Cough

• Voice strain

• Stress, anxiety, tension, elevated emotions

• Common irritants (eg, strong smells)

• Airborne irritants

• Rhinosinusitis

• GERD

• Use of certain medications

Identification of a particular patient’s triggers is key to successful management of VCD.

PATIENT PRESENTATION

Although there is no “typical” patient with VCD, the condition occurs more frequently in women, with the most common age at onset between 20 and 40 years. However, VCD has been seen in very young children and in adults as old as 83, and its diagnosis in the pediatric population is increasing.18

The patient may present with complaints of atypical chest pain, throat tightness, stridor, choking, difficult vocalization, cough and sometimes dysphagia, GERD, or rhinosinusitis (see Table 1). These signs and symptoms may occur without provocation, or patients may relate a history of triggers such as anxiety, irritant exposure, or exercise. In fact, about 14% of VCD is associated with exercise, particularly in young female athletes who experience shortness of breath and even stridor with exercise.19

A characteristic finding on physical examination is inspiratory stridor, along with respiratory distress.20 The stridor is best auscultated not over the anterior chest wall but over the tracheal area of the anterior neck.

Continue for differential diagnosis >>

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Distinguishing VCD from other disorders can be challenging. Differential diagnosis should include

• Non–vocal cord adduction disorders, such as thyroid goiter, upper airway hemorrhage, caustic ingestion, neoplastic disorders, rheumatoid cricoarytenoid arthritis, pharyngeal abscess, angioedema, pulmonary embolus21

• Anatomic defects (eg, laryngomalacia, subglottic stenosis)

• Tracheal masses (eg, enlarged thyroid gland)

• Vocal cord polyps

• Laryngospasm

• Vocal cord paresis

• Neurologic causes (eg, brain stem compression, severe cortical injury, nuclear or lower motor neuron injury, movement disorders)

• Nonorganic causes (eg, factitious symptoms or malingering; conversion disorder)22

• Reactive airway disease.

Some disorders are easier to distinguish from VCD than others. For example, although laryngospasm may produce similar symptoms, episodes are brief, lasting seconds to minutes; VCD episodes may last hours to days.

Asthma

Even the most astute clinician will be unable to obtain adequate information from the patient history to differentiate VCD from asthma. There is a significant overlap of symptoms—shortness of breath, cough, wheezing—and frequently, the diseases coexist. History is often negative for chest pain, but it is common for patients with VCD, when asked to describe their symptoms, to report chest tightness. The clinician therefore needs to ask the patient to point to where the tightness is felt—in the chest or in the neck over the laryngeal area—to distinguish the source.

Asthma symptoms usually increase over a few hours, days, or weeks but respond to medications that open the airway and reduce inflammation (inhaled β-agonists and corticosteroids). VCD symptoms usually occur or decrease suddenly and do not respond well to traditional asthma treatments.

Other differences between asthma and VCD symptoms include voice changes and time of day when symptoms occur. The person with VCD will experience voice changes, such as hoarseness, as well as prolonged coughing episodes. Patients with asthma may awaken at night because of breathlessness, while most patients with VCD experience symptoms only during the day.

The diagnosis is generally confirmed if VCD is seen on direct laryngoscopic visualization during a symptomatic episode. In terms of adduction, the anterior cords will appear normal, but the posterior portion of the cords will display the classic “glottis chink” (see Figure 2).9

If the diagnosis is in question, videostroboscopy, a technique that provides a magnified slow-motion view of vocal cord vibration, can help identify or exclude pathologic conditions of the vocal cords.23

Convincing the patient of the validity of the diagnosis may be problematic if the patient has been previously diagnosed with and treated for another condition. The diagnosis should be explained and the patient counseled what appropriate care for VCD entails (see discussion under “Patient education and self-care”).

TREATMENT

Acute episode

During an acute VCD episode, offering the patient calm reassurance can be effective in resolving the episode. Simple breathing guidance may also be beneficial; instructing the patient to breathe rapidly and shallowly (ie, pant) can result in immediate resolution of symptoms.24 The patient can be advised to utilize other techniques, such as diaphragmatic breathing, breathing through the nose, breathing through a straw, pursed-lip breathing, and exhaling with a hissing sound.25

Long-term management

Although various strategies are employed in the management of VCD, well-designed studies on which to base treatment decisions have not been performed. Of course, control and management of possible underlying triggers or disorders should be implemented. Because etiology is rarely known, treatment for VCD is generally empiric.

Evidence does exist, however, to suggest that voice therapy, the treatment of choice for muscle tension dysphonia, is also effective for VCD. Speech therapy with specific voice and breathing exercises can enable the patient to manage the condition, thereby reducing ED visits, hospitalizations, and treatment costs.26

Patient education and self-care

Patient education is a critical component of VCD management. The clinician should explain the functions of the larynx to the patient, including the normal functioning of the vocal cords during respiration, speaking, swallowing, coughing, throat clearing, and breath holding. It may also enhance patients’ understanding of VCD to view their diagnostic laryngoscopy or videostroboscopy films.21

The patient should be advised to rest the voice, hydrate, utilize sialagogues (lozenges, gum) to stimulate salivation, reduce exposure to triggers when possible, and decrease stress. She should be encouraged to track VCD triggers by documenting what she is doing, where, and when, at the time of a VCD episode.

Two exercises—“paused breathing” and “belly breathing”—can be used by patients to learn how to relax the vocal cords (see “Patient Handout”). Patients should practice these exercises three times a day so that they can be easily recalled and performed during VCD episodes.

Continue for outcomes >>

OUTCOMES

Little is known about long-term outcomes for patients with VCD. The current literature consists of poorly described and conflicting case reports and results of small trials. Although documentation is lacking, the authors agree that, by educating the patient about the diagnosis, teaching effective VCD management strategies, and referring patients for voice therapy, clinicians can help patients achieve signicant improvement. Further investigation is needed to enhance our knowledge of the causes of VCD and to research additional diagnostic modalities and treatments.2

CASE PATIENT

After diagnosing VCD, the clinician explained the normal functioning of the vocal cords and how certain factors may cause them to close during inspiration. The patient then understood why bronchodilator therapy had failed to relieve her symptoms. She was counseled to continue her inhaled nasal steroid and proton pump inhibitor for her perennial nonallergic rhinitis and GERD, respectively, because these conditions may trigger her VCD, and to take steps to manage her stress. She learned breathing techniques to alleviate acute episodes of VCD and was informed of the option of voice therapy with a speech therapist if needed.

At six-week follow-up, the patient reported that she was complying with her medication regimen, had made an effort to relax more, and had experienced no acute attacks of VCD since her last visit.

CONCLUSION

Patients with symptoms suggestive of VCD require a thorough evaluation, including laryngoscopic examination, to ensure accurate diagnosis and avoid a too-common misdiagnosis. Primary care clinicians should know about VCD and, if not trained in the performance of flexible laryngoscopy, should refer the symptomatic patient to a specialist for appropriate work-up.

CE/CME No: CR-1412

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Discuss the evolution in thinking about the pathogenesis of and treatment for vocal cord dysfunction (VCD).

• Describe the three primary functions of the healthy vocal cords.

• List the conditions or factors that may trigger VCD.

• Explain how to differentiate VCD from asthma.

• Develop a treatment plan for VCD that addresses both patient-specific VCD triggers and management of symptomatic episodes.

FACULTY

Linda S. MacConnell is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Physician Assistant Studies and Randy D. Danielsen is a Professor and Dean at the Arizona School of Health Sciences, AT Still University, Mesa. Ms. MacConnell is also a clinical PA affiliated with Enticare, an otolaryngology practice in Chandler, Arizona. Susan Symington is a clinical PA with the Arizona Asthma & Allergy Institute, with which Dr. Danielsen is also affiliated.

Linda MacConnell and Randy Danielsen have no significant financial relationships to disclose. Susan Symington is a member of the speaker’s bureau for Teva Respiratory and Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid for one year from the issue date of December 2014.

Article begins on next page >>

The symptoms of vocal cord dysfunction (VCD) can be mistaken for those

of asthma or other respiratory illnesses. As a result, VCD is often misdiagnosed,

leading to unnecessary, ineffective, costly, or even dangerous treatment. Here are

the facts that will enable you to avoid making an erroneous diagnosis, choosing

potentially harmful treatment, and delaying effective treatment.

A 33-year-old oncology nurse, JD, had moved from Seattle to Phoenix about six months earlier for a job opportunity. Shortly after starting her new job, she had developed intermittent dyspnea on exertion, with a cough lasting several minutes at a time, along with a sensation of heaviness over the larynx and a choking sensation. These symptoms were precipitated by gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), postnasal drainage, stress, and significant environmental change (ie, Seattle to Phoenix). She noticed that, since moving to Phoenix, she frequently cleared her throat but denied any hoarseness, dysphagia, chest tightness, chest pain, or wheezing. She noted nasal congestion and clear nasal discharge on exposure to inhaled irritants (eg, woodstove smoke) and strong fragrances (eg, perfume or cologne).

On physical examination, the patient was alert, oriented, and in no acute distress. She was coughing intermittently but was able to speak in complete sentences. No stridor or dyspnea was noted, either on exertion (jogging in place) or at rest.

HEENT examination was normal, with no scalp lesions or tenderness; face, symmetric; light reflex, symmetric; conjunctivae, clear; sclera white, without lesions or redness; pupils, equal, reactive to light and accommodation; tympanic membranes and canals, clear with intact landmarks; no nasal deformities; nasal mucosa, mildly erythematous with mild engorgement of the turbinates; no nasal polyps seen; nasal septum midline without perforation; no sinus tenderness on percussion; pharynx, clear without exudate; uvula rises on phonation; and oral mucosa and gingivae, pink without lesions. Neck was supple without masses or thyromegaly, and trachea was midline. Lungs were clear to auscultation with normal respiratory movement and no accessory muscle use, with normal anteroposterior diameter. Heart examination revealed regular rate and rhythm, without murmur, clicks, or gallops.

Examination of the skin was normal, without rashes, hives, swelling, petechiae, or significant ecchymosis. There was no palpable cervical, supraclavicular, or axillary adenopathy.

Results of laboratory studies included a normal complete blood count with differential and a normal IgE level of 46.3 IU/mL. Spirometry testing revealed normal values without obstruction; however, there was a flattening of the inspiratory flow loop, with no reversibility after bronchodilator, which was highly suggestive of vocal cord dysfunction (VCD). Perennial nonallergic rhinitis (formerly called vasomotor rhinitis) was confirmed because the patient experienced fewer symptoms to perfume after nasal corticosteroid use. The patient’s GERD was generally well controlled with esomeprazole but was likely a contributing factor to her vocal cord symptoms.

On laryngoscopy, abnormal vocal cord movement toward the midline during both inspiration and expiration was visualized, confirming the diagnosis of VCD.

BACKGROUND

VCD is a partial upper airway obstruction caused by paradoxical adduction (medial movement) of the vocal cords.1 Although it is primarily associated with inspiration, it sometimes manifests during expiration as well.

The true incidence of VCD is uncertain; different studies have found incidence rates varying from 2% to 27%, with higher rates in patients with asthma.1,2 However, highlighting the risk for misdiagnosis, some 10% of patients evaluated for asthma unresponsive to aggressive treatment were found, in fact, to have VCD alone.2

Similarly, although VCD is generally more common in women than in men, the reported female-to-male ratio has varied from 2:1 to 4:1.1,2,4 Some reports suggest that VCD is seen more frequently in younger women, with average ages at diagnosis of 14.5 in adolescents and 33 in adults.2,3 Others identify a broader age range, with most patients older than 50.4

Historically, VCD has been known by a variety of names and has been observed clinically since 1842. In that year, Dunglison referred to it as hysteric croup, describing a disorder of the laryngeal muscles brought on by “hysteria.”5 Later, Mackenzie was able to visualize adduction of the vocal cords during inspiration in patients with stridor by using a laryngoscope.6 Osler demonstrated his understanding of the condition in 1902, stating, “Spasm of muscles may occur with violent inspiratory effort and great distress, and may even lead to cyanosis. Extraordinary cries may be produced either inspiratory or expiratory.”7

More recently, in 1974, Patterson et al reported finding laryngoscopic evidence of VCD, which they termed Munchausen’s stridor.8 They used this descriptor to report on the case of a young woman with 15 hospital admissions for this condition. At the time, the etiology of the condition was believed to be largely psychologic, and its evaluation was consigned to psychiatrists and other mental health practitioners.

As laryngoscopy became more widely available in the 1970s and 1980s, diagnosis of VCD increased, although the condition remains underrecognized.9 Ibrahim et al suggest that primary care clinicians may not be as aware of VCD as they should be and may not consider laryngoscopy for possible VCD in patients whose asthma is poorly controlled.2

Disagreement persists with regard to the preferred name for the condition. Because numerous disorders involve abnormal vocal cord function, Christopher proposed moving away from the broad term VCD and toward a more descriptive term: paradoxical vocal fold motion (PVFM) disorder.10 Interestingly, use of the two terms seems to be divided along specialty lines: VCD is preferred by allergy, pulmonology, and mental health specialists, while PVFM is favored by otolaryngology specialists and speech-language pathologists.11

Further complicating awareness and recognition of VCD is its longstanding reputation as a psychologic disorder. In fact, the paradigm has shifted away from defining VCD as a purely psychopathologic entity to the identification of numerous functional etiologies for the disorder. This, however, has resulted in many new terms to describe the condition, including nonorganic upper airway obstruction, pseudoasthma, irritable larynx syndrome, factitious asthma, spasmodic croup, functional upper airway obstruction, episodic laryngeal dyskinesia, functional laryngeal obstruction, functional laryngeal stridor, and episodic paroxysmal laryngospasm.1

Regardless of its name, an understanding of VCD is essential for both primary care and specialty clinicians because of its frequent misdiagnosis as asthma, allergies, or severe upper airway obstruction. When it is misdiagnosed as asthma, aggressive asthma treatments—to which VCD does not respond—may be prescribed, including high-dose inhaled and systemic corticosteroids and bronchodilators. Patients may experience multiple emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations and, in some cases, may be subjected to tracheostomies and intubation.

Continue for vocal cord physiology and functions >>

VOCAL CORD PHYSIOLOGY AND FUNCTIONS

The vocal cords are located within the larynx. Abduction, or opening, of the cords is controlled by the posterior cricoarytenoid muscle; adduction, or closing, occurs via contraction of the lateral cricoarytenoid muscle. These muscles are innervated by the recurrent laryngeal nerve to control the width of the space—the rima glottidis—between the cords. During inspiration, the glottis opens; during expiration, it narrows but remains open.12

The vocal cords are involved in three main functions: protection of the airway, respiration, and phonation (vocal production). These functions are at least partially controlled involuntarily by brain stem reflexes; however, only airway protection—the most important of these functions—is reflexive and involuntary.12 Respiration may be controlled voluntarily, and phonation is primarily voluntary. Closure of the vocal cords is under the control of the laryngeal nerve branches of the vagal nerve.12,13

The vocal cords normally abduct during inspiration to allow air to pass through them into the trachea and the lungs. Sniffing, puffing, snuffling, and panting also cause the vocal cords to abduct. The vocal cords adduct with phonation (talking, singing), coughing, clearing the throat, performing the Valsalva maneuver, and swallowing. During expiration, 10% to 40% adduction is considered normal.14

VOCAL CORD DYSFUNCTION

Pathogenesis and etiology

VCD is a nonspecific term, and a number of factors may be involved in its development.15 Although the precise cause of VCD is unknown, it is believed to result from laryngeal hyperresponsiveness. This exaggerated responsiveness may be prompted by irritant and nonirritant triggers of the sensory receptors in the larynx, trachea, and large airways that mediate cough and glottis closure reflexes.16

VCD may be among a group of airway disorders triggered by occupational exposures, including irritants and psychologic stressors. For example, occupationally triggered VCD was diagnosed in rescue, recovery, and cleanup workers at the World Trade Center disaster site.4

A history of childhood sexual abuse has also been associated by some researchers with the development of VCD. For example, Freedman et al reported that, of 47 patients with VCD, 14 identified such a history and five were suspected of having been sexually abused as children.17

Paradoxical movement of the vocal cords causes them to close when they should open. (Click here for a video on normal and abnormal vocal cord movement.) VCD generally occurs during inspiration, causing obstruction of the incoming air through the larynx. Symptoms of VCD frequently include dyspnea, coughing, wheezing, hoarseness, and tightness or pain in the throat.

Examination of the flow-volume loops recorded when a patient experiences “wheezing” during spirometry testing reveals a flattened inspiratory loop, indicating a decrease of airflow into the lungs (see Figure 1).13,16 “Wheezing” is actually a misnomer in this situation because the term typically refers to sounds that occur during expiration.

Triggers

Physiologic, psychologic, and neurologic factors may all contribute to VCD.1,15 Conditions that can trigger VCD include

• Asthma

• Postnasal drip

• Recent upper respiratory illness (URI)

• Talking, singing

• Exercise

• Cough

• Voice strain

• Stress, anxiety, tension, elevated emotions

• Common irritants (eg, strong smells)

• Airborne irritants

• Rhinosinusitis

• GERD

• Use of certain medications

Identification of a particular patient’s triggers is key to successful management of VCD.

PATIENT PRESENTATION

Although there is no “typical” patient with VCD, the condition occurs more frequently in women, with the most common age at onset between 20 and 40 years. However, VCD has been seen in very young children and in adults as old as 83, and its diagnosis in the pediatric population is increasing.18

The patient may present with complaints of atypical chest pain, throat tightness, stridor, choking, difficult vocalization, cough and sometimes dysphagia, GERD, or rhinosinusitis (see Table 1). These signs and symptoms may occur without provocation, or patients may relate a history of triggers such as anxiety, irritant exposure, or exercise. In fact, about 14% of VCD is associated with exercise, particularly in young female athletes who experience shortness of breath and even stridor with exercise.19

A characteristic finding on physical examination is inspiratory stridor, along with respiratory distress.20 The stridor is best auscultated not over the anterior chest wall but over the tracheal area of the anterior neck.

Continue for differential diagnosis >>

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Distinguishing VCD from other disorders can be challenging. Differential diagnosis should include

• Non–vocal cord adduction disorders, such as thyroid goiter, upper airway hemorrhage, caustic ingestion, neoplastic disorders, rheumatoid cricoarytenoid arthritis, pharyngeal abscess, angioedema, pulmonary embolus21

• Anatomic defects (eg, laryngomalacia, subglottic stenosis)

• Tracheal masses (eg, enlarged thyroid gland)

• Vocal cord polyps

• Laryngospasm

• Vocal cord paresis

• Neurologic causes (eg, brain stem compression, severe cortical injury, nuclear or lower motor neuron injury, movement disorders)

• Nonorganic causes (eg, factitious symptoms or malingering; conversion disorder)22

• Reactive airway disease.

Some disorders are easier to distinguish from VCD than others. For example, although laryngospasm may produce similar symptoms, episodes are brief, lasting seconds to minutes; VCD episodes may last hours to days.

Asthma

Even the most astute clinician will be unable to obtain adequate information from the patient history to differentiate VCD from asthma. There is a significant overlap of symptoms—shortness of breath, cough, wheezing—and frequently, the diseases coexist. History is often negative for chest pain, but it is common for patients with VCD, when asked to describe their symptoms, to report chest tightness. The clinician therefore needs to ask the patient to point to where the tightness is felt—in the chest or in the neck over the laryngeal area—to distinguish the source.

Asthma symptoms usually increase over a few hours, days, or weeks but respond to medications that open the airway and reduce inflammation (inhaled β-agonists and corticosteroids). VCD symptoms usually occur or decrease suddenly and do not respond well to traditional asthma treatments.

Other differences between asthma and VCD symptoms include voice changes and time of day when symptoms occur. The person with VCD will experience voice changes, such as hoarseness, as well as prolonged coughing episodes. Patients with asthma may awaken at night because of breathlessness, while most patients with VCD experience symptoms only during the day.

The diagnosis is generally confirmed if VCD is seen on direct laryngoscopic visualization during a symptomatic episode. In terms of adduction, the anterior cords will appear normal, but the posterior portion of the cords will display the classic “glottis chink” (see Figure 2).9

If the diagnosis is in question, videostroboscopy, a technique that provides a magnified slow-motion view of vocal cord vibration, can help identify or exclude pathologic conditions of the vocal cords.23

Convincing the patient of the validity of the diagnosis may be problematic if the patient has been previously diagnosed with and treated for another condition. The diagnosis should be explained and the patient counseled what appropriate care for VCD entails (see discussion under “Patient education and self-care”).

TREATMENT

Acute episode

During an acute VCD episode, offering the patient calm reassurance can be effective in resolving the episode. Simple breathing guidance may also be beneficial; instructing the patient to breathe rapidly and shallowly (ie, pant) can result in immediate resolution of symptoms.24 The patient can be advised to utilize other techniques, such as diaphragmatic breathing, breathing through the nose, breathing through a straw, pursed-lip breathing, and exhaling with a hissing sound.25

Long-term management

Although various strategies are employed in the management of VCD, well-designed studies on which to base treatment decisions have not been performed. Of course, control and management of possible underlying triggers or disorders should be implemented. Because etiology is rarely known, treatment for VCD is generally empiric.

Evidence does exist, however, to suggest that voice therapy, the treatment of choice for muscle tension dysphonia, is also effective for VCD. Speech therapy with specific voice and breathing exercises can enable the patient to manage the condition, thereby reducing ED visits, hospitalizations, and treatment costs.26

Patient education and self-care

Patient education is a critical component of VCD management. The clinician should explain the functions of the larynx to the patient, including the normal functioning of the vocal cords during respiration, speaking, swallowing, coughing, throat clearing, and breath holding. It may also enhance patients’ understanding of VCD to view their diagnostic laryngoscopy or videostroboscopy films.21

The patient should be advised to rest the voice, hydrate, utilize sialagogues (lozenges, gum) to stimulate salivation, reduce exposure to triggers when possible, and decrease stress. She should be encouraged to track VCD triggers by documenting what she is doing, where, and when, at the time of a VCD episode.

Two exercises—“paused breathing” and “belly breathing”—can be used by patients to learn how to relax the vocal cords (see “Patient Handout”). Patients should practice these exercises three times a day so that they can be easily recalled and performed during VCD episodes.

Continue for outcomes >>

OUTCOMES

Little is known about long-term outcomes for patients with VCD. The current literature consists of poorly described and conflicting case reports and results of small trials. Although documentation is lacking, the authors agree that, by educating the patient about the diagnosis, teaching effective VCD management strategies, and referring patients for voice therapy, clinicians can help patients achieve signicant improvement. Further investigation is needed to enhance our knowledge of the causes of VCD and to research additional diagnostic modalities and treatments.2

CASE PATIENT

After diagnosing VCD, the clinician explained the normal functioning of the vocal cords and how certain factors may cause them to close during inspiration. The patient then understood why bronchodilator therapy had failed to relieve her symptoms. She was counseled to continue her inhaled nasal steroid and proton pump inhibitor for her perennial nonallergic rhinitis and GERD, respectively, because these conditions may trigger her VCD, and to take steps to manage her stress. She learned breathing techniques to alleviate acute episodes of VCD and was informed of the option of voice therapy with a speech therapist if needed.

At six-week follow-up, the patient reported that she was complying with her medication regimen, had made an effort to relax more, and had experienced no acute attacks of VCD since her last visit.

CONCLUSION

Patients with symptoms suggestive of VCD require a thorough evaluation, including laryngoscopic examination, to ensure accurate diagnosis and avoid a too-common misdiagnosis. Primary care clinicians should know about VCD and, if not trained in the performance of flexible laryngoscopy, should refer the symptomatic patient to a specialist for appropriate work-up.

1. Hoyte FCL. Vocal cord dysfunction. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2013;33:1-22.

2. Ibrahim WH, Gheriani HA, Almohamed AA, Raza T. Paradoxical vocal cord motion disorder: past, present and future. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:164-172.

3. Powell DM, Karanfilov BI, Beechler KB, et al. Paradoxical vocal cord dysfunction in juveniles. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126(1):29-34.

4. Husein OF, Husein TN, Gardner R, et al. Formal psychological testing in patients with paradoxical vocal fold dysfunction. Laryngoscope. 2008; 118(4):740-747.

5. Dunglison RD. The Practice of Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lea and Blanchard; 1842:257-258.

6. MacKenzie M. Use of Laryngoscopy in Diseases of the Throat. Philadelphia, PA: Lindsey and Blackeston; 1869:246-250.

7. Osler W. Hysteria. In: The Principles and Practice of Medicine. 4th ed. New York, NY: Appleton; 1902:1111-1112.

8. Patterson R, Schatz M, Horton M. Munchausen’s stridor: non-organic laryngeal obstruction. Clin Allergy. 1974;4:307-310.

9. Christopher KL, Wood RP 2nd, Eckert RC, et al. Vocal cord dysfunction presenting as asthma. N Engl J Med. 1983;308(26):1566-1570.

10. Christopher KL. Understanding vocal cord dysfunction: a step in the right direction with a long road ahead. Chest. 2006;129(4):842-843.

11. Christopher KL, Morris MJ. Vocal cord dysfunction, paradoxic vocal fold motion, or laryngomalacia? Our understanding requires an interdisciplinary approach. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 2010;43:43-66.

12. Sasaki CT, Weaver EM. Physiology of the larynx. Am J Med. 1997;103:9S-18S.

13. Balkissoon R. Occupational upper airway disease. Clin Chest Med. 2002;23:717-725.

14. Murakami Y, Kirschner JA. Mechanical and physiological properties of reflex laryngeal closure. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1972;81(1):59-71.

15. Forrest LA, Husein T, Husein O. Paradoxical vocal cord motion disorder: classification and treatment. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:844-853.

16. Altman KW, Simpson CB, Amin MR, et al. Cough and paradoxical vocal fold motion. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127(6):501-511.

17. Freedman MR, Rosenberg SJ, Schmaling KB. Childhood sexual abuse in patients with paradoxical vocal cord dysfunction. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1991;179(5):295-298.

18. Buddiga P. Vocal cord dysfunction. Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/137782-overview. Accessed November 12, 2014.

19. Chiang T, Marcinow AM, deSilva BW, et al. Exercise-induced paradoxical vocal fold motion disorder: diagnosis and management. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:727-731.

20. Morris MJ, Deal LE, Bean DR, et al. Vocal cord dysfunction in patients with exertional dyspnea. Chest. 1999;116(6):1676-1682.

21. Hicks M, Brugman SM, Katial R. Vocal cord dysfunction/paradoxical vocal fold motion. Prim Care. 2008;35(1):81-103.

22. Maschka DA, Bauman NM, McCray PB, et al. A classification scheme for paradoxical vocal fold motion. Laryngoscope. 1997;107(11):1429-1435.

23. Uloza V, Vegiene A, Pribuisiene R, Saferis V. Quantitative evaluation of video laryngostroboscopy: reliability of the basic parameters. J Voice. 2013;27(3):361-368.

24. Pitchenik AF. Functional laryngeal obstruction relieved by panting. Chest. 1991;100(5):1465-1467.

25. Deckert J, Deckert L. Vocal cord dysfunction. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81(2):156-160.

26. Carding PN, Horsley IA, Docherty GJ. A study of the effectiveness of voice therapy in the treatment of 45 patients with nonorganic dysphonia. J Voice. 1999;13(1):72-104.

1. Hoyte FCL. Vocal cord dysfunction. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2013;33:1-22.

2. Ibrahim WH, Gheriani HA, Almohamed AA, Raza T. Paradoxical vocal cord motion disorder: past, present and future. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:164-172.

3. Powell DM, Karanfilov BI, Beechler KB, et al. Paradoxical vocal cord dysfunction in juveniles. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126(1):29-34.

4. Husein OF, Husein TN, Gardner R, et al. Formal psychological testing in patients with paradoxical vocal fold dysfunction. Laryngoscope. 2008; 118(4):740-747.

5. Dunglison RD. The Practice of Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lea and Blanchard; 1842:257-258.

6. MacKenzie M. Use of Laryngoscopy in Diseases of the Throat. Philadelphia, PA: Lindsey and Blackeston; 1869:246-250.

7. Osler W. Hysteria. In: The Principles and Practice of Medicine. 4th ed. New York, NY: Appleton; 1902:1111-1112.

8. Patterson R, Schatz M, Horton M. Munchausen’s stridor: non-organic laryngeal obstruction. Clin Allergy. 1974;4:307-310.

9. Christopher KL, Wood RP 2nd, Eckert RC, et al. Vocal cord dysfunction presenting as asthma. N Engl J Med. 1983;308(26):1566-1570.

10. Christopher KL. Understanding vocal cord dysfunction: a step in the right direction with a long road ahead. Chest. 2006;129(4):842-843.

11. Christopher KL, Morris MJ. Vocal cord dysfunction, paradoxic vocal fold motion, or laryngomalacia? Our understanding requires an interdisciplinary approach. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 2010;43:43-66.

12. Sasaki CT, Weaver EM. Physiology of the larynx. Am J Med. 1997;103:9S-18S.

13. Balkissoon R. Occupational upper airway disease. Clin Chest Med. 2002;23:717-725.

14. Murakami Y, Kirschner JA. Mechanical and physiological properties of reflex laryngeal closure. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1972;81(1):59-71.

15. Forrest LA, Husein T, Husein O. Paradoxical vocal cord motion disorder: classification and treatment. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:844-853.

16. Altman KW, Simpson CB, Amin MR, et al. Cough and paradoxical vocal fold motion. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127(6):501-511.

17. Freedman MR, Rosenberg SJ, Schmaling KB. Childhood sexual abuse in patients with paradoxical vocal cord dysfunction. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1991;179(5):295-298.

18. Buddiga P. Vocal cord dysfunction. Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/137782-overview. Accessed November 12, 2014.

19. Chiang T, Marcinow AM, deSilva BW, et al. Exercise-induced paradoxical vocal fold motion disorder: diagnosis and management. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:727-731.

20. Morris MJ, Deal LE, Bean DR, et al. Vocal cord dysfunction in patients with exertional dyspnea. Chest. 1999;116(6):1676-1682.

21. Hicks M, Brugman SM, Katial R. Vocal cord dysfunction/paradoxical vocal fold motion. Prim Care. 2008;35(1):81-103.

22. Maschka DA, Bauman NM, McCray PB, et al. A classification scheme for paradoxical vocal fold motion. Laryngoscope. 1997;107(11):1429-1435.

23. Uloza V, Vegiene A, Pribuisiene R, Saferis V. Quantitative evaluation of video laryngostroboscopy: reliability of the basic parameters. J Voice. 2013;27(3):361-368.

24. Pitchenik AF. Functional laryngeal obstruction relieved by panting. Chest. 1991;100(5):1465-1467.

25. Deckert J, Deckert L. Vocal cord dysfunction. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81(2):156-160.

26. Carding PN, Horsley IA, Docherty GJ. A study of the effectiveness of voice therapy in the treatment of 45 patients with nonorganic dysphonia. J Voice. 1999;13(1):72-104.